Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112841

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: October 30, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 139 Days and 15.8 Hours

The pleiotropic effects of statins, including anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions, have prompted investigation into their perioperative role in colo

To evaluate the association between statin therapy and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing CRC surgery.

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar through March 2025. Five cohort studies evaluating statin use in CRC surgery were included. Primary outcomes assessed included anastomotic leak, surgical site infection, and 30-day and 90-day mortality. Data on statin duration and con

Three studies investigated the rates of anastomotic leaks in patients who used statins compared to those who did not. Two of the studies found no significant difference, while one noted a marginally higher leak rate among statin users. Diabetes, smoking habits, and operative time were found to be common confounding factors. Conversely, the use of statins was consistently linked to a decrease in 30-day mortality in propensity-matched groups, although findings regarding 90-day mor

Statin therapy may confer short-term survival benefits in CRC surgical patients, potentially via anti-inflammatory or cytoprotective mechanisms. While evidence regarding anastomotic leaks remains inconclusive, trends suggest improved postoperative outcomes. These findings are constrained by methodological heterogeneity, underscoring the need for prospective, randomized studies to confirm benefits and identify optimal patient subgroups.

Core Tip: This review evaluates the impact of statin therapy on postoperative outcomes following colorectal cancer surgery. The study focuses on cohort studies to show how statin use, particularly its timing and duration, may affect the risk of anastomotic leaks, surgical site infection, and short-term mortality. Despite conflicting data, a consistent trend toward reduced 30-day mortality was observed. Overall, these findings suggest the potential role of statins in colorectal cancer surgery, however due to the heterogeneity in definitions of statin therapy and limitations of study design there is a need for prospective studies to confirm their role in improving postsurgical outcomes.

- Citation: Mohsin S, Hasan M, Mustafa F, Kumar J, Aleissa M, Bhullar JS, Kumar S. Impact of statin therapy on postoperative outcomes following colorectal cancer surgery: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 112841

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/112841.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112841

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide[1]. For patients with resectable CRC, surgery remains a mainstay treatment option along with standard therapies, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy[2]. Nevertheless, significant colorectal surgery carries a notable risk of postoperative complications, with approximately one-third of patients experiencing adverse outcomes like anastomotic leak, small bowel obstruction, surgical site infections, intra-abdominal abscess, ileus, and bleeding. The primary risk factors that increase the likelihood of these complications include advanced age, history of hypertension, metastatic diseases, and comorbidities such as cardiorespiratory issues[3-5]. The stress reaction to surgical procedures is characterized by the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, which is triggered by the release of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6 into the peritoneal cavity. These cytokines subsequently enhance the synthesis of C-reactive protein, which has been associated with an increase in complications following colorectal surgery[6,7]. Moreover, associations of prolonged presence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and increased concentration of these cytokines have been correlated with the incidence of postoperative complications[7].

Additionally, tumor recurrence is a major challenge following surgical resection. In a five-year-follow-up study of 237 patients, 24.9% of patients experienced recurrence of disease despite standardized postoperative surveillance, which included 3-monthly carcinoembryonic antigen levels, annual imaging with computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and colonoscopy within the first postoperative year if no preoperative colonoscopy was performed, followed by a repeated colonoscopy after 3 years. Recurrence was most commonly detected by rising carcinoembryonic antigen levels, clinical symptoms and surveillance imaging in 40.7%, 32.2%, and 27.1% patients respectively with the liver and lungs being the predominant sites of recurrence. The findings of this study suggest that recurrence may not be caused by surgery itself but rather be reflective of the complex underlying tumor biology and stage which further emphasizes the need for vigilant postoperative surveillance and adjunctive therapies to improve long-term outcomes following surgery[8]. Therefore, the aforementioned clinical challenges warrant exploration of adjunctive strategies that may potentially mitigate postoperative complications and improve outcomes and morbidity in patients undergoing CRC surgery.

Although commonly used as primary therapy for the treatment of dyslipidemia, several observational studies have explored the pleiotropic effects of statins in this patient demographic. Findings have displayed lower rates of anastomotic leak, sepsis, and short-term mortality in statin users following surgery for CRC[9-11], underscoring the potential protective effects of adjunct statin therapy. Additionally, the onco-protective effects of statins are further highlighted in a meta-analysis by Li et al[12] which pooled data from 40659 patients with CRC and demonstrated a reduction in cancer-specific mortality among statin users. Although the analysis did not stratify outcomes by colon vs rectal cancer, the findings remain relevant given that rectal cancer represents a subset of CRC, hence providing important context while also emphasizing the need for stratified studies based on tumor location. In the context of clinical benefit, the therapeutic effects associated with statin use during the preoperative phase are supported by their anti-inflammatory properties, which directly reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines released due to surgical stress, such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α[13]. Managing both local and systemic inflammation can help avoid postoperative complications. Therefore, the existing literature provides a solid theoretical basis for hypothesizing the connection between statins and their contributions to short-term postoperative outcomes.

However, it is to be noted that despite this growing evidence supporting the beneficial effects of statins in colorectal surgery, the current body of literature majorly consists mainly of observational studies in which the data are significantly limited by variability in methodology, statin type, dosage, therapy duration, and inconsistent outcome definitions. Hence, acknowledging the substantial heterogeneity and limited data for a robust analysis, this narrative synthesis aims to systematically review and comprehensively synthesize the findings of statin therapy in patients with CRC with a specific focus on the assessment of duration of statin therapy and incidence of postoperative complications, inclusive of ana

The primary objective of this review was to assess the relationship between statin therapy and postoperative outcomes, including anastomotic leak, 30-day and 90-day mortality, and surgical site infections while identifying and addressing potential confounding factors influencing these outcomes, such as comorbidities, cancer stage, and surgical type or technique.

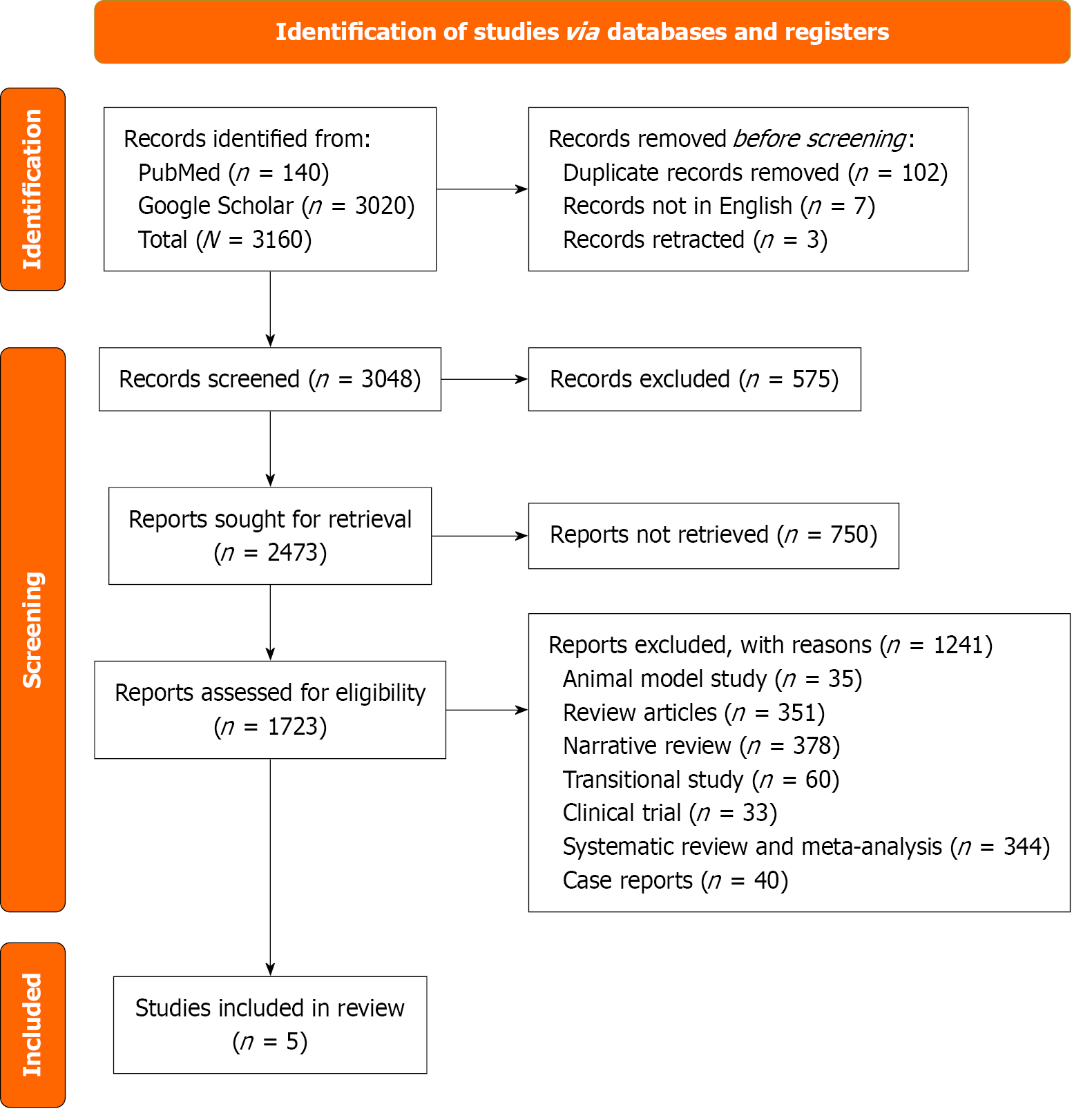

A systematic search of PubMed and Google Scholar databases was conducted, without language restrictions using the following search string until March 2025: (“preoperative statin therapy” OR “statin use around surgery” OR “statins and surgical outcomes” OR “atorvastatin” OR “simvastatin” OR “rosuvastatin” OR “pravastatin” OR “lovastatin” OR “fluvastatin” OR “pitavastatin”) AND (“rectal cancer surgery” OR “colorectal resection” OR “colorectal surgery” OR “rectal cancer” OR “colorectal cancer” OR “colorectal cancer outcomes”).

Screening of articles followed a three-stage process: (1) Titles screened and titles not relevant to the topic were excluded; (2) Abstract review with removal of duplicates; and (3) Full-text review for statin use and reported outcomes. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses standards were followed[14]. Results from the search strategy are summarized in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram Figure 1.

The 5 cohort studies were included[9-11,15,16]. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), evaluating selection, comparability, and outcome domains. A maximum of 9 stars could be assigned to each study. Quality assessment scores are detailed in Table 1. This scale contains eight items categorized into three dimensions: Selection, comparability, and outcome. For each item, a star system is used to grade the studies, allowing a semi-quantitative assessment of study quality. The highest quality studies are awarded a maximum of one star for each item except for the item related to the comparability dimension, which allows the assignment of two stars.

| Dimension | Selection | |||

| Ref. | Representative of the exposed cohort | Selection of the nonexposed control | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome of interest not present at the start of the study |

| Löffler et al[16] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bahl et al[15] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pourlotfi et al[9] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Disbrow et al[10] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fransgaard et al[11] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Comparability; comparability of cohorts; control of important and additional factors | ||||

| Löffler et al[16] | 2 | |||

| Bahl et al[15] | 1 | |||

| Pourlotfi et al[9] | 1 | |||

| Disbrow et al[10] | 1 | |||

| Fransgaard et al[11] | 1 | |||

| Ref. | Assessments of outcomes | Sufficient follow up time for outcomes to occur | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | |

| Löffler et al[16] | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Bahl et al[15] | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Pourlotfi et al[9] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Disbrow et al[10] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Fransgaard et al[11] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ref. | Total | |||

| Löffler et al[16] | 8 | |||

| Bahl et al[15] | 7 | |||

| Pourlotfi et al[9] | 8 | |||

| Disbrow et al[10] | 8 | |||

| Fransgaard et al[11] | 8 | |||

Overall, all studies assessed were classified as high quality, with the majority achieving a score of 8 on the NOS, while Bahl et al[15] received a score of 7 due to this being a single-center study with a comparatively smaller sample size, and limited follow-up documentation. The variations in NOS scoring highlight differences in study designs, sources of data, and reporting quality, which may directly impact the robustness of the conclusions made. Löffler et al[16], achieved the highest comparability score by utilizing propensity-score (PS) matching and making comprehensive adjustments for both perioperative and oncologic factors. Conversely, Pourlotfi et al[9], Disbrow et al[10], Fransgaard et al[11], and Bahl et al[15], were assigned lower scores due to less extensive adjustment for covariates and reduced control over factors such as surgical urgency, comorbidities, and institutional variables. Outcome scores also differed; Pourlotfi et al[9], Disbrow et al[10], and Fransgaard et al[11], profited from data linked to registries and standardized mortality reporting, while Löffler et al[16], and Bahl et al[15], lost points due to gaps in follow-up documentation, which could lead to underestimating late complications. These differences emphasize that mortality findings are reliable across high-quality registry studies, while variations in complication rates, particularly concerning anastomotic leaks, are largely influenced by smaller, lower-scoring studies. In summary, although all studies are deemed high quality, registry and propensity score matched based designs provide the most persuasive evidence, whereas single-center studies should be regarded as supplementary and capable of generating hypotheses.

Due to heterogeneity in study design, patient populations, statin regimens, outcome definitions, and surgical techniques, quantitative pooling was not feasible. Therefore, we employed a narrative synthesis approach, organizing findings around key outcomes inclusive of: (1) Duration of statin therapy (preoperative, perioperative, short or long-term use); (2) Anastomotic leak; (3) Short-term postoperative mortality at 30 days and 90 days; and (4) Surgical site infection and wound infection.

Despite improvements in surgical and adjuvant treatments, CRC continues to rank among the world’s top causes of cancer-related morbidity and death, with a high recurrence rate. These challenges have prompted interest in adjunctive therapies that may improve perioperative results and long-term prognosis. Among these, statins have emerged as a potential candidate. Beyond their lipid-lowering benefits, statins have drawn interest in their possible anti-tumor characteristics as researchers continue to investigate additional techniques to enhance patient outcomes.

Traditionally, used for hypercholesterolemia, statins completely block 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, the key rate-limiting enzyme that regulates the conversion of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A to mevalonic acid[17]. This pathway is essential for not only cholesterol synthesis but also for intracellular signaling networks, involving Ras and Rho proteins which are known drivers of cancer cell proliferation, motility, and survival[18]. Inhibition of this pathway induces apoptosis, inhibits cell proliferation and angiogenesis, as well as regulates cell motility and shape in several malignancies, including preclinical models of CRC[19,20]. Furthermore, obesity, smoking, and physical inactivity are common risk factors for both CRC and cardiovascular disease, lending support to the biological possibility that statins may have dual protective benefits[21].

Three of the studies included in our narrative synthesis assessed the prevalence of anastomotic leak in patients on statins undergoing colorectal surgery. Table 2 provides a comparative summary of findings related to anastomotic leak. These included a nationwide registry-based study by Fransgaard et al[11], one large retrospective cohort study by Disbrow et al[10], and a smaller-scale retrospective analysis by Bahl et al[15]. In the study by Disbrow et al[10], leak rates were slightly lower in statin users compared to non-users in both unadjusted (2.05% vs 2.28%, P = 0.603) and propensity score matched cohorts (2.01% vs 2.76%, P = 0.181). However, neither comparison reached statistical significance. Similar findings were reported by Fransgaard et al[11], finding no significant difference in leak risk between groups, reporting an odds ratio (OR) of 1.03 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.90-1.18, P = 0.80]. Moreover, the subgroup analysis revealed that statin monotherapy was linked to a reduced risk of postoperative complications. Pourlotfi et al[9], Fransgaard et al[11], along Disbrow et al[10] did not reveal a notable rise in leak rates, benefiting from larger sample sizes and, in certain instances, standardized reporting for complications that include clear diagnostic criteria such as radiologic confirmation, clinical symptoms, or the need for reoperation, along with follow-up at 30 days or 90 days. However, our third study for this outcome, Bahl et al[15], reported a higher leak rate in statin users, 5.8% (8 out of 137 patients), and 4.5% in non-statin users (3 out of 67 patients). likely attributed to its smaller sample size and incomplete follow-up, which hinders the reliability of its conclusions. These differences highlight that variations in study size, definitions of statin exposure, and completeness of follow-up significantly influence reported rates of complications, with smaller studies contributing to contradictory results on infrequent occurrences such as anastomotic leaks.

| Disbrow et al[10] | Fransgaard et al[11] | Bahl et al[15] | |

| Statin therapy definition | No information available concerning statin medication choice, dose, and duration of use | Statin user is defined as redeeming 2 or more statin prescriptions 1 year before surgery; postoperative continuation period not stated | Short-term statin therapy group: Preoperative statin use (3-7 days) and postoperative duration (14 days); long-term statin therapy group: Ongoing statin therapy |

| Type of surgical data | Colectomy and rectal resection combined and separate | Combined colorectal | Combined colorectal |

| Comorbidities | Diabetes; COPD; ascites/cirrhosis; hypertension; congestive heart failure | NR | NR |

| Results | Unadjusted (statin n/N) 41/1810, PS matched (statin n/N) 35/1786; Unadjusted (non-statin n/N) 56/3196, PS Matched (non-statin n/N) 48/1786 | OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.90-1.18, P = 0.80 | Statin (n/N) 8/137; Non-statin (n/N) 3/67 |

These findings are reflective of larger trends in the existing literature, which shows that the impact of statins on surgical outcomes, particularly anastomotic healing, remains uncertain. In CRC surgery, anastomotic leak remains one of the most serious complications[22], associated with greater mortality and morbidity rates, especially in the early post-operative phase[23]. The risk of anastomotic leak occurring in CRC patients is correlated to distal location, large tumor size, advanced stage, and metastatic disease[24]. Although smaller-scale retrospective investigations, like the one conducted by Singh et al[24], that reported a considerably lower anastomotic leak incidence with statin medication (1.2% vs 6.6%, P = 0.031), have previously demonstrated a protective benefit of statins, these findings have not been consistently reproduced[25]. However, larger studies have failed to demonstrate a significant correlation between perioperative statin use and the occurrence of anastomotic leak, according to data collected prospectively[26].

It is necessary to take into account the known risk factors for anastomotic leak when analyzing these findings, since they may significantly influence the outcomes of studies evaluating the effects of statins on anastomotic healing. Well-established preoperative factors include male sex, obesity, diabetes, smoking, and malnutrition, all of which can impair wound healing and increase the fragility of the anastomotic site[27]. Prolonged operational duration, significant blood loss, and the requirement for transfusions have been shown to contribute to an increased risk of anastomotic leak[28]. In particular, multivariate analyses have shown that extended surgical time may be a risk factor for anastomotic leak[29]. Anastomotic leak risk is further influenced by surgical methods and the location of the tumor; low rectal anastomosis, which are frequently required by tumors in the middle or lower third of the rectum, are especially vulnerable because of the possibility of microvascular insufficiency[30]. However, studies exploring the relationship between anastomotic leak incidence and micro vessel density at the anastomotic location have revealed contradictory findings[31]. Furthermore, the risk of anastomotic leak has been linked to modifiable lifestyle variables such as alcohol use, smoking, and poor nutritional condition[30]. In studies evaluating the effect of statins on anastomotic healing, these variables may serve as confounders, particularly in groups with heterogeneous risk. The results of a dual-component thesis by Christopher[31] which comprised a clinical and laboratory examination of the effect of statins in anastomotic healing, further support these findings. Although there was no statistically significant difference in anastomotic leak rates between statin and non-statin users in the clinical arm (113 patients), the experimental arm showed that atorvastatin increased the metabolic activity and proliferation of colonic myofibroblasts, which are cells necessary for tissue repair[31]. The idea that statins may improve anastomotic healing by altering the wound repair microenvironment is supported by this mechanistic understanding. To accurately determine which patient subgroups might gain advantages from statin medication during the perioperative period, the biological reasoning behind this must be confirmed through comprehensive, well-regulated, prospective research.

Statin use has been known to be associated with a significant reduction in all-cause post-operative mortality in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery[32]. The studies aim to determine if comparable advantages apply to patients having CRC surgery.

For 30-day mortality, Pourlotfi et al[9] reported identical effects of statins in both unadjusted and propensity score matched cohorts (8/3019 statin users vs 8/3017 non-users; 8/3017 statin users vs 112/3017 non-users, respectively), suggesting a protective effect of statins. Similarly, Disbrow et al[10] reported a reduced mortality rate in a propensity score-matched cohort of statin users (12/1786) compared to non-users (24/1786). However, in contrast, Fransgaard et al[11] by using a larger cohort, found no statistically significant difference between groups (316/5961 statin users vs 1347/23391 non-users), suggesting potential population heterogeneity.

For 90-day mortality, Pourlotfi et al[9] again found no difference in outcomes between statin and non-statin groups in matched cohorts (20/3017 vs 166/3017). However, without adjusting for covariates or propensity score matching, Löffler et al[16] showed a slight mortality advantage (217/3654 in statin users vs 242/3654 in non-users).

Subgroup analysis conducted in Pourlotfi et al[9] showed that non-statin users had a higher risk of mortality due to cardiovascular events, sepsis, respiratory complications, and multi-organ failure. This supports a biological rationale for the protective effects of statins, rooted in their anti-inflammatory, endothelial-stabilizing, immunomodulatory, and antithrombotic properties. These findings were confirmed by the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program study of 7777 non-cardiac surgery patients, as 19.7% of whom had colorectal resections. Statins were associated with a reduced risk of major non-cardiac complications (OR = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.49-0.92, P < 0.001), respiratory complications (OR = 0.63, 95%CI: 0.50-0.79, P = 0.017), venous thromboembolism (OR = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.18-0.98, P = 0.044), and infectious complications defined as organ space surgical site infections, sepsis, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (OR = 0.65, 95%CI: 0.45-0.94, P = 0.023)[33]. However, this data was not specific to CRC, emphasizing the need for more studies investigating the effects of statin therapy on mortality in CRC surgery.

The variability in the assessment of this outcome among these studies underscores the need to study underlying confounding factors, which can potentially contribute to this difference in results. Pre-existing conditions like atrial fibrillation (OR = 2.70, 95%CI: 1.53-4.89, P = 0.001), heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (OR = 2.02, 95%CI: 1.07-3.80, P = 0.029) are associated with increased risk of postoperative complications[34]. A study by Walsh et al[35] further confirms that patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation demonstrated poorer all-cause mortality. A 2004 population-based study highlighted the role of COPD with 13-day mortality in patients undergoing CRC surgery, with 13% of patients with COPD compared to only 5.3% without COPD[36]. Additionally, Lemmens et al[37] showed that greater incidences of pneumonia and postoperative hemorrhage after CRC resections are linked to COPD. A comparative overview of the studies assessing postoperative mortality is presented in Tables 3 and 4. To summarize, Pourlotfi et al[9] observed a notable decrease in both 30-day and 90-day mortality rates associated with statin usage, whereas Löffler et al[16] found a protective effect at 90 days but not at 30 days. Fransgaard et al[11] reported no correlation at either time interval, underscoring the variability present even within extensive registry-based studies. This data is backed by large national databases, nearly complete follow-up, and thorough adjustments for comorbidities and perioperative risk factors. Disbrow et al[10] despite possessing strong statistical power, is yet constrained by its single-center design, which impacts the generalizability of the results. Altogether, these results imply that the potential survival advantage of statins is primarily supported by studies based on large registries, while single-center studies offer supporting evidence that is less conclusive.

| Pourlotfi et al[9] | Disbrow et al[10] | Fransgaard et al[11] | |

| Statin therapy definition | User defined as redeeming 1 or more statin prescriptions 1 year before surgery; postoperative continuation period not stated | Ongoing statin therapy No information reported of statin duration of use | Statin user defined as redeeming 2 or more statin prescriptions 1 year before surgery; postoperative continuation period not stated |

| Type of surgical data | Rectal cancer only | Colectomy and rectal resection combined and separate | Combined colorectal |

| Surgical procedure | Anterior resection; abdominoperineal resection Hartmann’s operation | ||

| Comorbidities | Diabetes; COPD; liver disease, hypertension; congestive heart failure | Diabetes; COPD; ascites/cirrhosis; hypertension; congestive heart failure | |

| Results | Unadjusted (statin n/N) 8/3019, PS matched (statin n/N) 8/3017; unadjusted (non-statin n/N) 8/3017, PS matched (non-statin n/N) 112/3017 | Unadjusted (statin n/N) 27/2515, PS matched (statin n/N) 12/1786; unadjusted (non-statin n/N) 35/4770; PS matched (non-statin n/N) 24/1786 | Statin (n/N) 316/5961; non-statin (n/N) 1347/23391 |

| Pourlotfi et al[9] | Löffler et al[16] | |

| Statin therapy definition | User defined as redeeming 1 or more statin prescriptions 1 year before surgery; postoperative continuation period not stated | Prescribed statins with prescriptions active or in use during the period spanning up to 365 days before surgery |

| Type of surgical data | Rectal cancer only | Colectomy and rectal resection combined and separate |

| Surgical procedure | Anterior resection; abdominoperineal resection Hartmann’s operation | |

| Comorbidities | Diabetes; COPD; liver disease, hypertension; congestive heart failure | |

| Results | Unadjusted (statin n/N) 20/3019, PS matched (statin n/N) 20/3017; unadjusted (non-statin n/N) 291/8947, PS matched (non-statin n/N) 166/3017 | Statin (n/N) 217/3654; non-statin (n/N) 242/3654 |

Diabetes is another key predictor of surgical outcomes. A recent large-scale study reported that diabetes was present in 3% to 57% of patients diagnosed with CRC[38]. This review further highlighted how patients with diabetes experienced poorer disease-free survival and had higher overall and cancer-specific mortality rates. In studies that specifically examined colorectal surgery outcomes, results remained conflicting. While Anand et al[39] used the United States Nationwide Inpatient Sample database to report a 23% lower mortality and fewer perioperative complications in diabetic patients compared to their non-diabetic counterparts, Fransgaard et al[40] found an increased 30-day mortality in diabetic patients but no significant difference in postoperative complications. These conflicting results highlight the intricacy of comorbid factors on the results of CRC surgery and the requirement for more detailed investigation in further research.

These comorbidities not only lead to heterogeneity in the outcomes of CRC surgery, but they may also influence the effects of statin therapy in these patients. It is plausible to assume that different patient subgroups may experience varying degrees or directions of statin benefits, depending on their initial risk factors. For instance, patients with cardiovascular issues might gain more advantages from the anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective properties of statins, while those suffering from significant metabolic disorders or with poor pulmonary function might see a lesser effect[41,42]. In high-risk groups undergoing CRC surgery, this highlights the importance of conducting stratified studies to evaluate the effectiveness of statins.

The type of surgery, rectal, colon, or combined surgery was not unified across the studies used in our synthesis. For instance, Disbrow et al[10], conducted a subgroup analysis of rectal resections, comparing 485 propensity score matched patients who had rectal cancer, but the results were not statistically significant for 30-day mortality, although a trend for better survival was noticed in the statin cohort (0.21% vs 1.44%, P = 0.076). On the other hand, because Fransgaard et al[11] data consisted of elective and emergency surgeries, colon and rectal resections, and no subgroup analysis, it is challenging to interpret. The authors of this study themselves proposed that emergency and elective resections have to be evaluated independently since emergency patients often had poorer morbidity, higher early mortality, and less favorable oncological outcomes. In contrast, Pourlotfi et al[9], only involved rectal cancer resections, allowing for more narrow observations.

This variation in surgical approach is significant in the context of surgical site infections, which can eventually contribute to mortality, especially when CRC surgery poses the risk of infection up to 30%[43]. Existing studies have suggested that rates of surgical site infection might not be the same in colon and rectal surgery[44,45]. This is probably because rectal surgeries are complicated and frequently include ostomy construction, preoperative radiation, anastomosis close to the anal margin, and complete mesorecta excision, all of which increase the risk of contamination and lengthen the operating time[46-48]. Within our synthesis, two studies by Bahl et al[15] and Disbrow et al[10] explicitly reported these postoperative complications; Bahl et al[15] reported wound infections, while Disbrow et al[10] documented surgical site infections. Therefore, it is essential to consider the type of resection performed when evaluating outcomes like infection rates or death in statin related research, as colon and rectal procedures are linked to different risk profiles and operational challenges, and these complications can escalate morbidity and directly impact survival.

In addition to comorbidities and surgical procedures, postoperative outcomes are influenced by system-level variables. Despite controlling for age, comorbidities, cancer stage, and surgical urgency, a major National Health Service analysis of more than 160000 CRC procedures from 1998 to 2006 revealed considerable variance in 30-day mortality between institutions[49]. This implies that institutional procedures that affect survival include surgical technique and perioperative care. As a result, the mortality benefit of statins may also differ depending on the type of care received, with hospitals that provide high-quality, standardized postoperative care perhaps seeing greater results.

While epidemiological data show that statin usage may reduce CRC incidence and death, the findings are contradictory, demanding more research into their clinical impact, particularly in perioperative settings when recurrence and recovery are crucial outcomes. It is also important to note that across the current literature assessing statin use in CRC in this narrative synthesis, the specific types of statins used are not consistently reported. Evidence stated in a review by Longo et al[50], suggests that lipophilic statins may penetrate extrahepatic tissues more effectively than hydrophilic statins, hypothesizing that lipophilic statin use may be associated with reduced cancer incidence and recurrence comparative to hydrophilic statins. Hence, this lack of stratification in available literature specific to patients with CRC limits conclusive interpretation of whether certain statin subtypes may have superior or differential protective effects, representing a key limitation that future studies should assess. Furthermore, an important contributor to be noted towards the discrepancies observed across the outcomes of our narrative synthesis may be due to varying definitions of statin users in relation to dosage and duration among the included studies. Pourlotfi et al[9], Fransgaard et al[11], and Löffler et al[16], classified statin users as patients who had redeemed prescriptions within one year prior to surgery but did not specify whether statin therapy was continued postoperatively. Similarly, Disbrow et al[10], defined users as being on ongoing therapy, without clarification on further detail of this definition. In contrast, Bahl et al[15], uniquely differentiated between short-term and long-term statin therapy among patients. Users on short-term therapy were stated to be on stain therapy 3-7 days preoperatively and 14 days postoperatively, whereas long-term therapy was defined as ongoing use without specified time. Thus, these variations in exposure definition limit our ability to extrapolate findings to draw a firm conclusion on why the outcomes of anastomotic leak and mortality differed among these studies. Further studies with consideration of homogenous definitions may aid in clarifying whether duration of therapy and dosage has an effect on postoperative outcomes. Moreover, differences in study designs may have had influence on the conflicting findings as well. The included studies in this narrative synthesis were all retrospective cohorts with varying sample sizes and scope of analyses. Larger registry-based cohorts such as those by Pourlotfi et al[9] (n = 11966), Disbrow et al[10] (n = 7285), Fransgaard et al[11] (n = 29532), and Löffler et al[16] (n = 7120) have substantial statistical power yet have limitations due to the observational study design and reliance on prescription databases which do not fully account for confounders such as patient adherence. Conversely, smaller single-center cohorts such as Bahl et al[15] (n = 204) have restricted generali

Taken together, this heterogeneity in study design, definitions of statin exposure inclusive of dosage and duration, and lack of stratification by statin subtype likely contributes to the conflicting findings on anastomotic leak and mortality, underscoring the importance for standardized definitions and prospective designs in future research.

Statin treatment may provide short-term survival advantages for patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer, likely through anti-inflammatory or cytoprotective effects. Evidence also suggests possible reductions in post-operative com

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68750] [Article Influence: 13750.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 2. | Kumar A, Gautam V, Sandhu A, Rawat K, Sharma A, Saha L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches for colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:495-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Kirchhoff P, Clavien PA, Hahnloser D. Complications in colorectal surgery: risk factors and preventive strategies. Patient Saf Surg. 2010;4:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tevis SE, Kennedy GD. Postoperative Complications: Looking Forward to a Safer Future. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:246-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Silaghi A, Serban D, Tudor C, Cristea BM, Tribus LC, Shevchenko I, Motofei AF, Serboiu CS, Constantin VD. A Review of Postoperative Complications in Colon Cancer Surgery: The Need for Patient-Centered Therapy. J Mind Med Sci. 2025;12:21. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | McKechnie T, Cloutier Z, Archer V, Park L, Lee J, Heimann L, Patel A, Hong D, Eskicioglu C. Using preoperative C-reactive protein levels to predict anastomotic leaks and other complications after elective colorectal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2024;26:1114-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Singh PP, Lemanu DP, Soop M, Bissett IP, Harrison J, Hill AG. Perioperative Simvastatin Therapy in Major Colorectal Surgery: A Prospective, Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:308-320.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gunawardene A, Desmond B, Shekouh A, Larsen P, Dennett E. Disease recurrence following surgery for colorectal cancer: five-year follow-up. N Z Med J. 2018;131:51-58. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Pourlotfi A, Ahl R, Sjolin G, Forssten MP, Bass GA, Cao Y, Matthiessen P, Mohseni S. Statin therapy and postoperative short-term mortality after rectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:875-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Disbrow D, Seelbach CL, Albright J, Ferraro J, Wu J, Hain JM, Shanker BA, Cleary RK. Statin medications are associated with decreased risk of sepsis and anastomotic leaks after rectal resections. Am J Surg. 2018;216:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fransgaard T, Thygesen LC, Gögenur I. Statin use is not associated with improved 30-day survival in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:199-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sodha NR, Sellke FW. The effect of statins on perioperative inflammation in cardiac and thoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:1495-1501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li L, Cui N, Hao T, Zou J, Jiao W, Yi K, Yu W. Statins use and the prognosis of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021;45:101588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 52040] [Article Influence: 10408.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Bahl P, Jin J, Hill A, Singh PP. Perioperative statin therapy and long-term outcomes following major colorectal surgery: a retrospective cohort study. AME Surg J. 2024;4:3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Löffler L, Gögenur I, Gögenur M. Correlations between preoperative statin treatment with short- and long-term survival following colorectal cancer surgery: a propensity score-matched national cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024;39:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bonetti PO, Lerman LO, Napoli C, Lerman A. Statin effects beyond lipid lowering--are they clinically relevant? Eur Heart J. 2003;24:225-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sleijfer S, van der Gaast A, Planting AS, Stoter G, Verweij J. The potential of statins as part of anti-cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:516-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Boudreau DM, Yu O, Johnson J. Statin use and cancer risk: a comprehensive review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010;9:603-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gauthaman K, Fong CY, Bongso A. Statins, stem cells, and cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:975-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lakha F, Theodoratou E, Farrington SM, Tenesa A, Cetnarskyj R, Din FV, Porteous ME, Dunlop MG, Campbell H. Statin use and association with colorectal cancer survival and risk: case control study with prescription data linkage. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Güenaga KF, Matos D, Wille-Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011:CD001544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bertelsen CA, Andreasen AH, Jørgensen T, Harling H; Danish Colorectal Cancer Group. Anastomotic leakage after curative anterior resection for rectal cancer: short and long-term outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:e76-e81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Singh PP, Srinivasa S, Bambarawana S, Lemanu DP, Kahokehr AA, Zargar-Shoshtari K, Hill AG. Perioperative use of statins in elective colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:205-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bisgård AS, Noack MW, Klein M, Rosenberg J, Gögenur I. Perioperative statin therapy is not associated with reduced risk of anastomotic leakage after colorectal resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:980-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Midura EF, Hanseman D, Davis BR, Atkinson SJ, Abbott DE, Shah SA, Paquette IM. Risk factors and consequences of anastomotic leak after colectomy: a national analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:333-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Harada T, Numata M, Atsumi Y, Fukuda T, Izukawa S, Suwa Y, Watanabe J, Sato T, Saito A. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage in rectal cancer surgery reflecting current practices. Surg Today. 2025;55:1043-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yi X, Huang Y, He Y, Chen C. Risk Factors Associated with Anastomotic Leakage in Colorectal Cancer. Indian J Surg. 2019;81:154-163. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Qin Q, Zhu Y, Wu P, Fan X, Huang Y, Huang B, Wang J, Wang L. Radiation-induced injury on surgical margins: a clue to anastomotic leakage after rectal-cancer resection with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy? Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2019;7:98-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zarnescu EC, Zarnescu NO, Costea R. Updates of Risk Factors for Anastomotic Leakage after Colorectal Surgery. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11:2382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Christopher B. A clinical and scientific study to investigate the influence of statins on anastomotic healing in colorectal surgery. University of Liverpool, 2021. |

| 32. | Berwanger O, Le Manach Y, Suzumura EA, Biccard B, Srinathan SK, Szczeklik W, Santo JA, Santucci E, Cavalcanti AB, Archbold RA, Devereaux PJ; VISION Investigators. Association between pre-operative statin use and major cardiovascular complications among patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery: the VISION study. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:177-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Iannuzzi JC, Rickles AS, Kelly KN, Rusheen AE, Dolan JG, Noyes K, Monson JR, Fleming FJ. Perioperative pleiotropic statin effects in general surgery. Surgery. 2014;155:398-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Flynn DE, Mao D, Yerkovich ST, Franz R, Iswariah H, Hughes A, Shaw IM, Tam DPL, Chandrasegaram MD. The impact of comorbidities on post-operative complications following colorectal cancer surgery. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0243995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Walsh SR, Gladwish KM, Ward NJ, Justin TA, Keeling NJ. Atrial fibrillation and survival in colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2004;2:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Platon AM, Erichsen R, Christiansen CF, Andersen LK, Sværke C, Montomoli J, Sørensen HT. The impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on intensive care unit admission and 30-day mortality in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a Danish population-based cohort study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2014;1:e000036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lemmens VE, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Houterman S, Verheij KD, Martijn H, van de Poll-Franse L, Coebergh JW. Which comorbid conditions predict complications after surgery for colorectal cancer? World J Surg. 2007;31:192-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Mills KT, Bellows CF, Hoffman AE, Kelly TN, Gagliardi G. Diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer prognosis: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1304-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Anand N, Chong CA, Chong RY, Nguyen GC. Impact of diabetes on postoperative outcomes following colon cancer surgery. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:809-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fransgaard T, Thygesen LC, Gögenur I. Increased 30-day mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:O22-O29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Cao C, Wu Y, Xu Z, Lv D, Zhang C, Lai T, Li W, Shen H. The effect of statins on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational research. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zhang W, Zhang Y, Li CW, Jones P, Wang C, Fan Y. Effect of Statins on COPD: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Chest. 2017;152:1159-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Bullard KM, Trudel JL, Baxter NN, Rothenberger DA. Primary perineal wound closure after preoperative radiotherapy and abdominoperineal resection has a high incidence of wound failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:438-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Smith RL, Bohl JK, McElearney ST, Friel CM, Barclay MM, Sawyer RG, Foley EF. Wound infection after elective colorectal resection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:599-605; discussion 605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Nichols RL, Choe EU, Weldon CB. Mechanical and antibacterial bowel preparation in colon and rectal surgery. Chemotherapy. 2005;51 Suppl 1:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Enker WE, Merchant N, Cohen AM, Lanouette NM, Swallow C, Guillem J, Paty P, Minsky B, Weyrauch K, Quan SH. Safety and efficacy of low anterior resection for rectal cancer: 681 consecutive cases from a specialty service. Ann Surg. 1999;230:544-52; discussion 552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Law WL, Chu KW. Anterior resection for rectal cancer with mesorectal excision: a prospective evaluation of 622 patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:260-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Tang R, Chen HH, Wang YL, Changchien CR, Chen JS, Hsu KC, Chiang JM, Wang JY. Risk factors for surgical site infection after elective resection of the colon and rectum: a single-center prospective study of 2,809 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2001;234:181-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Morris EJ, Taylor EF, Thomas JD, Quirke P, Finan PJ, Coleman MP, Rachet B, Forman D. Thirty-day postoperative mortality after colorectal cancer surgery in England. Gut. 2011;60:806-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Longo J, van Leeuwen JE, Elbaz M, Branchard E, Penn LZ. Statins as Anticancer Agents in the Era of Precision Medicine. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5791-5800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/