Published online Nov 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.111243

Revised: August 18, 2025

Accepted: September 23, 2025

Published online: November 16, 2025

Processing time: 141 Days and 16 Hours

Periampullary diverticulum (PAD) is a common anatomical variant, but its as

To examine the association between PAD (including subtypes A/B) and PEP inci

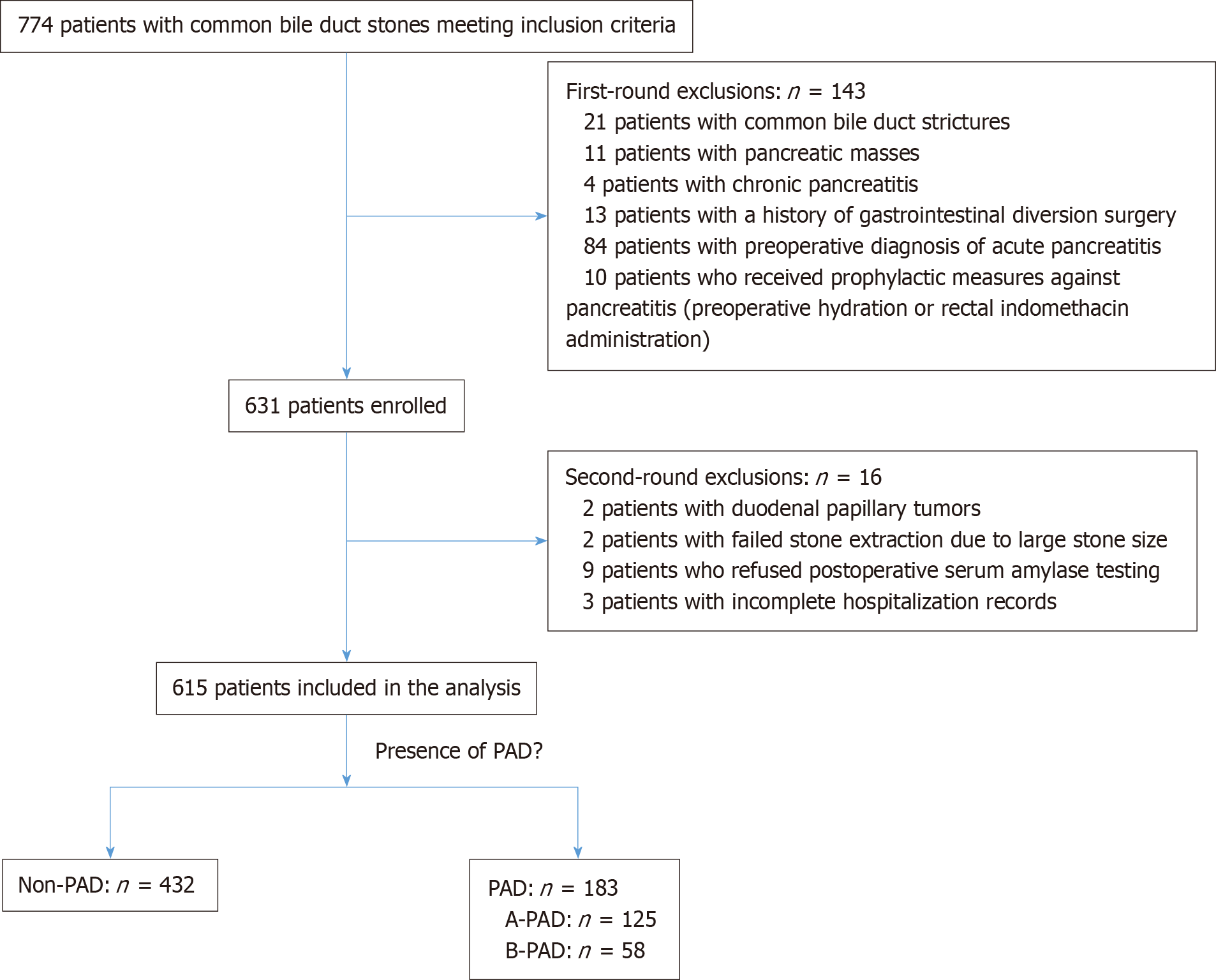

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 615 patients undergoing ERCP at two tertiary hospitals from 2023 to 2025. Participants were stratified into PAD (n = 183; subtype A = 125, subtype B = 58) and non-PAD (n = 432) groups. The primary outcome was PEP incidence. Multivariable logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, gallbladder surgery, and guidewire insertion. Sta

PAD prevalence was 29.8% (183/615). PEP occurrence was more frequent in PAD patients [15.3% (28/183)] than in non-PAD patients [4.2% (18/432)], odds ratio (OR) = 3.86, 95% confidence interval: 2.03-7.35, P < 0.001. Type B PAD showed a stronger association with PEP than type A (OR = 14.16, 95% confidence interval: 5.84-34.34, P < 0.001). Guidewire pancreatic duct entry was linked to higher PEP odds in PAD patients (adjusted OR = 5.02, P < 0.05). Hypertension also demonstrated an association with PEP in the PAD subgroup (P = 0.012).

PAD, particularly type B, is independently associated with PEP after ERCP. Patients with these features, especially those with hypertension or pancreatic duct instrumentation, may benefit from enhanced monitoring and prophylaxis.

Core Tip: This study demonstrates that periampullary diverticulum (PAD), particularly type B, shows a significant as

- Citation: Shu J, Liao YS, Zhang YJ, Zhou WL, Zhang H. Impact of periampullary diverticulum on the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiography pancreatitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(11): 111243

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i11/111243.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.111243

Periampullary diverticulum (PAD) is a mucosal outpouching lesion located within 2.5 cm of the major duodenal papilla in the ampulla of Vater region[1]. PAD has gained increasing recognition among endoscopists with the widespread adoption of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Current clinical research primarily focuses on PAD’s influence on technical aspects of ERCP, particularly its association with increased cannulation difficulty[2,3]. However, evidence regarding PAD’s potential role in post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) development, especially across different PAD subtypes, remains limited. Previous studies have suggested that the spatial relationship between PAD and the duodenal papilla may correlate with PEP risk, though systematic validation of this hypothesis is lacking[4-6]. The study of Boix et al[5], which categorizes PAD based on anatomical relationship with the papilla, has limited clinical utility due to its complexity. Panteris et al[6] subsequently proposed a simplified classification system (types A and B). Utilizing Panteris et al[6] criteria, this study aims to: (1) Evaluate PAD’s association with PEP incidence; (2) Compare PEP rates between PAD subtypes (A vs B); and (3) Identify potential strategies for optimizing ERCP safety in high-risk populations.

This retrospective cohort study included 774 consecutive patients diagnosed with choledocholithiasis who underwent ERCP at The Central Hospital of Wuhan and The Third People’s Hospital of Hubei Province between January 2023 and March 2025. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Central Hospital of Wuhan (Approval No. WHZXKYL2025-135). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this research. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Pre-existing acute or chronic pancreatitis or hyperamylasemia; (2) Previous ERCP intervention; (3) History of gastrointestinal reconstruction surgery (including Billroth II, Roux-en-Y anastomosis, or pancreaticoduodenectomy); (4) Concurrent biliary strictures (benign or malignant), pancreatic lesions, or duodenal protrusions; (5) Age under 18 years; (6) Technically unsuccessful procedures or incomplete clinical data; and (7) Prophylactic administration of PEP prevention measures (e.g., intravenous hydration or rectal indomethacin).

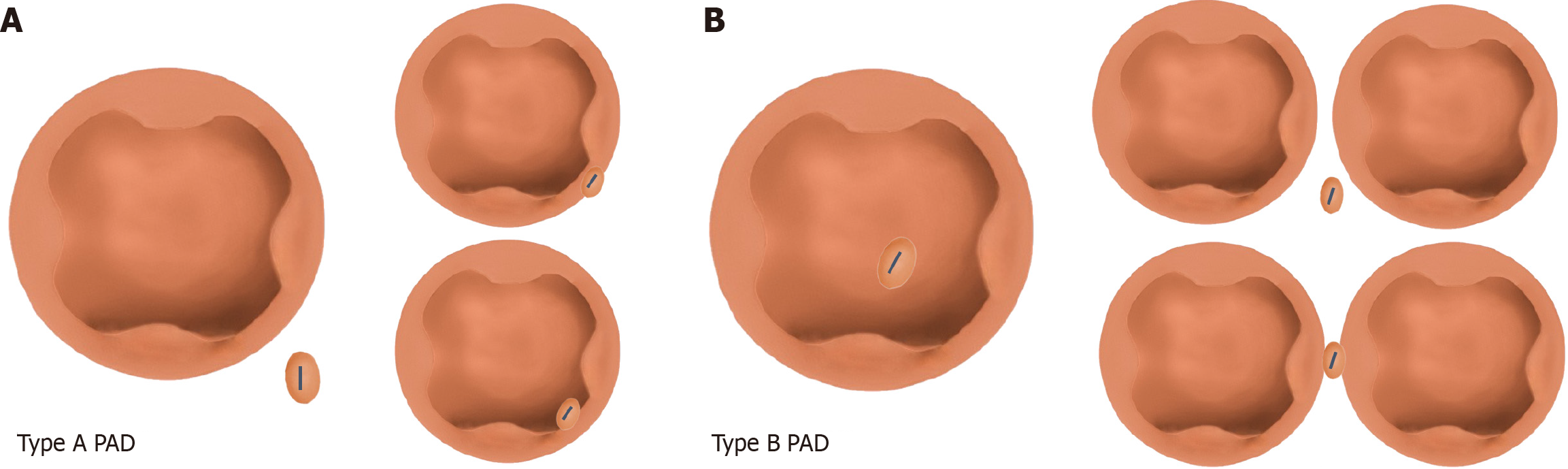

Baseline data included the following: Age, gender, medical history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and viral hepatitis (including hepatitis B and hepatitis C), and history of gallstone surgery. Intraoperative indicators included the use of cannulation method (≥ 1 pancreatic duct guidewire placement) and presence/absence of PAD. Patients with PAD were allocated to the PAD group, while those without PAD were assigned to the non-PAD group. According to the typing criteria proposed by Panteris et al[6], the PAD group was further stratified into two subgroups: The type A PAD subgroup (papilla located at the edge of the diverticulum or within a radius of 2 cm from the diverticular edge) and the type B PAD subgroup (papilla located inside the diverticulum or lying between two adjacent diverticula; Figure 1). Postoperative indicators were the presence of PEP and/or hyperamylasemia.

The primary outcome measure was PEP, and the secondary outcome measure was hyperamylasemia. PEP was defined as follows: (1) New or worsened abdominal pain within 24 hours after ERCP; (2) A serum amylase level ≥ 3 times normal; and/or (3) Imaging evidence of pancreatitis. The diagnosis of PEP required two of the three criteria, as per the Atlanta Consensus[7]. Hyperamylasemia refers to serum amylase levels above the upper normal limit at 4 hours or 12 hours after ERCP, without abdominal pain or related imaging findings[8,9].

The main clinical outcome of this study was the occurrence of postoperative pancreatitis (PEP), and all patients were divided into the PEP and non-PEP groups accordingly. We first compared the baseline characteristics between the two groups. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage) and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using the independent samples t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test.

To handle missing data, we used the multiple imputation by chained equations method for covariates with < 20% missing data. After addressing missing data, we constructed univariate and multivariate logistic regression models to explore independent risk factors for PEP. Results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All variables that showed potential associations (P < 0.10) or had significant clinical relevance individually in univariate analysis were included in the final multivariate model. To clearly demonstrate the impact of the main study variables, such as diverticulum type, after adjusting for confounding factors, we constructed stratified models. Model 1 was a crude analysis without any adjustments, model 2 adjusted for age and gender, and model 3 further adjusted for all other significant covariates identified in univariate analysis based on model 2. Finally, we assessed the robustness of the main results through sensitivity analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2), and a two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Following application of the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 615 patients were included in the final analysis. The study population comprised 183 patients with PAD (type A: n = 125; type B: n = 58) and 432 patients without PAD (Figure 2). Comparative analysis of demographic and clinical characteristics revealed similar distributions between groups for sex, hypertension prevalence, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, hepatitis status, and cholecystectomy history (all P > 0.05). However, patients in the PAD group showed higher mean age compared to the non-PAD group (69.0 ± 12.8 years vs 61.6 ± 15.9 years, P < 0.001; Table 1).

| Variable | Total (n = 615) | Absence of diverticulum (n = 432) | Presence of diverticulum (n = 183) | Statistical value | P value |

| Sex | 1.298 | 0.255 | |||

| Male | 311 (50.6) | 212 (49.1) | 99 (54.1) | ||

| Female | 304 (49.4) | 220 (50.9) | 84 (45.9) | ||

| Age | 63.8 ± 15.4 | 61.6 ± 15.9 | 69.0 ± 12.8 | -6.082 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.942 | 0.332 | |||

| No | 341 (55.4) | 245 (56.7) | 96 (52.5) | ||

| Yes | 274 (44.6) | 187 (43.3) | 87 (47.5) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.576 | 0.448 | |||

| No | 518 (84.2) | 367 (85.0) | 151 (82.5) | ||

| Yes | 97 (15.8) | 65 (15.0) | 32 (17.5) | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 0.777 | 0.378 | |||

| No | 526 (85.5) | 373 (86.3) | 153 (83.6) | ||

| Yes | 89 (14.5) | 59 (13.7) | 30 (16.4) | ||

| Hepatitis | 0.766 | 0.382 | |||

| No | 573 (93.2) | 405 (93.8) | 168 (91.8) | ||

| Yes | 42 (6.8) | 27 (6.2) | 15 (8.2) | ||

| History of cholecystectomy | 0.999 | 0.317 | |||

| No | 486 (79.0) | 346 (80.1) | 140 (76.5) | ||

| Yes | 129 (21.0) | 86 (19.9) | 43 (23.5) |

The overall PEP incidence in our cohort of 615 patients was 6.83%. A significant association was observed between PAD presence and PEP occurrence (OR = 3.86, 95%CI: 2.03-7.35, P < 0.05). Among patients with PAD, guidewire entry into the pancreatic duct showed a positive association with PEP development (OR = 4.17, 95%CI: 2.17-7.99, P < 0.01). Notably, an inverse relationship was identified between postoperative hyperamylasemia and PEP incidence, with hyperamylasemia cases exhibiting significantly lower PEP rates (OR = 0.09, 95%CI: 0.01-0.65, P = 0.017). No statistically significant associations were found between PEP incidence and other examined variables, including sex, age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, or hepatitis status (all P > 0.05; Table 2).

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Sex: Male vs female | 1.39 (0.74-2.61) | 0.313 |

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | 0.451 |

| PAD: Yes vs no | 3.86 (2.03-7.35) | < 0.001 |

| Guidewire insertion into the pancreatic duct: Yes vs no | 4.17 (2.17-7.99) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension: Yes vs no | 0.75 (0.39-1.42) | 0.372 |

| Diabetes mellitus: Yes vs no | 0.71 (0.27-1.85) | 0.483 |

| Coronary heart disease: Yes vs no | 0.99 (0.4-2.42) | 0.979 |

| Hepatitis: Yes vs no | 0.32 (0.04-2.37) | 0.263 |

| History of cholecystectomy: Yes vs no | 0.38 (0.13-1.08) | 0.07 |

| Postoperative hyperamylasemia: Yes vs no | 0.09 (0.01-0.65) | 0.017 |

After adjusting for age, sex, and other baseline characteristics (model 1), the presence of PAD showed a strong positive association with PEP occurrence (adjusted OR = 4.13, 95%CI: 2.18-11.00, P < 0.001). In model 2, which incorporated additional adjustments for guidewire entry into the pancreatic duct, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and hepatitis), and procedural factors (cholecystectomy history and PEP prevention measures), this association remained robust (adjusted OR = 4.23, 95%CI: 2.06-8.69, P < 0.001). These results suggest that the relationship between PAD and PEP persists even after accounting for potential confounders. Notably, type B PAD demonstrated particularly strong associations with PEP (OR = 14, all P < 0.001), while type A PAD showed no significant correlation (P > 0.5). The significant trend across PAD types (P = 0.039 for trend) indicates a potential graded relationship between PAD classification and PEP occurrence (Table 3).

| Variable | Crude | Model 12 | Model 23 | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| PAD | ||||||

| No | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 3.86 (2.03-7.35) | < 0.001 | 4.13 (2.1-8.11) | < 0.001 | 4.23 (2.06-8.69) | < 0.001 |

| PAD type | ||||||

| Non-PAD | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| A-PAD | 1.22 (0.47-3.17) | 0.68 | 1.32 (0.5-3.49) | 0.572 | 1.52 (0.56-4.17) | 0.411 |

| B-PAD | 13.38 (6.39-28.03) | < 0.001 | 14.65 (6.63-32.33) | < 0.001 | 14.16 (5.84-34.34) | < 0.001 |

| P value for trend | 0.052 | 0.056 | 0.039 | |||

The analysis demonstrated that PAD was independently associated with PEP across multiple subgroups. Regarding guidewire positioning, PAD showed a significant association with PEP when the guidewire did not enter the pancreatic duct (adjusted OR = 5.02, 95%CI: 2.06-12.26, P < 0.001). However, no significant association was observed between PAD and PEP when the guidewire entered the pancreatic duct (P = 0.233), suggesting that intubation difficulty may attenuate the observed association with diverticula. In the hypertension-stratified analysis, the association between PAD and PEP appeared stronger in hypertensive patients (adjusted OR = 7.64) compared to non-hypertensive patients (adjusted OR = 2.52), with an interaction P value of 0.162. Although this interaction did not reach statistical significance, the findings may indicate potential effect modification. In certain subgroups (e.g., hepatitis and hyperamylasemia), extremely large OR values (e.g., > 1 × 108) due to sparse event numbers limited further analysis and interpretation (Table 4).

| Subgroup | Total | Event | Crude OR (95%CI) | Crude P value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted P value | P value for interaction |

| Males | 0.797 | ||||||

| No | 212 | 7 (3.3) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 99 | 11 (11.1) | 3.66 (1.37-9.75) | 0.009 | 3.74 (1.38-10.1) | 0.009 | |

| Females | |||||||

| No | 220 | 10 (4.5) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 84 | 14 (16.7) | 4.2 (1.79-9.88) | 0.001 | 4.49 (1.78-11.33) | 0.002 | |

| Without hypertension | 0.162 | ||||||

| No | 245 | 13 (5.3) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 96 | 13 (13.5) | 2.8 (1.25-6.27) | 0.013 | 2.52 (1.07-5.92) | 0.034 | |

| With hypertension | |||||||

| No | 187 | 4 (2.1) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 87 | 12 (13.8) | 7.32 (2.29-23.42) | 0.001 | 7.64 (2.36-24.71) | 0.001 | |

| Without diabetes mellitus | 0.398 | ||||||

| No | 367 | 16 (4.4) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 151 | 21 (13.9) | 3.54 (1.79-7) | < 0.001 | 3.46 (1.71-6.99) | 0.001 | |

| With diabetes mellitus | |||||||

| No | 65 | 1 (1.5) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 32 | 4 (12.5) | 9.14 (0.98-85.53) | 0.052 | 11.54 (1.15-116.01) | 0.038 | |

| Without coronary heart disease | 0.91 | ||||||

| No | 373 | 15 (4) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 153 | 21 (13.7) | 3.8 (1.9-7.59) | < 0.001 | 3.71 (1.79-7.67) | < 0.001 | |

| With coronary heart disease | |||||||

| No | 59 | 2 (3.4) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 30 | 4 (13.3) | 4.38 (0.75-25.48) | 0.1 | 3.59 (0.6-21.49) | 0.162 | |

| Without hepatitis | 0.374 | ||||||

| No | 405 | 17 (4.2) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 168 | 24 (14.3) | 3.8 (1.99-7.29) | < 0.001 | 3.95 (2.01-7.75) | < 0.001 | |

| With hepatitis | |||||||

| No | 27 | 0 (0) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 15 | 1 (6.7) | 02 | * | 7.82 (0.65-94.5) | 0.105 | |

| With history of cholecystectomy | 0.485 | ||||||

| No | 346 | 15 (4.3) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 140 | 23 (16.4) | 4.34 (2.19-8.59) | < 0.001 | 4.43 (2.17-9.04) | < 0.001 | |

| Without history of cholecystectomy | |||||||

| No | 86 | 2 (2.3) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 43 | 2 (4.7) | 2.05 (0.28-15.07) | 0.481 | 2.01 (0.27-14.96) | 0.495 | |

| Guidewires enter the pancreatic duct | 0.315 | ||||||

| No | 67 | 8 (11.9) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 47 | 11 (23.4) | 2.25 (0.83-6.13) | 0.112 | 1.93 (0.66-5.67) | 0.233 | |

| Guidewires did not enter the pancreatic duct | |||||||

| No | 365 | 9 (2.5) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 136 | 14 (10.3) | 4.54 (1.92-10.75) | 0.001 | 5.02 (2.06-12.26) | < 0.001 | |

| Without hyperamylasemia | 0.419 | ||||||

| No | 355 | 17 (4.8) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 136 | 24 (17.6) | 4.26 (2.21-8.22) | < 0.001 | 4.27 (2.18-8.38) | < 0.001 | |

| With hyperamylasemia | |||||||

| No | 77 | 0 (0) | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Yes | 47 | 1 (2.1) | 02 | 02 | 5.91 (0.52-67.8) | 0.158 |

This retrospective cohort study found that PAD was associated with an increased incidence of PEP, though not all PAD subtypes showed this trend. type B PAD, but not type A PAD, was significantly linked to PEP. Potential explanations include anatomical distortion from diverticula complicating endoscopic maneuvers and mechanically irritating the papilla; reduced ductal tension due to absent smooth muscle support, impairing drainage; and stasis of food residues promoting bacterial overgrowth and local inflammation, further obstructing secretion flow[10-13]. However, compared with the findings of Mohammad Alizadeh et al[14], the PEP incidence was higher in our study, possibly due to the stricter exclusion criteria and larger sample size. Clinically, PAD assessment before ERCP appears warranted.

By comparing the incidence of PEP in different PAD subtypes, we found that the distance from the nipple to PAD also affects its occurrence. Preliminary studies have shown that PAD close to the nipple exacerbates anatomical compression of the ampulla of Vater, causing distortion of the bile and pancreatic ducts and obstructing their drainage, which si

By analyzing the baseline characteristics of the patients, we found that the age of the PAD group was higher than that of the non-PAD group. The main mechanism is that the local anatomical structure of the duodenal wall in patients shows defects. With increasing age and continuous increases in intestinal cavity pressure, the smooth muscle tension of the intestinal wall at the defect site further weakens. The combined effect of these two factors causes the defective intestinal wall to protrude continuously, which leads to the formation of diverticula. This mechanism explains why patients with diverticula tend to be older, a conclusion confirmed by Suda et al[19]. A theory suggests that changes in bile duct pressure after cholecystectomy may lower the risk of postoperative pancreatitis complications[20,21]. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate this view. Table 4 shows that the OR for pancreatitis risk in patients with diver

The results of this study are of great significance for clinical practice. When assessing the risk of progressive PEP, it is important to consider both the presence and the type of PAD. If preoperative imaging assessment or endoscopy reveals a type B diverticulum, it should be regarded as a high-level warning signal, and the operator should adopt a more cautious strategy and take adequate preventive measures, such as placing a pancreatic duct stent, using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs preoperatively, or performing the procedure with a more experienced endoscopist[22]. These measures may help reduce the incidence of PEP. Consequently, they can improve patient prognosis, shorten hospital stays, alleviate economic burdens, and enhance quality of life. In contrast, patients with type A diverticulum generally do not warrant heightened concern regarding their risk.

This study has yielded some results on the relationship between PAD and PEP, but limitations remain. First, as this is a retrospective analysis, selection bias may exist. Second, the strict exclusion criteria led to a small sample size, limiting detailed study of the relationship between PAD subtypes and PEP. This is especially clear in the analysis of type B PAD, where the estimated OR = 14.16 is high but the 95%CI is wide (5.84-34.34). This suggests that although the risk appears high, the exact magnitude is uncertain, likely due to the small size of the type B PAD group. Therefore, future large, multicenter studies are needed to more accurately estimate its effects. The relatively short follow-up for some patients prevented comprehensive long-term assessment, possibly missing cases of postoperative hyperamylasemia. Since the incidence of postoperative hemorrhage, perforation, and postoperative infection is extremely low, we did not include these complications in the analysis.

This study shows that peripapillary diverticula independently increase the risk of PEP. Type B PAD significantly increases the risk of PEP. Clinicians should thoroughly assess the procedure-related risks for diverticulum patients during ERCP and take appropriate preventive measures to reduce PEP occurrence. Although the interaction between diverticulum and hypertension in patients is not statistically significant (P = 0.162), a mild synergistic effect on PEP incidence cannot be ruled out. Therefore, strengthened prospective monitoring and management of this population are recommended. Future prospective, multicenter, large-sample studies are needed to investigate how hypertension, diabetes, cholecystectomy history, and peripapillary diverticula affect the risk of postoperative pancreatitis, providing more reliable evidence for clinical practice.

| 1. | Lobo DN, Balfour TW, Iftikhar SY, Rowlands BJ. Periampullary diverticula and pancreaticobiliary disease. Br J Surg. 1999;86:588-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tabak F, Ji GZ, Miao L. Impact of periampullary diverticulum on biliary cannulation and ERCP outcomes: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:5953-5961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Afify S, Elsabaawy M, Al-Arab AE, Edrees A. Impact of periampullary diverticulum on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: bridging the gap between fiction and reality. Prz Gastroenterol. 2024;16:446-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang X, Zhao J, Wang L, Ning B, Zeng W, Tao Q, Ren G, Liang S, Luo H, Wang B, Farrell JJ, Pan Y, Guo X, Wu K. Relationship between papilla-related variables and post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: A multicenter, prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:2184-2191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boix J, Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Añaños F, Domènech E, Morillas RM, Gassull MA. Impact of periampullary duodenal diverticula at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a proposed classification of periampullary duodenal diverticula. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:208-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Panteris V, Vezakis A, Filippou G, Filippou D, Karamanolis D, Rizos S. Influence of juxtapapillary diverticula on the success or difficulty of cannulation and complication rate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:903-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Smeets X, Bouhouch N, Buxbaum J, Zhang H, Cho J, Verdonk RC, Römkens T, Venneman NG, Kats I, Vrolijk JM, Hemmink G, Otten A, Tan A, Elmunzer BJ, Cotton PB, Drenth J, van Geenen E. The revised Atlanta criteria more accurately reflect severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis compared to the consensus criteria. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:557-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fukuda R, Hakuta R, Nakai Y, Nishio H, Endo G, Kurihara K, Tange S, Takaoka S, Oyama H, Noguchi K, Suzuki T, Sato T, Ishigaki K, Saito T, Takahara N, Hamada T, Ito Y, Fujishiro M. The Effectiveness of Additional Hydration for Hyperamylasemia After Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: A Propensity-matched Analysis. Pancreas. 2025;54:e667-e673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akca S, Atar GE, Ocal S, Buldukoglu OC, Koker G, Isik MD, Kaya B, Deniz H, Harmandar FA, Cekin AH. Association of periampullary diverticulum types with post-ERCP hyperamylasemia: a retrospective observational study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025;25:284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miyazaki S, Sakamoto T, Miyata M, Yamasaki Y, Yamasaki H, Kuwata K. Function of the sphincter of Oddi in patients with juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula: evaluation by intraoperative biliary manometry under a duodenal pressure load. World J Surg. 1995;19:307-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang C, Chen S, Wang Z, Zhang J, Yu W, Wang Y, Si W, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Liang T. Exploring the mechanism of intestinal bacterial translocation after severe acute pancreatitis: the role of Toll-like receptor 5. Gut Microbes. 2025;17:2489768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rizwan MM, Singh H, Chandar V, Zulfiqar M, Singh V. Duodenal diverticulum and associated pancreatitis: case report with brief review of literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:62-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vaira D, Dowsett JF, Hatfield AR, Cairns SR, Polydorou AA, Cotton PB, Salmon PR, Russell RC. Is duodenal diverticulum a risk factor for sphincterotomy? Gut. 1989;30:939-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mohammad Alizadeh AH, Afzali ES, Shahnazi A, Mousavi M, Doagoo SZ, Mirsattari D, Zali MR. ERCP features and outcome in patients with periampullary duodenal diverticulum. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2013;2013:217261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Karayiannakis AJ, Bolanaki H, Courcoutsakis N, Kouklakis G, Moustafa E, Prassopoulos P, Simopoulos C. Common bile duct obstruction secondary to a periampullary diverticulum. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:523-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cagir Y, Durak MB, Simsek C, Yuksel I. Effect of periampullary diverticulum morphology on ERCP cannulation and clinical results. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2025;60:292-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ishikawa-Kakiya Y, Shiba M, Maruyama H, Kato K, Fukunaga S, Sugimori S, Otani K, Hosomi S, Tanaka F, Nagami Y, Taira K, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe T, Fujiwara Y. Risk of pancreatitis after pancreatic duct guidewire placement during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhang D, Man X, Li L, Tang J, Liu F. Radiocontrast agent and intraductal pressure promote the progression of post-ERCP pancreatitis by regulating inflammatory response, cellular apoptosis, and tight junction integrity. Pancreatology. 2022;22:74-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Suda K, Mizuguchi K, Matsumoto M. A histopathological study on the etiology of duodenal diverticulum related to the fusion of the pancreatic anlage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:335-338. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Isogai M. Pathophysiology of severe gallstone pancreatitis: A new paradigm. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:614-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 21. | Winder JS, Juza RM, Alli VV, Rogers AM, Haluck RS, Pauli EM. Concomitant laparoscopic cholecystectomy and antegrade wire, rendezvous cannulation of the biliary tree may reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis events. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:3216-3222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mukai S, Takeyama Y, Itoi T, Ikeura T, Irisawa A, Iwasaki E, Katanuma A, Kitamura K, Takenaka M, Hirota M, Mayumi T, Morizane T, Yasuda I, Ryozawa S, Masamune A. Clinical Practice Guidelines for post-ERCP pancreatitis 2023. Dig Endosc. 2025;37:573-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/