Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112027

Revised: September 4, 2025

Accepted: November 28, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 182 Days and 2.5 Hours

The incidence of diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is increasing significantly as the population ages. DCM is one of the main causes of heart failure and mortality among patients with diabetes. Impaired mitophagy leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, which in turn aggravates DCM progression. Microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 4 (MARK4) is a key regulator of autophagy in adipocytes.

To investigate the role of MARK4 in mitophagy in DCM.

A mouse model of type 2 DCM was developed by administration of low-dose streptozotocin (50 mg/kg) combined with a high-fat diet. After 12 weeks MARK4 expression was knocked down in the mice by injection of the adeno-associated virus AAV9 into the tail vein. Four weeks later, cardiac function and structure were evaluated by echocardiography, and blood glucose levels and body weights were recorded. Mitochondrial ultrastructure and autophagosomes were assessed using electron microscopy. Mitochondrial membrane potentials were examined using fluorescence microscopy while the MARK4 and mitophagy-associated protein levels were investigated using western blotting. The downstream factors of MARK4 were identified using RNA-seq sequencing and bioinformatics with empirical confirmation.

MARK4 levels were markedly increased in the DCM animal and cardiomyocyte models. Downregulation of MARK4 in DCM mice reduced myocardial tissue injury, increased mitophagy, and mitigated damage to cardiac function. RNA-seq indicated that MARK4 downregulation promoted mitophagy via upregulation of UNC-51-like kinase 1, alleviating myocardial injury in mice. This was confirmed in cell rescue experiments. Bioinformatics predicted interaction between MARK4 and the autophagy marker protein microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B. This was verified using co-immunoprecipitation.

Downregulation of MARK4 in DCM mice can reduce myocardial injury, protect mitochondrial function, and promote mitophagy by upregulating UNC-51-like kinase 1, protecting against cardiac damage.

Core Tip: This study explored the role of microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 4 (MARK4) in diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM). The results showed that the MARK4 level was significantly elevated in DCM mice. Downregulation of MARK4 could alleviate myocardial injury and enhance mitochondrial autophagy function. By upregulating UNC-51-like kinase 1, the downregulation of MARK4 promoted mitochondrial autophagy and protected cardiac function. This study revealed the significance of MARK4 as a potential therapeutic target for DCM, providing new ideas for protecting the myocardium of patients with diabetes.

- Citation: Wu Y, Wang WY, Zhang JQ, Wang S, Zeng Z, Fu L, Li B. Microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 4 exacerbates diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting UNC-51-like kinase 1-mediated mitochondrial autophagy. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 112027

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/112027.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.112027

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a major cardiovascular complication of type 2 diabetes. It is associated with increased mortality in patients with diabetes. Studies in DCM animal models have demonstrated that mitophagy has protective functions, selectively eliminating damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria and protecting cardiomyocytes[1,2]. While autophagy is generally inactivated in mice after consuming a high-fat diet (HFD) for 20 weeks, mitophagy persists[3]. This selective autophagy of mitochondria is a critical mechanism that helps maintain cardiac function in the context of obesity and DCM[4]. This suggests that regulating mitophagy may be an efficient strategy for delaying DCM progression.

Microtubule affinity-regulatory kinase (MARK) family proteins regulate microtubule dynamics through tau-microtubule binding. The MARK family primarily comprises four proteins, namely, MARK1, 2, 3, and 4[5]. The genes encoding MARK proteins share 45% homology, and MARKs belong to the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) sub

UNC-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) is a conserved serine/threonine protein kinase located on human chromosome 2. It regulates mitophagy[9-13] in various cell types and is involved in the formation of early membrane structures within autophagosomes. Knockout of ULK1 in mice inhibits autophagy[14]. Regulatory signals upstream of ULK1 include mTOR, p53, and AMPK, whereas downstream signals include Beclin1, p62, and myosin II. Pang et al[15] reported that overexpression of ULK1 in goat testicular supporting cells increased the levels of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), Beclin1, autophagy-related protein (Atg)5, and Atg7, activating autophagy. As ULK1 is an initiator of autophagy, further studies investigating regulation of its levels and activity may provide novel insights for the treatment and prevention of various autophagy-related disorders.

Here, the mechanism by which MARK4 exacerbates cardiac injury was investigated in DCM model mice. RNA-seq and bioinformatics analyses showed that MARK4 inhibits mitophagy mediated by ULK1. Co-immunoprecipitation assays confirmed that MARK4 interacts with the autophagy marker protein LC3B. The findings provide a theoretical and empirical base for the function of MARK4 in regulating mitophagy in DCM.

Four-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were housed at a stable temperature with sufficient access to water and food. The care of and experimentation with these animals adhered to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for standardized animal procedures. Following a 2-week acclimatization, the mice were randomly assigned to a group fed on a normal chow diet (ND; D12450, Research Diets, NJ, United States) and a group fed a HFD (D12492, Research Diets, NJ, United States) for 8 weeks. After this period freshly prepared streptozotocin (STZ; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, United States) dissolved in 0.1 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5) was injected intraperitoneally (50 mg/kg) for 5 days while the ND mice received equivalent amounts of buffer. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) was measured 7 days after the last injection, and animals with FBG levels consistently above 16.7 mmol/L in three tests were used for subsequent experiments[16]. The diabetic and control mice were then maintained on their respective HFD or ND for an additional 4 weeks. At the study endpoint all mice were sacrificed by barbiturate overdose (intravenous pentobarbital sodium, 150 mg/kg) for tissue collection.

An AAV9 vector containing small hairpin (sh) RNA with a cardiac troponin T promoter was constructed to target MARK4 (AAV9-shMARK4), with AAV9-shNC as a negative control. After 12 weeks diabetic mice were given either AAV9-shMARK4 or AAV9-shNC through intravenous injection (5 × 1011 viral particles per mouse) and then maintained on their respective diets for an additional 4 weeks as described[17]. Body weights and FBG levels were monitored every 4 weeks. The mice were sacrificed via carbon dioxide asphyxiation after 16 weeks, and the heart tissues were collected. The experimental groups were as follows: Control (Con group); DCM; DCM + AAV9-shMARK4; and DCM + AAV9-shNC.

Similarly, a recombinant AAV9 vector carrying the mouse ULK1 sequence was used to overexpress ULK1 (OE-ULK1). Mice were separated into 4 experimental groups: Control; DCM; DCM + OE-ULK1; and DCM + OE-NC.

Newborn C57BL/6 mice were disinfected with 75% alcohol, and their hearts were removed. After trimming other tissues away, the hearts were cut into small pieces. The heart fragments were placed in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 1 mL of 0.25% pancreatic enzyme for digestion. After 1 min the supernatant was mixed with DMEM (10% serum and 1% cyan/streptomycin). The process was repeated until the samples were completely digested and was followed by filtration and centrifugation with cardiomyocytes obtained from the supernatant after 1.5 h. The cardiomyocytes were grown in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C with 5% CO2. To mimic the hyperglycemic and hyperlipid toxicity associated with the progression of DCM, cardiomyocytes were grown in a medium with 200 μM palmitic acid (PA) and 33.3 mmol/L glucose (HG) for 24 h[18].

Cells were infected for 24 h with lentiviruses containing sh-MARK4, sh-ULK1, and OE-ULK1 at a multiplicity of infection of 50 after which the media were replaced with DMEM with 5-10 μg/mL puromycin or 20 μg/mL neomycin. Overexpression of ULK1 was achieved by overexpressing the coding sequence region of the gene to increase its expression level (Table 1).

| sh-RNA | Nucleotide sequence |

| sh-MARK4-1 | GTTCAGAGAAGTCCGAATTAT |

| sh-MARK4-2 | GGUCACAAGUUGCCAUCUATT |

| sh-MARK4-3 | GTTGAAGGGACTCAACCACCC |

| sh-ULK1-1 | GCCCAGCACCTGTGGTATTTA |

| sh-ULK1-2 | GGTGGCCGTCAAATGCATTAA |

| sh-ULK1-3 | GCTGAGCGTCAAGGTCACTAA |

Four weeks following viral infection, cardiac function was assessed using an 8 MHz transducer and a Philips Sonos 5500 (WA, United States) multifunctional color ultrasound system. Anesthetized mice were positioned on their backs on a heating pad for ultrasound examination. The left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVIDs), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, left ventricular shortening fraction (LVFS), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were measured and documented.

The hearts were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, followed by embedding in paraffin and continuous sectioning. The sections were stained with Masson’s stain and hematoxylin and eosin, followed by imaging (Olympus BX51, Japan) as described previously[17].

Total RNA was isolated from myocardial tissue or cardiomyocytes using an RNA isolation kit (Takara Bio, Japan) and reverse-transcribed to complementary DNA using a kit (FSQ-101, TOYOBO, Japan) as directed. Amplification was performed using SYBR Green in an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, CA, United States). The primer sequences were as follows: ULK1 forwards: 5’-CAGTTAGGTTCACTGCAGACTTG-3’, reverse: 5’-TTTATCCGTCTTCTGCTATTGG-3’; and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) forwards: 5’-GGCACAGTCAAGGCTGAGAATG-3’, reverse: 5’-ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGTA-3’. GAPDH was used as the internal standard. The mRNA levels of each gene were calculated via the 2-ΔΔCT method.

Proteins were obtained from lysed tissue samples and quantified (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Antibodies against the following proteins were used: MARK4 (#4834, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, United States), p62 (ab109012, 1:10000, Abcam, United Kingdom), Parkin (#4211, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, United States), Beclin1 (ab207612, 1:2000, Abcam, United Kingdom), LC3B (ab48394, 1 μg/mL, Abcam, United Kingdom), ULK1 (20986-1, 1:1000, Proteintech, CA, United States), and GAPDH (TA-08, 1:5000, Zsbio, Beijing, China).

Mitochondrial membrane potentials (MMPs) were measured using a JC-1 staining kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, C2003S). After treatment cells were harvested and rinsed with PBS. After resuspension in phenol red and serum-containing medium (1 mL), cells were treated with 1 mL of JC-1 working solution. The suspension was mixed thoroughly and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C in a humidified incubator. After collection cells were rinsed twice with JC-1 buffer to remove excess dye. Finally, 2 mL of fresh culture medium was added, and cells were examined and imaged under a fluorescence microscope.

Treated primary cardiomyocytes were frozen at -80 °C before RNA extraction. After quality assessments sequencing was performed. Genes with log2(fold change) ≥ 1 and an adjusted P value of < 0.05 were considered significantly differentially expressed[17]. They were analyzed by Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes enrichment.

The immunoprecipitation procedure was carried out using an IP kit (abs955, Absin, Shanghai, China). Briefly, proteins were isolated from cells as described above, and 0.5-1.0 mg of protein in 500 μL was incubated with 5 μL each of protein A and protein G for 1.5 h at 4 °C. After centrifugation the total protein lysate was obtained and was free of specific binding proteins. Subsequently, 5 μg of the anti-MARK4 antibody along with appropriate IgG (eBiosciences, CA, United States) was added to the precleaned lysate, and the samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with slow rotation. To capture the antigen-antibody complex, an additional 5 μL of both protein A and protein G was introduced for 3 h at 4 °C. After three gentle washes the agarose particle antibody-antigen complexes were collected and resuspended in 20-40 μL of sodium-dodecyl sulfate buffer after which western blotting (WB) was performed.

The protein interaction network was constructed in STRING.

Heart samples were rinsed in phosphate buffer, fixed with osmium acid fixative for 2 h, and then rinsed again with phosphate buffer and ultrapure water. The samples were dehydrated in ethanol and acetone gradients at 4 °C before embedding with acetone and resin with replacement of the resin every 3 h. The samples were cured in an oven and sectioned before staining with 3% uranyl acetate and lead citrate and evaluation and imaging under transmission electron microscopy (Hitachi, Japan).

Data from three independent experiments were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and are shown as the mean ± SD. Group differences were evaluated using either analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test or t tests for pairwise comparisons. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

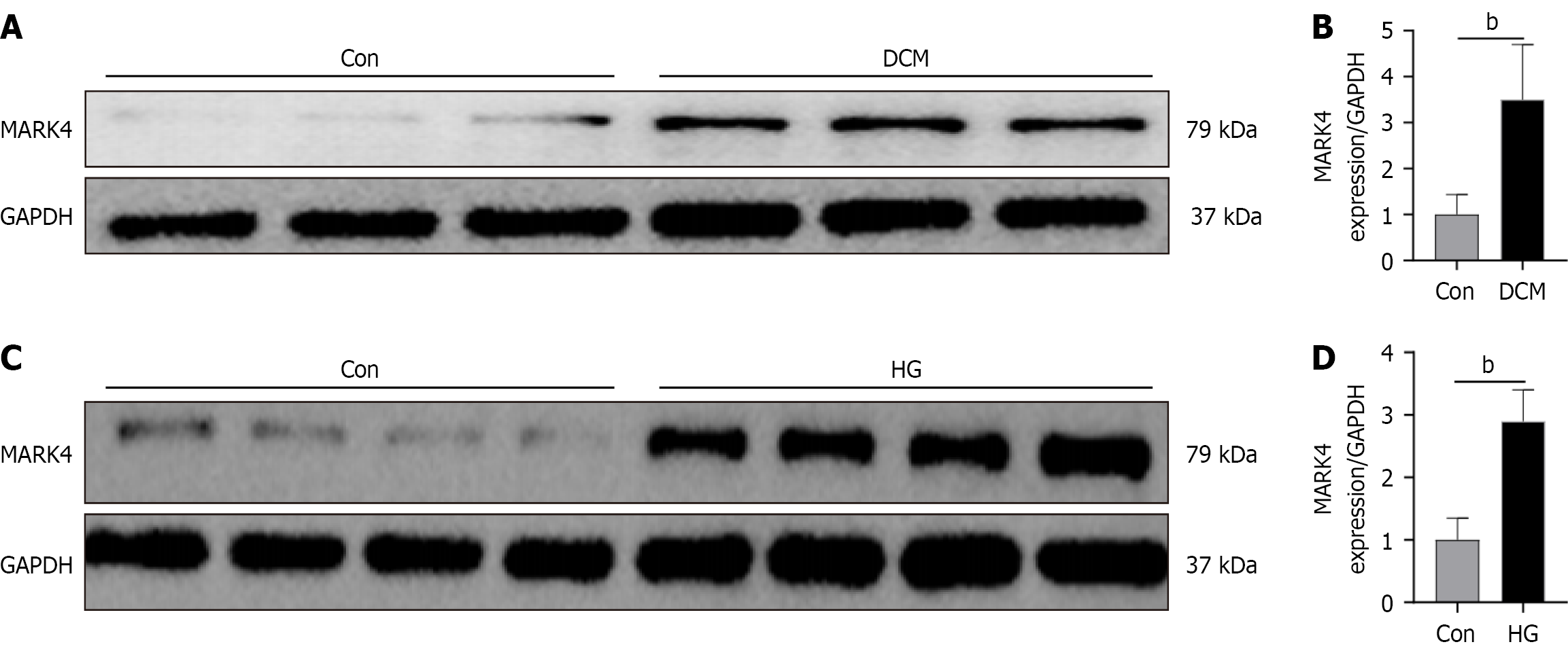

As shown in Figure 1A and B, MARK4 levels were markedly increased in the DCM mice relative to the Con group. Similar results were obtained in the cellular model (Figure 1C and D), indicating that DCM raised the levels of MARK4 in both animal and cellular models.

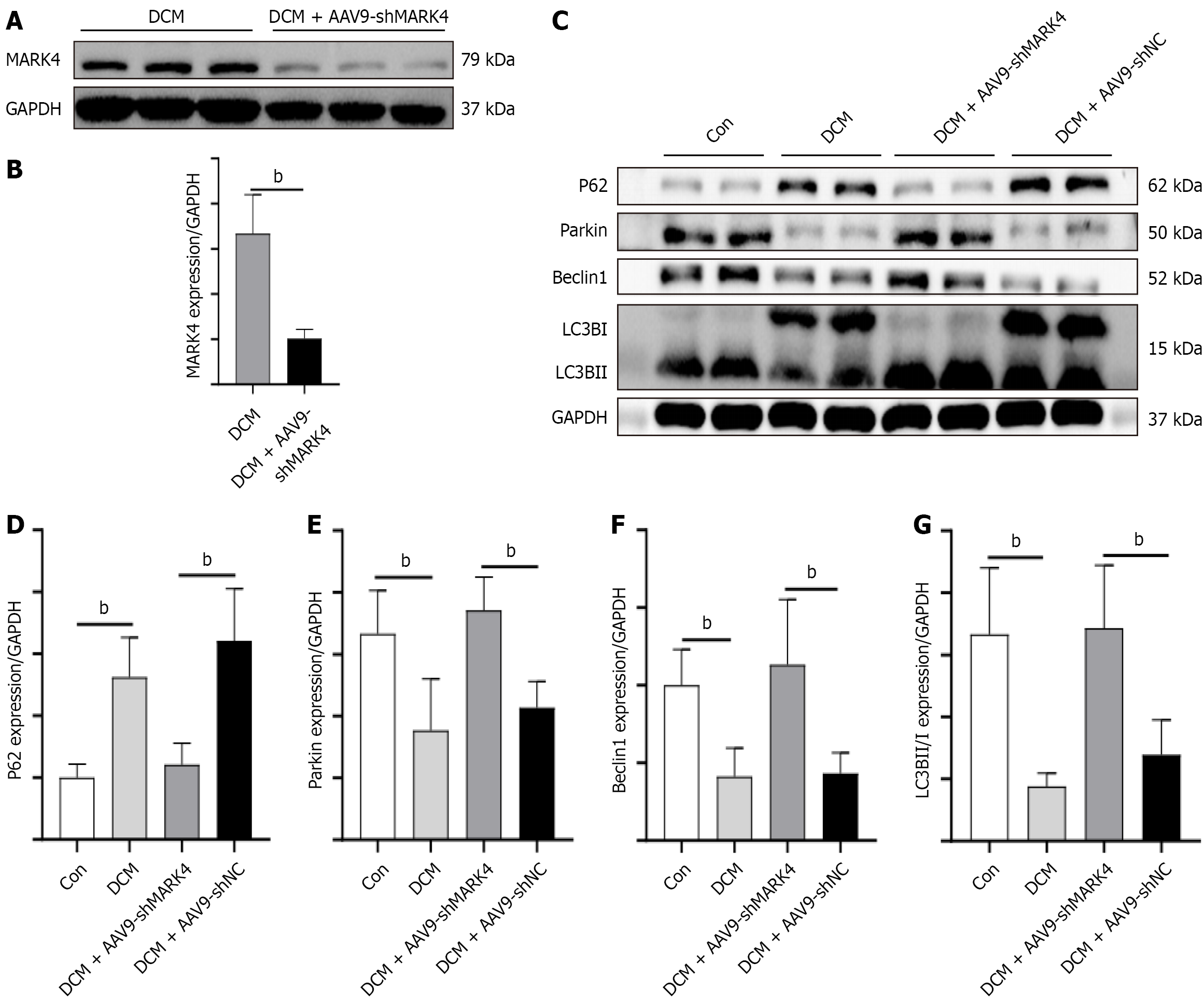

As illustrated in Figure 2A and B, the levels of MARK4 in the DCM + AAV9-shMARK4 group were substantially lower than those in the DCM group, indicating success of the knockdown process. We also examined the expression of MARK4 in renal tissues and found no significant difference in the expression of MARK4 between the DCM and DCM + AAV9-shMARK4 groups (Supplementary Figure 1). The levels of mitophagy-associated proteins, including p62, Parkin, Beclin1, and LC3B, were then measured. Compared with the Con group, the DCM group exhibited a decrease in Beclin1, Parkin, and LC3B levels as well as an increase in p62 expression. However, the DCM + AAV9-shMARK4 group showed elevated levels of Beclin1, Parkin, and LC3B while p62 levels decreased when compared with the DCM + AAV9-shNC group (Figure 2C-G). p62 (also known as sequestosome 1) is an autophagy receptor, connecting autophagic substrates to autophagosomes. During the autophagic process p62 is degraded, and its level typically decreases as autophagic activity increases. These results suggest that MARK4 modulates mitophagy in DCM and that its silencing can promote mitophagy in this context.

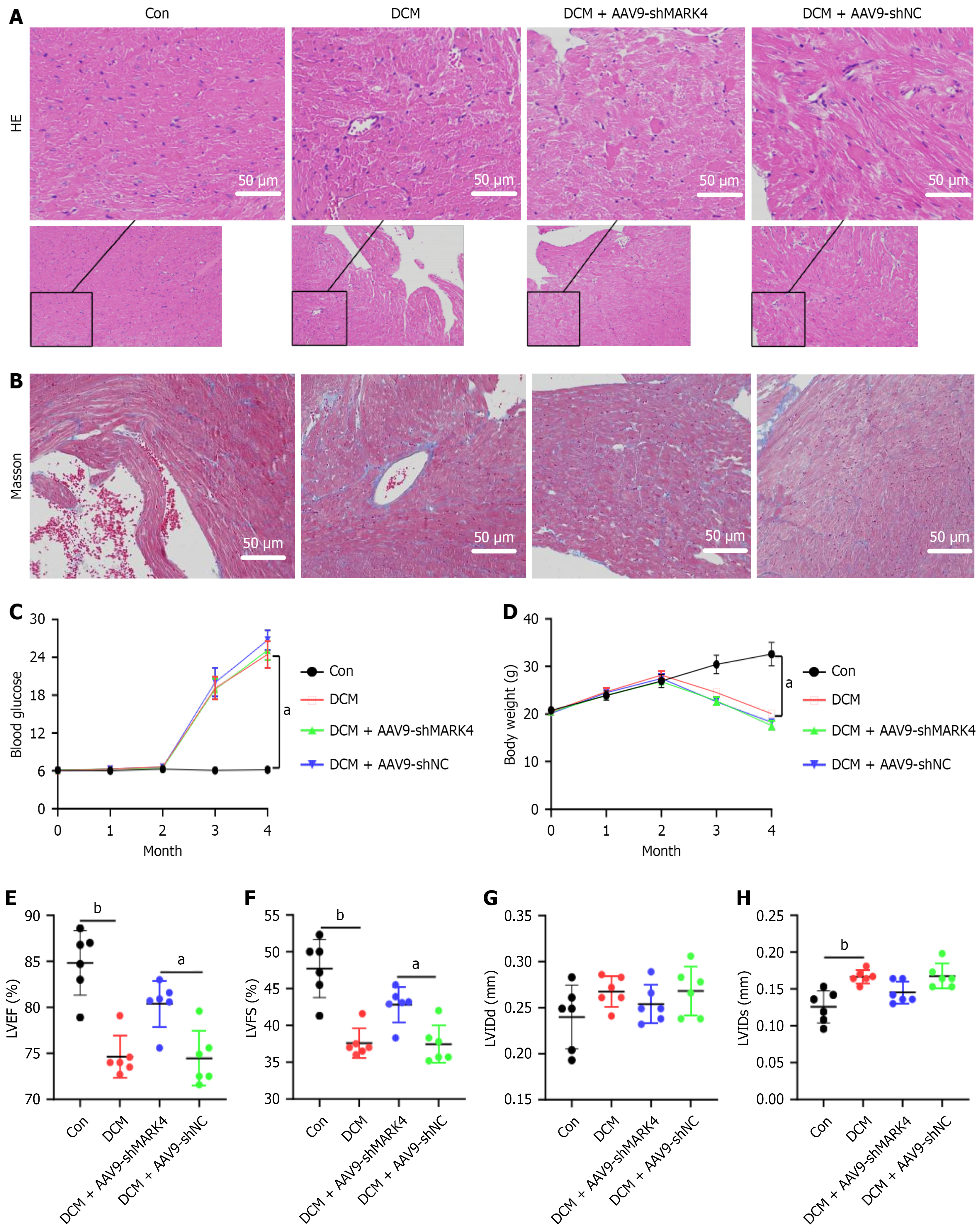

The hematoxylin and eosin and Masson’s staining results revealed that in the Con group tissues the myocardial fibers were tightly and regularly arranged with clearly visible nuclei and collagen fiber deposition. However, tissues from the DCM and the DCM + AAV9-shNC groups exhibited enlarged intercellular spaces, unclear nuclei, edema, and collagen fiber deposition. Knockdown of MARK4 alleviated the pathological damage to myocardial cells, and collagen deposition was reduced (Figure 3A and B).

Changes in FBG and body weight are also important indicators of DCM (Figure 3C and D). Compared with those in the Con group, FBG levels in the DCM, DCM + AAV9-shMARK4, and DCM + AAV9-shNC groups were significantly raised while body weight decreased, indicative of diabetes. Echocardiography results revealed that LVEF and LVFS were lower and the LVIDs were greater in the DCM group relative to the Con group, suggesting that the heart function of the DCM model mice was impaired. However, compared with those in the DCM + AAV9-shNC group, both LVFS and LVEF were greater and the LVIDs were lower in the DCM + AAV9-shMARK4 group, whereas the left ventricular end-diastolic diameter did not differ significantly among the four groups (Figure 3E-H). These results indicate that inhibiting MARK4 expression in DCM model mice can alleviate their impaired heart function.

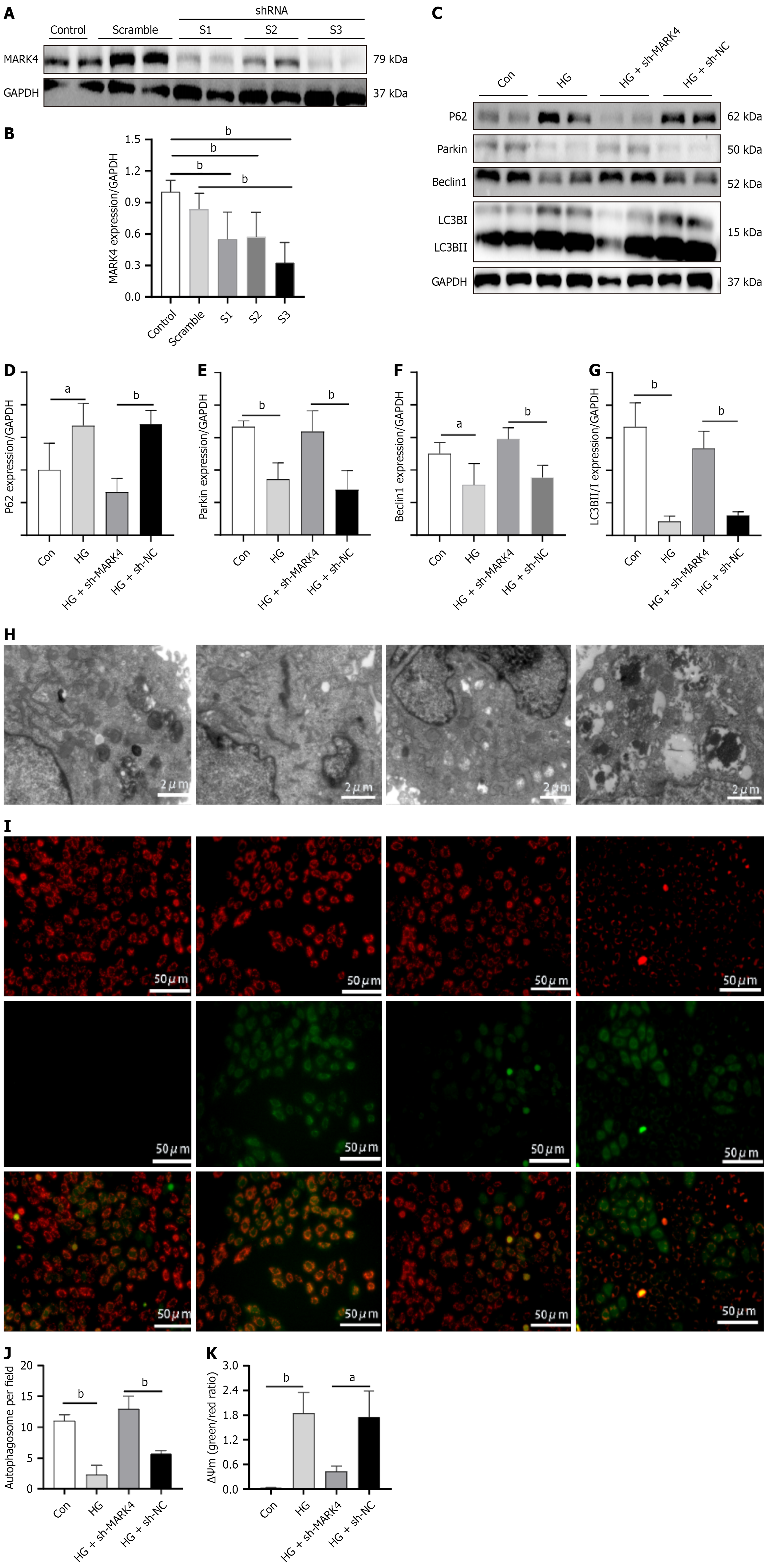

Knockdown efficiency was assessed using WB. Compared with the Con group, protein expression in S1, S2, and S3 was markedly decreased (Figure 4A and B). Relative to the scramble group, only the S3 group showed reduced levels. We ultimately chose to package S3 into a lentivirus for subsequent cell experiments. Next, the effect of MARK4 knockdown on mitophagy in cardiomyocytes stimulated with HG and PA was investigated (Figure 4C-G). Relative to the Con group, increased levels of p62 and decreased expression of Parkin, Beclin1, and LC3B were observed. Compared with the HG + sh-NC group, the HG + sh-MARK4 group showed reduced p62 and increased Parkin, Beclin1, and LC3B. Electron microscopy showed reduced mitophagy in the HG group relative to the Con group while mitophagy was greater in the HG + sh-MARK4 group than in the HG + sh-NC group (Figure 4). These results suggest that MARK4 knockdown promoted mitophagy in cardiomyocytes stimulated with HG and PA.

The MMP is a critical indicator of mitochondrial function. Under normal conditions cells stained with JC-1 exhibit more red and less green fluorescence. When the MMP is impaired, green fluorescence increases, while red fluorescence decreases. As illustrated in Figure 4, relative to the Con group the HG group showed enhanced green fluorescence and decreased red fluorescence. Compared with the HG + sh-NC group, the HG + sh-MARK4 group exhibited increased red fluorescence and decreased green fluorescence, indicating that inhibiting MARK4 expression in cardiomyocytes with HG and PA stimulation can alleviate mitochondrial dysfunction.

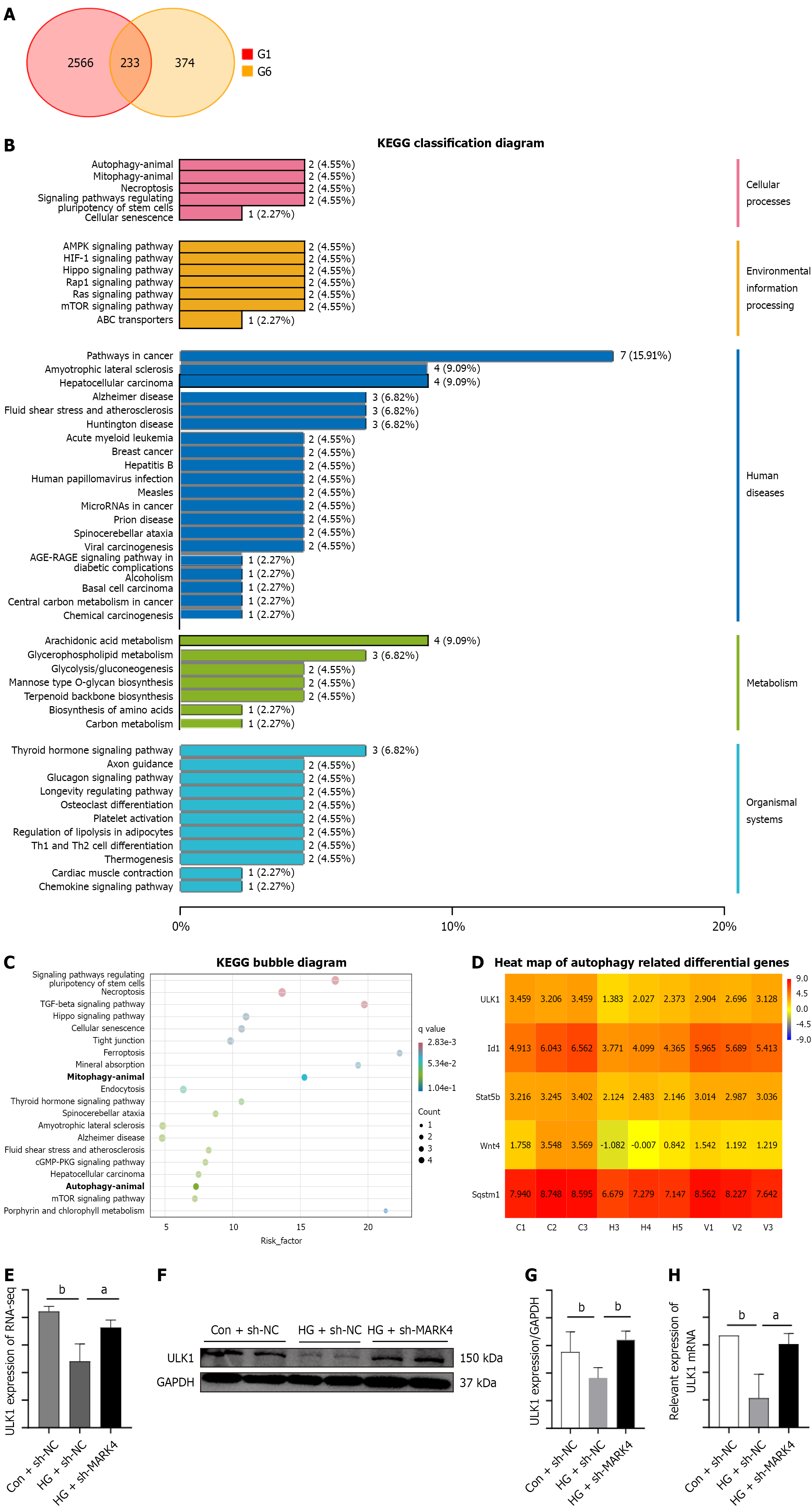

The cardiomyocytes were divided into three groups for second-generation RNA sequencing. Intersections between the 2799 downregulated genes from the Con + sh-NC vs the HG + sh-NC groups were determined as well as the 607 upregulated genes from the HG + sh-NC group vs the HG + sh-MARK4 group, resulting in the identification of 233 overlapping genes (Figure 5A)[19-21]. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analysis identified the pathways associated with these 233 differentially expressed genes, demonstrating enrichment in autophagy-related pathways (Figure 5B and C). Relative to the HG + sh-NC group, ULK1 showed marked upregulation in the HG + sh-MARK4 group (Figure 5D and E), a finding that was further verified by real time PCR and WB (Figure 5F-H).

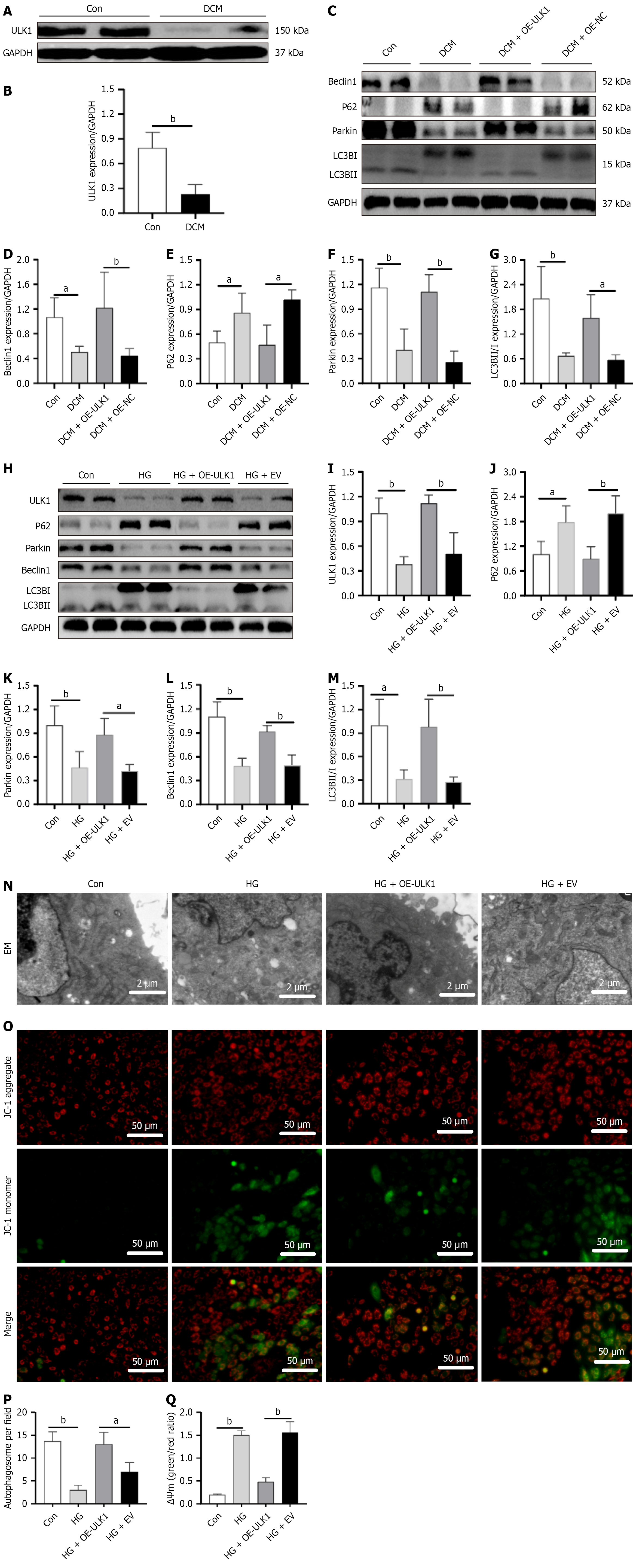

ULK1 levels were markedly lower in DCM mice relative to the controls (Figure 6A and B). Investigation of the changes in mitophagy-associated proteins in DCM model mice and cardiomyocytes following ULK1 overexpression indicated that relative to the Con group animals DCM mice showed reduced levels of Beclin1, Parkin, and LC3B along with increased p62. Relative to the DCM + OE-NC group, the DCM + OE-ULK1 group exhibited increased levels of Beclin1, Parkin, and LC3B with reduced p62 (Figure 6C-G). Thus, the results from the animal and cellular models were consistent (Figure 6H-M).

Electron microscopy revealed lower autophagosome numbers in the HG group relative to the Con group. However, the HG + OE-ULK1 group had more autophagosomes than the HG + empty vector group did. Examination of MMP values indicated reductions in the HG group relative to the Con group. However, the membrane potentials in the HG + OE-ULK1 group were higher than those in the HG + empty vector group, indicating alleviation of mitochondrial dysfunction. The results suggest that overexpression of ULK1 promotes mitophagy and protects mitochondrial function in the DCM model (Figure 6N-Q).

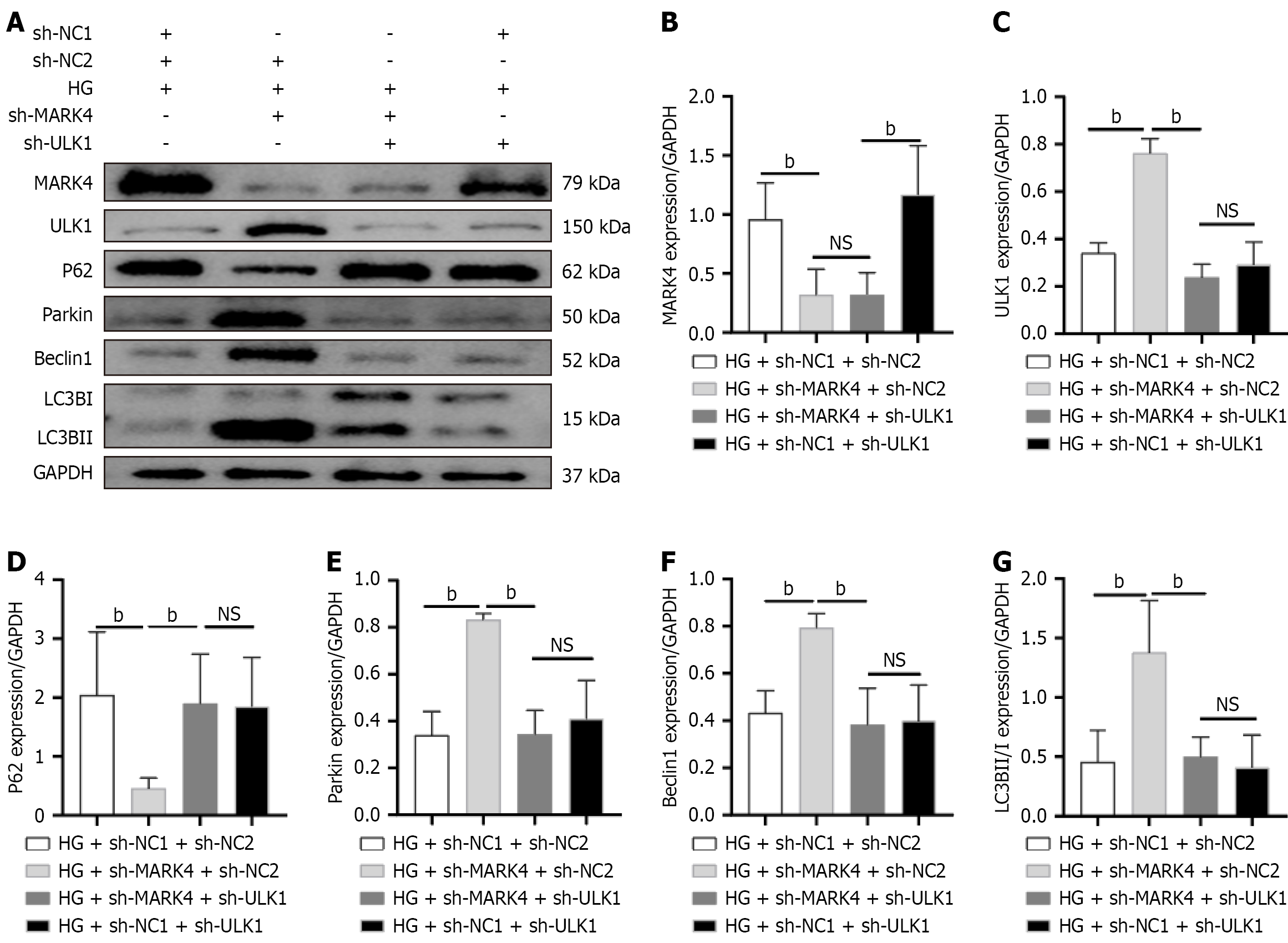

To verify that reduced MARK4 promotes mitophagy in cardiomyocytes stimulated with HG and PA through the upregulation of ULK1, a cell rescue experiment was designed. As shown in Figure 7, relative to those in the HG + sh-NC1 + sh-NC2 group, the levels of MARK4 and p62 in the HG + sh-MARK4 + sh-NC2 group were lower, whereas the levels of ULK1, Parkin, Beclin1, and LC3B were elevated. Relative to the HG + sh-MARK4 + sh-NC2 group, HG + sh-MARK4 + sh-ULK1 cells showed reduced levels of ULK1, Parkin, Beclin1, and LC3B and increased p62 levels. Relative to the HG + sh-MARK4 + sh-ULK1 group, the HG + sh-NC1 + sh-ULK1 group showed upregulated MARK4 but no substantial differences in the levels of ULK1, p62, Parkin, Beclin1, or LC3B between the two groups. These results indicate that MARK4 influences mitophagy in myocardial cells via ULK1 and that downregulating MARK4 promotes mitophagy in response to HG and PA stimulation by upregulating ULK1 expression. However, through co-immunoprecipitation assays it was found that ULK1 and MARK4 do not interact with each other (Supplementary Figure 2).

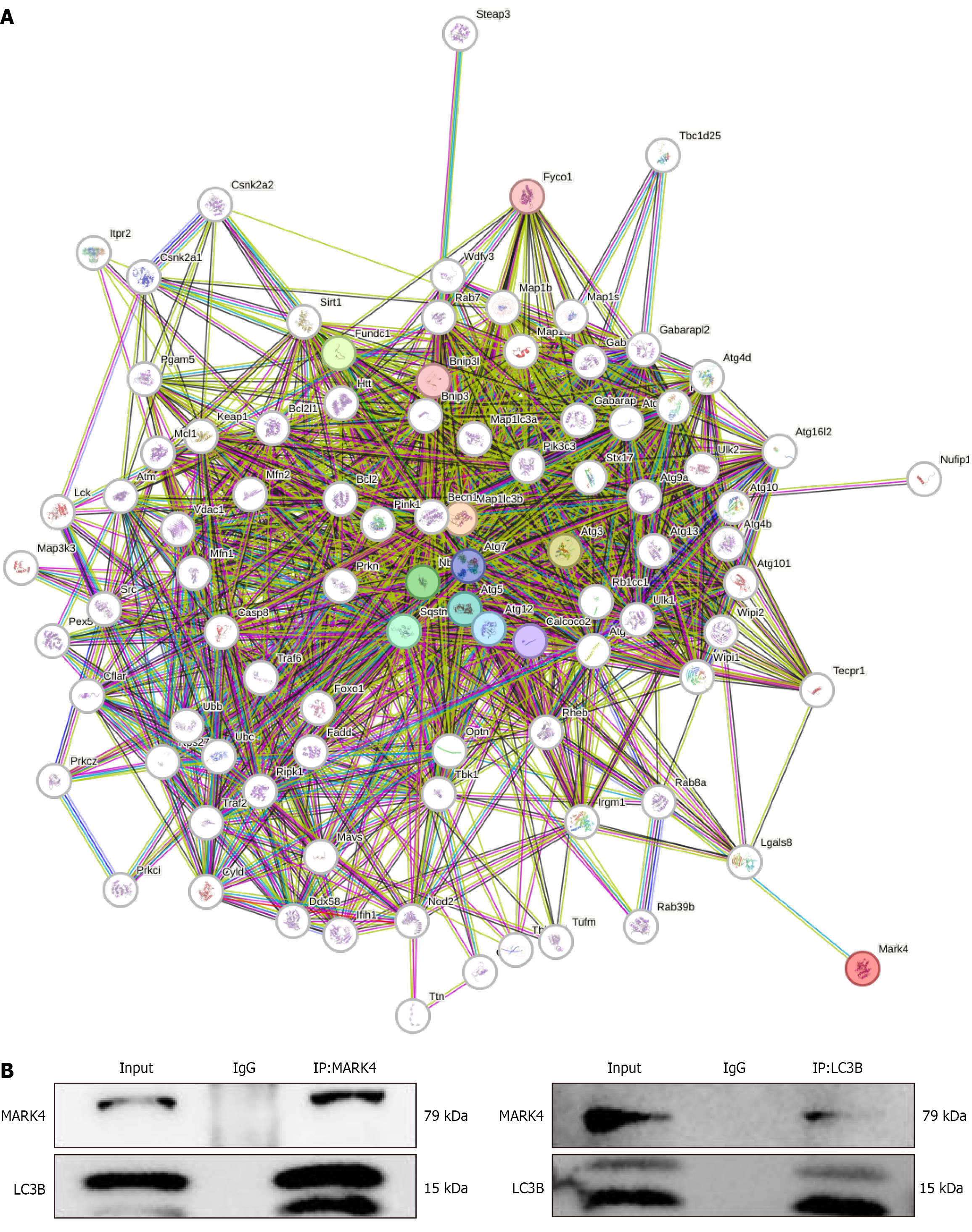

To further elucidate the potential mechanism by which MARK4 regulates autophagy, bioinformatics was utilized to predict the proteins that interact with MARK4. The proteins predicted to interact with MARK4 are shown in Figure 8A. Previous studies have shown that LC3B, also known as Map1 LC3B, is a mitophagy marker. Co-immunoprecipitation assays in cardiomyocytes indicated that MARK4 and LC3B interacted (Figure 8B).

In this study raised levels of MARK4 were observed in DCM model mice. Furthermore, reductions in MARK4 levels in the myocardium alleviated myocardial damage, provided cardioprotection, and enhanced mitophagy through ULK1 and interaction with the autophagy marker LC3B. This finding was similar to our previous research results showing upregulation of MARK4 in DCM while reduced levels inhibited myocardial apoptosis and oxidative stress and enhanced mitochondrial fusion and acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4-associated lipid oxidation, leading to cardioprotection[17]. These results highlight MARK4 as a potential therapeutic target in DCM.

MARK proteins are primarily involved in the cell cycle and signal transduction; however, increasing evidence suggests their involvement in regulating cellular homeostasis and metabolism[19-21]. Among them, MARK4 modulates lipid metabolism, inflammation, and oxidative stress[22-26]. Several studies have shown that MARK4 can regulate the contractility of cardiomyocytes by modulating microtubule deacylation, indicating its potential as a target for improving cardiac function in mice following myocardial infarction[27]. Other studies have shown that MARK4 positively regulates autophagy in adipocytes under conditions of serum starvation or rapamycin treatment, promoting adipocyte autophagy through the AMPK/protein kinase B/mTOR pathway and blocking the browning of white adipose tissue[8]. The results suggest that MARK4 is closely associated with both heart failure and autophagy.

Autophagy is a fundamental cellular process that maintains intracellular homeostasis by transporting damaged cellular components to lysosomes for degradation and subsequent recycling[28]. It has been found that autophagy is a key cardioprotective process following acute myocardial injury[29-31]. It is also a major mechanism for mitochondrial clearance, making it essential for mitochondrial quality control. Mitochondrial damage resulting from cardiac injury can produce reactive oxygen species and induce the production of death-inducing factors, thus exacerbating myocardial damage[32]. Removal of damaged mitochondria through “mitochondrial autophagy” can prevent further cellular damage. However, continued autophagy can also lead to cardiac atrophy[33].

In DCM mitochondrial autophagy is critical to maintaining the standard function and shape of the heart[34]. It is an important quality control mechanism for maintaining cardiac mitochondrial function, especially when stimulated by HFD. When mitophagy is impaired, lipid accumulation and mitochondrial destruction occur in cardiomyocytes, exacerbating DCM. Therefore, regulating mitophagy in DCM may be an effective therapeutic strategy for delaying disease progression. Here, it was observed that in DCM model mice fed an HFD for 16 weeks, the levels of p62 were markedly increased, whereas those of Beclin1, Parkin, and LC3B were markedly decreased. p62 expression is generally believed to be negatively correlated with autophagy activity, whereas levels of Beclin1, Parkin, and LC3B are typically positively correlated with autophagy activity. These results suggest that mitophagy was inhibited in DCM model fed HFDs.

This is consistent with previous studies, indicating that autophagy was decreased, the protein levels of Beclin1 and LC3B were decreased, and those of p62 were increased in diabetic hearts and high glucose-stimulated cardiomyocytes[35]. Previous studies have demonstrated that MARK4 regulates the browning of white adipose tissue by mediating mitophagy. Although it is not known whether MARK4 affects mitophagy in DCM, our previous research showed that MARK4 exacerbates cardiac dysfunction in DCM mice via regulation of acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4-mediated lipid metabolism in myocardial tissues. During lipid metabolism the oxidation and synthesis of fatty acids require substantial energy with mitochondria serving as the primary sites for ATP generation. By removing dysfunctional mitochondria and ensuring the normal function of the remaining mitochondria, mitophagy provides the energy supply required for lipid metabolism. Downregulation of MARK4 in DCM model mice can raise the levels of Beclin1, Parkin, and LC3B while those of p62 decrease. These results indicate that downregulating MARK4 in DCM model mice can promote mitophagy with consistent findings in both animal and cellular models.

Transcriptomic analysis revealed downregulation of ULK1 in cardiomyocytes stimulated with HG and PA while this decrease was reversed following knockdown of MARK4. ULK1, a conserved serine/threonine protein kinase encoded by a gene located on human chromosome 2, consists of 1050 amino acids and is involved in regulating autophagy[9-12]. ULK1 is important for mitophagy in various cell types and is involved in the formation of membrane structures within early autophagosomes. In a study of ULK1 gene-knockout mice, autophagy was found to be strongly inhibited[14]. Similarly, Pang et al[15] reported that overexpression of ULK1 in goat testicular supporting cells raised the levels of LC3, Beclin1, Atg7, and Atg5 and induced autophagy. These findings are consistent with our results, indicating that ULK1 overexpression in DCM animal and cell models promotes mitophagy.

To further investigate the regulatory relationship between MARK4 and ULK1, a complementary experiment was conducted in which MARK4 was inhibited in cardiomyocytes stimulated with HG and PA, followed by knockdown of ULK1. This approach successfully downregulated both MARK4 and ULK1 in cardiomyocytes stimulated with HG and PA. The results revealed that the levels of the mitophagy-associated protein ULK1, which was downregulated by MARK4 inhibition, were comparable with those in the model group. In summary, the silencing of MARK4 in cardiomyocytes stimulated with HG and PA promotes mitophagy by upregulating ULK1.

LC3B is a mammalian homolog of Atg8 and is a key marker of autophagy. Bioinformatics analysis predicted that MARK4 could interact with LC3B. This was then verified by co-immunoprecipitation experiments. This suggests that MARK4 is a key modulator of mitophagy in cardiomyocytes, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for further research into the function of MARK4 in cardiovascular diseases.

The present findings demonstrated that MARK4 affected myocardial mitochondrial autophagy by regulating the expression of ULK1; however, the specific mechanism involved in this process has not yet been fully elucidated. Future studies should investigate potential pathways, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and transcriptional regulation. This study showed that myocardial tissue injury, increased myocardial fibrosis, reduced cardiac function, mitochondrial dysfunction, and decreased mitophagy in DCM mice were reversed following knockdown of MARK4 by AAV9-shMARK4. These results suggest that therapeutic strategies aimed at suppressing MARK4 expression may hold promise for managing DCM.

However, the study had several limitations. The DCM model established by low-dose STZ and HFD differs from other models of diabetes. The earliest DCM model, the db/db mouse, is a spontaneous model of type 2 diabetes characterized by leptin deficiency. The db/db mouse model is frequently used to study endocrine dysfunction, obesity, immunity, and inflammation, among other conditions. However, no significant differences in the rates of myocardial injury, myocardial fibrosis, decreased cardiac function, mitochondrial dysfunction, or impaired mitochondrial autophagy have been observed between the STZ/HFD and the db/db diabetes models[36-40]. However, further investigation is needed to examine whether changes in MARK4 alleviate mitochondrial dysfunction and promote mitophagy.

Developing drugs targeting MARK4 as a therapeutic target is of great significance for the treatment of patients with DCM.

| 1. | Mukai R, Sadoshima J. A Novel Inducer of Autophagy in the Heart. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021;6:381-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Varga ZV, Giricz Z, Liaudet L, Haskó G, Ferdinandy P, Pacher P. Interplay of oxidative, nitrosative/nitrative stress, inflammation, cell death and autophagy in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:232-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ikeda Y, Sciarretta S, Nagarajan N, Rubattu S, Volpe M, Frati G, Sadoshima J. New insights into the role of mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy during oxidative stress and aging in the heart. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:210934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mu J, Zhang D, Tian Y, Xie Z, Zou MH. BRD4 inhibition by JQ1 prevents high-fat diet-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy by activating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2020;149:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Espinosa L, Navarro E. Human serine/threonine protein kinase EMK1: genomic structure and cDNA cloning of isoforms produced by alternative splicing. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;81:278-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5931] [Cited by in RCA: 6089] [Article Influence: 253.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 7. | Bright NJ, Thornton C, Carling D. The regulation and function of mammalian AMPK-related kinases. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2009;196:15-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang K, Cai J, Pan M, Sun Q, Sun C. Mark4 Inhibited the Browning of White Adipose Tissue by Promoting Adipocytes Autophagy in Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kabeya Y, Kamada Y, Baba M, Takikawa H, Sasaki M, Ohsumi Y. Atg17 functions in cooperation with Atg1 and Atg13 in yeast autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2544-2553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yang YY, Gao ZX, Mao ZH, Liu DW, Liu ZS, Wu P. Identification of ULK1 as a novel mitophagy-related gene in diabetic nephropathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1079465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zachari M, Ganley IG. The mammalian ULK1 complex and autophagy initiation. Essays Biochem. 2017;61:585-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 630] [Article Influence: 70.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Torii S, Shimizu S. Involvement of phosphorylation of ULK1 in alternative autophagy. Autophagy. 2020;16:1532-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mukhopadhyay S, Das DN, Panda PK, Sinha N, Naik PP, Bissoyi A, Pramanik K, Bhutia SK. Autophagy protein Ulk1 promotes mitochondrial apoptosis through reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;89:311-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McAlpine F, Williamson LE, Tooze SA, Chan EY. Regulation of nutrient-sensitive autophagy by uncoordinated 51-like kinases 1 and 2. Autophagy. 2013;9:361-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pang J, Han L, Liu Z, Zheng J, Zhao J, Deng K, Wang F, Zhang Y. ULK1 affects cell viability of goat Sertoli cell by modulating both autophagy and apoptosis. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2019;55:604-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang Z, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Ji T, Li W, Li W. Protective effects of AS-IV on diabetic cardiomyopathy by improving myocardial lipid metabolism in rat models of T2DM. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127:110081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu Y, Zhang J, Wang W, Wu D, Kang Y, Fu L. MARK4 aggravates cardiac dysfunction in mice with STZ-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy by regulating ACSL4-mediated myocardial lipid metabolism. Sci Rep. 2024;14:12978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yao Q, Ke ZQ, Guo S, Yang XS, Zhang FX, Liu XF, Chen X, Chen HG, Ke HY, Liu C. Curcumin protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy by promoting autophagy and alleviating apoptosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;124:26-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jeon S, Kim YS, Park J, Bae CD. Microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 1 (MARK1) is activated by electroconvulsive shock in the rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1608-1618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Segu L, Pascaud A, Costet P, Darmon M, Buhot MC. Impairment of spatial learning and memory in ELKL Motif Kinase1 (EMK1/MARK2) knockout mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:231-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bachmann M, Hennemann H, Xing PX, Hoffmann I, Möröy T. The oncogenic serine/threonine kinase Pim-1 phosphorylates and inhibits the activity of Cdc25C-associated kinase 1 (C-TAK1): a novel role for Pim-1 at the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48319-48328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu Z, Gan L, Chen Y, Luo D, Zhang Z, Cao W, Zhou Z, Lin X, Sun C. Mark4 promotes oxidative stress and inflammation via binding to PPARγ and activating NF-κB pathway in mice adipocytes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Feng M, Tian L, Gan L, Liu Z, Sun C. Mark4 promotes adipogenesis and triggers apoptosis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by activating JNK1 and inhibiting p38MAPK pathways. Biol Cell. 2014;106:294-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sun C, Tian L, Nie J, Zhang H, Han X, Shi Y. Inactivation of MARK4, an AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-related kinase, leads to insulin hypersensitivity and resistance to diet-induced obesity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38305-38315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li X, Thome S, Ma X, Amrute-Nayak M, Finigan A, Kitt L, Masters L, James JR, Shi Y, Meng G, Mallat Z. MARK4 regulates NLRP3 positioning and inflammasome activation through a microtubule-dependent mechanism. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mishra SR, Mahapatra KK, Behera BP, Patra S, Bhol CS, Panigrahi DP, Praharaj PP, Singh A, Patil S, Dhiman R, Bhutia SK. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a driver of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its modulation through mitophagy for potential therapeutics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2021;136:106013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yu X, Chen X, Amrute-Nayak M, Allgeyer E, Zhao A, Chenoweth H, Clement M, Harrison J, Doreth C, Sirinakis G, Krieg T, Zhou H, Huang H, Tokuraku K, Johnston DS, Mallat Z, Li X. MARK4 controls ischaemic heart failure through microtubule detyrosination. Nature. 2021;594:560-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mizushima N, White E, Rubinsztein DC. Breakthroughs and bottlenecks in autophagy research. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27:835-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Gottlieb RA. Enhancing macroautophagy protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29776-29787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Logue SE, Sayen MR, Jinno M, Kirshenbaum LA, Gottlieb RA, Gustafsson AB. Response to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury involves Bnip3 and autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:146-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Matsui Y, Takagi H, Qu X, Abdellatif M, Sakoda H, Asano T, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Distinct roles of autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion: roles of AMP-activated protein kinase and Beclin 1 in mediating autophagy. Circ Res. 2007;100:914-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1259] [Article Influence: 66.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kubli DA, Gustafsson ÅB. Mitochondria and mitophagy: the yin and yang of cell death control. Circ Res. 2012;111:1208-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 532] [Cited by in RCA: 660] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Schips TG, Wietelmann A, Höhn K, Schimanski S, Walther P, Braun T, Wirth T, Maier HJ. FoxO3 induces reversible cardiac atrophy and autophagy in a transgenic mouse model. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:587-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zech ATL, Singh SR, Schlossarek S, Carrier L. Autophagy in cardiomyopathies. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2020;1867:118432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang H, Wang L, Hu F, Wang P, Xie Y, Li F, Guo B. Neuregulin-4 attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy by regulating autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR signalling pathway. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tan YY, Chen LX, Fang L, Zhang Q. Cardioprotective effects of polydatin against myocardial injury in diabetic rats via inhibition of NADPH oxidase and NF-κB activities. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20:378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhang D, Li Y, Wang W, Lang X, Zhang Y, Zhao Q, Yan J, Zhang Y. NOX1 promotes myocardial fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction via activating the TLR2/NF-κB pathway in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:928762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Wang SY, Zhu S, Wu J, Zhang M, Xu Y, Xu W, Cui J, Yu B, Cao W, Liu J. Exercise enhances cardiac function by improving mitochondrial dysfunction and maintaining energy homoeostasis in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Med (Berl). 2020;98:245-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lin C, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Yang K, Hu J, Si R, Zhang G, Gao B, Li X, Xu C, Li C, Hao Q, Guo W. Helix B surface peptide attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy via AMPK-dependent autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;482:665-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Li X, Ke X, Li Z, Li B. Vaspin prevents myocardial injury in rats model of diabetic cardiomyopathy by enhancing autophagy and inhibiting inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;514:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/