Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112038

Revised: October 8, 2025

Accepted: October 31, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 121 Days and 0.6 Hours

Patients with tumors often develop multiple autoantibodies against tumor-associated antigens. Among these, antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) constitute a clinically important group distributed across the nucleus, cytoplasm, and cyto

To detect ANA fluorescence patterns in CRC using indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) and investigate their correlation with the disease.

We collected serum samples from patients and healthy controls visiting The Affiliated Panyu Central Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University between May 2023 and March 2024 for analysis. The study included 38 patients with newly diagnosed CRC, 43 patients with colorectal polyps (CRP), and 29 healthy controls. Serum ANA expression was assessed by IIF, and fluorescence patterns were recorded for each group. Differences in ANA titers were compared among each group to analyze the differences in serum ANA-positive expression, which were further analyzed to explore the correlation between ANA expression and CRC screening.

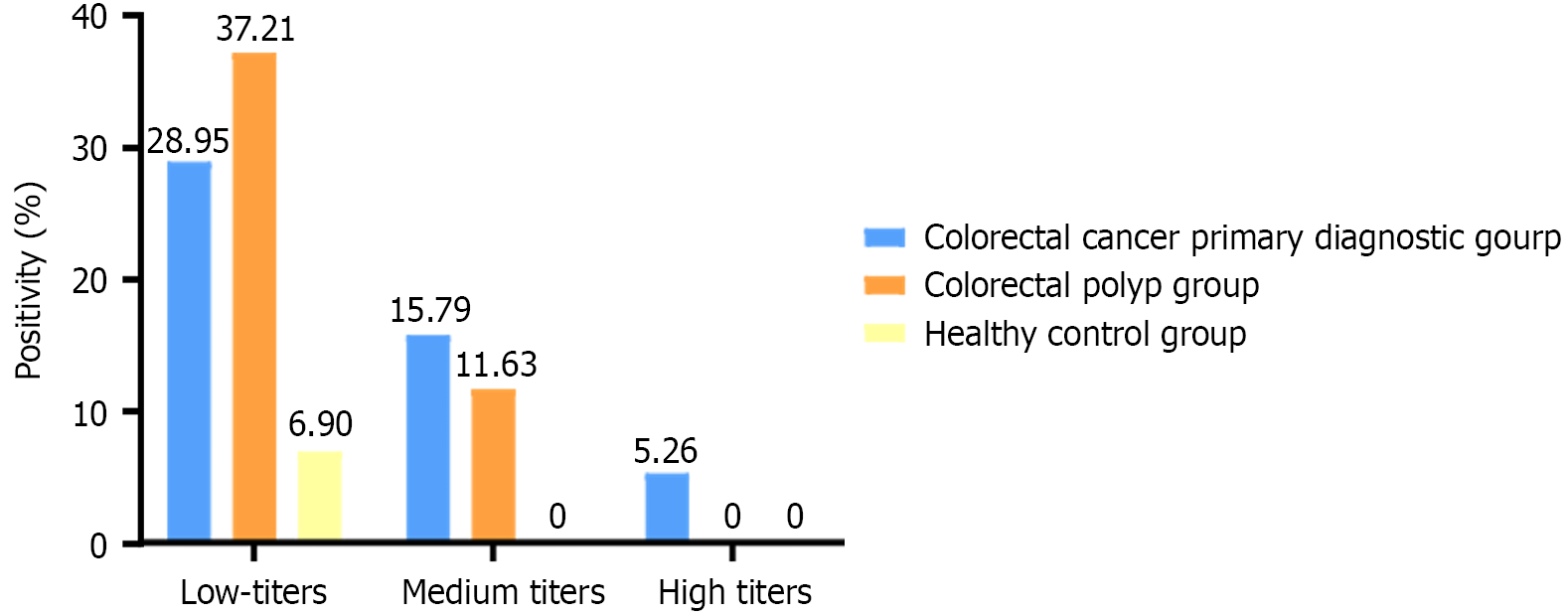

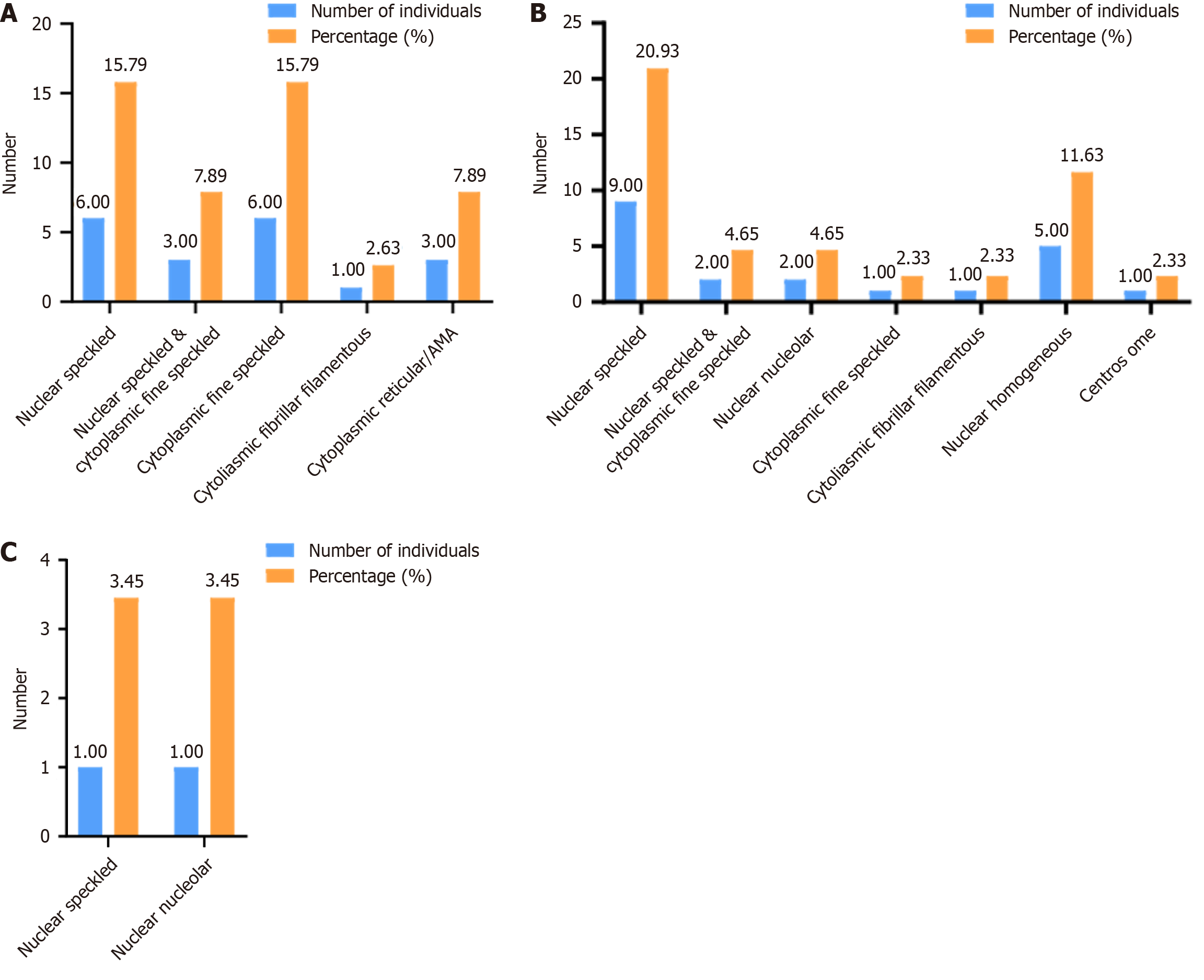

ANA positivity rates were 50.00% in the CRC group, 46.51% in the colorectal polyp group, and 6.90% in the healthy control group, with significantly higher rates in the two patient groups compared to the control group (P < 0.05). In the CRC group, the most common fluorescence patterns were nuclear speckled (15.79%) and cytoplasmic speckled (15.79%), with titers predominantly low (1:100, 28.95%). In the colorectal polyp group, nuclear speckled (18.60%) and nuclear homogeneous (11.63%) were the most frequent, with titers also predominantly low (1:100, 37.21%). The distribution of intermediate titers differed significantly among groups (P < 0.05).

ANAs are associated with both CRP and CRC and may be useful in early CRC screening. Medium-to-high ANA titers, in particular, should prompt further evaluation for possible CRC correlation. Multiple ANA fluorescence patterns can be detected across all groups, with patients with CRP and CRC showing greater pattern diversity than healthy controls.

Core Tip: Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), also known as antinuclear factors, were first identified in cases of systemic lupus erythematosus. ANA testing enhances the diagnostic accuracy of immune-mediated diseases and demonstrates high specificity. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignant neoplasms worldwide, with incidence rates in China continuing to rise. Autoantibodies are increasingly recognized as tumor markers, offering greater specificity than conventional markers and enabling earlier detection. In this study, indirect immunofluorescence was used to detect ANA fluorescence patterns in CRC and explore their correlation.

- Citation: Liang ZZ, He JH, Han ZP, Yang XY, Liao LY. Analysis of antinuclear antibody pattern distribution and correlation in patients with colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 112038

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/112038.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112038

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common malignant tumor of the gastrointestinal tract in China. It typically develops from sessile or pedunculated polyps on the mucosal surface of the large intestine and rectum, which gradually enlarge, invade the colorectal wall, and eventually form malignant tumors[1]. Globally, CRC ranks as the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality. According to Bentham Science (2021), the global inci

The onset of CRC is a complex, multistep process influenced by multiple genes, factors, and stages. Benign colorectal polyps (CRP) are common histological lesions—including adenomas, hyperplastic polyps, hamartomatous tumors, and inflammatory polyps—that are largely precancerous and closely related to CRC[7]. Evidence suggests that over 95% of CRCs develop from polyps. Under the combined influence of hereditary and acquired factors, adenomatous polyps gradually enlarge and progress to invasive carcinomas through the adenoma–carcinoma sequence. Prognosis is particularly poor in advanced CRC. Effective screening, early intervention, and optimal treatment strategies are therefore essential for improving patient outcomes[8-10].

Numerous studies have shown the presence of autoantibodies against tumor-associated antigens in patients with cancer. The production of these autoantibodies is thought to result primarily from antigenic stimulation caused by tumor cell destruction or from immunologic derangements during tumorigenesis[11]. Once formed, autoantibodies can activate the immune system to target tumor cells. Some researchers have suggested that autoantibodies, as products of the im

With increasing research on malignancies, the benefits of early screening in disease control have attracted considerable attention. In this study, we analyzed the correlation between ANA, CRP, and CRC, as well as the significance of ANA detection in early CRC screening. Specifically, we investigated the distribution of ANA patterns, the frequency of ANA positivity, and the distribution of titers among patients with a primary diagnosis of CRC, patients with CRP, and healthy individuals.

Patients who visited our hospital for consultation or examination between May 2023 and March 2024 were enrolled and divided into three groups: CRC primary diagnosis group, CRP group, and healthy controls. The study was approved by the hospital’s medical ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from all participants (and from family members where required).

Inclusion criteria for the CRC group were as follows: (1) No prior surgery or chemotherapy; (2) Pathologically confirmed new diagnosis; and (3) Absence of other malignant tumors or autoimmune diseases. Inclusion criteria for the CRP group were as follows: (1) Pathologically confirmed CRP; and (2) Absence of autoimmune diseases. Inclusion criteria for the healthy control group were as follows: (1) Normal tumor marker values; (2) Normal blood routine results; and (3) Normal liver, thyroid, kidney, and other test results.

Venous blood specimens were collected from all three groups: 38 cases in the CRC group, 43 cases in the CRP group, and 29 cases in the healthy control group. Samples were centrifuged to separate the serum, which was immediately stored at -80 °C. Only nonhemolytic, nonlipemic, and nonjaundiced specimens were included.

The test kit included BIOCHIP slides coated with human laryngeal cancer epithelial (HEp-2) cells, fluorescein-labeled anti-human IgG (goat), positive and negative controls, PBS salt (pH = 7.2), Tween 20, mounting medium, and cover glasses.

Assay results were observed using a fluorescence microscope. A 40 × objective was used to visualize the cellular matrix. The excitation filter was set at 488 nm, the spectral filter at 510 nm, and the blocking filter at 520 nm.

Test principle: Substrates consisting of HEp-2 cells and primate liver were incubated with diluted patient serum. In positive cases, the antibodies of classes IgA, IgG, and IgM bound to the antigens. In a second step, the bound antibodies were stained with fluorescein-labeled anti-human antibodies and visualized using a fluorescence microscope.

ANAs were detected using an IIF assay with HeP-2 cells as the substrate and fluorescein-labeled anti-human IgG as the secondary antibody. Serum samples were diluted 1:100 with PBS-Tween buffer. A total of 25 μL of diluted serum was added dropwise to each reaction zone of the sampling plate, which was placed on a foam platform. The biologically active side of the BIOCHIP slide was then positioned face down into the plate notch and incubated at room temperature (18 °C to 25 °C) for 30 minutes. After incubation, the slide was rinsed under running PBS-Tween buffer and immersed in a washed cup containing PBS-Tween buffer for at least 5 minutes. Next, 20 μL of FITC-labeled anti-human globulin (secondary antibody) was added dropwise to the reaction zones of a clean sampling plate.

A cover glass was prepared with mounting medium, and the BIOCHIP slide was removed from the PBS-Tween buffer. The back and edges of the slide were gently dried with a paper towel. The slide, with BIOCHIPs facing downward, was placed onto the cover glass and adjusted to ensure proper positioning. ANA fluorescence patterns and titers were then observed under the fluorescence microscope.

Criteria: ANA fluorescence patterns and titers were evaluated using the fluorescence microscope. Titers were classified as low (≥ 1:100), medium (1:320), or high (1:1000). Reporting of ANA patterns followed the recommendations of the 2018 International Consensus on ANA testing.

The percentages of ANA patterns and positive ANA titers are presented as three-dimensional clustered bar charts. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software. Categorical variables were expressed as counts, while continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Age differences among the three groups were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Gender distribution was reported as male-to-female ratios with case numbers, and gender differences among groups were assessed using the χ2 test. Positive titers and positivity rates were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Age differences among the CRC, CRP, and healthy control groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA after confirming homogeneity of variance. Results were expressed as mean ± SD. Gender distribution was reported as male-to-female ratios with case numbers and compared using the χ2 test. No statistically significant differences were observed in either age or gender among the three groups (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Groups | n | Age (years) | Example (M:F) |

| Colorectal cancer primary diagnostic group | 38 | 61.97 ± 8.87 | 24:14 |

| Colorectal polyp group | 43 | 60.56 ± 9.82 | 23:20 |

| Healthy control group | 29 | 56.93 ± 7.09 | 16:13 |

| P value | 0.07 | 0.66 |

In the CRC group (n = 38), 19 cases were ANA-positive, yielding a positivity rate of 50.00%. In the CRP group (n = 43), 20 cases were ANA-positive, with a positivity rate of 46.51%. Both rates were significantly higher compared to the healthy control group (6.90%). Overall, significant differences were observed among the three groups (P < 0.05). Pairwise comparisons revealed that both the CRC and CRP groups differed significantly from the healthy control group (P < 0.05), whereas no significant difference was found between the CRC and CRP groups (P > 0.05; Tables 2 and 3).

| Groups | n | Positive | Negative | Positivity rate (%) |

| Colorectal cancer primary diagnostic group | 38 | 19 | 19 | 50.00 |

| Colorectal polyp group | 43 | 20 | 23 | 46.51 |

| Healthy control group | 29 | 2 | 27 | 6.90 |

| P value | 0.0004 |

| Comparison between groups | Colorectal cancer primary diagnostic group - colorectal polyp group | Colorectal cancer primary diagnostic group - healthy control group | Colorectal polyp group - healthy control group |

| P value | 1 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

As shown in Figure 1, ANA low-titer positivity was detected in all three groups, with low titers representing the predominant category. In the CRC group, positive titers were mainly low (1:100, 28.95%), medium (1:320, 15.79%), and high (1:1000, 5.26%). In the CRP group, titers were predominantly low (1:100, 37.21%) and medium (1:320, 11.63%). In the healthy control group, only low titers (1:100, 6.90%) were detected. Statistical comparisons of low-titer ANA positivity among the three groups showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05), whereas medium titers differed significantly (P < 0.05). High titers were observed only in the CRC group and were therefore not statistically analyzed (Table 4). Overall, ANA titers in the CRC group were higher than those in the CRP group and healthy controls.

| Groups | Low titer (1:100) | Medium titer (1:320) | High titer (1:1000) |

| Colorectal cancer primary diagnostic group | 11 | 6 | 2 |

| Colorectal polyp group | 16 | 5 | 0 |

| Healthy control group | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| P value | 1 | 0.004 | / |

In this study, ANA fluorescence patterns were relatively diverse across the three groups. In the CRC group, the predominant patterns were nuclear granular (15.79%) and cytoplasmic granular (15.79%; Figure 2A). In the CRP group, nuclear granular was the most common (20.93%), followed by homogeneous type (11.63%; Figure 2B). In the healthy control group, both nuclear granular (3.45%) and homogeneous (3.45%) patterns were observed (Figure 2C). Overall, nuclear granular was the most frequent pattern across all groups.

China has the highest annual incidence and mortality of CRC worldwide[18]. The combination of high incidence, high malignancy, and poor prognosis makes clinical management particularly challenging. CRC originates from epithelial cells of the large intestine, including both rectal and colon cancers, with adenocarcinoma being the most common pathologic type. Evidence indicates that 70%-90% of CRCs develop from adenomatous polyps through a multistep sequence: Normal intestinal mucosa, followed by small polyps, then large polyps, heterogeneous hyperplasia, carcinoma, and ultimately metastatic carcinoma. This progression typically takes 8-10 years. Furthermore, the adenoma detection rate is inversely associated with CRC mortality; each 1.0% increase in detection reduces CRC risk by 3%[18-21]. These findings highlight the importance of early CRC screening and timely preventive or therapeutic interventions. In this study, no significant difference in ANA positivity was observed between the CRC and CRP groups, but both groups showed significantly higher positivity than the healthy controls. These findings suggest that ANA testing is associated with CRC and CRP. Accordingly, patients without autoimmune diseases who test positive for ANA should undergo screening for CRP, and if polyps are detected, further CRC screening is recommended. Such an approach may help reduce CRC morbidity and mortality.

The production of tumor-related autoantibodies is primarily driven by antigenic stimulation from tumor cell destruction or immune dysregulation during tumorigenesis[24]. Once formed, these autoantibodies can activate the immune system to target tumor cells. Previous studies have suggested that autoantibodies, as products of the tumor immune response, may serve as biomarkers for early tumor detection[25]. In CRC research, several studies have examined the relationship between autoantibodies and early screening[26,27]. Whether ANA, as a group of autoanti

This study also identified a variety of ANA fluorescence patterns—such as nuclear speckled, nuclear homogeneous, nuclear nucleolar, and cytoplasmic speckled—across all groups, with nuclear speckled predominating. Both the CRP and CRC groups exhibited a relatively diverse range of patterns. However, due to the limited sample size, fluorescence pattern distributions were not statistically compared, and potential differences remain unclear. In summary, ANA is associated with the initial diagnosis of CRC and CRP. Patients with CRP who exhibit medium or high ANA titer levels should be considered at increased risk and undergo early CRC screening for timely diagnosis and intervention. Larger-scale studies are needed to validate specific ANA fluorescence patterns and clarify their clinical significance.

Most CRCs develop from the malignant transformation of CRP. In this study, ANA was detectable in both the CRP group and the CRC primary diagnosis group. ANA positivity rates were significantly higher in these groups compared with the healthy control group, indicating the potential utility of ANA testing in CRC detection. ANA titers were generally low to medium in both groups, although high titers were observed only in patients with CRC. The significant differences in ANA titers between the CRC and CRP groups further indicate a potential role for ANA testing in early CRC screening. Elevated ANA titers in patients with CRP may help identify individuals who would benefit from early CRC surveillance. Given the limited sample size, statistical analyses of ANA pattern distributions, positive titers, and positivity rates were constrained. Future studies with larger cohorts are needed to confirm these findings and establish the clinical utility of ANA testing in CRC screening and risk stratification.

| 1. | Yang W, Zheng H, Lv W, Zhu Y. Current status and prospect of immunotherapy for colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023;38:266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang M, Zhu S, Chen L, Wu Y, Ye Y, Wang G, Gui Z, Zhang C, Zhang M. Knowledge mapping of early-onset colorectal cancer from 2000 to 2022: A bibliometric analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9:e18499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baidoun F, Elshiwy K, Elkeraie Y, Merjaneh Z, Khoudari G, Sarmini MT, Gad M, Al-Husseini M, Saad A. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Recent Trends and Impact on Outcomes. Curr Drug Targets. 2021;22:998-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Yang SX, Sun ZQ, Zhou QB, Xu JZ, Chang Y, Xia KK, Wang GX, Li Z, Song JM, Zhang ZY, Yuan WT, Liu JB. Security and Radical Assessment in Open, Laparoscopic, Robotic Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Comparative Study. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:1533033818794160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | National Health Commission of the People′s Republic of China; Chinese Society of Oncology. [Chinese Protocol of Diagnosis and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer (2023 edition)]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2023;61:617-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Yang Y, Han Z, Li X, Huang A, Shi J, Gu J. Epidemiology and risk factors of colorectal cancer in China. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32:729-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Valian H, Hassan Emami M, Heidari A, Amjadi E, Fahim A, Lalezarian A, Ali Ehsan Dehkordi S, Maghool F. Trend of the polyp and adenoma detection rate by sex and age in asymptomatic average-risk and high-risk individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy, 2012-2019. Prev Med Rep. 2023;36:102468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N, Chen WQ. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134:783-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1624] [Cited by in RCA: 2008] [Article Influence: 401.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Majumdar D, Bevan R, Essam M, Nickerson C, Hungin P, Bramble M, Rutter MD. Adenoma characteristics in the English Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. Colorectal Dis. 2024;26:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ruiz-Grajales ÁE, Orozco-Puerta MM, Zheng S, H de Bock G, Correa-Cote JC, Castrillón-Martínez E. Clinical and pathological differences between early- and late-onset colorectal cancer and determinants of one-year all-cause mortality among advanced-stage patients: a retrospective cohort study in Medellín, Colombia. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2024;39:100797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kimura A, Bell-Brown A, Akinsoto N, Wood J, Peck A, Fang V, Issaka RB. Implementing an Organized Colorectal Cancer Screening Program: Lessons Learned From an Academic-Community Practice. AJPM Focus. 2024;3:100188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Heo CK, Bahk YY, Cho EW. Tumor-associated autoantibodies as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. BMB Rep. 2012;45:677-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ouyang L, Jing K, Zhu C, Wang R, Zheng P. The presence of autoantibodies as a potential prognostic biomarker for breast cancer. Scand J Immunol. 2024;e13365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nagy G, Földesi R, Csípő I, Tarr T, Szűcs G, Szántó A, Bubán T, Szekanecz Z, Papp M, Kappelmayer J, Antal-Szalmás P. A novel way to evaluate autoantibody interference in samples with mixed antinuclear antibody patterns in the HEp-2 cell based indirect immunofluorescence assay and comparison of conventional microscopic and computer-aided pattern recognition. Clin Chim Acta. 2024;553:117747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hsu SJ, Chao YC, Lin XH, Liu HH, Zhang Y, Hong WF, Chen MP, Xu X, Zhang L, Ren ZG, Du SS, Chen RX. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) status predicts immune-related adverse events in liver cancer patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2023;212:239-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fernández-Suárez A, Muñoz-Colmenero A, Ocaña-Pérez E, Fatela-Cantillo D, Domínguez-Jiménez JL, Díaz-Iglesias JM. Low positive rate of serum autoantibodies in colorectal cancer patients without systemic rheumatic diseases. Autoimmunity. 2016;49:383-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mohammed ME, Abdelhafiz K. Autoantibodies in the sera of breast cancer patients: Antinuclear and anti-double stranded DNA antibodies as example. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:341-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Damoiseaux J, Andrade LE, Fritzler MJ, Shoenfeld Y. Autoantibodies 2015: From diagnostic biomarkers toward prediction, prognosis and prevention. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:555-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Irure-Ventura J, López-Hoyos M. The Past, Present, and Future in Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA). Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Galoosian A, Dai H, Croymans D, Saccardo S, Fox CR, Goshgarian G, De Silva S, Han MA, Vangala S, May FP. Population Health Colorectal Cancer Screening Strategies in Adults Aged 45 to 49 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025;334:778-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Synytsya A, Vaňková A, Miškovičová M, Petrtýl J, Petruželka L. Ex Vivo Vibration Spectroscopic Analysis of Colorectal Polyps for the Early Diagnosis of Colorectal Carcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11:2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gauderon A, Roux-Lombard P, Spoerl D. Antinuclear Antibodies With a Homogeneous and Speckled Immunofluorescence Pattern Are Associated With Lack of Cancer While Those With a Nucleolar Pattern With the Presence of Cancer. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kumar M, Prakash G, Bal A, Kumari A, Kumar Y, Bhardwaj R, Malhotra P, Minz RW. Impact of Anti-nuclear Antibody Seropositivity on Clinicopathological Parameters, Treatment Response, and Survival in Lymphoma Patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2024;25:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ke CH, Chiu YH, Huang KC, Lin CS. Exposure of Immunogenic Tumor Antigens in Surrendered Immunity and the Significance of Autologous Tumor Cell-Based Vaccination in Precision Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | de Jonge H, Iamele L, Maggi M, Pessino G, Scotti C. Anti-Cancer Auto-Antibodies: Roles, Applications and Open Issues. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tardito S, Matis S, Zocchi MR, Benelli R, Poggi A. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Targeting in Colorectal Carcinoma: Antibodies and Patient-Derived Organoids as a Smart Model to Study Therapy Resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:7131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ma H, Murphy C, Loscher CE, O'Kennedy R. Autoantibodies - enemies, and/or potential allies? Front Immunol. 2022;13:953726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/