Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.113238

Revised: October 10, 2025

Accepted: November 18, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 117 Days and 0.7 Hours

Only a few cases of diabetes mellitus with concurrent mutations in the mito

A 30-year-old man, diagnosed with diabetic ketoacidosis six years earlier, presented with poor response to insulin therapy (glycated hemoglobin, 15.35%), marked wasting (body mass index: 15.06 kg/m2), sensorineural deafness, diabetic retinopathy, and peripheral neuropathy. Whole-exome sequencing revealed concurrent mutations: Mitochondrial MT-TL1 m.3243A>G (heteroplasmy 41.76%) and CEL c.1336G>A. Family investigation identified his mother, who also had diabetes, as a carrier of the CEL mutation, and his sister as harboring both mutations without diabetes.

This case highlights the genetic heterogeneity of monogenic diabetes and expands the known mutational spectrum. Comprehensive genetic testing is recommended to enhance diagnostic accuracy in cases of suspected monogenic diabetes.

Core Tip: This case report describes a young man with diabetes mellitus attributable to concurrent mutations in the mitochondrial MT-TL1 gene (m.3243A>G) and the CEL gene (c.1336G>A). The patient exhibited atypical features, including diabetic keto

- Citation: Che XD, Wei ZL, Gong W, Qin L, Liu S, Jin YH, Wang HY. Clinical and genetic characteristics of young-onset diabetes with concurrent mitochondrial m.3243A>G and CEL gene mutations: A case report. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(12): 113238

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i12/113238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.113238

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a distinct subtype of diabetes caused by monogenic mutations. It accounts for 1%-5% of all diabetes cases, and at least 14 causative gene mutations have been identified to date. The most common subtypes are MODY3, caused by mutations in the HNF1A gene, and MODY2, caused by mutations in the GCK gene[1]. Recently, MODY8, caused by mutations in the CEL1 gene, has garnered attention, typically manifesting as hyperglycemia accompanied by exocrine pancreatic dysfunction and steatorrhea[2]. Mitochondrial diabetes, another monogenic diabetes subtype caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), is most commonly attributed to the m.3243A>G mutation. It exhibits maternal inheritance and is characterized by sensorineural hearing loss, as well as multisystem involvement[3]. This mutation induces diabetes by impairing β-cell function and insulin secretion. However, its clinical manifestations often overlap with those of MODY, leading to frequent misdiagnosis as type 2 diabetes. Cases harboring mutations in both nuclear genes (e.g., CEL) and mitochondrial genes (such as m.3243A>G) are exceedingly rare. Such cases may exhibit unique phenotypes due to complex genetic interactions, posing diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Herein, we report a case of young-onset diabetes mellitus with concurrent mutations—m.3243A>G in mtDNA and c.1336G>A in CEL. The objective is to provide insights into precise typing, genetic counseling, and personalized treatment of monogenic diabetes mellitus, and to expand the body of data on rare forms of diabetes mellitus.

A 30-year-old man from northeastern China presented with a 6-year history of poly

Symptoms included bilateral blurred vision, progressive hearing loss, and numbness in both feet.

Six years earlier, he took metformin (0.5 g ter in die) for three months. Due to gastrointestinal symptoms, the medication was discontinued, and he was then diagnosed with diabetic ketoacidosis at a local hospital. Subsequently, the patient switched to insulin therapy (Humulin 30R, 8 U in the morning and 12 U in the evening). However, glycemic control remained poor, with fasting blood glucose ranging from 10 mmol/L to 20 mmol/L.

The patient had a 6-year history of diabetes and his sister was healthy. His mother was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus at 50 years old. His father died of an acute cerebral infarction at 45 years of age.

Physical examination revealed a height of 163 cm, a weight of 40 kg, and a body mass index of 15.06 kg/m2, with blood pressure at 103/80 mmHg. Notable findings included reduced skin turgor, scant subcutaneous fat, bilateral hearing impairment, and diminished pain and temperature sensation in the lower extremities.

Laboratory investigations revealed elevated fasting blood glucose (16.5 mmol/L) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c, 15.35%), with glycosuria (+++), proteinuria (1+), and negative urine ketones. Blood lactate was within the normal range [2.1 mmol/L (0.5-2.2 mmol/L)]. The whole islet autoantibody panel was negative, including insulin, GAD65, IA-2, ZnT8, and islet cell antibodies. Pancreatic islet function tests revealed severe β-cell secretory dysfunction (Table 1).

| Time (minute) | 0 | 60 | 120 | 180 | Reference range |

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | 4.45 | 10.97 | 19.06 | 20.57 | 3.9-6.1 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 0.16 | 0.47 | 1.28 | 1.81 | 1.1-4.4 |

Electromyography revealed reduced sensory nerve conduction velocities in all four extremities and slowed motor conduction velocities in the left common peroneal nerve and the right median nerve (Table 2).

| Nerve | CV | Findings | |

| SNC testing | |||

| Right median nerve | Middle finger-wrist | 41 m/s | Slowed |

| Right ulnar nerve | Little finger-wrist | 41 m/s | Slowed |

| Left median nerve | Middle finger-wrist | 44 m/s | Slowed |

| Left superficial | Calf-medial malleolus | 38 m/s | Slowed |

| Right superficial | Calf-medial malleolus | 39 m/s | Slowed |

| Right sural nerve | Lateral malleolus-sura | 43 m/s | Slowed |

| MNC testing | |||

| Right median nerve | Distal latency | 4.1 ms | Prolonged |

| Elbow-wrist CV | 46 m/s | Slowed | |

| Left common peroneal nerve | Distal latency | 3.7 ms | Normal |

| Fibular head-medial malleolus CV | 39 m/s | Slowed | |

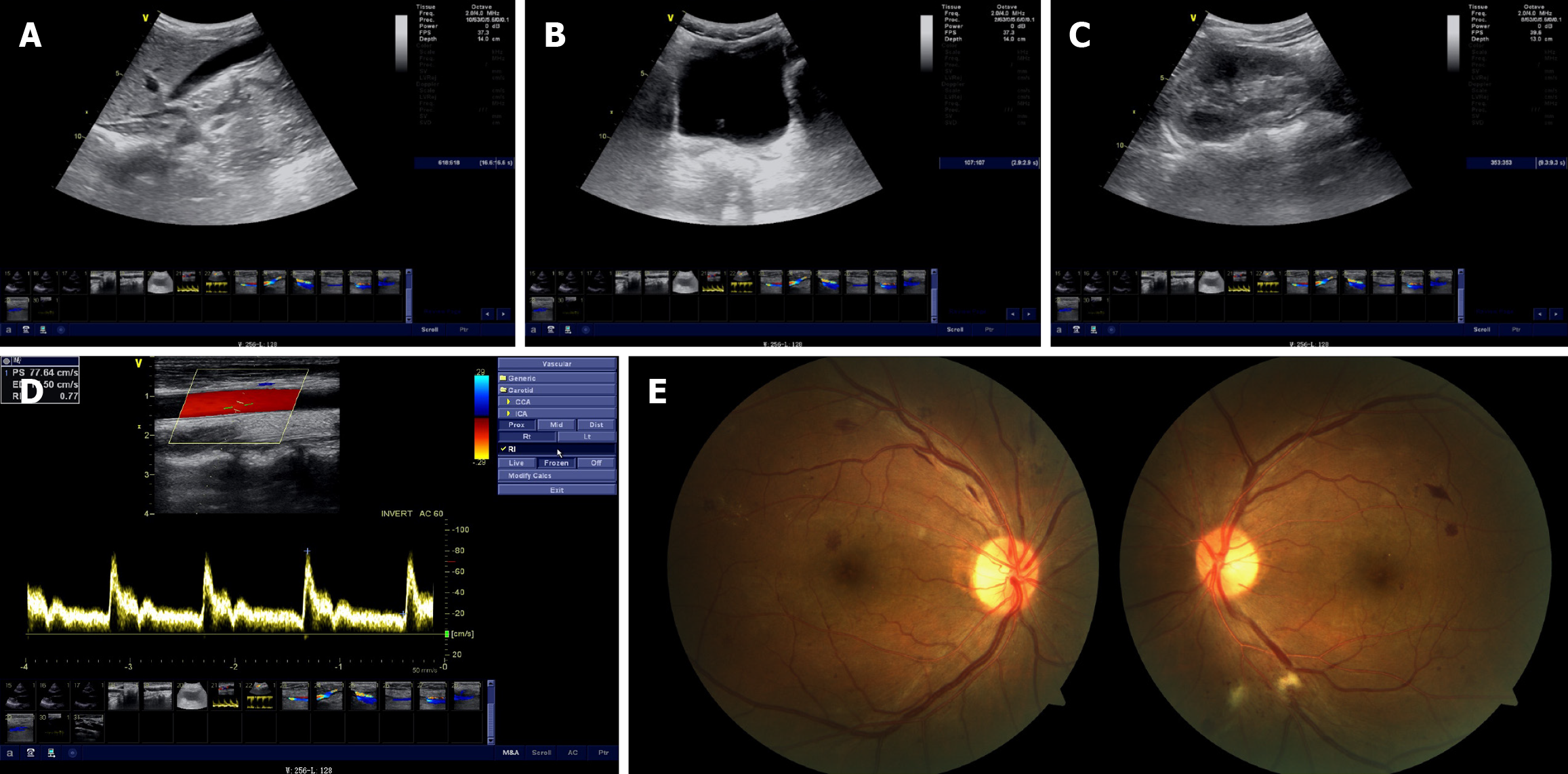

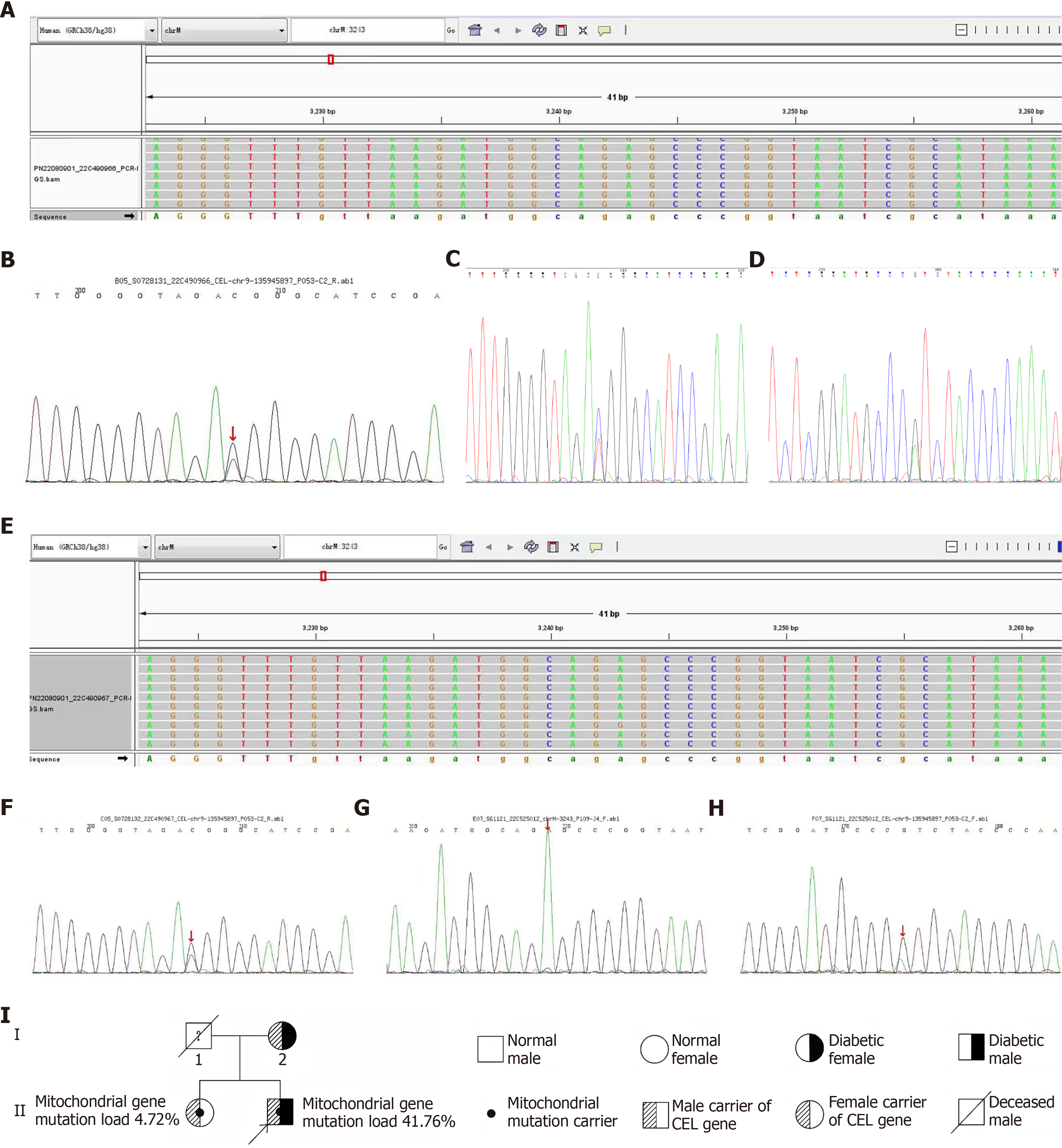

Urinary ultrasonography showed diffusely increased echogenicity of the renal parenchyma in both kidneys, suggesting chronic renal parenchymal damage (Figure 1A). Abdominal color Doppler ultrasound showed no significant abnormalities in the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, or biliary ducts (Figure 1B and C). Color Doppler ultrasound of the cervical vessels showed patent bilateral carotid arteries without significant stenosis (Figure 1D). Pure-tone audiometry demonstrated mild bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, affecting the high-frequency range above 4 kHz, without dysarthria. Fundus examination showed typical manifestations of diabetic retinopathy (Figure 1E). Whole-exome sequencing (WES) of the proband identified a mitochondrial MT-TL1 m.3243A>G mutation with 41.76% heteroplasmy (Figure 2A) and a heterozygous mutation in the CEL gene (c.1336G>A, p.V446I; Figure 2B-D). Family members underwent Sanger sequencing, which showed that the sister harbored both the MT-TL1 m.3243A>G variant (heteroplasmy: 4.72%; Figure 2E) and the CEL mutation (Figure 2F). The mother did not carry the MT-TL1 mutation (Figure 2G) but carried the same CEL mutation (associated with diabetes mellitus; Figure 2H).

The patient was diagnosed with mitochondrial diabetes, MODY, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and diabetic retinopathy.

During hospitalization, the patient received intensive insulin therapy, coenzyme Q10 to support mitochondrial function, and alpha-lipoic acid and methylcobalamin for nerve health. Long-term management will require retinal laser therapy and the use of hearing aids.

At the 6-month follow-up, blood glucose levels showed a significant decrease (fasting, 7-8 mmol/L; 2-hour postprandial: 9-10 mmol/L). There was improvement in peripheral neuropathy symptoms, and electromyography and fundus examination showed no signs of progression.

Mitochondrial gene mutations and CEL gene mutations cause distinct forms of monogenic diabetes, and their co-occurrence due to overlapping genetic backgrounds or metabolic mechanisms may complicate the clinical presentation. Furthermore, this case featured negative diabetes autoantibodies, low fasting C-peptide levels that correlated with low fasting blood glucose, and impaired pancreatic function demonstrated by subnormal results on an oral glucose tolerance test. The patient’s atypical diabetes presentation, including young age at onset, initial presentation with diabetic ketoacidosis, impaired islet function, and significant weight loss, warranted a high clinical suspicion for monogenic diabetes. The concurrent presence of sensorineural hearing loss and early-onset microvascular complications (stage 3 retinopathy) was consistent with mitochondrial diabetes, warranting comprehensive genetic testing for precise diabetes subtype classification.

This case involves juvenile diabetes mellitus resulting from the mitochondrial MT-TL1 m.3243A>G mutation (41.7% heterozygosity) in conjunction with a heterozygous mutation in the CEL gene c.1336G>A (p.V446I). The genetic characteristics and family transmission patterns in this case offer insights into the synergistic effects of nuclear and mitochondrial genes in the development of diabetes mellitus. The patient underwent systematic screening for nuclear and mitochondrial genomic variants using WES with target capture technology. Additionally, family members underwent Sanger sequencing to determine the genetic origin of the mutations and their associated phenotypes.

The CEL gene, located on chromosome 9q34.3, encodes carboxyl ester lipase 1, which is primarily expressed in pancreatic acinar cells and plays a role in lipid digestion and the regulation of cholesterol metabolism[4]. The identified c.1336G>A (p.V446I) mutation in this case occurred in exon 10, resulting in a valine-to-isoleucine substitution at position 446 within the substrate-binding domain. Genetic testing revealed cosegregation of this mutation within the family, with the mother carrying the same heterozygous mutation and having diabetes mellitus. The missense mutation p.V446I, unlike frameshift mutations (e.g., c.1686delT) commonly observed in Caucasian populations, may retain partial enzymatic activity[5]. This could result in reduced penetrance (later disease onset in the mother) and a milder phenotype (absence of severe steatorrhea), suggesting that ethnicity-specific mutation profiles may influence disease severity. Current evidence suggests that mutations in the CEL gene may be associated with MODY8[6]. While the “CEL1336” nomenclature may refer to a specific mutation at nucleotide position 1336 (e.g., c.1336G>A), additional analysis of the mutation’s type and location is required for classification. The c.1336G>A (p.V446I) variant has not been definitively assigned to any MODY subtype. Pathogenic CEL mutations typically occur in exon 11 as frameshift variants, resulting in carboxy-terminal protein truncation and β-cell dysfunction[7]. In this family, the c.1336G>A (p.V446I) mutation—a missense rather than a frameshift—lies in exon 10 or upstream regions (assuming exon 11 begins near c.1686), outside the known MODY8 hotspot. The c.1336G>A (p.V446I) variant is currently considered nonpathogenic in this pedigree, given that, although all three family members (mother, daughter, and son) carry the variant, only the mother and son developed diabetes.

The m.3243A>G mutation in mtDNA is the most prevalent pathogenic variant in the MT-TL1 gene. Disrupting the structure of tRNALeu (UUR) impairs mitochondrial protein translation and oxidative phosphorylation[8]. When the proportion of mutated mtDNA in pancreatic β-cells reaches 30%, it can trigger diabetes[9]. The proband’s mutation burden of 41.76% in blood far exceeded the threshold for β-cell dysfunction, whereas the sister’s burden of 4.72% was below the threshold for clinical manifestation, consistent with the heteroplasmy-dependent nature of mitochondrial disorders. Mitochondrial diabetes follows a maternal inheritance pattern[10] (Figure 2I). In this pedigree, both the patient and the sister harbored the mutation, while their mother tested negative on peripheral blood testing. Potential explanations include: (1) A cryptic maternal mutation, in which the mother has low-level heteroplasmy undetected in peripheral blood but present in gonadal tissues (oocytes) or other organs; or (2) A de novo mutation, in which the mutation in the offspring arose spontaneously during embryogenesis (rare but plausible)[11]. Maternal mitochondrial function declines with age due to a decrease in both mitochondrial quantity and quality in the oocyte, resulting in an inadequate energy supply to the embryo. However, this decline is not directly linked to the accumulation of specific mtDNA mutations[12]. Current studies do not clearly indicate that maternal age directly increases the proportion of mtDNA mutations in offspring. If the mother indeed carries undetected low-level heteroplasmy, aging could amplify mitotic segregation bias in germ cells, resulting in stochastic enrichment of mutant mtDNA in subsequent oocytes, potentially explaining the son's 41.76% mutation load. Differences in mutation proportions between offspring may be due to a heterogeneous, random distribution, whereby the proportion of normal and mutated mtDNA varies among oocytes from the same mother[13]. This random allocation during early embryonic development may explain the difference in mutation rates between the daughter and the son (4% vs 40%). Regarding tissue-specific distribution, the proband’s metabolically active organs (e.g., pancreas and cochlea) likely harbor significantly higher mutation loads than the blood, which could explain the early-onset diabetes at age 24 and the mild loss of high-frequency hearing.

The three CEL mutation carriers in this pedigree exhibited marked phenotypic divergence: The proband, who had double mutations, developed early-onset diabetes at the age of 24 years; the mother with a single CEL mutation had late-onset diabetes, and the sister with two mutations but a low mitochondrial mutation load remained unaffected. This heterogeneity likely stems from the complex interplay among genetic load, environmental factors, and threshold effects[14]. The two-hit hypothesis suggests that the mitochondrial m.3243A>G mutation is the initial hit, directly impairing β-cell energy metabolism and insulin secretory function, thereby laying the pathological foundation for the onset of diabetes[15]. This mutation in the MT-TL1 gene impairs leucine tRNA synthesis, resulting in dysfunctional oxidative phosphorylation and significantly reduced ATP production[16]. Research suggests that when mutant mtDNA exceeds 30%, β-cell compensatory capacity is overwhelmed, resulting in impaired insulin secretion. The proband’s mutation load of 41.76% in peripheral blood surpasses this threshold, consistent with early-onset diabetes at age 24. The presence of neurosensory deafness and retinopathy further reveals the pathogenic role of mitochondrial dysfunction. The second hit is the CEL c.1336G>A (p.V446I) missense variant, which may exacerbate damage to the pancreatic exocrine–endocrine axis by interfering with exocrine enzyme activity through a dominant-negative mechanism. Although it is not in a known mutational hotspot (e.g., exon 11 frameshifts), the valine-to-isoleucine substitution could lead to chronic exocrine dysfunction. Animal studies have shown that CEL deficiency can cause acinar cell apoptosis and localized inflammation.

The proband’s double mutation likely produced a synergistic effect: Mitochondrial dysfunction compromised β-cell function, while the CEL mutation intensified oxidative stress and inflammatory responses through exocrine injury, leading to insulin deficiency and ketoacidosis. The mother, with only the CEL mutation, developed late-onset, mild diabetes, likely due to progressive exocrine damage, resulting in a MODY8-like presentation without the mitochondrial impairment that accelerated disease onset in the proband. The sister, harboring a double mutation with a low mitochondrial load of 4.72%, remains unaffected due to preserved β-cell function, which masks the effects of the CEL variant. However, future stressors, such as pregnancy, could unmask latent metabolic vulnerabilities, highlighting the need for clinical monitoring.

Environmental and immunological factors may modulate disease penetrance, given the phenotypic variability among family members with similar genetic backgrounds. Key considerations include dietary patterns, in which high-fat diets may accelerate pancreatic injury in CEL mutation carriers, whereas traditional Asian low-fat diets may delay exocrine dysfunction[17]. Furthermore, epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation or miRNA regulation, can also influence the expression of mutant genes. For instance, nutritional excess might suppress protective genes such as CEL via methylation[18].

As pancreatic enzyme replacement and nutritional support, pancrelipase dosage should be adjusted to the low-fat dietary characteristics of Asian populations, with concurrent monitoring of fat-soluble vitamin levels (particularly vitamin D). Mitochondrial antioxidant therapy with coenzyme Q10 (200 mg/day) can help mitigate oxidative damage. It is also important to avoid mitochondria-toxic drugs such as metformin, which inhibits complex I. α-lipoic acid and methylcobalamin should be administered to support nerve health. Multidisciplinary collaboration is crucial for preventing complications. Recommended monitoring includes pure-tone audiometry and urinary microalbumin testing every 6 months to detect potential complications related to m.3243A>G, allowing for early intervention. Regular metabolic and cardiac evaluations are necessary, including HbA1c, lipid profile, and ECG screening, to prevent complications such as mitochondrial cardiomyopathy and stroke-like episodes.

Genetic counseling is crucial for family risk management. Affected individuals have a 50% chance of passing CEL mutations to their offspring, and all offspring will inherit the mitochondrial mutation with an indeterminate load. Preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders can help manage this risk. The sister should undergo biennial evaluations of glucose metabolism and mutation load, particularly during periods of metabolic stress, such as pregnancy, despite being phenotypically negative at present.

This study suggests a “two-hit” theory involving mutations in the CEL and mitochondrial genes, providing novel insights into the genetic mechanisms of monogenic diabetes. However, the study has limitations, including its single-family scope, and the findings may not be generalizable across different ethnicities. Furthermore, functional experimental validation is required to determine the pathogenicity and penetrance of the p.V446I mutation.

The mitochondrial m.3243A>G mutation serves as the first hit, establishing the pathological basis of diabetes through impaired energy metabolism, whereas the CEL gene mutation acts as the second hit, accelerating β-cell failure via exocrine–endocrine crosstalk. The phenotypic heterogeneity in this pedigree—with the proband exhibiting early-onset severe diabetes, the mother having late-onset mild diabetes, and the sister being phenotypically negative—corroborates the dynamic model of mutation-load threshold effects and genetic interactions, providing insights into the complex pathogenesis of monogenic diabetes. Future studies should prioritize expanding sample sizes to establish an epidemiological database of coexisting CEL and mitochondrial mutations in East Asian populations. Additionally, leveraging induced pluripotent stem cell models to simulate the cumulative effects of dual mutations on β-cell function will open avenues for interdisciplinary research on rare diabetic mechanisms.

| 1. | Yahaya TO, Ufuoma SB. Genetics and Pathophysiology of Maturity-onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY): A Review of Current Trends. Oman Med J. 2020;35:e126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Raeder H, Johansson S, Holm PI, Haldorsen IS, Mas E, Sbarra V, Nermoen I, Eide SA, Grevle L, Bjørkhaug L, Sagen JV, Aksnes L, Søvik O, Lombardo D, Molven A, Njølstad PR. Mutations in the CEL VNTR cause a syndrome of diabetes and pancreatic exocrine dysfunction. Nat Genet. 2006;38:54-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Maassen JA, 'T Hart LM, Van Essen E, Heine RJ, Nijpels G, Jahangir Tafrechi RS, Raap AK, Janssen GM, Lemkes HH. Mitochondrial diabetes: molecular mechanisms and clinical presentation. Diabetes. 2004;53 Suppl 1:S103-S109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Johansson BB, Fjeld K, El Jellas K, Gravdal A, Dalva M, Tjora E, Ræder H, Kulkarni RN, Johansson S, Njølstad PR, Molven A. The role of the carboxyl ester lipase (CEL) gene in pancreatic disease. Pancreatology. 2018;18:12-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sun S, Gong S, Li M, Wang X, Wang F, Cai X, Liu W, Luo Y, Zhang S, Zhang R, Zhou L, Zhu Y, Ma Y, Ren Q, Zhang X, Chen J, Chen L, Wu J, Gao L, Zhou X, Li Y, Zhong L, Han X, Ji L. Clinical and genetic characteristics of CEL-MODY (MODY8): a literature review and screening in Chinese individuals diagnosed with early-onset type 2 diabetes. Endocrine. 2024;83:99-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu H, Shu M, Liu C, Zhao W, Li Q, Song Y, Zhang T, Chen X, Shi Y, Shi P, Fang L, Wang R, Xu C. Identification and characterization of novel carboxyl ester lipase gene variants in patients with different subtypes of diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2023;11:e003127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | El Jellas K, Dušátková P, Haldorsen IS, Molnes J, Tjora E, Johansson BB, Fjeld K, Johansson S, Průhová Š, Groop L, Löhr JM, Njølstad PR, Molven A. Two New Mutations in the CEL Gene Causing Diabetes and Hereditary Pancreatitis: How to Correctly Identify MODY8 Cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e1455-e1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goto Y, Nonaka I, Horai S. A mutation in the tRNA(Leu)(UUR) gene associated with the MELAS subgroup of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies. Nature. 1990;348:651-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1439] [Cited by in RCA: 1459] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McMillan RP, Stewart S, Budnick JA, Caswell CC, Hulver MW, Mukherjee K, Srivastava S. Quantitative Variation in m.3243A > G Mutation Produce Discrete Changes in Energy Metabolism. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tsang SH, Aycinena ARP, Sharma T. Mitochondrial Disorder: Maternally Inherited Diabetes and Deafness. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1085:163-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bonnefond A, Unnikrishnan R, Doria A, Vaxillaire M, Kulkarni RN, Mohan V, Trischitta V, Froguel P. Monogenic diabetes. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Bentov Y, Casper RF. The aging oocyte--can mitochondrial function be improved? Fertil Steril. 2013;99:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Stewart JB, Chinnery PF. The dynamics of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy: implications for human health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:530-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 698] [Article Influence: 63.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Klopstock T, Priglinger C, Yilmaz A, Kornblum C, Distelmaier F, Prokisch H. Mitochondrial Disorders. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118:741-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | K S PK, Jyothi MN, Prashant A. Mitochondrial DNA variants in the pathogenesis and metabolic alterations of diabetes mellitus. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2025;42:101183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dabravolski SA, Orekhova VA, Baig MS, Bezsonov EE, Starodubova AV, Popkova TV, Orekhov AN. The Role of Mitochondrial Mutations and Chronic Inflammation in Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Prasad M, Rajagopal P, Devarajan N, Veeraraghavan VP, Palanisamy CP, Cui B, Patil S, Jayaraman S. A comprehensive review on high -fat diet-induced diabetes mellitus: an epigenetic view. J Nutr Biochem. 2022;107:109037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nicoletti CF, Assmann TS, Souza LL, Martinez JA. DNA Methylation and Non-Coding RNAs in Metabolic Disorders: Epigenetic Role of Nutrients, Dietary Patterns, and Weight Loss Interventions for Precision Nutrition. Lifestyle Genom. 2024;17:151-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/