Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.110931

Revised: July 21, 2025

Accepted: November 17, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 190 Days and 20.1 Hours

Glucocorticoids (GC) are the cornerstone in the treatment of severe alcohol-associated hepatitis (SAH) but may be associated with adverse events.

We report a prospective series of patients with SAH who were treated with GC and developed de novo arthropathy within 2 weeks of GC cessation. Five patients were included in this series, three of whom were women. All patients underwent ultrasound evaluation and were referred to the Rheumatology Clinics. Final diagnoses were: Arthralgia associated with GC cessation (n = 3), polymyalgia rheumatica (n = 1) and psoriatic arthritis (n = 1). Joint soreness was the main symptom, whereas arthritis occurred rarely. Patients with arthralgia associated with GC cessation required longer regimes of GC and tapering strategies but remained free of symptoms and specific treatment in the long term.

De novo arthropathy may occur following GC for SAH. Close monitoring and tapering regimes are advised.

Core Tip: Despite most adverse events following glucocorticoid (GC) administration for severe alcohol-associated hepatitis (SAH) are well-known, joint symptoms are overlooked and not mentioned in hepatology literature. We report a series of five patients, selected from a prospective cohort of patients with biopsy-proven SAH, who developed joint symptoms following GC cessation. Although the final diagnosis varied among patients, the emergence of joint symptoms after GC therapy for SAH represents a novel and noteworthy observation for clinicians managing these cases. In this report we hypothesize that some patients suffered from GC withdrawal syndrome, and we describe the therapeutic approach used.

- Citation: Herms Q, Torres S, Kamath PS, Gratacós-Ginès J, Pose E. De novo arthropathy following glucocorticoid treatment for severe alcohol-associated hepatitis: Five case reports. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 110931

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/110931.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.110931

Alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH) is the most severe form of alcohol-associated liver disease. It often presents as a subacute or acute liver failure in patients with chronic and excessive alcohol consumption and underlying liver disease[1]. Despite advances in supportive care, AH continues to carry a high short-term mortality rate, particularly in cases classified as severe based on established prognostic scoring systems such as the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and the modified Maddrey’s discriminant function (mDF)[1]. In severe AH (SAH) cases, which are those with a MELD ≥ 21 or mDF > 32, medical management typically involves the administration of systemic glucocorticoids (GC). GC are currently the only recommended pharmacologic treatment shown to improve survival[2]. The primary rationale for their use is the suppression of the profound inflammatory response believed to contribute to hepatic injury in AH. However, GC are associated with a survival benefit that is maintained only during the first month[3]. Furthermore, some patients taking GC may develop adverse events, including severe infections, metabolic disturbances, and musculoskeletal complications[4]. Among these, musculoskeletal manifestations are less frequently recognized or reported in the context of AH management.

Treatment with high doses of GC in non liver-related diseases followed by rapid tapering has been linked to exacerbation of pre-existing joint conditions[5]. This complication is thought to result from both the immunomodulatory effects of corticosteroids and the abrupt changes in systemic steroid levels, potentially unmasking subclinical inflammatory conditions or triggering new inflammatory pathways. In this case series, we aim to address this gap by describing a series of patients with SAH who developed joint manifestations following GC therapy. Our goal is to raise awareness among clinicians managing AH of this underrecognized complication.

This is a case series of patients (n = 5) with SAH (MELD ≥ 21 and/or mDF > 32) presenting with joint symptoms after GC cessation between June 2019 and May 2023. These patients were selected from an ongoing prospective cohort of patients with alcohol-associated liver disease who underwent liver biopsy for diagnostic purposes and were prospectively followed at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona (the LiverModel cohort). This cohort has been comprehensively detailed in prior publications[6]. All research was conducted in accordance with both the Declaration of Helsinki and Istanbul. From the total cohort, 52 patients with SAH were treated with GC during the study period. Five (9.6%) patients developed joint symptoms following GC withdrawal. Baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the five patients included in this case series are summarized in Table 1.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | |

| Age (years) | 64 | 38 | 53 | 56 | 44 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Male | Female | Male |

| AST/ALT (IU/L) | 57/27 | 91/34 | 390/115 | 115/44 | 306/90 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.7 | 6.4 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 20.1 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 21 | 25 | 35 | 27 | 33 |

| INR | 1.85 | 1.73 | 1.33 | 2.31 | 1.19 |

| MELD score | 18 | 20 | 19 | 25 | 20 |

| Maddrey DF | 43 | 45 | 33 | 81 | 34 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.40 | < 0.4 | < 0.4 | < 0.4 | < 0.4 |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 69 | - | 9 | 36 | 20 |

| Clinical complications of liver disease | Jaundice; moderate ascites; respiratory infection | Jaundice; moderate ascites; urinary tract infection | Jaundice; mild ascites | Jaundice; moderate ascites; variceal bleeding; hepatic encephalopathy | Jaundice; mild ascites |

| Steroid posology for AH | Initial: PRED 40 mg/24 hours for 7 days | Initial: PRED 40 mg/24 hours for 28 days | Initial: PRED 40 mg/24 hours for 2 months1 | Initial: PRED 40 mg/24 hours for 7 days | Initial: PRED 40 mg/24 hours for 28 days |

| Tapering: 10 mg every 48 hours | Tapering: 10 mg every week | Tapering: 10 mg every week | Tapering: No tapering | Tapering: 10 mg every week | |

| Response (Lille score) | Non-responder (0.585) | Responder (0.052) | Responder (0.030) | Non-responder (0.534) | Responder (0.070) |

| Joint manifestations | Soreness in both shoulders; no swelling; morning stiffness and functional disability | Symmetric soreness and pain in shoulders, knees and IPH/MCPH joints; no swelling; morning stiffness and functional disability | Symmetric soreness and pain in shoulders, hips and IPH/MCPH joints; IPH/MCPH swelling; morning stiffness and functional disability | Pain in both shoulders and knees; no swelling; morning stiffness and functional disability | Symmetric soreness in shoulders, hips and knees; no swelling; no stiffness or functional disability |

| Ultrasound findings | Subscapularis tendinopathy | Unremarkable | Bilateral tenosynovitis in flexor hand muscles and synovial hypertrophy in MTPH joints | Left shoulder: Supraspinatus and subscapularis tendinopathy; right shoulder: Unremarkable | Unremarkable |

| Final diagnosis of joint disease | Polymyalgia rheumatica | Arthralgia associated with glucocorticoid cessation | Psoriatic arthritis | Arthralgia associated with glucocorticoid cessation | Arthralgia associated with glucocorticoid cessation |

| Treatment of joint disease | Initial: Oral mPSL 12 mg/24 hours | Initial: Oral mPSL 8 mg/24 hours | Initial: Oral mPSL 8 mg/24 hours | No treatment | Initial: Oral mPSL 10 mg/24 hours |

| Maintenance: MPSL 3 mg/24 hours | Maintenance: No treatment | Maintenance: Adalimumab 40 mg/2 weeks | Maintenance: No treatment |

Case 1: A 64-year-old female presented with soreness in both shoulders.

Case 2: A 38-year-old female reported symmetric soreness and pain in both shoulders, knees, and the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints.

Case 3: A 53-year-old male experienced symmetric soreness and pain in both shoulders, hips, and the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints.

Case 4: A 56-year-old female complained of pain in both shoulders and knees.

Case 5: A 44-year-old male presented with symmetric soreness in the shoulders, hips, and knees.

Case 1: The patient reported a gradual onset of bilateral shoulder soreness, accompanied by morning stiffness, approximately 10 days after GC withdrawal. She noted difficulty performing daily activities such as combing her hair or brushing her teeth.

Case 2: The symmetric soreness and pain in multiple joints was associated with morning stiffness and functional limitations. Symptoms began 4 days after GC withdrawal. She was unable to perform basic tasks such as opening a capped water bottle or writing.

Case 3: Starting on the day after GC withdrawal, the patient reported a gradual onset of increasing soreness and pain, accompanied by pronounced morning stiffness and reduced functionality. For example, he experienced difficulty getting out of bed and standing up.

Case 4: The patient reported bilateral shoulder and knee pain, morning stiffness, and impaired daily function. Symptoms began 1 week after GC withdrawal.

Case 5: The onset of proximal joint soreness developed gradually over the course of two weeks following GC withdrawal. The patient did not report any disability or additional symptoms.

Case 1: The patient presented to the emergency department with jaundice and moderate (grade II) ascites. A diagnosis of AH was confirmed following histopathological examination of a transjugular liver biopsy. The MELD and Maddrey scores were 18 and 43, respectively. She was also diagnosed with a respiratory infection and treated with antibiotics for one week. Two days after initiating antibiotic therapy, and after additional infections were ruled out, she was started on the recommended regimen of prednisone 40 mg daily for seven days. Based on a day-7 Lille score of 0.585, indicating lack of response, prednisone was tapered by 10 mg every other day.

Case 2: The patient presented to the emergency department with jaundice and moderate (grade II) ascites. A diagnosis of AH was confirmed following histopathological examination of a transjugular liver biopsy. The MELD and Maddrey scores were 20 and 45, respectively. She was also diagnosed with a urinary tract infection and treated with antibiotics for one week. In addition, she was started on the recommended regimen of prednisone 40 mg daily for seven days. Based on a day-7 Lille score of 0.052, indicating GC response, prednisone 40 mg daily was continued for 28 days. On day 29, tapering by 10 mg per week was initiated.

Case 3: The patient presented to the emergency department with jaundice. Mild ascites (grade I) was observed on abdominal ultrasound. A diagnosis of AH was confirmed following histopathological examination of a transjugular liver biopsy. The MELD and Maddrey scores were 19 and 33, respectively. He was started on the recommended regimen of prednisone 40 mg daily for seven days. Based on a day-7 Lille score of 0.030, indicating GC response, prednisone 40 mg daily was continued for 28 days. However, due to a misunderstanding, the patient continued the medication for two months. After that period, tapering by 10 mg per week was initiated.

Case 4: The patient presented to the emergency department with jaundice, moderate (grade II) ascites, melena, and a flapping tremor, consistent with AH associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed esophageal variceal bleeding, which was treated with band ligation. The diagnosis of AH was confirmed following histopathological examination of a transjugular liver biopsy performed shortly thereafter. The MELD and Maddrey scores were 25 and 81, respectively. After ruling out bacterial infections, she was started on the recommended regimen of prednisone 40 mg daily for seven days. Based on a day-7 Lille score of 0.534, indicating lack of response, prednisone was abruptly discontinued.

Case 5: The patient presented to the emergency department with jaundice. Mild ascites (grade I) was observed on abdominal ultrasound. A diagnosis of AH was confirmed following histopathological examination of a transjugular liver biopsy. The MELD and Maddrey scores were 20 and 34, respectively. He was started on the recommended regimen of prednisone 40 mg daily for seven days. Based on a day-7 Lille score of 0.070, indicating GC response, prednisone 40 mg daily was continued for 28 days. On day 29, tapering by 10 mg per week was initiated.

The reason for the different discontinuation regimen in non-responders was related to the preference of their attending physicians.

Case 1: The patient was a former smoker and consumed approximately 80 g of alcohol daily. She had no personal or family history of rheumatic, autoimmune, or other relevant diseases.

Case 2: The patient consumed an average of approximately 130 g of alcohol per day. She had no personal or family history of rheumatic or autoimmune diseases. She had undergone sleeve gastrectomy five years prior to admission.

Case 3: The patient consumed an average of approximately 200 g of alcohol per day. Notably, he had long-standing psoriasis treated with topical steroids only. He had not reported any joint manifestations prior to receiving oral GC for SAH.

Case 4: The patient was a former smoker and consumed approximately 180 g of alcohol daily. She had no personal or family history of rheumatic, autoimmune, or other relevant diseases.

Case 5: The patient was a daily smoker (one pack of cigarettes per day) and consumed approximately 60-70 g of alcohol daily. He had no personal or family history of rheumatic, autoimmune, or other relevant diseases.

Case 1: Unremarkable.

Case 2: On examination, tenderness of the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints was noted; however, no swelling was observed.

Case 3: On examination, tenderness and swelling of interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints were noted.

Case 4: Unremarkable.

Case 5: Unremarkable.

Case 1: Inflammatory markers, particularly Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), were elevated in this patient.

Case 2: C-reactive protein (CRP) was within normal range.

Case 3: CRP and ESR were within normal range.

Case 4: CRP was within normal range. ESR was slightly elevated.

Case 5: CRP was within normal range. ESR was slightly elevated.

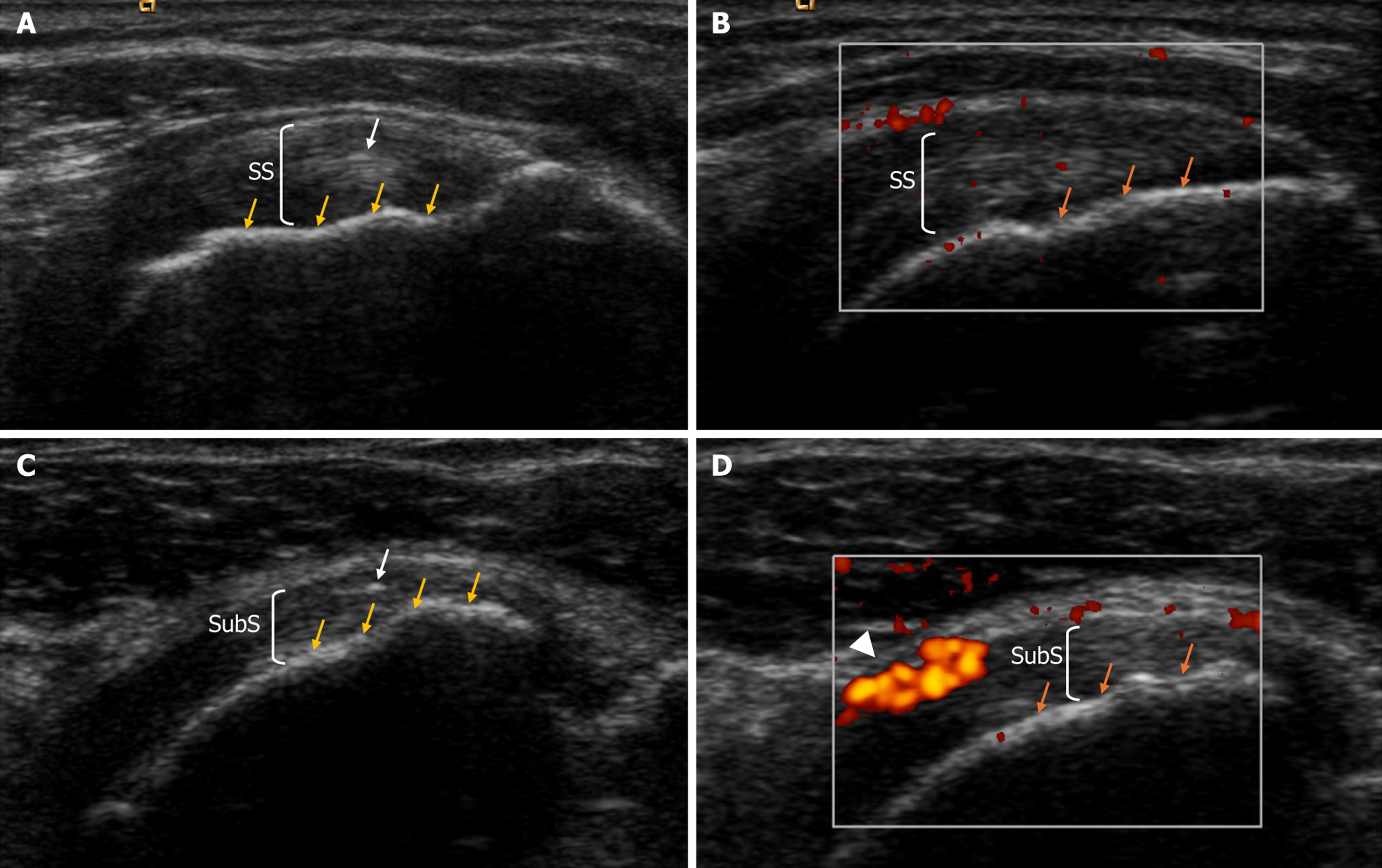

Case 1: Ultrasound examination revealed no joint or enthesis inflammation, nor any bone damage. However, ultrasonographic signs of unilateral subscapularis tendinopathy were observed.

Case 2: Ultrasound examination revealed no joint or enthesis inflammation, nor any bone damage.

Case 3: Ultrasound examination revealed bilateral hand flexors tenosynovitis and synovial hypertrophy in metacarpophalangeal joints.

Case 4: Ultrasound examination revealed no joint or enthesis inflammation, nor any bone damage. However, ultrasonographic signs of unilateral supraspinatus and subscapularis tendinopathy were observed (Figure 1).

Case 5: Ultrasound examination revealed no joint or enthesis inflammation, nor any bone damage.

All patients were referred to the Rheumatology Clinics.

Polymyalgia rheumatica. This patient was initially diagnosed with tendinitis given the ultrasound findings, but was later initiated on GC due to the absence of improvement with standard treatment. She rapidly resolved all symptoms; however, symptoms resumed after discontinuation of GC. Therefore, she was ultimately diagnosed with polymyalgia rheumatica de novo.

Arthralgia associated with GC cessation. Other diagnoses were ruled out based on the absence of arthritis on physical examination and ultrasound, lack of bone damage on X-rays, and negative serological tests for rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies.

Psoriatic arthritis.

Arthralgia associated with GC cessation. Other diagnoses were ruled out based on the absence of arthritis on physical examination and ultrasound, lack of bone damage on X-rays, and negative serological tests for rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies.

Arthralgia associated with GC cessation. Other diagnoses were ruled out based on the absence of arthritis on physical examination and ultrasound, lack of bone damage on X-rays, and negative serological tests for rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies.

She was treated with methylprednisolone 12 mg daily, which was gradually tapered to discontinuation. However, her symptoms quickly recurred, and she was started on long-term low-dose therapy (3 mg daily).

She required resumption of GC to control her symptoms. A longer and more gradual tapering regimen than that used for SAH was implemented.

He initially required resumption of GC to control his symptoms. However, due to the chronic and inflammatory nature of psoriatic arthritis, he was subsequently started on adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist.

No treatment was administered. Her symptoms improved gradually and ultimately resolved spontaneously.

He required resumption of GC to control his symptoms. A longer and more gradual tapering regimen than that used for SAH was implemented.

The patient is asymptomatic, and her disease is controlled with low-dose GC therapy. Regarding her liver disease, she experienced progressive improvement in liver tests and resolution of clinical complications following alcohol abstinence. She was alive at the end of follow-up.

The symptoms resolved after a few weeks of GC and the patient remained steroid-free at the end of follow-up. Regarding her liver disease, she experienced progressive improvement in liver tests and resolution of clinical complications following alcohol abstinence. She was alive at the end of follow-up.

The patient received adalimumab up to the date of last follow-up. He is asymptomatic, and follow-up ultrasounds showed no signs of disease progression. Regarding his liver disease, he experienced progressive improvement in liver tests and resolution of clinical complications following alcohol abstinence. He was alive at the end of follow-up.

The symptoms resolved spontaneously and have not recurred. Regarding her liver disease, she experienced progressive improvement in liver tests and resolution of clinical complications following alcohol abstinence. She was alive at the end of follow-up.

The symptoms resolved after a few weeks of GC and the patient remained steroid-free at the end of follow-up. Regarding his liver disease, he experienced progressive improvement in liver tests and resolution of clinical complications following alcohol abstinence. However, he resumed alcohol consumption several months after being discharged and subsequently presented to the hospital with a recurrent AH. The recurrent episode was non-severe and thus did not require GC. He did not develop joint symptoms after the recurrent episode. The patient was alive at the end of follow-up.

In this study, we report a series of patients with SAH who developed joint manifestations following steroid cessation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of such complications in this setting. GC are indicated in many inflammatory conditions and their efficacy results from the pleiotropic effects of the GC receptor on multiple signaling pa

Additionally, high doses of GC during long periods may inhibit the production of endogenous corticosteroids via suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Abrupt cessation or rapid tapering in this situation may lead to insufficient cortisol levels, causing similar symptoms to adrenal insufficiency, such as fatigue or joint soreness[8]. This clinical scenario is known as corticosteroid withdrawal syndrome (CWS). CWS has been reported in several conditions requiring high doses of steroids, such as ulcerative colitis, vasculitis, lymphoma, and various cancers[9-11]. In these prior reports, joint pain and soreness were among the most common symptoms, appearing between day 3 after starting GC tapering and day 6 after complete discontinuation[10]. In patients with diseases affecting the joints, such as rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis, this has not been described as a distinct or common entity, likely because symptoms fol

Our study is a small case series from a single center; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to broader patient populations or other settings. Additionally, cumulative incidence and risk factors for this complication could not be assessed. The aim of this report is to raise awareness of this overlooked complication among clinicians managing patients with AH.

Joint manifestations as exacerbation of previous joint diseases, de novo polymyalgia rheumatica or CWS may develop after GC cessation in patients with AH. Close follow-up and regimes including tapering and slow dose-reduction should be considered in these patients.

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;69:154-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 636] [Cited by in RCA: 648] [Article Influence: 81.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bataller R, Arab JP, Shah VH. Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2436-2448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Louvet A, Thursz MR, Kim DJ, Labreuche J, Atkinson SR, Sidhu SS, O'Grady JG, Akriviadis E, Sinakos E, Carithers RL Jr, Ramond MJ, Maddrey WC, Morgan TR, Duhamel A, Mathurin P. Corticosteroids Reduce Risk of Death Within 28 Days for Patients With Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis, Compared With Pentoxifylline or Placebo-a Meta-analysis of Individual Data From Controlled Trials. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:458-468.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Waljee AK, Rogers MA, Lin P, Singal AG, Stein JD, Marks RM, Ayanian JZ, Nallamothu BK. Short term use of oral corticosteroids and related harms among adults in the United States: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Maassen JM, Dos Santos Sobrín R, Bergstra SA, Goekoop R, Huizinga TWJ, Allaart CF. Glucocorticoid discontinuation in patients with early rheumatoid and undifferentiated arthritis: a post-hoc analysis of the BeSt and IMPROVED studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1124-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Avitabile E, Díaz A, Montironi C, Pérez-Guasch M, Gratacós-Ginès J, Hernández-Évole H, Moreira RK, Sehrawat TS, Malhi H, Olivas P, Hernández-Gea V, Bataller R, Shah VH, Kamath PS, Ginès P, Pose E. Adding Inflammatory Markers and Refining National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Criteria Improve Diagnostic Accuracy for Alcohol-associated Hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:3080-3088.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zabotti A, De Marco G, Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Aletaha D, Iagnocco A, Gisondi P, Balint PV, Bertheussen H, Boehncke WH, Damjanov NS, de Wit M, Errichetti E, Marzo-Ortega H, Protopopov M, Puig L, Queiro R, Ruscitti P, Savage L, Schett G, Siebert S, Stamm TA, Studenic P, Tinazzi I, Van den Bosch FE, van der Helm-van Mil A, Watad A, Smolen JS, McGonagle DG. EULAR points to consider for the definition of clinical and imaging features suspicious for progression from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:1162-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hopkins RL, Leinung MC. Exogenous Cushing's syndrome and glucocorticoid withdrawal. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2005;34:371-384, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Priori R, Tomassini M, Magrini L, Conti F, Valesini G. Churg-Strauss syndrome during pregnancy after steroid withdrawal. Lancet. 1998;352:1599-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saracco P, Bertorello N, Farinasso L, Einaudi S, Barisone E, Altare F, Corrias A, Pastore G. Steroid withdrawal syndrome during steroid tapering in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a controlled study comparing prednisone versus dexamethasone in induction phase. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Margolin L, Cope DK, Bakst-Sisser R, Greenspan J. The steroid withdrawal syndrome: a review of the implications, etiology, and treatments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:224-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/