Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112621

Revised: September 13, 2025

Accepted: November 28, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 166 Days and 18 Hours

The stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) reflects patients’ acute hyperglycemia status, and the time in range (TIR) captures glucose control dynamics during their intensive care unit (ICU) stays.

To investigate the independent and combined associations of SHR and TIR with 28-day mortality among surgical ICU patients.

In total, 706 adult patients with available glucose data were included. SHR was calculated as the ratio of admission glucose levels to glycosylated hemoglobin-derived estimated average glucose. TIR was calculated as percentages of glucose readings within the 3.9-10.0 mmol/L range during the ICU stay. SHR and TIR were divided into quartiles, and patients were allocated to four groups according to combinations of high/low values. The associations of the SHR, TIR, and both combined with mortality were assessed using logistic regression.

Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that patients in the highest SHR quartile had a significantly increased risk of 28-day mortality compared with the reference quartile [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 2.24; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.06-4.71; P = 0.033]. In contrast, higher TIR were associated with a reduced risk of 28-day mortality. Compared with the lowest TIR quartile (Q1), adjusted ORs in Q2, Q3, and Q4 were 0.43 (95%CI: 0.23-0.93; P = 0.030), 0.43 (95%CI: 0.19-0.99; P = 0.046), and 0.41 (95%CI: 0.17-0.98; P = 0.045), respectively. When the SHR and TIR were analyzed in combination, patients with high SHR and low TIR had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (adjusted OR = 2.19; 95%CI: 1.05-4.58; P = 0.038).

Combined SHR and TIR assessment offers prognostic value in surgical ICU patients. Maintaining glucose within the target range may be important to improve short-term outcomes in patients with stress hyperglycemia.

Core Tip: While the stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) has been widely examined as a marker of acute glycemic disturbance, prior studies have largely emphasized its independent prognostic value, often neglecting its interaction with longitudinal glycemic control indicators. In this study, we evaluated the combined effect of SHR and time in range (TIR) on 28-day mortality in surgical ICU patients. We found that patients with both elevated SHR and reduced TIR exhibited the highest risk of death, with a 2.37-fold increase compared to those with low SHR and high TIR. These findings highlight the prognostic relevance of both acute hyperglycemia and persistent glycemic dysregulation, and emphasize the potential value of integrated glucose management strategies in critically ill patients.

- Citation: Liu S, Cao BG, Ma Y, Xu JF, Zhou QH, Wang CR. Combined assessment with stress hyperglycemia ratio and time in range: Associations with twenty-eight-day mortality in surgical intensive care unit patients. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 112621

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/112621.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112621

Stress hyperglycemia, characterized by elevated blood glucose levels resulting from acute illness or stress, is a common physiological response in critically ill patients. Despite its high prevalence, the optimal management of stress hyperglycemia remains uncertain. The stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) has been proposed as a valuable metric; it is calculated by estimating baseline glucose levels from glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels and relating them to admission glucose values, and is thus a relative measure. This ratio offers important insights into stress hyperglycemia at the time of intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Elevated SHR have been associated with 1.5- to 3-fold increased risks of adverse outcomes across diverse critical care populations, underscoring the value of this metric as a potential prognostic marker[1-3]. On the other hand, glycemic variability during hospitalization has been linked strongly to adverse outcomes, including increased mortality among ICU patients[4-6], and the SHR does not capture such dynamic fluctuation. Given the significant prognostic impact of glycemic variability, the use of the SHR alone may be insufficient to capture glycemic disturbance and its implications for patient outcomes in the ICU setting.

The time in range (TIR) metric, defined as the proportion of time that a patient’s glucose level remains within a target range during their ICU stay, offers valuable insight into intra- and inter-day glycemic fluctuations[7]. The TIR (3.9-10.0 mmol/L) has been linked to the progression of chronic diabetic complications[8]. More recently, growing evidence has highlighted the relationships between the TIR and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients, as it not only reflects overall glycemic control but also serves as an indirect measure of glycemic variability[9]. Given that the SHR captures relative hyperglycemia at admission and the TIR reflects ongoing glycemic patterns throughout hospitalization, the combined use of these metrics may enable more comprehensive evaluation of these patients’ glycemic status. Such an integrated approach is essential to refine glycemic management strategies and improve prognostic accuracy, particularly in patients experiencing stress hyperglycemia. However, the joint impact of the TIR and SHR on ICU patient outcomes remains largely unexplored, highlighting a significant gap that warrants further investigation. In the present retrospective cohort study, we evaluated the prognostic value of the SHR, the TIR, and both in combination in surgical ICU patients.

We performed this retrospective study at the Department of Adult Surgical Critical Care Medicine of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital between January 1, 2020, and January 30, 2024. Eligible patients had available HbA1c data, were hospitalized for more than 72 hours, and had at least four capillary blood glucose records per day during their ICU stays. In total, 706 adult patients were enrolled.

Patients’ physical characteristics (age, sex, height, and weight), medical histories, comorbidities, illness severities [acute physiology score and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II (APACHE II) score] were collected on ICU admission. Body mass indices (BMI) were calculated by dividing patients’ weights (in kilograms) by their squared heights (in meters). APACHE II scores were calculated based on the worst vital sign values during the first 24 hours of ICU admission. Diabetes diagnoses were based on a history of diabetes, use of glucose-lowering drugs, and/or HbA1c value ≥ 6.5%.

The first random arterial blood glucose value measured within 24 hours of admission using the GEM 5000 arterial blood gas analyzer (Instrument Laboratories, Bedford, MA, United States) was taken as the admission blood glucose level. Capillary blood glucose readings were obtained using the Accu-Chek® blood glucose test strip monitor (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). HbA1c was measured within 1 month before ICU admission or on the day of ICU admission using the HLC-723G8 analyzer (Tosoh G8; Tosoh Corporation, Japan) in standard mode.

SHR was calculated using the equation: SHR = admission blood glucose level (mmol/L)/[1.59 × HbA1c (%) - 2.59][10]. TIR was calculated using the equation: TIR = number of glucose records within the target range (3.9-10.0 mmol/L)/total number of glucose records[11].

Blood glucose monitoring intervals were at least every 4 hours for patients requiring intravenous (IV) insulin and every 8 hours for all other patients. Initial insulin infusion rates (2-6 IU/hour) were determined using a sliding scale approach based on measured blood glucose levels. To prevent hypoglycemia, IV insulin infusion was stopped when the blood glucose level dropped below 7.8 mmol/L, and the IV administration of concentrated dextrose was recommended when the blood glucose level fell below 3.9 mmol/L.

Continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as n (%). To analyze the associations of the SHR and TIR with 28-day mortality, multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted with the calculation of odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Restricted cubic spline analyses with four knots were used to explore potential nonlinear relationships. The TIR and SHR were entered into the regression models as categorical variables. Their distributions were divided into quartiles (SHR: ≤ 0.96, 0.96-1.17, 1.17-1.46, and > 1.46; TIR: ≤ 0.38, 0.38-0.75, 0.75-0.91, and > 0.91). SHR in the highest quartile (> 1.46) were defined as high, and those in the lower three quartiles (≤ 1.46) were defined as low. TIR in the lower two quartiles (≤ 0.75) were classified as low, and those in the upper two quartiles (> 0.75) were classified as high. To assess the combined effect of the SHR and TIR on 28-day mortality, we categorized patients into four groups: Low SHR and high TIR (SHR-L_TIR-H), low SHR and low TIR (SHR-L_TIR-L), high SHR and high TIR (SHR-H_TIR-H), and high SHR and low TIR (SHR-H_TIR-L) and performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States) and R (version 4.0.4; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The sex, BMI, HbA1c values, and reasons for ICU admission were comparable across survival outcomes. Compared with survivors, non-survivors were significantly older (P < 0.001) and more likely to have diabetes. On ICU admission, non-survivors also had more severe illness, as reflected by significantly higher APACHE II scores [median (IQR): 22.0 (16.0, 27.0) vs 13.5 (9.0, 20.0), P < 0.001], and higher SHR [median (IQR): 1.29 (0.99, 1.67) vs 1.16 (0.96, 1.44), P = 0.017]. Non-survivors had a significantly lower TIR during ICU stays compared with survivors [53.0% (23.1%, 87.6%) vs 77.0% (42.9%, 91.5%), P < 0.001]. In terms of treatments and supportive measures, non-survivors were more likely to receive glucocorticoids. They also had longer ICU stays.

| Variables | Total (n = 706) | Survivors (n = 616) | Non-survivors (n = 90) | P value |

| Age (years) | 69.50 (60.00, 78.75) | 69.00 (59.00, 78.00) | 76.50 (66.50, 83.00) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.333 | |||

| Female | 300 (42.49) | 266 (43.18) | 34 (37.78) | |

| Male | 406 (57.51) | 350 (56.82) | 56 (62.22) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.44 (21.30, 25.81) | 23.66 (21.30, 25.82) | 23.31 (21.48, 25.76) | 0.233 |

| APACHE II | 15.00 (10.00, 21.00) | 13.50 (9.00, 20.00) | 22.00 (16.00, 27.00) | < 0.001 |

| Admission type | 0.460 | |||

| Emergency surgery | 343 (48.58) | 296 (48.05) | 47 (52.22) | |

| Elective surgery | 363 (51.42) | 320 (51.95) | 43 (47.78) | |

| History of diabetes | 0.006 | |||

| Yes | 283 (40.08) | 235 (38.15) | 48 (53.33) | |

| No | 423 (59.92) | 381 (61.85) | 42 (46.67) | |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.90 (5.50, 6.90) | 5.90(5.50, 6.90) | 6.40 (5.57, 7.25) | 0.146 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 103 (84, 119) | 104 (86, 120) | 95 (76, 118) | 0.037 |

| TIR (%) | 75.0 (38.1, 90.9) | 77.0 (42.9, 91.5) | 53.0 (23.1, 87.6) | < 0.001 |

| SHR | 1.17 (0.97, 1.46) | 1.16 (0.96, 1.44) | 1.29 (0.99, 1.67) | 0.017 |

| Use of glucocorticoid | 0.017 | |||

| Yes | 193 (27.34) | 159 (25.81) | 34 (37.78) | |

| No | 513 (72.66) | 457 (74.19) | 56 (62.22) | |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 5.00 (3.44, 11.10) | 4.93 (3.08, 9.90) | 10.30 (4.89, 15.65) | < 0.001 |

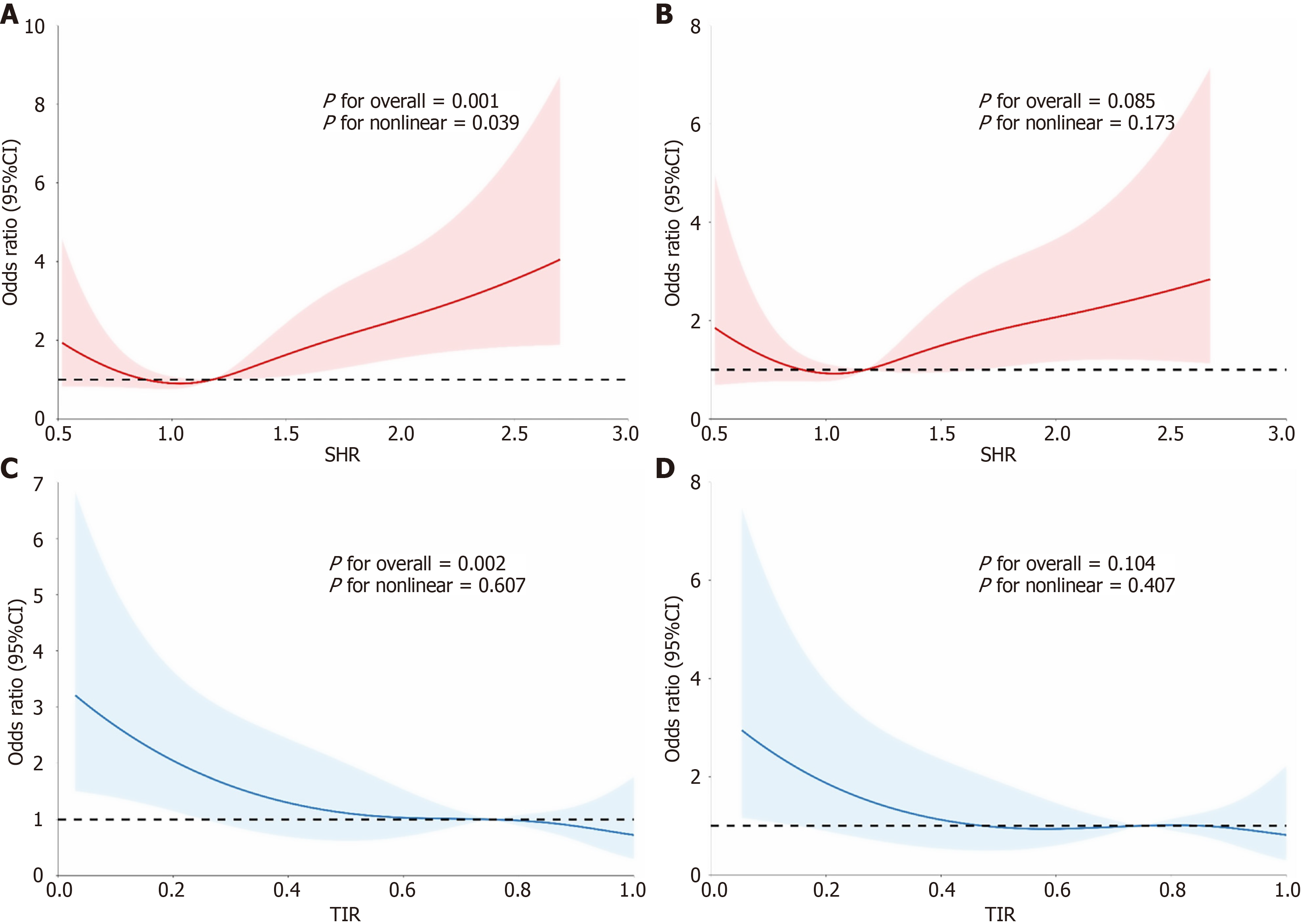

The unadjusted restricted cubic spline analysis revealed a U-shaped relationship between the SHR and mortality (P for nonlinearity = 0.039; Figure 1A and B). In contrast, the TIR demonstrated a significant negative linear relationship with the 28-day mortality risk (overall P = 0.002, P for nonlinearity = 0.607; Figure 1C and D). Due to the U-shaped relationship of the SHR with mortality, the second SHR quartile was selected as the reference group for the logistic regression analysis. Patients in the highest quartile (Q4) had a significantly increased risk of 28-day mortality in the unadjusted (OR = 3.00; 95%CI: 1.52-5.91; P = 0.001) and adjusted (adjusted OR = 2.24; 95%CI: 1.06-4.71; P = 0.035) models (Table 2). No significant association was found for the first (Q1) or third quartile (Q3) compared with the reference group. Conversely, higher TIR were associated with a reduced risk of 28-day mortality. Compared with the lowest quartile (Q1), adjusted ORs for the upper three quartiles were 0.46 (95%CI: 0.23-0.93; P = 0.017), 0.43 (95%CI: 0.19-0.99; P = 0.046), and 0.41 (95%CI: 0.17-0.98; P = 0.045), respectively (Table 2).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted P value | |

| SHR | ||||

| Q1 | 1.62 (0.78-3.36) | 0.198 | 1.37 (0.62-3.03) | 0.433 |

| Q2 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Q3 | 1.90 (0.93-3.88) | 0.079 | 1.48 (0.68-3.18) | 0.322 |

| Q4 | 3.00 (1.52-5.91) | 0.001 | 2.24 (1.06-4.71) | 0.035 |

| TIR | ||||

| Q1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Q2 | 0.44 (0.25-0.79) | 0.011 | 0.46 (0.23-0.93) | 0.030 |

| Q3 | 0.39 (0.21-0.73) | 0.006 | 0.43 (0.19-0.99) | 0.046 |

| Q4 | 0.37 (0.20-0.69) | 0.005 | 0.41 (0.17-0.98) | 0.045 |

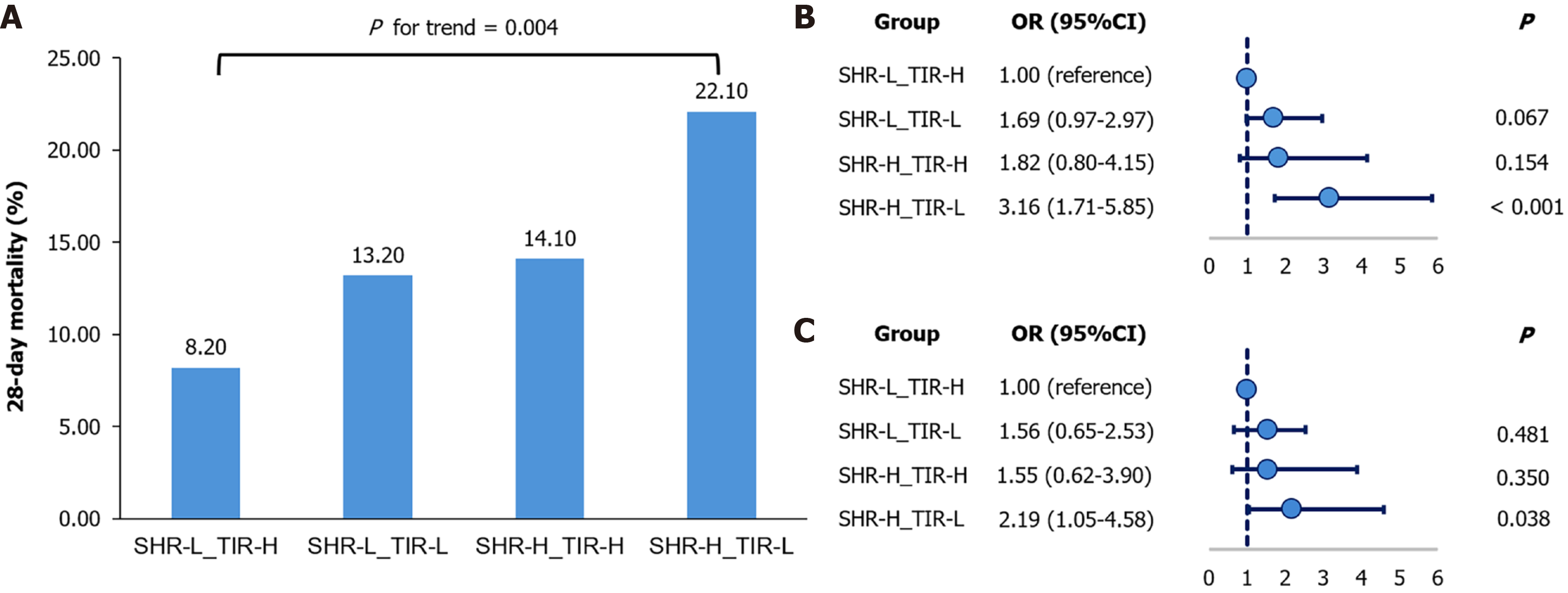

In the combined analysis, 28-day mortality differed significantly among the four patient groups and was highest in the SHR-H_TIR-L group (P for trend = 0.004; Figure 2A). This group had a 3.16-fold higher risk of 28-day mortality than did the reference group (SHR-L_TIR-H; OR = 3.16; 95%CI: 1.71-5.85; P < 0.001; Figure 2B). This association remained significant after adjustment for age, gender, BMI, APACHE II, history of diabetes, and reason for ICU admission (adjusted OR = 2.19; 95%CI: 1.05–4.58; P = 0.038; Figure 2C). No significant difference was observed for the SHR-H_TIR-H or SHR-L_TIR-L group compared with the reference. To examine whether these associations varied across clinically relevant subgroups, we conducted stratified analyses. While some variation in effect estimates was observed (e.g., among emergency surgery and trauma patients), the overall associations between combined SHR/TIR groups and 28-day mortality were directionally similar across diabetes status, admission type, disease category, and glucocorticoid use. Importantly, none of the interaction tests reached statistical significance (all P for interaction > 0.05; Supplementary Table 1).

In this study, we investigated the combined impact of the SHR and TIR on 28-day mortality among surgical ICU patients. Our analysis revealed a U-shaped relationship between the SHR and mortality, whereas the TIR had a consistent, linear protective effect against the mortality risk. Notably, patients with elevated SHR and reduced TIR had the highest 28-day mortality risk, with a 2.19-fold increase compared with patients with low SHR and high TIR. These results highlight the clinical importance of maintaining higher TIR to improve outcomes in critically ill patients, especially those with stress-induced hyperglycemia.

We observed a U-shaped relationship between the SHR and 28-day mortality among surgical ICU patients, with both low and high SHR associated with increased risk. This observation is consistent with previous findings from various critically ill populations. For example, Guo et al[12] reported that both low and high SHR were associated with increased short- and long-term mortality in medical and surgical ICU patients, and Yan et al[13] demonstrated that the SHR had U-shaped associations with 28-day all-cause mortality and in-hospital mortality in a cohort of patients with sepsis. Although no universal consensus exists regarding the definition of high SHR, previous findings suggest that values > 1.3-1.5 are associated with adverse outcomes in critically ill patients[14-16]. Among patients undergoing cardiac surgery, those in the highest postoperative SHR quartile (> 1.40) had a significantly higher 30-day mortality risk than those in lower quartiles (adjusted OR = 2.88)[17]. In our study, the upper quartile cutoff for the SHR was 1.46, which falls within the previously reported range and supports the validity of our data-driven classification. Several physiological mechanisms may explain this relationship. SHR elevation is often driven by the excessive counter-regulatory release of hormones (e.g., cortisol and catecholamines), the activation of inflammatory cytokines, and insulin resistance, all of which can contribute to endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and multi-organ injury[17,18]. On the other hand, abnormally low SHR may represent inadequate metabolic response to physiological stress or over-treatment with insulin, both of which can impair tissue perfusion, especially in critically ill patients. The SHR is thus an important early predictor of prognosis in ICU patients and should be considered in risk assessment and clinical management. Given that HbA1c levels may be influenced by anemia and other factors in critically ill patients, we additionally performed a sensitivity analysis with the exclusion of patients with severe anemia, and the results were consistent with the main findings (Supplementary Table 2).

In this study, we found that the TIR (3.9-10 mmol/L) was associated independently with low 28-day mortality, suggesting that the maintenance of surgical ICU patients’ glucose levels within this range is an effective strategy to improve short-term outcomes. Consistent with previous reports, we found an inverse association between the TIR and mortality. Krinsley and Preiser[9] reported that higher TIR (3.9-7.8 mmol/L) levels were associated with significantly reduced mortality in non-diabetic ICU patients, and Lanspa et al[19] reported that the TIR (3.9-7.8 mmol/L) was associated independently with reduced 30-day mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. In our study, the TIR (3.9-10 mmol/L) was associated independently with low 28-day mortality, suggesting that the maintenance of surgical ICU patients’ glucose levels within this range is an effective strategy to improve short-term outcomes.

However, the optimal TIR thresholds for critically ill patients remain uncertain. Current international guidelines, such as the International Consensus on TIR and the American Diabetes Association’s 2025 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, recommend TIR (3.9-10 mmol/L) > 70% for most individuals with type 2 diabetes to prevent chronic complications[11,20]. These recommendations, however, were derived from outpatient diabetes management studies and have not been validated in ICU settings. Different thresholds have been used for critically ill cohorts, due partly to heterogeneity in patient characteristics and treatment strategies. For instance, Krinsley and Preiser[9] used a median-based cutoff of > 80% within 3.9-7.8 mmol/L, whereas different ranges have been applied in other studies depending on cohort characteristics. In line with these approaches, we adopted a data-driven method, dividing TIR values into quartiles and defining ≤ 75% as low (Q1 and Q2) and > 75% as high (Q3 and Q4). This approach ensured internal consistency and facilitated comparison with previous ICU studies, although we acknowledge that such cutoffs may have limited direct clinical applicability.

He et al[21] investigated the combined impact of the SHR and the coefficient of variation (CV) of all plasma glucose measurements recorded during the ICU stay on outcomes in ICU patients with coronary artery disease. They found that patients with elevated SHR (> 1.16) and high CV (> 27.3) had the highest risk of in-hospital mortality. We observed a similar trend in our analysis of the SHR and TIR. Notably, whereas He et al[21] reported that high SHR combined with low CV significantly increased in-hospital mortality, we found that high TIR were associated with a protective effect, even in the presence of elevated SHR, and that low CV was not linked consistently to improved outcomes (data not shown). CV captures the overall magnitude of glucose fluctuations over time, whereas the TIR reflects the stability of glycemic control. Our findings suggest that TIR is a more meaningful metric for glucose monitoring and management in surgical ICU patients in the context of stress hyperglycemia. However, these conclusions apply primarily to patients who survived and received ≥ 3 days of treatment and monitoring in the ICU; they may not necessarily apply to patients who experienced very early mortality.

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective, single-center, observational design may have introduced selection bias, limited the generalizability of the findings and precluded causal inference. Second, the data were inevitably incomplete due to the retrospective nature of the study; as exact dates of death were not collected, survival and time-to-event analyses could not be performed. The lack of certain clinical and biochemical data, such as that on stress hormones, inflammatory mediators, and oxidative stress markers, restricted our ability to explore the underlying mechanisms linking the SHR and TIR to mortality. Third, the cutoffs for TIR were determined using a data-driven method, which may limit their direct clinical applicability. Finally, the restriction of inclusion to patients with ICU stays ≥ 72 hours may have led to the exclusion of those who died early and introduced immortal time bias, thereby leading to the overestimation of the protective effect of the TIR. Future studies with prospective, multicenter designs, comprehensive data collection, and precise event time data are needed to validate these findings and allow full survival analyses.

The findings of this study demonstrate that combined assessment with the SHR and TIR has significant prognostic value for surgical ICU patients. The implementation of targeted interventions to control stress hyperglycemia and optimize glucose management during critical care may be a crucial strategy to improve 28-day survival outcomes.

| 1. | Lyu Z, Ji Y, Ji Y. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and postoperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in noncardiac surgeries: a large perioperative cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang Y, Yan Y, Sun L, Wang Y. Stress hyperglycemia ratio is a risk factor for mortality in trauma and surgical intensive care patients: a retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29:558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhou Y, Liu L, Huang H, Li N, He J, Yao H, Tang X, Chen X, Zhang S, Shi Q, Qu F, Wang S, Wang M, Shu C, Zeng Y, Tian H, Zhu Y, Su B, Li S; WECODe Study Group. 'Stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital prognosis in non-surgical patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | He HM, Xie YY, Wang Z, Li J, Zheng SW, Li XX, Jiao SQ, Yang FR, Sun YH. Associations of variability in blood glucose and systolic blood pressure with mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: A retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV database. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024;209:111595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen Y, Yang Z, Liu Y, Gue Y, Zhong Z, Chen T, Wang F, McDowell G, Huang B, Lip GYH. Prognostic value of glycaemic variability for mortality in critically ill atrial fibrillation patients and mortality prediction model using machine learning. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang F, Guo Y, Tang Y, Zhao S, Xuan K, Mao Z, Lu R, Hou R, Zhu X. Combined assessment of stress hyperglycemia ratio and glycemic variability to predict all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases across different glucose metabolic states: an observational cohort study with machine learning. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025;24:199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wright EE Jr, Morgan K, Fu DK, Wilkins N, Guffey WJ. Time in Range: How to Measure It, How to Report It, and Its Practical Application in Clinical Decision-Making. Clin Diabetes. 2020;38:439-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gabbay MAL, Rodacki M, Calliari LE, Vianna AGD, Krakauer M, Pinto MS, Reis JS, Puñales M, Miranda LG, Ramalho AC, Franco DR, Pedrosa HPC. Time in range: a new parameter to evaluate blood glucose control in patients with diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Krinsley JS, Preiser JC. Time in blood glucose range 70 to 140 mg/dl >80% is strongly associated with increased survival in non-diabetic critically ill adults. Crit Care. 2015;19:179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zia-Ul-Sabah, Alqahtani SAM, Wani JI, Aziz S, Durrani HK, Patel AA, Rangraze I, Mirdad RT, Alfayea MA, Shahrani S. Stress hyperglycaemia ratio is an independent predictor of in-hospital heart failure among patients with anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24:751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, Amiel SA, Beck R, Biester T, Bosi E, Buckingham BA, Cefalu WT, Close KL, Cobelli C, Dassau E, DeVries JH, Donaghue KC, Dovc K, Doyle FJ 3rd, Garg S, Grunberger G, Heller S, Heinemann L, Hirsch IB, Hovorka R, Jia W, Kordonouri O, Kovatchev B, Kowalski A, Laffel L, Levine B, Mayorov A, Mathieu C, Murphy HR, Nimri R, Nørgaard K, Parkin CG, Renard E, Rodbard D, Saboo B, Schatz D, Stoner K, Urakami T, Weinzimer SA, Phillip M. Clinical Targets for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data Interpretation: Recommendations From the International Consensus on Time in Range. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1593-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3057] [Cited by in RCA: 2609] [Article Influence: 372.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Guo JY, Chou RH, Kuo CS, Chao TF, Wu CH, Tsai YL, Lu YW, Kuo MR, Huang PH, Lin SJ. The paradox of the glycemic gap: Does relative hypoglycemia exist in critically ill patients? Clin Nutr. 2021;40:4654-4661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yan F, Chen X, Quan X, Wang L, Wei X, Zhu J. Association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study and predictive model establishment based on machine learning. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu J, Zhou Y, Huang H, Liu R, Kang Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Gao Y, Li Y, Wang C, Chen S, Xie N, Zheng X, Meng R, Liu Y, Tan N, Gao F. Impact of stress hyperglycemia ratio on mortality in patients with critical acute myocardial infarction: insight from american MIMIC-IV and the chinese CIN-II study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | You X, Zhang H, Li T, Zhu Y, Zhang Z, Chen X, Huang P. Stress hyperglycemia ratio and 30-day mortality among critically ill patients with acute heart failure: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Acta Diabetol. 2025;62:1537-1547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pei Y, Ma Y, Xiang Y, Zhang G, Feng Y, Li W, Zhou Y, Li S. Stress hyperglycemia ratio and machine learning model for prediction of all-cause mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025;24:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet. 2009;373:1798-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1077] [Cited by in RCA: 1029] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vedantam D, Poman DS, Motwani L, Asif N, Patel A, Anne KK. Stress-Induced Hyperglycemia: Consequences and Management. Cureus. 2022;14:e26714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lanspa MJ, Krinsley JS, Hersh AM, Wilson EL, Holmen JR, Orme JF, Morris AH, Hirshberg EL. Percentage of Time in Range 70 to 139 mg/dL Is Associated With Reduced Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients Receiving IV Insulin Infusion. Chest. 2019;156:878-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 16. Diabetes Care in the Hospital: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48:S321-S334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | He HM, Zheng SW, Xie YY, Wang Z, Jiao SQ, Yang FR, Li XX, Li J, Sun YH. Simultaneous assessment of stress hyperglycemia ratio and glycemic variability to predict mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: a retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/