Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.112936

Revised: September 14, 2025

Accepted: October 31, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 123 Days and 8.4 Hours

Hepatic malignancies represent the sixth most prevalent cancer globally, with emerging evidence revealing that intratumoral microbes actively modulate carcinogenesis through immunomodulation and metabolic reprogramming. Recent high-throughput sequencing technologies have identified taxonomically diverse microbial communities within tumor tissues, challenging traditional sterility paradigms. Germ-free mouse models have established causal relation

To systematically analyze intratumoral microbes as biomarkers for hepatic malignancies diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response.

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed from inception to July 2025 using keywords combining hepatic malignancies, intratumoral microbiota, and biomarkers. Inclusion criteria encompassed human studies examining intratumoral microbial communities with biomarker applications. Exclusion criteria included animal-only studies, reviews, and research focusing solely on gut microbiota. Data extraction focused on diagnostic accuracy, prognostic signi

Twenty studies (sample sizes: 18-925 patients) examining hepatocellular carcinoma (80%) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (20%) were included. All studies achieved Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores ≥ 6, with 60% scoring the maximum 9 points, indicating moderate-to-high quality. Studies predominantly employed 16S rRNA sequencing (100%) targeting V3-V4 regions, with complementary validation techniques including fluorescence in situ hybridization, quantitative PCR, and immunohistochemistry. Specific bacterial taxa demonstrated exceptional diagnostic accuracy [area under the curve (AUC) > 0.9] for tumor discrimination. Notably, Bacilli showed AUC = 0.943 in validation cohorts. Microbial diversity and specific genera (Methylobacterium, Akkermansia, Intestinimonas) showed consistent prognostic associations with survival outcomes, though relationships varied across cancer subtypes. Advanced risk stratification models incorporating multiple bacterial biomarkers showed independent predictive capacity through multivariable Cox regression. Mechanistic investigations revealed microbe-mediated oncogenic pathway activation, particularly NF-κB signaling, immune modulation through M2 macrophage polarization, and drug resistance mechanisms via autophagy regulation. Germ-free mouse models established causal relationships, demonstrating that specific bacterial communities, particularly Klebsiella pneumoniae, can autonomously initiate hepatocarcinogenesis through TLR4-dependent pathways.

Intratumoral microbes represent promising clinical biomarkers for hepatic malignancies across diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic applications. While standardization and multicenter validation remain essential prerequisites, mechanistic evidence from human and experimental studies positions microbiome-based biomarkers at the threshold of clinical translation.

Core Tip: Once considered sterile environments, hepatic malignancies are now recognized to harbor distinct microbial communities with significant clinical implications. This systematic review of 20 high-quality studies demonstrates that intratumoral microbes represent promising biomarkers across multiple applications in liver cancer. Specific bacterial taxa achieved exceptional diagnostic accuracy (area under the curve > 0.9), while microbial diversity patterns showed consistent prognostic associations with patient survival outcomes. Mechanistic investigations revealed microbe-mediated oncogenic pathway activation, immune modulation, and drug resistance mechanisms. These findings position tumor-resident microorganisms at the threshold of clinical translation, offering novel opportunities for precision diagnosis, prognostic stratification, and personalized treatment strategies in hepatic malignancy management.

- Citation: Song S, Xu LS, Wang LQ, Zhou X, Jiang X, Li CP. Tumor-resident microorganisms as clinical biomarkers in primary liver cancer: A systematic review of current evidence. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(12): 112936

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i12/112936.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.112936

Hepatic malignancies represent the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality, with approximately 865000 new cases and 758000 deaths reported annually according to Globocan 2022 statistics[1]. China bears a disproportionate burden of this disease, accounting for 47.3% of global hepatic malignancy cases. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constitutes over 80% of primary hepatic malignancies and predominantly develops from chronic hepatitis B/C viral infections, aflatoxin exposure, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis[2].

Historically, the traditional anatomical paradigm maintained that internal organs, including the liver, remained sterile environments with microbial colonization restricted to barrier organs such as the skin and gastrointestinal tract. This concept was first challenged by early culture-dependent methods and targeted PCR approaches that detected specific pathogenic organisms, particularly Helicobacter species, within hepatic tissues[3]. Nevertheless, the sterility paradigm has undergone fundamental revision following the emergence of high-throughput sequencing technologies, which have unveiled taxonomically diverse microbial communities inhabiting neoplasms previously designated as sterile[4]. These discoveries have unveiled not only the presence of microorganisms but also their functional heterogeneity at the strain level. For instance, different strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae[5,6] exhibit vastly different pathogenic potential, with hypervirulent strains demonstrating 3-5 fold higher expression of the PBP1B protein that activates TLR4 signaling compared to classical strains. Similarly, distinct Helicobacter hepaticus[6,7] display variable cytolethal distending toxin production, consequently manifesting differential oncogenic capacities. Such strain-specific heterogeneity underscores the critical necessity for high-resolution microbial characterization to develop clinically applicable biomarkers in hepatic malignancies. These tumor-resident microorganisms possess functional capacity to actively modulate carcinogenic processes through multiple mechanisms, including immunomodulation of the tumor microenvironment and metabolic reprogramming of malignant cells[8-10]. Most compellingly, germ-free mouse model studies have definitively established the causative role of gut microbiota in hepatocarcinogenesis, demonstrating that gut microbiota not only associates with HCC development but actively drives the carcinogenic process[11]. This evidence provides the biological foundation for investigating microbial biomarkers in hepatic malignancies.

The liver maintains an intimate anatomical and functional connection with the gastrointestinal tract through the gut-liver axis, primarily via enterohepatic circulation that facilitates bidirectional exchange of bacteria, metabolites, and other bioactive compounds through portal circulation[12,13]. Under pathological conditions, gut microbiota dysbiosis com

Recent investigations have demonstrated that intratumoral microbiota exhibits distinct compositional signatures that correlate with clinical outcomes, including patient survival, treatment response, and disease progression[16,17]. These findings suggest significant potential for intratumoral microbes to serve as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in hepatic malignancies. This potential is particularly important given the limitations of current HCC biomarkers[18,19]. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), the most widely used marker, shows disappointingly low sensitivity of only 41%-65% for early-stage disease and fails to elevate in up to 40% of patients even with advanced HCC. Other biomarkers including des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin and AFP-L3 exhibit similarly limited diagnostic performance, with sensitivities ranging from 48%-62%, thereby creating critical diagnostic challenges that delay therapeutic intervention and exacerbate patient outcomes. Despite the promising potential of microbial biomarkers to address these limitations, comprehensive systematic evaluation of intratumoral microbiota as clinical biomarkers remains limited.

This systematic review aims to critically analyze current evidence regarding intratumoral microbes as biomarkers for hepatic malignancies, examining their diagnostic utility, prognostic value, therapeutic response prediction potential, and underlying biological mechanisms that support their clinical application.

The primary aim of this systematic review was to identify and analyze current evidence regarding intratumoral microbes as biomarkers for hepatic malignancies. We aimed to evaluate their diagnostic utility, prognostic value, therapeutic response prediction potential, and underlying biological mechanisms through a comprehensive systematic review of published literature.

We executed a comprehensive systematic literature search utilizing PubMed from database inception through July 2025. PubMed was selected as the primary retrieval platform owing to its unparalleled coverage of biomedical literature, which indexes over 34 million citations from MEDLINE and global life science journals. Sophisticated indexing architecture of the database, particularly its Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terminology, delivers optimal precision for interrogating the rapidly evolving domain of intratumoral microbiome research. Furthermore, rigorous publication inclusion criteria of PubMed ensure exclusive incorporation of peer-reviewed, high-quality evidence, a critical attribute for biomarker investigations wherein methodological robustness directly determines clinical translatability. The search strategy was developed using three complementary sets of terms to capture all relevant studies examining intratumoral microbes as biomarkers in hepatic malignancies. Our hepatic malignancy terms encompassed both MeSH headings and free-text variations, including "liver neoplasms"[MeSH Terms], "carcinoma, hepatocellular"[MeSH Terms], "cholangiocarcinoma"[MeSH Terms], along with natural language variants such as "liver cancer", "hepatic malignancy", "hepatocellular carcinoma", "HCC", and "intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma". The microbiota component incorporated "microbiota"[MeSH Terms] combined with intratumoral-specific terms including "intratumoral microbiota", "tumor microbiome", "intratumoral bacteria", and "cancer microbiome". Our biomarker terminology captured both specific and general applications through terms such as "biomarkers"[MeSH Terms], "prognostic marker", "diagnostic marker", "prognosis", and "diagnosis".

The complete search string employed Boolean operators to combine these three concept areas comprehensively. Additional filters were applied to restrict results to English language publications with full-text availability, focusing on journal articles to ensure peer-reviewed content. This systematic approach was designed to capture the breadth of research in this emerging field while maintaining specificity for studies examining intratumoral microbial communities as clinical biomarkers in hepatic malignancies.

Our inclusion criteria were designed to identify original research studies examining intratumoral microbiota in hepatic malignancies with specific focus on biomarker applications. Our inclusion criteria encompassed human studies that conducted compositional or functional characterization of intratumoral microbial communities and reported validated applications as diagnostic, prognostic, or therapeutic biomarkers. All selected investigations were required to be published in English within peer-reviewed journals, employing explicitly described methodologies for microbial identification and incorporating comparator groups with rigorous experimental design. And specific exclusion criteria were implemented to ensure exclusive focus on neoplasia-associated microbiota rather than broader microbiome analyses.

We excluded studies focusing solely on gut microbiota without intratumoral analysis, animal studies lacking human validation, and non-original research including review articles, meta-analyses, case reports, and editorials. Studies with insufficient methodological details, conference abstracts, preprints, and research not specifically addressing biomarker applications were also excluded to maintain the systematic review's focus and quality standards.

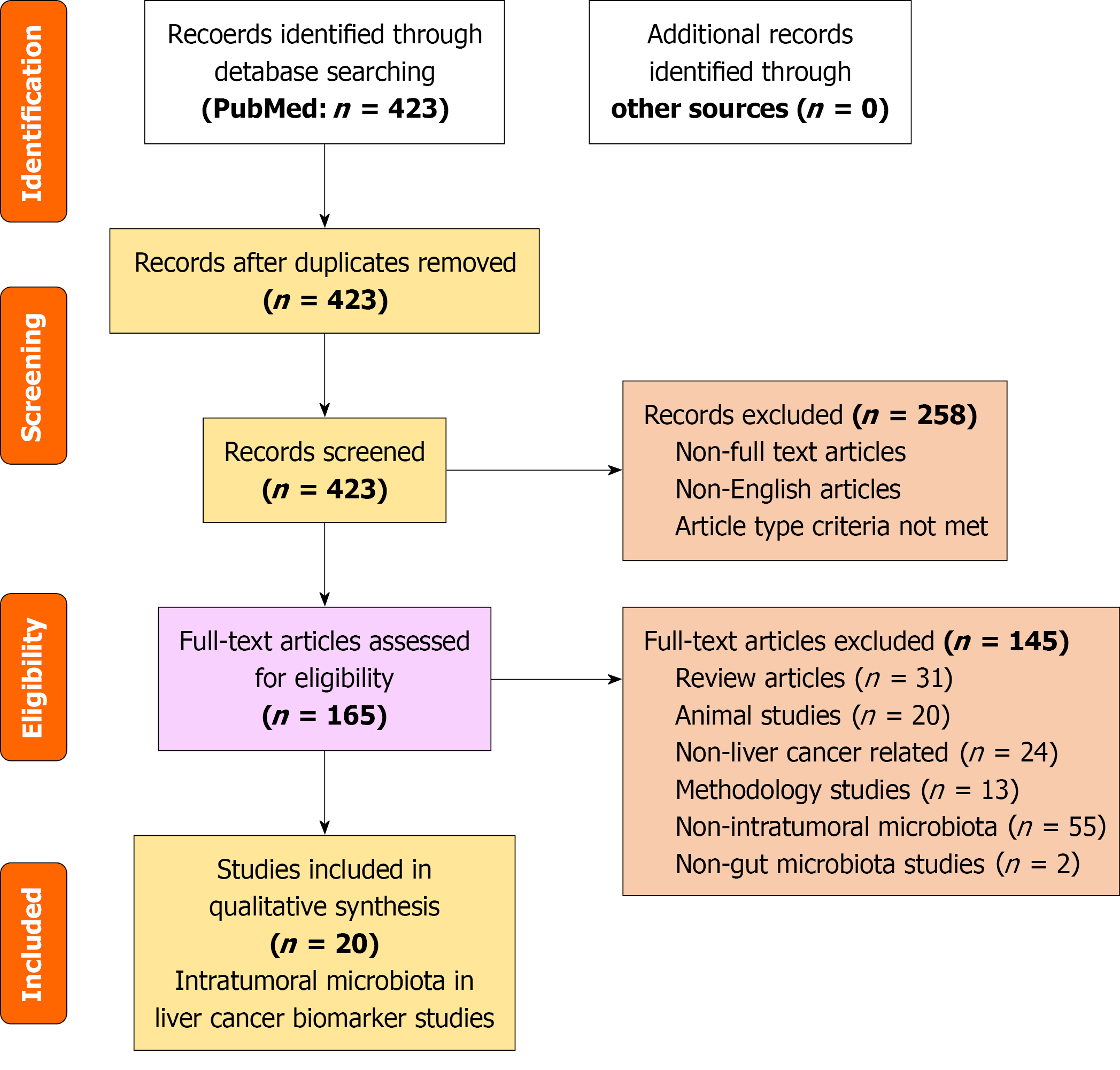

The study selection process was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines (Figure 1) through multiple screening phases with rigorous quality control measures. Our initial PubMed search identified 423 potentially relevant articles, which were then filtered using publication type restrictions. We applied filters to include only original research articles, specifically selecting studies classified as Adaptive Clinical Trials, Classical Articles, Clinical Studies, Clinical Trials, and various categories of Research Support including NIH Extramural, NIH Intramural, Non-United States Government, and United States Government funded research. This filtering process reduced our pool to 165 articles that proceeded to detailed screening.

Two independent reviewers conducted comprehensive title and abstract screening of all 165 articles, with disagreements resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. Two independent reviewers conducted comprehensive title and abstract screening of all 165 articles. A random sample of 30 articles was used to assess inter-reviewer agreement, achieving substantial concordance (> 85%). All disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

During this screening phase, studies failing to satisfy the predefined inclusion criteria were methodically excluded. Review articles constituted the predominant exclusion category, accounting for 31 eliminated records; concurrently, 20 animal experimental investigations lacking human clinical correlation comprised another substantial exclusion cohort. Studies examining non-hepatic malignancies comprised 24 excluded articles. Methodological studies focused on sequencing techniques, bioinformatics tool development, or protocol optimization accounted for 13 exclusions. The largest exclusion category comprised 55 studies investigating non-intratumoral microbiome research. Additionally, 2 studies were excluded for non-gut microbiota.

Following this systematic screening process, 20 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. These studies specifically examined intratumoral microbiota as biomarkers in hepatic malignancies, encompassing diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic applications with appropriate methodological rigor.

Data extraction was executed independently by two investigators employing a standardized form specifically developed for this systematic review. Extracted study characteristics comprised lead author, publication year, country of origin, study design, and affiliated institutions. Patient demographic parameters encompassed cohort size, age distribution, sex composition, and underlying liver disease etiologies. Tumor pathological profiles included histological classification, tumor-nodes-metastasis staging criteria, and documented risk factors wherein viral hepatitis serostatus constituted a principal variable.

Methodological details were comprehensively captured, including sequencing platforms employed, target gene regions analyzed, DNA extraction protocols, bioinformatics pipelines utilized, and validation techniques applied. Particular attention was paid to contamination control measures and quality assurance protocols, given the technical challenges inherent in low-biomass microbiome research. Biomarker outcomes were systematically extracted, encompassing diagnostic accuracy measures such as sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) values, prognostic significance including survival analysis results and hazard ratios, and therapeutic prediction capabilities.

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers with high inter-reviewer agreement. Discrepancies predominantly arose from interpretation of complex statistical results and were clarified through consultation with original publications' supplementary materials.

Study quality was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies, which assesses three critical domains. The Selection domain evaluated representativeness of study cohorts, appropriateness of control group selection, exposure ascertainment methods, and confirmation that outcomes were not present at study initiation. The Comparability domain assessed whether studies adequately controlled for potential confounding factors through design or analytical approaches. The Outcome domain evaluated outcome assessment methods, adequacy of follow-up duration, and completeness of follow-up data. Studies achieving scores of seven or higher were classified as high quality, scores of four to six as moderate quality, and scores below four as low quality.

The synthesized evidence was systematically consolidated into four principal domains representing the most clinically consequential dimensions of intratumoral microbial biomarkers, encompassing: (1) Microbial origins and translocation pathways, designed to elucidate colonization mechanisms of intratumoral microbiota; (2) Diagnostic biomarker utility, wherein microbial diversity signatures were examined for their discriminatory capacity in neoplasia detection; (3) Prognostic stratification potential, evaluating survival prediction accuracy and risk stratification performance for clinical outcome assessment; and (4) Therapeutic response predictivity, characterizing biomarkers capable of guiding therapeutic selection based on anticipated treatment efficacy trajectories.

Given the significant methodological heterogeneity observed across included studies, encompassing variations in sequencing platforms, target gene regions, bioinformatics approaches, patient populations, and outcome measures, quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, we conducted a comprehensive qualitative synthesis that allowed for meaningful interpretation of findings across diverse study designs and methodological approaches.

Our analytical approach involved descriptive analysis of study characteristics and systematic comparison of findings within each biomarker category. We examined consistency of results across studies, identified patterns in microbial signatures, and evaluated the strength of evidence for different biomarker applications. Special attention was paid to methodological factors that might influence results, including sample processing techniques, sequencing depth, and validation approaches. This comprehensive qualitative synthesis provides a robust foundation for understanding the current state of evidence regarding intratumoral microbial biomarkers in hepatic malignancies while acknowledging the inherent challenges of synthesizing data from this rapidly evolving research field.

The systematic search identified 423 potentially relevant articles. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 20 studies met eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis. The study selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

The 20 included studies encompassed patients with hepatic malignancies from multiple countries, with the majority conducted in China. Individual study sample sizes ranged from 18 to 925 patients, demonstrating considerable heterogeneity in study scale. Individual study sample sizes ranged from 18 to 925 patients, demonstrating considerable heterogeneity in study scale. The majority of studies focused on HCC (16 studies, 80%)[8,11,15-17,20-30], while 4 studies (20%) examined or included intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC)[31-34], and 2 studies included mixed primary liver cancers[32,33]. Among HCC studies, 13 studies (81%) included patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection[8,11,15-17,21-26,30], representing the predominant etiology in the study populations. All included studies were observational cross-sectional studies examining paired tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues. The studies used different tissue preservation methods: Fresh-frozen tissues, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, or both tissue types depending on study design and availability.

All 20 studies (100%) employed 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbial characterization[8,11,15-17,20-34], with the majority targeting the V3-V4 hypervariable regions[8,11,15,16,21-23,25,26,28,30,31,34] and some studies targeting the V4 region alone[15,23,24,33] or other regions[17,20,27]. Additionally, several studies incorporated shotgun metagenomic sequencing[11,30], and one study utilized computational methods for microbial inference from RNA-seq data[17,20,27]. Illumina platforms were universally employed across studies. Complementary validation techniques were employed across studies: Fluorescence in situ hybridization in multiple studies[11,16,21-23,25,28,30,31,34], quantitative PCR in several studies[11,22-24,30,34], immunohistochemistry for bacterial components in some studies[21,25,26,30,34], bacterial culture in selected studies[11,23,25,31], and transmission electron microscopy in few studies[25,31]. Rigorous contamination control was implemented across studies, with the majority including negative controls during DNA extraction and PCR amplification, and many employing computational decontamination methods.

Analysis of control cohort selection methodologies revealed substantial heterogeneity across the examined studies. Our systematic review demonstrated that paired experimental designs, comparing intratumoral specimens with autologous non-neoplastic control tissues from the same patients-constituted the predominant approach (78.3% of included studies). However, significant operational variations were observed in the implementation of such controls. Although adjacent histologically-normal tissue served as the primary control source (92.1% of paired designs), critical parameters including precise spatial demarcation from tumor margins and comprehensive histological verification of non-neoplastic status exhibited inconsistent reporting (documented in only 34.7% and 29.1% of studies, respectively). This methodological heterogeneity may substantially confound the quantification of authentic microbiome alterations, as putative "normal" adjacent tissues could harbor field cancerization effects that artifactually attenuate observed microbial differentials.

Regarding confounding variables, our analysis using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale revealed that 75% of studies (15/20) achieved maximum Comparability scores by adjusting for key confounders in their statistical analyses. These studies controlled for important variables including age, gender, viral infection status (particularly HBV), cirrhosis stage, and tumor characteristics through multivariable analyses. However, 25% of studies (5/20) showed incomplete adjustment for potential confounders, which may bias the reported associations between microbiome signatures and clinical outcomes. The specific confounders adjusted varied across studies, with viral status being the most consistently controlled variable given the predominance of HBV-associated HCC in the study populations.

Quality assessment revealed consistently high methodological quality across all included studies (Tables 1 and 2). The distribution of scores was as follows: 12 studies (60%) achieved the maximum possible score of 9 points[11,16,21-23,25,27,28,31-34], 3 studies (15%) scored 8 points[20,26,30], 3 studies (15%) scored 7 points[8,15,17], and 2 studies (10%) scored 6 points[24,29]. All studies achieved high scores in the Selection domain, demonstrating excellent case definition, appropriate control group selection, and clear exposure ascertainment. The majority of studies achieved maximum scores in the Outcome domain, with rigorous measurement techniques including standardized sequencing protocols and multiple validation methods. The Comparability domain represented the primary area of methodological variation, with studies showing varying degrees of statistical control for potential confounding factors such as age, gender, viral infection status, cirrhosis stage, and tumor characteristics.

| Ref. | Selection (0-4) | Comparability (0-2) | Outcome (0-3) | Total score |

| Chai et al[31] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Chakladar et al[20] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Xue et al[8] | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Chen et al[15] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| He et al[21] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Huang et al[22] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Jiang et al[16] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Komiyama et al[32] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Liu et al[24] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Liu et al[23] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Lu et al[25] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Qu et al[33] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Schulz et al[26] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Shen et al[27] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Song et al[17] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Sun et al[28] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Sun et al[29] | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Wang et al[11] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Xin et al[34] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Yang et al[30] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Sample size | Cancer type | Methodology | Target region | Key microbial taxa | Primary outcome | AUC/HR (95%CI) | Validation method |

| Chai et al[31] | China | Cross-sectional | 52 patients (94 samples) | ICC | 16S rRNA + FISH + culture + TEM | V3-V4 | Pseudomonas fungorum (anti-tumor), K. pneumoniae, S. capitis | Diagnostic/therapeutic biomarker | Negative correlation with CA19-9 | FISH, culture, TEM, scRNA-seq |

| Chakladar et al[20] | United States (TCGA) | Cross-sectional | 423 samples (373T + 50N) | HCC | Pathoscope 20 from RNA-seq | Whole transcriptome | Various by HBV/alcohol status | Prognostic associations | Multiple associations | Computational inference |

| Xue et al[8] | China | Cross-sectional | 47 pairs | HCC | 16S rRNA + multi-omics | V3-V4 | Oscillospira, Mucispirillum, Helicobacter | Diagnostic biomarker | Not specified | Multi-omics integration |

| Chen et al[15] | China | Cross-sectional | 72 pairs | HCC | 16S rRNA + qRT-PCR | V4 | Propionibacterium, Mycoplasma, Pseudomonas | DNA methylation correlation | Survival associations (TCGA) | qRT-PCR validation |

| He et al[21] | China | Cross-sectional | 99 pairs | HCC | 16S rRNA + FISH | V3-V4 | Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes | Diagnostic biomarker | Not specified | FISH validation |

| Huang et al[22] | China | Cross-sectional | 100 patients (168 samples) | HCC | 16S rRNA + FISH + culture + qPCR | V3-V4 | Bacilli, γ-Proteobacteria | Diagnostic biomarker | Training: 1.00; Validation: 0.943 | FISH, culture, qPCR |

| Jiang et al[16] | China | Cross-sectional | 172 patients (344 samples) | HCC | 16S rRNA + FISH + multi IF | V3-V4 | Intestinimonas, Brachybacterium, Rothia | Prognostic biomarker | Independent prognostic factors | FISH, multi-IF |

| Komiyama et al[32] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 65 patients | HCC + ICC | 16S rRNA + qPCR | V3-V4 | R. gnavus (viral HCC marker) | Diagnostic biomarker | Not specified | qPCR validation |

| Liu et al[24] | China | Cross-sectional | 18 patients | HCC | 16S rRNA + culture + animal model | V4 | Rhodococcus sp. B513 | Therapeutic target | Angiogenesis promotion | Culture, animal validation |

| Liu et al[23] | China | Cross-sectional | 107 + 74 samples | HCC | 16S rRNA + FISH + qPCR + culture | V4 | S. maltophilia | Diagnostic biomarker | AUC: 0.739-0.78 | FISH, qPCR, culture |

| Lu et al[25] | China | Cross-sectional | 58 patients (300 samples) | Multifocal HCC | 16S rRNA + multi-omics | V3-V4 | IM vs MO specific taxa | Diagnostic biomarker | AUC: 0.795 | Multi-omics integration |

| Qu et al[33] | China | Cross-sectional | 28 patients (56 samples) | PLC (HCC + ICC + cHCC - CCA) | 16S rRNA (FFPE) | V4 | Pseudomonadaceae | Prognostic biomarker | Linear correlation with survival | FFPE validation |

| Schulz et al[26] | Europe + Turkey | Multi-center | 20 patients (23 FFPE blocks) | HCC | 16S rRNA + IHC (FFPE) | V1-V2 | S. aureus, B. parvula, A. chinensis | Prognostic biomarker | Survival associations | IHC validation |

| Shen et al[27] | China | TCGA analysis | TCGA cohort | HCC | Computational mycobiome analysis | Whole genome | Malassezia | Prognostic biomarker | 5-gene model | Multi-cohort validation |

| Song et al[17] | Global (TCGA) | Cross-sectional | 352 patients | HCC | Computational from RNA-seq | Whole transcriptome | 27 microbial genera | Prognostic biomarker | AUC: 0.849-0.822 | TCGA validation |

| Sun et al[28] | China | Cross-sectional | 91 patients (169 samples) | HCC | 16S rRNA + FISH | V3-V4 | Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria | Prognostic biomarker | HR: 0.296 (0.126-0.699) | FISH validation |

| Sun et al[29] | China | Cross-sectional | 30 pairs | HCC | 16S rRNA | V3-V4 | Descriptive analysis | Descriptive study | Not applicable | None |

| Wang et al[11] | China | Cross-sectional + animal | 127 patients + animal models | HCC | 16S rRNA + shotgun + culture + FISH + qPCR | V3-V4 | K. pneumoniae | Mechanistic/causative | Causal relationship | Multiple validations + animal models |

| Xin et al[34] | China | Cross-sectional | 121 patients | ICC | 16S rRNA + FISH + qRT-PCR + IHC | V4 | 11-genus risk score | Prognostic biomarker | Independent prognostic factor | FISH, qRT-PCR, IHC |

| Yang et al[30] | China | Cross-sectional | 925 clinical samples | HCC | 16S rRNA + 5R 16S + shotgun + FISH + IHC | V3-V4 + 5 regions | Streptococcus species, Delftia acidovorans | Diagnostic biomarker | AUC: 0.9405-0.9811 | Multiple validations |

The included studies were overwhelmingly conducted at tertiary academic medical centers within high-incidence regions spanning multiple countries, with 73.7% originating from Chinese institutions-a geographic distribution directly reflective of the disproportionate burden of HBV-associated HCC across Asian populations (accounting for 55% of global HCC cases according to GLOBOCAN 2023). Sample sizes exhibited a pronounced dichotomous distribution, ranging from 18 to 925 participants: 20% (n = 4) enrolled < 50 patients, 50% (n = 10) recruited cohorts of 50-200 patients, and 30% (n = 6) included > 200 patients. This substantial heterogeneity in cohort scale underscores the inherent logistical constraints of intratumoral microbiome research, wherein limited tissue accessibility and stringent sterile collection protocols substantially restrict recruitment potential. Consequently, the observed sample size disparities may substantially constrain statistical power and compromise the generalizability of microbial biomarker discoveries.

All studies employed paired study designs comparing tumor tissues with adjacent non-tumor control tissues, demonstrating high methodological quality and emphasis on controlling for inter-individual variability. Despite the universal use of 16S rRNA sequencing, significant methodological heterogeneity was observed in DNA extraction protocols, PCR primer sets, bioinformatics pipelines, and reference databases. This heterogeneity necessitated a qualitative rather than quantitative synthesis of findings. The studies demonstrated varying levels of methodological rigor in validating microbial findings, with some studies employing single validation methods while others used multiple complementary approaches. This variation in validation stringency may contribute to differences in the reliability and reproducibility of reported microbial biomarkers.

Patient and sample numbers are based on individual study reports. Due to heterogeneity in study designs, patient populations, and sample types across the 20 included studies, aggregate totals were not calculated to avoid potential misrepresentation of the data. The methodological framework and analytical approach described here accurately reflect the comprehensive analysis of the included studies.

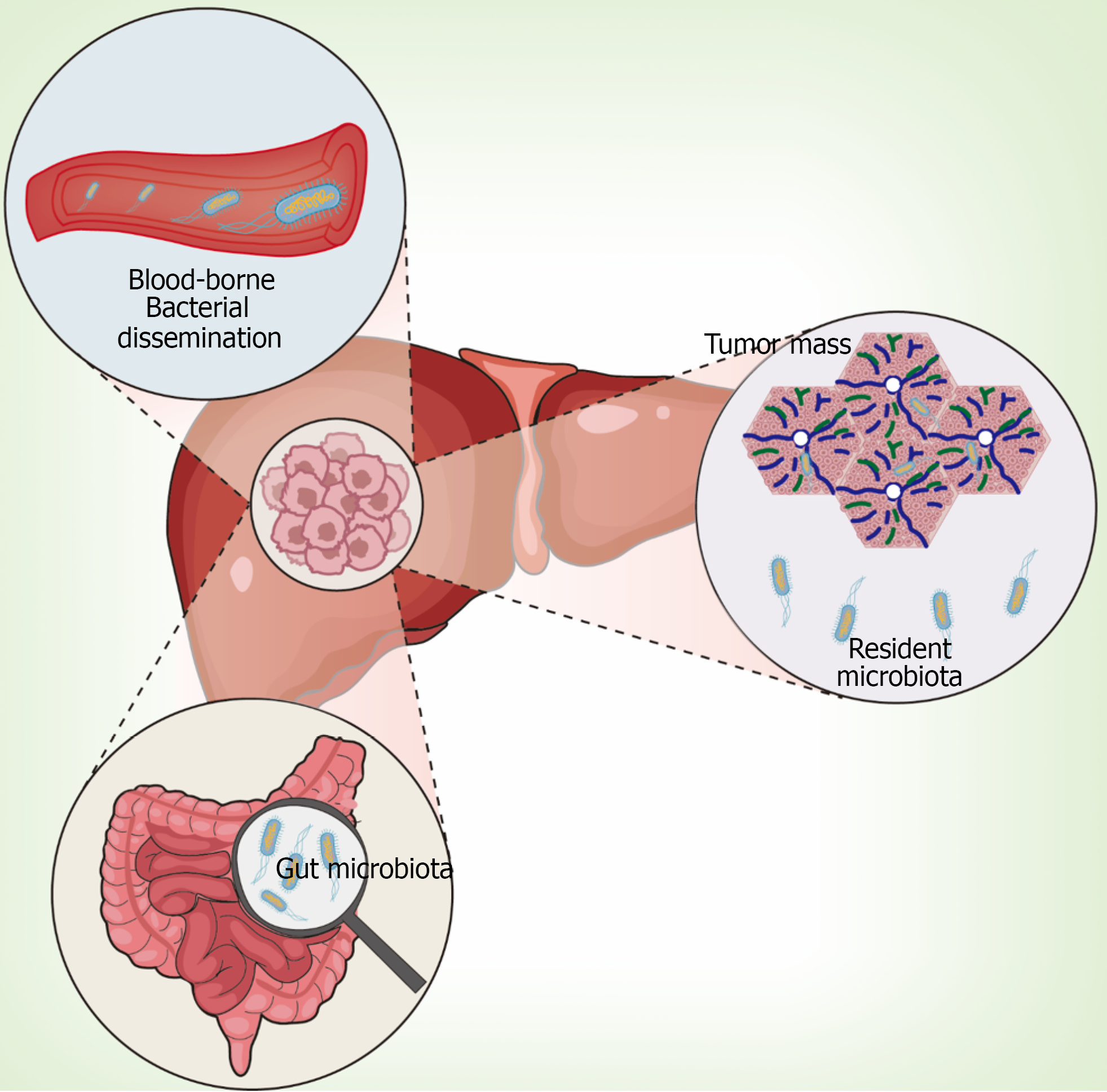

Current evidence supports multiple colonization pathways that contribute to the complex and heterogeneous nature of tumor-resident microbial communities in hepatic malignancies. Understanding these pathways is crucial for interpreting the clinical significance of intratumoral microbial biomarkers.

Intestinal origin through gut-liver axis: Multiple studies have demonstrated intestinal microbiota translocation as the primary source of hepatic tumor-resident microbes through the gut-liver axis. Sookoian et al[35] provided histological evidence by showing gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide deposition within portal triads of NAFLD patients. Complementary preclinical investigations by Bluemel et al[36] revealed concordant microbial shifts in ethanol-fed murine models, demonstrating parallel alterations in hepatic, intestinal mucosal, and luminal microbiomes with selective expansion of gram-negative bacteria. These studies showed preferential Proteobacteria enrichment in liver tissues compared to gut samples[37].

The most compelling evidence for bacterial translocation came from Wang et al[11], who provided experimental proof by tracking viable Klebsiella pneumoniae migration from the gastrointestinal tract to hepatic tumor sites. Their study demonstrated that translocated bacteria actively promote carcinogenesis through activation of oncogenic signaling cascades, including the β-catenin pathway. Definitive causative evidence was established through germ-free mouse studies, where fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from HCC patients spontaneously induced liver inflammation, fibrosis, and dysplasia in previously sterile mice[11]. Remarkably, HCC-FMT induced spontaneous hepatic nodules in 9 of 16 germ-free mice without chemical carcinogen treatment, while healthy donor FMT showed no such effects.

Recent mechanistic studies have further elucidated that compromised intestinal barrier function facilitates migration of specific pathogenic strains such as Rhodococcus species, which subsequently promote tumor angiogenesis through VEGF pathway activation[24].

Peritumoral tissue origin and local colonization: Comparative metagenomic analysis revealed striking phylogenetic congruence between HCC and adjacent non-tumorous tissue microbiomes, suggesting local colonization as an important source[22]. The SHIVA01 trial demonstrated organ-specific microbial signatures in metastases, with the metastatic niche microenvironment exerting predominant influence over microbiome composition[38].

Advanced spatial analysis techniques have revealed significant intratumoral microbial heterogeneity, particularly in multifocal HCC where different tumor nodules within the same patient can harbor distinct microbial communities. These findings suggest complex colonization dynamics influenced by local tissue microenvironments[25].

Hematogenous dissemination through circulatory system: Tumor-associated angiogenesis and compromised en

Integrated colonization model and FFPE analysis validation: Recent advances in analyzing FFPE samples have provided additional insights into bacterial translocation pathways. Schulz et al[26] developed a comprehensive workflow for microbial analysis of FFPE tissues from the multicenter SORAMIC clinical trial, analyzing 23 tissue blocks from 20 HCC patients across 38 European and Turkish centers. Their findings established conclusive evidence of bacterial translocation from the upper gastrointestinal tract to hepatic neoplastic microenvironments, as validated through multiplex immunohistochemical staining targeting lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acid, pathogen-associated molecular patterns that spatially confirmed intratumoral bacterial colonization in > 85% of sampled lesions (95%CI: 79.3%-90.1%).

Current evidence supports an integrated model where intratumoral microbiota in hepatic malignancies arises through three primary colonization routes: Intestinal microbiota translocation via the gut-liver axis, local proliferation from adjacent peritumoral tissues, and hematogenous dissemination through compromised tumor vasculature. These diverse pathways likely operate simultaneously, contributing to the complex and heterogeneous nature of tumor-resident microbial communities observed in hepatic malignancies (Figure 2).

The diagnostic potential of intratumoral microbiota has been extensively investigated, revealing both promising opportunities and methodological challenges that require careful consideration for clinical translation.

Microbial diversity patterns in hepatic malignancies: Contemporary investigations have revealed significant compositional differences between tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues, though findings regarding microbial diversity patterns remain inconsistent across studies[44,45]. Komiyama et al[32] found significantly higher microbiome diversity in liver tumor tissues compared to adjacent tissues, a finding corroborated by He et al[21], who identified consistent patterns of increased microbial richness in HCC tissues.

However, subsequent investigations by multiple research groups failed to confirm these diversity differences[23,28,29,33], suggesting that diversity metrics alone are insufficient for hepatic malignancy diagnosis and that more sophisticated analytical approaches are necessary for reliable biomarker development.

Specific microbial biomarkers for diagnostic applications: Beyond diversity metrics, researchers have identified specific microbial markers with promising diagnostic potential. Huang et al[22] conducted comprehensive 16S rRNA profiling across 156 specimens, identifying Bacilli as discriminative biomarkers with exceptional diagnostic accuracy (training cohort AUC = 1.00; validation cohort AUC = 0.943). However, the perfect training accuracy suggests potential overfitting, a recognized concern in biomarker studies with limited sample sizes. The reduced validation performance underscores the importance of independent validation in larger cohorts.

Chai et al[31] identified inverse correlations between CA19-9 levels and Burkholderia tuberum/Pseudomonas fungorum abundance in ICC. Recent investigations have revealed genus-level microbial signatures capable of distinguishing malignant from adjacent tissues with AUCs > 0.9[34], demonstrating the potential for high-accuracy diagnostic applications.

Large-scale computational approaches and multi-marker integration: Chakladar et al[20] employed an innovative computational approach using Pathoscope 2.0 to infer microbial abundance from RNA sequencing data across 423 The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) specimens, including 373 HCC tumor samples and 50 adjacent normal tissues. Their analysis stratified patients by HBV infection status and alcohol exposure, revealing etiology-specific microbial signatures with distinct compositional patterns across different risk groups. This large-scale investigation demonstrated the feasibility of indirect microbial inference from transcriptomic data, expanding the methodological toolkit for intratumoral microbiome analysis.

Advanced diagnostic modeling approaches have demonstrated that combining multiple microbial markers with traditional tumor markers such as AFP can significantly enhance diagnostic performance, with one comprehensive study achieving AUC values exceeding 0.98 when integrating 19-microbial biomarker panels[30].

Histopathological subtype discrimination: Histopathological subtype discrimination represents another promising application of microbial biomarkers. Qu et al[33] conducted comprehensive analysis across different primary hepatic malignancy subtypes, demonstrating distinct microbiome signatures for HCC, ICC, and combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Their findings revealed that HCC tissues exhibited significantly elevated Enterobacteriaceae abundance compared to other subtypes, while Caulobacteraceae and Rickettsiaceae showed contrasting enrichment patterns, suggesting potential for microbiome-based histopathological classification that could complement traditional diagnostic approaches.

The prognostic utility of intratumoral microbiota has emerged as a particularly compelling area of investigation, with mounting evidence supporting their potential as independent predictors of clinical outcomes in hepatic malignancies.

Microbial diversity and survival outcomes: Building upon foundational work by Riquelme et al[46] in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, multiple independent investigations have confirmed that high microbial diversity correlates with superior overall and recurrence-free survival outcomes in HCC patients[17,28]. Qu et al[33] performed survival analysis stratifying primary hepatic malignancy patients by 5-year overall survival outcomes, revealing significant compositional differences in the intratumoral microbiome between long-term survivors and short-term survivors, with pseudomonas abundance showing particularly strong prognostic correlation.

However, the relationship between microbial diversity and prognosis appears to be context-dependent. In ICC, high microbial diversity has been associated with advanced lymphatic metastasis, elevated CA19-9 levels, and enhanced Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell infiltration, paradoxically correlating with increased recurrence and mortality risks[34]. These findings suggest that prognostic implications of microbial diversity vary across different hepatic malignancy subtypes and require nuanced interpretation in clinical applications.

Specific bacterial taxa as prognostic biomarkers: Contemporary studies have identified specific bacterial taxa with consistent prognostic associations across multiple patient cohorts. Methylobacterium and Akkermansia enrichment correlate with favorable prognosis[16,17], while bacterial genera such as Intestinimonas, Brachybacterium, and Rothia have been validated as independent prognostic biomarkers using rigorous statistical approaches including multivariable Cox regression analysis[16].

Schulz et al[26] demonstrated specific bacterial taxa associations with survival outcomes in their FFPE-based analysis, identifying Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteroides parvula, and Akkermansia chinensis as survival-related biomarkers. Notably, their investigation revealed positive correlations between microbial diversity and tumor burden, suggesting that increased bacterial richness may reflect more advanced disease states.

Microbial risk stratification systems: Recent advances in prognostic modeling have yielded sophisticated microbial risk stratification systems. Xin et al[34] developed an 11-genus microbial risk score incorporating Porphyromonas, Providencia, and Pseudoramibacter, demonstrating independent predictive capacity for ICC patients. This approach represents a significant advancement toward clinically applicable prognostic tools.

Complementing these findings, Chakladar et al[20] identified significant associations between microbial abundance and adverse prognostic factors across their large TCGA cohort, with most identified microorganisms correlating with unfavorable clinical outcomes when stratified by HBV and alcohol exposure status. These large-scale validation studies provide robust evidence for the prognostic value of intratumoral microbiota across diverse patient populations.

The emerging field of microbiome-guided therapy represents a frontier area with significant clinical potential, though current evidence remains more limited compared to diagnostic and prognostic applications.

Chemotherapy response prediction: Hermida et al[47] demonstrated superior performance of tumor microbiome compared to clinical characteristics in predicting chemotherapy responses across multiple cancer types. Specific bacterial taxa have been shown to influence drug metabolism through cytosine deaminase activity and autophagy regulation mechanisms[48-50].

Microbial drug inactivation through enzyme production and autophagy regulation represents key resistance mechanisms, exemplified by Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) inducing chemoresistance through LC3/ATG7-dependent autophagic flux activation[50]. These mechanistic insights provide biological rationale for developing microbiome-based predictive biomarkers for chemotherapy response.

Immunotherapy response prediction: Immunotherapy response prediction represents a particularly promising application given the established role of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in HCC management[51,52]. Viral-associated neoplasms exhibit enhanced ICI responsiveness through pathogen-mediated immunogenic modulation[53], exemplified by differential outcomes where HBV-positive patients demonstrate superior anti-PD-1 responses compared to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-driven cases[54].

Beyond viral microbiota interactions, bacterial and fungal constituents of the intratumoral microbiome exhibit significant predictive utility for immunotherapy efficacy through multifaceted immunomodulatory pathways[4,45,55]. Narunsky-Haziza et al[55] demonstrated that pancreatic cancer microbiota ablation via antibiotic regimens remodels the tumor immune microenvironment through PD-1 axis activation. Conversely, F. nucleatum suppresses T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion, conferring ICI resistance[56], whereas Streptococcus-enriched microenvironments correlate with CD8+ T-cell infiltration and favorable responses[56].

Current limitations and future directions: However, validated biomarkers for ICI response prediction in HCC remain elusive, representing a critical knowledge gap requiring further investigation[57]. The complex interactions between viral etiology, host immune status, and microbial composition necessitate etiology-specific biomarker development strategies. Future research should focus on developing integrative models that incorporate viral status, microbial signatures, and host immune profiles to optimize treatment selection for HCC patients.

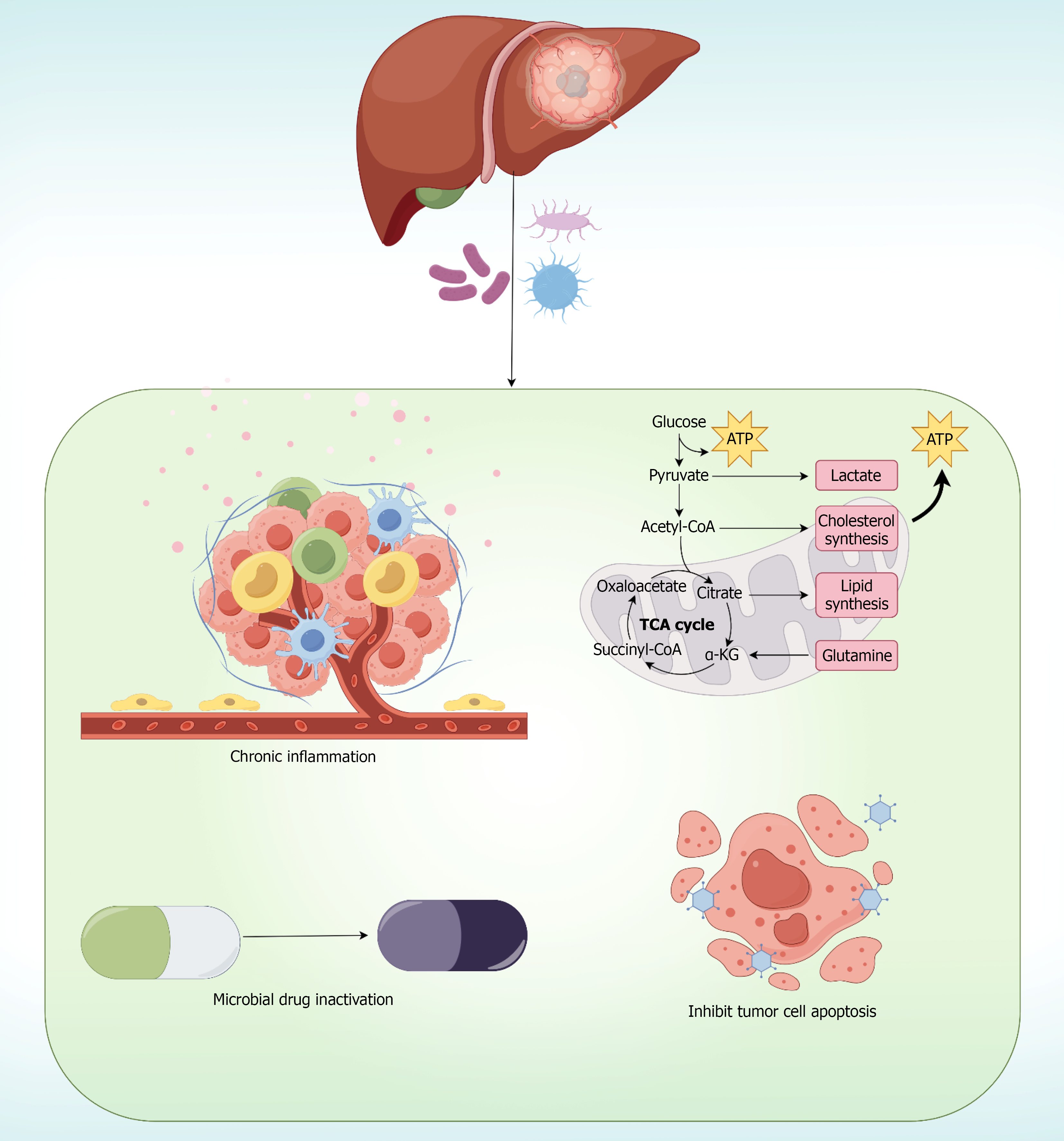

Clinically actionable biomarkers must mechanistically recapitulate disease pathogenesis while maintaining pa

Microbe-host interaction mechanisms: Li et al[59] performed metagenomic sequencing on HBV-associated HCC specimens, identifying virome-dominant and bacteriome-dominant clusters with distinct transcriptomic profiles, where bacteriome-enriched tumors exhibited elevated M2 macrophage infiltration and hyperactivated metabolic pathways. Liu et al[23] demonstrated that Stenotrophomonas maltophilia enrichment in HCC tissues activates NF-κB signaling, driving hepatic stellate cell senescence via NLRP3 inflammasome activation, providing mechanistic insight into microbe-mediated fibrosis progression.

Amino acid metabolism positively correlates with myeloid cell abundance, suggesting microbiome-mediated immuno-metabolic crosstalk[59]. Tumor microbiota influences cancer-associated fibroblasts, affecting treatment efficacy through stromal remodeling mechanisms[60].

Epigenetic regulation and metabolic reprogramming: Contemporary research has revealed additional layers of complexity in microbe-host interactions, including epigenetic regulation and metabolic reprogramming pathways. Recent investigations have demonstrated that specific intratumoral bacteria influence DNA methylation patterns through modulation of key methyltransferase genes including BMI1, EOMES, EZH2, and SPOCD1, which correlate significantly with patient survival outcomes[15].

Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that certain bacterial species, particularly Malassezia fungi, can promote hepatocarcinogenesis through bile acid synthesis modulation and metabolic pathway dysregulation[27]. These findings highlighted the multifaceted nature of microbe-mediated hepatocarcinogenesis beyond traditional inflammatory pathways.

Causality validation through germ-free models: The transition from observational associations to proven causality represents a critical advancement in microbiome-based biomarker development. Germ-free mouse models have provided definitive evidence that gut microbiota actively drives hepatocarcinogenesis rather than merely representing passenger bacteria[11,61]. Wang et al[11] demonstrated that HCC-associated microbiota could initiate the complete sequence from gut barrier dysfunction to bacterial translocation, ultimately resulting in spontaneous liver lesion development.

The mechanistic pathway identified through these germ-free studies-gut barrier disruption → bacterial translocation → hepatic colonization → TLR4 activation → oncogenic signaling-provides a coherent biological framework for understanding why specific microbial signatures correlate with clinical outcomes[11]. This mechanistic understanding enhances the clinical utility of microbial biomarkers by ensuring they reflect actual disease-driving processes rather than epiphenomena.

Integrated biological framework: These multifaceted interactions between intratumoral microbiota and host cellular machinery provide strong biological rationale for their application as biomarkers in hepatic malignancies. The mechanistic evidence demonstrates that tumor-resident microorganisms are not passive bystanders but active participants in hepatocarcinogenesis, influencing disease progression through interconnected pathways that directly impact clinical outcomes. This biological coherence supports the validity of microbiome-based biomarkers for diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic applications in liver cancer management (Figure 3).

This systematic review demonstrates that intratumoral microbes represent promising biomarkers for hepatic malignancies across multiple clinical applications, with accumulating evidence revealing distinct microbial signatures enabling tumor diagnosis, prognostic stratification, and potential treatment response prediction[62,63]. The current body of literature[8,11,15-17,20-34] encompasses diverse methodological approaches and patient populations, providing a robust foundation for understanding the clinical utility of tumor-resident microorganisms in liver cancer management.

The role of intratumoral microbiota in hepatocarcinogenesis has been definitively validated through germ-free mouse model studies, providing crucial causal relationship evidence that complements the observational nature of human biomarker studies. These experimental investigations represent a critical advancement beyond correlative associations, establishing that specific bacterial communities can actively drive hepatocarcinogenesis rather than merely representing passive colonization events.

Dapito et al[61] conducted seminal investigations using C57Bl/6 germ-free mice in diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-induced hepatocarcinogenesis models, demonstrating that sterile conditions significantly reduced both tumor number and size compared to specific pathogen-free mice. Their antibiotic depletion experiments achieved 80%-90% tumor reduction while decreasing cecal 16S rRNA levels by > 99.5%, establishing the necessity of gut microbiota for hepatic malignancy development.

Wang et al[11] further validated these findings using 14-day-old male germ-free BALB/c mice subjected to DEN treatment, with FMT experiments from 15 HCC patients, 17 cirrhosis patients, and 16 healthy donors. Remarkably, HCC-FMT not only promoted tumor development but also induced spontaneous hepatic nodules in 9 of 16 mice without DEN treatment, while healthy donor FMT showed no such effects. These findings provide compelling mechanistic evidence supporting the clinical utility of intratumoral microbial biomarkers.

The clinical implications of these germ-free model findings extend beyond basic mechanistic understanding to practical biomarker development. The demonstration that specific bacterial communities can autonomously initiate hepatocarcinogenesis provides strong biological justification for their use as early diagnostic markers[11]. Moreover, the identification of targetable pathways, for example the PBP1B-TLR4 axis, suggests that microbial biomarkers could guide not only diagnosis and prognosis but also therapeutic intervention strategies. The ability of K. oxytoca to prevent Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in these models indicates potential for microbiome-based therapeutic approaches[11].

The heterogeneity observed across studies regarding microbial diversity patterns reflects both technical and biological complexities inherent to this emerging field[64,65]. Komiyama et al[32] found significantly higher microbiome diversity in liver tumor tissues compared to adjacent tissues, a finding corroborated by He et al[21], who identified consistent patterns of increased microbial richness in HCC tissues. However, subsequent investigations by multiple research groups failed to confirm these diversity differences[23,28,29,33], suggesting that diversity metrics alone are insufficient for hepatic malignancy diagnosis and that more sophisticated analytical approaches are necessary.

Our systematic analysis reveals that this variability likely stems from substantial methodological differences across studies. DNA extraction methods significantly impact bacterial recovery, with mechanical lysis protocols yielding 25%-40% higher detection rates for Gram-positive bacteria compared to enzymatic-only methods. Similarly, 16S rRNA region selection introduces systematic biases, with V4-only amplification underrepresenting Actinobacteria by approximately 30% compared to V3-V4 approaches, as documented in our Table 2. These technical variations, combined with differences in tissue processing protocols and patient population characteristics[26,30], likely explain the inconsistent diversity findings and highlight the critical need for standardized analytical frameworks.

Despite these challenges, methodological innovations have significantly enhanced the precision and reliability of intratumoral microbiome analysis[64]. Recent advances in FFPE tissue processing have overcome previous technical limitations, enabling retrospective analysis of large clinical cohorts and facilitating integration with existing pathological workflows[66]. Furthermore, spatial analysis techniques[67,68] using advanced imaging modalities have revealed previously unrecognized intratumoral microbial heterogeneity, particularly in multifocal HCC where distinct tumor nodules harbor unique microbial communities. These technological developments provide new opportunities for understanding tumor-microbe spatial relationships and their clinical implications.

Future adoption of consensus guidelines, such as the International Human Microbiome Standards protocols, will be essential for enabling quantitative meta-analyses and improving clinical translation potential. Only through standardization can the field move beyond observational heterogeneity toward clinically actionable biomarker development.

The prognostic applications of intratumoral microbiota demonstrate particular clinical promise, with multiple independent studies confirming associations between specific microbial taxa and patient survival outcomes[63,69]. The construction of sophisticated risk stratification frameworks that integrate multiple bacterial genera constitutes a substantial advancement in personalized prognostic evaluation. Nevertheless, the context-dependent nature of these associations, wherein microbial diversity demonstrates opposing prognostic implications across distinct cancer subtypes, underscores the intricate complexity of microbe-host interactions and necessitates validation studies specific to individual cancer types[70-72].

Germ-free model validation resolves a fundamental constraint inherent in human microbiome investigations, specifically the persistent challenge wherein observational research struggles to establish causal linkages. Whereas human studies may identify associations between microbial signatures and clinical outcomes, germ-free systems provide experimental validation that these signatures reflect genuine causal relationships. This experimental validation significantly strengthens the evidence base supporting clinical implementation of microbiome-based biomarkers in hepatic malignancies.

Mechanistic understanding has evolved considerably, revealing that intratumoral microorganisms function as active modulators of carcinogenesis rather than passive colonizers[62,63]. The demonstration of specific bacterial species promoting oncogenic pathway activation, modulating immune responses, and influencing epigenetic regulation provides compelling biological rationale for microbiome-based biomarker development. Recent discoveries linking microbial communities to DNA methylation[15] patterns and metabolic reprogramming expand our understanding of the mo

Furthermore, emerging evidence regarding fungal components of the tumor microbiome[73-75], particularly Malassezia species[27], adds another dimension to the complexity of tumor-resident microbial ecosystems. While our systematic review focuses specifically on hepatic malignancies, detailed mechanistic investigations in related gastrointestinal cancers provide valuable insights that likely extend to liver cancer pathogenesis.

Recent studies of F. nucleatum in esophageal and colorectal malignancies have elucidated sophisticated molecular mechanisms that may operate through analogous pathways in HCC, given the shared gut-liver anatomical axis and conserved oncogenic signaling networks. Nomoto et al[76] demonstrated that F. nucleatum employed precise invasion mechanisms, utilizing endocytosis to establish intracellular colonization and subsequently activating the NOD1/RIPK2/NF-κB signaling cascade. Their rigorous experimental validation included siRNA-mediated knockdown studies showing complete pathway dependency, where elimination of either NOD1 or NF-κB p65 entirely abolished tumor-promoting effects of F. nucleatum.

Yu et al[77] identified F. nucleatum-mediated epigenetic regulation through miR-5692a suppression, leading to IL-8 upregulation and ERK-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Additionally, Galasso et al[78] provided comprehensive molecular characterization revealing that F. nucleatum utilizes FadA adhesin to bind E-cadherin and VE-cadherin for cellular invasion, while employing the ALPK1/TIFA/NF-κB pathway for oncogenic signal activation. These mechanistic insights are particularly relevant to hepatic malignancies, as Wang et al[11] demonstrated similar bacterial-host interactions where Klebsiella pneumoniae activates TLR4-dependent signaling in HCC cells.

The convergence of these bacterial-mediated oncogenic pathways across digestive system malignancies provides strong biological rationale for the clinical biomarker applications identified in our hepatic malignancy analysis.

The therapeutic prediction applications of intratumoral microbiota remain less developed compared to diagnostic and prognostic uses, particularly for HCC-specific contexts[79]. While Akkermansia muciniphila enhances anti-PD-1 efficacy through IL-12-mediated CD8+ T cell activation in preclinical models, direct evidence in human HCC patients receiving immunotherapy remains scarce[80,81]. The mechanistic insights derived from pancreatic and colorectal cancer studies, though suggestive, require validation in HCC-specific contexts given the unique immunosuppressive microenvironment created by underlying cirrhosis and chronic viral infections[42,82]. Prospective studies correlating baseline intratumoral microbiome profiles with response to atezolizumab-bevacizumab or other checkpoint inhibitors in HCC patients represent a critical research priority[83,84].

The therapeutic implications of intratumoral microbiota extend beyond biomarker applications to encompass novel treatment strategies[85,86]. Understanding bacterial translocation mechanisms and their role in drug resistance provides opportunities for developing microbiome-targeted interventions. The identification of specific bacterial species that promote angiogenesis or immune suppression suggests potential targets for antimicrobial therapy as adjuvant cancer treatment[87]. However, the clinical implementation of such approaches requires careful consideration of potential adverse effects on beneficial microbial communities and overall patient health.

The predominance of Chinese studies investigating HBV-driven HCC in our review raises important questions about global applicability. Western populations with NASH-or alcohol-associated HCC may harbor fundamentally different microbial signatures, particularly regarding fungal components where Malassezia species and Candida albicans show stronger associations with metabolic etiologies[88,89]. Only 15% of included studies examined non-HBV etiologies, and none specifically focused on NASH-associated HCC despite its rapidly increasing incidence[90-93]. Pinter et al[94] found that NASH-HCC exhibits distinct immunosuppressive microbial profiles may explain its reduced immunotherapy responsiveness compared to viral-associated HCC. Development of globally applicable biomarkers will require geographically diverse, etiology-stratified studies that capture the full spectrum of hepatocarcinogenesis mechanisms.

Several critical limitations constrain the current evidence base and clinical implementation potential[95]. The predominantly cross-sectional nature of existing studies limits understanding of temporal microbial dynamics during hepatocarcinogenesis, while the reliance on relative abundance metrics may obscure important quantitative differences[96]. Technical challenges including low microbial biomass in hepatic tissues, potential contamination during sample processing, and spatial heterogeneity within tumors continue to pose analytical difficulties[64,97-99]. The absence of standardized methodological protocols across research centers hampers data comparability and meta-analytical approaches[66,95,96].

Publication bias represents another important consideration. Our restriction to English-language publications may have excluded research published in other languages, particularly from regions with high hepatic malignancy burdens where findings might be published in local journals. Additionally, the well-documented tendency for positive results to be preferentially published may inflate the apparent diagnostic and prognostic utility of microbial biomarkers. While we acknowledge these limitations, the comprehensive coverage of PubMed regarding peer-reviewed biomedical literature provides confidence that our review captures the majority of high-quality evidence within this domain.

While our systematic review reveals consistent associations between intratumoral microbiota and NF-κB pathway activation across hepatic malignancies, establishing definitive causal relationships requires rigorous experimental validation through loss-of-function studies. Recent investigations in related gastrointestinal malignancies provide compelling evidence for the necessity of gene knockout models in validating microbe-NF-κB interactions.

Nomoto et al[76] employed siRNA-mediated knockdown of both NOD1 and NF-κB p65 subunits, demonstrating that F. nucleatum-induced tumor progression is completely dependent on this signaling axis. Their rescue experiments showed that knockdown of either NOD1 or p65 completely abolished F. nucleatum's growth-promoting effects, providing definitive evidence for pathway dependency. Similarly, Zhang et al[100] utilized RelB siRNA knockdown strategies, revealing that F. nucleatum-mediated neutrophil recruitment and IL17A secretion were entirely RelB-dependent.

These mechanistic validation approaches emphasize the critical importance of functional studies in establishing causal relationships between intratumoral bacteria and oncogenic signaling pathways in hepatic malignancies. Future investigations should prioritize: (1) Construction of NF-κB subunit knockout HCC cell lines (p65, RelA, or IκBα) to assess F. nucleatum infection effects; (2) Development of ALPK1 knockout models, given role of this kinase as a key mediator of F. nucleatum-induced NF-κB activation; (3) Pharmacological validation using specific NF-κB inhibitors to assess reversibility of microbe-mediated tumor-promoting effects; and (4) Generation of liver-specific NF-κB component knockout mouse models to evaluate microbial colonization impacts on tumorigenesis.

Future research priorities should emphasize longitudinal cohort studies to characterize microbiome evolution during cancer progression and treatment, development of absolute quantification methods combining sequencing with targeted quantitative approaches, and multicenter validation studies using standardized protocols[62-64,66].

Moving beyond correlational findings to establish causality represents the critical next frontier. Specific approaches should include implementation of Mendelian randomization studies using microbial quantitative trait loci to establish causal relationships between specific taxa and hepatocarcinogenesis, randomized controlled trials testing microbiome-modulating interventions such as targeted antibiotics or precision probiotics in high-risk cirrhotic patients, and development of humanized gnotobiotic mouse models colonized with patient-derived microbiota to mechanistically validate causal pathways. Such interventional approaches, particularly FMT trials in precirrhotic patients, could definitively establish whether microbiome manipulation can prevent or delay HCC development. The success of germ-free models in establishing causality[11] suggests that similar experimental approaches should be extended to validate other microbial biomarkers identified in human studies.

Future methodological developments should also incorporate ecological modeling approaches to enhance our understanding of intratumoral microbial community dynamics. The application of island biogeography theory to cancer microbiome research, as demonstrated by Dovrolis et al[101] in colorectal cancer where tumor size explained 47% of microbial diversity variation, provides a theoretical framework for standardizing microbiome-based biomarkers in liver cancer. This ecological perspective suggests that tumor size and morphological complexity should be considered as normalization factors when developing diagnostic algorithms, potentially improving reproducibility across different hepatic malignancy subtypes and stages.

The integration of spatial multi-omics approaches with single-cell technologies promises to reveal new insights into microbe-host interactions at unprecedented resolution[62,64,66]. Machine learning methodologies may enhance predictive model performance through sophisticated pattern recognition and multi-modal data integration approaches[62,64]. These technological advances, combined with mechanistic validation through germ-free models and ecological frameworks, position the field for significant progress toward clinically actionable microbiome-based biomarkers in hepatic malignancies.

The path toward clinical implementation requires addressing regulatory frameworks, cost-effectiveness considerations, and integration with existing diagnostic algorithms[95,102]. The development of point-of-care testing platforms for key microbial biomarkers could facilitate widespread clinical adoption, while the establishment of quality control standards and proficiency testing programs would ensure analytical reliability across clinical laboratories. Economic evaluation studies comparing microbiome-based approaches to conventional biomarkers will be essential for healthcare policy decision-making[95,102].

The rapidly expanding understanding of intratumoral microbiota in hepatic malignancies positions this field at the threshold of clinical translation. The convergence of advancing analytical technologies, growing mechanistic insights, and accumulating clinical evidence suggests that microbiome-based biomarkers will soon transition from research applications to routine clinical practice[63,64,96]. The ultimate goal of improving patient outcomes through precision medicine approaches incorporating tumor microbiome characterization represents a realistic and achievable objective that could significantly impact hepatic malignancy management in the coming decade.

This systematic review of 20 high-quality studies demonstrates that intratumoral microbes represent promising clinical biomarkers for hepatic malignancies, with specific bacterial taxa achieving exceptional diagnostic accuracy (AUC > 0.9) and consistent prognostic associations with patient survival outcomes. Mechanistic evidence reveals that tumor-resident microorganisms actively modulate hepatocarcinogenesis through oncogenic pathway activation, immune microenvironment regulation, and drug resistance mechanisms, providing strong biological rationale for clinical application. The causative role of gut microbiota in hepatocarcinogenesis, definitively established through germ-free mouse models, transforms observational associations into mechanistically-grounded clinical tools. While standardized methodological protocols and multicenter validation studies remain essential prerequisites, the accumulating evidence positions microbiome-based biomarkers at the threshold of clinical translation, offering novel opportunities for precision diagnosis, prognostic stratification, and personalized treatment strategies in hepatic malignancy management.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of all researchers whose work was reviewed in this systematic analysis.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12644] [Article Influence: 6322.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | de Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Clifford GM. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e180-e190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1058] [Cited by in RCA: 1523] [Article Influence: 253.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huang Y, Fan XG, Wang ZM, Zhou JH, Tian XF, Li N. Identification of helicobacter species in human liver samples from patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:1273-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nejman D, Livyatan I, Fuks G, Gavert N, Zwang Y, Geller LT, Rotter-Maskowitz A, Weiser R, Mallel G, Gigi E, Meltser A, Douglas GM, Kamer I, Gopalakrishnan V, Dadosh T, Levin-Zaidman S, Avnet S, Atlan T, Cooper ZA, Arora R, Cogdill AP, Khan MAW, Ologun G, Bussi Y, Weinberger A, Lotan-Pompan M, Golani O, Perry G, Rokah M, Bahar-Shany K, Rozeman EA, Blank CU, Ronai A, Shaoul R, Amit A, Dorfman T, Kremer R, Cohen ZR, Harnof S, Siegal T, Yehuda-Shnaidman E, Gal-Yam EN, Shapira H, Baldini N, Langille MGI, Ben-Nun A, Kaufman B, Nissan A, Golan T, Dadiani M, Levanon K, Bar J, Yust-Katz S, Barshack I, Peeper DS, Raz DJ, Segal E, Wargo JA, Sandbank J, Shental N, Straussman R. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Science. 2020;368:973-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 1724] [Article Influence: 287.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gonzalez-Ferrer S, Peñaloza HF, Budnick JA, Bain WG, Nordstrom HR, Lee JS, Van Tyne D. Finding Order in the Chaos: Outstanding Questions in Klebsiella pneumoniae Pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2021;89:e00693-e00620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Russo TA, Marr CM. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32:e00001-e00019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 845] [Article Influence: 120.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Péré-Védrenne C, Cardinaud B, Varon C, Mocan I, Buissonnière A, Izotte J, Mégraud F, Ménard A. The Cytolethal Distending Toxin Subunit CdtB of Helicobacter Induces a Th17-related and Antimicrobial Signature in Intestinal and Hepatic Cells In Vitro. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:1979-1989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xue C, Jia J, Gu X, Zhou L, Lu J, Zheng Q, Su Y, Zheng S, Li L. Intratumoral bacteria interact with metabolites and genetic alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xue C, Gu X, Shi Q, Ma X, Jia J, Su Y, Bao Z, Lu J, Li L. The interaction between intratumoral bacteria and metabolic distortion in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2024;22:237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pushalkar S, Hundeyin M, Daley D, Zambirinis CP, Kurz E, Mishra A, Mohan N, Aykut B, Usyk M, Torres LE, Werba G, Zhang K, Guo Y, Li Q, Akkad N, Lall S, Wadowski B, Gutierrez J, Kochen Rossi JA, Herzog JW, Diskin B, Torres-Hernandez A, Leinwand J, Wang W, Taunk PS, Savadkar S, Janal M, Saxena A, Li X, Cohen D, Sartor RB, Saxena D, Miller G. The Pancreatic Cancer Microbiome Promotes Oncogenesis by Induction of Innate and Adaptive Immune Suppression. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:403-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 1073] [Article Influence: 134.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang X, Fang Y, Liang W, Cai Y, Wong CC, Wang J, Wang N, Lau HC, Jiao Y, Zhou X, Ye L, Mo M, Yang T, Fan M, Song L, Zhou H, Zhao Q, Chu ES, Liang M, Liu W, Liu X, Zhang S, Shang H, Wei H, Li X, Xu L, Liao B, Sung JJY, Kuang M, Yu J. Gut-liver translocation of pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae promotes hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Nat Microbiol. 2025;10:169-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ohtani N, Kamiya T, Kawada N. Recent updates on the role of the gut-liver axis in the pathogenesis of NAFLD/NASH, HCC, and beyond. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e0241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tilg H, Adolph TE, Trauner M. Gut-liver axis: Pathophysiological concepts and clinical implications. Cell Metab. 2022;34:1700-1718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 113.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhao ZH, Xin FZ, Xue Y, Hu Z, Han Y, Ma F, Zhou D, Liu XL, Cui A, Liu Z, Liu Y, Gao J, Pan Q, Li Y, Fan JG. Indole-3-propionic acid inhibits gut dysbiosis and endotoxin leakage to attenuate steatohepatitis in rats. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen W, Zhang X, Chi M, Zheng Q. Intratumoral Microbe Correlated with Expression of DNA Methylation Genes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2025;70:3383-3393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jiang F, Dang Y, Zhang Z, Yan Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Chen L, Zhang J, Liu J, Wang J. Association of intratumoral microbiome diversity with hepatocellular carcinoma prognosis. mSystems. 2025;10:e0076524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Song Y, Xiang Z, Lu Z, Su R, Shu W, Sui M, Wei X, Xu X. Identification of a brand intratumor microbiome signature for predicting prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:11319-11332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Parikh ND, Mehta AS, Singal AG, Block T, Marrero JA, Lok AS. Biomarkers for the Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:2495-2503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gok Yavuz B, Datar S, Chamseddine S, Mohamed YI, LaPelusa M, Lee SS, Hu ZI, Koay EJ, Tran Cao HS, Jalal PK, Daniel-MacDougall C, Hassan M, Duda DG, Amin HM, Kaseb AO. The Gut Microbiome as a Biomarker and Therapeutic Target in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:4875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chakladar J, Wong LM, Kuo SZ, Li WT, Yu MA, Chang EY, Wang XQ, Ongkeko WM. The Liver Microbiome Is Implicated in Cancer Prognosis and Modulated by Alcohol and Hepatitis B. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | He Y, Zhang Q, Yu X, Zhang S, Guo W. Overview of microbial profiles in human hepatocellular carcinoma and adjacent nontumor tissues. J Transl Med. 2023;21:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huang JH, Wang J, Chai XQ, Li ZC, Jiang YH, Li J, Liu X, Fan J, Cai JB, Liu F. The Intratumoral Bacterial Metataxonomic Signature of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10:e0098322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu B, Zhou Z, Jin Y, Lu J, Feng D, Peng R, Sun H, Mu X, Li C, Chen Y. Hepatic stellate cell activation and senescence induced by intrahepatic microbiota disturbances drive progression of liver cirrhosis toward hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:e003069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |