Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.115063

Revised: November 12, 2025

Accepted: December 16, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 128 Days and 22.5 Hours

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) may progress to cirrhosis and lead to serious complications. Lipid accumulation, hepatocellular ballooning, and sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction increase intrahepatic vascular resistance, resulting in early clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH). Al

A 78-year-old woman with class I obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia presented with hematemesis and melena for a three-day period. A prior computed tomography scan revealed moderate diffuse hepatic steatosis, splenic vein dilatation, and splenomegaly. On admission, she presented with pallor, epig

Early and precise evaluation of CSPH in geriatric MAFLD requires an integrated clinical assessment to optimize diagnosis, management, and improve outcomes.

Core Tip: Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a chronic condition characterized by excess fat accumulation in the liver along with at least one cardiometabolic risk factor. MAFLD can progress silently to liver cirrhosis, often without noticeable symptoms, until clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) develops. CSPH can develop early in MAFLD, even before advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis sets in. We reported a case of a geriatric patient with MAFLD who had CSPH. Following variceal ligation and medical treatment, the patient showed notable improvement. However, diagnosing such cases in daily clinical practice remains quite challenging.

- Citation: Akbar FN, Darnindro N, Wardhani AA, Choirida SR, Saphira SN, Ismed G, Kshanti IAM, Mustika S, Hendarto H. Diagnostic challenges of clinically significant portal hypertension in geriatric metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: A case report. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 115063

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/115063.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.115063

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is a chronic condition characterized by excessive fat accumulation in the liver along with at least one car

MAFLD is increasingly common worldwide, affecting approximately 30% of the global population, while the pre

MAFLD can silently progress to cirrhosis, often without symptoms, until clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) develops[2,4]. CSPH complications-such as esophageal varices, splenomegaly, and ascites-occur in approximately 25% of MAFLD patients. Previous studies suggest that portal hypertension may occur early in some MAFLD cases-particularly those with sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction or parenchymal alterations-even before the onset of significant fibrosis or cirrhosis[2,3]. The aim of this report is to highlight the diagnostic challenge and management of CSPH in geriatric MAFLD.

A 78-year-old woman with class I obesity and unhealthy dietary habits presented with a history of hematemesis and melena for a three-day period.

Hematemesis and melena for a three-day period.

Four years earlier, she had experienced recurrent upper abdominal discomfort and bloating. She underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT) that demonstrated features of chronic liver disease with diffuse hepatic steatosis, splenomegaly, and splenic vein dilatation. She also had an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed portal hypertensive gastropathy and multiple gastric ulcers without a history of gastrointestinal bleeding.

The patient had no significant family medical history and denied the use of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs.

The patient had stable hemodynamics and body mass index (BMI) was 30.5 kg/m2. The examination presented with pallor, epigastric tenderness, splenomegaly, and mild ascites.

Blood tests showed anemia (hemoglobin 9.2 g/dL; normal range: 11.7-15.5 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (50000/μL; normal range: 150000-440000/μL), hypoalbuminemia (2.2 g/dL; normal range: 3.5-5.2 g/dL), and impaired liver function [aspartate transaminase (AST) 45 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 52 IU/L; normal range: AST < 38 IU/L, ALT < 30 IU/L]. The results also showed prolonged coagulation time (activated partial thromboplastin time 36.0 seconds; normal range: 25.0-33.0 seconds and prothrombin time 20.6 seconds; normal range: 11.7-15.1 seconds) and elevated random blood glucose (202 mg/dL; normal range: < 200 mg/dL), while the glycated hemoglobin level was 7.0% (normal range: < 5.7%-6.5%), within the targeted glycemic range for patients with MAFLD. Tests for viral hepatitis B and C, including the hepatitis B core antigen, were non-reactive.

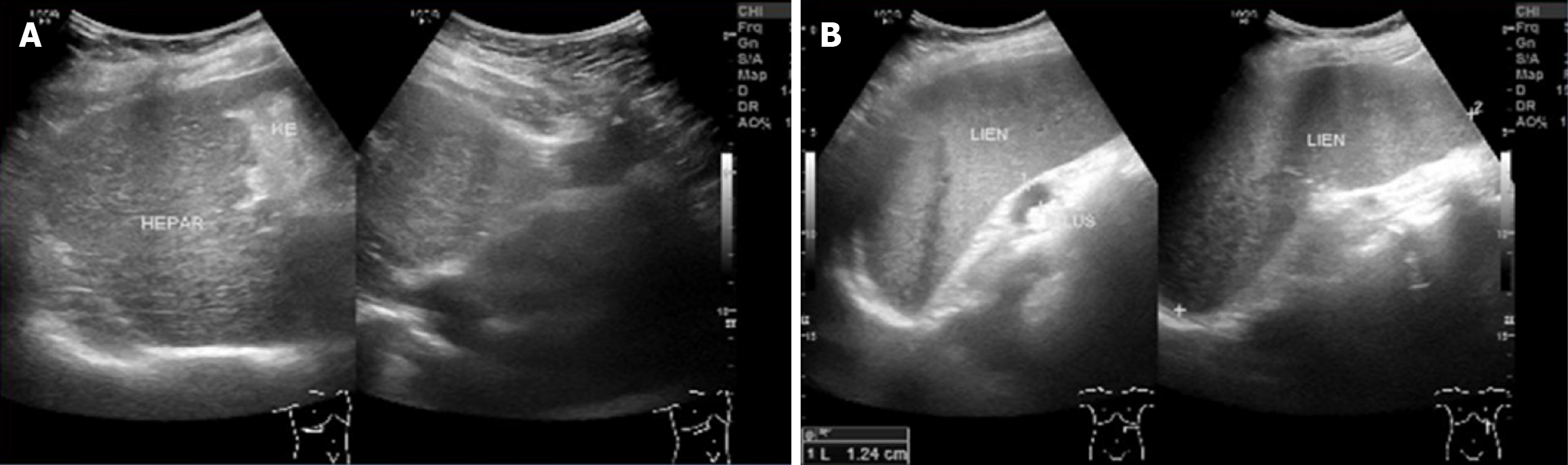

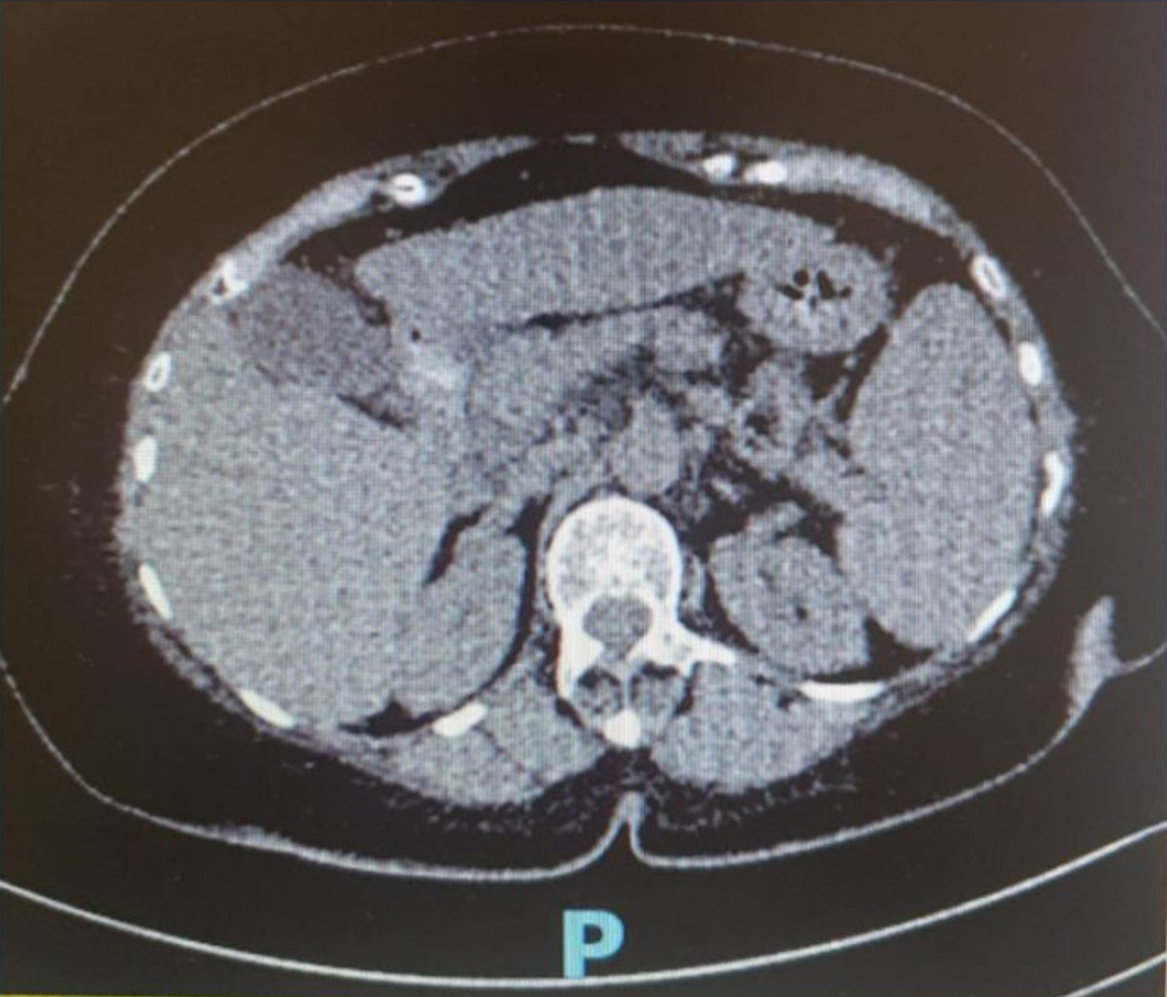

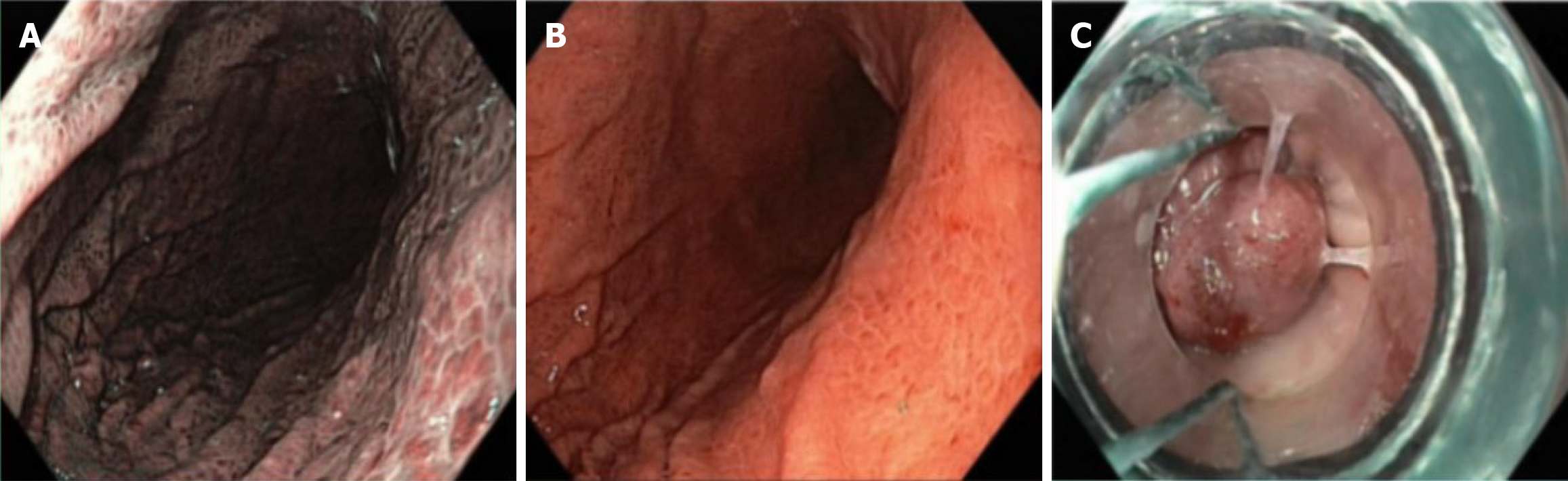

She underwent an abdominal ultrasonography (US) which showed multiple gallstones, the largest measuring 7.4 mm, along with features of chronic liver disease suggestive of liver cirrhosis and splenomegaly (Figure 1). Repeated abdominal CT (Figure 2) demonstrated mild to moderate diffuse hepatic steatosis, splenomegaly, and several gallstones-the largest measuring 8.95 mm × 5.26 mm-accompanied by signs of cholecystitis. She also underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy which showed grade II-III esophageal varices, moderate portal hypertensive gastropathy, and multiple gastric ulcers (Figure 3). Her transient elastography (FibroScan) revealed a hepatic stiffness measurement of 28 kPa, consistent with advanced fibrosis (METAVIR stage F4), and a normal controlled attenuation parameter value of 191 dB/m. Noninvasive fibrosis scoring systems-including the NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS), AST-to-platelet ratio index (APRI), and fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4)-also supported the presence of advanced hepatic fibrosis.

Based on her medical history, physical examination, laboratory findings, imaging, and endoscopic evaluation, the patient was diagnosed with MAFLD and chronic liver disease suggestive of early cirrhosis (Table 1). She presented with grade II-III esophageal varices secondary to CSPH, in the context of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and class I obesity. The differential diagnoses included non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, cirrhotic portal hypertension secondary to chronic hepatitis, and splenic vein thrombosis.

| Time | Clinical events and findings |

| 4 years before admission | The patient experienced recurrent upper abdominal discomfort and bloating. Abdominal CT showed chronic liver disease with fatty changes, splenomegaly, and splenic vein dilatation. Endoscopy revealed portal hypertensive gastropathy and multiple gastric ulcers without prior bleeding |

| 3 days before admission | The patient developed hematemesis and melena |

| Day 0 (admission) | Stable hemodynamics, BMI 30.5 kg/m2. Presented with pallor, epigastric tenderness, splenomegaly, and minimal ascites. Laboratory tests revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, prolonged prothrombin time, impaired liver function, and hyperglycemia. Viral hepatitis markers were negative |

| During hospitalization | Abdominal ultrasound showed features of chronic liver disease, splenomegaly, and multiple gallstones. CT confirmed moderate diffuse hepatic steatosis, splenic vein dilatation, and splenomegaly. Upper GI endoscopy demonstrated grade II-III esophageal varices and moderate portal hypertensive gastropathy. FibroScan (E = 28 kPa; CAP = 191 dB/m) and noninvasive fibrosis scores (NFS, APRI, FIB-4) indicated advanced fibrosis (METAVIR F4) |

| Treatment phase | Endoscopic variceal ligation at five sites. Received carvedilol 12.5 mg once daily, rosuvastatin 10 mg once daily, empagliflozin 75 mg once daily, long-acting insulin glargine 10 units daily, a proton pump inhibitor, and a mucous protector lifestyle modifications were also initiated |

| 2-week follow-up | Clinical improvement noted with resolution of abdominal pain, vomiting, and bloating. No recurrent bleeding was observed. The patient remained stable on follow-up |

The patient underwent endoscopic variceal ligation at five sites, with minimal bleeding. After the procedure, she received a proton pump inhibitor, mucous protector, vitamin K, and a liquid diet. Additional treatments to address metabolic risk factors and portal hypertension included carvedilol 12.5 mg once daily, rosuvastatin 10 mg once daily, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor empagliflozin 75 mg once daily, and long-acting insulin glargine 10 units once daily.

The patient underwent esophageal variceal ligation without any complications and tolerated the procedure well. At her two-week follow-up, she reported marked improvement in abdominal pain, vomiting, and bloating, with stable clinical and metabolic parameters.

Liver fibrosis, a recognized long-term consequence of MAFLD, was observed in this patient with class I obesity (BMI 30.5 kg/m²) and type 2 diabetes. This progressive condition may advance to cirrhosis and predispose to complications such as CSPH.

Clinical evaluation is essential for assessing liver fibrosis and identifying signs and symptoms of cirrhosis, including CSPH[2,3]. The first step in detecting liver fibrosis should include non-invasive blood-based scores such as the FIB-4, APRI, or NFS, together with imaging modalities such as ultrasound, transient elastography, or magnetic resonance-based elastography[1,4,5]. The patient tested negative for chronic viral hepatitis, indicating that the cause of her compensated advanced liver disease (cALD) was most likely MAFLD.

CSPH in MAFLD may develop at an early stage due to fat accumulation, hepatocellular ballooning, cellular injury, and sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction, which collectively induce hepatic microvascular contraction, increase intrahepatic vascular resistance, and reduce hepatic blood flow[1,4,6]. These pathophysiological alterations suggest that CSPH can occasionally occur before advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis develops. Additionally, this patient had type 2 diabetes, which caused insulin resistance-an extrahepatic factor that further impaired hepatic microcirculation and contributed to early portal hypertension[1,6].

The patient exhibited clear features of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, esophageal varices, and thrombocytopenia, despite the absence of overt cirrhotic changes on abdominal CT. This discrepancy likely reflects the inability of CT imaging to detect microscopic fibrosis or early sinusoidal alterations. Typically, cirrhotic morphology becomes apparent on CT only when advanced structural changes, such as a nodular hepatic surface, lobar volume redistribution, or large portosystemic collaterals, are present[2]. This finding underscores the limitations of conventional imaging and supports a comprehensive diagnostic strategy combining noninvasive assessment, endoscopic evaluation and clinical judgment especially in elderly and obese in MAFLD patients.

Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is invasive assessment, remains the gold standard for assessing portal hypertension, determined by the difference between wedged and free hepatic venous pressures (median of three re

In compensated cirrhosis, HVPG accurately reflects portal pressure, but in decompensated cirrhosis, architectural distortion and intrahepatic shunting may lead to underestimation. This discrepancy may result from persistent intersinusoidal communications, heterogeneous fibrosis, and pre-sinusoidal components associated with lipid-induced en

In compensated MAFLD with severe steatosis CSPH threshold (< 10 mmHg) often deceptively low, potentially below the standard despite true elevated portal pressure, while decompensated MAFLD with severe steatosis generally higher than the compensated stage, but still potentially underestimates the true severity of portal hypertension compared to other etiologies at a similar clinical stage[2,3,13,14]

Early hemodynamic alterations may occur before significant fibrosis develops, especially in those with sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction or reduced hepatic perfusion, leading to CSPH[2,10-12]. Severe steatosis that fundamentally alters hepatic hemodynamics, highlighting the need for alternative or complementary tools-such as non-invasive measurements, including transient elastography and platelet count, provide valuable diagnostic support[3,13].

In this case, HVPG measurement was not performed due to its invasiveness and limited availability. The diagnosis of CSPH was therefore established according to the Baveno VII consensus, which defines CSPH as a liver stiffness measurement (LSM) ≥ 25 kPa combined with a platelet count < 150 × 109/L. Conversely, the new Baveno VII criteria LSM ≤ 15 kPa with platelet counts ≥ 150 × 109/L can exclude CSPH with high accuracy in patients with compensated advanced liver disease [transient elastography (TE) > 10 kPa], including those with NASH, with over 90% sensitivity[2,3,15-17]. This case highlights the evolving diagnostic approach to CSPH in MAFLD, emphasizing integrated clinical assessment and stage-specific interpretation.

These criteria offer a safer and more practical approach to exclude CSPH, reducing the need for invasive procedures in early MAFLD-related liver disease. In viral- and alcohol-related cALD and non-obese NASH, a LSM ≥ 25 kPa can reliably confirm CSPH with more than 90% specificity and positive predictive value[2]. However, this cutoff may be less accurate in obese NASH, as obesity can overestimate liver stiffness due to technical limitations and fat infiltration, leading to falsely elevated readings despite non-significant portal pressure. Based on these criteria, this patient-with an LSM of 28 kPa, thrombocytopenia of 50000/μL, and class I obesity-fulfilled the diagnostic threshold for CSPH. This non-invasive approach aligns with current Baveno VII recommendations for evaluating portal hypertension when HVPG measurement is unavailable.

Spleen stiffness measurement and Doppler ultrasound can non-invasively detect portal hypertension and the presence of esophageal varices[2,9]. In portal hypertension, an enlarged spleen affects spleen stiffness because of congestion, cellular proliferation, and fibrosis, which can be measured using TE, shear wave elastography, or magnetic resonance elastography (MRE)[2,9]. Doppler ultrasound shows that higher grades of liver steatosis are associated with slower portal vein blood flow and increased hepatic arterial flow[10,11]. A multicenter study demonstrated that measuring liver stiffness with MRE can distinguish between decompensated and compensated cirrhosis related to MAFLD, with an area under the curve of 0.707[12]. A liver biopsy is not required for clinical diagnosis; however, if the etiology is uncertain, a biopsy may help differentiate among possible underlying conditions[2].

The main diagnostic challenge was also identifying the source of the patient’s upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Given her background of chronic liver disease, splenomegaly, and prior portal hypertensive gastropathy, variceal bleeding was the leading suspicion. Other possible causes, including non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, cirrhotic portal hypertension secondary chronic hepatitis, non-variceal portal hypertensive gastropathy, malignancy, and splenic vein thrombosis were also considered. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy confirmed grade II-III esophageal varices with moderate portal hypertensive gastropathy, ruling out active peptic ulcers or malignancy and confirming variceal hemorrhage secondary to portal hypertension. Initial management focused on stabilization with intravenous fluids and blood transfusion[1-3].

Endoscopic variceal ligation was successfully performed to control bleeding. Her diabetes was managed using long-acting insulin and empagliflozin, providing both glycemic and cardiovascular benefits. Long-term follow-up emphasized lifestyle modification, strict metabolic control, and regular endoscopic surveillance[1-3].

Comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment is essential for MAFLD management[1]. The goal of MAFLD management is to prevent further fat accumulation, reverse existing steatosis, improve and stabilize fibrosis, and reduce the risk of developing liver cancer[1,2]. Non-pharmacological approaches, including a healthy diet that limits ultra-processed, sugary, and high-fat foods, along with lifestyle changes, can help reduce body weight by 7%-10%, decrease liver fat by more than 5%, and lower inflammation and fibrosis[1,13]. MAFLD patients are advised to exercise for 150-175 minutes per week at moderate intensity[1,18].

In patients with compensated cirrhosis from various etiologies, obesity is a strong predictor of disease progression, regardless of HVPG levels and albumin concentration[1,2,4,5]. Non-selective beta-blockers (NSBBs) such as propranolol, carvedilol, or nadolol help reduce portal pressure, decrease intestinal permeability, and limit bacterial translocation, thereby lowering variceal bleeding risk to prevent disease progression and improve survival[18]. Carvedilol is the preferred NSBB in compensated cirrhosis because it effectively reduces portal pressure without adversely affecting insulin sensitivity, glycemia, or lipid profiles-an important consideration for MAFLD patients with metabolic com

Variceal bleeding requires prompt treatment with endoscopic therapy, vasoactive agents to reduce portal flow, and prophylactic antibiotics[3]. For high-risk or recurrent cases, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt can be considered[20,21].

Comprehensive, personalized management should address both the underlying etiologies and complications of portal hypertension. A multidisciplinary approach involving hepatologists, dietitians, and transplant specialists is essential to improve outcomes in cirrhosis[1].

CSPH in MAFLD may develop before advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis due to sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction. Noninvasive markers (TE ≥ 25 kPa and platelet count < 150 × 109/L) met Baveno VII criteria for CSPH when HVPG is unavailable. In elderly MAFLD patients, overlapping metabolic and aging-related factors complicate diagnostic assessment. Early recognition and management of CSPH reduces the risk of variceal bleeding and liver decompensation. Abdominal US and CT have limited to diagnose liver in cirrhosis in geriatric, obesity and diabetic MAFLD.

The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in geriatric patients with MAFLD presents a significant challenge while CSPH in MAFLD may develop before advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis due to sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction. Invasive diagnostic such as HVPG and noninvasive diagnostic criteria by Baveno VII, supported clinical reasoning, enabled accurate diagnosis and treatment. Abdominal US and CT have limited to diagnose liver in cirrhosis in geriatric, obesity and diabetic MAFLD. Therefore, future advancements should focus to enhance awareness and expertise in managing this important health concern, with particular emphasis on the prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma to avoid progression to end-stage disease. Understanding these diagnostic pitfalls and incorporating individualized, invasive and non-invasive evaluation can improve early detection and management outcomes in geriatric MAFLD especially the variceal bleeding caused by CSPH and hepatic decompensation.

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. 2024;81:492-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 979] [Article Influence: 489.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Nababan SHH, Lesmana CRA. Portal Hypertension in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Pathogenesis to Clinical Practice. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10:979-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Madir A, Grgurevic I, Tsochatzis EA, Pinzani M. Portal hypertension in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Current knowledge and challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:290-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 4. | Eslam M, Fan JG, Yu ML, Wong VW, Cua IH, Liu CJ, Tanwandee T, Gani R, Seto WK, Alam S, Young DY, Hamid S, Zheng MH, Kawaguchi T, Chan WK, Payawal D, Tan SS, Goh GB, Strasser SI, Viet HD, Kao JH, Kim W, Kim SU, Keating SE, Yilmaz Y, Kamani L, Wang CC, Fouad Y, Abbas Z, Treeprasertsuk S, Thanapirom K, Al Mahtab M, Lkhagvaa U, Baatarkhuu O, Choudhury AK, Stedman CAM, Chowdhury A, Dokmeci AK, Wang FS, Lin HC, Huang JF, Howell J, Jia J, Alboraie M, Roberts SK, Yoneda M, Ghazinian H, Mirijanyan A, Nan Y, Lesmana CRA, Adams LA, Shiha G, Kumar M, Örmeci N, Wei L, Lau G, Omata M, Sarin SK, George J. The Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int. 2025;19:261-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li B, Zhang C, Zhan YT. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Cirrhosis: A Review of Its Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, Management, and Prognosis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:2784537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Miao L, Targher G, Byrne CD, Valenti L, Qi X, Zheng M. Portal hypertension in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Challenges and perspectives. Port Hypertens Cirrhos. 2022;1:57-65. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lu Q, Leong S, Lee KA, Patel A, Chua JME, Venkatanarasimha N, Lo RH, Irani FG, Zhuang KD, Gogna A, Chang PEJ, Tan HK, Too CW. Hepatic venous-portal gradient (HVPG) measurement: pearls and pitfalls. Br J Radiol. 2021;94:20210061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zulkifly S, Hasan I. Non-Cirrhotic Portal Hypertension: An Update of Diagnosis and Management. Indones J Gastroenterol Hepatol Dig Endosc. 2023;24:143-153. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Muzica C, Diaconu S, Zenovia S, Huiban L, Stanciu C, Minea H, Girleanu I, Muset M, Cuciureanu T, Chiriac S, Singeap AM, Cojocariu C, Trifan A. Role of Spleen Stiffness Measurements with 2D Shear-Wave Elastography for Esophageal Varices in Patients with Compensated Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025;15:674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ferrusquía-Acosta J, Bassegoda O, Turco L, Reverter E, Pellone M, Bianchini M, Pérez-Campuzano V, Ripoll E, García-Criado Á, Graupera I, García-Pagán JC, Schepis F, Senzolo M, Hernández-Gea V. Agreement between wedged hepatic venous pressure and portal pressure in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;74:811-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Galizzi HO, Couto CA, Taranto DOL, Araújo SIO, Vilela EG. Accuracy of non-invasive methods/models for predicting esophageal varices in patients with compensated advanced chronic liver disease secondary to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2021;20:100229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Han MAT, Vipani A, Noureddin N, Ramirez K, Gornbein J, Saouaf R, Baniesh N, Cummings-John O, Okubote T, Setiawan VW, Rotman Y, Loomba R, Alkhouri N, Noureddin M. MR elastography-based liver fibrosis correlates with liver events in nonalcoholic fatty liver patients: A multicenter study. Liver Int. 2020;40:2242-2251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 13. | Suk KT. Hepatic venous pressure gradient: clinical use in chronic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014;20:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Sathawane A, Khobragade H, Pal S. Correlation of Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradient Level With Clinical and Endoscopic Parameters in Decompensated Chronic Liver Disease. Cureus. 2023;15:e51154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rivera-Esteban J, Barberá A, Salcedo MT, Martell M, Genescà J, Pericàs JM. Liver steatosis induces portal hypertension regardless of fibrosis in patients with NAFLD: A proof of concept case report. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ryou M, Stylopoulos N, Baffy G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and portal hypertension. Explor Med. 2020;1:149-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Paternostro R, Kwanten WJ, Hofer BS, Semmler G, Bagdadi A, Luzko I, Hernández-Gea V, Graupera I, García-Pagán JC, Saltini D, Indulti F, Schepis F, Moga L, Rautou PE, Llop E, Téllez L, Albillos A, Fortea JI, Puente A, Tosetti G, Primignani M, Zipprich A, Vuille-Lessard E, Berzigotti A, Taru MG, Taru V, Procopet B, Jansen C, Praktiknjo M, Gu W, Trebicka J, Ibanez-Samaniego L, Bañares R, Rivera-Esteban J, Pericas JM, Genesca J, Alvarado E, Villanueva C, Larrue H, Bureau C, Laleman W, Ardevol A, Masnou H, Vanwolleghem T, Trauner M, Mandorfer M, Francque S, Reiberger T; a study by the Baveno Cooperation: an EASL consortium. Hepatic venous pressure gradient predicts risk of hepatic decompensation and liver-related mortality in patients with MASLD. J Hepatol. 2024;81:827-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Akbar FN, Choirida SR, Muttaqin AZ, Ekayanti F, Nisa H, Hendarto H. Telemedicine as an Option for Monitoring Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) Patients Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pers Med. 2024;14:281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rodrigues SG, Mendoza YP, Bosch J. Beta-blockers in cirrhosis: Evidence-based indications and limitations. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Amorim R, Soares P, Chavarria D, Benfeito S, Cagide F, Teixeira J, Oliveira PJ, Borges F. Decreasing the burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: From therapeutic targets to drug discovery opportunities. Eur J Med Chem. 2024;277:116723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shalaby S, Nicoară-Farcău O, Perez-Campuzano V, Olivas P, Torres S, García-Pagán JC, Hernández-Gea V. Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) for Treatment of Bleeding from Cardiofundal and Ectopic Varices in Cirrhosis. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/