Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.110303

Revised: July 16, 2025

Accepted: November 12, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 205 Days and 22.8 Hours

The gut microbiota is of growing interest to clinicians and researchers due to its elucidating extensive role in metabolic and immune mechanisms, not only in the gut but also in other organs. The liver shares a close bidirectional relationship with the intestine and the gut microbiota. Disturbances in the composition of the gut microbiota can affect the immune systems of both the intestine and liver. In turn, bile composition also influences the gut microbiota. Disruption of this balance can arise from various causes and may significantly impact intestinal and liver health. Therefore, the aim of the current review is to discuss the biological relationships between the gut microbiota and liver function as well as the clinical significance of their disturbances.

Core Tip: The gut microbiota has numerous metabolic and immune connections not only to the gut itself but also to other organs, including the lungs, brain, and liver. The gut-liver connection is bidirectional, and disruptions in this relationship contribute to the development of various liver diseases. Modulation of gut microbiota composition and function forms the basis of therapeutic strategies for conditions such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Citation: Kotlyarov SN. Clinical and biological significance of the relationship between gut microbiota and liver disease. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 110303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/110303.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.110303

The gut microbiota is of growing interest to clinicians and researchers due to its extensive role in many physiological and pathophysiological processes. There is increasing evidence that the gut microbiota functions as a complex, regulated, multicellular “organ” involved in maintaining the body’s metabolic and immune homeostasis[1,2]. It is believed that the number of microorganisms inhabiting the intestine may even exceed the number of cells in the human body, and that the total number of genes possessed by gut microorganisms may greatly surpass the number of human genes[3,4]. The gut microbiota is composed of bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses, which are species-specific and have a complex compo

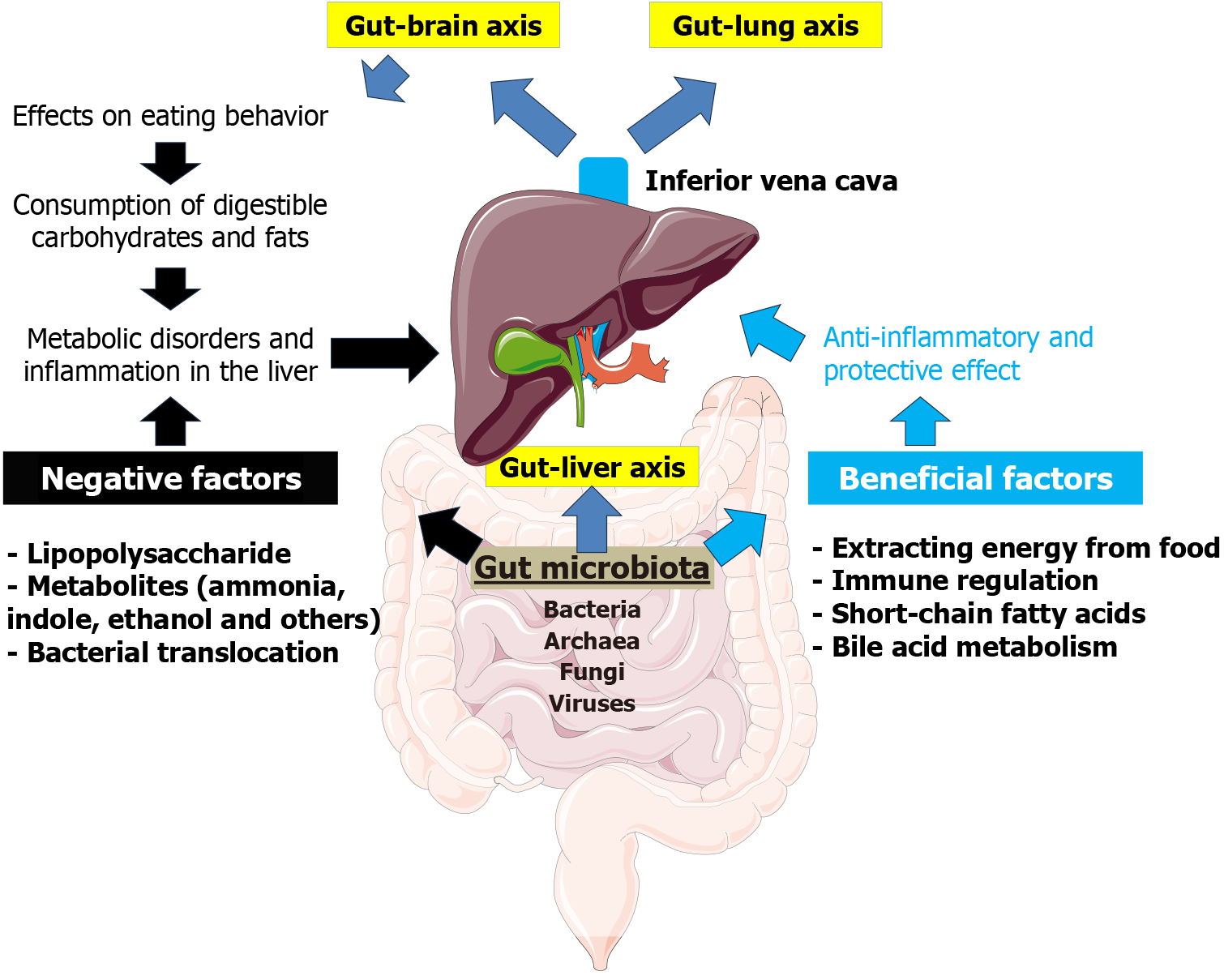

Growing evidence suggests that the gut microbiota is an integral part of the intestine’s complex interactions with other organs. Indeed, the gastrointestinal tract is one of the most evolutionarily ancient systems in the body, and its role in regulating the functions of other organs and systems is well established. In recent years, clinicians and researchers have focused on the “gut-lung”, “gut-brain”, and “gut-liver” axes, with the gut microbiota serving as a key component of these connections (Figure 1).

There is compelling evidence that the liver has a bidirectional relationship with the gut microbiota, and that dis

The gut microbiota is a complex ecosystem of microorganisms inhabiting the human digestive tract[7]. It is mainly composed of bacteria, with more than 1500 species belonging to over 50 different phyla. However, 99% of these bacteria are represented by approximately 30-40 species. The most common bacterial phyla in the human gut are Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, followed by Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria[18-21]. In addition to bacteria, the gut microbiota also includes archaea, viruses (phages), and fungi, all of which contribute to its complexity and functionality[22,23].

The composition of the human gut microbiota changes significantly throughout life due to various factors such as diet, environment, and aging. During the fetal period, the gut is sterile but is rapidly colonized with microorganisms after birth. The gut microbiota undergoes substantial changes during the first two years of life and generally stabilizes by around three years of age. This period is critical for the development of a diverse microbial community[6,24,25]. The gut microbiota has species-specific characteristics and is strongly influenced by dietary patterns. For example, studies have shown that captivity and artificial feeding can significantly alter the gut microbiota of Sichuan golden monkeys, often resulting in an increase in Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, and Tenericutes[26]. Another study found that captive primates tend to lose their natural gut microbiota and are colonized predominantly by Prevotella and Bacteroides, species commonly found in the human gut[27]. Dietary components such as fiber, amino acids, organic acids, and polyphenolic compounds can significantly affect the gut microbiota’s composition. Excessive intake of carbohydrates and fats is a key factor influencing microbiota balance. Obese individuals often have a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, which tends to decrease with weight loss, suggesting its potential role in obesity[28-30]. However, some studies have reported conflicting results, indicating that other factors, such as lifestyle and genetic predisposition, may also influence the relationship between the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and obesity[31,32]. Alterations in bacterial ratios are also characteristic of various diseases. For instance, an elevated Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is associated with ulcerative colitis. This imbalance may contribute to the onset and progression of the disease, highlighting its relevance in inflammatory responses[33,34].

Archaea are another important component of the gut microbiota. The most common archaea in the human gastroin

Fungi make up a relatively small proportion of the human gut microbiota, constituting approximately 0.03% of the fecal microbiota. They are composed mainly of three groups: Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes, and Zygomycetes[35,43]. The role of intestinal fungi in liver disease development remains largely unclear. However, altered fungal microbiota composition has been reported in patients with NAFLD. In these patients, the relative abundance of Talaromyces, Paraphaeosphaeria, Lycoperdon, Curvularia, Phialemoniopsis, Paraboeremia, Sarcinomyces, Cladophialophora, and Sordaria, as well as Leptosphaeria, Pseudopithomyces, and Fusicolla, was increased[44]. Intestinal fungi also produce various bioactive substances. For instance, the contribution of prostaglandin E2 produced by fungi to the development of alcoholic hepatic steatosis has been described[35,45]. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) exhibit significant alterations in the gut mycobiome, including reduced fungal diversity and increased presence of pathogenic fungi such as Candida albicans and Malassezia spp. These changes are associated with worsened clinical parameters and increased tumor size[46-48]. Malassezia species residing in tumors may contribute to HCC development by inhibiting bile acid synthesis and modulating the tumor microenvironment[46].

In recent years, interest in the virome, the community of intestinal viruses, has increased. The intestinal virome consists of eukaryotic viruses capable of replicating in human cells and bacteriophages, which replicate in intestinal bacteria and are the most abundant viral entities in the gut[49]. It is estimated that the human intestine contains more than 1012 viruses, a number that may be comparable to that of intestinal bacteria[50]. The community of intestinal bacteriophages, known as the gut “phageome”, is of particular clinical interest. Bacteriophages play a central role in the gut microbiota by infecting and transforming local intestinal bacteria, and they also interact directly with the human immune system. For example, intestinal viruses can stimulate immune responses via toll-like receptor (TLR) 3. Additionally, viruses can influence the human body indirectly by affecting bacterial communities that produce various metabolites and signaling molecules. Most commonly, bacteriophages replicate within bacterial host cells and lyse them upon release. However, some phages can also influence bacterial physiology by altering gene expression, modulating bacterial gene transcription, or trans

The clinical significance of viromes remains largely unknown. However, there is growing evidence of a link between intestinal viruses and metabolic diseases such as type 1 diabetes mellitus and various intestinal disorders[52-54]. Liver disease has also been associated with intestinal viruses. In patients with more severe forms of NAFLD, a decreased diversity of intestinal viruses and a lower proportion of bacteriophages compared to other intestinal viruses have been observed[55]. Changes in the composition of intestinal viruses have also been reported in patients with alcoholic hepa

Thus, despite the growing interest in this topic and the emerging body of research, a comprehensive understanding of the virome’s role in various diseases remains incomplete. Nevertheless, it is becoming clear that, in addition to bacterial translocation of the gut microbiota to the liver in NAFLD, viruses may also translocate and contribute to liver pathology.

Thus, the gut microbiota has a complex composition that is maintained through various mechanisms involving both the microorganisms themselves and the human immune system. Interestingly, gut bacteria engage in various “social” interactions known as quorum sensing (QS). QS is a bacterial communication mechanism that enables the coordination of group behavior based on population density. In the gut microbiota, QS plays a crucial role in maintaining microbial balance, combating pathogens, and facilitating interactions with the host organism[58-60]. QS has been observed in both pathogenic and commensal microorganisms, highlighting the universality of this mechanism. Furthermore, QS may influence the spatial distribution of bacteria throughout the gastrointestinal tract[58]. This system is based on the release of small signaling molecules (autoinducers) by bacteria, which accumulate in the environment in proportion to bacterial density and are detected by the bacterial community. Gram-negative bacteria primarily produce species-specific acyl-homoserine lactones for this purpose, while Gram-positive bacteria mainly use autoinducing peptides. A shared signaling molecule, autoinducer-2, also known as furanosyl borate diester or tetrahydroxy furan, is used by both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria[59,61].

The macroorganism also plays a vital role in maintaining the proper composition of the gut microbiota through mechanisms such as mucus production, immune tolerance, and other regulatory processes. For example, the mucus that covers the intestinal wall promotes colonization by commensal microbiota. In turn, the microbiome can influence mucus production, both by directly activating various signaling cascades and through bioactive factors produced by epithelial cells[62,63]. Mucin 2 oligosaccharides provide numerous attachment sites for microbes and also serve as an energy source[63]. Another important mechanism by which the intestinal epithelium regulates immune responses is the secretion of cytokines and chemokines[64,65]. This secretion helps maintain a balanced interaction between intestinal microbes and the host immune system. Additionally, immune mechanisms involving intestinal epithelial cells include the production of antimicrobial peptides, which help control microbial populations in the gut, preventing infections and maintaining mucosal integrity[66,67]. Thus, over the course of a long evolutionary history of coexistence, the microbiota and the macroorganism have developed numerous mechanisms to support this mutually beneficial relationship - one that is essential for many physiological functions.

The most well-known function of the gut microbiota is its involvement in digestion. By fermenting non-digestible fiber, the gut microbiota enables the extraction of additional energy from food. This function is particularly prominent in herbivorous animals but is also important in humans, as it allows for the metabolization of certain carbohydrates that are not digested by human enzymes. The gut microbiota also has many other functions that are beyond the scope of this review, including the synthesis of essential vitamins such as vitamin K and several B vitamins, which play important roles in various physiological processes[68,69]. For example, decreased levels of vitamin B12 in obese mice may be due to reduced synthesis by the gut microbiota[70]. In addition, the gut microbiota is involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics and drugs, further highlighting its systemic importance[71].

The enzymatic activity of the gut microbiota results in the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are important immune and metabolic regulators with effects that extend far beyond the gut. The primary substrates for SCFA formation are dietary fibers, including resistant starch, cellulose, and pectin[72]. SCFAs produced by the gut microbiota serve as energy substrates for colonocytes and are also absorbed by the intestinal epithelium into the bloodstream. After absorption via the portal vein, SCFAs first enter the liver and then circulate in the peripheral bloodstream, forming part of the “axes” that link the intestine to other organs. Acetate, propionate, and butyrate are the major SCFAs produced by the gut microbiota. Their production primarily involves Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, which are mainly localized in the proximal colon[73-75].

Once in the systemic circulation, SCFAs exert their effects through G-protein-coupled receptors such as GPR43 and GPR41, also known as free fatty acid (FFA) receptors FFA2 and FFA3, respectively. They also act via the GPR109a receptor (also known as hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 or HCA2) and olfactory receptor 78[76-81]. In addition, SCFAs mediate their effects by inhibiting histone deacetylases. For example, butyrate can promote a metabolic shift in macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype by inhibiting histone deacetylase 3[82,83]. SCFAs are known to play a critical role in regulating immune responses and maintaining immune homeostasis[84,85]. They can reduce inflammation, repair the intestinal barrier, and promote the proliferation of certain immune cells, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs)[86]. In par

SCFAs, especially butyrate and propionate, reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines by dendritic cells. This modulation influences the activation and function of cluster of differentiation 8 T cells, which play a critical role in the adaptive immune response[89]. SCFAs also affect the localization and function of immune cells such as natural killer cells in the large intestine and regulate intestinal leukocyte activity through SCFA-specific receptors[90]. In macrophages, SCFAs modulate function by regulating the production of inflammatory mediators and enhancing phagocytic activity, thereby promoting pathogen elimination. Additionally, they increase the production of reactive oxygen species, which are essential for effective pathogen destruction[91].

Thus, SCFAs exert multiple biological effects on various organs and systems, including the liver, which is the first organ to receive SCFAs from the intestine via the portal vein. SCFAs have both direct and indirect effects on hepatic metabolic and immune functions. Directly, they exert immunomodulatory actions and influence liver cell metabolism. For instance, SCFAs have been shown to reduce hepatocyte apoptosis induced by uremic toxins bound to gut-derived proteins[92]. Through activation of FFAR3, SCFAs may enhance the metabolic functions of the liver[93]. Butyrate, in particular, offers protection against insulin resistance and fatty liver dystrophy by modulating mitochondrial function, efficiency, and dynamics in insulin-resistant obese mice. Specifically, it improves respiratory capacity and fatty acid oxidation, activates the AMP-activated protein kinase-acetyl-CoA carboxylase pathway, and promotes inefficient metabolism[94]. In a study involving ApoE-/- mice, butyrate treatment significantly slowed the progression of atherosclerosis and hepatic steatosis induced by a high-fat diet. Butyrate achieved this by regulating the expression of genes involved in lipid and glucose metabolism[95]. Furthermore, butyrate has been shown to increase the activity of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1, a key protein in reverse cholesterol transport, which facilitates the export of cholesterol from macrophages to form high-density lipoprotein[95]. SCFAs also stimulate the hepatic expression of ApoA-I, a major component of high-density lipoprotein particles, enabling cholesterol efflux and supporting the removal of excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues[96]. SCFAs may additionally exert effects through epigenetic mechanisms by modulating DNA methylation and histone acetylation of genes associated with NAFLD, thereby influencing lipid metabolism and immune homeostasis[97].

The indirect effects of SCFAs on the liver include their role in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier through several mechanisms. For example, butyrate can increase the expression of tight junction proteins such as claudin-1 and zonula occludens-1 in epithelial cells by activating protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin-mediated protein synthesis[98]. Additionally, SCFAs stimulate the secretion of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 in mixed colon cultures in vitro[99]. In this way, SCFAs contribute to hepatic energy balance by regulating appetite and mediating systemic glucose homeostasis[100].

Disruptions in SCFA production are associated with various inflammatory conditions, including autoimmune liver diseases such as primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis[85]. Because SCFAs possess anti-inflammatory properties, they may help reduce hepatic inflammation by modulating immune responses and lowering the production of proinflammatory cytokines[98,100]. Thus, SCFAs are essential metabolic and immune regulators in the body, and the gut microbiota plays a central role in this regulation.

Metabolic disorders play a key role in the initiation and progression of liver diseases such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Excessive intake of digestible carbohydrates and trans fats, along with reduced intake of non-digestible fiber, are well-known risk factors for NAFLD across many populations. As a result, eating disorders are a pressing concern.

It has been suggested that the gut microbiota may influence human behavior, including eating behavior. The gut microbiota interacts with the “gut-brain axis”, a bidirectional communication system between the gut and the brain mediated by hormonal, immune, and neural signals. Through this interaction, the gut microbiota can influence eating behavior as well as digestive and absorptive processes (e.g., by regulating intestinal motility and barrier integrity)[101]. Experimental studies have shown that the microbiota can influence host eating behavior through several potential mechanisms. These include microbial effects on brain reward centers, the production of mood-altering toxins, alterations in taste receptors, and interference with neural signaling via the vagus nerve - the primary neural link between the gut and brain[102]. The microbiota also produces various neurochemicals such as dopamine and serotonin, which affect both mood and behavior[103]. It is estimated that nearly half of the body’s dopamine is produced in the gut[102,104].

Studies in germ-free mice have shown an increased preference for fat and higher caloric intake from fat[105]. This was associated with enhanced sensitivity of taste receptors to fat and a marked reduction in the expression of intestinal satiety peptides and fatty acid receptors[105]. In addition, the absence of gut microbiota in mice altered the expression of sweet taste receptors and glucose transporters in the proximal small intestine, correlating with increased consumption of energy-rich sweet solutions[106].

By participating in energy extraction from the diet, the gut microbiota may contribute to energy storage in the host[107]. In obesity, the gut microbiota shows an enhanced capacity to extract energy from food and may pass this trait to the host. For example, colonization of germ-free mice with microbiota from obese mice led to a significantly greater increase in total body fat than colonization with microbiota from lean mice[108]. Thus, alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota may contribute to obesity and, consequently, to the development of metabolic risk factors for liver disease.

Cholesterol is a critical metabolite essential for various cellular functions. One of its key roles is in reverse cholesterol transport, the process by which excess cholesterol is removed from macrophages and transported to the liver for utili

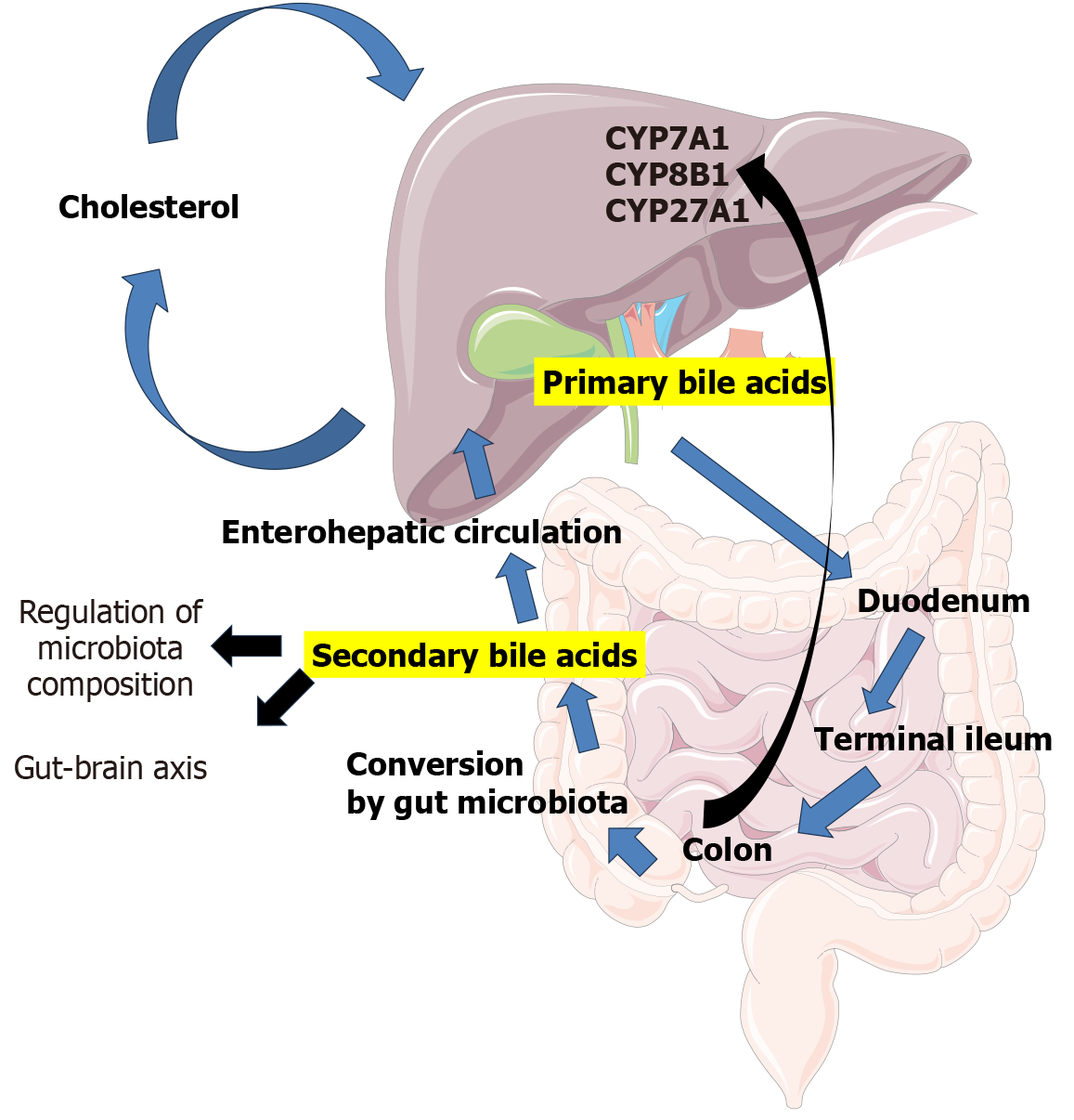

The composition of bile acids has a significant impact on the intestinal microbiota, contributing to the bidirectional communication of the “gut-liver axis”. Once primary bile acids enter the gastrointestinal tract, they are chemically transformed into secondary bile acids by the gut microbiota. These transformations involve oxidation, dehydroxylation, and conjugation with amino acids, which greatly expand the diversity of the bile acid pool[112,113]. The gut microbiota produces several enzymes essential for bile acid metabolism, including bile salt hydrolase, 7α-dehydroxylase, and hy

Secondary bile acids act as signaling molecules, influencing host metabolism and shaping the composition of the gut microbiota[112,113,116]. Bile acids also possess antimicrobial properties, which affect the growth and survival of various bacterial strains. They may accumulate within bacterial cells and disrupt metabolic functions, thereby limiting bacterial proliferation[113,117,118]. For example, deoxycholic acid can significantly inhibit bacterial growth by interfering with ribosomal transcription and amino acid metabolism[118]. Thus, the gut microbiota can significantly influence bile acid metabolism. Moreover, the gut microbiota not only transforms bile acids but may also regulate bile acid synthesis in the liver by modulating key enzymes such as cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase, sterol 12α-hydroxylase, and sterol 27-hydroxylase[119].

Interestingly, bile itself harbors a complex microbiota. In humans, its composition includes bacteria from eight different phyla, including Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Proteobacteria, Saccharibacteria, and Tenericutes. This composition is often disrupted in various biliary tract diseases. For example, patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis exhibit a decreased abundance of Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Fusobacteria, along with an increased presence of Proteobacteria, compared to healthy controls[120].

Abnormal profiles of circulating bile acids are early indicators of the development and progression of metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, HCC, and Alzheimer’s disease[121]. An increase in total bile acid concentration is frequently accompanied by a shift toward a higher proportion of taurine-conjugated bile acids, which has been observed as an early metabolic alteration in the development of HCC[122]. Some studies suggest that secondary bile acid levels may serve as useful biomarkers for diagnosing and predicting the progression of liver diseases[123]. For instance, patients with NAFLD and mild fibrosis (stage F1) show significantly higher levels of secondary bile acids than those without fibrosis[124]. Another study found elevated levels of cholic acid, deoxycholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid, ursodeoxycholic acid, and lithocholic acid in the fecal bile acid fraction of NAFLD patients compared to healthy controls. Additionally, the total serum bile acid concentration was higher in individuals with NAFLD and advanced fibrosis than in the control group[125]. A recent study also demonstrated a clear association between altered gut microbiota and changes in the primary composition of conjugated bile acids in patients with NASH without cirrhosis[126]. It has been suggested that dysregulation of bile acid homeostasis, and signaling via the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and fibroblast growth factor 19, mediated by the gut microbiota may contribute to fibrogenesis, liver injury, and oncogenesis in NASH[126]. Given these clinical findings, bile acid metabolism, and the role of the gut microbiota in regulating it, are both areas of growing interest. Thus, the gut microbiota emerges as a key player in the gut-liver axis, influencing both metabolic and immune mechanisms.

Key mechanisms in the pathogenesis of NAFLD include insulin resistance, which is a hallmark of the condition. Insulin resistance leads to increased lipolysis in adipose tissue, elevated plasma FFA levels, and promotes fat accumulation in the liver. The buildup of triglycerides and FFAs in hepatocytes causes lipotoxicity, contributing to liver inflammation and fibrosis. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are critical factors in the progression from simple steatosis to NASH. These pathological processes are driven by mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Both nutritional factors and the composition of the gut microbiota influence NAFLD development. A high-fat diet and gut dysbiosis can exacerbate hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation[127-129].

The gut microbiota plays an important role in the development and progression of NAFLD. It affects intestinal permeability, leading to the entry of bacterial endotoxins, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), into the liver via the portal vein. This process causes hepatic inflammation and contributes to the progression of NAFLD[130-132]. LPSs trigger an inflammatory response in the liver by activating TLR4 in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (liver macrophages). This activation leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-1β, and IL-6, which contribute to hepatic inflammation and the progression of NASH[133-135]. Chronic exposure to LPSs can lead to hepatic fibrosis through the activation of hepatic stellate cells via the TLR4 signaling pathway. This fibrogenic response is an important step in the transition from simple steatosis to more serious liver diseases such as cirrhosis[135]. Given that the gut microbiota influences energy metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and lipid metabolism, dysbiosis may disrupt these processes, leading to increased fat accumulation in the liver[136,137].

As noted previously, the gut microbiota converts primary bile acids into secondary bile acids that interact with re

Therapeutic approaches in the treatment of NAFLD that target the gut microbiota include the use of probiotics and prebiotics. Probiotics containing Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium bifidum have been shown to be effective in regulating gut microbiota, reducing lipid accumulation in the liver, and improving insulin sensitivity[143]. Prebiotics such as inulin and fructooligosaccharides also support the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut[144-146]. A com

Thus, abnormalities in the composition and function of the gut microbiota play an important role in NAFLD progre

The gut microbiota plays an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of liver cirrhosis through the gut-liver axis. In cirrhosis, a compromised intestinal barrier allows bacteria and their products to enter the liver, triggering immune responses and inflammation that exacerbate liver damage[150-152]. The gut microflora is the main source of LPSs in the portal vein. An imbalance in the composition of the gut microbiota is associated with cirrhosis and can lead to complications such as hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and visceral artery vasodilation[150,151,153]. Dysbacteriosis and bacterial translocation are involved in the development of hepatic encephalopathy, a serious complication of cirrhosis[150,151,154]. This condition arises from the accumulation of harmful microbial byproducts, such as ammonia, indoles, oxyindoles, and endotoxins, which build up due to dysbiosis and the liver’s reduced capacity to eliminate them[155,156]. Moreover, patients with cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy often present with a specific gut microbiota profile characterized by an increase in pathogenic bacteria such as Enterobacteriaceae, which are associated with elevated plasma ammonia levels and cognitive impairment[157]. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota may also increase the risk of portal hypertension by promoting inflammation and immune responses[152].

Modulation of the gut microbiota with antibiotics, probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics has been shown to be effective in the treatment of cirrhosis and its complications[150,151,153]. Therapeutic approaches targeting the gut microbiota in cirrhosis include the use of antibiotics to treat bacteria-related complications by reducing bacterial load and translocation[151]. Probiotics and synbiotics help restore balance to the gut microbiota, improve gut barrier function, and reduce inflammation, offering a potential therapeutic approach for the management of cirrhosis[150,151,153].

Thus, disturbances in the gut microbiota play an important role in liver cirrhosis, and therapeutic strategies aimed at correcting these imbalances are of significant clinical interest.

HCC is a complex and multifactorial disease with a poor prognosis and a high mortality rate. The pathogenesis of HCC involves a combination of genetic, molecular, and environmental factors[158,159]. HCC often develops against a background of chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis, hepatitis B and C, alcoholic liver disease, and NAFLD[160,161]. Chronic inflammation and hepatic fibrosis are key contributors to HCC development. Persistent oxidative stress and long-term inflammation cause DNA damage, further promoting HCC progression[161,162]. The tumor microenvironment, including immune cells, hepatic stellate cells, and an abnormal extracellular matrix, also plays a crucial role in the progression of HCC.

The gut microbiota is involved in the development and progression of HCC through various mechanisms[163-165]. It influences HCC via the gut-liver axis, whereby microbial metabolites and components impact liver function and immune responses[166,167]. An imbalance in the gut microbiota can promote chronic liver inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis, which are known risk factors for HCC. This inflammation is often driven by microbial products such as LPSs and other genotoxins. Persistent microbiota-induced inflammation may lead to genetic and epigenetic changes in hepatocytes, thereby facilitating carcinogenesis[163,168-170].

The gut microbiota may also contribute to HCC through the modification of bile acids[171,172]. Taurocholic acid has been shown to promote the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages toward an immunosuppressive M2 phe

It should be noted that the microbiota can modulate the immune response, which has important implications for the microbiota-macroorganism relationship. The gut immune system faces a complex task: On the one hand, it must carry out immune surveillance and eliminate pathogens; on the other hand, it must maintain immune tolerance toward the com

The gut microbiota is also associated with the intratumoral microbiota, which has a distinct profile and plays an important role in HCC progression. It may contribute by inducing DNA damage, mediating tumor-associated signaling pathways, altering the tumor microenvironment, promoting metastasis, or through other mechanisms[177]. The intratumoral microbiota in HCC is highly diverse and includes various bacterial taxa such as Enterobacteriaceae, Fusobacterium, and Neisseria, which are more prevalent in HCC tissues compared to adjacent non-tumor tissues[178,179]. The intratumoral microbiota can influence the immunosuppressive microenvironment by affecting immune cell infiltration and function. For example, in HBV-associated HCC, the presence of specific intratumoral microbiota is associated with an increase in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, both of which contribute to immune suppression[179,180]. Microbial communities in HCC tissues may also alter metabolic pathways, including the upregulation of fatty acid and lipid synthesis, potentially contributing to tumor progression[178,181]. Moreover, bacteria found within HCC tumors may exert both pro-tumor and anti-tumor effects, depending on their species and context.

Changes in the composition of the gut microbiota may serve as a biomarker for the early diagnosis of HCC and for predicting the efficacy of immunotherapy[167,182,183]. Given the close relationship between the gut and liver, modu

Thus, a growing body of evidence is advancing our understanding of the complex interactions between the gut microbiota and HCC, highlighting new possibilities for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic intervention.

The gut microbiota is of growing interest to clinicians and researchers across various fields of medicine. It is closely associated with multiple organs and systems of the body, including the liver. The relationship between the liver and the gut microbiota is bidirectional and involves numerous complex interactions. The gut microbiota contributes to main

| Therapeutic strategy | Contents | Clinical benefit | |

| Antibiotics | Prophylactic and therapeutic use of antibiotics in cirrhosis | Treatment of bacterial infections in cirrhosis, including SBP | |

| Probiotics | Useful microbiota | Reducing gut microbiota permeability (“leaky gut”) | |

| Reduction of systemic inflammation | |||

| Correction of intestinal dysbiosis | |||

| Effect on metabolism | |||

| Prebiotics | Inulin, fructooligosaccharides, galacto-oligosaccharides, oligosaccharides derived from starch and glucose, pectin oligosaccharides, non-carbohydrate oligosaccharides | Prebiotics stimulate the growth and activity of their own beneficial microflora | Stimulation of the growth of beneficial microbiota |

| Production of SCFAs | |||

| Suppression of pathogens | |||

| Reduction of ammonia levels (in cirrhosis) | |||

| Synbiotics | Combinations of probiotics and prebiotics | Synbiotic supplements may improve liver function, regulate lipid metabolism, and reduce the degree of liver fibrosis | |

| Fecal microbiota transplantation | Fecal microbiota from a healthy donor is injected into the gastrointestinal tract of another patient | Clinical studies have shown the effectiveness of the procedure in infectious and non-infectious liver diseases | |

Thus, the connection between gut microbiota and liver disease is of clear clinical interest. Promising directions for future research include deeper exploration of the immune and metabolic mechanisms linking the gut microbiota and the liver, as well as evaluating the roles of other gut microbial community members, such as archaea and fungi. Identifying new biomarkers and therapeutic approaches also remains a key priority. Experimental research is underway in several areas, including genetic engineering of intestinal bacteria and the use of bacteriophages[148,192,193]. However, the clinical applicability of these methods is still not fully established.

| 1. | Pires L, Gonzalez-Paramás AM, Heleno SA, Calhelha RC. Gut Microbiota as an Endocrine Organ: Unveiling Its Role in Human Physiology and Health. Appl Sci. 2024;14:9383. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Baquero F, Nombela C. The microbiome as a human organ. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18 Suppl 4:2-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Afzaal M, Saeed F, Shah YA, Hussain M, Rabail R, Socol CT, Hassoun A, Pateiro M, Lorenzo JM, Rusu AV, Aadil RM. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:999001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Ferranti EP, Dunbar SB, Dunlop AL, Corwin EJ. 20 things you didn't know about the human gut microbiome. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29:479-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mafra D, Ribeiro M, Fonseca L, Regis B, Cardozo LFMF, Fragoso Dos Santos H, Emiliano de Jesus H, Schultz J, Shiels PG, Stenvinkel P, Rosado A. Archaea from the gut microbiota of humans: Could be linked to chronic diseases? Anaerobe. 2022;77:102629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, Mele MC. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms. 2019;7:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 969] [Cited by in RCA: 2283] [Article Influence: 326.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 7. | Jandhyala SM, Talukdar R, Subramanyam C, Vuyyuru H, Sasikala M, Nageshwar Reddy D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8787-8803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1421] [Cited by in RCA: 1970] [Article Influence: 179.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (79)] |

| 8. | Tilg H, Adolph TE, Trauner M. Gut-liver axis: Pathophysiological concepts and clinical implications. Cell Metab. 2022;34:1700-1718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 455] [Article Influence: 113.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pabst O, Hornef MW, Schaap FG, Cerovic V, Clavel T, Bruns T. Gut-liver axis: barriers and functional circuits. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:447-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mantovani A, Scorletti E, Mosca A, Alisi A, Byrne CD, Targher G. Complications, morbidity and mortality of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2020;111S:154170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 63.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Xiao J, Wang F, Yuan Y, Gao J, Xiao L, Yan C, Guo F, Zhong J, Che Z, Li W, Lan T, Tacke F, Shah VH, Li C, Wang H, Dong E. Epidemiology of liver diseases: global disease burden and forecasted research trends. Sci China Life Sci. 2025;68:541-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tan EY, Danpanichkul P, Yong JN, Yu Z, Tan DJH, Lim WH, Koh B, Lim RYZ, Tham EKJ, Mitra K, Morishita A, Hsu YC, Yang JD, Takahashi H, Zheng MH, Nakajima A, Ng CH, Wijarnpreecha K, Muthiah MD, Singal AG, Huang DQ. Liver cancer in 2021: Global Burden of Disease study. J Hepatol. 2025;82:851-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 81.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Liu Y, Zhong GC, Tan HY, Hao FB, Hu JJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:11124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kardashian A, Serper M, Terrault N, Nephew LD. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77:1382-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 51.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Manikat R, Nguyen MH. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and non-liver comorbidities. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:s86-s102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Price JK, Owrangi S, Gundu-Rao N, Satchi R, Paik JM. The Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1999-2010.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 95.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Amini-Salehi E, Letafatkar N, Norouzi N, Joukar F, Habibi A, Javid M, Sattari N, Khorasani M, Farahmand A, Tavakoli S, Masoumzadeh B, Abbaspour E, Karimzad S, Ghadiri A, Maddineni G, Khosousi MJ, Faraji N, Keivanlou MH, Mahapatro A, Gaskarei MAK, Okhovat P, Bahrampourian A, Aleali MS, Mirdamadi A, Eslami N, Javid M, Javaheri N, Pra SV, Bakhsi A, Shafipour M, Vakilpour A, Ansar MM, Kanagala SG, Hashemi M, Ghazalgoo A, Kheirandish M, Porteghali P, Heidarzad F, Zeinali T, Ghanaei FM, Hassanipour S, Ulrich MT, Melson JE, Patel D, Nayak SS. Global Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Updated Review Meta-Analysis comprising a Population of 78 million from 38 Countries. Arch Med Res. 2024;55:103043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rajilić-Stojanović M, de Vos WM. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:996-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 765] [Cited by in RCA: 814] [Article Influence: 67.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Valsecchi C, Carlotta Tagliacarne S, Castellazzi A. Gut Microbiota and Obesity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50 Suppl 2, Proceedings from the 8th Probiotics, Prebiotics & New Foods for Microbiota and Human Health meeting held in Rome, Italy on September 13-15, 2015:S157-S158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bakker GJ, Nieuwdorp M. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Therapeutic Potential for a Multitude of Diseases beyond Clostridium difficile. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5:10.1128/microbiolspec.bad-0008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ghosh S, Pramanik S. Structural diversity, functional aspects and future therapeutic applications of human gut microbiome. Arch Microbiol. 2021;203:5281-5308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jin YF, Wen WJ, Zuo T. [Phages in human health and gut microbiota transplantation therapy]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2025;28:261-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stefanaki C. The Gut Microbiome Beyond the Bacteriome—The Neglected Role of Virome and Mycobiome in Health and Disease. In: Faintuch J, Faintuch S, editors. Microbiome and Metabolome in Diagnosis, Therapy, and other Strategic Applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2019. |

| 24. | Wernroth ML, Peura S, Hedman AM, Hetty S, Vicenzi S, Kennedy B, Fall K, Svennblad B, Andolf E, Pershagen G, Theorell-Haglöw J, Nguyen D, Sayols-Baixeras S, Dekkers KF, Bertilsson S, Almqvist C, Dicksved J, Fall T. Development of gut microbiota during the first 2 years of life. Sci Rep. 2022;12:9080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Toubon G, Butel MJ, Rozé JC, Nicolis I, Delannoy J, Zaros C, Ancel PY, Aires J, Charles MA. Early Life Factors Influencing Children Gut Microbiota at 3.5 Years from Two French Birth Cohorts. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu X, Yu J, Huan Z, Xu M, Song T, Yang R, Zhu W, Jiang J. Comparing the gut microbiota of Sichuan golden monkeys across multiple captive and wild settings: roles of anthropogenic activities and host factors. BMC Genomics. 2024;25:148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Clayton JB, Vangay P, Huang H, Ward T, Hillmann BM, Al-Ghalith GA, Travis DA, Long HT, Tuan BV, Minh VV, Cabana F, Nadler T, Toddes B, Murphy T, Glander KE, Johnson TJ, Knights D. Captivity humanizes the primate microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:10376-10381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mathur R, Barlow GM. Obesity and the microbiome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:1087-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lee Y, Lee HY. Revisiting the Bacterial Phylum Composition in Metabolic Diseases Focused on Host Energy Metabolism. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44:658-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Magne F, Gotteland M, Gauthier L, Zazueta A, Pesoa S, Navarrete P, Balamurugan R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients. 2020;12:1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 1516] [Article Influence: 252.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Houtman TA, Eckermann HA, Smidt H, de Weerth C. Gut microbiota and BMI throughout childhood: the role of firmicutes, bacteroidetes, and short-chain fatty acid producers. Sci Rep. 2022;12:3140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Karačić A, Renko I, Krznarić Ž, Klobučar S, Liberati Pršo AM. The Association between the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio and Body Mass among European Population with the Highest Proportion of Adults with Obesity: An Observational Follow-Up Study from Croatia. Biomedicines. 2024;12:2263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stojanov S, Berlec A, Štrukelj B. The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 1260] [Article Influence: 210.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yin Y, Yang T, Tian Z, Shi C, Yan C, Li H, Du Y, Li G. Progress in the investigation of the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio as a potential pathogenic factor in ulcerative colitis. J Med Microbiol. 2025;74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gao W, Zhu Y, Ye J, Chu H. Gut non-bacterial microbiota contributing to alcohol-associated liver disease. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1984122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Borrel G, McCann A, Deane J, Neto MC, Lynch DB, Brugère JF, O'Toole PW. Genomics and metagenomics of trimethylamine-utilizing Archaea in the human gut microbiome. ISME J. 2017;11:2059-2074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Feehan B, Ran Q, Dorman V, Rumback K, Pogranichniy S, Ward K, Goodband R, Niederwerder MC, Lee STM. Novel complete methanogenic pathways in longitudinal genomic study of monogastric age-associated archaea. Anim Microbiome. 2023;5:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Chen Q, Lyu W, Pan C, Ma L, Sun Y, Yang H, Wang W, Xiao Y. Tracking investigation of archaeal composition and methanogenesis function from parental to offspring pigs. Sci Total Environ. 2024;927:172078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Poles MZ, Juhász L, Boros M. Methane and Inflammation - A Review (Fight Fire with Fire). Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019;7:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Triantafyllou K, Chang C, Pimentel M. Methanogens, methane and gastrointestinal motility. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Pimentel M, Lin HC, Enayati P, van den Burg B, Lee HR, Chen JH, Park S, Kong Y, Conklin J. Methane, a gas produced by enteric bacteria, slows intestinal transit and augments small intestinal contractile activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1089-G1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | An S, Cho EY, Hwang J, Yang H, Hwang J, Shin K, Jung S, Kim BT, Kim KN, Lee W. Methane gas in breath test is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Breath Res. 2024;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Hoffmann C, Dollive S, Grunberg S, Chen J, Li H, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Bushman FD. Archaea and fungi of the human gut microbiome: correlations with diet and bacterial residents. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 581] [Article Influence: 44.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | You N, Xu J, Wang L, Zhuo L, Zhou J, Song Y, Ali A, Luo Y, Yang J, Yang W, Zheng M, Xu J, Shao L, Shi J. Fecal Fungi Dysbiosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:350-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sun S, Wang K, Sun L, Cheng B, Qiao S, Dai H, Shi W, Ma J, Liu H. Therapeutic manipulation of gut microbiota by polysaccharides of Wolfiporia cocos reveals the contribution of the gut fungi-induced PGE(2) to alcoholic hepatic steatosis. Gut Microbes. 2020;12:1830693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Shen W, Li Z, Wang L, Liu Q, Zhang R, Yao Y, Zhao Z, Ji L. Tumor-resident Malassezia can promote hepatocellular carcinoma development by downregulating bile acid synthesis and modulating tumor microenvironment. Sci Rep. 2025;15:15020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Liu Z, Li Y, Li C, Lei G, Zhou L, Chen X, Jia X, Lu Y. Intestinal Candida albicans Promotes Hepatocarcinogenesis by Up-Regulating NLRP6. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:812771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Zhang L, Chen C, Chai D, Li C, Qiu Z, Kuang T, Liu L, Deng W, Wang W. Characterization of the intestinal fungal microbiome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2023;21:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lecuit M, Eloit M. The Viruses of the Gut Microbiota. In: Floch MH, Ringel Y, Walker WA, editors. The Microbiota in Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. Academic Press, 2017: 179-183. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Shkoporov AN, Hill C. Bacteriophages of the Human Gut: The "Known Unknown" of the Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:195-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 69.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Godsil M, Ritz NL, Venkatesh S, Meeske AJ. Gut phages and their interactions with bacterial and mammalian hosts. J Bacteriol. 2025;207:e0042824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Wu Y, Cheng R, Lin H, Li L, Jia Y, Philips A, Zuo T, Zhang H. Gut virome and its implications in the pathogenesis and therapeutics of inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Med. 2025;23:183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Zhao G, Vatanen T, Droit L, Park A, Kostic AD, Poon TW, Vlamakis H, Siljander H, Härkönen T, Hämäläinen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Ilonen J, Wang D, Knip M, Xavier RJ, Virgin HW. Intestinal virome changes precede autoimmunity in type I diabetes-susceptible children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E6166-E6175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Cinek O, Kramna L, Lin J, Oikarinen S, Kolarova K, Ilonen J, Simell O, Veijola R, Autio R, Hyöty H. Imbalance of bacteriome profiles within the Finnish Diabetes Prediction and Prevention study: Parallel use of 16S profiling and virome sequencing in stool samples from children with islet autoimmunity and matched controls. Pediatr Diabetes. 2017;18:588-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Lang S, Demir M, Martin A, Jiang L, Zhang X, Duan Y, Gao B, Wisplinghoff H, Kasper P, Roderburg C, Tacke F, Steffen HM, Goeser T, Abraldes JG, Tu XM, Loomba R, Stärkel P, Pride D, Fouts DE, Schnabl B. Intestinal Virome Signature Associated With Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1839-1852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Jiang L, Lang S, Duan Y, Zhang X, Gao B, Chopyk J, Schwanemann LK, Ventura-Cots M, Bataller R, Bosques-Padilla F, Verna EC, Abraldes JG, Brown RS Jr, Vargas V, Altamirano J, Caballería J, Shawcross DL, Ho SB, Louvet A, Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Garcia-Tsao G, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, Tu XM, Stärkel P, Pride D, Fouts DE, Schnabl B. Intestinal Virome in Patients With Alcoholic Hepatitis. Hepatology. 2020;72:2182-2196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Deng Y, Jiang S, Duan H, Shao H, Duan Y. Bacteriophages and their potential for treatment of metabolic diseases. J Diabetes. 2024;16:e70024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Wu L, Luo Y. Bacterial Quorum-Sensing Systems and Their Role in Intestinal Bacteria-Host Crosstalk. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:611413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Falà AK, Álvarez-Ordóñez A, Filloux A, Gahan CGM, Cotter PD. Quorum sensing in human gut and food microbiomes: Significance and potential for therapeutic targeting. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1002185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zhang Y, Ma N, Tan P, Ma X. Quorum sensing mediates gut bacterial communication and host-microbiota interaction. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024;64:3751-3763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Su Y, Ding T. Targeting microbial quorum sensing: the next frontier to hinder bacterial driven gastrointestinal infections. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2252780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Okumura R, Takeda K. Roles of intestinal epithelial cells in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 521] [Article Influence: 57.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Kim YS, Ho SB. Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:319-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 821] [Cited by in RCA: 1010] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Vitkus SJ, Hanifin SA, McGee DW. Factors affecting Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cell interleukin-6 secretion. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1998;34:660-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Stadnyk AW. Intestinal epithelial cells as a source of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:241-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Muniz LR, Knosp C, Yeretssian G. Intestinal antimicrobial peptides during homeostasis, infection, and disease. Front Immunol. 2012;3:310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Gubatan J, Holman DR, Puntasecca CJ, Polevoi D, Rubin SJ, Rogalla S. Antimicrobial peptides and the gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:7402-7422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 68. | Mishra T, Mallik B, Kesheri M, Kanchan S. The Interplay of Gut Microbiome in Health and Diseases. In: Kesheri M, Kanchan S, Salisbury TB, Sinha RP, editors. Microbial Omics in Environment and Health. Singapore: Springer, 2024: 1-34. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 69. | Lukáčová I, Ambro Ľ, Dubayová K, Mareková M. The gut microbiota, its relationship to the immune system, and possibilities of its modulation. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2023;72:40-53. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Zabolotneva AA, Kolesnikova IM, Vasiliev IY, Grigoryeva TV, Roumiantsev SA, Shestopalov AV. The Obesogenic Gut Microbiota as a Crucial Factor Defining the Depletion of Predicted Enzyme Abundance for Vitamin B12 Synthesis in the Mouse Intestine. Biomedicines. 2024;12:1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Clayton TA, Baker D, Lindon JC, Everett JR, Nicholson JK. Pharmacometabonomic identification of a significant host-microbiome metabolic interaction affecting human drug metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14728-14733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 558] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Parada Venegas D, De la Fuente MK, Landskron G, González MJ, Quera R, Dijkstra G, Harmsen HJM, Faber KN, Hermoso MA. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 970] [Cited by in RCA: 2457] [Article Influence: 351.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Relman DA. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5700] [Cited by in RCA: 5684] [Article Influence: 270.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 74. | den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325-2340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2408] [Cited by in RCA: 3516] [Article Influence: 270.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 75. | Feng W, Ao H, Peng C. Gut Microbiota, Short-Chain Fatty Acids, and Herbal Medicines. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Nilsson NE, Kotarsky K, Owman C, Olde B. Identification of a free fatty acid receptor, FFA2R, expressed on leukocytes and activated by short-chain fatty acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:1047-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Corrêa-Oliveira R, Fachi JL, Vieira A, Sato FT, Vinolo MA. Regulation of immune cell function by short-chain fatty acids. Clin Transl Immunology. 2016;5:e73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in RCA: 960] [Article Influence: 96.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Li M, van Esch BCAM, Wagenaar GTM, Garssen J, Folkerts G, Henricks PAJ. Pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on immune and endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;831:52-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 56.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Pluznick J. A novel SCFA receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Thangaraju M, Cresci GA, Liu K, Ananth S, Gnanaprakasam JP, Browning DD, Mellinger JD, Smith SB, Digby GJ, Lambert NA, Prasad PD, Ganapathy V. GPR109A is a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2826-2832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 604] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Le Poul E, Loison C, Struyf S, Springael JY, Lannoy V, Decobecq ME, Brezillon S, Dupriez V, Vassart G, Van Damme J, Parmentier M, Detheux M. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25481-25489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1107] [Cited by in RCA: 1269] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Schulthess J, Pandey S, Capitani M, Rue-Albrecht KC, Arnold I, Franchini F, Chomka A, Ilott NE, Johnston DGW, Pires E, McCullagh J, Sansom SN, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. The Short Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate Imprints an Antimicrobial Program in Macrophages. Immunity. 2019;50:432-445.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 771] [Article Influence: 110.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Wu L, Seon GM, Kim Y, Choi SH, Vo QC, Yang HC. Enhancing effect of sodium butyrate on phosphatidylserine-liposome-induced macrophage polarization. Inflamm Res. 2022;71:641-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Xiong RG, Zhou DD, Wu SX, Huang SY, Saimaiti A, Yang ZJ, Shang A, Zhao CN, Gan RY, Li HB. Health Benefits and Side Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Foods. 2022;11:2863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Zhang W, Mackay CR, Gershwin ME. Immunomodulatory Effects of Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Autoimmune Liver Diseases. J Immunol. 2023;210:1629-1639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Ostadmohammadi S, Nojoumi SA, Fateh A, Siadat SD, Sotoodehnejadnematalahi F. Interaction between Clostridium species and microbiota to progress immune regulation. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2022;69:89-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | McBride DA, Dorn NC, Yao M, Johnson WT, Wang W, Bottini N, Shah NJ. Short-chain fatty acid-mediated epigenetic modulation of inflammatory T cells in vitro. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2023;13:1912-1924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Luu M, Visekruna A. Short-chain fatty acids: Bacterial messengers modulating the immunometabolism of T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2019;49:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Nastasi C, Fredholm S, Willerslev-Olsen A, Hansen M, Bonefeld CM, Geisler C, Andersen MH, Ødum N, Woetmann A. Butyrate and propionate inhibit antigen-specific CD8(+) T cell activation by suppressing IL-12 production by antigen-presenting cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Kasubuchi M, Hasegawa S, Hiramatsu T, Ichimura A, Kimura I. Dietary gut microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, and host metabolic regulation. Nutrients. 2015;7:2839-2849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 494] [Cited by in RCA: 638] [Article Influence: 58.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Xie Q, Li Q, Fang H, Zhang R, Tang H, Chen L. Gut-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Macrophage Modulation: Exploring Therapeutic Potentials in Pulmonary Fungal Infections. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2024;66:316-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Deng M, Li X, Li W, Gong J, Zhang X, Ge S, Zhao L. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Alleviate Hepatocyte Apoptosis Induced by Gut-Derived Protein-Bound Uremic Toxins. Front Nutr. 2021;8:756730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Shimizu H, Masujima Y, Ushiroda C, Mizushima R, Taira S, Ohue-Kitano R, Kimura I. Dietary short-chain fatty acid intake improves the hepatic metabolic condition via FFAR3. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Mollica MP, Mattace Raso G, Cavaliere G, Trinchese G, De Filippo C, Aceto S, Prisco M, Pirozzi C, Di Guida F, Lama A, Crispino M, Tronino D, Di Vaio P, Berni Canani R, Calignano A, Meli R. Butyrate Regulates Liver Mitochondrial Function, Efficiency, and Dynamics in Insulin-Resistant Obese Mice. Diabetes. 2017;66:1405-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Du Y, Li X, Su C, Xi M, Zhang X, Jiang Z, Wang L, Hong B. Butyrate protects against high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis via up-regulating ABCA1 expression in apolipoprotein E-deficiency mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:1754-1772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Tayyeb JZ, Popeijus HE, Mensink RP, Konings MCJM, Mulders KHR, Plat J. The effects of short-chain fatty acids on the transcription and secretion of apolipoprotein A-I in human hepatocytes in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:17219-17227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Tang R, Liu R, Zha H, Cheng Y, Ling Z, Li L. Gut microbiota induced epigenetic modifications in the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease pathogenesis. Eng Life Sci. 2024;24:2300016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Li X, He M, Yi X, Lu X, Zhu M, Xue M, Tang Y, Zhu Y. Short-chain fatty acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: New prospects for short-chain fatty acids as therapeutic targets. Heliyon. 2024;10:e26991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Tolhurst G, Heffron H, Lam YS, Parker HE, Habib AM, Diakogiannaki E, Cameron J, Grosse J, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes. 2012;61:364-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1524] [Cited by in RCA: 1735] [Article Influence: 123.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Zhang S, Zhao J, Xie F, He H, Johnston LJ, Dai X, Wu C, Ma X. Dietary fiber-derived short-chain fatty acids: A potential therapeutic target to alleviate obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Butt RL, Volkoff H. Gut Microbiota and Energy Homeostasis in Fish. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Alcock J, Maley CC, Aktipis CA. Is eating behavior manipulated by the gastrointestinal microbiota? Evolutionary pressures and potential mechanisms. Bioessays. 2014;36:940-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Kim DY, Camilleri M. Serotonin: a mediator of the brain-gut connection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2698-2709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Eisenhofer G, Aneman A, Friberg P, Hooper D, Fåndriks L, Lonroth H, Hunyady B, Mezey E. Substantial production of dopamine in the human gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3864-3871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Duca FA, Swartz TD, Sakar Y, Covasa M. Increased oral detection, but decreased intestinal signaling for fats in mice lacking gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Swartz TD, Duca FA, de Wouters T, Sakar Y, Covasa M. Up-regulation of intestinal type 1 taste receptor 3 and sodium glucose luminal transporter-1 expression and increased sucrose intake in mice lacking gut microbiota. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:621-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15718-15723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4530] [Cited by in RCA: 4523] [Article Influence: 205.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 108. | Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9796] [Cited by in RCA: 9023] [Article Influence: 451.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 109. | Collins SL, Stine JG, Bisanz JE, Okafor CD, Patterson AD. Bile acids and the gut microbiota: metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:236-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 680] [Cited by in RCA: 667] [Article Influence: 222.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Alberto González-Regueiro J, Moreno-Castañeda L, Uribe M, Carlos Chávez-Tapia N. The Role of Bile Acids in Glucose Metabolism and Their Relation with Diabetes. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16:S15-S20. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Zhang YL, Li ZJ, Gou HZ, Song XJ, Zhang L. The gut microbiota-bile acid axis: A potential therapeutic target for liver fibrosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:945368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Tang J, Xu W, Yu Y, Yin S, Ye BC, Zhou Y. The role of the gut microbial metabolism of sterols and bile acids in human health. Biochimie. 2025;230:43-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Lucas LN, Barrett K, Kerby RL, Zhang Q, Cattaneo LE, Stevenson D, Rey FE, Amador-Noguez D. Dominant Bacterial Phyla from the Human Gut Show Widespread Ability To Transform and Conjugate Bile Acids. mSystems. 2021;6:101128msystems0080521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Rezasoltani S, Sadeghi A, Radinnia E, Naseh A, Gholamrezaei Z, Azizmohammad Looha M, Yadegar A. The association between gut microbiota, cholesterol gallstones, and colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2019;12 (Suppl1):S8-S13. [PubMed] |

| 115. | Han L, Pendleton A, Singh A, Xu R, Scott SA, Palma JA, Diebold P, Malarney KP, Brito IL, Chang PV. Chemoproteomic profiling of substrate specificity in gut microbiota-associated bile salt hydrolases. Cell Chem Biol. 2025;32:145-156.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Hild B, Heinzow HS, Schmidt HH, Maschmeier M. Bile Acids in Control of the Gut-Liver-Axis. Z Gastroenterol. 2021;59:63-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Larabi AB, Masson HLP, Bäumler AJ. Bile acids as modulators of gut microbiota composition and function. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2172671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 71.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Peng YL, Wang SH, Zhang YL, Chen MY, He K, Li Q, Huang WH, Zhang W. Effects of bile acids on the growth, composition and metabolism of gut bacteria. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2024;10:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Wang B, Han D, Hu X, Chen J, Liu Y, Wu J. Exploring the role of a novel postbiotic bile acid: Interplay with gut microbiota, modulation of the farnesoid X receptor, and prospects for clinical translation. Microbiol Res. 2024;287:127865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Tyc O, Jansen C, Schierwagen R, Uschner FE, Israelsen M, Klein S, Ortiz C, Strassburg CP, Zeuzem S, Gu W, Torres S, Praktiknjo M, Kersting S, Langheinrich M, Nattermann J, Servant F, Arumugam M, Krag A, Lelouvier B, Weismüller TJ, Trebicka J. Variation in Bile Microbiome by the Etiology of Cholestatic Liver Disease. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:1652-1657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Qi L, Chen Y. Circulating Bile Acids as Biomarkers for Disease Diagnosis and Prevention. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:251-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Stepien M, Lopez-Nogueroles M, Lahoz A, Kühn T, Perlemuter G, Voican C, Ciocan D, Boutron-Ruault MC, Jansen E, Viallon V, Leitzmann M, Tjønneland A, Severi G, Mancini FR, Dong C, Kaaks R, Fortner RT, Bergmann MM, Boeing H, Trichopoulou A, Karakatsani A, Peppa E, Palli D, Krogh V, Tumino R, Sacerdote C, Panico S, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Skeie G, Merino S, Ros RZ, Sánchez MJ, Amiano P, Huerta JM, Barricarte A, Sjöberg K, Ohlsson B, Nyström H, Werner M, Perez-Cornago A, Schmidt JA, Freisling H, Scalbert A, Weiderpass E, Christakoudi S, Gunter MJ, Jenab M. Prediagnostic alterations in circulating bile acid profiles in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2022;150:1255-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Jahnel J, Zöhrer E, Alisi A, Ferrari F, Ceccarelli S, De Vito R, Scharnagl H, Stojakovic T, Fauler G, Trauner M, Nobili V. Serum Bile Acid Levels in Children With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |