Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.110312

Revised: July 1, 2025

Accepted: November 17, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 197 Days and 20.5 Hours

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is characterized by inflammation, hepatocyte nec

To compare the presentation and progression of AIH in patients diagnosed before and after the age of 60 years.

This cross-sectional analytical study included biopsy-confirmed AIH patients with at least one year of follow-up at Hospital Clínico Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile. Demographic, clinical, laboratory, and treatment response variables were analyzed. Group comparisons (diagnosis before or after 60 years) were performed using the χ2 test for qualitative variables and the Mann-Whitney test for quan

Ninety-seven AIH patients were included; 85% were female, with a median age of 53 years (range 18-83 years). Forty-one percent were diagnosed after the age of 60. Younger patients exhibited more jaundice at diagnosis (75% vs 44%, P = 0.02) and higher aminotransferases levels (median alanine aminotransferase 998 IU/mL vs 334 IU/mL, P = 0.0002). In contrast, at diagnosis, ascites was more prevalent in patients over 60 (13% vs 2%, P = 0.028), and advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) was more frequent in this group (68% vs 41%, P = 0.020). Biochemical response at six months was similar between groups, despite lower corticosteroid doses being admini

AIH in patients over 60 presented with less jaundice, lower aminotransferases levels, greater fibrosis, and more ascites. Biochemical response was similar independently of age and despite lower prednisone doses administered in patients over 60 years.

Core Tip: This study highlights age-related differences in autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) presentation. Patients diagnosed after 60 years of age showed milder biochemical abnormalities but more advanced fibrosis and ascites at diagnosis. Despite receiving lower corticosteroid doses, their treatment response was comparable to younger patients. These findings suggest that AIH in older adults may represent a distinct clinical phenotype with important diagnostic and therapeutic implications.

- Citation: Delgado J, Fuentes M, Simian D, Poniachik J, Urzúa Á. Impact of age on autoimmune hepatitis: A comparative study of patients diagnosed before and after sixty. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 110312

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/110312.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.110312

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an immune-mediated disease characterized by the presence of circulating autoantibodies, increased immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentration, and distinctive histological features. It is believed to result from the loss of immunological tolerance to hepatic cells triggered by environmental factors in genetically predisposed individuals[1].

The estimated prevalence in the United States is 31.2/100000 inhabitants, comparable to reports from Europe[2]. AIH affects individuals of all ages, genders, and ethnicities[3]. Most studies describe a bimodal age distribution, with peaks at 30 years and again after 60 years. Due to rising life expectancy, AIH diagnoses are becoming more common among older adults.

AIH presents with a wide clinical spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic cases to acute liver failure[4]. In older adults, the disease often follows an insidious course and is frequently diagnosed at more advanced stages[5,6]. While previous studies have described the clinical characteristics of elderly AIH patients, these cohorts have generally used higher age cutoffs (≥ 65 years or ≥ 70 years), involved predominantly European populations, and been conducted in referral centers with distinct diagnostic and therapeutic standards. A study from Latin America[7] has also described the clinical features of AIH in the region; however, it did not focus specifically on age-related differences nor compare younger and older subgroups within the same cohort. In contrast, our study examines a Latin American population stratified by age ≥ 60 years, providing one of the largest series of elderly AIH patients reported in the region. By employing a different age cutoff and a structured age-based comparison, our analysis identifies differences in clinical presentation, fibrosis severity, treatment regimens, and therapeutic outcomes, offering contextually relevant insights for clinical decision-making in similar healthcare settings.

The aim of this study was to compare the presentation and progression of AIH in patients diagnosed before and after the age of 60 years.

This was a retrospective, observational, and analytical study involving a review of medical records of patients diagnosed with AIH based on the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group criteria[8]. Inclusion criteria comprised biopsy-confirmed AIH diagnosis between February 2012 and March 2022, and a minimum follow-up of 12 months at Hospital Clínico Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile. Eligible patients were identified through the hospital’s electronic registry of outpatient and hospitalized AIH cases.

Demographic (age and gender), clinical (comorbidities, AIH presentation type, and characteristics), laboratory (liver profile, platelets, albumin, IgG, autoantibodies, liver biopsy), treatment, and response variables, defined as normalization of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and IgG levels at 6 months of treatment[9], were collected from the medical records.

No imputation was performed for missing data. Patients with incomplete records for key variables were excluded from the corresponding analyses. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and histograms. Parametric variables were described using mean and standard deviation, while non-parametric variables were presented as median and range. Group comparisons (age at diagnosis: Younger or older than 60 years) were performed using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t-tests or Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables, depending on the data distribution. P < 0.05 was considered statistically signi

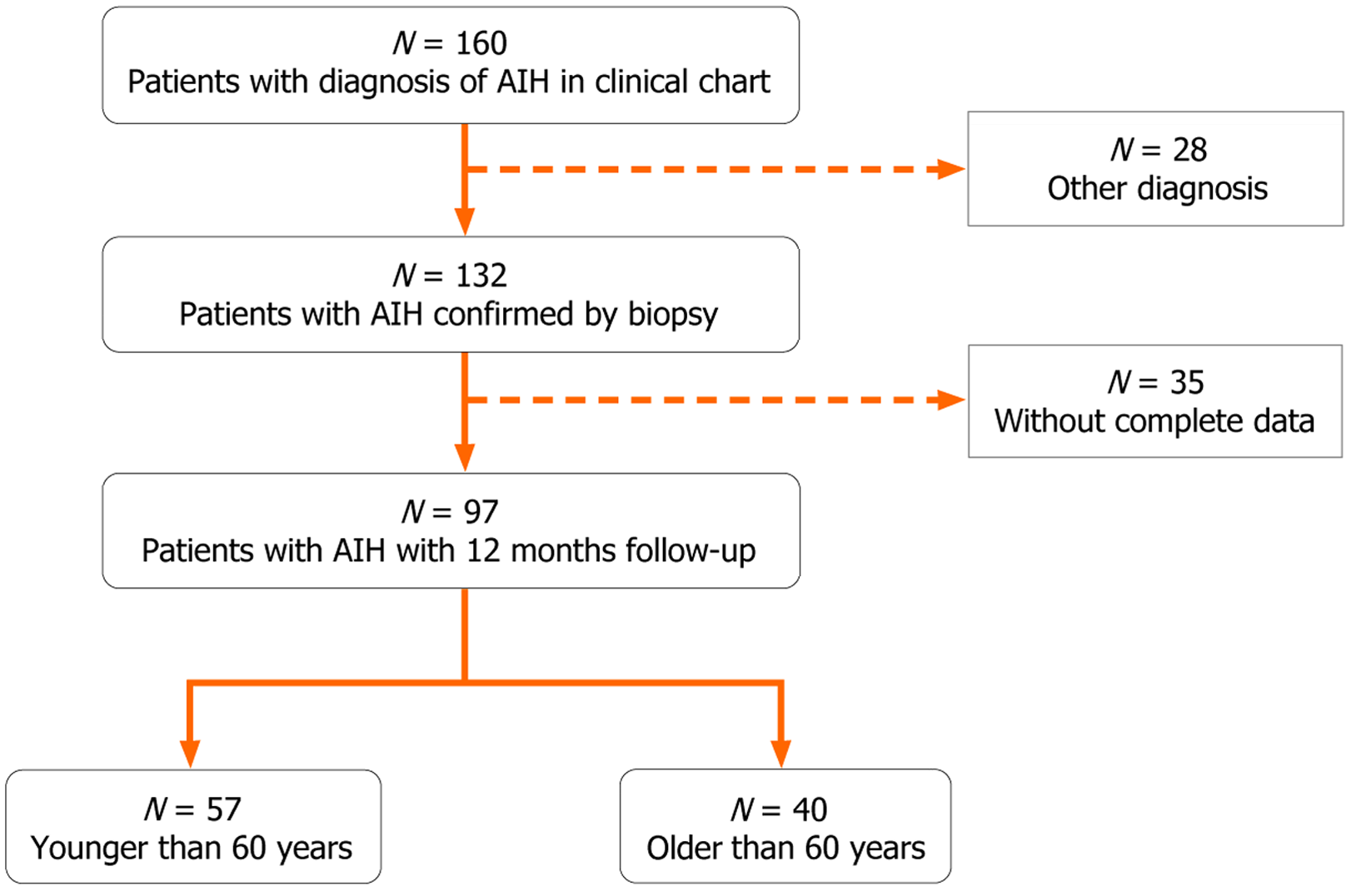

Medical records of 132 AIH patients diagnosed between February 2012 and March 2022 were reviewed. Of these, 97 patients had at least 12 months of follow-up at the hospital and were included in the analysis. Fifty-seven patients (59%) were diagnosed before the age of 60, and 40 patients (41%) were diagnosed at or after 60 years (Figure 1).

Eighty-five percent of patients were female, with a median sample age of 53 years (range 19-83 years). Patients dia

| Younger than 60 years (n = 57) | Older than 60 years (n = 40) | P value | |

| Age (years) [median (interquartile range)] | 45 (18-59) | 66 (60-83) | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.058 | ||

| Female | 52 (91) | 31 (77) | |

| Male | 6 (9) | 9 (23) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 8 (14) | 14 (35) | 0.015 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | 0.006 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 4 (7) | 9 (23) | 0.028 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | - |

| Malignancy | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | - |

| Hypothyroidism | 16 (28) | 11 (27) | 0.951 |

| Dyslipidemia | 7 (12) | 6 (15) | 0.699 |

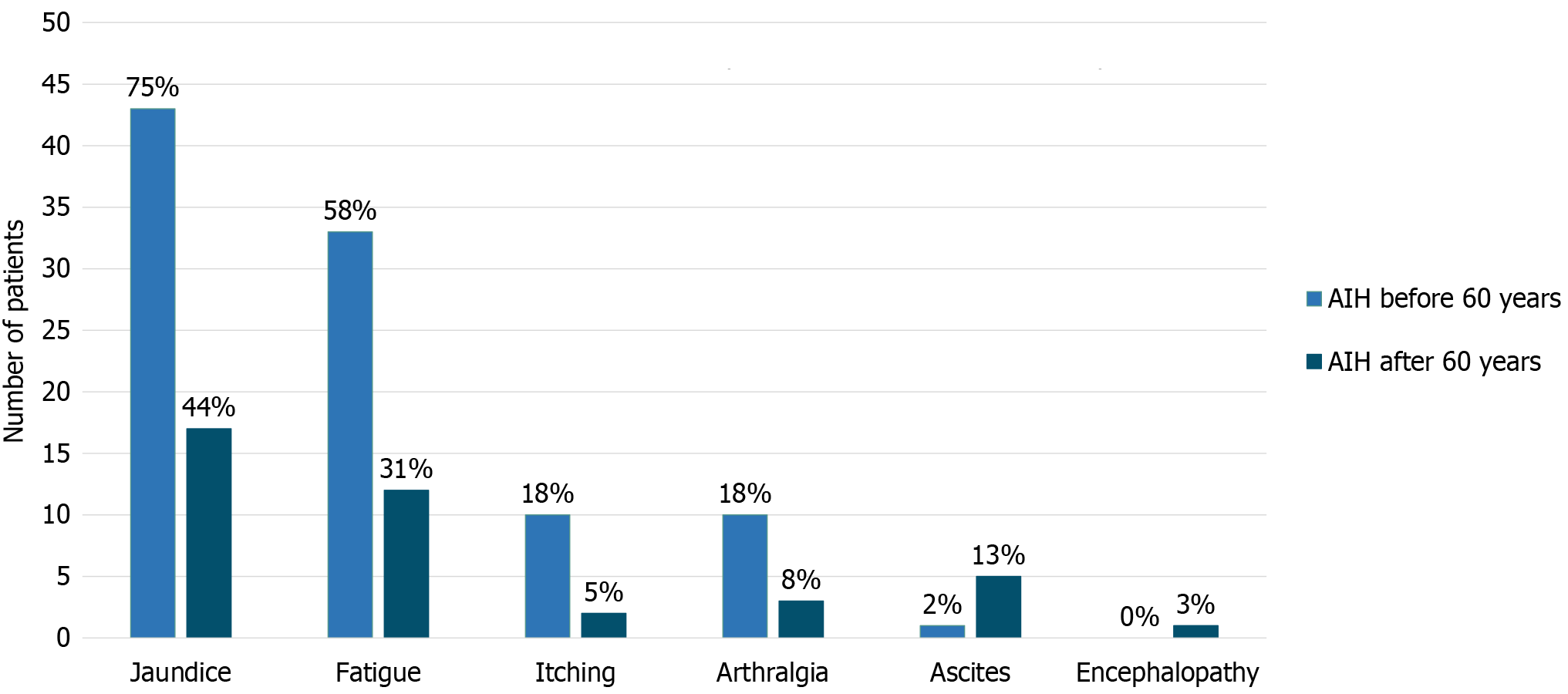

A higher proportion of younger patients presented with jaundice (75% vs 44%, P = 0.002; Figure 2) and had higher bilirubin and aminotransferases levels [bilirubin 4.7 mg/dL (range 2.5-7.8 mg/dL) vs 1.8 mg/dL (range 1.1-6.7 mg/dL), P = 0.022; ALT 998 U/L (range 464-1438 U/L) vs 334 U/L (range 76-770 U/L), P = 0.0002 and AST 1016 U/L (range 581-1301 U/L) vs 299 U/L (range 100-746 U/L), P = 0.0008] (Table 2). Conversely, ascites was more prevalent in patients over 60 (13% vs 2%, P = 0.028). No significant differences were observed in the type of AIH presentation (asymptomatic, insi

| Younger than 60 years (n = 57) | Older than 60 years (n = 40) | P value | |

| Type of presentation of autoimmune hepatitis | 0.391 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 8 (14) | 10 (25) | |

| Insidious | 25 (44) | 15 (37.5) | |

| Acute | 24 (42) | 15 (37.5) | |

| Debut symptoms | |||

| Jaundice | 43 (75) | 17 (44) | 0.002 |

| Fatigue | 33 (58) | 12 (31) | 0.009 |

| Pruritus | 10 (18) | 2 (5) | 0.071 |

| Arthralgia | 10 (18) | 3 (8) | 0.156 |

| Ascites | 1 (2) | 5 (13) | 0.028 |

| Encephalopathy | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | - |

| Laboratory at diagnosis [median (interquartile range)] | |||

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 1016 (581-1301) | 299 (100-746) | 0.0008 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 998 (464-1438) | 334 (76-770) | 0.0002 |

| Alkaline phosphatases | 196 (146-254) | 258 (143-394) | 0.475 |

| Total bilirubin | 4.7 (2.5-7.8) | 1.8 (1.1-6.7) | 0.022 |

| Albumin | 3.7 (3.3-4.2) | 3.4 (3.2-3.9) | 0.128 |

| Serology at diagnosis | |||

| Immunoglobulin G [median (interquartile range)] | 2020 (1740-2380) | 1810 (1410-2440) | 0.198 |

| Anti-nuclear antibodies (positive) | 48 (87) | 35 (92) | 0.460 |

| Anti-smooth muscle antibodies (positive) | 33 (60) | 23 (59) | 0.920 |

| Hepatic biopsy | |||

| Presence of fibrosis | 37 (65) | 37 (93) | 0.002 |

| Advanced fibrosis F3-F4 | 15 (41) | 25 (68) | 0.020 |

| Prednisone doses | < 0.001 | ||

| Without prednisone | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | |

| 10-20 mg | 0 (0) | 10 (25) | |

| 20-40 mg | 16 (28) | 12 (30) | |

| 40-60 mg | 41 (72) | 16 (40) | |

| Pharmacological treatment at 6 months | - | ||

| Without prednisone | 0 | 2 | |

| Prednisone only | 0 | 0 | |

| Prednisone + azathioprine | 55 | 32 | |

| Prednisone + mycophenolate | 2 | 5 | |

| Prednisone + tacrolimus | 0 | 1 |

Liver biopsy findings showed greater advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) in patients diagnosed after 60 years (68% vs 41%, P = 0.020). Treatment outcomes revealed no significant differences in achieving complete biochemical response at six months. However, older patients achieved this response with lower prednisone doses (Table 3).

| Younger than 60 years (n = 57) | Older than 60 years (n = 40) | P value | |

| Aminotransferases | |||

| Normalization at 6 months | 26 (46) | 17 (43) | 0.761 |

| Normalization at 12 months | 42 (74) | 29 (70) | 0.690 |

| Time to normalization (months) [median (IQR)] | 6 (4-10) | 6 (4.5-8) | 0.799 |

| Immunoglobulin G | |||

| Normalization at 6 months | 38 (67) | 20 (56) | 0.440 |

| Time to normalization (months) [median (IQR)] | 5 (3-7) | 4.5 (2.5-7) | 0.960 |

AIH is a highly heterogeneous disease, with an extremely broad age spectrum ranging from young adulthood to older ages. Indeed, AIH may even present for the first time in individuals in their eighties[10]. Our study found that 41% of patients were diagnosed after the age of 60 years, a proportion similar to other reports indicating that AIH often mani

AIH can follow a very mild subclinical course, present insidiously, or manifest acutely, although acute liver failure is rare[10]. In our study, we did not find significant differences in the type of presentation between age groups. This contrasts with prior reports, particularly from European cohorts in which elderly patients more frequently exhibited an insidious onset[6]. One possible explanation is a higher detection rate of asymptomatic cases among older adults in our setting, who are more likely to undergo routine testing for comorbidities such as hypertension, hypothyroidism and diabetes. Additionally, our institution is a national referral center, with access to liver transplantation and a high com

Regarding liver function tests, younger patients had significantly higher aminotransferases levels at diagnosis compared to older patients. One hypothesis for this difference is that younger patients may have a greater enzymatic expression in hepatocytes, which could explain the higher enzyme release in the absence of significant fibrosis[11]; indeed, older patients usually have lower ALT levels[12] which are associated to higher all-cause mortality. Low levels of aminotransferases have been associated with a higher degree of liver fibrosis, consistent with the results of our study, where older patients presented more fibrosis and ascites. This may be due to a longer duration of disease progression before diagnosis. Additionally, the aging process itself might contribute to increased fibrosis, as cellular senescence leads to impaired hepatic regeneration and a shift towards fibrogenesis, even in the absence of underlying liver disease[13]. In addition, this group had more chronic conditions than younger patients did, particularly hypertension and T2DM, diseases that are associated with advanced liver fibrosis/cirrhosis, in particular in AIH[14].

Complete biochemical response was similar in both groups. However, the steroid doses required for this outcome, were lower in the elderly. A possible biological explanation is the immune senescence, a process in which aging induces complex changes in both innate and adaptive immune responses, potentially reducing the inflammatory activity of AIH and modifying treatment responsiveness[15]. This phenomenon has been described in other autoimmune diseases; for example, the GLORIA study recently demonstrated that low doses of corticosteroids were effective in controlling disease activity in patients over 65 years of age with rheumatoid arthritis[16]. An alternative hypothesis is that lower corticosteroids doses may be equally effective in inducing biochemical remission regardless of age. This is supported by retrospective data showing no significant differences in aminotransferase normalization between patients receiving prednisone < 0.5 mg/kg/day and those receiving higher doses[17]. Taken together, these observations suggest that age-adjusted corticosteroid dosing could be considered in future treatment guidelines, particularly in older adults with com

The management of AIH in older patients is particularly challenging due to the higher risk of corticosteroid-associated complications in this group, including fractures and decompensation of chronic disease in this group, which are also more frequent[18,19]. Regardless of age, systematic reviews confirm the efficacy and safety of standard induction therapy with corticosteroids as the first-line treatment for AIH[20]. Nevertheless, in older patients, the use of lower corticosteroid doses may be a prudent strategy to mitigate adverse effects. Unfortunately, in our study, adverse effects were not con

The retrospective nature and single-center setting of this study may limit the generalizability of its findings. Furthermore, the exclusion of patients who underwent liver biopsy at our institution but continued follow-up elsewhere resulted in a reduced sample size. Another important limitation is the lack of systematic data collection regarding corticosteroid-related adverse effects, particularly in the elderly, where this issue is highly relevant clinically. Future prospective studies should incorporate standardized reporting of treatment-related complications to better assess the risk-benefit balance of lower steroid dosing strategies in older AIH patients.

In conclusion, we describe a cohort of AIH patients in which those diagnosed after the age of 60 presented with milder biochemical abnormalities but more advanced fibrosis and a higher prevalence of ascites. Despite these differences, their treatment response was comparable to that of younger patients, even with lower doses of prednisone.

| 1. | Muratori L, Lohse AW, Lenzi M. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. BMJ. 2023;380:e070201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tunio NA, Mansoor E, Sheriff MZ, Cooper GS, Sclair SN, Cohen SM. Epidemiology of Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH) in the United States Between 2014 and 2019: A Population-based National Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:903-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN, Kerkar N, Manns MP, Mayo MJ, Vierling JM, Alsawas M, Murad MH, Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children: 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;72:671-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 647] [Article Influence: 107.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang Q, Yang F, Miao Q, Krawitt EL, Gershwin ME, Ma X. The clinical phenotypes of autoimmune hepatitis: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2016;66:98-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Granito A, Muratori L, Pappas G, Muratori P, Ferri S, Cassani F, Lenzi M, Bianchi FB. Clinical features of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in elderly Italian patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1273-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Dalekos GN, Azariadis K, Lygoura V, Arvaniti P, Gampeta S, Gatselis NK. Autoimmune hepatitis in patients aged 70 years or older: Disease characteristics, treatment response and outcome. Liver Int. 2021;41:1592-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Díaz Ramírez GS, Martínez Casas OY, Marín Zuluaga JI, Donado Gómez JH, Muñoz Maya O, Santos Sánchez O, Restrepo Gutiérrez JC. Características diferenciales de la hepatitis autoinmune en adultos mayores colombianos: estudio de cohorte. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol. 2019;34:135-143. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ, Donaldson PT, Eddleston AL, Fainboim L, Heathcote J, Homberg JC, Hoofnagle JH, Kakumu S, Krawitt EL, Mackay IR, MacSween RN, Maddrey WC, Manns MP, McFarlane IG, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Zeniya M. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2003] [Cited by in RCA: 2017] [Article Influence: 74.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pape S, Snijders RJALM, Gevers TJG, Chazouilleres O, Dalekos GN, Hirschfield GM, Lenzi M, Trauner M, Manns MP, Vierling JM, Montano-Loza AJ, Lohse AW, Schramm C, Drenth JPH, Heneghan MA; International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) collaborators(‡). Systematic review of response criteria and endpoints in autoimmune hepatitis by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol. 2022;76:841-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2025;83:453-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang M, Serna-Salas S, Damba T, Borghesan M, Demaria M, Moshage H. Hepatic stellate cell senescence in liver fibrosis: Characteristics, mechanisms and perspectives. Mech Ageing Dev. 2021;199:111572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Le Couteur DG, Blyth FM, Creasey HM, Handelsman DJ, Naganathan V, Sambrook PN, Seibel MJ, Waite LM, Cumming RG. The association of alanine transaminase with aging, frailty, and mortality. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:712-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Premoli A, Paschetta E, Hvalryg M, Spandre M, Bo S, Durazzo M. Characteristics of liver diseases in the elderly: a review. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2009;55:71-78. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Zachou K, Azariadis K, Lytvyak E, Snijders RJALM, Takahashi A, Gatselis NK, Robles M, Andrade RJ, Schramm C, Lohse AW, Tanaka A, Drenth JPH, Montano-Loza AJ, Dalekos GN; International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG). Treatment responses and outcomes in patients with autoimmune hepatitis and concomitant features of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Watad A, Bragazzi NL, Adawi M, Amital H, Toubi E, Porat BS, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmunity in the Elderly: Insights from Basic Science and Clinics - A Mini-Review. Gerontology. 2017;63:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Boers M, Hartman L, Opris-Belinski D, Bos R, Kok MR, Da Silva JA, Griep EN, Klaasen R, Allaart CF, Baudoin P, Raterman HG, Szekanecz Z, Buttgereit F, Masaryk P, Klausch LT, Paolino S, Schilder AM, Lems WF, Cutolo M; GLORIA Trial consortium. Low dose, add-on prednisolone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis aged 65+: the pragmatic randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled GLORIA trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:925-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pape S, Gevers TJG, Belias M, Mustafajev IF, Vrolijk JM, van Hoek B, Bouma G, van Nieuwkerk CMJ, Hartl J, Schramm C, Lohse AW, Taubert R, Jaeckel E, Manns MP, Papp M, Stickel F, Heneghan MA, Drenth JPH. Predniso(lo)ne Dosage and Chance of Remission in Patients With Autoimmune Hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2068-2075.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Matthewman J, Tadrous M, Mansfield KE, Thiruchelvam D, Redelmeier DA, Cheung AM, Lega IC, Prieto-Alhambra D, Cunliffe LA, Mulick A, Henderson A, Langan SM, Drucker AM. Association of Different Prescribing Patterns for Oral Corticosteroids With Fracture Preventive Care Among Older Adults in the UK and Ontario. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:961-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Compston J. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: an update. Endocrine. 2018;61:7-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 20. | Durazzo M, Lupi G, Scandella M, Ferro A, Gruden G. Autoimmune hepatitis treatment in the elderly: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:2809-2818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/