Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.111722

Revised: August 29, 2025

Accepted: November 24, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 203 Days and 23.8 Hours

The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score helps assess the severity of liver disease and can predict survival after liver transplant. The Charlson com

To understand the prevalence of extrahepatic comorbidities in our cohort of LDLT patients with modified CCI (mCCI) and to analyze the utility of mCCI as a predi

After obtaining institutional ethics committee approval, a retrospective analysis was conducted on 497 adult patients who underwent LDLT at our institute between January 2021 and December 2023.

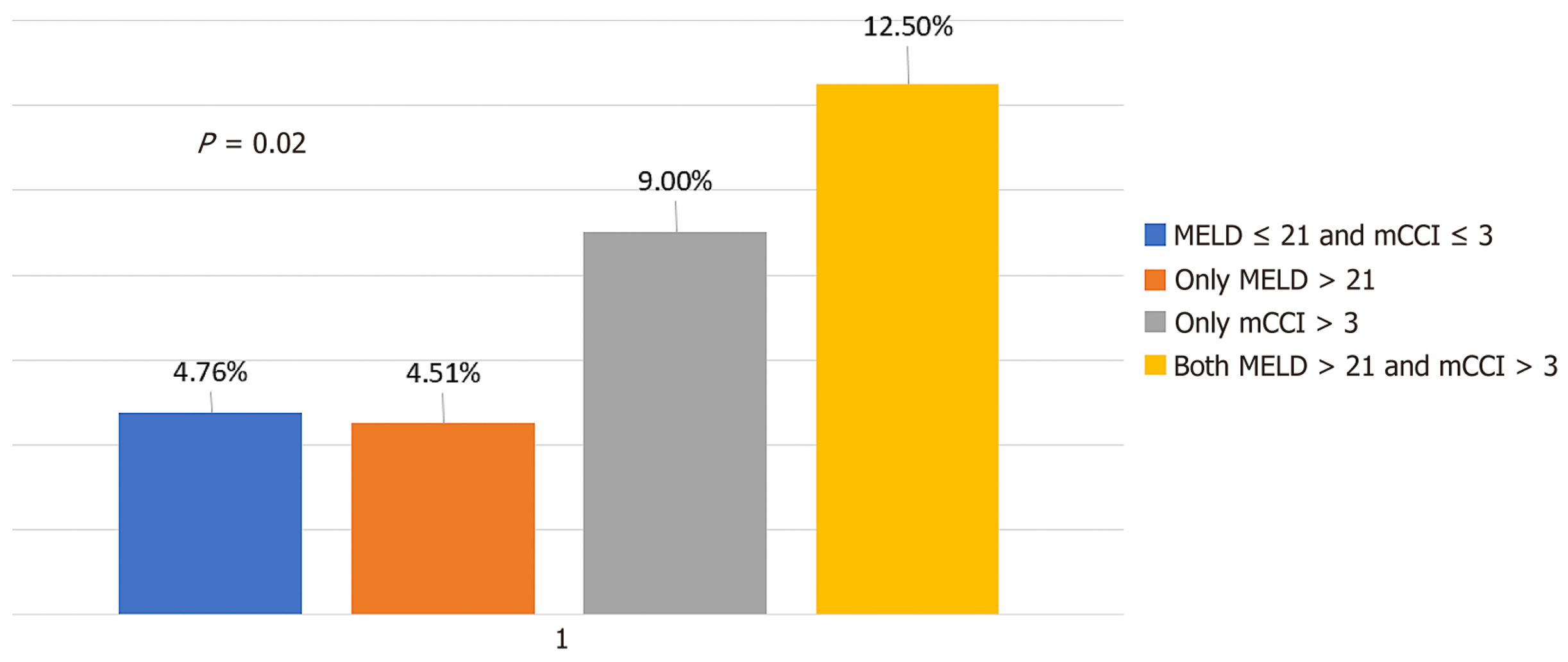

Our analysis revealed that the area under the curve (AUC) of the original CCI for predicting 90-day mortality decreased when malignancy was assigned a score of 2 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transplantation. Therefore, we used a mCCI. Both MELD and mCCI scores demonstrated predictive value for 90-day mortality, with AUCs of 0.60 and 0.62, respectively. Using regression coefficients, we developed a composite score defined as: Combined score = [mCCI + (MELD/10)]. This composite metric improved predictive accuracy, yielding an AUC of 0.70 for 90-day mortality prediction. Patients with a CCI > 3 and a MELD > 21 had a signifi

The mCCI was independent of decompensation and overall disease severity. Combining MELD and CCI scores en

Core Tip: With advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care, the outcomes of liver transplantation have improved significantly, encouraging its use in more elderly patients and those with more comorbidities. In addition to liver disease severity, understanding the impact of extra-hepatic comorbidities on the outcomes will help in prognostication and risk stratification with appropriate resource planning. The Charlson comorbidity index has been validated as a good predictor of long-term survival in varied clinical populations. With limited studies regarding its use in liver transplant patients, we aimed to study its applicability in a cohort of living donor liver transplant patients.

- Citation: Rajan G, Sam AF, Rajakumar A, Jothimani D, Rela M. Application of modified Charlson comorbidity index for predicting outcomes following adult living donor liver transplantation. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 111722

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/111722.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.111722

Liver transplantation (LT) is a definitive therapeutic intervention for patients with end-stage liver disease. With ongoing advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care, outcomes after LT have improved significantly over the decades, supporting its use in older patients and those with more substantial comorbidities[1,2]. Nevertheless, LT is frequently associated with several significant complications, such as postoperative infections, renal dysfunction and extended need for organ support[3].

In addition to assessing the severity and waitlist mortality of patients with liver disease, the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score also predicts survival after LT[4,5]. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) has been commonly used to predict 10-year survival in patients with multiple comorbidities and different clinical populations[6,7]. To expand its utility in LT patients, we recalibrated CCI to generate a modified CCI (mCCI), termed CCI-orthotopic LT, which was found to be a good predictor of post-LT outcomes[8,9]. Here, we analyze the utility of CCI in predicting post-LT outcom

The aim of this study was to understand the prevalence of extrahepatic comorbidities in a cohort of living donor LT (LDLT) patients with CCI and analyze the utility of mCCI as a predictor of morbidity and mortality following LDLT.

This is a retrospective, single center study of a prospectively collected database. Following approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee, all adult patients who underwent LDLT at our institute between January 2021 and December 2023 were included. As it was a retrospective study, informed consent was waived by the Institutional Ethics Committee (No. ECR/1276/Inst/TN/2019/2025/312). Demographic and clinical data were collected from the electronic database. Exclusion criteria included patients who underwent combined solid organ transplantation or LT for acute liver failure, and pediatric LDLT. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Declaration of Istanbul.

Variables such as patient age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), etiological factors, comorbidities, and perioperative complications were assessed and analyzed. A history of admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) at our institution or other hospitals for non-surgical reasons within the 60-day period preceding transplantation was classified as recent ICU admission prior to transplantation. At our center, ICU admission prior to transplantation for patients with nonsurgical liver disease was determined based on the Modified Early Warning Score[10]. The CCI score was calculated using https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3917/charlson-comorbidity-index-cci. The CCI scoring system is presented in Supplementary Table 1. Because assigning a score for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the context of underlying liver disease could introduce confounding variables, that component was not included. A liver disease score of 1 was assigned to patients with HCC, and all other patients received a score of 3 for the liver component of CCI.

Intraoperative parameters assessed included cold ischemia time (CIT), warm ischemia time, blood transfusion, graft-to-recipient weight ratio, crystalloids, higher blood transfusion, need for vasopressors for more than 12 hours after arrival to ICU, duration of surgery, and post-reperfusion syndrome (PRS). The PRS definition by Aggarwal et al[11] was used in this study. Higher blood transfusion was classified as administration of ≥ 6 units of whole blood or packed red blood cells (PRBCs) within 24 hours. PRBCs were transfused to achieve a hemoglobin level of 8-9 g/dL. Other blood products were transfused according to clinical situation and thromoboelastometric findings. Crystalloids and colloids were administered according to pulse pressure variations and clinical situation according to the care provider’s decision. A second vas

Postoperative morbidity was evaluated using the Clavien-Dindo classification (CDC) and was included as morbidity in the study for grade ≥ 3b[12]. Acute kidney injury was defined according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines[13]. Non-pulmonary sepsis was diagnosed if there was a ≥ 2 increase in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score[14]. Chest infection was diagnosed in patients with new infiltrates on lung imaging, cough, dyspnea, and at least two of the following three clinical features: (1) Fever > 38 °C; (2) Leukocytosis or leukopenia; and (3) Purulent secretions[15]. Early graft dysfunction was defined according to Olthoff et al’s criteria: (1) Bilirubin ≥ 10 mg/dL on postoperative day 7; (2) International normalized ratio ≥ 1.6 on day 7; and (3) Alanine or aspartate aminotransferase > 2000 IU/L within the first 7 days[16]. Prolonged mechanical ventilation was defined as the necessity for invasive me

Continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR), whereas categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. Correlations between continuous variables were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The predictive capability of mCCI was assessed through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, from which the optimal point on the ROC curve was determined, facilitating the classification of the study population into two groups: (1) Low mCCI; and (2) High mCCI. Independent predictors of the outcome of interest were identified using a binary logistic regression analysis. Regression coefficients derived from binary regression analysis were utilized to integrate the scores. Variables with P value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using MedCalc for Windows, version 23.0.2 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

A total of 497 patients were included in the analysis. Our cohort had a median age of 52 years (IQR: 45, 59) and predominantly male sex [409 (82.3%)]. The median immediate preoperative MELD score was 17 (IQR: 13, 22). Metabolic dys

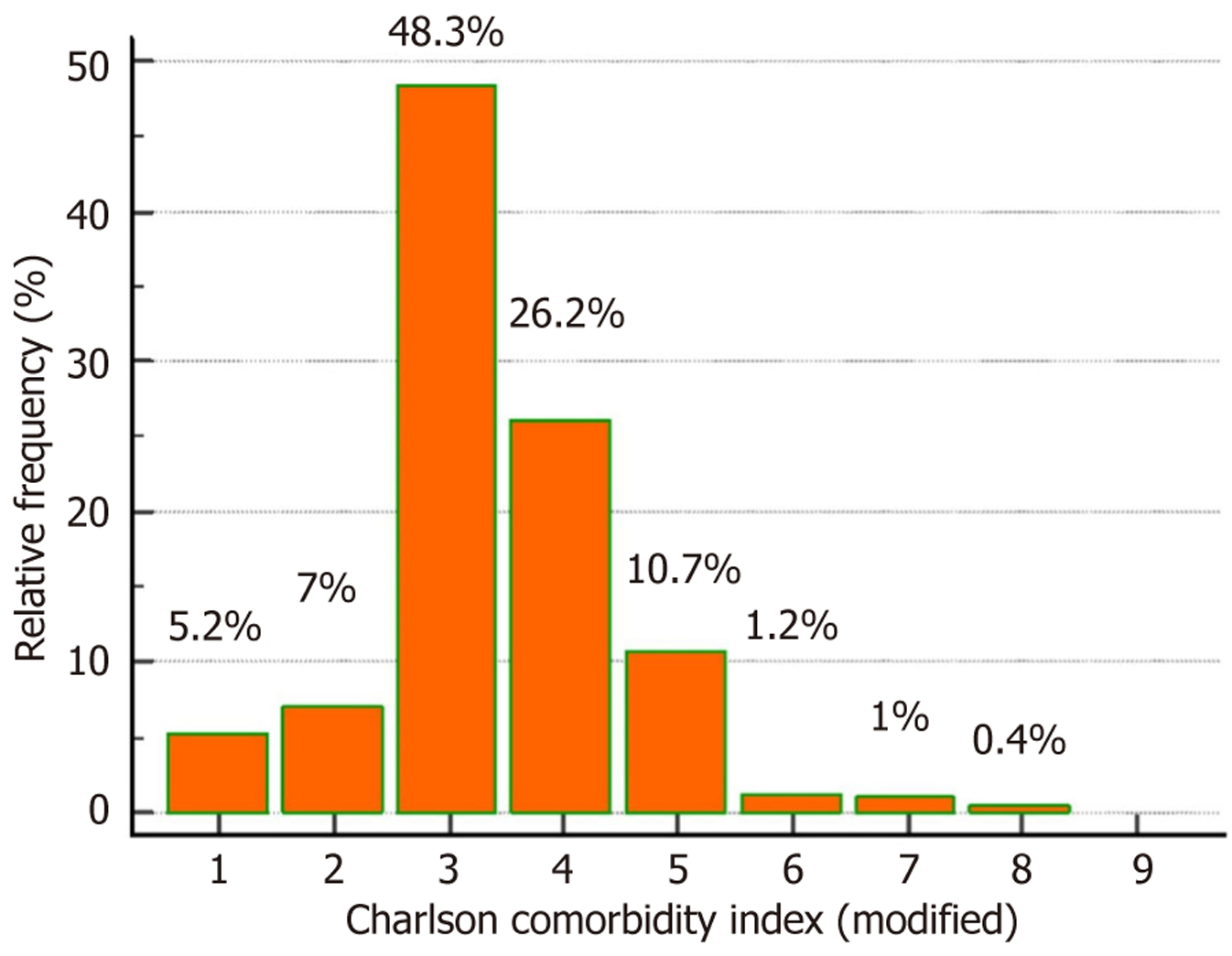

In our study group, 26 (5.2%) patients had an mCCI score of 1, indicating the presence of compensated liver disease with HCC as an indication for LT. The remaining 68 patients with HCC had decompensations and were assigned a score of 3 in the liver disease domain. Our primary aim was to analyze the prevalence of extrahepatic comorbidities. The distribution of mCCI scores in the study population is presented in Figure 1. Most of these patients fell into the category of mCCI = 3 [240 (48.3%)], followed by 130 (26.2%) patients with mCCI = 4, 53 (10.7%) with a score of 5, 6 (1.2%) with a score of 6, and 7 (1.4%) with a score of ≥ 7. The optimal point from Youden’s index of the ROC curve was used to classify the study population into two groups. Patients with an mCCI score ≤ 3 were classified into the low mCCI group and > 3 into the high mCCI group.

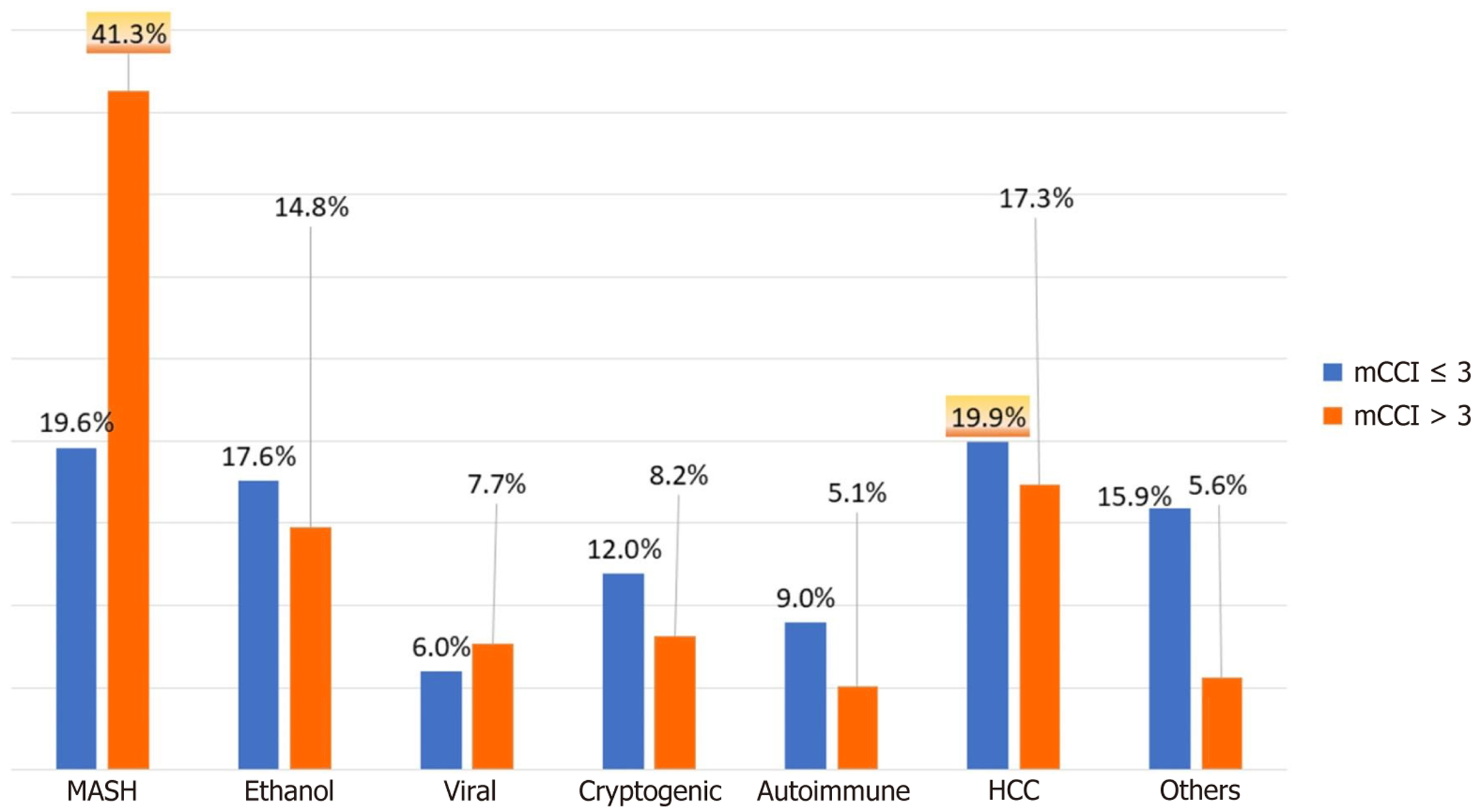

The demographic characteristics and preoperative comorbidities of the patients are shown in Table 1. The median ages of the patients in the low and high mCCI groups were 49 (42, 57) years and 57 (50, 61) years, respectively (P < 0.001). The study cohort consisted predominantly of male patients (82.2%). The distribution of ethnicity between the two groups was comparable. The prevalence of MASLD as an etiology was significantly higher in the high mCCI group (41% vs 19.6%; P < 0.001). Conversely, the low mCCI group had a higher proportion of patients with HCC as the etiology (19.9% vs 17.3%; P < 0.001; Figure 2). The median MELD scores were 16 and 18 in the low and high mCCI groups, respectively (P = 0.01). The prevalence of associated comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and the incidence of acute kidney injury was higher (88.7%, 33.2%, 10.1%, and 48.9%, respectively) in the high mCCI group than in the low mCCI group (14.2%, 18.6%, 0%, and 33.1%, respectively; all P < 0.001). The occurrence of decompensation, such as spon

| Variables | mCCI ≤ 3 (n = 301) | mCCI > 3 (n = 196) | P value | |

| Age (years) (IQR) | 49 (42, 57) | 57 (50, 61) | < 0.001 | |

| Sex, male | 252 (83.7) | 157 (80.1) | 0.30 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (IQR) | 26 (22.8, 29.7) | 27 (23.2, 30) | 0.46 | |

| Model for end-stage liver disease (IQR) | 16 (11, 22) | 18 (15, 21) | 0.01 | |

| Geographical distribution | Indian | 191 (63.4) | 128 (65.3) | 0.58 |

| Middle East and Egypt | 57 (18.9) | 26 (13.2) | ||

| Asia (other than India) | 26 (8.6) | 23 (11.7) | ||

| North Africans | 10 (3.3) | 6 (3.0) | ||

| Others | 17 (5.6) | 13 (6.6) | ||

| Etiology | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis | 59 (19.6) | 81 (41.3) | < 0.001 |

| Ethanol related | 53 (17.6) | 29 (14.8) | ||

| Viral | 18 (6) | 15 (7.7) | ||

| Cryptogenic | 36 (12) | 16 (8.2) | ||

| Autoimmune | 27 (9) | 10 (5.1) | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 60 (19.9) | 34 (17.3) | ||

| Others | 48 (15.9) | 11 (5.6) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 43 (14.2) | 174 (88.7) | < 0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 56 (18.6) | 65 (33.1) | < 0.001 | |

| Acute kidney injury | 100 (33.2) | 96 (48.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 (0) | 20 (10.2) | < 0.001 | |

| History of preoperative spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 55 (18.2) | 33 (16.8) | 0.68 | |

| History of preoperative intensive care unit stay with 60 days prior to transplant | 97 (32.2) | 75 (38.2) | 0.16 | |

The intraoperative parameters are presented in Table 2. There was no significant difference between the groups in any intraoperative parameter except in the number of intraoperative PRBC received, which was more in high mCCI groups (P < 0.001).

| Intra operative parameters | mCCI ≤ 3 (n = 301) | mCCI > 3 (n = 196) | P value |

| Graft-to-recipient weight ratio | 0.93 (0.78, 1.08) | 0.94 (0.8, 1.12) | 0.37 |

| Intra operative peak lactate (mmol/L) | 4.1 (2.9, 5.6) | 3.6 (2.9, 5.2) | 0.85 |

| Shifting lactates (mmol/L) | 3.4 (2.1, 5) | 3 (2.2, 4.4) | 0.61 |

| Crystalloids intra operative (L) | 2.5 (1.5, 3) | 2.5 (1.5, 3.5) | 0.75 |

| Intra operative packed red blood cells | 3 (1, 5) | 4 (3, 6) | < 0.001 |

| Massive blood transfusion | 51 (16.9) | 45 (22.9) | 0.09 |

| Cold ischemia time (minutes) | 98 (75, 135) | 103 (75, 129) | 0.81 |

| Warm ischemia time (minutes) | 43 (36, 51) | 43 (36, 53) | 0.23 |

| Reperfusion syndrome | 19 (6.3) | 18 (9.1) | 0.23 |

| Surgical duration (minutes) | 540 (438, 578) | 500 (450, 585) | 0.12 |

The postoperative parameters and outcomes are presented in Table 3. The proportion of patients requiring prolonged vasopressor support following surgery was 42.8% and 37.7% in the low and high mCCI groups, respectively (P = 0.25). The incidence of early allograft dysfunction was 9.6% in the low mCCI group and 12.2% in the high mCCI group (P = 0.35). Postoperative complications, including re-exploration, non-pulmonary sepsis, lung infection, postoperative ble

| Postoperative outcomes | mCCI ≤ 3 (n = 301) | mCCI > 3 (n = 196) | P value |

| Prolonged vasopressor support from the end of surgery | 129 (42.8) | 74 (37.7) | 0.25 |

| Early allograft dysfunction | 29 (9.6) | 24 (12.2) | 0.35 |

| Incidence of re-exploration surgery | 36 (11.9) | 26 (13.2) | 0.66 |

| Postoperative renal replacement therapy | 11 (3.6) | 21 (10.7) | 0.002 |

| Incidence of sepsis | 53 (17.5) | 37 (18.8) | 0.71 |

| Incidence of prolonged mechanical ventilation | 22 (7.3) | 27 (13.7) | 0.01 |

| Incidence of lung infections | 61 (20.2) | 39 (19.8) | 0.92 |

| Incidence of cardiac complications | 19 (6.3) | 22 (11.2) | 0.05 |

| Incidence of neurological complications | 20 (6.6) | 29 (14.7) | 0.003 |

| Incidence of wound infection | 18 (5.9) | 22 (11.2) | 0.03 |

| Length of ICU stay (days) (IQR) | 6 (5, 8) | 6 (5, 10) | 0.03 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) (IQR) | 16 (13, 20) | 17 (14, 22) | 0.01 |

| ICU re-admission | 29 (9.6) | 33 (16.5) | 0.01 |

| Morbidity (Clavien-Dindo classification ≥ 3b) | 53 (17.6) | 57 (29) | 0.002 |

| 30-day mortality | 6 (1.9) | 10 (5.1) | 0.06 |

| 90-day mortality | 14 (4.6) | 21 (10.7) | 0.01 |

The high mCCI group exhibited a significantly higher incidence of prolonged mechanical ventilation, wound infection, cardiac complications, neurological complications, and the requirement for postoperative renal replacement therapy than the low mCCI group. The ICU readmission rate was higher in the high mCCI group (16.5%) than in the low mCCI group (9.6%; P = 0.01).

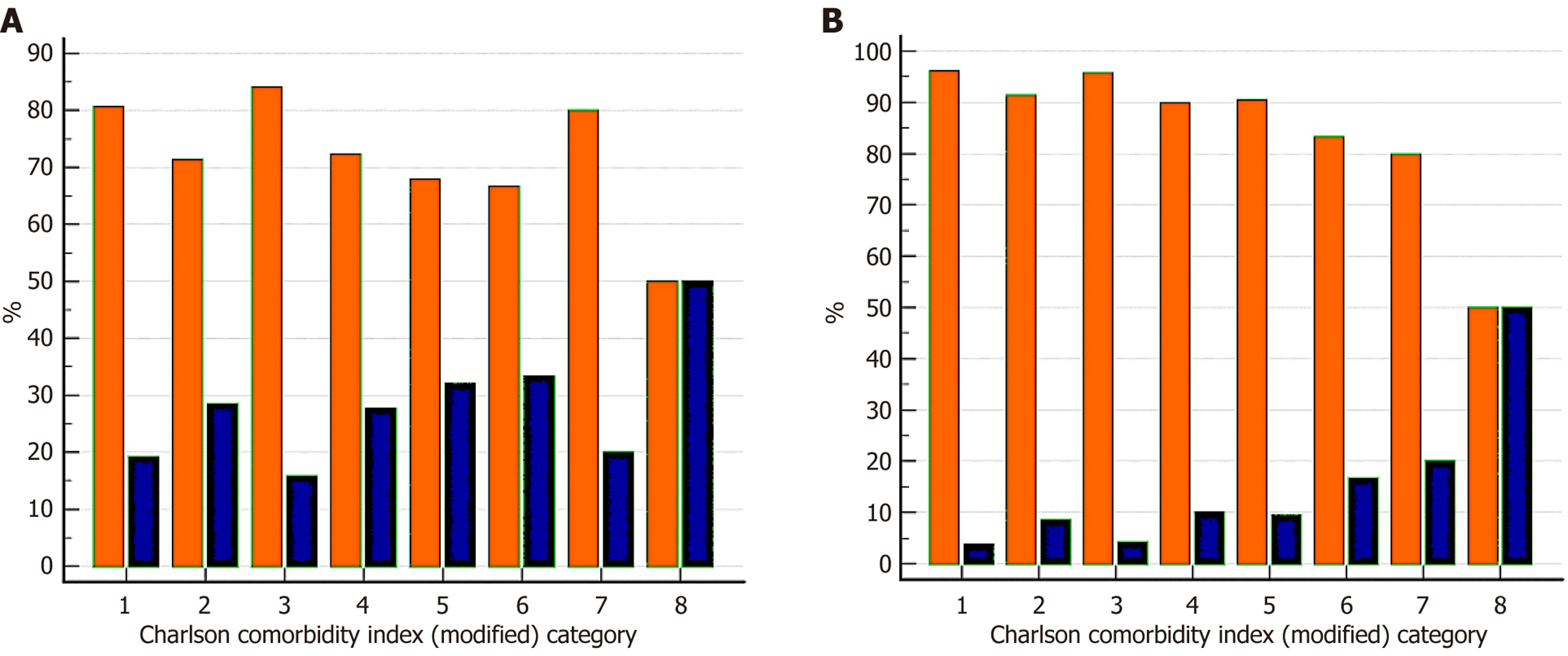

The overall 90-day mortality rate was 7.8% and the morbidity rate was 22.1%. Overall morbidity > grade 3b was higher in the high mCCI group (29%) than in the low mCCI group (17.6%; P = 0.002). The mortality rate at 90 days was higher in the high mCCI group (10.7% vs 4.6%; P = 0.01). Mortality and morbidity for each mCCI score are displayed in Figure 3.

We analyzed the MELD score to determine the severity of liver disease and the mCCI to assess the severity of comorbid conditions and to predict outcomes. We generated a composite score based on the regression coefficients, which was mCCI + (MELD/10). This composite score was used to predict the 90-day mortality and morbidity rates.

The overall 90-day mortality rate was 7.8% in our study population, and the morbidity rate was 22.1%. The MELD, mCCI, and composite score predicted morbidity with area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.51, 0.57, and 0.59, respectively. The MELD and mCCI scores predicted 90-day mortality with AUC values of 0.60 and 0.62, respectively (Table 4). The com

| Preoperative parameter | Postoperative outcome | Area under the curve | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| MELD | CDC ≥ 3b | 0.51 | > 21 | 40 | 73 |

| 90-day mortality | 0.60 | 42 | 74 | ||

| mCCI | CDC ≥ 3b | 0.57 | > 3 | 52 | 65 |

| 90-day mortality | 0.62 | 63 | 49 | ||

| Combination score [mCCI + (MELD/10)] | CDC ≥ 3b | 0.59 | > 5 | 54 | 65 |

| 90-day mortality | 0.70 | 40 | 87 |

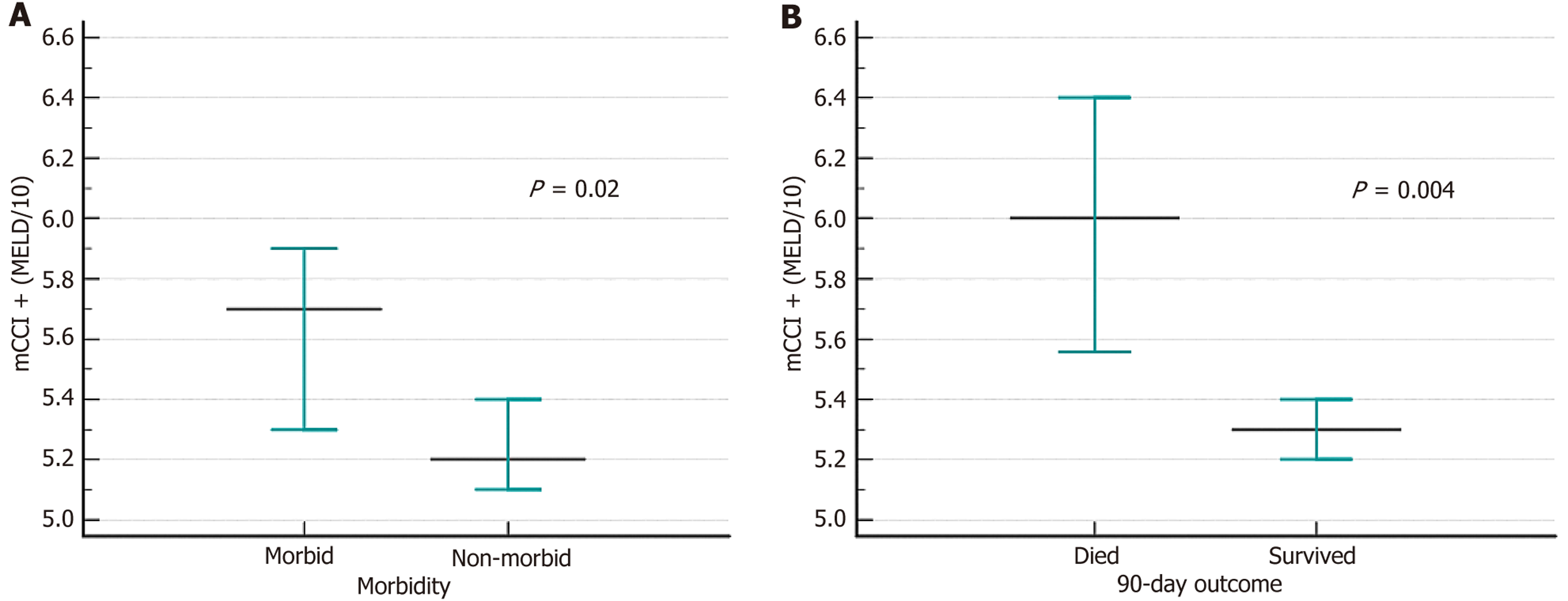

A combined score of > 5 predicted 90-day mortality with a sensitivity of 40% and specificity of 87%. A model is considered effective if the goodness of fit is > 0.5, which is the lower bound of the 95%CI. A goodness of fit below 0.5 indicates that the model is no better than random prediction. The mCCI had a lower bound of 0.50, and the MELD had 0.46 in predicting 90-day mortality, suggesting poor model performance. However, the combination score had a lower bound of 0.64, indicating that the model is effective. As a continuous variable, the composite score was elevated in patients with morbid conditions and in those who died within 90 days (Figure 5).

Owing to the limited number of patients experiencing 90-day mortality, we shifted our focus to morbidity as the primary outcome for regression analysis. Binary logistic regression analysis for morbidity in the univariate context identified several significant factors: (1) Sex (female); (2) mCCI > 3; (3) Diabetes mellitus; (4) Preoperative history of renal rep

| Characteristics of patients | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

| OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | |

| Age | 0.93 | 0.57-1.53 | - | - |

| Sex | 2.12 | 1.28-3.52b | 1.99 | 1.17-3.40a |

| Body mass index | 0.98 | 0.94-1.02 | - | - |

| Smoking | 1.27 | 0.80-2.01 | - | - |

| MELD | 1.02 | 0.66-1.55 | - | - |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.75 | 1.15-2.69b | 0.7 | 0.4-1.5 |

| Insulin dependent diabetes mellitus | 1.85 | 1.14-3.02b | 0.8 | 0.4-1.6 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.33 | 0.82-2.18 | - | - |

| Hypertension | 1.01 | 0.62-1.65 | - | - |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.45 | 0.98-6.16 | - | - |

| Etiology metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis | 0.94 | 0.49-1.8 | - | - |

| Preoperative intensive care unit stay | 1.99 | 1.29-3.07b | 0.7 | 0.5-1.1 |

| Recurrent large volume paracentesis | 2.10 | 1.34-3.29b | 1.66 | 1.03-2.67a |

| Preoperative need of dialysis | 7.64 | 2.56-22.85b | 6.31 | 2.04-19.47b |

| Intraoperative massive blood transfusion | 2.34 | 1.44-3.82b | 2.33 | 1.40-3.88b |

| Graft-to-recipient weight ratio | 0.99 | 0.94-1.04 | - | - |

| mCCI > 3 | 1.92 | 1.25-2.94b | 1.66 | 1.06-2.60a |

| mCCI + MELD/10 | 2.05 | 1.32-3.18b | 0.99 | 0.96-1.01 |

In the current era, LT has shown promising results in patients with end-stage liver disease. The implementation of the MELD score for liver allocation in the United States began in 2002, aiding in prioritizing organ allocation for the sickest patients on the waitlist[17,18]. Recently, to reduce the waitlist duration for transplants, there has been an increased reliance on extended criteria donor liver grafts[19-21]. Survival following a transplant is influenced by factors related to both the donor and the recipient. In addition to predicting the severity of the condition and mortality on the waitlist, the MELD score forecasts survival after liver transplant[22,23]. In addition to examining hepatic markers, we aimed to assess extrahepatic comorbidities independent of LT and their impact on outcomes following LT. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grading system is the most widely used method for evaluating patients based on their com

We evaluated 497 patients in total. Among them, 94 had HCC; 68 of these patients had decompensated liver disease and HCC and were assigned a score of 3. The remaining 26 patients (5.2%), for whom HCC was the indication for LT, were assigned a score of 1 in the liver component of the CCI. Extrahepatic comorbidities significantly affected approximately half of the transplant population, with uncomplicated diabetes being the most common, present in about 40% of patients. Most individuals had an mCCI score of 3, with progressively fewer patients in higher score categories. We evaluated CCI performance using two methods: (1) Applying the original CCI method, which assigns score of 2 for malignancy; and (2) Omitting the additional malignancy score, given that malignancy in LT recipients is associated with better short-term post-transplant outcomes. We refer to this modified version as the mCCI. We found that the AUC of the original CCI was lower when a score of 2 was assigned to malignancy. Thus, we conclude that carcinoma/malignancy, considered a poor-prognosis component in the original CCI score, does not confer the same adverse impact in patients undergoing LT and therefore should not be weighted as such in this population. Consequently, we chose to use the mCCI. We then used the optimal cut-off from Youden’s index of ROC to distinguish patients with higher morbidity and mortality, which was > 3 for mCCI and > 21 for preoperative MELD. We compared the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables between the patients by dividing them into two groups: (1) mCCI > 3 and (2) mCCI ≤ 3.

In our study, patients with a high mCCI were generally older and had a higher incidence of MASLD. This may be attributed to the well-known association between diabetes, a component of metabolic syndrome, and MASLD[26-28]. In our study, the high mCCI group had a higher median MELD score, along with increased incidences of diabetes and acute kidney injury, as well as a greater prevalence of chronic kidney disease. Postoperatively, prolonged mechanical ven

Postoperative cardiac and neurological complications were more prevalent, which we attributed to the higher preoperative incidence of diabetes and the advanced patient age in the high mCCI group. Additionally, the postoperative wound infection rate was elevated in patients with high mCCI, likely due to the increased incidence of preoperative diabetes in this group. Diabetes is recognized as a risk factor not only for traditional complications, such as stroke, coronary heart disease, peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy, but also for complications such as cancer and infections[33]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of diabetes and surgical site infections (SSI), Martin et al[34] found a significant association between diabetes and SSI, which remained consistent across various types of surgeries, even after adjusting for BMI. They also confirmed a link between both preoperative and postoperative hyperglycemia and SSI, as well as a history of diabetes[34].

Owing to the low number of patients experiencing 90-day mortality in our study, we shifted our focus to morbidity as the outcome for regression analysis. We defined morbidity as CDC ≥ 3b, which became our outcome of interest, and conducted binary logistic regression analysis. This analysis identified several independent predictors of morbidity: (1) Sex (female); (2) Preoperative events; (3) Recurrent large-volume paracentesis and the need for dialysis; (4) mCCI > 3; and (5) Higher intraoperative blood transfusion.

We aimed to develop a score that would assign importance to both the hepatic and extrahepatic components. Although MELD was not significant in the univariate binary logistic regression analysis, we included it because the existing literature suggests its association with postoperative morbidity. Preoperative MELD was used as an indicator of liver disease severity and mCCI was used as a marker of extrahepatic comorbidities. To integrate both, we applied a con

Our study was limited by the retrospective nature of the analysis of prospectively collected data. Another limitation was the number of preoperative variables available for analysis. Further research, including comparisons with various comorbidities by propensity score matching, is needed in a prospective manner. Whether the equation of adding 1/10th of the MELD to the mCCI holds should be confirmed with external validation. Despite these limitations, the dataset provided a large representative sample for predicting morbidity and 90-day mortality in patients undergoing LT. This may also be useful in anticipating the risk of perioperative complications and could aid in risk stratification, prognostication and appropriate resource allocation.

Carcinoma, which is a component with a poor outcome in the original CCI score, cannot be extrapolated to liver tran

| 1. | Gómez Gavara C, Esposito F, Gurusamy K, Salloum C, Lahat E, Feray C, Lim C, Azoulay D. Liver transplantation in elderly patients: a systematic review and first meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21:14-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mousa OY, Nguyen JH, Ma Y, Rawal B, Musto KR, Dougherty MK, Shalev JA, Harnois DM. Evolving Role of Liver Transplantation in Elderly Recipients. Liver Transpl. 2019;25:1363-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Agostini C, Buccianti S, Risaliti M, Fortuna L, Tirloni L, Tucci R, Bartolini I, Grazi GL. Complications in Post-Liver Transplant Patients. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Dashti H, Ebrahimi A, Khorasani NR, Moazzami B, Khojasteh F, Shabanan SH, Jafarian A. The utility of early post-liver transplantation model for end-stage liver disease score in prediction of long-term mortality. Ann Gastroenterol. 2019;32:633-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brown C, Aksan N, Muir AJ. MELD-Na Accurately Predicts 6-Month Mortality in Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis: Potential Trigger for Hospice Referral. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:902-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, Patierno C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91:8-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 1076] [Article Influence: 269.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32099] [Cited by in RCA: 39760] [Article Influence: 1019.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Volk ML, Hernandez JC, Lok AS, Marrero JA. Modified Charlson comorbidity index for predicting survival after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1515-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wasilewicz M, Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Wunsch E, Wójcicki M, Milkiewicz P. Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index in predicting early mortality after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3117-3118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gardner-Thorpe J, Love N, Wrightson J, Walsh S, Keeling N. The value of Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) in surgical in-patients: a prospective observational study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:571-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aggarwal S, Kang Y, Freeman JA, Fortunato FL, Pinsky MR. Postreperfusion syndrome: cardiovascular collapse following hepatic reperfusion during liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1987;19:54-55. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6210] [Cited by in RCA: 9243] [Article Influence: 543.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179-c184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1436] [Cited by in RCA: 3722] [Article Influence: 265.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6591] [Cited by in RCA: 8137] [Article Influence: 271.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 15. | Rea-Neto A, Youssef NC, Tuche F, Brunkhorst F, Ranieri VM, Reinhart K, Sakr Y. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care. 2008;12:R56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Olthoff KM, Kulik L, Samstein B, Kaminski M, Abecassis M, Emond J, Shaked A, Christie JD. Validation of a current definition of early allograft dysfunction in liver transplant recipients and analysis of risk factors. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:943-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 679] [Cited by in RCA: 934] [Article Influence: 58.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leventhal TM, Florek E, Chinnakotla S. Changes in liver allocation in United States. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2020;25:52-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, Harper A, Kim R, Kamath P, Kremers W, Lake J, Howard T, Merion RM, Wolfe RA, Krom R; United Network for Organ Sharing Liver Disease Severity Score Committee. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1825] [Cited by in RCA: 1898] [Article Influence: 82.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Nair A, Hashimoto K. Extended criteria donors in liver transplantation-from marginality to mainstream. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2018;7:386-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vodkin I, Kuo A. Extended Criteria Donors in Liver Transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:289-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 21. | Fodor M, Zoller H, Oberhuber R, Sucher R, Seehofer D, Cillo U, Line PD, Tilg H, Schneeberger S. The Need to Update Endpoints and Outcome Analysis in the Rapidly Changing Field of Liver Transplantation. Transplantation. 2022;106:938-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Evans MD, Diaz J, Adamusiak AM, Pruett TL, Kirchner VA, Kandaswamy R, Humphreville VR, Leventhal TM, Grosland JO, Vock DM, Matas AJ, Chinnakotla S. Predictors of Survival After Liver Transplantation in Patients With the Highest Acuity (MELD ≥40). Ann Surg. 2020;272:458-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Habib S, Berk B, Chang CC, Demetris AJ, Fontes P, Dvorchik I, Eghtesad B, Marcos A, Shakil AO. MELD and prediction of post-liver transplantation survival. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:440-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Laor A, Tal S, Guller V, Zbar AP, Mavor E. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) as a Mortality Predictor after Surgery in Elderly Patients. Am Surg. 2016;82:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Varady NH, Gillinov SM, Yeung CM, Rudisill SS, Chen AF. The Charlson and Elixhauser Scores Outperform the American Society of Anesthesiologists Score in Assessing 1-year Mortality Risk After Hip Fracture Surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479:1970-1979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | M I, Singh C, Ganie MA, Alsayari K. NASH: The Hepatic injury of Metabolic syndrome: a brief update. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2009;3:265-270. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Mitrovic B, Gluvic ZM, Obradovic M, Radunovic M, Rizzo M, Banach M, Isenovic ER. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: where do we stand today? Arch Med Sci. 2023;19:884-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Radu F, Potcovaru CG, Salmen T, Filip PV, Pop C, Fierbințeanu-Braticievici C. The Link between NAFLD and Metabolic Syndrome. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lee S, Jung HS, Choi JH, Lee J, Hong SH, Lee SH, Park CS. Perioperative risk factors for prolonged mechanical ventilation after liver transplantation due to acute liver failure. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;65:228-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nafiu OO, Carello K, Lal A, Magee J, Picton P. Factors Associated with Postoperative Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation in Pediatric Liver Transplant Recipients. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2017;2017:3728289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Prasad V, Guerrisi M, Dauri M, Coniglione F, Tisone G, De Carolis E, Cillis A, Canichella A, Toschi N, Heldt T. Prediction of postoperative outcomes using intraoperative hemodynamic monitoring data. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yuan H, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Chawa V, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Axelrod D, Dzebisashvili N, Lentine KL. Prognostic impact of mechanical ventilation after liver transplantation: a national database study. Am J Surg. 2014;208:582-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tomic D, Shaw JE, Magliano DJ. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18:525-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 771] [Cited by in RCA: 612] [Article Influence: 153.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Martin ET, Kaye KS, Knott C, Nguyen H, Santarossa M, Evans R, Bertran E, Jaber L. Diabetes and Risk of Surgical Site Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:88-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/