Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112882

Revised: September 4, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 159 Days and 17 Hours

Fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were used to diagnose ges

To determine whether the diagnostic criteria used during the COVID-19 pan

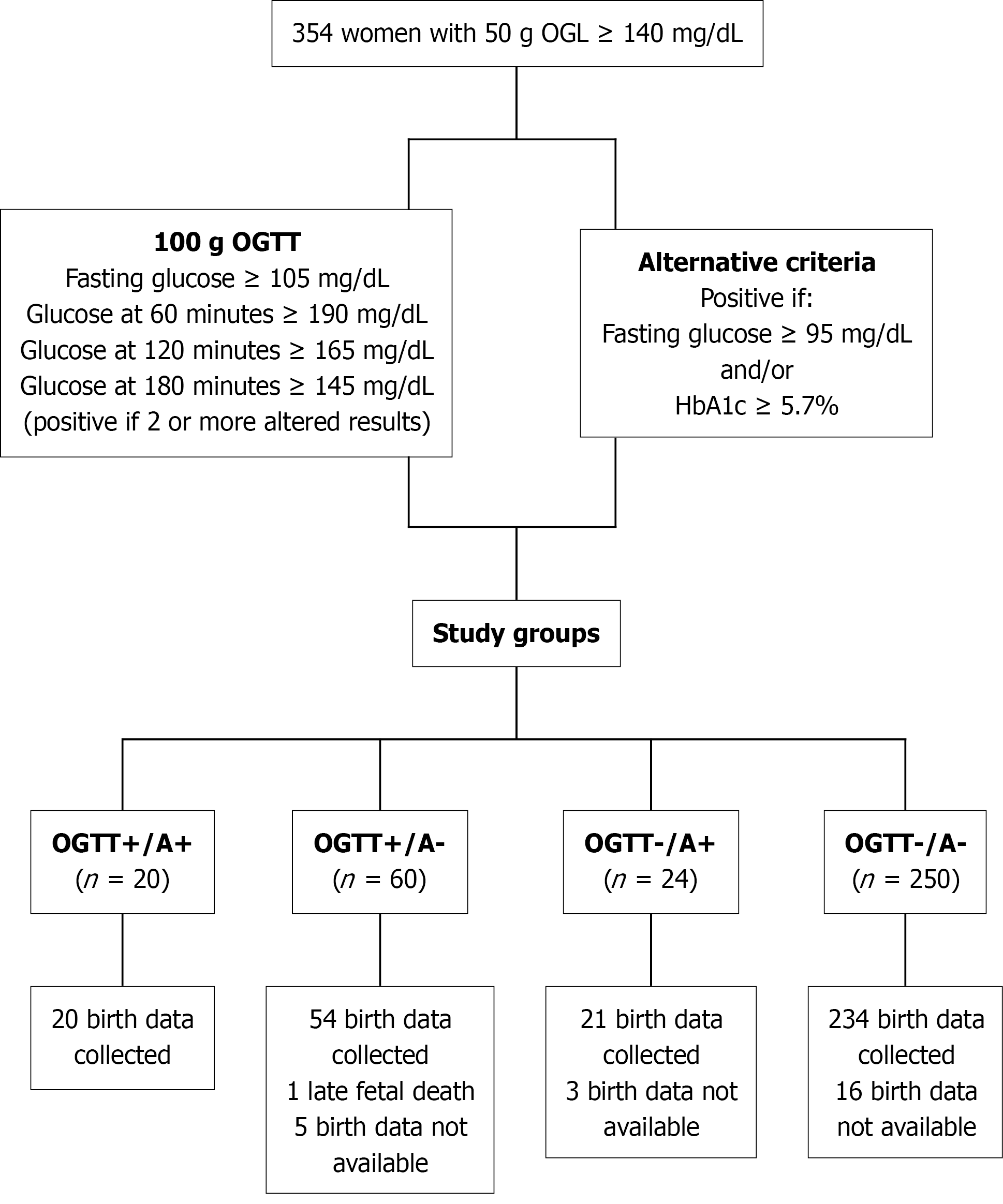

From May 2022 to July 2024, 354 females with an altered 50-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), the usual diagnostic test (100-g OGTT), and the alternative diagnostic (A) criteria (fasting glucose ≥ 95 mg/dL and/or HbA1c ≥ 5.7%) were tested simultaneously, resulting in four different groups: OGTT+/A+ (n = 20); OGTT+/A- (n = 60); OGTT-/A+ (n = 24); and OGTT-/A- (n = 250). Groups were compared for clinical characteristics and obstetric and perinatal outcomes.

Sensitivity of the alternative criteria was 25% and specificity was 91.2%. Body mass index (BMI) was similar from the OGTT-/A+ and OGTT+/A+ groups (30.1 ± 6.3 kg/m2 and 32.7 ± 5.3 kg/m2, respectively) and significantly higher from the OGTT+/A- and OGTT-/A- groups (26.8 ± 5.1 kg/m2 and 25.6 ± 5.0 kg/m2, respectively). The between-group differences were similar for the respective rates of large for gestational age (LGA) infants (OGTT+/A+: 38.9%, OGTT+/A-: 11.8%, OGTT-/A+: 29.4%, OGTT-/A-: 12.4%; P = 0.028). In the regression analysis a history of macrosomia [odds ratio (OR) = 7.948, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 2.269-27.842; P = 0.001] and higher pregestational BMI (OR = 1.069, 95%CI: 1.002-1.140; P = 0.042) independently increased the risk of LGA.

Despite insufficient validity to replace the OGTT, alternative criteria identify a group of patients with a higher risk profile and adverse perinatal outcomes who could benefit for health interventions.

Core Tip: Gestational diabetes is diagnosed by a two-step strategy: A screening test (O’Sullivan test) and a diagnostic test [100-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)]. The alternative criteria are based on glycated hemoglobin and fasting glucose, avoiding OGTT. Alternative criteria have sensitivity of 25.0% and specificity of 91.2%. Females with negative usual criteria (OGTT-) but who are alternative criteria positive have a high rate of obesity and large for gestational age babies. Although not valid enough to replace OGTT, alternative criteria should have a future role in the identification of this non-diagnosed high-risk group that could benefit from health interventions.

- Citation: Molina-Vega M, Estébanez-Prieto MJ, Fernández-Valero A, Lima-Rubio F, Fernández-Ramos AM, Linares-Pineda TM, Morcillo S, Picón-César MJ. Role of fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis: A prospective study. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 112882

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/112882.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112882

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is characterized by the presence of hyperglycemia initially detected during pregnancy[1]. It is a prevalent gestational metabolic disorder with a global standardized prevalence of 14%[2]. GDM has been associated with adverse perinatal and obstetric outcomes, including cesarean delivery and macrosomia, among others[1]. Additionally, it has been linked to an elevated risk of metabolic disorders and cardiovascular events during both the mother’s and offspring’s lifetime[3-5]. The diagnosis of GDM is not without contention, and various strategies have been employed over time to diagnose GDM.

While universal screening is currently recommended, there is no consensus on the optimal approach, either a one-step or two-step strategy. The one-step strategy involves a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) while the two-step strategy involves a screening test (50-g OGTT) followed by a diagnostic test (100-g OGTT) in cases where the initial screening test results are abnormal. The cutoff points for these tests vary according to the recommendation followed[6]. The one-step strategy results in a higher prevalence of GDM, identifying mild GDM (and preventing the potential consequences in mothers and offspring) unnoticed by the two-step strategy, which is more convenient at the socioeconomic level given the reduction in GDM prevalence using this strategy[7].

However, Hillier et al[8] demonstrated that despite a higher proportion of females being diagnosed with GDM using the one-step strategy there were no differences between groups in detecting perinatal and maternal complications, which is the most crucial quality that a diagnostic method should possess in the context of pregnancy. A recent meta-analysis comprising 54650 participants further corroborates these findings. The analysis, conducted by Gomes et al[9], revealed that females randomized to the one-step strategy exhibited higher incidences of neonatal hypoglycemia and neonatal intensive care unit admission compared with those randomized to the two-step strategy. Notably, there were no discernible differences in large for gestational age (LGA) neonates across both groups.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic posed a unique opportunity to investigate the impact of em

The objective of this study was to analyze the results of the concurrent application of both the prevailing and the alternative diagnostic (A) criteria for GDM. The investigation sought to elucidate whether FPG and HbA1c serve as a reliable alternative to the prevailing criteria or if they could play a role that justifies their use.

From May 2022 to July 2024, 354 females with an altered 50-g OGTT (O’Sullivan test) who were referred to the Diabetes and Pregnancy Unit of Hospital Virgen de la Victoria in Málaga, Spain, were recruited to participate in this study.

Inclusion criteria were: Maternal age 18-45 years; singleton pregnancy (primigravida and multigravida females) in the second or third trimester; and ability to provide informed consent. The study’s exclusion criteria encompassed females with multiple pregnancies, in the first trimester of pregnancy, or having a fasting glycemia level

Following established methods for sample size in diagnostic studies[14-16], we predefined precision targets as 95% confidence interval (95%CI) half-widths of ± 10% for sensitivity and ± 5% for specificity. Using Buderer’s formula[15] and assuming a sensitivity of 25%, specificity of 91%, and a disease prevalence of 22.6%, the required numbers were approximately 73 GDM cases and 123 non-cases, corresponding to a total of 323 OGTTs.

Following the Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo recommendations for the GDM diagnosis in our country (https://www.sediabetes.org/wp-content/uploads/GUIA-DIABETES-MELLITUS-Y-EMBARAZO.Nov-2020_V1.pdf) in females with a positive screening test for GDM [O’Sullivan test ≥ 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L)], it is mandatory to perform the diagnostic 100-g OGTT. According to the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) criteria[17], females with two or more altered points were considered to have GDM. The thresholds for FPG and glucose at 60 minutes, 120 minutes, and 180 minutes post-load were 105 mg/dL (5.8 mmol/L), 190 mg/dL (10.6 mmol/L), 165 mg/dL (9.2 mmol/L), and 145 mg/dL (8.0 mmol/L), respectively. In addition to the 100-g OGTT, HbA1c levels were simultaneously measured in all participants with the OGTT fasting blood sample. Females with a FPG level ≥ 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L) and/or HbA1c ≥ 5.7% were considered to have GDM as proposed during the COVID-19 pandemic[18]. These were considered the A criteria.

The population was divided into four distinct groups: OGTT+/A+ (females who met the NDDG and A criteria for the diagnosis of GDM); OGTT+/A- (females who met the NDDG criteria but not the A criteria); OGTT-/A+ (females who met the A criteria but not the NDDG criteria); and OGTT-/A- (females who were negative for GDM according to both criteria). Age, medical, obstetric and gynecological history, current pharmacological treatment, weight previous to pregnancy, family history of diabetes, and occurrence of macrosomy in previous newborns (defined as birthweight ≥ 4000 g) were collected during the recruitment visit. Moreover, weight and height were measured by standardized procedures. Only females with OGTT+ received recommendations about lifestyle changes and performed self-blood glucose monitoring at fasting and 1 hour after meals. Insulin therapy was indicated in females who in spite of performing lifestyle modifications glycemic control goals were not achieved. Females from the OGTT-/A+ group did not receive any intervention.

The type of delivery (vaginal, instrumental, or cesarean) and gestational age, birthweight and length, and perinatal complications data were extracted from the digital clinical histories. As perinatal complications are rare, a variable named “any perinatal complication” was created and included: Obstetric trauma; hypoglycemia; jaundice requiring pho

Birthweight percentile was calculated using a pediatric website (https://www.webpediatrica.com/endocrinoped/antropometria.php), which has a calculator based on Spanish population studies (https://www.seep.es/images/site/publicaciones/oficialesSEEP/Estudios_Espa%C3%B1oles_de_Crecimiento_2010.pdf). LGA referred to infants whose birthweight met or exceeded the 90th percentile. Small for gestational age referred to infants whose birthweight was below the 10th percentile. All births occurring before the completion of 37 weeks of pregnancy were considered a preterm birth. To calculate the risk of GDM, we employed a tool (https://www.evidencio.com/models/show/2106) based on the study from Teede et al[19].

Blood samples were taken at 8 am via antecubital venipuncture after a 12-hour fast. HbA1c and FPG were determined in this first blood sample. Later, the females took a glucose 100-g commercial reparation, and blood samples were collected at 60 minutes, 120 minutes, and 180 minutes. Vacuette® FX Sodium Fluoride/Potassium Oxalate PREMIUM tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC, United States) were used. Females were only allowed to drink water and were not permitted to exercise. During the 30 minutes after the collection, blood samples were centrifuged. Glucose levels were measured in a Dimension Vista Analyzer (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) using the glucose oxidase method (within-run and between-run precision was 1%-2%). The HbA1c levels were analyzed in an ADAMS A1c (HA-8180V) analyzer (Menarini, Florence, Italy) using high-pressure liquid chromatography.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), the positive likelihood ration (LR+) and the negative likelihood ratio (LR-) with 95%CIs of the A criteria for the diagnosis of GDM were calculated by MedCalc [MedCalc Software Ltd. (2025). Diagnostic Test Evaluation Calculator. https://www.medcalc.org/calc/diagnostic_test.php].

Categorical variables were expressed as n (%). Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD. We performed the analysis of variance test to compare quantitative variables between groups, while the χ2 test was used in order to compare the qualitative variables between groups. Missing values for the main predictors and outcome were minimal (< 10%), and we therefore used complete-case analysis. For the multivariable analysis all variables that were either significant in univariate analysis or considered clinically relevant [such as pregestational body mass index (BMI), weight gain, previous macrosomia, FPG, HbA1c, and alternative criteria status] were included. After model reduction based on the Akaike information criterion, only pregestational BMI and previous macrosomia remained as independent predictors of LGA. Model diagnostics included assessment of linearity in the logit for continuous variables (Box-Tidwell test), evaluation of multicollinearity (variance inflation factors with value < 2 were considered acceptable), and analysis of influential observations (Cook’s distance, threshold D > 1). Calibration was evaluated by reporting calibration-in-the-large and calibration slope. As calibration was assessed in the same cohort used to develop the model, these results represent apparent calibration.

The statistical significance of the results was set at P < 0.05. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 15.0 for Windows; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

A total of 354 pregnant females were included in this study, and the flow chart illustrates the procedure for assigning patients to the study groups (Figure 1). Birth data were not available for 25 females because the births took place in another city or at a private facility whose medical databases were unavailable to us. One late fetal death occurred at 22 weeks of pregnancy. Consequently, we obtained data from 329 births.

Of the 24 females in the OGTT-/A+ group, 9 patients were assigned based solely on the FPG criterion, 13 patients were assigned based solely on the HbA1c criterion, and 2 patients were assigned based on both criteria.

Utilizing the 100-g OGTT as the gold standard, the study calculated sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, LR+ and LR- of the A criteria for the diagnosis of GDM, according to data shown in Table 1. Sensitivity was 25.0% (95%CI: 15.9%-35.9%), specificity was 91.2% (95%CI: 87.2%-94.3%), PPV was 45.4% (95%CI: 32.7%-58.8%), NPV was 80.6% (95%CI: 78.5%-82.6%), LR+ was 2.85 (95%CI: 1.67-4.89) and LR- was 0.82 (95%CI: 0.72-0.94).

| Alternative criteria | 100-g OGTT | ||

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 20 | 24 | 44 |

| Negative | 60 | 250 | 310 |

| Total | 80 | 274 | 354 |

Receiver operating characteristic analysis using OGTT as reference showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.664 (SE = 0.037, 95%CI: 0.592-0.736, P < 0.001) for FPG and 0.647 (SE = 0.035, 95%CI: 0.578-0.716, P < 0.001) for HbA1c. The logistic model combining both markers yielded an AUC of 0.681 (SE = 0.035, 95%CI: 0.613-0.750, P < 0.001). Pairwise DeLong tests indicated no statistically significant differences among the three AUCs. These results suggest that FPG and HbA1c, either alone or in combination, provide only modest discrimination compared with OGTT.

As illustrated in Table 2, the study population’s characteristics and the comparisons between groups at baseline and regarding obstetric and perinatal outcomes are presented. Our findings indicate that females from the OGTT-/A+ group exhibited a comparable BMI to those from the OGTT+/A+ group yet significantly higher than those from the OGTT+/A- and OGTT-/A- groups. Additionally, the risk of GDM (according to the tool used to calculate it) was similar between females from OGTT+/A+ and OGTT-/A+ and between females from OGTT+/A- and OGTT-/A+. However, the risk was significantly higher in OGTT+/A+ compared with OGTT+/A- and significantly lower in OGTT-/A- compared with all the other groups. While significant variations in the O’Sullivan test and post-100-g glucose load were observed among the study groups, focusing on the data utilized for the diagnosis of GDM according to the A criteria, the highest FPG was observed in the OGTT+/A+ group, followed by the OGTT-/A+ group. With respect to HbA1c, it was found to be similar between the OGTT+/A+ and OGTT-/A+ groups and significantly higher than that observed in the other groups.

| Parameter | OGTT+/A+ (n = 20) | OGTT+/A- (n = 54) | OGTT-/A+ (n = 21) | OGTT-/A- (n = 234) | P value |

| Age (years) | 33.1 ± 4.2 | 33.7 ± 5.5 | 33.7 ± 5.1 | 33.8 ± 5.1 | 0.959 |

| Pregestational BMI (kg/m2) | 30.1 ± 6.3c | 26.8 ± 5.1b | 32.7 ± 5.3a,c | 25.6 ± 5.0b,d | < 0.001 |

| Pregestational obesity prevalence (%) | 40.0 | 28.3 | 70.8 | 18.0 | < 0.001 |

| Pregnancy weight gain (kg) | 5.5 ± 5.8 | 6.4 ± 5.6 | 5.2 ± 6.5 | 6.3 ± 4.3 | 0.666 |

| Past pregnancies (%) | 80.0 | 57.6 | 58.3 | 59.6 | 0.320 |

| Previous abortions (%) | 30.0 | 37.3 | 37.5 | 37.8 | 0.924 |

| Family history on DM (%) | 30.0 | 36.7 | 37.5 | 39.6 | 0.842 |

| Personal history GDM (%) | 36.8 | 25.0 | 22.2 | 15.2 | 0.088 |

| Previous macrosomic newborns (%) | 21.1 | 0 | 16.7 | 7.3 | 0.016 |

| Risk of GDM (%) | 22.5 ± 23.4a | 14.6 ± 18.4b | 16.7 ± 14.6a,b | 10.1 ± 12.4c | < 0.001 |

| O’Sullivan test (mg/dL) | 183.3 ± 32.1a,b,c | 168.3 ± 21.1c,d | 165.9 ± 29.8d | 156.9 ± 14.7a,d | < 0.001 |

| Gestational age at 100-g OGTT (weeks) | 25.9 ± 4.9 | 26.3 ± 3.7 | 25.0 ± 6.2 | 25.5 ± 4.6 | 0.541 |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 106.3 ± 14.4a,b,c | 83.5 ± 6.4b,d | 94.3 ± 6.7a,c,d | 81.3 ± 5.7b,d | < 0.001 |

| 60 minutes glucose (mg/dL) | 206.6 ± 39.5b,c | 193.8 ± 26.1b,c | 166.2 ± 25.2a,d | 154.4 ± 26.8a,d | < 0.001 |

| 120 minutes glucose (mg/dL) | 186.7 ± 28.2b,c | 179.1 ± 20.5b,c | 146.7 ± 20.0a,c,d | 129.3 ± 24.4a,b,d | < 0.001 |

| 180 minutes glucose (mg/dL) | 142.3 ± 27.9b,c | 139.5 ± 32.8b,c | 113.6 ± 24.2a,d | 105.4 ± 27.1a,d | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.6 ± 0.4a,c | 5.1 ± 0.2b,c,d | 5.5 ± 0.3a,c | 5.0 ± 0.2a,b,d | < 0.001 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.8 ± 1.2 | 38.8 ± 1.2 | 38.7 ± 1.9 | 38.9 ± 1.7 | 0.957 |

| Preterm birth (%) | 5.0 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 0.925 |

| Birthweight (g) | 3326.7 ± 528.2a,c | 3157.8 ± 397.9d | 3505.8 ± 592.0 | 3221.7 ± 493.9d | 0.001 |

| Birthweight percentile | 72.6 ± 27.3a,c | 46.8 ± 28.2b,d | 72.3 ± 23.7a | 52.9 ± 28.8d | < 0.001 |

| SGA/LGA (%) | 5.0/35.0 | 9.2/11.1 | 0/28.6 | 6.4/13.7 | 0.028 |

| Birth length (cm) | 51.2 ± 2.0a | 49.2 ± 3.3d | 50.6 ± 2.4 | 50.0 ± 2.4 | 0.033 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 34.4 ± 1.5 | 33.5 ± 1.5 | 34.0 ± 1.9 | 33.5 ± 1.6 | 0.175 |

| Sex of newborn | 0.837 | ||||

| Female (%) | 50.0 | 51.0 | 41.2 | 45.0 | |

| Male (%) | 50.0 | 49.0 | 58.8 | 55.0 | |

| Induction of labor (%) | 30.0 | 27.7 | 33.3 | 22.6 | 0.789 |

| Type of delivery | 0.223 | ||||

| Noninstrumental vaginal (%) | 31.6 | 66.0 | 52.9 | 52.6 | |

| Instrumental (%) | 10.5 | 8.0 | 11.8 | 13.1 | |

| Cesarean (%) | 57.9 | 26.0 | 35.3 | 34.3 | |

| Any perinatal complication (%) | 25.0 | 17.3 | 14.3 | 13.2 | 0.503 |

Birthweight and birthweight percentile exhibited congruence between the OGTT+/A+ and OGTT-/A+ groups while analogous findings were observed between the OGTT+/A- and OGTT-/A- groups. When comparing birthweight and birthweight percentile between primigravida and multigravida females, we observed these variables to be higher in multigravida females among the whole study population and these differences remained significant in the OGTT+/A+ and OGTT+/A- groups, but no differences were observed regarding parity in females from the OGTT-/A+ and OGTT-/A- groups (data not shown).

The prevalence of LGA was most pronounced in the OGTT+/A+ group with the OGTT-/A+ group exhibiting a close second. However, disparities in the modality of delivery or the “any perinatal complication” variable remained non-existent.

In order to examine factors associated with LGA newborns, univariate logistic regression was performed. Accordingly, females A+ were found to present a 4.291-fold higher risk for LGA than those with A-. Having previous macrosomic newborns increased the risk of LGA near 7 times in comparison with not having previous macrosomic newborns in the univariate regression analysis. The analysis further revealed that pregestational BMI, pregnancy weight gain, and FPG were independently associated with LGA newborns. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the optimal model with a Nagelkerke R2 of 0.167 demonstrated that the antecedent of macrosomic newborns retained significance with a 7.948-fold higher risk for LGA in females with this antecedent compared with those without it. Also, pregestational BMI was independently related to the occurrence of LGA. The findings from both univariate and multivariate logistic re

| Independent variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.995 | 0.938-1.056 | 0.877 | |||

| Gestational age at test (weeks) | 1.044 | 0.971-1.123 | 0.245 | |||

| Parity | ||||||

| Primigravida | 1 (reference) | |||||

| Multigravida | 1.860 | 0.956-3.610 | 0.066 | |||

| OGTT status | 0.631 | |||||

| OGTT negative | 1 (reference) | |||||

| OGTT positive | 1.183 | 0.592-2.374 | ||||

| A criteria status | 0.001 | |||||

| A negative | 1 (reference) | |||||

| A positive | 4.291 | 1.814-10.153 | ||||

| Pregestational BMI (kg/m2) | 1.071 | 1.016-1.128 | 0.010 | 1.069 | 1.002-1.140 | 0.042 |

| Pregnancy weight gain (kg) | 1.068 | 1.002-1.138 | 0.042 | |||

| Personal history of GDM | 0.224 | |||||

| No | 1 (reference) | |||||

| Yes | 1.826 | 0.692-4.819 | ||||

| Previous macrosomic newborns | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||

| Yes | 6.897 | 2.183-21.788 | 7.948 | 2.269-27.842 | 0.001 | |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 1.065 | 1.025-1.108 | 0.001 | |||

| HbA1c (%) | 1.745 | 0.654-4.653 | 0.266 | |||

| Treatment for GDM | 0.521 | |||||

| Diet | 1 (reference) | |||||

| Insulin | 1.507 | 0.431-5.273 | ||||

All variance inflation factors were < 2, indicating low collinearity. No significant departures from linearity in the logit were detected, and no influential cases were identified (all Cook’s distances < 1). The model showed good calibration with calibration-in-the-large equal to 0.00 and a calibration slope of 1.00 (95%CI: 0.57-1.43). The mean predicted risk (0.19) closely matched the observed incidence of LGA (0.19) with some variability across intermediate deciles due to limited sample size.

In this study we found that females who met the A criteria for the diagnosis of GDM but not the conventional criteria exhibited a profile similar to those who met both sets of criteria. These females were more obese and had a higher prevalence of LGA newborns compared with those who only met the usual criteria for GDM diagnosis. Although only a history of macrosomic newborns and a higher pregestational BMI were independently associated with the presence of LGA newborns in multivariate analysis, the A criteria could play a role in the diagnosis of GDM, helping to identify pregnancies at higher risk.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a unique opportunity to evaluate a variety of approaches for the diagnosis of GDM with a focus on the use of FPG, RPG, and HbA1c levels. Prior to this there was a prevailing association between HbA1c and adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes[20-22], leading to its consideration as a diagnostic tool for GDM. However, the low sensitivity of HbA1c for detecting GDM (5% for HbA1c ≥ 5.7% and 9% for HbA1c ≥ 5.9%[20]) led most societies to prefer a combined approach with FPG, which also has a low sensitivity on its own[10,23]. In the present population the sensitivity of the A criteria (HbA1c ≥ 5.7% and/or FPG ≥ 95 mg/dL) was 25.0% while the specificity was 91.2%. The observed sensitivity in the present population was lower than that observed in the pregnancy and infant development study cohort. In that cohort the combination of HbA1c levels ≥ 5.7% and/or FPG levels ≥ 92 mg/dL was found to have a sensitivity of 51% for GDM[23].

When considering only HbA1c, Amaefule et al[24] reported an sensitivity of 36% and an specificity of 90% at a cutoff of 5.7% during the second or third trimester of pregnancy, showing similarity to the observations made in this study. Conversely, Rayis et al[25] documented a sensitivity of 13.24% and a specificity of 91.43% at an HbA1c level of 5.85% in a population of 348 females at 26.26 ± 2.43 weeks of pregnancy. Negrea et al[26] found an sensitivity of 12% and an specificity of 99.4% at an HbA1c level of 5.5% in a population of 312 females at 24-28 weeks of pregnancy. In summary, our sensitivity and specificity results are quite similar to those previously reported.

With respect to maternal characteristics, it was observed that females from the OGTT-/A+ group exhibited sig

In fact, in our population, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that higher pregestational BMI increased the risk of LGA. Concurrently, maternal risks associated with obesity encompass a higher prevalence of GDM, hypertensive disorders, or cesarean section, accompanied by elevated perioperative complications[27]. In a related finding Negrea et al[26] observed that females classified as GDM according to HbA1c ≥ 5.5% exhibited a higher BMI compared with those with lower levels of HbA1c although not meeting obesity criteria (28.3 kg/m2vs 25.3 kg/m2, P < 0.01). The study also reported that females with HbA1c ≥ 5.5% exhibited a higher prevalence of family history of diabetes and older age but not more history of GDM, contrasting with our findings.

In a similar vein, a retrospective study involving 2048 females with GDM[28] demonstrated that those with HbA1c ≥ 5.5% exhibited a higher prevalence of obesity compared with those with HbA1c < 5.5%. While this study also reported females with HbA1c ≥ 5.5% to be older than those with HbA1c < 5.5%, similar to the findings of Negrea et al[26], no such difference in age was observed between the groups in our population. Consequently, we hypothesize that higher HbA1c in females with GDM may be indicative of a higher-risk profile among patients.

A focused examination of obstetric and perinatal outcomes revealed that newborns from the OGTT-/A+ group exhibited increased mean weight and length and a higher prevalence of LGA, analogous to the OGTT+/A+ group and significantly higher than those from the OGTT+/A- and OGTT-/A- groups. Univariate logistic regression analysis indicated that females with A+ exhibited a 4-fold elevated risk of delivering an LGA newborn. While this association was not statistically significant in the multivariate regression analysis within our population, it is a well-documented re

In a recent meta-analysis including 17711 females with GDM at 24-28 weeks of pregnancy, Mou et al[13] found that the relative risk of LGA was 1.70 (95%CI: 1.23-2.35, P = 0.001) in females with HbA1c ≥ 5.5% vs females with HbA1c < 5%. Despite the absence of a statistically significant impact of the study group on the prevalence of cesarean section or any perinatal complication in our population, a study by Muhuza et al[28] demonstrated a notable association between HbA1c ≥ 5.5% and an elevated risk of macrosomia, preterm birth, and cesarean section. However, it is important to note that a high birth weight is not only associated with obstetric and perinatal risks. It also appears to be related to an increased risk of certain malignancies in childhood, breast cancer, several psychiatric disorders, hypertension in childhood, and type 1 and 2 diabetes[29]. This finding underscores the need for further research in this area.

It is important to highlight that the A criteria employed in our population are predicated on both HbA1c and FPG. In fact, 37.5% of patients were classified as OGTT-/A+ based solely on FPG criteria, and FPG has been associated with a higher propensity for adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes. Tennant et al[30] observed an increase of 200 g in birthweight, a 2-fold increase in the risk of LGA, and a 3-fold increase in the risk of shoulder dystocia for each additional 18 mg/dL in FPG in a cohort of 7062 pregnant females who were screened for GDM. Of particular significance is the observation that females with elevated FPG yet not sufficiently high to meet the diagnostic criteria for GDM (in the context of the study population, between 92 and 100 mg/dL) exhibited the highest risk. These females did not benefit from the care received by females with GDM. It is conceivable that a similar phenomenon may occur in our population. It can be hypothesized that females from the OGTT-/A+ group may benefit from health interventions, including dietary advice.

Finally, we would like to note that only the history of macrosomic newborn and a higher pregestational BMI (as previously described), both well-known risk factors for LGA[31], remained significantly related to the occurrence of LGA in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Specifically, females with a history of macrosomic newborns had a 7.948-fold increased risk of LGA compared with those without this antecedent.

The present study boasted several notable strengths; the foremost of which is its prospective design, a notable departure from the majority of extant literature on this subject, which is largely based on retrospective studies. Fur

The A criteria appeared to lack sufficient validity to supersede the two-step strategy for diagnosing GDM. However, we posit that incorporating them into the prevailing protocol could facilitate the identification of a cohort of pregnant females who are currently not being recognized and who are at an elevated risk. These individuals may potentially benefit from intervention to avert the occurrence of LGA newborns.

| 1. | Ye W, Luo C, Huang J, Li C, Liu Z, Liu F. Gestational diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;377:e067946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 129.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang H, Li N, Chivese T, Werfalli M, Sun H, Yuen L, Hoegfeldt CA, Elise Powe C, Immanuel J, Karuranga S, Divakar H, Levitt N, Li C, Simmons D, Yang X; IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy Special Interest Group. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Estimation of Global and Regional Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevalence for 2021 by International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group's Criteria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 700] [Article Influence: 175.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xie W, Wang Y, Xiao S, Qiu L, Yu Y, Zhang Z. Association of gestational diabetes mellitus with overall and type specific cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;378:e070244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, Tan BK, Davies MJ, Gillies CL. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 712] [Article Influence: 118.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bianco ME, Josefson JL. Hyperglycemia During Pregnancy and Long-Term Offspring Outcomes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kuo CH, Li HY. Diagnostic Strategies for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Review of Current Evidence. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moon JH, Jang HC. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Diagnostic Approaches and Maternal-Offspring Complications. Diabetes Metab J. 2022;46:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Ogasawara KK, Vesco KK, Oshiro CES, Lubarsky SL, Van Marter J. A Pragmatic, Randomized Clinical Trial of Gestational Diabetes Screening. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:895-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gomes C, Futterman ID, Sher O, Gluck B, Hillier TA, Ramezani Tehrani F, Chaarani N, Fisher N, Berghella V, McLaren RA Jr. One-step vs 2-step gestational diabetes mellitus screening and pregnancy outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2024;6:101346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Molina-Vega M, Gutiérrez-Repiso C, Lima-Rubio F, Suárez-Arana M, Linares-Pineda TM, Cobos Díaz A, Tinahones FJ, Morcillo S, Picón-César MJ. Impact of the Gestational Diabetes Diagnostic Criteria during the Pandemic: An Observational Study. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kania M, Wilk M, Cyganek K, Szopa M. The effectiveness of selected temporary testing protocols for gestational diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2024;44 Suppl 1:61-68. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Casellas A, Martínez C, Amigó J, Ferrer R, Martí L, Merced C, Medina MC, Molinero I, Calveiro M, Maroto A, Del Barco E, Carreras E, Goya M; DIABECOVID STUDY Group. Evaluation of an Alternative Screening Method for Gestational Diabetes Diagnosis During the COVID-19 Pandemic (DIABECOVID STUDY): An Observational Cohort Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025;15:189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mou SS, Gillies C, Hu J, Danielli M, Al Wattar BH, Khunti K, Tan BK. Association between HbA1c Levels and Fetal Macrosomia and Large for Gestational Age Babies in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 17,711 Women. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hajian-Tilaki K. Sample size estimation in diagnostic test studies of biomedical informatics. J Biomed Inform. 2014;48:193-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 709] [Article Influence: 59.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Buderer NM. Statistical methodology: I. Incorporating the prevalence of disease into the sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:895-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 592] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Flahault A, Cadilhac M, Thomas G. Sample size calculation should be performed for design accuracy in diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:859-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. National Diabetes Data Group. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4004] [Cited by in RCA: 3899] [Article Influence: 83.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Codina M, Corcoy R, Goya MM; en representación del GEDE Consenso del Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo (GEDE); GEDE Consenso del Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo (GEDE). Update of the hyperglycemia Gestational diagnosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr (Engl Ed). 2020;67:545-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Teede HJ, Harrison CL, Teh WT, Paul E, Allan CA. Gestational diabetes: development of an early risk prediction tool to facilitate opportunities for prevention. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lowe LP, Metzger BE, Dyer AR, Lowe J, McCance DR, Lappin TR, Trimble ER, Coustan DR, Hadden DR, Hod M, Oats JJ, Persson B; HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study: associations of maternal A1C and glucose with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:574-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ye M, Liu Y, Cao X, Yao F, Liu B, Li Y, Wang Z, Xiao H. The utility of HbA1c for screening gestational diabetes mellitus and its relationship with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;114:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sweeting AN, Ross GP, Hyett J, Molyneaux L, Tan K, Constantino M, Harding AJ, Wong J. Baseline HbA1c to Identify High-Risk Gestational Diabetes: Utility in Early vs Standard Gestational Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:150-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vambergue A, Jacqueminet S, Lamotte MF, Lamiche-Lorenzini F, Brunet C, Deruelle P, Vayssière C, Cosson E. Three alternative ways to screen for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. 2020;46:507-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Amaefule CE, Sasitharan A, Kalra P, Iliodromoti S, Huda MSB, Rogozinska E, Zamora J, Thangaratinam S. The accuracy of haemoglobin A1c as a screening and diagnostic test for gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test accuracy studies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:322-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rayis DA, Ahmed ABA, Sharif ME, ElSouli A, Adam I. Reliability of glycosylated hemoglobin in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Negrea MC, Oriot P, Courcelles A, Gruson D, Alexopoulou O. Performance of glycated hemoglobin A1c for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Belgium (2020-2021). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2023;289:36-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Reed J, Case S, Rijhsinghani A. Maternal obesity: Perinatal implications. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121231176128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Muhuza MPU, Zhang L, Wu Q, Qi L, Chen D, Liang Z. The association between maternal HbA1c and adverse outcomes in gestational diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1105899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Magnusson Å, Laivuori H, Loft A, Oldereid NB, Pinborg A, Petzold M, Romundstad LB, Söderström-Anttila V, Bergh C. The Association Between High Birth Weight and Long-Term Outcomes-Implications for Assisted Reproductive Technologies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:675775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tennant P, Doxford-Hook E, Flynn L, Kershaw K, Goddard J, Stacey T. Fasting plasma glucose, diagnosis of gestational diabetes and the risk of large for gestational age: a regression discontinuity analysis of routine data. BJOG. 2022;129:82-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mcmurrugh K, Vieira MC, Sankaran S. Fetal macrosomia and large for gestational age. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med. 2024;34:66-72. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/