Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.114624

Revised: October 27, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 112 Days and 8.9 Hours

Obesity and diabetes are well-established risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), and their coexistence is particularly detrimental in chronic kidney disease (CKD). However, the interactions between various adiposity patterns and glyce

To evaluate the combined effects of diabetes, body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference (WC) on CVD risk.

We analyzed data from 1714859 adults with CKD sourced from the Korean Na

A significant interaction was identified between glycemic status and adiposity indices concerning CVD risk (P for interaction < 0.001). Among normoglycemic individuals, both underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) and central obesity (WC ≥ 100/95 cm in men/women) were associated with increased CVD risk and mortality. In individuals with IFG, underweight remained a consistent risk factor, while WC displayed a linear relationship with CVD but not with mortality. In those with DM, the highest CVD risk was observed in individuals who were underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) and had low WC (< 80 cm in men/< 75 cm in women).

Cardiovascular risk is jointly influenced by glycemic status and adiposity, with diabetes consistently elevating risk across all BMI and WC categories, underscoring the importance of their assessment in CKD.

Core Tip: This nationwide cohort study of over 1.7 million individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) demonstrates that cardiovascular (CV) risk is strongly modified by both glycemic status and patterns of adiposity. Diabetes consistently amplified CV risk across all body mass index and waist circumference categories, negating any protective effect of higher adiposity. Conversely, underweight and centrally lean individuals with diabetes exhibited the greatest vulnerability, un

- Citation: Bae EH, Lim SY, Kim BS, Han K, Suh SH, Choi HS, Yang EM, Kim CS, Ma SK, Kim SW. Combined effects of glycemic status and adiposity on cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease: A nationwide population-based study. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 114624

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/114624.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.114624

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally, imposing a particularly heavy burden on patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD)[1]. Both diabetes mellitus (DM) and obesity are well-established risk factors for adverse cardiovascular (CV) outcomes, and their coexistence with CKD exacerbates vascular damage and worsens prognosis[2]. As the prevalence of CKD continues to rise in aging populations, understanding the interplay of metabolic risk factors in influencing CV health has become a critical clinical priority.

Obesity is traditionally assessed using body mass index (BMI), which reflects overall adiposity, and waist circumference (WC), which serves as a surrogate for central obesity. While both indices are associated with CVD in the general population, evidence suggests that their predictive values may vary across different metabolic states[3]. Notably, BMI does not account for body fat distribution, while WC more accurately reflects visceral adiposity, which is closely linked to cardiometabolic risk[4]. In patients with CKD, the interpretation of anthropometric data is further complicated by factors such as malnutrition, sarcopenia, and fluid overload, raising concerns regarding the reliability of obesity indices in predicting CV outcomes in this population.

DM significantly heightens CV risk; however, the extent to which glycemic status modifies the relationship between obesity indices and CVD in CKD remains inadequately understood. Studies in the general population have reported paradoxical associations, including the so-called “obesity paradox”, as well as varying effects based on glycemic status[5,6]. Nevertheless, few large-scale investigations have systematically examined the joint effects of diabetes status and adiposity indices on CVD outcomes in CKD.

Considering the limited evidence regarding the mechanism by which diabetes status modifies the relationship between adiposity and CV outcomes in CKD, we conducted a nationwide cohort study using the Korean National Health In

In this study, we utilized the national health insurance claims database established by the KNHIS, which includes all claims data from the KNHIS and Medical Aid programs. The KNHIS database is considered representative of the entire South Korean population, and its details have previously been described[7,8]. Consequently, data extracted from the KNHIS database represent approximately 50 million insured Koreans. All insured individuals aged over 40 years undergo a biannual health checkup supported by the KNHIS, while employees aged over 20 years are mandated to undergo a health checkup annually. The KNHIS databases generated through these checkups provide wide-ranging information, including anthropometric measurements, health questionnaire data, and laboratory findings. Anonymized data are publicly available from the KNHIS and can be accessed at https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba000eng.do. This study was approved by the Chonnam National University Hospital (Approval No. CNUH-EXP-2025-219) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Our review board waived the requirement for written informed consent.

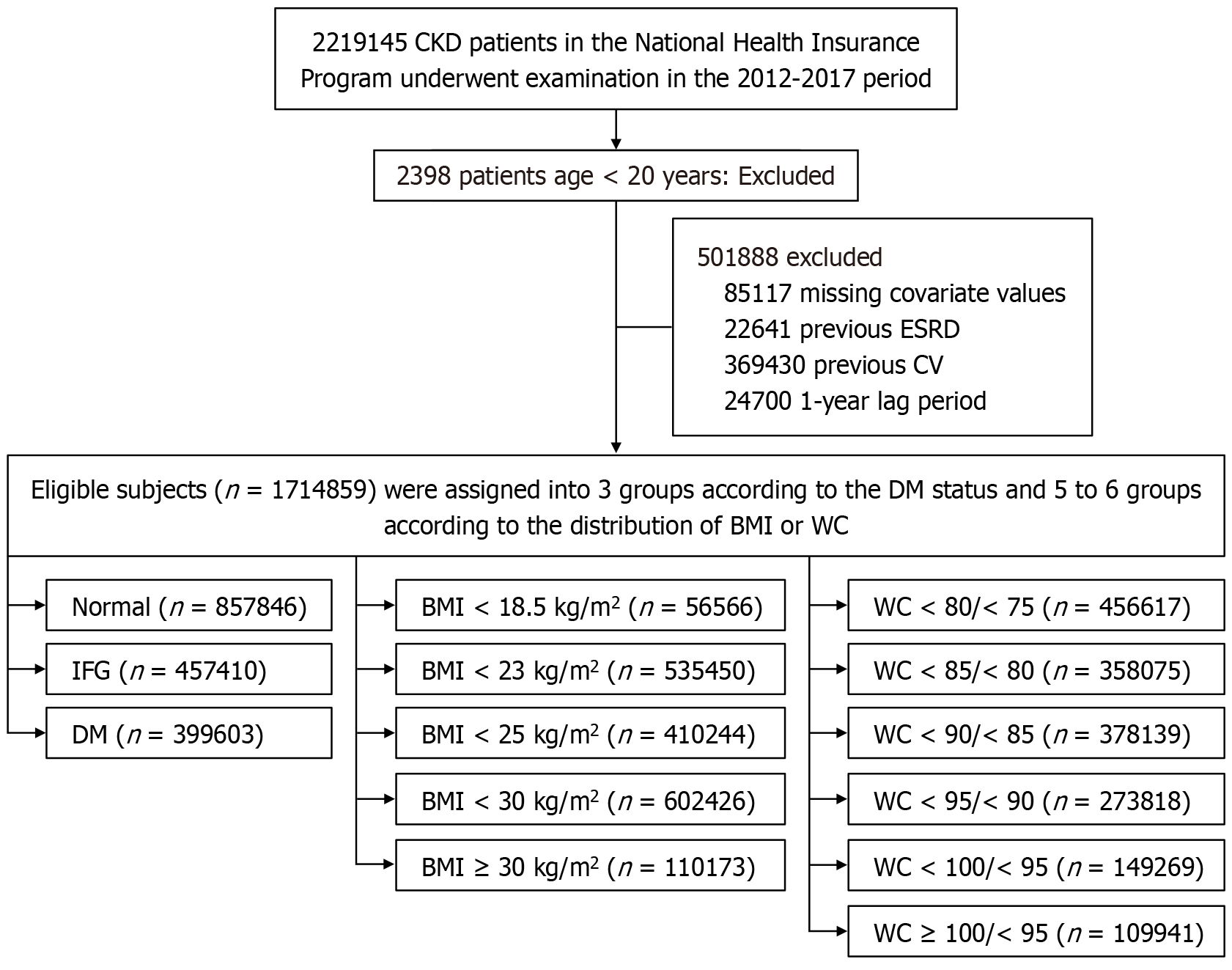

All participants who underwent KNHIS health checkups from 2012 to 2017 (n = 2219145) were initially enrolled in the study and followed up until the end of 2022. Participants aged under 20 years (n = 2398), those with missing data on baseline characteristics and covariates (n = 85117), and individuals with pre-existing end-stage renal disease (n = 22641) or underlying CVD (n = 369430) at baseline were excluded from the study. Additionally, participants excluded during the 1-year lag period (n = 24700) were also removed. The final sample comprised 1714859 participants who were evaluated based on their DM status and obesity indices (Figure 1).

The diagnosis of diabetes at baseline was determined based on a fasting blood glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL or the presence of International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD-10) codes E11-14 along with a claim for anti-diabetic medication[7]. Hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg; ICD-10 codes I10-I15) and hyperlipidemia (total cholesterol ≥ 240 mg/dL; ICD-10 code E78) diagnoses were confirmed using laboratory data, accompanied by a claim for medication specific to each condition. Ischemic heart disease was identified using ICD-10 codes I21-25. CKD was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/minute/1.73 m2, calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation[8]. Participants were categorized into three groups based on their smoking status: Non-smokers, current smokers, and former smokers. Additionally, participants were grouped according to alcohol consumption into non-drinkers, moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers (defined as consuming > 30 g of alcohol per day). Regular exercise was defined by responses to the question: “During the last week, did you exercise vigorously for over 20 minutes on more than 3 days until you were almost out of breath?” Income was stratified into quartiles (Q): Q1 (the lowest), Q2, Q3, and Q4 (the highest), with the lowest income level defined as the bottom 25% of income. Urban residency was also assessed. The quality of laboratory tests is upheld by the Korean Association for Laboratory Medicine, while the KNHIS certifies hospitals participating in the National Health Insurance health check-up programs. Proteinuria was assessed using the dipstick method, with results classified as negative, trace, or graded from 1+ to 4+. Energy expenditure was denoted as the “minimum” amount of energy consumption calculated from a self-reported survey question regarding the frequency of each exercise intensity over a specified duration.

Body weight (kg) and height (cm) were measured using an electronic scale, while WC (cm) was measured at the midpoint between the rib cage and iliac crest by trained examiners. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and patients were classified according to the World Health Organization’s recommendations for Asians as follows: Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI = 18.5-23 kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 23-25 kg/m2), stage I obesity (BMI = 25-30 kg/m2), and stage II obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)[9]. Abdominal obesity was defined as a WC ≥ 90 cm for men and 85 cm for women, in accordance with the criteria established by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity[10]. WC was divided into six categories based on 5-cm increments: (1) Level 1: < 80 cm in men and < 75 cm in women; (2) Level 2: 80-85 cm in men and 75-80 cm in women; (3) Level 3: 85-90 cm in men and 80-85 cm in women; (4) Level 4: 90-95 cm in men and 85-90 cm in women; (5) Level 5: 95-100 cm in men and 90-95 cm in women; and (6) Level 6: ≥ 100 cm in men and ≥ 95 cm in women.

The study endpoints included incident CVD, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and all-cause mortality. CVD was defined as a composite of MI and stroke, based on hospitalization records with relevant ICD-10 codes. MI and stroke were defined as the first hospitalization with a primary discharge diagnosis of I21-I22 for MI and I63-I64 for ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. All-cause mortality was ascertained based on national mortality records linked to the KNHIS database[11].

The follow-up period for each outcome commenced 365 days after the index health checkup date to minimize reverse causation (1-year lag period). The time to each event (CVD, MI, stroke, and death) was calculated as the interval from the index date + 365 days to the first occurrence of the corresponding outcome. Participants were censored at the date of death (for non-fatal outcomes) or at the conclusion of the follow-up period, whichever preceded. The study termination date for follow-up was December 31, 2022.

The mean follow-up duration ± SD was 7.42 ± 1.96 years for CVD, 7.54 ± 1.83 years for MI, 7.51 ± 1.87 years for stroke, and 7.64 ± 1.72 years for all-cause mortality.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD for continuous variables and expressed as proportions for categorical variables. Non-normally distributed data are reported as median values (25th, 75th percentile). Comparisons between groups defined by anthropometric indices, including BMI, WC, and diabetes-specific indices, were performed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

The incidence rates of CVD, MI, stroke, and all-cause mortality were calculated per 1000 person-years. To determine whether the association between glycemic status and CV outcomes varied by adiposity level, we examined statistical interactions between glycemic status [normal, impaired fasting glucose (IFG), and diabetes] and each adiposity index (BMI and WC). Multiplicative interaction terms (glycemic status × adiposity index) were incorporated into multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for covariates including age, sex, income, smoking, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. The significance of the interactions was assessed using the likelihood ratio test, which compared models with and without the interaction terms. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals for each combination of glycemic status and adiposity category were subsequently estimated.

Analyses were conducted in three models: Model 1 (unadjusted), model 2 (adjusted for age and sex), and model 3 (adjusted for model 2 plus income, smoking, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, hypertension, and dyslipidemia). Analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of participants stratified by glycemic status. Among 1714859 participants, those with DM were older, predominantly male, and exhibited a higher prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking, and heavy alcohol consumption compared with those with normal glucose levels or IFG. Additionally, they demonstrated poorer metabolic and renal profiles, characterized by higher values for BMI, WC, blood pressure, triglyceride content, and fasting glucose, alongside lower levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and eGFR, as well as a greater incidence of proteinuria. Table 2 summarizes baseline characteristics categorized by BMI. Participants with elevated BMI were generally younger, tended to be male, and displayed a higher prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and other cardiometabolic risk factors. In contrast, underweight individuals tended to be older, with lower eGFR values and a higher prevalence of proteinuria. Table 3 details baseline characteristics according to WC categories. Higher WC values correlated with older age, male predominance, and a substantially higher prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and associated cardiometabolic risk factors. Blood pressure, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and BMI progressively increased across WC categories, while HDL-C levels decreased. Participants exhibiting the highest WC values also displayed elevated rates of proteinuria, although eGFR values appeared to be lower in the mid-range groups. Conversely, individuals with the lowest WC values were younger, had fewer cardiometabolic comorbidities, yet demonstrated a relatively higher prevalence of proteinuria.

| Group | Total (n = 1714859) | Normal (n = 857846) | IFG (n = 457410) | DM (n = 399603) | P value |

| Age (year) | 57.78 ± 14.68 | 54.81 ± 15.65 | 59.25 ± 13.66 | 62.50 ± 11.89 | < 0.0001 |

| 39 | 198542 (11.58) | 149867 (17.47) | 35887 (7.85) | 12788 (3.20) | < 0.0001 |

| 40-64 | 902922 (52.65) | 449993 (52.46) | 249689 (54.59) | 203240 (50.86) | |

| ≥ 65 | 613395 (35.77) | 257986 (30.07) | 171834 (37.57) | 183575 (45.94) | |

| Sex (male) | 815109 (47.53) | 350599 (40.87) | 236377 (51.68) | 228133 (57.09) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Non | 1119098 (65.26) | 599967 (69.94) | 286581 (62.65) | 232550 (58.2) | |

| Former | 284742 (16.60) | 118485 (13.81) | 85402 (18.67) | 80855 (20.23) | |

| Current | 311019 (18.14) | 139394 (16.25) | 85427 (18.68) | 86198 (21.57) | |

| Heavy drinker1 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Non | 1068788 (62.33) | 544658 (63.49) | 271279 (59.31) | 252851 (63.28) | |

| Mild | 534295 (31.16) | 272101 (31.72) | 149782 (32.75) | 112412 (28.13) | |

| Heavy | 111776 (6.52) | 41087 (4.79) | 36349 (7.95) | 34340 (8.59) | |

| Physical activity-regular | 351280 (20.48) | 174600 (20.35) | 94593 (20.68) | 82087 (20.54) | < 0.0001 |

| Income-low2 | 373049 (21.75) | 183523 (21.39) | 97205 (21.25) | 92321 (23.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 883385 (51.51) | 336506 (39.23) | 249054 (54.45) | 297825 (74.53) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 613846 (35.8) | 229687 (26.77) | 165923 (36.27) | 218236 (54.61) | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR < 60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 | 991664 (57.83) | 472872 (55.12) | 279726 (61.15) | 239066 (59.83) | < 0.0001 |

| Proteninuria, positive | 799235 (46.61) | 411203 (47.93) | 195049 (42.64) | 192983 (48.29) | < 0.0001 |

| Height, cm | 161.43 ± 9.46 | 161.22 ± 9.36 | 161.73 ± 9.62 | 161.53 ± 9.48 | < 0.0001 |

| Weight, kg | 63.98 ± 12.43 | 62.00 ± 11.90 | 65.46 ± 12.63 | 66.52 ± 12.60 | < 0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.44 ± 3.55 | 23.75 ± 3.41 | 24.90 ± 3.49 | 25.39 ± 3.61 | < 0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 82.70 ± 9.76 | 80.17 ± 9.60 | 83.97 ± 9.25 | 86.68 ± 9.05 | < 0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 108.24 ± 36.02 | 88.85 ± 7.41 | 108.53 ± 6.79 | 149.52 ± 53.73 | < 0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 126.37 ± 16.40 | 123.28 ± 15.91 | 128.38 ± 16.05 | 130.71 ± 16.47 | < 0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 77.69 ± 10.69 | 76.40 ± 10.49 | 79.16 ± 10.70 | 78.78 ± 10.75 | < 0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 198.27 ± 41.31 | 197.97 ± 38.72 | 205.44 ± 41.04 | 190.72 ± 45.40 | < 0.0001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 53.87 ± 16.26 | 55.79 ± 16.69 | 53.81 ± 15.82 | 49.82 ± 15.00 | < 0.0001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 116.05 ± 37.74 | 117.34 ± 35.65 | 121.51 ± 38.03 | 107.02 ± 40.10 | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR, mL/minute/1.73 m2 | 68.52 ± 24.02 | 71.03 ± 25.23 | 66.63 ± 22.03 | 65.30 ± 22.94 | < 0.0001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 122.65 (122.54-122.75) | 107.31 (107.18-107.43) | 132.22 (132.01-132.43) | 149.92 (149.67-150.18) | < 0.0001 |

| Group | BMI (kg/m2) | P value | ||||

| < 18.5 (n = 56566) | < 23 (n = 535450) | < 25 (n = 410244) | < 30 (n = 602426) | ≥ 30 (n = 110173) | ||

| Age (year) | 51.24 ± 20.28 | 56.65 ± 15.99 | 59.59 ± 13.39 | 58.95 ± 13.19 | 53.53 ± 14.69 | < 0.0001 |

| 39 | 19502 (34.48) | 80030 (14.95) | 30517 (7.44) | 47728 (7.92) | 20765 (18.85) | < 0.0001 |

| 40-64 | 19602 (34.65) | 270107 (50.44) | 220489 (53.75) | 332408 (55.18) | 60316 (54.75) | |

| ≥ 65 | 17462 (30.87) | 185313 (34.61) | 159238 (38.82) | 222290 (36.9) | 29092 (26.41) | |

| Sex (male) | 16627 (29.39) | 210349 (39.28) | 207643 (50.61) | 326356 (54.17) | 54134 (49.14) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Non | 41252 (72.93) | 374889 (70.01) | 263541 (64.24) | 370438 (61.49) | 68978 (62.61) | |

| Former | 4484 (7.93) | 67386 (12.58) | 74651 (18.20) | 120838 (20.06) | 17383 (15.78) | |

| Current | 10830 (19.15) | 93175 (17.40) | 72052 (17.56) | 111150 (18.45) | 23812 (21.61) | |

| Drinking1 | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Non | 36289 (64.15) | 345181 (64.47) | 256710 (62.57) | 364598 (60.52) | 66010 (59.91) | |

| Mild | 17634 (31.17) | 162628 (30.37) | 127973 (31.19) | 191763 (31.83) | 34297 (31.13) | |

| Heavy | 2643 (4.67) | 27641 (5.16) | 25561 (6.23) | 46065 (7.65) | 9866 (8.96) | |

| Physical activity-regular2 | 7235 (12.79) | 106891 (19.96) | 91849 (22.39) | 126601 (21.02) | 18704 (16.98) | < 0.0001 |

| Income-low3 | 13067 (23.10) | 120206 (22.45) | 87657 (21.37) | 127458 (21.16) | 24661 (22.38) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 14261 (25.21) | 206166 (38.5) | 212345 (51.76) | 372258 (61.79) | 78355 (71.12) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 8264 (14.61) | 143192 (26.74) | 150791 (36.76) | 258843 (42.97) | 52756 (47.88) | < 0.0001 |

| 23040 (40.73) | 298062 (55.67) | 255719 (62.33) | 363721 (60.38) | 51122 (46.40) | < 0.0001 | |

| Proteninuria, positive | 35622 (62.97) | 259211 (48.41) | 172597 (42.07) | 267338 (44.38) | 64467 (58.51) | < 0.0001 |

| Height, cm | 160.74 ± 8.76 | 160.7 ± 8.93 | 161.42 ± 9.38 | 161.95 ± 9.74 | 162.48 ± 10.69 | < 0.0001 |

| Weight, kg | 45.11 ± 5.50 | 54.95 ± 6.92 | 62.64 ± 7.45 | 70.7 ± 9.21 | 85.8 ± 13.26 | < 0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.4 ± 0.92 | 21.21 ± 1.2 | 23.95 ± 0.57 | 26.86 ± 1.33 | 32.35 ± 2.53 | < 0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 66.44 ± 6.20 | 75.24 ± 6.61 | 82.12 ± 5.83 | 88.33 ± 6.37 | 98.71 ± 8.13 | < 0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 98.56 ± 34.86 | 103.29 ± 34.63 | 107.86 ± 34.75 | 111.82 ± 36.18 | 119.11 ± 41.66 | < 0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 116.46 ± 16.62 | 122.15 ± 16.2 | 126.51 ± 15.6 | 129.54 ± 15.56 | 134.12 ± 16.85 | < 0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 72.68 ± 10.47 | 75.16 ± 10.27 | 77.49 ± 10.13 | 79.56 ± 10.42 | 83.07 ± 11.85 | < 0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 185.47 ± 37.79 | 194.51 ± 39.8 | 199.27 ± 41.18 | 201.09 ± 42.17 | 204.02 ± 43.11 | < 0.0001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 63.82 ± 19.06 | 57.73 ± 17.3 | 53.03 ± 15.56 | 50.85 ± 14.68 | 49.66 ± 14.08 | < 0.0001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 102.76 ± 33.77 | 113.4 ± 36.16 | 117.81 ± 37.74 | 118.01 ± 38.69 | 118.47 ± 39.65 | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR, mL/minute/ | 78.73 ± 29.01 | 70.14 ± 25.38 | 66.19 ± 22.44 | 66.76 ± 22.43 | 73.77 ± 25.75 | < 0.0001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 82.17 (81.84-82.52) | 100.83 (100.68-100.98) | 124.19 (123.99-124.4) | 142.81 (142.61-143) | 162.06 (161.55-162.58) | < 0.0001 |

| Group | WCs (male/female) | ||||||

| < 80/< 75 (n = 445617) | < 85/< 80 (n = 358075) | < 90/< 85 (n = 378139) | < 95/< 90 (n = 273818) | < 100/< 95 (n = 149269) | ≥ 100/≥ 95 (n = 109941) | P value | |

| Age (year) | 52.37 ± 16.17 | 58.13 ± 13.73 | 60.06 ± 13.20 | 60.82 ± 13.16 | 61.02 ± 13.66 | 58.81 ± 15.12 | < 0.0001 |

| 39 | 198542 (11.58) | 96433 (21.64) | 32726 (9.14) | 26123 (6.91) | 17981 (6.57) | 11316 (7.58) | < 0.0001 |

| 40-64 | 902922 (52.65) | 239284 (53.70) | 202415 (56.53) | 201019 (53.16) | 138486 (50.58) | 70970 (47.55) | |

| ≥ 65 | 613395 (35.77) | 109900 (24.66) | 122934 (34.33) | 150997 (39.93) | 117351 (42.86) | 66983 (44.87) | |

| Sex (male) | 815109 (47.53) | 160554 (36.03) | 184340 (51.48) | 198169 (52.41) | 147268 (53.78) | 73968 (49.55) | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Non | 321941 (72.25) | 226439 (63.24) | 236728 (62.60) | 167768 (61.27) | 95150 (63.74) | 321941 (72.25) | |

| Former | 48723 (10.93) | 62843 (17.55) | 72346 (19.13) | 55303 (20.20) | 27670 (18.54) | 48723 (10.93) | |

| Current | 74953 (16.82) | 68793 (19.21) | 69065 (18.26) | 50747 (18.53) | 26449 (17.72) | 74953 (16.82) | |

| Drinking1 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Non | 278821 (62.57) | 218854 (61.12) | 234984 (62.14) | 169578 (61.93) | 95478 (63.96) | 71073 (64.65) | |

| Mild | 145938 (32.75) | 116100 (32.42) | 117063 (30.96) | 83123 (30.36) | 42164 (28.25) | 29907 (27.20) | |

| Heavy | 20858 (4.68) | 23121 (6.46) | 26092 (6.90) | 21117 (7.71) | 11627 (7.79) | 8961 (8.15) | |

| PA-regular2 | 91577 (20.55) | 80060 (22.36) | 81067 (21.44) | 54497 (19.90) | 26872 (18.00) | 17207 (15.65) | < 0.0001 |

| Income-low3 | 100487 (22.55) | 76710 (21.42) | 80359 (21.25) | 58281 (21.28) | 32372 (21.69) | 100487 (22.55) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 133696 (30.00) | 169039 (47.21) | 215195 (56.91) | 176686 (64.53) | 105284 (70.53) | 83485 (75.94) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 97624 (21.91) | 120857 (33.75) | 150220 (39.73) | 119632 (43.69) | 70589 (47.29) | 54924 (49.96) | < 0.0001 |

| 217826 (48.88) | 212775 (59.42) | 236063 (62.43) | 171542 (62.65) | 92273 (61.82) | 61185 (55.65) | < 0.0001 | |

| Proteninuria, positive | 243137 (54.56) | 160187 (44.74) | 159386 (42.15) | 116057 (42.38) | 65197 (43.68) | 55271 (50.27) | < 0.0001 |

| Height, cm | 160.3 ± 8.52 | 161.43 ± 9.18 | 161.64 ± 9.58 | 162.18 ± 9.91 | 162.02 ± 10.24 | 162.57 ± 10.75 | < 0.0001 |

| Weight, kg | 54.07 ± 7.75 | 61.23 ± 8.52 | 65.2 ± 9.39 | 69.53 ± 10.31 | 73.53 ± 11.45 | 82.1 ± 15.06 | < 0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21 ± 2.17 | 23.42 ± 1.95 | 24.86 ± 2.05 | 26.33 ± 2.19 | 27.88 ± 2.40 | 30.88 ± 3.55 | < 0.0001 |

| WC, cm | 70.92 ± 4.97 | 79.6 ± 2.91 | 84.52 ± 2.9 | 89.45 ± 2.82 | 94.14 ± 2.88 | 101.99 ± 5.56 | < 0.0001 |

| FBS, mg/dL | 99.68 ± 31.06 | 106.53 ± 34.58 | 109.96 ± 35.92 | 112.9 ± 37.22 | 115.71 ± 38.98 | 120.79 ± 43.36 | < 0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 119.97 ± 15.86 | 125.62 ± 15.69 | 127.97 ± 15.59 | 129.87 ± 15.71 | 131.38 ± 15.91 | 133.72 ± 16.80 | < 0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 74.46 ± 10.25 | 77.24 ± 10.26 | 78.42 ± 10.29 | 79.42 ± 10.52 | 80.29 ± 10.79 | 81.91 ± 11.65 | < 0.0001 |

| TC, mg/dL | 193.52 ± 38.91 | 198.98 ± 40.9 | 200.18 ± 41.8 | 200.21 ± 42.38 | 200.46 ± 43.09 | 200.89 ± 43.59 | < 0.0001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 59.99 ± 17.79 | 53.94 ± 16.02 | 51.8 ± 14.89 | 50.52 ± 14.48 | 50.03 ± 14.51 | 49.54 ± 14.12 | < 0.0001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 112.21 ± 35.32 | 117.59 ± 37.46 | 117.95 ± 38.22 | 117.2 ± 38.90 | 116.67 ± 39.66 | 116.33 ± 39.70 | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR, mL/minute/ | 74.08 ± 26.44 | 67.72 ± 23.19 | 65.91 ± 22.22 | 65.51 ± 22.03 | 65.77 ± 22.74 | 68.84 ± 25.00 | < 0.0001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 92.04 (91.9-92.19) | 119.72 (119.51-119.93) | 133.83 (133.6-134.06) | 144.27 (143.98-144.56) | 151.22 (150.81-151.62) | 158.00 (157.51-158.48) | < 0.0001 |

Table 4 summarizes the multivariate Cox analysis results for incident CV outcomes based on glycemic status. Compared with participants with normal glucose, those with IFG exhibited modestly increased risks of CVD, MI, stroke, and all-cause mortality after multivariable adjustment (model 3: HRs = 1.04-1.05 for CVD, MI, and stroke; HRs = 1.03 for mortality). In contrast, participants with diabetes demonstrated significantly higher risks, yielding HRs = 1.57, 1.60, 1.58, and HRs = 1.60 for CVD, MI, stroke, and mortality in fully adjusted models, respectively. Overall, diabetes was strongly associated with an increased incidence of adverse CV outcomes and mortality, while IFG conferred a smaller yet sig

| Outcome | DM status | n | Events (n) | Duration, PY | IR, per 1000 | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| CVD | Normal | 857846 | 47590 | 6508730.39 | 7.31 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| IFG | 457410 | 32092 | 3393918.30 | 9.46 | 1.30 (1.28-1.32) | 1.07 (1.05-1.08) | 1.04 (1.03-1.06) | |

| DM | 399603 | 48151 | 2824691.28 | 17.05 | 2.35 (2.32-2.38) | 1.69 (1.67-1.72) | 1.57 (1.55-1.59) | |

| MI | Normal | 857846 | 22657 | 6586843.49 | 3.44 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| IFG | 457410 | 15083 | 3446873.19 | 4.38 | 1.28 (1.25-1.30) | 1.06 (1.04-1.09) | 1.05 (1.02-1.07) | |

| DM | 399603 | 23193 | 2901757.43 | 7.99 | 2.35 (2.30-2.39) | 1.73 (1.70-1.76) | 1.60 (1.57-1.63) | |

| Stroke | Normal | 857846 | 27725 | 6568204.74 | 4.22 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| IFG | 457410 | 19065 | 3433118.71 | 5.55 | 1.32 (1.30-1.34) | 1.07 (1.05-1.09) | 1.05 (1.03-1.07) | |

| DM | 399603 | 28972 | 2881142.97 | 10.06 | 2.40 (2.36-2.44) | 1.70 (1.67-1.73) | 1.58 (1.56-1.61) | |

| Death | Normal | 857846 | 66149 | 6652038.98 | 9.94 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| IFG | 457410 | 45975 | 3490148.71 | 13.17 | 1.33 (1.32-1.35) | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | 1.03 (1.02-1.05) | |

| DM | 399603 | 70520 | 2965646.58 | 23.78 | 2.41 (2.39-2.44) | 1.61 (1.60-1.63) | 1.60 (1.58-1.62) | |

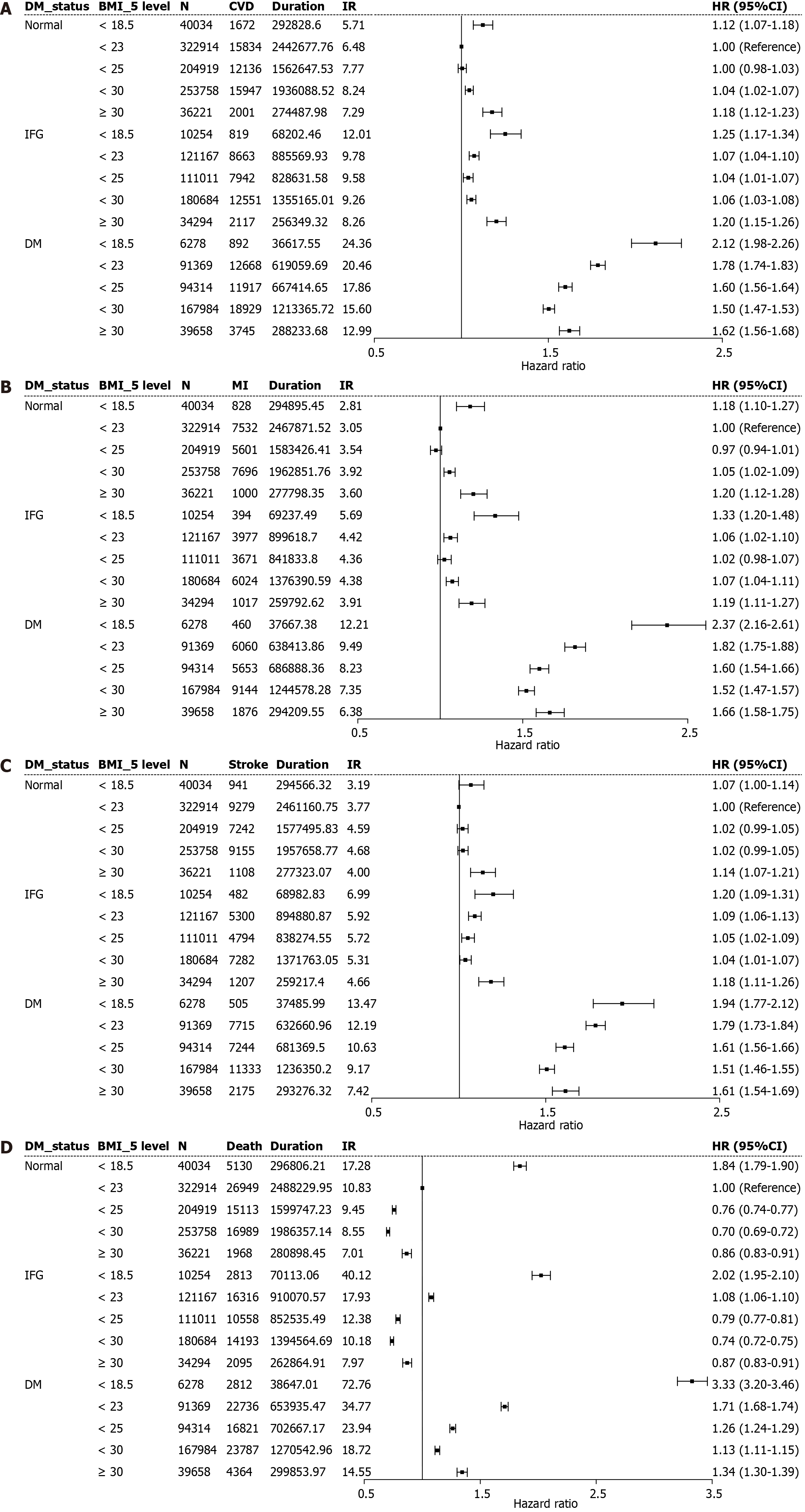

Table 5 and Figure 2 illustrate the synergistic associations of glycemic status and BMI categories with incident CV outcomes. Across all BMI groups, participants with diabetes exhibited higher risks of CVD, MI, stroke, and all-cause mortality than their normoglycemic counterparts within the corresponding BMI category. Both underweight individuals (< 18.5 kg/m2) and those classified as obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) displayed increased risks, with these associations being most pronounced among those with diabetes. Among participants without diabetes, those who were overweight, along with individuals with mild obesity, yielded the lowest risk of all-cause mortality; however, the presence of diabetes was consistently associated with an elevated risk, irrespective of BMI. These findings underscore the additive impact of diabetes and abnormal BMI on adverse CV outcomes.

| Outcome | BMI status (kg/m2) | n | Events (n) | Duration, PY | IR, per 1000 | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| CVD | < 18.5 | 56566 | 3383 | 397648.60 | 8.51 | 0.91 (0.88-0.94) | 1.10 (1.07-1.14) | 1.12 (1.08-1.16) |

| < 23 | 535450 | 37165 | 3947307.38 | 9.42 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| < 25 | 410244 | 31995 | 3058693.76 | 10.46 | 1.11 (1.09-1.13) | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | |

| < 30 | 602426 | 47427 | 4504619.24 | 10.53 | 1.12 (1.10-1.13) | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | |

| ≥ 30 | 110173 | 7863 | 819070.98 | 9.60 | 1.02 (1.00-1.05) | 1.25 (1.22-1.28) | 1.11 (1.08-1.14) | |

| MI | < 18.5 | 56566 | 1682 | 401800.32 | 4.19 | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | 1.18 (1.12-1.24) | 1.20 (1.14-1.26) |

| < 23 | 535450 | 17569 | 4005904.07 | 4.39 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| < 25 | 410244 | 14925 | 3112148.57 | 4.80 | 1.09 (1.07-1.12) | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | 0.95 (0.93-0.97) | |

| < 30 | 602426 | 22864 | 4583820.63 | 4.99 | 1.13 (1.11-1.16) | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | |

| ≥ 30 | 110173 | 3893 | 831800.52 | 4.68 | 1.07 (1.03-1.11) | 1.27 (1.23-1.32) | 1.12 (1.08-1.16) | |

| Stroke | < 18.5 | 56566 | 1928 | 401035.13 | 4.81 | 0.87 (0.83-0.91) | 1.04 (0.99-1.09) | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) |

| < 23 | 535450 | 22294 | 3988702.59 | 5.59 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| < 25 | 410244 | 19280 | 3097139.88 | 6.23 | 1.11 (1.09-1.13) | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | |

| < 30 | 602426 | 27770 | 4565772.03 | 6.08 | 1.09 (1.07-1.11) | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | |

| ≥ 30 | 110173 | 4490 | 829816.79 | 5.41 | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | 1.22 (1.18-1.26) | 1.09 (1.05-1.12) | |

| Death | < 18.5 | 56566 | 10755 | 405566.28 | 26.52 | 1.65 (1.62-1.68) | 1.86 (1.82-1.90) | 1.83 (1.79-1.87) |

| < 23 | 535450 | 66001 | 4052235.98 | 16.29 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| < 25 | 410244 | 42492 | 3154949.89 | 13.47 | 0.82 (0.81-0.83) | 0.75 (0.74-0.76) | 0.76 (0.75-0.77) | |

| < 30 | 602426 | 54969 | 4651464.79 | 11.82 | 0.72 (0.71-0.73) | 0.71 (0.71-0.72) | 0.70 (0.70-0.71) | |

| ≥ 30 | 110173 | 8427 | 843617.33 | 9.99 | 0.62 (0.60-0.63) | 0.92 (0.90-0.94) | 0.87 (0.85-0.89) | |

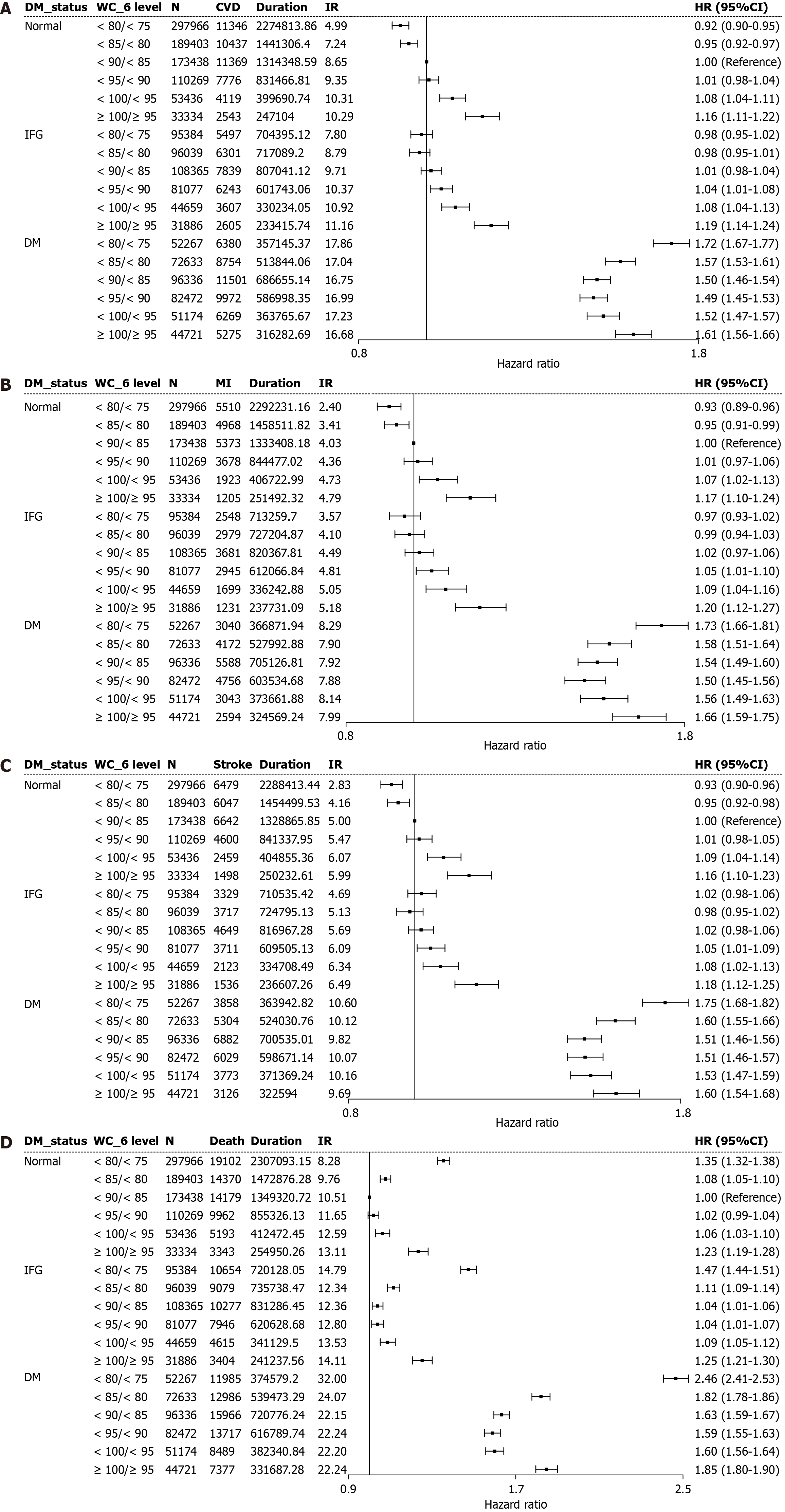

Table 6 and Figure 3 depict the synergistic influence of WC categories and glycemic status on incident CV events. Higher WC values were linked to progressively increasing risks of CVD, MI, stroke, and all-cause mortality, with the strongest associations observed among individuals with diabetes. Within each WC category, those with diabetes exhibited higher risks than those without, with the combination of high WC values and diabetes conferring the greatest hazard. Notably, even within “lower WC value” groups, the presence of diabetes was associated with significantly elevated event rates and mortality, emphasizing the combined adverse effects of central obesity and diabetes on CV outcomes.

| Outcome | WC status (cm) | n | Events (n) | Duration, PY | IR, per 1000 | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| CVD | < 80/< 75 | 445617 | 23223 | 3336354.36 | 6.96 | 0.64 (0.63-0.65) | 0.91 (0.90-0.93) | 0.96 (0.95-0.98) |

| < 85/< 80 | 358075 | 25492 | 2672239.66 | 9.54 | 0.87 (0.86-0.89) | 0.95 (0.94-0.97) | 0.97 (0.96-0.99) | |

| < 90/< 85 | 378139 | 30709 | 2808044.85 | 10.94 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| < 95/< 90 | 273818 | 23991 | 2020208.22 | 11.88 | 1.09 (1.07-1.11) | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | |

| < 100/< 95 | 149269 | 13995 | 1093690.46 | 12.80 | 1.17 (1.15-1.20) | 1.12 (1.10-1.14) | 1.07 (1.05-1.09) | |

| ≥ 100/≥ 95 | 109941 | 10423 | 796802.43 | 13.08 | 1.20 (1.18-1.23) | 1.26 (1.23-1.29) | 1.17 (1.15-1.20) | |

| MI | < 80/< 75 | 445617 | 11098 | 3372362.79 | 3.29 | 0.64 (0.63-0.66) | 0.90 (0.88-0.92) | 0.95 (0.93-0.98) |

| < 85/< 80 | 358075 | 12119 | 2713709.57 | 4.47 | 0.87 (0.85-0.89) | 0.95 (0.92-0.97) | 0.97 (0.94-0.99) | |

| < 90/< 85 | 378139 | 14642 | 2858902.81 | 5.12 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| < 95/< 90 | 273818 | 11379 | 2060078.54 | 5.52 | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) | 1.02 (0.99-1.04) | |

| < 100/< 95 | 149269 | 6665 | 1116627.75 | 5.97 | 1.17 (1.14-1.20) | 1.12 (1.09-1.16) | 1.07 (1.04-1.11) | |

| ≥ 100/≥ 95 | 109941 | 5030 | 813792.65 | 6.18 | 1.21 (1.18-1.25) | 1.28 (1.23-1.32) | 1.18 (1.15-1.22) | |

| Stroke | < 80/< 75 | 445617 | 13666 | 3362891.68 | 4.06 | 0.64 (0.62-0.65) | 0.93 (0.91-0.95) | 0.98 (0.95-1.00) |

| < 85/< 80 | 358075 | 15068 | 2703325.42 | 5.57 | 0.87 (0.85-0.89) | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | |

| < 90/< 85 | 378139 | 18173 | 2846368.13 | 6.39 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| < 95/< 90 | 273818 | 14340 | 2049514.23 | 7.00 | 1.10 (1.07-1.12) | 1.05 (1.03-1.07) | 1.03 (1.00-1.05) | |

| < 100/< 95 | 149269 | 8355 | 1110933.10 | 7.52 | 1.18 (1.15-1.21) | 1.12 (1.09-1.15) | 1.07 (1.05-1.10) | |

| ≥ 100/≥ 95 | 109941 | 6160 | 809433.86 | 7.61 | 1.20 (1.16-1.23) | 1.25 (1.22-1.29) | 1.17 (1.13-1.20) | |

| Death | < 80/< 75 | 445617 | 41741 | 3401800.39 | 12.27 | 0.88 (0.87-0.90) | 1.35 (1.33-1.37) | 1.36 (1.34-1.38) |

| < 85/< 80 | 358075 | 36435 | 2748088.03 | 13.26 | 0.95 (0.94-0.97) | 1.06 (1.05-1.08) | 1.07 (1.06-1.09) | |

| < 90/< 85 | 378139 | 40422 | 2901383.41 | 13.93 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |

| < 95/< 90 | 273818 | 31625 | 2092744.55 | 15.11 | 1.09 (1.07-1.10) | 1.02 (1.01-1.04) | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) | |

| < 100/< 95 | 149269 | 18297 | 1135942.79 | 16.11 | 1.16 (1.14-1.18) | 1.08 (1.06-1.10) | 1.05 (1.04-1.07) | |

| ≥ 100/≥ 95 | 109941 | 14124 | 827875.1 | 17.06 | 1.24 (1.21-1.26) | 1.30 (1.27-1.32) | 1.24 (1.22-1.27) | |

In this extensive nationwide CKD cohort, both glycemic status and measures of adiposity indices were found to jointly influence CV risk. The principal findings can be summarized as follows: Diabetes conferred the most prominent incremental risk of CVD and mortality across all BMI and WC categories, underscoring its central role in CV pathology in patients with CKD. Both abnormal BMI and WC were independently associated with adverse outcomes; nonetheless, their impact varied with glycemic status. In participants with normal glucose levels or IFG, underweight status and a high WC value were risk-enhancing factors, whereas in those with diabetes, paradoxically, low BMI and WC values were associated with the highest hazards. These results highlight the heterogeneity of CVD risk patterns in CKD and demonstrate the necessity of interpreting adiposity measures within the context of glycemic status.

Our findings reinforce and extend previous observations regarding the “obesity paradox” in CKD, where overweight individuals and those with mild obesity—particularly those without diabetes—occasionally exhibit lower mortality rates than their leaner counterparts[12-14]. Consistent with this phenomenon, our cohort demonstrated that overweight individuals and those with class I obesity, in the absence of diabetes, experienced the lowest mortality. Notwithstanding, the protective effect of a higher BMI diminished in the presence of diabetes, as CV risk remained elevated across all BMI and WC groups. These data support the notion that diabetes negates the benefits associated with increased adiposity, possibly through mechanisms involving insulin resistance, inflammation, and accelerated atherosclerosis[15,16].

The varying predictive value of BMI and WC was also evident in our cohort, underscoring the complementary roles of total and central adiposity. While BMI reflects overall adiposity, WC more accurately estimates visceral fat, which is metabolically active and strongly linked to CVD[17,18]. In CKD patients without diabetes, a high WC value proved to be a significant risk marker for CVD events. Conversely, among participants with diabetes, low BMI and WC values were both associated with an increased risk, likely reflecting malnutrition, sarcopenia, and unintentional weight loss—conditions prevalent in advanced CKD and diabetes[19-21]. These findings suggest that variations in body composition, including fat and muscle distribution, rather than simplistic measures of body weight or central obesity, are critical prognostic factors in diabetic CKD.

Clinically, our results underscore the necessity for individualized CV risk stratification in CKD, incorporating both glycemic status and adiposity patterns. Underweight or centrally lean CKD patients with diabetes should not be regarded as low risk, as they may represent a particularly frail and vulnerable subgroup. In contrast, targeting visceral obesity remains a key preventive strategy among CKD patients without diabetes owing to its strong association with adverse CV outcomes. These insights advocate for the tailoring of CVD prevention and management strategies according to both metabolic and body composition profiles.

This study, based on a nationwide CKD cohort of over two million individuals with comprehensive anthropometric and CV outcome data, provides robust evidence that both glycemic status and adiposity patterns jointly influence CV risk. The findings underscore the significance of personalized risk stratification, reflecting that underweight or centrally lean CKD patients with diabetes are particularly vulnerable and that visceral obesity remains a crucial focus in indi

In conclusion, the impact of adiposity on CVD risk was significantly modified by glycemic status. Notably, underweight individuals with diabetes exhibited the greatest vulnerability, indicating that leanness is not universally protective in CKD. These findings emphasize the imperativeness of incorporating both glycemic status and obesity phenotypes into individualized CVD risk assessments and prevention strategies for patients with comorbid diabetes and CKD.

| 1. | Marx-Schütt K, Cherney DZI, Jankowski J, Matsushita K, Nardone M, Marx N. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Eur Heart J. 2025;46:2148-2160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Swamy S, Noor SM, Mathew RO. Cardiovascular Disease in Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tao Z, Zuo P, Ma G. Association of weight-adjusted waist index with cardiovascular disease and mortality among metabolic syndrome population. Sci Rep. 2024;14:18684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang C, Lopes A, Britton A. Which adiposity index is best? Comparison of five indicators and their ability to identify type 2 diabetes risk in a population study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2025;225:112268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rhee EJ, Kwon H, Park SE, Han KD, Park YG, Kim YH, Lee WY. Associations among Obesity Degree, Glycemic Status, and Risk of Heart Failure in 9,720,220 Korean Adults. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44:592-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chang VW, Langa KM, Weir D, Iwashyna TJ. The obesity paradox and incident cardiovascular disease: A population-based study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bae EH, Lim SY, Han KD, Oh TR, Choi HS, Kim CS, Ma SK, Kim SW. Association Between Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure Variability and the Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease. Hypertension. 2019;74:880-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function--measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2001] [Cited by in RCA: 2115] [Article Influence: 105.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7065] [Cited by in RCA: 8619] [Article Influence: 391.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoon YS, Oh SW. Optimal waist circumference cutoff values for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity in korean adults. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2014;29:418-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Song WH, Bae EH, Ahn JC, Oh TR, Kim YH, Kim JS, Kim SW, Kim SW, Han KD, Lim SY. Effect of body mass index and abdominal obesity on mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: a nationwide, population-based study. Korean J Intern Med. 2021;36:S90-S98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kalantar-Zadeh K, Rhee CM, Chou J, Ahmadi SF, Park J, Chen JL, Amin AN. The Obesity Paradox in Kidney Disease: How to Reconcile it with Obesity Management. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2:271-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kalantar-Zadeh K, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Oreopoulos A, Noori N, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Krishnan M, Kopple JD, Mehrotra R, Anker SD. The obesity paradox and mortality associated with surrogates of body size and muscle mass in patients receiving hemodialysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:991-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Naderi N, Kleine CE, Park C, Hsiung JT, Soohoo M, Tantisattamo E, Streja E, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Moradi H. Obesity Paradox in Advanced Kidney Disease: From Bedside to the Bench. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61:168-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jung CH, Lee WJ, Song KH. Metabolically healthy obesity: a friend or foe? Korean J Intern Med. 2017;32:611-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ladhani M, Craig JC, Irving M, Clayton PA, Wong G. Obesity and the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:439-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, Santos RD, Arsenault B, Cuevas A, Hu FB, Griffin BA, Zambon A, Barter P, Fruchart JC, Eckel RH, Matsuzawa Y, Després JP. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1382] [Cited by in RCA: 1230] [Article Influence: 205.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chang KT, Chen CH, Chuang HH, Tsao YC, Lin YA, Lin P, Chen YH, Yeh WC, Tzeng IS, Chen JY. Which obesity index is the best predictor for high cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged and elderly population? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;78:165-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Navaneethan SD, Schold JD, Arrigain S, Kirwan JP, Nally JV Jr. Body mass index and causes of death in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016;89:675-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Macedo C, Amaral TF, Rodrigues J, Santin F, Avesani CM. Malnutrition and Sarcopenia Combined Increases the Risk for Mortality in Older Adults on Hemodialysis. Front Nutr. 2021;8:721941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim CS, Oh TR, Suh SH, Choi HS, Bae EH, Ma SK, Kim B, Han KD, Kim SW. Underweight status and development of end-stage kidney disease: A nationwide population-based study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023;14:2184-2195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/