Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112885

Revised: September 19, 2025

Accepted: November 28, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 159 Days and 3.3 Hours

China has the highest incidence of diabetes among all Asian countries, and environmental factors have a significant impact on the onset of diabetes. Lead is one of the important legacy environmental pollutants that disrupts endocrine function. Both lead and diabetes have damaging effects on the nervous system, while the gut microbiota is considered an important mediator of brain damage.

To determine the effects and underlying mechanisms of environmental lead ex

A mouse model of lead exposure and diabetes was used. Lead levels were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, and blood glucose levels were assessed. Immunofluorescence was used to analyze brain damage in mice. The Morris water maze was used for evaluating neural function. Neurotransmitters including vanillylmandelic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), and homovanillic acid (HVA) were quantified with high performance liquid chromatography. Proteomics analysis was conducted on hippocampal brain tissue, and gut microbiota analysis was performed on colonic fecal samples. PI3K and COX2 proteins were detected by Western blotting, and then glutathione (GSH) levels in brain tissue were mea

Mice in the lead-exposure diabetic model exhibited significantly elevated lead and blood glucose levels, with the most severe neural damage observed. The neurotransmitters DOPAC and HVA were markedly increased. Proteomics revealed that differential proteins were primarily involved in neural and metabolic pathways. Cor

The coexistence of lead exposure and diabetes has an interactive effect on neural damage. This interaction appears to affect the abundance of the gut microbe Sutterella, which, through inflammation, influences the expression of re

Core Tip: This study identified the additive effects of concurrent lead exposure and diabetes on neurotoxicity and provided a preliminary exploration of the mechanisms by which the gut microbiota regulated the brain differential protein expression and ultimately affected neurological function, based on proteomics and gut microbiota analysis.

- Citation: Ding WJ, Liu CQ, Tang XY, Shang ZB, Liang X, Tao T, Liu RX, Jiang QY, Qiu YF, Sun Y. Role of gut microbiota in lead-induced neural damage in diabetic mice. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 112885

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/112885.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112885

China is one of the countries experiencing a sharp rise in diabetes prevalence[1]. According to data from the International Diabetes Federation, it is estimated that by 2030, 578 million people in China will have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). It is expected that by 2045, this number will increase to 700 million[2]. Diabetes damages the nervous system, and the cognitive deficits associated with T2DM (diabetic encephalopathy), have become one of the growing complications[3,4]. In recent years, cognitive impairment and dementia have increasingly become complications of T2DM patients as their life expectancy increases[5]. This rapid growth trend is closely linked to China’s industrialization, urbanization, and lifestyle changes[6,7]. Besides, environmental exposure is also considered one of the key contributors to the rising pre

Lead is a significant and persistent environmental pollutant, with well-documented neurotoxic effects[10]. Addi

The gastrointestinal tract is an important toxicological target for lead. Moreover, lead intake may have an impact on the types and abundance of the gut microbiota, resulting in a reduction in beneficial bacteria[15]. Lead accumulation and its toxic effects in the body can be caused by changes in the gut microbiome, which may affect the body's lead level and metabolism[16]. This imbalance may negatively impact host health, including increasing the risk of metabolic diseases. Alterations in gut microbial homeostasis and the production of metabolic byproducts may trigger increased intestinal inflammation and immune responses. Hence, insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism may be affected[17,18]. These may promote or aggravate T2DM. However, detailed studies on changes and consequences in the gut microbiome under simultaneous lead exposure and hyperglycemic conditions are still lacking.

Changes in the gut microbiome that cause alterations in host metabolic functions are also closely linked to the progression of cognitive disorders[19,20]. This highly complex system of gut-brain crosstalk not only maintains gas

Using a lead-exposed diabetic mouse model, this study integrated proteomics and gut microbiome analyses to investigate correlations between changes in brain function, protein expression profiles, and gut microbiome homeostasis. It aimed to explore the mechanisms and effects of neural damage induced by lead and hyperglycaemia via the gut-brain axis, thereby establishing new scientific foundations to prevent and manage diabetic complications.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Guilin Medical University for all experimental protocols (Investigation Number: GLMC-IACUC-20241088). We conducted all animal experiments in accordance with the EU Directive 2010/63/EU and the guidelines of the Chinese Society for Laboratory Animal Sciences on animal welfare and ethical review. All procedures related to animal research comply with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) C57BL/6J mice, aged 8-10 weeks, were purchased from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. [Production License Number: SCXK (Xiang) 2019-0004]. These experimental mice were conducted in SPF facilities with the temperature controlled at 22 ± 2 °C and humidity maintained at 40%-60%, under a 12-hour-light/dark cycle. They can freely obtain water and food.

A random sample of mice was divided into four groups: Control group (WTC), diabetes group (WTM), lead exposure group (WTH), and diabetes with lead exposure group (WTMH). A high-fat diet was fed to the diabetes and diabetes with lead exposure groups, and streptozotocin (STZ) was administered intraperitoneally. The other groups were injected with 0.01 mmol/L sodium citrate. After fasting for approximately 12 hours, the mice were intraperitoneally injected (60 mg/kg, in 0.01 mmol/L sodium citrate) for five consecutive days. The model mice were considered successful when they had a fasting blood glucose level of 11.1 mmol/L or higher. The WTH and WTMH groups were exposed to lead via drinking water containing 0.5% PbAC. The control and diabetes groups were given autoclaved water until the end of the exposure period.

The key reagents, antibodies, and instruments used in this study included STZ (China Solarbio, S8050), reduced glutathione colorimetric assay kit (Thermo Fisher, E-BC-K030-M), blood glucose meter (Sanofi, Anwen+), beta actin (China Sanying Biological, 20536-1-AP), PI3K (China Sanying Biological, 20584-1-AP), AKT (China Sanying Biological, 80455-1-RR); COX2 (China Sanying Biological, 66351-1-Ig), GFAP (Cell Signaling, E4 L7M), anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Cell Signaling), Digital Slide Scanner (3DHISTECH, Pannoramic 250); TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit (Illumina, United States), AlphaImager HP Gel Imaging Analysis System (ProteinSimple, United States); FluorChem M Multi-Color Fluorescence and Chemiluminescence Imaging System (ProteinSimple, United States), Varioskan LUX Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher, United States), Liquid Chromatography System (Agilent 1260, United States), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) (PerkinElmer NexION 2000), Easy-nLC 1200 Chromatography System (Thermo Fisher, United States), NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher, United States), and QuantiFluor (Promega, United States).

Mouse tail vein blood glucose levels were measured after a 12-hour fast. Blood glucose measurements were performed weekly, with statistical analysis conducted on glucose values obtained at four time points: Before the experiment (week 0), and at weeks 4, 8, and 12.

Brain tissue samples, which had been stored at -80 °C, were used for digestion. Approximately 15 mg of each sample was weighed and added to 200 μL of 65% HNO3. The mixture was vortexed for 30 seconds and then digested at 70 °C for 2 hours. After cooling to ambient temperature, 200 μL of 30% H2O2 was added, followed by vortexing for 30 seconds and a subsequent 12-hour treatment at 70 °C. Following that, the sample was vortexed for 30 seconds again and filtered through a 0.22 m syringe filter before being analyzed with ICP-MS. To calibrate, the lead standard solution was diluted with 1% nitric acid containing 0.05% Triton X-100 in order to prepare a 1000 g/L standard stock solution that was then used to construct a lead standard curve. With PerkinElmer NexION 2000 ICP-MS, the following conditions were used for the ICP-MS analysis: Sweeps 20, Reading 1, Replicates 3, Helium KED mode, and Helium Flow 4.

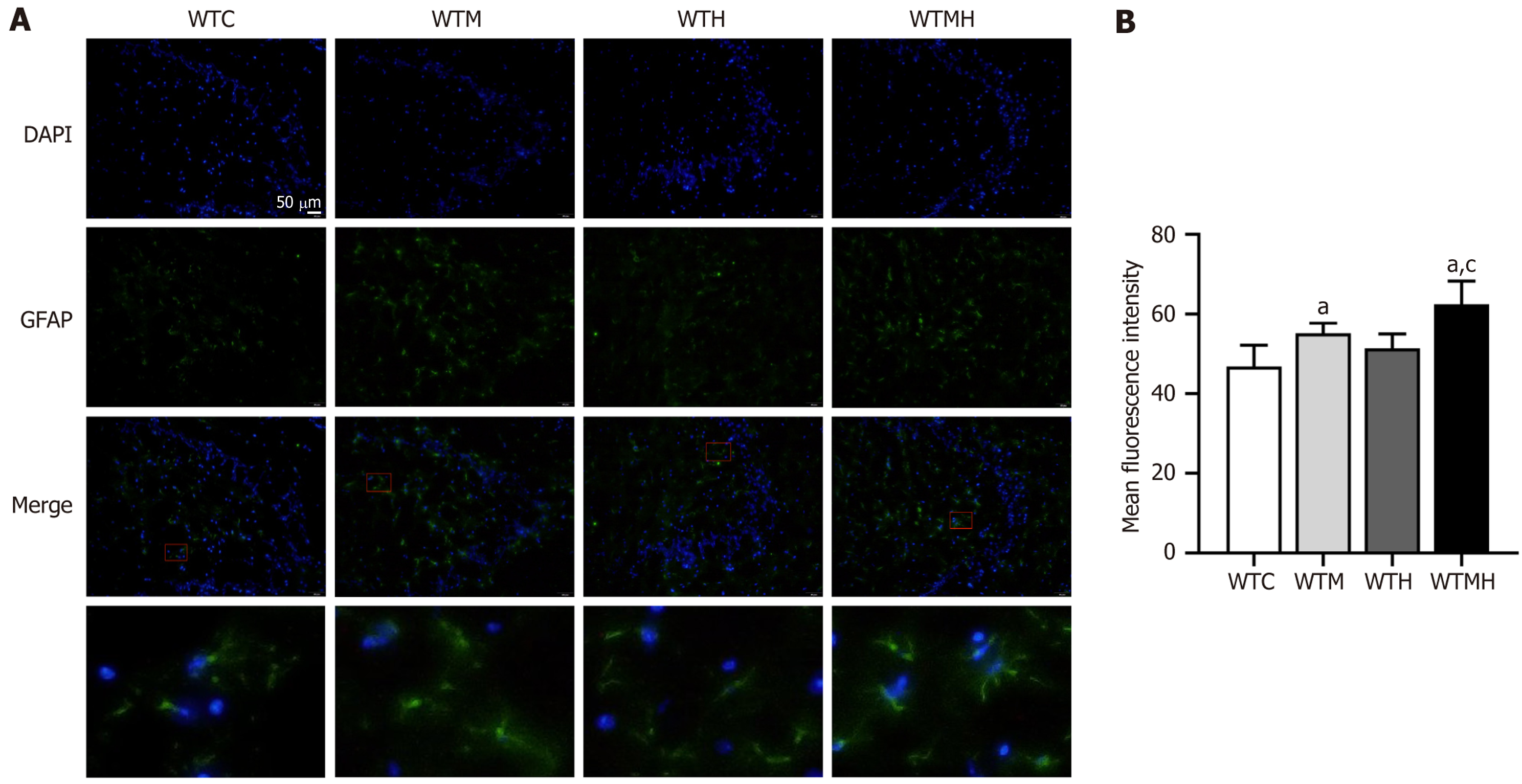

After embedding brain tissue in OCT compound, it was frozen at - 80 °C, sliced, and permeabilized with a 0.3% Triton X-100 solution. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature, sections were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 2-3 hours. Subsequently, they were incubated with a primary anti-GFAP antibody (1:200 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. The following day, sections were brought to room temperature and incubated for 1 hour, followed by three washes with PBS. A proportionally diluted secondary antibody was then applied, and the sections were incubated in the dark for 2 hours. After a final rinse with PBS at room temperature, cell nuclei were counterstained, and the sections were mounted with an anti-fade mounting medium. GFAP expression in the hippocampal tissue was finally observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Urine samples from each group of mice were collected using metabolic cages. A 100 µL aliquot of urine was filtered (45 μm) and then analysed. The chromatographic conditions were as follows: Aichrom Bond-AQ C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm), with methanol and 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (volume ratio 5:95) used as the mobile phase, at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. EX 280 nm and EM 315 nm wavelengths were detected, column temperature was set at 30 °C, injection volume was 10 µL, and the analysis took 20 minutes. Standard curves for each neurotransmitter were con

The mouse brain hippocampal tissues from each group were homogenized in an appropriate amount of SDT lysis buffer, subjected to boiling for 3 minutes, ultrasonicated for 2 minutes, and then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 4 °C at 16000 g. Protein quantification was conducted using the BCA assay. An aliquot of protein from each sample was processed for FASP digestion. A mixture of 9 µL peptide segments and 1 µL iRT peptides was used for each sample, and 2 µL of the mixture was injected for analysis. Chromatographic separation was performed using the nano-flow Easy nLC 1200 system. Spectrometer 17 was employed to integrate the entirety of the mass spectrometry data, and data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry data were analysed using the library-free DIA (direct DIA) method for database search and protein DIA quantification. The database used was Uniprot-Mus musculus (Mouse)[10090]-88534-20230417.fasta.

Using a standardized extraction method, total DNA from faecal samples was extracted. DNA quantification was per

Mouse hippocampal tissue was homogenized in RIPA protein lysis buffer, and then centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 15 minutes. The BCA assay was used to measure protein concentration in the supernatant. After electrophoresis, the protein was transferred onto a PVDF membrane at 4 °C for one hour. The membrane was washed five times for 5 minutes each with PBST. Blocking was performed with 5% skim milk for 1 hour, followed by five washes with PBST. Primary anti

The level of reduced glutathione (GSH) in mouse hippocampal tissue was measured using a colorimetric assay kit, following the operational procedures provided in the kit’s instruction manual.

SPSS 26.0 was used to analyze all data. An independent sample t-test was used to compare the experimental and control groups when the data had a normal distribution. Multifactorial ANOVA was employed to analyze the interactions between study factors, with post hoc analysis using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) method if interactions were significant. Several time points were compared using repeated measures ANOVA. In this study, P < 0.05 was defined as the threshold for statistical significance. The processing and analysis of image data were performed using ImageJ (1.53a), GraphPad Prism, and 8.0 software.

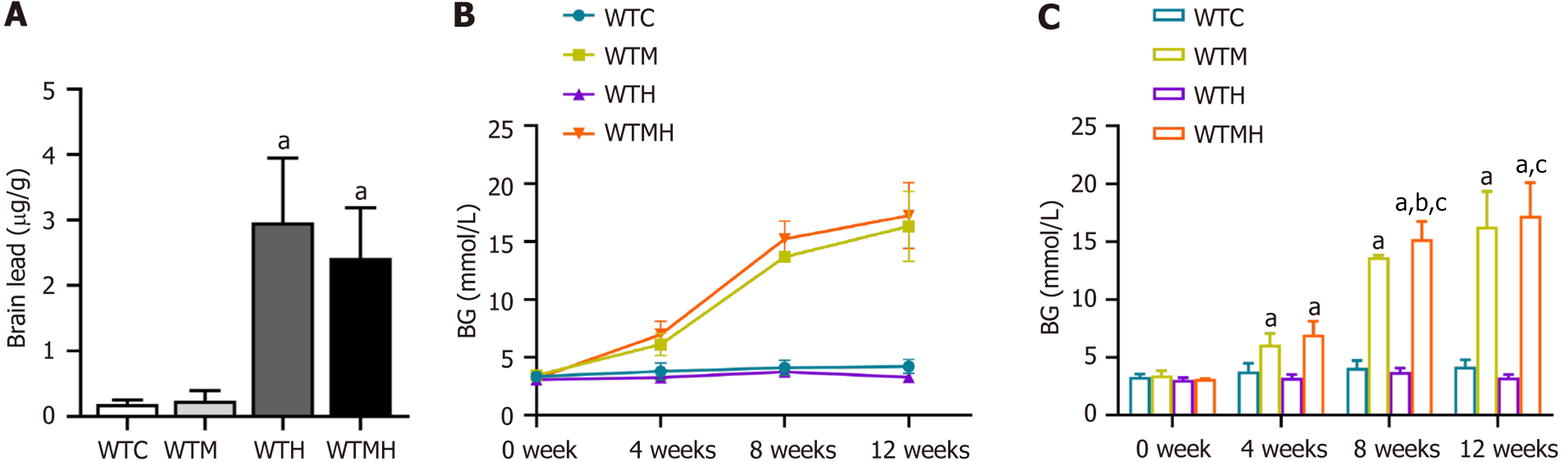

To determine the lead levels in mice after exposure, we measured lead concentrations in hippocampal tissues with ICP-MS. It was shown in independent sample t-tests that lead levels in the brain were significantly elevated in the lead exposed group (P = 0.039) and the diabetic lead exposed group (P = 0.037) compared to the control group. However, there was no interaction effect between diabetes and lead exposure on brain lead levels (F = 0.416, P = 0.528) (Figure 1A).

To determine blood glucose changes during the experiment, multiple comparisons of blood glucose levels at 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks in each group of mice were conducted using the LSD method. Compared to the previous time point in each group, the blood glucose levels in the diabetes group and the diabetes lead-exposure group increased significantly as the experiment progressed (P < 0.05), as illustrated in Figure 1B. We then performed a multifactorial ANOVA on the blood glucose values of different groups at weeks 4, 8, and 12. It was indicated that there was no interaction between diabetes and lead exposure on blood glucose at weeks 4 and 12. However, at week 8 (F = 7.846, P = 0.014), diabetes and lead exposure had a significant interaction on blood glucose levels. At weeks 4, 8, and 12 of the exposure study, the diabetes group had higher blood glucose levels than the lead exposure group, and it was indicated in the LSD analysis that the increase in blood glucose in the diabetes lead-exposure group was statistically significant compared to the diabetes group at week 8 (P = 0.018). These findings suggest that lead exposure alone does not affect blood glucose levels, but it makes blood glucose higher when diabetes already existed (Figure 1C).

To evaluate the effects of lead exposure and diabetes on brain tissue damage in mice, we used immunofluorescence to analyze GFAP levels in astrocytes in the hippocampal region of the mouse brain. The results indicated that, compared to the control group, the average GFAP fluorescence intensity was significantly elevated in the diabetic group, the lead exposure group, and the diabetic lead exposure group (P = 0.014, P = 0.148, P = 0.002). Multivariate analysis revealed a significant interaction between diabetes and lead exposure in influencing GFAP levels in the hippocampal tissue of mice (P < 0.001). The GFAP fluorescence intensity in the diabetic lead exposure group was significantly higher than that in the lead exposure group (P = 0.002) (Figure 2).

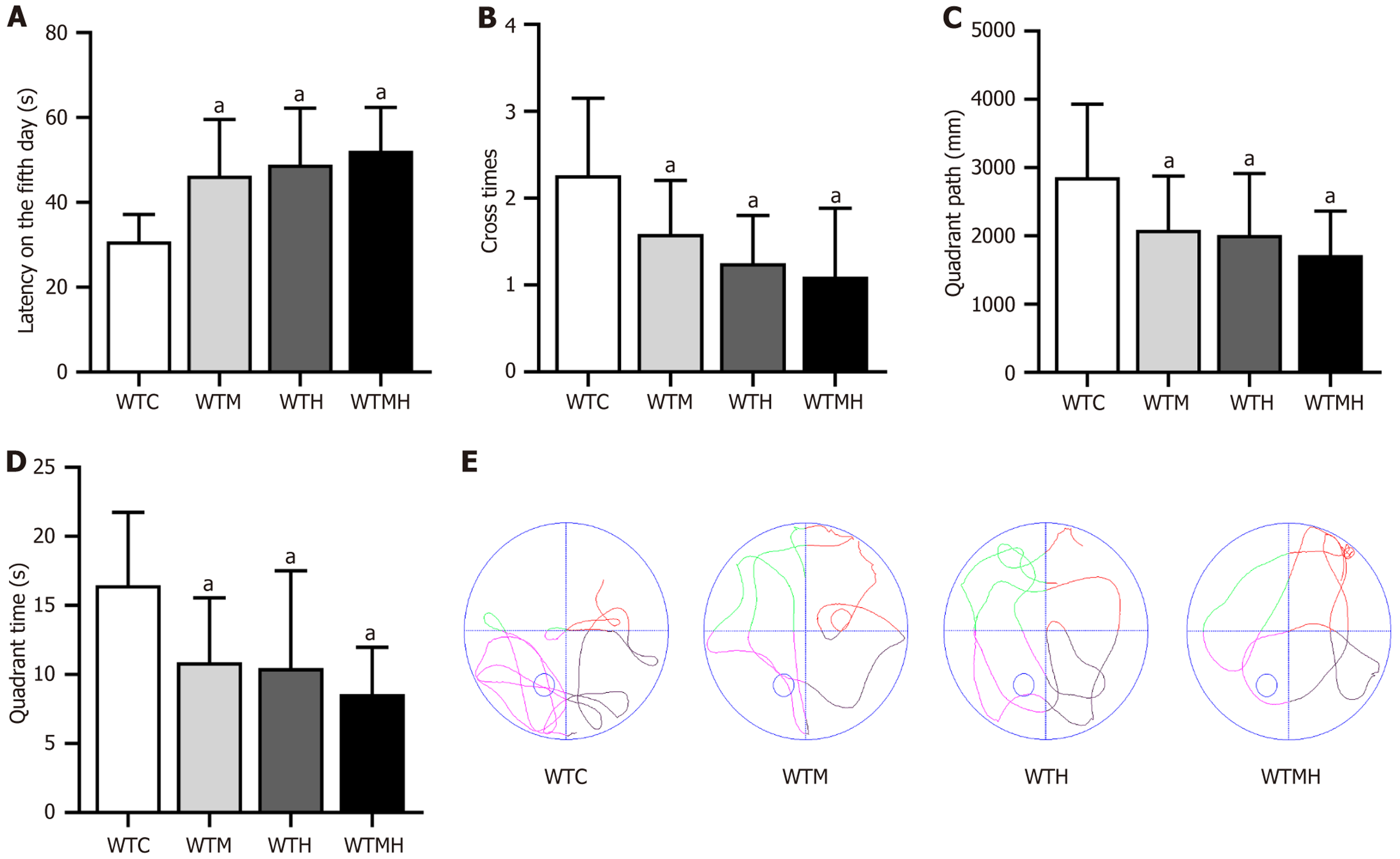

To study the neurological effects of lead exposure and hyperglycemia, we conducted the Morris water maze. In the place navigation test, we performed a t-test analysis on the escape latency of the mice on the 5th day. The escape latency was significantly higher in the diabetes group (P = 0.011), the lead exposure group (P = 0.027), and the diabetes lead exposure group (P = 0.027) than in the control group. It was observed that there was the longest escape latency in the diabetes lead exposure group (Figure 3A). This result indicated that both diabetes and lead exposure may impair neurological function in mice, with the most severe damage observed in mice exposed to lead under diabetic conditions. Additionally, it was shown in a multifactorial ANOVA analysis of the escape latency on the 5th day that there was no interaction between diabetes and lead exposure on escape latency (F = 0.926, P = 0.343).

In the spatial exploration test, independent sample t-tests were performed. Compared to the control group, the diabetic group (P = 0.016, P < 0.001, P = 0.007), lead exposure group (P < 0.001, P = 0.002, P = 0.002), and diabetic lead exposure group (P < 0.001) all showed significant reductions in platform crossing frequency, target quadrant time, and target quadrant swim distance. The diabetic lead exposure group exhibited the most pronounced reduction. It was indicated in multifactorial ANOVA that there was no interaction between diabetes and lead exposure for three evaluation metrics (Figure 3B-E).

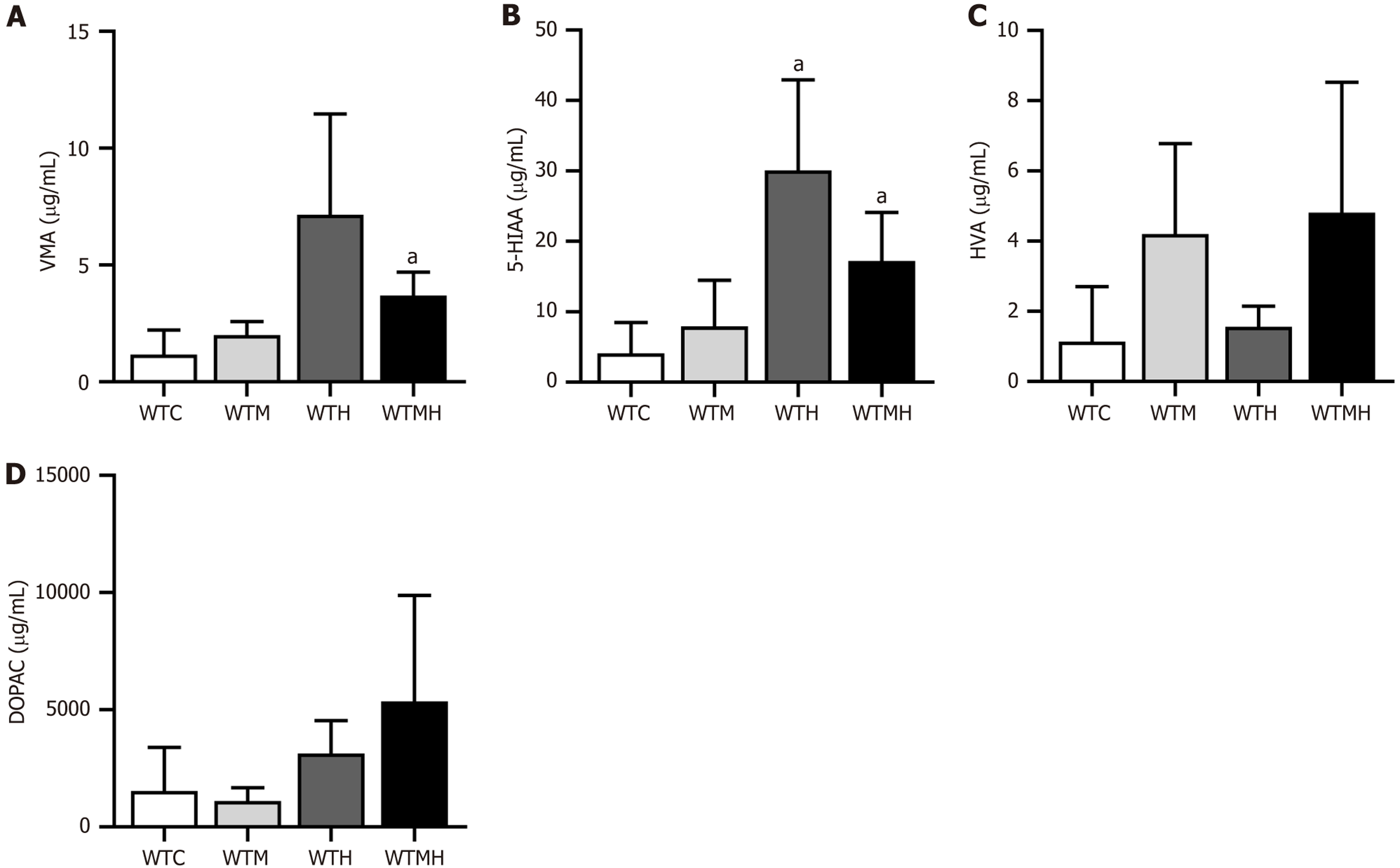

To further confirm the neurotoxic effects of lead and diabetes, we conducted high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of four neurotransmitters in the urine of mice. It was indicated that lead and diabetes had differential effects on various neurotransmitters. Specifically, lead exposure had a more pronounced effect on vanillylmandelic acid (VMA), 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), while diabetes had a greater impact on homovanillic acid (HVA) (Figure 4). It was revealed in t-tests that compared to the control group, the lead-exposed group had significantly higher 5-HIAA levels (P = 0.021), and the diabetes lead-exposed group had significantly higher VMA (P = 0.008) and 5-HIAA levels (P = 0.013). When both high blood sugar and lead exposure were present, changes in HVA and DODA showed an additive effect, whereas VMA and 5-HIAA exhibited a diminishing effect. It was indicated in multi-factor ANOVA results that there was an interaction between diabetes and lead exposure on the levels of VMA (F = 4.971, P = 0.041) and 5-HIAA (F = 4.779, P = 0.046) (Figure 4A and B).

To investigate the mechanisms of neurotoxic effects under lead exposure and hyperglycaemic conditions, we performed proteomic analysis on the hippocampal tissues from mice in different groups. It was indicated that the number of differentially expressed proteins in the WTM was 75 upregulated and 81 downregulated, while in the WTMH, 146 genes were upregulated and 145 were downregulated, compared to the WTC.

It was shown in Gene Ontology biological process enrichment analysis of the top 10 differentially expressed genes that, besides being associated with glucose metabolism, the differential genes in the WTM group are closely related to neuro

In this study, a decrease in gut microbiota richness of mice from the WTM and WTHM groups was shown compared to the control group, as indicated by Chao1 and observed species indices, and a reduction in phylogenetic diversity as measured by Faith’s phylogenetic diversity index. The Simpson diversity index also decreased in the WTHM group, though this difference was not statistically significant. No significant differences were shown in other indices among different groups (Figure 6A). Additionally, it was indicated in Venn diagram that the number of differential microbial species was 1479 in the WTM group and 947 in the WTHM group, compared to 1902 in the control group, as shown in Figure 6B. The experimental treatments might alter the abundance of the gut microbiota, particularly affecting species such as Sutterella, Allobaculum, Lactobacillus, and Prevotella, which are associated with inflammation and metabolic states in the body (Figure 6C).

To explore the correlation between changes in the gut microbiota and brain tissue protein changes, a correlation analysis was conducted between the differentially expressed proteins in the hippocampal tissue and the differentially abundant gut microbiota of mice between the WTH or WTHM and the WT groups. We selected the top 60 differentially expressed proteins and compared them with the differentially abundant microbiota. It was shown that the gut microbiota most strongly correlated with the differentially expressed proteins were Sutterella, Ruminococcus, and Allobaculum between the WTC and WTM groups. And the microbiota most strongly correlated with the differentially expressed proteins included Sutterella, Roseburia, and Flexispira between the WTC and WTMH groups (correlation coefficients ranging from 0.7 to 1). It was found that Sutterella had the highest correlation coefficient with multiple proteins. Therefore, the gut microbiota most closely related to both high glucose levels and lead exposure is Sutterella (Figure 6D and E).

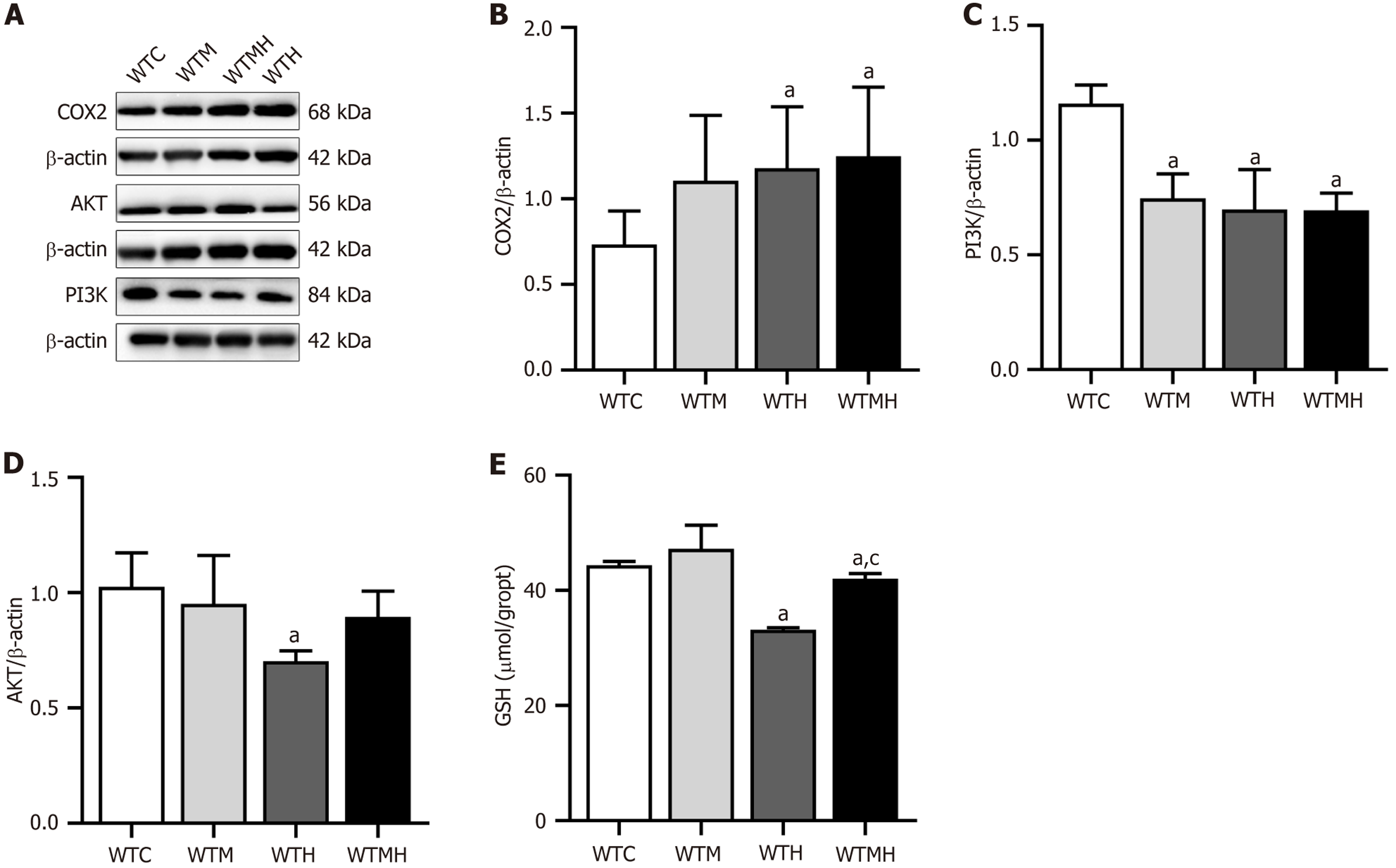

To validate the findings from the mechanism research, Western blot analysis was performed on the hippocampal tissue of mice to assess the expression of the inflammation-related protein COX2 and the key metabolic pathway proteins PI3K and AKT. Compared to the control group, COX2 expression was significantly increased in the lead exposure group (P = 0.041) and the diabetes lead exposure group (P = 0.029). Additionally, PI3K expression levels were significantly reduced in the lead exposure group (P = 0.014), the diabetes group (P = 0.006), and the diabetes lead exposure group (P = 0.002) compared to the control group. It was shown in multi-factorial ANOVA results that there was an interaction effect between diabetes and lead exposure on the expression levels of PI3K (F = 9.330, P = 0.016) (Figure 7A-D).

In order to further confirm the role of inflammation, we measured GSH levels in the hippocampal tissues of mice. Compared to the control group, lead exposure (P < 0.001) and diabetes plus lead exposure (P = 0.022) resulted in lower GSH levels in the brain in t-test analyses. And it was indicated in multi-factorial ANOVA that there was an interaction effect between diabetes and lead exposure on GSH levels (F = 5.931, P = 0.041). In the post-hoc LSD comparison, lead exposure significantly decreased GSH levels, as compared to diabetes plus lead exposure (P = 0.001) (Figure 7E).

This study provided preliminary insights into the neurological damage and gut microbiota relationship in mice with diabetes and lead exposure together. It was revealed that when lead exposure and diabetes were present simultaneously, glucose levels were elevated, and neurological damage was more obvious. The levels of the neurotransmitters DODA and HVA in the diabetes-lead exposure group also increased significantly. Proteomic analysis of brain tissue revealed that the diabetes-lead exposure group exhibited the greatest number of differential proteins, which were primarily associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Meanwhile, gut microbiota analysis showed a decrease in both abundance and diversity in the diabetes-lead exposure group, with key differential microbes linked to inflammatory and metabolic pathways. Sutterella was found to have the strongest correlation with differential brain proteins in lead-diabetes exposure when correlation analysis was conducted between differential gut microbiota and brain tissue proteomics. Finally, it was validated for the omics results using COX2 protein expression, antioxidant GSH levels, and metabolism-related PI3K-AKT protein expression.

Diabetes and lead exposure both can result in neurological damage through oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, apoptosis, and so on[23]. However, the primary driving factors and mechanisms of neurotoxic effects differ. Diabetes primarily induces neurological damage through hyperglycaemia and advanced glycation end products, while lead causes damage through direct neurotoxicity and disruption of cellular functions[24,25]. It was found in our study that diabetes and lead exposure together resulted in higher blood glucose and blood lead levels than each factor present individually. Diabetes can increase vascular permeability, which may be a primary reason for elevated blood lead levels. Additionally, lead has endocrine effects, thereby increasing blood glucose levels. In mice behavioural assessments, it was observed that both high blood glucose and lead exposure significantly shortened the escape latency, while the diabetes-lead exposure model group showed the shortest latency. It was further confirmed by the spatial exploration results, which demon

To further confirm the neurological damage and potential mechanisms when both diabetes and lead exposure were present, HPLC was used to analyse four neurotransmitters in mice, including VMA, 5-HIAA, DOPAC, and HVA. It was found that there was an interaction between diabetes and lead exposure, which affected the levels of VMA and 5-HIAA, while DOPAC and HVA were significantly increased. These four substances are key metabolites of neurotransmitter systems, and changes in their levels can reflect the functional state and extent of neurological damage. VMA is a reflection of sympathetic nerve activity (stress response), and elevated levels of VMA may be associated with stress response, particularly in neurodegenerative diseases[26]. DOPAC changes can reflect the activity of the dopamine system, with elevated DOPAC levels being associated with neuronal damage. HVA levels also represent the overall activity of the dopamine system, and in some neurodegenerative diseases, elevated HVA levels may indicate damage or metabolic abnormalities in dopaminergic neurons[27]. Changes in 5-HIAA levels are related to the metabolism and function of the neurotransmitter serotonin, and in cases of nerve damage and neurodegenerative diseases[28], changes in 5-HIAA levels can serve as biomarkers for monitoring disease progression and treatment outcomes[29]. It was shown that the effects of lead and diabetes on neurotransmitters were not uniform. Lead tended to cause direct damage to various aspects of the nervous system, including the sympathetic neurotransmitter VMA, serotonin 5-HIAA, and the dopamine system DOPAC, whereas diabetes-related neurological damage is more associated with HVA, which represents the overall dopamine system and has a close relationship with neuroinflammation. It was indicated that although the presence of both lead and high blood glucose had a greater impact on neurological function, their mechanisms of action differ. Lead tended to cause short-term and direct damage, while diabetes resulted in long-term, slowly progressing neurological damage through multiple pathways.

In this study, it was also shown that the trend of lead levels in brain tissue was consistent with the changes in VMA and 5-HIAA levels. It was the lead exposure group that had the highest lead content in the brain, as well as the highest levels of VMA and 5-HIAA. It is generally believed that hyperglycemia induces oxidative stress, thereby increasing the permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB)[30]. Transport proteins and metabolic abnormalities could also result in lead accumulation in the brain. However, it was shown in our study that when both lead exposure and diabetes coexisted, the lead levels in brain tissue were actually lower than those in the group with lead exposure alone. This change may involve multiple factors. When lead exposure and diabetes coexisted and resulted in higher blood glucose levels, hyperglycemia could affect the expression and function of metal transport proteins in the BBB, thereby regulating the process of lead entering the brain. Hyperglycemia over a long time could cause structural and functional changes in the BBB. Moreover, it also influences the metabolism and distribution of other important metals such as calcium and iron, which may compete with lead in transport and accumulation. These findings highlight the complexity and variability of neuro

To determine if lead and diabetes together induce changes in brain-associated proteins through gut microbiota dysbiosis, we conducted proteomics analysis on the hippocampal tissue of mice and analysed the gut microbiota from faecal samples collected directly from the colon. It was found that several differential proteins induced by lead and high blood glucose were related to neurodegenerative changes. Differential proteins associated with high blood glucose alone also affected neuronal development, but the addition of lead exposure exacerbated the expression of metabolism-related differential proteins. Gut microbiota analysis revealed that the abundance of the gut microbiota was reduced in the lead-diabetes group. The top 20 differential microbiota, including Sutterella, Allobaculum, Lactobacillus, and Prevotella, were all associated with inflammation and metabolism. Previous studies have identified beneficial bacteria closely related to diabetes, such as Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus, and Akkermansia muciniphila, which improve diabetes primarily by alleviating insulin resistance, restoring gut barrier function, and modulating immune function[31]. Conversely, harmful bacteria associated with diabetes, such as Firmicutes, Bacteroides, and Proteobacteria, can affect insulin sensitivity and worsen diabetes by producing acids or by disrupting the gut barrier[32,33]. When both lead exposure and high blood glucose were present, it was indicated in the correlation analysis of differential brain proteomics and the gut microbiota that Sutterella had the strongest correlation with various differential proteins among the top 20 differential microbiota. Sutterella, a Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria and order Bacteroidales, is commonly found in the human gut. Changes in Sutterella abundance in the gut are usually related to gut inflammation and immune responses[34]. Additionally, lead exposure and high blood glucose may influence the abundance and distribution of Sutterella in the gut microbiota, resulting in enhanced intestinal inflammatory responses and the release of peripheral inflammatory factors, ultimately altering brain proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases.

Finally, the levels of the inflammation-related protein COX2 and the antioxidant GSH in brain tissue were assessed to confirm the impact of lead exposure and diabetes. It was observed that there were elevated COX2 and reduced GSH levels in the lead-diabetes group. And it was indicated that the changes in gut microbiota abundance and diversity, particularly in Sutterella, which was most closely associated with differential brain proteins, indeed influenced neural function through brain inflammation pathways. GSH is one of the primary antioxidants in vivo, and can reduce free radicals and peroxides. Neurodegenerative diseases are associated with a decline in GSH levels, exacerbating oxidative stress and triggering or worsening inflammation, which ultimately causes neuronal damage[35,36]. Both lead-induced oxidative stress and diabetes-related insulin resistance contribute to reduced GSH levels. Moreover, COX-2 is a crucial enzyme activated during inflammation, catalysing the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, which promote inflammatory responses[37]. There is an important role for COX-2 in chronic low-grade inflammation associated with diabetes. An interaction effect between Lead exposure and diabetes on PI3K expression was also found in the brain, which was similar to the KEGG results in the hippocampal proteomics analysis. These findings preliminarily validated that the changes of Sutterella, which were induced by the lead and diabetes, resulted in inflammatory responses and altered brain neural and metabolic proteins, ultimately causing neural dysfunction.

This study has several advantages. First, it was confirmed in animal models that the influences of simultaneous lead exposure and diabetes on blood glucose levels and neural damage were more pronounced than those of lead exposure or hyperglycemia alone. Second, through comprehensive analyses of neurotransmitters, brain proteomics, and the gut microbiota, it was verified that the mechanisms of neural damage due to lead exposure and high glucose levels were not entirely similar. Finally, it was identified in our study that lead and diabetes might enhance inflammatory responses through changes in the abundance of the gut bacterium Sutterella, resulting in alterations in brain proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases. However, this study also has limitations. First, although we identified differences in proteins and microbiota due to diabetes, lead exposure, and their combined effects, further and detailed exploration of these differences is needed. For example, the need for validation in germ-free animal models is necessary, which could confirm the results of the correlation between changes in the gut microbiota and brain injury. Second, while we preliminarily analysed the correlation between the gut microbiota and differential brain proteins, we did not measure related metabolic products in peripheral blood and analyse the correlations among metabolic products, gut bacteria, and brain proteins. Moreover, the incorporation of metabolomic analyses would strengthen causal inferences. Lastly, although we found a common correlation with Sutterella when both lead and diabetes damage neural function in the brain, the inflammatory mechanism was only preliminarily validated, and more work should be conducted via a comprehensive evaluation of Sutterella's specific effects with special animal models such as germ-free mice colonized with Sutterella.

In summary, this study demonstrated the additive neurotoxic effects of concurrent lead exposure and diabetes. Based on proteomic and gut microbiota analyses, it also conducted a preliminary exploration of the mechanisms by which the gut microbiota regulates differential protein expression in the brain and ultimately impacts neurological function. Sutterella was identified as the gut microbe commonly affected by these two factors, with inflammatory responses constituting their shared pathway.

| 1. | Ma RCW. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetic complications in China. Diabetologia. 2018;61:1249-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 5735] [Article Influence: 1433.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 3. | Zilliox LA, Chadrasekaran K, Kwan JY, Russell JW. Diabetes and Cognitive Impairment. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Galiero R, Caturano A, Vetrano E, Beccia D, Brin C, Alfano M, Di Salvo J, Epifani R, Piacevole A, Tagliaferri G, Rocco M, Iadicicco I, Docimo G, Rinaldi L, Sardu C, Salvatore T, Marfella R, Sasso FC. Peripheral Neuropathy in Diabetes Mellitus: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Diagnostic Options. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ehtewish H, Arredouani A, El-Agnaf O. Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Mechanistic Biomarkers of Diabetes Mellitus-Associated Cognitive Decline. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huang X, He Y, Xu H, Shen Y, Pan X, Wu J, Chen K. Association between sociodemographic status and the T2DM-related risks in China: implication for reducing T2DM disease burden. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1297203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:88-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2249] [Cited by in RCA: 3667] [Article Influence: 458.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dimakakou E, Johnston HJ, Streftaris G, Cherrie JW. Exposure to Environmental and Occupational Particulate Air Pollution as a Potential Contributor to Neurodegeneration and Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dimakakou E, Johnston HJ, Streftaris G, Cherrie JW. Is Environmental and Occupational Particulate Air Pollution Exposure Related to Type-2 Diabetes and Dementia? A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the UK Biobank. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li B, Xia M, Zorec R, Parpura V, Verkhratsky A. Astrocytes in heavy metal neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration. Brain Res. 2021;1752:147234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Martins AC, Ferrer B, Tinkov AA, Caito S, Deza-Ponzio R, Skalny AV, Bowman AB, Aschner M. Association between Heavy Metals, Metalloids and Metabolic Syndrome: New Insights and Approaches. Toxics. 2023;11:670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tyrrell JB, Hafida S, Stemmer P, Adhami A, Leff T. Lead (Pb) exposure promotes diabetes in obese rodents. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2017;39:221-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kolachi NF, Kazi TG, Afridi HI, Kazi N, Khan S, Kandhro GA, Shah AQ, Baig JA, Wadhwa SK, Shah F, Jamali MK, Arain MB. Status of toxic metals in biological samples of diabetic mothers and their neonates. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;143:196-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bener A, Obineche E, Gillett M, Pasha MA, Bishawi B. Association between blood levels of lead, blood pressure and risk of diabetes and heart disease in workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2001;74:375-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu W, Feng H, Zheng S, Xu S, Massey IY, Zhang C, Wang X, Yang F. Pb Toxicity on Gut Physiology and Microbiota. Front Physiol. 2021;12:574913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gao B, Chi L, Mahbub R, Bian X, Tu P, Ru H, Lu K. Multi-Omics Reveals that Lead Exposure Disturbs Gut Microbiome Development, Key Metabolites, and Metabolic Pathways. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30:996-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cai J, Sun L, Gonzalez FJ. Gut microbiota-derived bile acids in intestinal immunity, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30:289-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 545] [Article Influence: 136.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Veilleux A, Mayeur S, Bérubé JC, Beaulieu JF, Tremblay E, Hould FS, Bossé Y, Richard D, Levy E. Altered intestinal functions and increased local inflammation in insulin-resistant obese subjects: a gene-expression profile analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen Y, Li Y, Fan Y, Chen S, Chen L, Chen Y, Chen Y. Gut microbiota-driven metabolic alterations reveal gut-brain communication in Alzheimer's disease model mice. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2302310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Brown EM, Clardy J, Xavier RJ. Gut microbiome lipid metabolism and its impact on host physiology. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31:173-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 87.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chang M, Chang KT, Chang F. Just a gut feeling: Faecal microbiota transplant for treatment of depression - A mini-review. J Psychopharmacol. 2024;38:353-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xia Y, Wang C, Zhang X, Li J, Li Z, Zhu J, Zhou Q, Yang J, Chen Q, Meng X. Combined effects of lead and manganese on locomotor activity and microbiota in zebrafish. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023;263:115260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li Q, Zhao Y, Guo H, Li Q, Yan C, Li Y, He S, Wang N, Wang Q. Impaired lipophagy induced-microglial lipid droplets accumulation contributes to the buildup of TREM1 in diabetes-associated cognitive impairment. Autophagy. 2023;19:2639-2656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang J, Su P, Xue C, Wang D, Zhao F, Shen X, Luo W. Lead Disrupts Mitochondrial Morphology and Function through Induction of ER Stress in Model of Neurotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wątroba M, Grabowska AD, Szukiewicz D. Chemokine CX3CL1 (Fractalkine) Signaling and Diabetic Encephalopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:7527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hendrickx JO, De Moudt S, Van Dam D, De Deyn PP, Fransen P, De Meyer GRY. Altered stress hormone levels affect in vivo vascular function in the hAPP23(+/-) overexpressing mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;321:H905-H919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Goto R, Kurihara M, Kameyama M, Komatsu H, Higashino M, Hatano K, Ihara R, Higashihara M, Nishina Y, Matsubara T, Kanemaru K, Saito Y, Murayama S, Iwata A. Correlations between cerebrospinal fluid homovanillic acid and dopamine transporter SPECT in degenerative parkinsonian syndromes. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2023;130:513-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fu R, Jinnah H, Mckay JL, Miller AH, Felger JC, Farber EW, Sharma S, Whicker N, Moore RC, Franklin D, Letendre SL, Anderson AM. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of 5-HIAA and dopamine in people with HIV and depression. J Neurovirol. 2023;29:440-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Juliá-Palacios N, Molina-Anguita C, Sigatulina Bondarenko M, Cortès-Saladelafont E, Aparicio J, Cuadras D, Horvath G, Fons C, Artuch R, García-Cazorla À; Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu Working Group. Monoamine neurotransmitters in early epileptic encephalopathies: New insights into pathophysiology and therapy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64:915-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wątroba M, Grabowska AD, Szukiewicz D. Effects of Diabetes Mellitus-Related Dysglycemia on the Functions of Blood-Brain Barrier and the Risk of Dementia. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:10069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bell KJ, Saad S, Tillett BJ, McGuire HM, Bordbar S, Yap YA, Nguyen LT, Wilkins MR, Corley S, Brodie S, Duong S, Wright CJ, Twigg S, de St Groth BF, Harrison LC, Mackay CR, Gurzov EN, Hamilton-Williams EE, Mariño E. Metabolite-based dietary supplementation in human type 1 diabetes is associated with microbiota and immune modulation. Microbiome. 2022;10:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Qi Q, Zhang H, Jin Z, Wang C, Xia M, Chen B, Lv B, Peres Diaz L, Li X, Feng R, Qiu M, Li Y, Meseguer D, Zheng X, Wang W, Song W, Huang H, Wu H, Chen L, Schneeberger M, Yu X. Hydrogen sulfide produced by the gut microbiota impairs host metabolism via reducing GLP-1 levels in male mice. Nat Metab. 2024;6:1601-1615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Li R, Shokri F, Rincon AL, Rivadeneira F, Medina-Gomez C, Ahmadizar F. Bi-Directional Interactions between Glucose-Lowering Medications and Gut Microbiome in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Genes (Basel). 2023;14:1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jiang D, Goswami R, Dennis M, Heimsath H, Kozlowski PA, Ardeshir A, Van Rompay KKA, De Paris K, Permar SR, Surana NK. Sutterella and its metabolic pathways positively correlate with vaccine-elicited antibody responses in infant rhesus macaques. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1283343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Rochette L, Dogon G, Rigal E, Zeller M, Cottin Y, Vergely C. Lipid Peroxidation and Iron Metabolism: Two Corner Stones in the Homeostasis Control of Ferroptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Aoyama K. Glutathione in the Brain. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chan PC, Liao MT, Hsieh PS. The Dualistic Effect of COX-2-Mediated Signaling in Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |