Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.111534

Revised: August 6, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 209 Days and 18 Hours

Metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, with global prevalence estimated at about 32%. The main predictor of clinical outcome is liver fibrosis severity, mak

Core Tip: Metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease affects approximately 30% of the global population, with a rising prevalence. Although liver biopsy is the gold standard for assessing liver fibrosis and inflammation, it has inherent limitations, leading to the search for noninvasive methods with high reproducibility for evaluating and monitoring patients with metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. This systematic review summarizes key data on the noninvasive methods for assessing liver fibrosis, highlighting their advantages over liver biopsy in terms of accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and patient safety.

- Citation: Ribeiro TCR, de Paula Boechat Soares V, Campos Fabri J, de Aragão Ramos LE. Noninvasive liver fibrosis assessment in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 111534

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/111534.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.111534

Metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has emerged as a leading cause of chronic liver disease (CLD) worldwide. Its global prevalence, initially estimated at approximately 25%, has markedly increased over the past decade, now reaching 32% of the world population and up to 33% in Latin America when the new terminology is applied[1-3]. This upward trend is primarily attributed to the recent epidemic of obesity[4-7]. Currently, MASLD represents the commonest etiology of liver malignancy and liver transplantation among women in the United States, and it is projected to become the primary cause of advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD) worldwide within the next two decades[8]. In 1980, Ludwig et al[9] introduced the term “nonalcoholic steatohepatitis” to describe histological findings similar to those observed in the liver tissue of patients with alcoholic hepatitis but in individuals without a history or clinical evidence of significant alcohol consumption. In 2020, Eslam et al[10] proposed a change in nomenclature to metabolic dysfunction associated with fatty liver disease (MAFLD), aiming to provide a more inclusive and accurate term by removing the exclusive “nonalcoholic” descriptor as well as to emphasize the central role of metabolic stress in disease pathogenesis. Moreover, concerns regarding the stigmatizing nature of the term “fatty” and the requirement to exclude other potential causes (e.g., alcohol consumption) led to an expert consensus panel to review the existing terminology. Currently, the term “steatotic liver disease” (SLD) is the preferred nomenclature to encompass the various etiologies of hepatic steatosis, being endorsed by multiple societies[11]. Therefore, the term MASLD has substituted the previous MAFLD, proposed by Eslam et al[10]. Table 1 summarizes the differences and definitions in terminology used to describe SLD.

| Nomenclature | Definition |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is defined by the presence of ≥ 5% of macrovesicular steatosis and the absence of an identified alternative diagnosis, as well as a significant ongoing or recent alcohol consumption (defined as < 30 g/day for men and < 20 g/day for women) |

| NASH | Presence of inflammation and cellular injury expressed by ballooning |

| MAFLD | Presence of steatosis evidenced by histology, imaging, or blood biomarker in addition to one of the following criteria: Overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or evidence of metabolic syndrome |

| SLD | Presence of steatosis diagnosed histologically or by imaging techniques |

| MASLD | Presence of SLD associated with at least one cardiometabolic risk factor and no other identified cause, alcohol consumption should be less than 20 g/day for women and 30 g/day for men, previously called NAFLD |

| MASH | Presence of MASLD and cellular inflammation and/or injury, previously mentioned as NASH |

| Met-ALD | Met-ALD was recently proposed, defined as the presence of SLD and alcohol consumption between 20-50 g/day in women and 30-60 g/day in men |

Given the limited data specifically addressing the occurrence of SLD compared to nonalcoholic FLD (NAFLD), the possibility of extrapolating findings from studies based on the former definitions of the newly proposed classification has been evaluated. Although SLD appears to be associated with a slightly increased mortality risk, it shares similar clinical profiles and noninvasive test performance characteristics of the former terminology, suggesting the potential interchangeability of these terminologies[12]. Although the pathophysiology of MASLD is not yet fully elucidated, insulin resistance associated with obesity is believed to play a central role. A complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors, including rich processed foods diets and sedentary lifestyles, contributes to the accumulation of triglycerides and lipids within hepatocytes. Additionally, adipose tissue hypertrophy and ectopic fat deposition - frequently observed in affected patients - may promote hepatic lipogenesis, oxidative stress, and the activation of hepatic stellate cells, leading to sub

MASLD encompasses a broad clinical spectrum, ranging from simple hepatic steatosis to more severe forms characterized by hepatic inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning, referred to as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Studies have demonstrated that the risk of MASH is two to threefold higher in individuals with obesity and/or T2DM[11,13-15]. Therefore, the presence of MASH also carries a higher risk of liver fibrosis progression, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1,5,14,15]. It is estimated that approximately 10%-20% of patients with MASLD will develop MASH and subsequently progress to ACLD and its complications[15]. Therefore, early diagnosis and accurate staging are crucial to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with ACLD due to MASLD, as well as other related outcomes such as cardiovascular disease and malignancies[16]. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing hepatic fibrosis; however, several limitations restrict its widespread indication[17-21]. In addition to its considerable cost, even an adequate biopsy sample represents 1/50000 of the liver parenchyma, rendering the procedure susceptible to sampling error mainly due to disease heterogeneity. Significant inter- and intra-observer variability in histopathological interpretation has also been documented. Moreover, the procedure comes with certain risks, such as pain, bleeding, infection, perforation, and, in rare cases, death[1,16,22].

Despite these limitations, the development and validation of noninvasive methods (NIMs) for liver fibrosis assessment - characterized by safety, reproducibility, and applicability for disease monitoring - have become the focus of extensive research[23-25]. Various NIMs employing different diagnostic strategies have been evaluated in MASLD, targeting either the quantification of hepatic steatosis or the determination of hepatic fibrosis. These include clinical and laboratory-based biomarkers, as well as scoring systems derived from intrinsic properties of hepatic tissue. Among these, liver el

A comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted in the PubMed, Cochrane Library, SciELO, and LILACS databases to identify relevant studies addressing MASLD, noninvasive biomarkers, and liver fibrosis. The search strategy included the following terms and their synonyms: “metabolic steatotic liver disease”, “noninvasive markers”, and “liver fibrosis”. Studies published in English or Portuguese were considered eligible for inclusion. The inclusion criteria comprised original articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses involving adult human subjects that focused on the diagnosis, staging, or risk stratification of liver fibrosis using NIMs. Exclusion criteria included editorials, case reports, conference abstracts, animal studies, and articles unrelated to the scope of MASLD or liver fibrosis evaluation. After screening titles and abstracts for relevance and assessing full texts according to the eligibility criteria, a total of 76 articles were selected for qualitative synthesis. The study selection process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, ensuring transparency and methodological rigor.

The rates of progression from MASLD to MASH and the development of hepatic fibrosis or hepatic decompensation are multifactorial. It depends on the initial severity of the disease, genetic predisposition, environmental factors, as well as the presence of comorbidities, such as T2DM[1,11]. Fibrosis progresses at an estimated rate of 0.09 stages per year, indicating that it takes approximately 14.3 years to advance one stage of fibrosis in MASLD and 7.1 years in MASH[3]. Based on the initially proposed classification by Kleiner et al[36], four distinct patterns of liver fibrosis have been described, with stage F4 corresponding to liver cirrhosis. Key concepts for disease progression include the recognition of advanced fibrosis (AF), corresponding to Metavir stages F3-F4, and significant fibrosis, defined as fibrosis greater than stage F2. The latter group has recently been identified as comprising patients at higher risk of disease progression (at-risk MASH) who would benefit most from early diagnosis, inclusion in clinical trials, and interventions aimed at preventing adverse outcomes. T2DM and obesity are other important drivers of disease progression[36-39].

The search for less invasive and more feasible methods to screen for hepatic fibrosis has emerged in response to the limitations of liver biopsy previously mentioned and the high prevalence of patients at risk of developing advanced forms of the disease, highlighting the importance of NIMs for diagnostic purposes[40-43]. Therefore, several criteria are essential when selecting a diagnostic test. In addition to safety and reproducibility, consideration must be given to the clinical setting in which the test will be applied, as well as the local disease prevalence, to define the most appropriate diagnostic goals[21,22,40]. In low-prevalence settings, such as primary care, tests with high negative predictive value are preferred to rule out AF. Conversely, in specialized centers with a higher prevalence of MASLD, confirmatory tests with high specificity and positive predictive value are desirable[1,21,40]. Thus, in primary care, the optimal strategy involves an initial simple and inexpensive blood-based test (e.g., FIB-4) to exclude AF, followed by a confirmatory test with high specificity (e.g., vibration-controlled transient elastography [VCTE] or patented serum biomarkers) if the initial test is positive[1,40,44-46]. This sequential strategy was evaluated in a United Kingdom cohort of patients with suspected MASLD, where 81% were identified as low-risk and managed within primary care. Therefore, only 19% required referral to hepatology services[47]. The application of this algorithm significantly reduced unnecessary specialist referrals and improved the precision of identifying patients in need of advanced care. In a separate study, Perera et al[48] assessed the clinical and cost-effectiveness of implementing NIMs in AF detection in primary care. Their results demonstrated that the use of NIMs led to a meaningful reduction in inappropriate referrals and achieved cost savings ranging from 3% to 17%, reinforcing the value of integrating NIMs into routine primary care pathways for the early identification and man

The indirect methods, which involve assessing liver biochemistry parameters such as aminotransferases and liver function tests (including bilirubin, albumin, and coagulation tests), are insufficient for the diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis, as these could remain normal despite advanced disease or conversely be abnormal only in late stages of cirrhosis. Therefore, several clinical scores combining laboratory, anthropometric, and clinical data have been proposed and extensively evaluated to optimize the prediction of disease severity. The APRI, initially developed by Wai et al[28] for predicting AF in patients with chronic hepatitis C, has since been validated for other LDs and the prediction of liver-related outcomes[49,50]. Its main advantage lies in the broad availability of its components and the simplicity of calculation. It also has a potentially reliable role in predicting cardiovascular risk in patients with metabolic syndrome, as an APRI > 1.5 was associated with an elevated cardiovascular risk[51]. Although APRI showed high diagnostic accuracy in chronic hepatitis C populations, its performance in MASLD is modest and inferior to other tests[52]. The NFS, developed by Angulo et al[31], is based on age, BMI, diabetes status or glucose intolerance, albumin, platelet count, and AST/ALT ratio. Though slightly more complex, these variables are widely accessible. Suggested cutoffs of < -1.455 and > 0.676 enable the reliable exclusion and confirmation of AF, with negative and positive predictive values of 93% and 90%, respectively[31]. While widely validated across ethnicities with reproducible accuracy, its performance in MASLD cohorts is suboptimal [negative predictive value (NPV): 89%; net present value (PPV): 25%][41], with moderate performance. Therefore, NFS is no longer the primary NIM recommended for screening in the latest American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines, being substituted by the FIB-4 score[1,44].

The BARD score, proposed by Harrison et al[32], integrates BMI ≥ 28, AST/ALT ratio ≥ 0.8, and diabetes, producing a weighted score where 2-4 points correlate with an odds ratio of 17 for AF (95% confidence interval: 9.2-31.9) and an NPV of 96%. However, subsequent studies, especially after the adoption of MASLD terminology, revealed a suboptimal performance of BARD (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUROC]: 0.59-0.61)[50,42].

Sterling et al[29] introduced the FIB-4 index in a cohort of hepatitis C virus/human immunodeficiency virus co-infected patients, which can be calculated using age, AST, ALT, and platelet count. Suggested cutoffs are < 1.3 to exclude AF (NPV: 90%) and > 2.67 to confirm its presence (PPV: 65%). The FIB-4 has since been validated across various etiologies for predicting liver complications, HCC, and all-cause mortality[52,53]. In MASLD, Shah et al[54] found FIB-4 to be superior to other scores, with subsequent meta-analyses supporting its high accuracy (AUROC: 0.80-0.85). FIB-4 is the endorsed NIM for fibrosis initial screening by American, European, and Brazilian guidelines, with a cutoff of less than 1.3 to rule out AF and more than 2.67 to rule it in[1,21,44-46,54]. However, limitations include age (under 35 or over 65) and the presence of T2DM[53,54]. A cutoff of 2 has been proposed for AF exclusion in patients older than 65. Nonetheless, data from a recently published study in the primary care setting suggest that this threshold may result in a significant rate of false negatives[55,56]. A multicenter study (14 tertiary centers) evaluated the optimal FIB-4 cutoff for predicting AF in 1050 patients with biopsy-proven MASLD. The lower and upper cutoff points suggested by the authors, based on age range, are as follows: 1.05 and 1.21 ≤ 49 years, 1.24 and 1.96 in the 50-59 years age range, 1.88 and 2.67 in the 60-69 years age range, and 1.95 and 2.67 in the ≥ 70 years age range. These cutoff points were defined to achieve a sensitivity and specificity of 90%[57]. Therefore, the FIB-4 score should be used with caution, mainly in patients older than 65, and further studies are necessary to establish the optimal cutoff for this subgroup of patients.

Recently, a novel multi-targeted machine learning framework (FIB-9, FIB-11, and FIB-12) has been developed, designed to enhance the performance of the FIB-4 index in predicting AF[58]. FIB-9 is based on nine routinely available blood biomarkers - AST, ALT, gamma-glutamyl transferase, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, albumin, platelets, prothrombin index (or international normalized ratio), and urea - adjusted for demographic and metabolic variables such as age, weight, height, and diabetes status. It is freely accessible via an online calculator and is particularly suitable for population-level screening. FIB-11 builds upon this model by incorporating two additional fibrosis-specific markers, hyaluronate and alpha2-macroglobulin, achieving diagnostic accuracy exceeding 80%. FIB-12 further integrates liver stiffness measurement (LSM), demonstrating superior performance with an AUROC of 0.91 and the lowest indeterminate rate (16.4%) in ternary classification among the evaluated tools[58]. All three models offer a direct estimation of liver fibrosis stage (F0-F4), enhancing clinical interpretation and supporting more informed decision-making. Compared to conventional NIMs, these models demonstrate superior diagnostic accuracy, particularly when stratified into binary, ternary, or quaternary classification schemes. However, the increased complexity of the formulas, potential limitations in clinical accessibility due to future patenting, and diminished accuracy in patients with extreme biomarker values represent notable drawbacks; further data are required for their validation[58].

Direct biomarkers reflect serum levels of substances associated with fibrogenesis and extracellular matrix turnover. However, these markers are not liver-specific, representing a limitation since they can also be elevated in the presence of extrahepatic fibrosis, such as pulmonary fibrosis. Procollagen III (Pro-C3) has been proposed as a direct biomarker for predicting AF, either alone or in combination with demographic characteristics such as age or the presence of DM (ADAPT score composed by age, diabetes status, platelet count and Pro-C3 levels). It demonstrates good diagnostic accuracy for AF, with AUROC values of 0.75 and 0.81 when used alone or with the ADAPT score, respectively, in both tertiary settings for AF confirmation and primary care for its exclusion[56,57]. However, its clinical applicability remains limited due to high costs and low availability.

The ELF score was initially derived from a cohort of patients with CLD of various etiologies and incorporates age along with serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1, amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen, and hyaluronic acid[1,50,51]. A threshold of 7.7 or lower categorizes patients as low risk, while values above 7.7 indicate intermediate to high risk[1,21]. ELF values above 9.8 reliably identify patients with MASLD at increased risk of cirrhosis progression and liver-related events[46,59,60]. Additionally, in patients with suspected or confirmed AF, an ELF ≥ 11.3 predicts future liver-related outcomes[1]. ELF testing is recognized and recommended by both the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and European Association for the Study of the Liver societies as a second-line method for further evaluating patients at intermediate risk based on FIB-4 levels (> 1.3), guiding specialist referral[1,44,45]. However, this method also suffers from limited availability and high costs.

Imaging modalities enable not only the assessment of anatomic features of the liver but also the estimation of liver stiffness, serving as a surrogate marker of fibrosis. Liver stiffness can be measured using various elastography techniques, including VCTE - FibroScan, ultrasound-based elastography (point shear wave or acoustic radiation force impulse [ARFI] and two-dimensional shear wave), and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE)[22,61-63]. VCTE is the most validated technique for assessing liver stiffness. It has been shown to accurately predict fibrosis stages (primarily for excluding AF), liver-related outcomes, and both overall and liver-specific mortality[1,44,64]. Different cutoff values can be used depending on the clinical objective. In routine clinical practice, a cutoff of less than 8 kPa effectively excludes AF with good diagnostic accuracy[1,21,22,63]. Conversely, values above 12 kPa indicate a high risk of AF, with PPVs ranging from 76% to 88% in hepatology or endocrinology clinic populations, where the prevalence of MASLD is high[1,21,44,45].

For other ultrasound-based elastography techniques (ARFI and two-dimensional shear wave), optimal cutoff values are less well-established compared to VCTE[65]. However, their diagnostic performance has been considered comparable[23,66-68]. A recent meta-analysis involving 29 studies demonstrated that ARFI performs well in differentiating simple steatosis from significant fibrosis and offers excellent accuracy in identifying AF, with sensitivity and specificity of 92% and 85%, respectively, and an AUROC of 0.94 when using a cutoff value of 2.06 m/second[69]. The integration of ARFI technology into conventional ultrasound systems is one of the major advantages over VCTE, as it enables a comprehensive evaluation of the liver, including assessment of cirrhosis, the presence of portal hypertension, and even the identification of focal lesions. A liver stiffness value of less than 9 kPa (1.7 m/second), in the absence of other known clinical signs, has recently been proposed as a criterion to rule out compensated ACLD (cACLD)[68]. Conversely, values greater than 13 kPa (2.1 m/second) are highly suggestive of cACLD, and when greater than 17 kPa (2.4 m/second), the probability of clinically significant portal hypertension should be considered. However, additional studies may be required[22,68].

Although transient elastography (TE) and ultrasound-based elastography are highly effective diagnostic tools for assessing liver fibrosis[1,22,44,68], they present several limitations, including restricted use in obese patients, increased skin-to-liver capsule distance, narrow intercostal spaces, and the presence of ascites. Operator expertise, the selection of the appropriate probe (e.g., M or XL for TE), and adherence to high-quality criteria - such as obtaining at least 10 valid measurements with an interquartile range less than 30% of the median - are essential for reliable LSMs. Additionally, transient increases in liver stiffness caused by acute inflammation, cholestasis, or hepatic congestion can lead to overestimation of fibrosis. Standardization of measurement protocols, control of confounding clinical factors, and cross-validation with other noninvasive markers or histology remain crucial to enhance the diagnostic performance and clinical utility of elastography[24,70].

MRE quantifies liver stiffness by measuring the propagation velocity of shear waves generated by an external mechanical driver through the hepatic tissue. The shear wave speed increases proportionally with tissue stiffness. MRE is considered the most accurate noninvasive diagnostic tool for detecting and staging liver fibrosis[1,22,44,71-73]. MRE demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity in quantifying steatosis, as well as in predicting AF, with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve values ranging from 0.92 to 0.96[1,44,74]. LSM with MRE is also helpful for HCC risk prediction in patients with cACLD[75].

However, despite its high diagnostic accuracy, several limitations prevent its broader clinical implementation. Cost is a significant barrier. Adding MRE capability to a magnetic resonance imaging scanner requires substantial investment, and per-examination costs remain higher than those of ultrasound-based techniques[76,77]. Furthermore, MRE is primarily available only in specialized centers, reducing accessibility in primary care and low-resource settings[77,78]. Technical and patient-related limitations to MRE are also relevant. The technique depends on breath-hold compliance and is sensitive to motion artifacts, reducing its utility in patients with ascites, dyspnea, or cognitive impairment[79]. Moreover, the presence of severe hepatic iron overload may impair MRE performance by attenuating signal intensity, and factors such as claustrophobia or obesity may preclude adequate image acquisition[80,81]. Lastly, there is no universal consensus on optimal cutoff values for MRE. Notably, MRE-based LSM values are not directly comparable to TE, to which the commonly cited “rule of four” applies. Some of the proposed thresholds are: < 2.5 kPa as normal; 3.0-3.5 kPa indicating fibrosis stages 1-2; 3.5-4.0 kPa for stages 2-3; 4.0-5.0 kPa for stages 3-4; and > 5.0 kPa as indicative of stage 4 fibrosis or cirrhosis. Furthermore, MRE can reliably distinguish between mild (F0-F2) and significant (F3-F4) fibrosis, with sensitivity ranging from 86% to 91% and specificity between 80% and 85%[64]. The main advantages of MRE are its noninvasive nature, high accuracy, and the ability to examine a much larger hepatic volume than ultrasound ela

| NIM | Rule-in cutoff | Rule-out cutoff | AUROC1 | Strengths and limitations |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| APRI | < 0.5 | > 1.5 | 0.74 | False positive in patients with alternative causes of thrombocytopenia |

| FIB-4 | < 1.32; < 1.67 | ≥ 2.67; ≥ 3.483 | 0.84 | No added cost; low accuracy in patients younger than 35 years; low specificity in those older than 65 years |

| NFS | < -1.44 | ≥ 0.672 | 0.82 | No added cost; not accurate in age < 35 years, people with obesity and type 2 diabetes Restricted use to MASLD |

| ELF | < 7.7; < 7.73 | ≥ 9.8; ≥ 11.33 | 0.83 | Cost and not widely available; less useful for early fibrosis |

| Imaging techniques | ||||

| VCTE | < 8 kPa; < 8 kPa3 | ≥ 12 kPa; ≥ 20 kPa3 | 0.9 | Point of care, possibility of steatosis degree evaluation; necessity of specific device; confounded by active hepatitis, food intake, congestive heart failure, biliary obstruction, amyloidosis, ascites; less applicable and reliable in severe obesity (especially with M probe) |

| pSWE (ARFI) | < 1.3 m/second | > 2.1 m/second | 0.8-0.9 | Integration into conventional ultrasound systems, which enables a comprehensive evaluation of the liver at the same time; cut points not well validated; Probably affected by the same confounders as VCTE, though the success rate is higher than VCTE in obese patients |

| 2D-SWE | < 8 kPa | > 12 kPa | 0.80-0.98 | Integration into conventional ultrasound systems, which enables a comprehensive evaluation of the liver at the same time; cut points not well validated; probably affected by the same confounders as VCTE |

| MRE | < 2.55 kPa; < 3 kPa3 | ≥ 3.63kPa; ≥ 5 kPa3 | 0.89-0.96 | Superior performance in detecting early-stage fibrosis; integration into routine liver MRI allows both fibrosis staging and surveillance of other liver pathologies, such as HCC; cost, not widely available; probably affected by the same confounders as VCTE and iron content; some patients may have contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging or have claustrophobia |

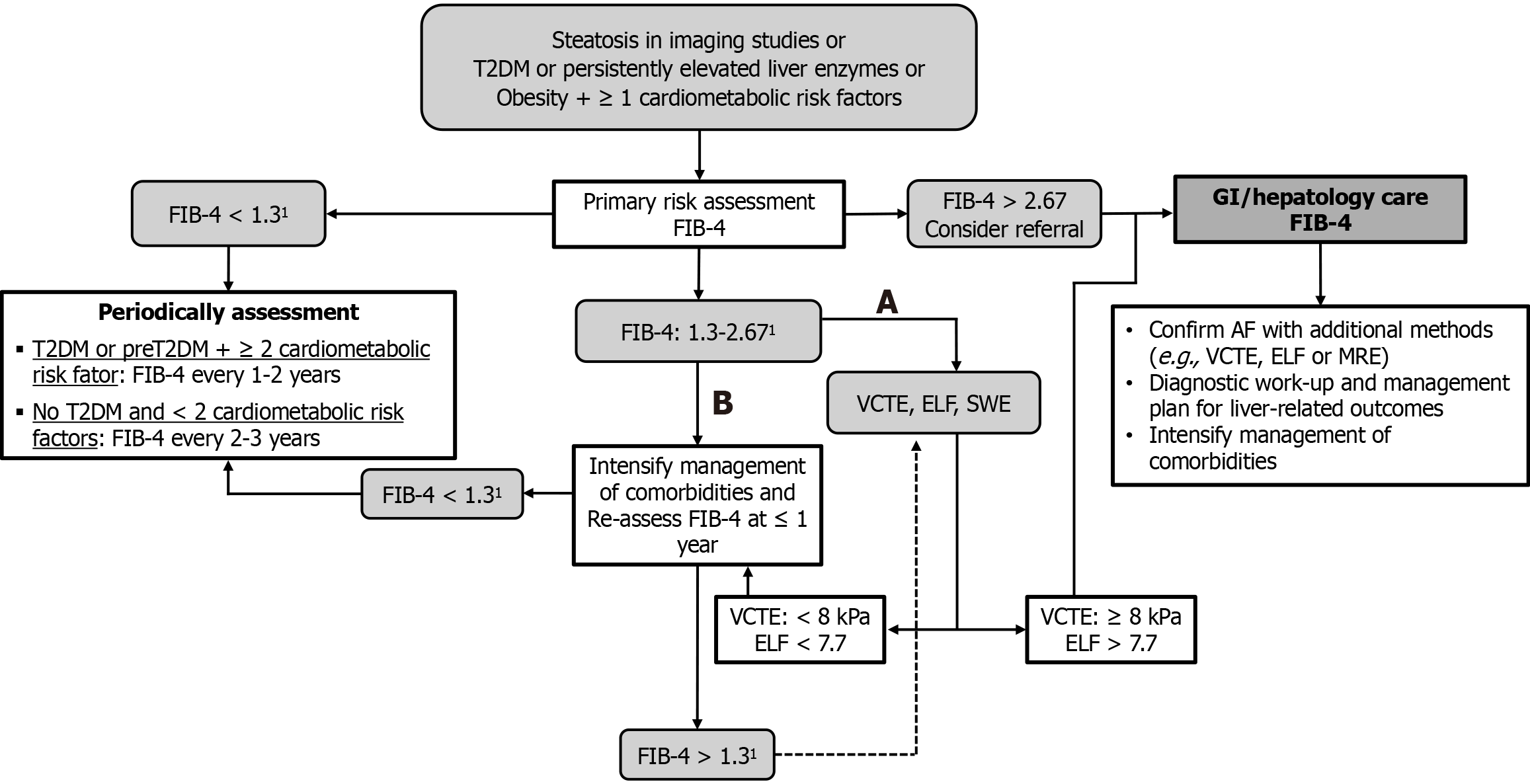

While NIMs are increasingly recommended, awareness of their limitations remains crucial. A significant drawback is the “indeterminate zone” (40%-60% of cases), where results remain inconclusive, which can be mitigated by sequential strategies that combine different modalities of tests, as recently proposed by major liver societies[1,21,44-46]. A stepwise approach has been widely endorsed by international guidelines and real-world studies, aiming to balance diagnostic performance, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility. A frequently recommended strategy involves initial screening with the FIB-4 index, a simple, widely available score, followed by LSM using TE in patients with intermediate or indeterminate FIB-4 values[44-46,82]. For patients with a FIB-4 score < 1.3 (under 65 years) or < 2.0 (≥ 65 years), AF can often be ruled out, whereas those between 1.3 and 2.67 warrant further imaging evaluation[1]. In selected populations - such as those with obesity, inconclusive TE results, or suspected confounders like inflammation - MRE may be considered as a second-line modality due to its superior reproducibility and accuracy[83]. For settings where imaging is not immediately available, a biomarker-based second-line test, such as the ELF score, may be an alternative[44,46]. Combining noninvasive tools in this way reduces unnecessary biopsies, increases specificity for AF, and supports individualized patient care[84,85]. A proposed algorithm for the sequential approach might follow the sequence: FIB-4 TE MRE or ELF, depending on local resources, patient comorbidities, and pretest probability of fibrosis (Figure 1).

Heredity plays a crucial role in fat accumulation and the progression of liver injury. However, genetic predisposition alone does not fully account for the wide phenotypic variability observed in MASLD. Epigenetics, a heritable yet reversible phenomenon, modulates gene expression without altering the DNA sequence and represents a promising new avenue for understanding MASLD development and progression, with special emphasis on microRNAs (miRNAs)[29]. Dysregulation of these post-transcriptional regulators of complementary target miRNAs has demonstrated high prognostic and predictive value in MASLD[29,74]. These molecules can be detected in serum, plasma, saliva, urine, and formalin-fixed tissues. In humans, miRNA expression appears to be tissue-specific. When released into circulation via cellular microvesicles, these miRNAs function as signaling molecules, and several miRNAs have been identified in various studies[86,87].

Among the studies, notable examples include miR-122[88], miR-192[89], miR-21, miR-34a, miR-451[90,91], miR-1290, miR-27b-3p, miR-192-5p[92], miR-301a-3p, miR-34a-5p, miR-375, lncRNA-RABGAP1 L-DT-206[93]. Given the need for reliable and innovative biomarkers, circulating miRNAs have emerged as attractive candidates for the diagnosis and staging of LDs[30]. Beyond genetic factors, inflammation is recognized as a central contributor to MASLD pathogenesis and progression, with the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β serving as a key mediator in initiating and sustaining hepatic inflammation. Interleukin-1β is secreted as an inactive precursor and activated through the action of caspase-1, neutrophil serine proteases, proteinase 3, and neutrophil elastase. Several studies suggest that NE and proteinase 3 are important drivers of chronic inflammation and that imbalances between these enzymes and their inhibitor, alpha-1 antitrypsin, may contribute to obesity-induced insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and MASLD[4]. This systematic review has potential limitations that should be acknowledged. The heterogeneity in the patient population, as well as in the diagnostic criteria related to the disease nomenclature modification, and the different technologies and NIMs may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the risk of publication bias cannot be excluded, particularly given the reliance on studies with positive results. Besides that, the cross-sectional design of most studies precludes assessment of longitudinal outcomes and limits conclusions regarding prognostic utility.

Given the high prevalence of MASLD and the risks associated with biopsy for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis, NIMs have emerged as promising diagnostic alternatives. Liver elastography, particularly VCTE for assessing liver stiffness and MRE for measuring fibrosis, is considered the noninvasive gold standard. Among serum scores, FIB-4 and NFS are valuable for ruling out AF and selecting candidates for liver biopsy, although their low positive predictive value requires complementary tests. The combination of methods, such as FIB-4 and elastography, represents a practical strategy for monitoring, determining the need for referral to a specialist, and guiding the indication for liver biopsy. Despite the relevance and applicability of these biomarkers, further studies are necessary to enhance the accuracy of NIMs, establish cutoff points ideally outside indeterminate ranges, and integrate multiple assessment modalities to predict early liver fibrosis risk more accurately.

| 1. | Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, Barb D, Kleiner DE, Loomba R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77:1797-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1465] [Cited by in RCA: 1606] [Article Influence: 535.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Miao L, Targher G, Byrne CD, Cao YY, Zheng MH. Current status and future trends of the global burden of MASLD. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2024;35:697-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 216.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1382] [Cited by in RCA: 2473] [Article Influence: 353.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5322] [Cited by in RCA: 7965] [Article Influence: 796.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 5. | Mirea AM, Toonen EJM, van den Munckhof I, Munsterman ID, Tjwa ETTL, Jaeger M, Oosting M, Schraa K, Rutten JHW, van der Graaf M, Riksen NP, de Graaf J, Netea MG, Tack CJ, Chavakis T, Joosten LAB. Increased proteinase 3 and neutrophil elastase plasma concentrations are associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes. Mol Med. 2019;25:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67:123-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1028] [Cited by in RCA: 1842] [Article Influence: 230.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chan WK, Chuah KH, Rajaram RB, Lim LL, Ratnasingam J, Vethakkan SR. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2023;32:197-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 155.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2413] [Cited by in RCA: 2652] [Article Influence: 189.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:434-438. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J; International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1999-2014.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2367] [Cited by in RCA: 2432] [Article Influence: 405.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 11. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 2023;79:1542-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1676] [Cited by in RCA: 1833] [Article Influence: 611.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Byrne CD, Targher G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S47-S64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1516] [Cited by in RCA: 2270] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, Basu R, Caprio S, Garvey WT, Kashyap S, Mechanick JI, Mouzaki M, Nadolsky K, Rinella ME, Vos MB, Younossi Z. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Primary Care and Endocrinology Clinical Settings: Co-Sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract. 2022;28:528-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 681] [Article Influence: 170.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Maher JJ, Leon P, Ryan JC. Beyond insulin resistance: Innate immunity in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:670-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Loomba R, Adams LA. The 20% Rule of NASH Progression: The Natural History of Advanced Fibrosis and Cirrhosis Caused by NASH. Hepatology. 2019;70:1885-1888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1017-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1449] [Cited by in RCA: 1638] [Article Influence: 96.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Agbim U, Asrani SK. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis and prognosis: an update on serum and elastography markers. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:361-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 18. | Loomba R, Adams LA. Advances in non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Gut. 2020;69:1343-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | European Association for Study of Liver; Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Higado. EASL-ALEH Clinical Practice Guidelines: Non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:237-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1177] [Cited by in RCA: 1384] [Article Influence: 125.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Aleknavičiūtė-Valienė G, Banys V. Clinical importance of laboratory biomarkers in liver fibrosis. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2022;32:030501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis - 2021 update. J Hepatol. 2021;75:659-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 993] [Cited by in RCA: 1309] [Article Influence: 261.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Duarte-Rojo A, Taouli B, Leung DH, Levine D, Nayfeh T, Hasan B, Alsawaf Y, Saadi S, Majzoub AM, Manolopoulos A, Haffar S, Dundar A, Murad MH, Rockey DC, Alsawas M, Sterling RK. Imaging-based noninvasive liver disease assessment for staging liver fibrosis in chronic liver disease: A systematic review supporting the AASLD Practice Guideline. Hepatology. 2025;81:725-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dawod S, Brown K. Non-invasive testing in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1499013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dietrich CF, Bamber J, Berzigotti A, Bota S, Cantisani V, Castera L, Cosgrove D, Ferraioli G, Friedrich-Rust M, Gilja OH, Goertz RS, Karlas T, de Knegt R, de Ledinghen V, Piscaglia F, Procopet B, Saftoiu A, Sidhu PS, Sporea I, Thiele M. EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Use of Liver Ultrasound Elastography, Update 2017 (Long Version). Ultraschall Med. 2017;38:e16-e47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 601] [Cited by in RCA: 610] [Article Influence: 67.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zoncapè M, Liguori A, Tsochatzis EA. Non-invasive testing and risk-stratification in patients with MASLD. Eur J Intern Med. 2024;122:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cardoso AC, A Villela-Nogueira C, de Figueiredo-Mendes C, Leão Filho H, Pinto Silva RA, Valle Tovo C, Perazzo H, Matteoni AC, de Carvalho-Filho RJ, Lisboa Bittencourt P. Brazilian Society of Hepatology and Brazilian College of Radiology practice guidance for the use of elastography in liver diseases. Ann Hepatol. 2021;22:100341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lin ZH, Xin YN, Dong QJ, Wang Q, Jiang XJ, Zhan SH, Sun Y, Xuan SY. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;53:726-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 821] [Cited by in RCA: 817] [Article Influence: 54.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2762] [Cited by in RCA: 3352] [Article Influence: 145.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL, Messinger D, Nelson M; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 3830] [Article Influence: 191.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Balakrishnan M, Loomba R. The Role of Noninvasive Tests for Differentiating NASH From NAFL and Diagnosing Advanced Fibrosis Among Patients With NAFLD. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, George J, Farrell GC, Enders F, Saksena S, Burt AD, Bida JP, Lindor K, Sanderson SO, Lenzi M, Adams LA, Kench J, Therneau TM, Day CP. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45:846-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1917] [Cited by in RCA: 2379] [Article Influence: 125.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 32. | Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, Gogia S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57:1441-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rosenberg WM, Voelker M, Thiel R, Becka M, Burt A, Schuppan D, Hubscher S, Roskams T, Pinzani M, Arthur MJ; European Liver Fibrosis Group. Serum markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1704-1713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 756] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Dongiovanni P, Meroni M, Longo M, Fargion S, Fracanzani AL. miRNA Signature in NAFLD: A Turning Point for a Non-Invasive Diagnosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bıçakçı E, Demirtaş CÖ, Çelikel Ç, Haklar G, Duman DG. Myeloperoxidase and calprotectin; Any role as non-invasive markers for the prediction of ınflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2020;31:681-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, Ferrell LD, Liu YC, Torbenson MS, Unalp-Arida A, Yeh M, McCullough AJ, Sanyal AJ; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6807] [Cited by in RCA: 8586] [Article Influence: 408.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 37. | Ajmera V, Cepin S, Tesfai K, Hofflich H, Cadman K, Lopez S, Madamba E, Bettencourt R, Richards L, Behling C, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. A prospective study on the prevalence of NAFLD, advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in people with type 2 diabetes. J Hepatol. 2023;78:471-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Castera L, Laouenan C, Vallet-Pichard A, Vidal-Trécan T, Manchon P, Paradis V, Roulot D, Gault N, Boitard C, Terris B, Bihan H, Julla JB, Radu A, Poynard T, Brzustowsky A, Larger E, Czernichow S, Pol S, Bedossa P, Valla D, Gautier JF; QUID-NASH investigators. High Prevalence of NASH and Advanced Fibrosis in Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Study of 330 Outpatients Undergoing Liver Biopsies for Elevated ALT, Using a Low Threshold. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:1354-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Price JK, Owrangi S, Gundu-Rao N, Satchi R, Paik JM. The Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1999-2010.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 96.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Shah N, Sanyal AJ. A Pragmatic Management Approach for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatosis and Steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sanyal AJ, Castera L, Wong VW. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Fibrosis in NAFLD. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:2026-2039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zhou JH, Cai JJ, She ZG, Li HL. Noninvasive evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Current evidence and practice. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1307-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 43. | Han S, Choi M, Lee B, Lee HW, Kang SH, Cho Y, Ahn SB, Song DS, Jun DW, Lee J, Yoo JJ. Accuracy of Noninvasive Scoring Systems in Assessing Liver Fibrosis in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gut Liver. 2022;16:952-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. 2024;81:492-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 993] [Article Influence: 496.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Moreira RO, Valerio CM, Villela-Nogueira CA, Cercato C, Gerchman F, Lottenberg AMP, Godoy-Matos AF, Oliveira RA, Brandão Mello CE, Álvares-da-Silva MR, Leite NC, Cotrim HP, Parisi ER, Silva GF, Miranda PAC, Halpern B, Pinto Oliveira C. Brazilian evidence-based guideline for screening, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in adult individuals with overweight or obesity: A joint position statement from the Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism (SBEM), Brazilian Society of Hepatology (SBH), and Brazilian Association for the Study of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome (Abeso). Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2023;67:e230123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wattacheril JJ, Abdelmalek MF, Lim JK, Sanyal AJ. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Noninvasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1080-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Srivastava A, Gailer R, Tanwar S, Trembling P, Parkes J, Rodger A, Suri D, Thorburn D, Sennett K, Morgan S, Tsochatzis EA, Rosenberg W. Prospective evaluation of a primary care referral pathway for patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019;71:371-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 47.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Srivastava A, Jong S, Gola A, Gailer R, Morgan S, Sennett K, Tanwar S, Pizzo E, O'Beirne J, Tsochatzis E, Parkes J, Rosenberg W. Cost-comparison analysis of FIB-4, ELF and fibroscan in community pathways for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. . 2019;19:122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Loaeza-del-Castillo A, Paz-Pineda F, Oviedo-Cárdenas E, Sánchez-Avila F, Vargas-Vorácková F. AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) for the noninvasive evaluation of liver fibrosis. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:350-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Wu YL, Kumar R, Wang MF, Singh M, Huang JF, Zhu YY, Lin S. Validation of conventional non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems in patients with metabolic associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:5753-5763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 51. | De Matteis C, Cariello M, Graziano G, Battaglia S, Suppressa P, Piazzolla G, Sabbà C, Moschetta A. AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) is an easy-to-use predictor score for cardiovascular risk in metabolic subjects. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (19)] |

| 52. | Kouvari M, Valenzuela-Vallejo L, Guatibonza-Garcia V, Polyzos SA, Deng Y, Kokkorakis M, Agraz M, Mylonakis SC, Katsarou A, Verrastro O, Markakis G, Eslam M, Papatheodoridis G, George J, Mingrone G, Mantzoros CS. Liver biopsy-based validation, confirmation and comparison of the diagnostic performance of established and novel non-invasive steatotic liver disease indexes: Results from a large multi-center study. Metabolism. 2023;147:155666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Chen X, Goh GB, Huang J, Wu Y, Wang M, Kumar R, Lin S, Zhu Y. Validation of Non-invasive Fibrosis Scores for Predicting Advanced Fibrosis in Metabolic-associated Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10:589-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K, Tetri BN, Contos MJ, Sanyal AJ; Nash Clinical Research Network. Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1104-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1240] [Article Influence: 72.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 55. | Sung S, Al-Karaghouli M, Tam M, Wong YJ, Jayakumar S, Davyduke T, Ma M, Abraldes JG. Age-dependent differences in FIB-4 predictions of fibrosis in patients with MASLD referred from primary care. Hepatol Commun. 2025;9:e0609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | McPherson S, Hardy T, Dufour JF, Petta S, Romero-Gomez M, Allison M, Oliveira CP, Francque S, Van Gaal L, Schattenberg JM, Tiniakos D, Burt A, Bugianesi E, Ratziu V, Day CP, Anstee QM. Age as a Confounding Factor for the Accurate Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Advanced NAFLD Fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:740-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 712] [Article Influence: 79.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Ishiba H, Sumida Y, Tanaka S, Yoneda M, Hyogo H, Ono M, Fujii H, Eguchi Y, Suzuki Y, Yoneda M, Takahashi H, Nakahara T, Seko Y, Mori K, Kanemasa K, Shimada K, Imai S, Imajo K, Kawaguchi T, Nakajima A, Chayama K, Saibara T, Shima T, Fujimoto K, Okanoue T, Itoh Y; Japan Study Group of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (JSG-NAFLD). The novel cutoff points for the FIB4 index categorized by age increase the diagnostic accuracy in NAFLD: a multi-center study. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1216-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Calès P, Canivet CM, Costentin C, Lannes A, Oberti F, Fouchard I, Hunault G, de Lédinghen V, Boursier J. A new generation of non-invasive tests of liver fibrosis with improved accuracy in MASLD. J Hepatol. 2025;82:794-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Daniels SJ, Leeming DJ, Eslam M, Hashem AM, Nielsen MJ, Krag A, Karsdal MA, Grove JI, Neil Guha I, Kawaguchi T, Torimura T, McLeod D, Akiba J, Kaye P, de Boer B, Aithal GP, Adams LA, George J. ADAPT: An Algorithm Incorporating PRO-C3 Accurately Identifies Patients With NAFLD and Advanced Fibrosis. Hepatology. 2019;69:1075-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Sagir A, Erhardt A, Schmitt M, Häussinger D. Transient elastography is unreliable for detection of cirrhosis in patients with acute liver damage. Hepatology. 2008;47:592-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Tang A, Cloutier G, Szeverenyi NM, Sirlin CB. Ultrasound Elastography and MR Elastography for Assessing Liver Fibrosis: Part 1, Principles and Techniques. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:22-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Yin M, Venkatesh SK. Ultrasound or MR elastography of liver: which one shall I use? Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:1546-1551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Barr RG, Ferraioli G, Palmeri ML, Goodman ZD, Garcia-Tsao G, Rubin J, Garra B, Myers RP, Wilson SR, Rubens D, Levine D. Elastography Assessment of Liver Fibrosis: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2015;276:845-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Lin H, Lee HW, Yip TC, Tsochatzis E, Petta S, Bugianesi E, Yoneda M, Zheng MH, Hagström H, Boursier J, Calleja JL, Goh GB, Chan WK, Gallego-Durán R, Sanyal AJ, de Lédinghen V, Newsome PN, Fan JG, Castéra L, Lai M, Harrison SA, Fournier-Poizat C, Wong GL, Pennisi G, Armandi A, Nakajima A, Liu WY, Shang Y, de Saint-Loup M, Llop E, Teh KK, Lara-Romero C, Asgharpour A, Mahgoub S, Chan MS, Canivet CM, Romero-Gomez M, Kim SU, Wong VW; VCTE-Prognosis Study Group. Vibration-Controlled Transient Elastography Scores to Predict Liver-Related Events in Steatotic Liver Disease. JAMA. 2024;331:1287-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 72.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Xiao G, Zhu S, Xiao X, Yan L, Yang J, Wu G. Comparison of laboratory tests, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance elastography to detect fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66:1486-1501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 492] [Cited by in RCA: 679] [Article Influence: 75.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Mózes FE, Lee JA, Selvaraj EA, Jayaswal ANA, Trauner M, Boursier J, Fournier C, Staufer K, Stauber RE, Bugianesi E, Younes R, Gaia S, Lupșor-Platon M, Petta S, Shima T, Okanoue T, Mahadeva S, Chan WK, Eddowes PJ, Hirschfield GM, Newsome PN, Wong VW, de Ledinghen V, Fan J, Shen F, Cobbold JF, Sumida Y, Okajima A, Schattenberg JM, Labenz C, Kim W, Lee MS, Wiegand J, Karlas T, Yılmaz Y, Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, Cassinotto C, Aggarwal S, Garg H, Ooi GJ, Nakajima A, Yoneda M, Ziol M, Barget N, Geier A, Tuthill T, Brosnan MJ, Anstee QM, Neubauer S, Harrison SA, Bossuyt PM, Pavlides M; LITMUS Investigators. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Gut. 2022;71:1006-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 89.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 67. | Karagiannakis DS, Markakis G, Lakiotaki D, Cholongitas E, Vlachogiannakos J, Papatheodoridis G. Comparing 2D-shear wave to transient elastography for the evaluation of liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34:961-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Barr RG, Wilson SR, Rubens D, Garcia-Tsao G, Ferraioli G. Update to the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Liver Elastography Consensus Statement. Radiology. 2020;296:263-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 69. | Lin Y, Li H, Jin C, Wang H, Jiang B. The diagnostic accuracy of liver fibrosis in non-viral liver diseases using acoustic radiation force impulse elastography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Sterling RK, Duarte-Rojo A, Patel K, Asrani SK, Alsawas M, Dranoff JA, Fiel MI, Murad MH, Leung DH, Levine D, Taddei TH, Taouli B, Rockey DC. AASLD Practice Guideline on imaging-based noninvasive liver disease assessment of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. Hepatology. 2025;81:672-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 95.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 71. | Park CC, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, Bettencourt R, Ramirez K, Fortney L, Hooker J, Sy E, Savides MT, Alquiraish MH, Valasek MA, Rizo E, Richards L, Brenner D, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. Magnetic Resonance Elastography vs Transient Elastography in Detection of Fibrosis and Noninvasive Measurement of Steatosis in Patients With Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:598-607.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 571] [Article Influence: 63.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Loomba R, Wolfson T, Ang B, Hooker J, Behling C, Peterson M, Valasek M, Lin G, Brenner D, Gamst A, Ehman R, Sirlin C. Magnetic resonance elastography predicts advanced fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2014;60:1920-1928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Chatterjee A, Miller FH, Pang E. Magnetic Resonance Elastography of Liver: Current Status and Future Directions. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2024;07:215-225. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 74. | Thiele M, Johansen S, Israelsen M, Trebicka J, Abraldes JG, Gines P, Krag A; MicrobPredict, LiverScreen, LiverHope and GALAXY consortia. Noninvasive assessment of hepatic decompensation. Hepatology. 2025;81:1019-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Ajmera V, Kim BK, Yang K, Majzoub AM, Nayfeh T, Tamaki N, Izumi N, Nakajima A, Idilman R, Gumussoy M, Oz DK, Erden A, Quach NE, Tu X, Zhang X, Noureddin M, Allen AM, Loomba R. Liver Stiffness on Magnetic Resonance Elastography and the MEFIB Index and Liver-Related Outcomes in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participants. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:1079-1089.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 76. | Eslam M, Wong GL, Hashem AM, Chan HL, Nielsen MJ, Leeming DJ, Chan AW, Chen Y, Duffin KL, Karsdal M, Schattenberg JM, George J, Wong VW. A Sequential Algorithm Combining ADAPT and Liver Stiffness Can Stage Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Hospital-Based and Primary Care Patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:984-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Huang J, Zhao J. Quantitative Diagnosis Progress of Ultrasound Imaging Technology in Thyroid Diffuse Diseases. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Charoenchue P, Khorana J, Chitapanarux T, Inmutto N, Na Chiangmai W, Amantakul A, Pojchamarnwiputh S, Tantraworasin A. Two-Dimensional Shear-Wave Elastography: Accuracy in Liver Fibrosis Staging Using Magnetic Resonance Elastography as the Reference Standard. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;15:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Li J, Venkatesh SK, Yin M. Advances in Magnetic Resonance Elastography of Liver. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2020;28:331-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Chen J, Talwalkar JA, Yin M, Glaser KJ, Sanderson SO, Ehman RL. Early detection of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by using MR elastography. Radiology. 2011;259:749-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Kazi IN, Kuo L, Tsai E. Noninvasive Methods for Assessing Liver Fibrosis and Steatosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2024;20:21-29. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1264-1281.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 1124] [Article Influence: 160.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 83. | Singh S, Venkatesh SK, Wang Z, Miller FH, Motosugi U, Low RN, Hassanein T, Asbach P, Godfrey EM, Yin M, Chen J, Keaveny AP, Bridges M, Bohte A, Murad MH, Lomas DJ, Talwalkar JA, Ehman RL. Diagnostic performance of magnetic resonance elastography in staging liver fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:440-451.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 84. | Correction to Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5: 362-73. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Tapper EB, Hunink MG, Afdhal NH, Lai M, Sengupta N. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Risk Stratification of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) by the Primary Care Physician Using the NAFLD Fibrosis Score. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Su K, Li Z, Yu Y, Zhang X. The prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor roxadustat: Paradigm in drug discovery and prospects for clinical application beyond anemia. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25:1262-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Pirola CJ, Fernández Gianotti T, Castaño GO, Mallardi P, San Martino J, Mora Gonzalez Lopez Ledesma M, Flichman D, Mirshahi F, Sanyal AJ, Sookoian S. Circulating microRNA signature in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: from serum non-coding RNAs to liver histology and disease pathogenesis. Gut. 2015;64:800-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 41.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Bala S, Petrasek J, Mundkur S, Catalano D, Levin I, Ward J, Alao H, Kodys K, Szabo G. Circulating microRNAs in exosomes indicate hepatocyte injury and inflammation in alcoholic, drug-induced, and inflammatory liver diseases. Hepatology. 2012;56:1946-1957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 532] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Becker PP, Rau M, Schmitt J, Malsch C, Hammer C, Bantel H, Müllhaupt B, Geier A. Performance of Serum microRNAs -122, -192 and -21 as Biomarkers in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Cermelli S, Ruggieri A, Marrero JA, Ioannou GN, Beretta L. Circulating microRNAs in patients with chronic hepatitis C and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Yamada H, Suzuki K, Ichino N, Ando Y, Sawada A, Osakabe K, Sugimoto K, Ohashi K, Teradaira R, Inoue T, Hamajima N, Hashimoto S. Associations between circulating microRNAs (miR-21, miR-34a, miR-122 and miR-451) and non-alcoholic fatty liver. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;424:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 92. | Tan Y, Ge G, Pan T, Wen D, Gan J. A pilot study of serum microRNAs panel as potential biomarkers for diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Albadawy R, Agwa SHA, Khairy E, Saad M, El Touchy N, Othman M, El Kassas M, Matboli M. Circulatory Endothelin 1-Regulating RNAs Panel: Promising Biomarkers for Non-Invasive NAFLD/NASH Diagnosis and Stratification: Clinical and Molecular Pilot Study. Genes (Basel). 2021;12:1813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/