Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112690

Revised: September 8, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 164 Days and 16.6 Hours

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is characterized by glucose intolerance first identified during pregnancy. Adipokines are adipose-derived hormones regu

To explore the associations between body composition, adipokines, and GDM risk, identifying early predictive markers to enhance prenatal risk assessment.

A retrospective analysis included 1656 singleton pregnant women (276 with GDM, 1380 with normal glucose tolerance) from 2020-2024. Early pregnancy (6-16 weeks) body composition was assessed via bioelectrical impedance analysis. Adipokines (leptin, adiponectin, fatty acid-binding protein 4) and metabolic in

GDM women had higher pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), glucose/insulin, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, lower insulin sensitivity index (all P < 0.05). GDM showed higher fat mass percentage (FMP) (36.23% ± 7.54% vs 33.12% ± 9.87%), fat mass index (FMI) (9.87 ± 3.32 kg/m2vs 8.34 ± 4.11 kg/m2), extracellular-to-intracellular water ratio (ECW/ICW) (0.63 ± 0.03 vs 0.61 ± 0.02), lower lean mass indices (all P < 0.001 except ECW/ICW P = 0.012). GDM had higher leptin (P = 0.014), lower adiponectin (P = 0.021). FMP elevation was independent risk factor (odds ratio = 1.412, P = 0.030). Pre-pregnancy BMI (area under the curve = 0.662), FMP (0.651), FMI (0.650) had better diagnostic value than ECW/ICW (0.606).

Body composition parameters (FMP, FMI) and adipokines (leptin, adiponectin) are closely linked to GDM risk. Integrating these assessments into prenatal care facilitates early risk identification and targeted interventions to improve maternal-fetal outcomes.

Core Tip: This study investigates the interplay between body composition and adipokine levels in pregnant women, aiming to clarify their combined and individual associations with gestational diabetes mellitus risk. It highlights how adipose tissue-derived factors and body composition metrics may serve as potential markers or mechanistic links in gestational diabetes mellitus pathogenesis, offering insights for early risk assessment and intervention.

- Citation: Li L, Mu YC, Wang DW, Du J, Zhang ZJ, Wang FJ. Body composition and adipokines in pregnant women: Associations with gestational diabetes mellitus risk. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 112690

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/112690.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112690

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), characterized by de novo glucose intolerance diagnosed during the second or third trimester, represents a burgeoning public health challenge with global prevalence estimates ranging from 14% to 19.7% in Asian populations[1,2]. This metabolic disorder poses substantial short- and long-term risks to both mother and offspring, including macrosomia, preeclampsia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and increased susceptibility to type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in later life[3].

Traditional risk assessment relying on pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) has limitations, as it fails to distinguish between fat mass, lean mass, and their anatomical distribution[4]. Emerging evidence highlights that normal-weight individuals with elevated body fat percentage (> 30%) or visceral fat area (≥ 80 cm2) phenotypes termed “normal weight obesity” exhibit comparable metabolic dysregulation to obese counterparts, including insulin resistance and pro-inflammatory states[4]. This is particularly relevant in Asian populations, who demonstrate higher adiposity at lower BMIs, underscoring the need for more precise body composition analysis.

Body composition parameters, such as fat mass index (FMI), fat mass percentage (FMP), and extracellular-to-intracellular water ratio (ECW/ICW), have emerged as promising biomarkers[5]. Adipose tissue, beyond its energy-storage role, functions as an endocrine organ secreting adipokines leptin, adiponectin, and fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4) which modulate insulin sensitivity and systemic inflammation[6]. Dysregulation of these mediators, particularly reduced adiponectin and elevated leptin, characterizes GDM pathophysiology, linking excess adiposity to impaired glucose homeostasis[7].

Despite advances, the intricate interplay between specific body composition metrics, adipokine profiles, and GDM development remains incompletely elucidated. Particularly, the combined predictive value of early body composition assessment and mid-gestation adipokine measurement for GDM risk requires further investigation in Chinese populations[5,8]. Retrospective investigations leveraging bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) offer opportunities to dissect these relationships, potentially identifying early predictive markers. Such insights could facilitate targeted interventions to mitigate GDM risk, optimizing maternal and fetal outcomes through personalized lifestyle modifications and clinical monitoring. This study synthesizes current evidence on body composition, adipokine dynamics, and their collective role in GDM pathogenesis, with a focus on identifying clinically applicable markers for improved risk stratification and early intervention.

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anyang Maternal and Child Health Hospital (approval No. AF/04-07.0/10.0). The study included singleton pregnant women who attended routine prenatal care at the Obstetrics Department of Anyang Maternal and Child Health Hospital and Children’s Hospital between January 2020 and December 2024. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Age 18-40 years; (2) Pre-pregnancy BMI 18.5-24.0 kg/m2; (3) Singleton pregnancy; (4) Complete body composition assessment during early pregnancy (6-16 weeks); (5) Completion of a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) at 24-28 gestational weeks; and (6) Availability of complete clinical and anthropometric data. Women were excluded if they had pre-existing diabetes or other metabolic diseases (e.g., renal or autoimmune disorders), multiple gestations, or incomplete medical records. A total of 1656 women were enrolled, with 276 diagnosed with GDM (GDM group) and 1380 with normal glucose tolerance (NGT group).

GDM was diagnosed using the 75-g OGTT between 24-28 weeks: After an 8-hour fast, participants consumed 300 mL of a 75-g anhydrous glucose solution within 5 minutes. Venous blood samples were collected at fasting, 1 hour, and 2 hours post-glucose ingestion (preserved with sodium fluoride) to measure plasma glucose via the glucose oxidase method. GDM was confirmed if any glucose level met or exceeded the thresholds: Fasting ≥ 5.1 mmol/L, 1-hour ≥ 10.0 mmol/L, or 2-hour ≥ 8.5 mmol/L.

Body composition was assessed during early pregnancy (6-16 weeks) using the multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analyzer InBody770 (Biospace, Seoul, Korea). Participants were instructed to fast for at least 3 hours, avoid strenuous exercise and alcohol for 24 hours, and empty their bladder before measurement. With bare feet and light clothing, participants stood on the device’s foot electrodes and held hand electrodes with arms slightly abducted. The mea

At 24-28 weeks, 5 mL of venous blood was collected during OGTT: Plasma glucose was measured immediately using the glucose oxidase method; Remaining serum was stored at -80 °C for adipokine assays: Adiponectin, FABP4, leptin, and fasting insulin (FINS) were quantified via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using commercial kits (Wuhan Gilead Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), with intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation < 10%.

Insulin resistance and sensitivity indices were calculated as: Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) = [fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) × FINS (mU/L)]/22.5; Insulin sensitivity index (ISI) = 20 × FINS (mU/L)/[fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) - 3.5].

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, with group comparisons via independent-samples t-test. Non-normally distributed variables are expressed as median (P25, P75) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were analyzed with the χ² test. Spearman’s rank correlation assessed relationships between body composition indices, adipokines, and glucose parameters. Logistic regression identified independent risk factors for GDM. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of predictors, with the area under the curve (AUC) compared using DeLong’s test. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 1656 pregnant women were enrolled, with 276 in the GDM group and 1380 in the NGT group. General data comparison results are presented in Table 1. Age, height, and second-trimester weight gain showed no significant between-group differences (P > 0.05). The GDM group had a higher pre-pregnancy BMI, fasting plasma glucose, 1-hour and 2-hour post-OGTT glucose, FINS, HOMA-IR, and a lower ISI compared to the NGT group (all P < 0.05). Parity distribution did not differ significantly (P > 0.05).

| Variables | GDM group (n = 276) | NGT group (n = 1380) | Test statistic | P value |

| Age (years) | 32.5 ± 5.4 | 31.8 ± 5.1 | t = 1.82 | 0.069 |

| Height (m) | 160.8 ± 6.2 | 161.1 ± 5.5 | t = -0.75 | 0.453 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 23.6 ± 3.9 | 22.3 ± 4.8 | t = 4.85 | < 0.001 |

| Second-trimester weight gain (kg), median (P25, P75) | 8.0 (5.2, 10.3) | 7.6 (4.8, 9.9) | Z = 1.21 | 0.226 |

| Parity | χ2 = 3.12 | 0.210 | ||

| 0 | 102 (36.9) | 558 (40.5) | ||

| 1 | 155 (56.2) | 690 (50.0) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 19 (6.9) | 132 (9.5) | ||

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | t = 12.35 | < 0.001 |

| 1-hour post-OGTT glucose (mmol/L) | 9.7 ± 1.4 | 7.4 ± 1.3 | t = 20.12 | < 0.001 |

| 2-hour post-OGTT glucose (mmol/L) | 8.1 ± 1.4 | 6.4 ± 1.0 | t = 15.87 | < 0.001 |

| FINS (mU/L) | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | t = 6.51 | < 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | t = 22.45 | < 0.001 |

| ISI | 0.0055 ± 0.003 | 0.0011 ± 0.0004 | t = 25.67 | < 0.001 |

A total of 1656 pregnant women were enrolled, with 276 in the GDM group and 1380 in the NGT group. The comparison of body composition components between the two groups is shown in Table 2. For FMP, FFMP, MP, PP, M/F, and FMI, there were significant differences between the GDM group and the NGT group (all P < 0.05). The ECW/ICW also showed a significant difference (P = 0.012), while basal metabolism had no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.135).

| Body composition indicator | GDM group (n = 276) | NGT group (n = 1380) | Test statistic | P value |

| FMP (%) | 36.23 ± 7.54 | 33.12 ± 9.87 | t = 5.23 | < 0.001 |

| FFMP (%) | 60.12 ± 7.23 | 63.45 ± 9.56 | t = -4.89 | < 0.001 |

| MP (%) | 56.34 ± 6.45 | 59.23 ± 9.12 | t = -4.56 | < 0.001 |

| PP (%) | 11.54 ± 1.65 | 12.56 ± 2.43 | t = -5.12 | < 0.001 |

| ECW/ICW | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | t = 4.21 | 0.012 |

| M/F | 1.55 ± 0.49 | 1.80 ± 0.90 | t = -4.32 | < 0.001 |

| FMI (kg/m²) | 9.87 ± 3.32 | 8.34 ± 4.11 | t = 4.67 | < 0.001 |

| BM (kcal) | 1587.34 ± 93.21 | 1565.43 ± 142.34 | t = 1.43 | 0.135 |

A total of 1656 pregnant women were enrolled, with 276 in the GDM group and 1380 in the NGT group. The comparison of adipokine levels between the two groups is presented in Table 3. Leptin and adiponectin levels showed significant differences between the GDM and NGT groups (P = 0.014) and (P = 0.021), respectively. FABP4 levels had no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.872).

| Adipokine | GDM group (n = 276) | NGT group (n = 1380) | Test statistic | P value |

| Leptin (pg/mL), median (P25, P75) | 212.34 (45.56, 620.12) | 130.23 (35.45, 860.34) | Z = 2.43 | 0.014 |

| FABP4 (ng/mL), median (P25, P75) | 1.20 (0.03, 1.25) | 1.15 (0.22, 1.52) | Z = 0.16 | 0.872 |

| Adiponectin (ng/mL), median (P25, P75) | 11.34 (7.22, 12.45) | 12.32 (9.11, 13.33) | Z = -2.32 | 0.021 |

We performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to identify risk factors for GDM among 1656 pregnant women (276 in the GDM group and 1380 in the NGT group).

Univariate logistic regression analysis: Univariate logistic regression results are presented in Table 4. Pre-pregnancy BMI, FMP, ECW/ICW, FMI, and M/F were associated with GDM risk (all P < 0.05). FFMP, MP, PP, leptin, FABP4, and adiponectin also showed associations with GDM in the univariate analysis (P < 0.05) for some indicators, P > 0.05 for others as shown.

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 0.145 | 0.035 | 17.234 | < 0.001 | 1.452 (1.082-1.233) |

| FMP | 0.092 | 0.025 | 13.890 | < 0.001 | 1.093 (1.041-1.142) |

| FFMP | -0.095 | 0.026 | 13.567 | < 0.001 | 0.913 (0.861-0.963) |

| MP | -0.102 | 0.028 | 12.987 | < 0.001 | 0.903 (0.851-0.953) |

| PP | -0.378 | 0.102 | 13.654 | < 0.001 | 0.685 (0.551-0.831) |

| ECW/ICW | 0.385 | 0.112 | 12.123 | 0.001 | 1.462 (1.181-1.812) |

| M/F | -0.745 | 0.245 | 9.345 | 0.002 | 0.474 (0.291-0.782) |

| FMI | 0.195 | 0.049 | 15.890 | < 0.001 | 1.215 (1.101-1.342) |

| Leptin | 0.065 | 0.036 | 0.987 | 0.065 | 0.943 (0.531-1.142) |

| FABP4 | -0.085 | 0.170 | 0.245 | 0.620 | 0.918 (0.661-1.283) |

| Adiponectin | -0.032 | 0.026 | 1.234 | 0.265 | 0.972 (0.921-1.034) |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis: Multivariate logistic regression analysis was then conducted, and the results are shown in Table 5. After adjustment, only FMP elevation remained a statistically significant predictor of GDM [odds ratio (OR) = 1.412, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.022-1.932; P = 0.030]. Other factors included in the model, namely pre-pregnancy BMI (OR = 1.067, 95%CI: 0.932-1.213; P = 0.315), ECW/ICW elevation (OR = 1.094, 95%CI: 0.680-1.760; P = 0.720), and FMI elevation (OR = 0.985, 95%CI: 0.881-1.094; P = 0.800), did not show a significant association with GDM risk.

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 0.065 | 0.062 | 1.123 | 0.315 | 1.067 (0.932-1.213) |

| ECW/ICW elevation | 0.090 | 0.245 | 0.135 | 0.720 | 1.094 (0.681-1.762) |

| FMP elevation | 0.390 | 0.150 | 4.567 | 0.030 | 1.412 (1.022-1.932) |

| FMI elevation | -0.015 | 0.058 | 0.065 | 0.800 | 0.985 (0.881-1.094) |

In the univariate analysis, multiple body composition and adipokine related factors were associated with GDM. However, after multivariate adjustment, only FMP elevation retained its independent predictive value for GDM.

Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to explore relationships among insulin resistance indices (HOMA-IR, ISI), body composition parameters, and adipokines (leptin, adiponectin, FABP4) in 1656 pregnant women (276 in the GDM group and 1380 in the NGT group). Results are presented in Table 6.

| Body composition indicator | HOMA-IR (GDM/NGT) | ISI (GDM/NGT) | Leptin (GDM/NGT) | Adiponectin (GDM/NGT) | FABP4 (GDM/NGT) |

| FMP | 0.185/0.152a | -0.201/-0.225a | 0.140/-0.188 | -0.100/-0.110 | 0.005/-0.185a |

| FFMP | -0.212/-0.135a | 0.198/0.215a | -0.055/-0.065 | 0.120/0.095 | -0.010/0.182a |

| MP | -0.210/-0.142a | 0.195/0.212a | -0.060/-0.070 | 0.115/0.098 | -0.012/0.190a |

| PP | -0.225a/-0.140a | 0.215a/0.210a | -0.060/-0.070 | 0.115/0.098 | -0.012/0.190a |

| ECW/ICW | 0.098/0.212a | -0.130/-0.170a | -0.048/-0.105 | -0.145/-0.142a | 0.052/-0.200a |

| M/F | -0.208/-0.145a | 0.192/0.220a | 0.135/0.210 | 0.095/0.215 | -0.002/0.198a |

| FMI | 0.220a/0.148a | -0.222a/-0.228a | 0.155/-0.192 | -0.125/-0.108 | 0.006/-0.196a |

Positive and negative correlations were observed between body composition indicators (FMP, FFMP, MP, PP, ECW/ICW, M/F, FMI) and HOMA-IR, ISI, as well as adipokines. Specific correlation coefficients and significance levels are shown in the table, with P < 0.05 indicating significant correlations for relevant pairs.

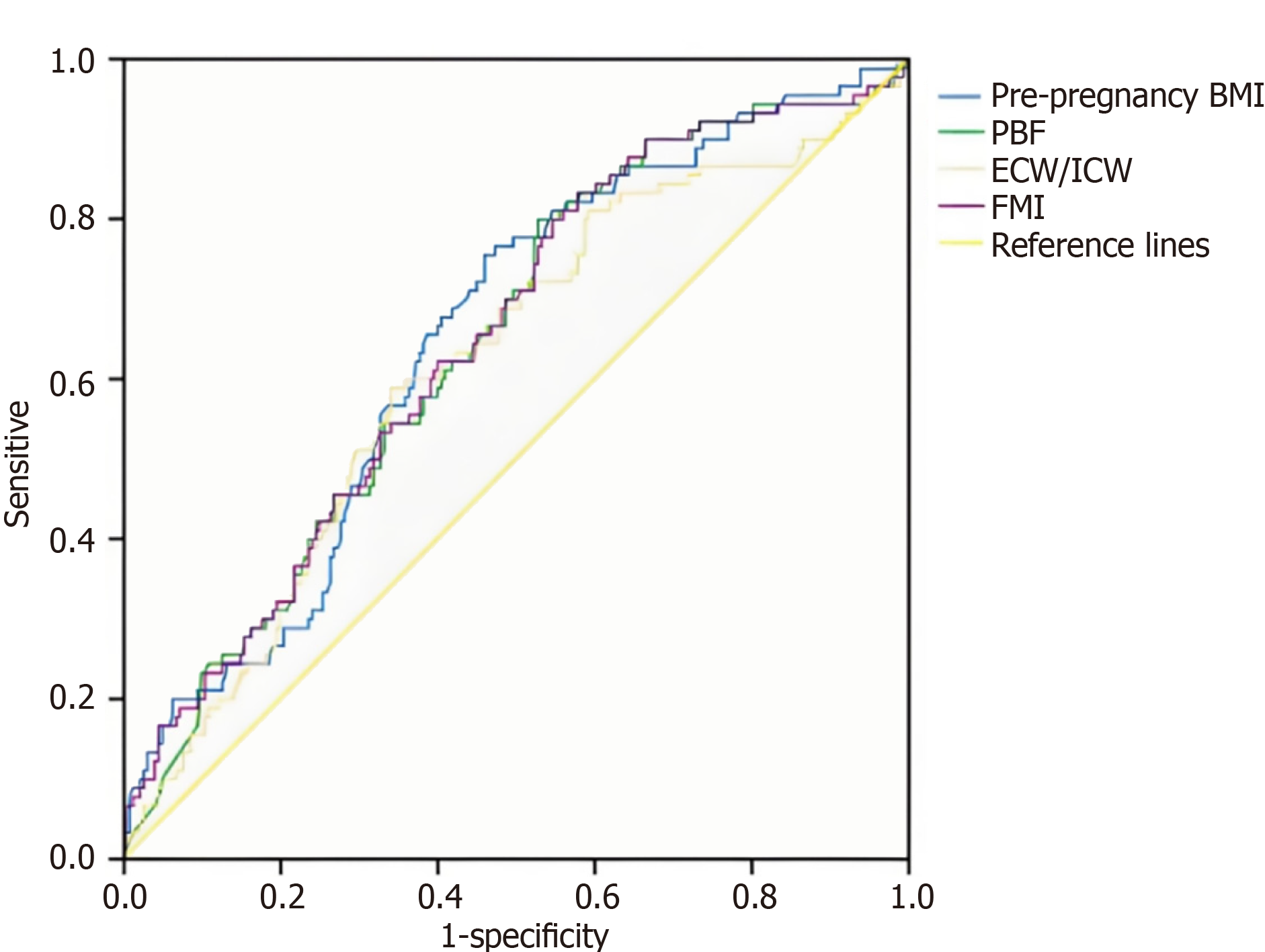

ROC curve analysis was performed on data from 1656 pregnant women to assess the diagnostic value of indicators for GDM. As shown in the ROC curves, pre-pregnancy BMI (AUC = 0.662), FMP (AUC = 0.651), ECW/ICW (AUC = 0.606), and FMI (AUC = 0.650) had similar diagnostic values for GDM. There was no statistically significant difference among pre-pregnancy BMI, FMP and FMI (P = 0.087). However, their diagnostic performance was superior to that of ECW/ICW (P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

The findings of this retrospective study, encompassing 1656 pregnant women, illuminate the intricate associations between body composition parameters and GDM risk. In early pregnancy, distinct alterations in body composition emerged in the GDM group relative to those with NGT. Higher FMP, FMI, and ECW/ICW, alongside lower FFMP, MP, PP, and M/F, characterized the GDM cohort. These deviations align with the pathophysiological underpinnings of GDM, where insulin resistance and metabolic dysregulation disrupt normal body composition homeostasis[9,10]. Biochemical markers further corroborated these trends: Elevated fasting plasma glucose, 1-hour and 2-hour post-OGTT glucose, FINS, and HOMA-IR, coupled with reduced ISI, underscored the metabolic burden in GDM[10,11]. Such metabolic perturbations are not isolated events but are intricately linked to body composition shifts. For instance, higher FMP reflects increased adipose tissue mass, which, in pregnancy, can exacerbate insulin resistance through heightened adipokine secretion (e.g., leptin) and pro-inflammatory cytokine release. The observed lower FFMP and MP in GDM also hold clinical relevance: Lean mass, particularly skeletal muscle, plays a pivotal role in glucose disposal. A diminished muscle mass may compromise glucose uptake and utilization, perpetuating insulin resistance and elevating GDM risk[12,13].

Adipokines, as key mediators of adipose tissue derived signaling, exhibited differential expression in GDM and NGT groups. Leptin was significantly elevated in GDM in bivariate analysis but was not an independent predictor in univariate regression, consistent with its role as an adiposity marker and suggesting its association with GDM may be mediated by other body composition factors. Leptin resistance, often observed in obesity and pregnancy, may contribute to impaired glucose metabolism by desensitizing hypothalamic centers to satiety signals and disrupting insulin signaling pathways in peripheral tissues. Conversely, adiponectin, another adipokine, showed reduced levels in GDM, though the exact mechanistic implications warrant further exploration[14]. Adiponectin has been implicated in adipocyte differentiation, inflammation, and insulin sensitivity; its downregulation may reflect a compensatory response to metabolic stress or a primary dysregulation in GDM pathophysiology[15,16]. The discrepancy between bivariate and univariate analyses for both adipokines suggests that their relationships with GDM may not be direct, but are likely mediated through body composition parameters, supporting the need for future formal mediation analyses to explicitly test whether adipokines act as intermediaries in the pathway toward GDM development. The absence of a significant difference in FABP4 levels between groups (P = 0.872), despite its known role in metabolism, may be attributed to pregnancy-specific hormonal regulation (e.g., high progesterone and estrogen levels) around the 24-28 weeks period when measurements were taken, potentially obscuring subtle inter-group differences[17]. Furthermore, the generally weak correlations observed between adipokines and body composition (e.g., leptin vs FMP: r = 0.140 in GDM) support the concept that adipokine dysregulation may represent an important, yet secondary, downstream consequence of underlying adiposity rather than an independent driver of GDM pathogenesis. Overall, adipokine profiling in our study highlights the multifaceted nature of metabolic dysregulation in GDM, where leptin, Adiponectin, and potentially others, act as nodal points in the interplay between body composition and glucose homeostasis.

In the univariate model, pre-pregnancy BMI, FMP, ECW/ICW, FMI, FFMP, MP, PP, M/F, leptin, and adiponectin emerged as significant predictors. However, multivariate analysis, which accounts for confounding variables, refined this list: Only FMP elevation retained its significance as an independent risk factor, while pre-pregnancy BMI and ECW/ICW elevation did not remain significant in the final model. This underscores the importance of adjusting for potential confounders (e.g., age, parity) to identify truly independent predictors. The persistence of FMP as a key predictor is particularly noteworthy. Adipose tissue, beyond its role as an energy reservoir, is a dynamic endocrine organ. In pregnancy, excessive fat accumulation (high FMP) can disrupt the delicate balance of adipokine secretion, immune cell infiltration, and nutrient sensing, creating a pro-inflammatory, insulin resistant microenvironment[18,19]. Pre-pregnancy BMI, as a composite measure of adiposity, also retained its predictive power, aligning with established literature on obesity as a major GDM risk factor. ECW/ICW elevation, reflecting altered fluid distribution, may signify increased interstitial fluid volume and endothelial dysfunction, both of which can impede insulin delivery to target tissues and exacerbate glucose intolerance[20].

Spearman correlation analysis unveiled intricate relationships between insulin resistance indices (HOMA-IR, ISI), body composition, and adipokines. HOMA-IR positively correlated with FMP, ECW/ICW, FMI, and leptin, while inversely correlating with FFMP, MP, PP, M/F, and adiponectin. These correlations reflect the integrated nature of metabolic health: Increased adipose mass (FMP, FMI) and altered fluid dynamics (ECW/ICW) promote insulin resistance, which, in turn, is associated with dysregulated adipokine secretion (elevated leptin, reduced adiponectin). The inverse relationship between HOMA-IR and lean mass parameters (FFMP, MP, PP, M/F) further emphasizes the protective role of skeletal muscle and protein content in glucose metabolism. Such correlations also have clinical implications for GDM screening and management. Monitoring body composition parameters (e.g., FMP, MP) and adipokines (e.g., leptin, adiponectin) in early pregnancy could facilitate the identification of women at high risk of GDM, enabling timely intervention. Lifestyle modifications, including targeted dietary adjustments to optimize protein intake and physical activity to preserve or enhance lean mass, may mitigate GDM risk by improving insulin sensitivity and metabolic flexibility[21,22].

ROC curve analysis evaluated the diagnostic performance of body composition parameters for GDM. Pre-pregnancy BMI, FMP, ECW/ICW, and FMI exhibited moderate diagnostic value, with AUC ranging from 0.606 (ECW/ICW) to 0.662 (pre-pregnancy BMI). While these AUC values are lower than those of traditional glucose-based tests (e.g., OGTT), they complement existing diagnostic tools by providing insights into the metabolic and compositional underpinnings of GDM. Notably, pre-pregnancy BMI, FMP, and FMI showed comparable diagnostic performance, with no statistically significant differences among them. This suggests that these parameters capture overlapping aspects of adiposity and metabolic risk. In contrast, ECW/ICW, despite its significance in regression models, exhibited a lower AUC, indicating that while it contributes to GDM risk, it may be less specific as a standalone diagnostic marker. Clinically, integrating body composition-based insights with traditional glucose testing could enhance risk stratification. For instance, women exhibiting both high pre-pregnancy BMI (e.g., ≥ 24 kg/m2) and elevated FMP in early pregnancy may represent a high-risk subgroup that could benefit from earlier OGTT screening (e.g., at 20-22 weeks gestation) or intensified lifestyle counseling prior to the standard diagnostic window. Future research should aim to establish specific cut-off values for FMP (e.g., > 35%) and investigate its combined use with adipokine levels (e.g., leptin) to develop integrated risk prediction models that could improve stratification beyond traditional factors.

While this study provides valuable insights into the associations between body composition, adipokines, and GDM, several limitations merit consideration. First, the retrospective design may introduce selection bias, as data were collected from a single center cohort. Multicenter, prospective studies would strengthen the generalizability of findings. Second, body composition was assessed via BIA, which, while convenient, has inherent limitations in accurately quantifying body fat and lean mass compared to gold standard methods [e.g., dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)]. Specifically, BIA measurements are influenced by hydration status a particular limitation in pregnancy[23,24]. While potential measurement error exists, population-based studies have demonstrated strong correlations between BIA-derived and DXA-derived measures of body fat in both general and pregnant populations[25,26]. The strong, consistent, and biologically plausible associations we observed across multiple adiposity metrics suggest these findings reflect true biological relationships. Nevertheless, future validation studies with DXA are warranted to confirm the accuracy of BIA-derived parameters in pregnant populations. Third, the observed body composition-GDM associations may be influenced by unmeasured confounders such as physical activity, diet, family history, and weight gain patterns, which affect both adiposity and metabolic risk. Their omission constitutes a key limitation of our retrospective design. Fourth, the study focused on a relatively narrow range of body composition and adipokine markers. Emerging biomarkers, such as resistin, visfatin, and novel adipocyte derived exosomal microRNAs, warrant investigation to further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of GDM. Fifth, the timing of the measurements presents a constraint due to the retrospective design of our study. Body composition was assessed in early pregnancy, while adipokines were measured during mid-gestation at the time of the clinically scheduled OGTT. This non-concurrent measurement limits our ability to directly link the maternal physical state to the biochemical milieu at the same time point, given the rapid physiological changes occurring throughout pregnancy. Sixth, the timing of body composition assessment (early pregnancy) limits our understanding of dynamic changes throughout gestation. Longitudinal studies tracking body composition from preconception to postpartum could provide a more comprehensive view of metabolic adaptations and their impact on GDM risk. Seventh, our focus on early pregnancy body composition does not capture dynamic gestational changes in fat and lean mass. Excessive mid-pregnancy fat gain may influence insulin resistance more strongly than baseline values. Although longitudinal data were unavailable here, future studies with serial body composition measurements are needed to clarify how these changes affect GDM risk.

Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the growing body of literature on GDM pathophysiology by emphasizing the critical role of body composition and adipokines. The findings support the integration of body composition assessment into prenatal care: Routine measurement of FMP, MP, and adipokines could enhance GDM risk identification, enabling personalized interventions to optimize metabolic health. Future research should explore the efficacy of lifestyle interventions in reducing GDM incidence among high risk women.

In conclusion, this study underscores the complex interplay between body composition, adipokines, and GDM risk. Alterations in fat and lean mass, coupled with dysregulated adipokine expression, create a metabolic milieu conducive to insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. By unraveling these relationships, we pave the way for improved GDM screening, prevention, and management strategies, ultimately aiming to enhance maternal and fetal health outcomes. Looking forward, our findings highlight the need for future research to validate early-pregnancy body composition and adipokine biomarkers in multi-center cohorts, elucidate their mechanistic links to insulin resistance, and develop personalized interventions targeting pre-pregnancy metabolic health to reduce GDM risk. These efforts may ultimately enable more precise prevention strategies and improve maternal and neonatal outcomes.

| 1. | Li LJ, Huang L, Tobias DK, Zhang C. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Among Asians - A Systematic Review From a Population Health Perspective. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:840331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee KW, Ching SM, Ramachandran V, Yee A, Hoo FK, Chia YC, Wan Sulaiman WA, Suppiah S, Mohamed MH, Veettil SK. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Choudhury AA, Devi Rajeswari V. Gestational diabetes mellitus - A metabolic and reproductive disorder. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;143:112183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li Y, Zhao B, Tian Y, Li Y, Li X, Guo H, Xiong L, Yuan J. Association between body composition in early pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1565986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang Y, Luo BR. The association of body composition with the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in Chinese pregnant women: A case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang X, Zhang S, Li Z. Adipokines in glucose and lipid metabolism. Adipocyte. 2023;12:2202976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Plows JF, Stanley JL, Baker PN, Reynolds CM, Vickers MH. The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 1134] [Article Influence: 141.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (19)] |

| 8. | Görkem Ü, Küçükler FK, Toğrul C, Güngör T. Are adipokines associated with gestational diabetes mellitus? J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2016;17:186-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brito Nunes C, Borges MC, Freathy RM, Lawlor DA, Qvigstad E, Evans DM, Moen GH. Understanding the Genetic Landscape of Gestational Diabetes: Insights into the Causes and Consequences of Elevated Glucose Levels in Pregnancy. Metabolites. 2024;14:508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 10. | Mittal R, Prasad K, Lemos JRN, Arevalo G, Hirani K. Unveiling Gestational Diabetes: An Overview of Pathophysiology and Management. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:2320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Singh B, Saxena A. Surrogate markers of insulin resistance: A review. World J Diabetes. 2010;1:36-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 12. | Merz KE, Thurmond DC. Role of Skeletal Muscle in Insulin Resistance and Glucose Uptake. Compr Physiol. 2020;10:785-809. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Abell SK, De Courten B, Boyle JA, Teede HJ. Inflammatory and Other Biomarkers: Role in Pathophysiology and Prediction of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:13442-13473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li X, Yu H, Tian R, Wang X, Xing T, Xu C, Li T, Du X, Cui Q, Yu B, Cao Y, Yin Z. FABP4 as a Mediator of Lipid Metabolism and Pregnant Uterine Dysfunction in Obesity. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12:e2501077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mallardo M, Ferraro S, Daniele A, Nigro E. GDM-complicated pregnancies: focus on adipokines. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48:8171-8180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moyce Gruber BL, Dolinsky VW. The Role of Adiponectin during Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes. Life (Basel). 2023;13:301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wierzchowska-Opoka M, Domańska A, Masiarz A, Olbrot N, Oleszczuk A. Metabolic Roles of Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4 (FABP4) in Fetal and Maternal Health and Maintenance of Pregnancy in Women with Obesity: A Review. Med Sci Monit. 2025;31:e947679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Trivett C, Lees ZJ, Freeman DJ. Adipose tissue function in healthy pregnancy, gestational diabetes mellitus and pre-eclampsia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:1745-1756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jung UJ, Choi MS. Obesity and its metabolic complications: the role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:6184-6223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1040] [Cited by in RCA: 1358] [Article Influence: 113.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nakajima H, Hashimoto Y, Kaji A, Sakai R, Takahashi F, Yoshimura Y, Bamba R, Okamura T, Kitagawa N, Majima S, Senmaru T, Okada H, Nakanishi N, Ushigome E, Asano M, Hamaguchi M, Yamazaki M, Fukui M. Impact of extracellular-to-intracellular fluid volume ratio on albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort study. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12:1202-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zakaria H, Abusanana S, Mussa BM, Al Dhaheri AS, Stojanovska L, Mohamad MN, Saleh ST, Ali HI, Cheikh Ismail L. The Role of Lifestyle Interventions in the Prevention and Treatment of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, Chasan-Taber L, Albright AL, Braun B; American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:e147-e167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 869] [Cited by in RCA: 1001] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Moltchanova E, Eriksson JG. Longitudinal changes in maternal and neonatal anthropometrics: a case study of the Helsinki Birth Cohort, 1934-1944. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2015;6:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Obuchowska A, Standyło A, Kimber-Trojnar Ż, Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B. The Possibility of Using Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis in Pregnant and Postpartum Women. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11:1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ge J, Li R, Yuan P, Che B, Bu X, Shao H, Xu T, Ju Z, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Zhong C. Serum tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and risk of cognitive impairment after acute ischaemic stroke. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:7470-7478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ellegård L, Bertz F, Winkvist A, Bosaeus I, Brekke HK. Body composition in overweight and obese women postpartum: bioimpedance methods validated by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and doubly labeled water. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1181-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/