Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113685

Revised: October 22, 2025

Accepted: December 24, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 165 Days and 0.5 Hours

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a rare, nonsuppurative cholestatic disease that affects the small intrahepatic bile ducts. If not adequately managed, it may pro

To compare leptin and adiponectin levels in PBC patients stratified by the pre

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving 81 PBC patients diagnosed according to European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines, all fol

Patients with PBC/MASLD had significantly lower adiponectin levels (1698.24 pg/mL vs 2042.08 pg/mL, P = 0.015) and higher leptin levels (1.89 ng/mL vs 0.62 ng/mL, P < 0.001) compared with those without MASLD. The leptin-to-adiponectin (L/A) ratio was also significantly elevated (1.63 vs 0.27, P < 0.001). Similar patterns were observed in patients with MetS: Adiponectin (1208.41 pg/mL vs 2086.10 pg/mL, P = 0.002), leptin (1.51 ng/mL vs 0.79 ng/mL, P = 0.002), and L/A ratio (1.28 vs 0.41, P = 0.009). By contrast, no significant differences in adipokine levels were observed between patients with and without advanced fibrosis or complete biochemical response (all P > 0.05).

Adipokines reflect metabolic status in PBC. The L/A ratio is promising biomarker for MASLD. No significant association between leptin and adiponectin levels and advanced fibrosis was detected within the limited sample size of this study.

Core Tip: Our results show that primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease or metabolic syndrome as comorbidities exhibit significantly lower adiponectin levels, higher leptin levels, and an elevated leptin-to-adiponectin ratio within the limited sample size of this study. Thus, adipokines may serve as potential biomarkers for identifying metabolic conditions in PBC. By contrast, no significant associations were observed between adipokine levels and fibrosis severity or biochemical response. Our findings indicate that adipokines, particularly leptin-to-adiponectin ratio may become a promising biomarker for identifying metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in PBC patients.

- Citation: Koky T, Drazilova S, Komarova S, Macej M, Toporcerova D, Janicko M, Spakova I, Rabajdova M, Marekova M, Jarcuska P. Adipokine profiles reflect metabolic dysfunction but not fibrosis in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 113685

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/113685.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113685

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a chronic non-suppurative autoimmune liver disease involving destruction of the small bile ducts. For the PBC diagnosis, two out of three of the following criteria must be met: Increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) above the upper limit of the norm lasting for at least 6 months, anti-mitochondrial antibody M2 positivity in a titer of at least 1:40; in case of anti-mitochondrial antibody negativity, specific anti-nuclear antibody positivity (anti-sp100 or anti-gp210), histological findings consistent with PBC[1]. PBC mainly affects women, with higher prevalence in developed countries, while the incidence remains relatively stable[2]. PBC commonly affects middle-aged individuals, with a marked predominance in women. A long-standing female-to-male ratio of 9:1 has been reported. The female predominance of PBC remains unexplained to date, but a significant contribution of sex-related epigenetic modifications has been proposed[3]. PBC meets the criteria to be classified as a rare disease[4]. PBC may progress to liver cirrhosis; the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with PBC is rare[5]. The goals of PBC treatment are to achieve a biochemical response, stabilize or improve histological findings, improve quality of life, and prevent disease progression. The drug of choice for PBC is ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). The optimal biochemical response is the normalization of bilirubin and ALP levels on UDCA treatment, but only some patients achieve this result[6]. Second-line treatment for PBC should be considered in UDCA non-responders. Seladelpar and elafibranor are currently only drugs approved for second-line treatment of PBC[7].

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, is defined as hepatic steatosis occurring in the presence of one or more cardiometabolic risk factors and in the absence of significant alcohol intake. The MASLD spectrum includes simple steatosis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma[8].

MASLD is defined as the presence of hepatic steatosis, identified by imaging or liver biopsy, in combination with at least one of the following metabolic risk factors: (1) Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 or waist circumference > 94 cm in men and > 80 cm in women in Western population; (2) Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL (≥ 5.60 mmol/L), or 2-hour plasma glucose after oral glucose load ≥ 140 mg/dL (≥ 7.80 mmol/L), or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 5.7%, or current use of antidiabetic therapy; (3) Blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or current use of antihypertensive therapy; (4) Plasma triglycerides (TG) ≥ 150 mg/dL (≥ 1.70 mmol/L) or current use of lipid-lowering therapy; or (5) Plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) < 40 mg/dL (< 1.00 mmol/L) in men and < 50 mg/dL (< 1.3 mmol/L) in women or current use of lipid-modifying therapy[8].

Adipose tissue is a complex organ composed of mature adipocytes, preadipocytes, immune cells, sympathetic nerve fibers, and endothelial cells, each contributing to physiological and pathological processes throughout the body. Tr

One of the most significant milestones in obesity research was the recognition of adipose tissue as an active endocrine organ. Adipocytes secrete various protein hormones and signaling molecules, collectively referred to as adipokines, which mediate complex inter-organ communication with the liver, skeletal muscle, and other tissues. Changes in the composition of these protein signatures play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of metabolic diseases. Some adipokines act as inflammatory mediators that promote the development of insulin resistance in adipose tissue, while others have direct effect on enhancing insulin sensitivity. For instance, adiponectin has been linked to enhanced insulin sensitivity in experimental models. Among the body’s fat reservoirs, visceral adipose tissue is considered the main contributor to metabolic disturbances in obesity, which may be due to differences in adipokine secretion between various fat depots. Although some adipokines are predominantly produced by adipocytes themselves, the stromal vascular fraction also plays a significant role in the endocrine and paracrine functions of white adipose tissue[10].

Adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin play a central role in the metabolic-inflammatory cross-talk that drives steatosis and fibrogenesis in MASLD. Circulating leptin levels are typically elevated in MASLD and correlate positively with hepatic fibrosis, independently of BMI, supporting a pro-fibrogenic role of leptin in hepatic stellate cell activation[11]. Conversely, adiponectin is decreased across the non-alcoholic fatty liver → nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) spectrum, showing anti-steatotic and anti-fibrotic actions through stimulation of fatty acid oxidation and suppression of stellate cell proliferation. In biopsy-proven cohorts, leptin discriminated non-alcoholic fatty liver disease from controls [area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC): 0.83-0.88], while low adiponectin and insulin-like growth factor-1 levels were associated with advanced fibrosis[11]. Similarly, recent reviews confirm that leptin excess promotes inflammation and fibrosis, whereas adiponectin decline parallels disease progression in MASLD[12]. In contrast, PBC shows a distinct adipokine pattern. PBC patients have significantly higher serum adiponectin and leptin compared with both NASH patients and healthy controls, with adiponectin levels correlating positively with histological stage and inversely with BMI. These findings suggest that hyperadiponectinemia in PBC reflects cholestatic injury rather than metabolic dysfunction and may contribute to the paradoxically low atherosclerotic risk observed in this disease[13].

However, despite extensive evidence regarding adipokines in MASLD and in PBC individually, no published studies to date have systematically evaluated leptin, adiponectin, or the leptin-to-adiponectin (L/A) ratio in patients with overlapping PBC and MASLD. The current study therefore addresses this gap by assessing adipokine profiles and their relationship to metabolic and fibrotic parameters in a well-characterized PBC cohort.

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PBC using European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) criteria treated at a single tertiary hepatology center: The Hepatology Outpatient Clinic, 2nd Department of Internal Medicine, Pavol Jozef Safarik University, Faculty of Medicine, and Louis Pasteur University Hospital (UNLP), Košice. Patients were prospectively consecutively enrolled from January 2024 to June 2024. Inclusion criteria were based on the diagnostic guidelines of the EASL[1]. Eligible patients were scheduled for follow-up visits during which laboratory tests, transient elastography, demographic and anthropometric assessments, disease-specific questionnaires, and imaging investigations were performed.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Louis Pasteur University Hospital in Košice on October 26, 2020 (approval No. 2020/EK/10076). Its implementation was delayed due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. All participants provided written informed consent. We hypothesized that patients with PBC and concurrent MASLD or metabolic syndrome (MetS) would exhibit a distinct adipokine profile, characterized by lower adiponectin and higher leptin levels compared with those without these comorbidities.

Serum adiponectin and leptin concentrations were measured using commercially available enzyme-linked im

The diagnosis of MetS was established according to the criteria of the International Diabetes Federation (2005), summarized in Table 1[14]. The cut-off values for steatosis grades S1-S3 in MASLD were determined according to the EASL-European Association for the Study of Diabetes-European Association for the Study of Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of MASLD. Hepatic steatosis was diagnosed using a controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) threshold of 248 dB/m, with CAP values ≥ 248 dB/m, 268 dB/m, and 280 dB/m corresponding to steatosis grades S1, S2, and S3, respectively. The diagnosis of MASLD was based on the EASL guidelines. The term PBC/MASLD in this study refers specifically to patients with PBC who also met the diagnostic criteria for MASLD, as defined by the EASL-European Association for the Study of Diabetes-European Association for the Study of Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines[8]. Thus, all patients included in this subgroup had an established diagnosis of PBC, with concomitant MASLD identified based on the presence of hepatic steatosis (CAP ≥ 248 dB/m) and metabolic risk factors. Liver fibrosis was assessed by vibration-controlled transient elastography; stiffness values < 10.7 kPa indicated mild to moderate fibrosis (F0-F2), while values ≥ 10.7 kPa indicated advanced fibrosis (F3-F4)[15,16]. Elastographic examinations were performed by an experienced physician. Complete biochemical response (CBR) was defined as normalization of total bilirubin and ALP at the last follow-up.

| Component | Diagnostic criterion |

| Central obesity (mandatory) | Waist circumference above the ethnicity-specific threshold1 |

| Plus at least two of the following | |

| Elevated TG | ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.70 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality |

| Reduced HDL-C | < 40 mg/dL (< 1.03 mmol/L) in men; < 50 mg/dL (< 1.29 mmol/L) in women, or specific treatment |

| Elevated blood pressure | Systolic ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic ≥ 85 mmHg, or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension |

| Elevated fasting glucose | ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.60 mmol/L) or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes |

Statistical analyses were performed to compare adipokine levels and other clinical or biochemical parameters across subgroups of PBC patients stratified by the presence of MASLD, MetS, advanced fibrosis, or CBR. Because there was very limited data published about the levels of leptin or adiponectin in PBC with MASLD or MetS no sample size calculations could be performed and all available patients were included. In this regard we consider the study to be exploratory. If we consider published difference in adiponectin levels between PBC patients with no NASH and NASH patients with no PBC[7], the delta mean between two groups was 4552 ng/mL with SD of 7005, thus, with the preferred alpha of 0.05 and beta 0.20 the expected sample to prove independence was ex post calculated to be 37 per group. Data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and non-normally distributed variables as median (before log transformation) with interquartile range. Variables with substantial skewness or kurtosis [e.g., leptin, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), ghrelin] were log-transformed before parametric testing. For group comparisons, the independent t-test was applied to normally distributed variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test to non-normally distributed variables. The L/A ratio was analyzed after unit conversion and logarithmic transformation of both markers, followed by the independent t-test. To evaluate associations between the L/A ratio and MASLD, MetS, or advanced fibrosis, multivariate binary logistic regression models were applied, with the log-transformed L/A ratio as the primary predictor. Models were adjusted for BMI (for MASLD and MetS) and for age, BMI, and CBR (for fibrosis). Discriminative ability of the L/A ratio was further assessed using ROC curves and corresponding area under the curve (AUC) values. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We assessed differences in leptin and adiponectin levels between groups defined by the presence of MASLD, MetS, CBR, and advanced fibrosis. Given the multiple comparisons, results should be interpreted cautiously. No adjustment was made because the study was exploratory, as stated above. All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 27.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States).

A total of 81 patients with PBC were included in the analysis. Of these, 3 (3.70%) were men and 78 (96.30%) women. The mean age of the cohort was 64.28 ± 10.23 years, 7 of 81 patients (8.60%) were receiving antidiabetic medication and 18 of 81 (22.20%) were on statin therapy, while none of the patients were treated with hormone replacement therapy. Criteria for MASLD were met in 39 patients (48.20%), and MetS was present in 33 (40.70%). The mean BMI was 26.54 ± 5.11 kg/m2, and mean waist circumference was 89.45 ± 13.13 cm. Advanced fibrosis was detected in 19 patients (23.50%), and CBR was achieved in 44 patients (55%). Patients were stratified into four comparison groups: A: PBC with and without coexisting MASLD; B: PBC with and without MetS; C: PBC with and without advanced fibrosis; D: PBC with and without CBR subgroups characteristics are presented in Table 2.

| Characteristic | n = 81 |

| Age (years) | 64.28 ± 10.23 (43-88) |

| BMI | 26.54 ± 5.11 (17.81-39.10) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 89.45 ± 13.13 (60.00-121.00) |

| Gender | Female 78 (96.30); male 3 (3.70) |

| Coronary artery disease | 2 (2.50) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 2 (2.50) |

| History of stroke | 4 (5) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1 (1.30) |

| Complete biochemical response | 44 (55) |

| Advanced liver fibrosis F3/F4 | 19 (23.50) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 33 (40.74) |

| MASLD | 39 (48.15) |

| AST (% of ULN) | 93.51 ± 39.90 (45.00-215.00) |

| ALT (% of ULN) | 85.03 ± 60.44 (25.00-350.00) |

| GGT (% of ULN) | 186.39 ± 217.55 (34.92-1506.35) |

| ALP (% of ULN) | 102.52 ± 54.40 (38.50-326.50) |

| Bil-T (μmol/L) | 12.91 ± 6.08 (5.60-39.70) |

| Bil-C (μmol/L) | 2.84 ± 2.01 (1.15-14.60) |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.57 ± 1.37 (4.10-12.40) |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 2.08 ± 1.2 (0.09-7.36) |

| HOMA-IR | 5.51 ± 2.64 (2.40-16.32) |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.49 ± 1.21 (3.33-9.12) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.71 ± 0.40 (0.84-2.79) |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.40 ± 0.90 (1.87-5.75) |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.38 ± 1.24 (0.47-9.20) |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 247.48 ± 79.73 (44-489.00) |

| Adiponectin (pg/mL) | 2668.94 ± 2615.75 (367.15-12457.60) |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 1.99 ± 3.16 (0.23-21.97) |

| CAP (dB/m) | 236.83 ± 59.09 (108.00-400.00) |

| Liver stiffness (TE, kPa) | 8.16 ± 5.35 (2.60-32.60) |

| L/A ratio | 2.05 ± 4.59 (0.02-28.56) |

Among the 81 PBC patients, 39 (48.20%) were classified as having coexisting MASLD, while 42 (51.90%) did not meet the MASLD criteria. Comparative analysis revealed significant differences, particularly in anthropometric, metabolic, and adipokine parameters. Patients with MASLD had significantly higher BMI (30.40 ± 4.00 kg/m2vs 23.50 ± 3.80 kg/m2, P < 0.001) and waist circumference (99.10 ± 10.30 cm vs 81.40 ± 9.10 cm, P < 0.001). Adiponectin levels were significantly lower in patients with MASLD (median 1698.24 pg/mL vs 2042.08 pg/mL, P = 0.015), whereas leptin levels were markedly elevated (median 1.89 ng/mL vs 0.62 ng/mL, P < 0.001). Consequently, the L/A ratio was also significantly higher in the MASLD group (1.63 vs 0.27, P < 0.001), reflecting a pronounced imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory adipokines. Imaging-based markers of hepatic steatosis also differed significantly, with higher CAP values in the MASLD group (median 278.50 dB/m vs 199 dB/m, P < 0.001). However, no significant difference in liver stiffness measured by transient elastography was observed (P = 0.176). A detailed comparison is presented in Table 3.

| PBC/no MASLD | PBC/MASLD | P value | |

| Number of patients, n (%) | 42 (51.90) | 39 (48.90) | |

| Age (years) | 63.00 ± 11.70 | 65.00 ± 8.20 | 0.4521 |

| BMI | 23.50 ± 3.80 | 30.40 ± 4.00 | < 0.0011 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 81.40 ± 9.10 | 99.10 ± 10.30 | < 0.0011 |

| AST (% of ULN) | 86.67 (IQR 46.67) | 84.93 (IQR 20.00) | 0.1463 |

| ALT (% of ULN) | 85.65 (IQR 57.50) | 73.33 (IQR 40.00) | 0.7583 |

| GGT (% of ULN) | 136.51 (IQR 236.51) | 95.24 (IQR 112.70) | 0.0413 |

| ALP (% of ULN) | 95.00 (IQR 51.50) | 87.50 (IQR 47.00) | 0.0773 |

| Bil-T (μmol/L) | 12.80 (IQR 6.30) | 11.20 (IQR 6.80) | 0.3923 |

| Bil-C (μmol/L) | 2.62 (IQR 1.24) | 2.13 (IQR 2.04) | 0.4363 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.20 (IQR 1.00) | 5.5 (IQR 1.50) | 0.3733 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 1.49 (IQR 0.85) | 2.44 (IQR 1.47) | 0.0803 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.42 (IQR 1.95) | 5.13 (IQR 2.56) | 0.1413 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.43 ± 1.23 | 5.17 ± 1.22 | 0.3271 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.84 ± 0.43 | 1.49 ± 0.36 | < 0.0011 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.33 (IQR 1.39) | 3.47 (IQR 1.06) | 0.8392 |

| Ferritin (mg/L) | 52.90 (IQR 56.80) | 93.15 (IQR 118.80) | 0.0042 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.97 (IQR 0.45) | 1.18 (IQR 0.87) | < 0.0013 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 242.5 (IQR 90.25) | 236 (IQR 109.25) | 0.3063 |

| Adiponectin (pg/mL) | 2042.08 (IQR 2678.16) | 1698.24 (IQR 1998.92) | 0.0152 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 0.62 (IQR 0.83) | 1.89 (IQR 2.01) | < 0.0012 |

| CAP (dB/m) | 199.00 (IQR 35.00) | 278.50 (IQR 55) | < 0.0012 |

| Liver stiffness (TE, kPa) | 6.70 (IQR 4.20) | 6.55 (IQR 7.70) | 0.1762 |

| L/A ratio | 0.27 (IQR 0.37) | 1.63 (IQR 3.42) | < 0.0012 |

Among the 81 PBC patients, 33 (40.70%) met the criteria for MetS, while 48 (59.30%) did not. Patients with MetS were older on average (68.90 ± 8.80 years vs 60.60 ± 9.70 years, P = 0.001) and had higher BMI (28.90 ± 5.20 kg/m2vs 25.40 ± 4.80 kg/m2, P = 0.002) and waist circumference (97.20 ± 12.20 cm vs 84.90 ± 11.30 cm, P < 0.001), reflecting a greater burden of metabolic risk.

Adiponectin levels were significantly lower in MetS patients (median 1208.41 pg/mL vs 2086.10 pg/mL, P = 0.002), whereas leptin levels were higher (median 1.51 ng/mL vs 0.79 ng/mL, P = 0.002), consistent with the characteristic adipokine imbalance of MetS. Accordingly, the L/A ratio was significantly elevated in the MetS group (1.28 vs 0.41, P = 0.009), paralleling findings in MASLD patients. A detailed comparison is presented in Table 4.

| PBC/no MetS | PBC/MetS | P value | |

| Number of patients, n (%) | 48 (59.30) | 33 (40.70) | |

| Age (years) | 60.60 ± 9.70 | 68.90 ± 8.80 | 0.0011 |

| BMI | 25.40 ± 4.80 | 28.90 ± 5.20 | 0.0021 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 84.90 ± 11.30 | 97.20 ± 12.20 | < 0.0011 |

| AST (% of ULN) | 81.67 (IQR 26.67) | 78.33 (IQR 70.54) | 0.4403 |

| ALT (% of ULN) | 71.67 (IQR 39.58) | 70.00 (IQR 47.50) | 0.7403 |

| GGT (% of ULN) | 112.70 (IQR 203.17) | 114.29 (IQR 143.65) | 0.6893 |

| ALP (% of ULN) | 94.50 (IQR 55.00) | 89.50 (IQR 38.80) | 0.2513 |

| Bil-T (μmol/L) | 11.80 (IQR 5.80) | 12.10 (IQR 8.00) | 0.9303 |

| Bil-C (μmol/L) | 2.27 (IQR 1.43) | 2.36 (IQR 2.27) | 0.9183 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.10 (IQR 0.10) | 6.00 (IQR 1.70) | < 0.0013 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 1.45 (IQR 0.81) | 2.31 (IQR 1.30) | < 0.0013 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.27 (IQR 1.65) | 5.79 (IQR 3.38) | 0.0013 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.62 ± 1.06 | 4.84 ± 1.31 | 0.0061 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.87 ± 0.35 | 1.39 ± 0.38 | < 0.0011 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.49 (IQR 0.97) | 2.94 (IQR 1.35) | 0.0292 |

| Ferritin (mg/L) | 67.40 (IQR 83.00) | 73.85 (IQR 78.20) | 0.2702 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.98 (IQR 0.38) | 1.34 (IQR 0.98) | < 0.0013 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 244 (IQR 90.50) | 226 (IQR 127.5) | 0.1693 |

| Adiponectin (pg/mL) | 2086.10 (IQR 2260.08) | 1208.41 (IQR 3127.60) | 0.0022 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 0.79 (IQR 1.11) | 1.51 (IQR 2.43) | 0.0022 |

| CAP (dB/m) | 213 (IQR 62) | 254 (IQR 98) | 0.0012 |

| Liver stiffness (TE, kPa) | 6.70 (IQR 3.80) | 7.2 (IQR 8.03) | 0.0272 |

| L/A ratio | 0.41 (IQR 0.59) | 1.28 (IQR 2.36) | 0.0092 |

PBC patients were stratified according to the presence of advanced fibrosis (stage F3-F4). Advanced fibrosis was identified in 19 patients (23.50%), while 62 patients (76.50%) did not meet this criterion. We observed following differences related to metabolic dysfunction in patients with advanced fibrosis: Fasting glucose (5.70 mmol/L vs 5.10 mmol/L, P = 0.003), C-peptide (2.27 ng/mL vs 1.68 ng/mL, P = 0.031), and HOMA-IR (6.43 vs 4.70, P = 0.003) were elevated in the advanced fibrosis group. HDL-C was significantly lower (1.47 mmol/L vs 1.73 mmol/L, P = 0.022), whereas total and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol not differ significantly. Adiponectin and leptin levels, as well as the L/A ratio, did not differ significantly between groups. A detailed comparison is presented in Table 5.

| PBC/no advFib | PBC/advFib | P value | |

| Number of patients, n (%) | 62 (76.50) | 19 (23.50) | |

| Age (years) | 63.60 ± 10.20 | 65.10 ± 10.00 | 0.5411 |

| BMI | 26.40 ± 5.10 | 28.20 ± 5.60 | 0.2141 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 88.70 ± 12.40 | 94.0 ± 15.00 | 0.1231 |

| AST (% of ULN) | 78.33 (IQR 34.16) | 90.00 (IQR 71.67) | 0.0393 |

| ALT (% of ULN) | 71.67 (IQR 50.00) | 63.33 (IQR 38.33) | 0.4063 |

| GGT (% of ULN) | 112.70 (IQR 133.34) | 142.86 (IQR 266.67) | 0.1953 |

| ALP (% of ULN) | 92.50 (IQR 49.30) | 92.50 (IQR 47.00) | 0.8883 |

| Bil-T (μmol/L) | 11.20 (IQR 5.50) | 17.50 (IQR 16.80) | 0.0013 |

| Bil-C (μmol/L) | 2.22 (IQR 1.42) | 3.99 (IQR 3.52) | 0.0013 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.10 (IQR 1.00) | 5.70 (IQR 2.00) | 0.0033 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 1.68 (IQR 1.23) | 2.27 (IQR 1.19) | 0.0313 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.70 (IQR 1.81) | 6.43 (IQR 4.59) | 0.0033 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.43 ± 1.24 | 4.88 ± 1.09 | 0.0891 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.73 ± 0.42 | 1.47 ± 0.43 | 0.0221 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.46 (IQR 1.12) | 2.99 (IQR 1.28) | 0.2212 |

| Ferritin (mg/L) | 76.90 (IQR 81.50) | 52.65 (IQR 65.30) | 0.8492 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.06 (IQR 0.51) | 1.05 (IQR 0.62) | 0.4763 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 250 (IQR 86.50) | 175.5 (IQR 153.70) | < 0.0013 |

| Adiponectin (pg/mL) | 1955.46 (IQR 2663.73) | 1782.70 (IQR 1854.27) | 0.7562 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 1.09 (IQR 1.64) | 1.12 (IQR 1.89) | 0.5152 |

| CAP (dB/m) | 216.00 (IQR 67) | 259.00 (IQR 82) | 0.2092 |

| Liver stiffness (TE, kPa) | 5.60 (IQR 2.75) | 14.95 (IQR 7.70) | < 0.0012 |

| L/A ratio | 0.46 (IQR 1.33) | 1.05 (IQR 2.07) | 0.4822 |

Patients with PBC were categorized according to the presence or absence of CBR, which was assessed in 80 of the 81 patients. Among them, 45 (56.30%) achieved CBR and 35 (43.80%) did not. No significant differences were observed in anthropometric parameters, liver enzymes or bilirubin. ALP was significantly lower in the CBR group (78.00% vs 117.50% upper limit of normal, P < 0.001). Glycemic parameters (glucose, C-peptide, HOMA-IR) and lipid profiles (total cholesterol, HDL-C, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, TG) showed no significant differences. No significant differences were observed in adipokine concentrations (adiponectin, leptin, or L/A ratio) or in CAP values as a marker of hepatic steatosis. However, liver stiffness measured by transient elastography was significantly higher in patients without CBR (7.20 kPa vs 6.20 kPa, P = 0.022). A detailed comparison is presented in Table 6.

| PBC/ no CBR | PBC/CBR | P value | |

| Number of patients, n (%) | 35 (43.80) | 45 (56.30) | |

| Age (years) | 63.00 ± 8.70 | 64.70 ± 11.10 | 0.5451 |

| BMI | 27.10 ± 5.70 | 26.70 ± 4.90 | 0.7511 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 88.90 ± 13.90 | 90.60 ± 12.50 | 0.6501 |

| AST (% of ULN) | 83.33 (IQR 158.33) | 78.33 (IQR 51.57) | 0.2733 |

| ALT (% of ULN) | 66.67 (IQR 40.00) | 71.67 (IQR 58.34) | 0.4703 |

| GGT (% of ULN) | 126.98 (IQR 223.81) | 109.52 (IQR 104.77) | 0.0623 |

| ALP (% of ULN) | 117.50 (IQR 75.00) | 78.00 (IQR 31.30) | < 0.0013 |

| Bil-T (μmol/L) | 11.30 (IQR 16.00) | 12.2 (IQR 5.5) | 0.3423 |

| Bil-C (μmol/L) | 2.66 (IQR 3.35) | 2.36 (IQR 1.42) | 0.2163 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.30 (IQR 0.90) | 5.30 (IQR 1.30) | 0.8123 |

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | 1.84 (IQR 1.63) | 1.90 (IQR 1.12) | 0.7343 |

| HOMA-IR | 5.13 (IQR 3.63) | 4.75 (IQR 1.85) | 0.0863 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.51 ± 1.18 | 5.15 ± 1.24 | 0.2071 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.74 ± 0.44 | 1.62 ± 0.42 | 0.3081 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.48 (IQR 1.01) | 3.33 (IQR 1.28) | 0.1302 |

| Ferritin (mg/L) | 60.15 (IQR 54.30) | 83.40 (IQR 122.5) | 0.3042 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.05 (IQR 0.51) | 1.09 (IQR 0.53) | 0.8543 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 260 (IQR 151) | 230 (IQR 81) | 0.9963 |

| Adiponectin (pg/mL) | 1998.77 (IQR 2537.98) | 1769.42 (IQR 2447.19) | 0.6942 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 1.95 ± 2.53 | 1.95 ± 3.46 | 0.9022 |

| CAP (dB/m) | 218.00 (IQR 62) | 247.00 (IQR 82) | 0.2342 |

| Liver stiffness (TE, kPa) | 7.20 (IQR 8.60) | 6.20 (IQR 3.85) | 0.0222 |

| L/A ratio | 0.68 (IQR 1.32) | 0.47 (IQR 1,77) | 0.6572 |

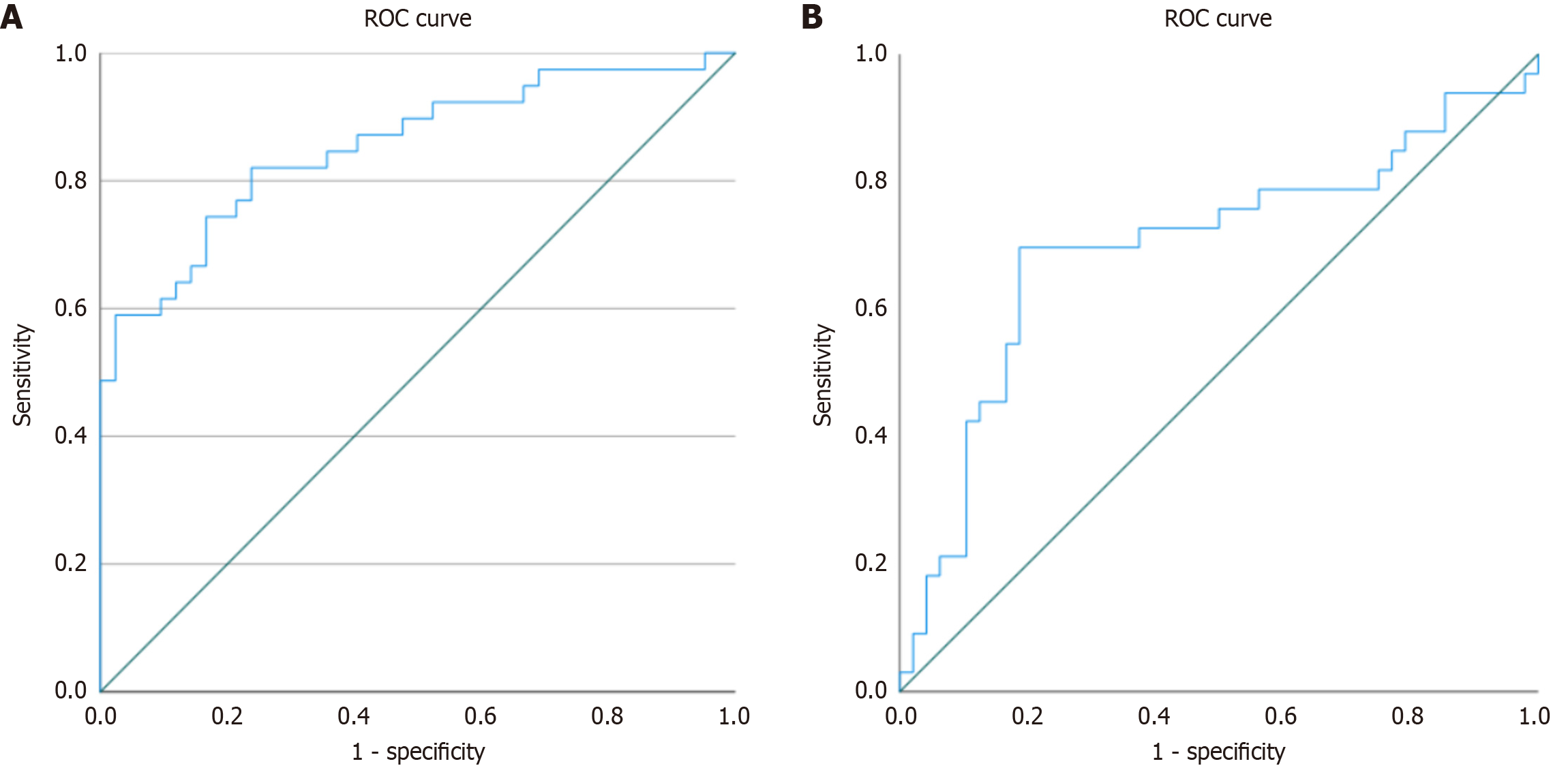

To investigate the association between the L/A ratio and MASLD among patients with PBC, a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed. BMI was included in the model as a covariate to adjust for confounding. The model was statistically significant (χ2 = 57.52, df = 2, P < 0.001) with strong explanatory power (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.684). Both the log-transformed L/A ratio and BMI were independently associated with MASLD (P = 0.003 and P < 0.001, respectively). The odds ratio (OR) for the log-L/A ratio was 2.312 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.336-4.003], and for BMI 1.485 (95%CI: 1.214-1.817), indicating that higher values of both predictors significantly increased the likelihood of MASLD. The discriminative ability of the log-transformed L/A ratio for identifying MASLD was further evaluated using ROC analysis, yielding an AUC of 0.853 (95%CI: 0.770-0.937, P < 0.001), which indicates very good discriminatory performance. The corresponding ROC curve is displayed in Figure 1A.

To examine whether the L/A ratio is associated with MetS in patients with PBC, a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed. BMI was included in the model as a key covariate. The model was statistically significant. Among the predictors, BMI was significantly associated with MetS, with each unit increase in BMI raising the odds of MetS (OR = 1.115, 95%CI: 1.001-1.242, P = 0.047). By contrast, the log-transformed L/A ratio was not a significant predictor (OR = 1.288, 95%CI: 0.888-1.869, P = 0.183). The discriminative ability of the L/A ratio for predicting MetS was further evaluated using ROC analysis, which yielded an AUC of 0.689 (95%CI: 0.573-0.824, P = 0.003), indicating moderate discriminatory performance. The corresponding ROC curve is shown in Figure 1B.

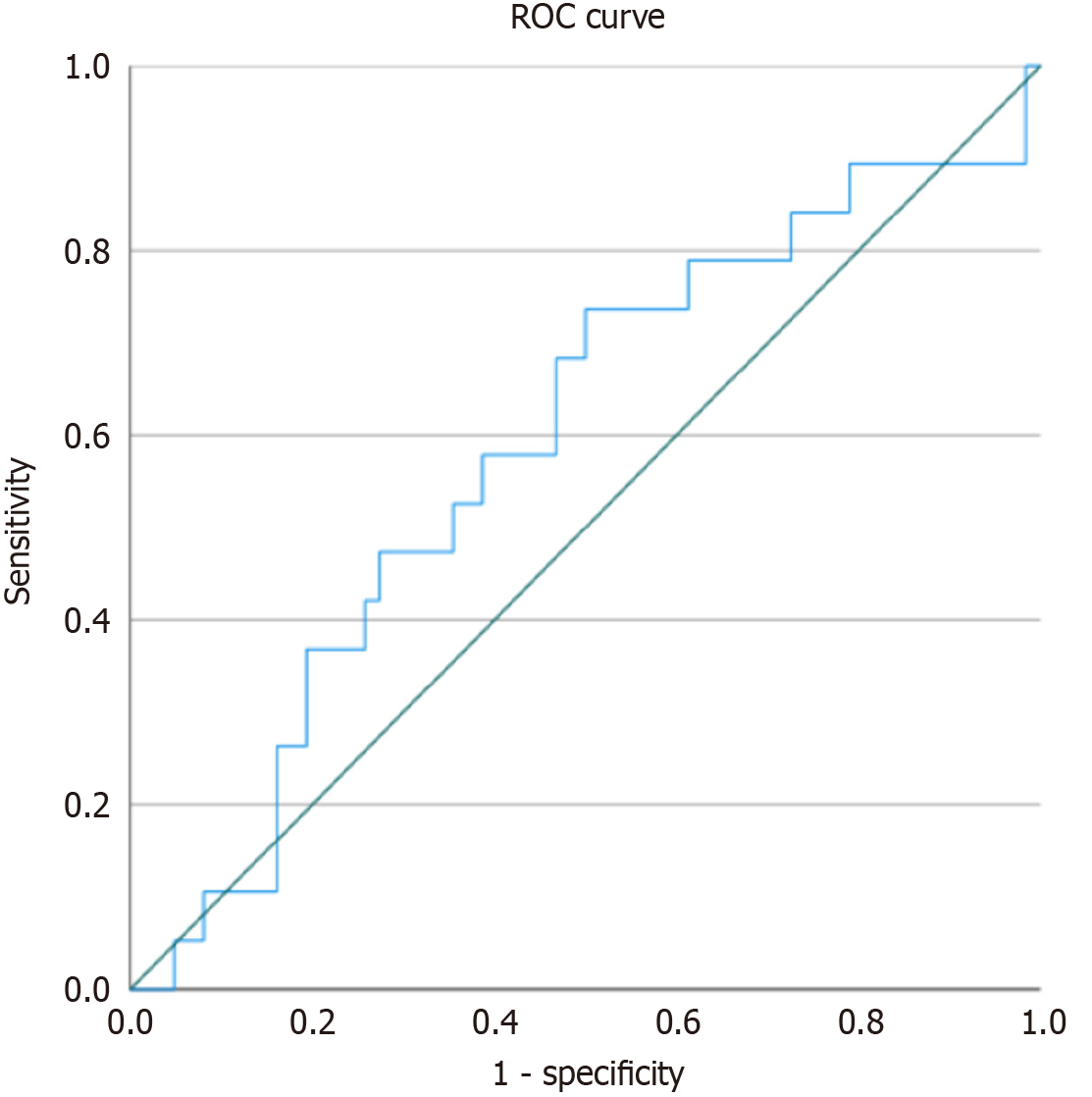

To evaluate whether the L/A ratio is associated with advanced fibrosis in patients with PBC, a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed. The model was adjusted for age, BMI, and achievement of CBR. We have included CBR, as a favourable post-treatment outcome, into the model because we anticipate its association with fibrosis, although we obviously cannot prove it is causality in this dataset. Discriminative ability of the log-transformed L/A ratio was additionally assessed using ROC analysis with calculation of the AUC. Among the included variables, only CBR was statistically significant (B = -1.299, P = 0.025), indicating an association with reduced likelihood of advanced fibrosis. The log-transformed L/A ratio, age, and BMI did not show significant associations (all P > 0.05). Overall, despite slight overfitting (4 predictors for 19 outcome cases), the model was stable, reached convergence within 5 iterations, showed good calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow P = 0.701) and had modest explanatory power (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.132). Detailed regression results are presented in Table 7. ROC analysis demonstrated limited discriminatory ability of the L/A ratio for detecting advanced fibrosis, with an AUC of 0.589 (95%CI: 0.442-0.737, P = 0.242). Although the CI was wide and non-significant, these findings underscore the need for validation in larger cohorts. The corresponding ROC curve is presented in Figure 2.

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | df | P value | Exp(B) | 95%CI lower | 95%CI upper |

| Log L/A ratio | 0.018 | 0.213 | 0.007 | 1 | 0.934 | 1.018 | 0.670 | 1.545 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.055 | 0.061 | 0.831 | 1 | 0.362 | 1.057 | 0.938 | 1.191 |

| Age (years) | 0.022 | 0.031 | 0.502 | 1 | 0.478 | 1.022 | 0.962 | 1.085 |

| CBR | -1.299 | 0.581 | 5.009 | 1 | 0.025 | 0.273 | 0.087 | 0.851 |

| Constant | -3.489 | 2.543 | 1.882 | 1 | 0.170 | 0.031 | - | - |

In our study, we found that leptin levels and the L/A ratio were higher and adiponectin levels were lower in patients who had both PBC and MASLD compared to patients with PBC alone. On the other hand, both leptin and adiponectin levels, as well as the L/A ratio, were comparable in patients with advanced fibrosis and patients without advanced fibrosis. Both leptin and adiponectin levels and also the L/A ratio did not differ in patients with and without CBR. In our study, we did not compare adiponectin and leptin levels in patients with PBC, patients with MASLD without PBC, and healthy controls, which partially limits the conclusions of our research.

It is well known that serum leptin levels are higher in liver steatosis compared to healthy controls and leptin levels correlate with the stage of steatosis and fibrosis in MASLD patients, and it may play a role in the pathophysiology of hepatocellular cancer in this patient cohort[17,18]. Data on leptin levels in PBC are controversial. In observational studies conducted on small cohorts of patients in the past was documented that PBC patients had significantly lower serum leptin levels compared to healthy controls. Serum leptin levels in PBC patients did not correlate with disease severity or histological findings[19,20]. Paradoxically, in another study, PBC patients had higher leptin levels than NASH patients or healthy controls, but no relationship was found between leptin levels and histological progression of PBC[21]. We did not find a correlation between serum leptin levels and fibrosis stage in our study either. Leptin does not appear to play a major role in the pathophysiology of fibrogenesis in PBC patients.

Adiponectin is generally considered an anti-inflammatory adipokine that enhances insulin sensitivity and is typically reduced in obesity, MetS, and MASLD. Recent reviews confirm its strong inverse relationship with hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance, and its potential predictive role in MASLD development, especially in patients with diabetes[22]. Adiponectin levels inversely correlate with the stage of liver fibrosis in fatty liver disease[23]. In PBC, however, paradoxically elevated adiponectin levels have been reported. Floreani et al[21] in 2008 observed that adiponectin was significantly higher in isolated PBC compared to both healthy controls and patients with NASH, and levels correlated positively with histological progression but inversely with BMI. It should be noted that in this study, there was a higher incidence of patients with advanced PBC. However, authors did not consider any patients with PBC to have a concomitant NASH. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis showed that adiponectin is significantly elevated in cirrhosis. The increased levels of anti-inflammatory adiponectin may reflect a compensatory response to chronic inflammation and fibrosis, or result from impaired hepatic clearance[21,24,25].

Adiponectin levels were, in agreement with Floreani et al[21] in 2008, significantly lower in our cohorts of both PBC/MASLD and PBC/MetS patients than in those with isolated PBC, which probably reflects the prevalence of metabolic dysfunction in these subgroups. On the other hand, no significant differences were observed based on the biochemical response to the PBC treatment or the stage of fibrosis, indicating that the levels of adiponectin in PBC might reflect a balance between the opposing processes of cholestatic upregulation and metabolic downregulation.

The explanation for why leptin and adiponectin correlate with the stage of fibrosis in MASLD but not in PBC is provided by the pathophysiology of fibrogenesis in both diseases. The pathophysiology of fibrogenesis in hepatic steatosis is multifactorial. Activation of hepatic stellate cells by different pathophysiological pathways plays a key role in fibrogenesis[26]. The most important pathogenetic mechanisms accelerating fibrogenesis in hepatic steatosis are: Insulin resistance, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation in the liver. Adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines also par

The pathophysiology of fibrogenesis in cholestasis differs from that in MASLD. Liver fibrosis does not occur in pure intrahepatic cholestasis in the absence of hepatocellular damage, lobular inflammation and bile duct damage and/or proliferation. Advanced stages of intrahepatic cholestasis lead to biliary damage and accumulation of bile salts in liver tissue. Bile acids are cytotoxic, activating hepatic stellate cells which leads to liver cell necrosis and activation of fibrogenesis. In PBC patients, there is an inflammatory infiltrate in the portal tract that also activates hepatic stellate cells. Adipokines probably do not play a significant role in the development of liver fibrosis in PBC[28].

An interesting finding was that PBC patients with advanced fibrosis had higher HOMA-IR values compared to PBC patients without advanced fibrosis. A similar association was seen in a Japanese study with a small number of PBC patients[29]. We can speculate that insulin resistance may play a role in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis in PBC patients.

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis and staging of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. However, in routine clinical practice, histological evaluation is not recommended for establishing the diagnosis of either MASLD or PBC[1,8]. Instead, hepatic steatosis and fibrosis can be assessed using laboratory-based or elastographic methods, particularly transient elastography.

Transient elastography, although widely used, has several limitations in evaluating liver fibrosis. Fibrosis stage may be overestimated in the presence of hepatic inflammation, cholestasis (especially extrahepatic cholestasis), or marked hepatic steatosis. Moreover, the accuracy of the measurement depends on the operator’s experience and is subject to interobserver variability[16]. Nevertheless, in PBC patients, transient elastography has demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance, with area under the ROC values of 0.91 for ≥ F2, 0.95 for ≥ F3, and 0.99 for F4 fibrosis stages[15], partially mitigating these limitations.

For the non-invasive quantification of hepatic fat accumulation, the CAP represents the current reference standard. However, CAP values may be influenced by factors such as body composition, the presence of diabetes or hyperlipidemia, and operator experience[30]. Another limitation is that the CAP cut-off values used to define steatosis grades S1-S3 were derived from general MASLD populations[8], whereas specific thresholds for PBC patients have not yet been established.

The L/A ratio integrates the opposing metabolic actions of adiponectin and leptin and has been proposed as a more sensitive marker of metabolic dysfunction than either adipokine individually. Our results confirm this, showing a marked increase in patients with MASLD and MetS and strong discriminative power for MASLD (AUC 0.853) in PBC patients. This result is less convincing in the case of MetS in PBC patients, where L/A ratio’s AUC is much lower and also it is not independent of BMI. This can be probably attributed to the different definitions of MASLD and MetS, where MASLD does not require the presence of obesity in each positive case. Our results do not show association of L/A ratio with advanced fibrosis, but the cross-sectional design of the study precludes us to assess the long-term effect or causality of metabolic dysregulation on liver fibrosis. Data on adipokines in PBC with metabolic overlap are limited. Alempijevic et al[31] in 2012 were among the first to describe the clinical importance of metabolic comorbidities in PBC, but adipokine profiling has been underexplored. Our findings add novel evidence that adipokines-and especially the L/A ratio-capture the presence of concomitant MASLD or MetS in PBC patients, bridging autoimmune hepatology with metabolic liver disease.

Although PBC is a rare disease[2], the study has several limitations. First, its monocentric design and relatively small sample size limit the generalizability of the findings. The small number of participants also reduces the statistical power, in particular, the analysis of advanced fibrosis (only 19 patients, 23.5%) may be underpowered to detect true associations between advanced fibrosis and adipokines, potentially leading to false-negative results. Another limitation lies in the assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis using elastography rather than histological evaluation. Several factors could have influenced adipokine levels in our cohort. Leptin concentrations are higher in individuals with obesity, a diagnostic criterion for MetS and in those with MASLD, which may overstate the discriminatory power of the L/A ratio for MASLD. Moreover, lifestyle factors (such as physical activity and diet) and potential pharmacological interventions that might affect adipokine levels were not evaluated in this study. Finally, PBC predominantly affects women, and only a very small proportion of men (3.70%) were included in our analysis. Given that adipokine levels (e.g., leptin) exhibit pronounced sexual dimorphism[32], the results, derived almost exclusively from female participants, cannot be directly extrapolated to male patients with PBC. In addition, we lacked a control group of either healthy individuals or patients with isolated MASLD which would have provided a positive and negative reference for adiponectin and leptin levels. A limitation of our study is that the potential confounding effects of concomitant medications such as antidiabetic agents, statins, and hormone replacement therapy were not included in the statistical model. Another limitation was the fact that a small group of PBC patients was treated with statins or antidiabetic drugs. Therefore, although a residual confounding effect cannot be entirely excluded, the overall impact of these factors on adipokine levels in our cohort is likely to be limited. In addition, information on lifestyle-related variables (e.g., physical activity, dietary habits) and fat distribution beyond BMI and waist circumference was not available. We acknowledge that these unmeasured parameters could influence circulating adipokine concentrations and metabolic profiles, and they should be addressed in future prospective studies employing more detailed metabolic and imaging assessments.

In our study, patients with PBC with MASLD or MetS showed higher leptin levels, lower adiponectin levels, and consequently an elevated L/A ratio. Conversely, within the limited sample size of this study, no significant difference was found between adipokine levels on the one hand and biochemical response to UDCA treatment or advanced fibrosis on the other. These findings suggest that adipokines, particularly the L/A ratio, may serve as indicators of underlying metabolic dysfunction in PBC, while they can not be used as markers of disease severity or PBC treatment response.

In summary, our findings indicate that adiponectin, leptin, and the L/A ratio reflect the metabolic status of patients with PBC, with pronounced differences in those with concomitant MASLD or MetS. The association of L/A ratio with MASLD is more pronounced and also BMI independent than in MetS, probably due to the close relation of L/A ratio with obesity, which is a mandatory component of MetS, but not MASLD. The L/A ratio demonstrated especially strong discriminative power for MASLD, supporting its potential as a simple, non-invasive biomarker for MASLD. By contrast, no associations were observed with advanced fibrosis or PBC treatment response. Larger multicenter study is warranted to further clarify the role of adipokines, especially the L/A ratio in the PBC patients.

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 950] [Cited by in RCA: 1016] [Article Influence: 112.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Gazda J, Drazilova S, Janicko M, Jarcuska P. The Epidemiology of Primary Biliary Cholangitis in European Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:9151525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gulamhusein AF, Hirschfield GM. Primary biliary cholangitis: pathogenesis and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:93-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Drazilova S, Koky T, Macej M, Janicko M, Simkova D, Tsedendamba A, Komarova S, Jarcuska P. Pruritus, Fatigue, Osteoporosis and Dyslipoproteinemia in Pbc Patients: A Clinician’s Perspective. Gastroenterol Insights. 2024;15:419-432. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Drazilova S, Babinska I, Gazda J, Halanova M, Janicko M, Kucinsky B, Safcak D, Martinkova D, Tarbajova L, Cekanova A, Jarcuska P; Eastern Slovakia PBC Group. Epidemiology and clinical course of primary biliary cholangitis in Eastern Slovakia. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:683-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gazda J, Drazilova S, Gazda M, Janicko M, Koky T, Macej M, Carbone M, Jarcuska P. Treatment response to ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cholangitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:1318-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Floreani A, Gabbia D, De Martin S. Reviewing novel findings and advances in diagnoses and treatment of primary biliary cholangitis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;19:891-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. 2024;81:492-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 993] [Article Influence: 496.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Liu Y, Qian SW, Tang Y, Tang QQ. The secretory function of adipose tissues in metabolic regulation. Life Metab. 2024;3:loae003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pogodziński D, Ostrowska L, Smarkusz-Zarzecka J, Zyśk B. Secretome of Adipose Tissue as the Key to Understanding the Endocrine Function of Adipose Tissue. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cerabino N, Di Chito M, Guido D, Di Stasi V, Bonfiglio C, Lisco G, Shahini E, Zappimbulso M, Cozzolongo R, Tutino V, Diciolla A, Mallamaci R, Stabile D, Ancona A, Coletta S, Pesole PL, Giannelli G, De Pergola G. Liver Fibrosis Is Positively and Independently Associated with Leptin Circulating Levels in Individuals That Are Overweight and Obese: A FibroScan-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2025;17:1908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marques V, Afonso MB, Bierig N, Duarte-Ramos F, Santos-Laso Á, Jimenez-Agüero R, Eizaguirre E, Bujanda L, Pareja MJ, Luís R, Costa A, Machado MV, Alonso C, Arretxe E, Alustiza JM, Krawczyk M, Lammert F, Tiniakos DG, Flehmig B, Cortez-Pinto H, Banales JM, Castro RE, Normann A, Rodrigues CMP. Adiponectin, Leptin, and IGF-1 Are Useful Diagnostic and Stratification Biomarkers of NAFLD. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:683250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hutchison AL, Tavaglione F, Romeo S, Charlton M. Endocrine aspects of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Beyond insulin resistance. J Hepatol. 2023;79:1524-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 50.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3852] [Cited by in RCA: 4397] [Article Influence: 219.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Corpechot C, Heurgue A, Tanne F, Potier P, Hanslik B, Decraecker M, de Lédinghen V, Ganne-Carrié N, Bureau C, Bourlière M. Non-invasive diagnosis and follow-up of primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;46:101770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Perazzo H, Veloso VG, Grinsztejn B, Hyde C, Castro R. Factors That Could Impact on Liver Fibrosis Staging by Transient Elastography. Int J Hepatol. 2015;2015:624596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Qamar M, Fatima A, Tauseef A, Yousufzai MI, Liaqat I, Naqvi Q. Comparative and Predictive Significance of Serum Leptin Levels in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cureus. 2024;16:e57943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jiménez-Cortegana C, García-Galey A, Tami M, Del Pino P, Carmona I, López S, Alba G, Sánchez-Margalet V. Role of Leptin in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Biomedicines. 2021;9:762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Szalay F, Folhoffer A, Horváth A, Csak T, Speer G, Nagy Z, Lakatos P, Horváth C, Habior A, Tornai I, Lakatos PL. Serum leptin, soluble leptin receptor, free leptin index and bone mineral density in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:923-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rieger R, Oertelt S, Selmi C, Invernizzi P, Podda M, Gershwin ME. Decreased serum leptin levels in primary biliary cirrhosis: a link between metabolism and autoimmunity? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1051:211-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Floreani A, Variola A, Niro G, Premoli A, Baldo V, Gambino R, Musso G, Cassader M, Bo S, Ferrara F, Caroli D, Rizzotto ER, Durazzo M. Plasma adiponectin levels in primary biliary cirrhosis: a novel perspective for link between hypercholesterolemia and protection against atherosclerosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1959-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fajkić A, Jahić R, Hadžović-Džuvo A, Lepara O. Adipocytokines as Predictors of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) Development in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Cureus. 2024;16:e55673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mohamed MS, Youssef TM, Abdullah EE, Ahmed AE. Correlation between adiponectin level and the degree of fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Egypt Liver J. 2021;11:78. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Salman TA, Allam N, Azab GI, Shaarawy AA, Hassouna MM, El-Haddad OM. Study of adiponectin in chronic liver disease and cholestasis. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:767-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Silva TE, Colombo G, Schiavon LL. Adiponectin: A multitasking player in the field of liver diseases. Diabetes Metab. 2014;40:95-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jarcuska P, Janicko M, Veselíny E, Jarcuska P, Skladaný L. Circulating markers of liver fibrosis progression. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1009-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bian Z, Ma X. Liver fibrogenesis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Front Physiol. 2012;3:248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pinzani M, Luong TV. Pathogenesis of biliary fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:1279-1283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Himoto T, Yoneyama H, Kurokochi K, Inukai M, Masugata H, Goda F, Haba R, Watanabe S, Senda S, Masaki T. Contribution of zinc deficiency to insulin resistance in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;144:133-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sirli R, Sporea I. Controlled Attenuation Parameter for Quantification of Steatosis: Which Cut-Offs to Use? Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:6662760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Alempijevic T, Sokic-Milutinovic A, Pavlovic Markovic A, Jesic-Vukicevic R, Milicic B, Macut D, Popovic D, Tomic D. Assessment of metabolic syndrome in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:251-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fuente-Martín E, Argente-Arizón P, Ros P, Argente J, Chowen JA. Sex differences in adipose tissue: It is not only a question of quantity and distribution. Adipocyte. 2013;2:128-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/