Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.112366

Revised: August 29, 2025

Accepted: October 29, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 139 Days and 23.2 Hours

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a highly aggressive malignancy with limited the

To investigate the roles of glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GDCA) and deoxycholic acid (DCA) in CCA progression through Hippo-YAP signaling and to evaluate the effects of YAP-targeted interventions.

The in vitro experiments were performed using HuCCT1 CCA cells treated with GDCA, DCA, and combinations with a YAP inhibitor (verteporfin) or agonist (GA-017). Key molecular changes in the Hippo-YAP pathway were assessed by western blot, immunofluorescence, and reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Functional assays, including Cell Counting Kit-8, 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine, Transwell, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate-nick end labelling, were conducted to eva

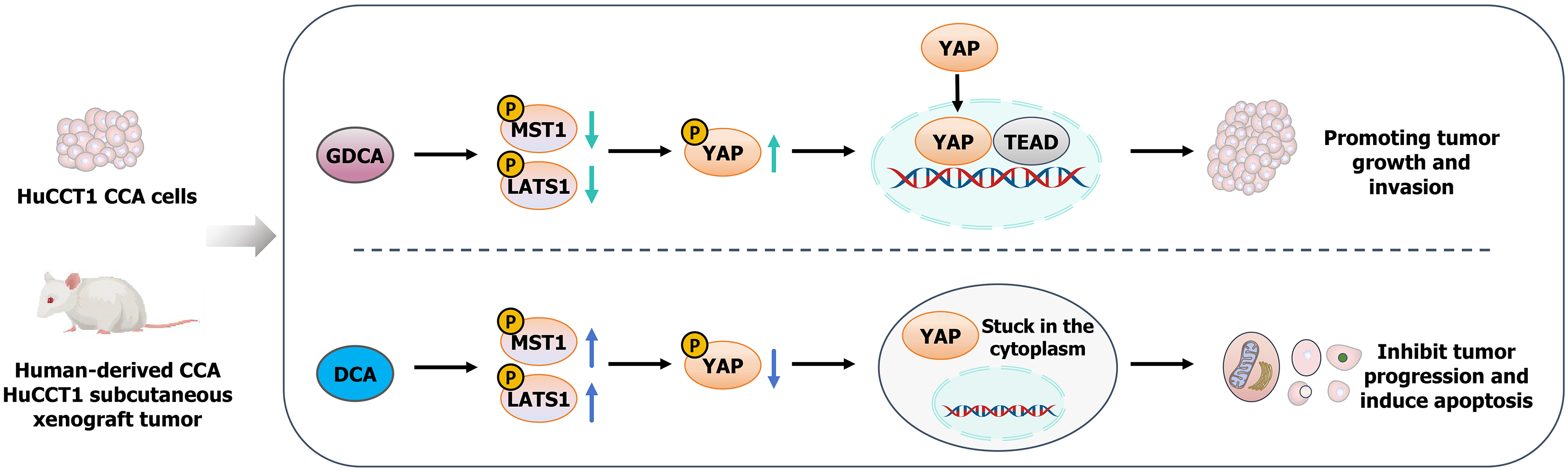

The GDCA significantly activated YAP by reducing mammalian STE20-like protein kinase 1 and large tumor suppressor 1 phosphorylation, promoting YAP nuclear translocation, and enhancing tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. In contrast, DCA inhibited YAP activation, suppressed tumor cell functions, and increased apoptosis. GDCA combined with YAP inhibitors attenuated its tumor-promoting effects, while DCA combined with YAP agonists reversed its inhibitory effects. In vivo, GDCA accelerated tumor growth, while DCA reduced tumor size and weight, with molecular changes consistent with in vitro findings.

The GDCA and DCA exert opposing effects on CCA progression through Hippo-YAP signaling. GDCA promotes tumor growth via YAP activation, while DCA inhibits these processes. YAP-targeted interventions demonstrate therapeutic potential, providing insights into new treatment strategies for CCA.

Core Tip: Cholangiocarcinoma is a highly aggressive malignancy with limited therapeutic options. This study demonstrates that glycochenodeoxycholic acid promotes tumor growth and aggressiveness by activating the Hippo-yes-associated protein (YAP) signaling pathway, whereas deoxycholic acid suppresses tumor progression by enhancing YAP phosphorylation and inducing apoptosis. The use of YAP modulators further confirmed the opposing roles of these bile acids. These findings provide novel mechanistic insights and highlight YAP as a potential therapeutic target, offering new perspectives for bile acid-based intervention strategies in cholangiocarcinoma.

- Citation: Hu J, Zhang G, Yang S, Shen XF, Zhou M, Huang LS, Lan HM. Involvement of bile acids in cholangiocarcinoma progression via the Hippo-yes-associated protein signaling pathway. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(12): 112366

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i12/112366.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.112366

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a highly aggressive malignancy originating from the biliary epithelium[1]. Its incidence has been increasing globally, with marked regional variations[2]. For example, Southeast Asia and the Far East report some of the highest rates of CCA, largely attributed to endemic liver fluke infections[3]. In contrast, Western countries have experienced a rising incidence associated with chronic liver diseases, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, hepatitis C, and metabolic disorders[4]. Despite advances in early detection and treatment, the prognosis for CCA remains dismal, with a 5-year survival rate below 20% for most patients[5,6]. The limited therapeutic options highlight the critical need to explore molecular mechanisms underlying CCA progression and identify novel therapeutic targets.

The Hippo-yes-associated protein (YAP) signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, and tissue homeostasis[7,8]. This highly conserved pathway involves a kinase cascade where the core kinases mammalian STE20-like protein kinase (MST) 1/2 and large tumor suppressor kinase (LATS) 1/2 phosphorylate and inactivate the effector protein YAP[9]. Phosphorylated YAP is sequestered in the cytoplasm and targeted for degradation, while dephosphorylated YAP translocate to the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors such as transcriptional enhanced associate domain to promote the expression of genes involved in cell growth, survival, and migration[10,11]. Dysregulation of Hippo-YAP signaling has been implicated in a wide range of cancers, including liver, colorectal, and biliary tract cancers[12,13]. In CCA, aberrant YAP activation has been associated with increased tumor aggressiveness and resistance to therapy, suggesting a critical role for this pathway in CCA progression[14].

Recent studies have identified bile acids as key modulators of the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway[15]. Bile acids, which are essential for lipid digestion and absorption, also function as signaling molecules that influence cell fate decisions and tumor progression[16]. Glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GDCA), a primary bile acid, has been shown to inhibit MST1/2 and LATS1/2 phosphorylation, leading to YAP activation and enhanced oncogenic signaling[17]. Conversely, secondary bile acids such as deoxycholic acid (DCA) have demonstrated variable effects, including pro-apoptotic and anti-migratory actions, depending on the cellular context[18]. Beyond their direct impact on tumor cells, bile acids can interact with oncogenic pathways including Wnt/β-catenin, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B, thereby contributing to tumor initiation and progression[19,20]. Importantly, accumulating evidence indicates that bile acids regulate Hippo-YAP activity through multiple mechanisms, such as modulating upstream kinases, affecting YAP/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif nuclear translocation, and influencing transcriptional programs related to proliferation and apoptosis[21,22]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, bile acid-mediated YAP activation has been linked to increased tumor growth and metastatic potential, highlighting the importance of understanding the interplay between bile acids and Hippo-YAP signaling in cancer[23]. Among bile acids, GDCA and DCA represent two functionally distinct molecules with opposing effects in various cancers. GDCA has been reported to promote tumor progression by enhancing cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis, while DCA has exhibited tumor-suppressive effects under certain conditions, inducing apoptosis and impairing cell migration[24]. However, the specific roles of GDCA and DCA in modulating the Hippo-YAP pathway in CCA remain unclear. Furthermore, little is known about how YAP-targeted interventions, such as inhibitors or agonists, might modulate these effects and contribute to therapeutic strategies for CCA.

This study aims to address these gaps by elucidating the molecular mechanisms through which GDCA and DCA regulate the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway in CCA. We further evaluate the effects of YAP inhibitors and agonists on tumor growth, cellular behaviors, and molecular signaling, providing insights into potential therapeutic strategies for this challenging malignancy.

This study included both in vivo and in vitro experiments, with consistent grouping across the two settings. The animal model involved 4-6 weeks old male BALB/c nude mice (18-22 g), and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. HuCCT1 CCA cells (PDM-219; American Type Culture Collection, VA, United States) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. For the in vivo model, 1 × 107 HuCCT1 cells/mL were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 100 μL of the cell suspension was subcutaneously injected into the right flank of each mouse. For in vitro experiments, HuCCT1 cells were seeded in six-well plates and treated under the same grouping scheme as the in vivo model. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Taihe Hospital, Hubei University of Medicine (Approval No. SY-KY20250105) and performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

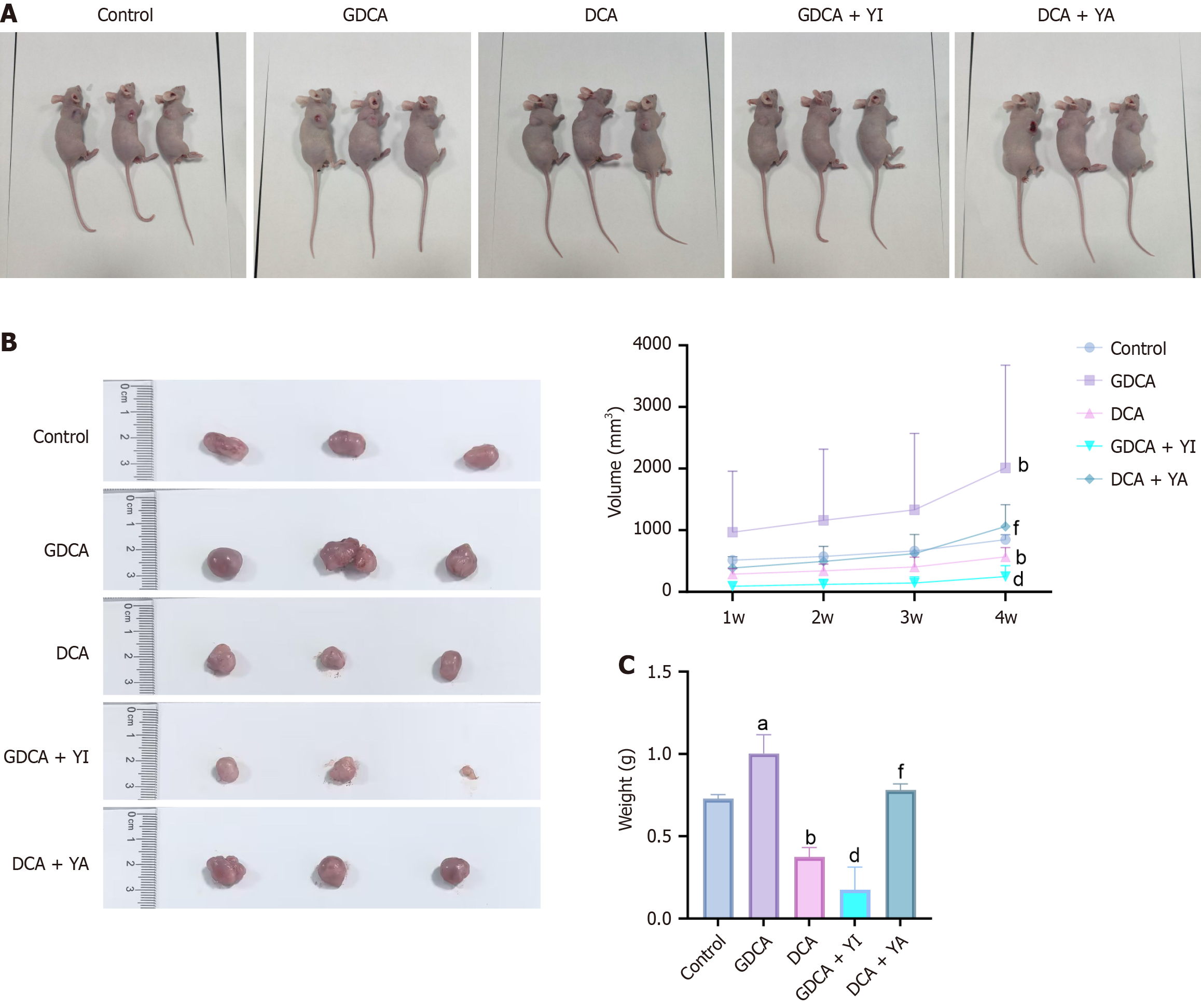

The animal model and cell culture experiments were divided into five groups, each following a consistent treatment scheme. When tumor volumes reached 100 mm3, mice were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 6, per group) and treated as follows every three days for four weeks. The control group received no active treatment: Mice were injected with PBS, and cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium without any additional agents. The GDCA group involved peritumoral injections of 200 μM GDCA for mice, while cells were treated with 200 μM GDCA in culture. Similarly, the DCA group received 100 μM DCA injections in mice and 100 μM DCA treatment in vitro. The GDCA + YI group combined 200 μM GDCA with 0.5 μM verteporfin, administered to mice via peritumoral injections and added to cell cultures under the same concentrations. Finally, the DCA + YA group was treated with 100 μM DCA combined with 0.5 μM GA-017, applied identically to both in vivo and in vitro models. This standardized grouping facilitated a direct comparison of the effects of these treatments across experimental settings.

The tumor growth in the control, GDCA, DCA, GDCA + YI, and DCA + YA groups was monitored weekly by measuring the length and width of the tumors using a caliper. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Volume = (length × width2)/2. At the end of the treatment period, tumors were carefully excised from the mice, and photographs of the tumors were taken for documentation. The excised tumors were then weighed to compare tumor masses across the different treatment groups. These measurements provided quantitative data for evaluating the effects of GDCA, DCA, and YAP modulators on tumor progression in the in vivo model.

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Guangzhou Yujia Biotechnology Co., Ltd., C0037, China) assay. HuCCT1 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 5 × 103 cells/well and treated for 24 hours. After treatment, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader, and cell viability was calculated relative to the control. Each condition was tested in triplicate.

DNA replication ability was assessed using a 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assay kit (ST067-50 mg; Guangzhou Yujia Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China). HuCCT1 cells were treated for 24 hours, then incubated with EdU reagent (final concentration: 10 μM) for 2 hours at 37 °C. Following incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100. The incorporated EdU was detected using a click chemistry reaction according to the manufacturer's instructions, and nuclei were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope, and the percentage of EdU-positive cells was calculated relative to the total number of nuclei. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Apoptosis levels were assessed using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate-nick end labelling (TUNEL) assay kit (C1086; Guangzhou Yujia Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. HuCCT1 cells were treated for 24 hours, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 minutes. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes at 4 °C. After washing, cells were incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme and labeled deoxyuridine triphosphate pyrophosphatase for 60 minutes at 37 °C in a humidified chamber. Nuclei were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole to visualize all cells. Fluorescence images were captured using a fluorescence microscope, and the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells (apoptotic cells) was calculated relative to the total number of nuclei. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cell migration and invasion were assessed using Transwell chambers with 8-μm pore size inserts, with or without Matrigel coating for invasion and migration assays, respectively. Serum-starved HuCCT1 cells were resuspended in serum-free medium and seeded into the upper chamber, while the lower chamber contained medium with 10% fetal bovine serum as a chemoattractant. After 24 hours at 37 °C, non-migrated or non-invaded cells on the upper surface of the membrane were removed, and cells on the lower surface were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with crystal violet, and counted under a microscope. Results were averaged from three random fields, and all experiments were performed in triplicate.

To detect the mRNA expression level of YAP, TRIzol reagent (R0016; Guangzhou Yujia Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) was used to extract total RNA from cancer tissues, normal tissues and A549 cells of lung cancer patients. The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA were detected by ultraviolet spectrophotometer (840-317400; ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, United States), and the RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (SO131; ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, United States). The reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction reaction was performed using the SYBR Green kit (D7268S; Guangzhou Yujia Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China). The reaction conditions were 95 °C for 10 minutes of pre-denaturation, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C denaturation for 30 seconds, 60 °C annealing for 30 seconds, and 72 °C extension for 30 seconds. U6 was used as the internal reference gene, and the relative expression was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method. Three technical replicates were set for each sample (Table 1).

| Forward primer (5’-3’) | Reverse primer (5’-3’) | |

| YAP | ATGGGGAAAGGTAGCAAGCC | GAGACAAGGAGTGGGTGAGC |

| U6 | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA | AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

Total protein was extracted from cells of treatment groups using radio immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (L00399; Guangzhou Yujia Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China), and protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay method. The 30 μg protein per well was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (IPVH00010; Millipore, MA, United States). After blocking with 5% skim milk powder at room temperature for 1 hour, MST1 antibody (ab51134; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), phosphorylated-MST1 antibody (ab76323; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), LATS1 antibody (ab243656; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), phosphorylated-LATS1 antibody (ab305029; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), YAP antibody (ab205270; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), phosphorylated-YAP antibody (ab76252; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), caspase-3 antibody (ab184787; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) antibody (ab182858; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), Bcl-2 associated X protein (Bax) antibody (ab32503; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) were added and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody was added, and the protein bands were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence colorimetric reagent (32106; ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, United States) after incubation at room temperature for 1 hour. The β-actin was used as an internal reference for relative protein expression analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 software. All results are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for comparisons among multiple groups. For tumor growth curves, two-way repeated measures ANOVA was applied. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were generated, and all statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism to ensure accuracy and consistency in data presentation.

Western blot analysis (Figure 1A) showed that GDCA reduced MST1, LATS1, and YAP phosphorylation while slightly elevating total YAP, whereas DCA had the opposite effect. The YAP inhibitor (GDCA + YI) restored MST1/LATS1 phosphorylation and increased YAP phosphorylation while lowering its total protein, while the YAP agonist (DCA + YA) decreased MST1/LATS1 and YAP phosphorylation with a modest increase in total YAP. Consistently, reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (Figure 1B) revealed GDCA upregulated YAP mRNA, whereas DCA slightly suppressed it. GDCA + YI reduced YAP mRNA compared to GDCA alone, while DCA + YA enhanced it relative to DCA alone.

Cell proliferation was assessed using CCK-8 and EdU assays. CCK-8 results (Figure 2A) showed that GDCA significantly increased cell viability, while DCA reduced it (P < 0.05). YAP inhibition attenuated GDCA’s effect, whereas YAP activation reversed DCA’s suppression. Consistently, EdU staining (Figure 2B) demonstrated enhanced DNA replication with GDCA and reduced replication with DCA (P < 0.05), effects that were mitigated by YAP modulation. Together, these results indicate that GDCA promotes, while DCA inhibits, CCA cell proliferation.

The Transwell assays (Figure 3A and B) revealed that GDCA significantly enhanced cell migration and invasion compared to the control group (P < 0.05), whereas DCA markedly suppressed these abilities (P < 0.05). GDCA + YI treatment reduced migration and invasion compared to GDCA alone (P < 0.05), while DCA + YA treatment enhanced these abilities compared to DCA alone (P < 0.05). These findings demonstrate that GDCA promotes CCA cell aggressiveness through enhanced migration and invasion, whereas DCA exerts a suppressive effect, highlighting their opposing roles in metastatic regulation.

The TUNEL assays (Figure 4A) showed that GDCA treatment significantly reduced the proportion of TUNEL-positive cells compared to the control group (P < 0.05), with decreased green fluorescence and intact nuclear morphology, indicating suppressed apoptosis. In contrast, DCA significantly increased TUNEL-positive cells (P < 0.05), with enhanced green fluorescence and evident nuclear fragmentation. Western blot analysis supported these findings (Figure 4B), showing that GDCA decreased the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and caspase-3 while increasing the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (P < 0.05). Conversely, DCA elevated Bax and caspase-3 levels and reduced Bcl-2 expression (P < 0.05).

The in vivo analysis demonstrated (Figure 5) that GDCA significantly increased tumor volume and weight compared to the control group (P < 0.05), while DCA significantly reduced both parameters (P < 0.05). GDCA + YI treatment suppressed tumor growth, with a significant reduction in both tumor volume and weight compared to GDCA alone (P < 0.05). Conversely, DCA + YA treatment promoted tumor progression, leading to a significant increase in tumor volume and weight compared to DCA alone (P < 0.05).

This study systematically explored the distinct roles of GDCA and DCA in CCA progression through the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway. Our findings revealed that GDCA promotes CCA progression by inhibiting MST1 and LATS1 phosphorylation, thereby activating YAP and enhancing proliferation, migration, and invasion while suppressing apoptosis. Conversely, DCA exerted tumor-suppressive effects by enhancing MST1 and LATS1 phosphorylation and inhibiting YAP activation. The effects of GDCA and DCA were further validated using YAP modulators, confirming the pivotal role of Hippo-YAP signaling in bile acid-induced tumor progression.

The roles of bile acids in cancer progression have been widely studied, with GDCA and DCA identified as key modulators of tumor biology. Previous studies demonstrated that GDCA promotes tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma by activating oncogenic pathways, including YAP signaling[25]. Our results are consistent with these findings, showing that GDCA enhances YAP activation in CCA and correlates with increased tumor cell proliferation and aggressiveness. In contrast, although DCA shows context-dependent effects in other cancers, our data indicate that it exerts tumor-suppressive functions in CCA by enhancing MST1 and LATS1 phosphorylation, leading to YAP inactivation[26].

A major contribution of this study is the first systematic elucidation of how distinct bile acids differentially regulate Hippo-YAP signaling. While previous reports mainly focused on general bile acid effects on cancer cells[27], our findings provide direct evidence that GDCA and DCA modulate YAP signaling in opposite directions. These results highlight Hippo-YAP as a therapeutic target for CCA and demonstrate that YAP modulators can effectively counteract the effects of bile acids. Moreover, bile acids are known to influence tumor immunity and metabolic reprogramming, thereby shaping the tumor microenvironment[28]. For instance, bile acids modified by intestinal microbiota promote colorectal cancer growth by suppressing cluster of differentiation 8+ T cell effector functions[28]. Emerging evidence also shows that bile acids regulate YAP activity to promote liver carcinogenesis[22], supporting YAP as a downstream effector of bile acid-mediated oncogenic signaling in multiple cancers[29]. By integrating these insights, our study strengthens the mechanistic link between bile acids and Hippo-YAP signaling in CCA.

The divergent roles of GDCA and DCA may also be attributed to their effects on oncogenic and immune pathways. GDCA has been reported to activate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and enhance stemness and chemoresistance in liver cancer cells, suggesting possible synergy with YAP in sustaining tumor growth and survival[30]. By contrast, DCA can regulate microRNA-dependent gene expression, promote apoptosis, and reduce drug resistance in colorectal cancer, implying a tumor-suppressive role in CCA. Additionally, bile acids can remodel the tumor microenvironment via receptors such as G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1, activating fibroblasts and shaping immunosuppressive niches[31]. These findings support the view that GDCA amplifies proliferative and anti-apoptotic programs, whereas DCA reinforces apoptotic and immune-protective mechanisms. Future studies should validate these differences in patient-derived CCA models and evaluate whether combining YAP inhibitors with bile acid modulators or immunotherapy could yield synergistic therapeutic benefits. Bile acids have been reported to regulate other signaling cascades, such as Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB, contributing to tumor progression and metastasis[32]. However, this study uniquely identifies the Hippo-YAP pathway as a central mediator of bile acid-driven tumor dynamics in CCA. The differential modulation of YAP activity by GDCA and DCA represents a novel finding that bridges the gap between bile acid signaling and tumor biology.

This study has several limitations. First, only one CCA cell line (HuCCT1) and one animal model were used. HuCCT1 was selected because it is a well-characterized and widely applied intrahepatic CCA line with stable features for mechanistic studies, but reliance on a single line limits generalizability given the heterogeneity of CCA. Second, we focused only on GDCA and DCA, while other bile acids may also affect Hippo-YAP signaling. Third, potential interactions with pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, NF-κB, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B were not explored. Finally, the findings are based on preclinical models and require validation in additional cell lines, organoids, and clinical samples. In addition, although apoptosis was evaluated using TUNEL staining and apoptosis-related proteins, more comprehensive approaches such as flow cytometry-based Annexin V/PI assays or additional apoptotic markers (e.g., cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase) were not performed in this study. Future work incorporating these methods will provide more rigorous validation of our findings.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide a foundation for developing personalized therapeutic strategies based on bile acid profiles and Hippo-YAP activity. Future work should validate these mechanisms in clinical samples and assess the efficacy of YAP inhibitors (e.g., verteporfin) and bile acid metabolism modulators in preclinical and clinical settings, alone or in combination with chemotherapy or immunotherapy. The absence of validation in other CCA cell lines, such as HCCC9810 and RBE, remains a limitation; future studies will incorporate additional lines and patient-derived models to further confirm reproducibility. Expanding research to other bile acids and oncogenic pathways, and considering the gut-liver axis in bile acid composition, could yield a more comprehensive understanding of tumor biology and reveal innovative strategies, such as probiotics or dietary interventions, for CCA management. A schematic diagram summarizing the differential effects of GDCA and DCA on CCA progression through Hippo-YAP signaling is shown in Figure 6.

This study highlights the pivotal role of the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway in mediating the opposing effects of GDCA and DCA on CCA progression. By uncovering the molecular mechanisms through which bile acids influence tumor behavior, it underscores the importance of targeting bile acid metabolism and YAP signaling for developing personalized therapeutic strategies. These findings not only provide new insights into the interplay between bile acids and oncogenic pathways but also open avenues for innovative treatments aimed at improving outcomes for patients with CCA.

| 1. | Khan AS, Dageforde LA. Cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99:315-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gad MM, Saad AM, Faisaluddin M, Gaman MA, Ruhban IA, Jazieh KA, Al-Husseini MJ, Simons-Linares CR, Sonbol MB, Estfan BN. Epidemiology of Cholangiocarcinoma; United States Incidence and Mortality Trends. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:885-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jusakul A, Cutcutache I, Yong CH, Lim JQ, Huang MN, Padmanabhan N, Nellore V, Kongpetch S, Ng AWT, Ng LM, Choo SP, Myint SS, Thanan R, Nagarajan S, Lim WK, Ng CCY, Boot A, Liu M, Ong CK, Rajasegaran V, Lie S, Lim AST, Lim TH, Tan J, Loh JL, McPherson JR, Khuntikeo N, Bhudhisawasdi V, Yongvanit P, Wongkham S, Totoki Y, Nakamura H, Arai Y, Yamasaki S, Chow PK, Chung AYF, Ooi LLPJ, Lim KH, Dima S, Duda DG, Popescu I, Broet P, Hsieh SY, Yu MC, Scarpa A, Lai J, Luo DX, Carvalho AL, Vettore AL, Rhee H, Park YN, Alexandrov LB, Gordân R, Rozen SG, Shibata T, Pairojkul C, Teh BT, Tan P. Whole-Genome and Epigenomic Landscapes of Etiologically Distinct Subtypes of Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1116-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 724] [Article Influence: 80.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tham EKJ, Lim RY, Koh B, Tan DJH, Ng CH, Law M, Cho E, Tang NSY, Tan CS, Sim BKL, Tan EY, Lim WH, Lim MC, Nakamura T, Danpanichkul P, Chirapongsathorn S, Wijarnpreecha K, Takahashi H, Morishita A, Zheng MH, Kow A, Muthiah M, Law JH, Huang DQ. Prevalence of Chronic Liver Disease in Cholangiocarcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23:1710-1718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fiz F, Rossi N, Langella S, Conci S, Serenari M, Ardito F, Cucchetti A, Gallo T, Zamboni GA, Mosconi C, Boldrini L, Mirarchi M, Cirillo S, Ruzzenente A, Pecorella I, Russolillo N, Borzi M, Vara G, Mele C, Ercolani G, Giuliante F, Cescon M, Guglielmi A, Ferrero A, Sollini M, Chiti A, Torzilli G, Ieva F, Viganò L. Radiomics of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Peritumoral Tissue Predicts Postoperative Survival: Development of a CT-Based Clinical-Radiomic Model. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:5604-5614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moungthard H, Thinkhamrop K, Titapun A, Thinkhamrop B, Kelly M. Survival after Surgery among Cholangiocarcinoma Patients Comparing between Mucin Producing and Non-Mucin Producing. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2024;25:2139-2145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu H, Sun M, Wu N, Liu B, Liu Q, Fan X. TGF-β/Smads signaling pathway, Hippo-YAP/TAZ signaling pathway, and VEGF: Their mechanisms and roles in vascular remodeling related diseases. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023;11:e1060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bao XM, He Q, Wang Y, Huang ZH, Yuan ZQ. The roles and mechanisms of the Hippo/YAP signaling pathway in the nervous system. Yi Chuan. 2017;39:630-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jung J, Kim JW, Kim G, Kim JY. Low MST1/2 and negative LATS1/2 expressions are associated with poor prognosis of colorectal cancers. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;248:154608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yuan B, Liu J, Shi A, Cao J, Yu Y, Zhu Y, Zhang C, Qiu Y, Luo H, Shi J, Cao X, Xu P, Shen L, Liang T, Zhao B, Feng XH. HERC3 promotes YAP/TAZ stability and tumorigenesis independently of its ubiquitin ligase activity. EMBO J. 2023;42:e111549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ji XY, Zhong G, Zhao B. Molecular mechanisms of the mammalian Hippo signaling pathway. Yi Chuan. 2017;39:546-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang J, Park JS, Wei Y, Rajurkar M, Cotton JL, Fan Q, Lewis BC, Ji H, Mao J. TRIB2 acts downstream of Wnt/TCF in liver cancer cells to regulate YAP and C/EBPα function. Mol Cell. 2013;51:211-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Das PK, Islam F, Lam AK. The Roles of Cancer Stem Cells and Therapy Resistance in Colorectal Carcinoma. Cells. 2020;9:1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qian M, Yan F, Wang W, Du J, Yuan T, Wu R, Zhao C, Wang J, Lu J, Zhang B, Lin N, Dong X, Dai X, Dong X, Yang B, Zhu H, He Q. Deubiquitinase JOSD2 stabilizes YAP/TAZ to promote cholangiocarcinoma progression. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:4008-4019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang H, Xu H, Zhang C, Tang Q, Bi F. Ursodeoxycholic acid suppresses the malignant progression of colorectal cancer through TGR5-YAP axis. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Omer E, Chiodi C. Fat digestion and absorption: Normal physiology and pathophysiology of malabsorption, including diagnostic testing. Nutr Clin Pract. 2024;39 Suppl 1:S6-S16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shi C, Yang J, Hu L, Liao B, Qiao L, Shen W, Xie F, Zhu G. Glycochenodeoxycholic acid induces stemness and chemoresistance via the STAT3 signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:15546-15555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Farina GA, Cherubini K, de Figueiredo MAZ, Salum FG. Deoxycholic acid in the submental fat reduction: A review of properties, adverse effects, and complications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:2497-2504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu FX, Zhao B, Guan KL. Hippo Pathway in Organ Size Control, Tissue Homeostasis, and Cancer. Cell. 2015;163:811-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1241] [Cited by in RCA: 1793] [Article Influence: 179.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Meacci D, Bruni A, Cocquio A, Dell'Anna G, Mandarino FV, Marasco G, Cecinato P, Barbara G, Zagari RM. Microbial Landscapes of the Gut-Biliary Axis: Implications for Benign and Malignant Biliary Tract Diseases. Microorganisms. 2025;13:1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bai H, Zhang N, Xu Y, Chen Q, Khan M, Potter JJ, Nayar SK, Cornish T, Alpini G, Bronk S, Pan D, Anders RA. Yes-associated protein regulates the hepatic response after bile duct ligation. Hepatology. 2012;56:1097-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Anakk S, Bhosale M, Schmidt VA, Johnson RL, Finegold MJ, Moore DD. Bile acids activate YAP to promote liver carcinogenesis. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1060-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jin D, Guo J, Wu Y, Yang L, Wang X, Du J, Dai J, Chen W, Gong K, Miao S, Li X, Sun H. m(6)A demethylase ALKBH5 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by reducing YTHDFs-mediated YAP expression and inhibiting miR-107/LATS2-mediated YAP activity in NSCLC. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | LaRusso NF, Szczepanik PA, Hofmann AF. Effect of deoxycholic acid ingestion on bile acid metabolism and biliary lipid secretion in normal subjects. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:132-140. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Cai J, Chen T, Jiang Z, Yan J, Ye Z, Ruan Y, Tao L, Shen Z, Liang X, Wang Y, Xu J, Cai X. Bulk and single-cell transcriptome profiling reveal extracellular matrix mechanical regulation of lipid metabolism reprograming through YAP/TEAD4/ACADL axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:2114-2131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kong Y, Bai PS, Sun H, Nan KJ, Chen NZ, Qi XG. The deoxycholic acid targets miRNA-dependent CAC1 gene expression in multidrug resistance of human colorectal cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:2321-2332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cong J, Liu P, Han Z, Ying W, Li C, Yang Y, Wang S, Yang J, Cao F, Shen J, Zeng Y, Bai Y, Zhou C, Ye L, Zhou R, Guo C, Cang C, Kasper DL, Song X, Dai L, Sun L, Pan W, Zhu S. Bile acids modified by the intestinal microbiota promote colorectal cancer growth by suppressing CD8(+) T cell effector functions. Immunity. 2024;57:876-889.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 81.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jia W, Xie G, Jia W. Bile acid-microbiota crosstalk in gastrointestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:111-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1355] [Cited by in RCA: 1396] [Article Influence: 174.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Patel SH, Camargo FD, Yimlamai D. Hippo Signaling in the Liver Regulates Organ Size, Cell Fate, and Carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:533-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Deng M, Liu J, Zhang L, Lou Y, Qiu Y. Identification of molecular subtypes based on bile acid metabolism in cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Huang F, Liu Z, Song Y, Wang G, Shi A, Chen T, Huang S, Lian S, Li K, Tang Y, Zheng L, Sheng G, Zhang N, Yang F, Pan C, Jing W, Zhang Z, Xu Y. Bile acids activate cancer-associated fibroblasts and induce an immunosuppressive microenvironment in cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2025;43:1460-1475.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Abdulaal WH, Omar UM, Zeyadi M, El-Agamy DS, Alhakamy NA, Ibrahim SRM, Almalki NAR, Asfour HZ, Al-Rabia MW, Mohamed GA, Elshal M. Pirfenidone ameliorates ANIT-induced cholestatic liver injury via modulation of FXR, NF-кB/TNF-α, and Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathways. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2024;490:117038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/