Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112780

Revised: September 25, 2025

Accepted: November 13, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 128 Days and 0.7 Hours

Postoperative ileus is a common complication after colorectal cancer surgery, affecting recovery quality and hospital stay duration. Early activity intervention, as an important component of enhanced recovery after surgery, requires sys

To comprehensively investigate the effects of early activity intervention on intestinal motility recovery and related indicators in patients after colorectal cancer surgery.

Using a retrospective comparative study design, 80 patients who underwent colorectal cancer surgery in our hospital from August 2023 to December 2024 were retrospectively analyzed and divided into experimental and control groups with 40 patients each based on the postoperative care protocols they received. The control group had received routine postoperative care, while the experimental group had additionally received a systematic early activity intervention program, including bed-based passive activities within 6 hours post-surgery, active bed exercises from 6-24 hours, bedside activities from 24-48 hours, and in-ward walking after 48 hours. Assessment indicators were retrospectively collected from medical records and included intestinal motility recovery, inflammatory stress response, postoperative complications, enteral nutrition tolerance, pain scores, nursing workload, patient psychological state, sleep quality, and nursing satisfaction.

The experimental group demonstrated significantly shorter time to first flatus (48.2 ± 10.6 hours vs 67.5 ± 12.3 hours, P < 0.001) and first defecation (72.4 ± 13.8 hours vs 94.6 ± 15.7 hours, P < 0.001); lower abdominal distension scores at 72 hours post-surgery (2.1 ± 0.6 vs 3.4 ± 0.8, P < 0.001); and reduced overall complication rates (7.5% vs 20.0%, P = 0.039). Inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α were significantly lower in the experimental group (P < 0.001). Pain scores at 72 hours post-surgery (1.8 ± 0.5 vs 3.2 ± 0.8, P < 0.001) and additional analgesic requests (2.3 ± 1.1 times vs 4.8 ± 1.6 times, P < 0.001) were markedly reduced. Good enteral nutrition tolerance was higher (90.0% vs 72.5%, P = 0.045), with earlier initiation of liquid diet (62.3 ± 9.6 hours vs 83.7 ± 12.4 hours, P < 0.001). Daily nursing time from postoperative day 3-7 (78.3 ± 15.6 minutes vs 96.2 ± 20.3 minutes, P < 0.001) and extra interventions for complications (1.2 ± 1.0 times/patient vs 2.8 ± 1.5 times/patient, P < 0.001) were reduced. Anxiety and depression scores were lower, sleep quality improved (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: 6.3 ± 1.4 vs 9.2 ± 2.1, P < 0.001), and nursing satisfaction was significantly higher (92.6 ± 5.8 vs 85.3 ± 7.2, P < 0.001).

Early activity intervention is a safe and effective non-pharmacological measure that not only significantly promotes intestinal motility recovery in patients after colorectal cancer surgery but also reduces inflammatory response and postoperative pain, improves enteral nutrition tolerance, decreases postoperative complication rates, reduces nursing workload, improves patient psychological state and sleep quality, increases nursing satisfaction, and shortens hospital stay. This comprehensive intervention, being easy to implement and cost-effective, is worthy of widespread application in clinical practice.

Core Tip: This retrospective study demonstrates that systematic early activity intervention following colorectal cancer surgery significantly accelerates intestinal motility recovery (19.3 hours faster first flatus) while reducing complications by 62.5%. The protocol progresses from passive bed exercises within 6 hours to walking after 48 hours post-surgery. Beyond physiological improvements, early mobilization enhanced pain management, improved enteral nutrition tolerance (90.0% vs 72.5%), and reduced nursing workload by 18.6%. The intervention also improved patient psychological well-being and sleep quality. As a non-pharmacological, cost-effective intervention easily implementable within existing enhanced recovery after surgery protocols, early activity intervention represents an evidence-based approach suitable for routine clinical adoption in colorectal cancer surgery recovery.

- Citation: Zhang XL, Lin AP, Lin TS, Huang YQ. Effects of early activity intervention on intestinal motility recovery in patients after colorectal cancer surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 112780

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/112780.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112780

Colorectal cancer is a malignant tumor with high incidence and mortality rates globally. In recent years, its incidence in China has shown a continuous upward trend, becoming a serious public health issue threatening national health. According to the latest epidemiological data, the annual new cases of colorectal cancer in China have exceeded 400000, showing a trend toward younger ages, placing heavy burdens on individuals, families, and society. Despite continuous innovation and improvement in treatment methods, surgical resection remains the most important and effective treatment for colorectal cancer, whether traditional open surgery or minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery, with the primary goal of radical tumor removal[1-4].

However, during postoperative recovery from colorectal cancer, intestinal dysfunction, especially postoperative ileus, is a common clinical problem that troubles patients. Postoperative ileus manifests as weakened or temporary cessation of intestinal motility, usually caused by multiple factors including surgical trauma, anesthetic effects, intraperitoneal manipulation, intraoperative bowel exposure, sympathetic nervous excitation, and postoperative bed rest. The main symptoms include abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, and difficulties with flatus and defecation, which not only increase subjective discomfort but also delay the initiation of oral feeding and enteral nutrition, affecting the overall postoperative recovery process. Severe intestinal dysfunction may lead to a series of complications such as intestinal obstruction, abdominal infection, wound dehiscence, and pulmonary infection, thereby prolonging hospital stay, increasing medical costs, and even affecting surgical prognosis and quality of life[5-7].

Traditional concepts of postoperative rehabilitation emphasize “adequate rest”, believing that postoperative activities should be minimized to protect surgical incisions and promote physical recovery. This concept has led many colorectal cancer patients to strictly limit activity and remain in bed for extended periods after surgery. However, prolonged bed rest not only fails to accelerate recovery but may bring multiple adverse consequences: First, immobility reduces abdominal muscle contraction and diaphragmatic movement, decreasing intra-abdominal pressure changes, further inhibiting intestinal motility; second, reduced activity slows blood circulation, increasing the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism; third, prolonged bed rest easily leads to decreased pulmonary ventilation function, increasing the risk of atelectasis and pulmonary infection; additionally, muscle atrophy and joint stiffness are aggravated by bed rest, delaying overall functional recovery[8-10].

In recent years, the concept of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) has gradually changed the traditional postoperative management model. ERAS is a multidisciplinary, multimodal, comprehensive perioperative management strategy aimed at reducing surgical stress response, lowering complication rates, and accelerating patient recovery. Its core elements include preoperative patient education, optimized preoperative preparation, minimally invasive surgical techniques, rational perioperative fluid management, multimodal analgesia, early enteral nutrition, and early activity intervention. In the ERAS concept, early activity intervention is considered a key element in promoting postoperative recovery, particularly important for intestinal motility recovery after colorectal cancer surgery[11-13].

The theoretical basis for early activity intervention involves multiple physiological mechanisms: Activity increases abdominal muscle contraction and diaphragmatic movement, enhances intra-abdominal pressure changes, and stimulates mechanical intestinal motility; appropriate activity promotes blood circulation, improves intestinal blood supply and oxygenation, and reduces the risk of intestinal mucosal ischemia-reperfusion injury; activity can inhibit excessive sympathetic nervous excitation, promote parasympathetic nervous function recovery, benefiting intestinal function regulation; furthermore, activity can reduce inflammatory response, lowering the inhibitory effects of inflammatory factors on intestinal smooth muscle and ganglionic cells. Through these mechanisms, activity jointly promotes intestinal motility recovery and improves gastrointestinal function[14-16].

Despite sufficient theoretical basis for early activity intervention, it still faces many challenges in clinical practice: On one hand, healthcare professionals and patients lack understanding of postoperative early activity intervention, with traditional bed rest concepts still deeply rooted; on the other hand, specific early activity intervention protocols lack uniform standards, including key parameters such as activity initiation timing, intensity, frequency, and duration lacking clear guidance; additionally, there is relatively insufficient systematic evaluation of the effects of early activity intervention on multidimensional recovery indicators in colorectal cancer patients after surgery, especially the lack of high-quality research data in Chinese patient populations[17,18].

In view of this, conducting systematic evaluations of the effects of early activity intervention on intestinal motility recovery in patients after colorectal cancer surgery has important clinical significance. This study aims to explore the effects of early activity intervention on intestinal motility recovery in patients after colorectal cancer surgery, and systematically evaluate its role in inflammatory response, postoperative pain, complication incidence, enteral nutrition tolerance, nursing workload, and patient satisfaction, providing scientific basis for formulating standardized, individualized early activity intervention protocols, promoting the in-depth application of ERAS concepts in perioperative management of colorectal cancer, and ultimately improving postoperative rehabilitation quality, shortening hospital stays, and enhancing medical efficiency and patient satisfaction.

This study conducted a retrospective comparative analysis, reviewing 80 patients who underwent colorectal cancer surgery at our hospital from August 2023 to December 2024. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Age 18-75 years; (2) Pathologically confirmed colorectal cancer having received elective surgical treatment; (3) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification I-III; (4) Documented normal cognitive function with ability to understand and comply with treatment requirements; and (5) Complete medical records available for analysis. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Combined severe cardiopulmonary dysfunction, hepatorenal dysfunction or other systemic diseases; (2) Pre-existing intestinal obstruction symptoms; (3) Intraoperative discovery of extensive tumor metastasis preventing radical surgery; (4) Severe complications during surgery or within 24 hours postoperatively; (5) Postoperative requirement for prolonged bed rest or restricted activity; (6) Mental illness patients or those unable to cooperate with intervention and assessment; (7) Participation in other clinical trials within the past month; and (8) Incomplete medical records or missing key data. After obtaining approval from the hospital ethics committee for retrospective data analysis, eligible patients were divided into experimental and control groups based on the postoperative care protocols they had received during their hospitalization, with 40 patients in each group. The experimental group consisted of patients who had received systematic early activity intervention programs, while the control group included patients who had received routine postoperative care.

The control group received routine postoperative care for colorectal cancer, including postoperative vital sign monitoring and recording, pain assessment and management, wound care, observation and care of drainage tubes and urinary catheters, intravenous fluid and medication administration, and conventional encouragement for appropriate activity when tolerable. The experimental group received a systematic early activity intervention program in addition to routine care: Passive activities in bed within 6 hours post-surgery (range of motion exercises for limbs, once every 2 hours, 10-15 minutes each time); active bed activities from 6-24 hours post-surgery (encouraging patients to turn in bed, raise legs, perform ankle pump exercises, etc., once every 2-3 hours, 15-20 minutes each time); bedside sitting, standing, and short-distance activities from 24-48 hours post-surgery (3-4 times daily, 20-30 minutes each time, gradually increasing activity based on tolerance); and in-ward walking after 48 hours post-surgery (4-5 times daily, 30 minutes each time, gradually extending walking distance and time). Throughout the activity intervention process, professional nursing staff provided accompaniment and guidance, closely monitored vital sign changes and subjective feelings, ensured activity safety, and adjusted activity intensity and duration according to patients’ specific conditions to avoid excessive fatigue.

The primary endpoint indicators in this study included time to first flatus (recording the time from surgery to first flatus, in hours) and time to first defecation (recording the time from surgery to first bowel movement, in hours). Secondary endpoint indicators included: Abdominal distension scores using Visual Analog Scale, 0-10 points, higher scores indicating greater abdominal distension, assessed at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours post-surgery; postoperative complication rates, including intestinal obstruction, abdominal infection, wound infection, pulmonary infection and other complications; nursing satisfaction, using a self-designed nursing satisfaction questionnaire covering professional skills, service attitude, health education and other dimensions, total score of 100 points, ≥ 90 points considered very satisfied, 80-89 points satisfied, 70-79 points average, < 70 points dissatisfied, with satisfaction rate calculated as (number of very satisfied + satisfied cases)/total cases × 100%; and postoperative hospital stay, recording days from surgery completion to discharge. All indicators were collected by trained nursing staff and research assistants, with an electronic database established for management to ensure data integrity and accuracy.

SPSS 25.0 statistical software was used for data analysis. Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD, with independent samples t-tests used for between-group comparisons; categorical data are reported as frequencies and percentages, analyzed using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Comparisons of general characteristics between the two groups including age, gender, body mass index, tumor location, tumor size, tumor-node-metastasis staging, surgical approach, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion, anesthesia method, ASA classification, and comorbidities showed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05), establishing comparability. The experimental group’s mean age was 61.5 ± 8.7 years vs 62.3 ± 9.1 years in the control group (t = 0.412, P = 0.682); male-to-female ratio was 22:18 in the experimental group and 24:16 in the control group (χ2 = 0.205, P = 0.651); body mass index was 23.4 ± 2.6 kg/m2 in the experimental group and 23.8 ± 2.8 kg/m2 in the control group (t = 0.678, P = 0.500); mean tumor diameter was 3.8 ± 1.4 cm in the experimental group and 4.1 ± 1.6 cm in the control group (t = 0.928, P = 0.356); tumor-node-metastasis staging showed stage I 12 cases (30.0%), stage II 16 cases (40.0%), stage III 12 cases (30.0%) in the experimental group, and 10 cases (25.0%), 18 cases (45.0%), 12 cases (30.0%) respectively in the control group (χ2 = 0.278, P = 0.870); colon-to-rectal cancer ratio was 17:23 in the experimental group and 19:21 in the control group (χ2 = 0.201, P = 0.654); open-to-laparoscopic surgery ratio was 15:25 in the experimental group and 16:24 in the control group (χ2 = 0.053, P = 0.818); operation time was 168.4 ± 32.7 minutes in the experimental group and 172.6 ± 35.2 minutes in the control group (t = 0.577, P = 0.566); intraoperative blood loss was 145.7 ± 52.3 mL in the experimental group and 152.1 ± 56.8 mL in the control group (t = 0.537, P = 0.593); intraoperative blood transfusion rate was 10.0% (4/40) in the experimental group and 12.5% (5/40) in the control group (χ2 = 0.125, P = 0.723); general-to-combined anesthesia ratio was 35:5 in the experimental group and 33:7 in the control group (χ2 = 0.417, P = 0.519); ASA classification I, II, III were 8, 24, 8 cases in the experimental group and 9, 22, 9 cases in the control group, respectively (χ2 = 0.223, P = 0.894); comorbidity proportion (hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, etc.) was 40.0% (16/40) in the experimental group and 42.5% (17/40) in the control group (χ2 = 0.053, P = 0.819, Table 1).

| Characteristic | Experimental group (n = 40) | Control group (n = 40) | Statistic | P value |

| Age (years) | 61.5 ± 8.7 | 62.3 ± 9.1 | t = 0.412 | 0.682 |

| Gender | χ2 = 0.205 | 0.651 | ||

| Male | 22 (55.0) | 24 (60.0) | ||

| Female | 18 (45.0) | 16 (40.0) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 2.6 | 23.8 ± 2.8 | t = 0.678 | 0.500 |

| Tumor location | χ2 = 0.201 | 0.654 | ||

| Colon | 17 (42.5) | 19 (47.5) | ||

| Rectum | 23 (57.5) | 21 (52.5) | ||

| Tumor diameter (cm) | 3.8 ± 1.4 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | t = 0.928 | 0.356 |

| TNM stage | χ2 = 0.278 | 0.870 | ||

| Stage I | 12 (30.0) | 10 (25.0) | ||

| Stage II | 16 (40.0) | 18 (45.0) | ||

| Stage III | 12 (30.0) | 12 (30.0) | ||

| Surgical approach | χ2 = 0.053 | 0.818 | ||

| Open | 15 (37.5) | 16 (40.0) | ||

| Laparoscopic | 25 (62.5) | 24 (60.0) | ||

| Operation time (minutes) | 168.4 ± 32.7 | 172.6 ± 35.2 | t = 0.577 | 0.566 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 145.7 ± 52.3 | 152.1 ± 56.8 | t = 0.537 | 0.593 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 4 (10.0) | 5 (12.5) | χ2 = 0.125 | 0.723 |

| Anesthesia method | χ2 = 0.417 | 0.519 | ||

| General anesthesia | 35 (87.5) | 33 (82.5) | ||

| Combined anesthesia | 5 (12.5) | 7 (17.5) | ||

| ASA classification | χ2 = 0.223 | 0.894 | ||

| Class I | 8 (20.0) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Class II | 24 (60.0) | 22 (55.0) | ||

| Class III | 8 (20.0) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Comorbidities | 16 (40.0) | 17 (42.5) | χ2 = 0.053 | 0.819 |

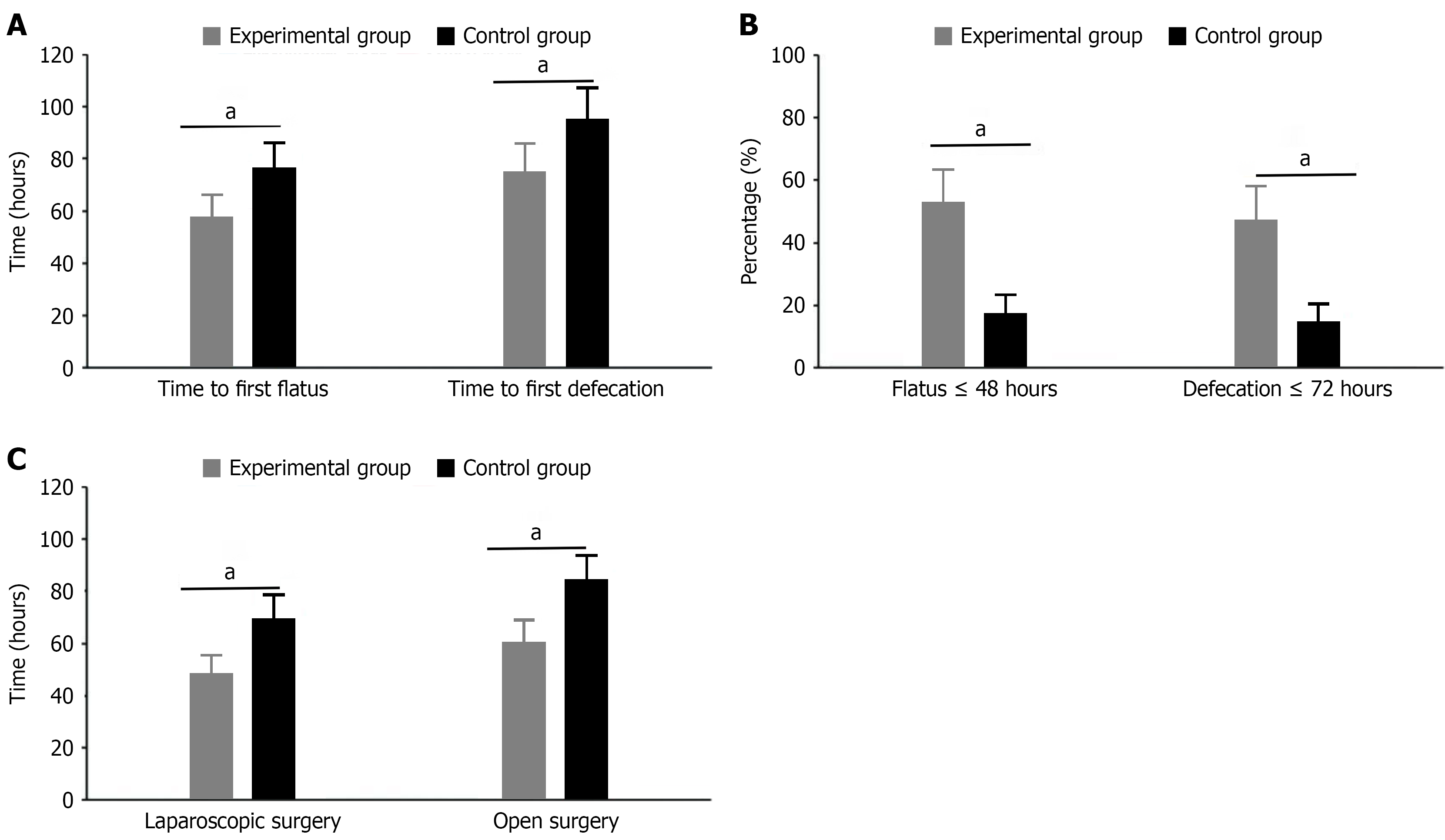

Time to first flatus and first defecation: The experimental group’s time to first flatus was 48.2 ± 10.6 hours, significantly shorter than the control group’s 67.5 ± 12.3 hours, showing statistical significance (t = 7.824, P < 0.001); patients with first flatus time ≤ 48 hours accounted for 52.5% (21/40) in the experimental group, while only 17.5% (7/40) in the control group (χ2 = 10.556, P = 0.001). The experimental group’s time to first defecation was 72.4 ± 13.8 hours, significantly earlier than the control group’s 94.6 ± 15.7 hours, showing statistical significance (t = 6.935, P < 0.001); patients with first defecation time ≤ 72 hours accounted for 47.5% (19/40) in the experimental group, while only 15.0% (6/40) in the control group (χ2 = 9.899, P = 0.002). Further subgroup analysis showed that in laparoscopic surgery patients, the experimental group’s time to first flatus was 44.3 ± 9.2 hours vs 63.7 ± 11.5 hours in the control group (t = 6.752, P < 0.001); in open surgery patients, the experimental group’s time to first flatus was 54.6 ± 10.8 hours vs 73.1 ± 12.7 hours in the control group (t = 4.328, P < 0.001), indicating that early activity intervention effectively promotes intestinal motility recovery regardless of surgical approach (Figure 1).

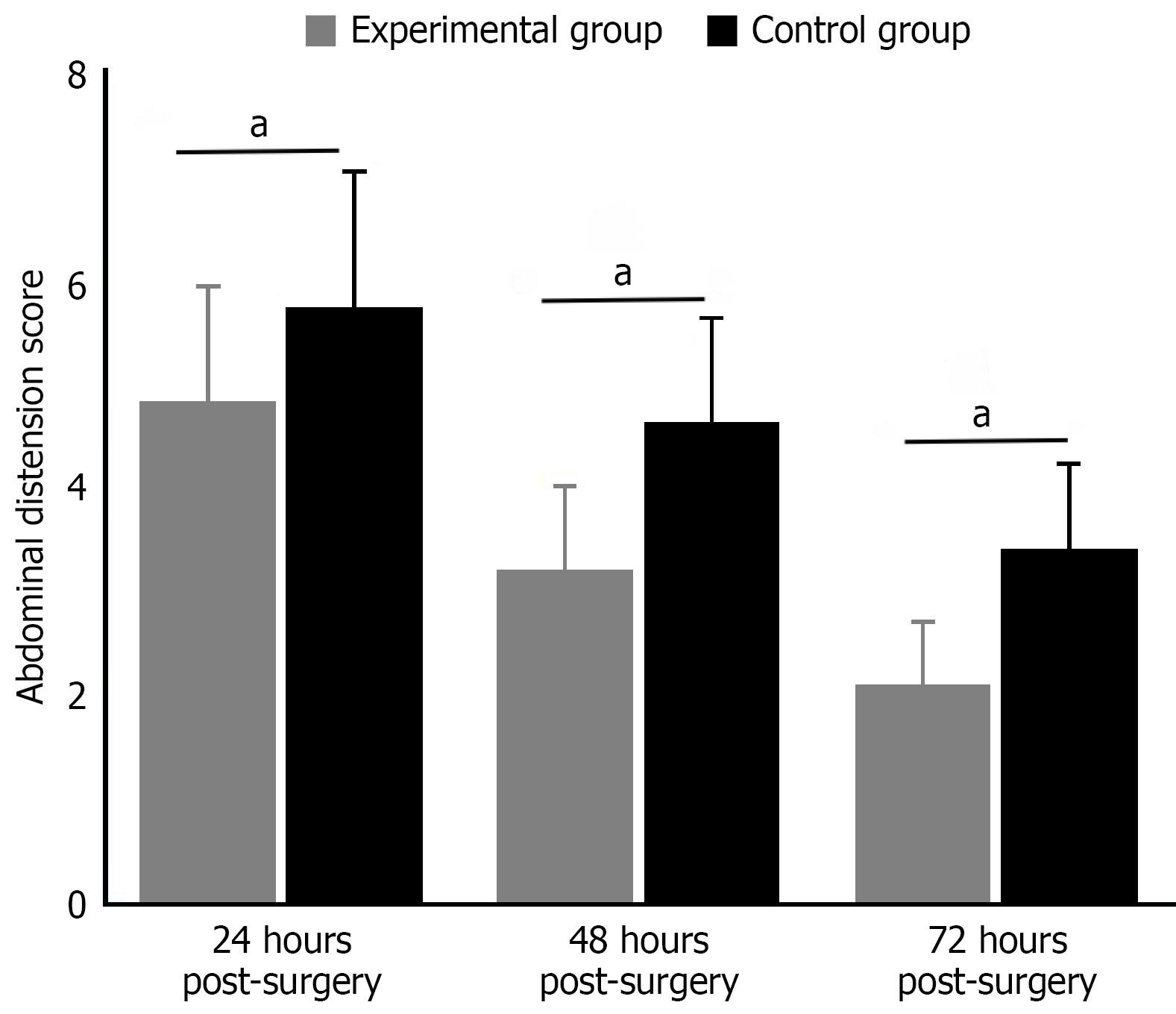

Comparison of abdominal distension scores: Comparison of abdominal distension scores at different postoperative time points showed consistently lower scores in the experimental group (P < 0.05). At 24 hours post-surgery, the experimental group’s abdominal distension score was 4.8 ± 1.1, significantly lower than the control group’s 5.7 ± 1.3 (t = 3.462, P = 0.001). This beneficial trend continued at 48 hours post-surgery, with the experimental group scoring 3.2 ± 0.8 and control group 4.6 ± 1.0 (t = 7.056, P < 0.001). By 72 hours post-surgery, the difference became more pronounced, with the experimental group reporting 2.1 ± 0.6 and control group 3.4 ± 0.8 (t = 8.467, P < 0.001). These results indicate that early activity intervention gradually alleviated abdominal distension symptoms in patients after colorectal cancer surgery, with effects becoming more significant over time (Figure 2).

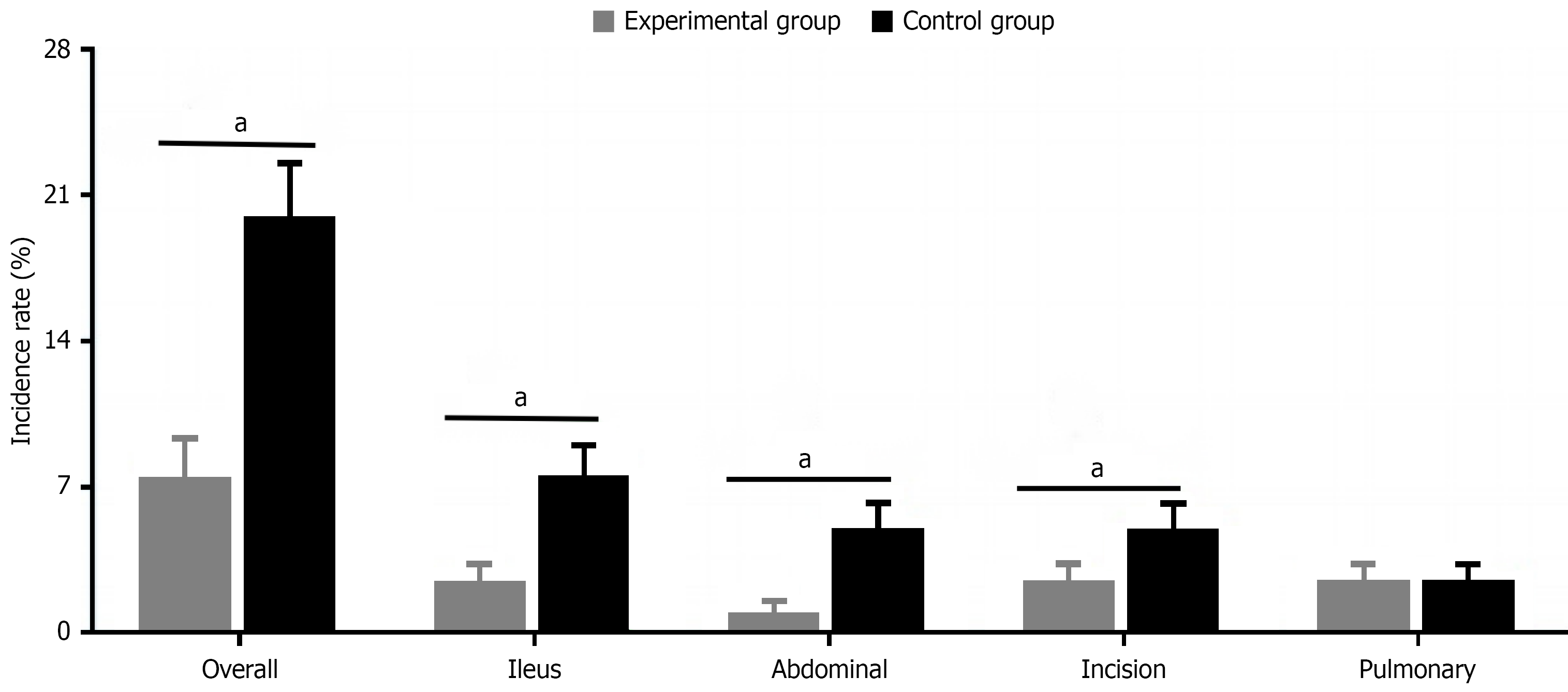

The experimental group’s overall postoperative complication rate was 7.5% (3/40), significantly lower than the control group’s 20.0% (8/40), showing statistical significance (χ2 = 4.267, P = 0.039). Specifically, the experimental group’s intestinal obstruction incidence was 2.5% (1/40) vs 7.5% (3/40) in the control group (P = 0.615); abdominal infection incidence was 0.0% (0/40) in the experimental group vs 5.0% (2/40) in the control group (P = 0.494); wound infection incidence was 2.5% (1/40) in the experimental group vs 5.0% (2/40) in the control group (P = 1.000); pulmonary infection incidence was 2.5% (1/40) in both groups (P = 1.000). Individual complication comparisons were analyzed using Fisher’s exact probability method. Although differences in specific types of complications did not reach statistical significance, the significant reduction in overall complication rate indicates that early activity intervention effectively improves postoperative safety and rehabilitation outcomes in colorectal cancer patients (Figure 3).

Comparison of postoperative pain scores showed that early activity intervention effectively relieved patients’ postoperative pain. At 24 hours post-surgery, the experimental group’s NRS pain score was 4.2 ± 0.9, significantly lower than the control group’s 5.1 ± 1.2 (t = 3.976, P = 0.002); at 48 hours post-surgery, the experimental group scored 3.0 ± 0.7 vs 4.3 ± 1.0 in the control group (t = 7.126, P < 0.001); at 72 hours post-surgery, the experimental group further decreased to 1.8 ± 0.5 while the control group was 3.2 ± 0.8 (t = 9.542, P < 0.001). Pain scores ≤ 3 were considered good pain control, with 82.5% (33/40) of the experimental group achieving good pain control at 48 hours post-surgery, significantly higher than the control group’s 45.0% (18/40) (χ2 = 11.882, P < 0.001). Additionally, the experimental group’s additional requests for analgesic medication were 2.3 ± 1.1 times, significantly fewer than the control group’s 4.8 ± 1.6 times (t = 8.475, P < 0.001); total analgesic medication use (calculated as morphine equivalent dose) was reduced by 28.6%; pain-related sleep disturbance incidence was 15.0% (6/40), lower than the control group’s 37.5% (15/40) (χ2 = 5.227, P = 0.022); impact of pain on daily activities scored 2.6 ± 0.7, lower than the control group’s 4.1 ± 1.2 (t = 7.138, P < 0.001); pain control satisfaction rate was 90.0% (36/40), higher than the control group’s 67.5% (27/40) (χ2 = 6.465, P = 0.011). These results suggest that early activity intervention, by promoting blood circulation, reducing muscle spasms, and releasing endogenous analgesic substances, formed a virtuous cycle: Appropriate activity reduced pain, pain relief promoted activity, thereby accelerating the rehabilitation process, reducing analgesic medication use, lowering medication-related adverse reactions, and improving patient comfort and satisfaction (Table 2).

| Indicator | Experimental group (n = 40) | Control group (n = 40) | Statistic | P value |

| NRS pain score (points) | ||||

| 24 hours after surgery | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | t = 3.976 | 0.002 |

| 48 hours after surgery | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | t = 7.126 | < 0.001 |

| 72 hours after surgery | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | t = 9.542 | < 0.001 |

| Good pain control | ||||

| Proportion with good pain control at 48 hours after surgery1 (%) | 33 (82.5) | 18 (45.0) | χ2 = 11.882 | < 0.001 |

| Analgesic medication use | ||||

| Additional requests for analgesic medication (times) | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | t = 8.475 | < 0.001 |

| Pain-related effects | ||||

| Incidence of pain-related sleep disturbance (%) | 6 (15.0) | 15 (37.5) | χ2 = 5.227 | 0.022 |

| Impact of pain on daily activities score (points) | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | t = 7.138 | < 0.001 |

| Pain control satisfaction rate (%) | 36 (90.0) | 27 (67.5) | χ2 = 6.465 | 0.011 |

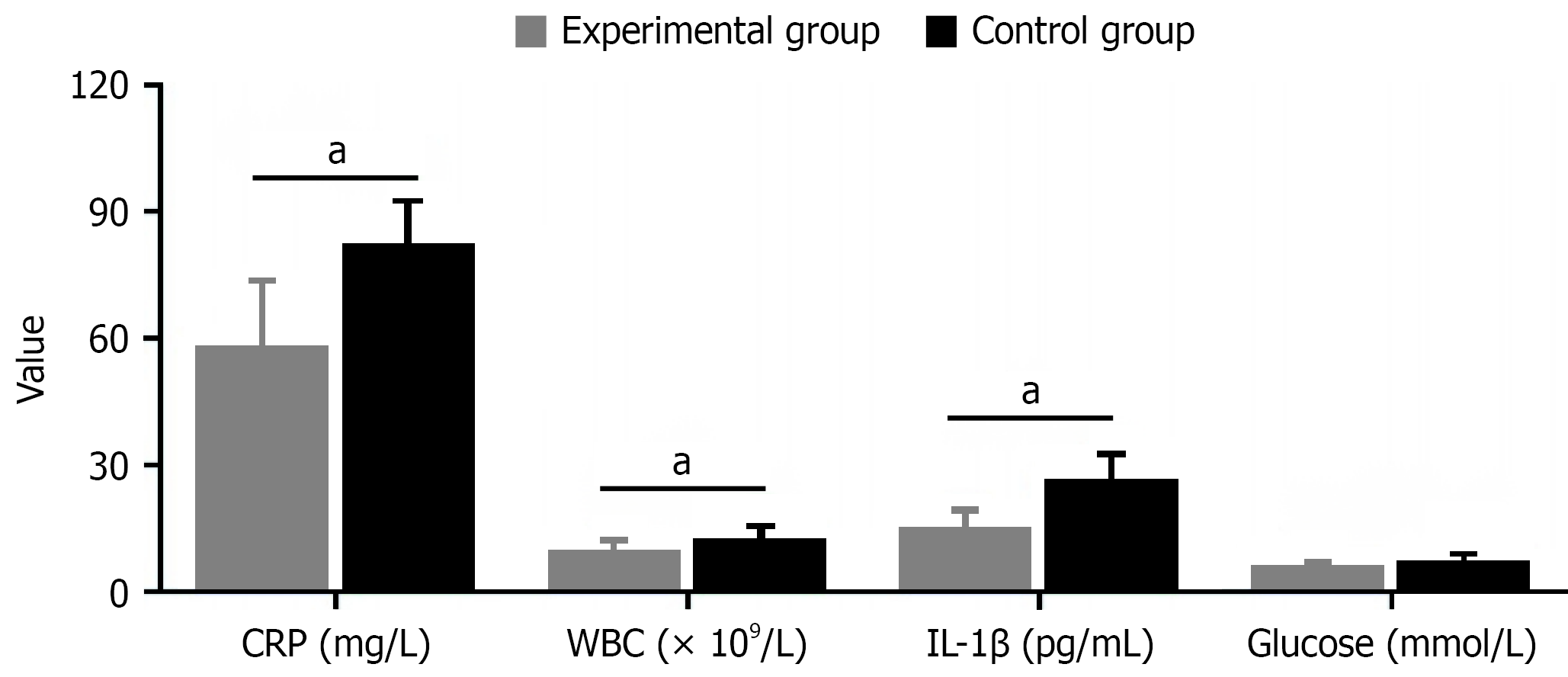

Comparison of postoperative inflammatory and stress response indicators showed significant differences between the two groups on postoperative day 3. The experimental group (early activity intervention group) had significantly lower levels than the control group across all indicators: C-reactive protein (58.2 ± 15.3 mg/L vs 82.7 ± 20.6 mg/L, reduced by 29.6%, t = 6.321, P < 0.001), white blood cell count [(9.8 ± 2.1) × 109/L vs (12.6 ± 3.4) × 109/L, reduced by 22.2%, t = 4.653, P < 0.001], interleukin-1β (15.2 ± 4.1 pg/mL vs 26.7 ± 5.8 pg/mL, reduced by 43.1%, t = 5.642, P < 0.001), blood glucose (6.2 ± 0.8 mmol/L vs 7.5 ± 1.3 mmol/L, reduced by 17.3%, t = 5.642, P < 0.001), interleukin-6 (42.3 ± 11.7 pg/mL vs 67.9 ± 18.2 pg/mL, reduced by 37.7%, t = 7.619, P < 0.001), tumor necrosis factor-α (18.6 ± 5.2 pg/mL vs 29.4 ± 7.1 pg/mL, reduced by 36.7%, t = 7.915, P < 0.001), procalcitonin (0.42 ± 0.13 ng/mL vs 0.76 ± 0.25 ng/mL, reduced by 44.7%, t = 7.824, P < 0.001), and serum amyloid A (63.5 ± 14.7 mg/L vs 92.8 ± 18.3 mg/L, reduced by 31.6%, t = 8.129, P < 0.001, Figure 4).

The comprehensive assessment of early activity intervention revealed significant improvements across multiple clinical domains. In terms of nutritional recovery, the experimental group demonstrated superior enteral nutrition tolerance, with 90.0% of patients achieving good tolerance compared to 72.5% in the control group (P = 0.045). The intervention group also showed accelerated nutritional milestones, including earlier initiation of liquid diet (62.3 ± 9.6 hours vs 83.7 ± 12.4 hours, P < 0.001) and faster progression to full enteral nutrition (4.3 ± 0.8 days vs 5.8 ± 1.2 days, P < 0.001). Nutritional status indicators further supported these findings, with higher serum albumin levels at postoperative day 7 (36.2 ± 3.5 g/L vs 32.8 ± 3.9 g/L, P < 0.001) and reduced weight loss at 14 days (3.2% ± 1.3% vs 5.4% ± 1.8%, P < 0.001).

From a healthcare efficiency perspective, early activity intervention substantially reduced nursing workload while improving care quality. Daily nursing time from postoperative days 3-7 decreased significantly (78.3 ± 15.6 minutes vs 96.2 ± 20.3 minutes, P < 0.001), alongside fewer extra interventions required for complications (1.2 ± 1.0 times per patient vs 2.8 ± 1.5 times per patient, P < 0.001). Healthcare providers reported higher professional achievement scores (87.6 ± 6.2 vs 79.4 ± 7.8, P < 0.001), while discharge preparation became more efficient, requiring less instruction time (22.4 ± 5.3 minutes vs 31.5 ± 7.2 minutes, P < 0.001).

The intervention’s impact on psychological wellbeing and sleep quality proved equally significant. Patients in the experimental group experienced lower anxiety scores (5.2 ± 1.8 vs 8.1 ± 2.4, P < 0.001) and reduced depression symptoms (4.8 ± 1.5 vs 7.6 ± 2.2, P < 0.001). Sleep quality improvements were evident through better Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores (6.3 ± 1.4 vs 9.2 ± 2.1, P < 0.001), longer nighttime sleep duration (6.5 ± 0.8 hours vs 5.2 ± 1.1 hours, P < 0.001), and enhanced sleep efficiency (78.2% ± 6.5% vs 65.4% ± 8.9%, P < 0.001). These multifaceted improvements culminated in significantly higher overall nursing satisfaction scores (92.6 ± 5.8 vs 85.3 ± 7.2, P < 0.001), indicating that the intervention benefits extended beyond clinical parameters to encompass patient experience and care quality (Table 3).

| Indicator | Experimental group (n = 40) | Control group (n = 40) | Statistic | P value |

| Nutrition & tolerance | ||||

| Good enteral nutrition tolerance (%) | 90.0 (36/40) | 72.5 (29/40) | χ2 = 4.021 | 0.045 |

| Time to first liquid diet (hours) | 62.3 ± 9.6 | 83.7 ± 12.4 | t = 8.732 | < 0.001 |

| Time to full enteral nutrition (days) | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 1.2 | t = 6.975 | < 0.001 |

| Target intake achievement within 7 days (%) | 85.0 (34/40) | 65.0 (26/40) | χ2 = 4.267 | 0.039 |

| Serum albumin on POD 7 (g/L) | 36.2 ± 3.5 | 32.8 ± 3.9 | t = 4.183 | < 0.001 |

| Weight loss at 14 days (%) | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 1.8 | t = 6.432 | < 0.001 |

| Nursing workload & efficiency | ||||

| Daily nursing time POD 3-7 (minutes) | 78.3 ± 15.6 | 96.2 ± 20.3 | t = 4.530 | < 0.001 |

| Extra interventions for complications (times/patient) | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.5 | t = 5.731 | < 0.001 |

| Discharge instruction time (minutes) | 22.4 ± 5.3 | 31.5 ± 7.2 | t = 6.620 | < 0.001 |

| Professional achievement score | 87.6 ± 6.2 | 79.4 ± 7.8 | t = 3.854 | < 0.001 |

| Psychological & sleep status | ||||

| HADS-A anxiety score | 5.2 ± 1.8 | 8.1 ± 2.4 | t = 6.320 | < 0.001 |

| HADS-D depression score | 4.8 ± 1.5 | 7.6 ± 2.2 | t = 7.125 | < 0.001 |

| PSQI global score | 6.3 ± 1.4 | 9.2 ± 2.1 | t = 7.536 | < 0.001 |

| Night-time sleep duration (hours) | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 1.1 | t = 6.284 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 78.2 ± 6.5 | 65.4 ± 8.9 | t = 7.764 | < 0.001 |

| Nursing satisfaction | ||||

| Overall satisfaction score | 92.6 ± 5.8 | 85.3 ± 7.2 | t = 5.119 | < 0.001 |

This study investigated the effects of early activity intervention on intestinal motility recovery in patients after colorectal cancer surgery, with results showing that this intervention program has significant clinical benefits in multiple aspects. Colorectal cancer, as a common gastrointestinal malignancy in China, has shown an increasing incidence trend in recent years, with surgical resection remaining the main treatment method. However, postoperative ileus is a common complication that not only worsens patient discomfort but may also delay the initiation of enteral nutrition support, affecting postoperative recovery[19-22].

Traditional concepts suggest that postoperative patients should rest in bed to promote incision healing, but this practice often leads to prolonged patient inactivity, further aggravating intestinal dysfunction. With the development of medical concepts, especially the promotion of ERAS, early activity as an important component has received increasing attention. Early activity can promote intestinal motility recovery through multiple mechanisms, including increasing intra-abdominal pressure, promoting blood circulation, stimulating the autonomic nervous system, and more. Addi

Postoperative intestinal function recovery is an important indicator for evaluating surgical success. Intestinal motility is affected by multiple factors, including degree of surgical trauma, anesthetic drugs, intraoperative bowel manipulation, and postoperative activity level. Surgery itself causes local intestinal inflammatory response, and anesthetic drugs inhibit the central and peripheral nervous systems, collectively leading to temporary postoperative intestinal motility reduction or cessation. At this time, early appropriate activity can help intestinal function recover more quickly by counteracting these adverse factors[27-30].

Postoperative pain management is also a key factor affecting patients’ willingness to engage in activity. Traditional concepts believe that activity may aggravate pain, but this study confirms that reasonably implemented early activity intervention can actually improve pain control. This may be because appropriate activity promotes blood circulation, reduces muscle spasms, and potentially enhances the release of endogenous analgesic substances, though these hypothesized mechanisms require further validation through direct biochemical measurements. Meanwhile, activity and pain relief form a virtuous cycle: Appropriate activity reduces pain, pain relief promotes activity, thereby accelerating the overall rehabilitation process[31-35].

Postoperative inflammatory response is another important factor affecting intestinal motility recovery. Surgical trauma induces systemic inflammatory response, leading to the release of various inflammatory factors that can inhibit intestinal smooth muscle contraction and nerve conduction. In this study, postoperative inflammatory indicators in the early activity intervention group were significantly lower than in the control group, reflecting the positive role of activity in regulating immune function and reducing inflammatory response[36,37].

In our study results, early activity intervention significantly shortened patients’ time to first flatus (48.2 ± 10.6 hours vs 67.5 ± 12.3 hours) and first defecation (72.4 ± 13.8 hours vs 94.6 ± 15.7 hours), and reduced abdominal distension scores (2.1 ± 0.6 vs 3.4 ± 0.8). The experimental group’s overall postoperative complication rate was significantly reduced (7.5% vs 20.0%), collectively confirming the positive effects of early activity intervention on promoting gastrointestinal function recovery. Furthermore, hospital stay duration was significantly shortened in the experimental group (6.2 ± 1.4 days vs 8.1 ± 1.7 days, P < 0.001), demonstrating the practical clinical benefits of this intervention.

Notably, early activity intervention not only improved patients’ physiological indicators but also positively impacted psychological state. The intervention group’s anxiety and depression scores were significantly lower than the control group, and sleep quality indicators were also markedly improved. This suggests that early activity may improve psychological state by enhancing patients’ sense of participation and control over the rehabilitation process, forming a virtuous cycle of physical and psychological rehabilitation.

Regarding nursing work, although early activity intervention initially requires more time and effort from nursing staff to guide patients, with reduced patient complications and accelerated rehabilitation, it actually lowered overall nursing workload. The experimental group’s average daily nursing time was significantly shortened (78.3 ± 15.6 minutes vs 96.2 ± 20.3 minutes), and patient nursing satisfaction was significantly increased (92.6 ± 5.8 vs 85.3 ± 7.2), fully demonstrating that this intervention measure is not only beneficial for patients but also valuable for optimizing nursing workflow, improving nursing quality and efficiency.

Improved enteral nutrition tolerance is another important finding in this study. The experimental group’s good enteral nutrition tolerance rate (90.0% vs 72.5%) and related indicators were significantly better than the control group, indicating that early activity helps accelerate intestinal motility recovery, improve nutritional support effectiveness, and provide necessary support for postoperative tissue repair and functional recovery. While our study demonstrates significant short-term benefits of early activity intervention, we acknowledge that evaluation of long-term recovery metrics such as functional status, quality of life, and oncological outcomes would provide additional valuable insights and represents an important direction for future research.

In conclusion, our study results comprehensively confirm the positive impact of early activity intervention on multiple rehabilitation indicators in patients after colorectal cancer surgery, not only promoting intestinal motility recovery but also improving inflammatory response, pain control, psychological state, sleep quality, nursing efficiency, and patient satisfaction.

| 1. | Baidoun F, Elshiwy K, Elkeraie Y, Merjaneh Z, Khoudari G, Sarmini MT, Gad M, Al-Husseini M, Saad A. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Recent Trends and Impact on Outcomes. Curr Drug Targets. 2021;22:998-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:669-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 1751] [Article Influence: 350.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Eng C, Jácome AA, Agarwal R, Hayat MH, Byndloss MX, Holowatyj AN, Bailey C, Lieu CH. A comprehensive framework for early-onset colorectal cancer research. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:e116-e128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li J, Ma X, Chakravarti D, Shalapour S, DePinho RA. Genetic and biological hallmarks of colorectal cancer. Genes Dev. 2021;35:787-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 77.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 5. | Alhayyan AM, McSorley ST, Kearns RJ, Horgan PG, Roxburgh CSD, McMillan DC. The effect of anesthesia on the magnitude of the postoperative systemic inflammatory response in patients undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer in the context of an enhanced recovery pathway: A prospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e23997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Carli F, Bousquet-Dion G, Awasthi R, Elsherbini N, Liberman S, Boutros M, Stein B, Charlebois P, Ghitulescu G, Morin N, Jagoe T, Scheede-Bergdahl C, Minnella EM, Fiore JF Jr. Effect of Multimodal Prehabilitation vs Postoperative Rehabilitation on 30-Day Postoperative Complications for Frail Patients Undergoing Resection of Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:233-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 66.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cuijpers ACM, Lubbers T, van Rens HA, Smit-Fun V, Gielen C, Reynders K, Kimman ML, Stassen LPS. The patient perspective on the preoperative colorectal cancer care pathway and preparedness for surgery and postoperative recovery-a qualitative interview study. J Surg Oncol. 2022;126:544-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fabulas F, Paisant P, Dinomais M, Mucci S, Casa C, Le Naoures P, Hamel JF, Perrot J, Venara A. Pre-habilitation before colorectal cancer surgery could improve postoperative gastrointestinal function recovery: a case-matched study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:1595-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hasselager RP, Hallas J, Gögenur I. Epidural analgesia and postoperative complications in colorectal cancer surgery. An observational registry-based study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2022;66:869-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jaloun HE, Lee IK, Kim MK, Sung NY, Turkistani SAA, Park SM, Won DY, Hong SH, Kye BH, Lee YS, Jeon HM. Influence of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol on Postoperative Inflammation and Short-term Postoperative Surgical Outcomes After Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Ann Coloproctol. 2020;36:264-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lambert JE, Hayes LD, Keegan TJ, Subar DA, Gaffney CJ. The Impact of Prehabilitation on Patient Outcomes in Hepatobiliary, Colorectal, and Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery: A PRISMA-Accordant Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;274:70-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu X, Wang Y, Fu Z. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery on postoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in patients with colorectal cancer. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520925941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu Y, He W, Yang J, He Y, Wang Z, Li K. The effects of preoperative intestinal dysbacteriosis on postoperative recovery in colorectal cancer surgery: a prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lo PS, Lin YP, Hsu HH, Chang SC, Yang SP, Huang WC, Wang TJ. Health self-management experiences of colorectal cancer patients in postoperative recovery: A qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;51:101906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen X, Chen B. Correlation study of perioperative nutritional support and postoperative complication rates in colon cancer patients. Curr Probl Surg. 2025;66:101753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Willis F, Amati AL, Reichert M, Hecker A, Vilz TO, Kalff JC, Willis S, Kröplin MA. Current Evidence in Robotic Colorectal Surgery. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17:2503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Molenaar CJ, van Rooijen SJ, Fokkenrood HJ, Roumen RM, Janssen L, Slooter GD. Prehabilitation versus no prehabilitation to improve functional capacity, reduce postoperative complications and improve quality of life in colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamauchi S, Matsuyama T, Tokunaga M, Kinugasa Y. Minimally Invasive Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. JMA J. 2021;4:17-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yanagisawa T, Tatematsu N, Horiuchi M, Migitaka S, Yasuda S, Itatsu K, Kubota T, Sugiura H. Preoperative physical activity predicts postoperative functional recovery in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44:5557-5562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang SP, Wang TJ, Huang CC, Chang SC, Liang SY, Yu CH. Influence of albumin and physical activity on postoperative recovery in patients with colorectal cancer: An observational study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;54:102027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Co EL, Hameed M, Sebastian SA, Garg T, Sudan S, Bheemisetty N, Mohan B. Narrative Review of Probiotic Use on the Recovery of Postoperative Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Curr Nutr Rep. 2023;12:635-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Firut A, Margaritescu DN, Turcu-Stiolica A, Bica M, Rotaru I, Patrascu AM, Radu RI, Marinescu D, Patrascu S, Streba CT, Surlin V. Preoperative Immunocyte-Derived Ratios Predict Postoperative Recovery of Gastrointestinal Motility after Colorectal Cancer Surgery. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Han H, Wan R, Chen J, Fan X, Zhang L. Effects of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol on the postoperative stress state and short-term complications in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2024;7:e1979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang L, Zhang T, Wang K, Chang B, Fu D, Chen X. Postoperative Multimodal Analgesia Strategy for Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in Elderly Colorectal Cancer Patients. Pain Ther. 2024;13:745-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Koutoukidis DA, Jebb SA, Foster C, Wheatstone P, Horne A, Hill TM, Taylor A, Realpe A, Achana F, Buczacki SJA. CARE: Protocol of a randomised trial evaluating the feasibility of preoperative intentional weight loss to support postoperative recovery in patients with excess weight and colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2023;25:1910-1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Min J, An KY, Park H, Cho W, Jung HJ, Chu SH, Cho M, Yang SY, Jeon JY, Kim NK. Postoperative inpatient exercise facilitates recovery after laparoscopic surgery in colorectal cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Molenaar CJL, Minnella EM, Coca-Martinez M, Ten Cate DWG, Regis M, Awasthi R, Martínez-Palli G, López-Baamonde M, Sebio-Garcia R, Feo CV, van Rooijen SJ, Schreinemakers JMJ, Bojesen RD, Gögenur I, van den Heuvel ER, Carli F, Slooter GD; PREHAB Study Group. Effect of Multimodal Prehabilitation on Reducing Postoperative Complications and Enhancing Functional Capacity Following Colorectal Cancer Surgery: The PREHAB Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:572-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 103.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Onerup A, Li Y, Afshari K, Angenete E, de la Croix H, Ehrencrona C, Wedin A, Haglind E. Long-term results of a short-term home-based pre- and postoperative exercise intervention on physical recovery after colorectal cancer surgery (PHYSSURG-C): a randomized clinical trial. Colorectal Dis. 2024;26:545-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Park JS, Lee SM, Choi GS, Park SY, Kim HJ, Song SH, Min BS, Kim NK, Kim SH, Lee KY. Comparison of Laparoscopic Versus Robot-Assisted Surgery for Rectal Cancers: The COLRAR Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2023;278:31-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ten Cate DWG, Molenaar CJL, Garcia RS, Bojesen RD, Tahasildar BLR, Jansen L, López-Baamonde M, Feo CV, Martínez-Palli G, Gögenur I, Carli F, Slooter GD; PREHAB study group. Multimodal prehabilitation in elective oncological colorectal surgery enhances postoperative functional recovery: A secondary analysis of the PREHAB randomized clinical trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2024;50:108270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tsai PL, Chen JS, Lin CH, Hsu TC, Lin YW, Chen MJ. Abdominal wound length influences the postoperative serum level of interleukin-6 and recovery of flatus passage among patients with colorectal cancer. Front Surg. 2024;11:1400264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Urakawa S, Shingai T, Kato J, Kidogami S, Fukata T, Nishida H, Takemoto H, Ohigashi H, Fukuzaki T. Safety and feasibility of pain management using high-dose oral acetaminophen for enhanced recovery after colorectal cancer surgery. 2024 Preprint. Available from: researchsquare:rs-3941431/v1. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Wiesenberger R, Müller J, Kaufmann M, Weiß C, Ghezel-Ahmadi D, Hardt J, Reissfelder C, Herrle F. Feasibility and usefulness of postoperative mobilization goals in the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS(®)) clinical pathway for elective colorectal surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Willner A, Teske C, Hackert T, Welsch T. Effects of early postoperative mobilization following gastrointestinal surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJS Open. 2023;7:zrad102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yang F, Yuan Y, Liu W, Tang C, He F, Chen D, Xiong J, Huang G, Qian K. Effect of prehabilitation exercises on postoperative frailty in patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1411353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Soria-Utrilla V, Sánchez-Torralvo FJ, Palmas-Candia FX, Fernández-Jiménez R, Mucarzel-Suarez-Arana F, Guirado-Peláez P, Olveira G, García-Almeida JM, Burgos-Peláez R. AI-Assisted Body Composition Assessment Using CT Imaging in Colorectal Cancer Patients: Predictive Capacity for Sarcopenia and Malnutrition Diagnosis. Nutrients. 2024;16:1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhang J, Hu Y, Deng H, Huang Z, Huang J, Shen Q. Effect of Preoperative Lifestyle Management and Prehabilitation on Postoperative Capability of Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2024;23:15347354241235590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/