Published online Oct 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i10.109744

Revised: July 7, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: October 15, 2025

Processing time: 147 Days and 4.8 Hours

MicroRNAs play an important role in gastric cancer (GC) development following Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. Yet the exact mechanism is still not fully understood. Herein, we investigated the underlying mechanisms of miR-136 during this process.

To investigate the role of miR-136 in H. pylori-induced GC progression.

GC and gastric epithelial cells were infected with H. pylori and transfected with miR-136 mimic, inhibitor, mimic plus PDCD11 (identified as miR-136 target), or miR-NC (control). Cell proliferation, migration, and invasion were assessed via cell counting kit-8 assay, colony formation, wound healing, and Transwell assays. Nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB)/miR-136/PDCD11 interactions were confirmed by luciferase and inhibition assays. For in vivo studies H. pylori-infected BGC-823 cells were injected into nude mice. Reverse transcription PCR, western blot, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescent staining assay were used to assess mRNA and protein expression.

miR-136 expression was significantly upregulated while PDCD11 expression was significantly downregulated in early GC tissues and GC cells infected with H. pylori compared with non-infected tissues or cells (all P < 0.01). miR-136 overexpression induced by H. pylori could promote the proliferation and migration of infected GC cells and induce the growth of H. pylori-positive GC tumors in mice while its inhibition could reverse this effect. Mechanistically, upregulation of miR-136 suppressed PDCD11 through NF-κB activation induced by H. pylori infection.

miR-136 is a novel diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target in H. pylori-associated early-stage gastric carcinogenesis and acts through the NF-κB-miR-136-PDCD11 pathway.

Core Tip: Helicobacter pylori infection upregulates miR-136, promoting gastric cancer progression by suppressing PDCD11 via nuclear factor kappa-B activation. This study identified miR-136 as a potential diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for early-stage gastric cancer, demonstrating its role in tumor growth and metastasis through in vitro and in vivo models. Targeting the nuclear factor kappa-B/miR-136/PDCD11 axis may offer new strategies for intervention.

- Citation: Chen T, Feng AQ, Shen XR, Dang NY, Ye F, Zhang GX. Helicobacter pylori-induced miR-136 is a potential predictor of early-stage gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(10): 109744

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i10/109744.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i10.109744

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second-leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, over a million new GC cases are reported yearly[1]. Surgery remains the most effective treatment for patients with early-stage GC. However, most patients present with an advanced tumor at the time of diagnosis, thus losing their chance to undergo surgery. These patients require more invasive therapy, which often includes radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The median survival rate for patients with advanced-stage GC is < 12 months, including patients receiving curative resection while the 5-year survival rate is < 10%[2,3]. Therefore, early diagnosis is crucial for improving prognosis.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has been associated with an increased risk of developing various gastric pathologies, including GC. For example Mera et al[4] assessed 795 adults with precancerous gastric lesions in a 16-year follow-up study and discovered that long-term exposure to H. pylori infection is associated with the progression of precancerous lesions. They also found that these patients, particularly those with atrophic gastritis, may benefit from eradication therapy. Therefore, eliminating H. pylori has been suggested as an efficient approach for reducing the prevalence of GC[5,6].

However, a long-term follow-up study performed in Japan suggested that the risk of the development of GC remains high even if H. pylori is successfully eradicated due to the genetic and epigenetic alterations and irreversible lesions, including severe atrophic and intestinal metaplasia (IM) of gastric mucosa induced by chronic inflammation after H. pylori infection[7]. Therefore, the molecular mechanism of the stepwise progression from gastric inflammation to cancer after H. pylori infection should be further explored.

Studies suggested that dysregulation of the signaling pathway and abnormal expression of oncogenes induced by H. pylori infection could be involved in the progression of GC[8,9]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs that may lead to mRNA degradation through binding to the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of mRNA. miRNAs have multiple functions and participate in tumorigenesis, including GC[10-12]. Zheng et al[13] found that miR-136 inhibits GC-specific peritoneal metastasis by targeting HOXC10. In addition Yu et al[14] reported that miR-136 triggered apoptosis in human GC cells by targeting AEG-1 and BCL2. Moreover, Chen et al[15] discovered that miR-136 promoted the invasion and proliferation of GC cells through the PTEN/AKT/P-Akt pathway. However, the exact mechanism is still not fully understood.

In this study we investigated the role of miR-136 expression in GC tissues and cells infected with H. pylori. The underlying mechanisms of miR-136 responsible for gastric carcinogenesis induced by H. pylori infection were also investigated.

All tissues were collected from patients treated at Xuzhou Central Hospital between 2019 and 2020. The clinical assessment was divided into four groups. First, we collected 30 matched pairs of H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative GC tissues from patients undergoing gastrectomy. The H. pylori-negative status was validated through a dual confirmation criterion: (1) Retrospective evaluation of medical records to exclude patients with documented H. pylori infection or eradication therapy; and (2) Current diagnostic confirmation via histopathological examination and serological testing at the time of GC diagnosis. The GC tissues included 39 tubular-type adenocarcinoma specimens, 15 papillary adenocarcinoma specimens, and 6 mixed adenocarcinomas. In addition H. pylori-negative tissues with inactive gastritis (NAG; n = 30) and H. pylori-positive tissues with chronic gastritis (CAG; n = 30) and precursor lesions of GC (PLGC; n = 30), including IM and gastric atrophy (GA), were collected by gastroscopy. The gastric mucosal histopathological characteristics, including atrophy and IM patterns, were systematically assessed following the Operationally Defined Staging Criteria for Gastritis (OLGA) and Operative Link for Gastritis Intestinal Metaplasia (OLGIM) systems to stratify premalignant risk[16].

Inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosed for the first time; (2) Not received any previous treatments; and (3) Confirmed by pathological examination.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Previous eradication treatment of H. pylori; (2) Use of proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics, or H2-receptor blockers; or (3) Intake of drugs influencing the level of folic acid.

The characteristics of these cases were summarized in Table 1. H. pylori infection was identified by a rapid urease test, H. pylori antibody, and histology. The study was reviewed and approved by the Xuzhou Central Hospital Ethics Committee (Approval No. XZXY-LJ-20180627-004). All patients signed the informed consent form.

| Characteristics | Gastric cancer (n = 60) | Gastritis (n = 90) | P value | ||

| NAG | CAG | PLGC | |||

| Age, years | 0.097 | ||||

| 18-45 | 16 (27) | 16 (18) | 11 (12) | 12 (13) | |

| > 45 | 44 (73) | 14 (16) | 19 (21) | 18 (20) | |

| Sex | 0.244 | ||||

| Male | 42 (70) | 16 (18) | 21 (23) | 23 (25) | |

| Female | 18 (30) | 14 (16) | 9 (10) | 7 (8) | |

| H. pylori | < 0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 30 (50) | 30 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Positive | 30 (50) | 0 (0) | 30 (33) | 30 (33) | |

| Smoking | 0.965 | ||||

| Yes | 34 (57) | 18 (20) | 16 (18) | 17 (19) | |

| No | 26 (43) | 12 (13) | 14 (16) | 13 (14) | |

| Drinking | 0.881 | ||||

| Yes | 37 (62) | 19 (22) | 17 (19) | 20 (22) | |

| No | 23 (38) | 11 (12) | 13 (14) | 10 (11) | |

| Family history | 0.569 | ||||

| Yes | 36 (60) | 14 (16) | 17 (19) | 19 (21) | |

| No | 24 (40) | 16 (18) | 13 (14) | 11 (12) | |

| OLGA | < 0.001 | ||||

| I | 0 (0) | 23 (26) | 17 (19) | 1 (1) | |

| II | 1 (2) | 6 (7) | 11 (12) | 5 (6) | |

| III | 27 (45) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 13 (14) | |

| IV | 32 (53) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (12) | |

| OLGIM | < 0.001 | ||||

| I | 0 (0) | 17 (19) | 11 (12) | 0 (0) | |

| II | 2 (3) | 12 (13) | 15 (17) | 3 (3) | |

| III | 28 (47) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 11 (13) | |

| IV | 30 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (18) | |

The Target Scan version 7.1 was used to obtain the predicted mRNA targets for each differential expression of miRNA. PDCD11 was identified as the target gene of miR-136.

GC cell lines (SGC-7901 and BGC-823) and gastric epithelial cells (GES-1) were purchased from Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma, United States), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma, United States). Cells were kept in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. After reaching 70% confluence, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, United States), following the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection reverse transcription (RT) quantitative PCR (qPCR) was used to assess transfection efficiency. miR-136 mimic, miR-136 inhibitor, and miR-NC (control) were purchased from Genepharma company (Shanghai, China). PCDNA3.1-PDCD11 was synthesized by Gima Company (Shanghai, China), and the control plasmid was purchased from Promega. The sequences of the primers are shown in Table 2.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5’-3’) | |

| miR-136 | Forward | ACACTCCAGCTGGGACTCCATTTGTTTTG |

| Reverse | CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATCAGTTGAGTCCATCAT | |

| U6 | Forward | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

| Reverse | AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT | |

| PDCD11 | Forward | GAAGCTACCATGGTTGCAACAGTACAGG |

| Reverse | CCTGTACTGTGAATTCGATGGTAGCTTCC | |

| GAPDH | Forward | GAGGGATTTTTGTTTTTATGTTTTG |

| Reverse | TATATACACCAACAACTCTCTCCAA | |

| miR-136 mimics | Forward | ACUCCAUUUGUUUUGAUGAUGGA |

| Reverse | UCCAUCAUCAAAACAAAUGGAGU | |

| miR-NC | Forward | UUUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG |

| Reverse | CAGUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAAA | |

| miR-136 inhibitor | UCCAUCAUCAAAACAAAUGGAGU | |

| NF-κB WT | GGGGCAACGGCAGGGGAATTCCCCTCTCCTTA | |

| NF-κB Mut | GGGGCAACGGCAGATCTATTCCCCTCTCCTTA | |

H. pylori standard strain (26695) was purchased from ATCC. H. pylori were seeded on Columbia agar plates under a microaerophilic condition at 37 °C. After growing bacteria for 72 h, cells were harvested, and the bacterial density was measured with the optical density at 660 nm. SGC-7901, BGC-823, and GES-1 cells were harvested and then transferred to the antibiotic-free RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 2% FBS after which they were infected with the bacteria at a cell-to-bacterium ratio of 1:100 for 24 h. To confirm successful H. pylori infection of gastric epithelial and cancer cells, we employed a qPCR-based approach targeting the ureA gene, a well-characterized marker for H. pylori. Genomic DNA was extracted from cells 24 h post-infection, and amplification was performed using specific primers designed for ureA (forward: 5’-CAGCGGATAAGGTTATCGTC-3’, reverse: 5’-GCTTCACCTTGCTCTTGCTA-3’). Infection was considered successful if the qPCR met all of the following criteria: (1) A cycle threshold (Ct) value ≤ 35 with a typical S-shaped amplification curve and a single-peak melting curve, indicating specific target amplification; (2) A ≥ 2-fold increase in ureA expression relative to uninfected controls, calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method using GAPDH as the internal reference gene (forward: 5’-GGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT-3’; reverse: 5’-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3’) with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05); and (3) In absolute quantification assays a copy number of ureA exceeding 103 copies/μg of cellular DNA based on a standard curve generated from known concentrations of H. pylori plasmid DNA. This combination of qualitative and quantitative assessments ensured accurate evaluation of infection efficiency in the in vitro model.

Male BALB/c nude mice, 5-weeks-old, were provided by the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China). All the animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment with a temperature of 22 ± 1 °C, relative humidity of 50% ± 1%, and a light/dark cycle of 12/12 hours. All animal studies (including the mice euthanasia procedure) were done in compliance with the regulations and guidelines of Xuzhou Central Hospital institutional animal care and conducted according to the AAALAC and the IACUC guidelines (Ministry of Science and Technology of China, 2006). The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Xuzhou Central Hospital Animal Ethics Committee (approval No. XZYKDX-20200721-005).

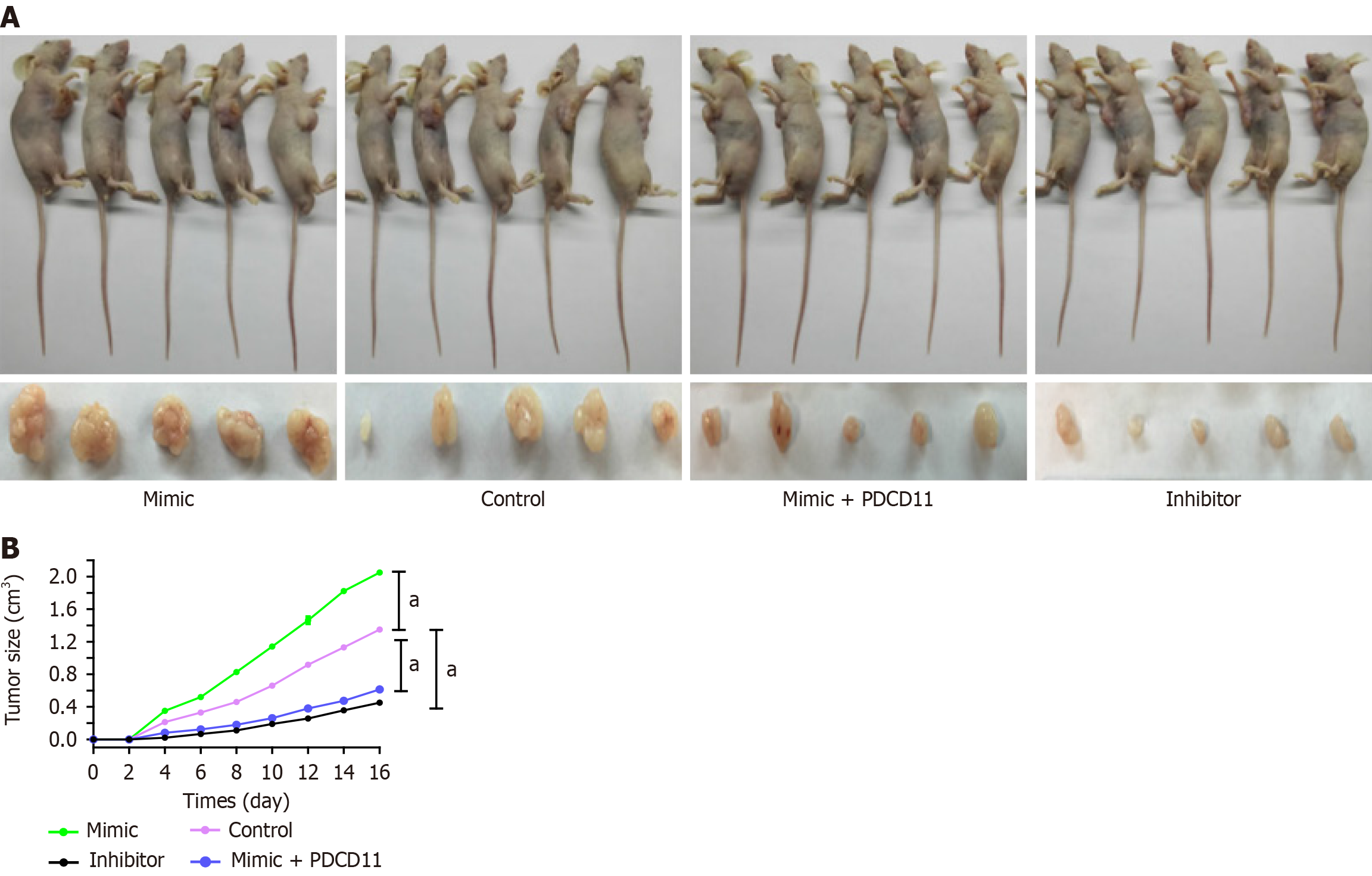

Mice were randomly divided into four groups (5 mice per group): MiR-136 mimic group; miR-136 inhibitor group; miR-NC group; and miR-136 mimic plus PDCD11 group. The miR-136 mimic group was injected with BGC-823 GC cells infected with H. pylori and transfected with miR-136 mimic. The miR-136 inhibitor group was injected with BGC-823 GC cells infected with H. pylori and transfected with miR-136 inhibitor. The miR-NC group was injected with BGC-823 GC cells infected with H. pylori and transfected with miR-NC. The miR-136 mimic plus PDCD11 group was injected with miR-136 mimic plus PDCD11. All cells were suspended in PBS (1 × 107 cells suspended with 0.2 mL PBS) were injected subcutaneously in the right flank of the nude mouse. Tumor growth was monitored every 2 days with a standard caliper for 16 days. Tumor size was calculated using the formula: Length × width2 × 0.5. After 16 days these mice were sacrificed using cervical dislocation.

RNA was extracted from tissues and cells with TRIzol Reagent (Sigma, United States) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation with minor modifications. Reverse transcription was performed using the Reverse Transcription Kit (TakaRa, United States). qPCR was carried out with the SYBR Green Master Mix kit (ABI, United States) on the StepOne Real-Time PCR System (ABI, United States). Relative expression of miR-136 and PDCD11 mRNA was measured using the comparative Ct (2−∆∆Ct) method. U6 and GAPDH were used as internal references. The sequences of the primers are presented in Table 2. All samples were assayed in duplicate, and all experiments were performed in triplicate.

Protein was extracted from tissues and cells and then analyzed. The antibodies used for the experiments were purchased from Bioworld Technology (United States) as follows: Polyclonal rabbit anti-PDCD11 and mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibodies. The relative expression level of PDCD11 was normalized against GAPDH, and the experiment was repeated three times.

After deparaffinized with graded xylene, tissues were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min, immersed in 10 mmol/citrate buffer (pH 6.0), and subsequently incubated with 10% goat serum. This was followed by the incubation with the primary rabbit polyclonal antibody against PDCD11 (1:400) at 4 °C overnight and then goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:50) at 37 °C for 30 min. After being washed three times, the glass slides were stained with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride solution and evaluated by standard light microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Cells were grown on coverslips in 6-well plates overnight, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and subsequently immersed in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. This was followed by incubation with the primary rabbit polyclonal antibody against PDCD11 (1:500) at 4 °C overnight and then goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:50) for 30 min. After being washed three times, the glass slides were stained with DAPI (1:2000) for 5 min and then observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

After transfection cells were cultured in 6-well plates and incubated for 14 days. A proper medium containing 10% FBS was replaced every 4 days. After 14 days the cells were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Sigma). Stained colonies were then counted. Every group was treated in triplicate wells, and experiments were repeated three times.

Cell proliferation was evaluated using a cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) solution (Beyotime, China), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells cultured on 96-well plates were harvested at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h after transfection and treated at a concentration of 4 × 103 cells/well in triplicate. After 4 h of preincubation, 100 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and consecutively incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2, for another 4 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was determined using a microplate reader (Promega, United States).

The bottom of the upper chamber was coated with a 50 mg/L Matrigel (1:8 dilution) at 4 °C. Then 4 × 103 transfected cells (transfected for 24 h) were placed in the upper chamber with serum-free culture medium, and 500 μL of 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. Twenty-four hours later the remaining cells in the upper chamber were cleaned with a sterile cotton swab while cells in the lower chambers were stained with 0.1% crystal violet and counted with an inverted fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Cells (5 × 105) were seeded and incubated in a 12-well plate at 37 °C. When the cells were 80% confluent, the floating cells were washed away using PBS. After scratching the cell layer, the transfected cells were cultured again for 24 h. A digital camera system was used to take cell images. The gap closure was measured.

Luciferase reporter vectors, including miR-136 promoter vector containing nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) binding site and mutated binding site (Mut), pGL3-PDCD11-3’-UTR wild-type (WT) and Mut, were synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma. The sequences of the primers are presented in Table 2. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates for 24 h before transfection after which they were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Forty-eight hours after transfection luciferase activities were analyzed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, United States).

Data were shown as mean ± SD and analyzed with SPSS 22.0 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, United States). Student’s t-test and analysis of variance were used to analyze the difference between groups. P value < 0.01 represented statistical significance.

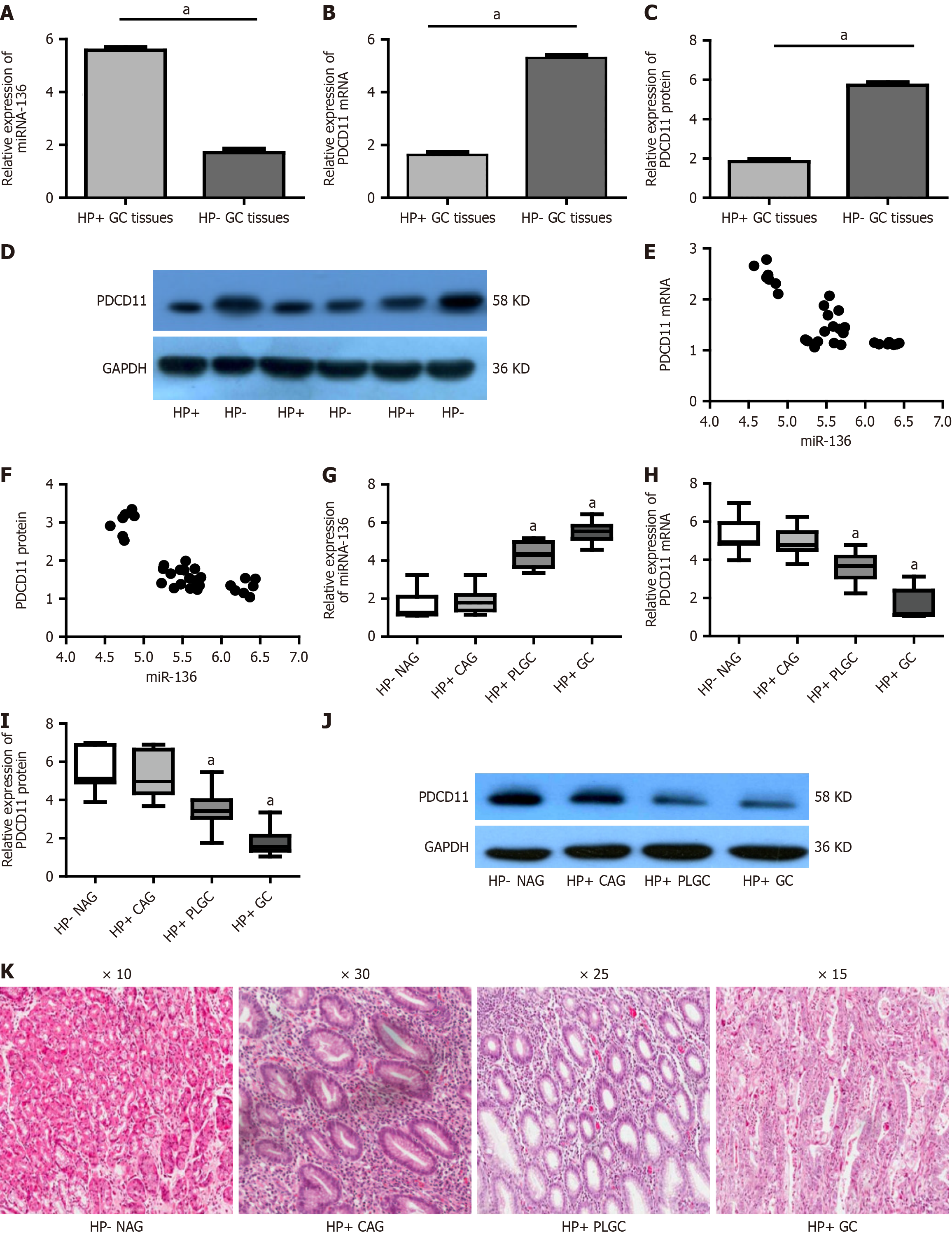

The expression of miR-136 and PDCD11 in H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative human GC tissues was first assessed. miR-136 expression was significantly upregulated while PDCD11 expression was significantly downregulated in H.

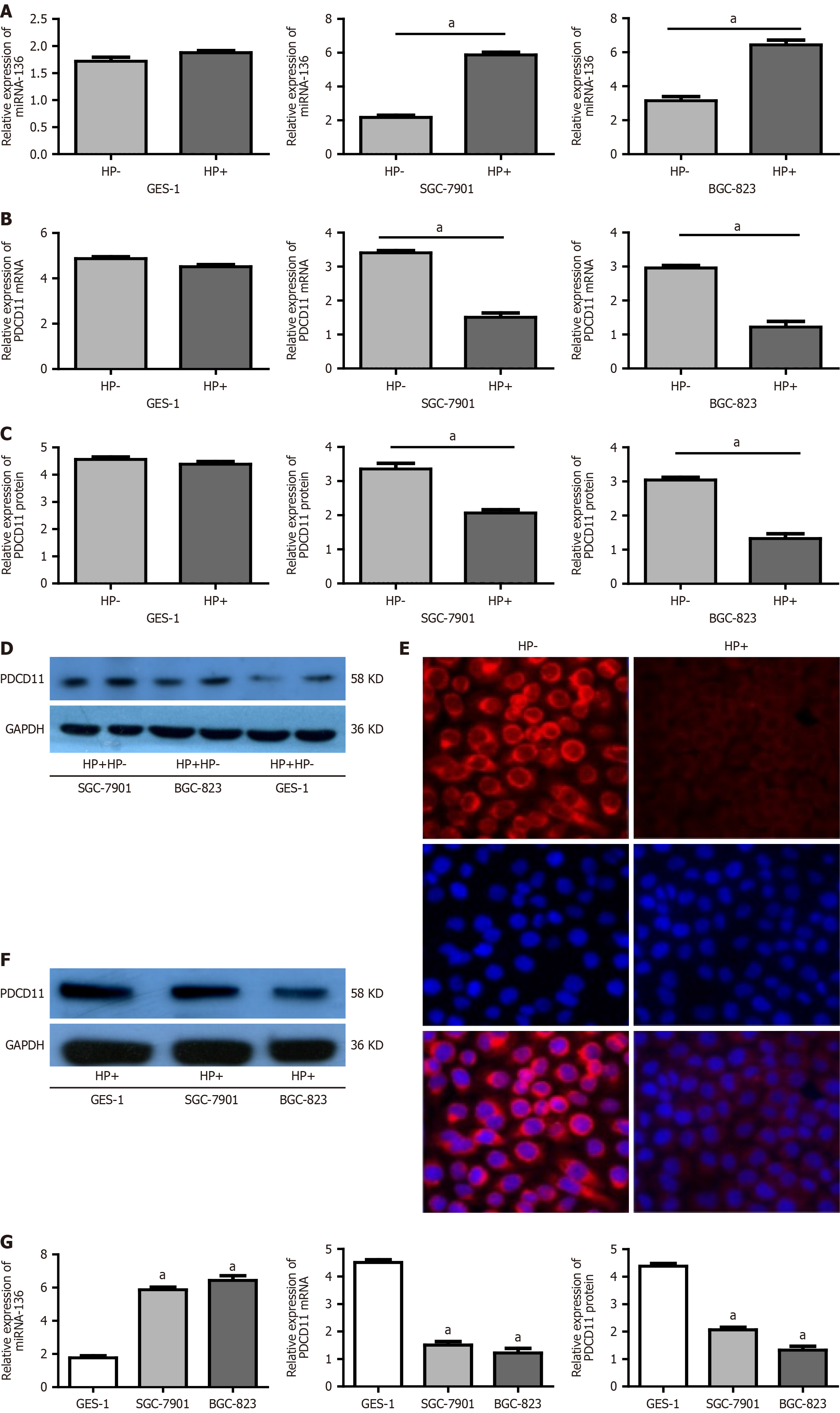

Next, the expression of miR-136 and PDCD11 in the GC cells infected with H. pylori was examined. miR-136 expression was significantly upregulated while the PDCD11 expression was significantly downregulated in SGC-7901 and BGC-823 cells infected with H. pylori compared with control cells (not infected with H. pylori) (P < 0.01). In GES-1 cells although miR-136 showed an increasing trend and PDCD11 showed a decreasing trend after infection with H. pylori, the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05; Figure 2A-E). Compared with GES-1 cells, miR-136 expression was significantly upregulated and the PDCD11 expression was significantly downregulated in SGC-7901 and BGC-823 cell lines after H. pylori infection (all P < 0.01; Figure 2F and G).

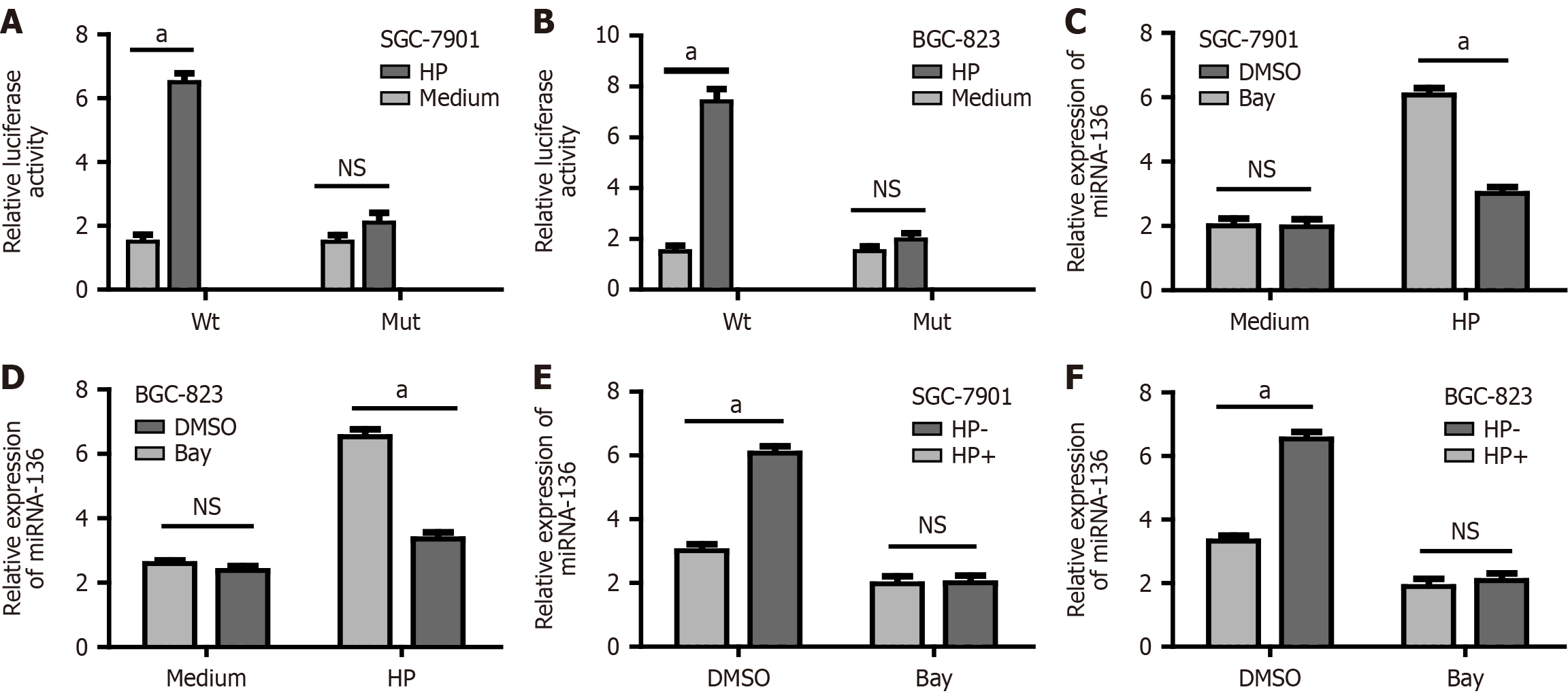

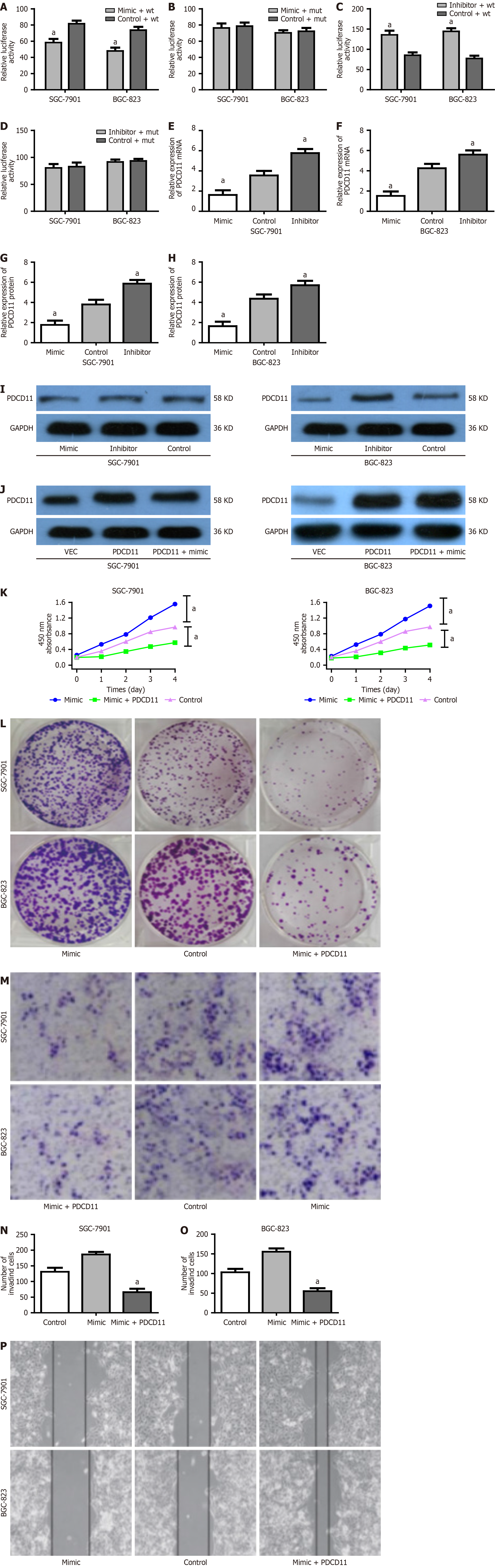

Here, the mechanism behind the miR-136 upregulation and in vitro was investigated. Software (TargetScan 7.1) predicted an NF-κB binding site in the miR-136 promoter. To provide further evidence for the regulatory relationship between NF-κB and miR-136, we transfected GC cells with the reporter vector of the miR-136 promoter containing the NF-κB binding site (WT) and the Mut. Forty-eight hours later, GC cells were cocultured with H. pylori for 24 h, after which the fluorescence intensity was analyzed. The luciferase activity of the WT reporter vector was significantly increased after H. pylori infection while there was no significant change in luciferase before and after infection in the Mut group (Figure 3A and B). In addition in the control group, miRNA-136 mRNA levels increased significantly after infection. However, in the inhibitor and siRNA group, there were no significant differences in miRNA-136 mRNA levels before and after infection (Figure 3C-F), suggesting that H. pylori infection was associated with the upregulated expression of miRNA-136 by NF-κB.

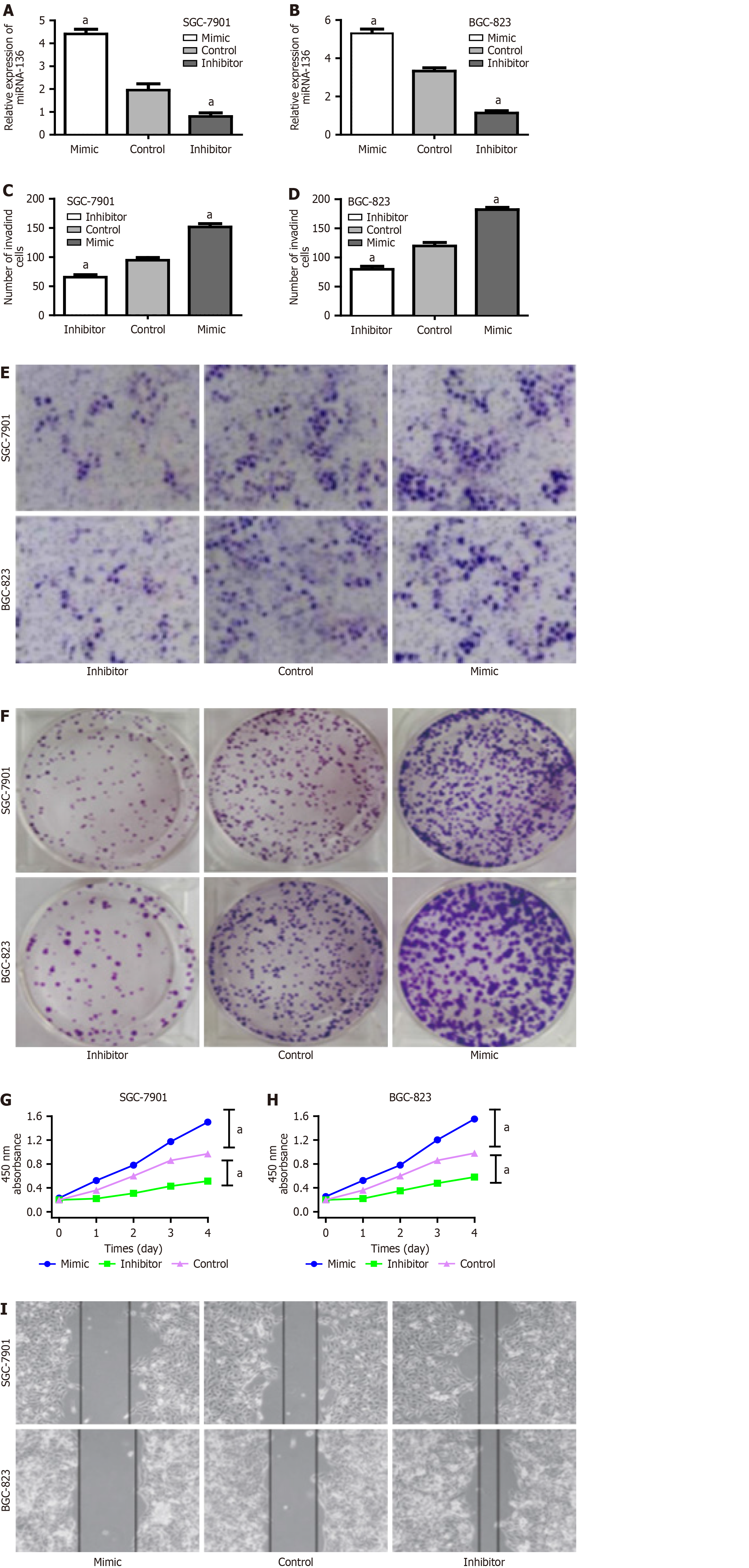

To further elucidate the causative effect of miR-136 on the proliferation and migration, SGC-7901 and BGC-823 cells infected with H. pylori and transfected with miR-136 mimic, miR-136 inhibitor, or miR-NC were assessed by CCK-8 assay, colony-formation assay, wound healing assay, and Transwell assay. Transfection efficacy was tested by miR-136 expression via RT-qPCR analysis (Figure 4A and B). The miR-136 inhibitor significantly reduced the proliferation and migration; conversely, the miR-136 mimic had the opposite effect (Figure 4C-I). Thus, we concluded that miR-136 overexpression induced by H. pylori could promote the proliferation and migration of GC cells, and the inhibition of miR-136 expression could suppress the proliferation and migration of GC cells with H. pylori infection.

Taking into consideration a significant negative correlation between the expression of miR-136 and PDCD11, we speculated that PDCD11 may be the target gene of miR-136. Software predicted a possible binding site of miR-136 in the 3′-UTR of PDCD11 mRNA. Luciferase reporter assay showed that the miR-136 mimic significantly inhibited the luciferase activity of the WT reporter plasmid instead of the Mut (Figure 5A and B). The miR-136 inhibitor significantly enhanced the luciferase activity of the WT reporter plasmid instead of the Mut (Figure 5C and D). Moreover, we found that PDCD11 expression was observably upregulated by the miR-136 inhibitor. On the contrary miR-136 mimic remarkably reduced PDCD11 expression (Figure 5E-I). Taken together, we confirmed that PDCD11 was a downstream target gene of miR-136.

To further verify that miR-136 promotes the proliferation and migration of GC cells after H. pylori infection by targeting PDCD11 after being infected with H. pylori, SGC-7901 and BGC-823 were transfected with the miR-136 mimic, miR-136 mimic plus PDCD11 (the transfected PDCD11 plasmid cannot be inhibited by miR-136) (Figure 5J), or miR-NC. The proliferation and migration of GC cells transfected with miR-136 mimic plus PDCD11 were significantly inhibited via CCK-8 assay, colony formation assay, wound healing assay, and Transwell assay (Figure 5K-P). Based on these results, we concluded that the miR-136 overexpression induced by H. pylori infection promotes GC cell proliferation and migration by targeting PDCD11.

In order to explore the effect of miR-136 on H. pylori-positive GC cells by targeting PDCD11 in vivo, BGC-823 GC cells infected with H. pylori and transfected with miR-136 mimic, inhibitor, miR-136 plus PDCD11, or miR-NC were subcutaneously inoculated into the right flank of nude mice. The miR-136 mimic group showed faster tumor growth than the miR-NC group while the tumor growth was significantly reduced in the miR-136 inhibitor group compared with the miR-NC group. We also observed that PDCD11 could abrogate tumor growth induced by miR-136 in a mouse model (all P < 0.01; Figure 6). Accordingly, it was concluded that inhibiting miR-136 expression could reduce gastric tumorigenesis by targeting PDCD11 after H. pylori infection in vivo.

This study assessed the underlying mechanisms of miR-136 during gastric carcinogenesis with H. pylori infection. Data suggested that miR-136 may be a novel diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target in H. pylori-associated early-stage gastric carcinogenesis. Also, our results suggested that NF-κB-miR-136-PDCD11 may be involved in this process.

H. pylori is the main pathogen related to gastric tumorigenesis. H. pylori infection sequentially leads to chronic gastritis, gastric atrophy, and IM, eventually resulting in GC[17]. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism of progression from gastric inflammation to cancer after H. pylori infection remains unclear. Previous studies suggested that H. pylori infection can induce the deregulation of multiple signaling pathways and the activation of downstream oncogenes involved in gastric tumorigenesis[18]. Some previous data also indicated an important association between H. pylori and miRNA in H. pylori-infected gastric tissue and GC[19]. However, whether miRNAs act as tumor promoters or suppressors depends on the miRNA and their tissue expression. For example a previous study[20] found that the overexpression of onco-miRNA miR-130 promoted GC proliferation and metastasis by combining with the 3’-UTR of TGF-β and inhibiting its expression. On the other hand miR-107 can inhibit the proliferation of GC in vivo and in vitro by targeting TRIAP1[21].

A recent study suggested that miR-136 may be involved in several tumors as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor. For instance, miR-136 can suppress ovarian cancer by targeting Notch3[22] but also promote lung cancer cell proliferation and migration by targeting PTEN and activating ERK1/2[23]. We speculate that different tumors, even those originating from the same tissues, can show different genetic instability. Zheng et al[13] found that miR-136 inhibited GC-specific peritoneal metastasis by targeting HOXC10. In addition Yu et al[14] suggested that miR-136 was significantly downregulated in GC cells, and restoring miR-136 expression promoted apoptosis of GC cells by downregulating the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins AEG-1 and BCL2. However, Chen et al[15] revealed that miR-136 promoted proliferation and invasion in GC cells through the PTEN/AKT/P-Akt signaling pathway. These results suggest the complexity of miR-136 in tumorigenesis, and whether miR-136 acts as a tumor promoter or suppressor depends on the tissue heterogeneity and expression level as well as the signaling pathway involved.

This study found that H. pylori upregulated miR-136 expression in GC, promoting the proliferation and migration of H. pylori-infected GC cells by targeting PDCD11. In vivo data further confirmed that miR-136 promoted the tumorigenesis of H. pylori-positive GC cells by targeting PDCD11 in mice while the inhibition of miR-136 reduced tumor growth. Yang et al[24] found inflammatory gene upregulation, uncontrolled p65 activation, and imbalanced macrophage generation in PDCD11 Mut macrophages; this mutation suppressed c-Rel-dependent TGFβ1 expression and was involved in microglia differentiation and tumorigenesis. This study suggested that overexpressed miR-136 and the underexpressed PDCD11 are closely related to gastric tumorigenesis after H. pylori infection and that the inhibition of miR-136 expression could be a novel therapy to decrease the incidence of GC after H. pylori infection. Based on these results, the difference in the function of miR-136 may be explained by imperfect complementary interaction between miR-136 and its target gene. Our study reconfirmed the complexity of miR-136 in tumorigenesis, including GC.

NF-κB is a classical inflammatory signaling molecule in the progression from inflammation to carcinogenesis. Yang et al[25] found that the NF-κB/miR-223-3p/ARID1A axis is involved in H. pylori CagA-induced gastric carcinogenesis and progression. Moreover, another study found that H. pylori CagA protein regulated NF-κB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses[26]. More recently, Soutto et al[27] discovered that NF-kB-dependent activation of STAT3 by H. pylori was suppressed by TFF1, a small secreted protein that protects the integrity of the gastric mucosa and promotes its repair after injury. Our software prediction and luciferase report assay confirmed that the expression of miR-136 was upregulated through the NF-κB signaling molecule after H. pylori infection. Based on the above data, we concluded that miR-136 could act as a bridge between gastric inflammation and GC by NF-κB after H. pylori infection.

A number of precancerous conditions have been recognized, such as CAG and IM due to H. pylori infection[28]. The prognosis of GC is closely related to clinical stage, and early detection and treatment have positive effects on improving prognosis, but biological markers for early diagnosis are currently lacking. In this study we evaluated miR-136 expression in each stage of Correa’s Cascade and found that miR-136 expression was significantly upregulated in patients who are high risk. Our results showed that miR-136 expression was significantly upregulated in the PLGC tissues compared with that in the NAG and CAG tissues while there were no significant differences between the CAG tissues and NAG tissues. These results are consistent with the results of in vitro experiments that indicated miR-136 was significantly upregulated in GC cells (SGC-7901 and BGC-823) but not in normal cells (GES-1) after H. pylori infection. Our work supported that miR-136 could serve as an effective biomarker to identify patients who are high risk for GC after H. pylori infection.

Since continuing H. pylori infection may induce GC occurrence, successful H. pylori eradication was expected to decrease GC incidence drastically[29]. Unfortunately, approximately 10%-20% of individuals with H. pylori eradication were reported to be at risk of developing cancer during the 30 years of surveillance. The plausible cause for this phenomenon was severe atrophy that occurred before eradication[30]. Therefore, the effect of H. pylori eradication on reducing the incidence of GC depends on the severity of atrophy at the time of H. pylori eradication. Once severe atrophy and IM occur, H. pylori eradication cannot reduce the risk for GC, suggesting that H. pylori eradication should be performed before the point of no return[31]. It is urgent to seek a more effective approach to monitor the progression of gastric precancerous lesions after H. pylori infection to detect the GC occurrence at an early stage after H. pylori infection. The OLGA/OLGIM staging system stratifies GC risk by quantifying atrophy and IM with stages III-IV indicating significantly elevated malignancy potential[32]. Our study confirmed miR-136 increases with disease severity, particularly in OLGA/OLGIM III-IV cases linked to GC progression. This positions miR-136 as a promising biomarker to stratify high-risk CAG and PLGC, enabling targeted surveillance and treatment of H. pylori-positive GC for improved outcomes.

This study had several limitations. First, its single-center design and limited sample size may introduce selection bias and restrict the generalizability of our findings. Therefore, validation in larger, multicenter cohorts that encompass a diverse range of GC subtypes is essential. Second, our in vitro experiments were confined to two GC cell lines (SGC-7901 and BGC-823) that might have narrowed the pathological correlation of our results. Third, the biological mechanisms linking miR-136 expression to H. pylori-associated gastric carcinogenesis also require deeper exploration through pathway analyses. Addressing these gaps will strengthen the clinical applicability of miR-136 as a risk-stratification biomarker in post-eradication surveillance. Future studies are warranted to validate our findings in large, multicenter cohorts with diverse GC subtypes to further dissect the molecular mechanisms using precise tools like CRISPR/Cas9 and CagA-isogenic strains and to ultimately assess the translational potential of miR-136 through preclinical therapeutic assessments and biomarker benchmarking. Future studies should also examine the possible link between miR-136 and OLGA/OLGIM staging for GC risk stratification and should validate this in longitudinal cohorts post-eradication to assess the utility of miR-136 in surveillance programs.

Our data suggested that miR-136 as an oncomiRNA may be a critical step in the progression from gastric inflammation to cancer after H. pylori infection. However, this data should be confirmed in a study with a larger sample and different H. pylori infection statuses. In addition future work should investigate the other signaling pathways through which miR-136 is involved in H. pylori-related GC.

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56663] [Article Influence: 7082.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (135)] |

| 2. | Sun J, Nan Q. Survival benefit of surgical resection for stage IV gastric cancer: A SEER-based propensity score-matched analysis. Front Surg. 2022;9:927030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li Y, Feng A, Zheng S, Chen C, Lyu J. Recent Estimates and Predictions of 5-Year Survival in Patients with Gastric Cancer: A Model-Based Period Analysis. Cancer Control. 2022;29:10732748221099227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mera RM, Bravo LE, Camargo MC, Bravo JC, Delgado AG, Romero-Gallo J, Yepez MC, Realpe JL, Schneider BG, Morgan DR, Peek RM Jr, Correa P, Wilson KT, Piazuelo MB. Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori infection as a determinant of progression of gastric precancerous lesions: 16-year follow-up of an eradication trial. Gut. 2018;67:1239-1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Sheu BS, Wu MS, Chiu CT, Lo JC, Wu DC, Liou JM, Wu CY, Cheng HC, Lee YC, Hsu PI, Chang CC, Chang WL, Lin JT. Consensus on the clinical management, screening-to-treat, and surveillance of Helicobacter pylori infection to improve gastric cancer control on a nationwide scale. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liou JM, Lee YC, El-Omar EM, Wu MS. Efficacy and Long-Term Safety of H. pylori Eradication for Gastric Cancer Prevention. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Uno Y. Prevention of gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori eradication: A review from Japan. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3992-4000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hatakeyama M. Structure and function of Helicobacter pylori CagA, the first-identified bacterial protein involved in human cancer. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2017;93:196-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Muzaheed. Helicobacter pylori Oncogenicity: Mechanism, Prevention, and Risk Factors. ScientificWorldJournal. 2020;2020:3018326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gilani N, Arabi Belaghi R, Aftabi Y, Faramarzi E, Edgünlü T, Somi MH. Identifying Potential miRNA Biomarkers for Gastric Cancer Diagnosis Using Machine Learning Variable Selection Approach. Front Genet. 2021;12:779455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hao NB, He YF, Li XQ, Wang K, Wang RL. The role of miRNA and lncRNA in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:81572-81582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ouyang J, Xie Z, Lei X, Tang G, Gan R, Yang X. Clinical crosstalk between microRNAs and gastric cancer (Review). Int J Oncol. 2021;58:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zheng J, Ge P, Liu X, Wei J, Wu G, Li X. MiR-136 inhibits gastric cancer-specific peritoneal metastasis by targeting HOXC10. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317706207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yu L, Zhou GQ, Li DC. MiR-136 triggers apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells by targeting AEG-1 and BCL2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:7251-7256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen X, Huang Z, Chen R. Microrna-136 promotes proliferation and invasion ingastric cancer cells through Pten/Akt/P-Akt signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:4683-4689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu M, Feng S, Qian M, Wang S, Zhang K. Helicobacter pylori Infection Combined with OLGA and OLGIM Staging Systems for Risk Assessment of Gastric Cancer: A Retrospective Study in Eastern China. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2022;15:2243-2255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ding SZ, Du YQ, Lu H, Wang WH, Cheng H, Chen SY, Chen MH, Chen WC, Chen Y, Fang JY, Gao HJ, Guo MZ, Han Y, Hou XH, Hu FL, Jiang B, Jiang HX, Lan CH, Li JN, Li Y, Li YQ, Liu J, Li YM, Lyu B, Lu YY, Miao YL, Nie YZ, Qian JM, Sheng JQ, Tang CW, Wang F, Wang HH, Wang JB, Wang JT, Wang JP, Wang XH, Wu KC, Xia XZ, Xie WF, Xie Y, Xu JM, Yang CQ, Yang GB, Yuan Y, Zeng ZR, Zhang BY, Zhang GY, Zhang GX, Zhang JZ, Zhang ZY, Zheng PY, Zhu Y, Zuo XL, Zhou LY, Lyu NH, Yang YS, Li ZS; National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (Shanghai), Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention & Treatment Alliance of China (GECA), Helicobacter pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, and Chinese Alliance for Helicobacter pylori Study. Chinese Consensus Report on Family-Based Helicobacter pylori Infection Control and Management (2021 Edition). Gut. 2022;71:238-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Servetas SL, Bridge DR, Merrell DS. Molecular mechanisms of gastric cancer initiation and progression by Helicobacter pylori. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29:304-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maeda M, Moro H, Ushijima T. Mechanisms for the induction of gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori infection: aberrant DNA methylation pathway. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Duan J, Zhang H, Qu Y, Deng T, Huang D, Liu R, Zhang L, Bai M, Zhou L, Ying G, Ba Y. Onco-miR-130 promotes cell proliferation and migration by targeting TGFβR2 in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:44522-44533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yan J, Dai L, Yuan J, Pang M, Wang Y, Lin L, Shi Y, Wu F, Nie R, Chen Q, Wang L. miR-107 Inhibits the Proliferation of Gastric Cancer Cells In vivo and In vitro by Targeting TRIAP1. Front Genet. 2022;13:855355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jeong JY, Kang H, Kim TH, Kim G, Heo JH, Kwon AY, Kim S, Jung SG, An HJ. MicroRNA-136 inhibits cancer stem cell activity and enhances the anti-tumor effect of paclitaxel against chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells by targeting Notch3. Cancer Lett. 2017;386:168-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shen S, Yue H, Li Y, Qin J, Li K, Liu Y, Wang J. Upregulation of miR-136 in human non-small cell lung cancer cells promotes Erk1/2 activation by targeting PPP2R2A. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:631-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yang R, Zhan M, Guo M, Yuan H, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Chen S, de The H, Chen Z, Zhou J, Zhu J. Yolk sac-derived Pdcd11-positive cells modulate zebrafish microglia differentiation through the NF-κB-Tgfβ1 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:170-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yang F, Xu Y, Liu C, Ma C, Zou S, Xu X, Jia J, Liu Z. NF-κB/miR-223-3p/ARID1A axis is involved in Helicobacter pylori CagA-induced gastric carcinogenesis and progression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Koeppel M, Garcia-Alcalde F, Glowinski F, Schlaermann P, Meyer TF. Helicobacter pylori Infection Causes Characteristic DNA Damage Patterns in Human Cells. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1703-1713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Soutto M, Bhat N, Khalafi S, Zhu S, Poveda J, Garcia-Buitrago M, Zaika A, El-Rifai W. NF-kB-dependent activation of STAT3 by H. pylori is suppressed by TFF1. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Quach DT, Hiyama T, Gotoda T. Identifying high-risk individuals for gastric cancer surveillance from western and eastern perspectives: Lessons to learn and possibility to develop an integrated approach for daily practice. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3546-3562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang L, Wang J, Li S, Bai F, Xie H, Shan H, Liu Z, Ma T, Tang X, Tang H, Qin A, Lei S, Zuo C. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on prognosis of postoperative early gastric cancer: a multicenter study. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kaji K, Hashiba A, Uotani C, Yamaguchi Y, Ueno T, Ohno K, Takabatake I, Wakabayashi T, Doyama H, Ninomiya I, Kiriyama M, Ohyama S, Yoneshima M, Koyama N, Takeda Y, Yasuda K. Grading of Atrophic Gastritis is Useful for Risk Stratification in Endoscopic Screening for Gastric Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:71-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Okada K, Suzuki S, Naito S, Yamada Y, Haruki S, Kubota M, Nakajima Y, Shimizu T, Ando K, Uchida Y, Hirasawa T, Fujisaki J, Tsuchida T. Incidence of metachronous gastric cancer in patients whose primary gastric neoplasms were discovered after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:1152-1159.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Isajevs S, Savcenko S, Liepniece-Karele I, Piazuelo MB, Kikuste I, Tolmanis I, Vanags A, Gulbe I, Mezmale L, Samentaev D, Tazedinov A, Samsutdinov R, Belihina T, Igissinov N, Leja M. High-risk individuals for gastric cancer would be missed for surveillance without subtyping of intestinal metaplasia. Virchows Arch. 2021;479:679-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/