Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.113988

Revised: October 15, 2025

Accepted: November 3, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 93 Days and 23.6 Hours

Risk prediction has long been a cornerstone of surgical oncology, enabling surgeons to anticipate complications, tailor perioperative care, and improve out

Core Tip: Risk prediction in surgical oncology is evolving beyond traditional scoring systems. Frequentist methods, widely used in machine learning, offer transparency and reproducibility but rely solely on observed data. Bayesian reasoning, by contrast, integrates prior clinical knowledge with new information, mirroring real-world decision-making. The integration of both frameworks promises more reliable, interpretable, and personalized prediction tools, advancing the future of surgical care.

- Citation: Tustumi F, Maegawa FAB, Serrano Uson Junior PL. Beyond the blank page: Frequentist and Bayesian perspectives on risk prediction algorithms. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(12): 113988

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i12/113988.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.113988

Risk prediction has always been central to surgical oncology. Anticipating which patients are more likely to experience complications allows surgeons to select patients for surgery, determine the optimal timing for surgery, optimize perioperative care, and ultimately improve outcomes. In recent years, new tools have emerged to refine this task. Machine learning (ML) and other artificial intelligence (AI) strategies are increasingly being applied to surgical prediction models, offering the promise of individualized estimates that can outperform traditional clinical scoring systems.

The recent study by An et al[1] represents a significant advance in this direction. In a retrospective cohort of more than 500 patients undergoing radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer, the authors developed predictive models for delayed wound healing, a complication with substantial clinical consequences. Using readily available clinical variables-sex, age, duration of abdominal drainage, and hematologic parameters-they compared the performance of three algorithms: Decision trees, support vector machines (SVMs), and logistic regression. Their results showed that decision trees achieved the best accuracy, recall, and F1 scores, underscoring both the feasibility and the potential of ML in surgical oncology.

Delayed wound healing is not merely a technical concern. It prolongs hospitalization, increases costs, predisposes to secondary infections, and delays the initiation of adjuvant therapies[2]. For patients with gastric cancer, where timely adjuvant treatment may determine survival, predictive models that identify high-risk patients are highly relevant.

The study by An et al[1] follows the statistical tradition most widely applied in medical research: The frequentist framework. In this approach, inference is typically built on the logic of hypothesis testing, where the null hypothesis (H0) is either rejected or accepted based on observed data. Within this paradigm, different ML algorithms can be applied to the same clinical question, each with distinct strategies for “learning” from data.

Logistic regression, one of the most established methods, models the probability of an outcome (such as delayed wound healing) as a function of several covariates. The resulting coefficients can be directly interpreted as odds ratios, which makes the model familiar to clinicians and easy to translate into risk scores. Its strength lies in transparency, but it does not capture complex nonlinear relationships unless interaction terms are explicitly introduced.

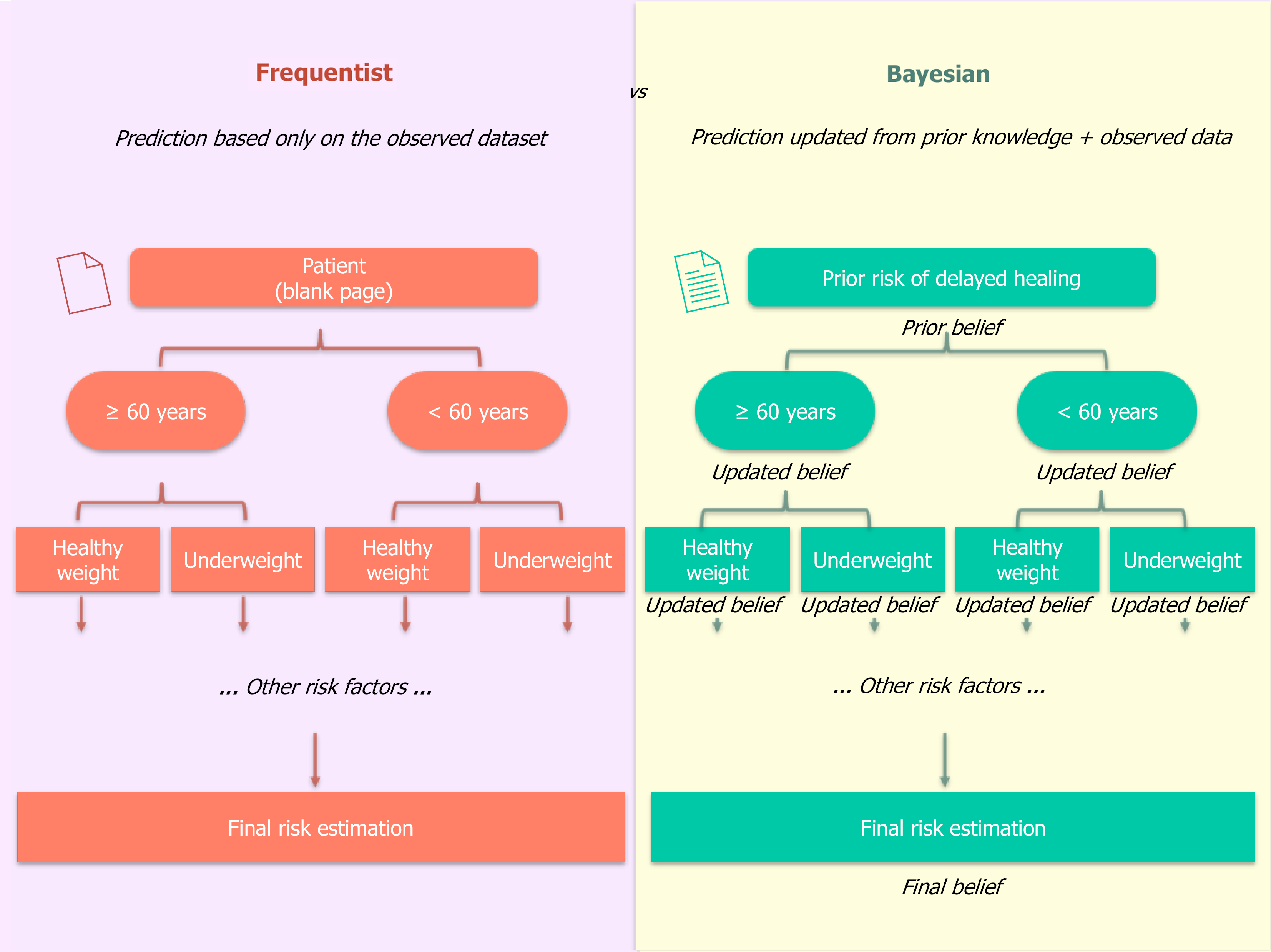

Decision trees take a different approach. Instead of modeling probabilities as a smooth function of predictors, they split the patient population into progressively smaller subgroups based on covariates. At each branch, the model asks a yes/no question. For example, it might first split patients based on age ≥ 60, then further split the older group based on body mass index (BMI) < 18.5, and so on, eventually reaching terminal "leaves" that assign a risk probability based on the proportion of events in that specific subgroup within the training data. This structure is highly interpretable, mirroring clinical decision pathways. However, it can be unstable, and the probabilities at each leaf are simple sample frequencies from the current dataset, starting from a "blank page" for each new patient.

SVMs, in contrast, are less intuitive but powerful in high-dimensional spaces. Rather than estimating probabilities, they focus on classification, drawing an optimal boundary (or hyperplane) that maximally separates patients with and without delayed healing. This can be especially useful when predictors are numerous or when relationships between them are not easily captured by traditional regression. However, because SVMs operate in a more abstract mathematical space, their predictions are more complex to interpret clinically.

Despite their methodological differences, these models share a common foundation: They rely exclusively on the observed dataset. They do not formally incorporate prior clinical knowledge, and they often treat covariates as inde

The Bayesian framework recognizes that each analysis builds upon what is already known, rather than assuming a blank page. Instead, it formally incorporates prior knowledge into the estimation process. Existing knowledge-whether derived from previous studies or institutional outcomes-is incorporated as a prior probability, which is then updated with new data to generate a posterior probability that reflects both past evidence and current observations. In this way, Bayesian inference reflects not only what is observed in the dataset but also the cumulative history of evidence, closely mirroring the reasoning process of surgeons at the bedside: The more information we accumulate-whether from a patient’s history, images, laboratory tests, or even clinical experience-the more refined and accurate our clinical judgment becomes. Bayesian models, therefore, generate probabilities that are both mathematically coherent and clinically aligned with how physicians reason: Integrating what is already known with what is newly observed.

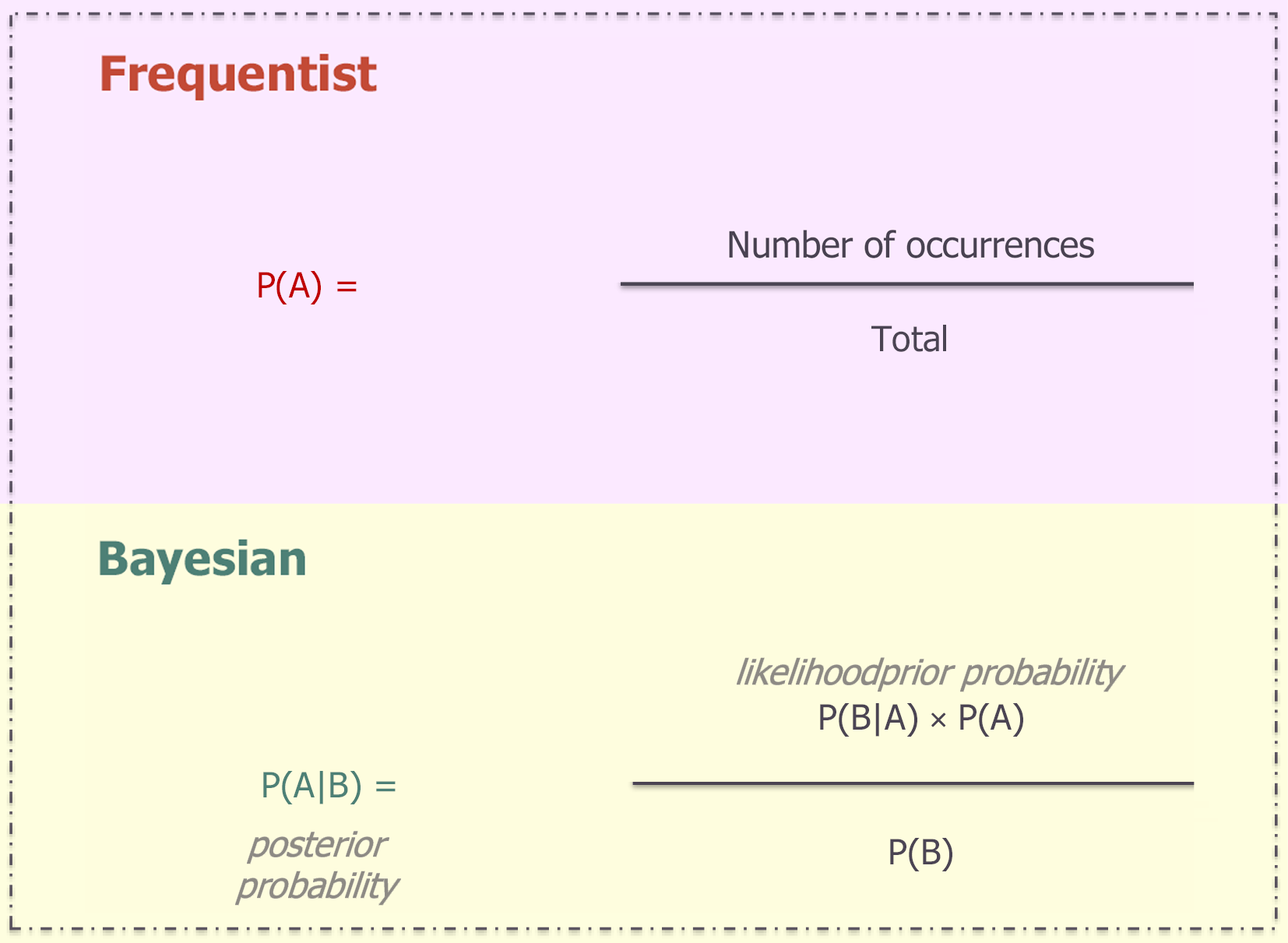

On the mathematical point of view, Bayes’ theorem[2] states that the posterior probability of a hypothesis (H), given new data (D), is proportional to the likelihood of the data if the hypothesis were true, multiplied by the prior probability of the hypothesis, and normalized by the overall probability of the data (Figure 1).

Consider a patient undergoing radical gastrectomy for cancer. In a frequentist decision tree, being elderly may increase the observed probability of delayed healing (Figure 2). If the patient is also underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) with prolonged abdominal drainage, the estimated risk rises further, based solely on stratified frequencies in the dataset. In multivariable logistic regression, covariates are modeled simultaneously, as was done appropriately in the study by An et al[1]. However, like other frequentist models, SVMs and logistic regression rely exclusively on the observed dataset and do not formally integrate prior clinical knowledge. For example, sex and BMI are not independent variables: Men tend to have higher BMI values than women, which modifies how nutritional status influences surgical outcomes, while advanced age and impaired immune response often act synergistically to delay tissue repair[3,4]. In a Bayesian model, by contrast, we begin with a prior probability of delayed healing derived from prior evidence. This prior is then updated as we incorporate new information: Elderly status, sex, elevated preoperative white blood cell count, or high neutrophil levels. Each factor does not simply add to the risk; instead, prior knowledge about their interconnected impact informs how the posterior probability is shaped. In this way, Bayesian inference allows clinical intuition to be formally encoded into the prediction. In practice, this means that the statistical result is closer to the clinical question: A statistical point of view, this means that the statistical result is closer to the clinical question: Instead of a P value or rigid classification, the physician obtains the direct probability of benefit or adverse event for that specific patient[5].

Despite these advantages, Bayesian methods are not without significant limitations. The quality of their predictions depends heavily on the specification of prior distributions, which, if chosen poorly or based on limited evidence, may bias the results rather than refine them. Frequentist approaches are more straightforward to implement and easier to interpret. Their reliance solely on observed data, while sometimes restrictive, also ensures transparency and reproducibility without the need to justify prior assumptions.

The study by An et al[1] is a valuable addition to the literature and an important step in bringing AI-driven prediction closer to surgical practice. By identifying relevant variables and demonstrating the feasibility of predictive modeling, the authors provide an essential foundation for more personalized perioperative care. Their work also invites a broader reflection on methodological choices in the field. Frequentist models remain the cornerstone of medical research due to their well-established transparency, reproducibility, and straightforward implementation. Bayesian approaches, however, offer a powerful complement by formally incorporating prior knowledge, a process that closely mirrors the way clinicians reason in practice.

The choice between models is context-dependent. In scenarios with sparse data-such as early-phase exploratory research or studies of rare conditions-Bayesian methods are particularly valuable, as they formally integrate prior evidence. This approach directly formalizes the implicit 'pre-test probability' that experienced surgical oncologists intuitively apply, derived from their individual experience, patient comorbidities, and institutional context. Conversely, for large multicenter datasets where reproducibility and simplicity are paramount, frequentist approaches often remain the standard. From a development perspective, each framework offers distinct advantages. The Frequentist framework, with its requirement for a fixed sample size and reliance on p-values for error control, provides a clear benchmark. Bayesian methodology, however, can enhance model stability, especially in small samples or high-dimensional data, by "borrowing strength" from prior information to avoid extreme estimates[6].

Given that both paradigms have merits, the focus should not be on choosing one over the other, but on their integration. Operationalizing this integration is key. Clinically, combining Bayesian and frequentist approaches em

The future of risk prediction in surgical oncology, therefore, does not hinge on a choice between frameworks, but on their rational combination. Integrating the rigor of frequentist statistics with the adaptability of Bayesian reasoning will yield predictive tools that are not only statistically sound but also clinically intuitive and actionable. This synergistic approach moves us closer to the ultimate goal of delivering truly individualized predictions to improve patient outcomes. In practice, this combination allows models to leverage prior knowledge for personalization while being rigorously tested against observed data. The result is a more informed clinical decision-making process, where estimated probabilities of outcomes are meaningful to both physicians and patients, effectively growing in a new era of predictive precision in surgical oncology.

| 1. | An Y, Sun YG, Feng S, Wang YS, Chen YY, Jiang J. Constructing a prediction model for delayed wound healing after gastric cancer radical surgery based on three machine learning algorithms. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2025;17:111163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lucas P. Bayesian analysis, pattern analysis, and data mining in health care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004;10:399-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Global BMI Mortality Collaboration, Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju ShN, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Cairns BJ, Huxley R, Jackson ChL, Joshy G, Lewington S, Manson JE, Murphy N, Patel AV, Samet JM, Woodward M, Zheng W, Zhou M, Bansal N, Barricarte A, Carter B, Cerhan JR, Smith GD, Fang X, Franco OH, Green J, Halsey J, Hildebrand JS, Jung KJ, Korda RJ, McLerran DF, Moore SC, O'Keeffe LM, Paige E, Ramond A, Reeves GK, Rolland B, Sacerdote C, Sattar N, Sofianopoulou E, Stevens J, Thun M, Ueshima H, Yang L, Yun YD, Willeit P, Banks E, Beral V, Chen Zh, Gapstur SM, Gunter MJ, Hartge P, Jee SH, Lam TH, Peto R, Potter JD, Willett WC, Thompson SG, Danesh J, Hu FB. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388:776-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1610] [Cited by in RCA: 1862] [Article Influence: 186.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sadighi Akha AA. Aging and the immune system: An overview. J Immunol Methods. 2018;463:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hatton GE, Pedroza C, Kao LS. Bayesian Statistics for Surgical Decision Making. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2021;22:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chu J, Sun NA, Hu W, Chen X, Yi N, Shen Y. The Application of Bayesian Methods in Cancer Prognosis and Prediction. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2022;19:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Percival WJ, Friedrich O, Sellentin E, Heavens A. Matching Bayesian and frequentist coverage probabilities when using an approximate data covariance matrix. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 2022;510:3207-3221. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the ori