Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112251

Revised: September 15, 2025

Accepted: November 20, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 183 Days and 19.9 Hours

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is currently the most commonly perfor

To evaluate changes in residual gastric volume after LSG using three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction and to investigate the factors contributing to gastric dilation.

This retrospective study included 50 patients who underwent LSG. Preoperative clinical and laboratory data were obtained. The residual gastric volume was measured using three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction at 1 month and 3 months postoperatively. The total sleeve volume, tube volume, antral volume, and tube-to-antral volume ratio were also assessed. Resected gas

The 50 included patients had a mean preoperative body mass index of 42.27 ± 7.19 kg/m2 and average %TWL of 34% ± 7% at 1 year after LSG. At 1 month after LSG, the mean tube volume, antral volume, and total sleeve volume were 45.93 ± 16.75 mL, 115.85 ± 44.92 mL, and 161.77 ± 55.37 mL, respectively. At 3 months after LSG, the residual gastric volume showed statistically significant dilation (average dilation degree: 13.50% ± 17.35%). %TWL at 1 year significantly correlated with residual gastric dilation (P < 0.05). Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses revealed that preoperative type 2 diabetes, residual gastric volume at 1 month after LSG, and GERD-Q scores were independent risk factors influencing the degree of residual gastric dilation.

In conclusion, residual gastric dilation after LSG significantly affected the efficacy of weight loss. Preoperative type 2 diabetes, residual gastric volume at 1 month after LSG, and GERD-Q scores were independent risk factors affecting the degree of residual gastric dilation.

Core Tip: This study leverages three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction to analyze the early dilation of the residual stomach post-laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. It identifies significant factors influencing gastric dilation, including preoperative type 2 diabetes, initial postoperative residual gastric volume, and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Ques

- Citation: Li Z, Wu WZ, Song Y, Li ZP, Guo D, Li Y. Early gastric dilation after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: Insights from a three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 112251

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/112251.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112251

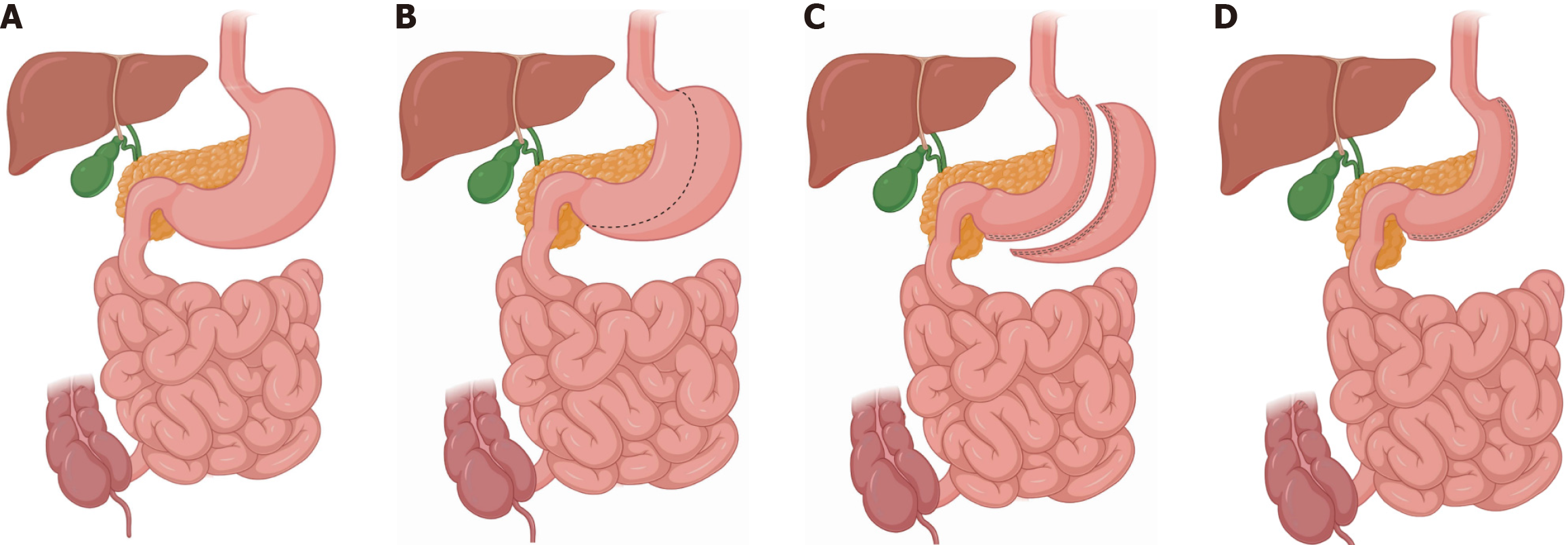

Obesity, defined as excess body fat, can cause various diseases such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[1,2]. Currently, bariatric surgery is the only effective therapy available for severe obesity[3]. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is the most frequently performed bariatric procedure worldwide owing to its effective weight loss, simplicity, and few complications[4,5]. LSG involves the excision of approximately 80% of the stomach, mainly the body and fundus, creating a tubular duct along the lesser curvature, which results in restricted food intake and subsequent weight loss (Figure 1)[6]. Nevertheless, compared to malabsorptive procedures, LSG tends to have higher rates of insufficient weight loss and regain[7].

Long-term studies have reported an appreciable frequency of inadequate weight loss or even weight regain after LSG, with an estimated failure rate of 14%-37%[8]. Residual gastric dilatation was held responsible for inadequate weight loss or weight regain following LSG, as candidates for revisional surgery after LSG usually exhibit large gastric volumes[9,10]. Several studies have indicated that the dilation of the residual stomach is one of the possible reasons for weight regain and inadequate weight loss[11,12]. However, the factors contributing to residual gastric dilation after LSG have not yet been elucidated, prompting further investigations. Patient eating habits, gastric compliance, residual gastric morphology, and surgical techniques are all factors that may contribute to gastric dilation; however, they remain controversial[13,14]. In this study, we analyzed changes in residual gastric volume in the early postoperative period (1 month postoperatively vs 3 months postoperatively) and calculated the degree of early expansion of the residual stomach. We also investigated the impact of early expansion of the residual stomach on weight loss after LSG. Furthermore, we analyzed risk factors for gastric dilation, including preoperative clinical baseline data, gastric morphology indicators, treatment adherence, and eating behaviors after LSG.

This study aimed to assist clinicians in the early identification of risk factors, enhance postoperative management strategies, delay residual stomach expansion, and ensure sustained weight loss.

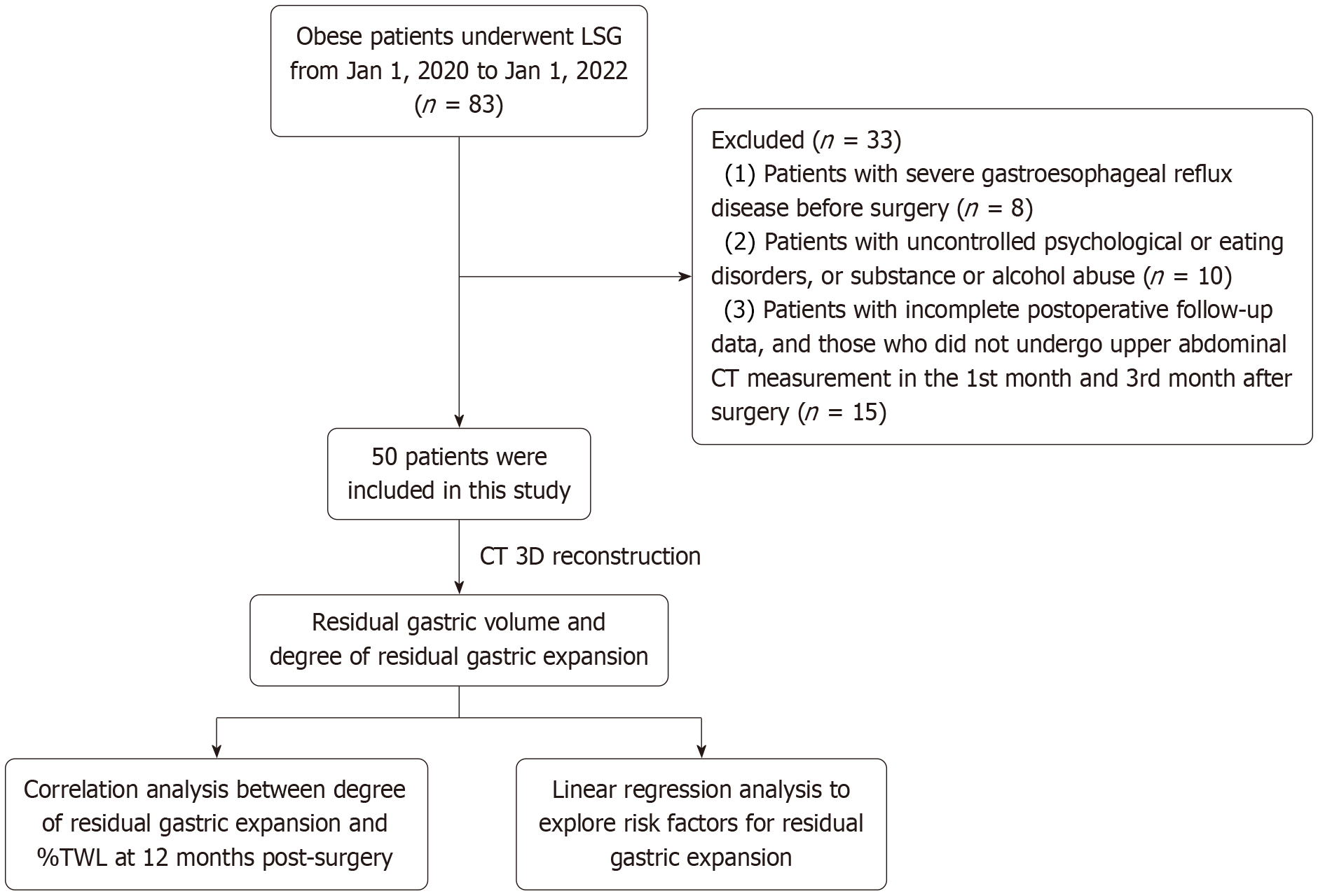

This retrospective study included 50 patients who underwent LSG for the treatment of severe obesity at The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University between January 1, 2020, and January 1, 2022. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study included patients aged 18-60 years, with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 32.5 kg/m2 or BMI between 27.5 and 32.5 kg/m2 associated with comorbidity, who had not responded to conservative treatment. Patients with severe gastroesophageal reflux disease, uncontrolled psychological or eating disorders, drug or alcohol abuse, high surgical risk, uncontrolled endocrine disorders, non-compliance with medical treatment, or severe liver disease were excluded from the study.

All patients underwent thorough history taking and clinical examination prior to LSG. Preoperative baseline data, including age, sex, BMI, coexisting diseases, and history of smoking and alcohol consumption, were collected. Pre

Two surgeons performed all LSG procedures. A standardized three-port or four-port technique was used for all patients in the study. All procedures were conducted under general anesthesia with the patients placed in the supine position. After mobilizing the fundus and exposing the angle of His, a Bougie (36 Fr) was inserted to guide gastric resection, which was performed using five-seven 60-mm staples. The first firing of the stapler began 4 cm from the pylorus, and the final firing was completed approximately 1 cm lateral to the His angle. The choice of cartridge was based on the gastric wall thickness and compressibility, utilizing a green load for the initial firing and blue loads for subsequent applications. Seromuscular reinforcement was performed along the staple line, resulting in a small gastric sleeve with a capacity of 80-120 mL. The resected stomach was retrieved through a 12-mm port site, and an abdominal drain was placed along the length of the gastric staple line.

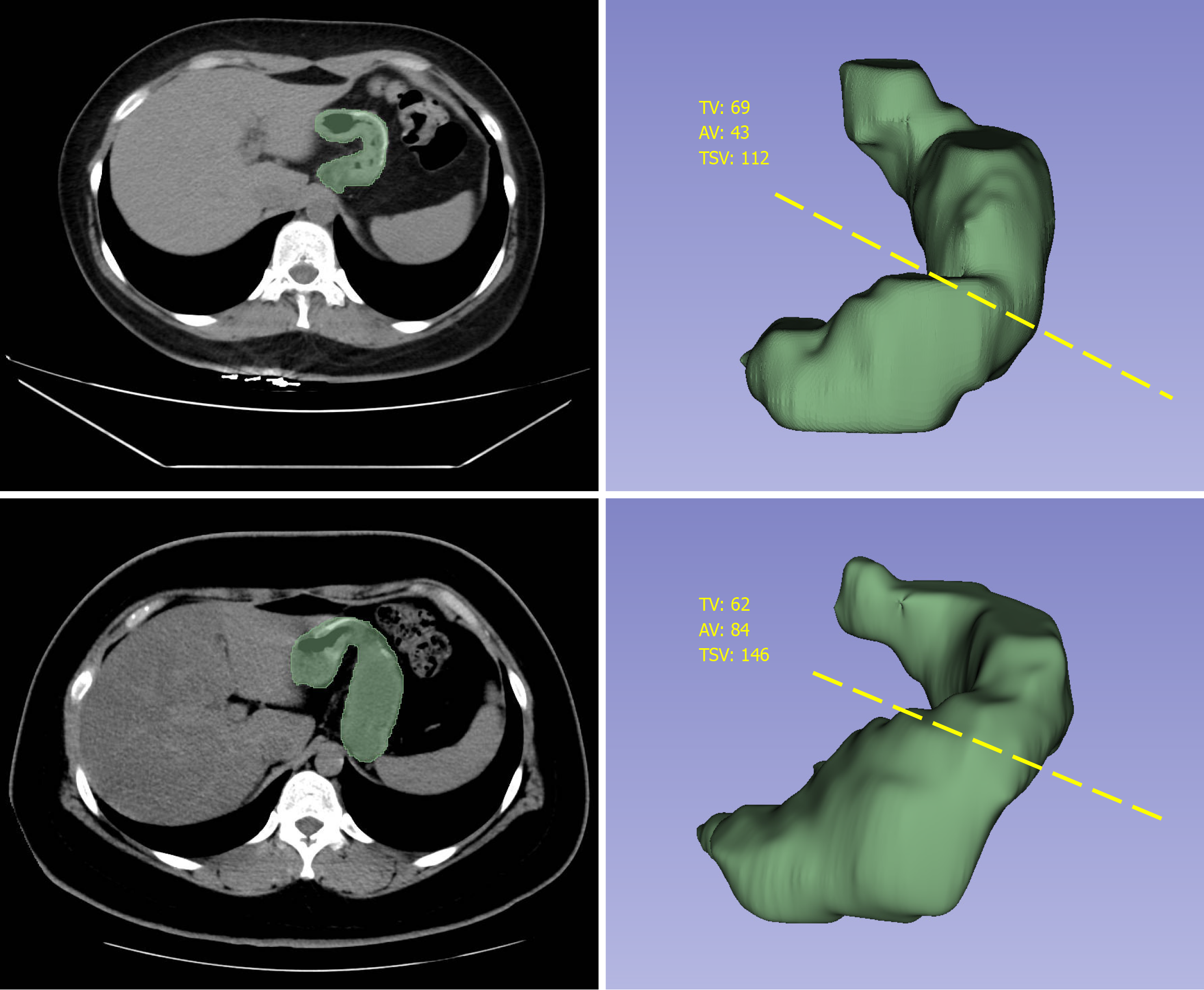

All imaging examinations were performed by experienced radiologists in the Department of Radiology of our university hospital using a multidetector CT scanner (GE Optima CT670, GE Healthcare). Gastric volume was assessed at 1 month and 3 months after surgery. Fasting and water deprivation were carried out for 4 hours before CT examination. Patients were instructed to drink as much water as possible until they felt full to ensure sufficient gastric filling. Images were acquired with the patients in supine position. The resultant distension was standardized using the same preparation and techniques for each case. Thin-section images were reconstructed in 5-mm slice thickness increments with 0.625 mm detector collimation. The data were transferred to a dedicated three-dimensional (3D) workstation, and 3D volume-rendering images were created using a combination of manual and semiautomatic segmentation tools. Using the height, width, and depth parameters from the cardia to the pylorus, the gastric volume was calculated after multiplane reconstruction and 3D volume rendering (Figure 3). All gastric CT data were analyzed by the same radiologist, who was blinded to the body weight and percent total weight loss (%TWL) of the patients. The following parameters of the residual stomach were assessed: Total sleeve volume, tube volume (corresponding to the volume of the sleeve portion from the top of the staple line to the incisura angularis), antral volume (corresponding to the volume of the sleeve portion from the incisura angularis to the pylorus), and tube-to-antral volume ratio. The incisura angularis is located at the turning point between the gastric body and the antrum, presenting as a sharp inwardly indented structure on the lesser curvature of the stomach. It serves as the landmark for distinguishing the antral portion from the tubular portion of the residual stomach. The degree of residual gastric dilation was computed using the following formula: Degree of residual gastric dilation = (total stomach volume at 3 months × total stomach volume at 1 month)/total stomach volume at 1 month) × 100.

The resected gastric volume was standardized. A 16-Fr Foley catheter was inserted into an incision made in the fundus and secured with a purse-string suture to close the opening tightly and fix the catheter in place. Saline was manually injected using a 50-mL syringe until leakage was observed from the staple line. The volume of water injected into the stomach was equal to the volume of the resected gastric tissue.

Postoperative analgesia and anti-infection and anticoagulant treatments were routinely administered according to our protocol. Patients were encouraged to get out of bed and were provided with a clear liquid diet during the early postoperative period. Abdominal drainage tubes were removed if there were no abnormalities on upper gastrointestinal radiography on the third day after surgery, and the patient was discharged a day later. Each participant met with our dietitian and was provided with postoperative dietary guidance. All patients underwent follow-up evaluations in the outpatient clinic at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months postoperatively and every year after surgery. The collected weight loss-related data included BMI and %TWL. Other follow-ups included comorbidity remission, laboratory examinations, imaging examinations, and follow-up questionnaires. The postoperative follow-up questionnaires included the Eating Behavior after Bariatric Surgery Questionnaire (EBBS-Q) and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire (GERD-Q). These tools are used to evaluate patients’ postoperative dietary behaviors, adherence to treatment protocols, and the presence of reflux conditions. The EBBS-Q, a self-administered survey consisting of 11 items, addresses aspects of food, beverage consumption, behavior, and lifestyle[15]. It quantifies patient adherence to dietary and lifestyle recommendations following bariatric surgery by assessing their compliance with postoperative guidelines. The GERD-Q is a simple self-administered tool used to evaluate GERD symptoms[16]. It includes six items that ask patients to report the number of days they experienced symptoms and their use of over-the-counter medications during the previous seven days. All questionnaires were completed during outpatient visits or telephonic follow-ups. We collected questionnaire data at 1 month postoperatively to explore whether these factors were related to the occurrence of residual gastric dilatation.

The objectives of this study were twofold: (1) To investigate the influence of residual gastric dilation on the efficacy of weight loss; and (2) To analyze the factors related to residual gastric dilation from a multifactorial perspective, including clinical characteristics, radiological images, and psychological factors.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0. All continuous variables were tested for normality. Continuous measurement variables were described as mean ± SD, whereas categorical variables were expressed as n (%). Student’s t-test was used to compare the means between two groups, whereas analysis of variance was used for comparisons involving more than two groups. The correlation between %TWL at 12 months after LSG and the degree of residual gastric dilation was determined using Spearman’s correlation analysis. Univariate linear regression analysis was conducted to identify potentially significant risk factors for residual gastric dilation. Any factor with P < 0.1 in the univariate linear regression was further evaluated through a multivariate linear analysis, the result of which was finally presented. The significance level was set at P < 0.05 in the univariate linear regression analysis. All tests for statistical significance were two-tailed. Collinearity between variables was verified by calculating the variance inflation factor; all values were < 2, indicating the absence of multicollinearity.

According to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, 50 patients were included in this study from January 1, 2020, to January 1, 2022. Table 1 presents the baseline data, preoperative comorbidities, laboratory test results, gastric measurements, and follow-up data of the patients included in this study. Among the 50 included patients, 68% were female, with a mean age of 32.65 ± 8.31 years, and a mean BMI of 42.27 ± 7.19 kg/m2. We measured the morphological indices of the resected stomach intraoperatively, the mean volume of the resected stomach is 793.08 ± 156.03 mL, and the length of the stapling line of the stomach removed during the operation was measured to be 33.75 ± 3.92 cm.

| Characteristics | mean ± SD or n (%) |

| Age (years) | 32.65 ± 8.31 |

| Sex (male/female) | 16/34 (32) |

| Height (cm) | 169.82 ± 7.89 |

| Body weight (kg) | 121.49 ± 25.15 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 42.27 ± 7.19 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Type 2 diabetes | 18 (36) |

| Hypertension | 13 (26) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7 (14) |

| Hyperuricemia | 19 (38) |

| Chronic gastritis | 18 (36) |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 21 (42) |

| Smoking | 10 (20) |

| Alcohol consumption | 8 (16) |

| Laboratory parameter | |

| Preoperative fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 5.45 ± 1.34 |

| Preoperative HbA1c (%) | 6.00 ± 1.02 |

| Preoperative WBC (109/L) | 8.25 ± 1.92 |

| Preoperative CRP (mg/L) | 10.22 ± 7.71 |

| Resected stomach measurements | |

| Resected stomach volume (mL) | 793.08 ± 156.03 |

| Spinal length (cm) | 33.75 ± 3.92 |

| Postoperative follow-up indicators | |

| GERD-Q score | 3.56 ± 1.58 |

| EBBS-Q score | 10.80 ± 2.79 |

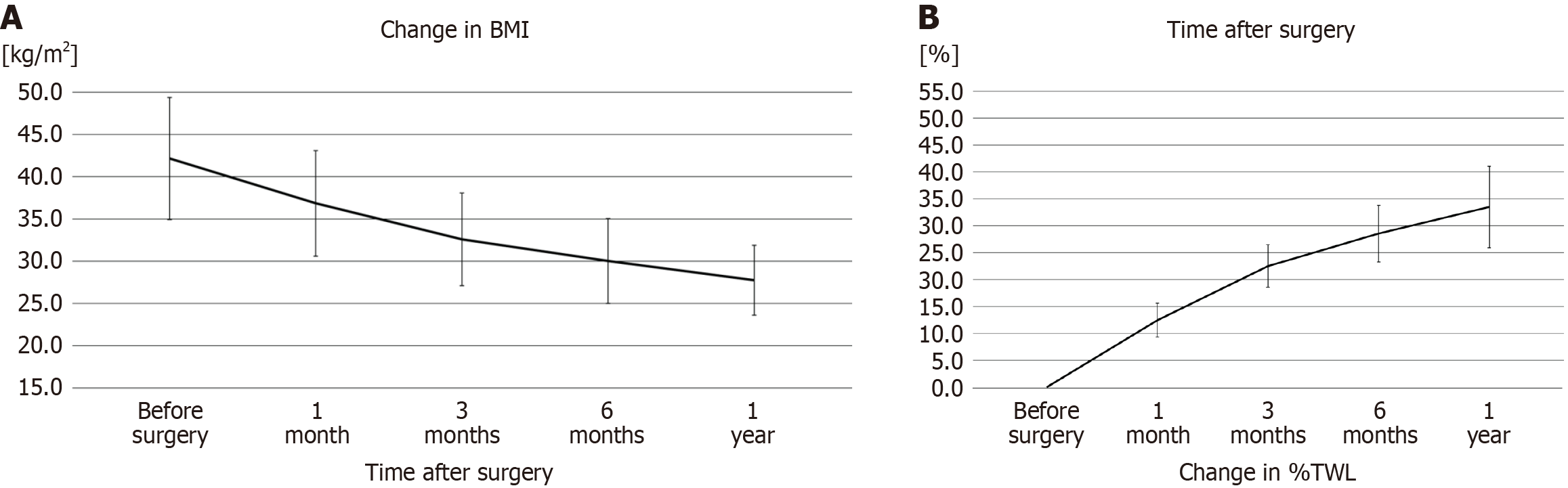

Table 2 presents the significant decrease in weight and BMI throughout the 12-month follow-up period, with a gradual increase in %TWL at each follow-up time point (P < 0.05). Line graphs showing the trend of weight changes are presented in Figure 4. In addition, there was no significant correlation between the resected gastric volume and %TWL at 12 months, EBBS-Q score, or GERD-Q score (Table 3).

| Characteristic | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) | %TWL |

| Preoperative | 121.49 ± 25.15 | 42.27 ± 7.19 | - |

| 1 month | 106.19 ± 21.99 | 36.85 ± 6.25 | 12 ± 3 |

| 3 months | 93.91 ± 19.61 | 32.59 ± 5.47 | 23 ± 4 |

| 6 months | 86.52 ± 18.11 | 30.02 ± 5.02 | 29 ± 5 |

| 12 months | 79.81 ± 14.84 | 27.75 ± 4.13 | 34 ± 7 |

| Variable | r value | P value |

| %TWL at 12 months | 0.083 | 0.568 |

| GERD-Q score | -0.344 | 0.124 |

| EBBS-Q score | 0.137 | 0.344 |

Table 4 presents the volume of the entire residual stomach and its components (body and antrum) at 1 months and 3 months postoperatively. At 1 month after LSG, the mean gastric volumes and dimensions assessed by 3D CT reconstruction were 161.77 ± 55.37 mL for the total gastric volume, 115.85 ± 44.92 mL for the tube volume, and 45.93 ± 16.75 mL for the antral volume. At 3 months after surgery, the mean gastric volume in the entire study population had significantly increased (P = 0.001). Simultaneously, the volumes of the gastric antrum and body of the remnant stomach also significantly increased (P < 0.05). However, tube-to-antral volume ratio did not result in statistically significant changes during the early postoperative period.

| Residual gastric measurement | 1 month | 3 months | P value |

| AV (mL) | 45.93 ± 16.75 | 48.14 ± 16.40 | 0.038 |

| TV (mL) | 115.85 ± 44.92 | 126.29 ± 38.27 | 0.001 |

| TSV (mL) | 161.77 ± 55.37 | 174.43 ± 47.30 | 0.001 |

| TAVR | 2.69 | 2.84 | 0.950 |

| Degree of residual gastric dilation (%) | - | 13.50 ± 17.35 | - |

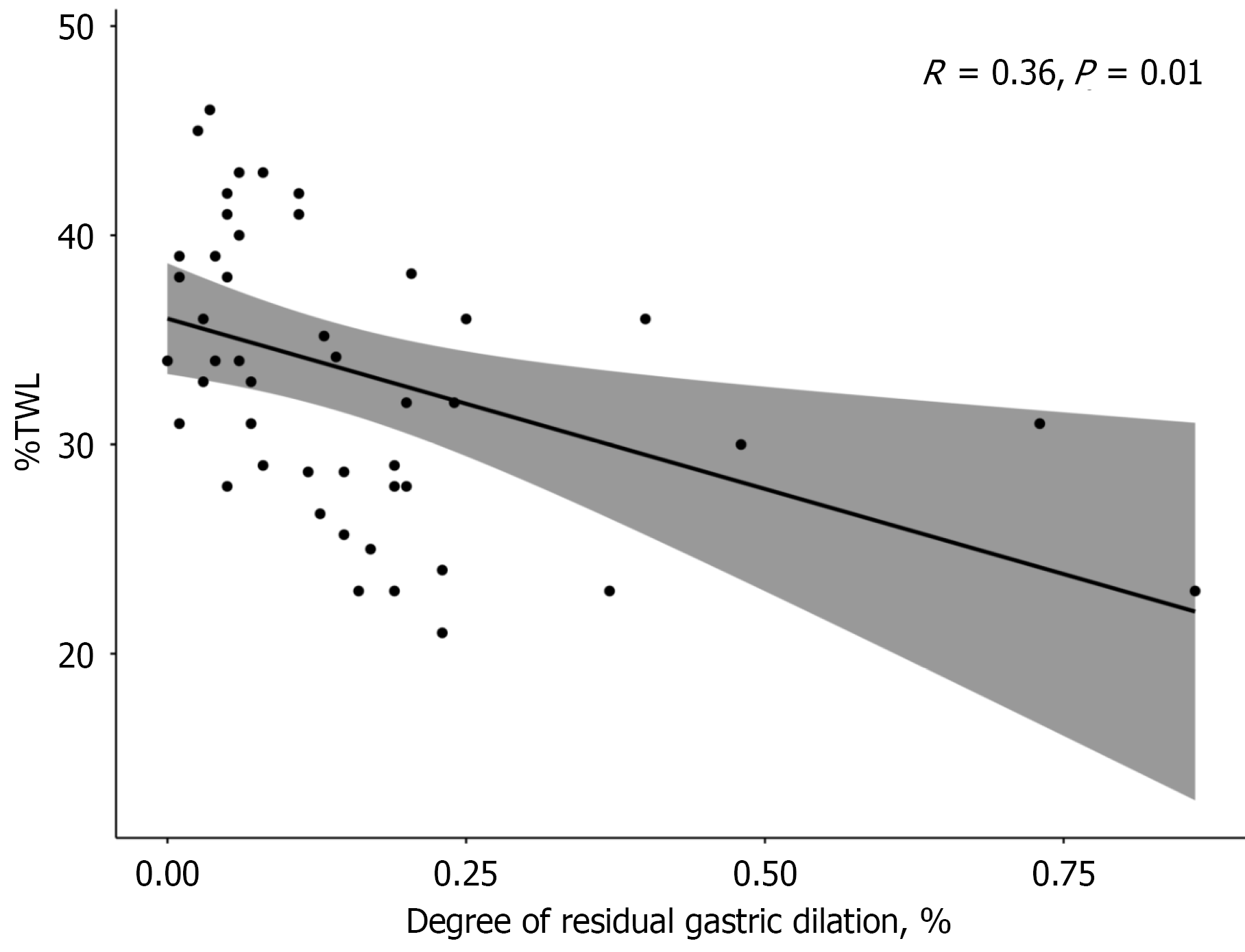

Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to describe the relationship between %TWL at 12 months after LSG and the degree of residual gastric dilation. The results indicated that the %TWL at 12 months after LSG was negatively correlated with the degree of residual gastric dilation (R = 0.36, P = 0.01), suggesting that patients with residual gastric dilation had poorer postoperative weight loss outcomes (Figure 5).

We further identified risk factors for early residual gastric dilation using univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses (Table 5). Variables with P < 0.1 in the univariate analysis (age, BMI, type 2 diabetes, residual gastric volume at 1 month after LSG, GERD-Q scores, and EBBS-Q scores) were included in the multivariate linear regression analysis. The results revealed that preoperative type 2 diabetes mellitus, residual gastric volume at 1 month after LSG, and GERD-Q scores were independent risk factors influencing the degree of residual gastric dilation. Moreover, preoperative diabetes, high postoperative EBBS-Q score, and smaller residual stomach volume at 1 month postoperatively were risk factors for early postoperative residual stomach dilation, whereas the other factors were not significantly correlated with postoperative residual stomach dilation (P > 0.05).

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| β value (95%CI) | P value | β value (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age, years | -0.260 (-0.266 to -0.254) | 0.068 | -0.029 (-0.049 to -0.009) | 0.814 |

| Sex, male/female | -0.072 (-0.179 to 0.035) | 0.617 | - | - |

| BMI, kg/m2 | -0.249 (-0.255 to -0.243) | 0.082 | -0.021 (-0.027-0.015) | 0.881 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | -0.092 (-0.205 to 0.021) | 0.527 | - | - |

| Type 2 diabetes, % | 0.294 (0.196-0.392) | 0.039 | 0.268 (0.185-0.351) | 0.024 |

| Chronic gastritis | -0.055 (-0.156 to 0.046) | 0.705 | - | - |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | -0.230 (-0.328 to -0.132) | 0.108 | - | - |

| Smoking, % | -0.061 (-0.186 to 0.064) | 0.673 | - | - |

| Alcohol consumption, % | -0.114 (-0.249 to 0.021) | 0.429 | - | - |

| Laboratory parameter | ||||

| Preoperative fasting blood glucose, mmol/L | 0.043 (0.007-0.079) | 0.764 | - | - |

| Preoperative HbA1c, % | -0.125 (-0.171 to -0.079) | 0.385 | - | - |

| Preoperative WBC, 109/L | 0.074 (0.050-0.098) | 0.607 | - | - |

| Preoperative CRP, mg/L | 0.091 (0.085-0.097) | 0.532 | - | - |

| Resected stomach volume, mL | -0.195 (-0.215 to -0.175) | 0.174 | - | - |

| Spinal length, cm | -0.197 (-0.209 to -0.185) | 0.169 | - | - |

| Residual gastric volume at 1 month | -0.511 (-0.531 to -0.490) | < 0.001 | -0.407 (-0.409 to -0.405) | 0.003 |

| TAVR | -0.095 (-0.147 to -0.043) | 0.511 | - | - |

| Postoperative follow-up indicators | ||||

| GERD-Q score | 0.450 (0.422-0.478) | 0.001 | 0.302 (0.274-0.330) | 0.019 |

| EBBS-Q score | -0.250 (-0.268 to -0.232) | 0.080 | -0.119 (-0.135 to -0.103) | 0.356 |

According to a report by the 7th International Federation for Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders in 2022, LSG was the most commonly performed bariatric surgical procedure worldwide[17]. The multifaceted weight-loss mechanisms of LSG include accelerated gastric emptying, increased postprandial cholecystokinin secretion, increased blood plasma concentrations of glucagon-like peptide-1, and decreased ghrelin release[18-20]. Among these mechanisms of LSG, the reduction in gastric volume is regarded as the most important, as it limits food intake[21]. Nevertheless, the residual gastric volume expands over time, weakening its restrictive effect, which is considered as one of the reasons for in

This study employed CT scanning as the imaging technique for measuring the residual gastric volume and its changes at 1 month and 3 months after LSG, with the aim of investigating the factors associated with residual gastric dilation and its impact on weight loss outcomes in LSG patients. Compared to other imaging modalities, CT scanning provides a rapid and accurate assessment of residual gastric volume[23,24]. Although magnetic resonance imaging is effective, it often requires a longer imaging duration, during which the fluid used to inflate the stomach may pass through the pylorus and become empty, compromising the accuracy of gastric volume assessment[25]. Ultrasonography or upper gastrointestinal contrast is quicker but introduces inaccuracy owing to the operator-dependent nature of this modality[26]. The residual gastric volume was measured at 1 month after LSG to allow sufficient time for early postoperative edema to subside considerably, thus avoiding interference with the volume measurement. Additionally, we ensured that the patients consumed sufficient water to guarantee fullness of the residual stomach. Compared with other methods, this approach better simulates normal physiological conditions and makes the measurement process simpler and more efficient.

Among the 50 included patients, the residual gastric volume at 1 month after LSG was 161.77 ± 55.37 mL. At 3 months after LSG, this volume expanded to 174.43 ± 47.30 mL (P < 0.001), with an average expansion degree of 13.50% ± 17.35%. This expansion was negatively correlated with %TWL at 1 year postoperatively. Vidal et al[12] reported a negative correlation between increased residual gastric volume and weight loss after LSG[12]. Pañella et al[27] also found that the residual gastric volume increased almost twofold between the first and fifth postoperative years, with significant weight regain. Possible reasons for the early expansion of the residual gastric volume may include the patients’ eating habits, increased intraluminal pressure, and low compliance within the gastric tube.

This study found that an excessively small residual stomach was associated with expansion of the residual stomach. Disse et al[28] confirmed this view in their research that sleeve dilatation occurred, especially in subjects with a smaller total gastric volume at baseline (189 mL vs 236 mL, P = 0.02). This may be related to intragastric hypertension caused by the narrow-sleeved stomach. Patients with gastric dilatation had higher reflux scores, which indirectly confirms this view. Seung found that the volume of the residual stomach was positively correlated with food tolerance and that GERD symptoms were more likely to occur in patients with a smaller residual gastric pouch[29].

In patients undergoing LSG, changes in gastric volume can be broadly divided into three stages: Preoperative gastric volume, initial residual gastric volume after surgery, and the secondary expansion of the residual stomach. Existing studies have indicated that although preoperative gastric volume is positively correlated with preoperative BMI, it does not show a significant association with the degree of postoperative weight loss and thus is not suitable as an indicator for predicting postoperative weight reduction outcomes[30]. Notably, the larger the preoperative gastric volume, the greater the volume of gastric tissue typically resected during surgery; however, the key factor influencing weight loss outcomes lies in the proportion of the stomach resected. Research has shown that when the resection proportion reaches or exceeds 87.3%, patients’ percent excess weight loss often exceeds 50%; whereas when the resection proportion is approximately 77.3%, percent excess weight loss usually remains below 40%[31].

Additionally, studies have found that even when residual gastric volumes differ between patient groups, there is no statistically significant difference in total daily caloric intake[28]. This suggests that residual gastric volume primarily limits the amount consumed in a single meal rather than the total caloric intake throughout the day. To adapt to this limitation, patients often compensate by increasing meal frequency, selecting foods with higher energy density, and modifying eating speed and meal timing. Therefore, the relationship between residual gastric volume and total daily caloric intake is not linear. Precisely for this reason, patients with smaller residual gastric volumes are more prone to secondary expansion: To meet energy demands, patients may unconsciously increase portion sizes or eating speed. Over time, repeated overfilling can exert pressure on the residual stomach beyond its compliance and tolerance, ultimately leading to gastric dilation.

Patients with preoperative diabetes were more likely to experience gastric dilatation. This could be secondary to diabetic gastropathy caused by autonomic neuropathy, which slows gastric emptying. Park et al[32] compared gastric tissues from patients with and without diabetes mellitus after gastrectomy, and the results showed that patients with diabetes mellitus had excessive amounts of fibrosis in their gastric smooth muscle and decreased density of interstitial cells of Cajal and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha, which are important for gastric motility. Diabetes-related delayed gastric emptying combined with chronic overdistention of the stomach may explain why patients with diabetes mellitus have larger stomachs[32].

Preventing secondary expansion of the residual stomach is crucial to maintain long-term weight loss after LSG, and requires standardized intraoperative techniques and early postoperative monitoring of residual gastric volume with timely adjustments to treatment strategies. Preoperative surgical planning should be tailored to individual patient characteristics, including defining the specifications of the calibration tube used, determining the starting point of resection from the pylorus, adequate fundus mobilization, and preservation of the angle of His (gastroesophageal junction), all of which collectively determine the postoperative volume and morphology of the residual stomach. During surgery, preservation of vagal and pyloric functions is essential to maintain normal gastric motility. Additionally, while thoroughly removing the fundus, the angle of His should be preserved to avoid functional impairment, and narrowing or twisting should be avoided during staple line reinforcement and omental fixation, thereby reducing the risk of intragastric hypertension and secondary expansion[33]. Gastric residual volume can be postoperatively monitored using upper gastrointestinal contrast studies, CT volumetry, or endoscopic evaluation to detect early signs of dilation or delayed gastric emptying[34], allowing for timely dietary adjustments and appropriate medical interventions to prevent further morphological deterioration and weight return.

This study had several limitations. First, its retrospective single-center design may have resulted in incomplete data collection and potential information bias. Second, the sample size of 50 patients may have been too small to generalize the findings to a broader population of patients undergoing LSG. In addition, the influence of unmeasured or uncontrolled confounding factors cannot be ruled out. Therefore, further validation of these findings is needed, which requires additional clinical data and confirmation through prospective randomized trials. Lastly, while 3D CT reconstruction offers detailed measurements of residual gastric volume, variability in imaging techniques and interpretation by different clinicians can introduce measurement errors.

In summary, this study revealed that the residual stomach underwent mild expansion within the first three months after LSG; this was associated with weight loss at 12 months. The initial small sleeve volume, preoperative diabetes mellitus, and postoperative reflux were associated with a higher risk of sleeve dilatation. These findings suggest that close monitoring of the residual stomach volume in the early postoperative period is crucial for optimizing and maintaining long-term weight loss effects. Therefore, high-risk factors for residual stomach expansion (such as diabetes and postoperative gastroesophageal reflux) should be identified early in the perioperative period, and targeted in

LSG is an effective bariatric surgery for weight loss, but some patients experience weight regain or insufficient weight loss, which may be attributed to residual gastric dilation. This study, utilizing 3D CT reconstruction, demonstrates that residual gastric volume significantly increases over the first three months following LSG. The degree of dilation is correlated with long-term weight loss outcomes, specifically the %TWL at one year. Risk factors contributing to gastric dilation include preoperative type 2 diabetes, the residual gastric volume at one month postoperatively, and the presence of GERD. These findings underscore the importance of early identification and management of residual gastric dilation to improve postoperative outcomes and prevent weight regain.

| 1. | Francque SM, Marchesini G, Kautz A, Walmsley M, Dorner R, Lazarus JV, Zelber-Sagi S, Hallsworth K, Busetto L, Frühbeck G, Dicker D, Woodward E, Korenjak M, Willemse J, Koek GH, Vinker S, Ungan M, Mendive JM, Lionis C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A patient guideline. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lobstein T. Obesity prevention and the Global Syndemic: Challenges and opportunities for the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2019;20 Suppl 2:6-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | O'Kane M, Parretti HM, Pinkney J, Welbourn R, Hughes CA, Mok J, Walker N, Thomas D, Devin J, Coulman KD, Pinnock G, Batterham RL, Mahawar KK, Sharma M, Blakemore AI, McMillan I, Barth JH. British Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society Guidelines on perioperative and postoperative biochemical monitoring and micronutrient replacement for patients undergoing bariatric surgery-2020 update. Obes Rev. 2020;21:e13087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Ramos A, Shikora S, Kow L. Bariatric Surgery Survey 2018: Similarities and Disparities Among the 5 IFSO Chapters. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1937-1948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 72.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Peterli R, Wölnerhanssen BK, Peters T, Vetter D, Kröll D, Borbély Y, Schultes B, Beglinger C, Drewe J, Schiesser M, Nett P, Bueter M. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SM-BOSS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319:255-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 693] [Cited by in RCA: 923] [Article Influence: 115.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Baheeg M, Elgohary SA, Tag-Eldin M, Hegab AME, Shehata MS, Osman EM, Eid M, Abdurakhmanov Y, Lamlom M, Ali HA, Elhawary A, Mahmoud M, Basiony M, Mohammmed Y, Hasan A. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in Egyptian patients with morbid obesity. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;73:103235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Giannopoulos S, Kapsampelis P, Pokala B, Nault Connors JD, Hilgendorf W, Timsina L, Clapp B, Ghanem O, Kindel TL, Stefanidis D. Bariatric Surgeon Perspective on Revisional Bariatric Surgery (RBS) for Weight Recurrence. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2023;19:972-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Clapp B, Wynn M, Martyn C, Foster C, O'Dell M, Tyroch A. Long term (7 or more years) outcomes of the sleeve gastrectomy: a meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:741-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Langer FB, Bohdjalian A, Felberbauer FX, Fleischmann E, Reza Hoda MA, Ludvik B, Zacherl J, Jakesz R, Prager G. Does gastric dilatation limit the success of sleeve gastrectomy as a sole operation for morbid obesity? Obes Surg. 2006;16:166-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Deguines JB, Verhaeghe P, Yzet T, Robert B, Cosse C, Regimbeau JM. Is the residual gastric volume after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy an objective criterion for adapting the treatment strategy after failure? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:660-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Benaiges D, Más-Lorenzo A, Goday A, Ramon JM, Chillarón JJ, Pedro-Botet J, Flores-Le Roux JA. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: More than a restrictive bariatric surgery procedure? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11804-11814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 12. | Vidal P, Ramón JM, Busto M, Domínguez-Vega G, Goday A, Pera M, Grande L. Residual gastric volume estimated with a new radiological volumetric model: relationship with weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2014;24:359-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hany M, Ibrahim M, Zidan A, Agayaby ASS, Aboelsoud MR, Gaballah M, Torensma B. Two-Year Results of the Banded Versus Non-banded Re-sleeve Gastrectomy as a Secondary Weight Loss Procedure After the Failure of Primary Sleeve Gastrectomy: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes Surg. 2023;33:2049-2063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Noel P, Nedelcu M, Nocca D, Schneck AS, Gugenheim J, Iannelli A, Gagner M. Revised sleeve gastrectomy: another option for weight loss failure after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1096-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Spaggiari G, Santi D, Budriesi G, Dondi P, Cavedoni S, Leonardi L, Delvecchio C, Valentini L, Bondi M, Miloro C, Toschi PF. Eating Behavior after Bariatric Surgery (EBBS) Questionnaire: a New Validated Tool to Quantify the Patients' Compliance to Post-Bariatric Dietary and Lifestyle Suggestions. Obes Surg. 2020;30:3831-3838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J, Vakil N, Halling K, Wernersson B, Lind T. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1030-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 530] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, Aminian A, Angrisani L, Cohen RV, de Luca M, Faria SL, Goodpaster KPS, Haddad A, Himpens JM, Kow L, Kurian M, Loi K, Mahawar K, Nimeri A, O'Kane M, Papasavas PK, Ponce J, Pratt JSA, Rogers AM, Steele KE, Suter M, Kothari SN. 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2023;33:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 136.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Steenackers N, Vanuytsel T, Augustijns P, Tack J, Mertens A, Lannoo M, Van der Schueren B, Matthys C. Adaptations in gastrointestinal physiology after sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:225-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sista F, Abruzzese V, Clementi M, Carandina S, Cecilia M, Amicucci G. The effect of sleeve gastrectomy on GLP-1 secretion and gastric emptying: a prospective study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aukan MI, Skårvold S, Brandsaeter IØ, Rehfeld JF, Holst JJ, Nymo S, Coutinho S, Martins C. Gastrointestinal hormones and appetite ratings after weight loss induced by diet or bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023;31:399-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Miras AD, le Roux CW. Mechanisms underlying weight loss after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:575-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Velapati SR, Shah M, Kuchkuntla AR, Abu-Dayyeh B, Grothe K, Hurt RT, Mundi MS. Weight Regain After Bariatric Surgery: Prevalence, Etiology, and Treatment. Curr Nutr Rep. 2018;7:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Karcz WK, Kuesters S, Marjanovic G, Suesslin D, Kotter E, Thomusch O, Hopt UT, Felmerer G, Langer M, Baumann T. 3D-MSCT gastric pouch volumetry in bariatric surgery-preliminary clinical results. Obes Surg. 2009;19:508-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Robert M, Pechoux A, Marion D, Laville M, Gouillat C, Disse E. Relevance of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass volumetry using 3-dimensional gastric computed tomography with gas to predict weight loss at 1 year. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:26-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fiorillo C, Quero G, Dallemagne B, Curcic J, Fox M, Perretta S. Effects of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy on Gastric Structure and Function Documented by Magnetic Resonance Imaging Are Strongly Associated with Post-operative Weight Loss and Quality of Life: a Prospective Study. Obes Surg. 2020;30:4741-4750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Deręgowska-Cylke M, Palczewski P, Błaż M, Cylke R, Ziemiański P, Szeszkowski W, Lisik W, Gołębiowski M. Radiographic Measurement of Gastric Remnant Volume After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Assessment of Reproducibility and Correlation with Weight Loss. Obes Surg. 2022;32:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pañella C, Busto M, González A, Serra C, Goday A, Grande L, Pera M, Ramón JM. Correlation of Gastric Volume and Weight Loss 5 Years Following Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2020;30:2199-2205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Disse E, Pasquer A, Pelascini E, Valette PJ, Betry C, Laville M, Gouillat C, Robert M. Dilatation of Sleeve Gastrectomy: Myth or Reality? Obes Surg. 2017;27:30-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Choi SJ, Kim SM. Intrathoracic Migration of Gastric Sleeve Affects Weight Loss as well as GERD-an Analysis of Remnant Gastric Morphology for 100 Patients at One Year After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2021;31:2878-2886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Salman MA, Elshazli M, Shaaban M, Esmat MM, Salman A, Ibrahim HMM, Tourky M, Helal A, Mahmoud AA, Aljarad F, Saadawy AMI, Shaaban HE, Mansour D. Correlation Between Preoperative Gastric Volume and Weight Loss After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:8135-8140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Elbanna H, Emile S, El-Hawary GE, Abdelsalam N, Zaytoun HA, Elkaffas H, Ghanem A. Assessment of the Correlation Between Preoperative and Immediate Postoperative Gastric Volume and Weight Loss After Sleeve Gastrectomy Using Computed Tomography Volumetry. World J Surg. 2019;43:199-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Park KS, Cho KB, Hwang IS, Park JH, Jang BI, Kim KO, Jeon SW, Kim ES, Park CS, Kwon JG. Characterization of smooth muscle, enteric nerve, interstitial cells of Cajal, and fibroblast-like cells in the gastric musculature of patients with diabetes mellitus. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10131-10139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Rosenthal RJ; International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel, Diaz AA, Arvidsson D, Baker RS, Basso N, Bellanger D, Boza C, El Mourad H, France M, Gagner M, Galvao-Neto M, Higa KD, Himpens J, Hutchinson CM, Jacobs M, Jorgensen JO, Jossart G, Lakdawala M, Nguyen NT, Nocca D, Prager G, Pomp A, Ramos AC, Rosenthal RJ, Shah S, Vix M, Wittgrove A, Zundel N. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:8-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 713] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 48.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Robb HD, Arif A, Narendranath RM, Das B, Alyaqout K, Lynn W, Aal YA, Ashrafian H, Fehervari M. How is 3D modeling in metabolic surgery utilized and what is its clinical benefit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2025;111:3159-3168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/