Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112238

Revised: September 26, 2025

Accepted: November 18, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 155 Days and 1.9 Hours

Patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their families often experience reduced quality of life (QoL) and heightened negative emotions. Death education may offer benefits, but evidence in this context is limited.

To investigate the impact of a systematic “four-step death education” intervention on the QoL and negative emotions of postoperative patients with advanced eso

A retrospective cohort study was conducted involving 235 patients with advanced esophageal cancer who underwent surgery at The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University from June 2021 to June 2024. The participants were assigned to either the standard care group (SCG, n = 127) or the “four-step death education” group (FDEG, n = 108) on the basis of the received intervention. SCG received standard care and basic psychological support, and FDEG additionally received a four-stage death education program encompassing information provision, emotional support, life review and meaning exploration, and end-of-life care preparation. QoL and negative emotion levels were measured using validated instruments: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire Core 30 for patient QoL, the Family QoL Survey, the Zarit Burden Interview for caregiver burden, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, the Self-Rating Depression Scale, and the Attitudes Toward Life and Death Scale. Assessments were conducted at baseline and 3 months post-intervention.

Baseline characteristics were comparable between groups. At 3 months, FDEG demonstrated significantly improved symptom and functional domain QoL scores in several areas, including fatigue, nausea, insomnia, loss of appetite, and physical and emotional functioning. FDEG reported increased family QoL and reduced caregiver burden. The patients and caregivers in FDEG showed superior improvements in sleep quality and greater reductions in anxiety and depression scores than those in SCG. Post-intervention, FDEG exhibited more positive attitudes toward death.

The postoperative “four-step death education” intervention enhances QoL, relieves caregiver burden, and reduces negative emotions among patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their caregivers, supporting broadened implementation of structured death education programs in palliative care settings.

Core Tip: This study evaluated the impact of “four-step death education” intervention on the quality of life and negative emotions of postoperative patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their caregivers. The intervention, which included information provision, emotional support, life review, meaning exploration, and end-of-life care preparation, showed improvements in quality of life, reduced caregiver burden, and alleviated anxiety and depression. Key mechanisms involved knowledge empowerment, emotional release, meaning creation, and collaborative end-of-life planning. These findings suggest that incorporating such death education into standard palliative care may enhance the overall well-being of patients and families facing terminal illness, though further research is needed.

- Citation: Wen LL, Li JY, Zhang SY. Impact of “four-step” death education on life quality and negative emotions in advanced esophageal cancer patients and families. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 112238

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/112238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112238

Esophageal cancer remains a significant global health challenge, with an estimated 604100 new cases and 544076 deaths worldwide in 2020, making it the seventh most common cancer and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related mortality[1]. Despite advances in diagnostic modalities and treatment regimens, the prognosis for advanced esophageal cancer after surgery remains poor, with a 5-year relative survival rate of less than 20% for all stages combined and less than 5% for those with metastatic disease[2]. The majority of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, resulting in substantial symptom burden, including dysphagia, weight loss, fatigue, and pain, alongside marked disruptions in psychosocial, emotional, and existential domains[3].

Beyond symptom control, quality of life (QoL) emerges as a critical objective in the care of patients with advanced esophageal cancer[4]. Numerous studies have highlighted that patients experience profound psychological distress encompassing anxiety, depression, fear of recurrence or death, and anticipatory grief[5]. The impact extends to primary caregivers, often family members, who frequently encounter emotional exhaustion, caregiver burden, and compromised well-being as they navigate the demands of caregiving and impending loss[6]. Evidence suggests that negative emotions and psychological distress are not only prevalent but also persistent, at times exacerbating physical symptoms and impeding engagement with care[7].

While palliative care integration and psychosocial support are recognized as essential components in oncology, a need for structured interventions targeting existential suffering, death anxiety, and meaning-making at the end of life remains unmet[8]. Death education, a construct that encompasses systematic discussion, reflection, and planning regarding mortality, has gained increasing attention as a therapeutic modality in oncology and palliative care[9]. Death education has been shown to reduce fear of death; facilitate acceptance; improve communication among patients, families, and healthcare providers; and enhance adaptation to the dying process[10]. It encourages patients and families to articulate values and wishes, supports advance care planning, and provides a framework to explore personal and cultural attitudes toward dying and bereavement[11].

The “four-step death education” model is a multicomponent intervention incorporating information provision, emotional support, life review and meaning exploration, and end-of-life care preparation[11]. Preliminary evidence indicates that such stepwise interventions may foster increased psychological resilience, reduce anxiety and depression, improve QoL, and promote enhanced family cohesion and caregiver adjustment[12]. However, most prior studies have focused on general palliative care populations or healthcare professionals rather than targeting the unique needs of patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their families[12].

Given the high prevalence of psychological distress, existential suffering, and compromised QoL in this population, an evaluation of structured death education interventions specifically tailored for advanced esophageal cancer is critically needed. Such research may provide important insights into optimizing supportive care, alleviating negative emotions, and improving overall outcomes for patients and their families facing end-of-life challenges. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the impact of the “four-step death education” intervention on the QoL and negative emotional states of patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their primary caregivers. By elucidating the efficacy and potential mechanisms of this intervention, this research seeks to inform future psychosocial and palliative care practices for individuals con

This study is a retrospective cohort study aimed at evaluating the impact of “four-step death education” on the QoL and negative emotions of patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their families. The study participants were selected from patients diagnosed with advanced esophageal cancer who received treatment and underwent surgery at The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University between June 2021 and June 2024, totaling 235 patients. These patients were divided into two groups on the basis of the treatment they received: Standard care group (SCG) and “four-step death education” group (FDEG). SCG included 127 patients, and FDEG included 108 patients.

During the study period, SCG received standard medical care and basic psychological support but did not receive any additional death education interventions. Standard care included postoperative recovery guidance, medication management, nutritional support, and regular follow-ups. Basic psychological support consisted of unstructured general psychological comfort and disease-related knowledge provided by responsible nurses, lasting about 15 minutes each time, on the basis of patient needs during rounds or follow-up visits, without a fixed frequency or formal course schedule. By contrast, FDEG received systematic death education interventions in addition to standard care. These interventions were conducted by senior nurses who received unified training and a professional psychologist with a background in psycho-oncology. These interventions included four stages: Information provision, emotional support, life review and meaning exploration, and end-of-life care preparation. The education interventions started 1 week after surgery and lasted 3 months. Each patient and their primary caregiver participated in one session per week, with each session consisting of two 30 minutes interventions totaling 1 hours. This resulted in a total of 12 sessions over the course of the study. Each session focused on one specific component, completing a full “four-step” cycle every 2 weeks. Education after discharge was conducted online.

The information provision stage included content on disease progression, symptom management, potential complications, and available medical care resources. Through structured lectures, this study ensured that patients and their families fully understood the relevant information. The emotional support stage utilized group discussions led by a professional psychologist. Standardized interview guidelines were used to help patients express fears, regrets, or anxieties, and visualization tools such as emotional maps were employed to facilitate emotional expression and processing. The life review and meaning exploration stage involved guided reminiscence activities, encouraging patients to review their life experiences, identify values and meanings, and address unresolved wishes. The end-of-life care preparation stage provided information on advance directives (ADs) and end-of-life decision-making, assisting patients in communicating their medical preferences, after-death arrangements, and farewell methods with their families and completing necessary paperwork when needed.

All interventions were conducted by professionals with a background in clinical psychology. These individuals received specialized training to ensure the consistency and quality of the interventions. Each trainer adhered to a standardized intervention manual and regularly participated in adherence check meetings to ensure that the interventions were implemented in accordance with the predetermined protocol. The QoL and negative emotions of the patients and their primary caregivers were assessed before the intervention and 3 months after the intervention.

This study, being a retrospective investigation, utilized de-identified patient information only. All data were anonymized to ensure that patient privacy was fully protected and the data could not be traced back to any individual during the analysis process. Consequently, this study did not have any impact on the treatment or prognosis of the patients. Given these circumstances, this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University (Approval No. 2024KS141), which granted an exemption from the requirement to obtain informed consent from the participants.

Patients: (1) Aged 18 years or older; (2) Diagnosed with advanced esophageal cancer (stage III or stage IV) through pathology or imaging and received surgical treatment[13]; (3) Able to understand and respond to questionnaire content without severe cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia); (4) Expected survival of at least 3 months; and (5) Complete data available.

Caregivers: (1) Aged 18 years or older; (2) Primary caregiver for the patient, living with or in close contact with the patient; and (3) Able to understand and respond to questionnaire content without severe cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia).

Patients: (1) Simultaneously suffering from other major diseases that could significantly affect QoL (e.g., end-stage heart failure or renal failure); (2) Suffering from severe mental disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder, schizophrenia); (3) Presence of severe language barriers preventing effective communication and questionnaire completion; (4) Received similar death education or psychological support interventions within the past 3 months; and (5) Experiencing highly unstable vital signs requiring urgent medical intervention.

Caregivers: (1) Bearing other significant responsibilities or pressures preventing them from focusing on patient care; (2) Suffering from severe mental disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder or schizophrenia); and (3) Presence of severe language barriers preventing effective communication and questionnaire completion.

Baseline data sources: The baseline data for patients and their caregivers were sourced from the medical record system. During the initial consultation prior to the intervention, the demographic information, disease characteristics, and treatment history of the patients were surveyed. Surgical information, such as surgical objectives, types of surgery, and surgical duration, were obtained from the surgical records.

Nutritional status was graded into three categories: Grade A, grade B, and grade C[14]. Grade A indicated a well-nourished state where patients showed no significant weight loss (less than 5% in the past 3-6 months), had adequate dietary intake with no signs of nutritional deficiency, exhibited normal physical examination findings without evidence of muscle wasting or fat loss, and maintained normal functional status. Grade B signified a moderately malnourished state characterized by weight loss between 5% and 10%, some reduction in dietary intake, mild muscle wasting or fat loss on physical examination, and minor functional impairments. Grade C represented a severely malnourished state with substantial weight loss exceeding 10%, markedly reduced dietary intake, clear signs of severe muscle wasting and fat loss, and significant functional impairments.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status was graded on the basis of the patient’s ability to perform daily activities and their overall health condition[15]. A score of 1 indicated that the patient was fully active but restricted in physically strenuous activity; they could walk and manage light work but were unable to do heavy physical labor. A score of 2 signified that the patient was capable of self-care and could walk about but was unable to work; they were either bedridden for less than 50% of waking hours or had significant limitations in physical activity due to symptoms such as fatigue or shortness of breath.

According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Eighth Edition tumor (T)-nodes (N)-metastasis (M) staging system, stage III esophageal cancer included tumors that were either confined to the esophageal wall with regional lymph node metastasis (T0-2N1M0) or had invaded the outer layer of the esophageal wall with more extensive lymph node involvement (T3N1-3M0, T4aN0-2M0)[16]. Stage IV esophageal cancer encompassed all cases of distant metastasis, indicating that the tumor had spread to other organs or sites such as the pleura, pericardium, adjacent organs, or distant lymph nodes (any T, any N, or M1).

The assessment of resection margins during surgery involves evaluating the distance between the tumor and the surgical margins when the tumor is removed[17]. R0 resection indicates “no residual tumor”, meaning that no cancer cells are observed at the surgical margins under a microscope. R1 resection indicates “residual tumor”, meaning that cancer cells are observed at the surgical margins under a microscope. R2 resection indicates “macroscopic residual tumor”, meaning that during the surgery, the surgeon can directly observe unremoved tumor tissue.

Patient QoL: The QoL of patients was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire Core 30[18]. The primary focus was on the symptom and functional scales. The symptom scales include fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties, comprising a total of 12 items. Each item is scored from 1 to 4, where 1 indicates “no symptoms at all” and 4 indicates “very severe” (severe symptoms). The raw scores are then transformed to a scale of 0-100, where higher scores indicate more severe symptoms and thus a lower QoL.

The functional scales include physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, and social functioning, with a total of 14 items. Each item is scored from 1 to 4, where 1 indicates complete inability to perform the function and 4 indicates full ability to perform the function. Higher scores indicate better functional status and thus a higher QoL.

Family QoL for patients and their caregivers: The overall family QoL for patients and their caregivers was assessed using the Family QoL Survey[19]. Family QoL Survey consists of 18 questions covering four domains: Family activities (six questions), emotional support (four questions), economic status (five questions), and family member satisfaction (three questions). Each question is scored on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates “very dissatisfied” and 5 indicates “very satisfied”. Higher scores indicate a higher family QoL.

Caregiver burden assessment: Caregiver burden was assessed using the Zarit Burden Interview[20]. Zarit Burden Interview includes 21 items covering four domains: Emotional burden (15 items), time dependence burden (two items), developmental burden (two items), and social burden (two items). Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates “never” and 4 indicates “almost always”. Lower scores indicate a lighter perceived burden for the primary caregiver.

Sleep quality assessment: The sleep quality of patients and their primary caregivers was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index[21]. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index consists of seven components: Subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored on a scale from 0 to 3, with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 21. Lower scores indicate better sleep quality.

Assessment of negative emotions: Anxiety levels were assessed using the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)[22]. SAS consists of 20 items describing anxiety symptoms, each rated on a 4-point scale from 1 to 4, corresponding to “none or a little of the time”, “some of the time”, “a good part of the time”, and “most or all of the time”. Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety. Depression levels were assessed using the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)[23]. SDS includes 20 items describing depressive symptoms, each with four options similar to SAS, corresponding to different frequencies or intensities: “None or a little of the time”, “some of the time”, “a good part of the time”, and “most or all of the time”. Higher scores indicate more severe depression.

Patient attitudes toward death: The Attitude Towards Life and Death Scale was used to assess patients’ basic attitudes towards life and death. Attitude Towards Life and Death Scale is a tool independently developed and validated by the authors’ hospital, designed to evaluate individuals’ views on life, their perceptions of death, and their life values. The scale consists of 15 items, each rated on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates “strongly disagree” and 5 indicates “strongly agree”. Higher scores indicate a more positive attitude towards death, meaning lower levels of fear and avoidance of death and higher psychological adaptability and sense of meaning when facing the end of life. Formal reliability and validity analyses demonstrated that Attitude Towards Life and Death Scale had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.813), indicating high consistency among the scale items.

For the statistical analysis, SPSS (version 29.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was used to process and analyze the collected data. Categorical variables were summarized using n (%). For categorical data, χ2 test was employed, denoted as χ2. Continuous data that followed a normal distribution were reported as means ± SD. Inter-group comparisons for normally distributed continuous data were conducted using independent sample t-tests.

A post-hoc power analysis was conducted to validate the rationality of the sample size in this study. Based on the results from previous studies, a moderate effect size for the QoL scores was assumed (Cohen’s d = 0.5) and this study aimed to achieve at least 80% statistical power at an alpha level of 0.05. Using G*Power software, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be approximately 64 patients per group. Given the actual sample sizes of 127 patients in SCG and 108 patients in FDEG, the sample size was sufficient to detect the expected effect size.

At baseline, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups across any measured patient or caregiver characteristics (Table 1). Patient demographics including age (SCG: 58.73 ± 6.83 years vs FDEG: 59.41 ± 6.78 years, P = 0.442) and gender distribution (female: 24.41% vs 26.85%, P = 0.669) were comparable, as were body mass index, marital status, rates of smoking and alcohol consumption, educational level, nutritional status, serum albumin, prevalence of hypertension and diabetes, family cancer history, and duration of illness (all P > 0.05). Disease characteristics, such as primary tumor location, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, and disease stage, showed similar distributions between groups (all P > 0.05). Prior treatments, including surgical objectives, types of surgery, blood loss, resection margins, and postoperative complications, did not differ significantly (all P > 0.05). The family caregiver baseline data were comparable regarding age (P = 0.620), gender (P = 0.806), relationship to the patient (P = 0.790), and employment status (P = 0.734). These findings confirmed that the SCG and FDEG cohorts were well matched at study entry.

| Index | SC group (n = 127) | FDE group (n = 108) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age | 58.73 ± 6.83 | 59.41 ± 6.78 | 0.770 | 0.442 |

| Gender | 0.183 | 0.669 | ||

| Female | 31 (24.41) | 29 (26.85) | ||

| Male | 96 (75.59) | 79 (73.15) | ||

| BMI | 22.36 ± 1.84 | 22.19 ± 1.68 | 0.707 | 0.480 |

| Marital status(married) | 109 (85.83) | 100 (92.59) | 2.715 | 0.099 |

| Smoking history | 38 (29.92) | 33 (30.56) | 0.011 | 0.916 |

| Alcohol consumption history | 91 (71.65) | 77 (71.30) | 0.004 | 0.952 |

| Education level | 0.374 | 0.830 | ||

| Elementary school or below | 35 (27.56) | 26 (24.07) | ||

| Junior high school/high school | 59 (46.46) | 53 (49.07) | ||

| University or above | 33 (25.98) | 29 (26.85) | ||

| Nutritional status | 0.004 | 0.998 | ||

| Grade A | 19 (14.96) | 16 (14.81) | ||

| Grade B | 96 (75.59) | 82 (75.93) | ||

| Grade C | 12 (9.45) | 10 (9.26) | ||

| Serum albumin | 30.51 ± 3.37 | 31.08 ± 3.44 | 1.285 | 0.200 |

| Hypertension | 21 (16.54) | 15 (13.89) | 0.315 | 0.575 |

| Diabetes | 12 (9.45) | 10 (9.26) | 0.002 | 0.960 |

| Family history | 43 (33.86) | 36 (33.33) | 0.007 | 0.932 |

| Duration of illness (months) | 3.16 ± 0.65 | 3.23 ± 0.69 | 0.768 | 0.443 |

| Primary tumor location | 0.038 | 0.981 | ||

| Esophagus/gastroesophageal junction (I, II) | 101 (79.53) | 85 (78.70) | ||

| Gastroesophageal junction III/cardia | 14 (11.02) | 12 (11.11) | ||

| Gastric/sub-cardia/stomach | 12 (9.45) | 11 (10.19) | ||

| ECOG status | 0.002 | 0.962 | ||

| 1 | 78 (61.42) | 66 (61.11) | ||

| 2 | 49 (38.58) | 42 (38.89) | ||

| Disease stage | 0.001 | 0.970 | ||

| III | 92 (72.44) | 78 (72.22) | ||

| IV | 35 (27.56) | 30 (27.78) | ||

| Surgical objectives | 0.315 | 0.575 | ||

| Curative surgery | 38 (29.92) | 36 (33.33) | ||

| Palliative surgery | 89 (70.08) | 72 (66.67) | ||

| Types of surgery | 0.203 | 0.904 | ||

| Minimally invasive | 53 (41.73) | 46 (42.59) | ||

| Open surgery | 26 (20.47) | 24 (22.22) | ||

| Hybrid minimally invasive | 48 (37.80) | 38 (35.19) | ||

| Blood loss (mL) | 322.81 ± 98.47 | 325.26 ± 101.68 | 0.187 | 0.852 |

| Resection margins (< 1 mm) | 0.042 | 0.979 | ||

| Free (R0) | 72 (56.69) | 61 (56.48) | ||

| Involved (R1) | 46 (36.22) | 40 (37.04) | ||

| R2 | 9 (7.09) | 7 (6.48) | ||

| Postoperative complications | ||||

| Anastomotic leak | 7 (5.51) | 5 (4.63) | 0.094 | 0.759 |

| Pulmonary infection | 10 (7.87) | 7 (6.48) | 0.169 | 0.681 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury | 4 (3.15) | 3 (2.78) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Surgical duration (minutes) | 214.63 ± 41.36 | 211.43 ± 37.72 | 0.614 | 0.540 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 14.28 ± 2.83 | 13.96 ± 3.12 | 0.833 | 0.406 |

| Family member information | ||||

| Age | 43.25 ± 8.14 | 42.72 ± 8.26 | 0.496 | 0.620 |

| Gender | 0.060 | 0.806 | ||

| Female | 97 (76.38) | 81 (75.00) | ||

| Male | 30 (23.62) | 27 (25.00) | ||

| Relationship to patient | 0.071 | 0.790 | ||

| Spouse/partner | 79 (62.20) | 69 (63.89) | ||

| Child | 48 (37.80) | 39 (36.11) | ||

| Employment status | 0.618 | 0.734 | ||

| Employed | 50 (39.37) | 48 (44.44) | ||

| Retired | 41 (32.28) | 32 (29.63) | ||

| Unemployed | 36 (28.35) | 28 (25.93) |

At baseline, no statistically significant differences existed between SCG and FDEG in any symptom domain QoL scores, including fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulty (all P > 0.05, Table 2). Post-intervention, significant differences were observed in several symptoms. Fatigue scores were lower in FDEG than in SCG (P = 0.046), indicating less reported fatigue in FDEG. Similarly, nausea and vomiting scores were lower in FDEG (P = 0.031), suggesting better control of these symptoms. Insomnia scores were also lower in FDEG (P = 0.032), suggesting better sleep quality in this group. Additionally, loss of appetite was significantly lower in FDEG (P = 0.034), indicating less severe appetite issues than SCG. For other symptoms, including pain, dyspnea, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulty, no significant differences were found between the two groups post-intervention (all P > 0.05).

| Index | SC group (n = 127) | FDE group (n = 108) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Pre-intervention symptoms | ||||

| Fatigue | 67.33 ± 7.43 | 68.04 ± 7.21 | 0.743 | 0.458 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 72.14 ± 3.55 | 72.59 ± 3.89 | 0.922 | 0.358 |

| Pain | 87.28 ± 6.44 | 88.11 ± 6.18 | 1.007 | 0.315 |

| Dyspnea | 62.56 ± 6.34 | 63.62 ± 6.59 | 1.259 | 0.209 |

| Insomnia | 83.66 ± 7.35 | 84.23 ± 7.49 | 0.586 | 0.558 |

| Loss of appetite | 58.95 ± 4.57 | 59.23 ± 4.43 | 0.468 | 0.640 |

| Constipation | 59.67 ± 5.72 | 60.33 ± 5.45 | 0.896 | 0.371 |

| Diarrhea | 43.89 ± 6.33 | 44.17 ± 5.48 | 0.351 | 0.726 |

| Financial difficulty | 40.33 ± 4.42 | 40.67 ± 4.39 | 0.591 | 0.555 |

| Post-intervention symptoms | ||||

| Fatigue | 62.68 ± 6.40 | 61.03 ± 6.12 | 2.003 | 0.046 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 63.84 ± 4.56 | 62.53 ± 4.75 | 2.165 | 0.031 |

| Pain | 77.16 ± 5.18 | 76.23 ± 4.84 | 1.417 | 0.158 |

| Dyspnea | 51.32 ± 5.86 | 50.67 ± 5.19 | 0.887 | 0.376 |

| Insomnia | 75.13 ± 5.61 | 73.57 ± 5.46 | 2.152 | 0.032 |

| Loss of appetite | 42.61 ± 6.56 | 40.88 ± 5.78 | 2.131 | 0.034 |

| Constipation | 47.13 ± 5.82 | 46.65 ± 5.67 | 0.640 | 0.523 |

| Diarrhea | 37.59 ± 4.36 | 36.72 ± 4.22 | 1.555 | 0.121 |

| Financial difficulty | 36.15 ± 4.82 | 35.67 ± 4.69 | 0.768 | 0.443 |

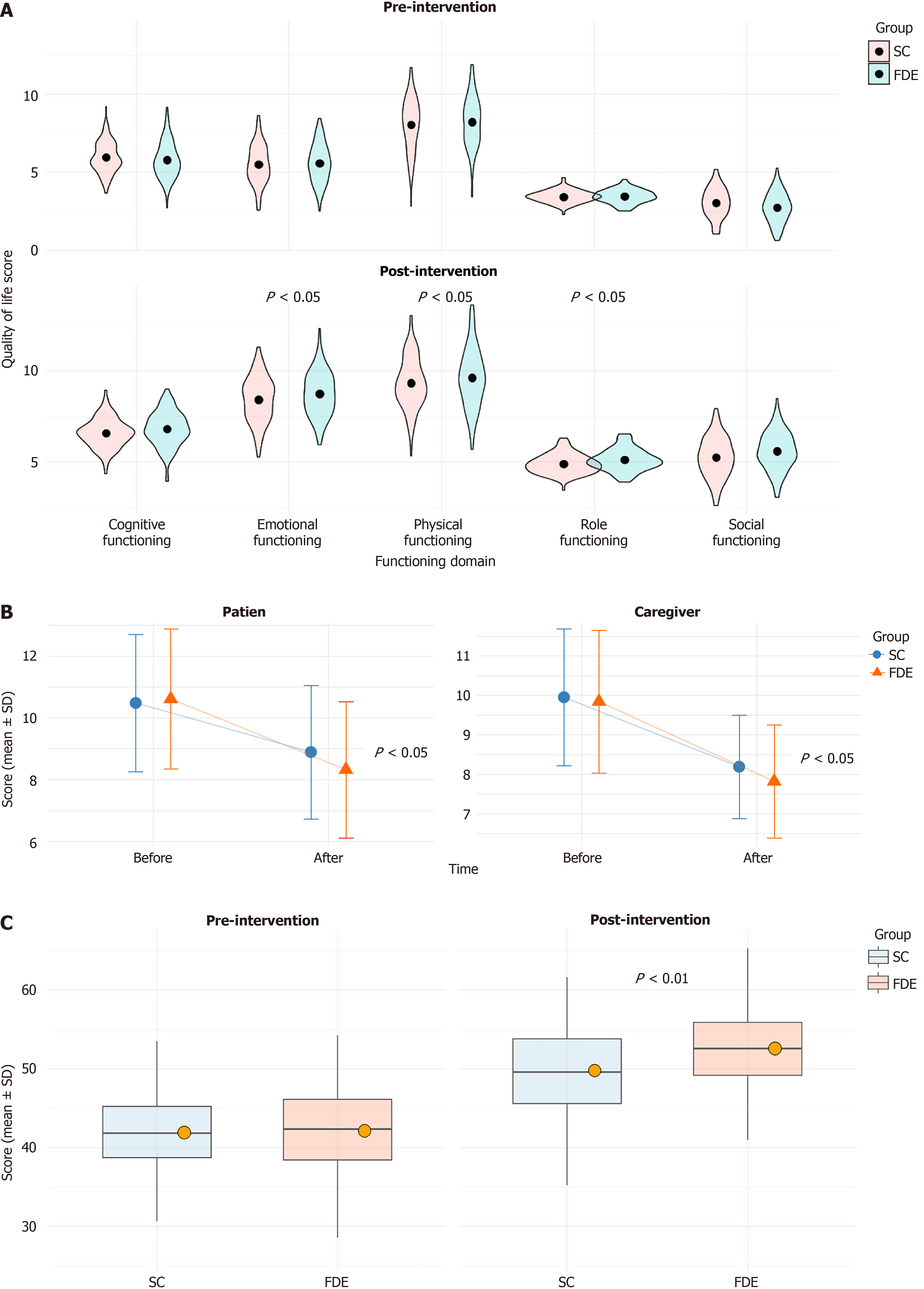

At baseline, significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning scores (all P > 0.05, Figure 1A). After the intervention, FDEG showed significantly better outcomes in physical functioning (9.57 ± 1.57 vs 9.16 ± 1.52, P = 0.045), role functioning (5.02 ± 0.60 vs 4.86 ± 0.57, P = 0.040), and emotional functioning (8.79 ± 1.27 vs 8.45 ± 1.18, P = 0.034) than SCG. No statistically significant post-intervention differences were observed in cognitive functioning or social functioning between the two groups (both P > 0.05).

No significant differences were observed in the family QoL measures, including family activities, emotional support, economic status, and family member satisfaction, between the two groups prior to intervention (all P > 0.05, Table 3). Following the intervention, FDEG demonstrated significantly higher scores in family activities (22.39 ± 2.65 vs 21.66 ± 2.73, P = 0.041), emotional support (13.89 ± 2.42 vs 13.21 ± 2.37, P = 0.029), and family member satisfaction (13.84 ± 1.59 vs 13.36 ± 1.61, P = 0.021) than SCG. Economic status showed no significant difference between the two groups post-intervention (P = 0.956).

| Index | SC group (n = 127) | FDE group (n = 108) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Pre-intervention | ||||

| Family activities | 18.35 ± 2.48 | 18.14 ± 2.52 | 0.639 | 0.523 |

| Emotional support | 9.52 ± 1.98 | 9.41 ± 2.03 | 0.440 | 0.661 |

| Economic status | 17.83 ± 1.96 | 17.78 ± 1.86 | 0.205 | 0.838 |

| Family member satisfaction | 11.39 ± 1.55 | 11.42 ± 1.62 | 0.106 | 0.916 |

| Post-intervention | ||||

| Family activities | 21.66 ± 2.73 | 22.39 ± 2.65 | 2.057 | 0.041 |

| Emotional support | 13.21 ± 2.37 | 13.89 ± 2.42 | 2.194 | 0.029 |

| Economic status | 18.23 ± 2.03 | 18.25 ± 1.96 | 0.055 | 0.956 |

| Family member satisfaction | 13.36 ± 1.61 | 13.84 ± 1.59 | 2.321 | 0.021 |

At baseline, no significant differences were found in the caregiver family QoL measures, including family activities, emotional support, economic status, and family member satisfaction, between the two groups (all P > 0.05, Table 4). After the intervention, the caregivers of FDEG reported significantly higher family activities scores (24.01 ± 2.29 vs 23.35 ± 2.37, P = 0.031), greater emotional support (14.85 ± 1.87 vs 14.34 ± 1.99, P = 0.043), and higher family member satisfaction (13.92 ± 1.28 vs 13.55 ± 1.23, P = 0.025) than those of SCG, whereas the economic status scores did not differ significantly between the groups (P = 0.770).

| Index | SC group (n = 127) | FDE group (n = 108) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Pre-intervention | ||||

| Family activities | 19.29 ± 2.65 | 19.26 ± 2.49 | 0.092 | 0.927 |

| Emotional support | 10.61 ± 1.79 | 10.69 ± 1.75 | 0.357 | 0.721 |

| Economic status | 18.02 ± 2.11 | 18.11 ± 2.09 | 0.332 | 0.740 |

| Family member satisfaction | 10.37 ± 1.92 | 10.32 ± 1.89 | 0.199 | 0.842 |

| Post-intervention | ||||

| Family activities | 23.35 ± 2.37 | 24.01 ± 2.29 | 2.174 | 0.031 |

| Emotional support | 14.34 ± 1.99 | 14.85 ± 1.87 | 2.039 | 0.043 |

| Economic status | 18.87 ± 2.32 | 18.96 ± 2.14 | 0.293 | 0.770 |

| Family member satisfaction | 13.55 ± 1.23 | 13.92 ± 1.28 | 2.249 | 0.025 |

At baseline, no significant differences were observed between SCG and FDEG regarding caregiver emotional burden, time-dependent burden, developmental burden, and social burden (all P > 0.05, Table 5). After the intervention, the caregivers of FDEG exhibited significantly lower emotional burden (28.91 ± 2.61 vs 29.66 ± 2.45, P = 0.023), time-dependent burden (6.11 ± 0.56 vs 6.27 ± 0.54, P = 0.026), and developmental burden (5.99 ± 0.61 vs 6.16 ± 0.65, P = 0.044) than those of SCG. The social burden scores remained similar between the groups post-intervention (P = 0.654).

| Index | SC group (n = 127) | FDE group (n = 108) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Pre-intervention | ||||

| Emotional burden | 37.57 ± 3.01 | 37.74 ± 2.92 | 0.437 | 0.663 |

| Time-dependent burden | 6.73 ± 0.51 | 6.67 ± 0.54 | 0.986 | 0.325 |

| Developmental burden | 6.52 ± 0.56 | 6.57 ± 0.48 | 0.871 | 0.384 |

| Social burden | 6.41 ± 0.77 | 6.45 ± 0.63 | 0.378 | 0.706 |

| Pre-intervention | ||||

| Emotional burden | 29.66 ± 2.45 | 28.91 ± 2.61 | 2.288 | 0.023 |

| Time-dependent burden | 6.27 ± 0.54 | 6.11 ± 0.56 | 2.237 | 0.026 |

| Developmental burden | 6.16 ± 0.65 | 5.99 ± 0.61 | 2.025 | 0.044 |

| Social burden | 6.33 ± 0.64 | 6.29 ± 0.63 | 0.449 | 0.654 |

At baseline, no significant differences were noted in the sleep quality scores between SCG and FDEG for either patients or caregivers (all P > 0.05, Figure 1B). Following the intervention, the patients and caregivers in FDEG demonstrated significantly greater improvements in sleep quality than those in SCG, as reflected by lower post-intervention scores for patients (8.32 ± 2.21 vs 8.89 ± 2.16, P = 0.046) and caregivers (7.82 ± 1.43 vs 8.19 ± 1.31, P = 0.038).

At baseline, no significant differences were observed in the negative emotion scores between the two groups for either patients or caregivers, as measured by SAS and SDS (all P > 0.05, Table 6). Following the intervention, the patients and caregivers in FDEG exhibited significantly greater reductions in SAS and SDS scores than those in SCG. Specifically, the patients in FDEG had lower post-intervention SAS (40.88 ± 5.03 vs 42.63 ± 5.17, P = 0.009) and SDS scores (47.19 ± 5.27 vs 48.87 ± 5.31, P = 0.016). The caregivers of FDEG reported lower post-intervention SAS (43.83 ± 4.72 vs 45.19 ± 4.81, P = 0.030) and SDS scores (37.45 ± 4.26 vs 38.78 ± 4.15, P = 0.016) than those of SCG.

| Index | SC group (n = 127) | FDE group (n = 108) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Patient | ||||

| SAS before | 48.39 ± 5.75 | 48.36 ± 5.69 | 0.039 | 0.969 |

| SAS after | 42.63 ± 5.17 | 40.88 ± 5.03 | 2.626 | 0.009 |

| SDS before | 51.26 ± 5.53 | 51.28 ± 5.29 | 0.018 | 0.986 |

| SDS after | 48.87 ± 5.31 | 47.19 ± 5.27 | 2.423 | 0.016 |

| Caregiver | ||||

| SAS before | 52.42 ± 5.51 | 52.12 ± 5.42 | 0.425 | 0.671 |

| SAS after | 45.19 ± 4.81 | 43.83 ± 4.72 | 2.187 | 0.030 |

| SDS before | 41.15 ± 4.95 | 41.21 ± 4.98 | 0.098 | 0.922 |

| SDS after | 38.78 ± 4.15 | 37.45 ± 4.26 | 2.422 | 0.016 |

At baseline, no significant difference was observed in attitudes toward death between SCG and FDEG (42.19 ± 5.12 vs 42.26 ± 5.31, P = 0.921, Figure 1C). After the intervention, FDEG demonstrated significantly more positive attitudes toward death than SCG (52.45 ± 5.77 vs 50.04 ± 5.65, P = 0.001).

This study investigated the impact of postoperative “four-step death education” on QoL and negative emotions among patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their families. Contextualizing this intervention within broader developments in palliative care and psychosocial oncology is important to appreciate the significance and the latent mechanisms underlying the observed results.

Patients with cancer in advanced disease stages often grapple not only with debilitating physical symptoms but also profound existential distress, fear of suffering and death, anticipatory grief, and concerns for their loved ones’ future well-being[24]. In the absence of structured psychoeducational support, these burdens frequently translate into impaired QoL, increased anxiety and depression, and even complicated grieving after bereavement for families[25]. Despite advances in symptom control and palliative medicine, psychosocial dimensions remain inadequately addressed in many care settings, justifying the increasing recognition of death education as a component of comprehensive cancer care[26].

The rationale for the “four-step death education” model can be understood through several domains. First, the information provision step directly addresses existential uncertainty and loss of control, two central drivers of anxiety among patients with advanced cancer[27]. When facing life-limiting illness, patients and their families often experience information deficits or conflicting messages from different care providers, fueling uncertainty and distress[28]. By systematically educating participants about disease trajectory, potential complications, and available supports, the intervention fosters informed decision-making and enhanced sense of agency[29]. According to qualitative studies, such transparent communication is essential for patients to “make sense of death in their own way” and fosters acceptance, rather than avoidance, of the inevitable[30].

Second, the emotional support and structured group dialogue contribute to normalization and destigmatization of death-related conversations[31]. In many cultures, death is a taboo subject, with families engaging in mutual pretense or avoidance, which can isolate patients and caregivers and prevent meaningful closure[31]. Guided emotional support helps participants articulate and process fears, regrets, or unspoken worries, resulting in the reduction of death anxiety and improved psychological well-being[32]. Witnessing peers share similar experiences and feelings provides validation and a sense of universality, helping to reframe suffering as a shared human experience rather than a personal failing[29].

The life review and meaning exploration phase is rooted in existential psychology and meaning-centered therapy[33]. In the context of advanced cancer, patients frequently express a desire to reflect on their life narrative, resolve unfinished business, and find meaning even in the face of impending death[34]. Through guided reminiscence and meaning-making activities, individuals are encouraged to integrate their illness into the larger context of their lives, facilitating a sense of wholeness and inner peace[35]. Psychosocial research suggests that constructing “meaning bridges” between life lived and impending mortality can substantially reduce feelings of despair, helplessness, and demoralization, thereby alleviate depression and enhance QoL[35].

Preparation for end-of-life care, the final step, addresses practical and existential dimensions[36]. Advance care planning and exploration of personal values regarding end-of-life preferences are consistently associated with reduced stress and anxiety for patients and family members[36]. When patients have the opportunity to clarify their wishes, document their preferences, and appoint surrogates for decision-making, families experience lessened conflict and ambiguity during the dying process[37]. This not only improves perceived quality of care but also provides survivors with the reassurance that their loved one’s wishes were honored, thereby mitigating complicated grief and regret.

Beyond the patient, a pivotal effect of “four-step death education” emerged in family caregivers. The reduction in caregiver burden and improved sleep quality observed in the intervention group reflect, at least in part, the transference of existential coping skills and emotional literacy from patients to their families. Traditionally, caregivers in oncology settings report feelings of isolation, role overload, and anticipatory loss[38]. Incorporating caregivers into the death education process breaks the isolation, fosters collaborative coping, and provides caregivers with skills to manage patients’ needs and their own emotional health[39].

Specifically, interventions that support structured family communication and shared decision-making are associated with enhanced family functioning, improved problem-solving, and reductions in ambiguous loss and family conflict[40]. Final conversations, open expression of sentiments, and joint meaning-making activities during death education facilitate emotional closeness and mitigate the sense of unfinished business that can haunt patients and survivors[41]. Family-centered approaches not only alleviate psychological distress in the present moment but also possess enduring effects on the family system, strengthening cohesion and resilience in the face of bereavement[42].

The improvement in sleep quality witnessed among patients and caregivers can also be attributed to a reduction in rumination, anticipatory anxiety, and unresolved emotional turmoil. Psychoeducational interventions that normalize distress and teach adaptive coping strategies improve emotional regulation and diminish the intrusive thoughts that commonly disrupt sleep during advanced illness trajectories[33].

An important latent mechanism behind the observed reductions in anxiety and depression lies in the existential and relational security engendered by the intervention. When individuals feel well-informed, emotionally supported, and meaningfully engaged, their subjective sense of suffering decreases, even in the absence of major changes to physical symptoms. This phenomenon underscores the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of palliative care, which regards suffering as a multidimensional experience that transcends somatic symptoms[34]. According to contemporary models, interventions aimed at acceptance and meaning-making counteract the “total pain” of advanced cancer, encompassing physical, emotional, social, and spiritual domains[31].

A notable detail that consistent with a meaning-centered approach to palliative care, the attitudes toward death among patients in the intervention group became more positive, with greater openness and diminished fear. Earlier work has shown that structured death education and meaning-focused conversations can shift attitudes from avoidance or denial to acceptance and peace, even in highly adverse circumstances. This attitudinal shift correlates with greater willingness to engage in advance care planning, resolve family issues, and make legacy-focused decisions, all of which contribute to holistic QoL.

Although the study demonstrated the positive effects of “four-step death education” on the QoL and negative emotions of patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their families, its retrospective, single-center design limited the generalizability and external validity of the results. The retrospective design introduced selection and recall biases, and data from a single center may not represent broader populations. Retrospective studies often struggle to fully control for potential confounding factors, which also limited causal inference. Therefore, future multicenter randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the findings and further assess the intervention’s effectiveness and applicability. Additionally, this study only evaluated outcomes 3 months after the intervention, so the long-term benefits of “four-step death education” are unknown. The educational intervention was conducted once a week for 1 hour, lasting 3 months, for a total of 12 sessions. This frequency is feasible in the short term, but its long-term sustainability and adaptability to different cultural contexts require further exploration. Future research should extend follow-up times to assess the intervention’s long-term impact on QoL and emotional states. Although most improvements observed in this study were statistically significant, the effect sizes were relatively small, and significant changes were not seen in all assessed domains (e.g., pain, social functioning, and financial status). The clinical significance of these results requires further validation. All outcome measures were based on self-reports from patients or caregivers, which could have introduced self-reporting bias and potentially overstated the positive effects. No objective clinical measurements were included. Future research should further validate the clinical significance of these results by incorporating additional biomarkers and objective clinical measures.

Some broader societal and ethical implications arise from these findings. Cancer care systems that invest only in physical and pharmacological symptom management risk ignore the existential and emotional needs of patients and families. The present results support the integration of structured, multistep death education, rooted in information, emotional support, meaning exploration, and practical planning, into routine oncology and palliative care services. Implementation may require training for interdisciplinary teams and adaptation to cultural contexts because norms regarding death-related communication vary widely. However, the generalizability of the underlying mechanisms, restored agency, fostered connection, and cultivated acceptance seems robust across multiple cultural and diagnostic settings.

The mechanisms by which the postoperative “four-step death education” intervention enhanced QoL and reduced negative emotions in patients with advanced esophageal cancer and their families appear multifactorial. They span empowerment through knowledge, catharsis through emotional expression, healing through meaning construction, and relief through collaborative end-of-life planning. These pathways work synergistically to transform the experience of terminal illness from one of isolation and dread to one marked by agency, dignity, and relational closeness. Future research should further elucidate how to best tailor such interventions to individual preferences, family systems, and cultural values, thus maximizing their positive impact on the end-of-life journey.

| 1. | Wang H, Hao N, Liu N, Mou C, Li J, Meng L, Wu J. Impact of Collaborative Empowerment Education on Psychological Distress, Quality of Life, and Nutritional Status in Esophageal Cancer Patients Undergoing Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy. J Cancer Educ. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Degu A, Karimi PN, Opanga SA, Nyamu DG. Health-related quality of life among patients with esophageal, gastric, and colorectal cancer at Kenyatta National Hospital. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2024;7:e2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang G, Sun X, Li T, Xu M, Guo M, Liu C, Xie M. Study of the short-term quality of life of patients with esophageal cancer after inflatable videoassisted mediastinoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy. Front Surg. 2022;9:981576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nath VG, Govindaraj Raman S, M T, V C K, Micheal M, Earjala JK, A L, A AR, U A. Short-Term Outcomes and Quality of Life Following Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy in a Tertiary Care Center in Southern India. Cureus. 2023;15:e49245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Luo F, Lu Y, Chen C, Chang D, Jiang W, Yin R. Analysis of the Risk Factors for Negative Emotions in Patients with Esophageal Cancer During the Peri-Radiotherapy Period and Their Effects on Malnutrition. Int J Gen Med. 2023;16:6137-6150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang J, Zhou J, Chen S, Huang Y, Lin Z, Deng Y, Qiu M, Xiang Z, Hu Z. Association between dietary antioxidants, serum albumin/globulin ratio and quality of life in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients: a 7-year follow-up study. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1428214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Qiu LH, Liang SH, Wu L, Huang YY, Yang TZ, Li CZ, Huang XL, Zhong JD, Ma GW. Longitudinal assessment of quality of life indicators and prognosis in esophageal cancer patients with curative resection. J Thorac Dis. 2024;16:6064-6080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ferrari L, Sgaramella TM, Testoni I. Death education and educators: The role of attitudes, anxiety, and future time perspective. Death Stud. 2025;1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oates JR, Maani CV. Death and Dying(Archived). 2022 Nov 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Phan H, Ngu B, Hsu CS, Chen SC. The Life + Death Education Framework: Proposition of a 'Universal' Framework for Implementation. Omega (Westport). 2024;302228241295786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Romão ME, Belli G, Jumayeva S, Visonà SD, Woodthorpe K, Setti I, Barello S. Death Education in Practice: A Scoping Review of Interventions, Strategies, and Psychosocial Impact. Omega (Westport). 2025;302228251338643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang H, Lv T, Li L, Chen F, He S, Ding D. Nurse Life-and-Death Education From the Perspective of Chinese Traditional Culture. Omega (Westport). 2024;302228241236981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Veziant J, Bouché O, Aparicio T, Barret M, El Hajbi F, Lepilliez V, Lesueur P, Maingon P, Pannier D, Quero L, Raoul JL, Renaud F, Seitz JF, Serre AA, Vaillant E, Vermersch M, Voron T, Tougeron D, Piessen G; Thésaurus National de Cancérologie Digestive (TNCD) (Société Nationale Française de Gastroentérologie (SNFGE)); Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD); Groupe Coopérateur multidisciplinaire en Oncologie (GERCOR); Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (UNICANCER) Société Française de Chirurgie Digestive (SFCD); Société Française d'Endoscopie Digestive (SFED); Société Française de Radiothérapie Oncologique (SFRO); Société́ Française de Pathologie (SFP); Réseau National de Référence des Tumeurs Rares du Péritoine (RENAPE); Société Nationale Française de Colo-Proctologie (SNFCP); Société Française de Radiologie (SFR). Esophageal cancer - French intergroup clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatments and follow-up (TNCD, SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO, ACHBT, SFP, RENAPE, SNFCP, AFEF, SFR). Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:1583-1601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu BW, Yin T, Cao WX, Gu ZD, Wang XJ, Yan M, Liu BY. Clinical application of subjective global assessment in Chinese patients with gastrointestinal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3542-3549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gordan JD, Kennedy EB, Abou-Alfa GK, Beal E, Finn RS, Gade TP, Goff L, Gupta S, Guy J, Hoang HT, Iyer R, Jaiyesimi I, Jhawer M, Karippot A, Kaseb AO, Kelley RK, Kortmansky J, Leaf A, Remak WM, Sohal DPS, Taddei TH, Wilson Woods A, Yarchoan M, Rose MG. Systemic Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1830-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 82.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ratto C, Ricci R. Potential pitfalls concerning colorectal cancer classification in the seventh edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:e232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van der Wilk BJ, Eyck BM, Doukas M, Spaander MCW, Schoon EJ, Krishnadath KK, Oostenbrug LE, Lagarde SM, Wijnhoven BPL, Looijenga LHJ, Biermann K, van Lanschot JJB. Residual disease after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal cancer: locations undetected by endoscopic biopsies in the preSANO trial. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1791-1800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9802] [Cited by in RCA: 11950] [Article Influence: 362.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Samuel PS, Tarraf W, Marsack C. Family Quality of Life Survey (FQOLS-2006): Evaluation of Internal Consistency, Construct, and Criterion Validity for Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Families. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2018;38:46-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Loo YX, Yan S, Low LL. Caregiver burden and its prevalence, measurement scales, predictive factors and impact: a review with an Asian perspective. Singapore Med J. 2022;63:593-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17520] [Cited by in RCA: 23716] [Article Influence: 641.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2251] [Cited by in RCA: 2955] [Article Influence: 53.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5900] [Cited by in RCA: 6303] [Article Influence: 210.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ramos-Pla A, Arco ID, Espart A. Pedagogy of death within the framework of health education: The need and why teachers and students should be trained in primary education. Heliyon. 2023;9:e15050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Su FJ, Zhao HY, Wang TL, Zhang LJ, Shi GF, Li Y. Death education for undergraduate nursing students in the China Midwest region: An exploratory analysis. Nurs Open. 2023;10:7780-7787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhu Y, Bai Y, Wang A, Liu Y, Gao Q, Zeng Z. Effects of a death education based on narrative pedagogy in a palliative care course among Chinese nursing students. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1194460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ronconi L, Biancalani G, Medesi GA, Orkibi H, Testoni I. Death Education for Palliative Psychology: The Impact of a Death Education Course for Italian University Students. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023;13:182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Phan HP, Ngu BH, Hsu CS, Chen SC, Wu L. Expanding the scope of "trans-humanism": situating within the framework of life and death education - the importance of a "trans-mystical mindset". Front Psychol. 2024;15:1380665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Testoni I, Ronconi L, Orkibi H, Biancalani G, Raccichini M, Franchini L, Keisari S, Bucuta M, Cieplinski K, Wieser M, Varani S. Death education for Palliative care: a european project for University students. BMC Palliat Care. 2023;22:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang S, Yan C, Li J, Feng Y, Hu H, Li Y. The death education needs of patients with advanced cancer: a qualitative research. BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23:259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Testoni I. Death education: the importance of terror management theory and of the active methods. Evid Based Nurs. 2024;27:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jaffa MN, Kirschen MP, Tuppeny M, Reynolds AS, Lim-Hing K, Hargis M, Choi RK, Schober ME, LaBuzetta JN. Response to "Some Contributions on Standardized Education for Brain Death Determination". Neurocrit Care. 2023;39:742-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wang T, Cheung K, Cheng H. Death education interventions for people with advanced diseases and/or their family caregivers: A scoping review. Palliat Med. 2024;38:423-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jaffa MN, Kirschen MP, Tuppeny M, Reynolds AS, Lim-Hing K, Hargis M, Choi RK, Schober ME, LaBuzetta JN. Enhancing Understanding and Overcoming Barriers in Brain Death Determination Using Standardized Education: A Call to Action. Neurocrit Care. 2023;39:294-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Raccichini M, Biancalani G, Franchini L, Varani S, Ronconi L, Testoni I. Death education and photovoice at school: A workshop with Italian high school students. Death Stud. 2023;47:279-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yoong SQ, Wang W, Seah ACW, Kumar N, Gan JON, Schmidt LT, Lin Y, Zhang H. Nursing students' experiences with patient death and palliative and end-of-life care: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;69:103625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Phan HP, Chen SC, Ngu BH, Hsu CS. Advancing the study of life and death education: theoretical framework and research inquiries for further development. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1212223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lewis A. An Update on Brain Death/Death by Neurologic Criteria since the World Brain Death Project. Semin Neurol. 2024;44:236-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Foltz-Ramos K. Experiential Education About Patient Death Designed for Undergraduate Nursing Students. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2023;44:371-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Han H, Ye Y, Xie Y, Liu F, Wu L, Tang Y, Ding J, Yue L. The impact of death attitudes on death education needs among medical and nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2023;122:105738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Weisskirch RS, Crossman KA. The Impact of Death and Dying Education for Undergraduate Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Omega (Westport). 2024;89:998-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kurttekin F. Mothers' views on death education for children aged 4-6. Death Stud. 2024;48:948-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/