Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.111165

Revised: July 21, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 204 Days and 6.4 Hours

Diabetic osteoporosis (DOP), a serious complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), involves ferroptosis-mediated disruption of bone metabolism. While en

To investigate whether EC-Exos protect against HG-induced osteoblast ferroptosis through microRNA (miR)-335-3p-mediated regulation of prostaglandin endope

Mouse vascular endothelial cells (bEND.3) and osteoblasts (MC3T3E1) were used. Exosomes were isolated and subsequently characterized by transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and western blotting for CD63 and CD81. miR expression profiles were compared between HG-treated osteoblasts and exosome-cocultured groups using high-throughput sequencing and quanti

EC-Exos significantly reduced reactive oxygen species levels and malondialdehyde, while increasing GSH in HG-treated osteoblasts. miR-335-3p expression increased 3.7-fold in exosome-treated cells vs HG controls. miR-335-3p directly bound the PTGS2 3’ untranslated region. Inhibition of miR-335-3p abolished exo

EC-Exos affect ferroptosis in osteoblasts induced by HG by activating miR-335-3p/PTGS2. Serum miR-335-3p may be a novel diagnostic biomarker.

Core Tip: Endothelial cell-derived exosomes demonstrate inherent bone-targeting properties, their role in counteracting high glucose-induced osteoblast ferroptosis re

- Citation: Shao C, Zhang LJ, Song YL, Wang YQ, Zha XJ, Li J, Ye CS, Chen LL, Chen MW, Jin GX. Endothelial cell-derived exosomes inhibit high glucose-induced osteoblast ferroptosis by activating microRNA-335-3p/prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(1): 111165

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i1/111165.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i1.111165

Diabetic osteoporosis (DOP) is a common complication of diabetes. Every year, there are > 9 million cases of osteoporotic fractures worldwide; most of which are related to DOP[1]. Although increasing clinical evidence suggests that the diabetic microenvironment has a devastating impact on bone metabolism, the potential pathophysio

Exosomes (Exos) are nanoscale extracellular vesicles (40-160 nm) released by numerous cells. They participate in mul

In this study, we selected the mouse vascular endothelial cell line bEND.3 and the mouse osteoblast cell line MC3T3E1 to observe the morphological characteristics of EC-Exos, determined the concentration and particle size distribution of Exos, and observed the capacity of MC3T3E1 cells to take up EC-Exos. Through high-throughput sequencing, we ana

The bEND.3 mouse vascular endothelial cell line and MC3T3E1 mouse osteoblast cell line (both from Pricella, Wuhan, China) were maintained under standardized conditions of 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO2. Both cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (VivaCell, Shanghai, China), which was enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution. To ensure cells were in the logarithmic growth phase and retained high viability for subsequent experiments, trypsin digestion was employed for cell passage.

The procedures for the isolation and identification of Exos adhered to the “Minimal Information for Studies of Ex

In the growth phase, MC3T3E1 cells were plated in a 24-well cell culture plate at 105 cells per well. A working solution of the red fluorescent dye PKH26 Exo (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was prepared under dark conditions. This was achieved by diluting the PKH26 stock solution with Diluent B in a 9:1 ratio (Diluent B to PKH26 stock solution by volume). For every 500 μg of Exo protein, 100 μL dye working solution was required. An adequate volume of the dye working solution was added to the EC-Exos, which were subsequently mixed using vortexing for 1 minute and incubated in the dark for 15 minutes. Following this, the PKH26-labeled EC-Exos were purified via ultracentrifugation to eliminate any excess dye. The PKH26-labeled EC-Exos were introduced into the culture wells and cocultured with the cells for 6 hours. After this incubation period, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were rinsed with PBS for 5 minutes, which was repeated twice. After washing with PBS, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole solution was applied, and the cells were allowed to incubate at room temperature for a further 5 minutes. Post-incubation, the cells underwent a final wash with PBS for 5 minutes, which was repeated twice. The cells were examined and photographed using a fluorescence microscope, and the acquired images were saved for further analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from the HG and HG + EC-Exos groups utilizing TRIzol reagent, followed by comprehensive high-throughput sequencing analyses to assess mRNA and miR profiles. A threshold of |log2-fold change| ≥ 1 was established for identifying significant alterations, accompanied by q < 0.05 (where q represents adjusted P value) for the selection of differentially expressed genes. Differentially expressed genes were analyzed through Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes enrichment analyses within designated comparison groups. Additionally, the identification of key miR-targeting mRNAs was performed, integrating this with ferroptosis enrichment analysis related to the miR target genes.

The 10 miRs that exhibited significant upregulation in the HG + EC-Exos group relative to the HG group were chosen for further validation. Total RNA was isolated from samples of the HG and HG + EC-Exos groups. Following this, the RNA underwent reverse transcription to synthesize complementary DNA. Detection was performed utilizing a SYBR Green quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit (Biosharp, Hefei, China). Primer details are pro

The wild-type PTGS2 luciferase reporter plasmid was constructed by cloning the 3’-untranslated region (UTR) of PTGS2, containing the predicted miR-335-3p binding site (5’-ATGAAAAATG-3’), into the pEZX-MT06 vector (Gene Copoeia, Anhui, China). Subsequently, the 3’ UTR of PTGS2 featuring a mutated miR-335-3p binding site was also cloned and in

The cells were transfected with the mmu-miR-335-3p inhibitor, mmu-miR-335-3p negative control (NC, General Bio, Anhui, China) (for the oligonucleotide sequences, see Supplementary Table 2). MC3T3E1 cells were seeded into six-well plates (106 cells per well) and cultured at 37 °C until they reached 80%-90% confluence. MC3T3E1 cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 25 mmol/L glucose for 48 hour and transfected with the above vectors by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United Staates).

MC3T3E1 cells were divided into control, HG, HG + Exos, HG + Exos + NC, and HG + Exos + inhibitor groups. The control group was cultured for 48 hours at a glucose concentration of 5.5 mmol/L; the HG group was cultured for 48 hours at a glucose concentration of 25 mmol/L; the HG + Exos group was cocultured with 20 μL Exos for 6 hours under HG conditions; the HG + Exos + NC group was transfected with NC sequences in cells cultured with a glucose concentration of 25 mmol/L for 48 hours and then cocultured with 20 μL Exos for 6 hours; and the HG + Exos + inhibitor group was transfected with mmu-miR-335-3p inhibitor sequences in cells cultured with a glucose concentration of 25 mmol/L for 48 hours and then cocultured with 20 μL Exos for 6 hours. Exosomal protein content was determined with a BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, Unites States), and a standardized dose of 5 μg per treatment was applied to ensure efficient cellular uptake.

The overall concentration of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) was evaluated utilizing a ROS Assay Kit (Beyotime, Nantong, China). After incubation, cells from each group were collected and diluted with 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) at a 1:1000 ratio to a final concentration of 10 μmol/L. The cells were then resuspended in the diluted DCFH-DA solution at a density of 105 cells/mL and incubated at 37 °C for 20 minutes. To ensure optimal interaction between the probe and the cells, the mixture was agitated every 3-5 minutes. Following incubation, the cells were washed three times with serum-free cell culture medium to eliminate any unincorporated DCFH-DA. The fluo

Cells were harvested following the protocol outlined in the malondialdehyde (MDA) assay kit (Biyun, Nantong, China). The cells were homogenized in a buffer or lysis solution at specified ratios, thoroughly mixed, and incubated on ice for 10 minutes to facilitate lysis. The resulting homogenate was subjected to centrifugation at 15000 × g for 10 minutes, allowing for collection of the supernatants for subsequent analysis. MDA concentrations were quantified utilizing a sensitive assay kit (Biyun, Nantong, China). Samples in 96-well plates were incubated with working solution at 37 °C for designated durations. Absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically, and MDA levels were quantified according to the reagent protocol.

Cells from each group were digested and pelleted by centrifugation at 10000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C according to the protocol of the GSH assay kit (BiYuntian, Nantong, China). Subsequent to sonication, a 10-μL aliquot of the cell su

Total RNA was isolated from cellular samples or Exos utilizing TRI Reagent (Biosharp, Hefei, China), followed by quantification and assessment of RNA quality via spectrophotometry. Subsequently, 2 μg extracted total RNA was used to synthesize high-quality complementary DNA with amplification conducted using the Prime Script RT Master Mix Kit (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). For reverse transcription-quantitative PCR, the SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (Biosharp, Hefei, China) was utilized. The thermal cycling protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 seconds and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 30 seconds. Glyceraldehyde 3-pho

Each cell group or exosomal sample was subjected to lysis utilizing radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer for the extraction of total protein. Following this, centrifugation was conducted at 12000 × g for 15 minutes at 4 °C to isolate the supernatant, which contained the total protein. After denaturation, the proteins were separated by electrophoresis and transferred onto a membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C with specific primary antibodies (Zhongshan Jinqiao, Beijing, China) against GAPDH, PTGS2, GPX4, solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2), as well as the exosomal markers CD63 and CD81, all at a dilution of 1:1000. Thereafter, the membrane was incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Zhongshan Jinqiao, Beijing, China) diluted at 1:5000 for 1 hour at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using a Western ECL substrate kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, United States). Images were acquired with a Bio-Rad scanner (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, United States) and quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ software (Version 1.53k, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States). GAPDH was used as an internal reference to evaluate the expression levels of PTGS2, GPX4, SLC7A11, SLC3A2, CD63, and CD81.

Data were collected from 32 female patients with T2DM and DOP who were treated at the Second Affiliated Hospital and the First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical University from January 2023 to December 2023 (DOP group). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) T2DM meeting the diagnostic criteria of the “Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes (2020 Edition)”[15]; (2) Osteoporosis diagnosed according to the “Primary Osteoporosis Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines (2017)”[16], with a bone density T-score ≤ -2.5; (3) Aged ≥ 55 years and naturally postmenopausal; and (4) No history of fractures or antiosteoporosis treatment. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Secondary osteoporosis due to other causes; (2) Other severe underlying diseases; (3) Acute or chronic infection; (4) Long-term use of anticoagulants, sex hormones, or other drugs with adverse effects on bone; (5) Incomplete data; (6) Acute complications of diabetes; and (7) Diseases affecting bone metabolism, such as Cushing’s syndrome. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bengbu Medical College. Additionally, 30 patients with T2DM during the same period comprised the T2DM group. The general clinical data of both groups were collected, and serum miR-335-3p expression was determined by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR, and serum PTGS2 levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Fasting venous blood (6 mL) was drawn from both groups and centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C to remove impurities, and the supernatant was collected and stored at 80 °C. 2 mL of serum was used for determination of PTGS2 levels by ELISA (Tiande Biotechnology, Wuhan, China).

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, United States) for analysis of three independent experiments. Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as the mean ± SD; non-normal variables are reported as median (interquartile range). Comparisons between two groups and among multiple groups for continuous variables were made with Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s test. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. The efficacy of serum miR-335-3p in predicting fractures was determined by ROC curves. Multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze the factors affecting DOP.

The Exos obtained in this investigation exhibited a cup-like morphology under electron microscopy (Figure 1). Nanoparticle tracking analysis revealed Exos with a size distribution of 74-193 nm, a peak at 82 nm, and a mean size of 114.6 ± 57.3 nm (Figure 1). Fluorescence microscopy indicated that after 6 hours coculture with PKH26-labeled Exos, significant accumulation of red fluorescence was observed within the osteoblast membrane and cytoplasm (Figure 1). These findings suggest that PKH26-labeled Exos are capable of being internalized by osteoblasts, thereby facilitating intercellular communication. The presence of characteristic exosomal markers, CD63 and CD81, was confirmed by western blotting (Figure 1).

In comparison to the control group, the HG group showed increases in ROS and MDA levels, alongside significant reductions in GSH levels (P < 0.05). Conversely, the HG + EC-Exos group demonstrated markedly lower levels of ROS and MDA, as well as significantly higher levels of GSH when compared to the HG group (P < 0.05; Figure 2A-D). The HG group showed an increase in PTGS2 mRNA expression, coupled with a significant decline in expression of SLC3A2, SLC7A11, and GPX4 compared to the control group (P < 0.05). In contrast, the HG + EC-Exos group exhibited reduced PTGS2 mRNA levels and significant upregulation of mRNA expression of SLC3A2, SLC7A11, and GPX4 relative to the HG group (P < 0.05; Figure 2E).

High-throughput sequencing indicated that, in contrast to the HG group, the HG + EC-Exos group had 54 downregulated miRs and 40 upregulated miRs (Figure 3). Following filtering of expression abundance, the 10 most significantly up

In the comparative analysis between the HG + EC-Exos and HG groups, upregulation of specific miRs was observed, including miR-6538, miR-6240, miR-5126, miR-210-3p, miR-126a-5p, miR-335-3p, miR-6239, miR-677-3p, miR-702-3p, and miR-5099 (Figure 3). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis indicated the involvement of ferroptosis (Figure 3), while protein interaction analysis revealed that miR-335-3p had the potential to target PTGS2 (Figure 3). To ascertain the origins of miR-335-3p in Exos, we examined the variations in miR-335-3p levels in the EC-Exos, HG, and HG + EC-Exos groups. The concentration of miR-335-3p was significantly diminished in the EC-Exos group compared to the HG group (P < 0.05). Conversely, the levels of miR-335-3p were markedly elevated in the HG + EC-Exos group relative to the HG group (P < 0.05; Figure 3).

Our predictions indicated that miR-335-3p could interact with the 321-328 region of the PTGS2 3’ UTR (Figure 4A). To confirm this interaction, we performed a dual-luciferase reporter assay. The observed dual-luciferase activity ratio resulting from cotransfection of mmu-miR-335-3p with PTGS2-3’ UTR-wild-type was markedly reduced compared to that in the control group (P < 0.05). In contrast, the dual-luciferase activity ratio when mmu-miR-335-3p was cotransfected with PTGS2-3’ UTR-mutant showed no significant difference when compared to the control group (P > 0.05; Figure 4B). These findings imply that mmu-miR-335-3p is capable of targeting PTGS2.

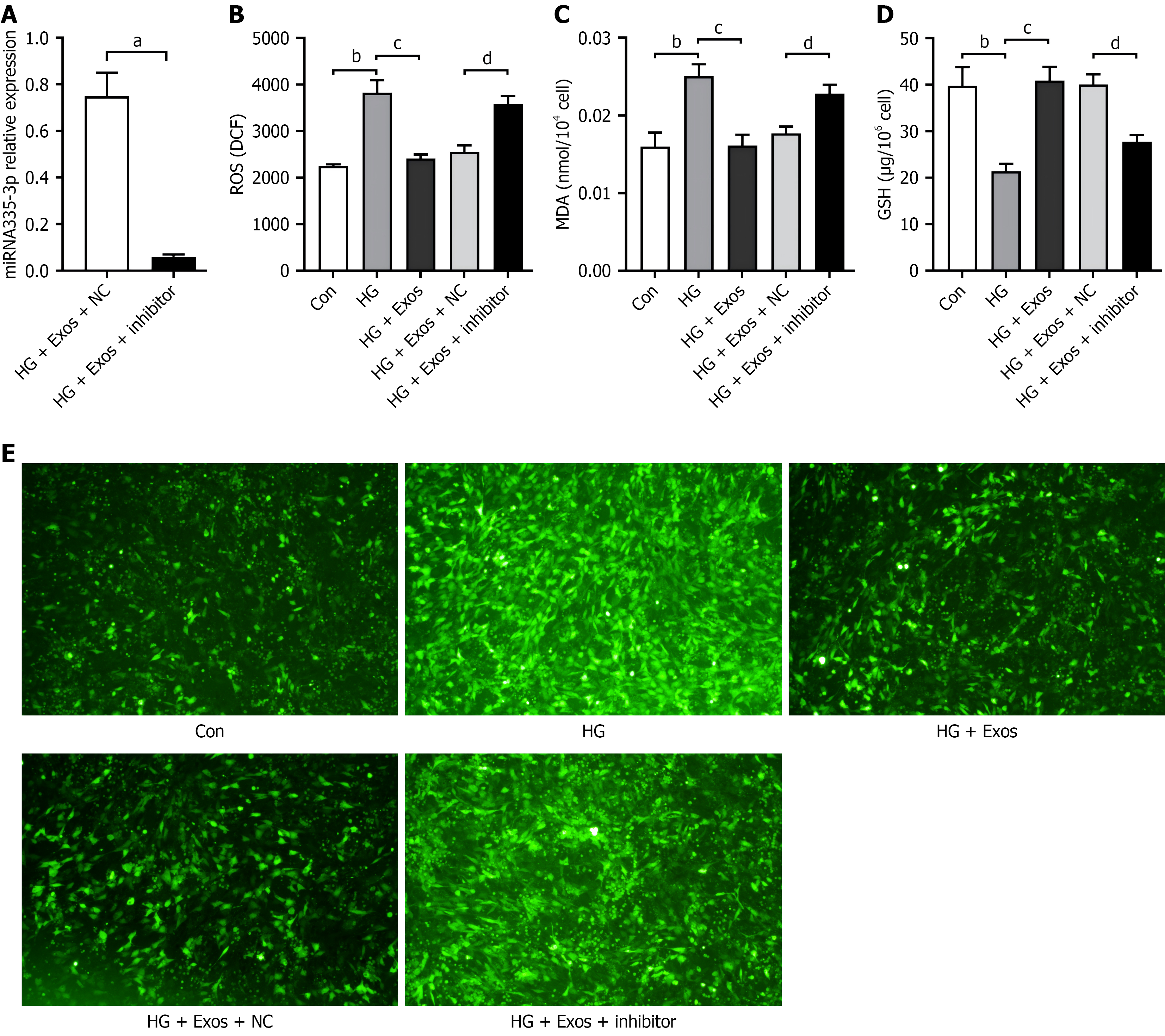

To evaluate the impact of miR-335-3p on osteoblast impairment induced by HG, a miR-335-3p inhibitor was introduced into HG-treated osteoblasts, leading to a notable reduction in miR-335-3p expression levels (Figure 5A). The concentrations of ROS and MDA were markedly elevated in the HG group compared to the control group (P < 0.01), while GSH levels were significantly decreased (P < 0.01). In contrast, the HG + Exos group exhibited significantly reduced levels of ROS and MDA, alongside a substantial increase in GSH levels compared to the HG group (P < 0.01). When comparing the HG + Exos + inhibitor group to the HG + Exos+ NC group, there was a significant increase in ROS and MDA levels, coupled with a marked decrease in GSH levels (P < 0.01; Figure 5B-E).

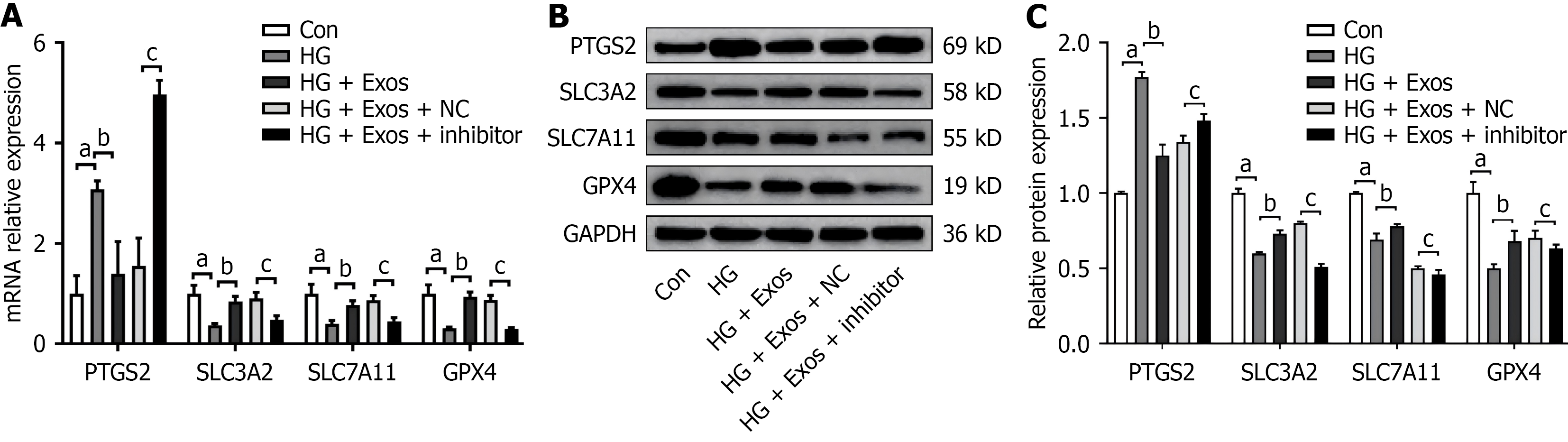

In comparison to the control group, the HG group exhibited significant elevations in mRNA and protein expression of PTGS2, alongside notable reductions in mRNA and protein expression of GPX4, SLC7A11, and SLC3A2 (P < 0.01). Conversely, compared to the HG group, the HG + Exos group showed decreased PTGS2 but increased GPX4, SLC7A11, and SLC3A2 expression at both mRNA and protein levels (P < 0.01). Following knockdown of miR-335-3p, the HG + Exos + inhibitor group showed an increase in mRNA and protein expression of PTGS2, along with a decrease in mRNA and protein expressions of GPX4, SLC7A11, and SLC3A2, compared to the HG + Exos + NC group (P < 0.01; Figure 6A-C).

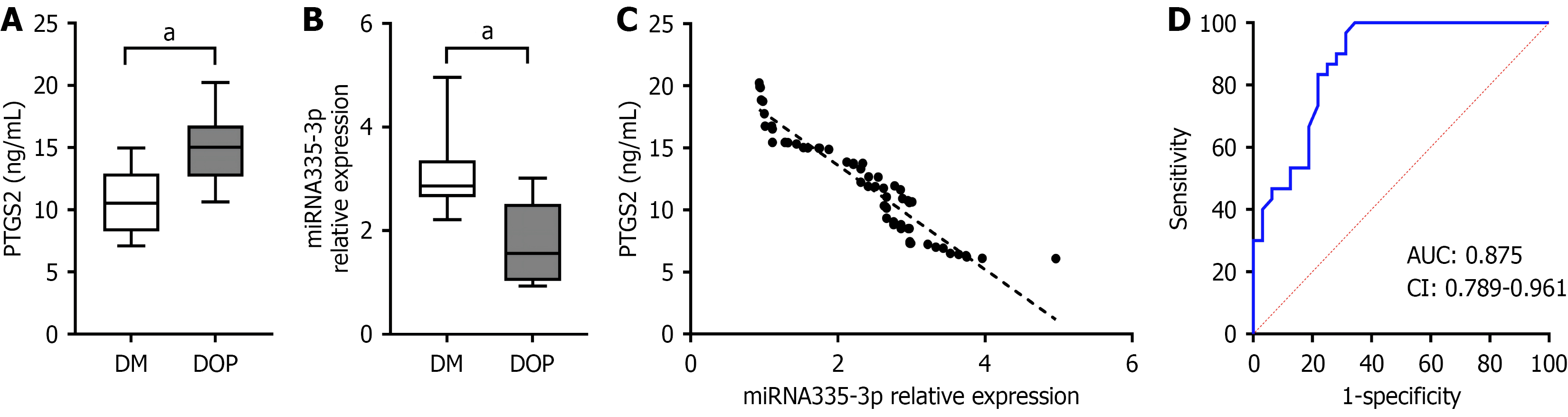

We conducted validations at the clinical level. To avoid the impact of sex on osteoporosis, we selected female patients with T2DM and DOP (comparisons of the clinical data are shown in Table 1). Variables that were significantly associated with DOP in the univariate analyses (P < 0.05), including age, body mass index, and fasting C-peptide, were then entered into a multivariable logistic regression model. Logistic regression analysis suggested that the influencing factors for DOP were miR-335-3p, body mass index, and fasting C-peptide (Table 2). Serum PTGS2 levels were significantly higher in the DOP group than in the T2DM group (P < 0.05), whereas miR-335-3p expression was notably lower in DOP group compared to T2DM group (P < 0.05; Figure 7A and B). In the DOP and T2DM groups, serum miR-335-3p levels were negatively correlated with PTGS2 levels, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.954 (Figure 7C). The ROC curve for miR-335-3p was plotted, with an area under the curve of 0.875, which indicated a certain diagnostic significance (Figure 7D).

| Group | n | Age (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Fasting C-peptide (ng/mL) | FBG (mmol/L) | HbA1c (%) | MicroRNA335-3p | PTGS2 (ng/mL) |

| DM | 32 | 56.63 ± 8.42 | 24.36 ± 1.91 | 2.29 ± 1.21 | 9.26 ± 1.78 | 9.19 ± 1.13 | 2.86 (2.25, 3.36) | 10.52 (8.25, 12.91) |

| DOP | 30 | 65.40 ± 8.60 | 21.12 ± 1.52 | 1.29 ± 0.59 | 10.75 ± 2.23 | 10.28 ± 2.28 | 1.56 (1.03, 2.52) | 15.03 (12.66, 16.77) |

| Z/t | 4.06a | -7.44a | -4.10a | 2.88a | 2.62a | -5.072a | -5.163a |

The mechanism by which diabetes leads to osteoporosis is largely unclear, but oxidative stress caused by high blood glucose is currently considered an important factor. Oxidative stress promotes the release of ROS, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, which in turn leads to bone tissue cell death[17]. Ferroptosis represents a novel form of programmed cell death, which is identified by an accumulation of iron and lipid peroxidation that is reliant on ROS[18]. Biochemically, ferroptosis is characterized primarily by lipid peroxidation, which is often accompanied by iron overload, excessively high levels of ROS, and reduced activity of antioxidant enzymes[19]. Among these, the cystine/glutamate antiporter (also known as System Xc-)/GSH/GPX4 system plays a crucial role as an antioxidant regulatory pathway in the process of ferroptosis. This system comprises transporter protein SLC7A11 and regulatory protein SLC3A2, which facilitate the exchange of intracellular glutamate for extracellular cysteine. GPX4 is capable of utilizing GSH as a cofactor to convert phospholipid hydroperoxides into their corresponding alcohols[19]. In a mouse model of T2DM-induced osteoporosis, ferroptosis caused by disorders of glucose and lipid metabolism was verified. In DOP mice, serum ferritin levels were significantly elevated, while SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression in bone tissue was markedly reduced. These mice also displayed pronounced trabecular bone deterioration and bone loss, consistent with decreased GPX4 and elevated PTGS2 expression[20]. Our research corroborated these findings, demonstrating that in osteoblasts cultured under HG conditions, expression of PTGS2 was elevated. Additionally, the level of MDA, a byproduct of lipid peroxidation, was increased, whereas the level of ROS was significantly increased. Conversely, GSH levels were decreased. Key ferroptosis-related markers, including SLC7A11, SLC3A2, and GPX4, showed significantly decreased expression.

PTGS2, also known as cyclooxygenase 2, is an enzyme that accelerates lipid peroxidation and is an early direct product of inflammation. Recent research has suggested that PTGS2 could be a key ferroptosis gene in diabetic retinopathy and diabetic nephropathy[21]. PTGS2 promotes the maturation of osteoclasts through prostaglandin E2, thereby facilitating the occurrence of osteoporosis[22]. Recent research has demonstrated that PTGS2 plays a crucial role in the mechanism underlying femoral head necrosis[23]. In our study, we observed that serum levels of PTGS2 in individuals diagnosed with DOP were markedly elevated compared to those in patients with T2DM alone. This finding aligns with previous investigations, indicating the significant involvement of PTGS2 in DOP pathology. Considering the role of PTGS2 in both diabetes and disorders related to bone metabolism, it is plausible that ferroptosis may serve as a shared mechanism un

Research suggests that Exos are important effector molecules and carriers for intercellular material exchange and information transmission, regulating the cellular microenvironment and participating in various biological processes of target cells, such as promoting angiogenesis and anti-immunogenicity, inhibiting cell apoptosis, and affecting tumor cell proliferation, antifibrosis, and various anti-inflammatory processes[24-26]. Recent evidence suggests that Exos may not only facilitate intercellular communication but also modulate ferroptosis in recipient cells, highlighting their potential as a novel therapeutic strategy[27]. Blood vessels are crucial for bone formation, with endothelial cells lining their inner sur

In diabetes-related research, miR-335-3p has been shown to improve insulin resistance by affecting macrophage polarization[29] and play a role in protecting islet function[30]. In patients with diabetic retinopathy, the level of miR-335-3p in plasma is significantly reduced[31]. In bone and joint diseases, in advanced knee osteoarthritis, miR-335-3p might be a regulatory gene target in the infrapatellar fat[32]. In the nucleus pulposus and blood of patients with lumbar disc de

Although this study indicated that EC-Exos had therapeutic effects on HG-induced osteoporosis, the exosomal components involved in this effect have not yet been identified. Exos contain a large number of functional proteins, mRNAs, long noncoding RNAs, and miRs, which can be taken up and internalized by osteoblasts to regulate trans

EC-Exos affect ferroptosis in osteoblasts induced by HG by activating miR-335-3p/PTGS2. Serum miR-335-3p may be a novel diagnostic biomarker.

| 1. | Chen Y, Zhao W, Hu A, Lin S, Chen P, Yang B, Fan Z, Qi J, Zhang W, Gao H, Yu X, Chen H, Chen L, Wang H. Type 2 diabetic mellitus related osteoporosis: focusing on ferroptosis. J Transl Med. 2024;22:409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shanbhogue VV, Hansen S, Frost M, Brixen K, Hermann AP. Bone disease in diabetes: another manifestation of microvascular disease? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:827-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lin Y, Shen X, Ke Y, Lan C, Chen X, Liang B, Zhang Y, Yan S. Activation of osteoblast ferroptosis via the METTL3/ASK1-p38 signaling pathway in high glucose and high fat (HGHF)-induced diabetic bone loss. FASEB J. 2022;36:e22147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang X, Ma H, Sun J, Zheng T, Zhao P, Li H, Yang M. Mitochondrial Ferritin Deficiency Promotes Osteoblastic Ferroptosis Via Mitophagy in Type 2 Diabetic Osteoporosis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2022;200:298-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hadian K, Stockwell BR. SnapShot: Ferroptosis. Cell. 2020;181:1188-1188.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 50.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee H, Zandkarimi F, Zhang Y, Meena JK, Kim J, Zhuang L, Tyagi S, Ma L, Westbrook TF, Steinberg GR, Nakada D, Stockwell BR, Gan B. Energy-stress-mediated AMPK activation inhibits ferroptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22:225-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 862] [Article Influence: 143.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367:eaau6977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6920] [Cited by in RCA: 7524] [Article Influence: 1254.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 8. | Song H, Li X, Zhao Z, Qian J, Wang Y, Cui J, Weng W, Cao L, Chen X, Hu Y, Su J. Reversal of Osteoporotic Activity by Endothelial Cell-Secreted Bone Targeting and Biocompatible Exosomes. Nano Lett. 2019;19:3040-3048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yang RZ, Xu WN, Zheng HL, Zheng XF, Li B, Jiang LS, Jiang SD. Exosomes derived from vascular endothelial cells antagonize glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis by inhibiting ferritinophagy with resultant limited ferroptosis of osteoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236:6691-6705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Grillari J, Mäkitie RE, Kocijan R, Haschka J, Vázquez DC, Semmelrock E, Hackl M. Circulating miRNAs in bone health and disease. Bone. 2021;145:115787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang Y, Wang K, Hu Z, Zhou H, Zhang L, Wang H, Li G, Zhang S, Cao X, Shi F. MicroRNA-139-3p regulates osteoblast differentiation and apoptosis by targeting ELK1 and interacting with long noncoding RNA ODSM. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Miao M, Zhang Y, Wang X, Lei S, Huang X, Qin L, Shou D. The miRNA-144-5p/IRS1/AKT axis regulates the migration, proliferation, and mineralization of osteoblasts: A mechanism of bone repair in diabetic osteoporosis. Cell Biol Int. 2022;46:2220-2231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang C, Liu X, Zhao K, Zhu Y, Hu B, Zhou Y, Wang M, Wu Y, Zhang C, Xu J, Ning Y, Zou D. miRNA-21 promotes osteogenesis via the PTEN/PI3K/Akt/HIF-1α pathway and enhances bone regeneration in critical size defects. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, Ayre DC, Bach JM, Bachurski D, Baharvand H, Balaj L, Baldacchino S, Bauer NN, Baxter AA, Bebawy M, Beckham C, Bedina Zavec A, Benmoussa A, Berardi AC, Bergese P, Bielska E, Blenkiron C, Bobis-Wozowicz S, Boilard E, Boireau W, Bongiovanni A, Borràs FE, Bosch S, Boulanger CM, Breakefield X, Breglio AM, Brennan MÁ, Brigstock DR, Brisson A, Broekman ML, Bromberg JF, Bryl-Górecka P, Buch S, Buck AH, Burger D, Busatto S, Buschmann D, Bussolati B, Buzás EI, Byrd JB, Camussi G, Carter DR, Caruso S, Chamley LW, Chang YT, Chen C, Chen S, Cheng L, Chin AR, Clayton A, Clerici SP, Cocks A, Cocucci E, Coffey RJ, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, Couch Y, Coumans FA, Coyle B, Crescitelli R, Criado MF, D'Souza-Schorey C, Das S, Datta Chaudhuri A, de Candia P, De Santana EF, De Wever O, Del Portillo HA, Demaret T, Deville S, Devitt A, Dhondt B, Di Vizio D, Dieterich LC, Dolo V, Dominguez Rubio AP, Dominici M, Dourado MR, Driedonks TA, Duarte FV, Duncan HM, Eichenberger RM, Ekström K, El Andaloussi S, Elie-Caille C, Erdbrügger U, Falcón-Pérez JM, Fatima F, Fish JE, Flores-Bellver M, Försönits A, Frelet-Barrand A, Fricke F, Fuhrmann G, Gabrielsson S, Gámez-Valero A, Gardiner C, Gärtner K, Gaudin R, Gho YS, Giebel B, Gilbert C, Gimona M, Giusti I, Goberdhan DC, Görgens A, Gorski SM, Greening DW, Gross JC, Gualerzi A, Gupta GN, Gustafson D, Handberg A, Haraszti RA, Harrison P, Hegyesi H, Hendrix A, Hill AF, Hochberg FH, Hoffmann KF, Holder B, Holthofer H, Hosseinkhani B, Hu G, Huang Y, Huber V, Hunt S, Ibrahim AG, Ikezu T, Inal JM, Isin M, Ivanova A, Jackson HK, Jacobsen S, Jay SM, Jayachandran M, Jenster G, Jiang L, Johnson SM, Jones JC, Jong A, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Jung S, Kalluri R, Kano SI, Kaur S, Kawamura Y, Keller ET, Khamari D, Khomyakova E, Khvorova A, Kierulf P, Kim KP, Kislinger T, Klingeborn M, Klinke DJ 2nd, Kornek M, Kosanović MM, Kovács ÁF, Krämer-Albers EM, Krasemann S, Krause M, Kurochkin IV, Kusuma GD, Kuypers S, Laitinen S, Langevin SM, Languino LR, Lannigan J, Lässer C, Laurent LC, Lavieu G, Lázaro-Ibáñez E, Le Lay S, Lee MS, Lee YXF, Lemos DS, Lenassi M, Leszczynska A, Li IT, Liao K, Libregts SF, Ligeti E, Lim R, Lim SK, Linē A, Linnemannstöns K, Llorente A, Lombard CA, Lorenowicz MJ, Lörincz ÁM, Lötvall J, Lovett J, Lowry MC, Loyer X, Lu Q, Lukomska B, Lunavat TR, Maas SL, Malhi H, Marcilla A, Mariani J, Mariscal J, Martens-Uzunova ES, Martin-Jaular L, Martinez MC, Martins VR, Mathieu M, Mathivanan S, Maugeri M, McGinnis LK, McVey MJ, Meckes DG Jr, Meehan KL, Mertens I, Minciacchi VR, Möller A, Møller Jørgensen M, Morales-Kastresana A, Morhayim J, Mullier F, Muraca M, Musante L, Mussack V, Muth DC, Myburgh KH, Najrana T, Nawaz M, Nazarenko I, Nejsum P, Neri C, Neri T, Nieuwland R, Nimrichter L, Nolan JP, Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Noren Hooten N, O'Driscoll L, O'Grady T, O'Loghlen A, Ochiya T, Olivier M, Ortiz A, Ortiz LA, Osteikoetxea X, Østergaard O, Ostrowski M, Park J, Pegtel DM, Peinado H, Perut F, Pfaffl MW, Phinney DG, Pieters BC, Pink RC, Pisetsky DS, Pogge von Strandmann E, Polakovicova I, Poon IK, Powell BH, Prada I, Pulliam L, Quesenberry P, Radeghieri A, Raffai RL, Raimondo S, Rak J, Ramirez MI, Raposo G, Rayyan MS, Regev-Rudzki N, Ricklefs FL, Robbins PD, Roberts DD, Rodrigues SC, Rohde E, Rome S, Rouschop KM, Rughetti A, Russell AE, Saá P, Sahoo S, Salas-Huenuleo E, Sánchez C, Saugstad JA, Saul MJ, Schiffelers RM, Schneider R, Schøyen TH, Scott A, Shahaj E, Sharma S, Shatnyeva O, Shekari F, Shelke GV, Shetty AK, Shiba K, Siljander PR, Silva AM, Skowronek A, Snyder OL 2nd, Soares RP, Sódar BW, Soekmadji C, Sotillo J, Stahl PD, Stoorvogel W, Stott SL, Strasser EF, Swift S, Tahara H, Tewari M, Timms K, Tiwari S, Tixeira R, Tkach M, Toh WS, Tomasini R, Torrecilhas AC, Tosar JP, Toxavidis V, Urbanelli L, Vader P, van Balkom BW, van der Grein SG, Van Deun J, van Herwijnen MJ, Van Keuren-Jensen K, van Niel G, van Royen ME, van Wijnen AJ, Vasconcelos MH, Vechetti IJ Jr, Veit TD, Vella LJ, Velot É, Verweij FJ, Vestad B, Viñas JL, Visnovitz T, Vukman KV, Wahlgren J, Watson DC, Wauben MH, Weaver A, Webber JP, Weber V, Wehman AM, Weiss DJ, Welsh JA, Wendt S, Wheelock AM, Wiener Z, Witte L, Wolfram J, Xagorari A, Xander P, Xu J, Yan X, Yáñez-Mó M, Yin H, Yuana Y, Zappulli V, Zarubova J, Žėkas V, Zhang JY, Zhao Z, Zheng L, Zheutlin AR, Zickler AM, Zimmermann P, Zivkovic AM, Zocco D, Zuba-Surma EK. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6453] [Cited by in RCA: 8271] [Article Influence: 1033.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Chinese Medical Association Diabetes Mellitus Branch. [Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes (2020 Edition)]. Zhonghua Neifenmi Daixie Zazhi. 2021;37:311-398. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Chinese Medical Association Society of Osteoporosis and Bone Mineral Research. [Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary osteoporosis (2017)]. Zhonghua Neifenmi Daixie Zazhi. 2017;33:890-913. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Shackelford RE, Kaufmann WK, Paules RS. Oxidative stress and cell cycle checkpoint function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1387-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mou Y, Wang J, Wu J, He D, Zhang C, Duan C, Li B. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: opportunities and challenges in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 1395] [Article Influence: 199.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:266-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2184] [Cited by in RCA: 5296] [Article Influence: 1059.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang Y, Lin Y, Wang M, Yuan K, Wang Q, Mu P, Du J, Yu Z, Yang S, Huang K, Wang Y, Li H, Tang T. Targeting ferroptosis suppresses osteocyte glucolipotoxicity and alleviates diabetic osteoporosis. Bone Res. 2022;10:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wu Z, Li D, Tian D, Liu X, Wu Z. Aspirin mediates protection from diabetic kidney disease by inducing ferroptosis inhibition. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0279010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lu LY, Loi F, Nathan K, Lin TH, Pajarinen J, Gibon E, Nabeshima A, Cordova L, Jämsen E, Yao Z, Goodman SB. Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages promote Osteogenesis by mesenchymal stem cells via the COX-2-prostaglandin E2 pathway. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:2378-2385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang X, Meng H, Shou Z, Zhou H, Chen L, Yu J, Hu K, Bai Z, Chen C. Machine learning-mediated identification of ferroptosis-related genes in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. FEBS Open Bio. 2024;14:455-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tavasolian F, Hosseini AZ, Rashidi M, Soudi S, Abdollahi E, Momtazi-Borojeni AA, Sathyapalan T, Sahebkar A. The Impact of Immune Cell-derived Exosomes on Immune Response Initiation and Immune System Function. Curr Pharm Des. 2021;27:197-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ye M, Ni Q, Qi H, Qian X, Chen J, Guo X, Li M, Zhao Y, Xue G, Deng H, Zhang L. Exosomes Derived from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells-Endothelia Cells Promotes Postnatal Angiogenesis in Mice Bearing Ischemic Limbs. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:158-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Palazzolo S, Memeo L, Hadla M, Duzagac F, Steffan A, Perin T, Canzonieri V, Tuccinardi T, Caligiuri I, Rizzolio F. Cancer Extracellular Vesicles: Next-Generation Diagnostic and Drug Delivery Nanotools. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:3165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang W, Zhu L, Li H, Ren W, Zhuo R, Feng C, He Y, Hu Y, Ye C. Alveolar macrophage-derived exosomal tRF-22-8BWS7K092 activates Hippo signaling pathway to induce ferroptosis in acute lung injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;107:108690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sheng C, Guo X, Wan Z, Bai X, Liu H, Zhang X, Zhang P, Liu Y, Li W, Zhou Y, Lv L. Exosomes derived from human adipose-derived stem cells ameliorate osteoporosis through miR-335-3p/Aplnr axis. Nano Res. 2022;15:9135-9148. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Ju Z, Cui F, Mao Z, Li Z, Yi X, Zhou J, Cao J, Li X, Qian Z. miR-335-3p improves type II diabetes mellitus by IGF-1 regulating macrophage polarization. Open Med (Wars). 2024;19:20240912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Qian Z, Cui F, Mao Z, Li Z, Yi X, Zhou J, Cao J, Li X. LINC-p21 Regulates Pancreatic β-Cell Function in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biochem Genet. 2025;63:2925-2945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Xia Z, Yang X, Zheng Y, Yi G, Wu S. Plasma Levels and Diagnostic Significance of miR-335-3p and EGFR in Diabetic Retinopathy. Clin Lab. 2022;68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wilson TG, Baghel M, Kaur N, Moutzouros V, Davis J, Ali SA. Characterization of miR-335-5p and miR-335-3p in human osteoarthritic tissues. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25:105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yu L, Hao Y, Xu C, Zhu G, Cai Y. LINC00969 promotes the degeneration of intervertebral disk by sponging miR-335-3p and regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. IUBMB Life. 2019;71:611-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Huai Y, Zhang W, Chen Z, Zhao F, Wang W, Dang K, Xue K, Gao Y, Jiang S, Miao Z, Li M, Hao Q, Chen C, Qian A. A Comprehensive Analysis of MicroRNAs in Human Osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:516213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/