Published online Nov 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.111117

Revised: August 21, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: November 16, 2025

Processing time: 143 Days and 22.8 Hours

Left colon cancer surgery relies on laparoscopic hemicolectomy, with digestive tract reconstruction critical. End-to-side anastomosis (ESA) and side-to-side anastomosis (SSA) anastomoses are common, but their comparative outcomes, especially in splenic flexure handling and efficacy, need clarification. This study compares ESA and SSA to guide surgical practice.

To compare the clinical outcomes of laparoscopically assisted left hemicolectomy with ESA and SSA.

A total of 334 patients were included, with 105 patients from the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University and 229 patients from the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, between January 1, 2012, and May 31, 2020. The patients were divided into two groups: 146 cases in the ESA group and 188 cases in the SSA group. Clinical data from both groups were compared, and the survival prognosis was followed up.

The operation time for the ESA group was significantly shorter than that of the SSA group (197.1 ± 57.7 minutes vs 218.6 ± 67.5 minutes, χ2 = 4.298, P = 0.039). There were no significant differences between the two groups in intraoperative blood loss, postoperative pain score at 48 hours, time to first bowel movement, number of lymph nodes dissected, or postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage, bleeding, stenosis. and adhesive intestinal obstruction at 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months (P > 0.05). Specifically, the incidence of complications like anastomotic leakage was 2.1% in the ESA group vs 4.3% in the SSA group (P = 0.264). The 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate was 66.4% for the ESA group and 63.9% for the SSA group (P = 0.693). There were no significant differences in the overall survival rate between the two groups. The incidence of splenic laceration was sign

Both laparoscopically assisted left hemicolectomy with ESA and SSA are feasible and offer comparable long-term outcomes. ESA may reduce the need for splenic flexure dissociation, particularly when the tumor is located at the descending colon or its junction with the sigmoid colon, and especially in obese patients, elderly individuals with multiple complications, or those with severe adhesions in the splenic flexure of the surgical field.

Core Tip: Both laparoscopically assisted left hemicolectomy with end-to-side anastomosis (ESA) and side-to-side anastomosis are feasible and offer comparable long-term outcomes. ESA may reduce the need for splenic flexure dissociation, particularly when the tumor is located at the descending colon or its junction with the sigmoid colon.

- Citation: Li F, Xie YL, Xu D, Lu CH, Wu JW, Ma JX, Guan GX, Wang HX. Comparison of different anastomosis methods in laparoscopically assisted left hemicolectomy for colon cancer. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(11): 111117

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i11/111117.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i11.111117

Colon cancer is among the most prevalent digestive tract tumors, with the incidence of colorectal cancer ranking third in malignant tumors worldwide[1]. Currently, complete mesocolic excision (CME) serves as the primary treatment for colon cancer. CME, as a surgical technique, involves the sharp dissection of the colon's mesentery from the posterior peritoneum (parietal peritoneum), enabling full exposure of the colon artery's root to ensure optimal clearance of regional lymph nodes, ultimately improving patient survival and prognosis[2,3]. Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer has become the mainstream approach, with its proportion steadily increasing. However, there is no international consensus on the extent and nomenclature of left hemicolectomy. The resection extent of left hemicolectomy encompasses the left 1/2 or 1/3 transverse colon (TC) and its corresponding mesentery, descending colon (DC) and its mesentery, descending-sigmoid junction colon (DSC) and its mesentery, and a portion of the sigmoid colon (SC) and its mesentery[4]. Digestive tract reconstruction is crucial for completing the operation and can be performed under direct vision or laparoscopy. The side-to-side anastomosis (SSA) requires more flexible and relaxed intestines, while the end-to-side anastomosis (ESA) does not necessarily necessitate the dissection of the splenic flexion of the colon (SFC), making it particularly suitable for patients with obesity or complicated adhesions of SFC. However, there is currently a limited comparison between these two surgical anastomosis methods in left hemicolectomy[5,6]. In this study, we compared the clinical outcomes and prognosis of left hemicolectomy using ESA and SSA to determine the more effective anastomosis approach.

From January 1, 2012 to May 31, 2020, a retrospective analysis was conducted on 105 patients who underwent laparoscopic left hemicolectomy at the Department of Colorectal Tumor Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, and 229 patients from the Department of Colorectal Tumor Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University. All patients had pathologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the left colon and were in TNM stage II or III. Based on the digestive tract reconstruction anastomosis method, patients were divided into group ESA (146 cases, 43.7%) and group SSA (188 cases, 56.3%). Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Preoperative colonoscopy and pathological examination or imaging examination confirming colon cancer; (2) Tumor location at the SFC, DC, or DSC; (3) Tumor confined to the bowel wall without invasion of the retroperitoneum or surrounding organs; (4) Complete clinical data for patients; and (5) Digestive tract reconstruction using either ESA or SSA. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Extensive abdominal adhesion or need for emergency surgery; (2) Severe organ dysfunction rendering the patient unable to tolerate laparoscopic surgery; (3) Missing clinical data; and (4) Tumor invasion of the retroperitoneum and surrounding organs or intraoperative discovery of widespread peritoneal metastasis. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University and the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University [No. 2024 Scientific Research Ethics Examination Number (014)]. The need for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University and the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University.

The extent of lymph node dissection and the surgical approach were consistent across both groups. After general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the lithotomy position. Following disinfection and draping, a conventional five-trocar technique was utilized to access the abdominal cavity and perform a routine abdominal exploration. Tumor localization methods included preoperative electronic colonoscopy with Nano-carbon submucosal injection or intraoperative colonoscopy. In left hemicolectomy, the right retroperitoneum of the rectum was incised first to enter the Toldt space. Lymph node No. 253 and surrounding adipose tissue were removed depending on the tumor location (only No. 253 for tumors located in the DC or DSC; both No. 253 and No. 223 for tumors in the SFC). The abdominal aortic plexus was preserved, while the protection of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) depended on tumor location. The Toldt space was extended caudally, passing the sacral promontory. For tumors at the DSC, the dissection was performed downward to release tension in the mesocolon or shorten the SC when necessary. The Toldt space was then expanded cephalad, followed by SFC dissociation. The transverse mesocolon root was disconnected along the pancreatic tail surface, and the gastrocolic, diaphragm colonic, and splenocolic ligaments were transected. The DC and SC planes were promoted on both sides until reaching the middle of the TC. The omentum of the splenic flexure was removed from the inner side of the vascular arch. The left peritoneal trocar foramen was enlarged to 4-6cm or a median abdominal incision of 6-8 cm was made. The abdominal incision was protected from contamination, and the freed left colon was pulled out of the abdo

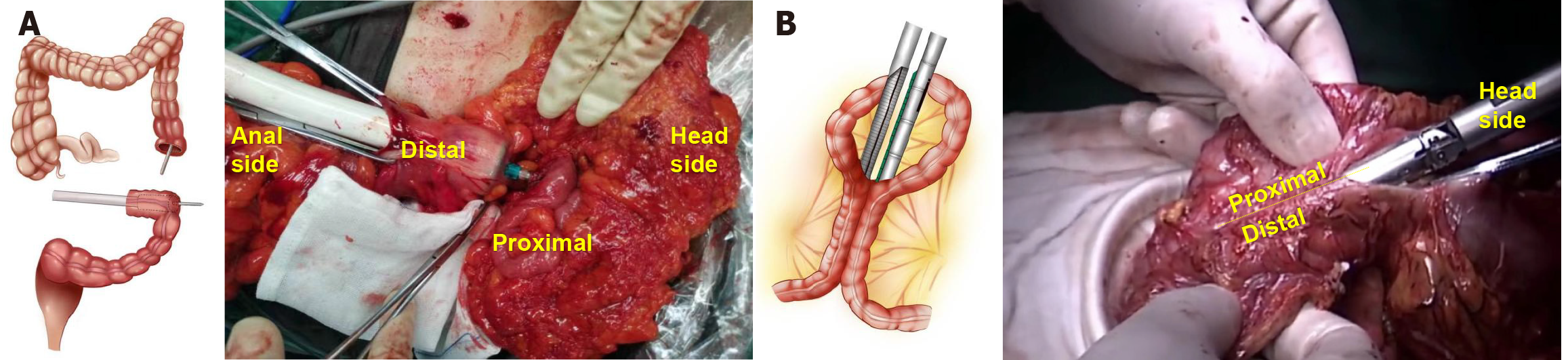

Using an electric knife, marks were made 10 cm from the proximal and distal colon of the tumor. In the ESA group, intestinal forceps were used to close the two marks, and a 25-29 mm nail drill was inserted into the upper incisal margin, with the stapler holder placed at the lower incision margin (location determined by the planned intestinal tube removal). The tubular stapler was activated to perform the ESA, and the insertion stump was closed using manual sutures or a linear cutting closure device. Finally, the anastomosis was reinforced with hand-sewn full-thickness sutures, and the mesocolon hiatus was closed (Figure 1A).

In the SSA group, after sufficient dissociation, the serosal surfaces of the distal and proximal colon (more than 10 cm away from the tumor) were approached and overlapped by 8 cm. Small incisions were made in the distal and proximal intestinal walls, and a 6 cm linear cutting closure device was inserted to complete the SSA. The common opening of the colonic anastomosis was closed with manual sutures or a linear cutting closure device. Lastly, the seromuscular layer was sewn to embed and reinforce the anastomosis, and the mesocolon hiatus was closed (Figure 1B).

All the surgical operations in this research were carried out by certified chief physicians in colorectal surgery.

To minimize selection bias and ensure methodological transparency, the choice between ESA and SSA was stand

Tumor location: ESA was preferentially selected for tumors located in the DC or DSC. These anatomical sites typically allow for sufficient bowel length and mobility to achieve a tension-free anastomosis without extensive SFM. SSA was predominantly used for tumors involving the SFC. Due to the fixed position of the splenic flexure and the need for a wider anastomotic diameter to accommodate potential tension, SSA was favored here to ensure adequate perfusion and reduce the risk of anastomotic stricture.

Intraoperative findings: Bowel mobility and tension: Intraoperatively, if manual assessment indicated that the proximal and distal bowel segments could be approximated without tension (verified by gentle traction), ESA was prioritized. If tension was evident or required extensive mobilization (e.g., due to adhesions or short bowel length), SSA was selected to leverage its ability to tolerate greater tension through overlapping bowel segments.

Bowel perfusion: Assessment of bowel perfusion via visual inspection (color, pulsation of mesenteric vessels) was mandatory. For segments with borderline perfusion, SSA was preferred to maximize the anastomotic surface area and reduce ischemia-related complications.

Adhesions: In cases of dense adhesions (e.g., due to prior surgery or inflammation), ESA was favored to minimize dissection extent, thereby reducing operative time and risk of iatrogenic injury (e.g., splenic or pancreatic trauma).

Patient-specific factors: (1) Body mass index: Patients with body mass index (BMI) > 28 kg/m² were more likely to undergo ESA, as the reduced need for SFM in this approach minimized the technical challenges associated with dissecting in obese abdominal cavities; and (2) Comorbidities: For patients with significant cardiopulmonary comorbidities, ESA was prioritized to shorten operative time and reduce anesthesia exposure, balancing oncologic safety with perioperative risk.

Surgeon judgment and standardization: All surgical decisions were made by Chief Physicican surgeons with > 15 years of laparoscopic experience, following a preoperative multidisciplinary team discussion.

The tumor's location was verified through preoperative colonoscopy, computed tomography (CT), and intraoperative observations. Data collected during the procedure included operation time, blood loss, length of bowel resection, postoperative 48-hour pain score (visual analogue scale, VAS), time to first bowel movement, postoperative hospital stay duration, number of lymph nodes dissected, and complications. Complications were classified as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (SIRS is defined by the presence of at least three of the following criteria: Body temperature > 38 °C or < 36 °C, heart rate > 90 beats per minute, respiratory rate > 20 breaths per minute or PaCO2 < 32 mmHg, and white blood cell count > 12000 cells/μL or < 4000 cells/μL or > 10% immature band forms), anastomotic leakage (defined as a defect in the intestinal wall at the anastomotic site, resulting in communication between intra- and extraluminal compartments)[7], anastomotic stenosis (defined as a condition where the anastomotic site (the connection point between two segments of the bowel such as in coloanal, colorectal, or ileoanal anastomosis) becomes narrowed, leading to a reduction in the lumen diameter and potentially resulting in symptoms such as difficulty in defecation, abdominal pain)[8], anastomotic bleeding, urinary injury, pancreatic injury, splenic laceration, and adhesive intestinal obstruction within 6, 12, and 24 months following surgery. The length of the intestinal excision was determined based on the principle of radical tumor resection, ensuring that the distal and proximal bowel segments were at least 10 cm away from the tumor. Length measurements were reported according to postoperative pathology results. The primary tumor size was defined as the tumor's maximum diameter. Infection was identified if antibiotics were administered for more than three days post-surgery. Urinary injury, pancreatic injury, and splenic laceration were identified by reviewing and analyzing postoperative videos. Anastomotic leakage was diagnosed via clinical signs (abdominal pain, fever, etc.) combined with contrast-enhanced CT or the presence of fecal-like material drainage from abdominal or pelvic drainage tubes. Anastomotic stenosis was diagnosed using clinical symptoms (obstruction) and endoscopic evaluation (when clinically indicated). Adhesive obstruction was confirmed via clinical symptoms such as paroxysmal abdominal pain, or imaging (CT), along with the exclusion of other etiologies. Postoperative follow-up was conducted through outpatient visits or telephone calls to record patient survival and recurrence rates. The date of the last follow up was December 31, 2022.

We utilized SPSS 23.0 software on Windows to analyze the collected data. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. For measurement data adhering to a normal distribution, we employed an independent sample t-test to compare the differences between groups. Enumeration data were analyzed using the χ2 test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of patient center (χ2 = 0.858, P = 0.354), age (χ2 = 0.183, P = 0.669), sex (χ2 = 0.001, P = 0.991), BMI (χ2 = 3.728, P = 0.054), TNM stage (χ2 = 0.072, P = 0.789), tumor location (χ2 = 3.171, P = 0.075), histological differentiation (χ2 = 0.652, P = 0.419), IMA dissection (χ2 = 2.569, P = 0.109), size of primary tumor (χ2 = 2.414, P = 0.12), preoperative intestinal obstruction (χ2 = 0.003, P = 0.96), carcinoembryonic antigen (χ2 = 0.795, P = 0.373), hemoglobin (χ2 = 3.495, P = 0.062), and the status of postoperative chemotherapy at six months (χ2 = 0.032, P = 0.858) (Table 1).

| Parameter | Group ESA | Group SSA | χ² | P value |

| n = 334 | 146 (43.7) | 188 (56.3) | ||

| Age (year) | 0.183 | 0.669 | ||

| ≤ 60 | 71 (48.6) | 87 (46.3) | ||

| > 60 | 75 (51.4) | 101 (53.7) | ||

| Sex | 0.001 | 0.991 | ||

| Male | 90 (61.6) | 116 (62.7) | ||

| Female | 56 (38.4) | 72 (38.3) | ||

| Patient center | 0.858 | 0.354 | ||

| Xiamen | 42 (28.8) | 63 (33.5) | ||

| Fuzhou | 104 (71.2) | 125 (66.5) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 3.728 | 0.054 | ||

| ≤ 22 | 56 (38.4) | 92 (48.9) | ||

| > 22 | 90 (61.6) | 96 (51.1) | ||

| Tumor location | 3.171 | 0.075 | ||

| Descending | 39 (26.7) | 47 (36.7) | ||

| Descending-sigmoid junction | 107 (73.3) | 81 (63.3) | ||

| TNM stage | 0.072 | 0.789 | ||

| II | 86 (58.9) | 108 (57.4) | ||

| III | 60 (41.1) | 80 (42.6) | ||

| Histological differentiation | 0.652 | 0.419 | ||

| Medium/high | 128 (87.7) | 159 (84.6) | ||

| Low/mucinous/signet ring cell carcinoma | 18 (12.3) | 29 (15.4) | ||

| Size of primary tumor (cm) | 2.414 | 0.12 | ||

| ≤ 5.0 | 102 (69.9) | 116 (61.7) | ||

| > 5.0 | 44 (30.1) | 72 (38.3) | ||

| High ligation inferior mesenteric artery | 2.569 | 0.109 | ||

| Yes | 75 (51.4) | 80 (42.6) | ||

| No | 71 (48.6) | 108 (57.4) | ||

| Preoperative intestinal obstruction | 0.003 | 0.96 | ||

| Yes | 23 (15.8) | 30 (16.0) | ||

| No | 123 (84.2) | 158 (84.0) | ||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.795 | 0.373 | ||

| ≤ 5.0 | 91 (62.3) | 126 (67.0) | ||

| > 5.0 | 55 (37.7) | 62 (33.0) | ||

| Hb (g/L) | 3.495 | 0.062 | ||

| ≤ 10 | 9 (6.2) | 23 (12.2) | ||

| > 10 | 137 (93.8) | 165 (87.8) | ≤ 0.001 | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy (half a year) | 0.032 | 0.858 | ||

| Yes | 77 (52.7) | 101 (53.7) | ||

| No | 69 (47.3) | 87 (46.3) |

The operation time for the ESA group was significantly shorter than that of the SSA group (197.1 ± 57.7 vs 218.6 ± 67.5, χ2 = 4.298, P = 0.039). However, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of bowel resection length (20.1 ± 5.4 vs 19.8 ± 5.5, χ2 = -0.331, P = 0.741), blood loss (73.1 ± 35.9 vs 70.5 ± 30.3, χ2 = -0.703, P = 0.482), postoperative 48-hour pain score (VAS) (4.0 ± 1.2 vs 4.1 ± 1.2, χ2 = 0.213, P = 0.832), time to first postoperative bowel movement (3.1 ± 0.7 vs 3.2 ± 0.8, χ2 = 0.841, P = 0.401), length of postoperative hospital stay (10.8 ± 6.0 vs 11.3 ± 5.0, χ2 = -0.64, P = 0.523), and number of lymph nodes dissected (22.0 ± 11.5 vs 24.5 ± 12.6, χ2 = 1.82, P = 0.070). No perioperative deaths occurred in either group, and all tumor margins were negative (Table 2).

| Parameter | Group ESA | Group SSA | t | P value |

| n = 334 | 146 (43.7) | 188 (56.3) | ||

| Operation time (minute) | 197.1 ± 57.7 | 218.6 ± 67.5 | 4.298 | 0.039 |

| Length of bowel resection (cm) | 20.1 ± 5.4 | 19.8 ± 5.5 | -0.331 | 0.741 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 73.1 ± 35.9 | 70.5 ± 30.3 | -0.703 | 0.482 |

| Postoperative 48 hours pain score | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 0.213 | 0.832 |

| Postoperative first exhaust time (day) | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 0.841 | 0.401 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (day) | 10.8 ± 6.0 | 11.3 ± 5.0 | -0.64 | 0.523 |

| Lymph node dissection | 22.0 ± 11.5 | 24.5 ± 12.6 | 1.82 | 0.070 |

In the study, 23 cases of SIRS were observed in the ESA group, while 40 cases were found in the SSA group. The difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.638, P = 0.201). In the ESA group, there were 3 cases of anastomotic bleeding, 3 cases of anastomotic leakage, 2 cases of anastomotic stenosis, and 3 cases of adhesive intestinal obstruction (within 6 months). In comparison, the SSA group had 9 cases of anastomotic bleeding, 8 cases of anastomotic leakage, 4 cases of anastomotic stenosis, and 4 cases of adhesive intestinal obstruction. No significant differences were found in anastomotic bleeding (χ2 = 1.771, P = 0.183), anastomotic leakage (χ2 = 1.249, P = 0.264), anastomotic stenosis (χ2 = 0.268, P = 0.605), or adhesive intestinal obstruction occurring within 6 months (χ2 = 0.022, P = 0.882), 12 months (χ2 = 0.014, P = 0.906), or 24 months (χ2 = 1.074, P = 0.300) between the two groups. In the ESA group, there was 1 case of urinary injury and 1 case of pancreatic tail injury. In the SSA group, 7 cases of splenic laceration and hemorrhage, 4 cases of pancreatic tail injury, and 3 cases of urinary injury were reported. No significant differences were observed in the incidence of urinary injury (χ2 = 0.576, P = 0.448) or pancreatic injury (χ2 = 1.160, P = 0.281). However, a statistically significant difference was found in the occurrence of splenic laceration (χ2 = 5.553, P = 0.018) (Table 3).

| Parameter | Group ESA | Group SSA | χ² | P value |

| n = 334 | 146 (43.7) | 188 (56.3) | ||

| SIRS | 23 (15.8) | 40 (21.3) | 0.638 | 0.201 |

| Anastomotic bleeding | 3 (2.1) | 9 (4.8) | 1.771 | 0.183 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 3 (2.1) | 8 (4.3) | 1.249 | 0.264 |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.1) | 0.268 | 0.605 |

| Urinary injury | 1 (0.7) | 3 (1.6) | 0.576 | 0.448 |

| Pancreatic injury | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.1) | 1.160 | 0.281 |

| Splenic laceration | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.7) | 5.553 | 0.018 |

| Adhesive intestinal obstruction1 | 3 (1.4) | 4 (3.3) | 0.022 | 0.882 |

| Adhesive intestinal obstruction2 | 5 (3.4) | 6 (3.2) | 0.014 | 0.906 |

| Adhesive intestinal obstruction3 | 9 (6.2) | 7 (3.7) | 1.074 | 0.300 |

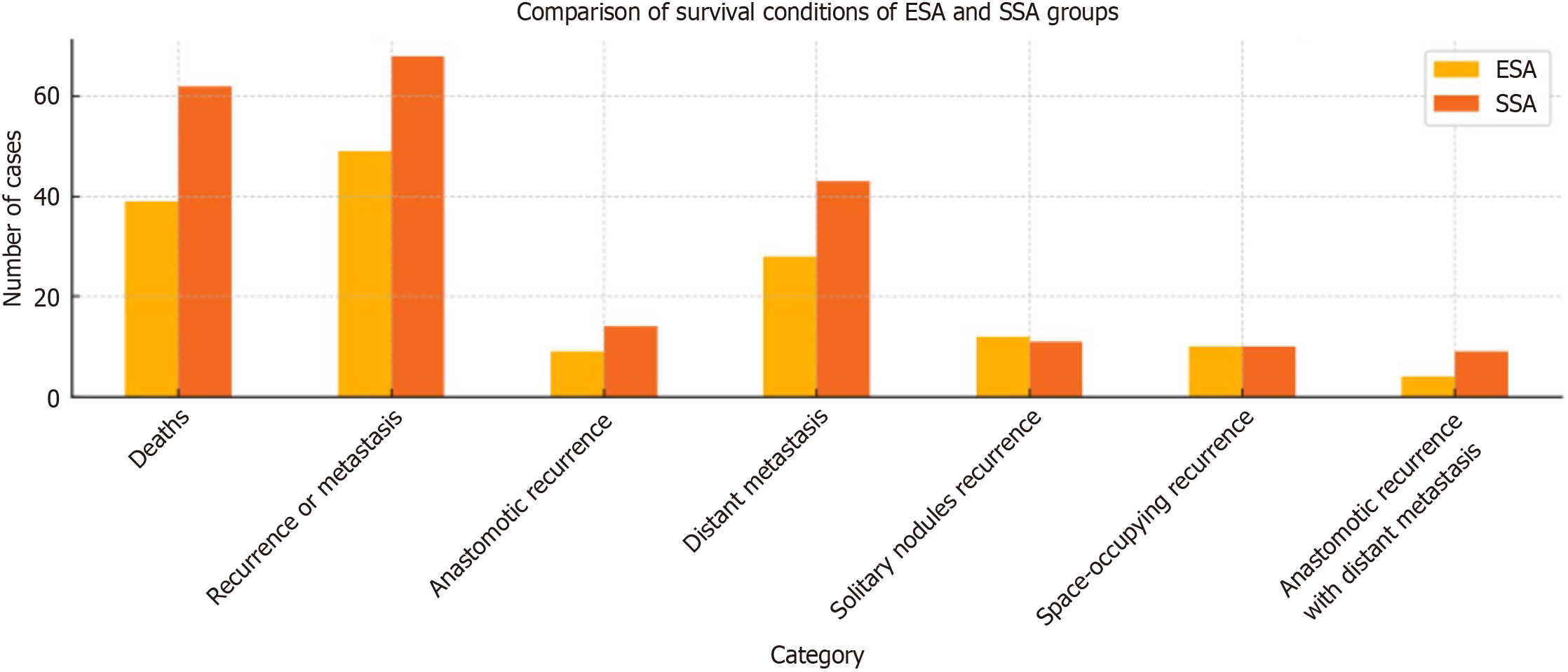

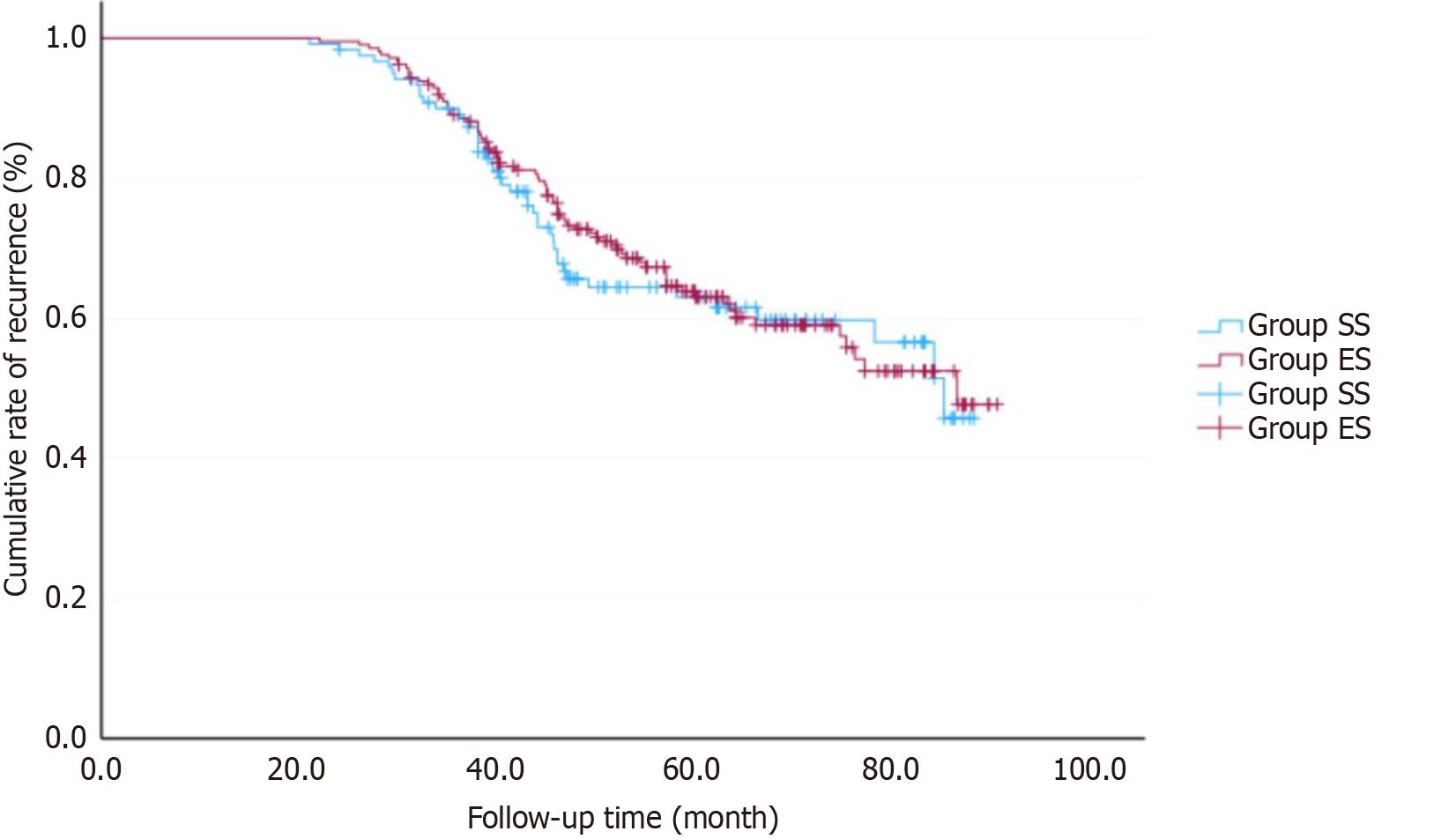

The follow-up period lasted for an average of 54.6 months, ranging from 21 to 90 months. Patients in Stage IIb-III underwent CAPEOX chemotherapy (Oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 on day 1; Capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 twice daily from day 1 to day 14) within 6 months after surgery. By May 2020, in the ESA group, 39 patients (26.7%) had died, and 49 patients (33.6%) experienced recurrence or metastasis, including 9 cases of anastomotic recurrence, 28 cases of distant metastasis, 12 cases of solitary nodules recurrence in the surgical area, 10 cases of space-occupying recurrence in the surgical area with distant metastasis, and 4 cases of anastomotic recurrence with distant metastasis. In the SSA group, there were 62 deaths (33.0%), and 68 cases (36.2%) of recurrence or metastasis, which included 14 cases of anastomotic recurrence, 43 cases of distant metastasis, 11 cases of solitary nodules recurrence in the surgical area, 10 cases of space-occupying recurrence in the surgical area with distant metastasis, and 9 cases of anastomotic recurrence with distant metastasis (Figure 2). The 5-year overall survival rate for all patients was 69.8% (233/334). In the ESA group, the 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate was 66.4% (97/146), while the 5-year DFS rate in the SSA group was 63.8% (120/188). There was no significant difference between the two groups (χ2 = 0.156, P = 0.693) (Figure 3).

Left hemicolectomy presents a unique challenge in laparoscopic colorectal surgery due to the anatomical complexities of the left colon and its mesentery, especially when dealing with tumors located at the DC, DSC, or SFC[9]. The difficulty lies in the need to dissect the left colonic artery, as well as the requirement for splenic flexure dissociation (SFD) to achieve adequate exposure and ensure sufficient resection margins. Consequently, the risk of complications such as splenic laceration, pancreatic injury, mesenteric injury, and the incidence of conversion to open surgery are heightened[10,11]. These challenges are particularly significant in patients with advanced disease or obesity, where dissection becomes more difficult due to adhesions and altered anatomical planes[12].

In this study, we compared two widely utilized techniques for digestive tract reconstruction following laparoscopic left hemicolectomy: ESA and SSA. While both methods offer comparable long-term oncologic outcomes, there were notable differences in terms of intraoperative factors and postoperative complications. One key finding was the significantly shorter operation time associated with ESA, which was primarily attributed to the reduced need for SFD when tumors are located at the DC or DSC (ESA group vs SSA group: 197.1 ± 57.7 minutes vs 218.6 ± 67.5 minutes, P = 0.039). we clarify that reduced operative time may benefit high-risk patients (e.g., elderly, comorbid) by minimizing anesthesia exposure, even in the absence of differences in complications or hospital stay. In these cases, ESA allows for a more direct and less technically demanding approach to the anastomosis, reducing the need for extensive dissection. This, in turn, lowers the risk of intraoperative complications such as splenic injury or excessive mesenteric excision, which are common when SSA is performed. By avoiding unnecessary SFD, ESA can potentially offer a safer and quicker surgical option. The retrospective analysis of surgical video recordings revealed that splenic laceration occurred in 7 cases in the SSA group compared to 0 in the ESA group, while pancreatic injury was observed in 4 cases in the SSA group vs 1 in the ESA group. The contributing factors include patient obesity, pathological adhesions, anatomical proximity of the pancreas, and advanced tumor invasion. The increased risk of splenic and pancreatic injuries in the SSA group is likely attributable to the surgical procedure involving greater dissection of the splenic flexure. Excessive mesenteric excision can impair anastomotic blood supply, and the local vascular anatomy of the left hemicolon, including the branching morphology of the IMA, Griffiths key point, Riolan arch, and Sudeck's danger zone, must be carefully considered, as their absence may compromise blood flow to the anastomosis[13]. The Riolan arch, a rigid barrier encountered during dissociation of the SFC, requires ligation, typically between the transverse mesocolon and descending mesocolon[14]. However, we emphasize that SFM remains essential for SFC tumors or when tension-free anastomosis cannot be achieved. This makes the procedure particularly challenging for less experienced surgeons, thereby prolonging the learning curve for laparoscopic left hemicolectomy[15].

It has been reported that the rate of para-arterial lymph node metastasis around colon cancer located more than 10 cm from the intestine is only 1%-2%[16]. Lymph node No. 253, situated between the origin of the IMA and the left colic artery, is distributed along the IMA[17]. A retrospective study found metastases in No.223 (7.3%) and No. 253 (2.4%) lymph nodes in SFC carcinoma, in No. 253 (4.1%) in DC carcinoma, and in No. 253 (5.9%) in sigmoid carcinoma[18]. In our two centers, No. 253 (4.5%) and No. 223 (8.3%) lymph nodes were dissected during D3 radical resection for SFC, while No. 253 (4.0% vs 5.6%) lymph nodes were excised for both DC and DSC tumors. The IMA gives rise to the left colic artery, sigmoid artery, and superior rectal artery. To preserve the blood supply to the anastomosis, only the left colic artery was ligated, and the IMA was not ligated at its root during the dissection of No. 253 lymph nodes. Therefore, the IMA is typically not ligated in left hemicolectomy, particularly for SFC tumors. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding high ligation of the IMA (P = 0.109).

The recovery of intestinal function post-surgery is influenced by various factors, including age, anesthesia method, digestive tract reconstruction approach, and nutritional status[19]. Some studies suggest that ESA with a tubular stapler aligns more closely with the physiological structure of the intestines[20]. Intestinal peristalsis results from the coordinated contraction of annular and longitudinal muscles. In SSA, the larger common opening and longer continuous cutting may increase the risk of chronic pseudo-ileus or dyskinesia. In our study, no significant differences were observed in preoperative intestinal obstruction (at 6, 12, and 24 months) (P > 0.05). ESA, with its circular terminal incision, facilitates faster recovery of postoperative intestinal function. Literature reports suggest that SSA has an anastomotic width of 40-60 mm, which is broader than ESA's 25-29 mm, potentially aiding intestinal content passage[21]. However, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of postoperative first exhaust time (P = 0.401) or pain scores at 48 hours (P = 0.05), indicating that ESA does not lead to increased postoperative discomfort. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in anastomotic stenosis (P = 0.832) or postoperative adhesive intestinal obstruction (P = 0.882), suggesting that both anastomotic techniques are feasible.

In our unit, ESA is routinely reinforced with eight absorbable sutures (The practice of suturing and reinforcing the anastomosis with absorbable sutures is a technique used by our surgical team based on internal protocols to enhance the security of the anastomosis and prevent leakage)[22], while SSA is reinforced only at the seromuscular layer. A case of stenosis in the SSA group, attributed to excessive embedding of the seromuscular layer, improved after endoscopic balloon dilation. The lack of routine postoperative colonoscopy limits the accuracy of stenosis detection. However, we routinely perform a colonoscopic review at approximately 10-12 months. It means that stenosis rates may be underestimated, particularly in asymptomatic patients. Postoperative adhesive intestinal obstruction occurred in 3 cases in the ESA group and 4 cases in the SSA group, all of which resolved with conservative treatment. The more extensive dissection required for SSA increases the risk of postoperative adhesion, which can lead to recurrent obstruction. Our findings suggest that adhesive ileus recurs more frequently in SSA cases, requiring multiple hospitalizations. However, there were no significant differences in adhesive intestinal obstruction rates after surgery at 6, 12, and 24 months (P > 0.05). Additionally, studies have suggested that the length of the anastomosis may influence the incidence of anastomotic leakage[23]. In our study, the incidence of anastomotic leakage was 2.1% in both the ESA and SSA groups, with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.264). Overall, the incidence of complications associated with ESA and SSA anastomosis in left hemicolectomy was similar.

Both ESA and SSA demonstrated similar DFS (66.4% vs 63.8%) and OS (73.2% vs 67.0%), The 26%-33% mortality rate in the cohort is primarily due to the inclusion of stage II-III colorectal cancer patients. This retrospective study is limited by the lack of postoperative colonoscopy follow-up of the anastomotic sites, and the findings should be corroborated by larger sample sizes. Both ESA and SSA are feasible and effective techniques for digestive tract reconstruction in laparoscopic-assisted left hemicolectomy. The selection of the appropriate anastomosis technique should be made with careful consideration, especially in settings with limited resources or when minimizing operative risks is a priority.

In conclusion, using ESA or SSA for digestive tract reconstruction in laparoscopic-assisted left hemicolectomy is feasible, with no significant differences in long-term outcomes between the two techniques. When the tumor is located at the DC or DSC, especially in patients who are obese, elderly with multiple complications, or have severe adhesions in the splenic flexure of the surgical field, ESA may reduce the need for SFD.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12654] [Article Influence: 6327.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Jeon Y, Nam KH, Choi SW, Hwang TS, Baek JH. Comparison of Long-Term Oncologic Outcomes Between Surgical T4 and T3 in Patients Diagnosed With Pathologic Stage IIA Right Colon Cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:931414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee JM, Chung T, Kim KM, Simon NSM, Han YD, Cho MS, Hur H, Lee KY, Kim NK, Lee SB, Kim GR, Min BS. Significance of Radial Margin in Patients Undergoing Complete Mesocolic Excision for Colon Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:488-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Egred M, Brilakis ES. Excimer Laser Coronary Angioplasty (ELCA): Fundamentals, Mechanism of Action, and Clinical Applications. J Invasive Cardiol. 2020;32:E27-E35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rajan R, Arachchi A, Metlapalli M, Lo J, Ratinam R, Nguyen TC, Teoh WMK, Lim JT, Chouhan H. Ileocolic anastomosis after right hemicolectomy: stapled end-to-side, stapled side-to-side, or handsewn? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37:673-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang XQ, Tang RX, Zhang CF, Xia MY, Shuai LY, Tang H, Ji GY. Comparison study of two anastomosis techniques in right hemicolectomy: a systematic review and pooling up analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2025;40:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A, Holm T, Wong WD, Tiret E, Moriya Y, Laurberg S, den Dulk M, van de Velde C, Büchler MW. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010;147:339-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 1102] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 8. | Kraenzler A, Maggiori L, Pittet O, Alyami MS, Prost À la Denise J, Panis Y. Anastomotic stenosis after coloanal, colorectal and ileoanal anastomosis: what is the best management? Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:O90-O96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Morrison JJ, Madurska MJ, Romagnoli A, Ottochian M, Adnan S, Teeter W, Kuebler T, Hoehn MR, Brenner ML, DuBose JJ, Scalea TM. A Surgical Endovascular Trauma Service Increases Case Volume and Decreases Time to Hemostasis. Ann Surg. 2019;270:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jamali FR, Soweid AM, Dimassi H, Bailey C, Leroy J, Marescaux J. Evaluating the degree of difficulty of laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Arch Surg. 2008;143:762-7; discussion 768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baixauli J, Cienfuegos JA, Martinez Regueira F, Pastor C, Justicia CS, Valentí V, Rotellar F, Hernández Lizoáin JL. Conversion to Open Surgery in Laparoscopic Colorectal Cancer Resection: Predictive Factors and its Impact on Long-Term Outcomes. A Case Series Study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2021;32:28-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu S, Gosavi R, Chung YC, Teoh W, Nguyen TC, Ooi G, Narasimhan V. Obesity Selectively Increases Intraoperative Risk in Left-Sided Colon Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2025;40:188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nakao T, Shimada M, Yoshikawa K, Tokunaga T, Nishi M, Kashihara H, Takasu C, Wada Y, Yoshimoto T, Yamashita S, Iwakawa Y. Vascular variations encountered during laparoscopic surgery for transverse colon, splenic flexure, and descending colon cancer: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Surg. 2022;22:170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Murono K, Nozawa H, Kawai K, Sasaki K, Emoto S, Kishikawa J, Ishii H, Yokoyama Y, Abe S, Nagai Y, Anzai H, Sonoda H, Ishihara S. Vascular anatomy of the splenic flexure: a review of the literature. Surg Today. 2022;52:727-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yamamoto M, Okuda J, Tanaka K, Kondo K, Asai K, Kayano H, Masubuchi S, Uchiyama K. Evaluating the learning curve associated with laparoscopic left hemicolectomy for colon cancer. Am Surg. 2013;79:366-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen MZ, Tay YK, Prabhakaran S, Kong JC. The management of clinically suspicious para-aortic lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2023;19:596-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zheng B, Wang N, Wu T, Qiao Q, Gong L, Zhou S, Zhang B, Yang Y, Wang K, Zhai Y, He X. [Application value of the clearance of No.253 lymph nodes with priority to fascial space and preserving left colic artery in laparoscopic radical proctectomy]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;21:673-677. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Cai D, Guan G, Liu X, Jiang W, Chen Z. [Clinical analysis on lymph node metastasis pattern in left-sided colon cancers]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2016;19:659-663. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Irani JL, Hedrick TL, Miller TE, Lee L, Steinhagen E, Shogan BD, Goldberg JE, Feingold DL, Lightner AL, Paquette IM. Clinical practice guidelines for enhanced recovery after colon and rectal surgery from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:5-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Oh HK, Ihn MH, Son IT, Park JT, Lee J, Kim DW, Kang SB. Factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery programs after laparoscopic colon cancer surgery: a single-center retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1086-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Huang ZD, Li DM, Li XP, Li YN, Zhou J. [Comparative study of clinical effect of different anastomosis methods in laparoscopic assisted right hemicolectomy]. Xiaohua Zhongliu Zazhi. 2020;12:147-150. |

| 22. | Meng C, Li Y, Shi JY, Wei PJ, Song JN, Wu GC, Yao HW, Zhang ZT. [Transanal endoscopic reinforcing suture of anastomosis during surgery for mid-low rectal cancer: a single-center study]. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2023;43:1141-1151. |

| 23. | Cheng KW, Wang GH, Shu KS, Zheng M, Liu HX, Ma DH. [A Retrospective Controlled Study of Two Mechanical Anastomosis Methods in Laparoscopically Assisted Right Colon Cancer Surgery]. Zhongguo Puwaijichu Yu Linchuang Zazhi. 2019;26:856-860. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/