Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.114834

Revised: November 17, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 136 Days and 15.2 Hours

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping modern medicine, and gastroenterology and hepatology are among the specialties where its impact is becoming incr

Core Tip: Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming gastroenterology and hepatology, offering tools that enhance diagnostic precision, personalize treatment, and reduce variability in clinical practice. Applications such as computer-aided detection in colonoscopy, non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis, and predictive modeling in inflammatory bowel disease illustrate its tangible clinical impact. However, the widespread adoption of AI remains constrained by methodological barriers, data quality issues, lack of external validation, and ethical challenges related to transparency, accountability, and equitable access. This review provides a comprehensive overview of benefits, limitations, and future perspectives, emphasizing the importance of responsible and patient-centered integration of AI.

- Citation: Suarez M, Martínez R, González-Martínez F, Torres AM, Mateo J. Artificial intelligence and digital transformation of gastroenterology and hepatology: A critical review of clinical applications and future challenges. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 114834

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/114834.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.114834

Contemporary medicine faces an unprecedented volume of information, driven by the exponential growth of biomedical knowledge, the widespread availability of electronic health records, and the development of increasingly sophisticated diagnostic technologies. Within this landscape, gastroenterology and hepatology stand out as specialties that generate vast amounts of clinical data, fueled by the high prevalence of digestive and liver diseases and the growing complexity of their management[1]. Diversity and depth of knowledge in these conditions, together with the heterogeneity of patient populations and clinical presentations, make conventional analytical methods insufficient to extract meaningful, actionable information capable of guiding clinical decision-making with precision and efficiency[2].

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative technology capable of addressing this complexity. Through advanced machine learning (ML) algorithms and deep neural networks, AI enables the analysis of large volumes of heterogeneous data (clinical records, imaging, genomics, and laboratory results) by identifying patterns and relationships that go beyond traditional human analysis[3,4]. This capacity offers opportunities to improve diagnostic accuracy, optimize risk stratification, anticipate disease progression, and personalize treatment strategies, while also contributing to health system efficiency through task automation and improved management of clinical information[5,6].

Despite this promise, the adoption of AI in clinical practice faces significant challenges. The complexity and opacity of many models, particularly those based on deep learning (DL), limit interpretability and raise concerns regarding the reliability of predictions[7,8]. The quality, heterogeneity, and potential biases of clinical data may compromise model validity and generalizability across populations. Moreover, effective integration of AI into health care systems requires overcoming technological, regulatory, and ethical barriers to ensure that these tools complement rather than replace the expertise and clinical judgment of health professionals[9-11].

This narrative review provides a comprehensive analysis of the diverse areas where AI is being applied across the main subspecialties of gastroenterology and hepatology. A literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science from January 2017 to June 2025, focusing on the last five years. Keyword combinations included “artificial intelligence”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, “computer-aided detection”, “computer-aided diagnosis”, “gastroenterology”, “endoscopy”, “radiology”, “liver fibrosis”, “hepatocellular carcinoma”, “inflammatory bowel disease”, “hepatology”, “neurogastroenterology” and related MeSH terms. We included original research articles, meta-analyses, and pivotal prospective studies reporting the development, validation, or clinical application of AI models in gastrointestinal diseases. Non-English articles, technical reports without clinical applicability, conference abstracts, purely methodological descriptions, and studies lacking performance metrics were excluded. The articles selected for the development of this manuscript are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The aim of this narrative review is to deliver an updated overview of the advances achieved, together with the conceptual framework necessary to accurately interpret the growing body of literature on this subject. In doing so, we offer readers a broad and evidence-based perspective on the opportunities, limitations, and future directions of AI in digestive health care.

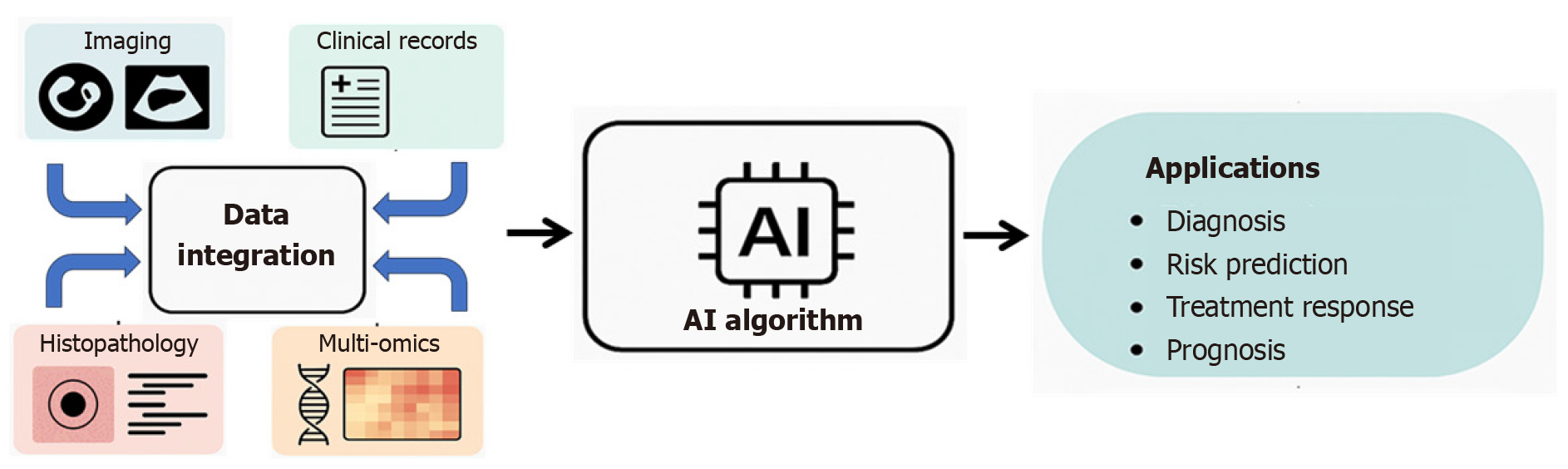

AI is a field of Computer Science that aims to develop systems capable of performing tasks that traditionally required human intelligence, such as pattern recognition, the interpretation of complex data, decision-making, or problem-solving[12,13]. In the biomedical field, the rapid growth in the volume and complexity of data generated in clinical practice, including structured clinical information, laboratory data, medical imaging, histopathology, and genomic and mic

Within this broad field, one of its fundamental pillars is ML, which is based on designing algorithms capable of learning from previous examples. Instead of being explicitly programmed with predefined rules, ML models identify patterns and relationships in data to make predictions or classifications on new, unseen cases[15,16]. There are several types of ML: Supervised learning, which uses labeled data to train models capable of predicting labels for new data; unsupervised learning, which seeks to discover latent structures or clusters in unlabeled data; and reinforcement learning, where an agent learns to make decisions by optimizing a reward signal[17]. These approaches have been successfully applied in medicine to develop predictive models for clinical outcomes, therapeutic responses, or risk of complications, among others (Figure 1).

A particularly powerful branch of ML is DL, which employs artificial neural networks (ANN) with multiple layers to model complex and non-linear relationships in data[12,18]. These models, inspired by the structure and function of biological neural networks, have shown outstanding performance in tasks such as medical image processing, histological pattern recognition, physiological signal analysis, and natural language processing (NLP). For example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have enabled major advances in the automatic analysis of endoscopic and radiological images, while recurrent neural networks and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks have shown excellent performance in analyzing temporal sequences such as manometry recordings or continuous physiological signals[19,20].

The development of an AI model follows a structured process comprising several critical stages. Initially, data are collected and preprocessed, which involves cleaning, normalization, and, in many cases, expert labeling. During the training phase, the model adjusts its internal parameters to minimize an error or loss function on the training data. To monitor learning and avoid overfitting, which occurs when a model becomes too tailored to the training data and loses its ability to generalize, an independent validation dataset is used. Finally, model performance is evaluated on a third dataset (test set), which simulates its behavior on previously unseen cases[21,22].

A widely used statistical technique to ensure robust and reliable evaluation, especially when sample sizes are small, a common situation in early clinical studies, is cross-validation. This method divides the dataset into several subsets or folds and iteratively uses one fold as a validation set and the remaining folds as training data, rotating their roles until all folds have served in both phases[15]. This approach provides a more stable estimate of performance and reduces the risk of overestimating a model’s true accuracy, which could happen if the evaluation depended on a single data split (Figure 2).

Within biomedical applications of AI, NLP has emerged as a fundamental tool. This field focuses on analyzing and understanding human language, enabling the extraction of structured information from unstructured clinical texts such as medical reports, progress notes, or scientific literature. These techniques facilitate automation of tasks including diagnostic coding, adverse event detection, and clinical summarization[23,24].

In recent years, the development of large language models (LLMs), such as GPT, BERT, or BioBERT, has represented a major qualitative leap[25]. These models, trained on massive amounts of general and biomedical text, can perform complex tasks such as answering clinical questions, assisting with literature searches, and generating research hy

Understanding these basic concepts is essential for critically interpreting the scientific literature on AI applied to medicine. It allows researchers and clinicians to assess whether a model has been appropriately developed and validated, and whether its results can be generalized to other populations and clinical settings beyond those used for training. Only through methodologically rigorous development and robust validation will it be possible to safely and effectively incorporate these tools into everyday clinical practice[13].

AI is emerging as a valuable tool in this field, where the complexity and heterogeneity of functional gastrointestinal disorders present significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. By integrating diverse sources of information, including clinical, analytical, and manometric data, AI offers the potential to develop predictive models that may enable more personalized management strategies for these patients.

The widespread implementation of high-resolution esophageal manometry (HREM) in gastroenterology units has underscored the importance of accurate and efficient interpretation of these studies. DL models, CNNs, and even multimodal platforms such as Gemini have demonstrated potential for assisting in the classification and diagnosis of all entities included in the Chicago Classification[28-30]. Beyond the analysis of HREM tracings, AI can also be applied to panometry using the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) achieving high diagnostic precision[31].

For example, in the evaluation of dysphagia, AI has been shown to estimate the integrated relaxation pressure from swallowing sounds with high accuracy. This approach may circumvent the discomfort, time consumption, and potential adverse effects associated with HREM[32]. Although with lower performance, AI can also distinguish normal from abnormal swallowing sequences with accuracy exceeding 80%[33]. it may refine the diagnosis of functional dysphagia by detecting intraluminal abnormalities, such as impaired peristaltic distension phases in patients with a narrow-lumen esophagus[34]. Similarly, automated interpretation of FLIP panometry images has achieved up to 89% accuracy in classifying esophageal motility disorders, highlighting its promise as a supportive diagnostic tool when the device is available[31].

Given the large volumes of data generated by functional studies, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) represents another condition well suited to AI applications. DL models can accurately identify and quantify reflux episodes and post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave indices from pH-impedance monitoring, both of which are essential metrics for GERD diagnosis[35]. AI has also been used to automatically calculate baseline impedance (BI) values in pHmetry interpretation[36], as well as mean supine BI, which correlates strongly with mean nocturnal BI, a recognized marker for GERD[37]. Moreover, although sensitivity remains modest (67%), AI-based systems have been developed to aid in the diagnosis of GERD during endoscopy, achieving a specificity of 92% and an area under the curve (AUC) of approximately 83%[38].

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal disorders, with a chronic and fluctuating course, a significant impact on quality of life, and substantial health care costs associated with its diagnosis and management[39]. Development of AI in this field is both important and challenging, as it could improve the clinical management of these patients.

A key application of AI lies in the analysis of endoscopic images. Image-based AI models have demonstrated the ability to distinguish duodenal images of patients with FD from those of healthy controls, particularly in Helicobacter pylori-negative individuals, achieving remarkable performance with an AUC of 0.85, a sensitivity of 58.3%, and a specificity of 100%. This is particularly valuable because endoscopic abnormalities in FD are often subtle and im

Beyond imaging, AI systems may also support FD diagnosis by analyzing brain activity and dietary preferences. A model using prefrontal cortex activity measured with functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) combined with food preference scores achieved 77.1% accuracy in distinguishing patients with FD from healthy controls. This non-invasive, portable approach provides objective evidence, facilitates use in clinical practice, and could shorten the diagnostic process[41].

ML is also instrumental in standardizing and objectifying symptom pattern identification in FD. These models may uncover key symptom profiles, including those not consciously recognized by physicians or based on the absence or low severity of a symptom[42]. Current efforts are exploring AI algorithms that integrate multiple brain-body biosignals fNIRS, pulse wave, skin conductance response, and electrocardiography (ECG) to predict FD patterns. Such integration is expected to enhance the objectivity and reliability of traditional diagnostic approaches, providing a more comprehensive understanding of patient conditions[43].

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is another of the most common gastrointestinal disorders worldwide, with a rising prevalence. Its high frequency and nature as a diagnosis of exclusion often lead to substantial health care expenditure and unnecessary investigations, driven either by diagnostic uncertainty or by patient demand for testing[44].

AI models analyzing endoscopic images in IBS patients have shown the ability to detect subtle changes invisible to the human eye. This is a meaningful advance, as IBS diagnosis relies on the absence of organic disease, though subtle mucosal alterations may exist that distinguish IBS patients from healthy individuals. These models may also differentiate diarrhea-predominant from constipation-predominant subtypes[45].

Another promising avenue is the use of bowel sound analysis through AI as a non-invasive, reliable, replicable, and cost-effective diagnostic tool. An early study in the late 20th century demonstrated significant differences in fasting sound-to-sound intervals between healthy subjects and IBS patients, with 89% sensitivity and 100% specificity[46]. More recent work by Du et al[47] reported 87% sensitivity and specificity, although technical challenges in development indicate that further research is needed in this field[48].

AI has also been explored in personalized dietary interventions based on microbiota analysis. Diet-induced mi

Mobile health applications incorporating AI represent another promising area. Its development may allow the monitoring and evolution of symptoms in an objective way. A smartphone app developed by Pimentel et al[52], which assessed stool form according to the Bristol Stool Scale, outperformed patient self-reporting in stool classification. Such tools may facilitate more accurate monitoring and follow-up in IBS management.

The application of AI in anorectal disorders has focused primarily on the diagnosis and prediction of outcomes from high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) data. HRAM is widely used for conditions such as fecal incontinence and constipation, but interpretation of tests like the balloon expulsion test remains complex and subject to operator variability[53]. AI has emerged as a promising solution to enhance diagnostic accuracy and efficiency in this context, although available studies remain scarce.

Seo et al[54] introduced the novel concept of time-series integrated pressurized volumes (TS-IPVs) for the analysis of HRAM data to predict delayed balloon expulsion test results. Diverging from conventional static IPV metrics, TS-IPVs uniquely capture the dynamic, spatio-temporal patterns of anorectal pressure variations during defecatory maneuvers. This innovative approach offers a more comprehensive assessment of functional abnormalities and has demonstrated superior predictive capabilities for delayed balloon expulsion test outcomes, marking a significant advancement in clinical interpretation. The model, based on CNNs and LSTM networks, achieved excellent accuracy with an AUC of 0.99, and the TS-IPV13 ratio was identified as the strongest predictor[54].

The model, based on CNNs and LSTM networks, achieved excellent accuracy in classifying delayed BE test outcomes, with an AUC of 0.99. The TS-IPV13 ratio (the TS-IPV of the upper 1 cm vs the lower 3 cm of the anal canal) was identified as the strongest predictor, with AUCs of 0.988 for women and 0.996 for men[54]. In practical terms, this model performed nearly perfectly for this task. However, it is important to acknowledge that many studies in this section, including this one, are currently proof-of-concept studies. While these findings mark a highly promising starting point for developing AI-based diagnostic tools in anorectal disorders, limitations often include retrospective design and relatively small sample sizes, highlighting the need for further rigorous external validation in larger, diverse patient cohorts before widespread clinical implementation.

AI has the potential to enhance the diagnostic accuracy of functional tests, detect subtle changes and complex patterns, and optimize workflows by reducing interpretation times[29,31]. It can also facilitate learning, both in medical training and in patient education, by providing accessible applications that help patients better recognize and monitor their symptoms[38]. Furthermore, AI supports the transition toward personalized medicine, enabling the prediction of therapeutic outcomes and the integration of microbiome data to individualize treatment strategies. The use of these new technologies may also generate novel metrics, previously undescribed, that further contribute to the individualized management of patients[55].

Most studies in this field are still retrospective and single-center, which limits generalizability[29]. Broader multicenter validation and interpretability issues remain common challenges, which are examined in detail in the Discussion section.

Hepatology represents a particularly promising field for the application of AI. Currently, AI is reshaping diagnosis, treatment, and disease management in complex and increasingly prevalent conditions such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[56]. By leveraging ML, DL y NLP, AI can integrate data from electronic health records, imaging, pathology, and multi-omics sources to transform large datasets into actionable information for personalized patient care[57-59].

Detection of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis: Studies applying neural networks or gradient boosting machines explicitly reported AUC as the main outcome metric, with some additionally providing calibration curves or confusion-matrix–based metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity). ML models developed with random forest (RF) and ANNs have been shown to outperform both transient elastography and the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score in predicting fibrosis stage in patients with MASLD[60]. For instance, Chang et al[61] reported that RF algorithms more reliably detected stage F4 fibr

Similarly, Light Gradient Boosting Machine algorithms have predicted cirrhosis in patients with hepatitis B with greater accuracy than conventional tools, leveraging their efficiency in handling large datasets[63]. The development of the AI-Cirrhosis-ECG score is noteworthy. Using DL on ECGs in patients who are candidates for liver transplantation, this tool was developed to detect patients with cirrhosis at low cost with an AUC 0.908[64].

Beyond clinical and laboratory data, AI models applied to imaging have demonstrated significant advances. Com

| Input data type | AI tool | Conventional metric/tool outperformed | Key AI contribution | Evidence level | Primary limitation |

| Clinical/Laboratory | RF, LightGBM, ANN | FIB-4 score and transient elastography | More reliable prediction of fibrosis stage; development of novel indices (e.g., FIB-6, validated in multicenter cohorts) | Moderate-high (multicenter validation available for FIB-6; large cohorts in MASLD studies) near clinical use | Some models remain retrospective; limited external validation for several algorithms; interpretability constraints |

| Imaging (CT, MRI, US, elastography) | DL (CNNs, ResNet50), Radiomics | Expert radiologists; elastography alone | Enhanced cirrhosis detection; automatic segmentation; identification of inflammation/fibrosis; distinction of etiologies; radiomics improves staging precision | Moderate (several studies with external validation, but heterogeneous datasets), promising | Data heterogeneity; many single-center cohorts; limited standardized imaging protocols; 'black box' interpretability |

| ECG | DL (AI- cirrhosis-ECG score) | Standard clinical evaluation | Low-cost cirrhosis screening with high AUC (0.908); potential for routine, scalable screening | Low-moderate (retrospective, single-center), emerging | Limited sample size; lack of external validation; implementation barriers despite low test cost |

Detection of clinically significant portal hypertension and esophageal varices: AI has also been explored as a noninvasive alternative to hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement. ML models using biopsy data (AUC 0.85), histology, CT-based radiomics, or common laboratory parameters (AUC 0.775) have shown high accuracy in predicting clinically significant portal hypertension, outperforming other noninvasive methods[70-72]. In the evaluation esophageal varices bleeding and their risk of bleeding, ML algorithms[73,74] and CNNs trained on extensive endoscopic image datasets have been used to grade varices, estimate bleeding risk, and predict rebleeding events with high reliability[75,76].

Management of decompensated liver disease: AI has also shown potential in predicting decompensation episodes, which may be invaluable both for patient management and for supporting caregivers. ML models have predicted severity and the presence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with high negative predictive values, thereby reducing unnecessary paracenteses[77-79].

As with ascites and the presence of varices, the use of AI has also been implemented in hepatic encephalopathy. ML techniques have been employed for diagnosis, classification, and prognosis using diverse data sources, including MRI, electroencephalography, and video-oculography. Although results to date are encouraging, further studies and standardized diagnostic criteria are required before clinical implementation[80].

Diagnosis and management of HCC: HCC prediction models used heterogeneous architectures, ranging from logistic regression and RFs to CNN-based imaging frameworks, with AUC and sensitivity as the predominant performance metrics.

Risk stratification of HCC: ML models have consistently outperformed traditional regression-based approaches in predicting HCC risk among patients with cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, and MASLD[81-83]. Notably, even in the uncertain setting following hepatitis C virus eradication, AI-based models have shown promising accuracy for predicting HCC development[84,85]. Integrating imaging, transient elastography, and clinical and laboratory data enhances the performance of both tree-based ML models and CNNs for risk stratification[86,87].

Diagnosis of HCC: Radiomics applied to imaging modalities has emerged as a particularly promising approach for AI development in HCC diagnosis, treatment response prediction, and prognostication. DL models across different imaging techniques can distinguish benign from malignant lesions with accuracy comparable to expert radiologists, while also identifying indeterminate nodules and predicting microvascular invasion[65,88-90]. Similarly, AI can estimate survival, recurrence risk, and response to locoregional therapies such as transarterial chemoembolization[91-93]. Beyond imaging, the integration of multi-omics and histopathological data allows stratification of patient subgroups according to predicted survival, thereby supporting more personalized therapeutic decisions[94,95].

In pathology, AI is revolutionizing histological assessment. DL and CNN-based methods can classify tumor tissue and distinguish HCC from other primary or metastatic liver tumors with near-perfect reliability of 100%[96,97]. Moreover, AI has demonstrated the ability to identify histological subtypes and even predict underlying genetic mutations from hematoxylin eosin (H&E) stained slides[98,99]. A synthesis of this evidence is provided in Table 2.

| Management stage | Data source/technology | AI application | Key benefit | Evidence level | Primary limitation |

| Risk stratification | Clinical, viral (HCV), cirrhosis data | ML models (outperform traditional regression) | Superior prediction of HCC risk, even post-HCV eradication or in MASLD | Research | Retrospective design; single center; limited generalizability; data heterogeneity; 'black box' nature |

| Imaging diagnosis | Radiomics (CT, MRI)/DL | Classification of benign vs malignant lesions | Identifies indeterminate nodules and predicts MVI | Research | Validation needed in diverse populations; 'black box' interpretability; generalizability across centers |

| Pathology | H&E histological slides | DL/CNNs | Classification of tumor subtypes and prediction of genetic mutations with near-perfect reliability | Research | Dependence on quality of scanned slides; potential for algorithmic bias; 'black box' interpretability |

| Prognosis/treatment | Imaging/multi-omics/clinical data | Estimation of survival and therapeutic response | Prediction of recurrence and response to locoregional therapies (e.g., TACE) | Research | Need for broader multicenter validation; data heterogeneity; 'black box' nature; integration into clinical workflow |

AI-enhanced robotic surgery improves dexterity and precision in complex hepatic procedures. Three-dimensional visualization and ML-assisted case modeling allow detailed preoperative planning, including lesion resection and estimation of the future liver remnant volume[57].

ML has shown promise in optimizing organ allocation, surpassing conventional scoring systems such as the model for end-stage liver disease. For example, Bertsimas et al[100] developed the optimized prediction of mortality model, which more accurately predicted waitlist mortality and had the potential to reduce waitlist deaths by 17.5%. ANN have also been applied to improve donor-recipient matching, reducing incompatibility risks[101].

AI has even enabled quantification of graft steatosis using smartphone-based images. A ML model provides valuable information for intraoperative decision-making and graft viability assessment with an accuracy approaching 90%[102]. Post-transplantation, AI-based models have been explored to predict patient and graft survival, risk of disease recurrence (particularly HCC), and complications such as acute kidney injury or metabolic syndrome, with encouraging but heterogeneous results requiring further validation[103-107].

AI is increasingly being applied to autoimmune liver diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), as well as drug-induced liver injury (DILI). DL and ML approaches have enabled diagnostic support through MRI-based assessment of the biliary tree in PSC, prognostic modeling[108,109], or histological differentiation between AIH and PBC[110]. Proteomic integration has further allowed improved classification of autoimmune liver diseases[111].

DILI, characterized by highly variable clinical presentations, poses major diagnostic challenges. Its presentation is so heterogeneous that it greatly complicates diagnosis if it is not taken into account or if a clear temporal association is not found. AI approaches have shown potential both in identifying causative drugs and in supporting earlier diagnosis of this entity[112,113].

The range of diseases covered by steatotic liver disease (SLD) and its high prevalence encompasses the largest number of patients with liver disease. In MASLD, AI models based on clinical and laboratory data have demonstrated strong performance in detecting fibrosis and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis[114,115]. AI has also enabled objective, reproducible quantification of key histological features of NASH (steatosis, ballooning, and inflammation) from liver biopsies[60,116]. This standardization reduces interobserver variability, facilitates communication among pathologists, and improves reliability in clinical trials. In alcoholic liver disease (ALD), AI has been applied to distinguish ALD from MASLD using noninvasive tests, as well as to predict disease progression and enable early detection when combined with proteomics[117,118].

Advantages and limitations of AI use in hepatology: AI has emerged as a promising tool in hepatology, enabling advanced data analysis that can enhance the diagnosis, prognosis, and management of liver diseases. By integrating clinical, laboratory, and imaging data, AI has the potential to develop tools that support more personalized and optimized patient care.

As in other domains, hepatology studies face common methodological challenges, including limited data diversity, scarce external validation, and the interpretability constraints of DL models[56,58,60]. Advancing education, promoting knowledge dissemination, strengthening cybersecurity, and fostering greater collaboration among researchers are key steps to facilitate the successful integration of AI into routine hepatology practice[119].

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, unpredictable condition that predominantly affects young patients and significantly impacts quality of life, while also posing a substantial burden on healthcare systems[120]. The complexity of its pathophysiology, encompassing genetic, immune, environmental, and microbial factor, together with variability in clinical presentation and treatment response, has driven the search for innovative tools to optimize disease management. In this context, AI emerges as a transformative technology with the potential to integrate and analyze large volumes of data, improving diagnostic accuracy, personalizing therapeutic strategies, and predicting disease course[121,122].

AI applications in IBD span a wide spectrum of maturity levels. Some developments, such as AI-driven drug discovery platforms, transcriptomic network modeling, and multi-omic patient stratification, remain largely experimental and are currently restricted to research settings. In contrast, more mature and clinically oriented applications, including endoscopic inflammation assessment, automated histology scoring, radiomics-based disease quantification, and prediction of treatment response, have undergone prospective evaluation and in several cases external validation. For clarity, in this revised section we explicitly differentiate between experimental early-stage approaches and those AI tools that are closer to clinical implementation.

AI has facilitated the development of models using multi-omic data from fecal samples to achieve non-invasive IBD diagnosis (including calprotectin, proteomics, metabolomics, virome, metagenomics, and metatranscriptomics)[123]. IBD prediction models included feature-based ML (RF, XGBoost, SVM) and DL architectures for imaging; most studies reported AUC, accuracy, and F1-score, while histology models frequently reported Dice scores for segmentation quality. These models represent a significant advance, as current diagnosis often requires invasive colonoscopy. They can accurately distinguish between healthy individuals, patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), and Crohn’s disease (CD). For example, Huang et al[124] developed a model based on fecal metabolomic and metatranscriptomic data achieving an AUC of 0.83-0.85 for differentiating these three categories. Although other studies report lower performance, this remains a promising area of research. In contrast to multi-omic and drug discovery approaches, imaging- and histology-based AI systems represent more mature applications, with several tools undergoing prospective or external validation

Distinguishing UC from CD, as well as differentiating CD from intestinal tuberculosis, represents a diagnostic challenge due to symptom overlap and endoscopic similarities. AI-based models using endoscopic imaging and NLP have been developed to differentiate CD from intestinal tuberculosis and UC from CD[125,126]. In a study by Lu et al[127], 1271 medical records of patients diagnosed with CD or intestinal tuberculosis were analyzed. Using TextCNN, they developed a model achieving 83% accuracy in differentiating the two diseases based on endoscopic findings.

Assessment of IBD through imaging and endoscopy: Radiomics applied to imaging techniques enables detection of quantitative features imperceptible to the human eye, improving characterization of radiologic abnormalities. High-precision models have been developed to detect strictures in CD and quantify inflammation[128,129]. Additionally, AI has been used to predict the need for surgery or the likelihood of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy failure[130,131]. AI can also automate and standardize scoring of endoscopic activity indices, develop novel scores potentially more accurate than existing ones, and predict relapse risk, flares, or histologic remission among others. This topic will be further explored later in this article.

Utility in histologic assessment of IBD: AI in histopathological analysis promises to be highly valuable. High inter- and intra-observer variability, coupled with the time required for detailed slide examination, underscores the need for tools providing objective, rapid, and reproducible assessments[132].

AI in pathology primarily focuses on automating scoring of validated indices such as the Robarts Histopathology Index (RHI), Nancy Histological Index, and the Paddington International virtual ChromoendoScopy ScOre (PICaSSO) Histologic Remission Index, achieving accuracy comparable to or exceeding expert pathologists. This is accomplished by detecting and quantifying different cell types and other features, such as mucin depletion in goblet cells[133,134].

Histologic analysis also allows superior prediction of future flares in UC patients compared with expert pathologists[135]. Similarly, post-surgical recurrence risk in CD patients can be assessed by analyzing adipocyte retraction and mast cell infiltration in resected specimens[136]. Analysis of p53 protein in H&E-stained slides also shows promise for dysplasia detection without immunohistochemistry, achieving approximately 91% accuracy in the study by Noguchi et al[137].

Prediction of therapeutic response and precision medicine: This represents one of the most complex and necessary aspects of IBD management due to disease heterogeneity and variable treatment responses. Using ML to integrate clinical, laboratory, endoscopic, and multi-omic data, models have been developed to predict response to therapies such as anti-TNF agents, vedolizumab, or ustekinumab[138-140]. This enables timely therapy adjustments for non-responders, improving patient quality of life, optimizing resource use, and avoiding unnecessary costs and adverse effects[141].

Additionally, AI analysis of peripheral blood transcriptomic data can stratify patients into low- or high-risk groups for disease progression or need for treatment escalation. Histology-based models have also been developed to predict post-surgical recurrence in CD, as well as the risk of strictures or fistulas[142-144]. These approaches represent early-stage, experimental applications of AI, primarily operating in research settings rather than in routine clinical care.

Drug development and novel therapeutic targets: AI-driven drug discovery remains an experimental domain, focused on target identification and mechanistic modeling, with significant distance from clinical deployment. AI not only enables optimization of existing therapies but is also increasingly applied in drug development and discovery. For instance, using Boolean networks to analyze transcriptomic data from intestinal tissue, epithelial barrier dysfunction was identified as a central and invariant event in IBD pathogenesis. This analysis highlighted AMPK, specifically the PRKAB1 subunit, as a novel therapeutic target. This AI-guided approach not only prioritized the target but also helped select the most appropriate preclinical models for validation, demonstrating the potential of AI to identify first-in-class therapies with novel mechanisms of action[145].

Another example is the computational platform Boolean Network Explorer (BoNE), designed to leverage AI for enhanced precision in drug discovery. By analyzing large transcriptomic datasets to construct an IBD map, BoNE can prioritize high-value targets. In the study by Katkar et al[146], this platform identified and rationalized dual and balanced agonism of the nuclear receptors PPARα/γ as a promising therapeutic strategy to restore intestinal barrier function. Notably, the platform generates an automated report providing key predictions to guide drug validation, including a therapeutic index estimating the probability of success in phase III trials, the most suitable preclinical models for testing, and the primary cellular target of pharmacological action, in this case macrophages.

Impact on clinical trials: Beyond drug discovery, AI also plays a role in the design and execution of clinical trials. Algorithms can analyze patient medical records to automatically identify and suggest patients who meet inclusion and exclusion criteria, accelerating recruitment and improving patient selection according to study design and objectives[147]. The potential use of “digital twins” or synthetic control arms based on real-world data could further reduce the need for placebo groups and associated ethical concerns[148,149]. Centralized and standardized analysis of imaging, endoscopy, and histological slides can also provide more objective and consistent assessment of study endpoints, reducing costs, time, and variability[148].

Perspectives and limitations in implementing AI in IBD: AI in IBD is evolving from replicating human tasks toward predictive and integrative models that could reshape precision medicine. Future systems are expected to leverage multimodal data (electronic health records, endoscopic and histological imaging, radiology, multi-omics platforms, and real-time inputs from wearable devices) to build “digital twins” capable of simulating disease progression and therapeutic response. Such advances may enable clinicians to anticipate outcomes before treatment initiation and tailor therapy accordingly[121].

In parallel, AI-driven endoscopy is moving beyond conventional indices with the development of more sensitive measures of inflammatory burden, while NLP and LLM-based chatbots may streamline clinical documentation, enhance patient education, and support proactive monitoring[150].

In research, AI could accelerate clinical trials by improving patient recruitment, standardizing endpoint assessment, and facilitating adaptive trial designs, while also driving drug discovery through network-based analyses of complex biological systems[148]. The most relevant applications of AI in IBD are summarized in Table 3.

| Application area | Data source and type | AI application/technique | Key clinical benefit | Evidence level | Primary limitation |

| Non-invasive diagnosis | Fecal multi-omics | ML models | Accurate differentiation of healthy vs UC vs CD | Research/early clinical | Data heterogeneity, limited external validation, small/retrospective datasets, lack of generalizability |

| Differential diagnosis | Endoscopic imaging and clinical records (NLP) | TextCNN/image analysis | Distinguishes CD from intestinal tuberculosis and UC from CD | Research | Symptoms overlap and endoscopic similarities; limited data quality; need for external validation |

| Disease assessment | Radiomics and endoscopic video | DL models | Quantifies inflammation, detects strictures, and automates endoscopic activity scoring improving standardization | Research | Limited data quality and standardization; lack of external validation; 'black box' nature |

| Histological prediction | Histopathological slides | CNNs/DL (automating RHI, NHI, PHRI) | Objective scoring and superior prediction of future flares and post-surgical recurrence | Research | High inter- and intra-observer variability in expert labeling; data quality; 'black box' interpretability |

| Therapeutic response | Clinical, laboratory, multi-omics, endoscopy data | ML predictive models | Predicts response to biologic treatment, enabling timely therapy adjustment | Research/early clinical | Disease heterogeneity; variable treatment responses; need for robust external validation; 'black box' interpretability |

| Risk stratification | Peripheral blood transcriptomics, histology | ML/DL models (low vs high-risk groups) | Predicts disease progression, need for treatment escalation, and post-surgical recurrence/complications (strictures/fistulas). Recurrence/complications (strictures/fistulas) | Research | Need for larger, diverse datasets; limited external validation; potential algorithmic bias |

| Drug development | Transcriptomic data (intestinal tissue)/Boolean networks | Identification of novel therapeutic targets | Accelerates the discovery of first-in-class therapies with novel mechanisms of action | Research | Complexity of biological systems; need for robust preclinical validation; 'black box' nature; ethical considerations |

| Clinical trials | Patient electronic medical records | NLP/DL algorithms | Accelerates patient recruitment and potential use of "Digital Twins" | Research/future prospect | Data privacy and security; regulatory frameworks; ethical concerns regarding "digital twins" and placebo groups |

The methodological and ethical challenges limiting broader adoption of AI, such as data heterogeneity, lack of external validation, and model opacity[151-153], are shared across digestive subspecialties and are discussed at the end of the review. Overcoming these limitations will require strong interdisciplinary collaboration to ensure that AI tools are implemented safely, equitably, and effectively in the management of IBD.

Integration of AI in endoscopy has consolidated around two main technological pillars: Computer-aided detection (CADe) and computer-aided diagnosis (CADx)[154,155]. CADe systems function as a virtual assistant for the endoscopist, capable of identifying abnormalities such as polyps, neoplastic lesions, or inflammatory areas in real time. These algorithms process the endoscopic video stream, automatically highlighting suspicious regions with visual overlays, such as boxes or contours, allowing more focused and detailed inspection[156,157]. Companies such as Fujifilm and Medtronic (GI Genius) have demonstrated efficacy in improving the detection of adenomas and precancerous lesions[158-160].

CADx systems, on the other hand, are applied once a lesion has been detected, evaluating morphological parameters such as surface, vascular pattern, size, shape, and location to classify it as adenomatous or non-adenomatous, or in terms of inflammation, to predict histologic activity. This real-time characterization enables the endoscopist to make informed decisions regarding resection, biopsy, or follow-up strategy, facilitating precise therapeutic choices[161-163]. Combination of CADe and CADx allows simultaneous and integrated use with conventional endoscopy without significant delays or interruptions[158,164]. Endoscopic CADe/CADx systems predominantly used deep CNNs, often ResNet, EfficientNet, or custom CNNs, reporting sensitivity, specificity, per-frame detection accuracy, and, in some studies, Dice or IoU scores for segmentation tasks.

Detection improvement (CADe): In colonoscopy, AI has demonstrated a transformative effect on colorectal polyp detection, increasing the adenoma detection rate (ADR) and improving identification of small and flat lesions, including sessile serrated lesions (SSLs), which are relevant due to their association with post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer[165-167]. A 2021 meta-analysis reported that CADe assistance increased ADR by approximately 7.5% compared with conventional high-definition colonoscopy[168]. A randomized prospective study found a significantly higher SSL detection rate with AI assistance (22%) compared to conventional colonoscopy (11%)[169]. CADe systems are particularly useful for less experienced endoscopists, helping them achieve detection rates close to those of experts and reducing missed adenomas[170,171].

Despite these benefits, some studies suggest that ADR improvement may be minimal for highly experienced en

Polyp characterization (CADx): CADx systems allow real-time classification of polyps as adenomatous or non-adenomatous using white-light endoscopy, without the need for chromoendoscopy[158,162,176]. Diagnostic accuracy is comparable to that of expert endoscopists and superior to non-experts. For instance, CADx systems report sensitivities of 88%-95%, specificities of 84%-88%, and accuracies of 88%-93% for adenomas and diminutive rectosigmoid polyps[177,178]. This precision enables strategies such as “resect and discard” for diminutive adenomas or “diagnose and leave in situ” for hyperplastic polyps, reducing biopsy requirements and histopathology costs. One study estimated an average colonoscopy cost reduction of 18.9% in Japan and 10.9% in the United States when applying the “diagnose and leave” strategy for non-neoplastic lesions[179].

It is important to note that CADx diagnostic accuracy may vary depending on polyp location. Accuracy appears significantly lower in the proximal colon compared to the distal colon, with a specificity of 62% vs 85% for polyps ≤ 5 mm[176]. This difference is attributed to the higher prevalence of serrated lesions in the proximal colon[180,181]. Segment-specific validation is therefore recommended for future CADx algorithms.

Polyp location and size: Polyp size is a key factor in assessing the risk of advanced histologic features and determining surveillance intervals and resection methods. AI improves precise polyp localization through three-dimensional colon reconstructions, overcoming limitations of methods based on anatomical landmarks or insertion depth[182-184]. Measurements integrated into endoscopes, calibrated with polyps of known reference sizes, provide reliable in vivo estimates, reducing operator subjectivity[182,185,186]. This approach eliminates human error, enabling better determination of histology, resection technique, and surveillance intervals.

Barrett’s esophagus: Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is one of the most studied areas for AI applications in endoscopy due to the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. AI has been applied in scenarios ranging from improved identification of BE to detection of neoplastic lesions.

In tandem studies, the use of AI following conventional human video evaluation of BE significantly improved the performance of non-expert endoscopists. Sensitivity increased from 62.0% to 74.7%, and accuracy improved from 67.7% to 75.2%[187]. This is particularly valuable for enhancing diagnostic performance in endoscopists with limited experience in BE assessment.

AI is also applied to quantifying metaplasia. It can automatically extract Prague classification with over 97% accuracy on 3D images[188,189], providing more reliable classification and consistent imaging sets for follow-up, while also improving the quality of endoscopic reporting.

A key application is the detection of dysplastic lesions and early cancers. BE-related neoplasia (BERN) is often flat and difficult to distinguish from surrounding non-dysplastic tissue, leading to high rates of missed lesions (up to 25% for high-grade dysplasia)[154,190-192]. AI systems assist in real-time detection and localization of BERN, improving endoscopist performance, particularly among non-experts[187,193]. AI algorithms have demonstrated high accuracy in differentiating dysplastic from non-dysplastic lesions in BE, achieving 95.4% accuracy[194]. One AI system even outperformed experts using volumetric laser endomicroscopy in Barrett’s neoplasia detection, with 85% accuracy, 91% sensitivity, and 82% specificity in a validation set[195].

Early gastric cancer: In early gastric cancer, AI facilitates detection of superficial and premalignant lesions via real-time analysis of endoscopic images. When combined with image-enhancement technologies (LCI, NBI, BLI), AI highlights subtle chromatic and vascular patterns with accuracy comparable to or exceeding that of expert human endoscopists[196,197]. A prospective study using the ENDOANGEL software reported fewer blind spots (5.38 vs 9.32), with high accuracy (84.7%), sensitivity (100%), and specificity (84.4%) for gastric cancer detection[198]. Additionally, CADx assists in estimating invasion depth and delineating tumor margins, guiding decisions between endoscopic resection and surgery[199-201].

AI also contributes to gastroscopy quality improvement. By identifying blind spots, documenting anatomical land

AI enables more precise visualization and assessment of inflammation severity and distribution throughout the colon, overcoming limitations of traditional endoscopic scores that may not account for segmental differences. It also addresses subjectivity in endoscopic evaluation via algorithms that generate objective scores[204,205]. CAD systems are being developed to provide consistent and objective scoring of endoscopic activity in UC, using indices such as the Mayo Endoscopic Score (MES) and the UC Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS)[206-208]. These systems can also predict histological inflammation. New real time CAD algorithms or PICaSSO can identify endoscopic and histologic remission with high accuracy[209-211]. These systems can also predict persistent histological inflammation.

The Red Density System, another AI-based tool, analyzes pixel color patterns and has shown strong correlation with endoscopic indices (MES, UCEIS) and histologic activity (RHI), enabling objective, computer-based assessment of UC activity[212-214].

An innovative approach is the Cumulative Disease Score (CDS), developed using computer vision analysis of UC endoscopic videos. CDS strongly correlates with MES and demonstrates higher sensitivity for detecting endoscopic changes, requiring 50% fewer participants to detect differences in clinical trials[215].

In CD, AI has two major endoscopic applications. First, when combined with capsule endoscopy (CE), AI allows automated detection of ulcers, erosions, strictures, and bleeding in the small intestine[216]. Several studies report reduced CE reading times (from 96.6 minutes to 5.9 minutes with AI assistance) and improved sensitivity, addressing inter-observer variability and the tedious nature of manual review[217]. These decreases in reading time have been confirmed in other studies since then[218,219]. Combined AI-assisted CE has demonstrated overall accuracy of up to 95.4% for detecting ulcers or bleeding[220,221].

Second, AI facilitates differentiation and improved characterization of strictures, a major challenge in CD due to difficulty distinguishing inflammatory from fibrotic components. DL-based image analysis can predict fibrosis severity, outperforming radiologists and supporting therapeutic decision-making[129,204,222].

NLP enables generation of structured, standardized reports, improving clinical communication and data collection for research, clinical trials, and longitudinal monitoring. This ensures greater consistency, objectivity, and reproducibility in evaluating IBD activity, addressing the variability in terminology used by different endoscopists and CE experts, which can hinder report interpretation and limit cross-center data extrapolation[202].

General benefits of AI in endoscopy: AI enhances not only specific endoscopic tasks but also provides systemic advantages across multiple domains. It reduces inter- and intra-observer variability in endoscopic interpretation, leading to more consistent, objective, and reproducible assessments. AI algorithms consistently produce the same output from identical images or videos, which is invaluable for standardization in clinical practice and clinical trials[202,223,224]. They also have the potential to elevate the performance of less experienced endoscopists toward expert levels, serving as educational tools by providing real-time feedback and helping to identify and address knowledge gaps in trainees and less experienced practitioners[225,226].

AI can optimize workflow efficiency by reducing CE reading times, automating documentation, monitoring colo

| Technology | Function | AI action | Clinical output | Impact | Evidence level | Primary limitation |

| CADe (detection) | Real-time lesion localization | Processes endoscopic video stream and automatically highlights suspicious regions with visual overlays | Increased detection rate | Prevents missed lesions (e.g., sessile serrated lesions, early gastric cancer), particularly for less experienced endoscopists | Clinical trial/commercial | High rate of false positives leading to endoscopist fatigue; potential for increased procedure time; lack of generalizability across diverse populations |

| CADx (diagnosis) | Real-Time lesion characterization | Analyzes morphological and vascular patterns of a detected lesion | Classification of lesions (adenomatous vs non-adenomatous) or activity grading in IBD | Facilitates "Resect and Discard" or "Diagnose and Leave" strategies, reducing biopsy costs and time | Clinical trial/commercial | Variability in accuracy based on polyp location (e.g., proximal vs distal colon); 'black box' nature limiting clinician trust; need for external validation |

| Integrated system | Informed therapeutic decision | Simultaneous use of CADe and CADx in a single, non-interruptive workflow | Precise treatment plan | Optimizes workflow efficiency and standardizes quality of care across different operators | Clinical trial/commercial | Seamless integration into diverse healthcare environments; high development/maintenance costs; 'deskilling' risk for endoscopists; unclear regulatory/ethical frameworks for AI-assisted decisions |

Moreover, integrating AI with multimodal data (histology, biomarkers, genomics, and radiology) promises a deeper understanding of disease and the development of personalized treatments, potentially redefining disease progression and therapeutic planning[202,230].

AI also improves clinical trial efficiency and reliability by standardizing endoscopic evaluation, overcoming the subjectivity of human readers, and facilitating patient selection and stratification. This can reduce central reading costs, a significant component of trial budgets[231].

Despite its promise, AI faces several critical limitations and challenges for widespread implementation. Seamless integration of AI systems into daily clinical practice remains complex, requiring compatibility with diverse platforms and minimal workflow disruption, which can be challenging in heterogeneous healthcare environments[232].

Algorithm performance critically depends on the availability and quality of training data. Most studies are re

Endoscopist attitudes toward AI are generally positive, yet concerns persist regarding procedure time, operator dependence, and occupational safety. High rates of false positives can induce fatigue, distract the endoscopist, and prolong procedure time, potentially compromising quality. Implementation costs are also perceived as a major barrier. Additionally, there is a general lack of AI training among gastroenterologists. The “black box” nature of many AI models makes it difficult to understand how decisions are derived[232-234]. Understanding these processes, along with transparency, interpretability, and explainability, is crucial for clinical adoption and physician trust in AI recommendations. These aspects are discussed further in the section ‘Methodological Challenges and Limitations for Clinical Translation’.

Another significant limitation is operator dependence or “deskilling”. While AI serves as a supportive tool, their continuous use may inadvertently reduce the development and maintenance of essential technical and cognitive skills. AI systems are fundamentally dependent on adequate mucosal visualization and optimal endoscope handling; therefore, the endoscopist remains responsible for proper withdrawal technique, insufflation, washing, and lesion exposure. Excessive reliance on automated prompts could lead to poorer visual exploration habits, decreased vigilance in mucosal inspection, and reduced proficiency in recognizing subtle or atypical lesions without algorithmic guidance. This risk is compounded by false-positive detections, which can distract clinicians and promote a more passive or reactive approach during examinations. If endoscopists begin to expect the system to “flag” all relevant findings, attentional focus and diagnostic autonomy may decline over time. Furthermore, AI cannot detect lesions that remain outside the field of view, reinforcing that high-quality technique remains indispensable. Addressing the risk of deskilling will require structured training programs, continuous quality monitoring, and clear guidelines defining the appropriate balance between human expertise and algorithmic support[235,236].

Finally, unclear regulation and ethical considerations pose important barriers. Clear evidence standards, cost-effectiveness studies for funding, and robust ethical frameworks are needed to address data privacy, patient consent, and legal accountability for AI-assisted decisions. The absence of a well-defined regulatory framework is a common concern among endoscopists[202,233].

To overcome the limitations previously discussed, prospective, multicenter, large-scale studies are required to validate the reliability and reproducibility of AI algorithms across diverse clinical settings and patient populations, confirming their added value in real-world scenarios[202]. The development of multimodal models integrating endoscopic data with histopathological, clinical, radiological, and genomic information will provide a more comprehensive understanding of disease, enabling more accurate diagnoses, risk prediction, and personalized treatments[237,238]. Standardization of image acquisition techniques and the creation of high-quality shared databases will be fundamental to train more robust and generalizable AI algorithms.

It is expected that AI systems will become more intuitively integrated into clinical workflows, providing understandable and actionable insights to support clinical decision-making, rather than simply replacing the endoscopist. There is also growing interest in the use of LLMs for medical image interpretation, which could expand their applications to CADe, CADx, and Computer-Aided Quality assessment in endoscopy once the technology matures and regulatory and privacy challenges are addressed[239,240].

Beyond detection and characterization, new applications are anticipated, including AI-assisted insertion of robotic colonoscopes, anatomical recognition during advanced procedures (such as endoscopic submucosal dissection), prediction of surveillance intervals, and automated reporting[165].

AI is transforming both everyday life and modern medicine, and gastroenterology is no exception. Its ability to process and analyze the vast amounts of data generated in our specialty represents an unprecedented opportunity to advance toward precision, personalized, and efficient medicine. The potential use ranges from endoscopic imaging and radiology to molecular diagnostics and patient risk stratification. By integrating this information, AI can uncover patterns and insights that are often imperceptible to human observers, enabling earlier detection of disease, more accurate prognostication, and optimized therapeutic strategies.

There are areas where AI is already more implemented and standardized. Most endoscopy commercial platforms now include AI-assisted programs for endoscopists. Among all gastrointestinal subspecialties, endoscopy represents the most clinically mature area for AI integration, with multiple CADe and CADx systems already commercially available, regulated, and incorporated into routine practice. This level of technological adoption contrasts with the earlier developmental stage of most AI applications in hepatology, IBD, or neurogastroenterology, and provides a unique real-world benchmark for evaluating clinical impact, workflow integration, and safety considerations.

The use of CADe and CADx in endoscopy has demonstrated increased ADR, particularly among less experienced endoscopists[241]. Furthermore, CADx systems have improved lesion characterization, enabling the adoption of more efficient strategies such as “resect and discard” or “diagnose and leave”[162,242,243]. These approaches help avoid unnecessary follow-up of colonic polyps and reduce the number of samples sent for histopathological analysis, potentially alleviating workloads in often overburdened endoscopy units. However, as AI becomes increasingly embedded in endoscopic workflows, concerns have emerged regarding ‘deskilling’, whereby overreliance on automated CADe/CADx systems may erode the manual and cognitive skills required for optimal endoscopic performance. This risk is particularly relevant for pattern recognition, lesion characterization, and withdrawal technique, abilities that traditionally improve with experience. Mitigating deskilling will require balanced human, AI interaction, structured training strategies, and clear guidelines defining when AI support should complement, rather than replace, clinician expertise.

Although the use of CADe and CADx is well established, it remains necessary to further develop AI applications in other areas of endoscopy. Continued research and refinement of existing applications are essential. For example, AI-assisted detection of lesions in BE and early gastric cancer is critical due to the difficulty of visualization even for expert endoscopists[244,245]. Advancing these fields, as well as improving the existing systems, will enhance lesion detection and characterization and help minimize diagnostic errors.

AI enables automated interpretation of diagnostic tests such as high-resolution manometry, reducing physician subjectivity and interobserver variability while allowing detection of patterns imperceptible to the human eye. Additionally, AI integrates imaging data with numeric outputs from these tests, enhancing diagnostic accuracy[246].

Detection of advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, and the diagnosis and staging of HCC are some of the areas in which promising results are being achieved in hepatology. Non-invasive strategies with high reliability and accuracy appear particularly promising[247]. AI-based tools may facilitate early detection of patients with advanced fibrosis related to MASLD using routine ultrasound and laboratory alterations outperforming conventional noninvasive test such as FIB-4. Early identification will be highly significant, given the growing prevalence of MASLD, allowing preventive measures to reduce fibrosis progression and potential HCC development[248].

For HCC, AI focuses primarily on prognostic prediction and improved surveillance strategies. ML and DL models have been externally validated to predict overall survival and the risk of recurrence after liver transplantation or surgical resection. These models enhance the current staging systems by providing personalized risk stratification, enabling clinicians to make more informed decisions regarding treatment intensity and post-procedure follow-up. The im

For IBD, AI provides tools for objective and reproducible disease assessment, standardizing knowledge essential for research and development. AI applications are dual: Endoscopic assessment and prognostic modeling. AI allows quantification of inflammation and intestinal wall damage with high histologic correlation, enabling prediction of relapse risk[204]. Moreover, multimodal models integrating large datasets from various sources, along with clinical and laboratory data, facilitate the development of tools to predict biologic treatment response, advancing toward precision medicine[249].

Due to the high volume of images generated by CE, DL has been widely adopted to automate the detection of small-bowel lesions (e.g., vascular lesions, polyps, bleeding). AI systems significantly reduce the time required for human reading and minimize the risk of missing critical pathology. Performance studies demonstrate that AI-assisted analysis can achieve sensitivity and specificity comparable to, or even exceeding, expert gastroenterologists[217,218], positioning AI as a crucial tool for efficiency in this subspecialty.

To provide a concise overview of the robustness of the current evidence base, Table 5 summarizes the overall evidence levels across the major AI applications discussed in this review. The classification integrates key methodological dimensions, including study design, sample size, external validation, and real-world implementation status, to offer a high-level comparison of the relative maturity of each domain. This framework allows readers to quickly distinguish areas with stronger clinical validation, such as endoscopic CADe/CADx systems or certain radiology tools, from fields that remain largely exploratory, including multi-omics approaches, motility testing, or early-stage predictive models. The table aims to support a more transparent interpretation of the literature and to highlight where methodological strengthening is most needed for translation into clinical practice.

| Domain/application | Evidence level | Key determinants |

| Endoscopy (CADe/CADx) | High | Multiple FDA/CE-approved tools; prospective multicenter trials; real-time clinical use |

| Radiology (CT/MRI) | Moderate-high | External validation common; some multicenter cohorts; radiomics + DL pipelines |

| Non-invasive liver tests/fibrosis | Moderate | Mix of large cohorts + retrospective datasets; limited external validation except for FIB-6 |

| HCC detection and surveillance | Low-moderate | Early-stage models; heterogeneous metrics; mostly retrospective; few external validations |

| IBD (imaging, histology) | Moderate | Prospective validation for endoscopy/histology models; omics models still experimental |

| IBD multi-omics/transcriptomics | Low | Experimental; small cohorts; no external validation |

| Capsule endoscopy | Moderate | Strong DL performance; mostly single-center retrospective datasets |

| Motility testing/manometry | Low-moderate | Emerging field; small datasets; experimental DL approaches |

| Predictive models for complications | Low-moderate | Mostly retrospective; internal validation only |

| Implementation/regulation | - | Not applicable (conceptual section) |

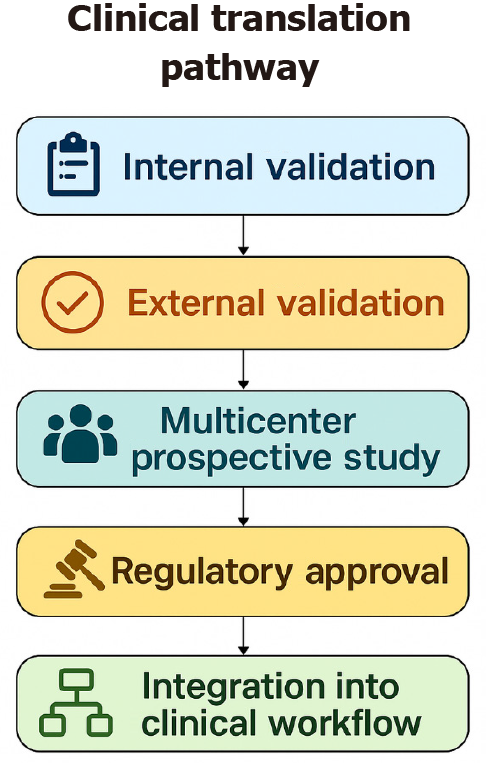

From a regulatory and implementation perspective, several AI tools have already reached clinical approval, illustrating the translational maturity of certain applications. In endoscopy, commercial CADe/CADx systems such as GI Genius™ (Medtronic; FDA-cleared and CE-marked) and ENDO-AID CADe (Olympus; CE-marked) are now incorporated into routine colonoscopy workflows, providing real-time polyp detection and characterization. In radiology, multiple FDA-cleared tools, including Aidoc’s triage algorithms for intracranial hemorrhage and pulmonary embolism, as well as Lunit INSIGHT for chest radiography and mammography (CE-marked), demonstrate how AI integration has progressed in other imaging-based specialties. To guide future implementations, we also expanded the discussion of recommended clinical-trial methodology for AI systems, including multicenter prospective designs, paired-reader studies, enriched cohorts, and the requirement for independent external validation. Key endpoints such as ADR for endoscopy, AUC, sensitivity, specificity, false-positive rate, time-to-diagnosis, and workflow or safety metrics are essential for regulatory evaluation and real-world adoption. Collectively, these examples and methodological considerations provide a clearer framework for evaluating AI tools as they transition from development to regulated clinical practice.

Beyond ethics and interpretability, the economic and environmental impacts of AI technologies must be considered. Training and deploying large-scale models require high-performance computational infrastructure, leading to substantial costs and a significant environmental footprint. In hospitals and healthcare systems, a critical evaluation of cost-benefit ratios and consideration of simpler solutions that achieve similar benefits with lower resource use is essential[250,251].

Methodological challenges and limitations for clinical translation: Across the different domains of gastroenterology and hepatology, several methodological issues consistently hinder the clinical translation of AI, and the reviewed literature shows substantial variability. Most published studies rely on retrospective, single-center dataset with limited sample sizes and heterogeneous data acquisition protocols. These restrict the generalizability of findings and increase the risk of overfitting. Prospective or multicenter designs remain uncommon and only performed in a minority of studies, which is a major limitation for rigorous external validation using independent cohorts, a prerequisite for reliable performance in real-world practice.

Studies outcomes are also often heterogeneous, with inconsistent definitions, non-standardized annotation processes, and variable handling of missing data. Potential sources of bias such as selection bias, spectrum bias, class imbalance, and dependence on proprietary preprocessing steps further limit interpretability. Although reported performance metrics are frequently high, these methodological weaknesses highlight the need for caution when extrapolating results to routine clinical practice.

Furthermore, many AI models, particularly DL architectures, operate as “black boxes”, providing little insight into the reasoning behind their predictions. This opacity complicates clinical interpretation, limits physician trust, and raises concerns regarding accountability in diagnostic errors. In recent years, explainability has become a central requirement for the safe and trustworthy deployment of AI systems in gastroenterology and hepatology. Beyond general references to the ‘black box’ problem, different methodological families of explainability are now being applied in biomedical AI, including feature-importance models, SHAP and LIME frameworks for structured data, and saliency or attention maps (e.g., Grad-CAM) for imaging-based applications. These techniques allow clinicians to visualize or quantify which elements of the input most strongly influence a prediction, facilitating model auditing, error analysis, and regulatory scrutiny. Nonetheless, current explainability tools present important limitations, such as instability across perturbations, risk of misinterpretation, and limited ability to reflect complex internal model representations, underscoring the need for cautious integration into clinical decision-making[252]. Clinical acceptance depends not only on interpretability but also on reliability, uncertainty calibration, and the extent to which AI systems integrate seamlessly into workflows without introducing cognitive overload. Prospective usability studies, continuous performance monitoring, and transparent reporting of model failures are increasingly recognized as essential steps to build physician confidence. Ultimately, explainability and acceptance are interdependent: Models that offer interpretable and consistent outputs are more likely to be trusted, adopted, and maintained in real-world clinical settings.

In clinical contexts, explainability refers not only to understanding which features contribute to a model’s prediction but also to ensuring that such explanations are meaningful, stable, and actionable for clinicians. It extends beyond algorithmic transparency and aims to provide insight into why an AI system issues a specific recommendation, enabling physicians to judge whether the output aligns with known pathophysiology and established diagnostic criteria. A known challenge is the performance-explainability trade-off: Highly interpretable models (e.g., logistic regression, decision trees) often offer lower accuracy in complex tasks such as image interpretation or multimodal prediction, whereas DL architectures achieve superior performance but provide limited insight into their internal reasoning. Managing this trade-off requires pragmatic strategies such as uncertainty calibration, model auditing, user-centered interface design, and hybrid pipelines that combine high-performing models with post hoc explainability tools. Concrete explainable AI (XAI) methods are increasingly used in gastroenterology research. Saliency maps and Grad-CAM have been applied in endoscopic and radiologic DL systems to highlight image regions that contribute most to polyp detection, BE dysplasia classification, or fibrosis staging, helping endoscopists verify whether the model attends to clinically relevant structures. SHAP values have been used in hepatology and IBD prediction models to quantify the contribution of laboratory values, transcriptomic signatures, and clinical variables to risk stratification outcomes[253,254]. LIME has been incorporated into machine-learning classifiers for clinical and laboratory datasets to provide patient-level explanations for treatment response prediction[253,255]. Attention-mapping mechanisms have been explored in transformer-based architectures for endoscopic video analysis, enabling visualization of the temporal frames the model prioritizes. Together, these ap

Additional barriers include imbalanced datasets, potential algorithmic bias, and insufficient reporting of calibration and clinical utility metrics, issues that collectively undermine reproducibility and regulatory acceptance. Addressing these cross-cutting challenges will be essential for achieving robust, explainable, and ethically sound integration of AI systems into routine digestive care. Finally, representativeness of populations used for model training and validation is critical in biomedical contexts. This validation is mostly limited to CADe and CADx endoscopy models. If datasets do not reflect real patient diversity, predictions may be biased and exacerbate disparities in diagnostic and treatment access. Multicenter validation across diverse clinical and population settings is necessary to ensure generalizability[256,257]. Technologies such as federated learning, which enable collaborative model training without sharing sensitive patient data, will be crucial to overcome privacy and data scarcity barriers[258].

The near future points to deeper integration of AI into clinical practice. The emergence of generative AI and LLMs adds a new dimension, with applications in report generation, medical record synthesis, and patient communication[259,260]. Multimodal models combining imaging, genomics, microbiota, and clinical records may allow the creation of true “digital twins” of patients, capable of simulating disease progression and predicting therapeutic responses individually[261]. This would free clinicians to focus more on direct patient care, reducing administrative burdens.

As observed, the incorporation of AI, particularly LLMs, in medicine raises challenges beyond technical algorithm performance. Each subspecialty faces unique considerations. The different areas of the specialty all share this, although each obviously has its own peculiarities. It is not the same to deal only with images as dealing with personal data from medical records. A central concern is ethical. AI use carries risks related to data privacy and security, the potential replication of biases present in training datasets, and the need for clear accountability when AI-assisted predictions or recommendations contribute to clinical errors[262,263]. Ensuring equitable access, transparency, and accountability is essential for safe implementation.

Another critical challenge is the “black box” phenomenon. Many advanced models, especially in DL and LLMs, operate opaquely, making internal logic difficult to interpret even for developers. This lack of explainability limits acceptance among healthcare professionals, who need to understand the basis of recommendations before integrating them into practice[264,265]. XAI techniques, such as Grad-CAM and SHAP, have been proposed to increase transparency by visualizing which data features most influence model decisions, fostering clinical trust[266,267].

Integration of AI in medicine cannot be approached solely from a technical perspective. Its success depends on a development and implementation framework that prioritizes ethics, transparency, sustainability, and equity, ensuring that AI tools serve as reliable and responsible support for clinical practice.