INTRODUCTION

The global healthcare-related climate footprint is estimated to be approximately 4.4% of all greenhouse gas emissions. These emissions create a paradox: Healthcare dedicated to health, contributes to climate change that harms health[1]. Greenhouse gas emissions are systematically categorized into three distinct scopes. Scope 1 emissions pertain to direct emissions originating from on-site sources owned or directly controlled by the institution. Scope 2 emissions represent indirect emissions derived from the generation of purchased off-site energy, including electricity, steam, heat, or cooling. Scope 3 emissions encompass all other indirect emissions that arise throughout the institution’s value chain, notably including the manufacturing of medical devices, employee and patient commuting, and waste disposal[2].

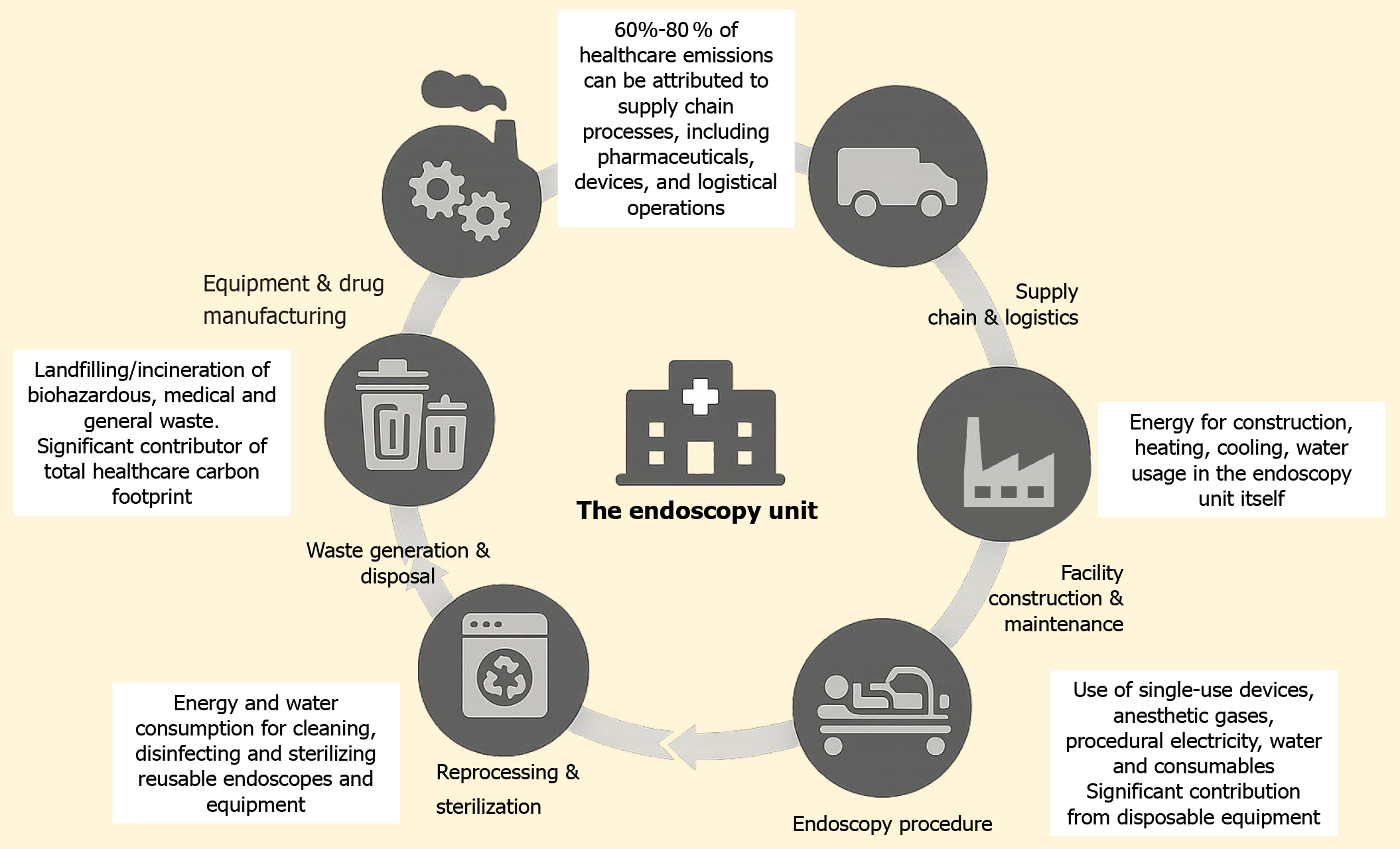

Gastrointestinal endoscopies have significantly contributed to the medical carbon footprint mainly due to the myriad of resources that go into performing endoscopy and the waste it generates[3,4] Carbon footprint is quantified in carbon dioxide equivalent emissions. This activity results in an estimated annual emission of 85768 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in the United States. The caseload of endoscopies in the United States is enormous, estimated to be approximately 22162641 cases performed in 2019[3]. Gastrointestinal endoscopy-related carbon footprint is not only directly related to the procedure itself, but also incorporates the patient and industry-related factors. Patients must prepare (bowel preparation for colonoscopy) and arrange travel for the procedure. Equipment needs to be manufactured and processed, including waste disposal, which are industry-related factors. An estimated 30000 metric tons of waste is generated annually from all the endoscopic procedures performed in the United States. This waste is enough to cover 117 soccer fields to a depth of one meter[4]. As per the 2023 United States Environmental Protection Agency report, organizations’ supply chains account for more than 90% of greenhouse gas emissions[5]. The environmental footprint of the endoscopy unit extends well beyond the procedure room, including unseen elements such as the supply chain, energy consumption, and waste management. This review explores strategies to recognize, promote, and incentivize energy-smart initiatives to reduce the carbon footprint of endoscopy waste (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The environmental footprint of the endoscopy unit.

STRATEGIES FOR IMPLEMENTING GREEN ENDOSCOPY

The endoscopy unit is the third largest department in medical waste across various healthcare facilities. Park and Cha[6] associated it with high case volumes, commute to the units, many nonrenewable wastes, and single-use devices. Calculations involving the precise quantification of carbon footprint would entail a complicated and tedious evaluation and knowledge of the entire lifecycle of any product, right from its manufacture, distribution, utilization, and subsequent disposal or energy expenditure for recycling. Although it appears to be a Herculean task, especially considering the multiple variables at play, an educated and extrapolated carbon footprint estimate would still support the concept of green endoscopy by reducing and recycling products as much as possible[7]. A recent study in Asia assessed the awareness and acceptance of green endoscopy among healthcare workers[8]. Of 259 valid responses, 79.5% of participants agreed to incorporate green endoscopy into their practice. However, only 12.7% of respondents reported existing green policies[8]. Potential barriers to implementing green endoscopy include healthcare cost increment, infection risk, inadequate awareness, and lack of policy and industrial support. Herein, we discuss the roles of physicians, gastrointestinal societies, hospital systems, endoscopy innovation, and current guidelines to improve and implement its awareness[9].

Physician role

As end users, physicians are pivotal in the “green endoscopy” initiative. However, much work has to be done to educate and develop an understanding of the detrimental environmental effects of endoscopies among endoscopists. The first step would be to raise awareness of the increased accumulation of medical waste released from endoscopy units amongst healthcare providers and industry. Healthcare professionals with an adequate understanding of climate change and knowledge of reducing waste are often stunned when informed about the extent of carbon waste generated in healthcare settings, including endoscopy units.

The best step in reducing the cost in gastroenterology would be to have a universally acceptable multi-society guideline-based stringent criterion to include patients for any endoscopic procedure and perform endoscopies if the outcome would change the management of the patient[10]. An estimated 56% and 23%-52% of referrals for upper gastrointestinal endoscopies and colonoscopies are deemed inappropriate[11,12]. Educational activities for referring physicians and having a local departmental screening of referrals made for endoscopies may help reduce unnecessary procedures[13,14]. Avoiding unnecessary procedures significantly reduces physician, patient, and industry-related carbon footprints. In addition, physicians and healthcare systems should also develop quantity and quality metrics and be compensated and rewarded for their efforts.

There should be strategies in place to reduce or eliminate unnecessary clinic visits before or after any endoscopy procedure. During the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, we shifted to online tele-visits. It may be a consideration for patients with a known chronic diagnosis who are stable and do not require an examination by the gastroenterologist before or after an endoscopy. Insurance companies often dictate mandatory clinic visits before a colonoscopy screening or medication refills. The frequency of clinic visits can be reduced as well. When clinically indicated, bi-directional endoscopies reduce the cost and carbon footprint, patient travel, procedure time, and resources used during endoscopy[15,16], including personal protective equipment, plastic tubing and containers, single-use biopsy forceps, use of water, and electricity. This strategy would also reduce administrative tasks, lead to a shorter stay, and require single sedation instead of twice[17]. It could be helpful for other considerations, such as anticoagulation discontinuation before endoscopy. Performing an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy before a colonoscopy has been shown to reduce anesthesia time, anesthetic medications, recovery time, and complications[18,19].

Training modules on green endoscopy for gastrointestinal physicians, staff, and technicians could also be incorporated. The inclusion of sustainability in the training curriculum could be relied on as a quality domain for endoscopy units. Additional training modules could be included to retrain endoscopy workforce in any newly available information on recycling or reprocessing endoscopes or equipment. We should also have a clear understanding of which procedures generate excess waste. Added awareness could be achieved by using quality improvement projects, such as screening referrals for procedures aimed at sustainable care.

Interestingly, processing three pots of histopathology slides is equivalent to driving 2 miles in an average mileage car as estimated in terms of greenhouse gas emissions[20]. An analysis of upper gastrointestinal endoscopies performed for dyspepsia revealed a change in the management in only one-sixth of the cases. However, biopsies were obtained in approximately 83% of those cases[21]. The concept of ocular pathology prediction with the proposed “resect and discard” polyp management strategy suggested by the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) for diminutive polyps holds promise in meta-analysis studies as part of the ASGE technology systematic review along with the 2020 British Society of Gastroenterology, Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain, and Ireland/Public Health England post-polypectomy and post-colorectal cancer resection surveillance guidelines[22,23]. However, concerns about missing unknown high-grade dysplasia in these polyps and reimbursements reveal a gap in the willingness of gastroenterology practices to adopt this strategy[24]. Recent advances in using artificial intelligence in luminal endoscopies have helped accurately detect and characterize polyps, reducing the need for biopsies and histopathological assessment[25]. The use of cold snare polypectomies is economical and environmentally friendly, but it also has been shown to have better outcomes regarding delayed bleeding, mean polypectomy time, and fewer emergency visits after polypectomies[26]. Cold snares could also be used for smaller diminutive polyps as they have a better (P < 0.001, when compared with cold biopsy forceps polypectomy) en bloc resection rate and can be used again for larger polyps in the same patient[26,27].

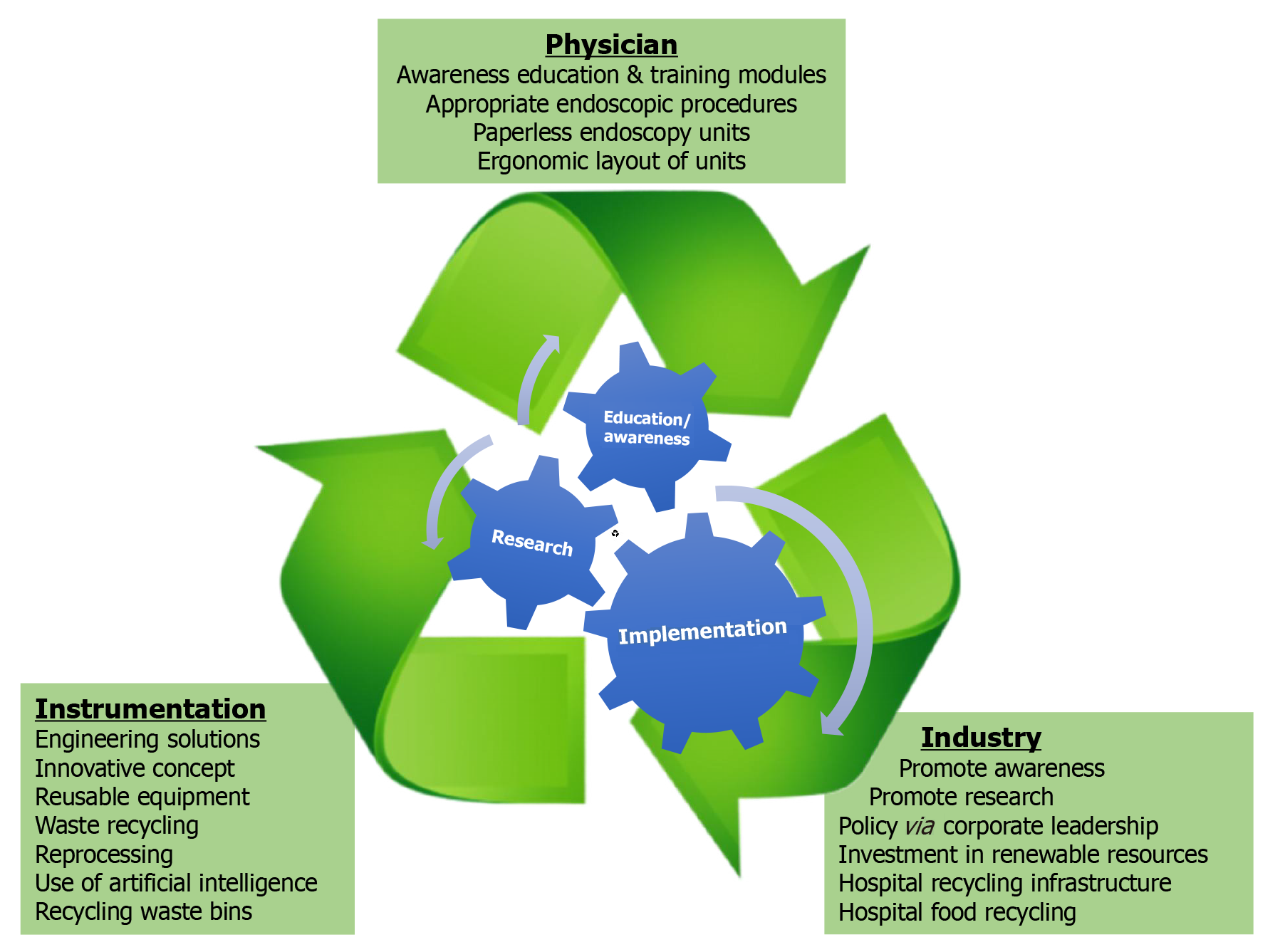

Different X (formerly Twitter) groups exist on society websites, with active participant discussions on various healthcare-related topics, including green endoscopy. It is a platform to exchange ideas and discuss endoscopy waste contributing to climate change and climate crisis. Physicians could utilize X (formerly Twitter) as a resource to raise awareness of the ecological footprint of healthcare and discuss practices to reduce carbon emissions (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Pathway to green endoscopy.

Employer contribution

Successfully overcoming the global coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has shown that healthcare organizations can implement changes and strategies at various levels for better healthcare-related outcomes. Employers need to develop a multi-strategic task force to develop a game plan to reduce waste using new and existing infrastructure. The consensus to endorse and implement green endoscopy should be one such effort. In addition, every hospital should have an “environmental champion”, whose aim should be to work as a liaison and facilitate communication between the employer and staff to develop means for sustainability. Employers should provide scheduled repetitive training to their endoscopy staff and technicians about green endoscopy and conservation. Staff should be apprised to prioritize the use of equipment near their expiration dates if possible.

Hospitals should also start focusing on renewable energy sources. On September 14, 2020, the CISION PR Newswire announced that after decades of long-term investment in renewable energy, such as solar energy, Kaiser Permanente became the United States’ first carbon-neutral healthcare system. It has been suggested that healthcare systems in the United States adopt a universal standardized reporting system for their net carbon emissions. Moreover, a part of their compensation and accreditation should depend on this mandate reporting[28]. In the United Kingdom, an estimated 4% of the National Health Service’s carbon footprint comes from staff travel to and from work[28,29]. In the United States, an estimated 85% of the trips by the endoscopy staff to work are in single-occupancy vehicles. Different modes of transportation could be suggested, like walking, using bicycles, and public transportation. However, these individualized decisions are highly variable[15].

Paper medical documents accounted for nearly 30% of the waste generated by hospitals in the United Kingdom about 20 years ago[30]. Incorporating electronic healthcare record systems was one of the most effective climate-smart solutions that have significantly reduced paper waste and promoted sustainable record-keeping practices. Though access to digital information and internet access differs[31], a detailed digital set of endoscopy instructions, including the use of interactive text messaging features, would have a positive impact on reducing paper waste and even endoscopy outcomes[32-34]. Using electronic healthcare record in United States institutions has successfully reduced the carbon footprint of paper waste[35]. Advocating a ‘paperless endoscopy unit’ consisting of electronic records for all documentation purposes, including administration and medical documentation, could be achieved[36]. Endoscopy units could emphasize administrative staff working from home. This would include pre-endoscopy and post-endoscopy patient assessment and education, pathology results in reporting, and clinic follow-up.

Sensor-activated taps and low-flow devices installed on faucets and toilets have demonstrated water conservation[37]. Electricity conservation is achievable by incorporating light-emitting diodes bulbs, which reduce energy usage by 65%[38,39]. Sensors on light-emitting diodes have also been shown to reduce energy usage by 62%[36]. Every hospital has the infrastructure to recycle. Waste management is a recognized critical factor that could help endoscopy centers attain zero carbon emissions. Endoscopy units are the third largest waste-generating department in hospitals, with an estimated average of 13500 tons of plastic waste per year from an endoscopy unit performing 40 endoscopies per day[40]. Various published audits from the intensive care units suggest that 20% to 30% of waste is potentially recyclable[15]. These numbers concur with the World Health Organization published data. Employers should prefer doing business with industry partners focusing on environmental sustainability and manufacturing reusable or recyclable instruments. Here, the healthcare administrators play an important role in implementing such sustainability measures. The concept of recycling waste bins rather than waste bins for disposal needs to be adopted. It will lead to increased recycling, reusing and reducing waste, contributing to financial gains while reducing carbon waste. Regarding waste disposal and management, the local hospital infection control team should participate in the implementation and policy-making process for recycling. The hologram of the waste disposal bin could be incorporated into the equipment accessory package to ensure the correct and safer disposal of waste in appropriate containers. The waste disposal bins should also be easily accessible, as suggested in all endoscopy rooms, and have an ergonomic layout[37].

Many society guidelines for reprocessing endoscopes, including one from the ASGE, exist. ASGE has formulated a task force on sustainable endoscopy composed of interested members from diverse healthcare settings on strategies to reduce the environmental impacts of endoscopic practice[41]. The European Society of Gastroenterology and Endoscopy and the European Society of Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Nurses and Associates have provided statements on reducing the environmental impact of gastrointestinal endoscopy[42]. However, The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has not endorsed a particular guideline[43]. Hence, hospitals and endoscopy centers use different volumes of solutions to aspirate endoscopes for precleaning[44,45]. After use, the manual cleaning of endoscopes involves brushing and submerging them in an enzymatic cleaning solution, which is prepacked and added to the waste. Reusable cleaning devices and brushes are being adopted, a step towards green endoscopy[46-48]. A greener agent for high-level disinfection should be pursued. Many disinfectants exist, while only a few guidelines favor Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared disinfecting agents[44,45,48].

Endoscope reprocessing includes precleaning, cleaning, and post-processing disinfection of the endoscope and the reusable components[37]. This process utilizes an estimated 24.67 kWh of electricity (an estimated 0.017 tons of carbon dioxide equivalents) and approximately 30 gallons of sterile water per endoscope reprocessing[49]. The issue of using sterile water instead of tap water during endoscopies has been a matter of debate, with no evidence of clear benefit in clinical studies[42]. Using sterile water increases the procedure’s cost and waste related to the endoscopy, as these containers are discarded immediately after use. These containers are also equipped with big and long caps to attach to the tubing system, increasing the amount of plastic in them. The available evidence indicates that tap water is safe and appropriate for endoscopies. In place of sterile water used for endoscope reprocessing and during endoscopies, portable water filtration systems could be installed locally to the tap plumbing system[50-52]. However, various issues must be considered, including a standardized filtration system for different water quality in other regions of the country and addressing infection control. Local water recycling with sterilization is a proposed alternative. However, this will incur a substantial upfront investment for any healthcare system or hospital[53]. Adequate awareness and judicious use of single-use, non-recyclable endoscopy accessories such as biopsy forceps, snare catheters, and plastic containers can reduce the disposable waste generated during endoscopies[54].

Endoscopy innovation

Carbon pricing tags a dollar amount to the greenhouse gas emission by any product or company. This is the calculated indirect cost that society pays for carbon emissions in the form of healthcare costs, flooding, and drought associated with carbon emissions. This would lead to awareness and adoption of economic incentives to utilize clean technology. We need further discussion with the industry to develop engineering solutions adopting innovative concepts that could lead to the manufacture of devices that could be recycled rather than single-use, for example, disposable snare or biopsy forceps tips. Physicians, staff, and technicians, whether using endoscope accessories, performing procedures, or reprocessing equipment, should be included to obtain feedback on reducing waste.

The United States FDA has suggested that hospitals consider using single-use duodenoscopes or disposable components to decrease the risk of infection transmission because of post market culture surveillance data of fixed endcap duodenoscopes in selected patients[20]. Single-use duodenoscopes, a proposed alternative to conventional duodenoscopes, must be reprocessed[55]. This recommendation arose in the context of procedure-related multi-drug resistant infection (risk range: 0.3%-60%) related to reprocessing of the duodenoscopes[49], the amount of water required for reprocessing (which was estimated to be 30 gallons per cycle) and electricity that utilized in reprocessing the duodenoscope[16]. However, the concern remains that a single-use duodenoscope would leave a larger carbon imprint. Some studies estimate a 20 times carbon dioxide emission[53], while others suggest at least a 40% increase in waste compared to conventional duodenoscopes[12]. Technological innovations can provide a sustainable, better, and safer path with smarter improvements in endoscope design to prevent infection transmission without sacrificing the performance standards of the endoscopes. Innovative device designs should be developed to make reprocessing easier and more effective.

Every endoscope accessory should have a carbon equivalent numbered and carbon price mentioned on the package cover[4]. This would promote mandatory reporting and awareness. In addition, in the era of large polyp endoscopic mucosal and submucosal resections, multipack endoclip packages should be manufactured to reduce packing waste. Moreover, a reusable multi-firing endoclip applicator with endoclip tips could be developed to deploy multiple clips in patients with large mucosal defects, reducing waste from multiple deployers.

Role of gastroenterology societies and policymakers

The British Society of Gastroenterology, Joint Accreditation Group, and Center for Sustainable Health have developed guidance about the sustainable endoscopy practice. Recently, four United States gastrointestinal societies (ASGE, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases) have organized a multi-society task force and announced a joint strategic plan to lessen the environmental impact of gastrointestinal healthcare practices and make recommendations on environmental sustainability[56,57]. Other national societies, such as the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists and Digestive Endoscopists study group, reinforce gastrointestinal endoscopy professionals’ role as sustainability advocates in digestive endoscopy.

Healthcare administrators and policymakers occupy a pivotal position in advancing environmental sustainability within the healthcare sector. As leaders, they possess the authority and resources to champion and implement strategies addressing the intricate relationship between health and the environment. The ability of healthcare administrators and policymakers to mandate standardized reporting for net carbon emissions, potentially linking compensation and accreditation to these environmental metrics, signifies that they are not merely facilitators but essential drivers of systemic change. The “green endoscopy” will create a more sustainable health service and lead to an equitable, climate-smart, healthier future with a promising environmental impact. Their goals and objectives include recommending sustainable clinical practices that reduce waste and carbon footprint, raising awareness and research on sustainable practices, engaging with industry and pharmaceutical companies to provide information on the carbon footprint implications of their products, and identifying options for recycling and reusing the products.

Another practical implementation of sustainable care should be to advocate for every endoscopy unit to appoint a “physician champion” who could help promote green endoscopy. My Green Doctor (https://mygreendoctor.org/) is a management resource for healthcare professionals and managers to save energy and promote healthier communities. Amongst others, the Medical Group Managers Association and the American Academy of Family Physicians are members of the “My Green Doctor”. Many States medical societies, such as in the States of FL and CA, have started climate advocacy initiatives such as “Florida Clinicians for Climate Action” and “Climate Health Now”, etc. As healthcare professionals committed to improving the quality of patients’ lives, it is crucial to broaden the definition of “care” to include the ethical obligation to protect the environment[58].

Role of industry

The 2022 United Nations climate change campaign to achieve a global carbon-neutral footprint by 2050, called “Race To Zero”, incorporates a meta-criterion of the five ‘P’ of pledge, plan, proceed, publish and persuade. Most healthcare technology and drug companies, including all the endoscopy technology companies, have pledged to a lower or zero carbon emission goal by 2030. This is in conjunction with the companies combining the Science Based Target initiative and the United Nation Race to Zero initiative. Endoscopy technology companies such as Boston Scientific Corporation, Medtronic, Ethicon, Olympus, Applied Medical, and Cook Medical, among others, aim to make manufacturing and distribution sites carbon-neutral. The website (https://zerotracker.net) is a global carbon emission tracker for many large international companies. Through research and implementation of environmentally friendly policies, the corporate leadership governing the supply chain organizations and industries could reduce carbon emissions significantly. This would be one of the significant changes since the supply chain contributes to more than 60%-80% of carbon emissions[6,29]. The companies could use renewable resources during manufacturing, make energy-efficient facilities, and reuse solid waste[3,28].

Furthermore, using biodegradable smaller packages could help reduce plastic and paper waste. These packaging should also be color-coded for easy recognition to identify if they are recyclable or not, as it is often difficult to see the instructions in dark endoscopy suites. Another suggestion is to incorporate reusable wrapping for endoscopy instruments. Also, when appropriate, the length of the endoscopic accessory could be reduced to reduce plastic or metal waste. For example, reducing the size of biopsy forceps could reduce their carbon footprint or carbon pricing. Despite significant technological progress, several key impediments hinder the widespread adoption of innovative gastrointestinal endoscopy technologies including reusable multi-firing endoclip applicators. Foremost among these are the limitations in ensuring the generalizability and robustness of artificial intelligence models within diverse real-world clinical environments. The limited number of FDA-approved artificial intelligence algorithms specifically for the gastrointestinal field further constrains clinical integration as of July 2024[59].