Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111864

Revised: September 14, 2025

Accepted: November 10, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 0.8 Hours

Postoperative nutritional management of gastric cancer (GC) remains a problem that needs to be solved in clinical treatment.

To develop an early graded nutrition management plan and evaluate its impact on feeding tolerance, nutritional status, and prognosis.

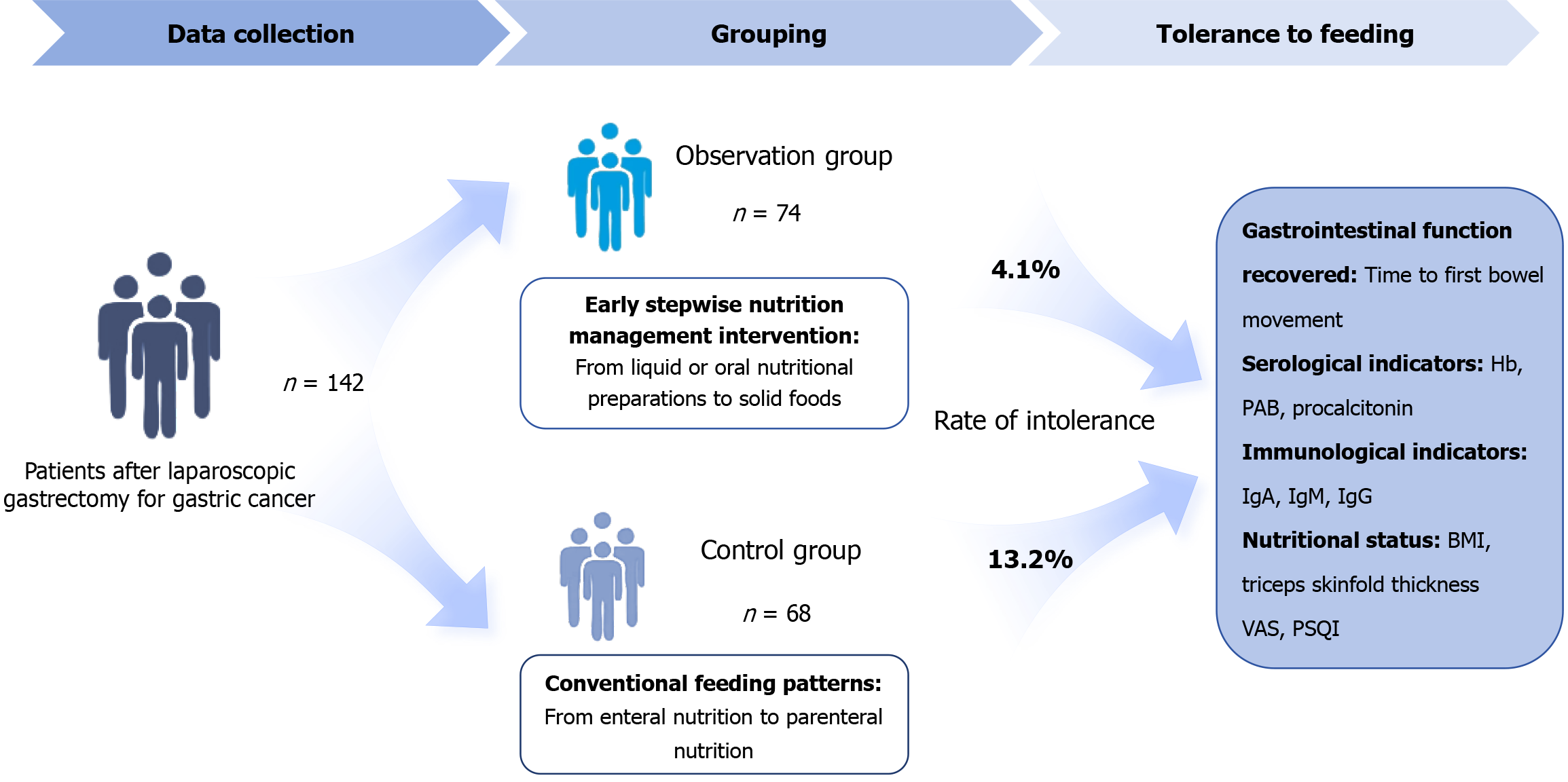

In total, 142 patients who underwent laparoscopic radical gastrectomy at Jiujiang University Affiliated Hospital between August 2021 and August 2022 were in

The feeding intolerance rates in the control and observation groups were 13.2% and 4.1%, respectively. Hospitalization time and first defecation times in the ob

Compared with the conventional postoperative feeding, early stepwise nutritional management can significantly enhance the nutritional status of patients with GC after surgery, improve their feeding tolerance, and reduce postoperative complications.

Core Tip: Early stepwise nutrition management benefits postoperative gastric cancer patients. It reduces feeding intolerance, shortens hospitalization and first defecation time, improves nutritional and immunological status, and enhances pain and sleep quality, with no significant impact on overall survival.

- Citation: Liu LH, Wu SB, Zhou LY, Cai LL, Cao CP, Huang Y. Effect of early stepwise nutrition management on feeding tolerance of postoperative patients with gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 111864

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/111864.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111864

Worldwide, gastric cancer (GC) constitutes a leading cause of cancer-associated mortality[1]. Approximately 65%-85% of patients with GC experience malnutrition[2,3]. Given the distinct pathophysiology of this malignancy, malnutrition has emerged as a critical determinant influencing clinical outcomes, including overall and disease-specific survival[4]. Common manifestations of nutritional deficits include hypoalbuminemia, organ dysfunction, and immunosuppression. Furthermore, malnutrition is linked to an increased risk of postoperative complications such as surgical site infections, dumping syndrome, and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. Malnutrition and related complications account for 40% of cancer deaths[5]. Therefore, early nutritional screening, timely intervention, and correction of dietary deficiencies are essential to improving postoperative recovery and long-term prognosis in GC patients.

Postoperative nutritional support maintains the nutritional status of the body during the postoperative catabolic period, which is the main determinant of recovery after abdominal surgery[6]. Nutritional support currently includes enteral and parenteral nutrition. Parenteral nutritional support can alleviate malnutrition to a certain extent and is the first choice for patients who cannot receive oral nutrition. However, this can lead to atrophy of the gastric mucosa because of the stimulation of the gastrointestinal tract by a long-term lack of food. It also slows the recovery of the intestinal barrier, leading to an imbalance in the normal intestinal flora and a reduction in its ability to absorb nutrients. The study by Jiang et al[7] found that preoperative short-term parenteral support may not have significant benefits for complications or overall survival among GC patients. For patients with GC, intestinal function recovered within 6-12 hour after surgery, suggesting that early oral enteral nutrition (EN) support after surgery is feasible and safe[8]. The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery guidelines recommend starting postoperative oral nutrition on the first day after gastric surgery[9]. Moreover, early EN can stimulate the recovery of normal peristalsis of the gastrointestinal tract, accelerate the recovery of absorption, and avoid excessive infusion volume that aggravates the burden of the gastrointestinal tract[10]. This positively affects the recovery of patients with GC. Chen et al[11] found that EN was safe and well tolerated, shortened the length of hospital stay, and reduced the cost of total gastrectomy for GC. A case-control study by Jang and Jeong[12] also confirmed these findings. However, for GC patients, postoperative nutritional recovery is often a long and complex process. Especially for some patients who cannot tolerate EN, how to accurately calculate their nutritional requirements in the early postoperative stage and develop a safe, effective, and individualized nutritional support plan are still key issues that need to be further explored in current clinical practice. Therefore, the establishment of early scientific and reasonable nutritional support and management system may significantly promote the overall postoperative rehabilitation of GC patients, further reduce the risk of complications, and effectively reduce feeding intolerance. In this context, by constructing a systematic early stepwise nutrition management (ESNM) program after GC surgery, this study aims to compare the differences in feeding tolerance of patients under different nutritional intervention models, and to analyze its related influencing factors and internal mechanisms. Through empirical data, this study hopes to provide a basis for reducing postoperative complications, improving nutritional status and clinical prognosis of patients, and also provide valuable theoretical reference and practical insights for the formulation of scientific and reasonable nutritional management strategies for patients with GC after surgery.

This study was approved by Jiujiang University Affiliated Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the Decla

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age ≥ 18 years; (2) All patients meeting the relevant diagnostic criteria of GC from "Chinese Consensus on Screening, Endoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Gastric Cancer”, and diagnosed by pathological examination; and (3) Receiving laparoscopic radical gastrectomy, informed consent was obtained.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Serious concomitant diseases, including chronic cardiopulmonary disease and chronic renal failure; (2) Pregnant or breastfeeding women; (3) Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 score of less than 3; (4) Diagnosis of immune disorders or known immunodeficiency; and (5) Unconsciousness, inability to communicate, or cognitive impairment.

The demographic indicators included demographic data (such as age, duration of disease, weight, course of disease, hypertension, diabetes) and clinical data – serological indicators such as hemoglobin (Hb), serum total protein (STP), albumin (Alb), prealbumin (PAB), transferrin (TRF), C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT); immune indicators such as immunoglobulin A (IgA), immunoglobulin M (IgM), immunoglobulin G (IgG); triceps skinfold thickness, body mass index (BMI), upper arm muscle circumference; clinical symptoms included nausea and vomiting, aspiration, diarrhea, gastric retention, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, infection, recovery time of bowel sounds, first exhaust time, and first defecation time.

When patients of either group were admitted to the hospital, the nursing staff popularized the knowledge of GC-related diseases, possible causes, and triggers for the patients and their families and informed them of the precautions and purposes of preoperative and postoperative abstinence and fasting, as well as gastrointestinal decompression, to improve treatment compliance. Basic treatments such as fasting, gastrointestinal decompression, and anti-inflammatory fluid replacement were administered according to the doctors’ advice. For patients with other underlying diseases, appropriate treatments were provided. For instance, patients with hypertension received antihypertensive treatment, whereas those with hyperglycemia received treatment for hypoglycemia. During the treatment process, changes in the patient’s vital signs, such as blood pressure, were monitored, and psychological guidance was provided. When discharged from the hospital, patients were provided guidance to avoid triggering factors and were advised to lead a regular life, perform appropriate exercise, avoid fatigue, and undergo regular checkups. All included patients were followed up for 3 years, and the 3-year survival rate was calculated.

Parenteral nutritional support was provided 24 hours after operation to establish peripheral venous access or central venous access (including through the subclavian deep vein and internal jugular deep vein). Based on the patient's basic condition (disease condition, BMI, physiological needs, etc.), the energy required by the patient was calculated, and water, protein, carbohydrates, and trace elements were replenished in a timely and sufficient manner. Intravenous infusion of 10% fat emulsion (500 mL), 7% amino acids (750 mL), and 25% glucose (1000 mL) was routinely administered. Blood glucose management was performed throughout the perioperative period, maintaining glycated Hb < 8.5%, pre-meal blood glucose of 8-10 mmol/L, and random blood glucose of 8-12 mmol/L 2 hours after a meal or when unable to eat. The energy intake was approximately 25-30 kcal/kg/day, the calorie intake was calculated at 104.65-125.58 kJ/kg/day, and the target protein requirement was recommended to be calculated at 1.2-1.5 g/kg/day. Continuous infusion was administered until the patient could eat normally. During parenteral nutrition, the nutrient solution was prepared strictly according to the dosage. Therefore, the principles of immediate preparation, use, and sterility were strictly followed. When infusing, attention was paid to the infusion speed, time, and temperature to reduce patient discomfort.

An early stepwise nutritional management intervention was administered based on the control group. From the first postoperative day, approximately 500-1000 mL of liquid or oral nutritional preparations were consumed. Therefore, oral nutrition preparations were recommended. Patients undergoing non-total gastrectomy transitioned to solid food on the second and third days and adjusted their food intake according to tolerance of the gastrointestinal tract. EN was re

Evaluation criteria for feeding intolerance: If the residual gastric amount extracted every 6 hours after infusion of the nutrient solution exceeded 200 mL. Alternatively, feeding intolerance was also considered if a minimum feeding amount of 20 kcal/kg (1 kcal = 4.18 kJ) per day was not achieved within 72 hours after the infusion of nutrition.

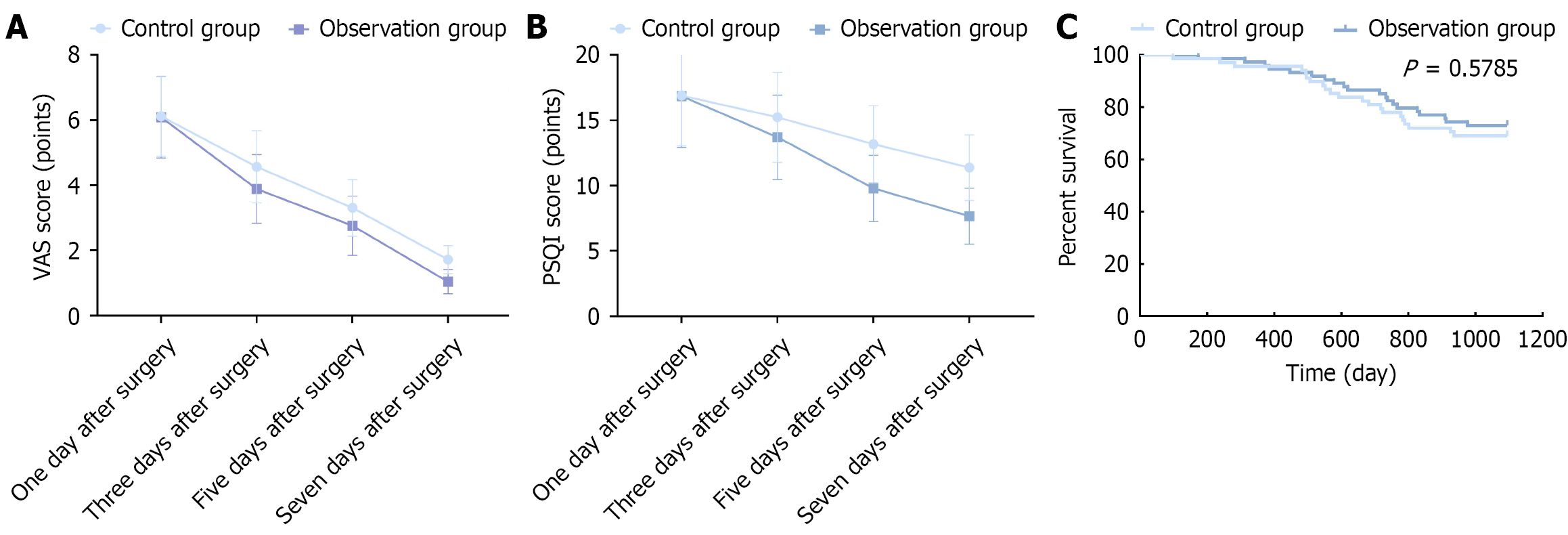

At 1 day, 3 days, 5 days, and 7 days after the operation, the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)[13] was used to evaluate pain. The total score is 10 points, and a higher score indicates pain of greater severity. At the same postoperative days, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[14] was used to evaluate sleep quality. The total score is 21 points, and a higher score indicates worse sleep quality.

Statistical analyses were conducted with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD, while categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons were carried out using t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical data. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were assessed with the log-rank test.

No significant differences were observed in age, sex, disease course, body weight, hypertension, or diabetes between the two groups (P > 0.05), indicating that the two groups were balanced and comparable (Table 1).

| Item | Control group | Observation group | t/χ² | P value |

| Age (years) | 54.12 ± 7.89 | 54.42 ± 7.13 | -0.226 | 0.842 |

| Sex | 0.048 | 0.872 | ||

| Male | 38 | 40 | ||

| Female | 30 | 34 | ||

| Duration (months) | 2.12 ± 0.31 | 2.06 ± 0.37 | 0.231 | 0.819 |

| Body weight (kg) | 57.56 ± 18.74 | 58.98 ± 20.65 | 0.384 | 0.904 |

| Hypertension | 0.183 | 0.669 | ||

| Yes | 27 | 32 | ||

| No | 41 | 42 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.123 | 0.726 | ||

| Yes | 22 | 26 | ||

| No | 46 | 48 |

Overall, patients in the observation group demonstrated accelerated recovery compared to the control group, as evidenced by shorter durations in hospital stay, earlier return of bowel sounds, and reduced time to first exhaust and first defecation. However, among these parameters, only the length of hospital stays (12.63 ± 3.79 days vs 14.89 ± 4.13 days, P < 0.05) and the time to first defecation (68.02 ± 7.40 hours vs 71.64 ± 8.51 hours, P < 0.05) reached statistical significance. The detailed results are presented in Table 2.

| Item | Length of hospital stay (days) | Bowel sound recovery time (hours) | First defecation time (hours) | Time of first defecation (hours) |

| Control group | 14.89 ± 4.13 | 37.95 ± 3.64 | 61.12 ± 6.78 | 71.64 ± 8.51 |

| Observation group | 12.63 ± 3.79 | 37.23 ± 3.76 | 60.85 ± 7.01 | 68.02 ± 7.40 |

| t value | 5.892 | 0.141 | 0.293 | 4.713 |

| P value | 0.000 | 0.972 | 0.766 | 0.000 |

No significant differences were noted in Hb, Alb, STP, PAB, TRF, CRP, and PCT levels and IgA, IgG, and IgM levels between the observation and control groups 1 day before the operation (P > 0.05). At 7 days after operation, there were significant differences in Hb, PAB, TRF, PCT, IgA, IgG, and IgM levels between the two groups (P < 0.05). At day 7, Hb, PAB, TRF, IgA, IgG, and IgM levels in the observation group were significantly higher, and PCT levels were significantly lower (P = 0.035) (Tables 3 and 4).

| Item | Hemoglobin (g/L) | Albumin (g/L) | Serum total protein (g/L) | Prealbumin (mg/L) | Transferrin (g/L) | C-reactive protein (mg/L) | Procalcitonin (ng/L) |

| 1 day before the operation | |||||||

| Control group | 108.25 ± 8.12 | 35.68 ± 2.65 | 48.65 ± 6.01 | 216.45 ± 28.37 | 2.17 ± 0.75 | 8.17 ± 1.63 | 1.04 ± 0.43 |

| Observation group | 107.43 ± 5.67 | 34.71 ± 1.98 | 49.21 ± 5.54 | 220.12 ± 30.75 | 2.20 ± 0.68 | 8.43 ± 1.46 | 0.98 ± 0.34 |

| t value | 0.243 | 0.226 | -0.188 | -0.328 | -0.215 | -0.432 | 0.285 |

| P value | 0.804 | 0.823 | 0.815 | 0.742 | 0.784 | 0.731 | 0.784 |

| 7 days after the operation | |||||||

| Control group | 110.32 ± 5.43 | 38.87 ± 2.98 | 56.68 ± 5.87 | 264.58 ± 25.61 | 2.20 ± 0.63 | 6.34 ± 1.27 | 0.76 ± 0.33 |

| Observation group | 117.68 ± 6.07 | 39.45 ± 3.41 | 58.75 ± 6.35 | 300.47 ± 38.38 | 2.76 ± 0.88 | 5.96 ± 1.45 | 0.42 ± 0.25 |

| t value | -2.475 | -1.052 | -0.977 | -2.786 | -2.584 | 1.003 | 2.645 |

| P value | 0.025 | 0.284 | 0.324 | 0.010 | 0.032 | 0.312 | 0.035 |

| Item | Immunoglobulin A | Immunoglobulin G | Immunoglobulin M | |||

| 1 day before operation | 7 days after operation | 1 day before operation | 7 days after operation | 1 day before operation | 7 days after operation | |

| Control group | 2.03 ± 0.41 | 1.51 ± 0.37 | 5.53 ± 0.87 | 4.29 ± 0.73 | 0.81 ± 0.10 | 0.54 ± 0.07 |

| Observation group | 1.98 ± 0.39 | 1.82 ± 0.31 | 5.56 ± 0.79 | 5.09 ± 0.66 | 0.79 ± 0.08 | 0.62 ± 0.05 |

| t value | 0.193 | -6.125 | -0.087 | -5.287 | 0.273 | -2.986 |

| P value | 0.862 | 0.000 | 0.981 | 0.000 | 0.741 | 0.011 |

No statistically significant differences were observed in baseline anthropometric parameters – including BMI, upper arm muscle circumference, and triceps skinfold thickness – between the two groups on the day preceding surgery (all P > 0.05). However, at postoperative day 7, significant intergroup differences emerged. The observation group exhibited markedly higher BMI values (19.43 ± 2.76 kg/m2vs 18.96 ± 2.98 kg/m2, P < 0.05) and greater triceps skinfold thickness measurements (0.94 ± 0.06 cm vs 0.87 ± 0.13 cm, P < 0.05) compared with the control group. These results are summarized in Table 5.

| Item | Body mass index (kg/m2) | Upper arm muscle circumference (cm) | Triceps skinfold thickness(cm) | |||

| IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | |

| Control group | 19.76 ± 3.18 | 18.96 ± 2.98 | 20.11 ± 4.09 | 20.03 ± 3.77 | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 0.87 ± 0.13 |

| Observation group | 19.81 ± 3.02 | 19.43 ± 2.76 | 20.01 ± 3.98 | 19.95 ± 3.84 | 1.01 ± 0.12 | 0.94 ± 0.06 |

| t value | -0.317 | -2.997 | 0.968 | 0.752 | 0.912 | 2.007 |

| P value | 0.809 | 0.008 | 0.253 | 0.421 | 0.287 | 0.041 |

Postoperative complications were systematically evaluated and compared between the two cohorts. The incidence of feeding intolerance was significantly higher in the control group, occurring in 9 patients (13.2%), compared with only 3 cases (4.1%) in the observation group. Documented manifestations of intolerance included nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, distension, and diarrhea. The observed difference in the rate of feeding intolerance between the groups was statis

| Item | Nausea and vomiting | Aspiration of aspiration | Diarrhea | Abdominal pain and distention | Gastric retention | Infection | Others | Total number of cases |

| Control group | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 (13.2) |

| Observation group | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.1) |

| t value | 0.433 | 1.096 | 0.433 | 0.433 | - | 1.096 | 1.096 | 3.861 |

| P value | 0.510 | 0.295 | 0.510 | 0.510 | - | 0.295 | 0.295 | 0.049 |

According to the VAS score results, no statistically significant difference was observed in the pain status between two groups on the first day after surgery (P > 0.05), whereas the VAS scores of the observation group on the third, fifth and seventh days after surgery were significantly lower than (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A). According to the PSQI score results, no statistically significant difference was noted in sleep status between two groups on the first day after surgery (P > 0.05), whereas the PSQI scores of the observation group on the third, fifth and seventh days after surgery were significantly lower (P < 0.05; Figure 2B).

The survival analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in the three-year postoperative survival rate between two groups (P > 0.05; Figure 2C).

Globally, GC ranks as the fourth most common cause of mortality among cancer-related deaths[15]. The nutritional status prior to surgery plays a critical role in determining prognostic outcomes, including overall and disease-specific survival, in GC patients undergoing surgical intervention[4]. Malnutrition is also considered one of the most important factors leading to postoperative complications and poor prognosis in patients with GC after gastrectomy[16,17]. Wang et al[18] evaluated nutritional status in 101 GC patients (81 subtotal and 20 total gastrectomies) and identified that 52.5% were either malnourished or at nutritional risk. In a study by Lee et al[19] 21.4% of patients remained malnourished 1 year after surgery. In a study of 2322 hospitalized GC patients in China, Guo et al[20] applied the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment tool and demonstrated that 80.4% presented with malnutrition, among whom 45.1% required urgent nutritional intervention. Nutritional support currently includes both enteral and parenteral nutrition[21]. Parenteral nutrition support can alleviate malnutrition to a certain extent; however, the long-term lack of food stimulation of the gastrointestinal tract leads to gastric mucosal atrophy, delays intestinal barrier recovery, causes an imbalance in normal intestinal flora, reduces their ability to absorb nutrients, and increases the vulnerability of the patient to abdominal pain, aspiration, and other feeding intolerance symptoms, resulting in slow recovery[22]. In contrast, numerous studies have supported the advantages of early EN intervention in improving nutritional status and enhancing immune function[23,24]. However, for certain specific pathological conditions or postoperative situations, premature or inappropriate initiation of EN may exacerbate intestinal ischemia or reperfusion injury and even increase the risk of anastomotic leakage. Therefore, the selection of nutritional support strategies should consider the differences among individual patients and their gastrointestinal tract tolerance. Possible underlying mechanisms include enhancement of intestinal barrier function and local immunity by EN via direct mucosal nutrition, increased release of secretory IgA, and maintenance of the stability of the microbiota. However, in cases of unstable hemodynamics or severe damage to intestinal function, forced EN may have adverse effects owing to increased metabolic load and oxidative stress. Therefore, ESNM can provide scientific and reasonable nutritional support in time after surgery or in the early stage of disease by combining EN and parenteral nutrition intervention strategies. In this mode, nutrients can provide patients with sufficient calories and essential macronutrients and micronutrients through staged and individually adjusted infusion, which can effectively meet the energy needs of the body under high stress. Furthermore, the nutrition management plan emphasizes the dynamic adjustment of nutrient solution concentration, infusion rate, and total intake according to the patient's actual disease status, gastrointestinal tolerance, and metabolic characteristics. This step-by-step intervention strategy not only helps to maintain the normal structure and function of tissues and cells, but also promotes protein synthesis and reduces inflammatory response, so as to support the recovery of body function more effectively. At the same time, gradually adaptive feeding methods can significantly reduce the risk of feeding intolerance such as abdominal distension, diarrhea and vomiting, further improve the effect of nutritional intake, and ultimately have a positive impact on the short-term recovery and long-term prognosis of patients.

In this study, the length of hospital stays and time to first defecation in the observation group were shorter, indicating that early stepwise nutritional management can shorten the remission time of clinical symptoms in patients after GC surgery and accelerate the recovery process. Barlow et al[23] also reported similar results. Hur et al[24] found that early EN after GC surgery could shorten the hospital stay and improve many parameters of the postoperative quality of life of patients. This may be because providing nutritional management to patients in the early postoperative period can enable them to obtain sufficient calories in the early stages of the disease, improve their hypermetabolic and hypercatabolic states, and shorten the natural course of the disease. In addition, adjusting the total infusion volume and speed based on the patient's gastrointestinal function can stimulate the gastrointestinal tract to resume normal peristalsis, accelerate the recovery of absorption function, prevent excessive infusion volume and burden on the gastrointestinal tract, simultaneously inhibit the secretion of gastric acid, accelerate the recovery of the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier protection system, maintain the integrity of the intestinal mucosa, and protect the growth of intestinal flora. It can effectively relieve abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and other conditions and promote recovery from disease.

In addition, when the body is in a state of stress, protein catabolism increases, resulting in decreased ALB levels. In this study, after the intervention, Hb and TFR levels in the observation group were higher, and the incidence of feeding intolerance in the observation group was lower. This indicates that early stepwise nutritional management in patients with GC who had undergone surgery can improve their nutritional status and reduce the occurrence of feeding intolerance. The possible reasons can be summarized as follows: (1) Timely scientific and reasonable nutritional support in the early stage of disease recovery can provide patients with sufficient energy reserves, essential amino acids and a variety of micronutrients required by the body, so as to effectively meet the nutritional needs of postoperative hyper

In conclusion, early stepwise nutritional management in postoperative patients with GC can effectively shorten the improvement time of clinical symptoms, reduce the occurrence of feeding intolerance, improve nutritional indicators, and facilitate disease recovery.

A limitation of this study is its short observation time, which makes it impossible to clarify the impact of early postoperative stepwise nutritional management on the long-term survival rate of patients after GC surgery. In the future, the observation time needs to be extended. In addition, the details of the randomization process and blinding were insufficient, increasing the risk of selection and observer bias. Furthermore, multicenter prospective experiments need to be conducted to explore the practical applications of early stepwise nutritional management.

Compared with the conventional postoperative feeding method, early stepwise nutritional management can significantly improve the nutritional status of patients with GC after surgery, improve feeding tolerance, reduce postoperative complications, and improve patient prognosis.

| 1. | Poorolajal J, Moradi L, Mohammadi Y, Cheraghi Z, Gohari-Ensaf F. Risk factors for stomach cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Health. 2020;42:e2020004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rosania R, Chiapponi C, Malfertheiner P, Venerito M. Nutrition in Patients with Gastric Cancer: An Update. Gastrointest Tumors. 2016;2:178-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gavazzi C, Colatruglio S, Sironi A, Mazzaferro V, Miceli R. Importance of early nutritional screening in patients with gastric cancer. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:1773-1778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Triantafillidis JK, Papakontantinou J, Antonakis P, Konstadoulakis MM, Papalois AE. Enteral Nutrition in Operated-On Gastric Cancer Patients: An Update. Nutrients. 2024;16:1639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xu R, Chen XD, Ding Z. Perioperative nutrition management for gastric cancer. Nutrition. 2022;93:111492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lewis SJ, Andersen HK, Thomas S. Early enteral nutrition within 24 h of intestinal surgery versus later commencement of feeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:569-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jiang Z, Lin H, Huang J, Sharma R, Lu Y, Zheng J, Chen X, Yang X, Niu M. Lack of clinical benefit from preoperative short-term parenteral nutrition on the clinical prognosis of patients treated with radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a two-center retrospective study based on propensity score matching analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024;15:96-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rinninella E, Cintoni M, Raoul P, Pozzo C, Strippoli A, Bria E, Tortora G, Gasbarrini A, Mele MC. Effects of nutritional interventions on nutritional status in patients with gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;38:28-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mortensen K, Nilsson M, Slim K, Schäfer M, Mariette C, Braga M, Carli F, Demartines N, Griffin SM, Lassen K; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Group. Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1209-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 45.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oyama K, Fushida S, Kinoshita J, Nakanuma S, Okamoto K, Sakai S, Makino I, Nakamura K, Hayashi H, Inokuchi M, Miyashita T, Tajima H, Takamura H, Ninomiya I, Ohta T. [Early Enteral Nutrition for Gastric Cancer Patients with Extended Surgery]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2017;44:1491-1493. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Chen W, Zhang Z, Xiong M, Meng X, Dai F, Fang J, Wan H, Wang M. Early enteral nutrition after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014;23:607-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jang A, Jeong O. Intolerability to postoperative early oral nutrition in older patients (≥70 years) undergoing gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A case-control study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0251844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | He Y, Lin Y, He X, Li C, Lu Q, He J. The conservative management for improving Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scoring in greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a Bayesian analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24:423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17520] [Cited by in RCA: 23654] [Article Influence: 639.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Guan WL, He Y, Xu RH. Gastric cancer treatment: recent progress and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 16. | Zhao B, Zhang J, Zhang J, Zou S, Luo R, Xu H, Huang B. The Impact of Preoperative Underweight Status on Postoperative Complication and Survival Outcome of Gastric Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2018;70:1254-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Calder PC, Deutz NEP, Erickson N, Laviano A, Lisanti MP, Lobo DN, McMillan DC, Muscaritoli M, Ockenga J, Pirlich M, Strasser F, de van der Schueren M, Van Gossum A, Vaupel P, Weimann A. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:1187-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 575] [Cited by in RCA: 850] [Article Influence: 94.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang HM, Wang TJ, Huang CS, Liang SY, Yu CH, Lin TR, Wu KF. Nutritional Status and Related Factors in Patients with Gastric Cancer after Gastrectomy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2022;14:2634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee HH, Park JM, Song KY, Choi MG, Park CH. Survival impact of postoperative body mass index in gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;52:129-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Guo ZQ, Yu JM, Li W, Fu ZM, Lin Y, Shi YY, Hu W, Ba Y, Li SY, Li ZN, Wang KH, Wu J, He Y, Yang JJ, Xie CH, Song XX, Chen GY, Ma WJ, Luo SX, Chen ZH, Cong MH, Ma H, Zhou CL, Wang W, Luo Q, Shi YM, Qi YM, Jiang HP, Guan WX, Chen JQ, Chen JX, Fang Y, Zhou L, Feng YD, Tan RS, Li T, Ou JW, Zhao QC, Wu JX, Deng L, Lin X, Yang LQ, Yang M, Wang C, Song CH, Xu HX, Shi HP; Investigation on the Nutrition Status and Clinical Outcome of Common Cancers (INSCOC) Group. Survey and analysis of the nutritional status in hospitalized patients with malignant gastric tumors and its influence on the quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:373-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Compher C, Bingham AL, McCall M, Patel J, Rice TW, Braunschweig C, McKeever L. Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46:12-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 77.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bering J, DiBaise JK. Home Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Nutrients. 2022;14:2558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Barlow R, Price P, Reid TD, Hunt S, Clark GW, Havard TJ, Puntis MC, Lewis WG. Prospective multicentre randomised controlled trial of early enteral nutrition for patients undergoing major upper gastrointestinal surgical resection. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:560-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hur H, Kim SG, Shim JH, Song KY, Kim W, Park CH, Jeon HM. Effect of early oral feeding after gastric cancer surgery: a result of randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 2011;149:561-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Huang D, Sun Z, Huang J, Shen Z. Early enteral nutrition in combination with parenteral nutrition in elderly patients after surgery due to gastrointestinal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:13937-13945. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Martos-Benítez FD, Gutiérrez-Noyola A, Soto-García A, González-Martínez I, Betancourt-Plaza I. Program of gastrointestinal rehabilitation and early postoperative enteral nutrition: a prospective study. Updates Surg. 2018;70:105-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/