Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.111211

Revised: September 2, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 216 Days and 9.2 Hours

The global rise in childhood obesity has made metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) the leading cause of pediatric liver disease. Stu

Core Tip: The escalating prevalence of pediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) mirrors the rise in pediatric obesity. The advent of non-invasive diagnostics may allow for earlier recognition of liver fibrosis, and may prioritize the need for early pharmacological therapy. We propose an updated diagnostic and monitoring algorithm incorporating recent multi-societal statements in pediatric MASLD. The increased use of weight-loss pharmacotherapy such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in adolescent patients has shown efficacy in inducing weight loss, which may have potential in halting MASLD progression if instituted early in the disease course.

- Citation: Ng NBH, Sng AA, Huang JG. Fighting the epidemic of pediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Role of non-invasive diagnostics and early pharmacological intervention. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 111211

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/111211.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.111211

The incidence of pediatric obesity and commonly associated pediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) have reached epidemic proportions. Although geographic variation in regional prevalences - 8.53% in North America and 7.01% in Asia, and a 52.49% prevalence in children with overweight or obesity[1] is noted, within Asia, a meta-analysis of mainland Chinese children reported a 43% prevalence of MASLD amongst children with overweight and obesity[2]. Eslam et al[3,4] first proposed a consensus-driven change in nomenclature of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) to metabolic (dysfunction) associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), followed by an updated 2023 consensus statement[5] to replace the stigmatizing term ‘fatty’ with ‘steatotic’ in the current nomenclature of MASLD. This change has been generally accepted in the adult and pediatric populations in recognition of the central role of metabolic-dysregulation in the underlying pathophysiology of this condition, and the metabolic risk factors associated with it[3,6,7]. Importantly, the rising prevalence of pediatric obesity has led to a parallel increase in the prevalence of pediatric MASLD. In fact, MASLD is now recognized as one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease affecting children and adolescents[8]. Timely recognition and therapeutic intervention for pediatric MASLD is urgently needed.

This narrative review was performed through a literature review on PubMed, where articles published between the years 2000 to 2025 were identified using the key concepts of “pediatric” AND “MASLD or MAFLD or NAFLD or steatohepatitis or steatosis or fatty liver disease”. The articles summarized in the review included those that pertained to non-invasive diagnostics and pharmacotherapy in the pediatric age group. Only English language studies were included.

The current working definition of pediatric MASLD is based on the updated 2023 multi-society Delphi consensus statement[5] to the above-mentioned 2021 consensus by Eslam et al[3], followed by a pediatric multi-societal statement of endorsement[9]: Biochemical/radiological/histopathological evidence of hepatic steatosis with one or more of 5 cardio-metabolic criterion: (1) Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 85th percentile for age/sex (BMI z-score ≥ +1) or waist circumference > 95th percentile or ethnicity adjusted with or without; (2) Fasting serum glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or serum glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L or 2 hour post-load glucose levels ≥ 7.8 mmol/L or glycated hemoglobin ≥ 5.7% or existing/diagnosed/currently-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) or treatment for T2DM; (3) Hypertension: Blood pressure ≥ 95th percentile or ≥ 130/80 mmHg whichever is lower for age < 13 years; age > 13 years: 130/80 mmHg or antihypertensive drug treatment; (4) Plasma triglycerides ≥ 1.15 mmol/L (age < 10 years); ≥ 1.7 mmol/L (age ≥ 10 years) or lipid-lowering treatment; and (5) Plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol ≤ 1.0 mmol/L or lipid-lowering treatment.

However, as pediatric obesity and its metabolic complications become more prevalent, it is possible that children with MASLD may also have co-existing etiologies for steatotic liver disease i.e., ‘MASLD overlap’. The pediatric multi-societal statement particularly emphasizes that pediatric MASLD should only be diagnosed after alternate differential diagnoses are excluded with first-line investigations[9].

MASLD is considered an umbrella term to encompass the entire spectrum of steatotic liver disease associated with metabolic dysregulation - simple steatosis (> 5% hepatocytes with fat infiltration), steatohepatitis to steatofibrosis and cirrhosis. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is a subset of MASLD in which there is active hepatitis and inflammation-driven liver injury (hepatocyte ballooning, lobular inflammation, apoptosis etc.) and fibrosis.

Studies have consistently shown alarmingly high rates of advanced fibrosis in adolescents with MASLD, where 10%-20% of patients in tertiary care settings have advanced fibrosis[10]. In addition, there is suggestion that children with MASLD may run a more severe clinical course and be at higher risk for liver damage than adults[11]. This is due to histopathological differences in pediatric MASLD, in which portal inflammation is more predominant[12] and this predilection for portal/periportal hepatitis predisposes to higher rates of advanced fibrosis[13]. In contrast, adult-type MASLD is characterized by more hepatocyte ballooning injury and a higher prevalence of peri-sinusoidal zone 3 fibrosis[12].

The early onset of chronic liver disease means children are at risk for liver-related adverse events over a longer du

While clinical criteria for the diagnosis of MASLD has been outlined in multiple consensus statements, there remains a diagnostic gap for the spectrum of MASLD. The gold standard for the diagnosis of steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis and cirrhosis is ultimately through liver histological examination, but the invasive nature of liver biopsies may make this unacceptable to patients and caregivers. Non-invasive diagnostic strategies for the spectrum of pediatric MASLD would therefore be welcomed in supporting clinicians who manage these children. These non-invasive modalities can also potentially be utilized in the surveillance and monitoring of treatment outcomes in MASLD.

In this minireview, we discuss the various non-invasive diagnostic modalities used for the evaluation of MASLD, and propose an updated diagnostic and monitoring algorithm incorporating recent multi-societal statements. We also discuss the importance of early pharmacological intervention in pediatric MASLD, in particular the use of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) which may have potential to halt MASLD progression if instituted early, and the potential role for novel anti-fibrotic therapy in this population.

We discuss below the non-invasive diagnostics for pediatric MASLD. The diagnostic accuracies of the tests performed in pediatric MASLD cohorts, unless stated otherwise, are summarized in Table 1[20-29].

| Diagnostic | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUROC | Comparison | Ref. | |

| Serum ALT ≥ 50 (boys) ≥ 44 (girls) in overweight children ≥ 10 years | 0.88 | 0.26 | - | Biopsy-proven NAFLD | Schwimmer et al[28], 2013 | |

| Serum ALT ≥ 80 in overweight children ≥ 10 years | 0.57 | 0.71 | - | Biopsy NAFLD | Schwimmer et al[28], 2013 | |

| 0.61 | 0.62 | - | Biopsy NASH | |||

| 0.76 | 0.59 | - | Biopsy advanced fibrosis | |||

| Serum ALT ≥ 26 (boys) ≥ 22 (girls) | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.66 | Ultrasound-detected steatosis + metabolic risk factors | Di Bonito et al[21], 2025 | |

| PNFS | 0.97 (cutoff > 8%) | 0.33 (cutoff > 8%) | 0.74 | Biopsy (advanced fibrosis | Alkhouri et al[20], 2014 | |

| Ultrasonography | 0.60-0.65 | - | - | Biopsy mild steatosis (5%-33%; adult data) | Ferraioli et al[22], 2019 | |

| 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.93 | Moderate-severe steatosis (20%-30%; adult data) | Hernaez et al[23], 2011 | ||

| TE-CAP | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.94 | Biopsy/MRS S1-S3 steatosis | Jia et al[25], 2021 | |

| TE-CAP | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.95 | Biopsy, imaging or MRI-PDFF | Xu et al[29], 2025 | |

| TE-LSM | > 7.4 kPa | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.99 | Biopsy-proven significant fibrosis (≥ F2) | Nobili et al[26], 2008 |

| > 10.2 kPa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | Biopsy: Advanced fibrosis | ||

| > 8.5 kPa | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.76 | Advanced liver disease on biopsy (MASLD subset of larger pediatric cohort of CLD) | Jarasvaraparn et al[24], 2025 | |

| MR elastography (cut-off 3.05 kPa) | 0.50 | 0.92 | 0.92 | Biopsy (advanced fibrosis | Schwimmer et al[27], 2017 | |

| MRI-PDFF | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.96 | Biopsy/MRS S1-S3 steatosis | Jia et al[25], 2021 | |

Serum alanine aminotransferase: Serum transaminases have been the main screening tool for MASLD in children with obesity, with a typical pattern of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation more than aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Concomitant elevation in gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) and AST may predict more severe histopathological features[28]. Additionally, a recent adult cohort study showed a cholestatic biochemical pattern of MASLD, defined by ALT:alkaline phosphatase (ALP) ratio of less than 2, had poorer outcomes in terms of liver decompensation events and mortality than the hepatocellular pattern[30]. This suggests the importance of examining all biochemical indices of the liver function test, rather than serum ALT alone.

There are variations in ALT thresholds in the diagnosis of MASLD. The North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition 2017 NAFLD guidelines quote normal cut-offs of 22 mg/dL for girls and 26 mg/dL for boys, and the use of two times the gender-specific ALT (ALT ≥ 50 in boys, ≥ 44 girls) in overweight children with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 26% for the diagnosis of MASLD[31]. The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) 2012 guidelines recommend similar cut-off values and propose a combination of serum ALT and ultrasonography to diagnose MASLD. While the serum ALT is a convenient and rea

Prediction scoring indices: Several scoring indices for MASLD have been developed based on a composite of anthropometric measurements and serum biomarkers. The fatty liver index combines waist circumference, triglycerides, body-mass index and serum GGT, and has modest diagnostic accuracy in pediatric validation studies [area under curve

Ultrasound: The comprehensive prevention project for overweight and obese adolescents study from China defined hepatic steatosis based on sonographic criteria of at least two features of the following: Diffusely increased hepatic echogenicity greater than kidney or spleen, vascular blurring and/or deep signal attenuation[39]. Abdominal sonography is poorly sensitive in milder degrees of hepatic steatosis (< 20%), and also cannot reliably distinguish between steatosis, steatohepatitis and fibrosis[40] until definite features of established cirrhosis have occurred i.e., coarsened hepatic echotexture and splenomegaly. Moreover, increased hepatic echogenicity may occur with other causes of hepatitis and infiltration of other substances (e.g., glycogen)[9]. The ESPGHAN 2012 guidelines recommend combining ultrasonography and serum aminotransferase testing in all children with obesity[41].

VCTE: The limitations of standard abdominal sonography have led to the advent of newer ultrasound-based modalities to measure liver stiffness and better distinguish steatosis from fibrosis. Shear-wave elastography techniques, such as VCTE and acoustic radiation force impulse techniques, involve the generation of shear waves in the liver. The mea

Specific limitations in pediatrics include a wider variation of body habitus, influencing the skin-to-liver capsule distance and the choice of probe size (S pediatric probe, standard M probe, XL probe). Exact pediatric cut-off norms in VCTE parameters are still not well-established and there are slight variations between existing pediatric publications, possibly influenced by patient factors (age, habitus) and probe size. VCTE data from 867 adolescents in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017-2018 defined the cut-off threshold for any degree of steatosis as median CAP ≥ 248 dBm and significant fibrosis (≥ F2) as liver stiffness ≥ 7.4 kPa[34]. The systematic review by Draijer et al[38] noted excellent diagnostic accuracy (AUC near 1.0) for significant fibrosis (≥ F2) based on two liver stiffness cut-offs (8.2 kPa with S-probe[46] and 7.4 kPa with M-probe[26]) in two separate studies by Alkhouri et al[46] and Nobili et al[26] respectively. We await the results of the pediatric LiverKids study of a large cohort of 2866 subjects between 9-16 years, in which the investigators aim to determine the prevalence of significant fibrosis based on a LSM of ≥ 6.5 kPa and that of NAFLD based on CAP ≥ 225 dBm[47].

Magnetic resonance imaging: Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is considered the most accurate non-invasive modality for liver fibrosis, similarly based on the generation of mechanical shear waves in the liver as with sonographic techniques. MRE has obvious advantages to sonographic shear wave techniques in patients with extremely large habitus and/or concomitant ascites. Magnetic resonance imaging-proton density fat-fraction liver mapping (MRI-PDFF) is a fat quantitative technique based on the differential proton signals in mobile water and visceral fat content, and accurately quantify fat across the entire liver as opposed to liver biopsies[48]. The broader utilization of MRE and MRI-PDFF is limited in the pediatric population due to the high cost, possible need for general anesthesia in an uncooperative child and need for expert radiologist analysis.

The discussion in the earlier section had centered upon the utility of non-invasive modalities in the accurate diagnosis of fibrosis/steatosis in children; there exists very limited pediatric data on the utility of these modalities for monitoring therapeutic response. A common and reasonable target is the normalization of serum ALT within pediatric norms, despite serum ALT being an imperfect biomarker of therapeutic response[32]. Data from the pediatric FORCE dataset suggests that Fibroscan® is a reasonably good and feasible alternative to liver biopsy in monitoring serial disease progression for pediatric chronic liver disease[45] and may be potentially useful in monitoring therapeutic response once pediatric cut-offs are well-established.

It is also important to establish appropriate follow-up time-intervals for each non-invasive modality to detect clinically significant changes. The performance of MRI-PDFF and VCTE was explored in the recent phase 3 MAESTRO-NASH trial[49], which incorporated these non-invasive modalities alongside biopsy-proven endpoints in adults with MASLD. In this trial, resmetirom treatment was associated with a ≥ 30% reduction in liver fat by MRI-PDFF, which showed a strong association with histological improvement, including resolution of steatohepatitis and improvement in fibrosis stage. In contrast, transient elastography (VCTE) did not demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in liver stiffness from baseline to week 52 across all arms; however, a trend toward reduced stiffness was noted in the higher-dose resmetirom group[49]. These findings suggest that MRI-PDFF may be a more sensitive early marker of therapeutic response than VCTE, particularly for capturing improvements in steatosis and early inflammatory changes.

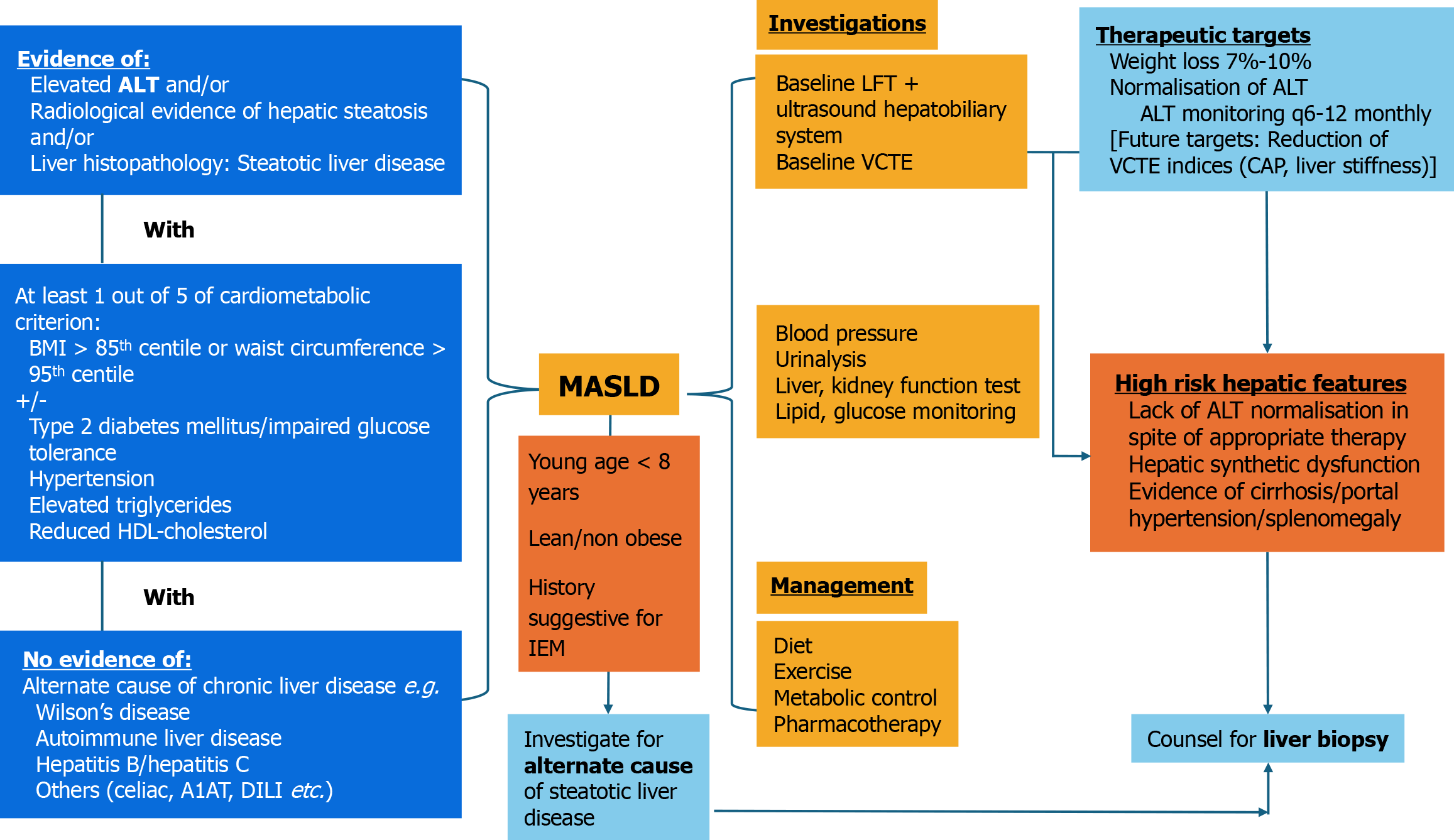

We propose a management algorithm (Figure 1) based on the updated 2023 multi-societal consensus on MASLD[5] and the pediatric multi-societal statement in 2024[9], with a particular emphasis on the need to exclude alternate etiologies especially in the very young and lean MASLD. We also propose a combined diagnostic approach akin to that proposed in the ESPGHAN 2012 pediatric MASLD guidelines[41], with the addition of a baseline VCTE (baseline liver function test + ultrasonography + VCTE). Sonography is key to detect early signs of portal hypertension e.g., splenomegaly +/- intra-abdominal varices, prompting the need for more definitive evaluation. Current therapeutic targets for pediatric MASLD would be weight loss and normalization of ALT, although future targets could include reduction in CAP/Liver stiffness indices in VCTE. There are no formal recommendations for the optimal follow-up intervals for VCTE monitoring to date.

Longitudinal follow-up data from clinical trials have demonstrated that one-third of children with steatosis go on to develop definite MASH with or without advanced fibrosis within 2 years[50]. In fact, a 10-year follow-up study of 51 adolescents had reported fibrosis progression in 16% of the cohort, where 6% developed advanced fibrosis[51]. While cirrhosis and MASLD-associated end stage liver disease are reportedly rare in the pediatric population, these late complications have been described[52,53]. These findings highlight the need for early detection and treatment of MASLD, especially in the pediatric age group.

Lifestyle interventions incorporating dietary modification and exercise to achieve weight loss have been the mainstay of management for pediatric MASLD[54]. Previous studies have suggested that weight loss as low as 1 kg can improve serum biomarkers of MASLD in children, and may also improve biopsy-proven MASLD when sustained weight loss is maintained for 24 months[55,56]. A BMI-z score reduction of 0.25 has been shown to be associated with significant improvements in serum ALT levels in children[57]. Lifestyle modifications focusing on diet and physical activity remain the first line treatment for MASLD in children. The lifestyle interventions that lead to improvements in BMI and waist circumference have been shown to improve MASH in children[50]. In recent clinical practice guidelines, intensive multi-component programs with high contact time have been recommended for management of obesity in children and adolescents[58,59]. These should readily incorporate changes that target behavior, motivation, dietary modifications and increased levels of physical activity. Importantly, the interventions should be available from multiple avenues, including in the community and schools where children spend the most time. Involving the family unit for weight interventions in children has been associated with higher success of weight loss compared to interventions that target the child alone[60]. Despite the importance of lifestyle modifications in managing pediatric MASLD, weight loss through lifestyle alone requires a high level of commitment and intrinsic motivation, which makes it challenging to sustain, especially in adolescents. Recently, there have been increasing use of adjunct pharmacological therapies for weight management in adolescents, which may also confer benefits to the clinical course of MASLD.

Revisiting use of metformin for pediatric MASLD management: Metformin has been established as the first line treatment for T2DM in both adults and adolescents. It has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and also confer modest benefit in terms of weight loss. As insulin resistance is a major contributor to the pathophysiology of MASLD, it is reasonable to postulate that metformin may lead to improvements in hepatic steatosis, even in children[61]. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials on the use of metformin in pediatric MASLD showed no significant improvement in liver enzymes. There was also insufficient pooled data to draw conclusions about the impact of metformin on liver ultrasonography or histology in pediatric patients with MASLD[62]. While use of metformin may indeed be helpful to some extent in children or adolescents with MASLD, there is no strong evidence currently to show that it reverses steatosis or reduces progression to fibrosis as a stand-alone agent. As such, metformin in itself may not be suitable as an early agent to halt the disease progression in pediatric MASLD. However, it can be considered in a subgroup of patients with glucose intolerance or established T2DM to drive improvement in insulin resistance and adiposity.

The promise of GLP-1RA in pediatric MASLD: GLP-1RA are incretin mimetics with excellent efficacy and safety profile in their use for obesity and diabetes mellitus, including in children and adolescents[63,64]. In addition to improvement in BMI and glycemic control, studies done in adults have also shown to offer multiple collateral benefits on metabolic health, such as dyslipidemia, polycystic ovarian syndrome and even MASLD[65-68]. Specifically, in the context of MASLD in adults, GLP-1RAs have been shown to improve hepatic insulin resistance, reduce free fatty acids, decrease intrahepatic triglycerides, which leads to reduced hepatic lipotoxicity[69,70]. The same may hold true for the adolescent population. For example, at present, liraglutide (Saxenda®) and semaglutide (Wegovy®) are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of obesity in children aged 12 years and above. While increasing numbers of adolescents with obesity are using GLP-1RA for weight management, data on efficacy for pediatric MASLD have been limited, with minimal direct studies evaluating this. In the hallmark clinical trial of use of liraglutide for adolescents with obesity, trial end points did not include biomarkers of MASLD as an outcome[63]. For the once weekly semaglutide trial for adolescents with obesity, there was significant improvement in percentage change in alanine transaminase level of

Earlier clinical trials on adult MASLD summarized in a systematic review meta-analysis in 2021 had reported that while GLP-1RA led to reduced steatosis in individuals with steatohepatitis, there were no statistically significant improvements in liver fibrosis[73]. The anti-fibrotic effects of liraglutide remain modest[54,74]. The outcome of the ESSENCE trial investigating subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg for treatment of biopsy-proven MASH with fibrosis is currently pending[75]. However, the preliminary results of the trial appear promising, showing significant improvements in both steatohepatitis and fibrosis[76]. It showed resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis in 62.9% vs 34.3% with placebo. Semaglutide also produced approximately 10% mean weight loss and broad improvements in non-invasive fibrosis/steatosis measures and cardiometabolic risk factors, with a gastrointestinal-tolerability-dominant safety profile and no new safety signals. This may lead to the eventual use of semaglutide specific for MASH, beyond just obesity and T2DM.

However, these outcomes have been not been replicated in the pediatric setting. To date, there has been no major studies evaluating the efficacy of GLP-1RA on pediatric MASLD using change in liver histology as an outcome. Despite that, as the beneficial effects of weight loss on pediatric MASLD have been well established, the potential impact of GLP-1RA in pediatric MASLD remains promising, with the hope that this will arrest further progression from steatosis to fibrosis if used timely at a younger age. Indeed, the recently published SCALE Kids trial on the use of liraglutide in children aged 6-12 years showing significant improvements in BMI compared to placebo with lifestyle interventions may lead to earlier initiation of GLP-1RA in pre-adolescents with obesity[77]. The hope is that earlier initiation of anti-obesity management can arrest the clinical progression of MASLD in the early stages, reducing the risk of liver fibrosis. Moving forward, future trials on GLP-1RA in children and adolescents should include an emphasis on outcomes specific to MASLD, including biochemical markers of hepatitis, and also on reversing steatosis and delaying progression to fibrosis.

Pushing boundaries - resmetirom for pediatric MASLD: Despite advancements in the understanding of the patho

Resmetirom, a successful example of the ongoing efforts in MASLD therapeutics, has recently received FDA approval for treatment of MASH in adults. This is in fact the first medication specifically indicated for treatment of MASH and fibrosis, and has been shown to be safe and effective in adults[79]. Resmetirom is an oral, liver-directed thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR-β) agonist. It selectively binds to THR-β that is predominantly expressed in the liver, mimicking the action of endogenous thyroid hormones, leading to fatty acid oxidation, reduction in intrahepatic lipogenesis and lipo-toxicity[80]. It also promotes increased mitochondrial biogenesis to improve capacity of handling the increased free fatty acids. These mechanisms in combination lead to reduction in hepatic steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis; the high hepatic THR-β selectively limits its effects on other thyroid hormone receptors found in the heart or bones, thereby reducing adverse systemic effects[80].

To date, there are no reports on the use of resmetirom in children or adolescents with MASH. The effects of this novel pharmacological intervention in children remains to be seen. Based on our current understanding of the clinical pro

| Medication class | Study design & population | Primary endpoint | Efficacy summary | Safety/adverse events | Ref. |

| GLP-1RA (liraglutide, semaglutide) | Retrospective cohort, n = 42, age ≤ 18 years, MASLD diagnosis, GLP-1RA prescribed for obesity or T2DM[1] | ALT reduction at 6 months and end-of-treatment | Significant mean ALT reduction (-56 U/L at 6 months, -37 U/L at EOT, | Mild-moderate GI symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea); no serious adverse events reported | Tou and Panganiban[72], 2025 |

| Metformin | Meta-analysis | ALT reduction | No significant improvement in ALT | GI upset, rare lactic acidosis | Gkiourtzis et al[62], 2023 |

| Lifestyle/standard of care | Longitudinal cohort, n = 440, pediatric MASLD | Composite improvement (ALT, GGT, histology) | 22% improved at 1 year, 31% at 2 years; 20% worsened; BMI and cholesterol changes most associated with outcomes | Not applicable | Newton et al[82], 2025 |

| Resmetirom | No pediatric studies to date | ||||

Pediatric data on probiotic use in MASLD has been promising, with a recent meta-analysis of 657 participants de

Despite the improvements in recognition, diagnostics and treatment options for MASLD, there continues to be several limitations specific to the pediatric population. As alluded to above, most of the scientific data have been derived from adult studies, with limited studies in children guiding recommendations. Moreover, many of the studies presented come from high- or middle-income countries, whose data may be specific to populations of similar affluence, with more access to novel diagnostic tools and therapeutics for MASLD. This is an important limitation when considering the global application of the findings of this review.

As in many other areas of pharmacological development, clinical trials involving adolescent and pediatric populations often lag significantly behind those conducted in adults. In most instances, drugs are used extensively in adult populations long before formal pediatric trials are initiated. This is not surprising, as conducting trials in children can be particularly challenging. Multiple factors contribute to this, including the stricter ethical requirements surrounding children as a vulnerable population, consent and assent requirements, regulatory challenges and also acceptability to participants and caregivers, especially when outcome measures involve invasive procedures such as liver biopsy for histological assessment[85,86]. Even after trials are completed successfully, regulatory approval for pediatric use typically requires a longer timeline. Collectively, these barriers continue to hinder the timely introduction of novel therapies for pediatric MASLD.

Lastly, the exact nature of ‘improvement in pediatric MASLD’ is still poorly defined in existing literature, and treatment targets are likely to evolve with the utilization of more precise diagnostics of MASLD. A common therapeutic goal for MASLD is the normalization of transaminases, but future targets may include regression of hepatic steatosis and possibly stabilization or regression of hepatic fibrosis on non-invasive diagnostics.

As we look into the future for diagnostics and therapeutics for pediatric MASLD, key research priorities include well-designed randomized controlled trials evaluating GLP-1RA and other emerging therapeutics, as current evidence is largely extrapolated from adult studies. There is also a critical need to validate non-invasive diagnostic cut-offs - such as biomarkers, elastography thresholds, and risk-stratification tools - specifically for children. Finally, large longitudinal cohorts are essential to clarify the natural history of pediatric MASLD, identify early predictors of progression, and inform timing of intervention.

Pediatric MASLD has emerged as the most common cause for pediatric chronic liver disease in most regions worldwide, contemporaneous with the burgeoning pediatric obesity pandemic. There is an alarmingly high rate of children with obesity complicated by MASLD already presenting with advanced fibrosis, raising the necessity for accurate non-invasive diagnostics. These would allow further risk stratification of affected children to identify those at highest risk of disease progression who may benefit from aggressive weight control therapy. The advent of GLP-1RAs may add value to the overall management of pediatric obesity and MASLD, with potential hopes that early utilization of GLP-1RAs may retard disease progression and even support reversal of fibrosis. Novel anti-fibrotic agents such as resmetirom may have a role in the pediatric population in future, but barriers exist in the implementation of trials and testing in this age group. It is important that the clinical and scientific community recognize these barriers and make a concerted effort to tailor safe and ethical trials for pediatric patients, without extrapolation from adult studies or time delay.

We thank Dr. Dimple Rajgor for her assistance in editing, formatting, reviewing, and in submitting the manuscript for publication.

| 1. | Li J, Ha A, Rui F, Zou B, Yang H, Xue Q, Hu X, Xu Y, Henry L, Barakat M, Stave CD, Shi J, Wu C, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. Meta-analysis: global prevalence, trend and forecasting of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents, 2000-2021. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56:396-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xiao Y, Pan YF, Dai Y, Sun YJ, Zhou Y, Yu YF. [Meta analysis of the prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in overweight and obese children and adolescents in China]. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2025;27:410-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Eslam M, Alkhouri N, Vajro P, Baumann U, Weiss R, Socha P, Marcus C, Lee WS, Kelly D, Porta G, El-Guindi MA, Alisi A, Mann JP, Mouane N, Baur LA, Dhawan A, George J. Defining paediatric metabolic (dysfunction)-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:864-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Wai-Sun Wong V, Dufour JF, Schattenberg JM, Kawaguchi T, Arrese M, Valenti L, Shiha G, Tiribelli C, Yki-Järvinen H, Fan JG, Grønbæk H, Yilmaz Y, Cortez-Pinto H, Oliveira CP, Bedossa P, Adams LA, Zheng MH, Fouad Y, Chan WK, Mendez-Sanchez N, Ahn SH, Castera L, Bugianesi E, Ratziu V, George J. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73:202-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2883] [Cited by in RCA: 3202] [Article Influence: 533.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78:1966-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1658] [Cited by in RCA: 1818] [Article Influence: 606.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Antonella M, Pietrobattista A, Maggiore G. Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A New Term for a More Appropriate Therapy in Pediatrics? Pediatr Rep. 2024;16:288-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang L, El-Shabrawi M, Baur LA, Byrne CD, Targher G, Kehar M, Porta G, Lee WS, Lefere S, Turan S, Alisi A, Weiss R, Faienza MF, Ashraf A, Sundaram SS, Srivastava A, De Bruyne R, Kang Y, Bacopoulou F, Zhou YH, Darma A, Lupsor-Platon M, Hamaguchi M, Misra A, Méndez-Sánchez N, Ng NBH, Marcus C, Staiano AE, Waheed N, Alqahtani SA, Giannini C, Ocama P, Nguyen MH, Arias-Loste MT, Ahmed MR, Sebastiani G, Poovorawan Y, Al Mahtab M, Pericàs JM, Reverbel da Silveira T, Hegyi P, Azaz A, Isa HM, Lertudomphonwanit C, Farrag MI, Nugud AAA, Du HW, Qi KM, Mouane N, Cheng XR, Al Lawati T, Fagundes EDT, Ghazinyan H, Hadjipanayis A, Fan JG, Gimiga N, Kamal NM, Ștefănescu G, Hong L, Diaconescu S, Li M, George J, Zheng MH. An international multidisciplinary consensus on pediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Med. 2024;5:797-815.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ramírez-Mejía MM, Díaz-Orozco LE, Barranco-Fragoso B, Méndez-Sánchez N. A Review of the Increasing Prevalence of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) in Children and Adolescents Worldwide and in Mexico and the Implications for Public Health. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e934134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN); European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN); Latin‐American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (LASPGHAN); Asian Pan‐Pacific Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (APPSPGHAN); Pan Arab Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (PASPGHAN); Commonwealth Association of Paediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition (CAPGAN); Federation of International Societies of Pediatric Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Nutrition (FISPGHAN). Paediatric steatotic liver disease has unique characteristics: A multisociety statement endorsing the new nomenclature. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;78:1190-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yu EL, Schwimmer JB. Epidemiology of Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2021;17:196-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Holterman AX, Guzman G, Fantuzzi G, Wang H, Aigner K, Browne A, Holterman M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in severely obese adolescent and adult patients. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:591-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Takahashi Y, Inui A, Fujisawa T, Takikawa H, Fukusato T. Histopathological characteristics of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: Comparison with adult cases. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:1066-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mann JP, De Vito R, Mosca A, Alisi A, Armstrong MJ, Raponi M, Baumann U, Nobili V. Portal inflammation is independently associated with fibrosis and metabolic syndrome in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2016;63:745-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang DQ, Singal AG, Kono Y, Tan DJH, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Changing global epidemiology of liver cancer from 2010 to 2019: NASH is the fastest growing cause of liver cancer. Cell Metab. 2022;34:969-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 99.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park JH, Hong JY, Shen JJ, Han K, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY. Increased Risk of Young-Onset Digestive Tract Cancers Among Young Adults Age 20-39 Years With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:3363-3373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schwimmer JB, Thai NQN, Noon SL, Ugalde-Nicalo P, Anderson SR, Chun LF, David RS, Goyal NP, Newton KP, Hansen EG, Lin B, Shapiro WL, Wang A, Yu EL, Behling CA. Long-term mortality and extrahepatic outcomes in 1096 children with MASLD: A retrospective cohort study. Hepatology. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1461-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2701] [Cited by in RCA: 2705] [Article Influence: 150.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Mosca A, Manco M, Braghini MR, Cianfarani S, Maggiore G, Alisi A, Vania A. Environment, Endocrine Disruptors, and Fatty Liver Disease Associated with Metabolic Dysfunction (MASLD). Metabolites. 2024;14:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jamialahmadi O, De Vincentis A, Tavaglione F, Malvestiti F, Li-Gao R, Mancina RM, Alvarez M, Gelev K, Maurotti S, Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Rosendaal FR, Kozlitina J, Pajukanta P, Pattou F, Valenti L, Romeo S. Partitioned polygenic risk scores identify distinct types of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Nat Med. 2024;30:3614-3623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alkhouri N, Mansoor S, Giammaria P, Liccardo D, Lopez R, Nobili V. The development of the pediatric NAFLD fibrosis score (PNFS) to predict the presence of advanced fibrosis in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Di Bonito P, Di Sessa A, Licenziati MR, Corica D, Wasniewska MG, Morandi A, Maffeis C, Faienza MF, Mozzillo E, Calcaterra V, Franco F, Maltoni G, Miraglia Del Giudice E, Umano GR, Valerio G. Ability of triglyceride-glucose indices to predict metabolic dysfunction associated with steatotic liver disease in pediatric obesity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2025;81:1287-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ferraioli G, Soares Monteiro LB. Ultrasound-based techniques for the diagnosis of liver steatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:6053-6062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 23. | Hernaez R, Lazo M, Bonekamp S, Kamel I, Brancati FL, Guallar E, Clark JM. Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1082-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 864] [Cited by in RCA: 1175] [Article Influence: 78.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 24. | Jarasvaraparn C, Anderson BP, Tolliver K, Adams KH, Bozic M, Molleston JP. The accuracy of Fibrosis score from FibroScan in diverse pediatric liver diseases at a single tertiary center. Dig Liver Dis. 2025;S1590-8658(25)01143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jia S, Zhao Y, Liu J, Guo X, Chen M, Zhou S, Zhou J. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Proton Density Fat Fraction vs. Transient Elastography-Controlled Attenuation Parameter in Diagnosing Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:784221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nobili V, Vizzutti F, Arena U, Abraldes JG, Marra F, Pietrobattista A, Fruhwirth R, Marcellini M, Pinzani M. Accuracy and reproducibility of transient elastography for the diagnosis of fibrosis in pediatric nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:442-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Angeles JE, Paiz M, Durelle J, Africa J, Newton KP, Brunt EM, Lavine JE, Abrams SH, Masand P, Krishnamurthy R, Wong K, Ehman RL, Yin M, Glaser KJ, Dzyubak B, Wolfson T, Gamst AC, Hooker J, Haufe W, Schlein A, Hamilton G, Middleton MS, Sirlin CB. Magnetic resonance elastography measured shear stiffness as a biomarker of fibrosis in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2017;66:1474-1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Schwimmer JB, Newton KP, Awai HI, Choi LJ, Garcia MA, Ellis LL, Vanderwall K, Fontanesi J. Paediatric gastroenterology evaluation of overweight and obese children referred from primary care for suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1267-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Xu ZL, Wang SR, Li WX, Deng YQ, Kang YF, Zhang YR, Li J, Cui XW. Diagnostic performance of point shear wave elastography and vibration-controlled transient elastography in paediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2025;15:e087101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ampuero J, Aller R, Gallego-Durán R, Crespo J, Calleja JL, García-Monzón C, Gómez-Camarero J, Caballería J, Lo Iacono O, Ibañez L, García-Samaniego J, Albillos A, Francés R, Fernández-Rodríguez C, Maya-Miles D, Diago M, Poca M, Andrade RJ, Latorre R, Jorquera F, Morillas RM, Escudero D, Hernández-Guerra M, Pareja-Megia MJ, Banales JM, Aspichueta P, Benlloch S, Rosales JM, Turnes J, Romero-Gómez M; HEPAmet Registry. The biochemical pattern defines MASLD phenotypes linked to distinct histology and prognosis. J Gastroenterol. 2024;59:586-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Vos MB, Abrams SH, Barlow SE, Caprio S, Daniels SR, Kohli R, Mouzaki M, Sathya P, Schwimmer JB, Sundaram SS, Xanthakos SA. NASPGHAN Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:319-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 464] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 87.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Arsik I, Frediani JK, Frezza D, Chen W, Ayer T, Keskinocak P, Jin R, Konomi JV, Barlow SE, Xanthakos SA, Lavine JE, Vos MB. Alanine Aminotransferase as a Monitoring Biomarker in Children with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Secondary Analysis Using TONIC Trial Data. Children (Basel). 2018;5:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ma X, Liu S, Zhang J, Dong M, Wang Y, Wang M, Xin Y. Proportion of NAFLD patients with normal ALT value in overall NAFLD patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ciardullo S, Monti T, Perseghin G. Prevalence of Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis Detected by Transient Elastography in Adolescents in the 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:384-390.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | de Silva MHAD, Hewawasam RP, Kulatunge CR, Chamika RMA. The accuracy of fatty liver index for the screening of overweight and obese children for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in resource limited settings. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Koot BG, van der Baan-Slootweg OH, Bohte AE, Nederveen AJ, van Werven JR, Tamminga-Smeulders CL, Merkus MP, Schaap FG, Jansen PL, Stoker J, Benninga MA. Accuracy of prediction scores and novel biomarkers for predicting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kalveram L, Baumann U, De Bruyne R, Draijer L, Janczyk W, Kelly D, Koot BG, Lacaille F, Lefere S, Lev HM, Lubrecht J, Mann JP, Mosca A, Rajwal S, Socha P, Vreugdenhil A, Alisi A, Hudert CA; ESPGHAN Fatty Liver Special Interest Group. Noninvasive scores are poorly predictive of histological fibrosis in paediatric fatty liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;78:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Draijer LG, van Oosterhout JPM, Vali Y, Zwetsloot S, van der Lee JH, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Chegary M, Benninga MA, Koot BGP. Diagnostic accuracy of fibrosis tests in children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. Liver Int. 2021;41:2087-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Farrell GC, Chitturi S, Lau GK, Sollano JD; Asia-Pacific Working Party on NAFLD. Guidelines for the assessment and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Asia-Pacific region: executive summary. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:775-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bozic D, Podrug K, Mikolasevic I, Grgurevic I. Ultrasound Methods for the Assessment of Liver Steatosis: A Critical Appraisal. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:2287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Vajro P, Lenta S, Socha P, Dhawan A, McKiernan P, Baumann U, Durmaz O, Lacaille F, McLin V, Nobili V. Diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: position paper of the ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:700-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ferraioli G, Barr RG, Dillman JR. Elastography for Pediatric Chronic Liver Disease: A Review and Expert Opinion. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40:909-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Siddiqui MS, Vuppalanchi R, Van Natta ML, Hallinan E, Kowdley KV, Abdelmalek M, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Dasarathy S, Brandman D, Doo E, Tonascia JA, Kleiner DE, Chalasani N, Sanyal AJ; NASH Clinical Research Network. Vibration-Controlled Transient Elastography to Assess Fibrosis and Steatosis in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:156-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 71.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Chaidez A, Pan Z, Sundaram SS, Boster J, Lovell M, Sokol RJ, Mack CL. The discriminatory ability of FibroScan liver stiffness measurement, controlled attenuation parameter, and FibroScan-aspartate aminotransferase to predict severity of liver disease in children. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:3015-3023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. FibroScan in Pediatric Cholestatic Liver Disease (FORCE). May 9, 2024. [cited 20 June 2025]. Available from: https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/study/187. |

| 46. | Alkhouri N, Sedki E, Alisi A, Lopez R, Pinzani M, Feldstein AE, Nobili V. Combined paediatric NAFLD fibrosis index and transient elastography to predict clinically significant fibrosis in children with fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2013;33:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chacón C, Arteaga I, Martínez-Escudé A, Ruiz Rojano I, Lamonja-Vicente N, Caballeria L, Ribatallada Diez AM, Schröder H, Montraveta M, Bovo MV, Ginés P, Pera G, Diez-Fadrique G, Pachón-Camacho A, Alonso N, Graupera I, Torán-Monserrat P, Expósito C. Clinical epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents. The LiverKids: Study protocol. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0286586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Caussy C, Reeder SB, Sirlin CB, Loomba R. Noninvasive, Quantitative Assessment of Liver Fat by MRI-PDFF as an Endpoint in NASH Trials. Hepatology. 2018;68:763-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 50.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Harrison SA, Taub R, Neff GW, Lucas KJ, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Alkhouri N, Bashir MR. Resmetirom for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2023;29:2919-2928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 95.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Xanthakos SA, Lavine JE, Yates KP, Schwimmer JB, Molleston JP, Rosenthal P, Murray KF, Vos MB, Jain AK, Scheimann AO, Miloh T, Fishbein M, Behling CA, Brunt EM, Sanyal AJ, Tonascia J; NASH Clinical Research Network. Progression of Fatty Liver Disease in Children Receiving Standard of Care Lifestyle Advice. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1731-1751.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Draijer L, Voorhoeve M, Troelstra M, Holleboom A, Beuers U, Kusters M, Nederveen A, Benninga M, Koot B. A natural history study of paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease over 10 years. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Alkhouri N, Hanouneh IA, Zein NN, Lopez R, Kelly D, Eghtesad B, Fung JJ. Liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in young patients. Transpl Int. 2016;29:418-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Molleston JP, White F, Teckman J, Fitzgerald JF. Obese children with steatohepatitis can develop cirrhosis in childhood. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2460-2462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Stroes AR, Vos M, Benninga MA, Koot BGP. Pediatric MASLD: current understanding and practical approach. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;184:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Nobili V, Manco M, Devito R, Ciampalini P, Piemonte F, Marcellini M. Effect of vitamin E on aminotransferase levels and insulin resistance in children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1553-1561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nobili V, Manco M, Devito R, Di Ciommo V, Comparcola D, Sartorelli MR, Piemonte F, Marcellini M, Angulo P. Lifestyle intervention and antioxidant therapy in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2008;48:119-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Khurana T, Klepper C, Fei L, Sun Q, Bramlage K, Arce-Clachar AC, Xanthakos S, Mouzaki M. Clinically Meaningful Body Mass Index Change Impacts Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Pediatr. 2022;250:61-66.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Ball GDC, Merdad R, Birken CS, Cohen TR, Goodman B, Hadjiyannakis S, Hamilton J, Henderson M, Lammey J, Morrison KM, Moore SA, Mushquash AR, Patton I, Pearce N, Ramjist JK, Lebel TR, Timmons BW, Buchholz A, Cantwell J, Cooper J, Erdstein J, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Hatanaka D, Lindsay P, Sajwani T, Sebastianski M, Sherifali D, Pierre JS, Ali MU, Wijesundera J, Alberga AS, Ausman C, Baluyot TC, Burke E, Dadgostar K, Delacruz B, Dettmer E, Dymarski M, Esmaeilinezhad Z, Hale I, Harnois-Leblanc S, Ho J, Gehring ND, Kucera M, Langer JC, McPherson AC, Naji L, Oei K, O'Malley G, Rigsby AM, Wahi G, Zenlea IS, Johnston BC. Managing obesity in children: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2025;197:E372-E389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, Avila Edwards KC, Eneli I, Hamre R, Joseph MM, Lunsford D, Mendonca E, Michalsky MP, Mirza N, Ochoa ER, Sharifi M, Staiano AE, Weedn AE, Flinn SK, Lindros J, Okechukwu K. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics. 2023;151:e2022060640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 778] [Cited by in RCA: 647] [Article Influence: 215.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Berge JM, Everts JC. Family-Based Interventions Targeting Childhood Obesity: A Meta-Analysis. Child Obes. 2011;7:110-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Mann JP, Tang GY, Nobili V, Armstrong MJ. Evaluations of Lifestyle, Dietary, and Pharmacologic Treatments for Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1457-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Gkiourtzis N, Michou P, Moutafi M, Glava A, Cheirakis K, Christakopoulos A, Vouksinou E, Fotoulaki M. The benefit of metformin in the treatment of pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pediatr. 2023;182:4795-4806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Kelly AS, Auerbach P, Barrientos-Perez M, Gies I, Hale PM, Marcus C, Mastrandrea LD, Prabhu N, Arslanian S; NN8022-4180 Trial Investigators. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Liraglutide for Adolescents with Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2117-2128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 76.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 64. | Tamborlane WV, Barrientos-Pérez M, Fainberg U, Frimer-Larsen H, Hafez M, Hale PM, Jalaludin MY, Kovarenko M, Libman I, Lynch JL, Rao P, Shehadeh N, Turan S, Weghuber D, Barrett T; Ellipse Trial Investigators. Liraglutide in Children and Adolescents with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:637-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Abushamat LA, Shah PA, Eckel RH, Harrison SA, Barb D. The Emerging Role of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists for the Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1565-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Austregésilo de Athayde De Hollanda Morais B, Martins Prizão V, de Moura de Souza M, Ximenes Mendes B, Rodrigues Defante ML, Cosendey Martins O, Rodrigues AM. The efficacy and safety of GLP-1 agonists in PCOS women living with obesity in promoting weight loss and hormonal regulation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Diabetes Complications. 2024;38:108834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Berberich AJ, Hegele RA. Lipid effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor analogs. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2021;32:191-199.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Wang MW, Lu LG. Current Status of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Clinical Perspective. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2025;13:47-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Patel Chavez C, Cusi K, Kadiyala S. The Emerging Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists for the Management of NAFLD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:29-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Yabut JM, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor-based Therapeutics for Metabolic Liver Disease. Endocr Rev. 2023;44:14-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Weghuber D, Barrett T, Barrientos-Pérez M, Gies I, Hesse D, Jeppesen OK, Kelly AS, Mastrandrea LD, Sørrig R, Arslanian S; STEP TEENS Investigators. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adolescents with Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2245-2257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 103.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 72. | Tou AM, Panganiban J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in pediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 73. | Mantovani A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Csermely A, Lonardo A, Targher G. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists for Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Metabolites. 2021;11:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Shan L, Wang F, Zhai D, Meng X, Liu J, Lv X. New Drugs for Hepatic Fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:874408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Newsome PN, Sanyal AJ, Engebretsen KA, Kliers I, Østergaard L, Vanni D, Bugianesi E, Rinella ME, Roden M, Ratziu V. Semaglutide 2.4 mg in Participants With Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis: Baseline Characteristics and Design of the Phase 3 ESSENCE Trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;60:1525-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Phase 3 ESSENCE Trial: Semaglutide in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2024;20:6-7. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Fox CK, Barrientos-Pérez M, Bomberg EM, Dcruz J, Gies I, Harder-Lauridsen NM, Jalaludin MY, Sahu K, Weimers P, Zueger T, Arslanian S; SCALE Kids Trial Group. Liraglutide for Children 6 to <12 Years of Age with Obesity - A Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:555-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 58.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Do A, Zahrawi F, Mehal WZ. Therapeutic landscape of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2025;24:171-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 69.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, Schattenberg JM, Loomba R, Taub R, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Neff GW, Rinella ME, Anstee QM, Abdelmalek MF, Younossi Z, Baum SJ, Francque S, Charlton MR, Newsome PN, Lanthier N, Schiefke I, Mangia A, Pericàs JM, Patil R, Sanyal AJ, Noureddin M, Bansal MB, Alkhouri N, Castera L, Rudraraju M, Ratziu V; MAESTRO-NASH Investigators. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:497-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 840] [Cited by in RCA: 1139] [Article Influence: 569.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Karim G, Bansal MB. Resmetirom: An Orally Administered, Smallmolecule, Liver-directed, β-selective THR Agonist for the Treatment of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis. touchREV Endocrinol. 2023;19:60-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Suvarna R, Shetty S, Pappachan JM. Efficacy and safety of Resmetirom, a selective thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist, in the treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:19790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 82. | Newton KP, Jayasekera D, Blackford AL, Behling C, Wilson LA, Fishbein MH, Molleston JP, Xanthakos SA, Vos MB, Schwimmer JB; NASH CRN. Longitudinal response to standard of care in pediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Rates of improvement and worsening, and factors associated with outcomes. Hepatology. 2025;82:1198-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Lu J, Dong X, Gao Z, Yan H, Shataer D, Wang L, Qin Y, Zhang M, Wang J, Cui J, Zhou S. Probiotics as a therapeutic strategy for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Res Food Sci. 2025;11:101138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Wilson BC, Zuppi M, Derraik JGB, Albert BB, Tweedie-Cullen RY, Leong KSW, Beck KL, Vatanen T, O'Sullivan JM, Cutfield WS; Gut Bugs Study Group. Long-term health outcomes in adolescents with obesity treated with faecal microbiota transplantation: 4-year follow-up. Nat Commun. 2025;16:7786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Roth-Cline M, Gerson J, Bright P, Lee CS, Nelson RM. Ethical considerations in conducting pediatric research. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2011;205:219-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Zhou YH, Kehar M, Ng NBH, Zheng MH. Letter: Resmetirom for treatment of MASH with children and adolescents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;60:982-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/