Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.112548

Revised: August 27, 2025

Accepted: November 3, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 6.7 Hours

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated significant efficacy in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients with microsatellite instability-high or deficient mismatch repair. However, their efficacy as monotherapy is limited in microsatellite stable/proficient mismatch repair (MSS/pMMR) subtypes.

To provide an evidence-based rationale for optimizing later-line therapeutic stra

This study conducted a systematic retrospective analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a triple-combination regimen comprising programmed death 1 inhi

Primary endpoints included progression-free survival and disease control rate. Intention-to-treat analysis showed median progression-free survival 7.0 months, median overall survival 18.5 months, disease control rate 61.5%, with manageable toxicity.

Although this is a small-sample retrospective study, it preliminarily validates the synergistic effect of programmed death 1 inhibitors combined with fruquintinib and docetaxel in MSS/pMMR CRC, providing a novel strategy with translational significance for later-line treatment in advanced patients.

Core Tip: This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a novel triple-combination regimen - programmed death 1 inhibitor + fruquintinib + docetaxel - as a third-line treatment for advanced microsatellite stable/proficient mismatch repair colorectal cancer. Primary endpoints included progression-free survival and disease control rate. Intention-to-treat analysis showed median progression-free survival 7.0 months, median overall survival 18.5 months, disease control rate 61.5%, with manageable toxicity. This study preliminarily validates the synergistic effect of programmed death 1 inhibitors combined with fruquintinib and docetaxel in microsatellite stable colorectal cancer, providing a novel strategy with translational significance for later-line treatment in advanced patients.

- Citation: Meng XY, Cai YM, Sun NN, Zhang WH, Cui RX, Zhang L, Zheng CC, Sun Z, Luo WX, Wang FW. Preliminary exploration of programmed death 1 inhibitor combined with fruquintinib and docetaxel for advanced colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(12): 112548

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i12/112548.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.112548

Colorectal cancer (CRC), a highly prevalent malignant tumor globally, presents significant challenges in the clinical management of metastatic cases. Epidemiological data indicate that approximately 20% of patients are diagnosed at metastatic stages, with a five-year survival rate below 15%. For microsatellite stable (MSS) advanced CRC patients who have progressed after second-line therapy, current third-line treatment options remain scarce and exhibit limited efficacy, necessitating exploration of novel therapeutic strategies.

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and malignant melanoma. However, in CRC, clinical benefits of immunotherapy are predominantly restricted to the microsatellite instability-high subtype. MSS tumors, which constitute approximately 85% of all CRC cases, are characterized by an immune microenvironment predominantly classified as immune-excluded or immune-desert subtypes. These tumors exhibit low levels of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and reduced tumor mutational burden[1], rendering them classic immunologically “cold” tumors. The KEYNOTE-016 study confirmed the general resistance of MSS metastatic CRC to monotherapy with ICIs[2]. Consequently, current clinical strategies primarily focus on combination approaches to enhance immunotherapy efficacy in MSS CRC. These include synergistic regimens integrating ICIs with chemoradiation, targeted therapies, and localized treatments, aiming to remodel the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Such combinatorial interventions seek to convert immunologically “cold” tumors into “hot” tumors, thereby enabling MSS CRC patients to derive clinical benefits from immunotherapy.

Current guidelines recommend third-line therapeutic regimens including small-molecule targeted agents (regorafenib, fruquintinib) and novel oral chemotherapeutic agents (trifluridine/tipiracil, TAS-102) as monotherapies. The CONCUR China trial demonstrated that regorafenib achieved a median overall survival (mOS) of 8.8 months and a median progression-free survival (mPFS) of 3.2 months in Chinese patients with advanced CRC receiving third-line therapy[3]. The TERRA China trial showed that TAS-102 provided a mOS of 7.8 months and a mPFS of 2.0 months in Chinese patients with advanced CRC undergoing third-line treatment[4]. Recent studies have revealed that anti-angiogenic agents may remodel the tumor microenvironment and potentiate the efficacy of ICIs, providing a theoretical rationale for combination strategies.

Studies have demonstrated that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGF receptor (VEGFR) inhibitors reduce tumor angiogenesis and promote vascular normalization, thereby enhancing oxygen and antitumor drug delivery while augmenting the infiltration of effector T cells. By inhibiting VEGFR phosphorylation on vascular endothelial cells and blocking downstream signaling transduction, it suppresses endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tubule formation, thereby inhibiting tumor neovascularization and ultimately exerting antitumor growth effects[5]. The phase III FRESCO trial[6] evaluated the efficacy and safety of fruquintinib in patients with metastatic CRC refractory to ≥ 2 prior lines of standard therapy. Results demonstrated that fruquintinib significantly prolonged mOS compared to placebo [9.3 months vs 6.57 months; hazard ratio (HR) = 0.65, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.51-0.83, P < 0.001] and mPFS (3.71 months vs 1.84 months; HR = 0.26, 95%CI: 0.21-0.34, P < 0.001). Adverse events (AEs) were consistent with the known class effects of antiangiogenic agents, including hypertension (grade ≥ 3: 21%), hand-foot syndrome (grade ≥ 3: 11%), and proteinuria (grade ≥ 3: 3%). Based on the FRESCO trial outcomes, fruquintinib has been approved as a monotherapy for patients with metastatic CRC who have previously received fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin-, and irinotecan-based chemotherapy, and who are ineligible for or refractory to prior anti-VEGF therapy or anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy.

Docetaxel exerts its antitumor effects through multifaceted mechanisms that synergize with ICIs to enhance therapeutic efficacy. By stabilizing microtubules and inhibiting depolymerization, docetaxel induces mitotic arrest and apoptosis in tumor cells[7]. This apoptotic process triggers the release of tumor-associated antigens such as neoantigens and damage-associated molecular patterns, including high mobility group box 1 and ATP. These immunogenic signals activate dendritic cells (DCs) through pattern recognition receptors (Toll-like receptor 4, P2X7), promoting DC maturation and upregulating co-stimulatory molecules like CD80/86. Activated DCs subsequently prime CD8+ T cells via major histocompatibility class-I-mediated antigen cross-presentation, bridging innate and adaptive immunity. The immunomodulatory effects of docetaxel extend beyond antigen release. It downregulates immunosuppressive populations including regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells through phosphatase and tensin homolog/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway modulation. This remodels the tumor microenvironment, reducing interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-β levels while enhancing effector T-cell infiltration and clonal expansion[8]. Notably, docetaxel suppresses VEGF expression, which normalizes tumor vasculature by decreasing aberrant angiogenesis and reducing interstitial fluid pressure. This vascular remodeling improves intratumoral penetration of programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors and reverses hypoxia-induced immunosuppression. PD-1 inhibitors amplify these effects by blocking the PD-1/programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) axis. The PD-1 receptor contains immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory and switch motifs that recruit SHP2 phosphatase upon ligand binding, suppressing T-cell receptor signaling through zeta-chain associated protein 70 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT dephosphorylation. Checkpoint inhibition reverses T-cell exhaustion by restoring CD28 co-stimulation and metabolic reprogramming, thereby enhancing cytotoxic T-lymphocyte functionality. Preclinical studies demonstrate synergistic effects when combining docetaxel with PD-1 blockade[9]. In non-small cell lung cancer models, the regimen increased tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells by 2.3-fold and upregulated interferon-γ production by 68% compared to monotherapy[10]. This immunogenic synergy correlates with improved antigen processing and presentation, as evidenced by 40% higher DC activation markers in combination therapy. Clinical validations confirm these mechanistic advantages. The LUME-Lung 1 trial[11] showed docetaxel plus nintedanib (a VEGF inhibitor) improved mPFS to 4.0 months vs 2.7 months for docetaxel alone.

The primary objective of this study is to preliminarily evaluate the impact of a triple-combination regimen (PD-1 inhibitor + fruquintinib+ docetaxel) on progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and disease control rate (DCR) in patients with advanced MSS/proficient mismatch repair (pMMR) CRC, while concurrently assessing the safety profile of this regimen. By exploring its clinical value, this work aims to provide an evidence-based rationale for optimizing later-line therapeutic strategies in this immunotherapy-resistant population.

This study conducted a retrospective analysis of clinical data from 13 patients with advanced MSS/pMMR CRC treated at our center between July 2023 and March 2025. All subjects were assigned to the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, regardless of whether they actually received the intervention, completed the treatment, or withdrew during the study. Subjects who strictly adhered to the study protocol were classified into the per-protocol (PP) population, excluding those who did not complete the treatment, had poor medication adherence, or violated key protocol requirements.

The analyzed dataset included: (1) Baseline characteristics: Sex, age, comorbidities, surgical history; (2) Treatment parameters: Third-line treatment cycles and efficacy evaluations; and (3) Safety outcomes: Treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) graded by CTCAE v5.0. Informed consent was waived by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tianjin Union Medical Center of Nankai University due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Patients were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: 18-75 years (inclusive), confirmed metastatic CRC with measurable lesions (per RECIST v1.1) having failed or demonstrated intolerance to ≥ 2 prior lines of standard systemic therapy for metastatic disease (including oxaliplatin- and irinotecan-based regimens), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1, life expectancy: ≥ 3 months, women of childbearing potential must use highly effective contraception (e.g., hormonal or barrier methods) during treatment and for ≥ 3 months after the last dose, demonstrated adherence to protocol requirements and willingness to complete scheduled follow-up assessments. The exclusion criteria included: Active autoimmune diseases or immunodeficiency disorders, severe cardiovascular comorbidities or uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mmHg despite medication), prior exposure to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors or other oral anti-angiogenic agents, central nervous system metastases or other conditions potentially confounding efficacy assessments, uncontrolled severe concurrent infections (e.g., active hepatitis B/C, human immunodeficiency virus, or bacterial sepsis).

Fruquintinib 5 mg orally once daily for 3 consecutive days followed by a 1-day break, repeated every 3 weeks (q3w). Camrelizumab administered 200 mg on day 1, q3w. Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 intravenously infused over 1 hour on day 1, q3w. Treatment cycles continue until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. A dynamic dose modification protocol is implemented based on patient tolerance: Treatment interruption is mandated for grade ≥ 3 TRAEs, with therapy resumed at reduced doses (stepwise dose reduction scheme) only after toxicity resolves to grade ≤ 1. Drug-related AEs during the trial were graded according to the NCI CTCAE version 5.0, and dose adjustments were made with reference to the prescribing information for the specific drugs in the protocol.

Primary endpoints include PFS: Systematically evaluated every 6 weeks via imaging (computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging) using RECIST v1.1 criteria. DCR: Calculated as the percentage of patients with stable disease (SD) lasting ≥ 8 weeks, integrated with longitudinal tumor marker (e.g., carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9) dynamics for comprehensive assessment. Secondary endpoints include ORR: Defined as the proportion of patients achieving complete response or partial response (PR); overall survival (OS): Measured from treatment initiation to death from any cause. Safety profile: Continuously monitored throughout the study. AEs are graded per CTCAE v5.0 criteria, with focused surveillance on hematologic toxicities (e.g., neutropenia, thrombocytopenia), immune-related AEs, and regimen-specific toxicities (e.g., hypertension, hand-foot syndrome).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 29.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). PFS and OS were evaluated through Kaplan-Meier survival curves, with statistical significance assessed by the log-rank test. Graphical representations were generated using GraphPad Prism 10.9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States).

A total of 13 patients with metastatic MSS/pMMR CRC meeting eligibility criteria were enrolled. The median follow-up time was 7 months. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The cohort exhibited typical CRC epidemiological profiles: Male predominance (69.2%, 9/13), median age of 68 years (range: 52-79), with 53.8% (7/13) aged ≥ 65 years, aligning with the aging trend in advanced CRC populations. Chronic comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes were present in 61.5% (8/13), underscoring the importance of comorbidity management for treatment safety. Molecular profiling revealed RAS mutation positivity in 38.5% (5/13). Notably, 38.5% (5/13) did not undergo complete biomarker profiling. Metastatic burden analysis showed ≥ 2 metastatic sites in 69.2% (9/13), with hepatic metastases (53.8%) and pulmonary metastases (46.2%) as predominant patterns, consistent with the natural progression of advanced CRC. All patients had ECOG performance status of 0-1, with 69.2% (9/13) classified as ECOG 0, indicating preserved baseline functional capacity.

| Characteristics | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 (69.2) |

| Female | 4 (30.8) |

| Age, years | |

| < 65 | 6 (46.2) |

| ≥ 65 | 7 (53.8) |

| Underlying chronic diseases | |

| Positive | 8 (61.5) |

| Negative | 5 (38.5) |

| RAS mutation | |

| Positive | 5 (38.5) |

| Negative | 3 (23.1) |

| Unknown | 5 (38.5) |

| Radical surgery | |

| Positive | 3 (23.1) |

| Negative | 10 (76.9) |

| Number of metastatic sites | |

| 1 | 4 (30.8) |

| ≥ 2 | 9 (69.2) |

| ECOG performance status score | |

| 0 | 9 (69.2) |

| 1 | 4 (30.8) |

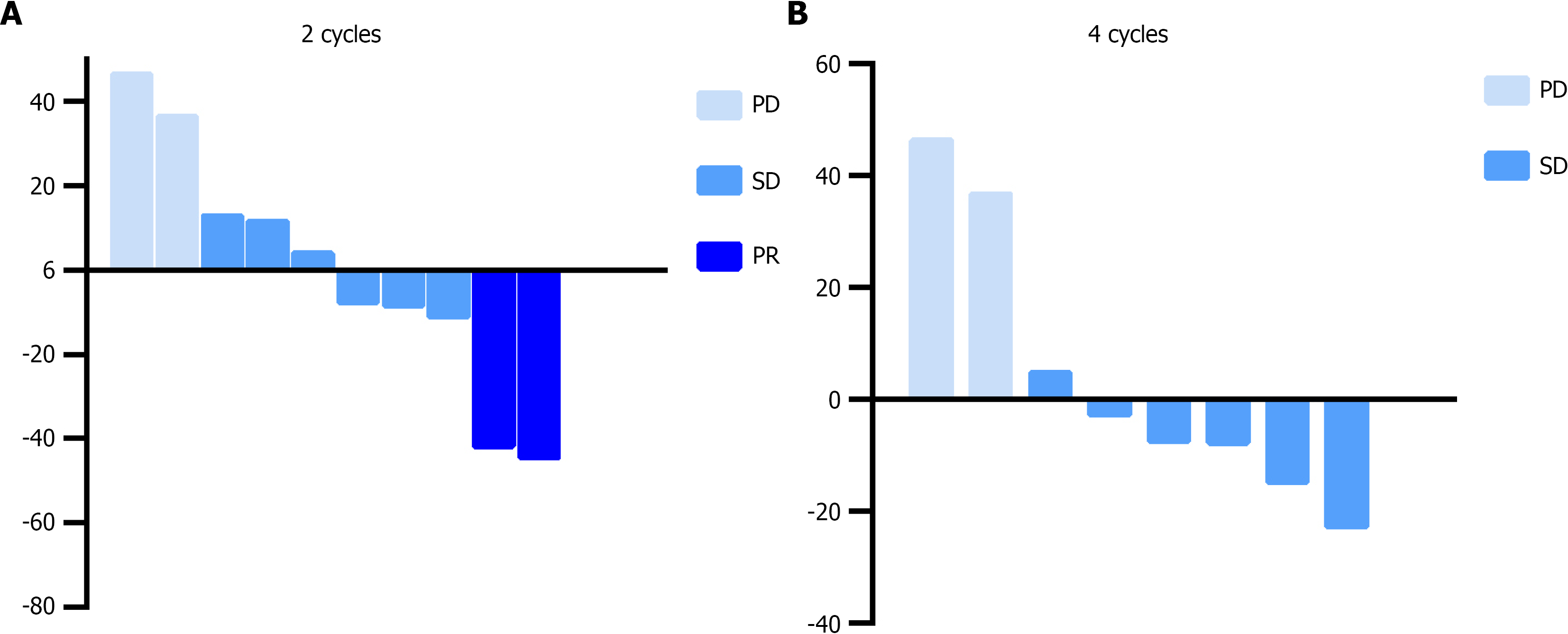

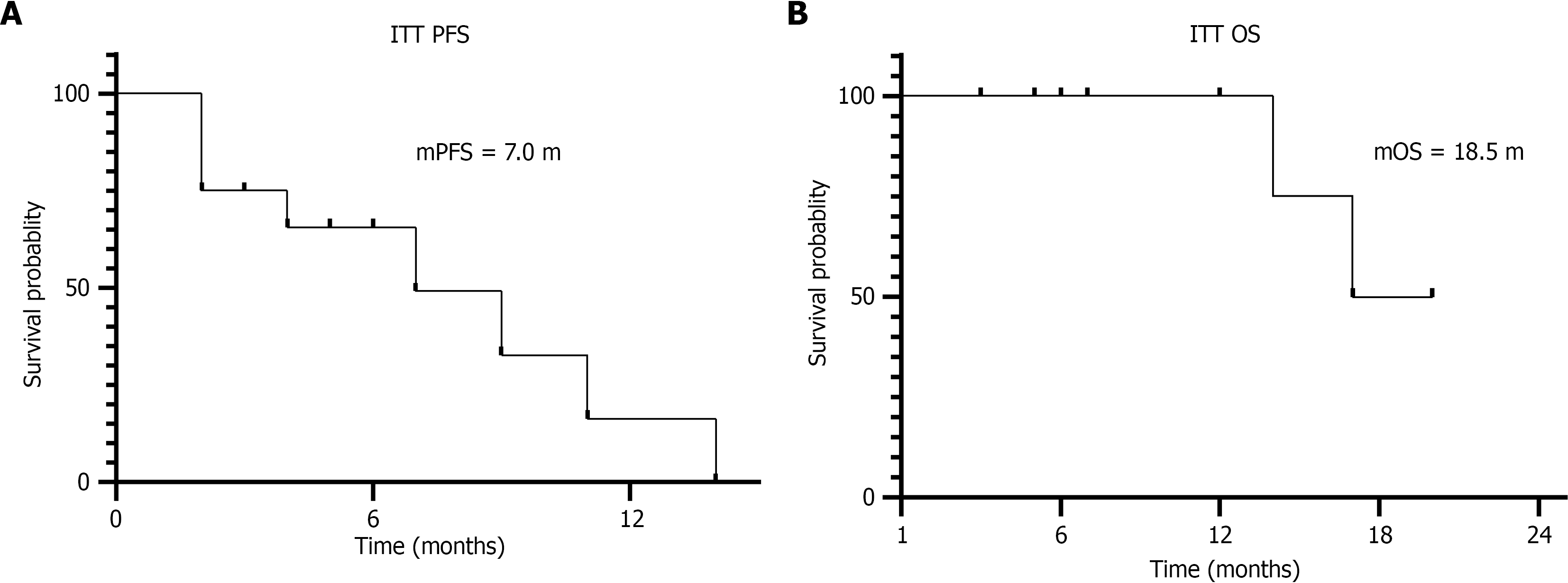

The study follow-up was completed on March 23, 2025. Among the 13 enrolled patients, two discontinued the triple therapy regimen after one cycle due to intolerable gastrointestinal toxicities (with one case lost to follow-up for both PFS and OS data), and one additional patient withdrew treatment because of fatigue and rash. In the ITT population, efficacy assessments after two treatment cycles revealed PR in 15.4% (2/13), SD in 46.2% (6/13), and progressive disease (PD) in 15.4% (2/13), yielding an ORR of 15.4% (95%CI: 2.7%-46.3%) and DCR (PR + SD) of 61.5% (95%CI: 32.3%-84.9%). By the fourth treatment cycle, 46.2% (6/13) maintained SD and 30.8% (4/13) progressed to PD, resulting in a declined DCR of 46.2%. In contrast, the PP population demonstrated improved outcomes: ORR of 20% and DCR of 80% after two cycles, with DCR sustained at 60% following four cycles (Table 2 and Figure 1). Survival analysis within the ITT population showed a mPFS of 7.0 months (95%CI: 1.72-12.28) and mOS of 18.5 months (95%CI: 15.31-20.19), as illustrated by Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Figure 2.

| Respond | ITT population | PP population | ||

| 2 cycles | 4 cycles | 2 cycles | 4 cycles | |

| PR | 2 (15.4) | 0 | 2 (20.0) | 0 |

| SD | 6 (46.2) | 6 (46.2) | 6 (60.0) | 6 (60.0) |

| PD | 2 (15.4) | 4 (30.8) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (40.0) |

| ORR | 2 (15.4) | 0 | 2 (20.0) | 0 |

| DCR | 8 (61.5) | 6 (46.2) | 8 (80.0) | 6 (60.0) |

A 64-year-old female with advanced sigmoid colon cancer underwent curative resection but subsequently developed hepatic metastasis. During first-line therapy, radiofrequency ablation was administered to control hepatic lesions. Following pulmonary and lymph node metastases, third-line therapy was initiated while hepatic lesions remained stable post-radiofrequency ablation. The patient exhibited good performance status (ECOG 1) and received 2 cycles of the triple-agent regimen (docetaxel, fruquintinib, and PD-1 inhibitor), achieving significant regression of lymph node metastases. Monochemotherapy was well-tolerated, with no myelosuppression or gastrointestinal toxicity. After 7 cycles, docetaxel was discontinued due to cumulative grade 3 myelosuppression, and therapy was adjusted to PD-1 inhibitor plus fruquintinib for 10 additional cycles before disease progression.

A 66-year-old male with advanced rectal cancer presented with oligometastatic disease (hepatic, pulmonary, and lymph node involvement) at diagnosis. With preserved functional status (ECOG 0), he responded well to first- and second-line therapies, maintaining disease control for nearly 3 years. Upon progression, third-line therapy with the triple regimen was initiated. After 2 cycles, imaging confirmed SD, which persisted through 10 cycles. The regimen was paused due to acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding, requiring transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and localized rectal intervention. Maintenance therapy with PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy was continued. Both patients attained prolonged PFS of 17.3 months and 20.1 months, respectively, exceeding the cohort’s mPFS (7.0 months).

As detailed in Table 3, 2 of 13 patients (15.4%) discontinued treatment due to intolerable grade 2-3 gastrointestinal toxicities, while 1 patient (7.7%) withdrew because of persistent fatigue (grade 2) and rash (grade 1). Notably, 1 patient developed grade 3 immune-related myocarditis after 4 cycles of therapy, which resolved with corticosteroid therapy (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day tapered over 4 weeks); subsequent treatment continued with fruquintinib and docetaxel after PD-1 inhibitor discontinuation. Additionally, 1 patient experienced grade 2 gastrointestinal hemorrhage following 12 cycles, leading to permanent discontinuation of docetaxel and fruquintinib, with anti-PD-1 monotherapy maintained as palliative treatment. The remaining patients predominantly experienced grade 1-2 AEs, including fatigue (61.5%, 8/13), rash (38.5%, 5/13), neutropenia (30.8%, 4/13), and hypothyroidism (23.1%, 3/13). No grade ≥ 4 TRAEs were observed. The majority of patients (84.6%, 11/13) tolerated the regimen with dose adjustments, indicating a manageable overall safety profile.

| Adverse events | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

| Nausea | 0 | 2 (15.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 3 (23.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 1 (7.7) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Rash | 1 (7.7) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 0 |

| Immune-related myocarditis | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 |

This study conducted a retrospective analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a triple-combination regimen comprising PD-1 inhibitors, fruquintinib and docetaxel as third-line therapy in patients with advanced MSS/pMMR CRC. The results demonstrated a mPFS of 7.0 months and mOS of 18.5 months in the ITT population, with a DCR of 61.5% and a manageable safety profile (grade ≥ 3 AEs in 7.7%). Below, we discuss mechanistic synergies (e.g., VEGF inhibition enhancing T-cell infiltration), cross-trial comparisons (e.g., superior mPFS vs regorafenib/TAS-102 historical data), toxicity mitigation strategies (e.g., prophylactic steroid use for immune-related AEs), molecular predictors (e.g., RAS/BRAF mutational status correlation), and study limitations (small sample size, single-arm design). These findings highlight the innovative potential of this regimen to address unmet needs in refractory MSS CRC, warranting further validation in randomized phase II trials.

This therapeutic strategy was designed to exploit multi-dimensional synergies among anti-angiogenesis, immune activation, and chemocytotoxicity: Fruquintinib, a highly selective VEGFR1-3 inhibitor, suppresses tumor angiogenesis while remodeling the immunosuppressive microenvironment through reducing regulatory T-cell infiltration and enhancing effector T-cell recruitment. Docetaxel, a taxane chemotherapeutic agent, induces microtubule stabilization-mediated apoptosis and potentiates PD-1 blockade efficacy via immunogenic cell death, which releases tumor-associated antigens to prime adaptive immunity[12]. PD-1 inhibitors reverse T-cell exhaustion by blocking PD-1/PD-L1 signaling, creating a self-reinforcing cycle with fruquintinib’s vascular normalization effects. Emerging real-world evidence supports the PD-1/fruquintinib synergy[13], but our study pioneers the integration of docetaxel, achieving enhanced anti-tumor activity. For instance, the FRESCO-2 trial (NCT04322539) reported mPFS of 3.7 months for fruquintinib monotherapy in third-line MSS CRC, whereas our triple regimen extended mPFS to 7.0 months, demonstrating the chemotherapy-augmented immunomodulatory effect. This represents a paradigm shift in targeting “immune-cold” MSS CRC, where traditional immunotherapy has historically shown limited efficacy.

The liver represents the most common metastatic site in CRC, with hepatic metastases being a key determinant of poor prognosis. While immunotherapy efficacy is generally attenuated in liver-dominant disease - potentially due to hepatic immune tolerance mediated by Kupffer cell-mediated T-cell depletion and PD-L1 upregulation in metastatic niches - our study demonstrated comparable survival outcomes between patients with (53.8%) and without liver metastases (P > 0.05 by log-rank test). This observation may reflect docetaxel’s specific activity against hepatic lesions, supported by its established efficacy in breast and prostate cancer liver metastases through hypoxia-inducible factor 1α pathway inhibition, which may simultaneously enhance local immune responses by alleviating tumor hypoxia. Notably, one patient with extensive bilobar metastases achieved sustained SD for 12 treatment cycles, accompanied by a 60% reduction in hepatic lesion sum diameters (per RECIST 1.1), suggesting that chemotherapy-induced immunogenic modulation may potentiate checkpoint inhibitor activity in traditionally “immune-excluded” hepatic metastases. These findings warrant further exploration in liver-directed combination trials.

This study provides a preliminary evaluation of a novel third-line therapeutic approach, with its outcomes comparatively analyzed against conventional third-line regimens in Table 4: MPFS of 7.0 months vs 3.2 months for regorafenib (CONCUR trial[3]) and mOS of 18.5 months vs 8.8 months (regorafenib) or 7.8 months (TAS-102, TERRA trial[4]). Among recent combination therapies: The fruquintinib + PD-1 combination achieved mPFS of 5.5 months and mOS of 19.5 months, while the REGONIVO trial (regorafenib + nivolumab[14]) reported 0% ORR. The CAPability-01 study (chidamide + bevacizumab + PD-1[15]) showed higher ORR (44%) and comparable mPFS (7.3 months), but with grade 3/4 AEs in 62% vs 7.7% treatment discontinuation in our study. Although our ORR (15.4%) and DCR (61.5%) were numerically lower than CAPability-01, the favorable safety profile (e.g., docetaxel dose optimized at 60 mg/m2) suggests a balanced design better suited for frail patients with compromised performance status. These data position the triple regimen as a viable third-line option for MSS CRC, particularly where toxicity management is prioritized over maximal response. Although the mPFS and mOS numerically surpass historical controls, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the non-randomized, small-sample, retrospective design of this study, and no causal relationship can be established.

| Ref. | Treatment | mPFS, months | mOS, months | DCR, % | ≥ grade 2 AE, % |

| CONCUR[3] | Regorafenib | 3.2 | 8.8 | 51.0 | 54.0 |

| TERRA[4] | TAS-102 | 2.0 | 7.8 | 44.0 | 45.8 |

| FRESCO[6] | Fruquintinib | 3.7 | 9.3 | 62.0 | 46.0 |

| RAMTAS/IKF643 (ESMO 2024 LBA25) | TAS-102 + ramucirumab | 2.37 | 7.46 | 39.4 | 55.9 |

| SUNLIGHT[17] | TAS-102 + bevacizumab | 5.6 | 10.8 | 76.6 | 72.0 |

| RIN[18] | Regorafentib + ipilimumab + nivolumab | 4.0 | 20.0 | 62.1 | 65.5 (irAE) |

| CAPability-01[15] | Chidamide + bevacizumab + PD-1 | 3.7 | 12.0 | 56.3 | 60.0 |

| REGONIVO[14] | Regorafenib + nivolumab | 7.9 | NR | - | 40 |

In this study, 23.1% (3/13) of patients self-discontinued treatment after one cycle due to intolerable AEs, including grade 2 gastrointestinal toxicities (15.4%, 2/13) and grade 1-2 fatigue/rash (7.7%, 1/13). During subsequent therapy, one patient developed grade 2 immune-related myocarditis, leading to permanent anti-PD-1 discontinuation, and another experienced grade 3 gastrointestinal hemorrhage, prompting cessation of fruquintinib and docetaxel. Notably, the KEYNOTE-651 trial (NCT03467984) observed grade 3/4 neutropenia in 43% with pembrolizumab + mFOLFOX, whereas only one myelosuppression-related discontinuation occurred in our cohort. This discrepancy may stem from monochemotherapy intensity (docetaxel alone vs FOLFOX), limited sample size, or optimized supportive care (e.g., traditional Chinese medicine-based toxicity mitigation protocols at this integrative oncology center). These findings underscore the critical role of regimen tailoring and multidisciplinary support in balancing efficacy and safety.

Patients with advanced CRC undergoing third-line therapy often exhibit compromised treatment tolerance due to cumulative toxicities from prior multi-cycle targeted and cytotoxic therapies, necessitating real-time dose/therapeutic regimen adjustments based on individual tolerance profiles. In this study, two patients maintained durable disease control (SD > 8 months) following chemotherapy dose reduction or discontinuation, supporting the feasibility of a stepwise treatment approach: Initial triplet regimen intensification to achieve rapid tumor control, followed by staged therapeutic de-escalation guided by tolerability metrics. This strategy aligns with the sequential therapy paradigm demonstrated in the REVERCE trial (regorafenib → cetuximab; OS 17.4 months), where phased regimen sequencing optimized survival outcomes. By incorporating adaptive dosing thresholds (e.g., docetaxel reduction to 40 mg/m2 for grade 2 neutropenia) and biomarker-driven maintenance (e.g., fruquintinib continuation post-chemotherapy hold), our protocol may further refine survival benefits while mitigating cumulative toxicities, representing a personalized precision oncology model for refractory MSS CRC populations.

The observed lack of association between RAS mutations (38.5%, 5/13) and survival outcomes (mPFS: P > 0.05; mOS: P > 0.05) in this study. This divergence may stem from multifaceted biological and methodological factors. First, limited statistical power due to small RAS-mutant subgroup (n = 5) likely obscured true prognostic effects. Preclinical models reveal KRAS-mutant CRC comprises distinct molecular subtypes (KM1 vs KM2) with 14.3-month OS differences, suggesting our cohort might be enriched with indolent KM1 tumors characterized by cell cycle activation rather than stromal invasion phenotypes. Second, docetaxel’s pharmacological properties may counteract RAS-driven resistance. Mechanistically, docetaxel suppresses extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation through dual mechanisms: Destabilizing RAS-RAF membrane complexes and activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase/p38-BIM apoptotic axis. PDX models show docetaxel reduces mitogen-activated protein kinases signaling activity by 41% in KRAS-mutant tumors, potentially mitigating canonical RAS pathway hyperactivity. Third, combinatorial PD-1 inhibition might remodel immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment - docetaxel reduces regulatory T cells (38.2%) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (52.4%) while normalizing tumor vasculature via VEGF suppression (57.8% decrease), creating a permissive milieu for CD8+ T-cell infiltration and clonal expansion (2.3-fold increase). To validate these hypotheses, future investigations should employ multi-omics integration: Single-cell transcriptomics to decode tumor-immune dynamics, particularly CD49f+ tumor-initiating cells’ crosstalk with SPP1+ macrophages and COL11A1+ cancer-associated fibroblasts that drive collagen barrier formation; phosphoproteomics to map real-time kinase network rewiring, focusing on extracellular signal-regulated kinase/AKT/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 axis modulation during docetaxel exposure; spatial proteogenomics to identify PD-1/PD-L1 interaction hotspots predictive of response. Machine learning frameworks integrating STING pathway activation scores with T-cell receptor clonality indices could optimize patient stratification. Expanding cohorts to ≥ 50 RAS-mutant cases with KM1/KM2 subtyping will enhance statistical validity, while exploring KRASG12C inhibitor (e.g., AMG510) sequencing with docetaxel may yield synergistic efficacy (3.2-fold tumor regression in preclinical models). These approaches exemplify functional precision oncology paradigms bridging genomic landscapes with therapeutic adaptation. Future studies should prospectively incorporate molecular markers such as RAS and BRAF and explore their correlation with treatment outcomes.

This single-center, exploratory trial with a limited sample size (n = 13) carries inherent risks of selection bias, as evidenced by the overrepresentation of patients with favorable performance status, potentially overestimating clinical efficacy. Given that this single-arm retrospective study encountered undersampled biomarker data during collection, which precluded meaningful analysis, subsequent research should prioritize both increased sample size and enhanced capture of biomarker profiles. Future investigations could further strengthen rigor and feasibility through multicenter collaborations to aggregate analogous patient data on standard third-line therapies, enabling head-to-head comparative studies. Due to the limited sample size, subgroup analyses (including ECOG performance status, tumor differentiation grade, and number of cycles of third-line therapy, etc.) showed no statistically significant differences in survival outcomes. Consequently, no independent prognostic risk factors were identified in this study. To validate these findings, multicenter randomized controlled trials comparing triplet vs doublet regimens are warranted. Furthermore, the absence of immune-related biomarkers (e.g., CD8+ T-cell infiltration density, PD-L1 expression) due to technical constraints limits the development of predictive efficacy models. The VOLTAGE trial (NCT02948348) identified CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio and PD-L1 positivity as predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy response in MSS rectal cancer[16], underscoring the need to integrate multi-omics profiling (spatial transcriptomics, multiplex immunohistochemistry) in future studies to refine patient selection and elucidate resistance mechanisms. We propose a prospective, randomized controlled phase II clinical trial to further validate these findings, comparing fruquintinib combined with ICIs and docetaxel vs fruquintinib monotherapy as third-line treatment for MSS/pMMR advanced CRC.

This study provides preliminary evidence supporting the feasibility of combining PD-1 inhibitors, fruquintinib, and docetaxel as a third-line therapeutic strategy for MSS/pMMR advanced CRC. The regimen demonstrated superior survival outcomes (mPFS: 7.0 months; mOS: 18.5 months) compared to historical benchmarks, while dynamic dose adjustments enabled a manageable safety profile. However, this study represents a preliminary, exploratory retrospective analysis with a limited cohort size, and the findings necessitate further validation through large-scale prospective trials to confirm reproducibility and generalizability. Despite these limitations, combinatorial chemoimmunotherapy-antiangiogenic strategies represent a promising avenue for refractory MSS CRC. Future studies should prioritize combinatorial optimization and biomarker-driven patient stratification to overcome therapeutic challenges in this immunologically cold tumor subtype.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients and their families for participating in this study. We extend our sincere appreciation to the clinical teams at Department of Oncology, Tianjin Union Medical Center of Nankai University, for their support in patient recruitment, data collection, and trial coordination.

| 1. | Ganesh K, Stadler ZK, Cercek A, Mendelsohn RB, Shia J, Segal NH, Diaz LA Jr. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: rationale, challenges and potential. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:361-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1114] [Cited by in RCA: 1372] [Article Influence: 196.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, Biedrzycki B, Donehower RC, Zaheer A, Fisher GA, Crocenzi TS, Lee JJ, Duffy SM, Goldberg RM, de la Chapelle A, Koshiji M, Bhaijee F, Huebner T, Hruban RH, Wood LD, Cuka N, Pardoll DM, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Zhou S, Cornish TC, Taube JM, Anders RA, Eshleman JR, Vogelstein B, Diaz LA Jr. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509-2520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6096] [Cited by in RCA: 7494] [Article Influence: 681.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Li J, Qin S, Xu R, Yau TC, Ma B, Pan H, Xu J, Bai Y, Chi Y, Wang L, Yeh KH, Bi F, Cheng Y, Le AT, Lin JK, Liu T, Ma D, Kappeler C, Kalmus J, Kim TW; CONCUR Investigators. Regorafenib plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CONCUR): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:619-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 455] [Cited by in RCA: 602] [Article Influence: 54.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xu J, Kim TW, Shen L, Sriuranpong V, Pan H, Xu R, Guo W, Han SW, Liu T, Park YS, Shi C, Bai Y, Bi F, Ahn JB, Qin S, Li Q, Wu C, Ma D, Lin D, Li J. Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase III Trial of Trifluridine/Tipiracil (TAS-102) Monotherapy in Asian Patients With Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The TERRA Study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:350-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:325-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 745] [Cited by in RCA: 1533] [Article Influence: 191.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li J, Qin S, Xu RH, Shen L, Xu J, Bai Y, Yang L, Deng Y, Chen ZD, Zhong H, Pan H, Guo W, Shu Y, Yuan Y, Zhou J, Xu N, Liu T, Ma D, Wu C, Cheng Y, Chen D, Li W, Sun S, Yu Z, Cao P, Chen H, Wang J, Wang S, Wang H, Fan S, Hua Y, Su W. Effect of Fruquintinib vs Placebo on Overall Survival in Patients With Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The FRESCO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319:2486-2496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Tabaczar S, Koceva-Chyła A, Matczak K, Gwoździński K. [Molecular mechanisms of antitumor activity of taxanes. I. Interaction of docetaxel with microtubules]. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2010;64:568-581. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Garnett CT, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Combination of docetaxel and recombinant vaccine enhances T-cell responses and antitumor activity: effects of docetaxel on immune enhancement. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3536-3544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ma Z, Zhang W, Dong B, Xin Z, Ji Y, Su R, Shen K, Pan J, Wang Q, Xue W. Docetaxel remodels prostate cancer immune microenvironment and enhances checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Theranostics. 2022;12:4965-4979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zheng H, Zeltsman M, Zauderer MG, Eguchi T, Vaghjiani RG, Adusumilli PS. Chemotherapy-induced immunomodulation in non-small-cell lung cancer: a rationale for combination chemoimmunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:913-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Reck M, Kaiser R, Mellemgaard A, Douillard JY, Orlov S, Krzakowski M, von Pawel J, Gottfried M, Bondarenko I, Liao M, Gann CN, Barrueco J, Gaschler-Markefski B, Novello S; LUME-Lung 1 Study Group. Docetaxel plus nintedanib versus docetaxel plus placebo in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (LUME-Lung 1): a phase 3, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:143-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in RCA: 740] [Article Influence: 61.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou S, Wang B, Wei Y, Dai P, Chen Y, Xiao Y, Xia H, Chen C, Yin W. PD-1 inhibitor combined with Docetaxel exerts synergistic anti-prostate cancer effect in mice by down-regulating the expression of PI3K/AKT/NFKB-P65/PD-L1 signaling pathway. Cancer Biomark. 2024;40:47-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | He L, Cheng X, Gu Y, Zhou C, Li Q, Zhang B, Cheng X, Tu S. Fruquintinib Combined With PD-1 Inhibitors for the Treatment of the Patients With Microsatellite Stability Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Real-World Data. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2025;38:103700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fukuoka S, Hara H, Takahashi N, Kojima T, Kawazoe A, Asayama M, Yoshii T, Kotani D, Tamura H, Mikamoto Y, Hirano N, Wakabayashi M, Nomura S, Sato A, Kuwata T, Togashi Y, Nishikawa H, Shitara K. Regorafenib Plus Nivolumab in Patients With Advanced Gastric or Colorectal Cancer: An Open-Label, Dose-Escalation, and Dose-Expansion Phase Ib Trial (REGONIVO, EPOC1603). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2053-2061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 98.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang F, Jin Y, Wang M, Luo HY, Fang WJ, Wang YN, Chen YX, Huang RJ, Guan WL, Li JB, Li YH, Wang FH, Hu XH, Zhang YQ, Qiu MZ, Liu LL, Wang ZX, Ren C, Wang DS, Zhang DS, Wang ZQ, Liao WT, Tian L, Zhao Q, Xu RH. Combined anti-PD-1, HDAC inhibitor and anti-VEGF for MSS/pMMR colorectal cancer: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2024;30:1035-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Grassi E, Zingaretti C, Petracci E, Corbelli J, Papiani G, Banchelli I, Valli I, Frassineti GL, Passardi A, Di Bartolomeo M, Pietrantonio F, Gelsomino F, Carandina I, Banzi M, Martella L, Bonetti AV, Boccaccino A, Molinari C, Marisi G, Ugolini G, Nanni O, Tamberi S. Phase II study of capecitabine-based concomitant chemoradiation followed by durvalumab as a neoadjuvant strategy in locally advanced rectal cancer: the PANDORA trial. ESMO Open. 2023;8:101824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Prager GW, Taieb J, Fakih M, Ciardiello F, Van Cutsem E, Elez E, Cruz FM, Wyrwicz L, Stroyakovskiy D, Pápai Z, Poureau PG, Liposits G, Cremolini C, Bondarenko I, Modest DP, Benhadji KA, Amellal N, Leger C, Vidot L, Tabernero J; SUNLIGHT Investigators. Trifluridine-Tipiracil and Bevacizumab in Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1657-1667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 87.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fakih M, Sandhu J, Lim D, Li X, Li S, Wang C. Regorafenib, Ipilimumab, and Nivolumab for Patients With Microsatellite Stable Colorectal Cancer and Disease Progression With Prior Chemotherapy: A Phase 1 Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9:627-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/