Published online Oct 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i10.110631

Revised: July 17, 2025

Accepted: September 8, 2025

Published online: October 15, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 17.9 Hours

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) affect approximately 18.6 million people worldwide every year. Patients with DFU often present with symptoms such as lower limb infections, ulcers, and deep tissue damage. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a concentrated platelet product that can trigger the release of growth factors and cytokines, which stimulate tissue healing and regeneration and thus alleviates DFU. At present, no comprehensive study has been conducted to verify the effect of PRP in both in vitro and clinical settings for treating DFUs.

To perform the in vitro and clinical evaluation of PRP combined with endo

This study focused on both in vitro and clinical settings. In the in vitro study, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), human dermal fibroblasts (HSFs), and human immortalized keratinocytes (HaCaTs) were treated with PRP. Experiments involving proliferation, migration, tubule formation, and angiogenesis signaling pathways were conducted. In this clinical study, patients who visited the Affiliated Panyu Central Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University from 2020 to 2024 and met enrollment criteria were randomly assigned to 2 groups using prospective block randomization. In the control group, the DFU was treated with endovascular angioplasty and wound debridement. In the PRP + endovascular angioplasty group, PRP was evenly used on the surface of superficial ulcers, followed by endovascular angioplasty to treat vascular occlusion. The key outcomes were measured, in

In the in vitro study, 6% PRP could promote the proliferation and migration of HUVECs, HSFs, and HaCaTs in a high-glucose environment. Additionally, it promoted tubule formation in HUVECs by activating signaling proteins such as Ak strain transforming and extracellular regulated protein kinases 1/2. In the clinical study, a total of 208 patients participated. After 12 months of treatment, the ulcer repair area (14.95 ± 0.16 cm2) and ulcer healing rate were improved in the PRP + endovascular angioplasty group than in the control group (P < 0.05).

The combination of 6% activated PRP and endovascular angioplasty may improve the microcirculation and tissue repair in DFUs. This study offers a novel treatment option for patients with diabetic foot.

Core Tip: This study investigated the effect of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) combined with endovascular angioplasty on diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). The findings revealed that PRP improved the proliferation and migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells, human dermal fibroblasts, and human immortalized keratinocytes. It also activated p38, Ak strain transforming and extracellular regulated protein kinases 1/2, and upregulated vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 to promote angiogenesis. PRP combined with endovascular angioplasty improved microcirculation, especially in the lower limb ischemic area, and promoted tissue repair in DFU conditions. The combination of 6% activated PRP and endovascular angioplasty demonstrated a notable effect in improving DFU conditions, providing a novel treatment option for patients with DFUs.

- Citation: Huang C, Liu HZ, Liang JB, Zhao W, Wang YS, Ruan LF, Zhuang WZ, Li YS, Wang Q, Tang YK. In vitro and clinical evaluation of platelet-rich plasma combined with angioplasty in diabetic foot treatment. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(10): 110631

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i10/110631.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i10.110631

The incidence of diabetes mellitus (DM) increases rapidly. Approximately 500 million individuals globally are affected with DM[1]. Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is one of the severe complications of DM, affecting approximately 18.6 million people worldwide every year[2]. DFU poses a threat to approximately 15% of patients with diabetes, with high incidence and mortality rates[3,4]. DFU is a primary cause of limb amputations in patients with diabetes[5], with a high rate ranging from 25% to 50%. The 5-year survival rate of patients with DFU ranges from 50% to 60%.

Patients with DFU often present symptoms such as lower limb infections, ulcers, and deep tissue damage[6,7]. The occurrence of DFU is closely related to factors such as peripheral vascular disease and infections[8-11]. During skin damage, processes such as angiogenesis, epithelial regeneration, and remodeling occur simultaneously[12]. Angiogenesis is also a complex and coordinated process[13-15]. High blood sugar levels impair vascular regeneration and contribute to the formation and development of diabetic wounds.

Wound healing is a complex process involving the coordinated action of multiple cell types. The biologic functions of the human immortalized keratinocyte (HaCaT) cell line are highly similar to those of normal keratinocytes[16]. Human dermal fibroblasts (HSFs) are the most vital cell type in the dermis of the skin and play a crucial role[17]. HaCaTs, HSFs, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) jointly participate in each stage of skin injury repair, restoring and reconstructing the skin barrier function through cooperation[18].

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a concentrated platelet product obtained after centrifuging whole blood. PRP is activated by adding thrombin or calcium ions, which then triggers the release of growth factors and cytokines[19]. It is used for treating wounds due to its clotting, regenerative, and antimicrobial properties[20]. PRP has now become a promising new dressing for DFUs, which promotes rapid ulcer healing[21-23], with high limb salvage and clinical improvement rates[24]. PRP has advantages in accelerating wound healing, relieving pain, shortening healing time and reducing inflammatory response in treating DFUs wound.

Endovascular angioplasty, performed using percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA)[25,26], is widely used for treating vascular occlusion because of its effectiveness in increasing blood supply to ischemic areas, improving microcirculation, and promoting the repair of blood vessels after debridement.

This study aimed to explore the combined effects of PRP and endovascular angioplasty in treating DFU on both cellular and clinical levels. At the cellular level, activated PRP was applied to immortalized HUVECs, HSFs, and HaCaTs treated under high-glucose conditions, aiming to explore the positive effects of PRP on angiogenesis and skin tissue repair. At the clinical level, the study mainly aimed to explore the efficacy of PRP combined with endovascular angioplasty in promoting the repair of DFU and vascular neogenesis.

In the in vivo study, PRP solution was prepared at the Guangdong Cord Blood Bank using O+ cord blood. The cord blood was centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 minutes, and the whole blood was divided into 3 Layers: The lower layer was the concentrated red blood cells, the upper layer was the platelet-free supernatant, and the yellowish layer at the junction of the 2 Layers was the PRP layer. After extracting the PRP solution under the same centrifugation conditions for the second time, most of the platelet-free plasma from the upper layer was collected, leaving approximately (10.0 ± 0.2) mL of residual liquid in the centrifuge tube. After allowing to stand for 15 minutes and gently shaking the centrifuge tube for approximately 5 minutes, the platelets were fully suspended in the remaining plasma, resulting in the formation of the PRP solution. The average platelet concentration in the PRP was 1 × 109/mL, and the growth factor level was 136 ng/mL. The PRP used for cell-level experiments was activated using the freeze-thaw method. HUVECs, HSFs, and HaCaTs were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Cell proliferation assay: Next, how PRP affects the cell proliferation of HUVECs, HSFs, and HaCaTs under high-glucose condition was evaluated, and the optimal PRP concentration for promoting HUVEC, HSF, and HaCaT proliferation was obtained[27]. For this, 100 μL of HUVECs, HSFs, and HaCaTs were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of approximately 5000 cells/well, followed by culture in complete medium for 36 hours. The cells were subjected to separate experiments, with each volume fraction of the PRP solution serving as an experimental group. Each group consisted of 5 replicates, and 100 μL of the PRP solution was added to each well. The control group comprised cells treated with a 0% PRP solution, and the experimental group comprised the rest. After 36 hours of incubation, 10 μL of the CCK8 reagent was added to each well and incubated in the dark for 2-4 hours. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader, and the cell proliferation rate was calculated.

Cell migration assay: Three parallel horizontal lines were scratched on the bottom of a 6-well plate. Then, an appropriate number of cells were seeded and incubated in the culture medium. Three replicates were performed for each group. The cells were incubated in the incubator and the cell migration was observed at 0, 12, 24, and 36 hours using an inverted microscope (Mshot, China) at 100 × magnification. The ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, United States) was used to analyze the scratch images, measure the pixel area of the gap at each time point, and calculate the migration rate to determine the cell migration capacity.

Tube formation assay for HUVECs: First, 96-well culture plates were precoated with 50 μL of growth-factor-reduced Matrigel (356234; Becton, Dickinson and Company) at 37 °C for 30 minutes, followed by incubation in an incubator for 4 hours. Then, the tube formation was observed and documented using an inverted microscope at 100 × magnification. The images were analyzed using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, United States) to assess the tube formation capability of HUVECs. ImageJ preprocesses the image, converts it to grayscale, and enhances contrast and threshold segmentation, allowing the tube formation capability to be automatically counted after setting the parameters.

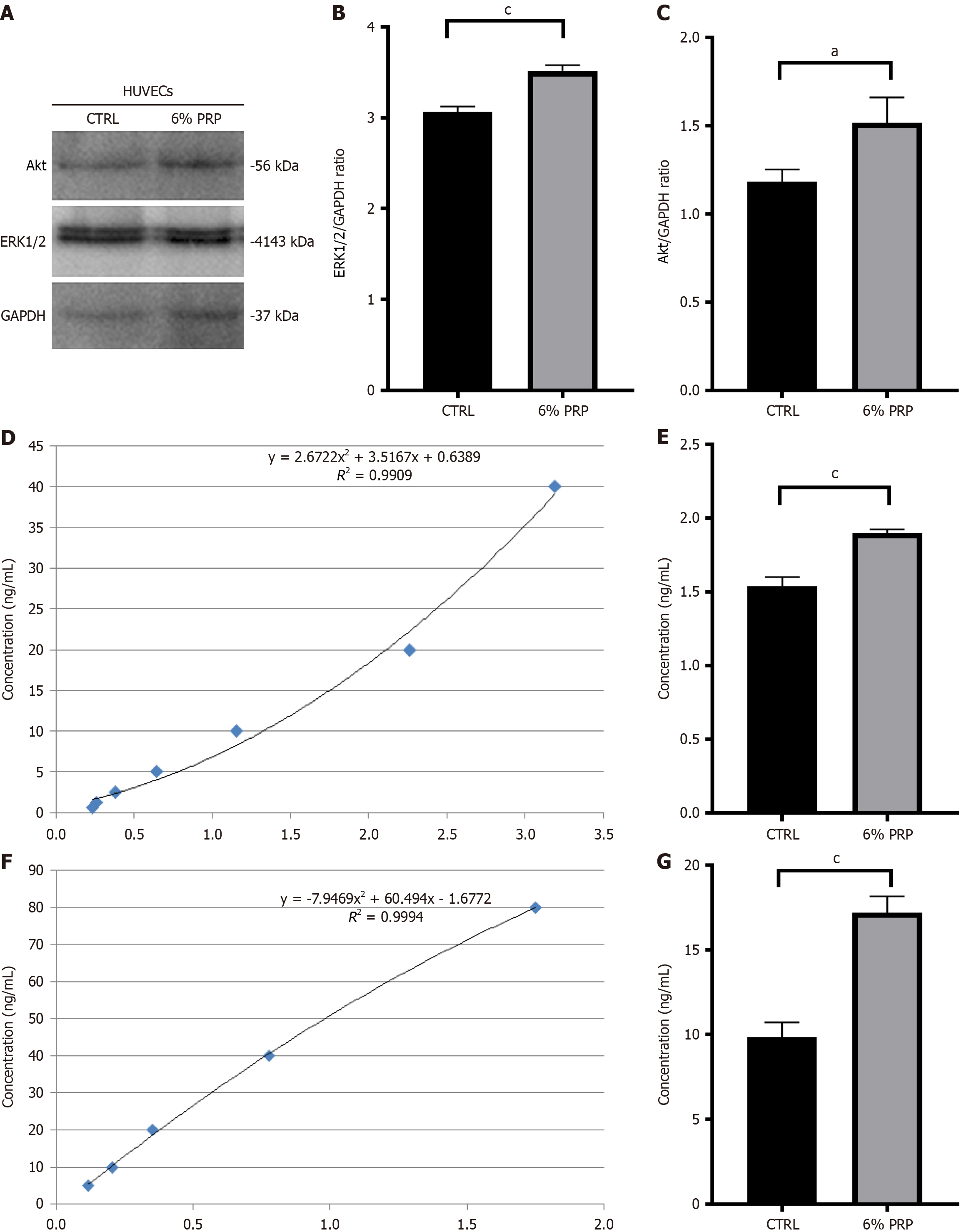

Verification of crucial proteins in the vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway: HUVECs in the control group were pretreated with a serum-free, high-glucose medium, whereas those in the experimental group were treated with a high-glucose medium mixed with 6% PRP to test the expression levels of functional proteins. Then, the Western blot was employed, and the standard protocols of our laboratory was followed[28]. The relative expression levels of Ak strain transforming (Akt) (dilution 1:1000, ET1609-51-50 μL; Huabio) and extracellular regulated protein kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) (dilution 1:1000, ET1609-51-50 μL; Huabio) were detected. A vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (VEGFR2 ELISA) kit (SEB367Hu-48T; Cloud-Clone) and a human p38 protein kinase ELISA kit (MM-60113H2; MEIMIAN) were used to measure the expression levels of VEGFR2 and p38 in HUVECs, respectively. All assays were performed in triplicate.

General information: In the clinical study, patients who visited the Affiliated Panyu Central Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University from 2020 to 2024 and met the inclusion criteria were randomly divided into endovascular angioplasty group and PRP + endovascular angioplasty group. The clinical study used prospective block randomization and patient blinding. Ethical approval was obtained from the medical ethics committee of the Affiliated Panyu Central Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (No.[2019] 59) in the prospective observational study, and informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients. All patients received oral administration of the same empiric antibiotics, antiplatelets 100 mg/day, and statins 10 mg/day.

The inclusion criteria: (1) The patients met the diagnostic criteria for diabetes established by the World Health Organization Expert Committee on Diabetes[29-31]; (2) Had ischemic diabetic foot with ulcers (Wagner grades 1-4)[32]; (3) Suffered from lower limb ischemia or lower limb arterial occlusive disease (Rutherford grades 5 or 6, TASC II A-C)[33,34]; (4) Were aged 20-80 years with independent mobility, regardless of sex; (5) Had a resting Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) of less than 0.9; and (6) Agreed to return for all required follow-up visits.

The exclusion criteria: (1) Breastfeeding or pregnant women; (2) Those with acute diabetic complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis; (3) Those with organ failure (liver, kidney, lung, heart, etc.); and (4) Those allergic to the test product.

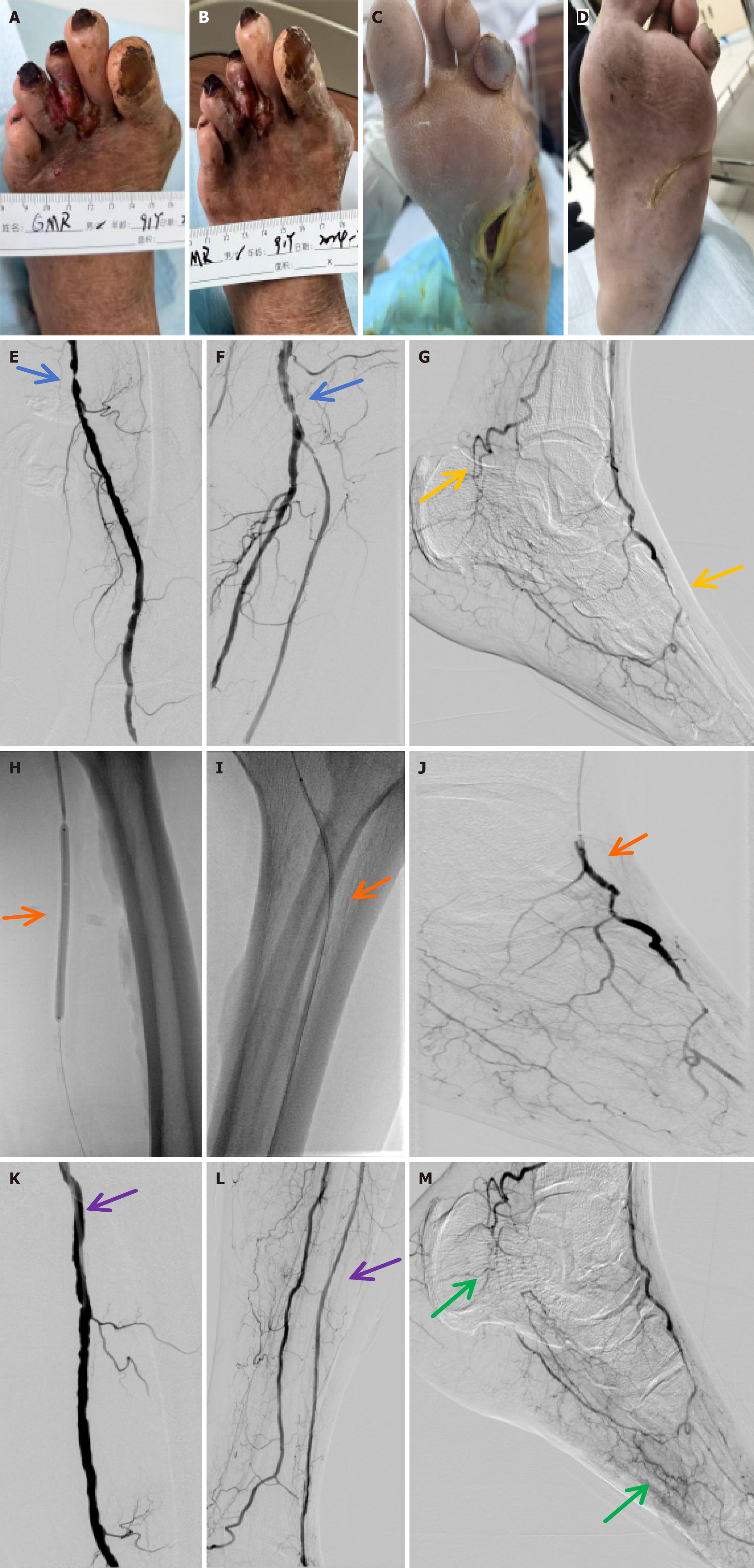

Group treatment: Investigators defined their revascularization strategy a priori, based on the PLAN, GLASS, and TAP systems[35]. Imaging or ultrasound examination was conducted 1, 6, and 12 months after treatment: (1) Endovascular Angioplasty Group: Following wound debridement, a sterile gauze dressing was applied to protect the wound. Then, upon successful retrograde or antegrade puncture of the femoral artery, a guidewire and a catheter were inserted to the proximal end of the occlusion. Based on intraoperative imaging, the length and severity of the vascular stenosis were determined, and PTA was performed at the site of arterial occlusion to restore blood flow[36,37]; and (2) PRP + Endovascular Angioplasty Group: Following wound debridement, the surface of the ulcer was covered with PRP and sterile gauze (and retained for 72 hours). The patients received PRP treatment twice a week for 8 weeks[38-40]. Subsequently, upon successful retrograde or antegrade puncture of the femoral artery, a guidewire and a catheter were inserted into the proximal end of the occlusion. Based on intraoperative imaging, the length and severity of vascular stenosis were determined, and PTA was performed at the site of arterial occlusion to restore blood flow.

Observation indicators: The following observation indicators were used: (1) Rutherford classification[33]; (2) Wagner classification[32]; (3) Skin temperature: A score of 0 indicates markedly cold limb, and infrared thermometer records a temperature difference of more than 4 °C compared with the contralateral limb; 1 indicates cold limb, and temperature difference of more than 3 °C compared with the contralateral limb; 2 indicates cool limb, and temperature difference of more than 2 °C compared with the contralateral limb; 3 indicates mildly cold limb, and temperature difference of more than 1 °C compared with the contralateral limb; and 4 indicates normal; (4) ABI[41]; (5) Vascular occlusion evaluation[37]: A score of 0 indicates no vascular lesions; 1 indicates narrowing or occlusion of 1 vessel below the knee or reduced collateral branches; 2 indicates narrowing or occlusion of 2 vessels below the knee or reduced collateral branches; and 3 indicates narrowing of vessels above the knee, or narrowing or occlusion of 2 or more vessels below the knee or reduced collateral branches; (6) Ulcer healing area: Photographs of ulcers were obtained with a digital camera 1, 6, and 12 months after treatment. The area of superficial ulcers was evaluated using a digital camera combined with a ruler, whereas the volume of sinus ulcers was determined using the saline volume method. Ulcer healing area = Ulcer area at the start of the trial - Real-time monitored ulcer area; and (7) Ulcer healing rate: Ulcer healing rate = (Number of ulcers healed in the group/Number of participants in the group) × 100%.

For in vivo studies, the cell experiments were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (263) software. Two-group comparisons were performed using the t test. Multiple-group comparisons were performed using the conventional one-way or two-way analysis of variance. Significant differences in experimental results were determined using significance analysis, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

For clinical studies, SPSS 25.0 (IBM, United States) statistical software was employed for data analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and two-group comparisons were analyzed using the t test. Categorical data were presented as counts (percentages) and analyzed using the χ2 test. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparison correction). Normality assumptions were tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Optimal PRP concentration promotes the proliferation of HSFs, HaCaTs, and HUVECs: Figure 1A demonstrates that PRP promoted the proliferation of HUVECs, exhibiting a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with a gradual increase in the concentration of PRP solution. At 6% PRP solution, the cell viability rate reached 213.70%, indicating that 6% PRP solution was also favorable for the proliferation of HUVECs.

Figure 1B demonstrates that PRP promoted the proliferation of HSFs, exhibiting a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with a gradual increase in the concentration of PRP solution. A 6% PRP solution was also favorable for HSF proliferation.

Figure 1C demonstrates that PRP promoted HaCaT proliferation, exhibiting a similar trend to that seen for HUVECs and HSFs with an increase in the concentration of PRP solution. A 6% PRP solution was also favorable for HaCaT proliferation.

Figure 2 demonstrates that the PRP-treated groups exhibited a substantial enhancement in cell proliferation compared with the control group under high-glucose conditions. Meanwhile, we observed distinct differences in the proliferation responses of the 3 cell types to PRP in a high-glucose environment. Specifically, HUVECs responded most actively to PRP, with a proliferation rate reaching 213.70%. In contrast, HSFs and HaCaTs also exhibited increased proliferation in the PRP-treated groups, with a proliferation rate reaching 142.81% and 127.53%, respectively, which were lower compared with that of HUVECs.

PRP promotes the migration of HUVECs, HSFs, and HaCaTs: We assessed cell migration ability with or without PRP. This experiment used a high-glucose medium to simulate a hyperglycemic environment and scratched cells in 6-well plates to test the effects of PRP on the migration of HUVECs, HSFs, and HaCaTs. The results revealed that PRP treatment remarkably promoted the migration of HUVECs, HSFs, and HaCaTs in a high-glucose environment (Figure 3).

PRP promotes tube formation assay of HUVECs: The angiogenic activity of PRP was further evaluated by treating HUVECs with PRP in a high-glucose environment. Then, the formed endothelial cell tube and branches were visualized. The results revealed that the number of meshes and junctions considerably increased after treatment with PRP compared with the control group (Figure 4). Notably, a correlation was observed between the number of meshes and junctions. The corresponding increase in junctions with mesh formation appeared higher, indicating that PRP enhanced the tube formation ability of HUVECs.

PRP promotes angiogenesis through p38, Akt, ERK1/2, and VEGFR2: As exosomes could promote HUVEC proliferation, cell migration, and in vitro angiogenesis, we further detected the expression levels of key proteins related to cell proliferation using Western blot. The results indicated that the expression levels of Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), Human p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (p38), Akt and ERK1/2 increased after PRP treatment under high-glucose conditions compared with the control group (Figure 5). Therefore, it can be concluded that PRP promotes the proliferation, survival, and migration of HUVECs by activating p38, Akt, and ERK1/2, and upregulating VEGFR2, thereby enhancing tube formation.

Baseline characteristics of patients before treatment: This study enrolled a total of 208 patients, including 105 in the endovascular angioplasty group and 103 in the PRP + endovascular angioplasty group. Ultrasound examinations were performed to assess arterial occlusion in the lower limbs before treatment. All patients completed a 12-month follow-up. No complications occurred in the surgery procedure.

The results indicated no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of sex, age, smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, renal failure, medication, Rutherford classification, Wagner classification, foot skin color, skin temperature, ABI, vascular occlusion assessment, and ulcer area before treatment (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Characteristics | Endovascular angioplasty (n = 105) | PRP + endovascular angioplasty (n = 103) | P value |

| Males | 63 (60) | 61 (59.2) | 0.73 |

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 75.37 ± 8.37 | 74.54 ± 8.27 | 0.19 |

| Smoking | 34 (32.3) | 32 (31.1) | 0.90 |

| Renal failure, n | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypertension | 76 (72.3) | 74 (71.8) | 0.96 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 49 (46.7) | 51 (50) | 0.91 |

| Rutherford classification | 0.98 | ||

| 5 | 93 (88.5) | 91 (88.3) | |

| 6 | 12 (11.5) | 12 (12.7) | |

| Wagner classification | 0.93 | ||

| 1 | 1 (1) | 2 (1.9) | |

| 2 | 45 (43.9) | 46 (44.7) | |

| 3 | 40 (37.7) | 32 (31.1) | |

| 4 | 17 (16.2) | 19 (18.4) | |

| 5 | 2 (1.9) | 4 (3.9) | |

| Skin temperature | 0.19 | ||

| 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (1.9) | |

| 1 | 26 (24.8) | 25 (24.3) | |

| 2 | 56 (53.3) | 60 (58.3) | |

| 3 | 22 (20.9) | 18 (17.5) | |

| Ankle-Brachial index, mean ± SD | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 0.65 ± 0.11 | 0.68 |

| Vascular occlusion evaluation | 0.82 | ||

| 1 | 29 (27.6) | 32 (31.1) | |

| 2 | 65 (61.9) | 58 (56.3) | |

| 3 | 11 (10.5) | 13 (12.6) | |

| Ulcer healing area, mean ± SD (cm2) | 12.85 ± 1.97 | 12.56 ± 2.02 | 0.23 |

Comparison of ischemic conditions and tissue repair between the 2 groups 1 month after treatment: After 1-month treatment, the results indicated a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in the Rutherford classification and Wagner classification of patients and ulcer repair area (10.83 ± 1.61 cm2) (P < 0.05; Table 2 and Figure 6).

| Characteristics | Endovascular angioplasty (n = 105) | PRP + endovascular angioplasty (n = 103) | P value |

| Rutherford classification | < 0.05 | ||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 4 (3.9) | |

| 2 | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | |

| 3 | 13 (12.4) | 17 (16.5) | |

| 4 | 21 (20) | 36 (34.9) | |

| 5 | 65 (61.9) | 45 (43.7) | |

| 6 | 4 (3.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Wagner classification | < 0.05 | ||

| 0 | 9 (8.6) | 32 (31.1) | |

| 1 | 5 (4.8) | 31 (30.1) | |

| 2 | 33 (31.4) | 26 (25.2) | |

| 3 | 32 (30.5) | 9 (8.7) | |

| 4 | 18 (17.1) | 2 (1.9) | |

| 5 | 8 (7.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Skin temperature | < 0.05 | ||

| 0 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 19 (18.1) | 12 (11.6) | |

| 2 | 46 (43.8) | 30 (29.1) | |

| 3 | 38 (36.2) | 57 (55.3) | |

| 4 | 1 (1) | 4 (3.9) | |

| Ankle-Brachial index, mean ± SD | 0.81 ± 0.12 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | < 0.05 |

| Ulcer healing area, mean ± SD (cm2) | 3.95 ± 0.98 | 10.83 ± 1.61 | < 0.05 |

Comparison of ischemic conditions and tissue repair between the 2 groups 6 and 12 months after treatment: After 6 and 12 months of treatment, the Rutherford classification and Wagner classification of patients were significantly downregulated in the PRP + endovascular angioplasty group. Meanwhile, the PRP + endovascular angioplasty group exhibited a statistically significant difference in skin temperature recovery, ABI (0.75 ± 0.07), ulcer repair area (14.95 ± 0.16 cm2), and ulcer healing rate (88.3%) compared with the endovascular angioplasty groups after 12 months of treatment (P < 0.05; Tables 3 and 4).

| Characteristics | Endovascular angioplasty (n = 105) | PRP + endovascular angioplasty (n = 103) | P value |

| Rutherford classification | < 0.05 | ||

| 1 | 3 (0) | 24 (23.3) | |

| 2 | 2 (1.9) | 25 (24.3) | |

| 3 | 18 (12.4) | 26 (25.2) | |

| 4 | 4 (20) | 17 (16.5) | |

| 5 | 78 (61.9) | 11 (10.7) | |

| 6 | 0 (3.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Wagner classification | < 0.05 | ||

| 0 | 28 (26.7) | 92 (89.3) | |

| 1 | 28 (26.7) | 10 (9.7) | |

| 2 | 38 (36.2) | 1 (1) | |

| 3 | 11 (10.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Skin temperature | < 0.05 | ||

| 0 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 23 (21.9) | 15 (14.6) | |

| 2 | 49 (46.7) | 33 (32) | |

| 3 | 32 (30.5) | 49 (47.6) | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 6 (5.8) | |

| Ankle-Brachial index, mean ± SD | 0.68 ± 0.11 | 0.79 ± 0.08 | < 0.05 |

| Vascular occlusion evaluation | 0.76 | ||

| 1 | 59 (56.2) | 60 (58.3) | |

| 2 | 46 (43.8) | 43 (41.7) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Ulcer healing area, mean ± SD (cm2) | 5.95 ± 0.98 | 12.13 ± 1.01 | < 0.05 |

| Ulcer healing rate (%) | 54.3 | 80.6 | < 0.05 |

| Characteristics | Endovascular angioplasty (n = 105) | PRP + endovascular angioplasty (n = 103) | P value |

| Rutherford classification | < 0.05 | ||

| 1 | 20 (19.0) | 22 (21.3) | |

| 2 | 17 (16.2) | 33 (32.0) | |

| 3 | 20 (19.0) | 29 (28.2) | |

| 4 | 32 (30.6) | 19 (18.5) | |

| 5 | 16 (15.2) | 0 (0) | |

| 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Wagner classification | < 0.05 | ||

| 0 | 89 (84.8) | 103 (100) | |

| 1 | 11 (10.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 5 (4.7) | 0 (0) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Skin temperature | < 0.05 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 14 (21.9) | 11 (14.6) | |

| 2 | 56 (46.7) | 15 (32) | |

| 3 | 28 (30.5) | 58 (47.6) | |

| 4 | 5 (0) | 19 (5.8) | |

| Ankle-Brachial index, mean ± SD | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.75 ± 0.07 | < 0.05 |

| Vascular occlusion evaluation | 0.07 | ||

| 1 | 10 (9.5) | 21 (20.4) | |

| 2 | 82 (78.1) | 73 (70.9) | |

| 3 | 13 (12.4) | 9 (8.7) | |

| Ulcer healing area, mean ± SD (cm2) | 8.68 ± 0.18 | 14.95 ± 0.16 | < 0.05 |

| Ulcer healing rate (%) | 61.9 | 88.3 | < 0.05 |

The platelet concentration of PRP significantly increases, typically reaching 4 to 7 times the physiological concentration of platelets[42]. Cell and animal experiments indicate that PRP can inhibit ferroptosis[43], suppress fibroblast apoptosis and pyroptosis[44], promote collagen deposition, re-epithelialization[45], and enhance angiogenesis in diabetic wound healing[46]. PRP has several remarkable advantages, including reducing inflammation and the amount of infected fluid, especially in cases of chronic osteomyelitis associated with soft-tissue defects[47]. miRNA-21 may regulate the expression of nuclear factor kappa-B to promote proliferation in infected DFUs treated by PRP[48]. PRP[49] is ineffective when combined with guided tissue regeneration procedures. However, it has demonstrated promise in treating DFUs by accelerating wound healing, relieving pain, shortening healing time, and reducing inflammatory response[50]. PRP therapy has been shown to represents a viable and secure therapeutic alternative for individuals with DFU[51].

Our study verified that PRP can promote the proliferation and migration of HSFs and HaCaTs, creating a favorable environment for tissue repair. Further experiments demonstrated that 2% PRP solution was the most favorable for HSF proliferation. Notably, a 10% PRP solution inhibited HSF survival, suggesting that high concentrations of PRP may not be favorable for HSF proliferation. An 8% PRP concentration was most effective in promoting HaCaT proliferation. Notably, a PRP concentration of > 14% essentially ceased to promote HaCaT proliferation and even inhibited HaCaT activity at high concentration levels. PRP activated by the repeated freeze-thaw method was most effective in promoting HUVEC proliferation at a concentration of 6% PRP. This study identified that 6% PRP concentration promoted the proliferation of 3 cell types, providing a basis for choosing concentrations for subsequent experiments.

Furthermore, we observed that PRP had varied roles across various cell types. For instance, the optimal PRP concentration for promoting cell proliferation varied among various cell types. As the study used strictly controlled variables, excluding the influence of PRP preparation and activation, we hypothesized that this discovery may be attributed to specific characteristics of various cell types. Varied cell responses to high-glucose environments may also play a role. As PRP exerts biologic activity by releasing numerous growth factors upon activation, it is crucial to activate PRP just before use to avoid the inactivation of growth factors due to prolonged storage. According to our results, PRP activated by the repeated freeze-thaw method at a 6% concentration exhibited improved effect on tissue repair and angiogenesis under high-glucose conditions.

This study suggested that PRP may contain VEGF signaling proteins that upregulate VEGFR2 expression. The binding of ligands and receptors activates the VEGF signaling pathway, upregulating the levels of downstream proteins such as Akt, p38, and ERK1/2, thereby promoting the survival, proliferation, and migration of HUVECs and angiogenesis. PRP promotes angiogenesis and tissue repair in a high-glucose environment, indicating its promising potential for use in the clinical treatment of DFU. HUVECs contribute to faster ulcer healing, and these findings can be applied in clinical practice to precisely promote wound healing.

Our clinical experiments indicated that PTA with balloon catheter of occluded vessels effectively improved blood supply to ischemic areas and reduced the severity of lower limb arterial occlusion, thereby facilitating ulcer repair. Following endovascular angioplasty and PRP application, blood supply to the lower extremities was enhanced and the conditions of the ischemic microenvironment were improved, supporting the exchange of sufficient nutrients and waste. This was more conducive to the regeneration of peripheral blood vessels, forming a rich network of capillaries at the distal end of the vascular lesions to downgrade Rutherford classification and improve ABI. Skin regained its rosy color and normal skin temperature, and demonstrated accelerated ulcer healing. It was especially effective for ulcers with high Wagner grades, which considerably improved blood flow in the affected limbs of patients with diabetic lower limb ischemia and promoted the repair of necrotic blood vessels and gangrene.

Most patients with DFU having vascular disease are elderly people. The patients with advanced average age > 74 years received treatment in this study; therefore, PRP combined with angioplasty treatment for DFU is encouraging.

This study had certain limitations. The method of simulating a diabetic environment with high glucose needs further refinement. We were well aware that the in vitro environment created with high glucose may not fully reflect the diabetic foot microenvironment. In the future, a more holistic approach to DFU healing should consider additional factors such as inflammatory environment, bacteria, and neurotransmitters. Moreover, future studies should explore the co-culturing of endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes to investigate potential interactions or synergistic effects in wound healing under PRP treatment. Furthermore, the lack of histologic or histopathologic tissue evaluation was also a limitation. Further research into the ineffectiveness of PRP and potential harms is crucial. PRP application was performed twice a week for 8 weeks. We will continue to explore the effects of alternative application frequencies to guide future studies.

The combination of 6% activated PRP and endovascular angioplasty exhibited a notable effect in improving DFU conditions, providing a new treatment option for patients with DFU (Supplementary Figure 1).

| 1. | Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 5898] [Article Influence: 1474.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 2. | Armstrong DG, Tan TW, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Review. JAMA. 2023;330:62-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 841] [Article Influence: 280.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Falanga V. Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet. 2005;366:1736-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1532] [Cited by in RCA: 1754] [Article Influence: 83.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Wu Q, Chen B, Liang Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Prospective Therapy for the Diabetic Foot. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:4612167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stoekenbroek RM, Lokin JLC, Nielen MM, Stroes ESG, Koelemay MJW. How common are foot problems among individuals with diabetes? Diabetic foot ulcers in the Dutch population. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1271-1275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J, Lipsky BA, Hinchliffe RJ, Game F, Rayman G, Lazzarini PA, Forsythe RO, Peters EJG, Senneville É, Vas P, Monteiro-Soares M, Schaper NC; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. Definitions and criteria for diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36 Suppl 1:e3268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Jiang X, Yuan Y, Ma Y, Zhong M, Du C, Boey J, Armstrong DG, Deng W, Duan X. Pain Management in People with Diabetes-Related Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia. J Diabetes Res. 2021;2021:6699292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ahmad J. The diabetic foot. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2016;10:48-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Deng L, Du C, Song P, Chen T, Rui S, Armstrong DG, Deng W. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Diabetic Wound Healing. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:8852759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 81.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Meyer M, Müller AK, Yang J, Ŝulcová J, Werner S. The role of chronic inflammation in cutaneous fibrosis: fibroblast growth factor receptor deficiency in keratinocytes as an example. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:48-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pietramaggiori G, Scherer SS, Mathews JC, Alperovich M, Yang HJ, Neuwalder J, Czeczuga JM, Chan RK, Wagner CT, Orgill DP. Healing modulation induced by freeze-dried platelet-rich plasma and micronized allogenic dermis in a diabetic wound model. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:218-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3609] [Cited by in RCA: 4570] [Article Influence: 253.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dudley AC, Griffioen AW. Pathological angiogenesis: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Angiogenesis. 2023;26:313-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 99.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Parmar D, Apte M. Angiopoietin inhibitors: A review on targeting tumor angiogenesis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;899:174021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang Y, Liu NM, Wang Y, Youn JY, Cai H. Endothelial cell calpain as a critical modulator of angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863:1326-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang J, Deng P, Qi Y, Feng X, Wen H, Chen F. MicroRNA-185 inhibits the proliferation and migration of HaCaT keratinocytes by targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21:366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tchemtchoua VT, Atanasova G, Aqil A, Filée P, Garbacki N, Vanhooteghem O, Deroanne C, Noël A, Jérome C, Nusgens B, Poumay Y, Colige A. Development of a chitosan nanofibrillar scaffold for skin repair and regeneration. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3194-3204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Martin P, Nunan R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of repair in acute and chronic wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:370-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 731] [Article Influence: 66.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | OuYang H, Tang Y, Yang F, Ren X, Yang J, Cao H, Yin Y. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer: a systematic review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1256081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Smith OJ, Leigh R, Kanapathy M, Macneal P, Jell G, Hachach-Haram N, Mann H, Mosahebi A. Fat grafting and platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: A feasibility-randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1578-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Bakadia BM, Qaed Ahmed AA, Lamboni L, Shi Z, Mutu Mukole B, Zheng R, Pierre Mbang M, Zhang B, Gauthier M, Yang G. Engineering homologous platelet-rich plasma, platelet-rich plasma-derived exosomes, and mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes-based dual-crosslinked hydrogels as bioactive diabetic wound dressings. Bioact Mater. 2023;28:74-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huang Q, Wu T, Guo Y, Wang L, Yu X, Zhu B, Fan L, Xin JH, Yu H. Platelet-rich plasma-loaded bioactive chitosan@sodium alginate@gelatin shell-core fibrous hydrogels with enhanced sustained release of growth factors for diabetic foot ulcer healing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;234:123722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Qian Z, Wang H, Bai Y, Wang Y, Tao L, Wei Y, Fan Y, Guo X, Liu H. Improving Chronic Diabetic Wound Healing through an Injectable and Self-Healing Hydrogel with Platelet-Rich Plasma Release. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:55659-55674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Eldin MMB, Abd Elaziz AAR, Mohamed Hamada NM, Mohamed AEZ. Role of Platelet Rich Plasma in Accelerating the Healing Rate of Diabetic Foot Ulcer. QJM Int J Med. 2021;114:hcab092. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Armstrong EJ, Brodmann M, Deaton DH, Gray WA, Jaff MR, Lichtenberg M, Rundback JH, Schneider PA. Dissections After Infrainguinal Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty: A Systematic Review and Current State of Clinical Evidence. J Endovasc Ther. 2019;26:479-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Vossen RJ, Vahl AC, Leijdekkers VJ, Montauban van Swijndregt AD, Balm R. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty with Optional Stenting in Patients with Superficial Femoral Artery Disease: A Retrospective, Observational Analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;56:690-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huang C, Luo W, Wang Q, Ye Y, Fan J, Lin L, Shi C, Wei W, Chen H, Wu Y, Tang Y. Human mesenchymal stem cells promote ischemic repairment and angiogenesis of diabetic foot through exosome miRNA-21-5p. Stem Cell Res. 2021;52:102235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 28. | Liang J, Cheng S, Song Q, Tang Y, Wang Q, Chen H, Feng J, Yang L, Li S, Wang Z, Fan J, Huang C. Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Induced by Advanced Glycation End Products on Energy Metabolism in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Kidney Int Rep. 2024;10:227-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Richter B, Hemmingsen B, Metzendorf MI, Takwoingi Y. Development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in people with intermediate hyperglycaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD012661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Use of Glycated Haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus: Abbreviated Report of a WHO Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011 . [PubMed] |

| 32. | Wagner FW Jr. The dysvascular foot: a system for diagnosis and treatment. Foot Ankle. 1981;2:64-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 627] [Cited by in RCA: 620] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 33. | Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG; TASC II Working Group. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg. 2007;45 Suppl S:S5-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4051] [Cited by in RCA: 4217] [Article Influence: 221.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, Johnston KW, Porter JM, Ahn S, Jones DN. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:517-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2587] [Cited by in RCA: 2622] [Article Influence: 90.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Conte MS, Bradbury AW, Kolh P, White JV, Dick F, Fitridge R, Mills JL, Ricco JB, Suresh KR, Murad MH; GVG Writing Group. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69:3S-125S.e40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 1001] [Article Influence: 143.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Allaqaband S, Kirvaitis R, Jan F, Bajwa T. Endovascular treatment of peripheral vascular disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2009;34:359-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Malas MB, Qazi U, Glebova N, Arhuidese I, Reifsnyder T, Black J, Perler BA, Freischlag JA. Design of the Revascularization With Open Bypass vs Angioplasty and Stenting of the Lower Extremity Trial (ROBUST): a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:1289-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nolan GS, Smith OJ, Heavey S, Jell G, Mosahebi A. Histological analysis of fat grafting with platelet-rich plasma for diabetic foot ulcers-A randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2022;19:389-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Xu H, Huang K, Tao X. Efficacy and safety of platelet-rich plasma versus conventional care in diabetic foot ulcers: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Diabetol. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Zhen PX, Su HJ, Yang SJ, Chen X, Lin ZM, Liu SN. Comparison of clinical efficacy between tibial cortex transverse transport and platelet-rich plasma treatment for severe diabetic foot ulcers. Front Surg. 2025;12:1507982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Clairotte C, Retout S, Potier L, Roussel R, Escoubet B. Automated ankle-brachial pressure index measurement by clinical staff for peripheral arterial disease diagnosis in nondiabetic and diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1231-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Peng GL. Platelet-Rich Plasma for Skin Rejuvenation: Facts, Fiction, and Pearls for Practice. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019;27:405-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Chen L, Wu D, Zhou L, Ye Y. Platelet-rich plasma promotes diabetic ulcer repair through inhibition of ferroptosis. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10:1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Chen C, Wang Q, Li D, Qi Z, Chen Y, Wang S. MALAT1 participates in the role of platelet-rich plasma exosomes in promoting wound healing of diabetic foot ulcer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;238:124170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zhou J, Liu Y, Liu X, Wan J, Zuo S, Pan T, Liu Y, Sun F, Gao M, Yu X, Zhou W, Xu J, Zhou Z, Wang S. Hyaluronic acid-based dual network hydrogel with sustained release of platelet-rich plasma as a diabetic wound dressing. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;314:120924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Chen T, Song P, He M, Rui S, Duan X, Ma Y, Armstrong DG, Deng W. Sphingosine-1-phosphate derived from PRP-Exos promotes angiogenesis in diabetic wound healing via the S1PR1/AKT/FN1 signalling pathway. Burns Trauma. 2023;11:tkad003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Wang HF, Gao YS, Yuan T, Yu XW, Zhang CQ. Chronic calcaneal osteomyelitis associated with soft-tissue defect could be successfully treated with platelet-rich plasma: a case report. Int Wound J. 2013;10:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Li T, Ma Y, Wang M, Wang T, Wei J, Ren R, He M, Wang G, Boey J, Armstrong DG, Deng W, Chen B. Platelet-rich plasma plays an antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and cell proliferation-promoting role in an in vitro model for diabetic infected wounds. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:297-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Panda S, Doraiswamy J, Malaiappan S, Varghese SS, Del Fabbro M. Additive effect of autologous platelet concentrates in treatment of intrabony defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Investig Clin Dent. 2016;7:13-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Platini H, Adammayanti KA, Maulana S, Putri PMK, Layuk WG, Lele JAJMN, Haroen H, Pratiwi SH, Musthofa F, Mago A. The Potential of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Gel for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Care Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2024;20:21-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Deng J, Yang M, Zhang X, Zhang H. Efficacy and safety of autologous platelet-rich plasma for diabetic foot ulcer healing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18:370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/