Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112103

Revised: September 16, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 159 Days and 2 Hours

Postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) after digestive tumors is a serious complication that severely affects patients’ prognosis; however, sys

To investigate the risk factors for postoperative ARDS in patients with digestive tumors and construct a prediction model.

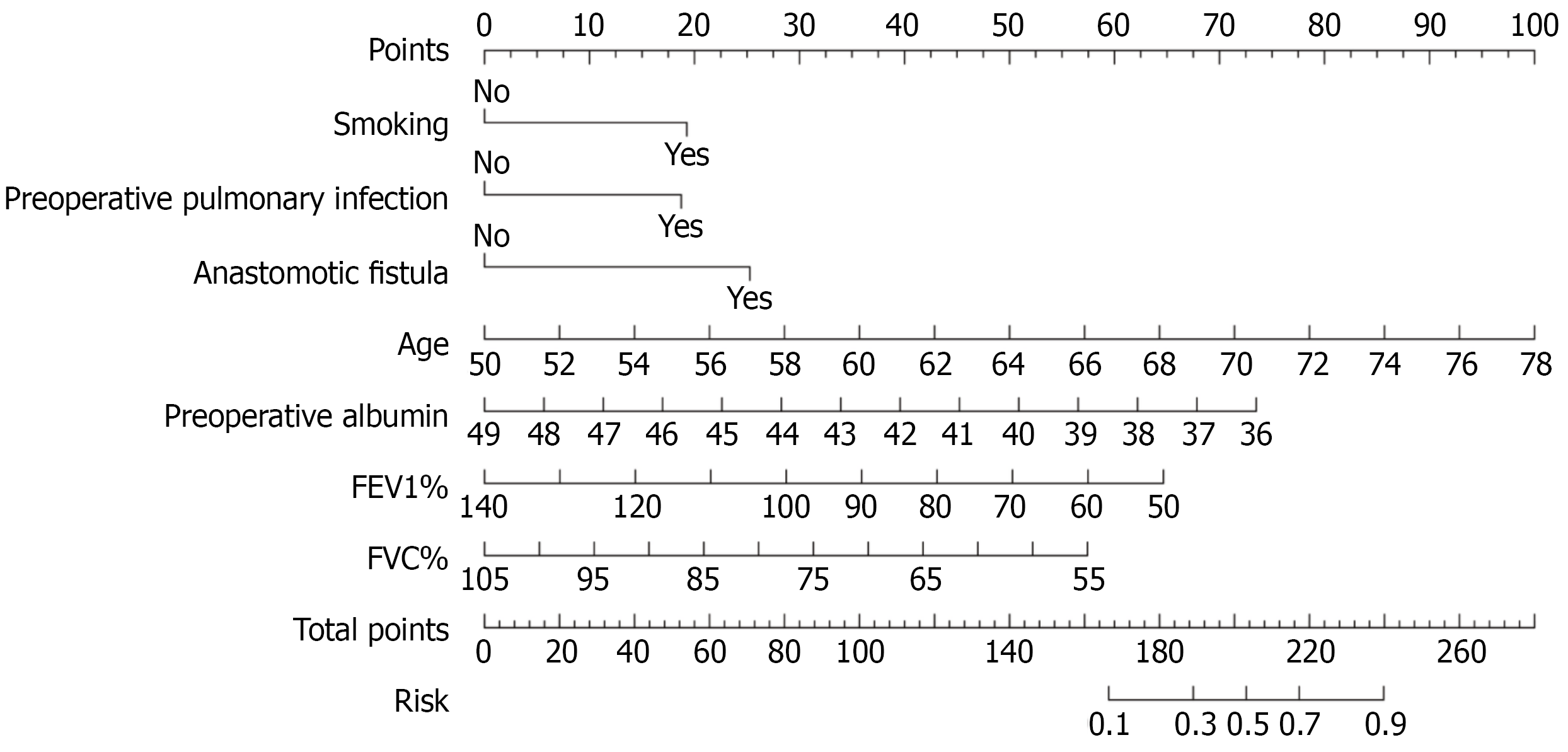

Overall, 42 of the 176 patients developed ARDS, with an incidence rate of 23.86%. Multifactorial logistic regression analysis identified advanced age [odds ratio (OR) = 1.24, P < 0.001], smoking history (OR = 3.17, P = 0.012), preoperative lung infection (OR = 3.07, P = 0.015), low preoperative albumin level (OR = 0.71, P = 0.003), preoperative percentage of forced expiratory volume in 1 second, (OR = 0.96, P = 0.006), preoperative percentage of forced vital capacity (OR = 0.94, P = 0.012), and postoperative anastomotic fistula (OR = 4.55, P = 0.022) as inde

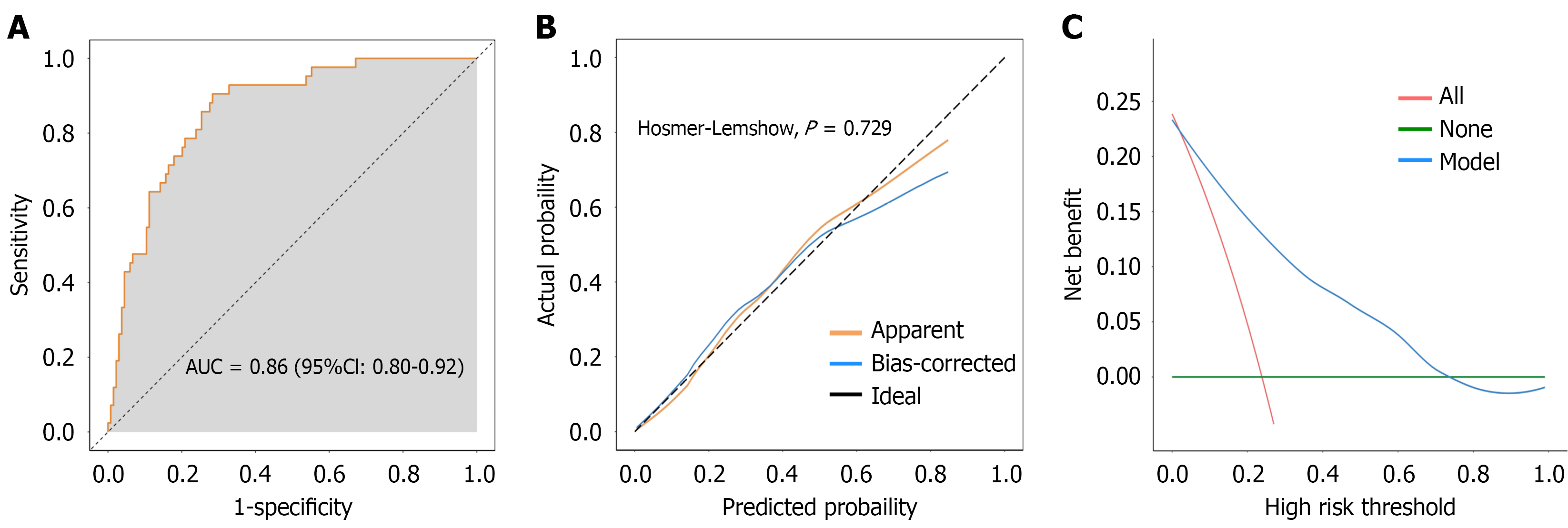

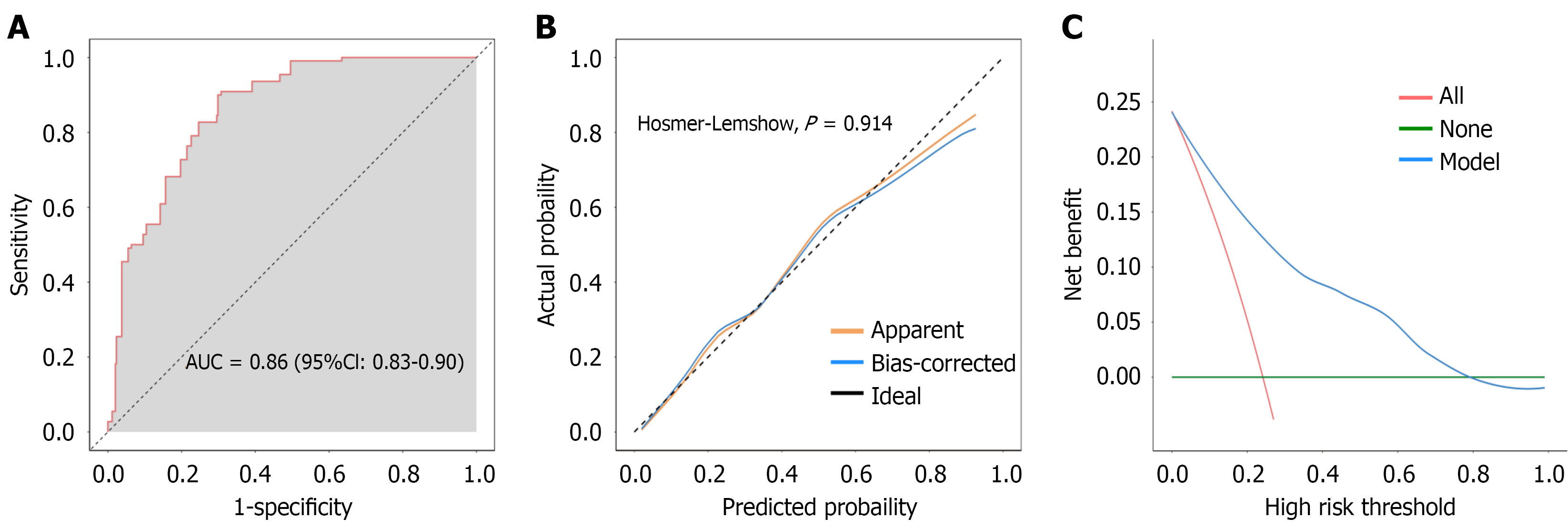

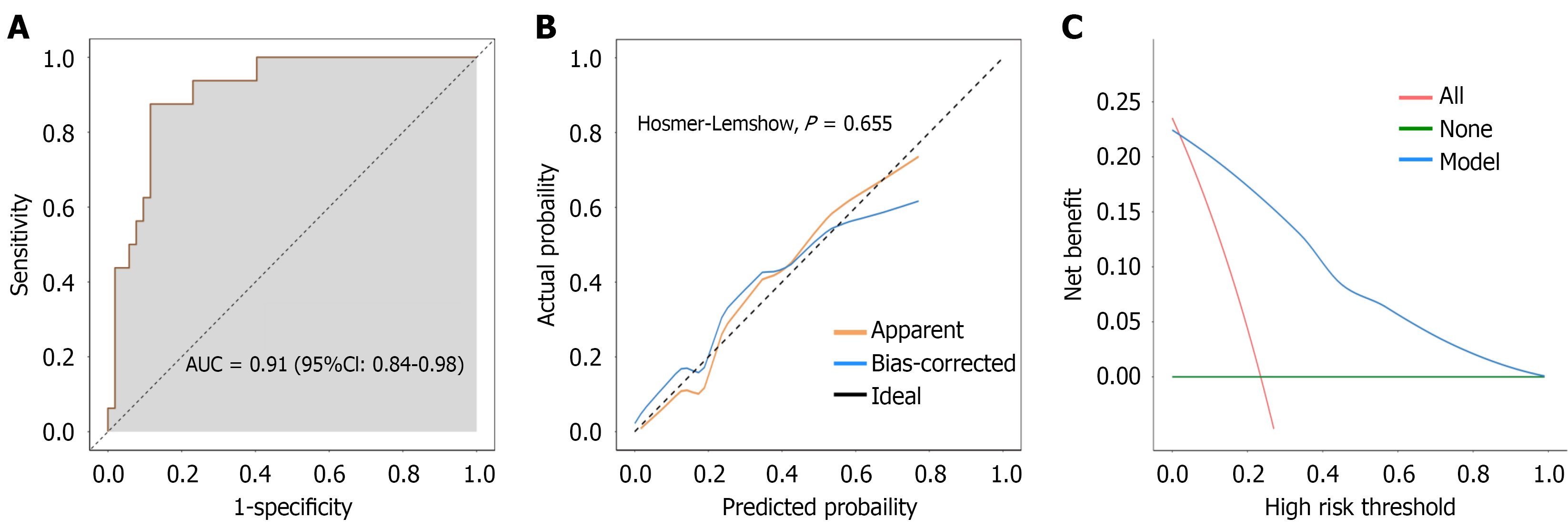

Overall, 42 of the 176 patients developed ARDS, with an incidence rate of 23.86%. Multifactorial logistic regression analysis identified advanced age (OR = 1.24, P < 0.001), smoking history (OR = 3.17, P = 0.012), preoperative lung infection (OR = 3.07, P = 0.015), low preoperative albumin level (OR = 0.71, P = 0.003), preoperative percentage of forced expiratory volume in 1 second, (OR = 0.96, P = 0.006), preoperative percentage of forced vital capacity (OR = 0.94, P = 0.012), and postoperative anastomotic fistula (OR = 4.55, P = 0.022) as independent risk factors for postoperative ARDS. The nomogram prediction model showed good discriminatory power (AUC = 0.86) and goodness of fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow, P = 0.729). The internal validation demonstrated an AUC of 0.86 and a good calibration curve fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow, P = 0.914). Prospective clinical validation confirmed the reliability and clinical value of the model (AUC = 0.91, accuracy = 82.35%).

The nomogram prediction model based on independent risk factors for postoperative ARDS in patients with digestive tumors demonstrated good differentiation, calibration, and clinical utility and helped identify high-risk patients early.

Core Tip: This study identified advanced age, smoking history, preoperative pulmonary infection, hypoalbuminemia, impaired pulmonary function, and anastomotic leakage as key risk factors for postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with digestive tumors. A novel nomogram prediction model based on these factors demonstrated excellent discriminative ability (area under the curve = 0.86-0.91) in identifying high-risk patients. These findings emphasize the importance of preoperative optimization (e.g., smoking cessation, infection control, and nutritional support) and postoperative vigilance, particularly in patients with poor pulmonary reserve. This practical tool enables individualized risk assessment and early intervention to reduce acute respiratory distress syndrome incidence and improve surgical outcomes.

- Citation: Zhen J, Chen W, Xu YF, Ma YM. Risk factors and prediction model for acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with digestive tumor after surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 112103

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/112103.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112103

Digestive system tumors are among the most common malignant tumors worldwide, with high incidence and mortality rates[1,2]. This may be attributed to the increasing incidence of digestive tumors in recent years, driven by population aging and lifestyle changes[3]. Despite advances in medical technology, surgical resection remains the mainstay treatment for digestive tumors, specifically in patients with early- to mid-stage disease, with radical surgery significantly improving survival rates[4,5]. However, the occurrence of postoperative complications affects the patient’s short-term recovery, increases the long-term risk of mortality, and may even offset the benefits of surgical treatment[6]. The overall incidence of postoperative complications in patients with digestive tumors ranges from 20% to 50%, resulting in prolonged hospitalization and increased medical costs, and may even be life-threatening in serious cases[7,8]. Therefore, an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms and risk factors of postoperative complications in digestive tumors is necessary to improve postoperative regression.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a common and serious postoperative complication in patients with digestive tumors[9]. ARDS is a clinical syndrome characterized by acute progressive dyspnea, persistent hypoxemia, and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema[10]. The mechanisms underlying the postoperative complications of ARDS are complex and may be associated with various factors, such as systemic inflammatory response syndrome caused by surgical trauma, lung infection, pulmonary vascular endothelial cell injury, and poor postoperative fluid management[11]. During surgical procedures, tissue damage and the release of inflammatory factors can activate the immune system[12]. This activation may trigger a systemic inflammatory response, subsequently affecting pulmonary microcirculation and alveolar epithelial cells[13]. Moreover, these events may cause pulmonary edema and alveolar atrophy, ultimately leading to the development of ARDS. In addition, postoperative patients are often susceptible to lung infections because of immune suppression and increased airway secretions, which further aggravate lung injury[14]. Collectively, ARDS development jeopardizes the postoperative recovery in patients with digestive tumors and substantially increase their risk of mortality, thereby imposing a heavy burden on healthcare systems. Consequently, the precise identification of high-risk factors for postoperative ARDS in this patient population is of great clinical significance, as it enables timely early intervention to reduce both the incidence and mortality of ARDS.

As an intuitive and visual predictive tool, nomogram models have been widely used to identify risk factors and predict prognosis for various diseases[15]. A nomogram model can facilitate individualized risk assessment by integrating multiple independent risk factors and help develop more precise treatment strategies. However, studies on predictive models for postoperative complications of ARDS in patients with digestive tumors are currently lacking. Therefore, this study aimed to retrospectively analyze the clinical data of postoperative patients with digestive tumors, screen independent risk factors for postoperative complications of ARDS, and construct a prediction model based on the nomogram. Our results will provide insights into the risk factors of ARDS, further enhancing our understanding of the mechanism of postoperative ARDS in digestive tumors. Additionally, this study may serve as a reference for clinicians to formulate individualized postoperative management plans to reduce ARDS incidence, lower morbidity and mortality rates, and improve patient prognosis.

This retrospective study included 176 patients who underwent surgical treatment for digestive tumors at Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University between January 2022 and January 2024. All patients had a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of malignancy and underwent elective or limited radical tumor surgery. Additionally, we collected data from 68 patients between February 2024 and October 2024 to clinically validate the prediction model. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University.

The inclusion criteria: (1) Aged ≥ 18 years; (2) Pathologically confirmed diagnosis of gastrointestinal malignancy (gastric, colorectal, esophageal, etc.); (3) First-time surgical treatment for gastrointestinal tumors; and (4) Patients with complete clinical data.

The exclusion criteria: (1) Combination of other malignancies; (2) Preoperative presence of severe cardiopulmonary insufficiency or diagnosed ARDS; (3) Preoperative emergency surgery, palliative surgery, or neoadjuvant radiotherapy; and (4) Postoperative respiratory failure because of non-respiratory causes (e.g., postoperative hemorrhage, abdominal infections).

Data on basic patient information, preoperative indicators, surgery-related information, and postoperative conditions were collected from the electronic medical record system of the hospital. The preoperative indices included tumor site, tumor-node-metastasis stage, preoperative lung infection, preoperative red blood cell count, preoperative white blood cell (WBC) count, preoperative albumin (ALB), preoperative hemoglobin, preoperative platelets, preoperative percentage of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1%), and preoperative percentage of forced vital capacity (FVC%). Surgery-related information included surgery type and duration, amount of intraoperative bleeding, and amount of intraoperative rehydration. The postoperative conditions assessed were postoperative infection, fever, and anastomotic fistulas.

ARDS was diagnosed based on the criteria defined by Berlin[16] as follows: (1) The patient must present with an acute onset of illness within 2 weeks after a known clinical trigger or an exacerbation of new respiratory symptoms; (2) The oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2) should meet a specific threshold under different conditions of respiratory support, as follows: In mild ARDS, 200 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg for a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)/continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ≥ 5 cmH2O; in moderate ARDS, 100 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg; in moderate ARDS, 100 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg at PEEP/CPAP ≥ 5 cmH2O; and in severe ARDS, PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 100 mmHg at PEEP/CPAP ≥ 5 cmH2O; and (3) Chest imaging (e.g., chest radiographs, computed tomography, or lung ultrasound) should indicate decreased transmittance in both lungs. Reduced transmittance refers to attenuation that cannot be fully explained by pleural effusion, lobar atelectasis, or nodules. Similarly, respiratory failure is defined as a condition not explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload and pulmonary edema with elevated hydrostatic pressure but can be ruled out by objective assessment (e.g., cardiac ultrasonography) in the absence of clear risk factors. Postoperative ARDS was diagnosed jointly by at least two clinicians.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0. The dataset was complete for all variables included in the analysis, with no missing values; therefore, no specific imputation methods were required. Measurement information is expressed as mean ± SD and was compared between groups using the independent samples t-test. Count data are expressed as number of cases (percentage), n (%) and were compared between groups using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact probability method (when theoretical frequencies were < 5). Risk factors associated with postoperative ARDS were initially screened using univariate logistic regression analysis with P < 0.05. Variables that were statistically significant in univariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression model to identify independent risk factors for postoperative ARDS, and odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. A nomogram prediction model was constructed based on the results of the multifactorial logistic regression analysis, and its performance was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic curve, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), calibration curve, and clinical decision curve. The closer the AUC value is to 1, the stronger the discriminative ability of the model. The calibration curve was used to assess the consistency between the predicted and observed values of the model. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (P > 0.05) was used to assess the model’s fit, whereas the clinical decision curve was used to assess the clinical utility of the model under different risk thresholds. Additionally, the model was internally validated using the bootstrap method with 500 random samples, and AUC, calibration curves, and clinical decision curves were calculated to assess the stability and reliability of the model. Finally, the model was clinically validated using prospectively collected data from 68 patients. The AUC, calibration curve, clinical decision curve, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the model were calculated to further validate its clinical application value.

This study included 176 patients who underwent surgery for digestive tumors. Of these, 42 patients developed ARDS, with an incidence rate of 23.86% (Table 1). The mean age of the ARDS group was significantly higher than that of the non-ARDS group (66.36 vs 63.74, respectively) (P = 0.003). The proportions of patients with a history of smoking, stage III/IV disease, preoperative pulmonary infection, and postoperative anastomotic fistulas in the ARDS group were significantly higher than those in the non-ARDS group (P < 0.05). In addition, the preoperative WBC count was higher in the ARDS group, whereas preoperative ALB, FEV1%, and FVC% were lower compared to those in the non-ARDS group (P < 0.05).

| Variables | Total (n = 176) | Non-ARDS group (n = 134) | ARDS group (n = 42) | Statistic | P value |

| Age, mean ± SD | 64.36 ± 5.07 | 63.74 ± 4.86 | 66.36 ± 5.28 | t = -2.99 | 0.003 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 22.92 ± 3.29 | 22.98 ± 3.35 | 22.73 ± 3.12 | t = 0.43 | 0.669 |

| Preoperative RBC, mean ± SD | 3.62 ± 0.65 | 3.58 ± 0.61 | 3.75 ± 0.79 | t = -1.21 | 0.230 |

| Preoperative WBC, mean ± SD | 5.80 ± 0.97 | 5.71 ± 0.89 | 6.08 ± 1.14 | t = -2.12 | 0.035 |

| Preoperative ALB, mean ± SD | 42.14 ± 2.52 | 42.41 ± 2.53 | 41.27 ± 2.34 | t = 2.62 | 0.010 |

| Preoperative Hb, mean ± SD | 130.20 ± 9.66 | 130.72 ± 9.69 | 128.57 ± 9.47 | t = 1.26 | 0.211 |

| Preoperative PLT, mean ± SD | 191.44 ± 25.80 | 189.47 ± 24.55 | 197.72 ± 28.86 | t = -1.82 | 0.071 |

| FEV1%, mean ± SD | 88.13 ± 15.32 | 90.17 ± 15.62 | 81.64 ± 12.37 | t = 3.23 | 0.001 |

| FVC%, mean ± SD | 78.11 ± 9.67 | 79.24 ± 9.75 | 74.47 ± 8.54 | t = 2.84 | 0.005 |

| Operation time, mean ± SD | 182.83 ± 23.05 | 181.36 ± 22.51 | 187.52 ± 24.37 | t = -1.52 | 0.131 |

| Preoperative bleeding, mean ± SD | 51.68 ± 12.40 | 51.19 ± 11.74 | 53.24 ± 14.33 | t = -0.94 | 0.351 |

| Sex | χ2 = 0.08 | 0.784 | |||

| Female | 66 (37.50) | 51 (38.06) | 15 (35.71) | ||

| Male | 110 (62.50) | 83 (61.94) | 27 (64.29) | ||

| Smoking | χ2 = 4.81 | 0.028 | |||

| No | 93 (52.84) | 77 (57.46) | 16 (38.10) | ||

| Yes | 83 (47.16) | 57 (42.54) | 26 (61.90) | ||

| Hypertension | χ2 = 0.67 | 0.414 | |||

| No | 114 (64.77) | 89 (66.42) | 25 (59.52) | ||

| Yes | 62 (35.23) | 45 (33.58) | 17 (40.48) | ||

| Diabetes | χ2 = 0.89 | 0.345 | |||

| No | 163 (92.61) | 126 (94.03) | 37 (88.10) | ||

| Yes | 13 (7.39) | 8 (5.97) | 5 (11.90) | ||

| Tumor location | χ2 = 4.24 | 0.236 | |||

| Intestine | 86 (48.86) | 71 (52.99) | 15 (35.71) | ||

| Stomach | 34 (19.32) | 25 (18.66) | 9 (21.43) | ||

| Liver and gallbladder | 30 (17.05) | 20 (14.93) | 10 (23.81) | ||

| Pancreas | 26 (14.77) | 18 (13.43) | 8 (19.05) | ||

| TNM staging | χ2 = 5.58 | 0.018 | |||

| I/II | 99 (56.25) | 82 (61.19) | 17 (40.48) | ||

| III/IV | 77 (43.75) | 52 (38.81) | 25 (59.52) | ||

| Preoperative pulmonary infection | χ2 = 5.16 | 0.023 | |||

| No | 125 (71.02) | 101 (75.37) | 24 (57.14) | ||

| Yes | 51 (28.98) | 33 (24.63) | 18 (42.86) | ||

| Surgical method | χ2 = 1.70 | 0.192 | |||

| Laparoscopic surgery | 127 (72.16) | 100 (74.63) | 27 (64.29) | ||

| Open surgery | 49 (27.84) | 34 (25.37) | 15 (35.71) | ||

| Intraoperative fluid replacement | χ2 = 0.33 | 0.566 | |||

| < 2000 mL | 78 (44.32) | 61 (45.52) | 17 (40.48) | ||

| ≥ 2000 mL | 98 (55.68) | 73 (54.48) | 25 (59.52) | ||

| Postoperative infection | χ2 = 0.69 | 0.406 | |||

| No | 138 (78.41) | 107 (79.85) | 31 (73.81) | ||

| Yes | 38 (21.59) | 27 (20.15) | 11 (26.19) | ||

| Postoperative fever | χ2 = 1.43 | 0.233 | |||

| No | 122 (69.32) | 96 (71.64) | 26 (61.90) | ||

| Yes | 54 (30.68) | 38 (28.36) | 16 (38.10) | ||

| Anastomotic fistula | χ2 = 9.71 | 0.002 | |||

| No | 161 (91.48) | 128 (95.52) | 33 (78.57) | ||

| Yes | 15 (8.52) | 6 (4.48) | 9 (21.43) | ||

The univariate logistic regression analysis identified advanced age (OR = 1.12, P = 0.004), smoking (OR = 2.20, P = 0.030), tumor-node-metastasis stage III/IV (OR = 2.32, P = 0.020), preoperative lung infection (OR = 2.30, P = 0.025), elevated preoperative WBC (OR = 1.51, P = 0.038), decreased preoperative ALB (OR = 0.83, P = 0.011), lower preoperative FEV1% (OR = 0.96, P = 0.002) and FVC% (OR = 0.95, P = 0.006), and the presence of anastomotic fistula (OR = 5.82, P = 0.002) in the postoperative period as the risk factors for postoperative development of ARDS in patients with digestive tumors (Table 2).

| Variables | β | SE | Z | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Age | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.85 | 0.004 | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) |

| BMI | -0.02 | 0.05 | -0.43 | 0.667 | 0.98 (0.88-1.09) |

| Preoperative RBC | 0.38 | 0.27 | 1.38 | 0.167 | 1.46 (0.85-2.48) |

| Preoperative WBC | 0.41 | 0.20 | 2.08 | 0.038 | 1.51 (1.02-2.23) |

| Preoperative ALB | -0.19 | 0.07 | -2.53 | 0.011 | 0.83 (0.72-0.96) |

| Preoperative Hb | -0.02 | 0.02 | -1.25 | 0.211 | 0.98 (0.94-1.01) |

| Preoperative PLT | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.79 | 0.073 | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) |

| FEV1% | -0.04 | 0.01 | -3.08 | 0.002 | 0.96 (0.94-0.99) |

| FVC% | -0.05 | 0.02 | -2.73 | 0.006 | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) |

| Operation time | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.51 | 0.132 | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) |

| Preoperative bleeding | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.349 | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Male | 0.10 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.784 | 1.11 (0.54-2.27) |

| Smoking | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.79 | 0.36 | 2.17 | 0.030 | 2.20 (1.08-4.47) |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.415 | 1.34 (0.66-2.74) |

| Diabetes | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.76 | 0.60 | 1.26 | 0.208 | 2.13 (0.66-6.90) |

| Tumor location | |||||

| Intestine | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Stomach | 0.53 | 0.48 | 1.11 | 0.268 | 1.70 (0.66-4.38) |

| Liver and gallbladder | 0.86 | 0.48 | 1.79 | 0.073 | 2.37 (0.92-6.07) |

| Pancreas | 0.74 | 0.51 | 1.45 | 0.146 | 2.10 (0.77-5.73) |

| TNM staging | |||||

| I/II | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| III/IV | 0.84 | 0.36 | 2.33 | 0.020 | 2.32 (1.14-4.70) |

| Preoperative pulmonary infection | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.83 | 0.37 | 2.24 | 0.025 | 2.30 (1.11-4.75) |

| Surgical method | |||||

| Laparoscopic surgery | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Open surgery | 0.49 | 0.38 | 1.30 | 0.194 | 1.63 (0.78-3.43) |

| Intraoperative fluid replacement | |||||

| < 2000 mL | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| ≥ 2000 mL | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.566 | 1.23 (0.61-2.48) |

| Postoperative infection | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.83 | 0.408 | 1.41 (0.63-3.15) |

| Postoperative fever | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.44 | 0.37 | 1.19 | 0.234 | 1.55 (0.75-3.22) |

| Anastomotic fistula | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.76 | 0.56 | 3.13 | 0.002 | 5.82 (1.93-17.51) |

The variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model to explore the independent risk factors of ARDS. The results showed that advanced age (OR = 1.24, P < 0.001), smoking (OR = 3.17, P = 0.012), preoperative pulmonary infection (OR = 3.07, P = 0.015), decreased preoperative ALB (OR = 0.71, P = 0.003), lower preoperative FEV1% (OR = 0.96, P = 0.006) and FVC% (OR = 0.94, P = 0.012), and postoperative anastomotic fistula (OR = 4.55, P = 0.022) were independent risk factors for ARDS in patients with digestive tumors after surgery (Table 3).

| Variables | β | SE | Z | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Intercept | 6.33 | 4.67 | 1.35 | 0.176 | 559.39 (0.06-5308961.64) |

| Smoking | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.15 | 0.46 | 2.50 | 0.012 | 3.17 (1.28-7.84) |

| Preoperative pulmonary infection | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.12 | 0.46 | 2.43 | 0.015 | 3.07 (1.24-7.61) |

| Anastomotic fistula | |||||

| No | - | - | - | - | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.51 | 0.66 | 2.29 | 0.022 | 4.55 (1.24-16.67) |

| Age | 0.21 | 0.06 | 3.80 | < 0.001 | 1.24 (1.11-1.38) |

| Preoperative ALB | -0.34 | 0.11 | -2.98 | 0.003 | 0.71 (0.57-0.89) |

| FEV1% | -0.04 | 0.02 | -2.77 | 0.006 | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) |

| FVC% | -0.06 | 0.02 | -2.50 | 0.012 | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) |

The log-odds (logit) of postoperative ARDS was calculated using the following logistic regression equation: Logit (P) = 6.33 + 0.21 × age (years) + 1.15 × smoking (1 = yes, 0 = no) + 1.12 × preoperative pulmonary infection (1 = yes, 0 = no)

The AUC of the nomogram prediction model was 0.86, indicating that the model had good discriminatory ability for ARDS (Figure 2A). The calibration curve indicated no significant difference between the observed and predicted values of the model, and the model demonstrated a good degree of fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow, P = 0.729) (Figure 2B). Additionally, the clinical decision curve indicated that the model had positive net benefits when the risk probability was 0.05-0.70 (Figure 2C).

The bootstrap method was used to randomly sample the original model 500 times for internal verification. The results showed an AUC of 0.86 under the internal validation cohort, indicating good discrimination (Figure 3A). The calibration curve indicated a good model fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow, P = 0.914) (Figure 3B). The clinical decision curve indicated that the model could provide good clinical benefit when the risk probability was between 0.05 and 0.80 (Figure 3C).

The nomogram prediction model was validated using prospectively collected data from 68 patients after digestive tumor surgery. The model demonstrated an AUC of 0.91, reflecting good discriminatory power (Figure 4A). Additionally, the calibration curve indicated a good fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow, P = 0.655) (Figure 4B), whereas the clinical decision curve indicated good clinical value of the model when the risk probability was 0.05-1.00 (Figure 4C). The model demonstrated postoperative ARDS development in 16 of the 68 patients analyzed. The accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the nomogram prediction model were 82.35%, 50.00%, and 92.31%, respectively (Table 4).

| Prediction result | Gold standard | Total | |

| ARDS | Non-ARDS | ||

| ARDS | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Non-ARDS | 8 | 48 | 56 |

| Total | 16 | 52 | 68 |

ARDS is a common and serious postoperative complication in patients with digestive tumors, with high morbidity and mortality rates and significantly affecting postoperative recovery and long-term prognosis[17]. Therefore, this study screened independent risk factors for the occurrence of postoperative ARDS and constructed a prediction model based on a nomogram to provide clinicians with a reference basis for individualized postoperative management protocols. Of the 176 postoperative patients with gastrointestinal tumors included in this study, 42 developed ARDS, with an incidence rate of 23.86%. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses identified advanced age, smoking, preoperative lung infection, preoperative decrease in ALB, preoperative decreases in FEV1% and FVC%, and postoperative ana

In this study, advanced age was an independent risk factor for postoperative ARDS, consistent with the findings of previous studies. Specifically, Xu et al[18] reported postoperative ARDS in 113 of the 532 patients who underwent abdominal surgery and identified advanced age as an independent risk factor. This may be attributable to decreased organ reserve function and weakened immune surveillance in older patients[19]. The regenerative capacity of alveolar type II epithelial cells and lung compliance decreases with age, leading to postoperative alveolar atrophy and atelectasis[20]. Simultaneously, the chronic inflammatory state associated with aging (inflammaging) predisposes the body to an exaggerated inflammatory response to surgical trauma, manifesting as the excessive release of pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α), which exacerbate endothelial damage and increase the permeability of the pulmonary vasculature[21]. In addition, older patients often have diverse underlying diseases that can further weaken their cardiopulmonary compensatory capacity, resulting in a vicious cycle of postoperative respiratory insufficiency. Consequently, the specific mechanisms involved must be verified through further experimental studies.

Our findings also revealed that a history of smoking increases the risk of postoperative ARDS by 3.17 times, confirming the cumulative damage caused by tobacco exposure to the respiratory system. Nicotine, tar, and other tobacco com

We also observed a significantly high risk of postoperative ARDS in patients with preoperative lung infection. During ARDS progression, numerous inflammatory mediators accumulate in the lung interstitium, a process closely linked to the pathological cascade induced by preoperative lung infection[27]. Specifically, pre-existing lung infection primes the immune system, resulting in neutrophil infiltration and the release of bacterial toxins and pro-inflammatory mediators that infiltrate the alveolar and interstitial spaces[27]. This pro-inflammatory milieu facilitates the exacerbation of the systemic inflammatory response following subsequent surgical trauma and predisposes patients to diffuse alveolar damage, a hallmark of ARDS[28]. Furthermore, the significant association between decreased preoperative ALB levels and increased risk of postoperative ARDS reflects the multiple damages to the lungs due to malnutrition. Notably, ALB is an important component for maintaining plasma colloid osmolality. Therefore, a decrease in ALB levels reduces plasma colloid osmolality, which increases pulmonary capillary permeability and promotes the development of pulmonary edema[29]. In addition, ALB has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects; therefore, low ALB levels may weaken the body’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory abilities and exacerbate postoperative inflammatory responses[30]. Hence, preoperative hypoalbuminemia should be actively corrected, and the ALB levels should be increased through nutritional support or ALB infusion to reduce the risk of postoperative ARDS.

In this study, decreases in FEV1% and FVC% were also significantly associated with an increased risk of ARDS, suggesting that obstructive or restrictive ventilatory dysfunction is an important warning sign of postoperative respiratory failure. FEV1% reflects airway patency. Consequently, a decrease in FEV1% is common in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, who are prone to pulmonary atelectasis and infections because of the retention of airway secretions[31]. In contrast, a decrease in FVC% suggests reduced lung parenchyma or thoracic elasticity, leading to impaired ventilation and a diminished ability to compensate for the increased respiratory demand due to surgery[32]. Therefore, preoperative pulmonary function assessment should be conducted routinely for patients undergoing gas

The nomogram prediction model constructed in this study enabled quantitative prediction of individual postoperative ARDS risk by integrating seven independent risk factors. The AUCs of the model for the training, internal validation, and external validation sets indicated stable discriminative ability. Additionally, calibration curves showed that the predicted values were in good agreement with the actual values, suggesting that the model could accurately estimate the probability of disease onset at different risk intervals. Moreover, clinical decision curves showed that the net benefit of the model was significantly better than that of the “all-treatment” or “all-no-treatment” strategies when the risk threshold was ≥ 5%, specifically between 10% and 70%, reflecting its suitability for routine clinical risk screening. Notably, compared to the models in previous studies, an advantage of our model is the inclusion of key variables such as preoperative lung function indicators and postoperative anastomotic fistulas, which improves the comprehensiveness and accuracy of prediction. In addition, the bootstrap internal validation and prospective external validation confirmed the stability and generalizability of the model, making it highly valuable for clinical applications. Therefore, in the future, the model parameters can be further optimized through multi-center large-sample studies, and its integration into electronic medical record systems can be explored for real-time risk warning. For improved clinical application, we recommend developing an online calculator (e.g., based on web or mobile platforms) and a simplified scoring system that assigns weighted scores to each risk factor to facilitate rapid risk assessment. Meanwhile, risk stratification using the model can guide management: Patients with predicted ARDS risk < 10% (low-risk) may undergo routine postoperative care, those with 10%-70% risk (medium-risk) should undergo enhanced respiratory monitoring (e.g., daily SpO2 and chest auscultation), and those with > 70% risk (high-risk) should receive proactive interventions (e.g., preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation, optimized fluid management) to reduce ARDS incidence.

This study also had some limitations. First, the single-center design and relatively modest sample size (n = 176) may limit the generalizability of our findings and introduce potential selection bias, as the patient population and surgical practices at our institution may not be fully representative. Therefore, future large-scale, multi-center prospective studies are essential to validate and reinforce our results across more diverse populations and clinical settings. Second, the number of variables included in this study was limited, and other potential risk factors may have been missed. Therefore, the research horizon should be broadened to include more relevant variables to construct a more comprehensive and accurate prediction model. Finally, the prediction model constructed in this study has not been widely adopted in clinical practice, and its validity and reliability require further verification. Hence, closer collaboration with clinicians is necessary to facilitate its implementation in actual clinical practice, alongside continuous optimization and improvement based on feedback.

In this study, we identified advanced age, smoking history, preoperative lung infection, low preoperative ALB levels, low preoperative pulmonary function indices (FEV1% and FVC%), and postoperative anastomotic fistula as independent risk factors for postoperative ARDS in patients with digestive system tumors. Subsequently, the nomogram prediction model constructed based on these factors demonstrated good discriminatory ability and calibration and can provide an individualized risk assessment tool for clinical use. Clinical decision curve analysis of the model also demonstrated a significant net benefit for clinical decision-making within the risk threshold range of 5% to 80%, identifying high-risk patients early and optimizing postoperative management strategies. The stability and generalizability of the model were further confirmed through bootstrap internal validation and prospective external validation, providing a reliable basis for its application in clinical practice.

The findings of this study emphasize the importance of preoperative assessment and postoperative management. By identifying high-risk patients, clinicians can take targeted preventive measures such as optimizing preoperative pulmonary function training, controlling underlying diseases, aggressive anti-infective treatment, and correcting hypoalbuminemia to reduce the risk of postoperative ARDS. In addition, the nomogram prediction model constructed in this study provides clinicians with an intuitive and visual tool that helps individualize the assessment of the risk of postoperative ARDS and formulate more precise postoperative management strategies.

| 1. | Zhou Y, Song K, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Dai M, Wu D, Chen H. Burden of six major types of digestive system cancers globally and in China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2024;137:1957-1964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Thrift AP, Wenker TN, El-Serag HB. Global burden of gastric cancer: epidemiological trends, risk factors, screening and prevention. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:338-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Yu Z, Bai X, Zhou R, Ruan G, Guo M, Han W, Jiang S, Yang H. Differences in the incidence and mortality of digestive cancer between Global Cancer Observatory 2020 and Global Burden of Disease 2019. Int J Cancer. 2024;154:615-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang Y, Zhang L, Yang Y, Lu S, Chen H. Progress of Gastric Cancer Surgery in the era of Precision Medicine. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17:1041-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gahunia S, Wyatt J, Powell SG, Mahdi S, Ahmed S, Altaf K. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in high-risk patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2025;29:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ravenel M, Joliat GR, Demartines N, Uldry E, Melloul E, Labgaa I. Machine learning to predict postoperative complications after digestive surgery: a scoping review. Br J Surg. 2023;110:1646-1649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee SY, Lee J, Park HM, Kim CH, Kim HR. Impact of Preoperative Immunonutrition on the Outcomes of Colon Cancer Surgery: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2023;277:381-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Kooten RT, Elske van den Akker-Marle M, Putter H, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, van de Velde CJH, Wouters MWJM, Tollenaar RAEM, Peeters KCMJ. The Impact of Postoperative Complications on Short- and Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life After Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2022;21:325-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Douville NJ, Smolkin ME, Naik BI, Mathis MR, Colquhoun DA, Kheterpal S, Collins SR, Martin LW, Popescu WM, Pace NL, Blank RS; Multicentre Perioperative Clinical Research Committee. Association between inspired oxygen fraction and development of postoperative pulmonary complications in thoracic surgery: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2024;133:1073-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bos LDJ, Ware LB. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: causes, pathophysiology, and phenotypes. Lancet. 2022;400:1145-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 562] [Article Influence: 140.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zheng F, Pan Y, Yang Y, Zeng C, Fang X, Shu Q, Chen Q. Novel biomarkers for acute respiratory distress syndrome: genetics, epigenetics and transcriptomics. Biomark Med. 2022;16:217-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhaojun X, Xiaobin C, Juan A, Jiaqi Y, Shuyun J, Tao L, Baojia C, Cheng W, Xiaoming M. Correlation analysis between preoperative systemic immune inflammation index and prognosis of patients after radical gastric cancer surgery: based on propensity score matching method. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hancox RJ, Gray AR, Sears MR, Poulton R. Systemic inflammation and lung function: A longitudinal analysis. Respir Med. 2016;111:54-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xiao H, Zhou H, Liu K, Liao X, Yan S, Yin B, Ouyang Y, Xiao H. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for predicting post-operative pulmonary infection in gastric cancer patients following radical gastrectomy. Sci Rep. 2019;9:14587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mazzucchi E. Both the nomogram and the score system can represent an useful tool especially in those cases where the complication is foreseen by the surgeon. Int Braz J Urol. 2022;48:828-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, Antonelli M, Anzueto A, Beale R, Brochard L, Brower R, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, Rhodes A, Slutsky AS, Vincent JL, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ranieri VM. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1573-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1051] [Cited by in RCA: 999] [Article Influence: 71.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Linden PA, Towe CW, Watson TJ, Low DE, Cassivi SD, Grau-Sepulveda M, Worrell SG, Perry Y. Mortality After Esophagectomy: Analysis of Individual Complications and Their Association with Mortality. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:1948-1954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu B, Ge Y, Lu Y, Chen Q, Zhang H. Risk factors and prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome following abdominal surgery. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Giannoula Y, Kroemer G, Pietrocola F. Cellular senescence and the host immune system in aging and age-related disorders. Biomed J. 2023;46:100581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ruan Z, Li D, Huang D, Liang M, Xu Y, Qiu Z, Chen X. Relationship between an ageing measure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung function: a cross-sectional study of NHANES, 2007-2010. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e076746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ye C, Yuan L, Wu K, Shen B, Zhu C. Association between systemic immune-inflammation index and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23:295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pleiss KL, Mosley DD, Bauer CD, Bailey KL, Ochoa CA, Knoell DL, Wyatt TA. Comparative effects of e-cigarette and conventional cigarette smoke on in vitro bronchial epithelial cell responses. Toxicol Lett. 2025;407:32-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Caliri AW, Tommasi S, Besaratinia A. Relationships among smoking, oxidative stress, inflammation, macromolecular damage, and cancer. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2021;787:108365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 84.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang K, Liao Y, Li X, Wang R, Zeng Z, Cheng M, Gao L, Xu D, Wen F, Wang T, Chen J. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase prevents cigarette smoke exposure-induced formation of neutrophil extracellular traps and improves lung function in a mouse model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;114:109537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Qiu J, Li Z, Li L, Tian H. Timing effects of short-term smoking cessation on lung cancer postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22:293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Quan H, Ouyang L, Zhou H, Ouyang Y, Xiao H. The effect of preoperative smoking cessation and smoking dose on postoperative complications following radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a retrospective study of 2469 patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang Y, Wang L, Ma S, Cheng L, Yu G. Repair and regeneration of the alveolar epithelium in lung injury. FASEB J. 2024;38:e23612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Páramo JA. Microvascular thrombosis and clinical implications. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;156:609-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lan CC, Su WL, Yang MC, Chen SY, Wu YK. Predictive role of neutrophil-percentage-to-albumin, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratios for mortality in patients with COPD: Evidence from NHANES 2011-2018. Respirology. 2023;28:1136-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pompili E, Zaccherini G, Baldassarre M, Iannone G, Caraceni P. Albumin administration in internal medicine: A journey between effectiveness and futility. Eur J Intern Med. 2023;117:28-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wang W, Ma D, Li T, Ying Y, Xiao W. People with older age and lower FEV1%pred tend to have a smaller FVC than VC in pre-bronchodilator spirometry. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2014;194:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Choi KY, Lee HJ, Lee JK, Park TY, Heo EY, Kim DK, Lee HW. Rapid FEV(1)/FVC Decline Is Related With Incidence of Obstructive Lung Disease and Mortality in General Population. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38:e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yao Z, Shang W, Yang F, Tian W, Zhao G, Xu X, Md RZ, Tian T, Li W, Huang M, Zhao Y, Huang Q. Nomogram for predicting severe abdominal adhesions prior to definitive surgery in patients with anastomotic fistula post-small intestine resection: a cohort study. Int J Surg. 2025;111:2046-2054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/