Published online Feb 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113695

Revised: October 6, 2025

Accepted: December 5, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2026

Processing time: 164 Days and 21.8 Hours

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) is increasingly recognized worldwide. In Asia, Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) has emerged as the predominant pathogen, yet contemporary data from Vietnam remain limited.

To determine the microbial spectrum of PLA and compare clinical, computed tomography (CT), management, and outcomes between K. pneumoniae and non-K. pneumoniae cases in Southern Vietnam.

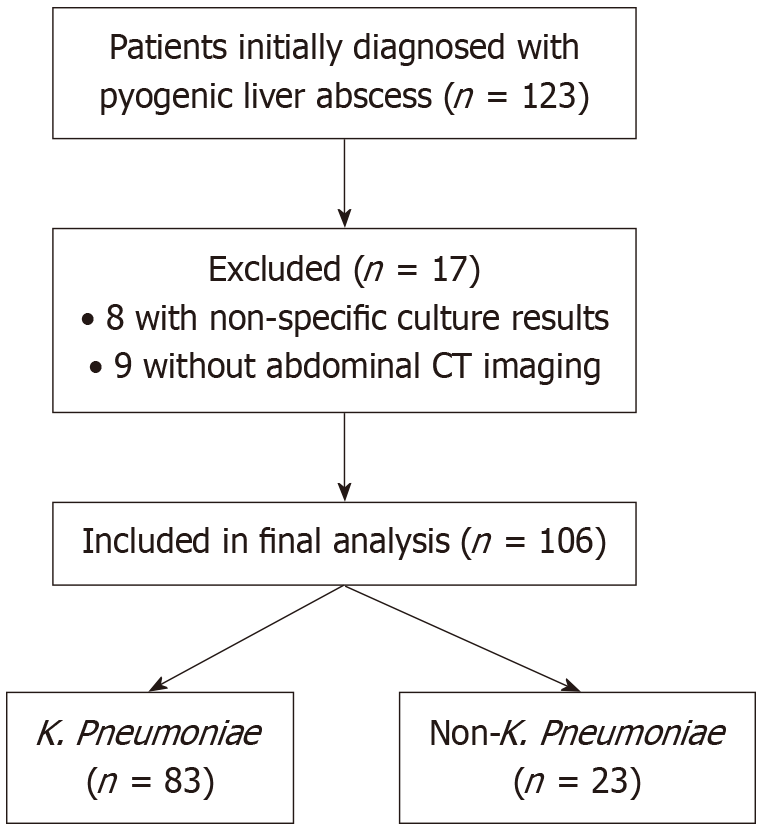

This retrospective cohort included adults with PLA managed at Nhan Dan Gia Dinh Hospital from June 2021 to June 2024. Of 123 cases, 17 were excluded (8 with unspecified Gram-negative bacilli, 9 without CT), leaving 106 patients (83 K. pneumoniae, 23 non-K. pneumoniae). Data on demographics, comorbidities, presen

Mean age was 59.2 years, and 67.0% were male. Diabetes was more frequent in K. pneumoniae (55.4% vs 30.4%; P = 0.034). C-reactive protein was higher in K. pneumoniae but not significant (229.9 mg/L vs 185.0 mg/L; P = 0.069). Aspartate aminotransferase was significantly elevated (P = 0.048) and alanine aminotransferase borderline (P = 0.065). On CT, K. pneumoniae abscesses more often had irregular margins (P = 0.038) and heterogeneous archi

In Southern Vietnam, K. pneumoniae predominates in PLA, characterized by distinctive CT features and higher mortality, emphasizing early recognition, pathogen-directed therapy, and timely image-guided drainage.

Core Tip: This three-year study from a tertiary hospital in Southern Vietnam shows that Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) is now the leading cause of pyogenic liver abscess, responsible for nearly 80 percent of cases. Patients with K. pneumoniae infection were more likely to have diabetes, higher inflammatory markers, and typical computed tomography findings with irregular margins and heterogeneous internal structure. All deaths in this cohort occurred in the K. pneumoniae group. These results highlight the importance of early antibiotic coverage active against K. pneumoniae, timely image-guided drainage, and close clinical monitoring in areas where this organism is common.

- Citation: Mai-Phan TA, Thai KP, Le KL, Pham TN, Tran MQ, Pham PC, Duong NNQ, Trinh MT, Le NK. Klebsiella pneumoniae as leading cause of pyogenic liver abscess: Three years study in Southern Vietnam. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(2): 113695

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i2/113695.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i2.113695

Liver abscesses are a serious global health problem with rising incidence. Reported rates are 2.3-3.6 per 100000 in Europe and the Americas but reach 14-18 per 100000 in Asia, where the condition is endemic[1-3]. Mortality remains substantial, ranging from 2% to 31%[4]. If untreated, abscesses can lead to sepsis, multiorgan failure, and death. The rising prevalence of diabetes mellitus, malignancy, chronic kidney disease, and widespread use of immunosuppressants has contributed to the increasing disease burden.

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA), which accounts for about 80% of liver abscesses, is predominantly bacterial. Historically, Escherichia coli (E. coli) and polymicrobial infections secondary to intra-abdominal pathology such as appendicitis or diverticulitis were common causes, particularly in Western countries[4]. In recent decades, however, hepatobiliary diseases and interventional procedures have become increasingly important risk factors. Advances in microbiology have also reshaped understanding of the causative spectrum: In Asia, Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) has overtaken E. coli as the predominant pathogen[4]. Unlike most bacteria associated with biliary tract disease, K. pneumoniae abscesses are often cryptogenic, larger in size, and strongly associated with diabetes[5,6].

The emergence of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae strains further complicates the clinical picture[7,8]. These strains harbor enhanced virulence factors that predispose to invasive disease and metastatic complications such as pneumonia, meningitis, and endophthalmitis, sometimes in otherwise healthy hosts. Rising antimicrobial resistance among K. pneumoniae isolates adds another challenge, complicating empirical treatment and raising concerns for patient outcomes.

While numerous studies from Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, and Southeast Asia have confirmed the predominance of K. pneumoniae, data from Vietnam remain limited[9-11]. Most reports have been restricted by small sample sizes, pediatric populations, or single-center design, and few have specifically examined Southern Vietnam. The present study was therefore undertaken to define the current microbial spectrum of PLA and to compare the clinical characteristics and outcomes of K. pneumoniae vs non-K. pneumoniae cases at a large tertiary referral hospital in Ho Chi Minh City. These findings are expected to provide updated insights for empirical therapy and more effective management strategies in this high-burden setting.

This study was designed as a retrospective cohort, conducted at Nhan Dan Gia Dinh Hospital, a tertiary referral center in Southern Vietnam. The manuscript adheres to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology guidelines for cohort studies. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nhan Dan Gia Dinh Hospital (Approval No. 63/NDGĐ-HĐĐĐ), and all procedures complied with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

All adult patients (aged 18 years and older) diagnosed with PLA between June 1, 2021 and June 1, 2024 were retro

Isolates were classified as K. pneumoniae-positive when K. pneumoniae was detected in pus and/or blood cultures, irrespective of concomitant organisms. Cases without K. pneumoniae isolation were coded as non-K. pneumoniae. Patients with polymicrobial cultures were retained and classified in the non-K. pneumoniae arm unless K. pneumoniae was co-isolated.

Medical records were reviewed by two independent investigators. Data extracted included demographic information (age, sex), comorbidities (notably diabetes mellitus and biliary tract disease), and clinical symptoms at presentation (fever, right upper quadrant pain, jaundice). Per institutional policy, only patients with persistent high-grade fever > 38.5 °C were indicated for blood culture testing. Cultures were processed at the microbiology laboratory using the Vitek® au

We extracted laboratory parameters including white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, liver function tests, renal function indicators, and coagulation profiles [international normalized ratio (INR)]. Variables such as hypotension and procalcitonin were initially planned for collection but were excluded due to incomplete or inconsistent documentation in the medical records. Data on treatment modalities, including empirical and definitive antibiotic regimens, drainage techniques (percutaneous vs surgical), and supportive care, were recorded.

Regarding outcomes, only length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality were consistently available and analyzed. Length of stay was treated as a continuous variable without categorization. Since the primary objective of this study was to describe the distribution of bacterial etiologies of PLA and to compare clinical characteristics between the K. pneumoniae and non-K. pneumoniae groups, other outcomes such as treatment failure or complications were not included in the final analysis.

Pulmonary infection was defined radiologically based on the presence of new parenchymal opacities, including consolidation or ground-glass opacities on multislice chest computed tomography (CT), or homogeneous infiltrates on standard posteroanterior chest X-ray, as reported by board-certified radiologists. All patients underwent multislice contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen at the time of hospital admission. Scans were performed using Siemens SOMATOM Definition (Siemens Healthineers Ltd., Germany) and Philips Incisive 64-detector CT systems [Philips Healthcare (Suzhou) Co., Ltd., China]. Dynamic contrast-enhanced protocols included non-contrast, arterial, portal venous, and delayed phases, with tube voltage 120 kVp, tube current 200-250 mAs, collimation 64 mm × 0.6 mm, slice thickness 5 mm, and reconstruction interval 3 mm. A nonionic iodinated contrast medium (1.5 mL/kg, maximum 120 mL) was ad

Data were entered into a secure database and analyzed using R version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or median with inter

The primary objective of this study was to determine the spectrum and frequency of bacterial pathogens in PLA at Nhan Dan Gia Dinh Hospital and identify the dominant species, hypothesized to be K. pneumoniae. Secondary objectives included comparison of clinical presentation, CT imaging features, and outcomes between K. pneumoniae-associated and non-K. pneumoniae cases.

During the study period (June 1, 2021 to June 1, 2024), we analyzed 106 culture-positive cases of PLA with complete clinical and imaging data, as shown in Figure 1. Of these, 83 (78.3%) were associated with K. pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae group) and 23 (21.7%) were non-K. pneumoniae (including other organisms and polymicrobial isolates). The mean age was 59.2 years (SD 15.1), and 71/106 (67.0%) were male. Diabetes mellitus was present in 53/106 (50.0%) overall and was more frequent in the K. pneumoniae group (46/83, 55.4%) than in the non-K. pneumoniae group (7/23, 30.4%; P = 0.034).

Fever was documented in 86/106 (81.1%), right upper quadrant pain in 65/106 (61.3%), and jaundice in 9/106 (8.5%), without significant between-group differences. Mean C-reactive protein was higher in the K. pneumoniae group than in the non-K. pneumoniae group (229.9 mg/L vs 185.0 mg/L), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.069). Aspartate aminotransferase was also higher in the K. pneumoniae group (median 78 U/L vs 37 U/L; P = 0.048), whereas alanine aminotransferase showed a borderline difference (P = 0.065). Other laboratory parameters, including white blood cell count, creatinine, and INR, did not differ significantly between groups. Pulmonary infections were observed in 29 patients (27.4%) overall, with comparable prevalence in K. pneumoniae and non-K. pneumoniae groups (25.3% vs 34.8%; P = 0.367). Detailed results are provided in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 106) | K. pneumoniae (n = 83) | Non-K. pneumoniae (n = 23) | P value1 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 59.2 ± 15.1 | 60.3 ± 13.8 | 55.3 ± 18.9 | 0.248 |

| Male | 71 (67.0) | 56 (67.5) | 15 (65.2) | 0.839 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 53 (50.0) | 46 (55.4) | 7 (30.4) | 0.034 |

| Pulmonary infection | 29 (27.4) | 21 (25.3) | 8 (34.8) | 0.367 |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| Fever | 86 (81.1) | 70 (84.3) | 16 (69.6) | 0.134 |

| Right upper quadrant pain | 65 (61.3) | 52 (62.7) | 13 (56.5) | 0.593 |

| Jaundice | 9 (8.5) | 7 (8.4) | 2 (8.7) | > 0.999 |

| Laboratory tests at baseline | ||||

| WBC, × 109/L | 14.9 (11.4-20.4) | 14.8 (10.7-20.9) | 15.2 (13.6-18.8) | 0.457 |

| CRP, mg/L | 219.0 ± 96.2 | 229.9 ± 99.4 | 185.0 ± 78.4 | 0.069 |

| Missing (CRP)2, n | 24 | 21 | 3 | |

| AST, U/L | 71.2 (37.6-128.8) | 78.3 (41.9-131.2) | 36.9 (30.0-126.3) | 0.048 |

| ALT, U/L | 70.1 (40.9-118.2) | 76.8 (45.3-126.0) | 42.7 (32.3-107.6) | 0.065 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 96.5 (76.7-134.0) | 100.1 (77.1-133.2) | 89.1 (76.7-134.6) | 0.577 |

| Missing (creatinine), n | 15 | 15 | 0 | |

| INR | 1.3 (1.2-1.4) | 1.3 (1.2-1.4) | 1.3 (1.2-1.5) | 0.332 |

| Missing (INR)2, n | 17 | 17 | 0 | |

| Imaging characteristics | ||||

| Abscess size, mm | 65.0 (53.0-87.0) | 65.0 (52.0-87.0) | 69.0 (55.0-91.0) | 0.401 |

| Number of abscesses | > 0.999 | |||

| 1 | 84 (79.2) | 65 (78.3) | 19 (82.6) | |

| 2 | 13 (12.3) | 10 (12.1) | 3 (13.0) | |

| 3 | 6 (5.7) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (4.4) | |

| ≥ 4 | 3 (2.8) | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Abscess location | 0.305 | |||

| Left lobe | 31 (29.2) | 23 (27.7) | 8 (34.8) | |

| Right lobe | 60 (56.6) | 46 (55.4) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Bilateral | 15 (14.2) | 14 (16.9) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Multiplicity | 0.777 | |||

| Single | 84 (79.2) | 65 (78.3) | 19 (82.6) | |

| Multiple | 22 (20.8) | 18 (21.7) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Perilesional enhancement | 65 (61.3) | 52 (62.7) | 13 (56.5) | 0.593 |

| Abscess margin | 0.038 | |||

| Smooth | 7 (6.6) | 3 (3.6) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Irregular | 99 (93.4) | 80 (96.4) | 19 (82.6) | |

| Abscess homogeneity | 0.003 | |||

| Homogeneous | 18 (17.0) | 9 (10.8) | 9 (39.1) | |

| Heterogeneous | 88 (83.0) | 74 (89.2) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Intralesional gas | 12 (11.3) | 10 (12.0) | 2 (8.7) | > 0.999 |

| Biliary gas | 8 (7.5) | 7 (8.4) | 1 (4.3) | > 0.999 |

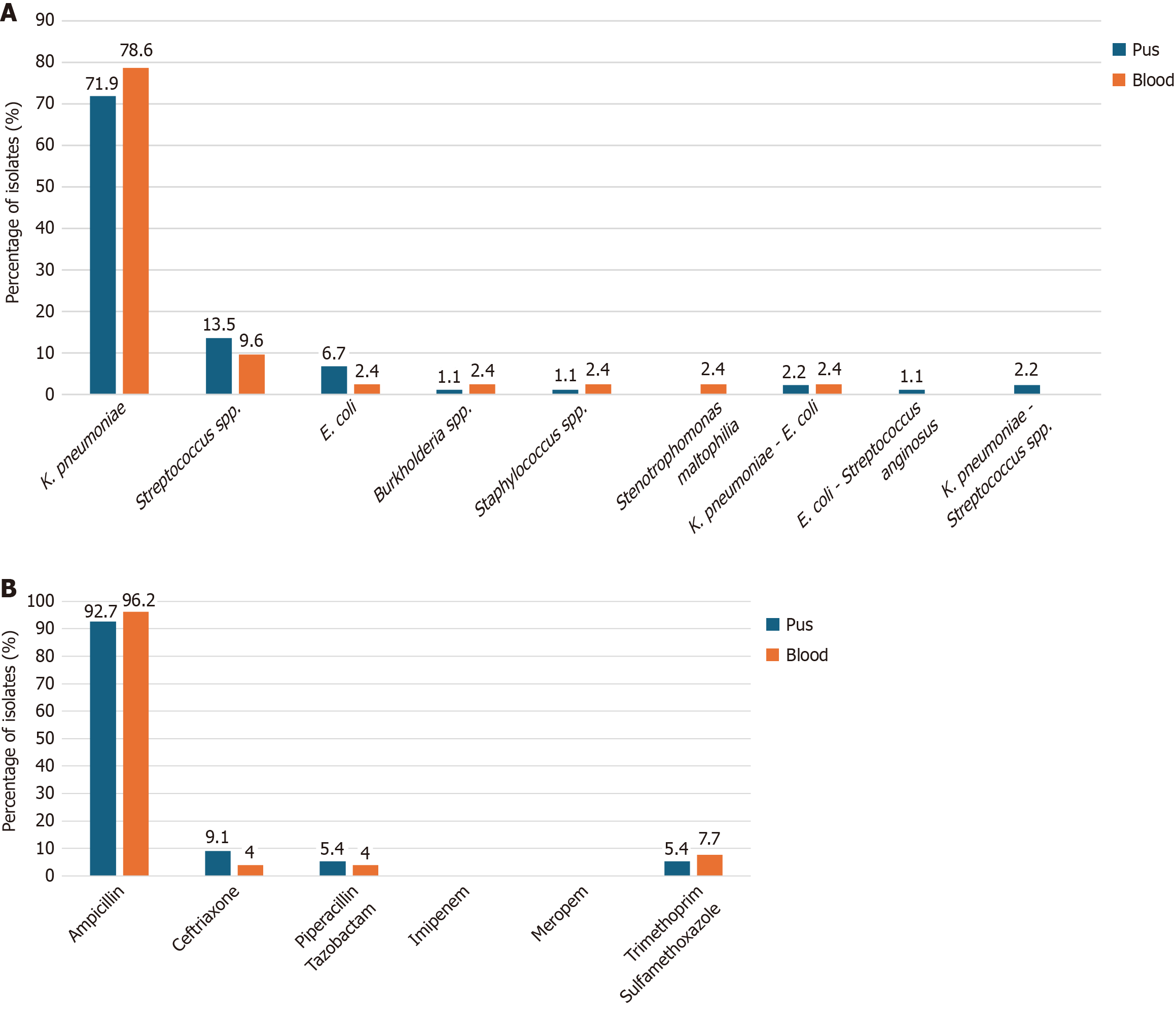

Among pus isolates (n = 89), K. pneumoniae accounted for 64/89 (71.9%), followed by Streptococcus species (aggregated across species) at 12/89 (13.5%) and E. coli at 6/89 (6.7%); mixed K. pneumoniae-E. coli accounted for 2/89 (2.2%), and each remaining single organism represented ≤ 1.1% of isolates. In blood isolates (n = 42), K. pneumoniae predominated (33/42, 78.6%), streptococci collectively accounted for 2/42 (4.8%), and each remaining single or mixed organism represented 1/42 (2.4%). The overall distribution of bacterial isolates is shown in Figure 2A. Antibiotic resistance rates of K. pneumoniae from both pus (n = 55) and blood (n = 26) isolates are presented in Figure 2B. All values refer to isolates rather than unique patients; blood cultures were performed per institutional policy as described in the methods section.

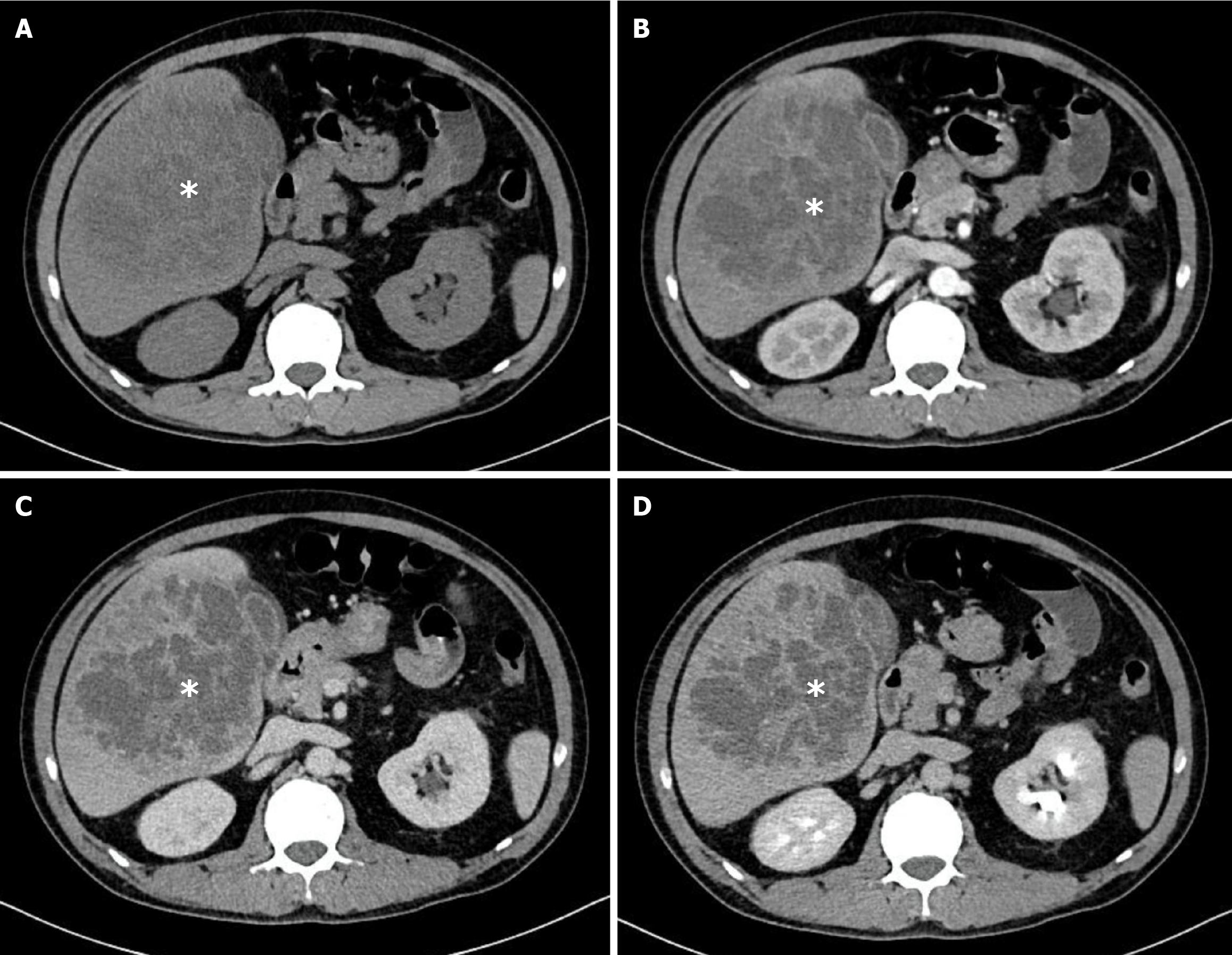

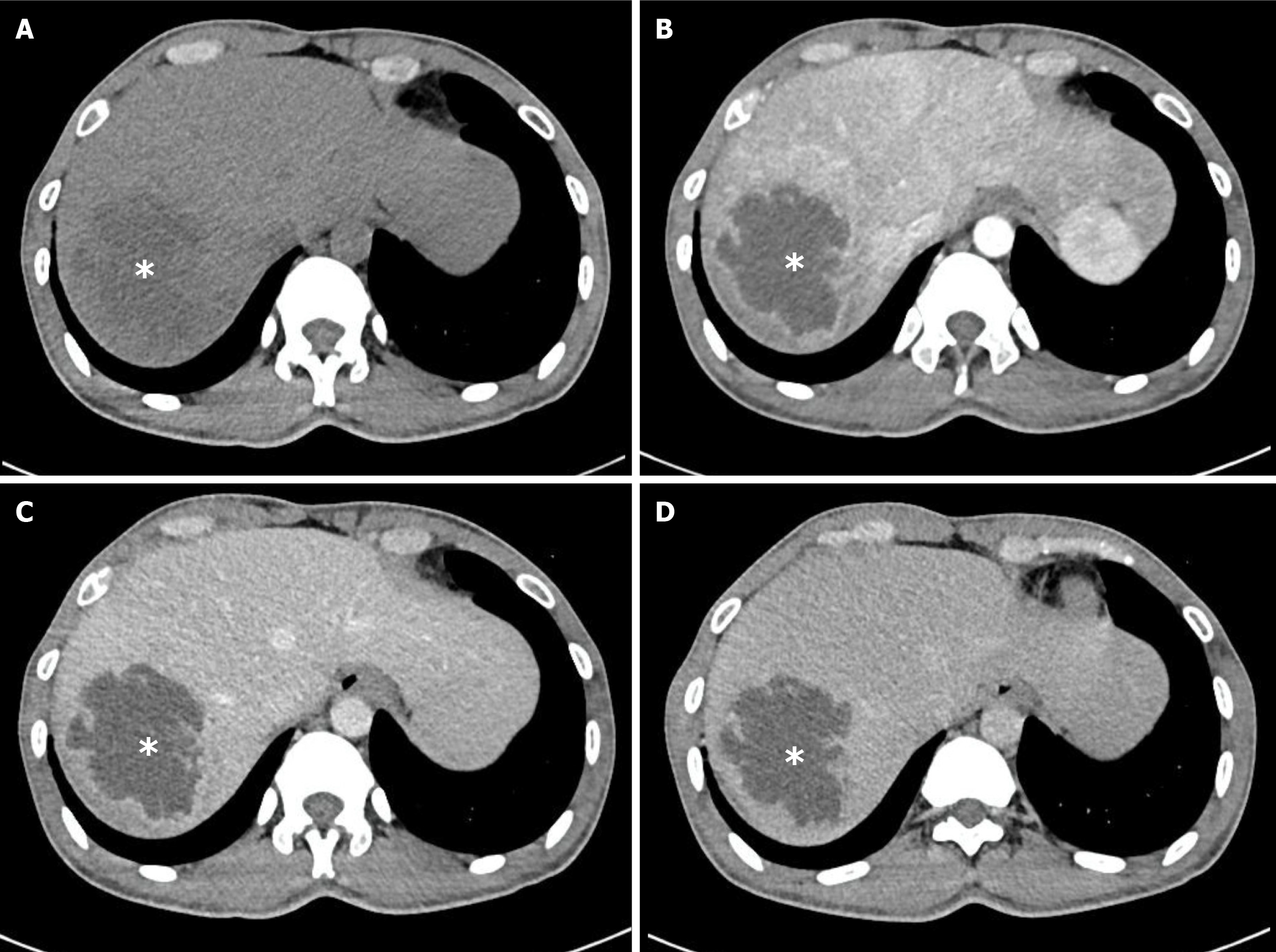

The median maximal abscess diameter at baseline was 65 mm and did not differ significantly between groups (P = 0.401). Most patients presented with solitary abscesses (84/106, 79.2%), while multiple lesions were observed in 22/106 (20.8%; P = 0.777). The right hepatic lobe was the most common location (60/106, 56.6%), followed by the left lobe (31/106, 29.2%) and bilateral involvement (15/106, 14.2%; P = 0.305). Two qualitative imaging features were significantly more frequent in the K. pneumoniae group: Irregular or lobulated margins (80/83, 96.4% vs 19/23, 82.6%; P = 0.038) and heterogeneous internal architecture (74/83, 89.2% vs 14/23, 60.9%; P = 0.003). The presence of intralesional gas, biliary gas, or portal venous gas was uncommon and showed no between-group differences. These findings are summarized in Table 2. Representative examples of K. pneumoniae abscesses with irregular and heterogeneous appearance are shown in Figure 3. In contrast, Figure 4 illustrates a case of PLA caused by Streptococcus species, which displayed slightly irregular margins but a homogeneous, non-septate internal architecture with rim enhancement, underscoring the radiological differences between K. pneumoniae and non-K. pneumoniae etiologies.

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 106) | K. pneumoniae (n = 83) | Non-K. pneumoniae (n = 23) | P value1 |

| Management during index admission | ||||

| Drainage at admission | 41 (38.7) | 32 (38.6) | 9 (39.1) | 0.960 |

| Drainage after medical therapy | 44 (41.5) | 33 (39.8) | 11 (47.8) | 0.487 |

| Surgery at admission | 4 (3.8) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (4.3) | > 0.999 |

| Surgery after medical therapy | 4 (3.8) | 4 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0.575 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| LOS (days) | 9.0 (6.0-14.0) | 10.0 (6.0-15.0) | 8.0 (6.0-12.0) | 0.324 |

| In-hospital mortality | 11 (10.4) | 11 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 0.116 |

In this three-year cohort, K. pneumoniae emerged as the predominant cause of PLA in Southern Vietnam, accounting for nearly four out of five culture-confirmed cases. This observation aligns with the epidemiological shift reported across East and Southeast Asia, where K. pneumoniae has overtaken E. coli as the leading pathogen, contrasting with the predominance of E. coli in Western cohorts[9-11]. Reports from Taiwan and China established this shift more than a decade ago and highlighted the clinical salience of hypervirulent lineages capable of metastatic complications in otherwise healthy hosts[12-14]. Recent Vietnamese series reported similar organism distributions, supporting the notion that K. pneumoniae now accounts for a substantial share of PLA across the country[15]. The predominance of K. pneumoniae has important clinical implications: It shapes empirical antibiotic choices, highlights the need for early recognition of invasive disease phenotypes, and underscores regional differences in microbial epidemiology. Our study therefore contributes locally relevant data to the global understanding of PLA and provides a framework for tailoring management strategies in Vietnam.

The association between K. pneumoniae and diabetes observed here is biologically plausible. Hyperglycemia impairs neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and intracellular killing, and experimental data suggest that host susceptibility interacts with capsular and siderophore determinants that characterize hypervirulent K. pneumoniae[16]. Clinical reviews and mechanistic studies describe a pathotype that preferentially causes communityacquired disease, often with hematogenous seeding of the eye and central nervous system. The epidemiology remains most prominent along the Asian Pacific Rim but is now reported globally. Clinicians in K. pneumoniae-predominant settings should therefore maintain a low threshold to evaluate for metastatic infection when bacteremia persists or focal symptoms arise[16,17]. Pulmonary involvement was also observed in a substantial subset of patients, but its prevalence did not differ between K. pneumoniae and non-K. pneumoniae PLA. While pulmonary complications such as septic emboli and pneumonia are well recognized in invasive K. pneumoniae infections, our findings suggest that concomitant pulmonary disease is not specific to K. pneumoniae and should be systematically assessed in all PLA patients[4,10,18]. Serum creatinine and INR were analyzed as markers of systemic severity rather than pathogen specificity. Creatinine reflects renal impairment from sepsis or comorbidities, while INR indicates coagulation and hepatic dysfunction that may affect drainage risks. Although no significant differences were found, including these variables provides a more complete clinical profile of PLA patients.

The radiologic observations in this cohort have practical implications. Heterogeneous internal architecture and lobulated or illdefined margins on CT likely reflect multi-loculation, necrotic debris, and viscosity gradients that can defeat singlepass aspiration. Contemporary imaging reviews and multidetector CT-based studies emphasize that morphology informs drainability and that early catheter placement should be considered when collections are large, complex, or nonliquefied[19,20]. In parallel, randomized and pooled evidence indicates that percutaneous catheter drainage provides higher clinical success and faster clinical improvement than needle aspiration for many patients with PLA[21]. These considerations align with an interventional strategy that favors early catheter drainage or planned repeat aspirations when K. pneumoniae abscesses present with the complex morphology described here[22]. The presence of gas within a liver abscess on CT is a common feature that may fluctuate depending on the timing of imaging relative to the disease course[23]. In our cohort, however, all patients underwent multislice CT imaging at the time of admission using standardized dynamic contrast-enhanced protocols. As such, variation in gas appearance over the natural course of disease could not be evaluated. This represents a limitation of our study, as we were unable to assess temporal changes in gas formation. Prospective studies with serial CT follow-up could better clarify the evolution of intralesional gas in PLA.

Our organism pattern dovetails with the Asia-Pacific literature, yet it contrasts with several European cohorts in which Enterobacterales remain common but K. pneumoniae is less dominant and enterococci are proportionally more frequent. In a recent German tertiarycare series, positive blood cultures and growth of Enterobacterales were each associated with higher 30-day mortality, underscoring that microbiology and bacteremia status carry prognostic information independent of geography[24]. Populationbased data from Canada also linked poorer outcomes to polymicrobial bacteremia and to absence of drainage[25]. These external data help reconcile our finding of numerically higher mortality limited to K. pneumoniae cases, despite the metaanalytic observation that K. pneumoniae-PLA can have lower crude mortality than non-K. pneumoniae-PLA at the global level; case mix, source control strategy, and comorbidity likely explain some of the heterogeneity[26].

Therapeutic implications follow. Empirical regimens in K. pneumoniae-predominant regions should ensure early, adequate Gram-negative coverage active against K. pneumoniae while preserving anaerobic activity where biliary pa

Several cautions apply when interpreting these results. The retrospective singlecenter design constrains causal inference and limits generalizability. Culture practices that favored blood cultures in patients with persistent fever may have introduced ascertainment bias in the comparison of bloodstream isolates. Missingness in laboratory variables reduced power for betweengroup differences. We did not perform capsular typing or assess hypervirulence markers such as regulator of mucoid phenotype A/regulator of mucoid phenotype A2 or aerobactin, so any inference about hyper

Priorities for Vietnam include multicenter surveillance using standardized indications for blood culture, harmonized definitions for radiologic features, and organism characterization that incorporates capsular typing and hypervirulence markers. Given the imaging phenotype observed here, pragmatic trials or registries that compare initial needle aspiration with upfront catheter drainage in complex collections would be valuable, with stratification by suspected organism at presentation. Antimicrobial stewardship programs should integrate local susceptibility patterns while preserving early broad coverage for highrisk presentations. The accumulating regional literature, including Vietnam-based cohorts, provides a foundation for such efforts and should inform guideline development tailored to K. pneumoniae-predominant settings[15,29].

In a K. pneumoniae-predominant setting, patients with PLA displayed a characteristic clinical-radiologic profile and a mortality signal concentrated in the K. pneumoniae group. These data, generated from Southern Vietnam, corroborate the regional shift toward K. pneumoniae as the leading etiology and support early organism-focused management pathways that integrate prompt, tailored source control with appropriate empirical antimicrobial coverage.

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Department of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary at Nhan Dan Gia Dinh Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam for providing invaluable support throughout the study. We are deeply grateful to all patients and their families whose medical data contributed to this research. Without their cooperation, this study could not have been conducted.

| 1. | Meddings L, Myers RP, Hubbard J, Shaheen AA, Laupland KB, Dixon E, Coffin C, Kaplan GG. A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Svensson E, Jönsson A, Bläckberg A, Sunnerhagen T, Kiasat A, Ljungquist O. Increasing incidence of pyogenic liver abscess in Southern Sweden: a population-based study from 2011 to 2020. Infect Dis (Lond). 2023;55:375-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1032-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yin D, Ji C, Zhang S, Wang J, Lu Z, Song X, Jiang H, Lau WY, Liu L. Clinical characteristics and management of 1572 patients with pyogenic liver abscess: A 12-year retrospective study. Liver Int. 2021;41:810-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, Holzman RS. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1654-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chang SC, Fang CT, Hsueh PR, Chen YC, Luh KT. Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing liver abscess in Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;37:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kocsis B. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: An update on epidemiology, detection and antibiotic resistance. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2023;70:278-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schmoldt A, Benthe HF, Haberland G. Digitoxin metabolism by rat liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1975;24:1639-1641. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lin Y, Chen Y, Lu W, Zhang Y, Wu R, Du Z. Clinical characteristics of pyogenic liver abscess with and without biliary surgery history: a retrospective single-center experience. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24:479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Du ZQ, Zhang LN, Lu Q, Ren YF, Lv Y, Liu XM, Zhang XF. Clinical Charateristics and Outcome of Pyogenic Liver Abscess with Different Size: 15-Year Experience from a Single Center. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nie S, Lin D, Li X. Clinical characteristics and management of 106 patients with pyogenic liver abscess in a traditional Chinese hospital. Front Surg. 2022;9:1041746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tsai FC, Huang YT, Chang LY, Wang JT. Pyogenic liver abscess as endemic disease, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1592-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Qian Y, Wong CC, Lai S, Chen H, He X, Sun L, Wu J, Zhou J, Yu J, Liu W, Zhou D, Si J. A retrospective study of pyogenic liver abscess focusing on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen in China from 1994 to 2015. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 644] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Huynh TL, Nguyen MK. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of liver abscess patients at Nguyen Tri Phuong Hospital. Vietnam Med J. 2023;532:130-138. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Choby JE, Howard-Anderson J, Weiss DS. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae - clinical and molecular perspectives. J Intern Med. 2020;287:283-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 79.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Russo TA, Marr CM. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32:e00001-e00019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 122.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Chang Z. The Incidence of Septic Pulmonary Embolism in Patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae Liver Abscess: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2022;2022:3777122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bächler P, Baladron MJ, Menias C, Beddings I, Loch R, Zalaquett E, Vargas M, Connolly S, Bhalla S, Huete Á. Multimodality Imaging of Liver Infections: Differential Diagnosis and Potential Pitfalls. Radiographics. 2016;36:1001-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liao WI, Tsai SH, Yu CY, Huang GS, Lin YY, Hsu CW, Hsu HH, Chang WC. Pyogenic liver abscess treated by percutaneous catheter drainage: MDCT measurement for treatment outcome. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:609-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lin JW, Chen CT, Hsieh MS, Lee IH, Yen DH, Cheng HM, Hsu TF. Percutaneous catheter drainage versus percutaneous needle aspiration for liver abscess: a systematic review, meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e072736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mahmoud A, Abuelazm M, Ahmed AAS, Elshinawy M, Abdelwahab OA, Abdalshafy H, Abdelazeem B. Percutaneous catheter drainage versus needle aspiration for liver abscess management: an updated systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Ann Transl Med. 2023;11:190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Thng CB, Tan YP, Shelat VG. Gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess: A world review. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2018;22:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wendt S, Bačák M, Petroff D, Lippmann N, Blank V, Seehofer D, Zimmermann L, Lübbert C, Karlas T. Clinical management, pathogen spectrum and outcomes in patients with pyogenic liver abscess in a German tertiary-care hospital. Sci Rep. 2024;14:12972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Losie JA, Lam JC, Gregson DB, Parkins MD. Epidemiology and risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess in the Calgary Health Zone revisited: a population-based study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chan KS, Chia CTW, Shelat VG. Demographics, Radiological Findings, and Clinical Outcomes of Klebsiella pneumonia vs. Non-Klebsiella pneumoniae Pyogenic Liver Abscess: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis. Pathogens. 2022;11:976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lardière-Deguelte S, Ragot E, Amroun K, Piardi T, Dokmak S, Bruno O, Appere F, Sibert A, Hoeffel C, Sommacale D, Kianmanesh R. Hepatic abscess: Diagnosis and management. J Visc Surg. 2015;152:231-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nguyen LC, Pham TT, Luu DT, Nguyen TN, Nguyen NM, Pham HN, Doan HT, Nguyen ST, Nguyen HV. A retrospective study of endogenous endophthalmitis-related pyogenic liver abscess: An increasing complication in North Vietnam. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121231218897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nguyen CL, Vu TK, Tran VS, Nguyen NT, TVN Pham, Nguyen TBA, Dinh DL, Le NT. Management of 96 Patients with Pyogenic Liver Abscess Admitted to a Single Hospital in Hanoi City, Vietnam, 2015-2020: Etiology, Drug Resistance, Complications, and the Outcomes. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2022;42:33922-33927. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Serraino C, Elia C, Bracco C, Rinaldi G, Pomero F, Silvestri A, Melchio R, Fenoglio LM. Characteristics and management of pyogenic liver abscess: A European experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/