Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112685

Revised: September 24, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 144 Days and 18.3 Hours

Pediatric short bowel syndrome (SBS) poses management challenges, and teduglutide is a potential therapy. However, comprehensive data on its pediatric safety are lacking.

To evaluate the impact of teduglutide on infection and gastrointestinal adverse events in pediatric SBS patients via systematic review and meta-analysis.

Following PRISMA 2009 guidelines and PROSPERO registration, we searched PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (pediatric SBS patients ≤ 18 years; teduglutide vs placebo/standard care). Two reviewers screened studies, extracted data, and assessed bias (ROB2). Meta-analyses used RevMan 5.4 (Mantel-Haenszel method, random-effects if I2 ≠ 0). Trial sequential analysis and GRADE were applied.

Three RCTs involving 115 pediatric patients were included. Pooled analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the teduglutide and con

Teduglutide does not increase infection or gastrointestinal adverse event risk in pediatric SBS, but small sample sizes limit conclusions. Larger studies are needed.

Core Tip: This study evaluates the safety of teduglutide in pediatric short bowel syndrome via systematic review and trial sequential analysis. Three randomized controlled trials (n = 115) show no significant increase in infections or gastrointestinal adverse events, but small sample sizes limit conclusions. Larger, long-term studies are needed.

- Citation: Jiao P, Zhang ZJ, Jiang Y, Zhou J, Deng KH, Zhu WX, Zhao XY, Guo ZK. Impact of teduglutide on pediatric short bowel syndrome: A systematic review and trial sequential meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 112685

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/112685.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112685

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is a clinical syndrome characterized by severe insufficiency of small intestinal absorption area due to extensive intestinal resection, congenital intestinal defects, or functional disorders[1,2]. In pediatric populations, SBS primarily arises secondary to conditions such as necrotic enterocolitis, intestinal torsion, or congenital intestinal atresia, and is the most common cause of intestinal failure in children[3,4]. Patients with SBS require long-term reliance on parenteral nutrition (PN) due to impaired nutrient absorption, which not only significantly impacts growth and development as well as quality of life but also increases the risk of life-threatening complications, including catheter-related bloodstream infections, liver damage, and metabolic bone disease[5-7]. Despite recent advancements in PN management techniques, the burden of complications associated with long-term PN remains high. Therefore, promoting intestinal adaptive mechanisms to reduce PN dependence has become a key objective for improving patient outcomes.

Teduglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) analogue, theoretically promotes structural and functional adaptation of the remaining intestine by enhancing proliferation of intestinal crypt cells, inhibiting apoptosis, increasing villus height, and improving intestinal blood flow. It is used for the treatment of adult SBS, and its efficacy in reducing PN requirements has been confirmed by multiple studies[8-10]. However, children and adults exhibit significant differences in intestinal development, metabolic characteristics, and disease profiles: Children are in a rapid growth phase with higher nutritional requirements, and a higher proportion of congenital SBS, which may result in different intestinal adaptive potential compared to adults. Therefore, conclusions from adult studies cannot be directly extrapolated to the pediatric population. Pediatric patients exhibit distinct intestinal maturation trajectories (e.g., ongoing villus and crypt development in infants) and higher nutrient requirements, making their response to teduglutide potentially different from adults. While adult studies confirm teduglutide’s efficacy in reducing PN dependence, pediatric safety data remain fragmented-focused primarily on short-term outcomes without comprehensive assessment of long-term risks (e.g., organ-specific effects or growth impacts). This gap hinders evidence-based clinical use of teduglutide in children with SBS.

Currently, research on teduglutide for pediatric SBS remains in its preliminary stages. While some single-arm studies and small clinical trials have reported its safety profile and potential to reduce PN requirements, the evidence is significantly limited[5,6,8,9]. First, the sample sizes of existing studies are generally small, resulting in insufficient statistical power; Second, there is significant heterogeneity in outcome measures, and there is no unified core evaluation system; more importantly, key safety issues-particularly the risk of infectious complications (such as catheter-related infections, respiratory infections) and gastrointestinal adverse events (such as vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea)-have not been adequately validated in high-quality controlled studies. These uncertainties severely limit the standardized application of teduglutide in pediatric clinical practice. Additionally, there are currently no trial sequential analysis (TSA) for this population, and traditional meta-analyses may produce false-positive conclusions when sample sizes are insufficient. Therefore, this study will be the first to combine TSA methods to quantify evidence stability and estimate the required information size (RIS), providing a basis for future study design.

We designed and conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines[11]. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO.

Following the PICOS method, the inclusion criteria were as follows: P (participants): Pediatric patients aged ≤ 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of SBS; I (intervention): Patients in the experimental group received teduglutide as intervention; C (comparison): Patients in the control group only received placebo or regular treatments; O (outcomes): Primary outcomes: Incidence of infection events; secondary outcomes: Incidence of upper respiratory tract infection, incidence of catheter site infection, incidence of vomiting, incidence of abdominal pain, incidence of nausea, incidence of diarrhea, incidence of abdominal distension; S (study design): Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Non-human studies (animal experiments), crossover studies, non-randomized methodologies, conference materials without peer-reviewed full texts, and published in languages other than English will be excluded from this systematic review and meta-analysis.

To ensure accuracy and completeness, two reviewers independently performed a comprehensive literature search across three databases: PubMed, Web of Science, and EMBASE. The search period spanned from database inception to May 2024, with language restricted to English. Key search terms and logical combinations were: ["Teduglutide"(MeSH Terms) OR "teduglutide"(Title/Abstract)] AND ["short bowel syndrome"(MeSH Terms) OR "short bowel syndrome"(Title/Abstract)] AND ["pediatrics"(MeSH Terms) OR "child"(Title/Abstract) OR "adolescent"(Title/Abstract)] AND ["randomized controlled trial"(MeSH Terms) OR "RCT"(Title/Abstract)]. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included for analysis. The complete search strategy is detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

To ensure data integrity, two reviewers independently conducted literature screening and data extraction in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions within the investigative team. Data extraction was performed using a standardized Microsoft Excel form. The form captured study design, baseline patient characteristics, and incidence data for all outcomes: Infection events, upper respiratory tract infection, catheter site infection, vomiting, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal distension. Studies with incomplete or missing outcome data were excluded to maintain the reliability and accuracy of pooled analyses.

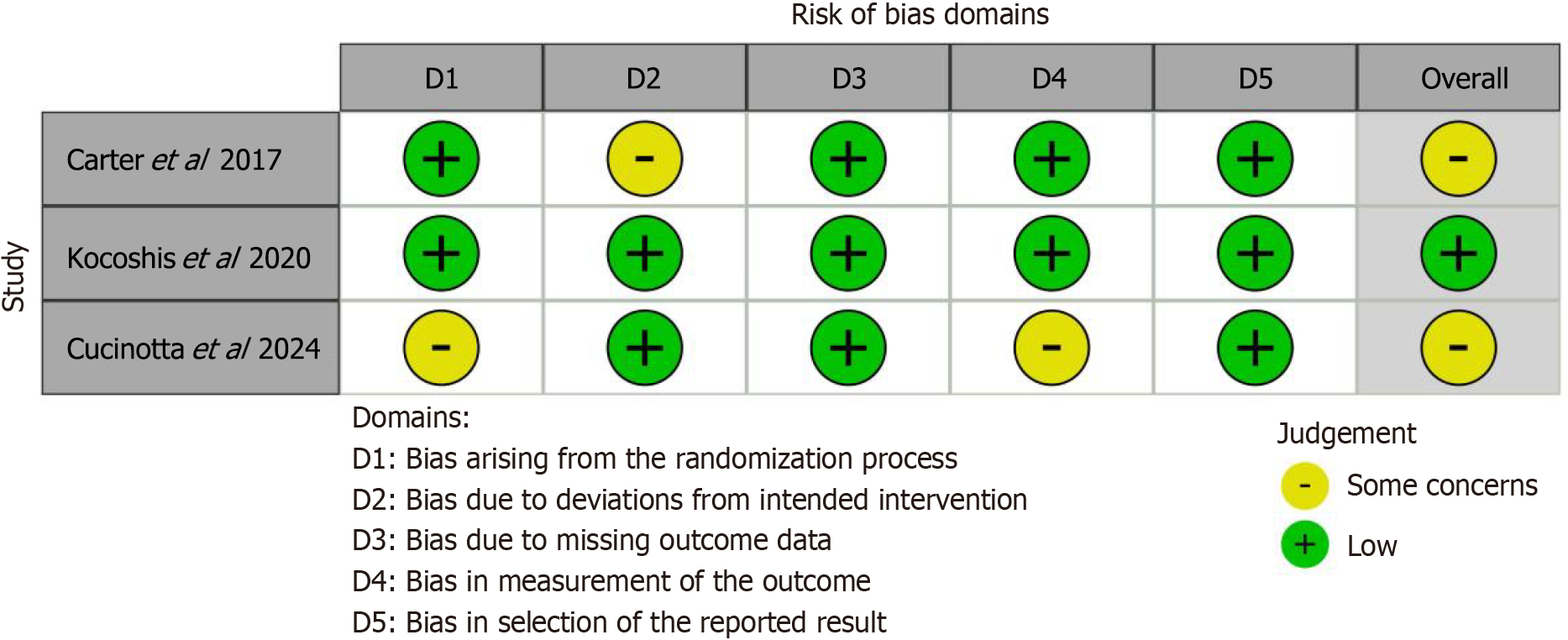

To ensure methodological rigor, two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias in included RCTs using the ROB 2. The evaluation covered five domains: Bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in outcome measurements, and bias in selection of the reported result. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions within the research team.

Data synthesis was performed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s RevMan software (version 5.4). For dichotomous outcomes, pooled RR with 95%CI were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method. For continuous outcomes, MD with 95%CI were pooled via the inverse variance method. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed), with P < 0.05 considered significant. Random-effect models are applied when statistical heterogeneity is present (I2 ≠ 0), while a fixed-effects model is used when I2 = 0. Publication bias is assessed only when the number of included studies exceeds 10, as a small number of studies could compromise the robustness of the tests.

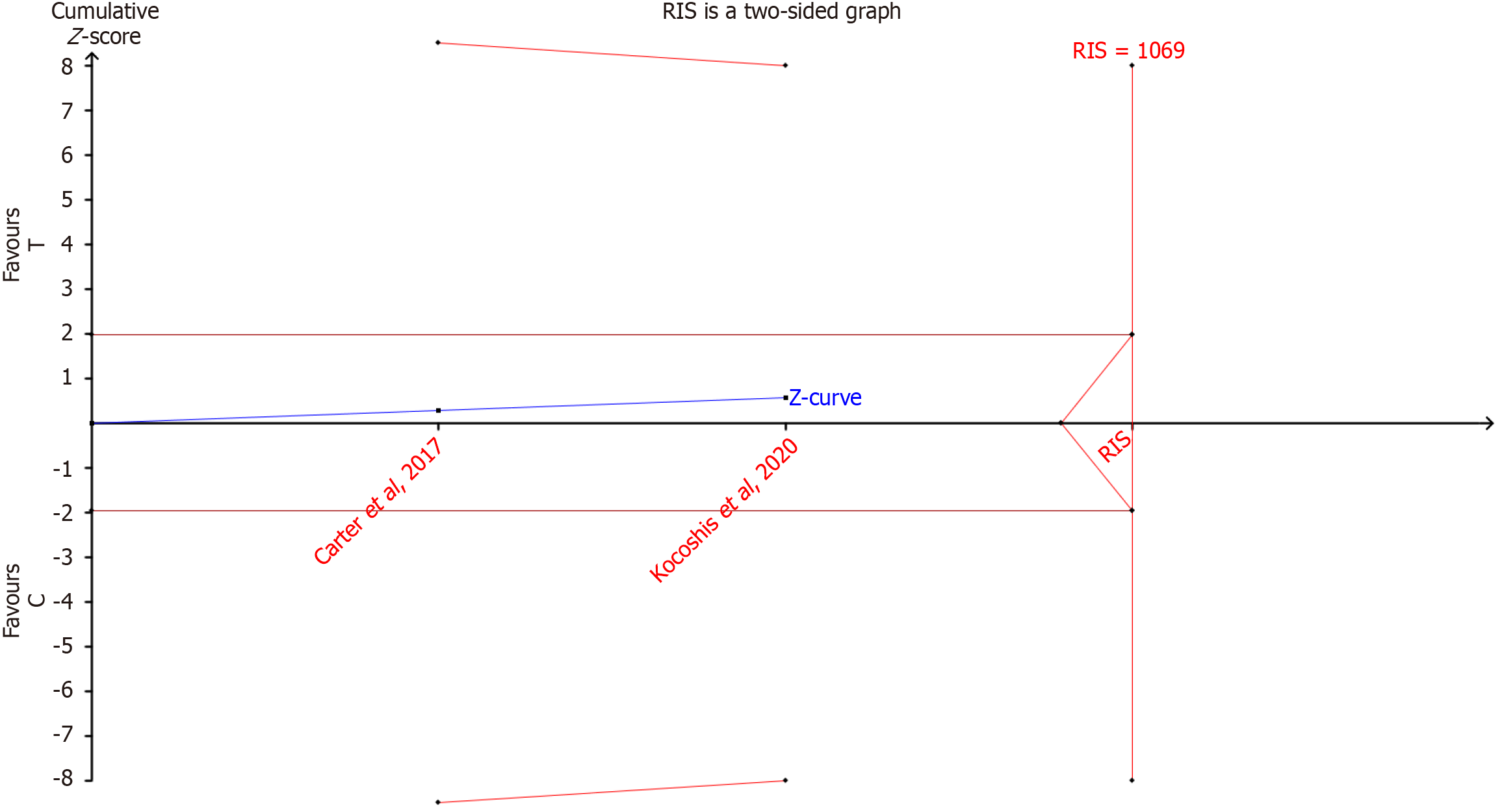

Conventional meta-analyses may yield false-positive results due to random error, particularly when sample sizes are insufficient or repeated testing is performed. To account for these limitations and estimate the RIS, we conducted TSA for primary outcomes using TSA software (version 0.9.5.10 Beta). Type 1 error and power were set at 5% and 80%, respectively.

The certainty of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE approach through the official GRADEpro online tool[12]. This systematic assessment examined five critical dimensions: Study design, risk of bias, imprecision, indirectness, and inconsistency. Bases on these criteria, the certainty of evidence for each outcome was classified into one of four levels: High, moderate, low, or very low.

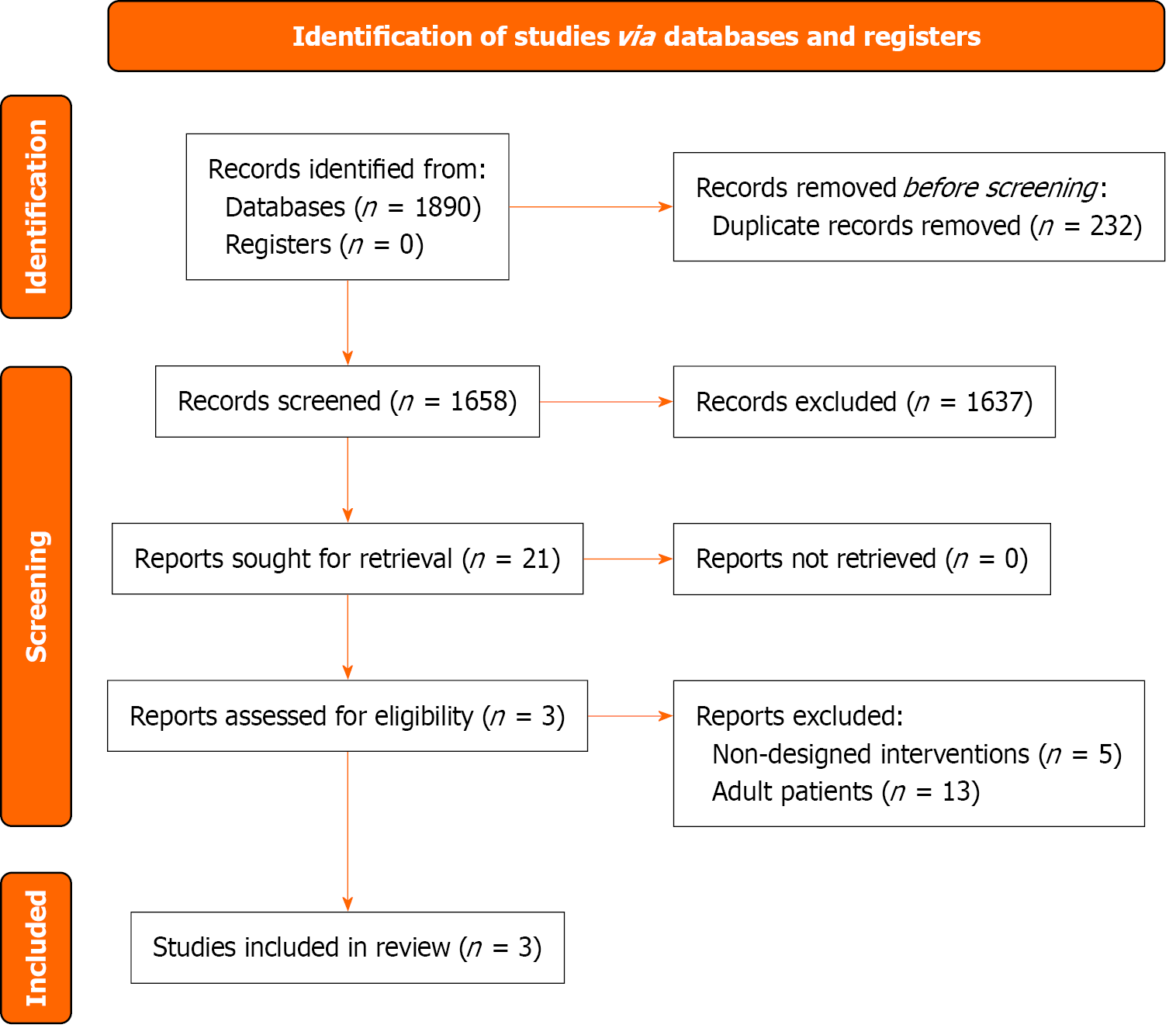

Based on the retrieval strategy, 1890 records were retrieved. After processes of removing duplicates, screening titles and abstracts, 21 studies were retained for full-text screening. Finally, Three RCTs involving 115 pediatric patients with a confirmed diagnosis of SBS were included[13-15]. The basic characteristics of the included trials are presented in Supplementary Table 2. A flowchart of the screening process and results is shown in Figure 1.

Based on the risk of bias assessment of included studies, the overall methodological quality was moderate. The plot of the risk of bias is presented in Figure 2.

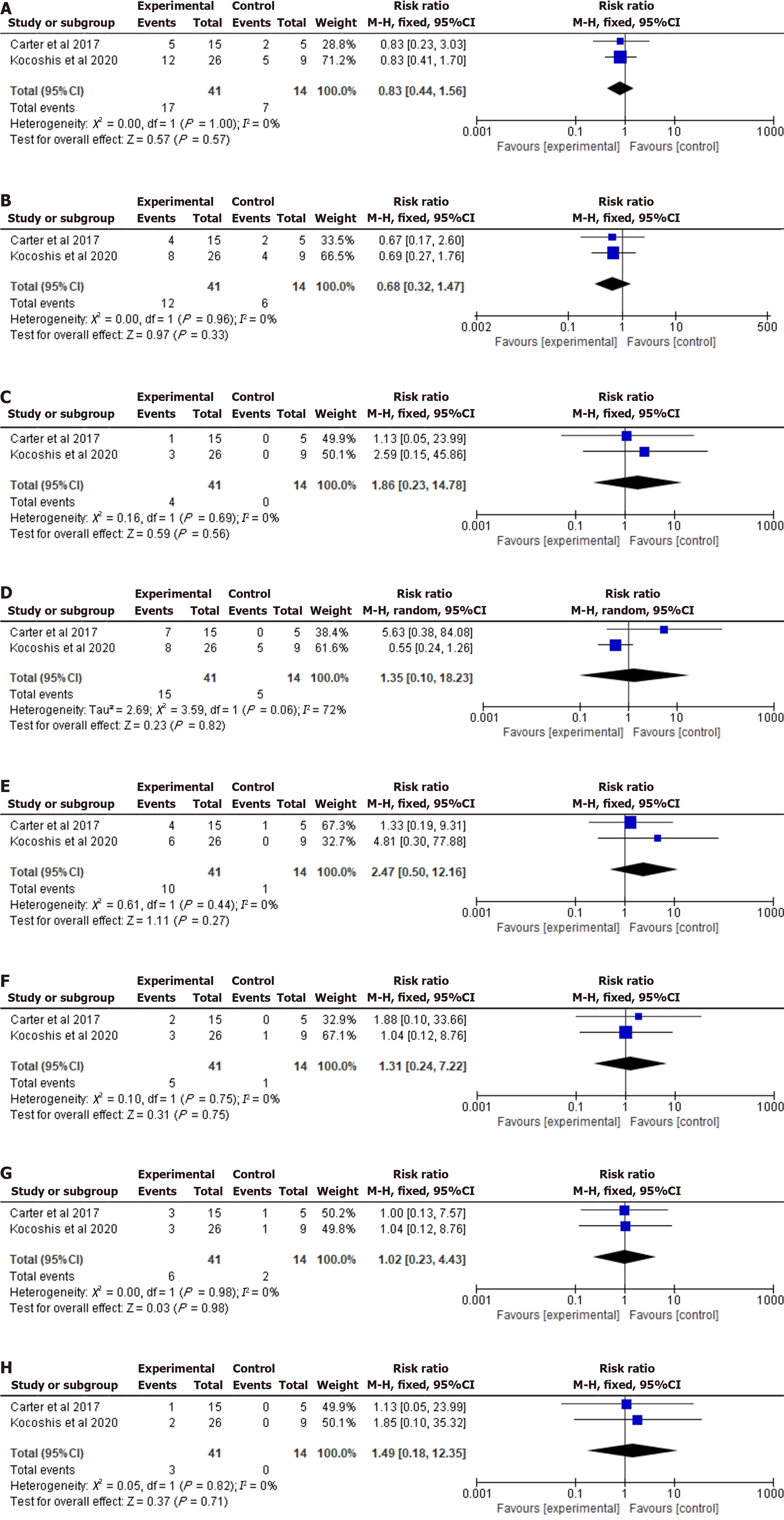

Incidence of infection events: Two RCTs including 55 pediatric patients reported the incidence of infection events[13,14]. Pooled data indicated that there was no statistically significant difference between two groups (RR = 0.83; 95%CI: 0.44-1.56; P = 0.57; I2 = 0%). A forest plot of incidence of infection events is shown in Figure 3A.

Incidence of upper respiratory tract infection: Two RCTs including 55 pediatric patients reported the incidence of upper respiratory tract infection[13,14]. Pooled data indicated that no statistically significant difference in incidence of upper respiratory tract infection (RR = 0.68; 95%CI: 0.32-1.47; P = 0.33; I2 = 0%) between the two groups. A forest plot of incidence of upper respiratory tract infection is shown in Figure 3B.

Incidence of catheter site infection: Two RCTs including 55 pediatric patients reported the incidence of catheter site infection[13,14]. Pooled data indicated that no statistically significant difference in incidence of catheter site infection (RR = 1.86; 95%CI: 0.23-14.78; P = 0.56; I2 = 0%) between the two groups. A forest plot of incidence of catheter site infection is shown in Figure 3C.

Incidence of vomiting: Two RCTs including 55 pediatric patients reported the incidence of vomiting[13,14]. Pooled data indicated that no statistically significant difference in incidence of vomiting (RR = 1.35; 95%CI: 0.10-18.23; P = 0.82; I2 = 72%) between the two groups. A forest plot of incidence of vomiting is shown in Figure 3D.

Incidence of abdominal pain: Two RCTs including 55 pediatric patients reported the incidence of abdominal pain[13,14]. Pooled data indicated that no statistically significant difference in incidence of abdominal pain (RR = 2.47; 95%CI: 0.50-12.16; P = 0.27; I2 = 0%) between the two groups. A forest plot of incidence of abdominal pain is shown in Figure 3E.

Incidence of nausea: Two RCTs including 55 pediatric patients reported the incidence of nausea[13,14]. Pooled data indicated that no statistically significant difference in incidence of nausea (RR = 1.31; 95%CI: 0.24-7.22; P = 0.75; I2 = 0%) between the two groups. A forest plot of incidence of nausea is shown in Figure 3F.

Incidence of diarrhea: Two RCTs including 55 pediatric patients reported the incidence of diarrhea[13,14]. Pooled data indicated that no statistically significant difference in incidence of diarrhea (RR = 1.02; 95%CI: 0.23-4.43; P = 0.98; I2 = 0%) between the two groups. A forest plot of incidence of diarrhea is shown in Figure 3G.

Incidence of abdominal distension: Two RCTs including 55 pediatric patients reported the incidence of abdominal distension[13,14]. Pooled data indicated that no statistically significant difference in incidence of abdominal distension (RR = 1.49; 95%CI: 0.18-12.35; P = 0.71; I2 = 0%) between the two groups. A forest plot of incidence of abdominal distension is shown in Figure 3H.

The RIS of incidence of infection events was estimated to be 1069 through TSA, which meant more sample sizes were still needed to verify the results (Figure 4).

We used GRADEpro to evaluate the certainty of the outcomes. Overall, the overall certainty of evidence for this systematic review and meta-analysis was moderate. The details are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

This study is the first to comprehensively evaluate the safety profile of teduglutide in the treatment of SBS in children through a systematic review and trial sequence analysis. Analysis of three RCTs involving 115 pediatric patients showed no statistically significant differences between the teduglutide treatment group and the control group in terms of infection events and gastrointestinal adverse event rates. This finding has important implications for clinical practice, suggesting that teduglutide may be safe in pediatric populations; however, further interpretation is needed in conjunction with the existing evidence base.

Current results indicate that teduglutide, as a GLP-2 analogue, does not significantly increase the risk of infection in children with SBS (RR = 0.83; 95%CI: 0.44-1.56). This finding is particularly important because patients with intestinal failure often require long-term PN support, with catheter-related infection rates as high as 40%-50%. In this study, there was no significant increase in the risk of catheter-site infections (RR = 1.86; 95%CI: 0.23-14.78), suggesting that teduglutide may not cause additional damage to immune barrier function. Notably, upper respiratory tract infections, a common complication in pediatric populations, also showed no difference between the two groups (RR = 0.68; 95%CI: 0.32-1.47), providing preliminary support for the drug's safety in susceptible populations.

In terms of gastrointestinal adverse reactions, the incidence rates of all key symptoms (vomiting, abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, nausea) did not show significant differences between groups. Notably, for diarrhoea-a core symptom of SBS-the RR between the Teduglutide group and the control group was close to neutral (RR = 1.02; 95%CI: 0.23-4.43). This aligns with teduglutide’s theoretical mechanism: It promotes intestinal mucosal repair by increasing villus height and crypt depth, which improves absorption function. Thus, it may theoretically alleviate (rather than induce or exacerbate) diarrhea symptoms. While the point estimates for vomiting (RR = 1.35) and bloating (RR = 1.49) were slightly higher, the wide CI suggest that current evidence cannot rule out the possibility of a zero effect. Notably, wide CI for vomiting and abdominal distension (RR = 1.49; 95%CI: 0.18-12.35) highlight that 'no statistically significant difference' does not mean 'clinically safe'. These intervals include values that could represent clinically meaningful increases in adverse events, emphasizing the need for larger studies to resolve uncertainty. Additional safety endpoints, including cardiovascular, metabolic, hepatic, allergic, drug interaction, and neurological effects, were evaluated using data from the included RCTs. No cardiovascular events (e.g, hypotension, tachycardia) or allergic reactions (e.g., rash, anaphylaxis) were reported in any study[13-15]. For liver function, Cucinotta et al[15] monitored serum alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels, with no significant differences between the teduglutide group (ALT: 35 ± 12 U/L; AST: 30 ± 8 U/L) and control group (ALT: 32 ± 10 U/L; AST: 28 ± 7 U/L; both P > 0.05). Metabolic effects (e.g., blood glucose, lipid changes) and drug interactions were not systematically assessed, as most pediatric participants did not use concurrent medications. Neurological symptoms (e.g., headache, dizziness) were not mentioned in any trial. However, the small sample size and short follow-up limit the detection of rare adverse events in these domains.

This study employed TSA to address the risk of false positives in traditional meta-analyses with limited studies. The RIS calculated for the primary outcome (infection events) was 1069 cases, while the actual sample size included was only 55 cases, suggesting that the conclusions still require validation through larger-scale studies. Despite this, the heterogeneity of the existing data was well controlled, reflecting high methodological consistency among the included studies. The GRADE assessment of evidence quality indicated moderate certainty overall, with the main limiting factors including: (1) A small number of included RCTs (only 3); and (2) The total sample size did not reach the RIS value estimated by TSA. It is worth noting that all included studies used a placebo-controlled design, which significantly reduced the risk of bias due to differences in control measures. Assessment using the ROB2 tool showed that the risk of bias in the randomization process and outcome measurement domains was low, but some studies had limitations in the handling of missing data.

Based on current evidence, teduglutide demonstrates acceptable safety characteristics in the treatment of SBS in children; however, an individualized monitoring system should be established: (1) During the initial treatment phase, attention should be paid to symptoms of vomiting and abdominal distension, particularly in patients with residual intestinal segments < 50 cm; (2) Regular monitoring of serum gastrin levels is recommended (animal studies suggest that GLP-2 may stimulate gastrin secretion); (3) Serum citrulline (a marker of intestinal mucosal integrity) and liver function markers (ALT, AST) should be periodically assessed-Kocoshis et al[14] reported no significant changes in serum citrulline (teduglutide: 25 ± 5 μmol/L vs control: 23 ± 4 μmol/L; P = 0.38), but long-term data are lacking; and (4) Patients dependent on PN should maintain standard catheter care protocols, although no increased risk of infection was observed.

The primary limitations of this study include the small total sample size (115 patients) and limited number of included RCTs (n = 3), which reduce the stability of effect size estimates. For example, the extremely wide 95%CI for vomiting (RR = 1.35; 95%CI: 0.10-18.23) indicates high uncertainty about the true effect. Additionally, publication bias remains a concern: While funnel plots could not be generated (required ≥ 10 studies), studies reporting positive safety outcomes may be more likely to be published, leading to potential overestimation of safety. As a chronic condition, SBS requires assessment of the long-term safety of medications, particularly focusing on: (1) The risk of intestinal adenomatous lesions (due to GLP-2's proliferative effects); (2) Effects on bone metabolism (animal studies suggest changes in bone turnover markers); and (3) Potential for adaptive growth delay. Additionally, existing studies have not stratified by age (infants vs school-age children), and intestinal mucosal repair capacity may vary with age. Future research should priorities the following directions: (1) Conduct multi-center RCTs to achieve the sample size required for TSA estimation of RIS; (2) Extend the follow-up period; (3) Develop child-specific adverse reaction evaluation scales (e.g., diarrhoea grading based on fecal characteristics); (4) Explore biomarker-guided individualized dosing (e.g., serum citrulline levels reflecting intestinal function); and (5) Strengthen population data from different countries. Inconsistency in outcome definitions across studies also introduces bias. For infectious events, most studies used CDC criteria for catheter site infection (local redness/purulence with positive culture)[13,14], but Cucinotta et al[15] did not specify the fever threshold for upper respiratory tract infection (e.g., ≥ 38.0 °C vs ≥ 38.5 °C), leading to minor heterogeneity. Additionally, the follow-up duration (12-24 weeks) is insufficient to assess long-term safety risks of teduglutide, such as intestinal adenomatous lesions (due to GLP-2’s proliferative effects) or impacts on bone metabolism-key concerns for a drug used in growing children. All three included RCTs were conducted in Europe and North America, with no data from Asian, African, or Latin American populations. Regional differences in SBS etiologies (e.g., higher rates of necrotizing enterocolitis in some regions) and clinical practices (e.g., PN management protocols) may affect teduglutide’s safety profile, limiting the generalizability of our findings to global pediatric populations.

Teduglutide does not increase infection or gastrointestinal adverse event risk in pediatric SBS, but small sample sizes limit conclusions. Larger studies are needed.

| 1. | Massironi S, Cavalcoli F, Rausa E, Invernizzi P, Braga M, Vecchi M. Understanding short bowel syndrome: Current status and future perspectives. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:253-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pironi L. Definition, classification, and causes of short bowel syndrome. Nutr Clin Pract. 2023;38 Suppl 1:S9-S16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bering J, DiBaise JK. Short bowel syndrome: Complications and management. Nutr Clin Pract. 2023;38 Suppl 1:S46-S58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lauro A, Lacaille F. Short bowel syndrome in children and adults: from rehabilitation to transplantation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:55-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Premkumar MH, Soraisham A, Bagga N, Massieu LA, Maheshwari A. Nutritional Management of Short Bowel Syndrome. Clin Perinatol. 2022;49:557-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Winkler MF, Smith CE. Clinical, social, and economic impacts of home parenteral nutrition dependence in short bowel syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:32S-37S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vanderhoof JA, Young RJ. Enteral and parenteral nutrition in the care of patients with short-bowel syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:997-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jeppesen PB, Pertkiewicz M, Messing B, Iyer K, Seidner DL, O'keefe SJ, Forbes A, Heinze H, Joelsson B. Teduglutide reduces need for parenteral support among patients with short bowel syndrome with intestinal failure. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1473-1481.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chiba M, Masumoto K, Kaji T, Matsuura T, Morii M, Fagbemi A, Hill S, Pakarinen MP, Protheroe S, Urs A, Chen ST, Sakui S, Udagawa E, Wada M. Efficacy and Safety of Teduglutide in Infants and Children With Short Bowel Syndrome Dependent on Parenteral Support. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2023;77:339-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wales PW, Hill S, Robinson I, Raphael BP, Matthews C, Cohran V, Carter B, Venick R, Kocoshis S. Long-term teduglutide associated with improved response in pediatric short bowel syndrome-associated intestinal failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;79:290-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51963] [Article Influence: 10392.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Online Tool to Evaluate the Certainty and Importance of the Evidence-GRADE Pro Evidence to recommendation in one platform. [cited 15 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.gradepro.org/. |

| 13. | Carter BA, Cohran VC, Cole CR, Corkins MR, Dimmitt RA, Duggan C, Hill S, Horslen S, Lim JD, Mercer DF, Merritt RJ, Nichol PF, Sigurdsson L, Teitelbaum DH, Thompson J, Vanderpool C, Vaughan JF, Li B, Youssef NN, Venick RS, Kocoshis SA. Outcomes from a 12-Week, Open-Label, Multicenter Clinical Trial of Teduglutide in Pediatric Short Bowel Syndrome. J Pediatr. 2017;181:102-111.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kocoshis SA, Merritt RJ, Hill S, Protheroe S, Carter BA, Horslen S, Hu S, Kaufman SS, Mercer DF, Pakarinen MP, Venick RS, Wales PW, Grimm AA. Safety and Efficacy of Teduglutide in Pediatric Patients With Intestinal Failure due to Short Bowel Syndrome: A 24-Week, Phase III Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44:621-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cucinotta U, Acunzo M, Payen E, Talbotec C, Chasport C, Alibrandi A, Lacaille F, Lambe C. The Impact of Teduglutide on Real-Life Health Care Costs in Children with Short Bowel Syndrome. J Pediatr. 2024;272:113882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/