Published online Oct 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.109380

Revised: June 12, 2025

Accepted: September 2, 2025

Published online: October 16, 2025

Processing time: 160 Days and 20 Hours

According to the guidelines in the United States, individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer should be screened at the age of 40 years. Data on the prevalence of adenomas and sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) in individuals aged 40-49 years in Japan are lacking.

To investigate the effect of family history on the detection of adenomas and SSLs during colonoscopy in Japan.

This retrospective, single-center cohort study included individuals aged 40-79 years who underwent colonoscopy by expert endoscopists with an adenoma detection rate (ADR) ≥ 40% between 2021 and 2024. The ADR and adenoma plus SSL detection rate (ASDR) were investigated according to age. Multivariable analyses were performed to examine the effects of first-degree family history of colorectal cancer, fecal immunochemical test, and sex on the ADR and ASDR for each age group. A binomial logistic regression model was used.

In 10248 participants, the overall ADR and ASDR were 53.6% and 59.1%, respectively. The ADR and ASDR increased with age. Among 2317 participants aged 40-49 years, the presence of a family history significantly increased the ADR (47.6% vs 38.2%). The odds ratio of a family history for the ADR adjusted by sex and fecal immunochemical test was 1.59 (95% confidence interval: 1.13-2.25). In contrast, there was no significant association between the ADR and family history in participants aged 50-59, 60-69, and 70-79 years. Similarly, a family history significantly increased the ASDR (58.0% vs 43.7%) in participants aged 40-49 years. The odds ratio of a family history for the ASDR was 1.92 (95% confidence interval: 1.36-2.71).

Participants with a family history exhibited significantly elevated ADR (47.6%) and ASDR (58.0%), in their 40s. Individuals with a family history should initiate colonoscopy at 40 years old.

Core Tip: Participants in their 40s with a family history showed a high adenoma detection rate (47.6%) when expert endoscopists performed colonoscopies using the latest endoscopic system. There was a significant increase in the adenoma detection rate in those with a family history compared to those without, among participants aged 40-49 years.

- Citation: Toyoshima O, Nishizawa T, Asano H, Mizutani M, Uozumi T, Fujimoto A, Sano M, Yoshida S, Hata K, Ebinuma H. Effect of family history on detection of adenomas and sessile serrated lesions in individuals aged 40s. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(10): 109380

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i10/109380.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i10.109380

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a fatal disease that occurs worldwide[1,2]. As CRCs mainly develop from conventional adenomas or sessile serrated lesions (SSLs), their removal prevents the development of CRC[3,4]. Colonoscopic screening can decrease the incidence and mortality of CRC[5]. First-degree relatives (FDRs) of patients with CRC have a three-to-six-fold increased risk of developing CRC, and therefore, early screening colonoscopy has been recommended for such individuals[6,7]. United States guidelines recommend that individuals with an FDR who had had CRC or a colorectal adenoma before the age of 60 years, or in two or more FDRs regardless of age, begin colonoscopic screening either at 40 years of age or at 10 years younger than the age of the index FDR[8]. Fuchs et al[9] reported the cumulative incidence of CRC among participants with and without a family history, and their data underpin average-risk screening programs and their recommendations to initiate screening at the age of 50 years. The cumulative incidence of CRC in participants with FDR history approaches the same threshold as those with no family history 10 years earlier, at age of 40 years[9]. Therefore, guidelines recommend early initiation of screening for individuals with a family history. However, little is known about the prevalence of colorectal neoplasia in individuals aged 40-49 years in Japan. Therefore, we analyzed the prevalence of colorectal neoplasia in young populations and the impact of FDR history.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic in Tokyo, Japan. Participants aged 40-79 years who underwent colonoscopy at our clinic between March 2021 and October 2024 were eligible for this study. Indications for colonoscopy included symptom evaluation, positive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) results, and screening and surveillance of colorectal polyps. Symptoms included hematochezia, abnormal bowel habits, and abdominal pain. Colonoscopy was performed by seven expert endoscopists with adenoma detection rates (ADRs) ≥ 40%. The ADR was inversely associated with the risks of interval CRC, advanced-stage interval CRC, and fatal interval CRC[10,11]. Hilsden et al[12] reported that endoscopists with an ADR of 39% or more had high accuracy. Patients with poor bowel preparation, incomplete cecal intubation, inflammatory bowel disease, or treatment purposes such as polypectomy or hemostasis were excluded. This study was approved by the Certified Institutional Review Board of the Yoyogi Mental Clinic on July 16, 2021 (Approval No. RKK227). We have published the study protocol on our clinic’s website (https://www.ichou.com/); thus, patients could opt out of the study if they desired. All the clinical investigations were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The endoscopy system used was an Olympus EVIS X1 (CV-1500; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The colonoscopy models used were CF-EZ1500D, CF-XZ1200, CF-HQ290, CF-HQ290Z, CF-H290EC, PCF-H290Z, and PCF-PQ260 (Olympus Corp, Tokyo, Japan). Sedation was performed at the patient’s discretion. Midazolam, pethidine, and/or propofol were used[13]. Pancolonic chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine was used routinely[14]. Moreover, endoscopic observation was performed using white-light imaging and/or texture and color enhancement imaging[15-17]. All polyps diagnosed as adenomas or SSLs were resected during the colonoscopy. The diagnosis of polyps was made histologically based on the resected specimens. Endoscopic resection techniques include endoscopic mucosal resection and hot or cold polypectomy using snares or forceps[18]. Index colonoscopy was defined as the first colonoscopy performed during the patient’s lifetime. Bowel preparations were classified into four groups: (1) Grade A was considered good; (2) Grade B was average; (3) Grade C was marginal; and (4) Grade D was poor[19]. Patients with grade D preparations were excluded from this study.

Our electronic endoscopy reporting system was the T-File system (STS Medic, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) integrated into the electronic medical record system Qualis (BML, Inc., Sapporo, Japan)[20]. The endoscopy reporting system outputted the information for this study in a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States) file format. The background information included patient age, sex, colonoscopy indications, first-degree family history of CRC, endoscopist, endoscopy system, and bowel preparation. The outcome parameters were premalignant polyp detection rates such as the ADR and adenoma plus SSL detection rate (ASDR).

The ADR and ASDR were investigated according to age group. Age groups included 40-49 years, 50-59 years, 60-69 years, and 70-79 years. The Cochran-Armitage (CA) trend test was used to calculate the statistical significance of the ADR and ASDR trends across age groups. Multivariable analyses were performed to examine the effects of a first-degree family history of CRC on the ADR and ASDR for each age group. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using a binomial regression model and adjusted for the FIT results and sex. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Calculations were performed using Bell Curve for Excel, version 4.09 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

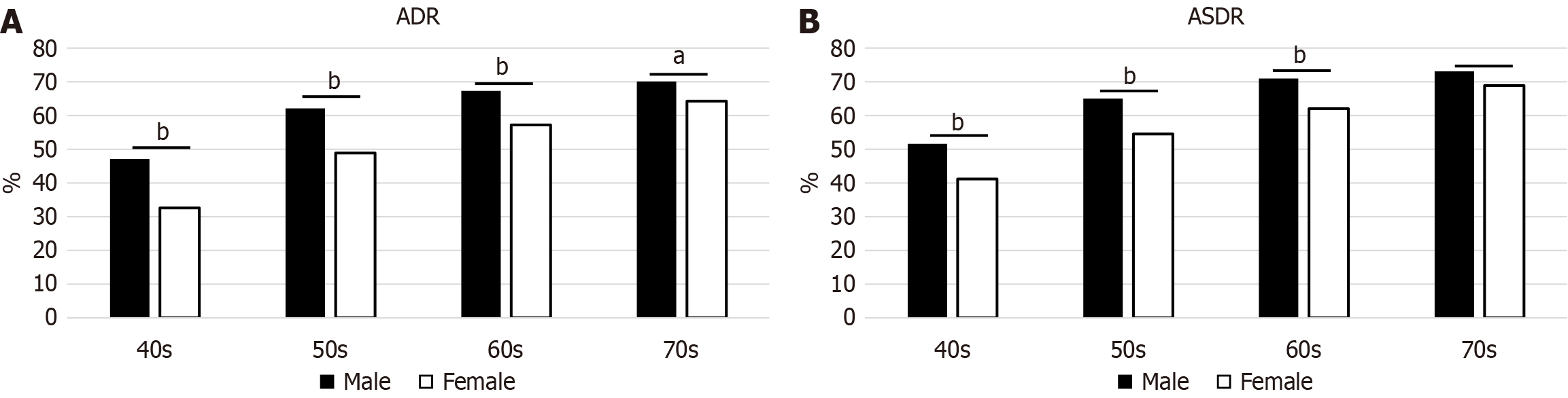

During the study period, 10753 consecutive patients aged 40-79 years who underwent colonoscopies performed by seven expert endoscopists were enrolled. Two patients with poor bowel preparation, 157 with inflammatory bowel disease, and 346 receiving treatments were excluded. Finally, 10248 participants were included in this study. The mean age was 57.1 years, and 44.8% were male (Table 1). The index colonoscopy rate showed a decreasing trend with age (P < 0.001, CA trend test). The overall ADR and ASDR were 53.6% and 59.1%, respectively. The ADR and ASDR by age and sex are shown in Figure 1, respectively. The ADR and ASDR showed an increasing trend with age (all P < 0.001). The ADR and ASDR were higher in men than in women in all age groups, except for the ASDR in those aged 70-79 years.

| All | 40s | 50s | 60s | 70s | |

| Number | 10248 | 2317 | 3564 | 2540 | 1827 |

| Mean age (years) | 57.1 | 45.2 | 54.6 | 64.0 | 74.0 |

| Male sex | 44.8 | 43.0 | 44.1 | 46.2 | 46.3 |

| Family history | 8.2 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 9.7 | 8.5 |

| Positive FIT | 13.2 | 18.9 | 14.1 | 10.3 | 10.1 |

| Index colonoscopy | 21.0 | 34.7 | 22.5 | 14.6 | 9.8 |

| ADR | 55.1 | 38.8 | 54.7 | 61.9 | 67.0 |

| ASDR | 59.0 | 44.5 | 58.5 | 65.2 | 69.7 |

The presence of a family history significantly increased the ADR (47.6% vs 38.2%) in patients aged 40-49 years. The OR of a family history of ADR adjusted by sex and FIT results was 1.59 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.13-2.25, P = 0.008]. In contrast, there was no significant association between the ADR and family history in participants aged 50-59 years, 60-69 years, and 70-79 years (Table 2). Similarly, a family history significantly increased the ASDR (58.0% vs 43.7%) in patients aged 40-49 years. The OR of a family history for the ASDR adjusted by sex and FIT results was 1.92 (95%CI: 1.36-2.71, P < 0.001, Table 3).

| Family history (-) | Family history (+) | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value1 | |

| 40s | 38.2 | 47.6 | 1.59 | 1.13-2.25 | 0.008 |

| 50s | 54.9 | 52.4 | 0.96 | 0.74-1.23 | 0.73 |

| 60s | 61.7 | 63.4 | 1.09 | 0.83-1.44 | 0.52 |

| 70s | 66.6 | 70.1 | 1.19 | 0.85-1.66 | 0.31 |

In this study, participants with a family history exhibited significantly elevated ADR (47.6%) and ASDR (58.0%) in their 40s. There were significant increases in ADR and ASDR in those with a family history compared to those without, particularly among those in their 40s. In Japan, annual FIT starting at 40 years of age has been adopted as a population-based CRC screening program[4]. Population-based colonoscopy screening is not recommended in Japan. Recently published guidelines by the American Gastroenterological Association suggest that individuals carrying mid-risk CRC probability should commence screening protocols at the age of 45 years, while those with exacerbated CRC risk owing to an FDR developing CRC should commence screening protocols at least 10 years prior to the age of CRC development within said relative or commence screening at the age of 40 years[21]. Our study supports the recommendation that patients with a family history should undergo screening colonoscopy at 40 years of age.

A recent meta-analysis showed that a family history of CRC in FDRs was associated with increased risk of adenoma (pooled OR = 1.67, 95%CI: 1.46-1.91)[22]. Furthermore, a sub-analysis by the number of FDRs was performed. Participants with two or more affected FDRs were at a particularly elevated risk (pooled OR = 4.18, 95%CI: 1.76-9.91), whereas patients with only one affected FDR were at a lower risk (pooled OR = 1.63, 95%CI: 1.35-1.96). The sub-analysis by age showed that family history was consistently associated with significant increases in ADRs in individuals aged over as well as under 50 years.

In contrast, our study showed a significant difference only in patients in their 40s with no significant differences observed in those in their 50s, 60s, or 70s. The rate of index colonoscopy decreased significantly with age (P < 0.001, CA trend test). When all the adenomas were removed during the index colonoscopy, they could not be detected during the second colonoscopy. Patients in their 50s, 60s, and 70s had low rates of index colonoscopy and may have previously undergone endoscopy and polypectomy. Differences in the index rates can cause bias, and the effect of family history may have been underestimated among participants in their 50s, 60s, and 70s.

When characterizing adenomas in young patients with a family history of CRC, the possible contribution of germline mutations should be considered. Representative genes include adenomatous polyposis coli, mutY DNA glycosylase, and genes involved in mismatch repair. These genes are respectively associated with familial adenomatous polyposis, mutY DNA glycosylase-associated polyposis, and Lynch syndrome[23]. New inherited CRC risk genes, including Axin 2, DNA polymerase epsilon, MutS homolog 3, and Nth like DNA glycosylase 1 have recently been identified[24]. Genetic predisposition could be an important direction for future studies. The strength of this study is that the endoscopists were limited to those with an ADR of 40% or more, and the latest endoscopic system, Olympus EVIS X1, was used. Colonoscopies were performed by experts using the newest system, providing highly accurate results and minimizing the risk of overlooking premalignant polyps. This study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective, single-center study. However, the medical data recordings were well-controlled. Second, the patient cohorts were limited. Third, cost analysis was not performed. A detailed cost-effectiveness analysis is a topic for future research.

Participants with a family history of CRC exhibited significantly elevated ADR (47.6%) and ASDR (58.0%) in their 40s. Individuals with a family history should initiate colonoscopic examinations at 40 years of age.

| 1. | Wu D, Song QY, Dai BS, Li J, Wang XX, Liu JY, Xie TY. Colorectal cancer early screening: Dilemmas and solutions. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:98760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tsukanov VV, Vasyutin AV, Tonkikh JL. Risk factors, prevention and screening of colorectal cancer: A rising problem. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:98629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 3. | He X, Hang D, Wu K, Nayor J, Drew DA, Giovannucci EL, Ogino S, Chan AT, Song M. Long-term Risk of Colorectal Cancer After Removal of Conventional Adenomas and Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:852-861.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saito Y, Oka S, Kawamura T, Shimoda R, Sekiguchi M, Tamai N, Hotta K, Matsuda T, Misawa M, Tanaka S, Iriguchi Y, Nozaki R, Yamamoto H, Yoshida M, Fujimoto K, Inoue H. Colonoscopy screening and surveillance guidelines. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:486-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3107] [Cited by in RCA: 3182] [Article Influence: 96.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Puente Gutiérrez JJ, Marín Moreno MA, Domínguez Jiménez JL, Bernal Blanco E, Díaz Iglesias JM. Effectiveness of a colonoscopic screening programme in first-degree relatives of patients with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e145-e153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Butterworth AS, Higgins JP, Pharoah P. Relative and absolute risk of colorectal cancer for individuals with a family history: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:216-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, Levin TR, Lieberman D, Robertson DJ. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1016-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 509] [Article Influence: 56.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Speizer FE, Willett WC. A prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1669-1674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in RCA: 1518] [Article Influence: 94.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger JE, Quinn VP, Ghai NR, Levin TR, Quesenberry CP. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1674] [Article Influence: 139.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Hilsden RJ, Rose SM, Dube C, Rostom A, Bridges R, McGregor SE, Brenner DR, Heitman SJ. Defining and Applying Locally Relevant Benchmarks for the Adenoma Detection Rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1315-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Burtea DE, Dimitriu A, Maloş AE, Săftoiu A. Current role of non-anesthesiologist administered propofol sedation in advanced interventional endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:981-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pohl J, Schneider A, Vogell H, Mayer G, Kaiser G, Ell C. Pancolonic chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine versus standard colonoscopy for detection of neoplastic lesions: a randomised two-centre trial. Gut. 2011;60:485-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Sakamoto T, Ikematsu H, Tamai N, Mizuguchi Y, Takamaru H, Murano T, Shinmura K, Sasabe M, Furuhashi H, Sumiyama K, Saito Y. Detection of colorectal adenomas with texture and color enhancement imaging: Multicenter observational study. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:529-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hiramatsu T, Nishizawa T, Kataoka Y, Yoshida S, Matsuno T, Mizutani H, Nakagawa H, Ebinuma H, Fujishiro M, Toyoshima O. Improved visibility of colorectal tumor by texture and color enhancement imaging with indigo carmine. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15:690-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tamai N, Horiuchi H, Matsui H, Furuhashi H, Kamba S, Dobashi A, Sumiyama K. Visibility evaluation of colorectal lesion using texture and color enhancement imaging with video. DEN Open. 2022;2:e90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dumoulin FL, Hildenbrand R. Endoscopic resection techniques for colorectal neoplasia: Current developments. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:300-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Ell C, Fischbach W, Bronisch HJ, Dertinger S, Layer P, Rünzi M, Schneider T, Kachel G, Grüger J, Köllinger M, Nagell W, Goerg KJ, Wanitschke R, Gruss HJ. Randomized trial of low-volume PEG solution versus standard PEG + electrolytes for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:883-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Toyoshima O, Nishizawa T, Yoshida S, Watanabe H, Odawara N, Sakitani K, Arano T, Takiyama H, Kobayashi H, Kogure H, Fujishiro M. Brown slits for colorectal adenoma crypts on conventional magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging using the X1 system. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:2748-2757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Issaka RB, Chan AT, Gupta S. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Risk Stratification for Colorectal Cancer Screening and Post-Polypectomy Surveillance: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1280-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gao K, Jin H, Yang Y, Li J, He Y, Zhou R, Zhang W, Gao X, Yang Z, Tang M, Wang J, Ye D, Chen K, Jin M. Family History of Colorectal Cancer and the Risk of Colorectal Neoplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120:531-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Joo JE, Viana-Errasti J, Buchanan DD, Valle L. Genetics, genomics and clinical features of adenomatous polyposis. Fam Cancer. 2025;24:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rebuzzi F, Ulivi P, Tedaldi G. Genetic Predisposition to Colorectal Cancer: How Many and Which Genes to Test? Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:2137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/