Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.116336

Revised: November 25, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 86 Days and 23.9 Hours

The epidemiology of colorectal cancer (CRC) varies significantly, with an in

To characterize the detection rates and risk factors for colorectal lesions in the high-altitude population of Xizang Autonomous Region.

In this cross-sectional study, 1154 Tibetans undergoing high-definition colonoscopy were enrolled. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were conducted to analyze the risk factors for CRA. Data were collected via ques

The detection rates in the Xizang Autonomous Region cohort were 7.7% for CRA (n = 89) and 1.6% for CRC (n = 18). Univariate analysis showed that CRA was associated with advanced age, male sex, higher BMI, and higher risk tiers on both the China and APCS scores. However, multivariate logistic regression confirmed only advanced age (OR = 1.035, 95%CI: 1.019-1.052, P < 0.001) and male sex (OR = 2.161, 95%CI: 1.337-3.492, P = 0.002) as independent risk factors. In the comparative analysis, the Xizang CRA detection rate was significantly lower than that in the matched Beijing cohort (7.7% vs 22.8%, P < 0.001). No significant difference was found in CRC detection rates (1.6% vs 1.3%, P = 0.626).

The prevalence of CRA in the high-altitude population was significantly lower. Advanced age and male sex remain independent risk factors for CRA in Xizang Autonomous Region.

Core Tip: In this cross-sectional study of 1154 Tibetans, the colorectal adenoma (CRA) detection rate in the high-altitude Xizang Autonomous Region population was 7.7%. This was significantly lower than the 22.8% rate found in a rigorously matched low-altitude Beijing cohort. Advanced age and male sex were identified as the only independent risk factors for CRA in the Xizang Autonomous Region group.

- Citation: Zhao XL, Chen WY, Liu YM, Danzeng SL, Pingcuo QZ, Yu Z, Chen HD, Ciren YJ, Wu D. Detection rate and risk factors of colorectal adenoma in high-altitude population: A cross-sectional study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 116336

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/116336.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.116336

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide, with incidence and mortality rates continuing to rise, posing a severe threat to human health and life[1,2]. In recent years, as lifestyles and dietary habits have shifted, the incidence of CRC in China has shown an upward trend, particularly in large cities and coastal areas[3,4]. The majority of CRCs develop via the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, establishing colorectal adenoma (CRA) as the primary precancerous lesion. Endoscopy is recognized as the most effective modality for digestive system cancer prevention, not merely for early cancer detection but, more critically, for the identification and removal of CRA, thereby interrupting their potential progression to malignancy[5].

Variations in environmental factors, lifestyle, and genetic background across different regions may lead to significant disparities in the risk of developing CRA[6,7]. It was analyzed that the cause-specific mortality in China based on global burden of disease data and found that the age-standardized death rate for CRC in the Xizang Autonomous Region was the lowest in China. Xizang Autonomous Region is located on the high-altitude plateau and has a unique population structure, lifestyle, and environment[8-10]. Investigating the detection rates and associated risk factors for CRA via co

Therefore, this study aimed to characterize the prevalence and risk factors of colorectal lesions including CRA and CRC in the high-altitude population of Xizang Autonomous Region using both univariate and multivariate analyses of colo

This cross-sectional study was conducted using prospective data. We prospectively enrolled consecutive Tibetan patients aged ≥ 18 years who were scheduled for colonoscopy at the Department of Gastroenterology, the People's Hospital of Xizang Autonomous Region between January 2024 and October 2024. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the People's Hospital of Xizang Autonomous Region (Approval No. ME-TBHP-24-KJ-050). After providing written informed consent, each participant was invited to complete a structured questionnaire administered by trained staff to collect data on demographic information and lifestyle habits. This was completed prior to colonoscopy.

Inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) Age ≥ 18 years; and (2) Completion of the questionnaire and the colonoscopy procedure. We excluded individuals with: (1) A personal history of CRC or other malignancies; (2) A diagnosis of hereditary CRC, such as Lynch syndrome; (3) A known hereditary polyposis syndrome, such as familial adenomatous polyposis; (4) Contraindications for colonoscopy; or (5) Inability to provide informed consent or complete the ques

To contextualize the findings from the high-altitude cohort, a comparative control group was established from in

To ensure procedural consistency and data comparability between the Xizang Autonomous Region and Beijing cohorts, standardized protocols were implemented at both institutions. Prior to the procedure, all participants received detailed verbal and written instructions for bowel cleansing and consumed a standard, split-dose regimen of a polyethylene glycol-based electrolyte solution. The quality of the bowel preparation was systematically evaluated by the endoscopist using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS). To ensure high-quality mucosal visualization in both cohorts, only exa

Prior to colonoscopy, all participants’ data were collected prospectively by trained staff using a single, comprehensive questionnaire. This instrument captured a wide range of information on both demographic and social characteristics, including age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, highest education level, and occupation. Geographic data, specifically long-term place of residence and its corresponding altitude, were also recorded. Anthropometric measurements of height and weight were recorded to calculate BMI. The questionnaire also documented key clinical and lifestyle factors, including self-reported history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, previous abdominal surgery, and smoking status, which was defined as ever-smoker vs never-smoker. A family history of CRC was considered positive if a participant reported at least one first-degree relative with the disease. Two validated risk stratification scores, the China Sporadic Colorectal Cancer Risk Score and the Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening (APCS) score (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), were cal

Data management followed a strict workflow. To address follow-up data management, a standardized protocol was used to track and match histopathological results with endoscopic findings. All distinct data streams—questionnaire responses, endoscopic reports, and pathological records—were integrated into a dedicated database. To ensure rigorous data quality control and consistency across the two centers, identical standard operating procedures were enforced, in

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 26.0 (Armonk, NY, United States) and R version 4.2.2 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables following a normal distribution are expressed as mean ± SD and were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Independent sample t tests were used for between-group comparisons, paired sample t tests for within-group comparisons, and one-way analysis of variance for comparing normally distributed continuous variables across multiple groups. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages and were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Variables with significant results in univariate analysis were further examined using multivariate logistic regression. Linear trend analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 (San Diego, CA, United States). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 1154 participants of Tibetan ethnicity were included in the study. CRA was detected in 89 (7.7%) and CRC in 18 (1.6%). The mean age of the population was 46.49 ± 14.19 years. The gender distribution was 50.1% female and 49.9% male. The average BMI was 23.35 ± 4.18 kg/m2. Participants were from various cities in the Xizang Autonomous Region, including Lhasa 376 (32.6%), Shannan 95 (8.2%), Nyingchi 42 (3.6%), Shigatse 227 (19.7%), Chamdo 120 (10.4%), Nagqu 267 (23.1%), and Ngari 27 (2.3%). The altitude distribution of participants' residential areas was as follows: 2000-3000 m in 57 (4.9%), 3000-4000 m in 426 (36.9%), 4000-5000 m in 654 (56.7%), and > 5000 m in 17 (1.5%). A history of smoking was reported by 170 participants (14.7%). A family history of CRC was present in 95 participants (8.2%). Based on the China Risk Score for Sporadic CRC, 1034 participants (89.6%) were classified as low risk, and 120 (10.4%) as high risk. According to the Asia-Pacific Risk Score for CRC, 531 participants (46.0%) were at average risk, 508 participants (44.0%) at moderate risk, and 115 participants (10.0%) at high risk. Key demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

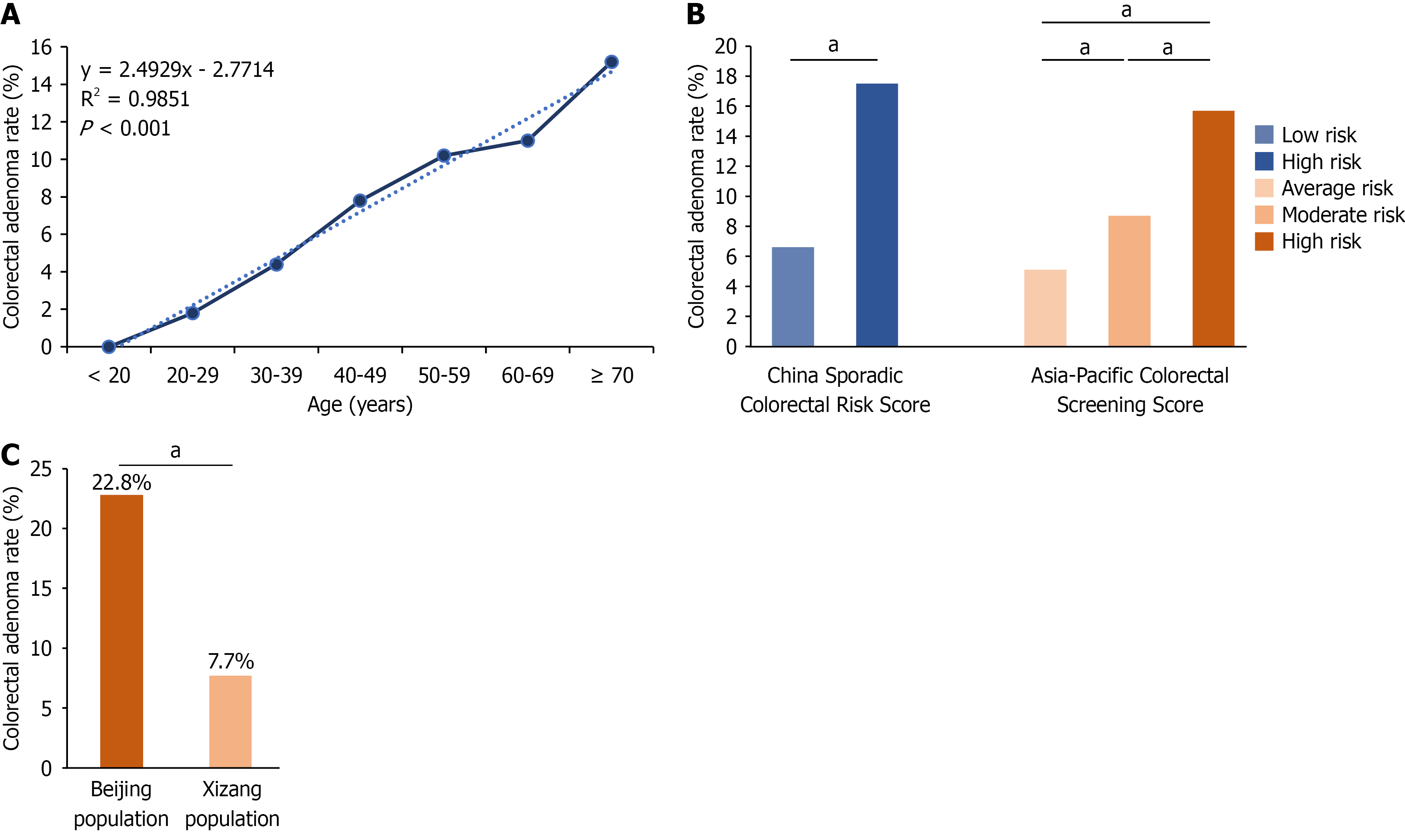

Participants were divided into two groups: 89 in the CRA group and 1065 in the healthy group. Univariate comparisons between the two groups were performed (Table 1). With regard to age, the CRA group was significantly older than the healthy group (52.70 ± 13.03 years vs 45.97 ± 14.17 years; P < 0.001). Significant differences in age distribution were observed between the two groups. The detection rate of CRA was significantly different across different age groups (P < 0.01; Supplementary Table 4), and a linear trend test revealed that the detection rate of CRA significantly increased with age (R2 = 0.9851, P < 0.01; Figure 1A). The BMI of the CRA group was significantly higher than that of the healthy group (24.91 ± 3.54 kg/m2vs 24.30 ± 4.22 kg/m2, P < 0.042). The number of individuals at high risk, according to the China Risk Score for Sporadic CRC and the Asia-Pacific Risk Score for CRC, was significantly higher in the CRA group compared to the healthy group (P < 0.01) and the risk level showed a positive correlation with CRA (Figure 1B). No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of city of residence, altitude, smoking history, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of abdominal surgery, or family history of CRC (P > 0.05). Patients were also divided into the CRC group (n = 18) and control group (n = 1136) and univariate comparisons were performed (Supplementary Table 5).

| Colorectal adenoma group (n = 89) | Healthy group (n = 1065) | Statistic (t/χ²/z) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 52.70 ± 13.03 | 45.97 ± 14.17 | -4.294 | < 0.001 |

| Age distribution (year) | 19.924 | < 0.001 | ||

| < 40 | 14 (15.7) | 387 (36.3) | ||

| 40-49 | 21 (23.6) | 248 (23.3) | ||

| 50-59 | 26 (29.2) | 229 (21.5) | ||

| ≥ 60-69 | 28 (31.5) | 201 (18.9) | ||

| Sex | 13.383 | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 61 (68.5) | 515 (48.4) | ||

| Female | 28 (31.5) | 550 (51.6) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.91 ± 3.54 | 24.30 ± 4.22 | -2.038 | 0.042 |

| BMI > 24.9 kg/m2 | 2.521 | 0.112 | ||

| No | 46 (51.7) | 642 (60.3) | ||

| Yes | 43 (48.3) | 423 (39.7) | ||

| Residence | 2.745 | 0.840 | ||

| Lhasa | 35 (39.3) | 341 (32.0) | ||

| Shannan | 8 (9.0) | 87 (8.2) | ||

| Nyingchi | 3 (3.4) | 39 (3.7) | ||

| Shigatse | 17 (19.1) | 210 (19.7) | ||

| Chamdo | 8 (9.0) | 112 (10.5) | ||

| Nagqu | 16 (18.0) | 251 (23.6) | ||

| Ngari | 2 (2.2) | 25 (2.3) | ||

| Altitude of residence (m) | 4.236 | 0.237 | ||

| 2000-3000 | 1 (1.1) | 56 (5.3) | ||

| 3000-4000 | 38 (42.7) | 388 (36.4) | ||

| 4000-5000 | 48 (54.0) | 606 (56.9) | ||

| > 5000 | 2 (2.2) | 15 (1.4) | ||

| Smoking history | 3.361 | 0.067 | ||

| No | 70 (78.7) | 914 (85.5) | ||

| Yes | 19 (21.3) | 151 (14.2) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.010 | 0.920 | ||

| No | 82 (92.1) | 978 (91.8) | ||

| Yes | 7 (7.9) | 87 (8.2) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.290 | 0.590 | ||

| No | 86 (96.6) | 1039 (97.6) | ||

| Yes | 3 (3.4) | 26 (2.4) | ||

| History of abdominal surgery | 0.038 | 0.846 | ||

| No | 80 (90.0) | 964 (90.5) | ||

| Yes | 8 (9.0) | 101 (9.5) | ||

| Family history of CRC | 0.017 | 0.896 | ||

| No | 82 (92.1) | 977 (91.7) | ||

| Yes | 7 (7.9) | 88 (8.3) | ||

| China risk score for sporadic CRC | 18.026 | < 0.001 | ||

| Low risk | 68 (76.4) | 966 (90.7) | ||

| High risk | 21 (23.6) | 99 (9.3) | ||

| Asia-Pacific risk score for CRC | 15.980 | < 0.001 | ||

| Average risk | 27 (30.3) | 504 (47.3) | ||

| Moderate risk | 44 (49.4) | 464 (43.6) | ||

| High risk | 18 (20.2) | 97 (9.1) |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict the independent risk factors for CRA in the population (Table 2). Age (OR = 1.035, 95%CI: 1.019-1.052, P < 0.001) and male sex (OR = 2.161, 95%CI: 1.337-3.492, P = 0.002) were found to be independent risk factors. Other factors, including BMI, altitude, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and family history of CRC, were not significant (P > 0.05).

| Predictor variables | B | SE | Wald | df | P value | OR | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Age | 0.034 | 0.008 | 17.782 | 1 | < 0.001 | 1.035 | 1.019 | 1.052 |

| Body mass index | 0.036 | 0.027 | 1.809 | 1 | 0.179 | 1.037 | 0.984 | 1.092 |

| Sex (male) | 0.770 | 0.245 | 9.904 | 1 | 0.002 | 2.161 | 1.337 | 3.492 |

| Altitude (m) | 3.942 | 3 | 0.268 | |||||

| 3000-4000 | 1.703 | 1.030 | 2.733 | 1 | 0.098 | 5.491 | 0.729 | 41.348 |

| 4000-5000 | 1.511 | 1.029 | 2.155 | 1 | 0.142 | 4.530 | 0.603 | 34.035 |

| > 5000 | 2.279 | 1.275 | 3.196 | 1 | 0.074 | 9.768 | 0.803 | 118.826 |

| Smoking history (yes) | 0.455 | 0.291 | 2.440 | 1 | 0.118 | 1.576 | 0.890 | 2.790 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes) | -0.189 | 0.639 | 0.087 | 1 | 0.767 | 0.828 | 0.237 | 2.895 |

| Family history of colorectal cancer (yes) | 0.010 | 0.422 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.981 | 1.010 | 0.422 | 2.308 |

To investigate CRA in different high-altitude regions, we conducted subgroup analyses on populations residing at 3000-4000 m and 4000-5000 m. Univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression were performed for each subgroup (Supplementary Tables 6-9). In the population residing at 3000-4000 m, age was identified as an independent risk factor (OR = 1.042, 95%CI: 1.017-1.068, P < 0.001). For the population residing at 4000-5000 m, age (OR = 1.025, 95%CI: 1.003-1.048, P = 0.024) and male sex (OR = 3.249, 95%CI: 1.609-6.563, P = 0.001) were independent risk factors.

To investigate potential differences in colorectal lesion detection rates influenced by geographical and altitude factors, we conducted a 1:2 matching analysis between Tibetan patients and those from the PUMCH cohort, matched by age, sex, BMI, and family history of CRC. The detection rate of CRA was significantly lower among Tibetan patients compared to the Beijing group (7.7% vs 22.8%, P < 0.001; Table 3 and Figure 1C). The detection rate of CRC showed no significant difference between the two groups (1.6% vs 1.3%, P = 0.626; Supplementary Table 10).

| Study population | Beijing population | Xizang Autonomous Region population | Statistic | P value | |

| Groups | 120.64 | < 0.001 | |||

| Healthy group | 2847 (82.2) | 1782 (77.2) | 1065 (92.3) | ||

| Colorectal adenoma group | 615 (17.8) | 526 (22.8) | 89 (7.7) |

This study presents the first systematic epidemiological investigation of colorectal lesions in the high-altitude population of Xizang Autonomous Region, coupled with a direct comparison with a low-altitude urban population. Our findings confirm that in this unique population, established risk factors such as advanced age and male sex are also significant predictors for the development of CRA. Comparative analysis revealed that the CRA detection rate in the Xizang Au

The analysis of risk factors within our Xizang Autonomous Region cohort provides critical insights into the characteristics of CRA development in this region. Our results identified advanced age as a potent, independent risk factor for CRA. This is consistent with the vast body of research on colorectal neoplasia worldwide, reaffirming the universal role of cellular senescence and cumulative exposure to carcinogens in the pathogenesis of CRA, regardless of geography or ethnicity[13-15]. Similarly, our study identified male sex as another significant independent risk factor. This aligns with numerous epidemiological reports that consistently document a higher detection rate of adenomas in men, potentially attributable to hormonal differences or lifestyle-related exposures more prevalent in men[16]. However, other conventional risk factors such as BMI and smoking history did not retain independent statistical significance in the multivariate regression model. This suggests that the contribution of these factors to CRA risk is minor in this specific Xizang Au

This study also revealed that the detection rate of CRA in the Xizang Autonomous Region cohort (7.7%) was substantially lower than that in the Beijing cohort (22.8%). This disparity was identified after a rigorous 1:2 matching protocol for age, sex, BMI, and family history, which suggests the existence of region-specific protective factors. Potential reasons for the reduced incidence of CRA could include adaptive genetic changes in the long-term high-altitude population, as well as alterations in the gut microbiome resulting from the unique high-altitude environment and diet, which is worthy of future in-depth investigation[17]. Concurrently, we found no significant difference in the detection rates of CRC between the two groups. We posit that this phenomenon can be reasonably explained from a clinical practice perspective. In Xi

The low detection rate of CRA in high-altitude populations presents a compelling area for further investigation. It was reported that the age-standardized mortality rate of CRC in the Xizang Autonomous Region is the lowest in China. Similarly, it was reported that the incidence ranking of CRC in Xizang Autonomous Region is significantly lower than in other provinces. These epidemiological findings suggest a reduced burden of colorectal neoplasia, potentially associated with unique protective factors. Genetic variations resulting from long-term adaptation to high-altitude environments may be one contributory factor. Environmental influences are also likely to play an important role. Zhao et al[18] identified dis

Despite these important findings, this study had several limitations that warrant consideration. First and foremost, the study was constrained by unmeasured confounding variables that may have influenced the observed disparity in CRA prevalence. Our matching protocol controlled for key demographic factors but did not extend to lifestyle and environmental information. Specifically, data on diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and medication use were not collected. The traditional Tibetan diet, which differs substantially from urban dietary patterns, is a plausible protective factor and represents a significant potential confounder. The inability to adjust for these variables in our models means we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding. Consequently, our hypotheses regarding the mechanisms underlying the lower CRA prevalence in Xizang Autonomous Region remain speculative and require direct validation in future research integrating detailed biological and environmental data. Second, the study design introduced potential for selection bias and limited causal inference. This was a cross-sectional study with participants recruited from single ter

This study provides the first systematic characterization of the epidemiology of colorectal lesions in the high-altitude population of Xizang Autonomous Region, and confirms the applicability of traditional risk factors such as age and sex, as well as existing risk scores, in this unique population. Using a rigorously matched comparative analysis with a low-altitude urban population, this study clearly revealed a significantly lower detection rate of CRA in the Xizang Auto

This study of 1154 individuals from a high-altitude population found detection rates of 7.7% for CRA and 1.6% for CRC, and identified advanced age and male sex as independent risk factors for CRA. In comparison with a rigorously matched low-altitude urban cohort, the CRA detection rate in the Xizang Autonomous Region population was significantly lower. This study is limited by the recruitment of Tibetans from a single tertiary hospital in Xizang Autonomous Region, which may have introduced selection bias and could limit the generalizability of findings to the broader high-altitude popu

| 1. | Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394:1467-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1570] [Cited by in RCA: 3406] [Article Influence: 486.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:713-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in RCA: 1768] [Article Influence: 252.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Qu R, Ma Y, Zhang Z, Fu W. Increasing burden of colorectal cancer in China. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jiang D, Zhang L, Liu W, Ding Y, Yin J, Ren R, Li Q, Chen Y, Shen J, Tan X, Zhang H, Cao G. Trends in cancer mortality in China from 2004 to 2018: A nationwide longitudinal study. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41:1024-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Løberg M, Zauber AG, Regula J, Kuipers EJ, Hernán MA, McFadden E, Sunde A, Kalager M, Dekker E, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Garborg K, Rupinski M, Spaander MC, Bugajski M, Høie O, Stefansson T, Hoff G, Adami HO; Nordic-European Initiative on Colorectal Cancer (NordICC) Study Group. Population-Based Colonoscopy Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:894-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mahmood K, Thomas M, Qu C; Gecco-Ccfr Consortium, Hsu L, Buchanan DD, Peters U. Elucidating the Risk of Colorectal Cancer for Variants in Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Genes. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1070-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Patel SG, Karlitz JJ, Yen T, Lieu CH, Boland CR. The rising tide of early-onset colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical features, biology, risk factors, prevention, and early detection. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:262-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 128.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 8. | Simonson TS, Yang Y, Huff CD, Yun H, Qin G, Witherspoon DJ, Bai Z, Lorenzo FR, Xing J, Jorde LB, Prchal JT, Ge R. Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science. 2010;329:72-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 755] [Cited by in RCA: 899] [Article Influence: 56.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu J, Xin Z, Huang Y, Yu J. Climate suitability assessment on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci Total Environ. 2022;816:151653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cui J, Zhaxi D, Sun X, Teng N, Wang R, Diao Y, Jin C, Chen Y, Xu X, Li X. Association of dietary pattern and Tibetan featured foods with high-altitude polycythemia in Naqu, Tibet: A 1:2 individual-matched case-control study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:946259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huang L. High altitude medicine in China in the 21st century: opportunities and challenges. Mil Med Res. 2014;1:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yeoh KG, Ho KY, Chiu HM, Zhu F, Ching JY, Wu DC, Matsuda T, Byeon JS, Lee SK, Goh KL, Sollano J, Rerknimitr R, Leong R, Tsoi K, Lin JT, Sung JJ; Asia-Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer. The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening score: a validated tool that stratifies risk for colorectal advanced neoplasia in asymptomatic Asian subjects. Gut. 2011;60:1236-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Liang PS, Shaukat A. Assessing the impact of lowering the colorectal cancer screening age to 45 years. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:523-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Patel SG, May FP, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Gross SA, Jacobson BC, Shaukat A, Robertson DJ. Updates on Age to Start and Stop Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations From the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:285-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kehm RD, Lima SM, Swett K, Mueller L, Yang W, Gonsalves L, Terry MB. Age-specific Trends in Colorectal Cancer Incidence for Women and Men, 1935-2017. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1060-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu Z, Huang Y, Zhang R, Zheng C, You F, Wang M, Xiao C, Li X. Sex differences in colorectal cancer: with a focus on sex hormone-gut microbiome axis. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22:167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zheng W, He Y, Guo Y, Yue T, Zhang H, Li J, Zhou B, Zeng X, Li L, Wang B, Cao J, Chen L, Li C, Li H, Cui C, Bai C, Baimakangzhuo, Qi X, Ouzhuluobu, Su B. Large-scale genome sequencing redefines the genetic footprints of high-altitude adaptation in Tibetans. Genome Biol. 2023;24:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhao H, Sun L, Liu J, Shi B, Zhang Y, Qu-Zong CR, Dorji T, Wang T, Yuan H, Yang J. Meta-analysis identifying gut microbial biomarkers of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau populations and the functionality of microbiota-derived butyrate in high-altitude adaptation. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2350151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Guo X, Long R, Kreuzer M, Ding L, Shang Z, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Cui G. Importance of functional ingredients in yak milk-derived food on health of Tibetan nomads living under high-altitude stress: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54:292-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu J, Yu C, Li R, Liu K, Jin G, Ge R, Tang F, Cui S. High-altitude Tibetan fermented milk ameliorated cognitive dysfunction by modified gut microbiota in Alzheimer's disease transgenic mice. Food Funct. 2020;11:5308-5319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/