Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115974

Revised: November 15, 2025

Accepted: December 8, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 96 Days and 14.3 Hours

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, particularly colorectal cancer, continue to be a major contributor to global cancer-related morbidity and mortality. Despite significant advancements in screening protocols and treatment strategies, early detection remains a clinical challenge due to the limitations of conventional diagnostic tools, which often suffer from inter-observer variability, limited sensitivity, and time-intensive procedures. In recent years the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), especially deep learning (DL) techniques, into medical diagnostics has opened new frontiers for enhancing detection accuracy, speed, and consistency across clinical domains. This review explores the transformative impact of DL-based AI models in detecting lower GI cancers, focusing on three key diagnostic modalities: Endoscopy; radiology; and histopathology. In endoscopic practice convolutional neural networks are used to detect and classify colorectal polyps in real-time, significantly reducing miss rates and aiding non-specialist endoscopists in decision-making. In radiology DL algorithms trained on computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging data are valuable for automated lesion detection, segmentation, and staging, often outperforming conventional imaging. Histopathological analysis, traditionally reliant on manual examination, is now accelerated by DL models capable of processing whole-slide images to identify architectural distortions and cellular anomalies with high reproducibility and diagnostic accuracy. This review evaluates DL model perfor

Core Tip: Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, is revolutionizing gastrointestinal oncology by enhancing early detection, diagnostic precision, prognostication, and personalized treatment. Deep learning models such as convolutional neural networks improve polyp detection, automate tumor segmentation, and interpret histopathology with high accuracy. Emerging multimodal and explainable AI frameworks integrate imaging, molecular, and clinical data, fostering precision oncology. Despite challenges of data heterogeneity and generalizability, the synergy between AI and clinicians promises earlier diagnosis, individualized therapy, and improved outcomes in lower gastrointestinal cancers.

- Citation: Sehgal T, Joshi T, Chowdhary R, Goyal O, Kalra S, Goyal R, Taranikanti V, Vuthaluru AR, Goyal MK. Deep learning in lower gastrointestinal cancer detection: Advances in endoscopic, radiologic, and histopathologic diagnostics. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 115974

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/115974.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115974

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancer represents a major global health challenge, accounting for approximately 26% of all cancer cases and 35% of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1]. According to the latest GLOBOCAN estimates, from 2022, GI cancer accounted for an estimated 3.7 million new cases, representing 18.6% of all new cancer cases globally. These cancers were associated with 2.2 million deaths, accounting for 23.0% of all cancer-related deaths[2].

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is now the most common GI malignancy globally with over 1.9 million new cases and 930000 deaths in 2020 and is projected to reach 3.2 million new cases and 1.6 million deaths by 2040[3]. Gastric cancer remains the fifth-leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and is projected to continue posing a significant public health burden in the foreseeable future[2]. Gastric and esophageal cancers are particularly notable for their high mortality rates and varying regional patterns. Notably, the incidence of esophageal, gastric, and liver cancers is higher in Asia, whereas colorectal and pancreatic cancers are more prevalent in Europe and North America[4]. The uneven distribution of these cancers across different regions highlights the need for targeted interventions. Late diagnosis often leads to poor outcomes, underscoring the importance of early detection and effective healthcare strategies.

Despite advances in oncological therapeutics, the prognosis for many GI cancers remains poor, largely due to delayed detection and limited precision in predicting treatment response. Traditional diagnostic modalities such as endoscopy, histopathology, and radiological imaging are effective but constrained by operator dependency, interpretive variability, and the inability to capture subtle molecular or imaging features indicative of early disease. While screening programs have substantially enhanced the early detection of certain malignancies, many GI malignancies remain challenging to detect early due to a lack of effective screening methods and reliable biomarkers for staging and prognosis[5,6]. Addi

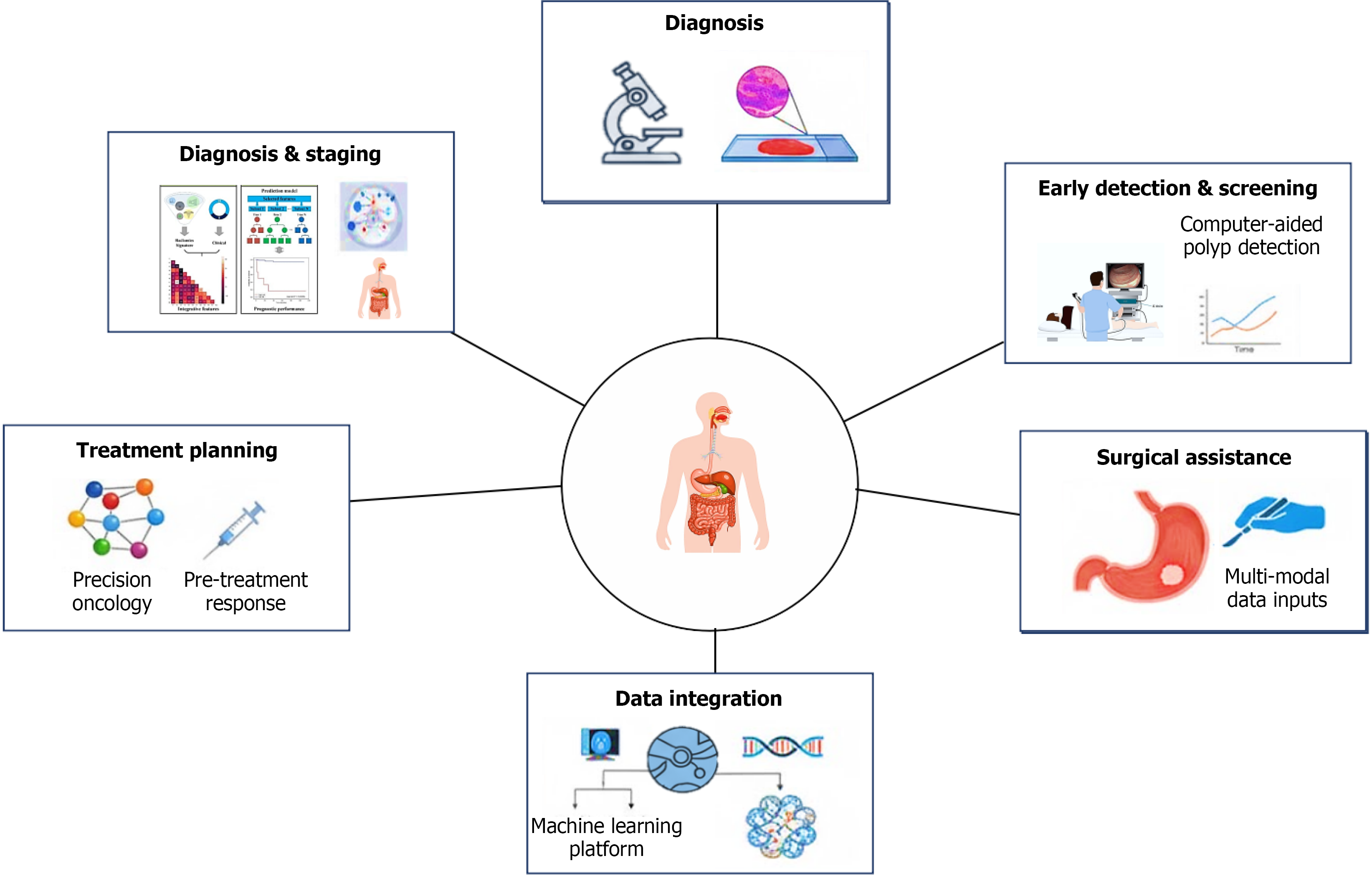

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into oncology is transforming this landscape (Figure 1). The convergence of deep learning (DL), large language models, and machine learning (ML) has driven transformative progress in GI cancer diagnosis and management[7,8]. Recent developments in AI illustrate the potential of these technologies to complement conventional diagnostics, enhance early detection, and support precision-guided treatment strategies. DL, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are trained to extract complex features from imaging data to reveal tumor patterns, differentiate between benign and malignant tumors, and predict tumor invasion depth[9,10]. Large language models assist clinical decision-making by synthesizing extensive biomedical literature, patient records, and treatment data, thus supporting updated diagnostic and therapeutic insights[11]. ML algorithms further refine individualized care by predicting disease risk, therapeutic response, and survival outcomes, thereby directly supporting precision oncology and treatment planning[11]. Collectively, these technologies enhance diagnostic precision, streamline healthcare pro

| AI technology | Type | Typical applications | Data modality | Examples |

| Convolutional neural networks[9] | Deep learning | Image classification, lesion detection, segmentation | Endoscopy, CT, MRI, ultrasound, histology | Polyp detection in colonoscopy, tumor segmentation on CT, WSI classification |

| Deep learning (radiomics/segmentation models)[17,27] | Deep learning | Temporal data analysis, prognosis prediction | Longitudinal EMR data, time-series labs | Predicting recurrence or survival in CRC or HCC |

| Transformers[21] | Deep learning (NLP) | EHR analysis, pathology report interpretation, literature mining | Text (EMRs, reports) | Extracting staging from pathology notes, summarizing clinical texts |

| Support vector machines[25] | Machine learning (supervised) | Classification tasks, small datasets | Genomics, proteomics, structured data | Classifying tumor vs normal tissues based on gene expression |

| Random forests/decision trees[39] | Machine learning (supervised) | Risk prediction, survival modeling | Clinical + demographic data | CRC risk prediction based on age, lifestyle, family history |

| Multimodal deep learning models (e.g., MuMo)[44] | Deep learning/multimodal AI | Predicting treatment response, prognostic modeling; survival prediction | Radiology (CT/MRI), pathology images, genomic/transcriptomic data, clinical variables | MuMo integrates diverse data types (radiological, pathological, and clinical information) to predict treatment responses and survival outcomes for patients with HER2-positive GC |

| Explainable AI[47] | Deep learning/explainable AI | Enhancing clinician interpretability and trust; feature attribution; transparent model reasoning | Histopathology, endoscopic images | PolypSeg-GradCAM integrates U-Net segmentation with Grad-CAM visualization for pixel-level explanation in colonoscopy; pathology explainable AI identified histological features linked to molecular subtypes or therapy response |

| Federated learning models[49,50] | Machine learning/federated learning | Multicenter model training without sharing raw patient data; improving generalizability and equity | Multi-institution clinical, imaging, and omics data | Robust federated learning model for predicting postoperative recurrence in GC outperformed clinical model and reduced misdiagnosis of local recurrence by > 40% |

| Digital twin technology[51] | Hybrid AI/simulation | Virtual patient modeling for disease trajectory simulation, treatment response, and outcome forecasting | Longitudinal clinical, imaging, and molecular data | Simulating tumor evolution and therapy outcomes for colorectal and GCs; currently in research validation stages |

In this narrative review we have synthesized the current evidence on AI applications in GI cancers, organized by the key domains of early detection and screening, diagnosis, prognosis and risk stratification, treatment planning, and precision oncology. We had performed a bibliographic search using the MEDLINE (through PubMed) database to identify studies on AI technology in GI cancer endoscopy, pathology, and radiology. This allowed us to highlight representative studies and developments in each area in this review, to illustrate how AI can overcome limitations of traditional approaches. Finally, we discuss multimodal and next-generation AI strategies, the challenges limiting clinical translation, future directions including standardization and prospective validation, and the envisioned role of AI as a complement to clinicians. By evaluating the impact of AI across the GI cancer care continuum, we aim to inform clinical practice and research efforts toward more precise and effective management of GI malignancy.

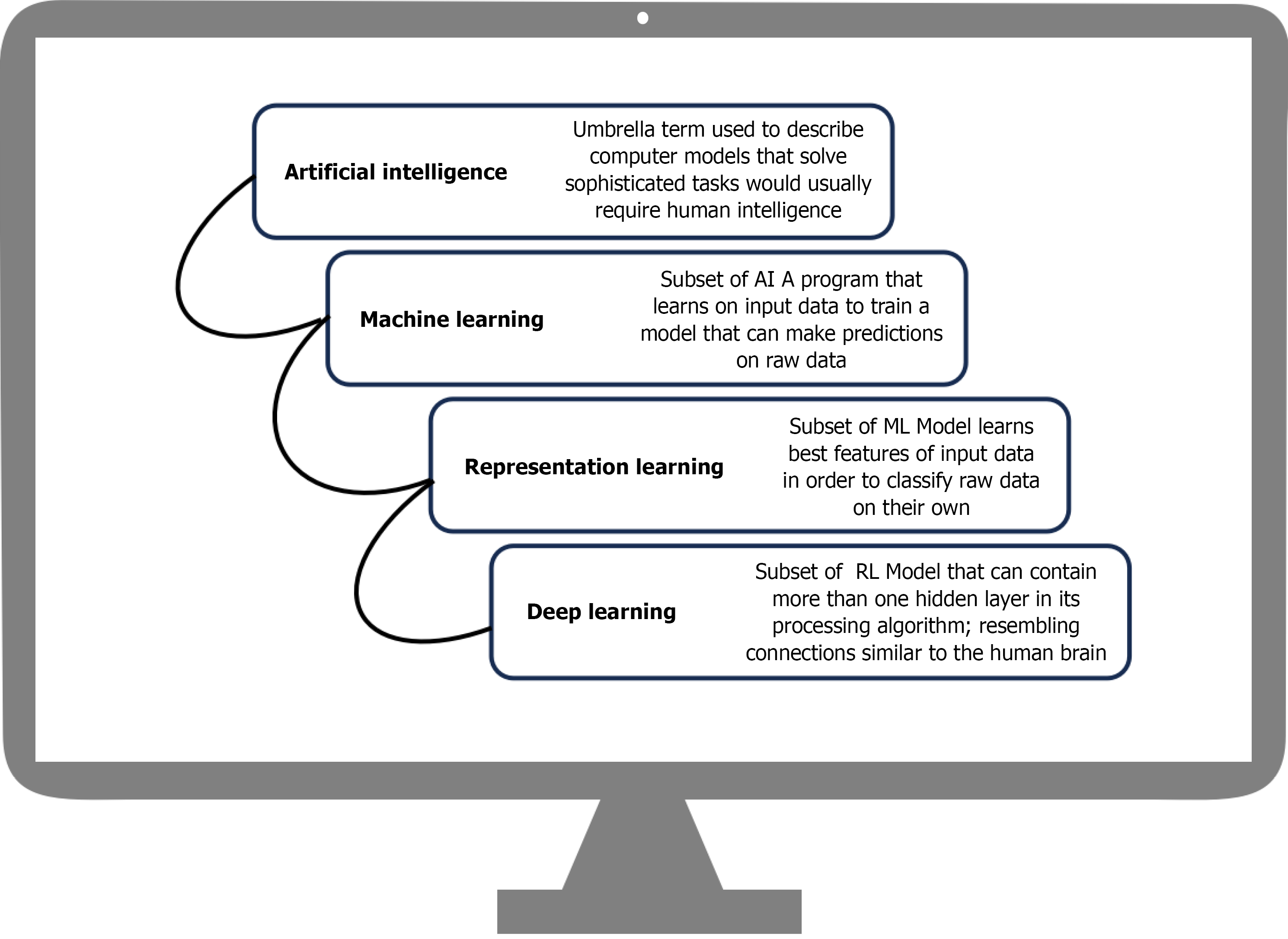

Early detection in GI cancers refers to the identification of neoplastic or preneoplastic alterations before the onset of invasive disease. Better prognostic outcomes, the ability to use minimally invasive interventions, and eventually a decrease in mortality all depend on the early detection of malignancies. In recent years AI-driven algorithms have emerged as powerful tools in this domain, demonstrating promise in identifying premalignant polyps. These algorithms can also help with prognostic evaluation by forecasting variables like treatment response and lymph node metastasis in addition to increasing the diagnostic accuracy of CRC[12]. AI enhances human diagnostic capabilities by improving accuracy, speed, and consistency across modalities ranging from endoscopic imaging and radiologic scans to noninvasive biomarker testing and population-level risk prediction models. An example of the hierarchical relationship of AI subfields is shown in Figure 2.

Endoscopic detection remains the gold standard test for early detection and screening of GI carcinomas, particularly in CRC and gastric malignancies. The diagnostic yield of endoscopy is dependent on the operator; hence, the chances of missing the diagnosis of subtle, diminutive, and flat lesions cannot be overlooked, contributing to missed cancers. These limitations have accelerated the integration of AI-based systems into endoscopic practice. To enhance the detection accuracy, computer-aided detection (CADe) systems based on algorithms have been developed. These models analyze endoscopic video feeds in real time, highlighting suspicious mucosal regions suggestive of polyps, neoplasia, or dysplasia. Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that these systems substantially improve adenoma detection rates and reduce miss rates for small or flat lesions.

AI-powered CADe and computer-aided diagnosis systems have transformed early detection in GI oncology, particularly within endoscopic practices. In CRC screening CADe systems integrated into colonoscopy have consistently increased adenoma detection rates. A meta-analysis of five RCTs (n = 4354) showed that CADe-assisted colonoscopy significantly improved adenoma detection rate [36.6% vs 25.2%; relative risk: 1.44, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.27-1.62] and adenomas per colonoscopy (relative risk: 1.70, 95%CI: 1.53-1.89) compared with standard colonoscopy. Gains were consistent across all polyp sizes and morphologies, supporting CADe as an effective tool to enhance CRC screening accuracy[13].

Similarly, in upper GI neoplasia AI-based CADe and computer-aided diagnosis systems have demonstrated stand-alone sensitivities between 83% and 93% for detecting esophageal squamous cell neoplasia, Barrett’s esophagus-related neoplasia, and early gastric cancer in technical validation studies. DL models, particularly CNNs, have achieved sensitivities up to 95.3% and area under the curve (AUC) values as high as 0.981 for early gastric cancer detection, often surpassing expert endoscopists. These models not only enhance diagnostic sensitivity but also reduce interobserver variability and minimize diagnostic miss rates, addressing one of the key limitations of human-dependent endoscopic assessment. These advancements position AI as a critical adjunct in precision endoscopy, bridging the gap between detection and characterization of GI neoplasia.

Beyond endoscopy, radiomics has emerged as another transformative AI-driven approach for early cancer detection and characterization. Radiomics involves the extraction and quantitative analysis of high-dimensional features from imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography. It is useful in transforming standard images into measurable data that reflect underlying tumor biological characteristics. Radiomics integrates quantitative features with clinical features, increasing its accuracy in detecting differences between malignant and benign lymph nodes[14-16].

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 36 studies involving 8039 patients reported that radiomics-based models predicting lymph node metastasis in CRC and rectal cancer achieved a pooled AUC of 0.81 (95%CI: 0.78-0.85) with corresponding sensitivity and specificity of 0.77 and 0.73, respectively. Performance was comparable between CT-based and MRI-based models though rectal cancer models showed slightly superior accuracy. Radiomics significantly outperformed radiologists (AUC = 0.814 vs 0.659, P < 0.001), underscoring its potential as a reliable adjunct in preoperative staging and individualized treatment planning[17]. However, the clinical translation of radiomics remains challenged by inter-scanner variability, differences in segmentation methods, and the need for standardized data harmonization.

Noninvasive diagnostic tests play a pivotal role in cancer detection owing to their safety and higher patient acceptability compared with invasive approaches. Liquid biopsies, including circulating tumor cells, circulating tumor DNA, and exosomal RNAs, are novel targets for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy monitoring. Meanwhile, the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) remains one of the most widely used noninvasive screening tools for CRC. A meta-analysis of 31 studies including 120255 participants reported a pooled sensitivity of approximately 40% (33%-47%) for detecting CRC compared with colonoscopy in individuals with average risk[18]. Another meta-analysis evaluating the performance of FIT in detecting adenomatous lesions reported a lower sensitivity of 27% (23%-31%). These findings suggest that while FIT is effective for population-level screening, its limited sensitivity for adenomas underscores the need for complementary diagnostic approaches[19]. Overall, these noninvasive tests can serve both as screening methods for large populations and as a test to determine who should undergo more definitive diagnostic evaluations.

Building on these advances, AI-driven risk prediction models leveraging electronic health record data are being developed to identify individuals at high risk and optimize screening strategies. By integrating demographic, clinical, and laboratory features, these models help prioritize who should receive further evaluation. Though promising they still require thorough validation before broad adoption.

Accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective GI cancer management. Traditional diagnostic approaches such as histopathology and imaging although indispensable are limited by interobserver variability and subjective interpretation. AI offers a solution to these limitations. Specifically, ML and DL algorithms are being increasingly explored to improve prognostication and predict treatment response in GI cancers. However, these models still require more robust validation, particularly using whole-slide imaging and by integrating multiple data types (multimodal data)[20]. These systems have improved precision in cancer detection, classification, and risk stratification, supporting more personalized interventions.

DL architectures, especially CNNs, have demonstrated exceptional performance in the automated classification of dysplasia and cancer across GI malignancies. In gastric cancer the StoHisNet model achieved over 94% accuracy and high F1 scores in multiclass histopathological image classification, highlighting the potential of AI to reduce diagnostic subjectivity[21]. Similar models are being applied to CRC and esophageal neoplasia in which AI-assisted grading of precancerous lesions enables earlier intervention and standardized diagnostic workflows. AI reduces interobserver variation but demands workflow standardization, clinician training and cost-benefit evidence before routine imple

In radiology, AI supports both quantitative characterization and decision augmentation rather than simple image interpretation. Automated segmentation and radiomics extract high-dimensional features from standard imaging (CT, MRI, positron emission tomography) to characterize tumor heterogeneity and biology without invasive sampling. Beyond morphological detection, these features have shown potential for risk stratification, correlating with molecular subtypes, treatment response, and recurrence patterns in colorectal and gastric cancers.

In hepatocellular carcinoma AI models have improved detection of small lesions, prediction of microvascular invasion, and assessment of resectability. In pancreatic and biliary cancers, AI-driven analysis of cross-sectional imaging (CT, MRI) has enhanced identification of ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and biliary strictures, supporting early diagnosis and personalized treatment planning[22]. These advances are particularly valuable in rare and diagnostically challenging cancers, such as cholangiocarcinoma and small intestine tumors, in which AI can integrate radiological, endoscopic, and pathological data to improve detection and guide multidisciplinary management. By automating segmentation and quantifying subtle imaging features invisible to the human eye, AI enhances radiological consistency and supports personalized treatment planning.

AI also facilitates integrative molecular diagnosis by efficiently analyzing large-scale genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets. While radiomics captures phenotypic variation from imaging, molecular AI focuses on the tumor’s genetic and transcriptomic landscape. ML algorithms can identify key mutational signatures, classify molecular subtypes, and predict treatment response and prognosis. AI has also advanced molecular profiling by integrating imaging and multiomics data to identify causative markers.

A particularly notable application is the prediction of microsatellite instability, a pan-cancer biomarker predictive of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, which has been effectively predicted by AI-based histopathology analysis. An Ensembled Patch Likelihood Aggregation system achieved AUCs of 0.88 and 0.85 for microsatellite instability prediction from digital slides. It linked pathological image features to mutation burden, DNA repair pathways, and immune activation, guiding targeted therapy and patient stratification[23]. Multimodal diagnostic frameworks that combine imaging, histopathology, and molecular data consistently outperform single-modality approaches, enabling more precise diagnosis and risk stratification.

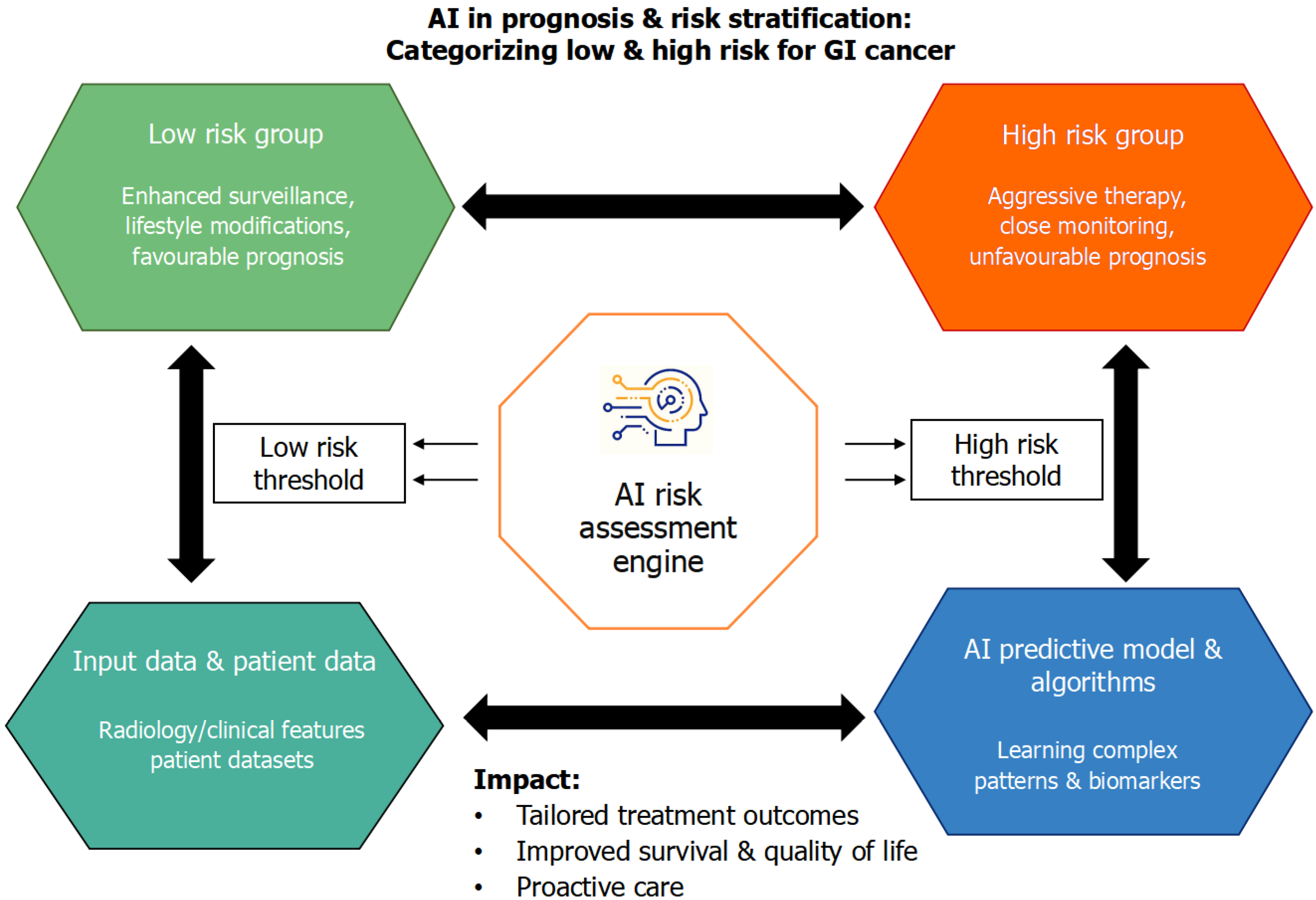

Beyond diagnosis, AI plays a pivotal role in prognostication and risk stratification, offering data-driven insights into recurrence, survival, and treatment outcomes that guide personalized management in GI cancers as shown in Figure 3. A DL model integrating preoperative CT images demonstrated high accuracy in predicting peritoneal recurrence and disease-free survival in gastric cancer (AUC = 0.84-0.86). This model not only improved interobserver consistency among oncologists but also stratified patients based on recurrence risk, aiding individualized chemotherapy decisions. Still, model interpretability remains limited and clinicians often face difficulty understanding the rationale behind AI-generated risk classification. Such AI-driven prognostic tools exemplify precision risk assessment in GI oncology[24]. Using this method further, ML frameworks for CRC have demonstrated potential in forecasting the occurrence of second primary malignancies as well as tumor recurrence. With accuracy rates close to 88%, support vector machine-based models made it possible to implement proactive follow-up and secondary prevention techniques[25].

AI-driven multiparametric models integrating histological, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data have also advanced prognostic modelling in pancreatic cancer. These systems predicted organ-specific relapse and metastatic risk with approximately 78% accuracy, facilitating tailored treatment and surveillance planning[26]. Despite promising accuracy, most pancreatic cancer models lack real-world clinical testing and often omit external datasets for independent evaluations. Conventional prognostic indices such as tumor node metastasis staging are clinically useful but fail to capture tumor microenvironmental heterogeneity, a key determinant of disease progression and therapeutic response. To address this, recent studies have combined immunologic and radiomic features into AI-enhanced prognostic tools. The tumor node metastasis staging system was outperformed (P < 0.01) by a radiomic immunoscore-based nomogram that combined immunological profiling and radiomics features to achieve superior predictive performance for overall survival in gastric cancer with AUCs up to 0.85 for prognosis prediction. Significantly, adjuvant chemotherapy was more beneficial for patients in the high nomogram group, highlighting the clinical value of AI-enhanced models for customized treatment planning[27].

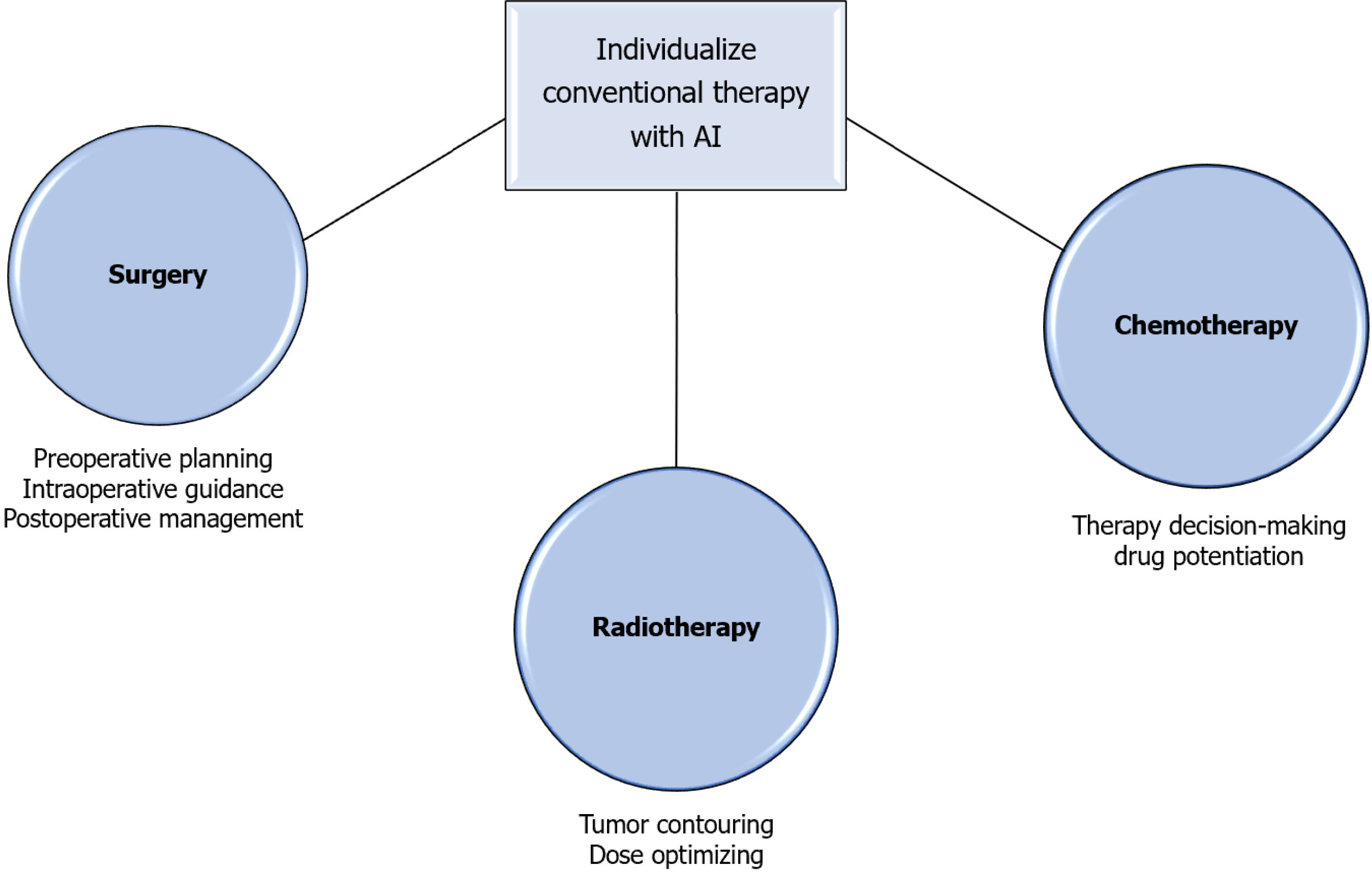

AI is increasingly applied to support treatment planning in GI oncology, including surgical and endoscopic navigation, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy selection. In surgery and endoscopy AI systems provide real-time guidance for lesion localization, margin assessment, and resectability, improving procedural accuracy and outcomes. In radiotherapy AI-driven automated contouring and dose optimization have streamlined planning and reduced inter-operator variability.

The majority of prognostic AI models are still retrospective and single-center, restricting their generalizability even with their encouraging performance. Important next steps include standardizing data inputs, integrating them into clinical workflows, and obtaining external validation. For reliable and comprehensible prognostication, future research should focus on multimodal models that integrate imaging, histopathology, and molecular data.

The use of AI in precision oncology and treatment planning represents a revolutionary development in the treatment of GI cancer as it continues to advance beyond diagnostic and prognostic applications. AI systems now help physicians with surgical navigation, radiotherapy optimization, and therapeutic response prediction by utilizing multimodal data from imaging, genomics, histopathology, and clinical records. Together, these applications improve treatment precision, reduce side effects, and tailor therapy to the unique tumor biology of each patient as seen in Figure 4.

AI is revolutionizing robotic and minimally invasive CRC surgery by improving intraoperative safety, accuracy, and visualization. To identify anatomical landmarks and improve surgical workflow analysis, computer vision algorithms trained on massive datasets of laparoscopic videos have been used[28]. CNNs showed promise in automating intraoperative phase recognition and skill evaluation after being trained on more than 300 videos of laparoscopic CRC surgery[29]. Anastomotic viability assessment has been supported by AI-assisted analysis of indocyanine green angiography, which has made it possible to evaluate perfusion more precisely through virtual microcirculation modeling[30].

Another example of integrating AI into operative guidance is robotic surgery, especially with the Da Vinci system. In complex procedures like transanal total mesorectal excision, the most recent generation of systems provides improved visualization, tremor filtration, and precision. Additionally, image-guided navigation tools, like flat image mapping systems, are being developed to help identify important anatomical structures during total mesorectal excision. Long operating times, high expenses, and little sensory feedback are some of the present drawbacks; however, continued technological advancement and cost savings should enable wider clinical adoption[31-33]. Economic feasibility and surgeon acceptance will ultimately determine the practical value of these AI-guided systems.

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NCRT) strategies for CRC are being optimized with the help of AI-based clinical decision support systems. Accurate risk stratification is essential to avoid overtreatment because adjuvant chemotherapy only benefits a subset of patients with rectal cancer[34]. Data-driven clinical decision support systems and DL have shown promise in improving treatment choices. For example, using real-world clinical data, a South Korean research team created an AI-based chemotherapy recommender that achieved high predictive accuracy (AUC > 0.95). The DoMore-v1-CRC DL-based marker for postoperative risk classification was deemed low risk and could safely avoid NCRT with noticeably better survival results[35]. AI also helps with prognosis evaluation and treatment response prediction. For patients with locally advanced rectal cancer undergoing NCRT, DL-assisted MRI analysis allowed for the early prediction of metastases[36,37]. Long noncoding RNA expression profiles were used by Ferrando et al[38] in a different method to forecast therapeutic response, and they achieved strong predictive performance (AUC = 0.93). The goal of personalized oncology is advanced by combining these molecular biomarkers with computational modelling to provide a noninvasive framework for predicting drug resistance and the effectiveness of chemoradiotherapy.

AI is proving to be a useful tool in overcoming treatment challenges for CRC, especially DL and simpler models like random forests. The noninvasive prediction of BRAF and KRAS gene mutations, which are essential for successful targeted therapies, has proven to be a major challenge[39]. For example, a residual neural network model performed well in predicting KRAS mutations (AUC = 0.90), whereas a more straightforward random forest model was able to correctly predict the BRAF V600E mutation[40].

Additionally, patients are being examined for possible drug resistance using AI-based predictive models; one study found that these models had an average AUC of 0.90. New drug targets, like the 144 core genes suggested by an analysis of the competitive endogenous RNA network, have also been found thanks in large part to AI[41]. These developments demonstrate how AI is facilitating early detection of genetic mutations and drug resistance, improving treatment outcomes and helping personalize medicine for patients with CRC. In summary, AI has expanded treatment personalization through surgical guidance, therapy optimization and molecular prediction. Further priorities include external validation, cross-effectiveness analysis and explainable outputs to ensure clinician trust and equitable implementation across health-care systems.

The integration of imaging, omics, and clinical data is a cornerstone of next-generation AI in GI oncology. Multimodal AI models represent a significant advancement in oncology, integrating diverse data types, including CT, MRI, histopathological images, genomic and transcriptomic profiles, and clinical variables, to provide a comprehensive understanding of tumor biology. Studies show that multimodal models outperform unimodal counterparts in survival prediction, treatment response, and prognostic accuracy across cancer types[42,43]. By fusing these heterogeneous inputs, AI models can capture complex interactions between the tumor phenotype and genotype, thereby improving diagnostic and prognostic accuracy. Real-world implementation remains limited because multimodal datasets are rarely standardized or complete and model performance often declines when applied to heterogenous external cohorts.

AI-based multimodal models have demonstrated remarkable potential in treatment response and prognosis prediction. For instance, Chen et al[44] developed the multimodal DL model MuMo to predict responses of patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive gastric cancer to anti-HER2 therapy by integrating radiological, pathological, and clinical data. MuMo achieved high predictive accuracy AUC = 0.821 for anti-HER2 therapy and 0.914 for combined anti-HER2 + anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 immunotherapy, demonstrating that multimodal integration enhances predictive power even with incomplete datasets. Multimodal integration however increases computational demand and raises missing data challenges that require imputation and harmonization strategies for reliable deployment. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is a minimally invasive intervention for liver cancer. A fully automated ML algorithm integrating CT-derived features with clinical factors to predict hepatocellular carcinoma response to TACE was evaluated and showed that a model integrating Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging with quantitative imaging features achieved a predictive accuracy of 74.2% (95%CI: 64%-82%)[45]. This underscores the potential of pretreatment quantitative imaging features for enhancing TACE efficacy prediction accuracy in liver cancer.

Beyond model accuracy, explainable AI (XAI) is increasingly incorporated to enhance clinician trust and meet regulatory approval standards. Techniques such as attention heatmap visualization and feature attribution mapping provide transparent, clinically meaningful outputs, allowing clinicians to verify and understand model reasoning. Recent GI-focused studies illustrate these benefits. PolypSeg-GradCAM integrates U-Net segmentation with Grad-CAM visualization to provide pixel-level explanations for automated polyp detection during colonoscopy, improving both segmentation performance and clinician interpretability[46]. In pathology XAI methods can identify histological features associated with specific molecular subtypes or treatment responses, facilitating informed decision-making[47].

Federated learning (FL) addresses the “data island” problem by enabling AI model training across multiple institutions without sharing raw patient data, preserving privacy and improving generalizability[48]. This approach supports the inclusion of rare GI malignancies and underrepresented populations, addressing key equity concerns in cancer care[48,49]. One study found that a robust FL model (commonly referred to as RFLM) for predicting postoperative recurrence in gastric cancer showed greater diagnostic efficiency and significantly outperformed a clinical model when applied to data from four different medical centers. In the same study the RFLM successfully reduced the misdiagnosis rate of local recurrence by over 40%[50].

Digital twin technology represents a frontier in precision oncology, creating virtual representations of individual patients that simulate disease trajectories, treatment responses, and potential outcomes. Recent reviews and proof-of-concept studies have focused on digital twin applications across multiple malignancies, including CRC and other GI cancers, and described frameworks for integrating mechanistic models with ML to forecast tumor trajectories and optimize treatment schedules[51]. However, practical implementation faces the following challenges: Assembling high-quality longitudinal data; validating twin predictions prospectively; and addressing substantial computational and regulatory requirements; all of which remain active areas of research[51].

The clinical implementation of AI in GI oncology faces significant challenges related to data heterogeneity, annotation requirements, and generalizability. A major limitation is model generalizability. AI systems developed and validated in high-volume, specialized centers may perform suboptimally when applied to diverse patient populations, including underrepresented groups and rare cancer subtypes, raising concerns about external validity[52,53]. Differences in imaging protocols, equipment, and annotation standards further complicate model performance across institutions.

Algorithmic bias represents another critical concern as biases introduced during data collection, annotation, model development, or deployment can exacerbate existing health disparities. Mitigating these risks requires curated, representative datasets, transparent model development processes, and equity-focused validation studies[53,54]. The “black box” nature of many DL models further impedes interpretability and clinician trust, posing barriers to regulatory approval. XAI frameworks are emerging as a solution, providing interpretable outputs that enable clinicians to understand predictions, identify potential errors, and make informed decisions[46,47,54].

Regulatory and ethical issues include the lack of standardized endpoints for clinical trials evaluating AI tools, the need for rigorous prospective validation, and unresolved questions of liability in the event of adverse outcomes. The regulatory landscape is evolving but remains unchanged with traditional frameworks not fully equipped to evaluate the dynamic, adaptive nature of AI algorithms[54,55].

Data privacy, security, and informed consent are additional concerns as AI systems rely on large-scale, multicenter datasets for robust model training and validation[56]. Approaches such as FL can mitigate these risks by enabling collaborative model development without sharing raw patient data, preserving confidentiality while enhancing generalizability. Ensuring compliance with data protection regulations and implementing robust cybersecurity measures are prerequisites for ethical deployment[48,56].

Workflow integration and clinician training are practical challenges as AI tools must be seamlessly incorporated into existing clinical protocols and electronic health record systems. Despite these challenges AI retains transformative potential in GI oncology. By integrating multimodal data, including imaging, genomics, and clinical insights, AI can enhance early detection, improve prognostication, guide personalized treatment planning, and deepen our understanding of tumor biology, treatment strategies, and patient outcomes.

Standardized reporting frameworks, such as CONSORT-AI and TRIPOD-AI, are essential for ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and comparability in AI research[57,58]. Evidence indicates that adherence to these guidelines remains suboptimal with systematic reviews finding variable reporting quality and limited external validation in published RCTs. The APPRAISE-AI tool provides a quantitative measure of methodological and reporting quality, supplementing existing guidelines and informing regulatory and funding decisions[59].

Prospective validation and multicenter trials are critical for confirming the benefits of AI-assisted care compared with conventional approaches. Most existing RCTs in GI oncology remain single-center with narrow demographic representation and heterogeneous endpoints, raising concerns about generalizability[60,61]. Multicenter studies enable the development of standardized datasets, facilitate external validation, and improve model robustness across diverse patient populations and clinical settings.

Integration of AI into clinical guidelines is most advanced in the field of endoscopic detection and characterization. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy now recommends that AI-assisted diagnostic and management systems achieve performance at least equivalent to that of experienced endoscopists, without increasing operator reading time and ideally reducing it[62]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy further emphasizes the importance of continuous post-deployment monitoring for algorithmic bias, equity-focused validation, and periodic model updates to maintain safety and reliability.

AI-human synergy models in which clinicians and AI systems collaborate in real-time, consistently demonstrate superior diagnostic accuracy and workflow efficiency compared with clinician-only assessment[63]. Successful im

AI is transforming GI oncology by enhancing early detection, diagnostic accuracy, risk stratification, and personalized treatment planning across all major GI cancers. The unique suitability of AI for GI oncology is grounded in the reliance of the specialty on high-volume imaging, structured datasets, and the complexity of multimodal data.

Robust evidence from RCTs, technical validation studies, and expert consensus highlights that AI functions as a complementary tool, augmenting rather than replacing clinician expertise. By reducing interobserver variability and improving diagnostic consistency, AI contributes to more reliable clinical decision-making and improved patient outcomes.

Responsible and effective adoption of AI necessitates rigorous prospective validation and sustained interdisciplinary collaboration between clinicians, data scientists, and engineers. As AI technologies mature, including multimodal integration, XAI, FL, and digital twins, the scope of clinical utility will expand, further enhancing precision medicine and healthcare equity in GI oncology. The future of GI cancer care will be defined by the synergistic integration of AI and human expertise, supported by collaborative research and continuous guideline updates to ensure safe, effective, and equitable implementation.

| 1. | Wong ANN, He Z, Leung KL, To CCK, Wong CY, Wong SCC, Yoo JS, Chan CKR, Chan AZ, Lacambra MD, Yeung MHY. Current Developments of Artificial Intelligence in Digital Pathology and Its Future Clinical Applications in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:3780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12561] [Article Influence: 6280.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 3. | Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72:338-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in RCA: 1311] [Article Influence: 437.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 4. | Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J, Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA, Bray F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:335-349.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 857] [Cited by in RCA: 1438] [Article Influence: 239.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 5. | Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325:1978-1998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 87.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wesdorp NJ, van Goor VJ, Kemna R, Jansma EP, van Waesberghe JHTM, Swijnenburg RJ, Punt CJA, Huiskens J, Kazemier G. Advanced image analytics predicting clinical outcomes in patients with colorectal liver metastases: A systematic review of the literature. Surg Oncol. 2021;38:101578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Adlung L, Cohen Y, Mor U, Elinav E. Machine learning in clinical decision making. Med. 2021;2:642-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dias R, Torkamani A. Artificial intelligence in clinical and genomic diagnostics. Genome Med. 2019;11:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | He YS, Su JR, Li Z, Zuo XL, Li YQ. Application of artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Dig Dis. 2019;20:623-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Min JK, Kwak MS, Cha JM. Overview of Deep Learning in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Gut Liver. 2019;13:388-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Nagaraju GP, Sandhya T, Srilatha M, Ganji SP, Saddala MS, El-Rayes BF. Artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal cancers: Diagnostic, prognostic, and surgical strategies. Cancer Lett. 2025;612:217461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang S, Yang J, Fong S, Zhao Q. Artificial intelligence in cancer diagnosis and prognosis: Opportunities and challenges. Cancer Lett. 2020;471:61-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Hassan C, Spadaccini M, Iannone A, Maselli R, Jovani M, Chandrasekar VT, Antonelli G, Yu H, Areia M, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Bhandari P, Sharma P, Rex DK, Rösch T, Wallace M, Repici A. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:77-85.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 70.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 14. | Fortuin A, Rooij Md, Zamecnik P, Haberkorn U, Barentsz J. Molecular and functional imaging for detection of lymph node metastases in prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:13842-13875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Malhotra K, Bawa A, Singla A, Malhotra S, Kansal R, Grewal J, Goyal M, Goyal K, Singla A, Mondal H. Digital impact of world hepatitis day: Formulating evidence-based recommendations for promoting healthcare awareness events. J Educ Health Promot. 2023;12:288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang Z, Gong J, Li J, Sun H, Pan Y, Zhao L. The gap before real clinical application of imaging-based machine-learning and radiomic models for chemoradiation outcome prediction in esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2023;109:2451-2466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Abbaspour E, Karimzadhagh S, Monsef A, Joukar F, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Hassanipour S. Application of radiomics for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2024;110:3795-3813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Imperiale TF, Gruber RN, Stump TE, Emmett TW, Monahan PO. Performance Characteristics of Fecal Immunochemical Tests for Colorectal Cancer and Advanced Adenomatous Polyps: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:319-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Niedermaier T, Weigl K, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Diagnostic performance of flexible sigmoidoscopy combined with fecal immunochemical test in colorectal cancer screening: meta-analysis and modeling. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:481-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sultan AS, Elgharib MA, Tavares T, Jessri M, Basile JR. The use of artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in oncologic histopathology. J Oral Pathol Med. 2020;49:849-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fu B, Zhang M, He J, Cao Y, Guo Y, Wang R. StoHisNet: A hybrid multi-classification model with CNN and Transformer for gastric pathology images. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2022;221:106924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhou HY, Cheng JM, Chen TW, Zhang XM, Ou J, Cao JM, Li HJ. CT radiomics for prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2023;78:100264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cao R, Yang F, Ma SC, Liu L, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wu DH, Wang T, Lu WJ, Cai WJ, Zhu HB, Guo XJ, Lu YW, Kuang JJ, Huan WJ, Tang WM, Huang K, Huang J, Yao J, Dong ZY. Development and interpretation of a pathomics-based model for the prediction of microsatellite instability in Colorectal Cancer. Theranostics. 2020;10:11080-11091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jiang Y, Zhang Z, Yuan Q, Wang W, Wang H, Li T, Huang W, Xie J, Chen C, Sun Z, Yu J, Xu Y, Poultsides GA, Xing L, Zhou Z, Li G, Li R. Predicting peritoneal recurrence and disease-free survival from CT images in gastric cancer with multitask deep learning: a retrospective study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4:e340-e350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ting WC, Lu YA, Ho WC, Cheewakriangkrai C, Chang HR, Lin CL. Machine Learning in Prediction of Second Primary Cancer and Recurrence in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:280-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bojmar L, Zambirinis CP, Hernandez JM, Chakraborty J, Shaashua L, Kim J, Johnson KE, Hanna S, Askan G, Burman J, Ravichandran H, Zheng J, Jolissaint JS, Srouji R, Song Y, Choubey A, Kim HS, Cioffi M, van Beek E, Sigel C, Jessurun J, Velasco Riestra P, Blomstrand H, Jönsson C, Jönsson A, Lauritzen P, Buehring W, Ararso Y, Hernandez D, Vinagolu-Baur JP, Friedman M, Glidden C, Firmenich L, Lieberman G, Mejia DL, Nasar N, Mutvei AP, Paul DM, Bram Y, Costa-Silva B, Basturk O, Boudreau N, Zhang H, Matei IR, Hoshino A, Kelsen D, Sagi I, Scherz A, Scherz-Shouval R, Yarden Y, Oren M, Egeblad M, Lewis JS, Keshari K, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, Rajasekhar VK, Healey JH, Björnsson B, Simeone DM, Tuveson DA, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Bromberg J, Vincent CT, O'Reilly EM, DeMatteo RP, Balachandran VP, D'Angelica MI, Kingham TP, Allen PJ, Simpson AL, Elemento O, Sandström P, Schwartz RE, Jarnagin WR, Lyden D. Multi-parametric atlas of the pre-metastatic liver for prediction of metastatic outcome in early-stage pancreatic cancer. Nat Med. 2024;30:2170-2180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen T, Li X, Mao Q, Wang Y, Li H, Wang C, Shen Y, Guo E, He Q, Tian J, Zhu M, Wu J, Liang W, Liu H, Yu J, Li G. An artificial intelligence method to assess the tumor microenvironment with treatment outcomes for gastric cancer patients after gastrectomy. J Transl Med. 2022;20:100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Quero G, Mascagni P, Kolbinger FR, Fiorillo C, De Sio D, Longo F, Schena CA, Laterza V, Rosa F, Menghi R, Papa V, Tondolo V, Cina C, Distler M, Weitz J, Speidel S, Padoy N, Alfieri S. Artificial Intelligence in Colorectal Cancer Surgery: Present and Future Perspectives. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:3803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Kitaguchi D, Takeshita N, Matsuzaki H, Oda T, Watanabe M, Mori K, Kobayashi E, Ito M. Automated laparoscopic colorectal surgery workflow recognition using artificial intelligence: Experimental research. Int J Surg. 2020;79:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Park SH, Park HM, Baek KR, Ahn HM, Lee IY, Son GM. Artificial intelligence based real-time microcirculation analysis system for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:6945-6962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ribero D, Baldassarri D, Spinoglio G. Robotic taTME using the da Vinci SP: technical notes in a cadaveric model. Updates Surg. 2021;73:1125-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Luo R, Zheng F, Zhang H, Zhu W, He P, Liu D. Robotic natural orifice specimen extraction surgery versus traditional robotic-assisted surgery (NOTR) for patients with colorectal cancer: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22:121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Baek SJ, Piozzi GN, Kim SH. Optimizing outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery with robotic platforms. Surg Oncol. 2021;37:101559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kleppe A, Skrede OJ, De Raedt S, Hveem TS, Askautrud HA, Jacobsen JE, Church DN, Nesbakken A, Shepherd NA, Novelli M, Kerr R, Liestøl K, Kerr DJ, Danielsen HE. A clinical decision support system optimising adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancers by integrating deep learning and pathological staging markers: a development and validation study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:1221-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Park JH, Baek JH, Sym SJ, Lee KY, Lee Y. A data-driven approach to a chemotherapy recommendation model based on deep learning for patients with colorectal cancer in Korea. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20:241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu X, Zhang D, Liu Z, Li Z, Xie P, Sun K, Wei W, Dai W, Tang Z, Ding Y, Cai G, Tong T, Meng X, Tian J. Deep learning radiomics-based prediction of distant metastasis in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: A multicentre study. EBioMedicine. 2021;69:103442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Feng L, Liu Z, Li C, Li Z, Lou X, Shao L, Wang Y, Huang Y, Chen H, Pang X, Liu S, He F, Zheng J, Meng X, Xie P, Yang G, Ding Y, Wei M, Yun J, Hung MC, Zhou W, Wahl DR, Lan P, Tian J, Wan X. Development and validation of a radiopathomics model to predict pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4:e8-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ferrando L, Cirmena G, Garuti A, Scabini S, Grillo F, Mastracci L, Isnaldi E, Marrone C, Gonella R, Murialdo R, Fiocca R, Romairone E, Ballestrero A, Zoppoli G. Development of a long non-coding RNA signature for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0226595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sanchez-Ibarra HE, Jiang X, Gallegos-Gonzalez EY, Cavazos-González AC, Chen Y, Morcos F, Barrera-Saldaña HA. KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutation prevalence, clinicopathological association, and their application in a predictive model in Mexican patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0235490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | He K, Liu X, Li M, Li X, Yang H, Zhang H. Noninvasive KRAS mutation estimation in colorectal cancer using a deep learning method based on CT imaging. BMC Med Imaging. 2020;20:59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hu D, Zhang B, Yu M, Shi W, Zhang L. Identification of prognostic biomarkers and drug target prediction for colon cancer according to a competitive endogenous RNA network. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22:620-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Lipkova J, Chen RJ, Chen B, Lu MY, Barbieri M, Shao D, Vaidya AJ, Chen C, Zhuang L, Williamson DFK, Shaban M, Chen TY, Mahmood F. Artificial intelligence for multimodal data integration in oncology. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:1095-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 87.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yang H, Yang M, Chen J, Yao G, Zou Q, Jia L. Multimodal deep learning approaches for precision oncology: a comprehensive review. Brief Bioinform. 2024;26:bbae699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Chen Z, Chen Y, Sun Y, Tang L, Zhang L, Hu Y, He M, Li Z, Cheng S, Yuan J, Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhao J, Gong J, Zhao L, Cao B, Li G, Zhang X, Dong B, Shen L. Predicting gastric cancer response to anti-HER2 therapy or anti-HER2 combined immunotherapy based on multi-modal data. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Fahmy D, Alksas A, Elnakib A, Mahmoud A, Kandil H, Khalil A, Ghazal M, van Bogaert E, Contractor S, El-Baz A. The Role of Radiomics and AI Technologies in the Segmentation, Detection, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:6123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Asare A, Bagci U. PolypSeg-GradCAM: Towards Explainable Computer-Aided Gastrointestinal Disease Detection Using U-Net Based Segmentation and Grad-CAM Visualization on the Kvasir Dataset. 2025 Preprint. Available from: arXiv:2509.18159. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 47. | Prezja F, Äyrämö S, Pölönen I, Ojala T, Lahtinen S, Ruusuvuori P, Kuopio T. Improved accuracy in colorectal cancer tissue decomposition through refinement of established deep learning solutions. Sci Rep. 2023;13:15879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Joshi H, Joseph S. Standardization and Interoperability: Federated Learning's Impact on EHR Systems and Health Informatics. Adv Health Inf Sci Pract. 2025;1:UBYM3803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Pati S, Baid U, Edwards B, Sheller M, Wang SH, Reina GA, Foley P, Gruzdev A, Karkada D, Davatzikos C, Sako C, Ghodasara S, Bilello M, Mohan S, Vollmuth P, Brugnara G, Preetha CJ, Sahm F, Maier-Hein K, Zenk M, Bendszus M, Wick W, Calabrese E, Rudie J, Villanueva-Meyer J, Cha S, Ingalhalikar M, Jadhav M, Pandey U, Saini J, Garrett J, Larson M, Jeraj R, Currie S, Frood R, Fatania K, Huang RY, Chang K, Balaña C, Capellades J, Puig J, Trenkler J, Pichler J, Necker G, Haunschmidt A, Meckel S, Shukla G, Liem S, Alexander GS, Lombardo J, Palmer JD, Flanders AE, Dicker AP, Sair HI, Jones CK, Venkataraman A, Jiang M, So TY, Chen C, Heng PA, Dou Q, Kozubek M, Lux F, Michálek J, Matula P, Keřkovský M, Kopřivová T, Dostál M, Vybíhal V, Vogelbaum MA, Mitchell JR, Farinhas J, Maldjian JA, Yogananda CGB, Pinho MC, Reddy D, Holcomb J, Wagner BC, Ellingson BM, Cloughesy TF, Raymond C, Oughourlian T, Hagiwara A, Wang C, To MS, Bhardwaj S, Chong C, Agzarian M, Falcão AX, Martins SB, Teixeira BCA, Sprenger F, Menotti D, Lucio DR, LaMontagne P, Marcus D, Wiestler B, Kofler F, Ezhov I, Metz M, Jain R, Lee M, Lui YW, McKinley R, Slotboom J, Radojewski P, Meier R, Wiest R, Murcia D, Fu E, Haas R, Thompson J, Ormond DR, Badve C, Sloan AE, Vadmal V, Waite K, Colen RR, Pei L, Ak M, Srinivasan A, Bapuraj JR, Rao A, Wang N, Yoshiaki O, Moritani T, Turk S, Lee J, Prabhudesai S, Morón F, Mandel J, Kamnitsas K, Glocker B, Dixon LVM, Williams M, Zampakis P, Panagiotopoulos V, Tsiganos P, Alexiou S, Haliassos I, Zacharaki EI, Moustakas K, Kalogeropoulou C, Kardamakis DM, Choi YS, Lee SK, Chang JH, Ahn SS, Luo B, Poisson L, Wen N, Tiwari P, Verma R, Bareja R, Yadav I, Chen J, Kumar N, Smits M, van der Voort SR, Alafandi A, Incekara F, Wijnenga MMJ, Kapsas G, Gahrmann R, Schouten JW, Dubbink HJ, Vincent AJPE, van den Bent MJ, French PJ, Klein S, Yuan Y, Sharma S, Tseng TC, Adabi S, Niclou SP, Keunen O, Hau AC, Vallières M, Fortin D, Lepage M, Landman B, Ramadass K, Xu K, Chotai S, Chambless LB, Mistry A, Thompson RC, Gusev Y, Bhuvaneshwar K, Sayah A, Bencheqroun C, Belouali A, Madhavan S, Booth TC, Chelliah A, Modat M, Shuaib H, Dragos C, Abayazeed A, Kolodziej K, Hill M, Abbassy A, Gamal S, Mekhaimar M, Qayati M, Reyes M, Park JE, Yun J, Kim HS, Mahajan A, Muzi M, Benson S, Beets-Tan RGH, Teuwen J, Herrera-Trujillo A, Trujillo M, Escobar W, Abello A, Bernal J, Gómez J, Choi J, Baek S, Kim Y, Ismael H, Allen B, Buatti JM, Kotrotsou A, Li H, Weiss T, Weller M, Bink A, Pouymayou B, Shaykh HF, Saltz J, Prasanna P, Shrestha S, Mani KM, Payne D, Kurc T, Pelaez E, Franco-Maldonado H, Loayza F, Quevedo S, Guevara P, Torche E, Mendoza C, Vera F, Ríos E, López E, Velastin SA, Ogbole G, Soneye M, Oyekunle D, Odafe-Oyibotha O, Osobu B, Shu'aibu M, Dorcas A, Dako F, Simpson AL, Hamghalam M, Peoples JJ, Hu R, Tran A, Cutler D, Moraes FY, Boss MA, Gimpel J, Veettil DK, Schmidt K, Bialecki B, Marella S, Price C, Cimino L, Apgar C, Shah P, Menze B, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Martin J, Bakas S. Federated learning enables big data for rare cancer boundary detection. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Feng B, Shi J, Huang L, Yang Z, Feng ST, Li J, Chen Q, Xue H, Chen X, Wan C, Hu Q, Cui E, Chen Y, Long W. Robustly federated learning model for identifying high-risk patients with postoperative gastric cancer recurrence. Nat Commun. 2024;15:742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Ștefănigă SA, Cordoș AA, Ivascu T, Feier CVI, Muntean C, Stupinean CV, Călinici T, Aluaș M, Bolboacă SD. Advancing Precision Oncology with Digital and Virtual Twins: A Scoping Review. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:3817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Koçak B, Ponsiglione A, Stanzione A, Bluethgen C, Santinha J, Ugga L, Huisman M, Klontzas ME, Cannella R, Cuocolo R. Bias in artificial intelligence for medical imaging: fundamentals, detection, avoidance, mitigation, challenges, ethics, and prospects. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2025;31:75-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Guo LN, Lee MS, Kassamali B, Mita C, Nambudiri VE. Bias in, bias out: Underreporting and underrepresentation of diverse skin types in machine learning research for skin cancer detection-A scoping review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:157-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Bhinder B, Gilvary C, Madhukar NS, Elemento O. Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Research and Precision Medicine. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:900-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 83.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Pham T. Ethical and legal considerations in healthcare AI: innovation and policy for safe and fair use. R Soc Open Sci. 2025;12:241873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Meskó B, Topol EJ. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 133.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Liu X, Cruz Rivera S, Moher D, Calvert MJ, Denniston AK; SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI Working Group. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:e537-e548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ. 2024;385:q902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kwong JCC, Khondker A, Lajkosz K, McDermott MBA, Frigola XB, McCradden MD, Mamdani M, Kulkarni GS, Johnson AEW. APPRAISE-AI Tool for Quantitative Evaluation of AI Studies for Clinical Decision Support. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2335377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Macheka S, Ng PY, Ginsburg O, Hope A, Sullivan R, Aggarwal A. Prospective evaluation of artificial intelligence (AI) applications for use in cancer pathways following diagnosis: a systematic review. BMJ Oncol. 2024;3:e000255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Johansson ALV, Kønig SM, Larønningen S, Engholm G, Kroman N, Seppä K, Malila N, Steig BÁ, Gudmundsdóttir EM, Ólafsdóttir EJ, Lundberg FE, Andersson TM, Lambert PC, Lambe M, Pettersson D, Aagnes B, Friis S, Storm H. Have the recent advancements in cancer therapy and survival benefitted patients of all age groups across the Nordic countries? NORDCAN survival analyses 2002-2021. Acta Oncol. 2024;63:179-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Messmann H, Bisschops R, Antonelli G, Libânio D, Sinonquel P, Abdelrahim M, Ahmad OF, Areia M, Bergman JJGHM, Bhandari P, Boskoski I, Dekker E, Domagk D, Ebigbo A, Eelbode T, Eliakim R, Häfner M, Haidry RJ, Jover R, Kaminski MF, Kuvaev R, Mori Y, Palazzo M, Repici A, Rondonotti E, Rutter MD, Saito Y, Sharma P, Spada C, Spadaccini M, Veitch A, Gralnek IM, Hassan C, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Expected value of artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal endoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy. 2022;54:1211-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Johnson KB, Wei WQ, Weeraratne D, Frisse ME, Misulis K, Rhee K, Zhao J, Snowdon JL. Precision Medicine, AI, and the Future of Personalized Health Care. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 683] [Article Influence: 113.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/