Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.109628

Revised: August 19, 2025

Accepted: September 16, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 133 Days and 2.4 Hours

Recent studies have revealed that endoscopic minimally invasive treatment of early esophageal cancer and precancerous lesions is as effective as traditional surgery and offer considerable advantages, such as minimal invasiveness, en

To analyze factors affecting postoperative fever in patients with early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions who underwent endoscopic radiofrequency ablation (ERFA).

Clinical data of 29 patients with esophageal lesions admitted to The Affiliated Huai’an No. 1 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University between March 2022 and June 2024 were retrospectively analyzed. All patients underwent ERFA and were divided into a fever group and a non-fever group based on whether they experienced fever after surgery. The general characteristics of both groups were analyzed, and univariate analysis of variance and multivariate logistic re

Among the 29 patients with esophageal lesions treated with ERFA, 11 did not experience fever, whereas 18 (62.07%) experienced it. Univariate analysis of variance showed that the ablation length and duration of postoperative fasting were significantly different between the fever and non-fever groups (P < 0.05), whereas the operation time, postoperative use of hormones, postoperative use of antibiotics, and pathological type were not significantly different between these groups (P > 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression indicated that the ablation length and duration of postoperative fasting were independent factors influencing the occurrence of post-ERFA fever.

The incidence of fever is high in patients with early esophageal lesions treated with ERFA, which is related to the ablation length and duration of postoperative fasting. The results can guide modifications in the treatment and nursing plans for patients with esophageal lesions to reduce the risk of postoperative fever.

Core Tip: With the continuous advancement of endoscopic therapeutic techniques, endoscopic treatment for early esophageal cancer and precancerous lesions has become an increasing trend in recent years. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), a minimally invasive therapeutic technique, has emerged in recent years for the treatment of gastrointestinal lesions and is widely adopted in Western countries. Given the high incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in China, this study primarily aimed to observe the clinical efficacy of endoscopic RFA in the treatment of early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions and explore the factors influencing postoperative fever.

- Citation: Feng R, Wang YM, Xie R, Dai WJ. Risk factors of fever following endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(11): 109628

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i11/109628.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.109628

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the seventh most common cancer worldwide and ranks sixth in global cancer mortality[1,2]. Its incidence also varies significantly by region, with China having a particularly high incidence rate[3]. Globally, China accounts for 53.70% of new cases and 55.35% of deaths, which is a shocking proportion[4]. Paradoxically, despite the declining number of new cases, the EC-related mortality rate remains alarmingly high. This grim reality is highlighted by the 5-year relative survival rate, which is < 20%, making it the second lowest survival rate among cancers, second only to pancreatic cancer (10%)[5]. This situation is also complicated by the difficulty in detecting early-stage EC, which often has no specific clinical symptoms[6]. This lack of clear indicators has led to a distressing situation in which a large number of patients are diagnosed at a late stage, missing the opportunity for early detection[7]. The development of EC goes through different stages: Normal esophageal squamous epithelium-mild dysplasia–moderate dysplasia-severe dysplasia-early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma–invasive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[8,9]. In two large population-based cohort studies, the 5-year survival rates for stage IV and I disease were 44.2%-72.6% and 3.4%-16.6%, respectively[10,11]. Therefore, early diagnosis and timely treatment through organized screening programs are crucial. With the development of endoscopic technology and increased public health awareness, early diagnosis and treatment of EC have improved the quality of life and survival rate of patients with EC.

Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation (ERFA) refers to the minimally invasive endoscopic treatment technique where different radiofrequency ablation (RFA) electrodes are applied directly onto flat mucosal lesions in the digestive tract under direct visualization with an endoscope. The procedure uses radiofrequency current to induce coagulation and necrosis, thereby eliminating the lesion. It can be used to treat flat intraepithelial neoplasia and Barrett’s esophagus and capillary dilation lesions in the digestive tract. Its primary advantage in treating early-stage EC lies in its effectiveness for circumferential lesions. Post-ERFA stenosis rates and severity are significantly lower than those of endoscopic submu

This single center retrospective study analyzed case data from The Affiliated Huai'an No. 1 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University where 2022.03-2024.6 endoscopic examination diagnosed early EC or squamous epithelial dysplasia, which appeared as mottled changes after iodine staining, > 3/4 circumferential, and underwent ERFA.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients aged ≥ 18 years; and (2) Iodine lightly stained and nonstained areas > 3/4 circumferential.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Previous history of EC, surgical procedures, or radiochemotherapy; severe organ dysfunction or bleeding tendency, unable to undergo endoscopic examination; previous history of iodine allergy; and (2) Esophageal varices.

Routine endoscopic examination was conducted to identify the lesion site. After iodine staining to determine the treatment area, a 0.35-cm guidewire was inserted and left in place while retracting the scope. A Medtronic 360 circumferential rapid ERFA balloon catheter was placed along the guidewire, the scope was reinserted, and under direct visualization with inflation, RFA was performed from the upper boundary of the treatment area, moving distally every 2 cm (energy density set at 12 J/cm², power at 300 W). Each lesion was ablated twice. The RFA electrode plate was placed on the lesion site for cauterization. After cauterization, the lesion surface solidified and necrotized, and the color turned white. After one cauterization, the solidified necrotic tissue was removed from the surface before performing the next cauterization. Postoperatively, fasting and acid suppression are recommended, and patients were monitored for chest pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, etc.

The following general patient information was collected: Sex, age, body mass index, smoking and alcohol history, past medical history (hypertension and diabetes), postoperative antibiotic use, fever status (highest temperature of fever ≥

Data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). For normally distributed quantitative data, mean ± SD was used, and t-tests were applied between the two groups. Frequency were used for categorical data, and Fisher's exact test was employed for inter-group comparisons. Multivariate ANOVA was conducted using logistic regression analysis, with P < 0.05 indicating significant differences.

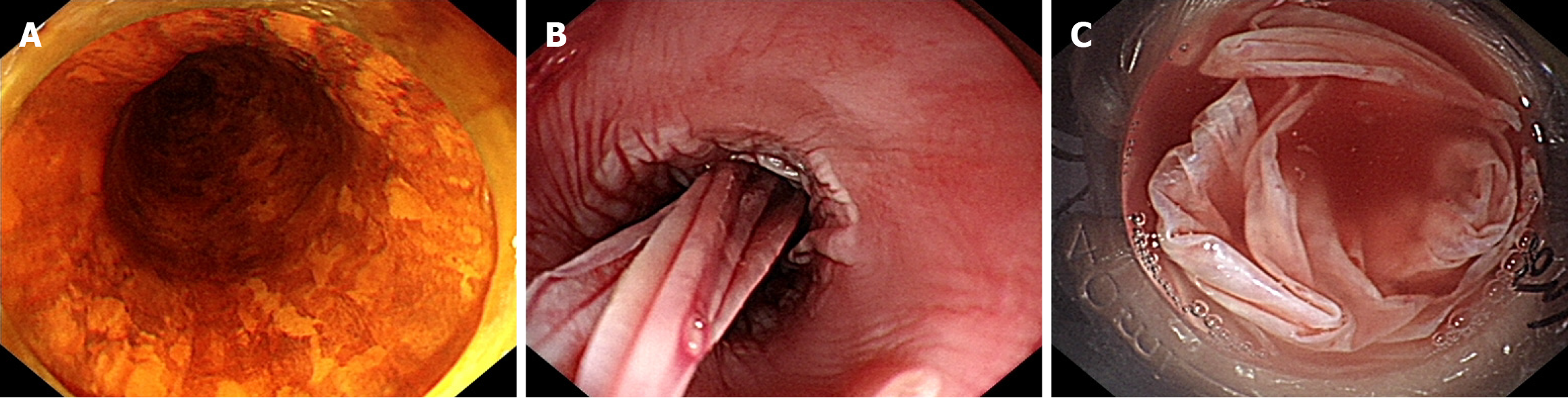

This study included a total of 29 patients with ERFA (male, n = 23; female, n = 6; age, 67.86 ± 7.45 years; height, 1.65 ± 0.08 m; weight, 63.83 ± 10.90 kg). The lesion length was (14.69 ± 4.11) cm, and the operation time was (58.79 ± 16.02) minutes. The general data of the fever and non-fever groups are shown in Table 1. No significant differences in sex, age, height, weight, body mass index, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, hypertension history, and diabetes history were found between the two groups (P > 0.05). Meanwhile, typical case treatment pictures are shown in Figure 1.

| No fever | Fever | Statistics | P value | |

| Sex (n) | 0.164 | |||

| Male | 7 | 16 | ||

| Female | 4 | 2 | ||

| Age (years) | 65.27 ± 6.94 | 69.44 ± 7.49 | -1.495 | 0.146 |

| Height (m) | 1.66 ± 0.11 | 1.64 ± 0.60 | 0.721 | 0.483 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.73 ± 15.32 | 60.83 ± 5.74 | 1.640 | 0.127 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.66 ± 3.53 | 22.78 ± 2.59 | 1.655 | 0.110 |

| Smoke (n) | ||||

| No | 10 | 14 | 0.622 | |

| Yes | 1 | 4 | ||

| Drink (n) | 0.622 | |||

| No | 9 | 16 | ||

| Yes | 2 | 2 | ||

| Hypertension (n) | 0.128 | |||

| No | 3 | 11 | ||

| Yes | 8 | 7 | ||

| Diabetes (n) | ||||

| No | 10 | 14 | 0.622 | |

| Yes | 1 | 4 |

In this study, 18 (62.07%) patients experienced fever, with 14 having a peak temperature > 38 °C, and the average fever temperature was 38.46 °C ± 0.58 °C. According to the results of the one-way ANOVA, the differences between the fever and non-fever groups were significant for ablation length and postoperative fasting time (P < 0.05), whereas no significant differences were noted for the operation time, postoperative use of hormones, postoperative use of antibiotics, and pathological type (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

| No fever | Fever | Statistics | P value | |

| Ablation length (cm) | 12.45 ± 4.57 | 16.10 ± 3.21 | -2.496 | 0.019 |

| Operate time (min) | 57.00 ± 14.96 | 59.89 ± 16.97 | -0.464 | 0.646 |

| Postoperative fasting time (d) | 2.91 ± 0.94 | 2.28 ± 0.67 | 2.109 | 0.044 |

| Whether to use hormones after surgery (n) | 0.646 | |||

| No | 8 | 15 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 3 | ||

| Whether antibiotics should be used after surgery (n) | 0.449 | |||

| No | 8 | 10 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 8 | ||

| The pathology type (n) | 0.719 | |||

| Low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia | 6 | 9 | ||

| High-grade intraepithelial neoplasia | 5 | 7 | ||

| Early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 0 | 2 |

A two-way multiple-factor logistic regression analysis was conducted, with postoperative fever as the dependent variable. The results showed that ablation length and postoperative fasting duration were independent factors in

| Variable | β | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Ablation length (cm) | 0.390 | 0.177 | 4.870 | 0.027 | 1.477 | 1.045-2.088 |

| Postoperative fasting time (day) | -1.572 | 0.739 | 4.524 | 0.033 | 0.208 | 0.049-0.884 |

The patient experienced fever after ERFA for esophageal lesions, and no statistically significant difference was noted in postoperative hospitalization time and treatment cost (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

| No fever | Fever | t | P value | |

| Total treatment costs (CNY) | 28452.73 ± 5829.70 | 30505.24 ± 7158.48 | -0.794 | 0.434 |

| Postoperative length of stay (cm) | 5.55 ± 2.11 | 7.29 ± 2.73 | -1.798 | 0.084 |

On admission, the blood routine test was conducted. After ERFA, the patient with fever was rechecked within 24 hours, and the white blood cell count before and after surgery was compared. The difference was significant (P < 0.01) (Table 5).

| Preoperative | Postoperative | t | P value | |

| White blood cell count (× 109/L) | 5.81 ± 1.82 | 11.24 ± 4.52 | -5.61 | 0.000 |

After iodine staining, early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions show multiple irregular lightly stained or nonstained areas with a mottled appearance. The incidence of post-ESD stricture for large-area early EC ranges from 56% to 76%, and the stricture rate after ESD for esophageal circumferential lesions approaches 100%[17,18]. Therefore, ERFA can be considered for such patients. The main advantage of ERFA lies in treating esophageal circumferential lesions; for circumferential lesions with similar lengths, the degree of esophageal stricture after ERFA is relatively mild. Consequently, an increasing number of physicians are choosing ERFA to treat long-segment esophageal circumferential lesions[14]. In a study that compared ESD and ERFA in patients with early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with full or nearly full circumference[19], the ESD group had a significantly higher risk of esophageal stricture among patients with extensive lesions (60% vs 31%; P < 0.05) and a higher incidence of refractory stricture than the ERFA group. In high-risk patients with long-segment tumors, ESD combined with RFA has a better cure rate, and adverse reactions do not increase[20]. Vassiliou et al[21] found that ERFA was safe and feasible in patients with ultra-long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (≥ 8 cm), and it can be applied throughout the metaplastic epithelium during a single treatment session. Through repeated ablation and continuous, cautious monitoring, Barrett’s procedure can be eradicated, indicating that ERFA has unique advantages in treating circumferential, near-circumferential, and long-segment lesions. However, intraoperatively, postoperative complications, such as stenosis, fever, chest pain, and nausea, are also relatively common after ERFA. In this study, none of the 29 patients experienced perforation. Our research team has also been concerned about the incidence of stenosis in patients who underwent ERFA. Given that some patients are still under follow-up, some data have not yet been obtained. This study found that fever is more frequently observed postoperatively. Therefore, relevant data were collected to analyze the risk factors for fever following esophageal lesion treatment with ERFA to address the concerns encountered during and after surgery and reduce patient suffering.

The results of this study show that the ablation length is an independent influencing factor for post-ERFA fever in patients with esophageal mucosal lesions. However, in this study, the probability of fever was higher at 62.07%, possibly due to a wider area of mottled esophageal circumferential lesions. Most of the esophageal lesions were near-circumferential, and the results indicate that the longer the ablation length and the larger the range, the larger the postoperative wound, the more severe the inflammatory response, and the higher the likelihood of fever. ERFA uses a special balloon catheter system to release radiofrequency energy, causing thermal damage to esophageal lesions, leading to dehydration, drying, and coagulative necrosis of the lesion tissue, thus achieving therapeutic goals. It has significant advantages in treating early-stage EC and multiple and long precancerous lesions or involve the entire circumference of the esophagus, with uniform effects and a treatment depth controlled at approximately 1000 μm, reducing the incidence of perforation and postoperative stenosis. In our hospital, steroids are used in patients with longer ablation lengths as a treatment method similar to preventing stricture after ESD; however, the postoperative use of steroids does not effectively prevent fever. Currently, post-ERFA fever may be caused by the release of large amounts of inflammatory factors from the necrotic material after ablation. Leukocyte infiltration is the most important characteristic of the inflammatory response. In this study, all patients who experienced fever postoperatively had their blood counts rechecked, and compared with preoperative values, the white blood cell count indeed increased, indicating an inflammatory response and suggesting the rationality of using antibiotics postoperatively. However, in this study, no positive results were found in blood cultures from any patient, and none of the patients exhibited significant systemic toxic reactions. In clinical practice, empirical antibiotic therapy is often used for patients who underwent longer surgical procedures to prevent pos

This study still has some limitations. The retrospective nature does not allow for randomization of patients into two groups, as this would compromise the similarity of patients within each group. Additionally, retrospective data analysis is associated with information bias, particularly in studies with incomplete data. The sample size may also be too small to detect between-group differences. Therefore, the similarity in clinical outcomes observed in this study may represent a type II error. A well-designed, randomized, controlled prospective data collection and sample size calculation trial are needed to confirm the results of this study.

In summary, the stricture rates following esophageal ESD for early-stage squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions are relatively high. For such patients, RFA of the esophagus can be considered. Given that ERFA has a shallower depth, precise preoperative staging must be performed before applying ERFA. In this study, the post-ERFA fever rates were higher. The results indicate that the ablation length and postoperative fasting period are independent factors affecting post-ERFA fever. Preventive antibiotics cannot completely prevent fever; however, ERFA-induced fever is indeed an inflammatory response, making the use of antibiotics reasonable. Regular follow-up is still necessary to confirm recurrence. This study was conducted at a single center, which has certain limitations. Although multiple factors were included for a comprehensive analysis, the sample size was small, and a larger sample size is needed for in-depth research.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68832] [Article Influence: 13766.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (202)] |

| 2. | Fan J, Liu Z, Mao X, Tong X, Zhang T, Suo C, Chen X. Global trends in the incidence and mortality of esophageal cancer from 1990 to 2017. Cancer Med. 2020;9:6875-6887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li J, Xu J, Zheng Y, Gao Y, He S, Li H, Zou K, Li N, Tian J, Chen W, He J. Esophageal cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors and screening. Chin J Cancer Res. 2021;33:535-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J, Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA, Bray F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:335-349.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 857] [Cited by in RCA: 1446] [Article Influence: 241.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 5. | Qu HT, Li Q, Hao L, Ni YJ, Luan WY, Yang Z, Chen XD, Zhang TT, Miao YD, Zhang F. Esophageal cancer screening, early detection and treatment: Current insights and future directions. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024;16:1180-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Sheikh M, Roshandel G, McCormack V, Malekzadeh R. Current Status and Future Prospects for Esophageal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 55.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Visaggi P, Barberio B, Ghisa M, Ribolsi M, Savarino V, Fassan M, Valmasoni M, Marchi S, de Bortoli N, Savarino E. Modern Diagnosis of Early Esophageal Cancer: From Blood Biomarkers to Advanced Endoscopy and Artificial Intelligence. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu CQ, Ma YL, Qin Q, Wang PH, Luo Y, Xu PF, Cui Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in 2020 and projections to 2030 and 2040. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14:3-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao J, Jia X, Li Q, Zhang H, Wang J, Huang S, Hu Z, Li C. Genomic and transcriptional characterization of early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Med Genomics. 2023;16:153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cheng YF, Chen HS, Wu SC, Chen HC, Hung WH, Lin CH, Wang BY. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and prognosis in Taiwan. Cancer Med. 2018;7:4193-4201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jung HK, Tae CH, Lee HA, Lee H, Don Choi K, Park JC, Kwon JG, Choi YJ, Hong SJ, Sung J, Chung WC, Kim KB, Kim SY, Song KH, Park KS, Jeon SW, Kim BW, Ryu HS, Lee OJ, Baik GH, Kim YS, Jung HY; Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research. Treatment pattern and overall survival in esophageal cancer during a 13-year period: A nationwide cohort study of 6,354 Korean patients. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li ZS, Ling Hu EQ, Wang LW. [Expert consensus on the clinical application of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for digestive tract diseases in China (2020, Shanghai)]. Zhonghua Xiaohua Neijing Zazhi. 2020;37:6. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Lei S, Mulmi Shrestha S, Shi R. Radiofrequency Ablation for Early Superficial Flat Esophageal Squamous Cell Neoplasia: A Comprehensive Review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:4152453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qumseya BJ, Wani S, Desai M, Qumseya A, Bain P, Sharma P, Wolfsen H. Adverse Events After Radiofrequency Ablation in Patients With Barrett's Esophagus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1086-1095.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, Wolfsen HC, Sampliner RE, Wang KK, Galanko JA, Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, Bennett AE, Jobe BA, Eisen GM, Fennerty MB, Hunter JG, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ, Rothstein RI, Gordon SR, Mashimo H, Chang KJ, Muthusamy VR, Edmundowicz SA, Spechler SJ, Siddiqui AA, Souza RF, Infantolino A, Falk GW, Kimmey MB, Madanick RD, Chak A, Lightdale CJ. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277-2288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1146] [Cited by in RCA: 1003] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Pouw RE, Gondrie JJ, Curvers WL, Sondermeijer CM, Ten Kate FJ, Bergman JJ. Successful balloon-based radiofrequency ablation of a widespread early squamous cell carcinoma and high-grade dysplasia of the esophagus: a case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:537-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Abe S, Iyer PG, Oda I, Kanai N, Saito Y. Approaches for stricture prevention after esophageal endoscopic resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:779-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hanaoka N, Ishihara R, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Higashino K, Ohta T, Kanzaki H, Hanafusa M, Nagai K, Matsui F, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Ito Y. Intralesional steroid injection to prevent stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal cancer: a controlled prospective study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1007-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ding Y, Liu Y, Lei S, Zhang W, Qian Q, Zhao Y, Shi R. Comparison between ESD and RFA in patients with total or near-total circumferential early esophageal squamous cell neoplasia. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:6915-6921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bahdi F, Othman M. S0946 Outcomes of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Plus Radiofrequency Ablation for Nodular Barrett's Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:S484-S485. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Vassiliou MC, von Renteln D, Wiener DC, Gordon SR, Rothstein RI. Treatment of ultralong-segment Barrett's using focal and balloon-based radiofrequency ablation. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:786-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen M, Dang Y, Ding C, Yang J, Si X, Zhang G. Lesion size and circumferential range identified as independent risk factors for esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4065-4071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/