Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112243

Revised: October 16, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 141 Days and 1.2 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is among the most prevalent cancers worldwide. Recent studies have indicated that 5-methylcytosine (m5c) RNA modifications play crucial roles in various biological processes through interactions with specific regulatory factors, including their involvement in the malignant progression of multiple tumors.

To examine the impact of NOP2/sun RNA methyltransferase 5 (NSUN5), an m5c methyltransferase, on the functional behavior of HCC cells.

NSUN5 expression in HCC and normal liver tissues was analyzed using the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis bioinformatics tool. Human normal hepatocytes (LO2) and HCC cells were examined. The m5c levels in cellular ex

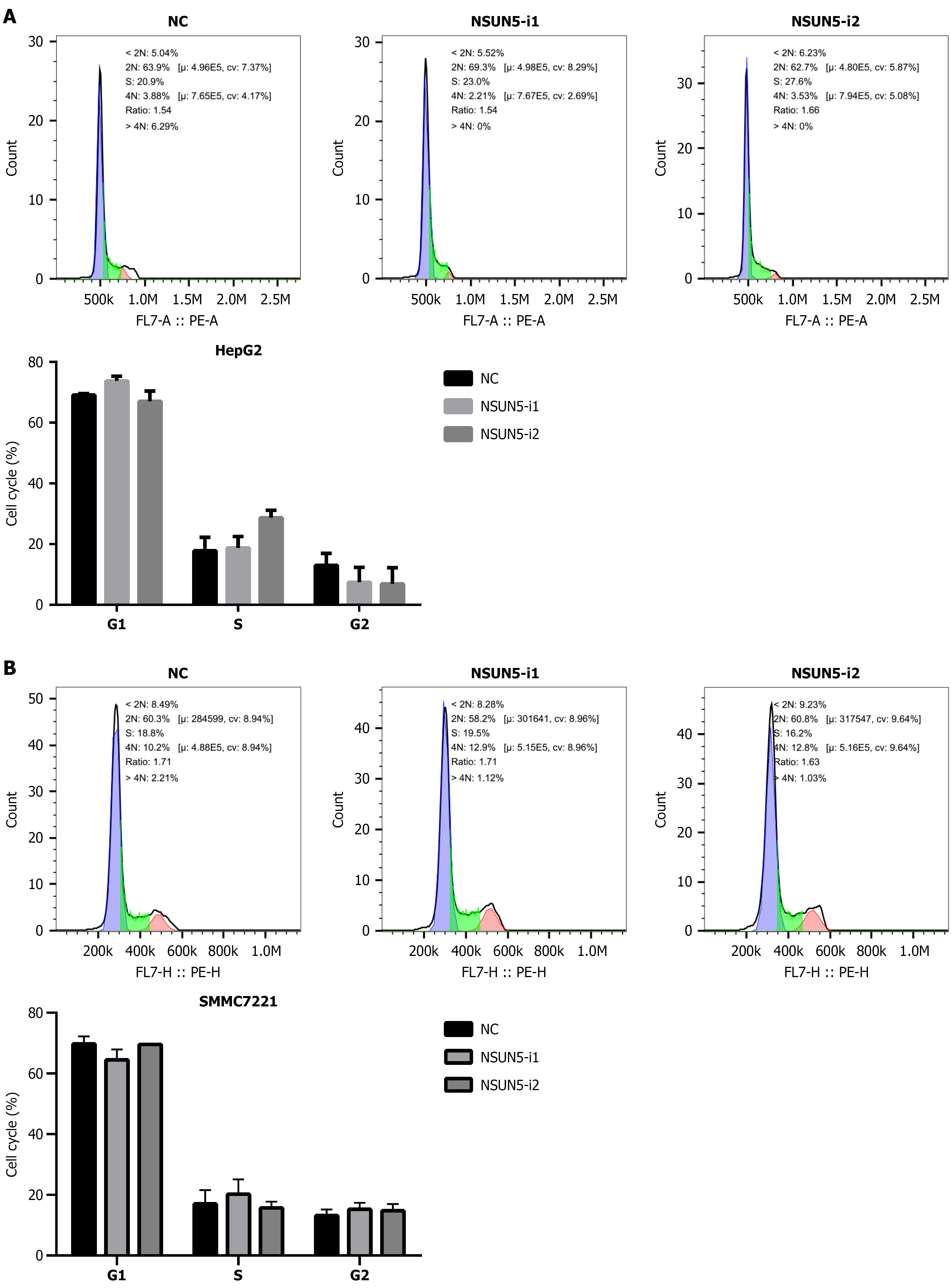

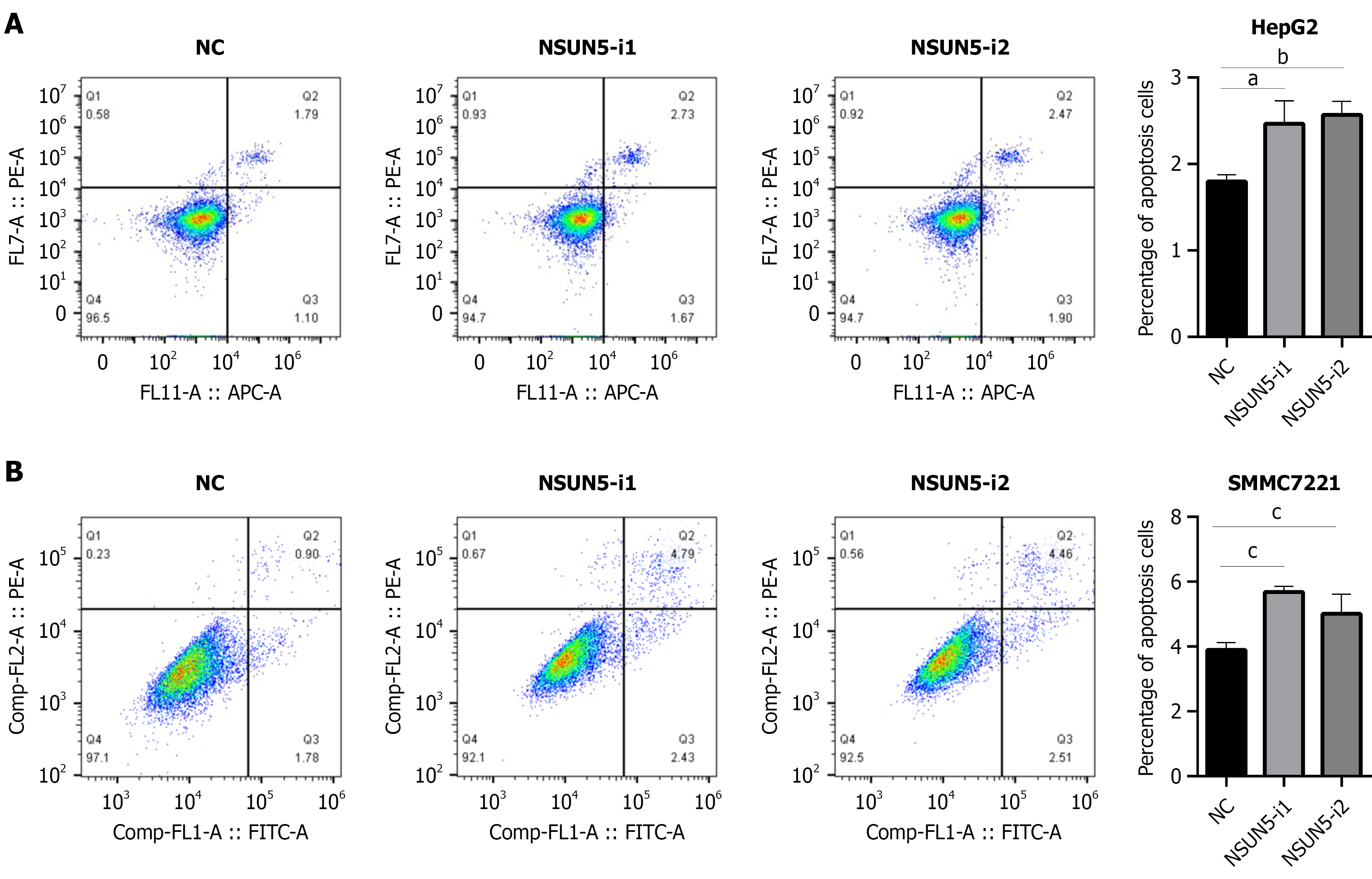

NSUN5 mRNA was significantly upregulated in HCC compared with normal liver tissues, with expression levels varying across different HCC stages (P < 0.05). HCC cells – HepG2, HEP3B, Huh-7, SMMC7721, and SK-HEP-1 – showed significantly higher NSUN5 mRNA expression levels than the normal human hepatocyte line LO2 (P < 0.05). Following short hairpin RNA-mediated NSUN5 silencing, HepG2 and SMMC7721 cells exhibited reduced proliferation and growth, decreased migration and invasion, and enhanced apoptotic levels (P < 0.05); however, they showed no significant changes in cell cycles (P > 0.05).

Both HCC tissues and cell models consistently demonstrated elevated NSNU5 mRNA and protein expression. Genetic inhibition of the m5c methyltransferase NSUN5 suppresses HCC cell growth, reduces invasiveness and migration, and induces apoptosis.

Core Tip: Epigenetic modifications are dynamic, reversible, and heritable chemical changes to biomolecules that occur without altering the sequence of nuclear DNA. Among these, the RNA modification 5-methylcytosine has garnered increasing attention. However, the roles of RNA modification 5-methylcytosine modifications and their modifying enzymes in gene regulation and chromatin organization remain largely unclear. While previous studies have reported the involvement of NOP2/sun RNA methyltransferase 5 in human cancers, its comprehensive role in hepatocellular carcinoma remains unexplored. Therefore, this study evaluates the effects of NOP2/sun RNA methyltransferase 5 on hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth, migration, and invasion at the cellular level.

- Citation: Liu N, Liu J, Wang YL, Zhu L, Zhu CW. Knockdown of 5-methylcytosine RNA methyltransferase NOP2/sun RNA methyltransferase 5 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells affects their biological functions. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 112243

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/112243.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112243

Globally, hepatic neoplasms rank among the most common cancers[1], with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounting for over 80% of cases. HCC is the sixth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third leading contributor to cancer mortality worldwide[2]. Major risk factors include chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection and alcohol-related liver hepatopathy[3,4]. The high HCC mortality rate is primarily due to cancer metastases, complicated pathogenesis, and postoperative recurrence[5]. Moreover, the disease often presents with subtle or nonspecific symptoms, leading to late-stage diagnoses and poor long-term outcomes. Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis remains a critical yet challenging area of research.

Epigenetic modifications are dynamic and reversible chemical alterations of biomolecules that occur without altering the nuclear DNA sequence. These modifications involve not only DNA and proteins but also RNA modifications, a relatively new area of research[6,7]. To date, more than 150 distinct RNA modification types have been identified, including N6-methyladenosine, which significantly influences epigenetic regulation and cellular processes. Such modifications have been implicated in a variety of human diseases, such as cancers, neurological disorders, and immune dysregulation[8-10]. Among these modifications, 5-methylcytosine (m5c) has attracted increasing attention[11]. However, its precise role in gene modulation, chromatin organization, and the mechanisms of its modifying enzymes remain to be fully elucidated. m5c modification depends on three classes of proteins: (1) Writers (methyltransferases); (2) Erasers (demethylases); and (3) Readers (methylation recognition proteins)[12]. NOP2/sun RNA methyltransferase 5 (NSUN5), one of the eight evolutionarily conserved m5c RNA methylases (NSUN1-7 and DNA methyltransferase 2), functions as a “writer” enzyme[13].

Previous studies have reported NSUN5 involvement in various human malignancies[14]. For example, epigenetic silencing of NSUN5 by DNA methylation has been identified as a marker of long-term survival in patients with glioma[15]. However, the specific functions of NSUN5 in HCC remain largely uncharacterized. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the role of NSUN5 in HCC initiation and progression, focusing on its modulation of cell proliferation, migration, and invasion at the cytological level.

NSUN5 mRNA expression profiles in HCC samples (n = 369) and normal liver tissue (n = 160) were obtained from the publicly available Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) bioinformatics tool. Gene expression patterns were subsequently analyzed based on tumor-node-metastasis staging classifications.

Normal human hepatocytes (LO2) and HCC cell lines (HepG2, HEP3B, Huh-7, SMMC7721, and SK-HEP-1) were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Shanghai Institute of Life Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences. LO2 cells were cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-enriched RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Scientific, United States), whereas HCC cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The day before transfection, logarithmically growing HCC cells were seeded into 6-well plates. When cell confluence reached 60%-80%, transfection was performed using NSUN5 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs – shNSUN5-1 (NSUN5-i1: 5’-AGACCACACTCAGCAGTGGCTTCTTCGTT-3’), shNSUN5-2 (NSUN5-i2: 5’-GGCCAAGGTGCTAGTGTATGAGTTGTTGT-3’), and blank control vectors (all constructed by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.). Transfections were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the Lipofectamin 3000 kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States).

Total cellular RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT Kit (Takara), which was then used as the template for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The qPCR was performed under the following conditions: (1) An initial hold at 50 °C for 2 minutes and 95 °C for 3 minutes; and (2) Followed by 40 cycles of

Quantification of m5c was conducted using the MethyFlash 5-mC SimpleStep Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Kit (fluorescence-based; Epigentek, United States) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 200 ng of RNA was added to wells precoated with a binding solution for 90 minutes at 37 °C. Anti-m5c antibody, signal indicator, and enhancer solution were sequentially added at specified dilutions, followed by incubation at room temperature (RT) for 60 minutes. Following fluorescent substrate addition and a 3-minute incubation at RT, fluorescence was recorded (530ex/590em nm) on a Synergy H1 plate reader (BioTek, Vermont) for 2-10 minutes.

For all groups, cells were collected 48 hours posttransfection, and total protein was extracted using a commercial protein extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA Quantitative Kit. Equal amounts of protein samples were then electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After transfer, membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 2 hours at RT and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against NSUN5 or β-actin (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology). Membranes were rinsed three times with tris-buffered saline tween-20, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–linked secondary antibody (1:1000, 2 hours, RT). After additional tris-buffered saline tween-20 rinses, protein membranes were developed using an enhanced luminescence chromogenic reagent and imaged with a chemiluminescence detection system. Band intensities were quantified using Image J (optical density analysis).

The proliferative capacity of HCC cells was evaluated using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay (Dojindo, Japan). The transfected cells were seeded into 96-well plates and maintained under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). Cell viability was measured at 24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours, and 96 hours. At each time point, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours. Optical density was then determined at 450 nm using a plate reader. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results were averaged for analysis. Transfected HCC cells (24 hours posttransfection) were seeded in 6-well plates (2 × 10³ cells/well) and cultured for 14 days in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS under 5% CO2. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes and staining with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 minutes, colonies containing ≥ 50 cells were microscopically quantified.

A Transwell Invasion Assay was performed to assess changes in HCC cell invasiveness. The Matrigel matrix was first polymerized in the upper chamber at 37 °C for 2 hours. Transfected cells were trypsinized after 24 hours of culture, resuspended in medium, and seeded into the Transwell chamber (1 × 105 cells/well). The upper chamber was filled with 200 μL of serum-free medium, while the lower chamber contained 600 μL of medium supplemented with 10% FBS. After 24 hours of incubation under standard culture conditions, the insert was processed by: (1) Mechanical removal of nonmigratory cells from the upper surface using a cotton swab; (2) Washing twice with PBS; (3) Fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes; and (4) Staining with 0.1% crystal violet solution for 20 minutes. Invaded cells were then visualized and quantified under a microscope.

Logarithmically growing cells (1 × 106/well) were transfected and seeded in 6-well plates until reaching 90% confluence. Mechanical wounds were then created by drawing a straight line across the center of each well using a 10 μL pipette tip. The cells were then gently washed thrice with PBS and incubated in medium for 24 hours. Images of the wound area were captured immediately after scratching and at 48 hours using an Olympus microscope. Migratory capacity was quantified using Image Pro Plus v6.0 software, and the migration rate was calculated as follows: [(initial scratch width - 24 hours scratch width)/initial width] × 100%. Triplicate experiments were performed to obtain the mean value.

Data analysis and graphical representation were generated using GraphPad Prism v8.0. Differences in NSUN5 expression between tumor and adjacent normal liver tissue were tested with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Quantitative data are reported as mean ± SD. Two-group comparisons were analyzed using either a two-tailed Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, while a one-way analysis of variance was applied for comparisons involving three or more groups. Significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Data from GEPIA, comprising 369 HCC samples compared with 160 normal liver tissue samples, revealed significant NSUN5 mRNA upregulation in HCC samples compared with normal counterparts (Figure 1A). Moreover, NSUN5 expression varied notably across tumor-node-metastasis stages (Figure 1B). In vitro experiments demonstrated elevated NSUN5 mRNA levels in HepG2, HEP3B, Huh-7, and SMMC7721 cells compared with LO2 cells (P < 0.05; Figure 1C), as well as elevated NSUN5 protein expression in all HCC cell strains, except HEP3B cells (Figure 1D). Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay measurements further showed higher m5c expression in HepG2, HEP3B, and SMMC7721 cells compared with LO2 cells (Figure 1E), as well as elevated m5c levels in the supernatants of HepG2, HEP3B, SMMC7721, and SK-HEP-1 cells (Figure 1F). Based on these expression profiles, HepG2 and SMMC7721, which exhibited the most significant differences, were selected for subsequent functional studies.

Efficient NSUN5 knockdown in HepG2 and SMMC7721 cells was confirmed by qPCR and Western blotting analyses following shRNA transfection. Functional assays revealed that silencing NSUN5 significantly reduced HepG2 and SMMC7721 cell viability (CCK-8) and colony formation capacity (P < 0.05; Figure 2).

Transwell invasion assays revealed that NSUN5 knockdown significantly reduced the invasive potential of HepG2 and SMMC7721 (P < 0.05; Figure 3).

Scratch assays demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in migration rates of HepG2 and SMMC7721 following NSUN5 knockdown (P < 0.05; Figure 4).

Flow cytometric analysis showed no significant differences in cell cycle phase distribution (G1/S/G2) after NSUN5 interference in either the HepG2 or SMMC7721 cell lines (P > 0.05), indicating that NSUN5 suppression does not affect cell cycle progression in these HCC cells (Figure 5).

NSUN5 silencing markedly increased apoptosis in both HepG2 and SMMC7721 cells (Figure 6), suggesting that NSUN5 contributes to the anti-apoptotic phenotype of HCC.

Initially identified in DNA, m5c is among the most abundant epigenetic modifications among hundreds of known chemical modifications[16]. In DNA, m5c functions as a regulator of gene expression and genome stability[17]. Advances in m5c detection have revealed widespread RNA m5c modifications, in which a methyl group from the donor is added to the fifth carbon position of cytosine bases in RNA. These modifications influence multiple aspects of RNA metabolism, including transcriptional regulation, translational control, RNA stability maintenance, and ribosomal assembly[18]. Recent studies indicate that m5c, through interactions with specific regulatory factors, participates in key biological processes, including oncogenic progression[19,20]. Notably, m5c regulators are frequently overexpressed in various cancers, such as gastric, pancreatic, breast, and leukemia[21-24]. Our data showed elevated m5c RNA levels in HCC cells and in HCC cell supernatants, prompting an exploration of m5c modifications in HCC. We focused on NSUN5 to characterize its biological function in HCC.

Comparative analysis using the GEPIA database revealed significant upregulation of NSUN5 in HCC tissues relative to adjacent normal liver tissue, as well as stage-dependent differences in expression. In vitro experiments confirmed elevated NSUN5 expression in HCC cell lines compared with normal hepatocytes. These findings align with previous analyses of The Cancer Genome Atlas data and 122 HCC patient tissue samples by Zhang et al[25], which also identified NSUN5 overexpression and linked it to poorer survival outcomes. Increasing evidence underscores the critical role of NSUN5 in tumorigenesis and the malignant progression of various tumors[26], with the protein exerting its biological effects through diverse molecular pathways. Jiang et al[27] reported NSUN5 upregulation in colon cancer tissues, where NSUN5 modulates cellular proliferation through cell cycle regulation. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, NSUN5 was also significantly upregulated and directly bound to the METTL1 transcript, enhancing its m5c modification[28]. In our study, initial screening identified two HCC cell strains, HepG2 and SMMC7221, for functional assays. NSUN5 knockdown through shRNA transfection markedly reduced HCC proliferation, migration, and invasion. Furthermore, flow cytometric analysis revealed a substantial increase in HCC apoptosis in NSUN5-silenced cells. However, contrary to Jiang et al’s findings[27] in colorectal cancer, NSUN5 depletion in HCC did not affect cell cycle progression, suggesting the need for further investigation into the role of NSUN5 in HCC cell cycle regulation. Similarly, among other m5c regulators, Hussain et al[29] reported that the methyltransferase activity of NSUN2 was dispensable for its effects on cell cycle and spindle stability, suggesting that NSUN5 may primarily influence apoptosis-related pathways or protein translation efficiency. Emerging evidence also implicates NSUN5 in ribosome biogenesis. Epigenetic silencing of NSUN5 has been shown to promote long-term survival in patients with glioma and to sensitize gliomas to bioactive compounds that generate oxidative stress[30]. These findings, together with our data, highlight the complexity of m5c-mediated regulation and the necessity for deeper investigation into the tumorigenic mechanisms of NSUN5.

This study has several limitations. First, we only preliminarily explored the regulatory effects of NSUN5 on liver cancer cell functions and did not predict or validate its downstream target genes. Second, the selection of cell lines was limited: Only two were used for functional assays, and the same analyses were not performed on the other two sets, which may exhibit distinct characteristics. Third, the study design did not include rescue experiments to verify specificity. The absence of such validation fails to rule out off-target effects of the shRNA (e.g., silencing other genes that cause phenotypic changes) and cannot definitively confirm that the observed phenotypic changes are specifically caused by NSUN5 deficiency. Therefore, a well-designed, comprehensive study is needed to further verify the role of NSUN5 in HCC.

In summary, we primarily demonstrated that the RNA m5c methyltransferase NSUN5 is highly expressed in HCC. Downregulation of NSUN5 inhibited HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, while promoting apoptosis in vitro. These findings suggest that suppressing NSUN5 expression may serve as a potential therapeutic approach for HCC management.

| 1. | Tan EY, Danpanichkul P, Yong JN, Yu Z, Tan DJH, Lim WH, Koh B, Lim RYZ, Tham EKJ, Mitra K, Morishita A, Hsu YC, Yang JD, Takahashi H, Zheng MH, Nakajima A, Ng CH, Wijarnpreecha K, Muthiah MD, Singal AG, Huang DQ. Liver cancer in 2021: Global Burden of Disease study. J Hepatol. 2025;82:851-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 86.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Huang DQ, Singal AG, Kono Y, Tan DJH, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Changing global epidemiology of liver cancer from 2010 to 2019: NASH is the fastest growing cause of liver cancer. Cell Metab. 2022;34:969-977.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 99.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huang J, Lok V, Ngai CH, Chu C, Patel HK, Thoguluva Chandraseka V, Zhang L, Chen P, Wang S, Lao XQ, Tse LA, Xu W, Zheng ZJ, Wong MCS. Disease Burden, Risk Factors, and Recent Trends of Liver Cancer: A Global Country-Level Analysis. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:330-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Falade-Nwulia O, Seaberg EC, Rinaldo CR, Badri S, Witt M, Thio CL. Comparative risk of liver-related mortality from chronic hepatitis B versus chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ecker BL, Lee J, Saadat LV, Aparicio T, Buisman FE, Balachandran VP, Drebin JA, Hasegawa K, Jarnagin WR, Kemeny NE, Kingham TP, Groot Koerkamp B, Kokudo N, Matsuyama Y, Portier G, Saltz LB, Soares KC, Wei AC, Gonen M, D'Angelica MI. Recurrence-free survival versus overall survival as a primary endpoint for studies of resected colorectal liver metastasis: a retrospective study and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:1332-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xu X, Peng Q, Jiang X, Tan S, Yang Y, Yang W, Han Y, Chen Y, Oyang L, Lin J, Xia L, Peng M, Wu N, Tang Y, Li J, Liao Q, Zhou Y. Metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modifications in cancer: from the impacts and mechanisms to the treatment potential. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:1357-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang Y, Wang Y, Patel H, Chen J, Wang J, Chen ZS, Wang H. Epigenetic modification of m(6)A regulator proteins in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 41.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xue C, Chu Q, Zheng Q, Jiang S, Bao Z, Su Y, Lu J, Li L. Role of main RNA modifications in cancer: N(6)-methyladenosine, 5-methylcytosine, and pseudouridine. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lv J, Xing L, Zhong X, Li K, Liu M, Du K. Role of N6-methyladenosine modification in central nervous system diseases and related therapeutic agents. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162:114583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen H, Zhang X, Su H, Zeng J, Chan H, Li Q, Liu X, Zhang L, Wu WKK, Chan MTV, Chen H. Immune dysregulation and RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in sepsis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2023;14:e1764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen X, Yuan Y, Zhou F, Huang X, Li L, Pu J, Zeng Y, Jiang X. RNA m5C modification: from physiology to pathology and its biological significance. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1599305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bohnsack KE, Höbartner C, Bohnsack MT. Eukaryotic 5-methylcytosine (m⁵C) RNA Methyltransferases: Mechanisms, Cellular Functions, and Links to Disease. Genes (Basel). 2019;10:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li M, Tao Z, Zhao Y, Li L, Zheng J, Li Z, Chen X. 5-methylcytosine RNA methyltransferases and their potential roles in cancer. J Transl Med. 2022;20:214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zheng L, Li M, Wei J, Chen S, Xue C, Duan Y, Tang F, Li G, Xiong W, She K, Deng H, Zhou M. NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 2 is a potential pan-cancer prognostic biomarker and is related to immunity. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0292212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang P, Wu M, Tu Z, Tao C, Hu Q, Li K, Zhu X, Huang K. Identification of RNA: 5-Methylcytosine Methyltransferases-Related Signature for Predicting Prognosis in Glioma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Franchini DM, Schmitz KM, Petersen-Mahrt SK. 5-Methylcytosine DNA demethylation: more than losing a methyl group. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:419-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Breiling A, Lyko F. Epigenetic regulatory functions of DNA modifications: 5-methylcytosine and beyond. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2015;8:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gao Y, Fang J. RNA 5-methylcytosine modification and its emerging role as an epitranscriptomic mark. RNA Biol. 2021;18:117-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li F, Liu T, Dong Y, Gao Q, Lu R, Deng Z. 5-Methylcytosine RNA modification and its roles in cancer and cancer chemotherapy resistance. J Transl Med. 2025;23:390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu T, Hu X, Lin C, Shi X, He Y, Zhang J, Cai K. 5-methylcytosine RNA methylation regulators affect prognosis and tumor microenvironment in lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Song Q, Wu J, Wan H, Fan D. Prognostic signature and immune landscape of 5-methylcytosine-related long non-coding RNAs in gastric cancer. Heliyon. 2024;10:e37290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang R, Guo Y, Ma P, Song Y, Min J, Zhao T, Hua L, Zhang C, Yang C, Shi J, Zhu L, Gan D, Li S, Li J, Su H. Comprehensive Analysis of 5-Methylcytosine (m(5)C) Regulators and the Immune Microenvironment in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma to Aid Immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2022;12:851766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Guo M, Li X, Zhang L, Liu D, Du W, Yin D, Lyu N, Zhao G, Guo C, Tang D. Accurate quantification of 5-Methylcytosine, 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-Formylcytosine, and 5-Carboxylcytosine in genomic DNA from breast cancer by chemical derivatization coupled with ultra performance liquid chromatography- electrospray quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:91248-91257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pérez C, Martínez-Calle N, Martín-Subero JI, Segura V, Delabesse E, Fernandez-Mercado M, Garate L, Alvarez S, Rifon J, Varea S, Boultwood J, Wainscoat JS, Cruz Cigudosa J, Calasanz MJ, Cross NC, Prósper F, Agirre X. TET2 mutations are associated with specific 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine profiles in patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang XW, Wu LY, Liu HR, Huang Y, Qi Q, Zhong R, Zhu L, Gao CF, Zhou L, Yu J, Wu HG. NSUN5 promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2022;24:439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang X, Huang Y, Wu L, Qi Q, Zhong R, Li S, Zhao J, Liu H, Wu H. NSUN5 is Upregulated and Positively Correlated with Translation in Human Cancers: A Bioinformatics-based Study. 2020 Preprint. Available from: Research Square. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Jiang Z, Li S, Han MJ, Hu GM, Cheng P. High expression of NSUN5 promotes cell proliferation via cell cycle regulation in colorectal cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12:3858-3870. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Cui Y, Hu Z, Zhang C. RNA Methyltransferase NSUN5 Promotes Esophageal Cancer via 5-Methylcytosine Modification of METTL1. Mol Carcinog. 2025;64:399-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hussain S, Benavente SB, Nascimento E, Dragoni I, Kurowski A, Gillich A, Humphreys P, Frye M. The nucleolar RNA methyltransferase Misu (NSun2) is required for mitotic spindle stability. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:27-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Janin M, Ortiz-Barahona V, de Moura MC, Martínez-Cardús A, Llinàs-Arias P, Soler M, Nachmani D, Pelletier J, Schumann U, Calleja-Cervantes ME, Moran S, Guil S, Bueno-Costa A, Piñeyro D, Perez-Salvia M, Rosselló-Tortella M, Piqué L, Bech-Serra JJ, De La Torre C, Vidal A, Martínez-Iniesta M, Martín-Tejera JF, Villanueva A, Arias A, Cuartas I, Aransay AM, La Madrid AM, Carcaboso AM, Santa-Maria V, Mora J, Fernandez AF, Fraga MF, Aldecoa I, Pedrosa L, Graus F, Vidal N, Martínez-Soler F, Tortosa A, Carrato C, Balañá C, Boudreau MW, Hergenrother PJ, Kötter P, Entian KD, Hench J, Frank S, Mansouri S, Zadeh G, Dans PD, Orozco M, Thomas G, Blanco S, Seoane J, Preiss T, Pandolfi PP, Esteller M. Epigenetic loss of RNA-methyltransferase NSUN5 in glioma targets ribosomes to drive a stress adaptive translational program. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138:1053-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/