Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.113440

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: November 18, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 139 Days and 4.8 Hours

The liver represents a common site of distant metastasis in patients with eso

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of first-line chemoimmunotherapy for EC patients with liver metastases and to analyze prognostic factors.

This retrospective study included 126 EC patients with liver metastases at Zhejiang Cancer Hospital between 2014 and 2024. Patients receiving CMT were compared with those receiving CMT + ICI. Analyzed variables included clinicopathological features, treatment history, characteristics of metastasis, systemic and local treatments, overall survival (OS), and treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs). Prognostic factors were evaluated using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression models. Finally, efficacy outcomes and TRAE profiles were compared between the two groups.

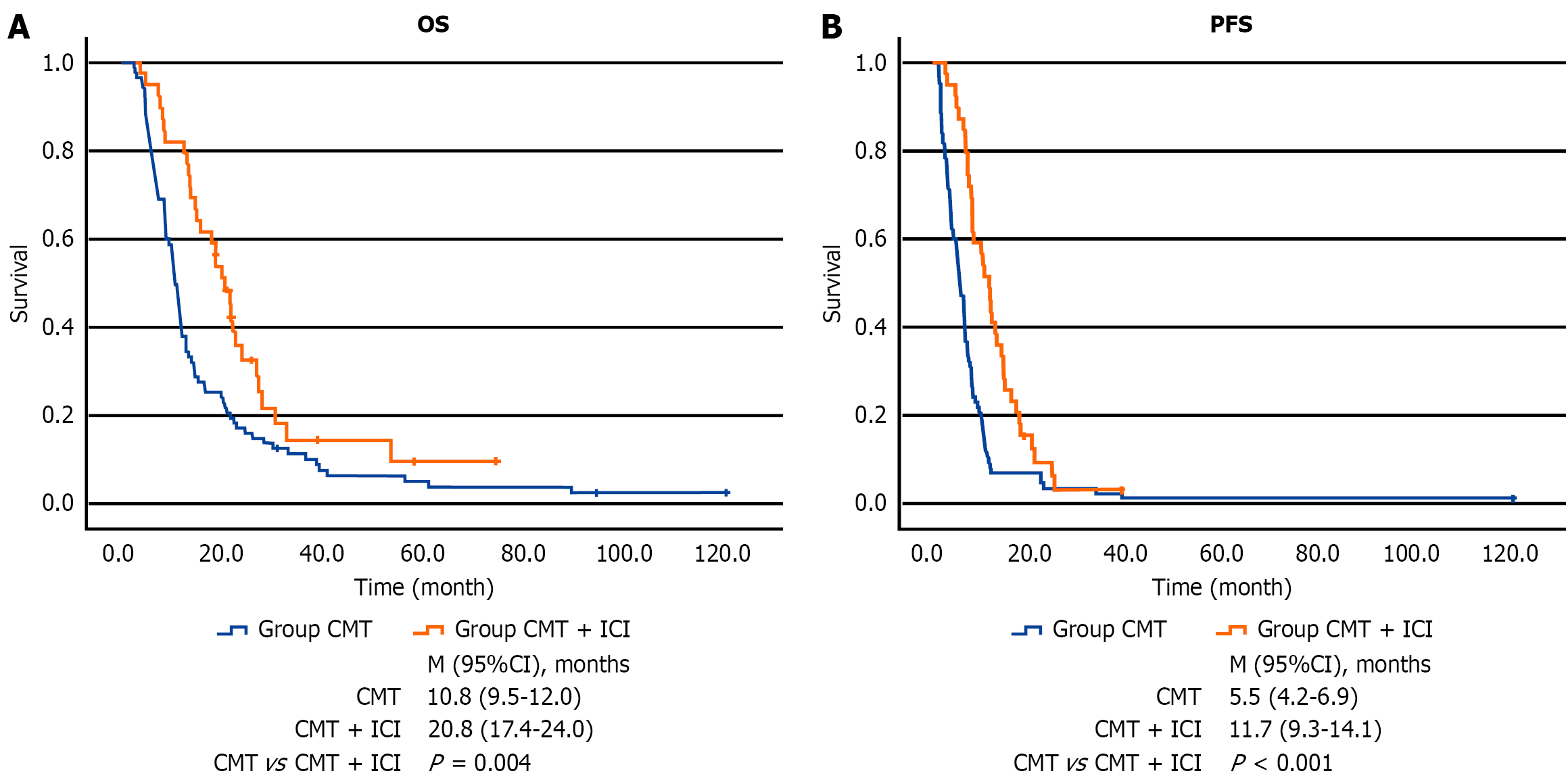

A significant difference in median OS was identified between the two groups (10.8 months in the CMT group vs 20.8 months in the CMT + ICI group, P = 0.004). The CMT + ICI group also demonstrated a significantly longer median progression-free survival of 11.7 months (P < 0.001). Patients receiving combination therapy exhibited significantly improved systemic objective response rate and disease control rate. Multivariate analysis identified key factors significantly influencing OS in EC patients with liver metastases: Karnofsky Performance Status score ≥ 70, receipt of local therapy for liver metastases, and the number of cycles of CMT and immunotherapy received. Furthermore, the incidence of TRAEs did not significantly differ between the CMT + ICI and CMT groups.

For EC patients with liver metastases, the combination of CMT and ICIs demonstrates significantly superior effi

Core Tip: Although chemoimmunotherapy is the standard first-line treatment for metastatic esophageal cancer, its efficacy in the subgroup with liver metastases remains poorly characterized. This study demonstrated that chemoimmunotherapy significantly improved overall survival in this population, with a manageable safety profile. Key prognostic factors were identified, and the addition of local therapy to liver metastases may provide a rational approach to further optimize treatment outcomes.

- Citation: Dai EH, Que SH, Xu H, Zhong GQ, Zhang Z, Liang X, Zhai SW, Li YT, Wang JJ, Feng W. Efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy in esophageal cancer patients with liver metastases. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(1): 113440

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i1/113440.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.113440

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the seventh leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally[1]. It is histologically classified into two main types, including esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma. ESCC is the predominant form in China[2,3]. Recent statistics indicated that in 2022, 224012 new EC cases and 187467 EC-associated deaths were recorded in China, accounting for 43.8% and 42.1% of global incidence and mortality, respectively, representing the highest burden worldwide[4]. Approximately 50% of patients present with distant metastasis at initial diagnosis, and over one-third develop metastatic disease following surgery or radiotherapy. Survival outcomes are significantly reduced in advanced EC patients, particularly among those with distant metastases[5], where median survival plummets to 5 months post-metastasis[6]. Distant organ metastasis remains the primary cause of treatment failure and death in EC, severely compromising patients’ survival and quality of life. The liver is one of the most common sites of distant metastasis[7]. Post-esophagectomy hepatic recurrence has been previously reported to be correlated with markedly worse survival outcomes (P = 0.032)[8]. Furthermore, liver metastases have been found to confer a poorer prognosis than metastases to other organs. The paucity of research in this area is largely attributable to the subpopulation's clinically insidious nature and dismal outcomes[9].

Patients with EC liver metastases (ECLM) experience a poor prognosis, and there is no consensus on the most effective management strategies for the disease. Prior to the advent of immunotherapy, palliative systemic chemotherapy (CMT) constituted the prevailing standard of care, yielding response rates of 13%-35.9%, disease control rates (DCRs) of 57%-63.9%, a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 3.6 months, and a median overall survival (OS) ranging from 5.5-6.7 months[10]. The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has transformed the therapeutic paradigm for advanced EC. Pivotal trials, including KEYNOTE-590[11], CHECKMATE-649[12], and ESCORT-1st[13], demonstrated substantial survival benefits with immunotherapy, prompting its shift from later lines to first-line treatment and revolutionizing the CMT-dominated framework. Consequently, chemoimmunotherapy has become the standard first-line regimen for metastatic EC. However, few studies have specifically reported survival outcomes for the liver metastasis subgroup, and the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy for ECLM patients has still remained elusive.

The ASTRUM-007 trial, a multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase 3 study, revealed that serplulimab in combination with CMT significantly improved PFS and OS compared with the combination of placebo and CMT for patients with locally advanced or metastatic ESCC. In the liver metastasis subgroup, the incorporation of immunotherapy resulted in a significant enhancement of PFS. Although no statistical significance was achieved for OS, a trend indicating a prolonged median OS (mOS) was noted. It is noteworthy that in the liver metastasis subgroup (combined positive score ≥ 10), immunotherapy demonstrated more remarkable improvements in terms of both median PFS (mPFS) and mOS compared with placebo[14]. These findings demonstrate that chemoimmunotherapy may be a viable option for ECLM patients. Nevertheless, due to the paucity of studies, the recommendation based on subgroup analyses of clinical studies remains controversial and requires further research. The objective of this study is twofold: (1) To conduct a comparative analysis of the efficacy and adverse event profiles between CMT alone and chemoimmunotherapy in patients with ECLM; and (2) To explore and identify potential prognostic factors in this specific cohort.

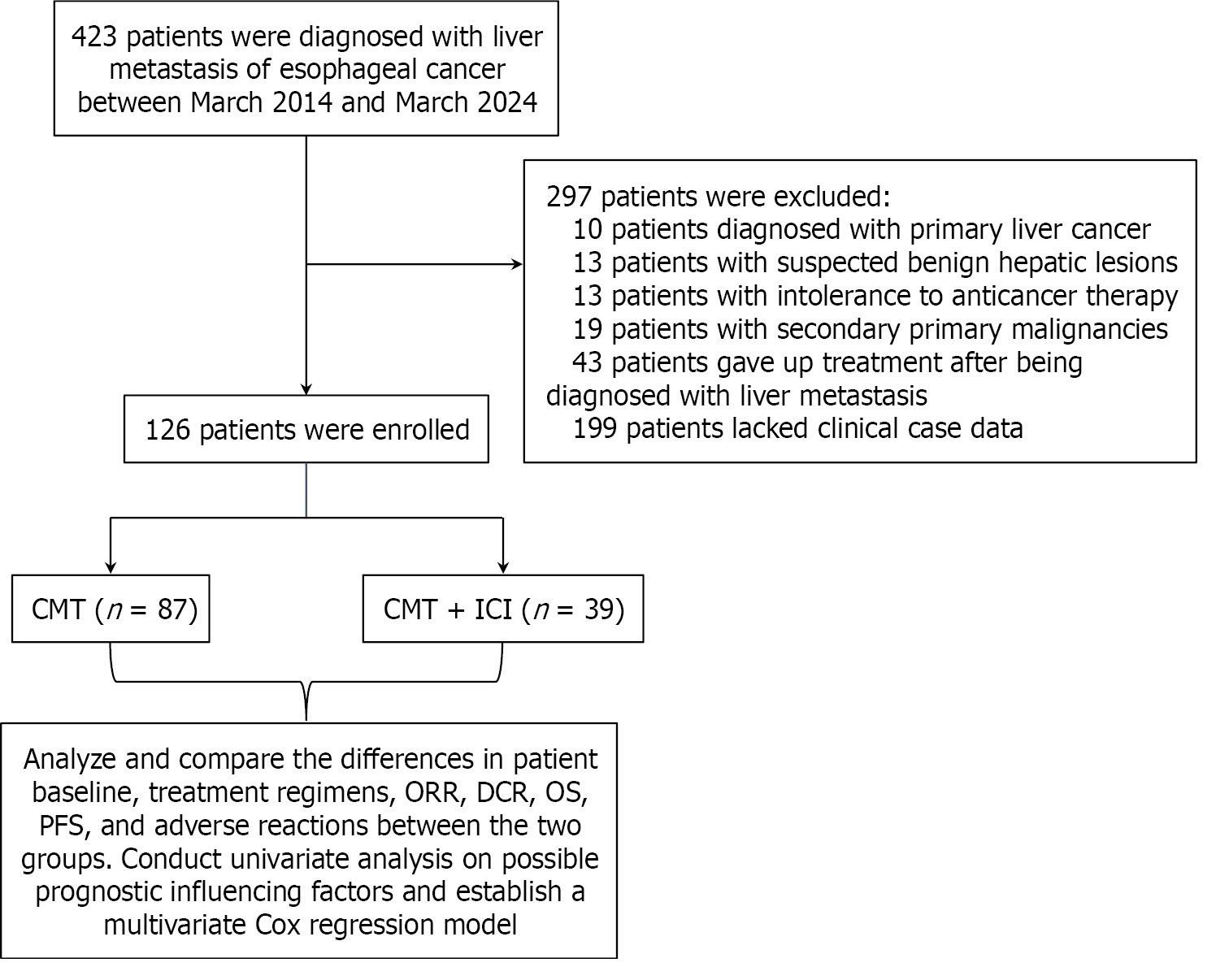

This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of EC patients with liver metastasis who were admitted to the Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (Hangzhou, China) between March 2014 and March 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Clinically diagnosed with liver metastasis originating from EC, including EC patients with liver metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis, as well as those who developed liver metastasis after undergoing radical treatment for EC; (2) Confirmation of measurable liver lesions by liver ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (3) The Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score was ≥ 60; and (4) The availability of complete medical records. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Co-existence of other pathological types of malignant tumors at the initial diagnosis; (2) Co-existence of active or uncontrolled severe infections; (3) Patients who discontinued treatment following the diagnosis of liver metastasis from EC; and (4) Missing clinical data.

This study collected a large amount of data, such as the demographic characteristics, clinical data, and treatment res

The study was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 edition), it was approved by the Medical Ethics Com

The study included two groups: The CMT group (n = 39) and the CMT + ICI group (n = 39). Patients in the CMT group received conventional CMT regimens, while those in the CMT + ICI group were treated with CMT plus immunotherapy that adhered to the current NCCN guidelines for the first-line treatment of metastatic EC. The CMT regimens, admini

The primary endpoint was OS, which was defined as the interval from the diagnosis of liver metastasis to death from any cause or the last confirmed follow-up. The secondary endpoint was PFS, which was calculated from the initiation of treatment to documented disease progression, death from any cause, or the most recent confirmed follow-up. The study data were finalized on May 15, 2025, establishing the cut-off date for analysis.

The tumor response evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST; version 1.1). Routine assessments were performed at regular intervals throughout the active treatment phase, and the interval between assessments ranged from 6 weeks to 8 weeks. Following the end of treatment, the assessments were conducted at 3- to 6-month intervals. According to the RECIST (version 1.1), tumor response evaluation is a stan

Moreover, TRAEs were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0). The attending physician was responsible for systematically documenting and grading any TRAEs recorded during the patient’s hospitalization. In contrast, TRAEs reported after discharge were primarily collected through patient self-reports and telephone follow-ups.

Intergroup comparisons of categorical variables, including baseline characteristics, treatment features, therapeutic responses, and TRAEs, were performed using the χ2 test, continuity-corrected χ2 test, or the Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to visualize and compare OS and PFS across groups, and between-group differences were assessed using the log-rank test. Univariate survival analysis was conducted via the Cox proportional-hazards model to identify prognostic factors for OS. Clinically relevant variables demonstrating statistical significance (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were subsequently imported into a multivariate Cox regression model. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 29.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

From January 2014 to March 2024, a total of 423 patients were diagnosed with ECLM at Zhejiang Cancer Hospital. Following the application of rigorous selection criteria, 126 patients were regarded eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients’ exclusion process is illustrated in Figure 1. The selected patients were divided into two groups: Patients re

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | Total number of cases (n = 126) | CMT group (n = 87) | CMT + ICI group | χ² value | P value |

| Age (years) | 0.451 | 0.502 | |||

| > 60 | 59 (46.8) | 39 (44.8) | 20 (51.3) | ||

| ≤ 60 | 67 (53.2) | 48 (55.2) | 19 (48.7) | ||

| Sex | 0.079 | 0.779 | |||

| Male | 119 (94.4) | 83 (95.4) | 36 (92.3) | ||

| Female | 7 (5.6) | 4 (4.6) | 3 (7.7) | ||

| Underlying diseases | 0.016 | 0.900 | |||

| Yes | 43 (34.1) | 30 (34.5) | 13 (33.3) | ||

| No | 83 (65.9) | 57 (65.5) | 26 (66.7) | ||

| Dysphagia or cancer-related symptoms | 0.182 | 0.669 | |||

| Yes | 106 (84.1) | 74 (85.1) | 32 (682.1) | ||

| No | 20 (15.9) | 13 (14.9) | 7 (17.9) | ||

| KPS score | - | 0.094 | |||

| ≥ 70 | 124 (98.4) | 87 (100.0) | 37 (94.9) | ||

| < 70 | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.1) | ||

| Histology | 2.098 | 0.321 | |||

| ESCC | 111 (88.1) | 74 (85.1) | 37 (94.9) | ||

| EAC | 3 (2.4) | 3 (3.4) | 2 (5.1) | ||

| Other | 12 (9.5) | 10 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Primary tumor location | 1.649 | 0.428 | |||

| Upper | 4 (3.2) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Middle | 51 (40.5) | 32 (36.8) | 19 (48.7) | ||

| Lower | 71 (56.3) | 52 (59.8) | 19 (48.7) | ||

| Tumor differentiation grade | 1.476 | 0.452 | |||

| G1 | 6 (4.8) | 5 (5.7) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| G2 | 46 (36.5) | 34 (39.1) | 12 (30.8) | ||

| G3-G4 | 74 (58.7) | 48 (55.2) | 26 (66.7) | ||

| Tumor stage | 0.961 | 0.327 | |||

| T1-2 | 17 (13.5) | 10 (11.5) | 7 (17.9) | ||

| T3-4 | 109 (86.5) | 77 (88.5) | 32 (82.1) | ||

| Nodal stage | 0.007 | 0.932 | |||

| N0 | 15 (11.9) | 11 (12.6) | 4 (10.3) | ||

| N+ | 111 (88.1) | 76 (87.4) | 35 (89.7) | ||

| Synchronous liver metastasis at initial diagnosis | 0.487 | 0.485 | |||

| Yes | 62 (49.2) | 41 (47.1) | 21 (53.8) | ||

| No | 64 (50.8) | 46 (52.9) | 18 (46.2) | ||

| Distant lymph node metastasis | 0.054 | 0.816 | |||

| Yes | 53 (42.1) | 36 (41.4) | 17 (43.6) | ||

| No | 73 (57.9) | 51 (58.6) | 22 (56.4) | ||

| Primary lesion surgery | 0.184 | 0.668 | |||

| Yes | 52 (41.3) | 37 (42.5) | 15 (38.5) | ||

| No | 74 (58.7) | 50 (57.5) | 24 (61.5) | ||

| Primary lesion radiotherapy | 0.227 | 0.634 | |||

| Yes | 51 (40.5) | 34 (39.1) | 17 (43.6) | ||

| No | 75 (59.5) | 53 (60.9) | 22 (56.4) | ||

| Pre-hepatic metastasis chemotherapy | 0.483 | 0.487 | |||

| Yes | 41 (32.5) | 30 (34.5) | 11 (28.2) | ||

| No | 85 (67.5) | 57 (65.5) | 28 (71.8) | ||

| Pre-hepatic metastasis targeted therapy | - | 0.552 | |||

| Yes | 3 (2.4) | 84 (96.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No | 123 (97.6) | 3 (3.4) | 39 (100.0) | ||

| Child-Pugh score | - | 1.000 | |||

| > 6 | 2 (1.6) | 2 (97.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| ≤ 6 | 124 (98.4) | 85 (2.3) | 39 (100.0) | ||

| Oligometastatic liver disease | 0.491 | 0.483 | |||

| Yes | 24 (19) | 18 (20.7) | 6 (15.4) | ||

| No | 102 (81) | 69 (79.3) | 33 (84.6) | ||

| Number of liver metastases | 1.680 | 0.195 | |||

| > 3 | 80 (63.5) | 52 (59.8) | 28 (71.8) | ||

| ≤ 3 | 46 (36.5) | 35 (40.2) | 11 (28.2) | ||

| Hepatic lobe involvement | 5.638 | 0.060 | |||

| Left | 8 (6.3) | 4 (4.6) | 4 (10.3) | ||

| Right | 40 (31.7) | 33 (37.9) | 7 (17.9) | ||

| Bilateral | 78 (61.9) | 50 (57.5) | 28 (71.8) | ||

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 3.739 | 0.060 | |||

| Yes | 55 (43.7) | 33 (37.9) | 22 (56.4) | ||

| No | 71 (56.3) | 54 (62.1) | 17 (43.6) | ||

| Lung metastasis | 2.321 | 0.128 | |||

| Yes | 60 (32.1) | 18 (20.7) | 13 (33.3) | ||

| No | 127 (67.9) | 69 (79.3) | 26 (66.7) | ||

| Bone metastasis | 0.182 | 0.669 | |||

| Yes | 20 (15.9) | 13 (14.9) | 7 (17.9) | ||

| No | 106 (84.1) | 74 (85.1) | 32 (82.1) | ||

| Brain metastasis | - | 1.000 | |||

| Yes | 3 (2.4) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| No | 123 (97.6) | 85 (97.7) | 38 (97.4) |

Treatment details are summarized in Table 2. In the CMT group, taxane-platinum regimens were administered to 49 (56.3%) patients, fluoropyrimidine-platinum to 23 (26.4%), and other regimens to 20 (15.9%). The CMT + ICI group received taxane-platinum (n = 26, 66.7%), fluoropyrimidine-platinum (n = 8, 20.5%), or other regimens (n = 5, 12.8%). A total of 105 (83.3%) patients continued CMT for ≥ 4 cycles, whereas 38 patients in the CMT + ICI group (97.4%) completed ≥ 4 cycles of immunotherapy. Totally, 39 (31.0%) cases in the two groups underwent local treatment of liver metastases, predominantly ablation (n = 24, 19.0%).

| Treatment-related characteristics | Total number of cases (n = 126) | CMT group (n = 87) | CMT + ICI group (n = 39) | χ² value | P value |

| Chemotherapy regimen | 0.852 | 0.653 | |||

| Taxane-based ± platinum | 75 (59.5) | 49 (56.3) | 26 (66.7) | ||

| Fluoropyrimidine ± platinum | 31 (24.6) | 23 (26.4) | 8 (20.5) | ||

| Other | 20 (15.9) | 15 (17.3) | 5 (12.8) | ||

| Chemotherapy cycle | 0.081 | 0.776 | |||

| ≥ 4 | 105 (83.3) | 72 (82.8) | 33 (84.6) | ||

| < 4 | 21 (16.7) | 15 (17.2) | 6 (15.4) | ||

| Immunotherapy cycle | 120.395 | < 0.001a | |||

| ≥ 4 | 38 (30.2) | 0 (0.0) | 38 (97.4) | ||

| < 4 | 88 (69.8) | 87 (100.0) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Liver local treatment | 0.746 | 0.388 | |||

| Yes | 39 (31.0) | 29 (33.3) | 10 (25.6) | ||

| No | 87 (69.0) | 58 (66.7) | 29 (74.4) | ||

| Local treatment modalities | 2.626 | 0.662 | |||

| None | 87 (69.0) | 58 (66.7) | 29 (74.4) | ||

| Ablation | 24 (19.0) | 18 (20.7) | 6 (15.4) | ||

| Surgery | 4 (3.2) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (2.6) | ||

| TACE | 4 (3.2) | 4 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Radiotherapy | 7 (5.6) | 4 (4.6) | 3 (7.7) |

The mOS in the CMT and the CMT + ICI groups was 10.8 and 20.8 months, respectively (P = 0.004). The Kaplan-Meier survival curve is illustrated in Figure 2A. The mPFS in the CMT and the CMT + ICI groups was 5.5 months and 11.7 months, respectively (P < 0.001). Compared with the CMT group, the CMT + ICI group also had a significant sur

The overall ORR was 69.8%, involving 58.6% in the CMT group and 94.9% in the CMT + ICI group (P < 0.001). The overall DCR was 82.5%, including 74.7% in the CMT group and 100.0% in the CMT + ICI group (P < 0.001). Additional details are presented in Table 3.

| Healing effect | Total number of cases (n = 126) | CMT group (n = 87) | CMT + ICI group (n = 39) | P value |

| ORR | 88 (69.8) | 51 (58.6) | 37 (94.9) | < 0.001 |

| DCR | 104 (82.5) | 65 (74.7) | 39 (100.0) | < 0.001 |

Table 4 presents TRAEs occurring in ≥ 10% of patients after systemic therapy for liver metastases. The overall incidence of TRAEs was 92.1% in the pooled groups. Hematological toxicities occurred in 87.4% of patients in the CMT group vs 92.3% in the CMT + ICI group (P = 0.60). Anemia developed in over 80% of patients with liver metastases during first-line treatment in both groups. The incidence rates of gastrointestinal TRAEs, such as nausea and vomiting, were 40.2% and 20.5% in the CMT and CMT + ICI groups, respectively (P = 0.03). No significant differences were identified between the two groups for other TRAEs, including fatigue and abnormal liver function. Grade 4 TRAEs occurred in 9 patients, and no grade 5 TRAEs were reported. Among patients receiving immunotherapy, immune-related adverse events included thyroid dysfunction in 3 patients, renal dysfunction in 1 patient, and a skin adverse reaction in 1 patient.

| TRAEs | Total number of cases (n = 126) | CMT group (n = 87) | CMT + ICI group (n = 39) | χ² value | P value |

| Any TRAEs | 116 (92.1) | 80 (92.0) | 36 (92.3) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| TRAEs ≥ 10% | |||||

| Hematologic toxicity | 112 (88.9) | 76 (87.4) | 36 (92.3) | 0.261 | 0.609 |

| Anemic | 104 (82.5) | 71 (81.6) | 33 (84.6) | 0.169 | 0.681 |

| Leucopenia | 71 (56.3) | 49 (56.3) | 22 (56.4) | 0.000 | 0.993 |

| Neutropenia | 57 (45.2) | 40 (46.0) | 17 (43.6) | 0.062 | 0.803 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 52 (41.3) | 33 (37.9) | 19 (48.7) | 1.293 | 0.256 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 71 (56.3) | 50 (57.5) | 21 (53.8) | 0.144 | 0.704 |

| Liver dysfunction | 40 (31.7) | 32 (36.8) | 8 (20.5) | 3.289 | 0.070 |

| Increased γ-GT | 15 (11.9) | 13 (14.9) | 2 (5.1) | 1.626 | 0.202 |

| Increased AST | 21 (16.7) | 16 (18.4) | 5 (12.8) | 0.602 | 0.438 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 43 (34.1) | 35 (40.2) | 8 (20.5) | 4.657 | 0.031a |

| Fatigue | 36 (28.6) | 25 (28.7) | 11 (28.2) | 0.004 | 0.951 |

| ≥ 3 TRAEs | 41 (32.5) | 32 (36.8) | 9 (23.1) | 2.304 | 0.129 |

| Hematologic toxicity | 37 (29.4) | 28 (32.2) | 9 (23.1) | 1.077 | 0.299 |

| Neutropenia | 17 (13.5) | 14 (16.1) | 3 (7.7) | 1.628 | 0.202 |

This study evaluated the impact of significant clinical factors on patients’ OS. Firstly, univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted to identify potential prognostic factors for OS, as detailed in Table 5. The univariate analysis de

| Influential factors (independent variables) | P value | HR | 95%CI for HR | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| Age (> 60/≤ 60 years) | 0.537 | 1.124 | 0.775 | 1.630 |

| Sex (male/female) | 0.781 | 1.124 | 0.493 | 2.560 |

| Underlying diseases (yes/no) | 0.324 | 1.220 | 0.822 | 1.810 |

| Dysphagia or cancer-related symptoms (yes/no) | 0.217 | 0.737 | 0.454 | 1.196 |

| KPS score (≥ 70/< 70) | 0.013a | 6.117 | 1.463 | 25.573 |

| Histology | ||||

| ESCC, dummy variable | 0.164 | |||

| EAC | 0.163 | 1.563 | 0.835 | 2.928 |

| Other | 0.168 | 2.269 | 0.709 | 7.267 |

| Tumor location | ||||

| Upper, dummy variable | 0.819 | |||

| Middle | 0.595 | 1.317 | 0.478 | 3.628 |

| Lower | 0.798 | 0.952 | 0.652 | 1.390 |

| Tumor differentiation grade | ||||

| Grade 1, dummy variable | 0.298 | |||

| Grade 2 | 0.140 | 2.044 | 0.791 | 5.281 |

| Grade 3-4 | 0.121 | 2.110 | 0.821 | 5.427 |

| Tumor stage (T1-2/T3-4) | 0.121 | 1.539 | 0.892 | 2.656 |

| Nodal stage (N0/N+) | 0.758 | 1.092 | 0.623 | 1.915 |

| Synchronous liver metastasis at initial diagnosis (yes/no) | 0.795 | 1.050 | 0.726 | 1.519 |

| Distant lymph node metastasis (yes/no) | 0.036a | 1.492 | 1.027 | 2.168 |

| Primary lesion surgery (yes/no) | 0.080 | 0.712 | 0.488 | 1.041 |

| Primary lesion radiotherapy (yes/no) | 0.765 | 0.944 | 0.649 | 1.373 |

| Pre-hepatic metastasis chemotherapy (yes/no) | 0.441 | 0.854 | 0.571 | 1.277 |

| Pre-hepatic metastasis targeted therapy (yes/no) | 0.009a | 4.809 | 1.477 | 15.656 |

| Child-Pugh score (> 6/≤ 6) | 0.107 | 3.224 | 0.778 | 13.361 |

| Number of liver metastases (> 3/≤ 3) | 0.012a | 1.650 | 1.115 | 2.441 |

| oligometastatic liver disease (yes/no) | 0.001a | 0.434 | 0.261 | 0.725 |

| Hepatic lobe involvement | ||||

| Bilateral lobes, dummy variable | 0.024a | |||

| Left lobe | 0.070 | 0.462 | 0.200 | 1.066 |

| Right lobe | 0.021a | 0.616 | 0.409 | 0.929 |

| Extrahepatic metastasis (yes/no) | 0.334 | 1.201 | 0.828 | 1.743 |

| Lung metastasis (yes/no) | 0.614 | 1.118 | 0.724 | 1.728 |

| Bone metastasis (yes/no) | 0.299 | 1.300 | 0.792 | 2.135 |

| Brain metastasis (yes/no) | 0.161 | 0.366 | 0.090 | 1.491 |

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||

| Taxane-based ± platinum, dummy variable | 0.012a | |||

| Fluoropyrimidine ± platinum | 0.627 | 1.115 | 0.720 | 1.727 |

| Other | 0.003a | 2.231 | 1.313 | 3.792 |

| Chemotherapy cycle (≥ 4/< 4) | < 0.001a | 0.261 | 0.160 | 0.425 |

| Immunotherapy (yes/no) | 0.005a | 0.551 | 0.364 | 0.836 |

| Immunotherapy cycle (≥ 4/< 4) | 0.004a | 0.538 | 0.353 | 0.820 |

| Liver local treatment (yes/no) | 0.005a | 0.546 | 0.358 | 0.833 |

| Local treatment modalities | ||||

| None, dummy variable | 0.047a | |||

| Ablation | 0.027a | 0.565 | 0.340 | 0.937 |

| Surgery | 0.217 | 0.528 | 0.192 | 1.455 |

| TACE | 0.409 | 1.530 | 0.557 | 4.203 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.064 | 0.424 | 0.171 | 1.050 |

To minimize multicollinearity, variables with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate Cox regression model after excluding factors demonstrating high correlation. The results of the multivariate Cox regression are detailed in Table 6. The analysis revealed that a KPS score ≥ 70, receipt of ≥ 4 CMT cycles, completion of ≥ 4 immunotherapy cycles, and administration of local liver therapy were significantly associated with improved OS.

| Influential factors (independent variables) | P value | HR | 95%CI for HR | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| KPS score (≥ 70/< 70) | 0.049a | 5.452 | 1.008 | 29.479 |

| Oligometastatic liver disease (yes/no) | 0.156 | 0.592 | 0.286 | 1.222 |

| Distant lymph node metastasis (yes/no) | 0.843 | 1.046 | 0.670 | 1.633 |

| Pre-hepatic metastasis targeted therapy (yes/no) | 0.378 | 1.853 | 0.470 | 7.310 |

| Hepatic lobe involvement | ||||

| Bilateral lobes, dummy variable | 0.449 | |||

| Left-sided lobe | 0.736 | 0.858 | 0.353 | 2.088 |

| Right-sided lobe | 0.206 | 0.686 | 0.382 | 1.231 |

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||

| Taxane-based ± platinum, dummy variable | 0.187 | |||

| Fluoropyrimidine ± platinum | 0.498 | 0.849 | 0.528 | 1.363 |

| Other | 0.123 | 1.570 | 0.885 | 2.785 |

| Chemotherapy cycle (≥ 4/< 4) | < 0.001a | 0.139 | 0.072 | 0.266 |

| Immunotherapy cycle (≥ 4/< 4) | < 0.001a | 0.225 | 0.132 | 0.383 |

| Liver local treatment (yes/no) | 0.021a | 0.549 | 0.330 | 0.913 |

The present study demonstrated that adding immunotherapy to systemic CMT could improve survival outcomes in EC patients with liver metastases, and systemic adverse events remained within acceptable limits. The combination group (CMT plus immunotherapy) exhibited significantly superior ORR and DCR compared with CMT alone. Notably, pre-specified subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the influences of different immunotherapy and CMT regimens (including fluoropyrimidine-base ± platinum and taxane-based ± platinum) on clinical outcomes in ECLM patients. The results indicated no statistically significant differences among these regimens. Since the choice of specific regimen did not demonstrate a discernible impact on the primary outcomes, a detailed discussion on this aspect was regarded unne

Compared with CMT alone, the combination group exhibited a significantly longer mOS (20.8 months vs 10.8 months, P = 0.004) and PFS (11.7 months vs 5.5 months, P < 0.001). These findings align with those of a separate study involving over 500 EC patients, including 103 with baseline liver metastases. In that study, the subgroup receiving CMT plus serpelimab (n = 71) demonstrated improved PFS compared with the CMT plus placebo subgroup (n = 32; 5.7 months vs 4.3 months; P = 0.03). Although OS did not reach statistical significance in that cohort, a numerical advantage was noted (13.7 months vs 10.3 months)[14]. The results of a previous study are consistent with those of the current study[14].

CMT remains the primary treatment for advanced EC, with mOS ranging from 5.5 months to 6.7 months for platinum/fluoropyrimidine or platinum/taxane doublets[10,15]. Recent clinical trials, such as KEYNOTE-590[11] and ESCORT-1st[13], provided noticeable evidence supporting the efficacy of immunotherapy in metastatic disease. However, due to the heterogeneity in PD-L1 expression among primary tumors, lymph nodes, metastatic sites and the potential immunosuppressive mechanisms, such as the liver-specific microenvironment regulation[16], immunotherapy has shown limited efficacy in patients with liver metastases. Existing studies on non-small cell lung cancer, endometrial cancer, gastric cancer, and breast cancer have indicated that PD-L1 expression is higher in metastatic tumors than that in primary tumors. In colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases, it has been confirmed that PD-L1 expression is elevated in liver metastases compared with primary tumors. Additionally, the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, the proliferation of inhibitory T cells, and increased secretion of inhibitory cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10, etc.) in the liver metastatic microenvironment can impact the effectiveness of anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy[17]. However, research on ECLM remains relatively scarce, and the mechanisms underlying resistance to immunotherapy have not been thoroughly explored. Consequently, the therapeutic impact on liver metastases warrants further investigation.

Compelling evidence suggests that liver metastases sequester systemic T cells, particularly CD8+ T cells, through interactions with FasL+CD11b+F4/80+ hepatic macrophages, leading to CD8+ T-cell apoptosis[18,19]. This sequestration has the potential to deplete systemic CD8+ T cells, which are critical for immunotherapy response, thereby limiting the efficacy of monotherapy. Mechanistically, fluoropyrimidines and platinum agents may enhance immunotherapy by: (1) Upregulating PD-L1 expression via JAK/STAT signaling pathway[16]; and (2) Promoting platinum-induced dendritic cell recruitment, sensitizing tumors to immune checkpoint blockade[20]. These synergistic mechanisms, supported by our clinical results, highlight that chemoimmunotherapy improves survival in EC patients with liver metastases.

The adverse events associated with chemoimmunotherapy remained within acceptable limits. Hematologic toxicities constituted over 80% of all TRAEs, and no significant difference was identified between the chemoimmunotherapy and CMT-alone groups. Similarly, the majority of adverse events, including abnormal liver function and hypoalbuminemia, exhibited comparable incidence rates. The incidence of grade ≥ 3 adverse events (predominantly hematologic toxicities) also demonstrated no significant intergroup difference. These findings are consistent with those of a previous study[14], which reported hematological toxicity rates of 78.7% and 78.6% in the chemoimmunotherapy group and the CMT group, respectively, and most non-hematological toxicities exhibited comparable frequencies. Collectively, these data indicated that the addition of immunotherapy did not exacerbate treatment-related toxicity. It is noteworthy that the chemoimmunotherapy group demonstrated significantly reduced incidence rates of nausea and vomiting vs the CMT group. This phenomenon may be ascribed to the enhanced reduction in tumor load and the improved patient performance status that resulted from the therapeutic efficacy.

Univariate Cox regression was employed as the primary screening method. All clinically meaningful covariates that achieved statistical significance (defined as P < 0.05) in univariate analysis were involved in the final multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. It is noteworthy that due to collinearity between the variables "immunotherapy (yes/no)" and "immunotherapy cycles (≥ 4/< 4)", which were both independent prognostic factors, only the latter was retained in the final multivariate regression model, as it was considered clinically more relevant. Therapeutic adequacy, defined as the completion of ≥ 4 CMT cycles and ≥ 4 immunotherapy cycles, emerged as a significant prognostic factor. These findings highlight the critical importance of adequate therapeutic exposure. Premature discontinuation due to adverse events or socioeconomic factors may compromise survival outcomes, providing valuable insights for clinical mana

Local liver-directed therapy was identified as an independent prognostic factor. Modalities included radiofrequency ablation (RFA), metastasectomy, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), and radiotherapy. Due to concerns of collinearity, detailed stratification was excluded from the multivariate analysis. Univariate analysis revealed a significant survival benefit from RFA. A small-scale study (n = 40) of oligometastatic EC patients (≤ 3 liver lesions) treated with fluoropyrimidine + platinum CMT demonstrated superior mOS (13 months vs 7 months, P = 0.011) and PFS (P = 0.03) with microwave ablation compared with CMT alone[21]. Similarly, a single-arm study (n = 16) reported a mOS/PFS of 14.5/7.5 months with ablation plus CMT, in which outcomes exceeded historical CMT benchmarks. These data support our conclusion that ablation, particularly RFA, improves survival in this patient population.

Liver-directed radiotherapy represents a common local treatment modality for EC patients with hepatic metastases. The current first-line systemic therapy for metastatic EC involves CMT combined with immunotherapy. However, the efficacy of this regimen is limited by the liver's capacity for T-lymphocyte siphoning, where hepatic macrophages sequester CD8+ T cells. Notably, radiotherapy may overcome this limitation by eliminating immunosuppressive macrophages and reducing T-cell sequestration, thereby potentially enhancing immunotherapeutic response[18]. In a pilot study of 7 EC patients with liver metastases receiving systemic CMT plus proton beam radiotherapy to hepatic lesions, 5 patients concurrently received PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. This approach achieved a mOS of 35.5 months and a mPFS of 8.7 months[22]. Previous studies have proposed several mechanisms to explain the synergistic efficacy of combining radiotherapy with immunotherapy. These include: (1) The release of tumor antigens through local radiothe

Metastasectomy is considered potentially curative in certain cases. A retrospective cohort study of 34 patients with gastroesophageal cancer and liver or lung metastases reported a mOS of 52 months in the subgroup with esophageal liver metastasis (n = 11) following resection[25]. In contrast, Ichida et al[26] found only a borderline OS improvement (13 months vs 5 months, P = 0.06) in patients with recurrent disease who underwent resection compared with those who did not. These mixed outcomes, being consistent with our findings, demonstrate that the role of metastasectomy remains controversial and highlights the need for refined patient selection criteria.

TACE is frequently utilized for hepatic metastases. In a study of colorectal cancer (n = 98), drug-eluting bead TACE combined with systemic therapy significantly improved mPFS (12.1 months vs 8.4 months, P = 0.008) and DCR (87.0% vs 67.3%, P = 0.022) compared with systemic therapy alone[27]. However, data of TACE for EC patients are limited. In the present study, no significant benefit from TACE was identified, which might be due to sample size limitations, war

The present study demonstrated that combining local therapy with systemic treatment may improve outcomes in EC patients with liver metastases. Several mechanisms may underlie this synergistic effect, as supported by previous research. Localized treatment may induce the release of tumor antigens, thereby activating systemic immune responses, a phenomenon known as the abscopal effect. Immunotherapy, in turn, may sensitize tumors to local interventions by promoting ferroptosis. Additionally, local therapy has the potential to remodel the immunosuppressive liver microenvironment, which may mitigate the sequestration of T cells in the liver, thereby enhancing their survival and function in this organ[18,23,24]. These findings highlight the potential of an integrated treatment strategy, combining systemic therapy (e.g., CMT or chemoimmunotherapy) with aggressive local control of liver metastases, to enhance patient prognosis. Although this multimodal approach may enhance therapeutic efficacy, several critical challenges remain to be addressed, including the long-term survival benefits, the identification of the optimal patient population, the selection of appropriate local treatment modalities, the timing of intervention, and whether it can ultimately be regarded as a standard treatment regimen. In conclusion, research on EC with liver metastases is evolving from an emphasis on phenotypic evaluation toward a concentration on mechanistic elucidation and the implementation of precision-based interventions. Future studies should prioritize the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying liver metastasis, the dynamic characterization of the liver immune microenvironment, and the development of innovative interdisciplinary treatment strategies. These approaches may involve the combination of systemic therapies with local interventions, the integration of immunotherapy with anti-angiogenic agents, and the investigation of combined traditional Chinese medicine and Western therapeutic modalities. Addressing these pivotal challenges will necessitate the design and execution of rigorously structured phase III clinical trials.

The present study has several limitations. As a single-center, retrospective study with a relatively small proportion of EC patients with liver metastases, the limited sample size might introduce statistical bias, potentially impacting the generalizability and reliability of the findings. Additionally, although the groups were balanced, the proportion of male patients and those with ESCC was relatively high. Given that gender and primary tumor pathology may influence treatment response and prognosis, this could introduce potential bias. Furthermore, some patients who were initially diagnosed without distant organ metastasis underwent radical EC treatment before developing liver metastases. These patients might receive different treatment strategies during this period, potentially introducing confounding factors that could affect the comparison between treatment groups. With the advent of the immuno-oncology era, biomarker evaluation has become a notable element in predicting treatment response and guiding clinical decision-making, a concept widely accepted in the academic community. Studies on liver metastases have also indicated that resistance to immunotherapy may be linked to the expression levels of specific biomarkers. During the design phase of this study, the inclusion of biomarker testing was carefully considered. However, due to the extended timeline of the research, routine biomarker assessments, such as PD-L1 testing, had not yet become standard clinical practice at the outset of immunotherapy. This represents a limitation inherent to the study. It is acknowledged that future research should systematically incorporate key biomarkers into the core analytical framework. The next phase of our research will therefore include an expanded sample size and more rigorous prospective studies to obtain more precise results.

In conclusion, the present study examined and compared the efficacy of CMT + ICI as a first-line treatment for EC patients with liver metastases vs CMT alone. The results demonstrated that CMT + ICI was associated with superior efficacy and manageable adverse effects. Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified a KPS score of ≥ 70, local treatment for liver metastases, ≥ 4 cycles of CMT, and ≥ 4 cycles of immunotherapy as independent prognostic factors in these patients. It is noteworthy that the optimal treatment strategy for EC patients with liver metastases remains unde

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Professor Yu-Jin Xu from Zhejiang Cancer Hospital for his invaluable insights into the study design and his critical review of the manuscript. The authors also wish to thank Jin-Yu Wang for his assistance with the statistical analysis.

| 1. | Yang H, Wang F, Hallemeier CL, Lerut T, Fu J. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 2024;404:1991-2005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Arnold M, Ferlay J, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Soerjomataram I. Global burden of oesophageal and gastric cancer by histology and subsite in 2018. Gut. 2020;69:1564-1571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 70.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ding Y, Ren L, Geng Y, Fu C, Shi R. The Current Status and Prospects of Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Esophageal Cancer in China. Cancer Screen Prev. 2024;3:106-112. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Zheng YJ, Teng Y, He SY, Cao MD, Li QR, Tan NP, Wang JC, Zuo TT, Li TY, Xia CF, Chen WQ. [Epidemiological Characteristics of Esophageal CancerWorldwide and in China, 2022]. Zhongguo Zhongliu. 2025;34:165-170. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Tang X, Zhou X, Li Y, Tian X, Wang Y, Huang M, Ren L, Zhou L, Ding Z, Zhu J, Xu Y, Peng F, Wang J, Lu Y, Gong Y. A Novel Nomogram and Risk Classification System Predicting the Cancer-Specific Survival of Patients with Initially Diagnosed Metastatic Esophageal Cancer: A SEER-Based Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Robb WB, Messager M, Dahan L, Mornex F, Maillard E, D'Journo XB, Triboulet JP, Bedenne L, Seitz JF, Mariette C; Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive; Société Française de Radiothérapie Oncologique; Union des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer; Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie; French EsoGAstric Tumour working group - Fédération de Recherche En Chirurgie. Patterns of recurrence in early-stage oesophageal cancer after chemoradiotherapy and surgery compared with surgery alone. Br J Surg. 2016;103:117-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wu SG, Zhang WW, Sun JY, Li FY, Lin Q, He ZY. Patterns of Distant Metastasis Between Histological Types in Esophageal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2018;8:302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hsu PK, Wang BY, Huang CS, Wu YC, Hsu WH. Prognostic factors for post-recurrence survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients with recurrence after resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:558-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Earlam S, Glover C, Fordy C, Burke D, Allen-Mersh TG. Relation between tumor size, quality of life, and survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang J, Chang J, Yu H, Wu X, Wang H, Li W, Ji D, Peng W. A phase II study of oxaliplatin in combination with leucovorin and fluorouracil as first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:905-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sun JM, Shen L, Shah MA, Enzinger P, Adenis A, Doi T, Kojima T, Metges JP, Li Z, Kim SB, Cho BC, Mansoor W, Li SH, Sunpaweravong P, Maqueda MA, Goekkurt E, Hara H, Antunes L, Fountzilas C, Tsuji A, Oliden VC, Liu Q, Shah S, Bhagia P, Kato K; KEYNOTE-590 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2021;398:759-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 1080] [Article Influence: 216.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, Garrido M, Salman P, Shen L, Wyrwicz L, Yamaguchi K, Skoczylas T, Campos Bragagnoli A, Liu T, Schenker M, Yanez P, Tehfe M, Kowalyszyn R, Karamouzis MV, Bruges R, Zander T, Pazo-Cid R, Hitre E, Feeney K, Cleary JM, Poulart V, Cullen D, Lei M, Xiao H, Kondo K, Li M, Ajani JA. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:27-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1962] [Cited by in RCA: 2223] [Article Influence: 444.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Luo H, Lu J, Bai Y, Mao T, Wang J, Fan Q, Zhang Y, Zhao K, Chen Z, Gao S, Li J, Fu Z, Gu K, Liu Z, Wu L, Zhang X, Feng J, Niu Z, Ba Y, Zhang H, Liu Y, Zhang L, Min X, Huang J, Cheng Y, Wang D, Shen Y, Yang Q, Zou J, Xu RH; ESCORT-1st Investigators. Effect of Camrelizumab vs Placebo Added to Chemotherapy on Survival and Progression-Free Survival in Patients With Advanced or Metastatic Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: The ESCORT-1st Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;326:916-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 557] [Article Influence: 111.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gao J, Song Y, Kou X, Tan Z, Zhang S, Sun M, Zhou J, Fan M, Zhang M, Song Y, Li S, Yuan Y, Zhuang W, Zhang J, Zhang L, Jiang H, Gu K, Ye H, Ke Y, Qi X, Wang Q, Zhu J, Huang J. The effect of liver metastases on clinical efficacy of first-line programmed death-1 inhibitor plus chemotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A post hoc analysis of ASTRUM-007 and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e7203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu Y, Ren Z, Yuan L, Xu S, Yao Z, Qiao L, Li K. Paclitaxel plus cisplatin vs. 5-fluorouracil plus cisplatin as first-line treatment for patients with advanced squamous cell esophageal cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:2345-2350. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Okadome K, Baba Y, Yasuda-Yoshihara N, Nomoto D, Yagi T, Toihata T, Ogawa K, Sawayama H, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Iwagami S, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N, Watanabe M, Komohara Y, Baba H. PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression status in relation to chemotherapy in primary and metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2022;113:399-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wei XL, Luo X, Sheng H, Wang Y, Chen DL, Li JN, Wang FH, Xu RH. PD-L1 expression in liver metastasis: its clinical significance and discordance with primary tumor in colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 2020;18:475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yu J, Green MD, Li S, Sun Y, Journey SN, Choi JE, Rizvi SM, Qin A, Waninger JJ, Lang X, Chopra Z, El Naqa I, Zhou J, Bian Y, Jiang L, Tezel A, Skvarce J, Achar RK, Sitto M, Rosen BS, Su F, Narayanan SP, Cao X, Wei S, Szeliga W, Vatan L, Mayo C, Morgan MA, Schonewolf CA, Cuneo K, Kryczek I, Ma VT, Lao CD, Lawrence TS, Ramnath N, Wen F, Chinnaiyan AM, Cieslik M, Alva A, Zou W. Liver metastasis restrains immunotherapy efficacy via macrophage-mediated T cell elimination. Nat Med. 2021;27:152-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 752] [Article Influence: 150.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:328rv4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1564] [Cited by in RCA: 1957] [Article Influence: 195.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hato SV, Khong A, de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ. Molecular pathways: the immunogenic effects of platinum-based chemotherapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2831-2837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhou F, Yu X, Liang P, Cheng Z, Han Z, Yu J, Liu F, Tan S, Dai G, Bai L. Combined microwave ablation and systemic chemotherapy for liver metastases from oesophageal cancer: Preliminary results and literature review. Int J Hyperthermia. 2016;32:524-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yamaguchi H, Kato T, Honda M, Hamada K, Seto I, Tominaga T, Takagawa Y, Takayama K, Suzuki M, Kikuchi Y, Teranishi Y, Murakami M. Effectiveness of proton beam therapy for liver oligometastatic recurrence in patients with postoperative esophagus cancer. J Radiat Res. 2023;64:582-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lang X, Green MD, Wang W, Yu J, Choi JE, Jiang L, Liao P, Zhou J, Zhang Q, Dow A, Saripalli AL, Kryczek I, Wei S, Szeliga W, Vatan L, Stone EM, Georgiou G, Cieslik M, Wahl DR, Morgan MA, Chinnaiyan AM, Lawrence TS, Zou W. Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy Promote Tumoral Lipid Oxidation and Ferroptosis via Synergistic Repression of SLC7A11. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1673-1685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 819] [Article Influence: 117.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ashrafizadeh M, Farhood B, Eleojo Musa A, Taeb S, Rezaeyan A, Najafi M. Abscopal effect in radioimmunotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;85:106663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Seesing MFJ, van der Veen A, Brenkman HJF, Stockmann HBAC, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Rosman C, van den Wildenberg FJH, van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Duijvendijk P, Wijnhoven BPL, Stoot JHMB, Lacle M, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R; Gastroesophageal Metastasectomy Group. Resection of hepatic and pulmonary metastasis from metastatic esophageal and gastric cancer: a nationwide study. Dis Esophagus. 2019;32:doz034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ichida H, Imamura H, Yoshimoto J, Sugo H, Kajiyama Y, Tsurumaru M, Suzuki K, Ishizaki Y, Kawasaki S. Pattern of postoperative recurrence and hepatic and/or pulmonary resection for liver and/or lung metastases from esophageal carcinoma. World J Surg. 2013;37:398-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang F, Chen L, Bin C, Cao Y, Wang J, Zhou G, Zheng C. Drug-eluting beads transcatheter arterial chemoembolization combined with systemic therapy versus systemic therapy alone as first-line treatment for unresectable colorectal liver metastases. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1338293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/