Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111829

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: October 20, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 168 Days and 15.2 Hours

Early risk stratification in severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) remains challenging with traditional scoring systems overlooking etiological heterogeneity, particu

To develop and evaluate a machine learning (ML) model combining intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) and procalcitonin (PCT) for SAP prognosis and eva

We retrospectively analyzed 245 patients with pancreatitis (98 patients with SAP). An ML model using 24-h peak IAP and PCT levels was used to predict 28-day mortality. Propensity score matching was used to compare IAP-PCT-guided ma

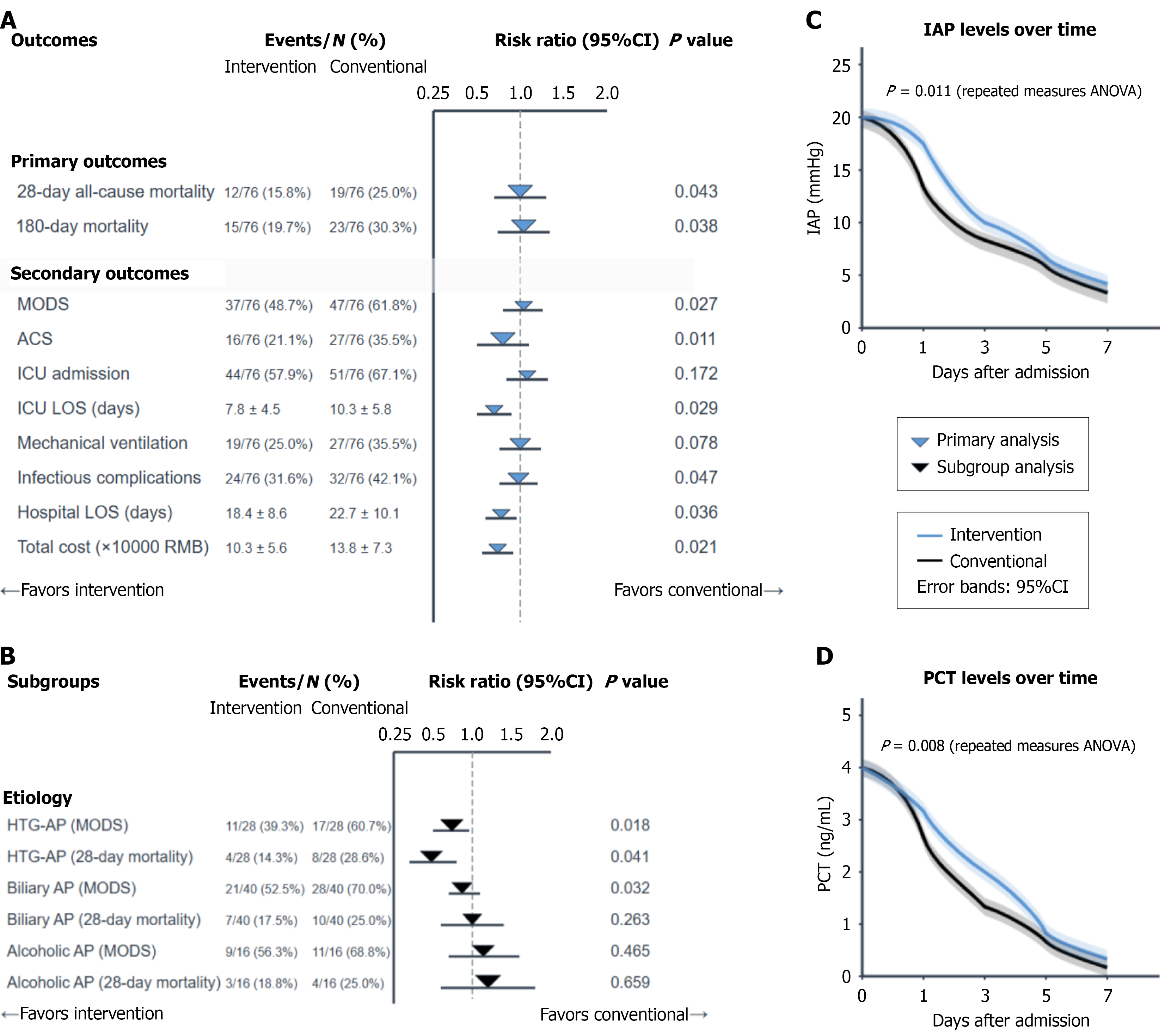

The ML-IAP-PCT model outperformed the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score (area under the curve: 0.853 vs 0.801, P = 0.044) and Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis score. IAP-PCT-guided management was associated with lower mortality (15.8% vs 25.0%, P = 0.043) and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (48.7% vs 61.8%, P = 0.027) rates. Patients with HTG-AP showed the greatest benefit (multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: 39.3% vs 60.7%, P = 0.018).

ML-optimized IAP-PCT monitoring provides superior prognostic accuracy and guides management associated with improved outcomes, especially in patients with HTG-AP. Prospective validation is needed to establish causality for this etiology-stratified approach.

Core Tip: By integrating intra-abdominal pressure and procalcitonin using a machine learning algorithm, this study established a superior prognostic model for severe acute pancreatitis (AP). The core innovation, however, lies in revealing profound etiological heterogeneity. We demonstrated that the correlation between intra-abdominal pressure and procalcitonin and the benefits of guided management are most significant in patients with hypertriglyceridemic AP. These findings advocate for a shift from a uniform approach to an etiology-stratified precision medicine strategy, particularly for the high-risk hypertriglyceridemic AP subgroup.

- Citation: Zhao JF, Jin GX, Wang Y, Huang XM. Intra-abdominal pressure and procalcitonin for prognosis in patients with severe acute pancreatitis: An etiology-based analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 111829

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/111829.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111829

Early risk stratification for severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is critical for improving its high mortality rate of 15%-30%[1,2], yet traditional scoring systems such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score are often insufficient for early decision-making. These static scores lack timeliness and sensitivity to specific pathophysiological events, such as intra-abdominal hypertension, creating an urgent need for more dynamic biomarkers to guide timely intervention[3-7].

Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) and procalcitonin (PCT) are two such promising markers. Elevated IAP, a common complication, reflects local mechanical stress and contributes to poor prognosis by compromising the intestinal barrier and organ perfusion[8,9]. PCT is an established biomarker for systemic inflammation and infection that increases rapidly in early SAP[10,11]. A key pathophysiological connection is as follows: IAP-induced intestinal ischemia can lead to bacterial translocation, subsequently triggering PCT release and amplifying the inflammatory cascade[12]. Combined monitoring of IAP and PCT may therefore offer a more robust assessment of the pancreatic-intestinal-inflammatory axis for early risk warning.

Crucially, the one-size-fits-all approach of most SAP risk models neglects etiological heterogeneity. Hypertriglyceridemic acute pancreatitis (HTG-AP) in particular is an increasingly prevalent and aggressive subtype[13,14]. Its unique lipotoxic mechanisms may distinctly impact IAP elevation and the PCT response, yet this is often overlooked[15-17]. Addressing this etiological heterogeneity is essential for developing precision treatment strategies.

Therefore, this study aimed to construct and validate a machine learning (ML)-based risk model using early IAP and PCT monitoring to predict the prognosis of SAP patients. We also sought to evaluate the efficacy of a risk-stratified management strategy guided by this model. We hypothesized that the combined IAP-PCT model would outperform traditional scores and that its clinical utility would be most pronounced in patients with HTG-AP, laying the foundation for an etiology-based approach to precision management in SAP.

This was a retrospective comparative effectiveness study with internal validation that used data from December 1, 2021 to December 1, 2024. The study protocol was approved by our hospital’s Medical Ethics Committee and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement[18]. The requirement for written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design and data anonymization.

We included patients aged ≥ 18 years who met the diagnostic criteria of the 2021 Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Pancreatitis[19] with at least one IAP and PCT measurement completed within 24 h of admission. SAP was defined according to the 2012 revised Atlanta classification as persistent organ failure (modified Marshall score ≥ 2) lasting > 48 h[20]. The exclusion criteria included active nonpancreatic infection, end-stage disease, chronic pancreatitis, or prior pancreatic surgery, conditions affecting intravesical pressure measurement, antibiotic use within 72 h before admission, a history of bowel resection, or death within 24 h of admission.

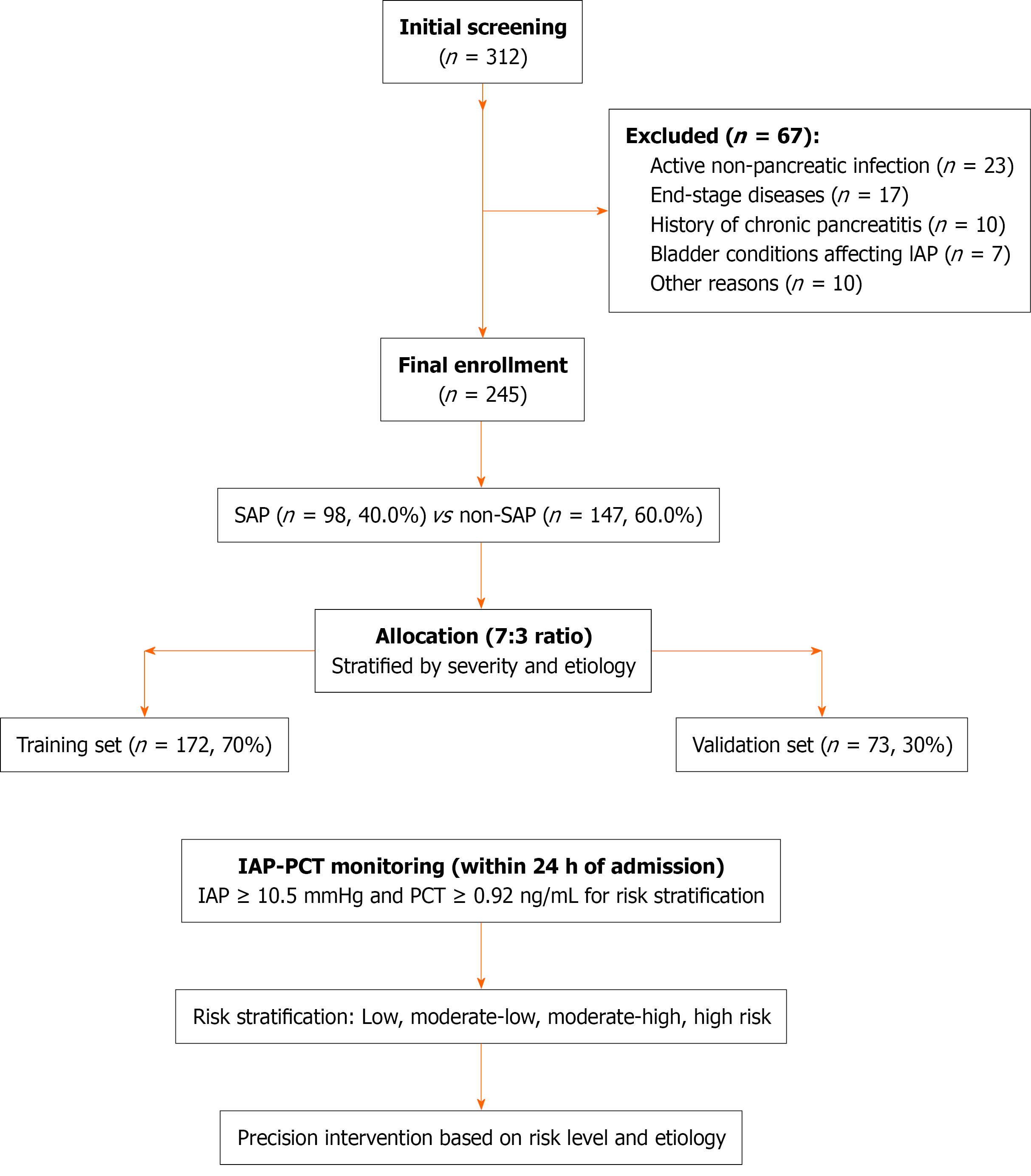

The primary outcome was 28-day all-cause mortality. On the basis of an expected mortality reduction from 25% to 15% in the intervention group with α = 0.05 and β = 0.2 (80% power), a sample size of 49 patients with SAP per group was needed. To account for subgroup analyses and potential data omissions, we aimed for a total of 245 patients (including approximately 98 patients with SAP). Patients were divided into training (n = 172) and validation (n = 73) sets (7:3 ratio) via stratified random sampling on the basis of disease severity and etiology.

The median symptom-to-admission time was 8.5 h (interquartile range: 4-16 h) with 89% of patients admitted within 24 h of onset. Standard intravesical pressure was measured every 8 h according to the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome 2013 guidelines[21]. Venous blood for PCT was collected upon admission and re-examined as needed (typically every 12-24 h). The highest IAP and PCT values within the first 24 h were recorded for analysis. For quantitative PCT detection a Roche Diagnostics Cobas e601 electrochemiluminescence immunoassay was used.

All patients received standardized basic treatment per the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Pancreatitis (2021 version)[19]. In this retrospective analysis patients were categorized into an IAP-PCT-guided group or a conventional management group. IAP-PCT-guided management was defined by a risk-stratified protocol with increasing intensity (Supplementary Tables 1-3).

Low risk (IAP < 10.5 mmHg and PCT < 0.92 ng/mL): Standard monitoring and conventional fluid therapy.

Moderate-low risk (one marker elevated): Restrictive fluid strategy and albumin maintenance.

Moderate-high risk (both markers elevated): Intensive monitoring, empirical antibiotics, and nasogastric decompression.

High risk (IAP ≥ 15 mmHg and PCT ≥ 3.0 ng/mL): Intensive care unit care, mechanical ventilation optimization, and aggressive management of intra-abdominal hypertension.

Statistical analysis was performed via the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (v25.0+), R (v4.2.0+), and Python (v3.8+). We used t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, or χ² tests for baseline comparisons. The prediction model was constructed via logistic regression and ML algorithms (e.g., random forest)[22] and evaluated via the area under the curve (AUC) (DeLong test)[23], calibration curves, and decision curve analysis (DCA). Propensity score methods (propensity score matching, inverse probability treatment weighting) were used to control for confounding bias in outcome comparisons[24]. Key subgroup analyses (by etiology, age, severity) and interaction tests were used to explore heterogeneity. Subgroups with n < 30 were analyzed descriptively only. Post hoc power analysis confirmed adequate power (> 80%) for primary outcomes but limited power for subgroup analyses.

During the study period (December 1, 2021 to December 1, 2024), 312 patients were screened, and 245 were ultimately included. Among these patients 98 patients (40.0%) had SAP as defined by the revised Atlanta classification. The cohort’s mean age was 48.7 ± 15.2 years with 58.4% males. The primary etiologies were biliary (50.2%, n = 123), HTG (21.6%, n = 53), and alcoholic (18.8%, n = 46). Patients were randomly assigned to training (n = 172) or validation (n = 73) sets at a 7:3 ratio with well-balanced baseline characteristics (all P > 0.05) (Table 1, Figure 1).

| Characteristics | Total (n = 245) | Training set (n = 172) | Validation set (n = 73) | P value |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 48.7 ± 15.2 | 49.5 ± 15.3 | 47.3 ± 14.8 | 0.287 |

| Male sex | 143 (58.4) | 97 (56.4) | 46 (63.0) | 0.327 |

| Body mass index (kg/m²), mean ± SD | 25.3 ± 4.1 | 25.5 ± 4.3 | 24.9 ± 3.8 | 0.302 |

| Etiology | ||||

| Biliary | 123 (50.2) | 89 (51.7) | 34 (46.6) | 0.452 |

| Hypertriglyceridemic | 53 (21.6) | 35 (20.3) | 18 (24.7) | 0.437 |

| Alcoholic | 46 (18.8) | 34 (19.8) | 12 (16.4) | 0.536 |

| Others/idiopathic | 23 (9.4) | 14 (8.1) | 9 (12.3) | 0.298 |

| Disease severity scores, mean ± SD | ||||

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II | 9.1 ± 3.5 | 9.3 ± 3.6 | 8.8 ± 3.3 | 0.318 |

| Ranson | 3.2 ± 1.8 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 3.0 ± 1.6 | 0.245 |

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 2.9 ± 2.3 | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 0.142 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| WBC (× 109/L), mean ± SD | 15.3 ± 4.7 | 15.5 ± 4.9 | 14.8 ± 4.3 | 0.293 |

| Glucose (mmol/L), mean ± SD | 9.7 ± 4.3 | 9.9 ± 4.5 | 9.3 ± 3.9 | 0.324 |

| Serum amylase (U/L), mean ± SD | 893 ± 567 | 914 ± 583 | 845 ± 526 | 0.381 |

| Triglycerides in mmol/L, median (IQR) | 3.5 (1.7-9.3) | 3.6 (1.8-9.4) | 3.3 (1.5-8.9) | 0.415 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), mean ± SD | 138.2 ± 92.7 | 141.3 ± 94.5 | 131.2 ± 88.4 | 0.428 |

| Interleukin-6 in pg/mL, median (IQR) | 149.5 (76.3-257.8) | 153.7 (79.2-264.3) | 142.1 (71.5-241.6) | 0.367 |

| Intra-abdominal pressure (mmHg), mean ± SD | 12.6 ± 4.7 | 12.8 ± 4.8 | 12.1 ± 4.4 | 0.294 |

| Procalcitonin in ng/mL, median (IQR) | 1.63 (0.68-3.47) | 1.71 (0.72-3.52) | 1.48 (0.61-3.31) | 0.243 |

| Severe acute pancreatitis | 98 (40.0) | 71 (41.3) | 27 (37.0) | 0.527 |

Patients with HTG-AP demonstrated significantly greater baseline severity (APACHE II score: 10.5 ± 3.8 vs 8.7 ± 3.2 for patients with biliary disease vs 9.1 ± 3.5 for patients with alcoholic disease, P = 0.018) and the highest SAP rate (52.8% vs 36.6% vs 34.8%, P = 0.046). The median symptom-to-admission time was 8.5 h (interquartile range: 4-16 h) with 89% admitted within 24 h of onset. Sensitivity analysis excluding patients who were late admission (> 24 h) revealed consistent model performance (AUC: 0.846 vs 0.853, P = 0.712).

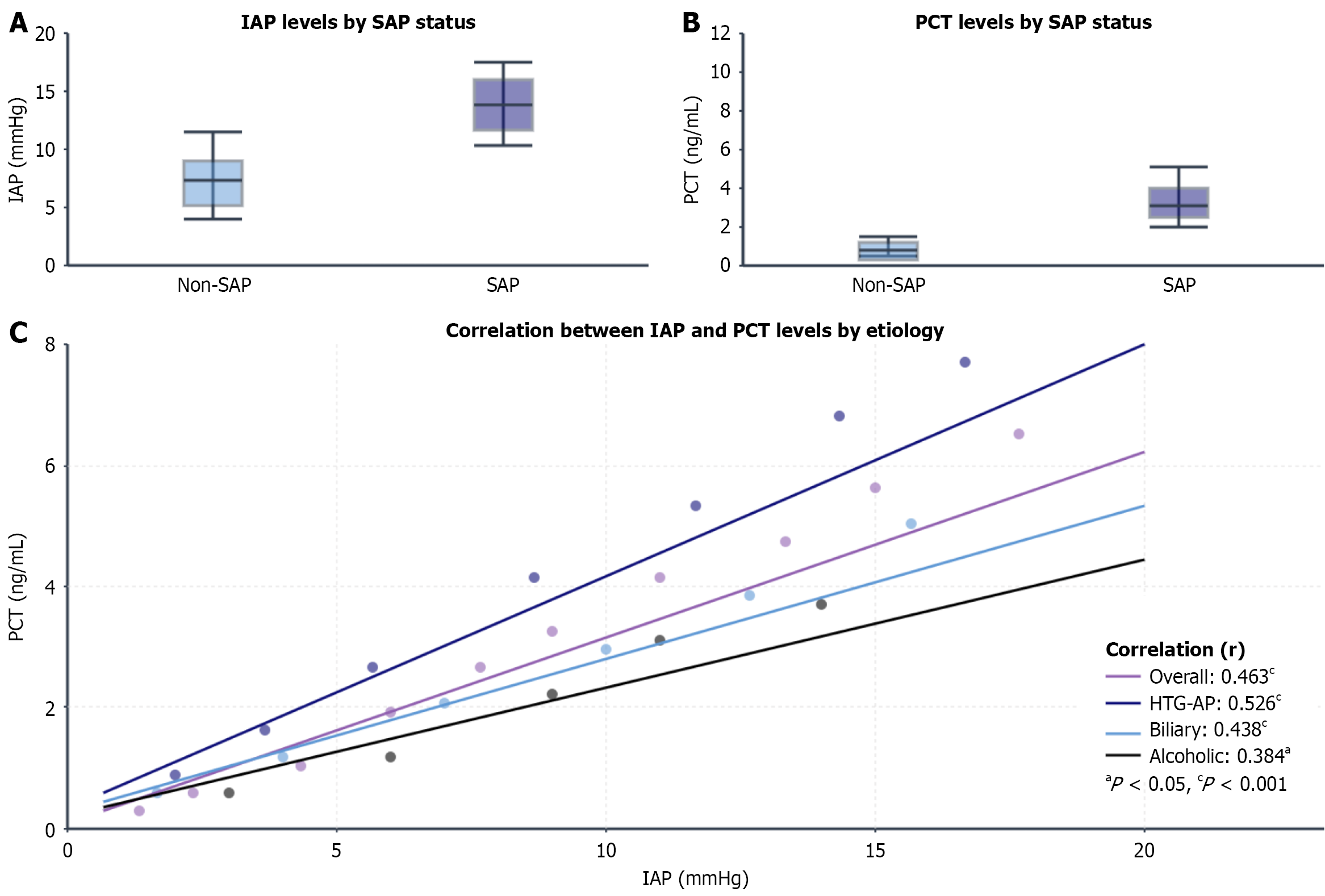

Within 24 h of admission, peak IAP levels were significantly higher in patients with SAP than in patients without SAP [15.8 (13.5-18.9) mmHg vs 9.1 (7.2-11.0) mmHg, P < 0.001] as were PCT levels [3.62 (1.85-7.28) ng/mL vs 0.95 (0.42–1.76) ng/mL, P < 0.001]. The overall IAP-PCT correlation was moderate [Spearman’s r = 0.463, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.367-0.549, P < 0.001) and remained significant after adjusting for baseline severity (partial r = 0.412, P < 0.001).

Stratification by etiology revealed significant heterogeneity in the IAP-PCT correlation: The strongest correlation was detected in patients with HTG-AP (r = 0.526, P < 0.001), the moderate correlation was detected in patients with biliary AP (r = 0.438, P < 0.001), and the weakest correlation was detected in patients with alcoholic AP (r = 0.384, P = 0.028). The interaction between etiology and IAP was significant (interaction P = 0.007) with the IAP-PCT correlation remaining strong in patients with HTG-AP even after severity adjustment (partial r = 0.487, P < 0.001) (Figure 2).

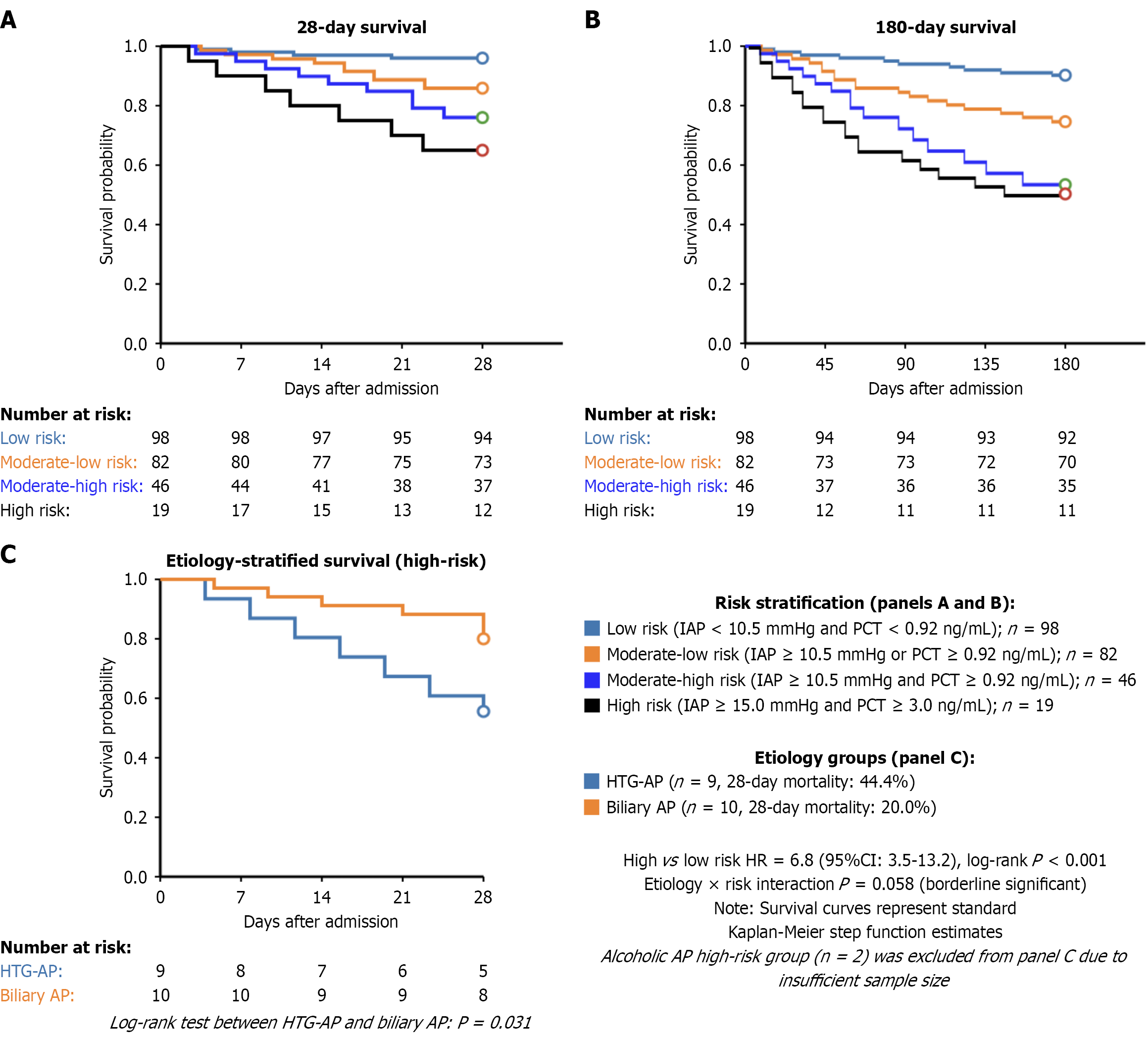

Patients were stratified into four risk groups according to optimal thresholds (IAP ≥ 10.5 mmHg, PCT ≥ 0.92 ng/mL): (1) Low (40.0%); (2) Moderate-low (33.5%); (3) Moderate-high (18.8%); and (4) High (7.7%). A clear gradient was observed from low to high risk for all major outcomes: (1) SAP incidence (13.3%-94.7%); (2) 28-day mortality (4.1%-36.8%); (3) Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (8.2%-78.9%); and (4) Abdominal compartment syndrome (2.0%-57.9%), all P < 0.001. Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed progressively worse survival with higher risk stratification (log-rank P < 0.001) (Table 2, Figure 3).

| Clinical outcomes | Low risk (n = 98) | Moderate-low risk (n = 82) | Moderate-high risk (n = 46) | High risk (n = 19) | P value |

| Severe AP | 13 (13.3) | 31 (37.8) | 36 (78.3) | 18 (94.7) | < 0.001 |

| 28-day all-cause mortality | 4 (4.1) | 9 (11.0) | 9 (19.6) | 7 (36.8) | < 0.001 |

| 180-day mortality | 6 (6.1) | 12 (14.6) | 11 (23.9) | 8 (42.1) | < 0.001 |

| MODS | 8 (8.2) | 21 (25.6) | 24 (52.2) | 15 (78.9) | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal compartment syndrome | 2 (2.0) | 7 (8.5) | 11 (23.9) | 11 (57.9) | < 0.001 |

| ICU admission | 11 (11.2) | 31 (37.8) | 33 (71.7) | 18 (94.7) | < 0.001 |

| ICU LOS (days), mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 6.7 ± 3.9 | 9.9 ± 5.4 | 16.3 ± 8.7 | < 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3 (3.1) | 11 (13.4) | 17 (37.0) | 13 (68.4) | < 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation duration (days), mean ± SD | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 2.3 | 6.9 ± 3.9 | 10.8 ± 5.7 | < 0.001 |

| Infectious complications | 7 (7.1) | 17 (20.7) | 20 (43.5) | 13 (68.4) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital LOS (days), mean ± SD | 9.7 ± 3.6 | 16.3 ± 6.2 | 23.5 ± 9.4 | 29.7 ± 13.2 | < 0.001 |

| Total cost (× 10000 RMB), mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 1.9 | 8.1 ± 3.5 | 14.9 ± 6.7 | 23.8 ± 11.3 | < 0.001 |

| Stratified by etiology | |||||

| Hypertriglyceridemic AP patients (n = 53) | |||||

| 28-day mortality | 1/12 (8.3) | 3/17 (17.6) | 4/15 (26.7) | 4/9 (44.4) | 0.038 |

| MODS | 2/12 (16.7) | 7/17 (41.2) | 10/15 (66.7) | 8/9 (88.9) | 0.003 |

| Biliary AP (n = 123) | |||||

| 28-day mortality | 2/53 (3.8) | 4/39 (10.3) | 3/21 (14.3) | 2/10 (20.0) | 0.014 |

| MODS | 4/53 (7.5) | 11/39 (28.2) | 9/21 (42.9) | 6/10 (60.0) | < 0.001 |

| Alcoholic AP (n = 46) | |||||

| 28-day mortality | 1/21 (4.8) | 2/16 (12.5) | 2/7 (28.6) | 1/2 (50.0) | 0.113 |

| MODS | 2/21 (9.5) | 5/16 (31.3) | 3/7 (42.9) | 1/2 (50.0) | 0.046 |

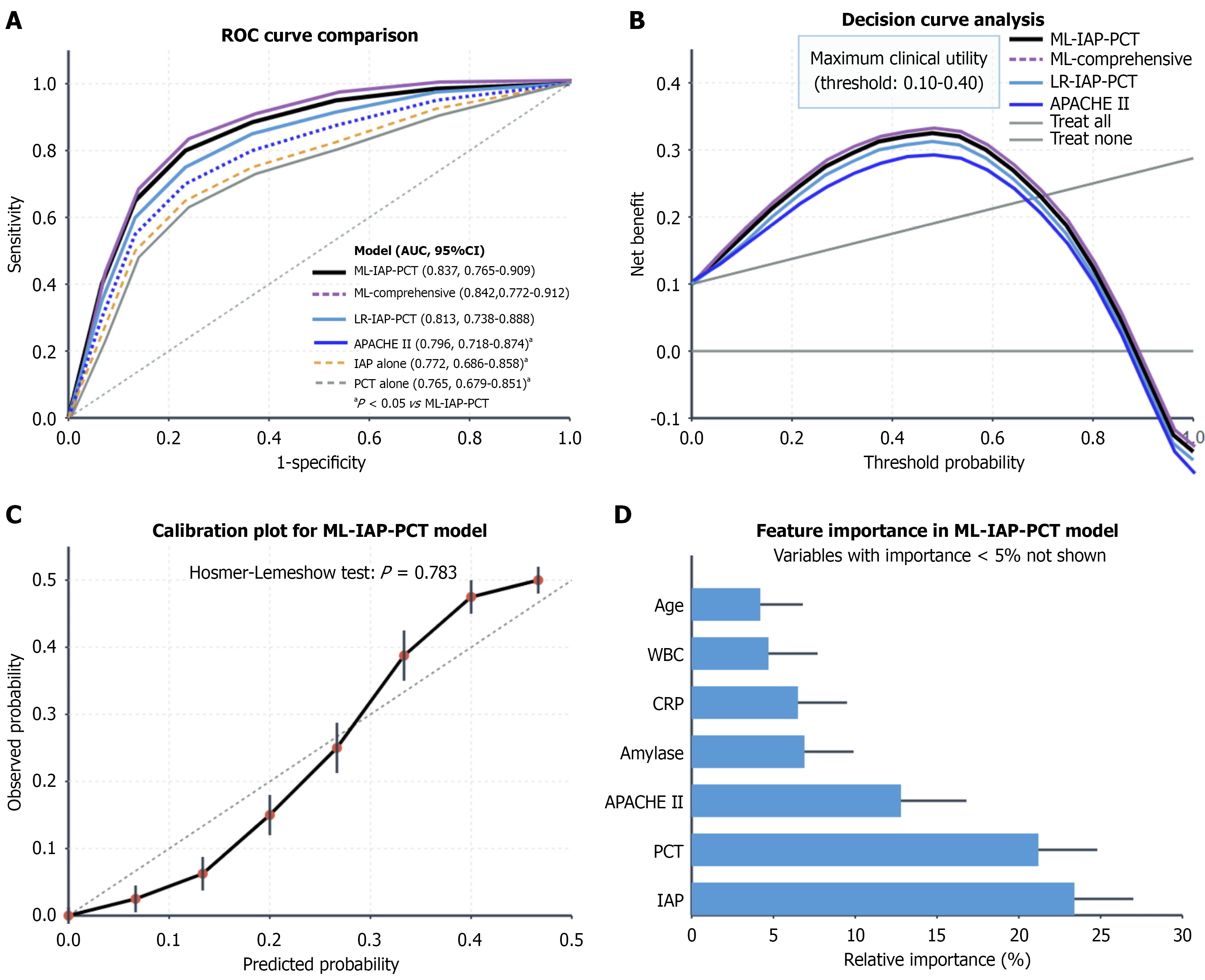

The ML-IAP-PCT model achieved superior discrimination for 28-day mortality (AUC = 0.853, 95%CI: 0.786-0.920), significantly outperforming the APACHE II score (AUC = 0.801, P = 0.044), Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis score (AUC = 0.798, P = 0.032), and single markers (IAP alone: AUC = 0.795, P = 0.018; PCT alone: AUC = 0.787, P = 0.012). The model demonstrated good calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow P = 0.783) with a sensitivity of 82.1% and specificity of 78.5% at the optimal cutoff. DCA revealed the greatest net benefit across threshold probabilities of 10%-40%. Among the etiologies HTG-AP had the highest predictive performance (AUC = 0.887), followed by biliary AP (0.827) and alcoholic AP (0.789) (Table 3, Figure 4).

| Prediction models | Area under the curve (95%CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) | P value |

| IAP model alone | 0.772 (0.686-0.858) | 71.7 | 73.8 | 47.3 | 88.9 | 0.008a |

| PCT model alone | 0.765 (0.679-0.851) | 68.9 | 72.6 | 46.1 | 87.3 | 0.005a |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score | 0.796 (0.718-0.874) | 75.1 | 70.3 | 46.8 | 89.1 | 0.041a |

| Logistic regression IAP-PCT model | 0.813 (0.738-0.888) | 76.8 | 74.2 | 50.3 | 90.3 | 0.087 |

| ML-IAP-PCT model | 0.837 (0.765-0.909) | 78.6 | 76.5 | 53.1 | 91.4 | Reference |

| ML-comprehensive model1 | 0.842 (0.772-0.912) | 79.3 | 77.2 | 54.5 | 91.7 | 0.386 |

After 1:1 propensity score matching (n = 76 per group, standardized mean difference < 0.1 for all covariates), IAP-PCT-guided management was associated with lower 28-day mortality (15.8% vs 25.0%, relative risk = 0.63, 95%CI: 0.33-0.98, P = 0.043) and MODS incidence (48.7% vs 61.8%, relative risk = 0.79, P = 0.027) than conventional care was. Secondary outcomes, including intensive care unit length of stay (7.8 ± 4.5 days vs 10.3 ± 5.8 days, P = 0.029) and total costs (¥103000 ± ¥56000 vs ¥138000 ± ¥73000, P = 0.021) also favored guided management.

Subgroup analysis revealed the greatest benefit in patients with HTG-AP (28-day mortality: 14.3% vs 28.6%, P = 0.041; MODS: 39.3% vs 60.7%, P = 0.018). Note that subgroups with n < 30 were analyzed descriptively only; post hoc power analysis confirmed > 80% power for primary outcomes but limited power for some subgroup analyses (Table 4, Figure 5).

| Outcome measures | Intervention group (n = 76) | Conventional group (n = 76) | Relative risk/mean difference (95%CI) | P value |

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| 28-day all-cause mortality | 12 (15.8) | 19 (25.0) | 0.63 (0.33-0.98) | 0.043 |

| 180-day mortality | 15 (19.7) | 23 (30.3) | 0.65 (0.37-0.92) | 0.038 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| MODS | 37 (48.7) | 47 (61.8) | 0.79 (0.58-0.96) | 0.027 |

| Abdominal compartment syndrome | 16 (21.1) | 27 (35.5) | 0.59 (0.35-0.87) | 0.011 |

| ICU admission | 44 (57.9) | 51 (67.1) | 0.86 (0.67-1.03) | 0.172 |

| ICU LOS (days), mean ± SD | 7.8 ± 4.5 | 10.3 ± 5.8 | -2.5 (-4.1 to -0.9) | 0.029 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 19 (25.0) | 27 (35.5) | 0.70 (0.43-1.05) | 0.078 |

| Mechanical ventilation duration (days), mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 3.1 | 6.9 ± 4.0 | -2.3 (-3.4 to -1.2) | 0.003 |

| Infectious complications | 24 (31.6) | 32 (42.1) | 0.75 (0.49-0.98) | 0.047 |

| Hospital LOS (days), mean ± SD | 18.4 ± 8.6 | 22.7 ± 10.1 | -4.3 (-7.1 to -1.5) | 0.036 |

| Total cost (× 10000 RMB), mean ± SD | 10.3 ± 5.6 | 13.8 ± 7.3 | -3.5 (-5.6 to -1.4) | 0.021 |

| Subgroup analysis | ||||

| Hypertriglyceridemic AP subgroup (n = 28 pairs) | ||||

| MODS | 11 (39.3) | 17 (60.7) | 0.65 (0.38-0.94) | 0.018 |

| 28-day mortality | 4 (14.3) | 8 (28.6) | 0.50 (0.22-0.99) | 0.041 |

| Biliary AP subgroup (n = 40 pairs) | ||||

| MODS | 21 (52.5) | 28 (70.0) | 0.75 (0.52-0.98) | 0.032 |

| 28-day mortality | 7 (17.5) | 10 (25.0) | 0.70 (0.37-1.33) | 0.263 |

| Alcoholic AP subgroup (n = 16 pairs) | ||||

| MODS | 9 (56.3) | 11 (68.8) | 0.82 (0.47-1.43) | 0.465 |

| 28-day mortality | 3 (18.8) | 4 (25.0) | 0.75 (0.21-2.65) | 0.659 |

| Adjusted analysis | ||||

| 28-day mortality, adjusted OR1 | - | - | 0.59 (0.29-0.97) | 0.038 |

| MODS, adjusted OR1 | - | - | 0.71 (0.41-0.93) | 0.023 |

This study provided key evidence that an etiology-aware, biomarker-guided strategy can significantly enhance early risk stratification in patients with SAP. Our central finding was that a ML model integrating IAP and PCT not only outperformed traditional scoring systems but also represented a management approach associated with improved clinical outcomes. Crucially, this work challenged the conventional one-size-fits-all paradigm by demonstrating that these associations are most profound in patients with HTG-AP, highlighting a new direction for precision medicine in this challenging disease.

The core value of this study lies in confirming the incremental benefit of early combined IAP and PCT monitoring for SAP risk assessment. Our ML-IAP-PCT model outperformed single biomarkers and traditional scores across multiple dimensions, including the AUC, net reclassification index, and integrated discrimination index. Notably, it also demonstrated superior discrimination compared with the widely used AP-specific Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis score (AUC = 0.853 vs 0.798, P = 0.032), confirming its potential as a more robust tool for early clinical decision-making. Its good calibration and clinical net benefit demonstrated by DCA suggested that it can provide a more precise early warning, which is crucial for capturing the golden window for intervention in patients with SAP[25,26]. This finding aligns with the recent concept that pancreatitis assessment must move beyond static, single-parameter evaluation toward multidimensional, dynamic monitoring[27].

Furthermore, our preliminary evidence suggests that stratified management based on this model was associated with improved clinical outcomes. After controlling for confounding factors through propensity score matching, patients in the IAP-PCT-guided management group had significantly better key outcomes (28-day mortality: 15.8% vs 25.0%, P = 0.043; MODS incidence: 48.7% vs 61.8%, P = 0.027). While these associations require prospective validation to establish causality, they provide valuable reference evidence for transitioning SAP management from empirical to precision-stratified approaches that is consistent with the latest guidelines emphasizing early identification and targeted intervention[28].

The positive correlation between IAP and PCT in early SAP can be explained through the intestinal barrier damage-bacterial/endotoxin translocation-systemic inflammation axis[29,30]. While the direct statistical correlation between IAP and PCT in our cohort was moderate (r = 0.463), its clinical significance is underscored by our finding that the combined model vastly outperformed either marker alone. These findings demonstrated that IAP and PCT provide complementary rather than redundant pathophysiological information, making their combined monitoring essential for comprehensive risk assessment.

The prominence of this correlation and intervention benefit in patients with HTG-AP suggests more dramatic pathophysiological changes in this subgroup. The cytotoxic effects of free fatty acids may directly damage the pancreas and vascular endothelium while exacerbating intestinal barrier disruption, leading to greater bacterial translocation and higher PCT levels at similar IAP levels[31,32]. This unique pathology likely contributes to the stronger IAP-PCT association (r = 0.526 in HTG-AP vs 0.438 in biliary AP) and better response to early intervention observed in patients with HTG-AP. Our findings that patients with HTG-AP had the highest SAP rate (52.8%) and greatest benefit from IAP-PCT-guided management (MODS reduction: 39.3% vs 60.7%, P = 0.018) underscore the importance of etiology-specific approaches[33].

If validated through prospective studies, the IAP-PCT combined monitoring and risk stratification model could be transformed into a practical clinical tool. The monitoring methods are routine and accessible with risk stratification processes easily standardized. The model could be integrated into hospital information systems for real-time risk assessment while stratified management protocols could be incorporated into clinical pathways[34]. Preliminary cost-effectiveness analysis revealed favorable ICERs (¥45700/quality adjusted life year), particularly in patients with HTG-AP (¥36200/ quality adjusted life year), suggesting potential economic value alongside clinical benefits.

This study had important methodological limitations inherent to its design. First, as a retrospective comparative effectiveness study, its aim was to evaluate outcomes in existing clinical practice rather than to establish definitive causal relationships. Causal inference is therefore limited. The selection of management strategies was not randomly assigned but rather based on physicians’ judgments, creating a risk of selection bias and unmeasured confounding that despite propensity score matching could not be fully eliminated. Second, the single-center design and lack of external validation limit generalizability beyond our institution; multicenter validation is essential before clinical implementation. Additionally, the statistical power for some subgroup analyses was limited. Given these limitations, our findings should be viewed as generating hypothetical evidence that requires validation through prospective randomized controlled trials.

Future research should focus on: (1) Multicenter prospective randomized controlled trials to verify the causal effects of IAP-PCT-guided management; (2) The exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying the IAP-PCT connection in different SAP etiologies; (3) The development of simplified clinical scoring systems and point-of-care tools; and (4) Long-term outcome assessment, including pancreatic function recovery and quality of life. We are currently planning a multicenter RCT with predetermined IAP-PCT-based protocols to validate these findings and establish their true clinical utility.

An ML-optimized model combining early IAP and PCT accurately predicted the prognosis of patients with SAP, outperforming traditional scores. The model provided guidance for a management strategy associated with lower mortality and complication rates with this beneficial association being most significant in patients with HTG-AP. Owing to their unique lipotoxic pathophysiology, these patients are prime candidates for this etiology-stratified approach. Prospective validation is now essential to translate these promising findings into clinical practice.

| 1. | de-Madaria E, Buxbaum JL, Maisonneuve P, García García de Paredes A, Zapater P, Guilabert L, Vaillo-Rocamora A, Rodríguez-Gandía MÁ, Donate-Ortega J, Lozada-Hernández EE, Collazo Moreno AJR, Lira-Aguilar A, Llovet LP, Mehta R, Tandel R, Navarro P, Sánchez-Pardo AM, Sánchez-Marin C, Cobreros M, Fernández-Cabrera I, Casals-Seoane F, Casas Deza D, Lauret-Braña E, Martí-Marqués E, Camacho-Montaño LM, Ubieto V, Ganuza M, Bolado F; ERICA Consortium. Aggressive or Moderate Fluid Resuscitation in Acute Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:989-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Lee PJ, Papachristou GI. New insights into acute pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:479-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 84.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schepers NJ, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Ahmed Ali U, Bollen TL, Gooszen HG, van Santvoort HC, Bruno MJ; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Impact of characteristics of organ failure and infected necrosis on mortality in necrotising pancreatitis. Gut. 2019;68:1044-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shi N, Liu T, de la Iglesia-Garcia D, Deng L, Jin T, Lan L, Zhu P, Hu W, Zhou Z, Singh V, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Windsor J, Huang W, Xia Q, Sutton R. Duration of organ failure impacts mortality in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2020;69:604-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Garg PK, Singh VP. Organ Failure Due to Systemic Injury in Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:2008-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 62.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X, Tabak Y, Conwell DL, Banks PA. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1698-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 573] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 7. | Tenner S, Vege SS, Sheth SG, Sauer B, Yang A, Conwell DL, Yadlapati RH, Gardner TB. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:419-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 104.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nasa P, Wise RD, Smit M, Acosta S, D'Amours S, Beaubien-Souligny W, Bodnar Z, Coccolini F, Dangayach NS, Dabrowski W, Duchesne J, Ejike JC, Augustin G, De Keulenaer B, Kirkpatrick AW, Khanna AK, Kimball E, Koratala A, Lee RK, Leppaniemi A, Lerma EV, Marmolejo V, Meraz-Munoz A, Myatra SN, Niven D, Olvera C, Ordoñez C, Petro C, Pereira BM, Ronco C, Regli A, Roberts DJ, Rola P, Rosen M, Shrestha GS, Sugrue M, Velez JCQ, Wald R, De Waele J, Reintam Blaser A, Malbrain MLNG. International cross-sectional survey on current and updated definitions of intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. World J Emerg Surg. 2024;19:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zarnescu NO, Dumitrascu I, Zarnescu EC, Costea R. Abdominal Compartment Syndrome in Acute Pancreatitis: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;13:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tarján D, Szalai E, Lipp M, Verbói M, Kói T, Erőss B, Teutsch B, Faluhelyi N, Hegyi P, Mikó A. Persistently High Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein Are Good Predictors of Infection in Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alberti P, Pando E, Mata R, Cirera A, Fernandes N, Hidalgo N, Gomez-Jurado MJ, Vidal L, Dopazo C, Blanco L, Gómez C, Caralt M, Balsells J, Charco R. The role of procalcitonin as a prognostic factor for acute cholangitis and infections in acute pancreatitis: a prospective cohort study from a European single center. HPB (Oxford). 2022;24:875-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Agarwal S, Goswami P, Poudel S, Gunjan D, Singh N, Yadav R, Kumar U, Pandey G, Saraya A. Acute pancreatitis is characterized by generalized intestinal barrier dysfunction in early stage. Pancreatology. 2023;23:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | de Pretis N, Amodio A, Frulloni L. Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical management. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jin M, Bai X, Chen X, Zhang H, Lu B, Li Y, Lai Y, Qian J, Yang H. A 16-year trend of etiology in acute pancreatitis: The increasing proportion of hypertriglyceridemia-associated acute pancreatitis and its adverse effect on prognosis. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13:947-953.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tung YC, Hsiao FC, Lin CP, Ho CT, Hsu TJ, Chiang HY, Chu PH. High Triglyceride Variability Increases the Risk of First Attack of Acute Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:1080-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kiss L, Fűr G, Pisipati S, Rajalingamgari P, Ewald N, Singh V, Rakonczay Z Jr. Mechanisms linking hypertriglyceridemia to acute pancreatitis. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2023;237:e13916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang Y, Dai GF, Xiao WB, Shi JS, Lin BW, Lin JD, Xiao XJ. Effects of continuous venous-venous hemofiltration with or without hemoperfusion on patients with hypertriglyceride acute pancreatitis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2025;49:102572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Yarmolinsky J, Davies NM, Swanson SA, VanderWeele TJ, Higgins JPT, Timpson NJ, Dimou N, Langenberg C, Golub RM, Loder EW, Gallo V, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Davey Smith G, Egger M, Richards JB. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization: The STROBE-MR Statement. JAMA. 2021;326:1614-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 828] [Cited by in RCA: 2661] [Article Influence: 532.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chinese Pancreatic Surgery Association; Chinese Society of Surgery; Chinese Medical Association. [Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis in China (2021)]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2021;59:578-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4722] [Article Influence: 363.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 21. | Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, De Waele J, Jaeschke R, Malbrain ML, De Keulenaer B, Duchesne J, Bjorck M, Leppaniemi A, Ejike JC, Sugrue M, Cheatham M, Ivatury R, Ball CG, Reintam Blaser A, Regli A, Balogh ZJ, D'Amours S, Debergh D, Kaplan M, Kimball E, Olvera C; Pediatric Guidelines Sub-Committee for the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1190-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 841] [Cited by in RCA: 896] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 22. | Thapa R, Iqbal Z, Garikipati A, Siefkas A, Hoffman J, Mao Q, Das R. Early prediction of severe acute pancreatitis using machine learning. Pancreatology. 2022;22:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Qiu L, Sun RQ, Jia RR, Ma XY, Cheng L, Tang MC, Zhao Y. Comparison of Existing Clinical Scoring Systems in Predicting Severity and Prognoses of Hyperlipidemic Acute Pancreatitis in Chinese Patients: A Retrospective Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 24. | Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6382] [Cited by in RCA: 8097] [Article Influence: 539.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen Y, Liu J, Ge Q, Wang M, Zhou J. A risk nomogram for 30-day mortality in Chinese patients with acute pancreatitis using LASSO-logistic regression. Sci Rep. 2025;15:17097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gourd NM, Nikitas N. Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35:1564-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Baron TH, DiMaio CJ, Wang AY, Morgan KA. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update: Management of Pancreatic Necrosis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:67-75.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 470] [Article Influence: 78.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 28. | Párniczky A, Lantos T, Tóth EM, Szakács Z, Gódi S, Hágendorn R, Illés D, Koncz B, Márta K, Mikó A, Mosztbacher D, Németh BC, Pécsi D, Szabó A, Szücs Á, Varjú P, Szentesi A, Darvasi E, Erőss B, Izbéki F, Gajdán L, Halász A, Vincze Á, Szabó I, Pár G, Bajor J, Sarlós P, Czimmer J, Hamvas J, Takács T, Szepes Z, Czakó L, Varga M, Novák J, Bod B, Szepes A, Sümegi J, Papp M, Góg C, Török I, Huang W, Xia Q, Xue P, Li W, Chen W, Shirinskaya NV, Poluektov VL, Shirinskaya AV, Hegyi PJ, Bátovský M, Rodriguez-Oballe JA, Salas IM, Lopez-Diaz J, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Molero X, Pando E, Ruiz-Rebollo ML, Burgueño-Gómez B, Chang YT, Chang MC, Sud A, Moore D, Sutton R, Gougol A, Papachristou GI, Susak YM, Tiuliukin IO, Gomes AP, Oliveira MJ, Aparício DJ, Tantau M, Kurti F, Kovacheva-Slavova M, Stecher SS, Mayerle J, Poropat G, Das K, Marino MV, Capurso G, Małecka-Panas E, Zatorski H, Gasiorowska A, Fabisiak N, Ceranowicz P, Kuśnierz-Cabala B, Carvalho JR, Fernandes SR, Chang JH, Choi EK, Han J, Bertilsson S, Jumaa H, Sandblom G, Kacar S, Baltatzis M, Varabei AV, Yeshy V, Chooklin S, Kozachenko A, Veligotsky N, Hegyi P; Hungarian Pancreatic Study Group. Antibiotic therapy in acute pancreatitis: From global overuse to evidence based recommendations. Pancreatology. 2019;19:488-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL, van Ramshorst B, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Timmer R, Laméris JS, Kruyt PM, Manusama ER, van der Harst E, van der Schelling GP, Karsten T, Hesselink EJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Rosman C, Bosscha K, de Wit RJ, Houdijk AP, van Leeuwen MS, Buskens E, Gooszen HG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 1079] [Article Influence: 67.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Schietroma M, Pessia B, Carlei F, Mariani P, Sista F, Amicucci G. Intestinal permeability and systemic endotoxemia in patients with acute pancreatitis. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:138-144. [PubMed] |

| 31. | De Laet IE, Malbrain MLNG, De Waele JJ. A Clinician's Guide to Management of Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome in Critically Ill Patients. Crit Care. 2020;24:97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nasa P, Chanchalani G, Juneja D, Malbrain ML. Surgical decompression for the management of abdominal compartment syndrome with severe acute pancreatitis: A narrative review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:1879-1891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Garg R, Rustagi T. Management of Hypertriglyceridemia Induced Acute Pancreatitis. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4721357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gao X, Xu J, Xu M, Han P, Sun J, Liang R, Mo S, Tian Y. Nomogram and Web Calculator Based on Lasso-Logistic Regression for Predicting Persistent Organ Failure in Acute Pancreatitis Patients. J Inflamm Res. 2024;17:823-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/