Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.113099

Revised: September 21, 2025

Accepted: November 20, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 150 Days and 23.8 Hours

Sorafenib has been the conventional treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) since 2008. While radiological complete responses are extremely rare, improved supportive care and multidisciplinary approaches in clinical prac

This case series describes 3 patients with advanced HCC who achieved durable complete responses using first-line sorafenib therapy, even in the presence of por

Future research into the etiology and molecular differences in HCC is necessary to develop more personalized therapy options.

Core Tip: Complete responses to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma are extremely rare. This case series reports 3 patients who, despite having advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with features like portal vein thrombosis and extrahepatic spread, achieved durable complete responses on sorafenib therapy. Predictive biomarkers for sorafenib response remain unknown, although dermatologic toxicity and non-viral etiology may be associated with favorable outcomes. These findings support the continued utility of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in selected patients, particularly when immunotherapy is contraindicated or unavailable.

- Citation: Lučev H, Adžić G, Pleština S, Prejac J. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma achieving a complete response to sorafenib: Three case reports and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(1): 113099

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i1/113099.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.113099

Primary liver cancer is the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related death. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer, accounting for 75%-85% of all cases[1]. Although curative methods are available for the 40%-50% of patients diagnosed at an early stage, most in

Immunotherapy combinations have demonstrated superior overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), overall response rates (ORRs), and complete response (CR) rates compared to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). TKIs such as sorafenib and lenvatinib remain effective first-line alternatives when immunotherapy is contraindicated[4]. TKIs are multikinase inhibitors that mainly target the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor, rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma protein receptor, fibroblast growth factor receptor, KIT receptor, and rearranged during transfection receptor[5]. Their mechanism of action involves the inhibition of tyrosine kinase receptors, which are responsible for cellular proliferation and angiogenesis through the signal transduction pathway. Some TKIs also exert immunomodulatory effects by influencing the tumor microenvironment[6]. Sorafenib, a VEGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and RAF kinase inhibitor, has been the standard of care for first-line treatment of advanced HCC since 2008.

The phase 3, prospective, multicenter randomized SHARP trial demonstrated a benefit in OS, with a median survival of 10.7 months for patients receiving treatment compared to 7.9 months in the placebo group[7]. These findings were later confirmed by a separate Phase 3 Asia-Pacific study[8]. While no cases of CR were reported in these two studies, sporadic cases of CR have been observed in other trials where sorafenib was used as a comparator[9], as well as in retrospective analyses[10,11] and case reports[12-18]. Real-world data and recent studies have revealed a considerable improvement in OS and ORR with sorafenib, surpassing the outcomes initially reported in its registration trials. The exact reasons for this upward trend are not fully understood, but potential contributing factors may include advancements in supportive care, a rise in multidisciplinary management approaches, and effective treatments for hepatitis C[9,19]. This case series presents 3 patients undergoing treatment at the University Hospital Centre Zagreb (Zagreb, Croatia). All of the patients were diagnosed with advanced HCC, began treatment with sorafenib, and experienced a CR. The third case was previously described in a separate case report[12].

Case 1: Persistent right upper quadrant abdominal pain lasting for more than 1 year.

Case 2: The patient was asymptomatic and presented during routine follow-up for known liver cirrhosis.

Case 3: Right lumbar pain of several weeks’ duration.

Case 1: A 63-year-old man was evaluated for ongoing pain in the upper quadrant of his abdomen in April 2020. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a 3.5-cm lesion in segment IVb of the liver. A subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed imaging features consistent with HCC. Preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) was elevated at 111 ng/mL, exceeding the normal range of < 10 ng/mL.

Case 2: A 55-year-old man with a history of cryptogenic liver cirrhosis, first diagnosed following variceal bleeding in 2018.

Case 3: The patient was a 73-year-old man who reported to the Emergency Department in August 2020 with right lumbar pain. The patient had liver cirrhosis; however, no underlying etiology except metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease was found.

Case 1: The patient had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus infection that had been previously treated with interferon in the 1990s.

Case 2: The patient had a medical history of arterial hypertension and cholelithiasis.

Case 3: There was no significant past medical history.

The three patients reported no family history of malignancy or liver disease or other significant comorbidities.

All three patients’ physical examination findings were unremarkable.

Case 1: Baseline laboratory evaluation demonstrated preserved hepatic function and elevated AFP (111 ng/mL) prior to surgery.

Case 2: At the initiation of systemic therapy, the AFP level was significantly elevated at 2500 ng/mL.

Case 3: Serum AFP was 17.3 ng/mL, with all other laboratory parameters falling within normal range.

Case 1: Initial abdominal ultrasound and subsequent multiphasic CT demonstrated a 3.5-cm hepatic lesion in segment IVb, which displayed imaging characteristics consistent with HCC.

Case 2: Two lesions, each 5 cm in size, were found on ultrasound in liver segments VIII and IV during routine follow-up in February 2021. Lesions had radiological characteristics consistent with HCC on follow-up CT.

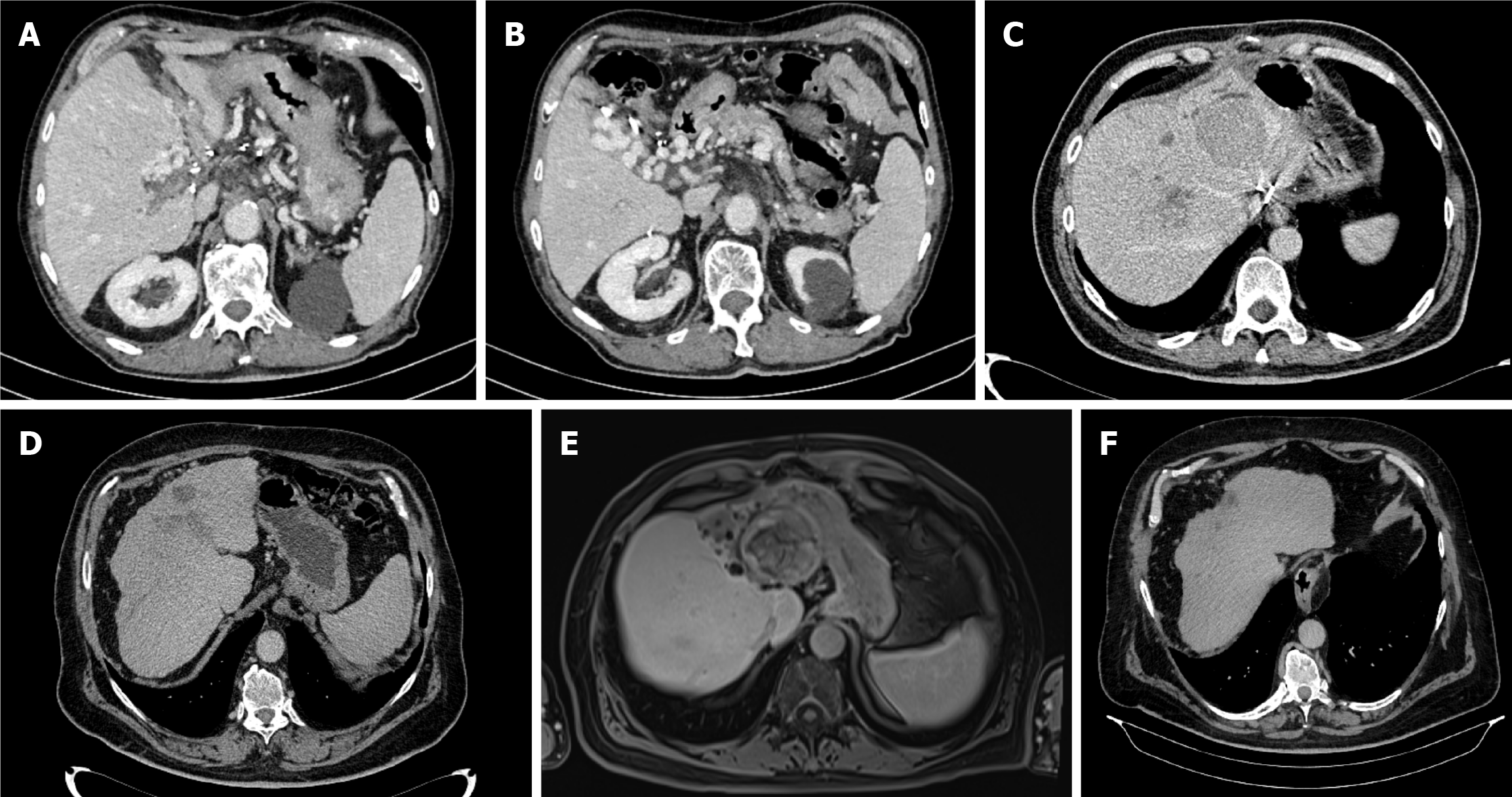

Case 3: Further workup, which included a multislice CT scan of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, identified a 7-cm mass in the liver’s caudate lobe, accompanied by portal and splenic vein thrombosis (Figure 1A and B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen showed no additional lesions. Due to the lesion’s proximity to major vascular structures, a biopsy was not performed.

All three patients, based on the radiological characteristics, a diagnosis of HCC was established.

The lesion was surgically resected in May 2020. The pathohistological report confirmed a diagnosis of HCC characterized by significant invasion into small blood vessels and the capsule surrounding the liver. The remaining liver tissue showed no sign of cirrhosis. The patient was closely monitored until October 2021, at which point new lesions were found in liver segments III, VIII, I, and IV, accompanied by portal vein thrombosis. The AFP value at the time was 7.5 ng/mL. The pa

Since the disease did not meet the Milan criteria, radiofrequency ablation was performed in March 2021. Follow-up positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging revealed progression in the size of both lesions, which remained me

An atypical caudate lobe resection was performed in September 2020, following the decision that surgical removal was the optimal treatment approach. According to the pathohistological report, the tumor was a grade 3 HCC and staged at T4N0M0, with no perineural or lymphovascular invasion observed; however, the surgical margin was close, measuring less than 1 mm. On the October 2020 post-resection MRI, a new 1.3-cm lesion was identified in the VI segment, along with portal vein tumor thrombosis. Following a review by the MDT, a decision was made to initiate systemic treatment with sorafenib. The patient’s AFP level was 4.1 ng/mL; his CP class was A5, and his Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 0. Sorafenib therapy was initiated in October 2020 at the standard dosage of 400 mg twice daily. After the first cycle, the patient developed a maculopapular rash on his hands and feet. After the sixth cycle, the patient developed grade 2 diarrhea, according to CTCAE guidelines. As a result, the sorafenib dosage had to be reduced to 200 mg twice daily.

An MRI scan in March 2024 showed that the largest lesion in liver segment III was 55 mm. This area, along with all of the other lesions, appeared to have undergone complete necrosis with no viable tumor cells found (Figure 1E). The patient was re-evaluated by the MDT as a potential liver transplantation candidate; however, the procedure was deemed sur

The patient’s treatment continued until October 2024, but was subsequently paused and ultimately discontinued due to the development of grade 2 thrombocytopenia per CTCAE. A follow-up PET-CT scan conducted in October 2024 revealed no evidence of metabolically active lesions. The last imaging follow-up was a CT scan in April 2025, which showed no signs of a viable tumor, and the AFP value was 2 ng/mL (Figure 1F).

On the first follow-up CT scan, no lesion was visualized in the VI segment, a finding that remained consistent across subsequent CT scans repeated every 2 months. Additionally, the AFP levels remained within the normal range. The patient was treated with sorafenib until February 2024, at which point treatment was stopped. Follow-up imaging in October 2024 revealed no evidence of active disease, and the patient remains under close surveillance.

All patients were treated with sorafenib, which was the standard of care in the Republic of Croatia at the time due to the unavailability of immunotherapy. Notably, all patients in this case series achieved a CR. Although the treatment of HCC has significantly advanced with the introduction of immunotherapy, a subset of patients continues to receive TKIs as first-line therapy. This is typically due to contraindications to immunotherapy, concerns about potential side effects, or specific exclusion criteria from clinical trials, such as a history of variceal bleeding or the presence of portal vein throm

However, the question of when to choose a TKI over immunotherapy in the first-line setting remains unresolved, primarily due to the lack of reliable biomarkers to predict treatment response. To date, AFP level ≥ 400 ng/mL remains the only validated positive predictive biomarker, specifically for the use of ramucirumab in the second-line setting[21]. Two studies have shown that tracking the decline of AFP levels could serve as a surrogate marker for PFS in patients with baseline levels > 20 μg/L; specifically, a reduction of > 20% after 6 weeks of sorafenib is notable[22,23]. However, not all patients with metastatic disease present with elevated AFP levels at diagnosis; importantly, in all 3 of our cases, AFP was below the limit of detection when a CR was achieved (Table 1). Both CP and BCLC staging systems have consistently shown across prospective studies, registries, and pooled trial analyses to predict survival in patients with HCC receiving sorafenib, with better outcomes observed in patients with preserved liver function (CP-A) and less advanced disease (BCLC-B). Patients with more severe liver impairment (CP-B) and advanced cancer (BCLC-C) experience significantly less benefit. This prognostic pattern holds true for newer immune checkpoint inhibitor combination therapies as well[24,25].

| Timepoint1 | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

| At diagnosis | 111 | 2508 | 17.3 |

| At initiation of sorafenib treatment | 7.5 | 2837 | 4.1 |

| At first radiological appearance of a complete response | < 2.0 | 2.1 | < 2.0 |

| Last available measurement | 3.0 | < 2.0 | < 2.0 |

Some evidence suggests that patients who experience adverse events, particularly dermatologic and gastrointestinal toxicities, may have a favorable response to sorafenib treatment. Among these, HFSR is most consistently associated with better survival, as multiple retrospective and prospective analyses have demonstrated significantly longer PFS and OS in patients who develop early or higher grade HFSR compared to those without this dermatologic toxicity[26,27]. This association is believed to reflect adequate systemic drug exposure and effective inhibition of the rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma/VEGFR pathway within both tumor and endothelial cells. Similarly, gastrointestinal adverse events, most notably diarrhea, have also been correlated with favorable treatment outcomes, possibly due to shared mechanisms of kinase inhibition affecting epithelial and vascular signaling pathways[28].

Beyond clinical observations, metabolomic profiling studies have revealed that sorafenib induces profound re

Several established risk models exist specifically for patients receiving sorafenib, with the PROSASH and PROSASH-II models being the most extensively validated. These models incorporate a range of objective clinical variables, including serum albumin and bilirubin, baseline AFP levels, the presence of macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic spread, and the size of the largest intrahepatic tumor lesion. Of note, PROSASH-II demonstrated superior discriminatory performance compared to older models such as the Hepatoma Arterial-embolization Prognostic score and its variant Sorafenib Ad

One of the prognostic markers being researched is the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, which serves as a marker of systemic inflammation, and if elevated, indicates worse outcomes[31]. C-reactive protein, another marker of systemic in

These prognostic models show promise, but are not yet reliable tools for treatment selection because they have not been sufficiently validated across heterogeneous populations or confirmed through prospective studies. In this context, our findings provide additional observational insights. Two of the three patients (patients 2 and 3) experienced der

Another important question is the optimal duration of sorafenib treatment following a CR. In this series, patients received sorafenib for 32, 29, and 40 months, respectively. In similar published case series, the median treatment duration was about 40 months[10]. Some reports suggest that discontinuing sorafenib after achieving a CR does not negatively impact OS or RR, while potentially improving quality of life[34]. However, due to the limited number of patients ac

Our patients responded remarkably well to sorafenib treatment. However, if they developed HCC today, they would probably receive a different first-line therapy, and we can only speculate about the outcomes of that alternative treatment. Therefore, future research is necessary to better understand personalized therapy options for HCC, considering variations in etiology and molecular characteristics.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12600] [Article Influence: 6300.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, Maini MK, Mazzaferro V, Pinato DJ, Pikarsky E, Zhu AX, Finn RS. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:151-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 1218] [Article Influence: 304.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 4436] [Article Influence: 887.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Vogel A, Chan SL, Dawson LA, Kelley RK, Llovet JM, Meyer T, Ricke J, Rimassa L, Sapisochin G, Vilgrain V, Zucman-Rossi J, Ducreux M; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2025;36:491-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Galle PR, Dufour JF, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Trojan J, Vogel A. Systemic therapy of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2021;17:1237-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cao M, Xu Y, Youn JI, Cabrera R, Zhang X, Gabrilovich D, Nelson DR, Liu C. Kinase inhibitor Sorafenib modulates immunosuppressive cell populations in a murine liver cancer model. Lab Invest. 2011;91:598-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Häussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10525] [Article Influence: 584.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 8. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, Xu J, Sun Y, Liang H, Liu J, Wang J, Tak WY, Pan H, Burock K, Zou J, Voliotis D, Guan Z. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3854] [Cited by in RCA: 4738] [Article Influence: 263.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Lim HY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Ma N, Nicholas A, Wang Y, Li L, Zhu AX, Finn RS. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76:862-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 1167] [Article Influence: 291.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rimola J, Díaz-González Á, Darnell A, Varela M, Pons F, Hernandez-Guerra M, Delgado M, Castroagudin J, Matilla A, Sangro B, Rodriguez de Lope C, Sala M, Gonzalez C, Huertas C, Minguez B, Ayuso C, Bruix J, Reig M. Complete response under sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Relationship with dermatologic adverse events. Hepatology. 2018;67:612-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Brown TJ, Gupta A, Sedhom R, Beg MS, Karasic TB, Yarchoan M. Trends of Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with First-Line Sorafenib in Randomized Controlled Trials. Gastrointest Tumors. 2022;9:19-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Adžić G, Prejac J, Pleština S. Long-term follow-up of complete remission in a patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib: a case report. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1260989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hagihara A, Teranishi Y, Kawamura E, Fujii H, Iwai S, Morikawa H, Enomoto M, Tamori A, Kawada N. A complete response induced by 21-day sorafenib therapy in a patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Intern Med. 2013;52:1589-1592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu D, Liu A, Peng J, Hu Y, Feng X. Case analysis of complete remission of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma achieved with sorafenib. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Katafuchi E, Takami Y, Wada Y, Tateishi M, Ryu T, Mikagi K, Saitsu H. Long-Term Maintenance of Complete Response after Sorafenib Treatment for Multiple Lung Metastases from Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2015;9:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shiozawa K, Watanabe M, Ikehara T, Matsukiyo Y, Kogame M, Kanayama M, Matsui T, Kikuchi Y, Ishii K, Igarashi Y, Sumino Y. Sustained complete response of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus following discontinuation of sorafenib: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:50-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Park JG, Tak WY, Park SY, Kweon YO, Jang SY, Lee SH, Lee YR, Jang SK, Hur K, Lee HJ. Long-term follow-up of complete remission of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following sorafenib therapy: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:4853-4856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Huang KW, Lee PC, Chao Y, Su CW, Lee IC, Lan KH, Chu CJ, Hung YP, Chen SC, Hou MC, Huang YH. Durable objective response to sorafenib and role of sequential treatment in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2022;14:17588359221099401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sangro B, Chan SL, Kelley RK, Lau G, Kudo M, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Yarchoan M, De Toni EN, Furuse J, Kang YK, Galle PR, Rimassa L, Heurgué A, Tam VC, Van Dao T, Thungappa SC, Breder V, Ostapenko Y, Reig M, Makowsky M, Paskow MJ, Gupta C, Kurland JF, Negro A, Abou-Alfa GK; HIMALAYA investigators. Four-year overall survival update from the phase III HIMALAYA study of tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:448-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 94.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rimini M, Rimassa L, Ueshima K, Burgio V, Shigeo S, Tada T, Suda G, Yoo C, Cheon J, Pinato DJ, Lonardi S, Scartozzi M, Iavarone M, Di Costanzo GG, Marra F, Soldà C, Tamburini E, Piscaglia F, Masi G, Cabibbo G, Foschi FG, Silletta M, Pressiani T, Nishida N, Iwamoto H, Sakamoto N, Ryoo BY, Chon HJ, Claudia F, Niizeki T, Sho T, Kang B, D'Alessio A, Kumada T, Hiraoka A, Hirooka M, Kariyama K, Tani J, Atsukawa M, Takaguchi K, Itobayashi E, Fukunishi S, Tsuji K, Ishikawa T, Tajiri K, Ochi H, Yasuda S, Toyoda H, Ogawa C, Nishimur T, Hatanaka T, Kakizaki S, Shimada N, Kawata K, Tanaka T, Ohama H, Nouso K, Morishita A, Tsutsui A, Nagano T, Itokawa N, Okubo T, Arai T, Imai M, Naganuma A, Koizumi Y, Nakamura S, Joko K, Iijima H, Hiasa Y, Pedica F, De Cobelli F, Ratti F, Aldrighetti L, Kudo M, Cascinu S, Casadei-Gardini A. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus lenvatinib or sorafenib in non-viral unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: an international propensity score matching analysis. ESMO Open. 2022;7:100591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, Assenat E, Brandi G, Pracht M, Lim HY, Rau KM, Motomura K, Ohno I, Merle P, Daniele B, Shin DB, Gerken G, Borg C, Hiriart JB, Okusaka T, Morimoto M, Hsu Y, Abada PB, Kudo M; REACH-2 study investigators. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:282-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1027] [Cited by in RCA: 1313] [Article Influence: 187.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Yau T, Yao TJ, Chan P, Wong H, Pang R, Fan ST, Poon RT. The significance of early alpha-fetoprotein level changes in predicting clinical and survival benefits in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving sorafenib. Oncologist. 2011;16:1270-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Personeni N, Bozzarelli S, Pressiani T, Rimassa L, Tronconi MC, Sclafani F, Carnaghi C, Pedicini V, Giordano L, Santoro A. Usefulness of alpha-fetoprotein response in patients treated with sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;57:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brunetti O, Gnoni A, Licchetta A, Longo V, Calabrese A, Argentiero A, Delcuratolo S, Solimando AG, Casadei-Gardini A, Silvestris N. Predictive and Prognostic Factors in HCC Patients Treated with Sorafenib. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55:707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chan SL, Kudo M, Sangro B, Kelley R, Kim J, Van Binh P, Hong J, Waldschmidt D, Marino D, Gerolami R, Li Q, Nakamura H, Sun P, Baur B, Rimassa L. 150MO Safety results from the phase IIIb SIERRA study of durvalumab (D) and tremelimumab (T) as first-line (1L) treatment (tx) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) participants (pts) with a poor prognosis. Ann Oncol. 2025;36:S63-S64. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Reig M, Torres F, Rodriguez-Lope C, Forner A, LLarch N, Rimola J, Darnell A, Ríos J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. Early dermatologic adverse events predict better outcome in HCC patients treated with sorafenib. J Hepatol. 2014;61:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Díaz-González Á, Sanduzzi-Zamparelli M, Sapena V, Torres F, LLarch N, Iserte G, Forner A, da Fonseca L, Ríos J, Bruix J, Reig M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the critical role of dermatological events in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:482-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Koschny R, Gotthardt D, Koehler C, Jaeger D, Stremmel W, Ganten TM. Diarrhea is a positive outcome predictor for sorafenib treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2013;84:6-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pedretti S, Palermo F, Braghin M, Imperato G, Tomaiuolo P, Celikag M, Boccazzi M, Vallelonga V, Da Dalt L, Norata GD, Marisi G, Rapposelli IG, Casadei-Gardini A, Ghisletti S, Crestani M, De Fabiani E, Mitro N. D-lactate and glycerol as potential biomarkers of sorafenib activity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sansone V, Tovoli F, Casadei-Gardini A, Di Costanzo GG, Magini G, Sacco R, Pressiani T, Trevisani F, Rimini M, Tortora R, Nardi E, Ielasi L, Piscaglia F, Granito A. Comparison of Prognostic Scores in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated With Sorafenib. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021;12:e00286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Muhammed A, Fulgenzi CAM, Dharmapuri S, Pinter M, Balcar L, Scheiner B, Marron TU, Jun T, Saeed A, Hildebrand H, Muzaffar M, Navaid M, Naqash AR, Gampa A, Ozbek U, Lin JY, Perone Y, Vincenzi B, Silletta M, Pillai A, Wang Y, Khan U, Huang YH, Bettinger D, Abugabal YI, Kaseb A, Pressiani T, Personeni N, Rimassa L, Nishida N, Di Tommaso L, Kudo M, Vogel A, Mauri FA, Cortellini A, Sharma R, D'Alessio A, Ang C, Pinato DJ. The Systemic Inflammatory Response Identifies Patients with Adverse Clinical Outcome from Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;14:186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Scheiner B, Pomej K, Kirstein MM, Hucke F, Finkelmeier F, Waidmann O, Himmelsbach V, Schulze K, von Felden J, Fründt TW, Stadler M, Heinzl H, Shmanko K, Spahn S, Radu P, Siebenhüner AR, Mertens JC, Rahbari NN, Kütting F, Waldschmidt DT, Ebert MP, Teufel A, De Dosso S, Pinato DJ, Pressiani T, Meischl T, Balcar L, Müller C, Mandorfer M, Reiberger T, Trauner M, Personeni N, Rimassa L, Bitzer M, Trojan J, Weinmann A, Wege H, Dufour JF, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Vogel A, Pinter M. Prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with immunotherapy - development and validation of the CRAFITY score. J Hepatol. 2022;76:353-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | El-Sheshtawy AM, Werida RH, Bahgat MH, El-Etreby S, El-Bassiouny NA. Pharmacogenomic insights: IL-23R and ATG-10 polymorphisms in Sorafenib response for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Med. 2025;25:51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhang Y, Fan W, Zhu K, Lu L, Fu S, Huang J, Wang Y, Yang J, Huang Y, Yao W, Li J. Sorafenib continuation or discontinuation in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma after a complete response. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24550-24559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/