Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113686

Revised: September 28, 2025

Accepted: December 16, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 165 Days and 1.6 Hours

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection commonly occurs in children, particularly in developing countries. Most children infected with EBV are asymptomatic, though some develop significant complications, including EBV-associated malignancies, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and multiple sclerosis. In immunocompromised children, including those with liver transplantation, EBV infection manifests with a diverse spectrum of presentations, varying from asymptomatic to post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, which can evolve into lymph

Core Tip: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is common and can cause serious complications in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Young children who are EBV-seronegative are at especially increased risk because primary infection or viral reactivation may progress to post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Routine EBV viral load monitoring, timely immunosuppressive therapy adjustment, and early intervention are crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality. A deeper understanding of EBV pathogenesis, combined with individualized management strategies, is essential for improving long-term outcomes in this high-risk population.

- Citation: Onpoaree N, Leelakanok N, Sanpavat A, Sintusek P. Epstein-Barr virus infection in children with liver transplantation. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 113686

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/113686.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113686

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous human γ-herpesvirus that establishes lifelong latency after primary infection. EBV infection is usually asymptomatic or manifests as self-limiting infectious mononucleosis in immunocompetent individuals. However, EBV infection assumes greater clinical significance in immunocompromised individuals, particularly pediatric liver transplant recipients, due to impaired T-cell-mediated immune surveillance. The combination of chronic immunosuppression, young recipient age, and EBV seronegativity at the time of transplantation increases the risk of primary EBV infection or uncontrolled viral reactivation.

In pediatric liver transplant recipients, EBV infection is not only a common post-transplant complication but also a significant risk factor for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), which is a life-threatening spectrum ranging from benign polyclonal lymphoid hyperplasia to aggressive lymphoma. The clinical manifestations of EBV infection in this population are highly variable, including asymptomatic viremia, fever of unknown origin, hepatitis, gastrointestinal disease, and multi-organ involvement. Therefore, early recognition and vigilant monitoring of EBV viral load are necessary for guiding immunosuppression adjustments and enabling timely pre-emptive interventions before disease progression.

EBV infection is defined as the presence of active EBV replication detected by serology or nucleic acid testing, with or without disease. Serology testing includes non-specific heterophile antibody tests and specific antibody assays targeting EBV-associated antigens, such as viral capsid antigen (VCA), early antigen, and EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA). The molecular techniques include quantitative assays for circulating EBV DNA.

EBV disease is an EBV infection that contributes to a broad spectrum of clinical pathologies, including infectious mononucleosis. Typical manifestations include flu-like symptoms, otitis media, cervical lymphadenopathy, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, pneumonitis, encephalitis, and hepatitis. However, in immunocompromised hosts, EBV-driven B-cell proliferation may progress to end-organ diseases (e.g., hepatitis and enteritis) from benign hyperplasia to malignant lym

Primary infection is defined as the first EBV infection. Exposure is commonly through bodily fluids, especially saliva. Other transmission routes include sexual contact, blood transfusion, and organ transplantation. After primary infection, EBV establishes latency within the host and persists in an inactive form.

Reactivation is defined as the recurrence of viral replication from latency, typically occurring with immunosuppression, such as human immunodeficiency virus infection and immunosuppressive therapies, or after solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

PTLD is defined as a diverse spectrum of lymphoid and plasmocytic proliferations in the context of post-transplant immunosuppression. In pediatric liver transplantation, PTLD is predominantly EBV-driven, most often following primary EBV infection or EBV reactivation. Importantly however, EBV-negative PTLD is now well-recognized, especially in adults after solid organ transplant, where recent cohorts report EBV-negative disease in up to approximately 48% of PTLD cases[1].

According to the World Health Organization classification, PTLD is categorized into four major subtypes[2]: (1) Early lesions/non-destructive PTLD: Plasmocytic hyperplasia, florid follicular hyperplasia, and infectious mononucleosis-like PTLD; (2) Polymorphic PTLD: Polymorphic lymphoproliferative disorders arising from immune deficiency/dysregulation; (3) Monomorphic PTLD, including B-cell, T-cell, and natural killer (NK) cell types; (4) Classic Hodgkin lymphoma-like PTLD. Additionally, PTLD exhibits a bimodal distribution. Therefore, it can be classified based on the time of onset into[3]; (5) Early-onset PTLD: Cases diagnosed within the first year after solid organ transplantation; and (6) Late-onset PTLD: Cases diagnosed beyond 1 year after solid organ transplantation.

EBV is one of the most prevalent human viruses worldwide, and its seroprevalence increases with age. In Eastern countries, the seropositive prevalence is generally high and increases steadily over time. During the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, a Chinese children cohort study reported a total seropositive rate of EBV infections of 61.0% between January 2019 and December 2021[4]. A more recent study on a general population Jordanian cohort of 1507 showed that the seropositive rates were 70.6% in children aged < 5 years and 89.1% in those aged 15-19 years between December 2021 and August 2022[5]. In Thailand, a seroepidemiologic survey revealed a seroprevalence of 35.9% in children aged 6 months to 2 years and nearly 100% in adolescents[6]. These findings indicate that increased EBV seroprevalence with age may be due to the mode of transmission (gradual exposure over time to saliva, close contact, or fomites in toys), whereas the high prevalence in early infancy may be due to another mode of transmission (passive mother-to-child antibody transmission). However, antibody levels may wane over time. Additionally, crowded environments and early daycare attendance at a young age may contribute to high seropositivity[7].

In Western countries, the EBV seroprevalence is similarly high and increases with age. However, the rise tends to occur more gradually compared with the Eastern population. A recent study on a cohort of French patients showed an overall seroprevalence of 90% between January 2013 and December 2023, reaching approximately 97% in adults aged > 25 years[8]. In a Croatian general population cohort, the seroprevalence ranged from 59.6% in children aged < 6 years to 98.3% in adults aged 30-39 years[9]. This may reflect socioenvironmental factors.

Recent cohort studies have demonstrated marked differences in EBV seroprevalence between pediatric liver transplant recipients in Eastern and Western countries. In Eastern countries, such as Japan, China, and Turkey, EBV seroprevalence at the time of transplantation has been reported to be 65%-80%[10,11]. Conversely, lower rates have been reported in Western countries, such as the United States and Europe, ranging from 20% to 50%[12]. These discrepancies may be related to age at transplantation and lower seroprevalence among donors in Western countries.

A large proportion of pediatric liver transplant recipients who are EBV-seronegative at the time of transplantation subsequently undergo seroconversion[13-15]. A Japanese cohort study reported that 80% of seronegative children developed EBV seropositivity within 2 years after transplantation[16]. These findings underscore the importance of rigorous EBV serological screening and longitudinal monitoring in pediatric liver transplant candidates, particularly in younger recipients who are at higher risk of primary EBV infection after transplantation.

The reported incidence of PTLD in pediatric liver transplant recipients varies widely across studies, ranging from approximately 4% to 11.7%, with most cases being EBV-related[17,18]. A recent 2025 study from the Swiss Pediatric Liver Center reported a relatively high PTLD incidence of 11.7% and proposed a diagnostic and management algorithm incorporating early whole-body positron emission tomography (PET)-computed tomography (CT) to guide targeted tissue biopsy, which likely contributed to the high detection rate of PTLD in this study[18]. Another large multicenter cohort demonstrated a PTLD prevalence of 5.1% (45/1849) in children compared with 2.3% (22/1849) in adults[19]. EBV-negative PTLD remains uncommon in children. For example, one study reported PTLD in 3.4% (7/206) of pediatric liver transplant recipients, of which only two cases were EBV-related, underscoring the rarity of EBV-negative disease in this population[20]. The variability in reported PTLD incidence likely reflects a combination of factors, including immunogenetic background and differing EBV seroprevalence patterns across populations (Asia and Western countries) and age groups, center-specific experience, surveillance strategies, and diagnostic thresholds and variation in immunosuppressive protocols, particularly tacrolimus exposure, which has been associated with increased PTLD risk.

The pre-transplant EBV serostatus of recipients is the most important determinant of PTLD development. EBV-seronegative recipients with a donor-recipient EBV mismatch pair [donor-positive/recipient-negative (D+/R-)] are at the highest risk for EBV infection after transplantation, which in turn carries a very high risk of developing EBV-associated PTLD. A prospective multi-center cohort study of 944 children found a sub-hazard ratio of 2.79 for D+/R-[13]. A previous study showed that the incidence of seronegativity pre-transplant among patients with PTLD is 80%[21]. Data from the Organ Procurement Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing showed that the adjusted hazard ratio of PTLD in the D+/R- subpopulation was 17.39 within a 3-year follow-up. In an Asian cohort, 15 of 16 cases occurred in EBV-seronegative recipients, highlighting the vulnerability of EBV-naïve children[14]. In another study of 236 pediatric patients who underwent liver transplantation, the incidence of PTLD was 10% among seronegative recipients and only 0.8% among seropositive recipients[22].

The risk of PTLD is inversely associated with recipient age and it is correlated with a higher proportion of younger children[10]. Data from Organ Procurement Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing showed that the adjusted hazard ratio of PTLD was 2.01 in patients aged < 18 years and 0.40 in those aged 18-40 years[23]. This age group is usually recipients of older donors, which has been reported to have an increased seroprevalence and may lead to a donor-recipient EBV mismatch pair.

The incidence of PTLD is highest in multi-organ transplant and multi-visceral organ transplant recipients (up to 20%), followed by lung and heart transplant recipients (up to 15%)[23]. Conversely, the incidence of PTLD is the lowest in liver and kidney transplant recipients (range from 3.5% to 11.7%)[24,25]. According to a prospective multi-center cohort study, intestinal transplantation is a strong risk factor for PTLD development, with a sub-hazard ratio of 5.29, compared with liver transplantation[13]. This may be attributed to the need for stronger and more prolonged immunosuppressive therapy during the induction phase in lung, heart, and multi-visceral organ transplantation.

A higher EBV viral load is significantly associated with a higher incidence of PTLD after liver transplantation[21,26]. A single-center retrospective cohort study of 112 pediatric post-liver transplant patients showed the significance of EBV peak viral load in predicting PTLD development[27]. Quantitative EBV DNA has been reported to correlate with PTLD development. Patients who developed PTLD exhibited significantly higher mean EBV DNA loads (211.6 copies/μL, 56.7-790.1) than those without PTLD (27.3 copies/μL, 18.0-41.2). Furthermore, elevated EBV DNA levels have been reported to be associated with a shorter time to PTLD onset, with a hazard ratio of 2.18 for every log10 increase in EBV viral load[23]. These findings highlight the importance of using EBV viral load to adjust immunosuppressants and prevent PTLD development.

Higher immunosuppression levels are associated with an increased risk of PTLD. Among commonly used agents, elevated tacrolimus exposure has been most consistently linked to PTLD development. In a retrospective pediatric liver transplant cohort, mean tacrolimus levels prior to the onset of EBV DNA were significantly higher in patients who subsequently developed PTLD compared with those who did not[27]. Although the evidence is strongest for tacrolimus, excessive overall immunosuppression - including from other calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites, or lymphocyte-depleting agents - may also contribute to increased PTLD risk.

EBV, also known as human herpesvirus 4, belongs to the human gamma herpesvirus family. This virus usually enters the host through the oropharyngeal route, and local viral replication occurs in the oropharynx. The primary immune mechanisms of the immunocompetent host include a viral-specific antibody response and a viral-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated response via the human leukocyte antigen class I processing pathway.

Once the virus enters the host, it infects local naive B lymphocytes in the tonsillar tissue, stays as dormant infected memory B cells, and exhibits immune tolerance. EBV-infected B lymphocytes express several latent proteins, including virus-coded nuclear antigens, including EBNA (EBNAs 1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, -LP), latent membrane proteins [latent membrane proteins (LMPs) 1 and 2][28], two small non-translated RNAs, and approximately 40 microRNAs[29]. These proteins, which are expressed on EBV-infected B lymphocytes, mimic normal B lymphocyte biology and allow EBV to remain in long-lived memory B cells.

EBV-infected B lymphocytes migrate to germinal centers in common B lymphocyte reservoirs, such as lymph nodes, mucosal lymphoid tissue, and the spleen. EBV then mediates the strict expression of viral proteins, leading to maturation into memory B cells without somatic hypermutation and class switching, as observed in normal activated naïve B lymphocytes. The virus no longer expresses proteins related to cellular proliferation or immunogenic proteins, which protect the virus-hosting B lymphocytes from host immunological responses.

During the carrier state, the virus undergoes recurrent viral reactivation from the B-cell reservoir, resulting in new B-cell infections. The T-cell-mediated immune response controls this process throughout life[30]. Once an event leads to profound T-cell function impairment, EBV activity will be reconstituted, leading to lymphoproliferative disease.

Most PTLDs are strongly associated with EBV infection and exposure to several dose-dependent T-cell immunosuppressive regimens. In this population, pathogenesis is strongly correlated with EBV viral load and exposure to several T-cell immunosuppressive regimens. Impaired EBV-specific immune surveillance is another risk factor for PTLD development. An immune-monitoring study reported an association between cases with high EBV viral load and defective EBV-specific T cells[12].

A previous study using single-cell RNA sequencing showed weakened NK-cell cytotoxicity, dysfunction of CD8+ T cells and Tregs, and impaired B-cell differentiation or activation in patients with EBV-positive PTLD[30,31]. Additionally, dysfunction of transcriptional regulation plays a role in the development of PTLD. A previous study showed that cases with EBV-positive PTLD had lower levels of specific host microRNAs than those without PTLD. These mechanisms may explain why some EBV-infected children do not develop PTLD[32].

MicroRNAs function as post-transcriptional regulators by inhibiting translation or promoting target mRNA degradation, including those involved in cell cycle control, apoptosis, and immune responses. EBV has been hy

EBV LMP1 has been associated with increased miR-146a expression, thereby modulating lymphocyte signaling and proliferation[33]. However, another study of blood samples from 16 pediatric solid organ transplant recipients showed that children who developed EBV-positive PTLD exhibited decreased levels of host microRNAs, including miR-17, miR-19, miR-106a, and miR-194, compared with EBV viremic children who did not develop PTLD[32]. These findings indicate that microRNA-based biomarkers may have the potential for early detection or prognostic prediction of PTLD in EBV-seropositive transplant recipients.

Many recent studies have suggested that de novo lymphoma rather than direct viral persistence-driven disease is the primary distinct pathogenesis in this population. A retrospective multi-center pediatric EBV-negative PTLD study showed that these cases had distinct genetic profiles, including tumor-driven mutations and loss of immune surveillance[34]. Additionally, a multi-modal analytic study identified distinct genomic signatures, including alterations in DNA repair and immune-interaction pathways[35]. The process is gradual with the combination of iatrogenic immunosuppression and chronic antigen stimulation. Therefore, EBV-negative PTLD typically presents as a late-onset disease, up to 7-10 years after transplantation[36].

Early-onset PTLD develops within 1 year after transplantation, whereas late-onset PTLD develops beyond 1 year after transplantation. Adult clinical studies have shown that some parameters, including positive EBV in situ hybridization status, CD20-positive status, and the transplanted organ, are significantly different between the two subtypes. However, the overall response to therapy and overall survival did not differ between the two groups[37].

In pediatric liver transplant recipients, understanding the clinical manifestations of EBV infection is essential because EBV plays a central role in PTLD pathogenesis. EBV-related disease spans a broad spectrum - from primary infection to end-organ involvement (e.g., enteritis, hepatitis) and EBV-associated neoplasms - providing important clinical context for how EBV contributes to the development of PTLD in this high-risk population.

Infectious mononucleosis is the most common clinical presentation of primary EBV infection in the healthy population. It is characterized by fever, pharyngitis, white tonsillar exudate, and lymphadenopathy. Other frequently reported non-specific symptoms include fever lasting 5-6 days, headache, fatigue, eyelid edema, nasal obstruction, and hepatosplenomegaly[38].

The clinical manifestations vary with age. Younger children typically experience milder symptoms such as fever, fatigue, rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, and cervical lymphadenopathy, whereas older children generally present with more pronounced symptoms including tonsillitis, sore throat, nausea, and abdominal pain[38,39]. Elevated liver enzyme levels, particularly alanine aminotransferase, are also more frequently observed in older children[39].

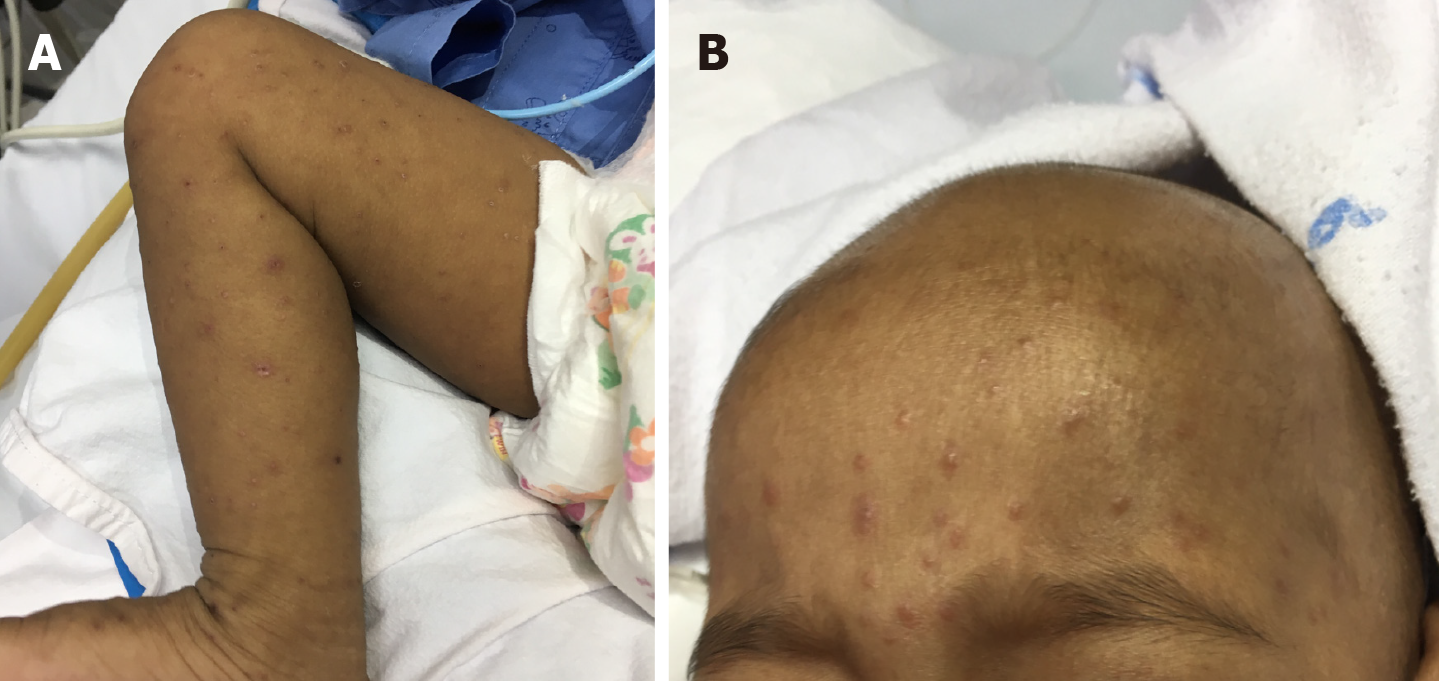

Cutaneous manifestations may occur, with maculopapular rash being the most common; this can be accompanied by a morbilliform eruption and is more frequently observed following amoxicillin exposure. Less common rashes include urticaria, erythema multiforme, acute genital ulceration, and petechiae[40].

In contrast, end-organ EBV disease is more frequently encountered in liver transplant recipients, owing to impaired T-cell function and reduced EBV clearance associated with immunosuppressive therapy. These end-organ manifestations - such as EBV hepatitis, enteritis, pneumonitis, or bone marrow involvement - may progress if unrecognized or if im

Beyond infectious mononucleosis, EBV can also contribute to very rare epithelial malignancies, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, smooth muscle tumors, and gastric carcinoma. Among them, nasopharyngeal carcinoma may be asy

EBV may cause B-cell and non-B-cell lymphomas. B-cell lymphomas include classical Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and other non-Hodgkin lymphomas, whereas non-B-cell lymphomas include peripheral lymphomas of T-cell origin, such as extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. The association with EBV infection has been reported to be higher in the Asian population[42].

Lymphadenopathy is the most common presentation of Hodgkin lymphoma in children, whereas most children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma present with extranodal manifestations. Lymphoblastic lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma are the most common EBV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma often has a higher risk of extranodal involvement than EBV-negative diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[26]. Extranodal sites include the skin, tonsils, stomach, and lungs. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is the most common lymphoma in peripheral T/NK-cell lymphoma in the East Asian population[42].

In contrast to immunocompetent individuals, EBV-associated neoplasms in post-transplant individuals manifest as PTLD. PTLD generally develops in the first year after transplantation or may develop as early as the first weeks of immunosuppression. The median time to onset after solid organ transplantation is approximately 6 months. A large prospective multi-center cohort study of 944 children, including liver recipients, showed that most cases of EBV D+/R- developed PTLD within the first 6 months after transplantation. Additionally, EBV-associated PTLD in D+/R- is associated with monomorphic or polymorphic PTLD[13]. PTLD may occasionally develop beyond a year to a decade or less after transplantation, known as late-onset PTLD.

The clinical manifestations of PTLD are variable, ranging from asymptomatic to heterogeneous, non-specific, and highly variable manifestations, such as fever, malaise, and anorexia[43]. The most benign manifestation is a mononucleosis-like presentation characterized by fever, malaise, and fatigue. Some patients develop B-symptoms, including night sweats, fever, weight loss, and lymphadenopathies.

The disease can range from localized to disseminated, called end-organ diseases. The gastrointestinal tract, allograft liver, lymph nodes, and others, including the central nervous system (CNS), lungs, kidneys, and bone marrow, are the most common organs involved[44,45].

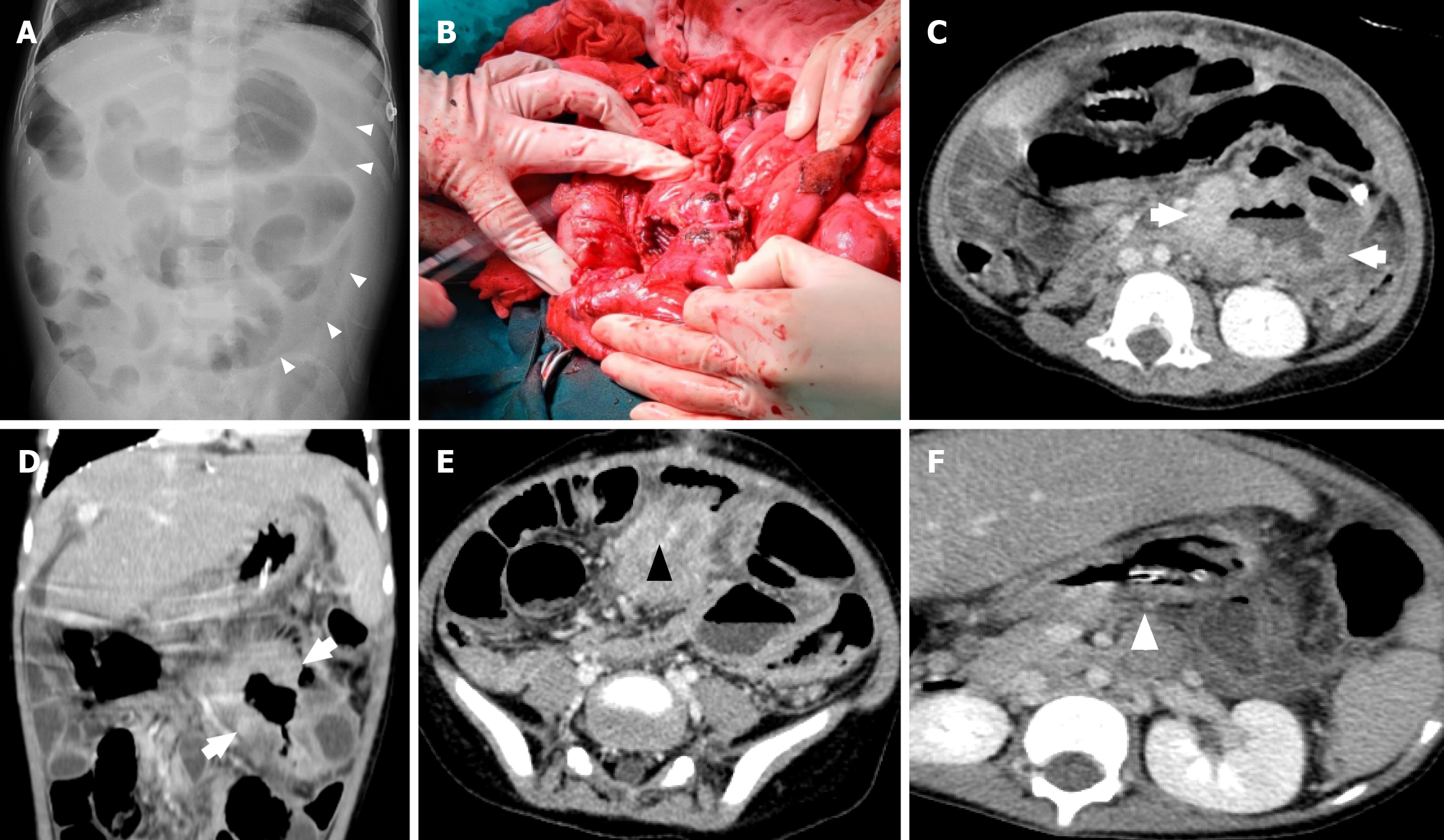

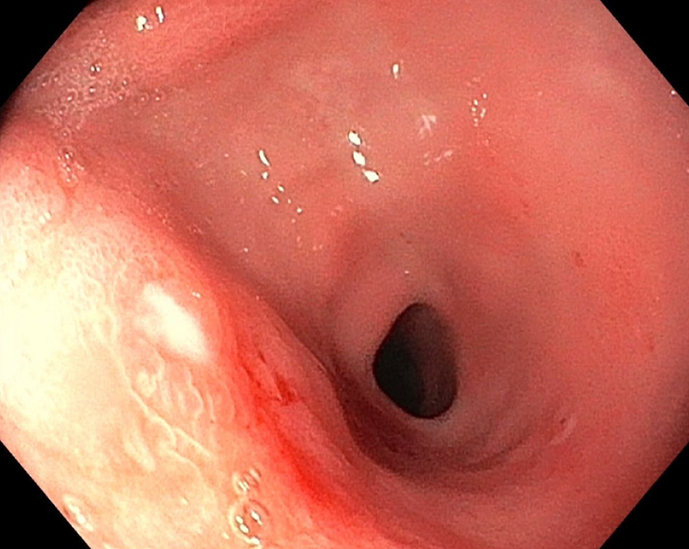

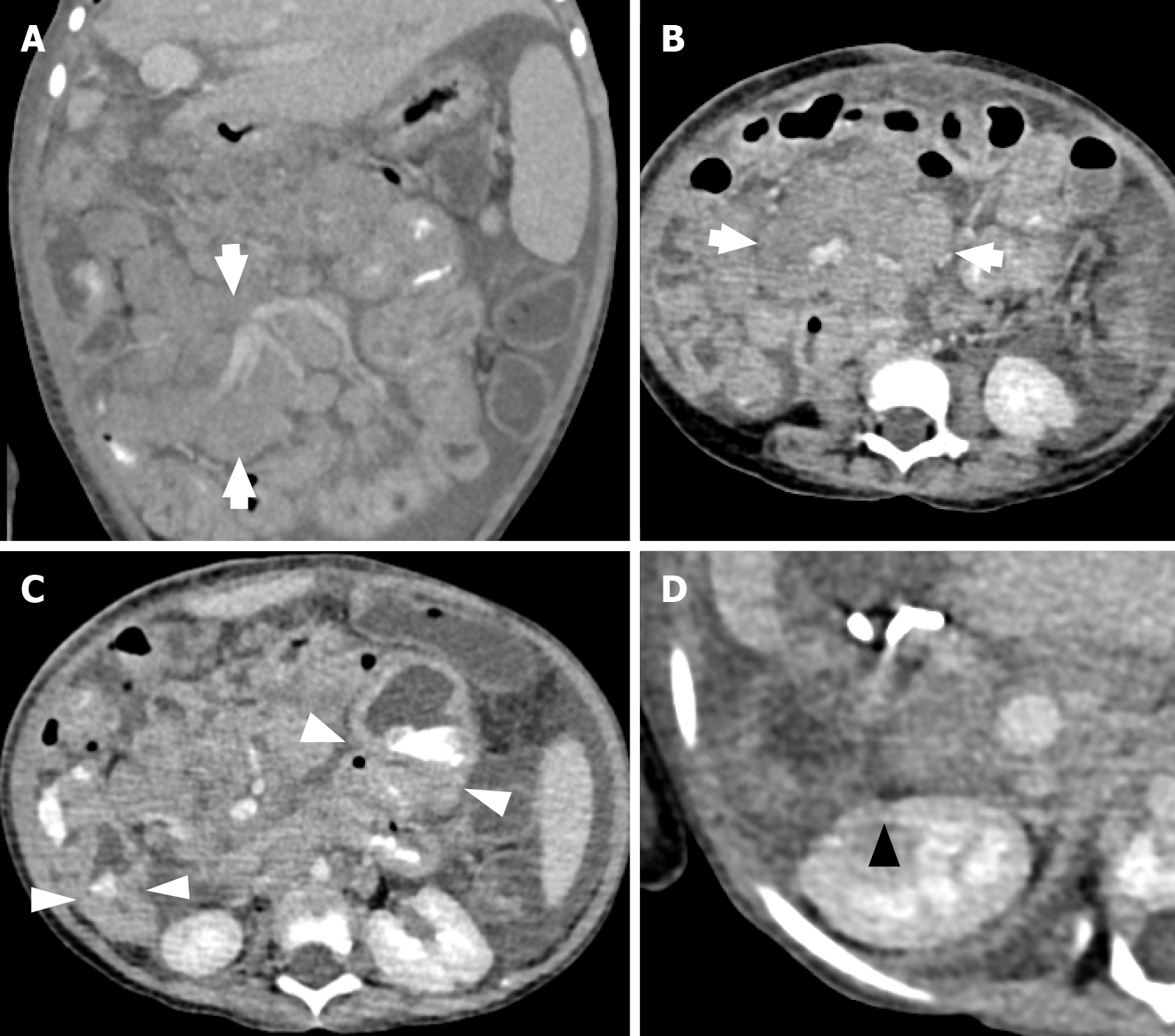

PTLD may present with enlarged lymph nodes or rapidly growing masses in the grafted organ, marrow space, upper airway, skin, and intestine in more severe cases (Figures 1, 2, and3). Therefore, a differential diagnosis of other common complications after transplantation, including rejection reactions of allograft organs and opportunistic infections, is essential. In a more aggressive form, PTLD may show compressive symptoms depending on the disease site. Additionally, CNS involvement of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in PTLD, including primary CNS lymphoma, has been reported[46].

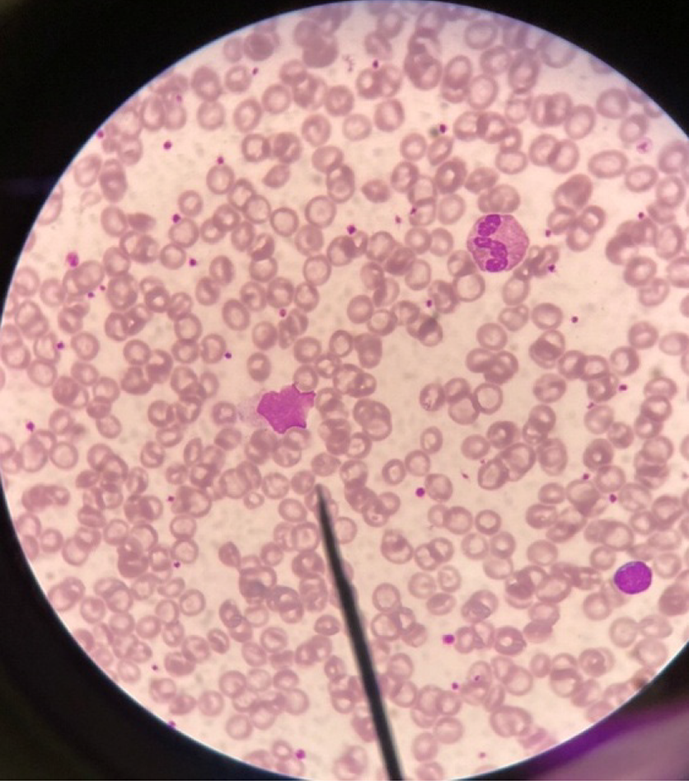

A complete blood count in patients with EBV infection typically shows relative lymphocytosis (lymphocyte count of > 50%) and atypical lymphocytosis (atypical lymphocyte count of > 10%)[47]. Lymphocytosis tends to be more prevalent in younger children, whereas atypical lymphocytosis is primarily observed in older children[38]. Downey cells, reactive atypical lymphocytes, which are typically associated with EBV infectious mononucleosis, can be found. Downey cells have three recognized subtypes: Downey type I, which has a plasmacytoid appearance (round nucleus, basophilic cytoplasm, and resembling plasma cells), Downey type II, which is the classic “ballerina skirt” lymphocyte (eccentric nucleus and abundant basophilic cytoplasm scalloping around red blood cells), and Downey type III, which is characterized by large blast-like cells with open chromatin and prominent nucleoli, mimicking lymphoma (Figure 4).

Liver function tests show elevated aspartate aminotransferase levels, particularly in older children[38]. Other essential investigations to assess disease burden and prognosis include measuring serum lactate dehydrogenase to assess tumor burden and risk of developing tumor lysis syndrome.

Several tests for antibodies against EBV, called heterophile antibodies, are available. A rapid test called Monospot gives a positive result in the first to second week. However, this test has low specificity and can be cross-reactive with other viral infections, such as cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19, human immunodeficiency virus, or leukemia and lymphoma. EBV VCA immunoglobulin and EBNA are commonly used specific EBV antibodies. VCA-IgM is positive for weeks, whereas VCA-IgG remains positive for life. EBNA is positive after 1-6 months[48].

The sensitivity of both heterophile antibodies and specific antibodies is significantly lower in younger children[49]. Infants aged < 1 year may have positive IgG antibodies transferred via the placenta before birth. These antibodies have protective properties against bacterial and viral infections[50].

Tests for EBV DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are available. Plasma, blood, pleural fluid, and spinal fluid can be used. Lumbar puncture with cerebral spinal fluid analysis for EBV PCR is indicated in patients with suspected CNS involvement. Recent prospective studies have standardized quantitative PCR assays for diagnosing proven EBV disease from subclinical infection. However, EBV DNA testing alone cannot replace histopathological diagnosis for PTLD[51].

For prognostic purposes, the peak EBV DNA level and the increase or persistence of DNA are strongly associated with the risk of developing PTLD[27,52]. According to a Chinese study, the threshold of whole-blood EBV DNA for PTLD diagnosis was proposed at 3.755 × 106 copies/mL, with a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 93.4%, and likelihood ratio of 0.27. The optimal threshold remains assay- and center-specific and therefore cannot be universally applied[53].

Because different centers use different PCR platforms, reporting units, and sample types, absolute cutoff values vary significantly across studies. As a result, many transplant programs rely less on a single absolute threshold and instead prioritize trends, such as a rising EBV DNA level from baseline, sustained DNA, or rapid viral load escalation. These dynamic changes are often more clinically meaningful and can serve as cues for intervention.

Accordingly, EBV DNA PCR is widely used for surveillance during the first year after transplantation, especially in high-risk D+/R- recipients. Increasing DNA often guides clinicians to adjust immunosuppressive therapy - including stepwise reduction of calcineurin inhibitors - and makes them consider pre-emptive rituximab, highlighting the role of EBV PCR as a treatment-guiding biomarker[54].

In the post-transplant setting, next-generation sequencing has emerged as an additional prognostic tool. A multicenter prospective observational study demonstrated that gain-of-function mutations in LMP1 were significantly associated with a higher risk of developing EBV-associated PTLD in EBV-seropositive patients[55].

Several radiological studies, including CT (Figures 2 and 5), magnetic resonance imaging, and PET, play an important role in evaluating tumor burden and progression. PET-CT can be used to demonstrate hypermetabolism. A previous case report showed that the corresponding PET-CT findings revealed the tissue morphology of tumor cells, leading to a precise biopsy and diagnosis of PTLD[56]. Additionally, PET-CT is used for the follow-up of treatment response.

Although tissue biopsy is an invasive procedure, it remains the gold standard for diagnosing PTLD and is far superior to relying solely on EBV viral load, which lacks the specificity needed for definitive diagnosis. Histopathological examination allows prompt and accurate PTLD classification - ranging from early lesions to polymorphic or mono

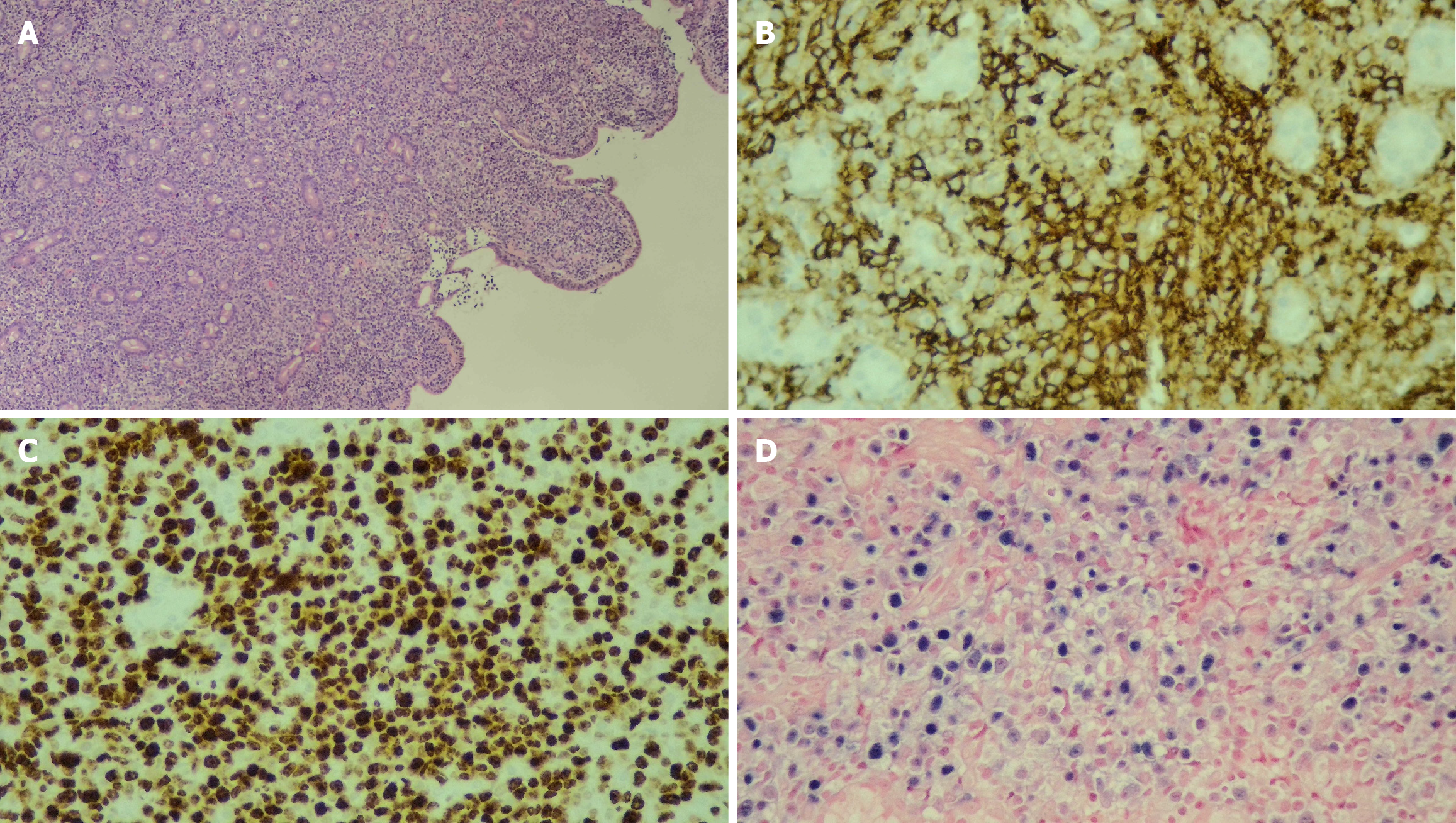

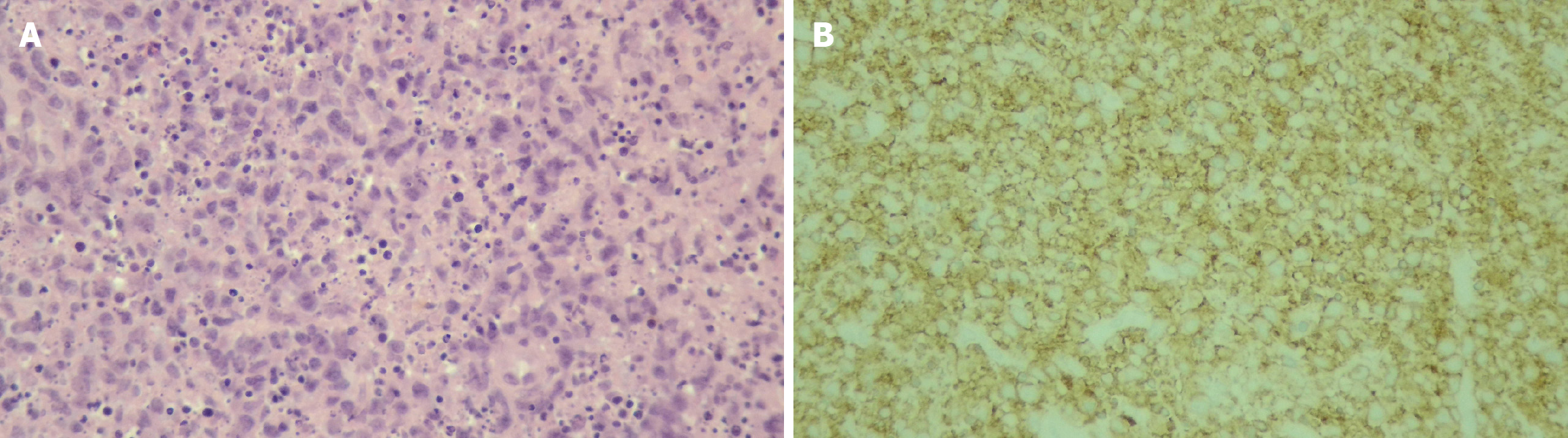

The histopathological features of PTLD typically include areas of necrosis and a polymorphous infiltrate composed of clonal lymphoid cells, such as large transformed lymphocytes, immunoblast-like atypical lymphocytes, and cells with plasmacytoid differentiation[57]. Immunohistochemical stains - including CD20, Ki-67, and Epstein-Barr encoded RNA in situ hybridization - are essential for diagnosis and classification. In particular, CD20 expression guides the use of rituximab in CD20-positive lesions, whereas proliferative indices (Ki-67) and EBV status (Epstein-Barr encoded RNA) further support subtype determination (Figures 6 and 7). Beyond tissue biopsy, cytologic evaluation of body fluids may also reveal atypical lymphoid cells. The presence of such cells is generally associated with a poorer prognosis and may indicate disseminated or more aggressive disease.

Over the past 5 years, several studies have identified novel biomarkers for EBV-associated PTLD by investigating their performance across three key domains: Diagnostic utility, prognostic value, and monitoring during follow-up or after treatment. These biomarkers have been developed based on advances in the understanding of EBV-associated PTLD pathogenesis.

A recent cross-sectional study showed that polyfunctional T cells (D8+, CD107a+, interferon-gamma-positive, interleukin-2 negative, tumor necrosis factor alpha negative) were enriched in EBV-seropositive liver transplant recipients. The level was higher in patients with detectable EBV viral load. This immune biomarker indicates previous exposure and viral load and may be a potential guide during immunosuppressive adjustment[12].

A previous study on post-solid organ transplant children showed a significant decrease in plasma levels of miR-17, miR-19, miR-106a, and miR-194 in EBV-seropositive PTLD compared with EBV-seropositive cases without PTLD. Therefore, these circulating microRNAs may have potential as biomarkers for detecting PTLD[32].

The DNA released from cells into circulation is referred to as cell-free DNA. This DNA may be released from hematopoietic cells in a healthy population. Conversely, patients with cancer, including lymphoma, may have additional DNA released from the cancerous cells[58]. In the PTLD setting, cell-free DNA surveillance may be another promising method for the early detection of cases with PTLD, particularly in EBV-seronegative patients for whom EBV titer surveillance may have little benefit[59].

The goal of PTLD treatment is disease curation and preservation of allograft function. Therefore, PTLD treatment is based on balancing the risks and benefits of eradicating malignancy and treatment-related organ rejection.

The mainstay of PTLD treatment is the reconstitution of the patient’s immune response by reduction of immunosuppression (RIS). In some cases, RIS is combined with an adjunctive monoclonal CD20 antibody. Therapeutic options include rituximab alone or rituximab-based chemotherapy. Other modalities, including surgical excision of the localized lesion, immunotherapy, stem cell transplantation, and radiotherapy, are used when the treatment is unsuccessful.

RIS is the initial management of PTLD. The strategy involves dose reduction of calcineurin inhibitors by at least 50% and the discontinuation of antimetabolic agents, including azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil[60].

Rituximab targets CD20+ B cells, which are a dominant cell type in EBV-positive PTLD. According to the 2024 International Pediatric Transplant Association (IPTA) consensus, rituximab is recommended in the following scenarios[61]: CD20+ B-cell PTLD that does not respond to RIS[62]. Monomorphic PTLD: Rituximab alone is recommended, and rituximab-based chemotherapy is escalated if no response is observed. Early PTLD with a high tumor burden or extranodal diseases: Early rituximab treatment yields a good disease response. High risk of disease progression: D+/R- serostatus, high EBV load, and symptomatic disease: A combination of RIS and rituximab can be used to prevent disease progression.

The major side effects of rituximab are infusion reactions, neutropenia leading to neutropenic infection, and hepatitis B reactivation in individuals with chronic hepatitis B virus. Pre-medication with paracetamol and dexchlorpheniramine should be provided before each rituximab infusion[63].

Chemotherapy is indicated in patients who fail to have an adequate response to both RIS and rituximab therapy. The chemotherapy protocols used are the R-CHOP regimen, which includes rituximab, followed by cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone, and malignant B-cell lymphoma protocols. However, close monitoring of chemotherapy-related adverse events is necessary. Intrathecal chemotherapy, such as high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine, may be indicated in some patients, particularly those with primary CNS lymphoma[62].

Radiotherapy and tomotherapy, which is radiation therapy that combines intensity-modulated radiation therapy with a CT scan, are used as subsequent therapy after chemotherapy, particularly in cases of poor chemotherapy response[56]. Additionally, surgery can be selected for patients with early-stage disease.

Novel treatment strategies, including adaptive immunotherapy, have been developed to treat chemoresistant PTLD. This strategy uses EBV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes to activate the EBV-specific cellular immune response. The clinical use of autologous anti-CD19 CAR-T cells has been studied, and some patients have a satisfactory clinical response[56]. A recent retrospective observational study of 12 pediatric liver transplant recipients with relapsed/refractory post-liver transplant Burkitt lymphoma treated with CAR-T cells showed that most patients achieved complete remission[64].

A child with refractory Burkitt lymphoma-type PTLD after liver transplantation treated with autologous CD19 CAR-T cell achieved remission. This landmark pediatric liver transplantation case establishes the feasibility and antitumor activity in this setting. The first case of post-transplant refractory Burkitt lymphoma was successfully treated with autologous anti-CD19 CAR-T cell therapy with complete remission. However, cytokine release syndrome, which manifests as an inflammatory response characterized by high fever, vomiting, and elevated inflammatory cytokine levels, and acute and chronic graft-vs-host disease were observed but were controllable with tocilizumab and supportive therapy, and glucocorticoids can be used as second-line immunosuppressive therapy[65].

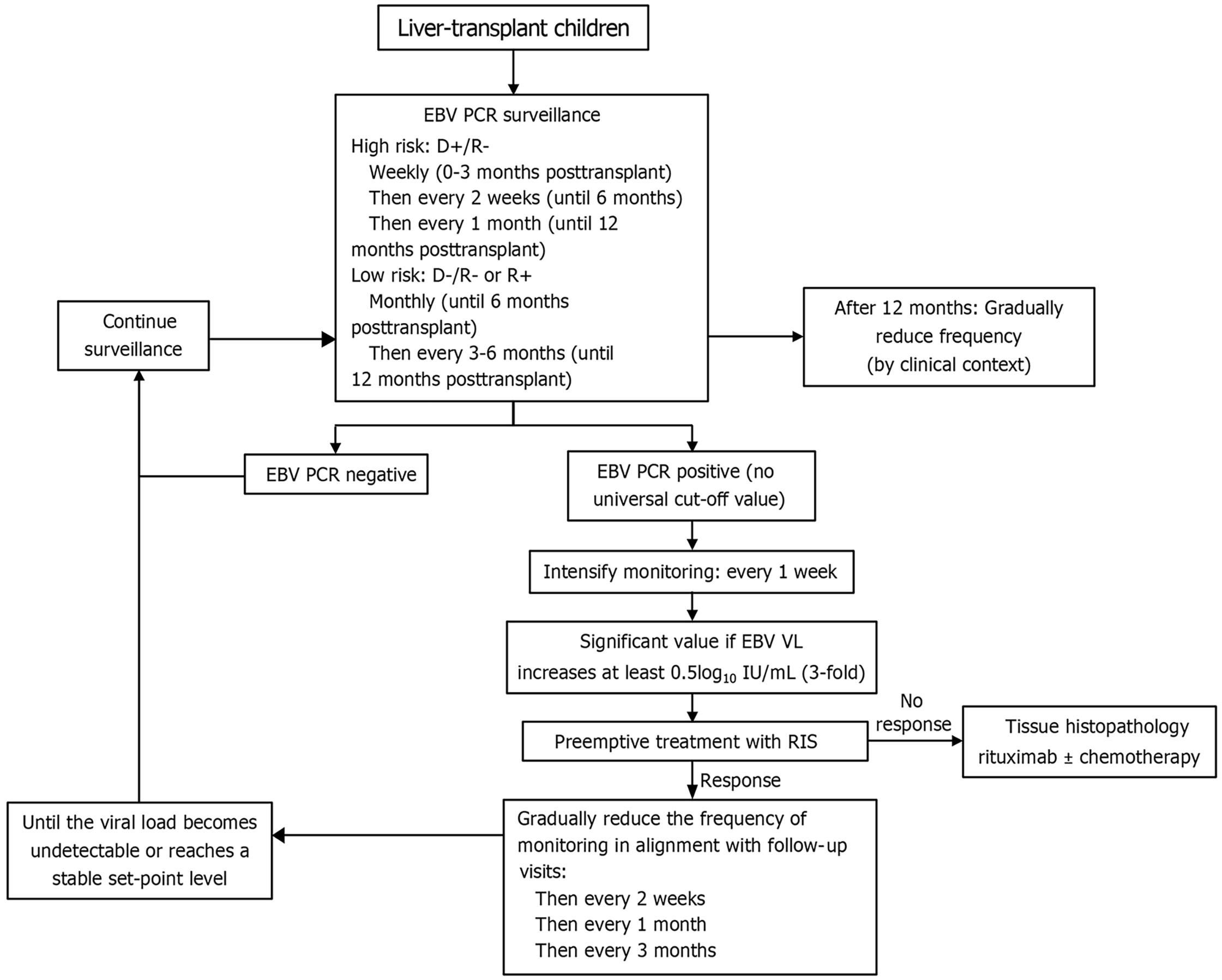

Currently, PCR for EBV viral load is used as a predictor for PTLD and as a biomarker for EBV surveillance after transplantation. According to the IPTA, the proposed surveillance guidelines recommend that high-risk pediatric recipients (D+/R-) and all EBV-naïve children undergoing organ transplants should undergo weekly EBV PCR surveillance in the first 3 months, then every 2-4 weeks until 12 months, and then every 1-3 months until 1 year as the risk decreases. More frequent surveillance is recommended if detectable EBV PCR is present. Monitoring should be performed weekly until the viral load declines after 2-4 weeks and then biweekly, monthly, and every 3 months until the viral load is undetectable[54].

Currently, no universal, definite, and specific EBV DNA cutoff values have been established for guiding decisions on pre-emptive management, immunosuppressive reduction, or pre-emptive rituximab. Reported thresholds vary widely across studies and are highly dependent on the assay platform, specimen type, and laboratory calibration. For example, one clinical trial used an EBV viral load > 4100 copies/mcg peripheral blood mononuclear cells DNA with 80% sensitivity and 79.4% specificity[21], whereas another study applied a cutoff of > 4000 copies/mcg with 100% sensitivity and 83% specificity[66].

Given the variability in EBV PCR assays, a rising EBV DNA trajectory or persistent high-level DNA is often more informative than an absolute cutoff value. Such findings should trigger early immunosuppression reduction and a systematic search for EBV-related organ involvement, beginning with a targeted physical examination for lymphadenopathy, tonsillar enlargement, or hepatosplenomegaly, followed by liver biochemistry (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, bilirubin), synthetic function tests (albumin, international normalized ratio), stool occult blood testing, and chest radiography. This approach facilitates timely detection and management of early EBV disease and may reduce the risk of progression to PTLD. According to IPTA guidelines, EBV DNA should be monitored using the same assay calibrated to the World Health Organization standard expressed as log10 IU/mL. EBV DNA higher than 0.5 log10 IU/mL (3-fold) should be considered significantly different and requires promptly investigation for end-organ diseases and preemptive therapy.

According to the IPTA consensus, vaccination, intravenous immunoglobulin prophylaxis, and antiviral chemoprophylaxis are not recommended for preventing EBV infection or PTLD after transplantation due to a lack of clinical trials proving benefits[61].

The major identified poor prognostic factors include CNS, bone marrow involvement, multi-organ involvement, advanced disease staging (stage IV), early (< 1 year) PTLD, allograft involvement, extranodal site involvement, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels. These major poor prognostic factors contribute to the development of a prognostic scoring system known as the International Prognostic Index, which is derived from five factors, including age, stage, lactate dehydrogenase level, performance status, and number of extranodal sites. Good prognostic factors include late (> 1 year) PTLD, early stage at diagnosis (stages I-II), absence of extranodal involvement, monomorphic form, initial immunosuppression reduction, and rituximab use[67].

The initial site of PTLD is related to all-cause and PTLD-related mortality. Tonsillar and adenoid PTLD have been reported to have the lowest mortality rate regardless of EBV serostatus. Despite the poor prognosis of high-grade histological types, the effect is not significant in the case of tonsillar and adenoid-limited PTLD[68]. Conversely, multi-site PTLD is associated with poor outcomes.

PTLD most commonly develops during the first year after transplantation, with an incidence of 39%-50%, which may be due to the poor immune status during the first month after transplantation. However, PTLD was observed between 4 years and 8 years after transplantation[68,69].

Apart from PTLD, EBV-positive post-transplant recipients may develop other neoplasms. Post-transplant smooth muscle tumors can be found at several sites. The liver is the most common site of involvement, and other sites, including the lungs, larynx, pharynx, gut, spleen, kidneys, brain, and rarely adrenal glands and iris, can be affected[70].

EBV infection remains a major challenge in pediatric liver transplantation, with significant implications for patient survival and graft longevity. Children, particularly those who are EBV-seronegative at transplantation, are at high risk of primary infection and subsequent uncontrolled viral replication under immunosuppression. This not only contributes to morbidity through direct viral disease but also serves as the principal driver of PTLD, the most serious EBV-associated complication in this setting. Early detection through routine EBV viral load monitoring, judicious adjustment of immunosuppressive regimens, extensive investigation for organ involvement and timely pre-emptive or therapeutic interventions are essential strategies for mitigating risks associated with EBV infection (Figure 8). Further studies on predictive biomarkers, individualized immunosuppression protocols, and novel antiviral or immunotherapeutic approaches are needed to improve outcomes in children with liver transplantation.

| 1. | Luskin MR, Heil DS, Tan KS, Choi S, Stadtmauer EA, Schuster SJ, Porter DL, Vonderheide RH, Bagg A, Heitjan DF, Tsai DE, Reshef R. The Impact of EBV Status on Characteristics and Outcomes of Posttransplantation Lymphoproliferative Disorder. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2665-2673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th edition. Lyon: IARC, 2017. |

| 3. | Amengual JE, Pro B. How I treat posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Blood. 2023;142:1426-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cai F, Gao H, Ye Q. Seroprevalence of Epstein-Barr virus infection in children during the COVID-19 pandemic in Zhejiang, China. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1064330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kofahi HM, Swedan SF, Aljezawi M. Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infections among Jordanians: seroprevalence and associated factors. BMC Infect Dis. 2025;25:724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tantipraphat L, Sudhinaraset N, Thongmee T, Kanokudom S, Nilyanimit P, Sudhinaraset N, Poovorawan Y. Epstein-Barr Virus Seroprevalence in Thailand: A Temporal and Global Perspective with Health Care and Economic Correlations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2025;113:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV). May 9, 2024. [cited 31 August 2025]. Available from: from: https://www.cdc.gov/epstein-barr/about/index.html. |

| 8. | Aubry A, Francois C, Demey B, Louchet-Ducoroy M, Pannier C, Segard C, Brochot E, Castelain S. Evolution of Epstein-Barr Virus Infection Seroprevalence in a French University Hospital over 11 Years, Including the COVID-19 Pandemic, 2013-2023. Microorganisms. 2025;13:733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Prtorić L, Šokota A, Karabatić Knezović S, Tešović G, Zidovec-Lepej S. Clinical Features and Laboratory Findings of Hospitalized Children with Infectious Mononucleosis Caused by Epstein-Barr Virus from Croatia. Pathogens. 2025;14:374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yamada M, Fukuda A, Ogura M, Shimizu S, Uchida H, Yanagi Y, Ishikawa Y, Sakamoto S, Kasahara M, Imadome KI. Early Detection of Epstein-Barr Virus as a Risk Factor for Chronic High Epstein-Barr Viral Load Carriage at a Living-donor-dominant Pediatric Liver Transplantation Center. Transplantation. 2023;107:1322-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Belen Apak FB, Işik P, Olcay L, Balci Sezer O, Özçay F, Baskin E, Özdemir BH, Müezzinoğlu C, Karakaya E, Şafak A, Haberal M. Posttransplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder in Pediatric Solid-Organ Transplant Recipients: A 7-Year Single-Center Analysis. Exp Clin Transplant. 2024;22:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cuesta-Martín de la Cámara R, Torices-Pajares A, Miguel-Berenguel L, Reche-Yebra K, Frauca-Remacha E, Hierro-Llanillo L, Muñoz-Bartolo G, Lledín-Barbacho MD, Gutiérrez-Arroyo A, Martínez-Feito A, López-Granados E, Sánchez-Zapardiel E. Epstein-Barr virus-specific T-cell response in pediatric liver transplant recipients: a cross-sectional study by multiparametric flow cytometry. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1479472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tajima T, Martinez OM, Bernstein D, Boyd SD, Gratzinger D, Lum G, Sasaki K, Tan B, Twist CJ, Weinberg K, Armstrong B, Desai DM, Mazariegos GV, Chin C, Fishbein TM, Tekin A, Venick RS, Krams SM, Esquivel CO. Epstein-Barr virus-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders in pediatric transplantation: A prospective multicenter study in the United States. Pediatr Transplant. 2024;28:e14763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hsu CT, Chang MH, Ho MC, Chang HH, Lu MY, Jou ST, Ni YH, Chen HL, Hsu HY, Wu JF. Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric liver recipients in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118:1537-1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barış Z, Özçay F, Yılmaz Özbek Ö, Haberal N, Sarıalioğlu F, Haberal M. A single-center experience of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) cases after pediatric liver transplantation: Incidence, outcomes, and association with food allergy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:354-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yamada M, Chen SF, Green M. Chronic Epstein-Barr viral load carriage after pediatric organ transplantation. Front Pediatr. 2024;12:1335496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Holmes RD, Sokol RJ. Epstein-Barr virus and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. Pediatr Transplant. 2002;6:456-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rock NM, Bouroumeau A, Papangelopoulou D, Mainta I, Katirtzidou E, Dupanloup I, Wildhaber BE, L'Huillier AG, Ansari M, McLin VA, Baleydier F, Rougemont AL. Meeting the Challenges of Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorders After Liver Transplantation in Children: A Proposed Diagnostic and Management Algorithm. Pediatr Transplant. 2025;29:e70060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tajima T, Hata K, Haga H, Nishikori M, Umeda K, Kusakabe J, Miyauchi H, Okamoto T, Ogawa E, Sonoda M, Hiramatsu H, Fujimoto M, Okajima H, Takita J, Takaori-Kondo A, Uemoto S. Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorders After Liver Transplantation: A Retrospective Cohort Study Including 1954 Transplants. Liver Transpl. 2021;27:1165-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Karakoyun M, Önen Ş, Baran M, Çakır M, Ömür Ecevit Ç, Kılıç M, Kantar M, Aksoylar S, Özgenç F, Aydoğdu S. Post-transplant malignancies in pediatric liver transplant recipients: Experience of two centers in Turkey. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chen HS, Ho MC, Hu RH, Wu JF, Chen HL, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Jeng YM, Chang MH. Roles of Epstein-Barr virus viral load monitoring in the prediction of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric liver transplantation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118:1362-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Moghadamnia M, Delroba K, Heidari S, Rezaie Z, Dashti-Khavidaki S. Impact of antiviral prophylaxis on EBV viremia and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in solid organ transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol J. 2025;22:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chang YC, Young RR, Mavis AM, Chambers ET, Kirmani S, Kelly MS, Kalu IC, Smith MJ, Lugo DJ. Epstein-Barr Virus DNAemia and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0269766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Knight JS, Tsodikov A, Cibrik DM, Ross CW, Kaminski MS, Blayney DW. Lymphoma after solid organ transplantation: risk, response to therapy, and survival at a transplantation center. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3354-3362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schubert S, Abdul-Khaliq H, Lehmkuhl HB, Yegitbasi M, Reinke P, Kebelmann-Betzig C, Hauptmann K, Gross-Wieltsch U, Hetzer R, Berger F. Diagnosis and treatment of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric heart transplant patients. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:54-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shannon-Lowe C, Rickinson AB, Bell AI. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017;372:20160271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 34.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Dogan B, Sema YA, Bora K, Veysel U, Benan D, Ezgi KT, Gozde AK, Demir D, Ozsan N, Hekimgil M, Zumrut SB, Miray K, Funda C, Sema A. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder associated Epstein-Barr virus DNAemia after liver transplantation in children: Experience from single center. J Med Virol. 2024;96:e29767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rickinson AB, Moss DJ. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:405-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 582] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Babcock GJ, Hochberg D, Thorley-Lawson AD. The expression pattern of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in vivo is dependent upon the differentiation stage of the infected B cell. Immunity. 2000;13:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 30. | Hislop AD, Taylor GS, Sauce D, Rickinson AB. Cellular responses to viral infection in humans: lessons from Epstein-Barr virus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:587-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 611] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wen Y, Chen C, Zhou T, Liu C, Zhang Z, Gu G. Single-cell analysis unveils immune dysregulation and EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Hum Immunol. 2025;86:111309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sen A, Enriquez J, Rao M, Glass M, Balachandran Y, Syed S, Twist CJ, Weinberg K, Boyd SD, Bernstein D, Trickey AW, Gratzinger D, Tan B, Lapasaran MG, Robien MA, Brown M, Armstrong B, Desai D, Mazariegos G, Chin C, Fishbein TM, Venick RS, Tekin A, Zimmermann H, Trappe RU, Anagnostopoulos I, Esquivel CO, Martinez OM, Krams SM. Host microRNAs are decreased in pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients during EBV+ Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder. Front Immunol. 2022;13:994552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cameron JE, Yin Q, Fewell C, Lacey M, McBride J, Wang X, Lin Z, Schaefer BC, Flemington EK. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces cellular MicroRNA miR-146a, a modulator of lymphocyte signaling pathways. J Virol. 2008;82:1946-1958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Afify ZAM, Taj MM, Orjuela-Grimm M, Srivatsa K, Miller TP, Edington HJ, Dalal M, Robles J, Ford JB, Ehrhardt MJ, Ureda TJ, Rubinstein JD, McCormack S, Rivers JM, Chisholm KM, Kavanaugh MK, Bukowinski AJ, Friehling ED, Ford MC, Reddy SN, Marks LJ, Smith CM, Mason CC. Multicenter study of pediatric Epstein-Barr virus-negative monomorphic post solid organ transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Cancer. 2023;129:780-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Toh J, Reitsma AJ, Tajima T, Younes SF, Ezeiruaku C, Jenkins KC, Peña JK, Zhao S, Wang X, Lee EYZ, Glass MC, Kalesinskas L, Ganesan A, Liang I, Pai JA, Harden JT, Vallania F, Vizcarra EA, Bhagat G, Craig FE, Swerdlow SH, Morscio J, Dierickx D, Tousseyn T, Satpathy AT, Krams SM, Natkunam Y, Khatri P, Martinez OM. Multi-modal analysis reveals tumor and immune features distinguishing EBV-positive and EBV-negative post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5:101851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fulchiero R, Amaral S. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease after pediatric kidney transplant. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:1087864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ghobrial IM, Habermann TM, Macon WR, Ristow KM, Larson TS, Walker RC, Ansell SM, Gores GJ, Stegall MD, McGregor CG. Differences between early and late posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in solid organ transplant patients: are they two different diseases? Transplantation. 2005;79:244-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Wu Y, Ma S, Zhang L, Zu D, Gu F, Ding X, Zhang L. Clinical manifestations and laboratory results of 61 children with infectious mononucleosis. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520924550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Topp SK, Rosenfeldt V, Vestergaard H, Christiansen CB, Von Linstow ML. Clinical characteristics and laboratory findings in Danish children hospitalized with primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. Infect Dis (Lond). 2015;47:908-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Di Lernia V, Mansouri Y. Epstein-Barr virus and skin manifestations in childhood. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1177-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Villela VA, Morales-León JF, Cavigli A, Palacios E. Pediatric EBV+ Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma With Complete ICA Occlusion. Ear Nose Throat J. 2022;101:228-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Qin C, Huang Y, Feng Y, Li M, Guo N, Rao H. Clinicopathological features and EBV infection status of lymphoma in children and adolescents in South China: a retrospective study of 662 cases. Diagn Pathol. 2018;13:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Taylor AL, Marcus R, Bradley JA. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) after solid organ transplantation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;56:155-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Younes BS, Ament ME, McDiarmid SV, Martin MG, Vargas JH. The involvement of the gastrointestinal tract in posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric liver transplantation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:380-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Molmenti EP, Nagata DE, Roden JS, Squires RH, Molmenti H, Fasola CG, Winick N, Tomlinson G, Lopez MJ, D'Amico L, Dyer HL, Savino AC, Sanchez EQ, Levy MF, Goldstein RM, Andersen JA, Klintmalm GB. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative syndrome in the pediatric liver transplant population. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:356-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Gandhi MK, Hoang T, Law SC, Brosda S, O'Rourke K, Tobin JWD, Vari F, Murigneux V, Fink L, Gunawardana J, Gould C, Oey H, Bednarska K, Delecluse S, Trappe RU, Merida de Long L, Sabdia MB, Bhagat G, Hapgood G, Blyth E, Clancy L, Wight J, Hawkes E, Rimsza LM, Maguire A, Bojarczuk K, Chapuy B, Keane C. EBV-associated primary CNS lymphoma occurring after immunosuppression is a distinct immunobiological entity. Blood. 2021;137:1468-1477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Gao LW, Xie ZD, Liu YY, Wang Y, Shen KL. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of infectious mononucleosis associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection in children in Beijing, China. World J Pediatr. 2011;7:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Vogler K, Schmidt LS. [Clinical manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus infection in children and adolescents]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2018;180:V09170644. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Horwitz CA, Henle W, Henle G, Polesky H, Balfour HH Jr, Siem RA, Borken S, Ward PC. Heterophil-negative infectious mononucleosis and mononucleosis-like illnesses. Laboratory confirmation of 43 cases. Am J Med. 1977;63:947-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Niewiesk S. Maternal antibodies: clinical significance, mechanism of interference with immune responses, and possible vaccination strategies. Front Immunol. 2014;5:446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Ludvigsen LUP, Andersen AS, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Jensen-Fangel S, Bøttger P, Handberg KJ, Ivarsen P, d'Amore F, Bibby BM, Albertsen BK, Jespersen B, Thomsen MK. A prospective evaluation of the diagnostic potential of EBV-DNA in plasma and whole blood. J Clin Virol. 2023;167:105579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ratiu C, Dufresne SF, Thiant S, Roy J. Epstein-Barr Virus Monitoring after an Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant: Review of the Recent Data and Current Practices in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2024;31:2780-2795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Jia L, Yang H, Zhou Y, Meng Y, Zhang L, Lei X, Guan X, Yu J, Dou Y. Analysis of risk factors for Epstein-Barr virus reactivation and progression to post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Pediatr. 2025;13:1627990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Preiksaitis J, Allen U, Bollard CM, Dharnidharka VR, Dulek DE, Green M, Martinez OM, Metes DM, Michaels MG, Smets F, Chinnock RE, Comoli P, Danziger-Isakov L, Dipchand AI, Esquivel CO, Ferry JA, Gross TG, Hayashi RJ, Höcker B, L'Huillier AG, Marks SD, Mazariegos GV, Squires J, Swerdlow SH, Trappe RU, Visner G, Webber SA, Wilkinson JD, Maecker-Kolhoff B. The IPTA Nashville Consensus Conference on Post-Transplant lymphoproliferative disorders after solid organ transplantation in children: III - Consensus guidelines for Epstein-Barr virus load and other biomarker monitoring. Pediatr Transplant. 2024;28:e14471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Martinez OM, Krams SM, Robien MA, Lapasaran MG, Arvedson MP, Reitsma A, Balachandran Y, Harris-Arnold A, Weinberg K, Boyd SD, Armstrong B, Trickey A, Twist CJ, Gratzinger D, Tan B, Brown M, Chin C, Desai DM, Fishbein TM, Mazariegos GV, Tekin A, Venick RS, Bernstein D, Esquivel CO. Mutations in latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus are associated with increased risk of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in children. Am J Transplant. 2023;23:611-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Wang T, Feng M, Luo C, Wan X, Pan C, Tang J, Xue F, Yin M, Lu D, Xia Q, Li B, Chen J. Successful Treatment of Pediatric Refractory Burkitt Lymphoma PTLD after Liver Transplantation using Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. Cell Transplant. 2021;30:963689721996649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Dusenbery D, Nalesnik MA, Locker J, Swerdlow SH. Cytologic features of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:489-496. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 58. | Heitzer E, Auinger L, Speicher MR. Cell-Free DNA and Apoptosis: How Dead Cells Inform About the Living. Trends Mol Med. 2020;26:519-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Schroers-Martin JG, Garofalo A, Shi SY, Soo J, Luikart H, Sworder BJ, Boegeholz J, Kang XM, Olsen M, Liu CL, Tian F, Skoda A, Gamino G, Morales DJ, Freystaetter K, Agbor-Enoh S, Andreas M, Chambers D, Crespo-Leiro M, Dhillon G, Farr M, Hollander S, Kfoury A, Kransdorf E, Nijland M, Raikhelkar J, Rosenthal D, Ross H, Verleden S, Zaffiri L, Zuckermann A, Kurtz D, Natkunam Y, Diehn M, Khush K, Alizadeh AA. Non-Invasive Characterization and Early Detection of Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorders. Blood. 2024;144 Suppl 1:648. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 60. | Samant H, Vaitla P, Kothadia JP. Posttransplant Lymphoproliferative Disorders. 2023 Jul 10. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Green M, Squires JE, Chinnock RE, Comoli P, Danziger-Isakov L, Dulek DE, Esquivel CO, Höcker B, L'Huillier AG, Mazariegos GV, Visner GA, Bollard CM, Dipchand AI, Ferry JA, Gross TG, Hayashi R, Maecker-Kolhoff B, Marks S, Martinez OM, Metes DM, Michaels MG, Preiksaitis J, Smets F, Swerdlow SH, Trappe RU, Wilkinson JD, Allen U, Webber SA, Dharnidharka VR. The IPTA Nashville consensus conference on Post-Transplant lymphoproliferative disorders after solid organ transplantation in children: II-consensus guidelines for prevention. Pediatr Transplant. 2024;28:e14350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Jagadeesh D, Woda BA, Draper J, Evens AM. Post transplant lymphoproliferative disorders: risk, classification, and therapeutic recommendations. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13:122-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Choquet S, Leblond V, Herbrecht R, Socié G, Stoppa AM, Vandenberghe P, Fischer A, Morschhauser F, Salles G, Feremans W, Vilmer E, Peraldi MN, Lang P, Lebranchu Y, Oksenhendler E, Garnier JL, Lamy T, Jaccard A, Ferrant A, Offner F, Hermine O, Moreau A, Fafi-Kremer S, Morand P, Chatenoud L, Berriot-Varoqueaux N, Bergougnoux L, Milpied N. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in B-cell post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: results of a prospective multicenter phase 2 study. Blood. 2006;107:3053-3057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Chen T, Zheng W, Wang R, Dong C, Sun C, Wang K, Han C, Wei X, Gao W. Post-Liver Transplantation-Burkitt Lymphoma in Children: A Single-Center Study of Clinical Characteristics, Treatment, and Outcomes. Pediatr Transplant. 2025;29:e70027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Portuguese AJ, Gauthier J, Tykodi SS, Hall ET, Hirayama AV, Yeung CCS, Blosser CD. CD19 CAR-T therapy in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and systematic review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2023;58:353-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Lee TC, Savoldo B, Rooney CM, Heslop HE, Gee AP, Caldwell Y, Barshes NR, Scott JD, Bristow LJ, O'Mahony CA, Goss JA. Quantitative EBV viral loads and immunosuppression alterations can decrease PTLD incidence in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2222-2228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Oton AB, Wang H, Leleu X, Melhem MF, George D, Lacasce A, Foon K, Ghobrial IM. Clinical and pathological prognostic markers for survival in adult patients with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders in solid transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:1738-1744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | L'Huillier AG, Dipchand AI, Ng VL, Hebert D, Avitzur Y, Solomon M, Ngan BY, Stephens D, Punnett AS, Barton M, Allen UD. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric patients: Survival rates according to primary sites of occurrence and a proposed clinical categorization. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2764-2774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Quinlan SC, Pfeiffer RM, Morton LM, Engels EA. Risk factors for early-onset and late-onset post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in kidney recipients in the United States. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:206-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Jossen J, Chu J, Hotchkiss H, Wistinghausen B, Iyer K, Magid M, Kamath A, Roayaie S, Arnon R. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors in children following solid organ transplantation: a review. Pediatr Transplant. 2015;19:235-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/