Published online Oct 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i10.109583

Revised: May 30, 2025

Accepted: September 11, 2025

Published online: October 27, 2025

Processing time: 165 Days and 8.9 Hours

Patients and providers are often unaware of available treatment options for alcohol use disorder (AUD) and how to pursue them.

To improve AUD treatment rates using an educational video module (EVM).

Prospective single-center cohort study evaluating the impact of a novel interactive patient EVM in promoting AUD treatment among hospitalized patients with alcohol-associated liver disease. Treatment was defined as receiving medication or participating in psychosocial treatment within 30 days of discharge. Primary outcome was change in treatment rates after viewing the EVM compared to a retrospective control cohort. Secondary outcomes were predictors of receiving treatment, EVM feedback, 30-day hospital readmission, outpatient follow-up, return to alcohol use, and mortality.

Forty-two patients were included. Mean age was 45 years, 50% were female, and mean model for end-stage liver disease score 15.5. After viewing the EVM, treatment rates increased for pharmacologic (50% vs 22%, P = 0.0008) and psychosocial treatment (73.8% vs 44%, P = 0.01). Return to alcohol use was significantly lower (7.9% vs 35.6%, P = 0.003). All 100% of patients would recommend the EVM.

EVM allows hospitalized patients to receive standardized education about AUD treatment. This may address patient and provider knowledge gaps and reduce the growing burden of alcohol-associated liver disease. Future studies should evaluate EVM in larger patient populations using a multi-center study design.

Core Tip: This prospective single-center study evaluated the impact of an educational video module (EVM) on promoting alcohol use disorder treatment among hospitalized patients with alcohol-associated liver disease. The study included 42 patients and compared outcomes with a retrospective control group. Viewing the EVM significantly increased rates of pharmacologic (50% vs 22%) and psychosocial treatment (73.8% vs 44%) within 30 days of discharge. Return to alcohol use was also significantly reduced (7.9% vs 35.6%). All participants endorsed the EVM. The findings suggest EVMs can effectively bridge knowledge gaps and improve treatment engagement for patients with alcohol-associated liver disease and alcohol use disorder.

- Citation: Twohig P, Slocum ZP, Willet A, Schissel M, Balasanova AA, Scholten K, Warner J, Sempokuya T, Khoury N, Ashford A, Peeraphatdit TB. Novel educational video module about alcohol use disorder increases treatment rates and decreases return to alcohol use. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(10): 109583

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i10/109583.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i10.109583

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is the seventh leading risk factor for premature death and disability worldwide[1-5]. Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) accounts for 50% of all liver-related deaths and is the most common reason for liver transplantation in the United States[1-3]. American Association for the Study of Liver Disease guidelines reco

Despite the compelling efficacy of AUD treatment, utilization in clinical practice is very low[8,12]. Patients with AUD have many interactions with healthcare professionals, but AUD is often underrecognized or dismissed[13]. A survey of gastroenterology and hepatology providers found that only 61% of providers referred patients for behavioral therapy, 71% have never prescribed pharmacotherapy, 50% endorse a lack of knowledge about Food and Drug Administration approved medications, and 90% desired more formal training on AUD treatment[14]. This highlights that providers lack the knowledge necessary to educate and treat patients.

Patient education plays a fundamental role in managing AUD, as it empowers individuals with a better understanding of their condition, available treatment options, and self-management strategies[15-17]. This may help prevent return to alcohol use and facilitate long-term recovery. Educating patients about the effects of substance use can motivate them to actively participate in the recovery process and seek support in a compassionate, supportive environment that minimizes stigma, enhances coping skills, and increases treatment adherence[15-17].

Educational video modules (EVM) are a powerful tool in patient education that combine interactive visual and auditory features to enhance the learning experience and improve knowledge retention[18-20]. By giving patients control over the content, EVM can adapt to the learner’s pace, making the learning activity personalized, which promotes a sense of ownership and increased motivation to learn[21]. Providing EVM to hospitalized patients increases accessibility and convenience, allowing patients to engage in education while awaiting tests or visits from medical personnel. EVM offers flexibility, as they can be viewed from computers, tablets, or smartphones, increasing patient participation by making the content accessible regardless of the time of day[22].

Our primary aim was to compare AUD treatment rates between patients viewing the EVM compared to a retrospective control cohort of patients with AUD and ALD at our medical center from 2018 to 2020 who did not view the EVM. Secondary outcomes included characteristics associated with receiving AUD treatment, patient feedback about the EVM, and 30-day outcomes including hospital readmission, outpatient clinic follow-up, return to alcohol use, and mortality.

We performed a single-center prospective cohort study evaluating the impact of a novel interactive patient EVM[23] on promoting AUD treatment for hospitalized patients with ALD and AUD from December 2022 to March 2023 at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska, United States of America.

AUD was defined using International Classification of Diseases codes, self-reporting, and/or documentation in the medical record (either from provider notes or lab work showing positive serum ethanol or phosphatidylethanol levels while hospitalized).

ALD was diagnosed if a patent had any of the following: Abnormal liver chemistries (alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase), or imaging showing steatosis, steatohepatitis, or cirrhosis (compensated or decompensated). We included English and Spanish speaking patients aged 19 years or older, who were able to provide informed consent, with a diagnosis of AUD and with evidence of ALD.

We excluded non-hospitalized patients, those unable to provide consent (e.g. altered mental status, critical illness), those speaking languages other than English or Spanish (because the consent forms and EVM were not available in other languages) and those 18 years of age or younger. We excluded patients who were not actively drinking at the time of hospitalization or had no evidence of liver disease. Patients who declined to participate or who died, were lost to follow-up, or received a liver transplant within 30 days of enrolling in the study were also excluded.

Before starting enrollment, we sent an e-mail to all providers in the departments of internal medicine, family medicine, psychiatry, and gastroenterology/hepatology at our institution to inform them of the study, inclusion, and exclusion criteria. Providers were requested to notify the research team if they were caring for any hospitalized patients who met the inclusion criteria.

If criteria were met, one of the research team members visited with the patient to provide a brief intervention on AUD. This brief intervention utilized motivational interviewing and harm reduction strategies to engage patients in a discussion about AUD treatment and ask their permission to participate in the study. If informed consent was obtained, then the patient was included in the study. If patients declined to participate in the study after the brief intervention, they were not consented and were subsequently excluded from the study.

When a patient gave consent to participate, the authors notified their bedside nurse who then provided the EVM[23] on one of the hospital’s bedside tablets. The patients included in the prospective cohort are henceforth referred to as the treatment education for alcohol misuse (TEAM) cohort. All research was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul. This study was approved by the University of Nebraska Institutional Review Board. Written consent for participation was obtained from all subjects in the study.

Baseline data: At the time of enrolment, we collected demographic information including age, sex, ethnicity, insurance, and marital status. We collected the patients self reported history of alcohol use using standardized number of drinks per day[3], serum ethanol and/or phosphatidylethanol levels from the hospitalization (if available), history of alcohol withdrawal, and if they had received any prior pharmacologic or psychosocial treatment for AUD. To assess ALD, we categorized the patients as having steatosis, alcohol hepatitis, or cirrhosis based on a combination of serologic (elevated alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase) and/or imaging parameters (hepatitis, steatosis, cirrhosis) during their hospitalization. If cirrhotic, we also recorded their model for end-stage liver disease score and if there was a history of hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, esophageal varices, and/or hepatocellular carcinoma at the time of hospitalization. We also evaluated whether a patient was seen in consultation with the addiction psychiatry service and/or gastroenterology/hepatology service while hospitalized.

EVM feedback: After viewing the EVM, patients were verbally asked by a member of the research team if the EVM was helpful (yes/no) in educating them about AUD, and if they would recommend it others (yes/no)[23].

30-day outcome data: Thirty days after enrollment, all patients had their medical record reviewed to assess if any AUD treatment was provided at the time of hospital discharge based on documentation in the medical record and pharmacy dispense records. In addition to assessing the provision and type of AUD treatment received, records were also reviewed for hospital readmission, mortality, outpatient clinic follow up, and if any repeat objective measures of alcohol use were available at 30 days from enrollment (serum ethanol or phosphatidylethanol levels).

All patients were also contacted by telephone by a member of the research team to confirm the above outcome data and to assess their standardized number of drinks consumed daily since discharge using the timeline follow-back method[24]. During this telephone call, patients were also asked about their ongoing engagement with treatment since hospital discharge.

To evaluate the impact of the EVM[23] on AUD treatment rates and outcomes, we compared our results to a retrospective control cohort of 109 patients with AUD and ALD at our institution from 2018-2020 who did not view the EVM[23]. This retrospective cohort was matched for demographics and severity of illness and received usual care for AUD and ALD while hospitalized. We were able to make direct comparisons of the impact of our EVM intervention on treatment rates, along with 30-day outcomes including return to alcohol use, hospital readmission, mortality, and outpatient clinic follow-up.

We did not compare outcomes in the EVM cohort to those who declined participation as there were only 12 patients who did not consent to participate (small for statistical comparison), and including these patients would have contradicted our approved research study protocol.

We developed an original, interactive EVM for patients using Articulate Storyline™ software[23]. The module is 15 minutes in length and includes content about the epidemiology of AUD and available treatment options. The EVM was developed in English and Spanish using best practices in instructional design and following national standards for comprehension, readability, and understandability[23]. Content expertise was provided by addiction psychiatrists, internists, and hepatologists, to address typical care gaps in AUD and ALD using the EVM. The EVM was uploaded to our hospital’s internal web server and made available on all bedside tablets (iPads®) which are located at every unit of the hospital and are normally used by patients during their hospitalization for routine education, meal ordering, and test results[23]. At the end of the module, patients were encouraged to have further discussions with their inpatient medical team about which treatment option(s) they may be interested in.

In addition to the EVM, patients received a list of local and national alcohol treatment resources and websites in their discharge paperwork[23].

As part of this study, we created an order set within the Epic® electronic health record to help providers more easily assess a patient’s candidacy for treatment using standardized serologic testing and assist with prescribing medications at discharge.

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, counts, and percentages) were used to summarize patient demographics and clinical characteristics. McNemar’s test was used to compare treatment rates before and after intervention within the EVM group. A Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed to assess differences in continuous variables of interest between those receiving treatment and those not receiving treatment. χ2 or Fisher’s exact test were used as appropriate to compare all categorical variables of interest between groups. All analyses were conducted in Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 by a biomedical statistician. A P value less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

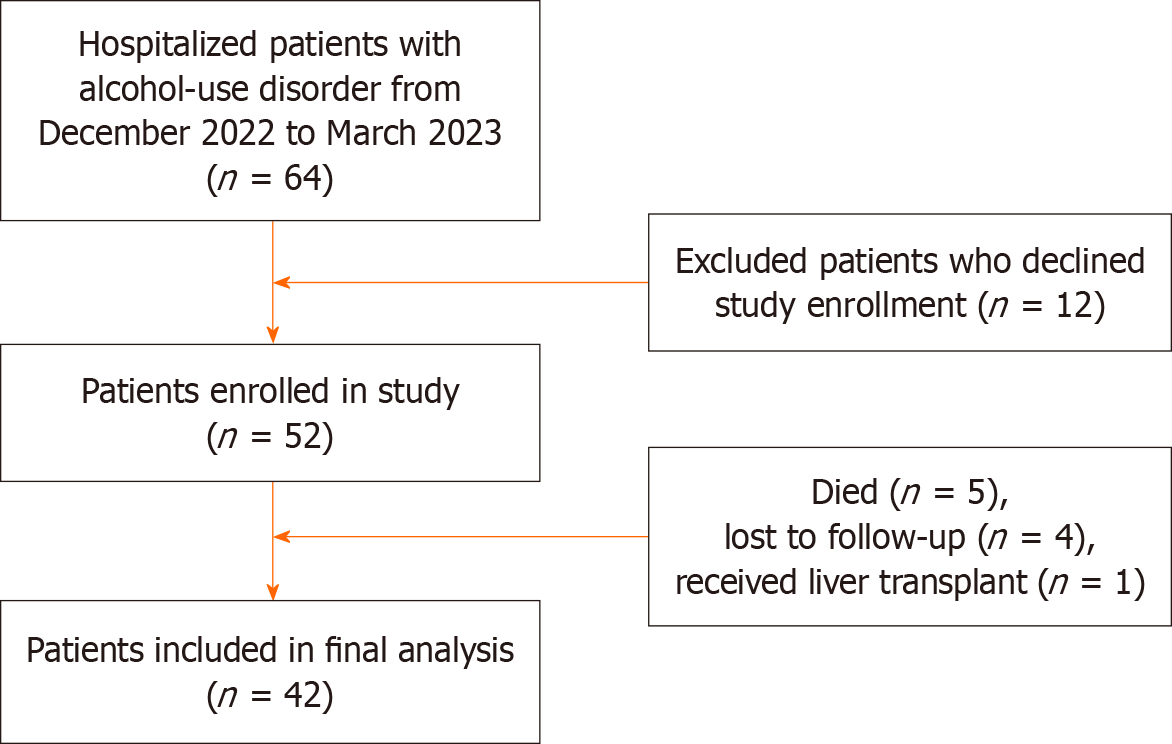

The flow chart used to identify patients is shown in Figure 1. Of 64 eligible patients hospitalized with AUD and ALD at the University of Nebraska Medical Center from December 12, 2022, until March 30, 2023, 52 patients consented to participate in the study, of which 42 were included in the analysis (5 died, 4 were lost to follow-up, and 1 received a liver transplant).

The median age of patients in the study was 45 years [interquartile range (IQR): 35.5, 51.5], with equal representation between males and females. Approximately 60% are Caucasian, followed by 21% Hispanic, 11.5% African American, 4% other, and 2% African and Native American, respectively. A combined 38.5% had Medicaid or Medicare, 36.5% had private insurance, and 25% had no insurance. The majority (79%) are unmarried.

For ALD variables, approximately 42% had alcohol-associated hepatitis, 40% had cirrhosis, and 17% had steatosis. The median model for end-stage liver disease score for the cohort was 15.5 (IQR: 10.0, 25.0). The most prevalent symptom of decompensated cirrhosis was ascites (42.3% of patients).

For AUD variables, the median self-reported number of standard drinks consumed per day at time of hospitalization was 8.0 (IQR: 3.0, 22.0), with a median serum ethanol level of 71.0 g/dL (IQR: 0.0, 224.0) and phosphatidylethanol level of 356.5 g/dL (IQR: 51.0, 917.0). Almost 60% of patients had experienced alcohol withdrawal in the past, 26.9% had previously been treated with AUD medications, 36.5% had engaged in psychosocial treatment, and 11.5% received a combination of medications and psychosocial treatment. Approximately two-thirds of patients were seen in consultation by the addiction psychiatry service and/or the gastroenterology/hepatology service (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Patient total (n = 52) |

| Age | |

| N (missing) | 52 (0) |

| Median (IQR) | 45.0 (35.5, 51.5) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 26 (50.0) |

| Male | 26 (50.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| African | 1 (1.9) |

| African American | 6 (11.5) |

| Caucasian | 31 (59.6) |

| Hispanic | 11 (21.2) |

| Native American | 1 (1.9) |

| Other | 2 (3.8) |

| Insurance | |

| Medicaid | 8 (15.4) |

| Medicare | 12 (23.1) |

| None | 8 (15.4) |

| Private | 19 (36.5) |

| Self-pay | 5 (9.6) |

| Marital status | |

| Not married | 41 (78.8) |

| Married | 11 (21.2) |

| Liver disease | |

| Alcohol hepatitis | 22 (42.3) |

| Cirrhosis | 21 (40.4) |

| Steatosis | 9 (17.3) |

| MELD-Na | |

| N (missing) | 46 (6) |

| Median (IQR) | 15.5 (10.0, 25.0) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | |

| No | 45 (86.5) |

| Yes | 7 (13.5) |

| Ascites | |

| No | 30 (57.7) |

| Yes | 22 (42.3) |

| Esophageal varices | |

| No | 40 (76.9) |

| Yes | 12 (23.1) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | |

| No | 52 (100.0) |

| Self-reported drinks | |

| N (missing) | 52 (0) |

| Median (IQR) | 8.0 (3.0, 22.0) |

| Ethanol | |

| N (missing) | 48 (4) |

| Median (IQR) | 71.0 (0.0, 224.0) |

| Phosphatidylethanol (pETH) | |

| N (missing) | 26 (26) |

| Median (IQR) | 356.5 (51.0, 917.0) |

| Withdrawal | |

| No | 21 (40.4) |

| Yes | 31 (59.6) |

| Previous pharmacologic treatment | |

| No | 38 (73.1) |

| Yes | 14 (26.9) |

| Acamprosate | |

| No | 49 (94.2) |

| Yes | 3 (5.8) |

| Disulfiram | |

| No | 52 (100.0) |

| Naltrexone | |

| No | 42 (80.8) |

| Yes | 10 (19.2) |

| Vivitrol | |

| No | 42 (80.8) |

| Yes | 10 (19.2) |

| Previous behavioral treatment | |

| No | 33 (63.5) |

| Yes | 19 (36.5) |

| Inpatient treatment | |

| No | 44 (84.6) |

| Yes | 8 (15.4) |

| Outpatient treatment | |

| No | 44 (84.6) |

| Yes | 8 (15.4) |

| Mutual aid | |

| No | 37 (71.2) |

| Yes | 15 (28.8) |

| Behavioral and pharmacologic treatment | |

| No | 46 (88.5) |

| Yes | 6 (11.5) |

| Seen by addiction psychiatry | |

| No | 16 (30.8) |

| Yes | 36 (69.2) |

| Seen by GI | |

| No | 17 (32.7) |

| Yes | 35 (67.3) |

Thirty-six (85.7%) patients received any AUD treatment (21 pharmacologic, 31 psychosocial, and 17 received more than one treatment). Of the 21 patients (50%) who received pharmacologic therapy, the distribution of medications was: Acamprosate (5 patients), oral naltrexone (14 patients), intramuscular extended-release naltrexone (14 patients), and disulfiram (0 patients) (Table 2). Seventeen (81%) of the patients who received pharmacologic therapy also engaged in psychosocial treatment(s) after discharge.

| Outcome variable | Treatment group | Total (n = 42) | P value1 | ||||

| No treatment none (n = 6) | Treatment | ||||||

| Pharmacologic (n = 21) | Behavioral (n = 31) | Both (n = 17) | Any treatment (n = 36) | ||||

| 30-day follow-up | 1.0012 | ||||||

| Attempted, unsuccessful | 0 (0.0) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.7) | 2 (4.9) | |

| Successful | 6 (100.0) | 19 (90.5) | 30 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 33 (94.3) | 39 (95.1) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Recall drinks | 0.8623 | ||||||

| N (missing) | 6 (0) | 18 (3) | 28 (3) | 16 (1) | 31 (5) | 37 (5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | |

| Ethanol | |||||||

| N (missing) | 2 (4) | 9 (12) | 12 (19) | 7 (10) | 14 (22) | 16 (26) | - |

| Median (IQR) | 103.0 (0.0, 206.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 162.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 81.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 162.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 174.0) | - |

| Phosphatidylethanol (pETH) | |||||||

| N (missing) | 1 (5) | 3 (18) | 9 (22) | 3 (14) | 9 (27) | 10 (32) | - |

| Median (IQR) | 14.0 (14.0, 14.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 14.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 14.0) | - |

| Outpatient follow-up visit | 0.3712 | ||||||

| No | 5 (83.3) | 10 (50.0) | 14 (50.0) | 6 (37.5) | 18 (54.5) | 23 (59.0) | |

| Yes | 1 (16.7) | 10 (50.0) | 14 (50.0) | 10 (62.5) | 15 (45.5) | 16 (41.0) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| 30-day readmission | 1.0012 | ||||||

| No | 4 (66.7) | 14 (66.7) | 21 (67.7) | 12 (70.6) | 25 (69.4) | 29 (69.0) | |

| Yes | 2 (33.3) | 7 (33.3) | 10 (32.3) | 5 (29.4) | 11 (30.6) | 13 (31.0) | |

| 30-day mortality | 1.0012 | ||||||

| No | 6 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 29 (93.5) | 17 (100.0) | 34 (94.4) | 40 (95.2) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (4.8) | |

| 30-day relapse | 0.4112 | ||||||

| No | 5 (83.3) | 17 (89.5) | 27 (93.1) | 16 (94.1) | 30 (93.8) | 35 (92.1) | |

| Yes | 1 (16.7) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (5.9) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (7.9) | |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| Found the module helpful | 0.3912 | ||||||

| No | 1 (16.7) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (5.9) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Yes | 5 (83.3) | 18 (94.7) | 29 (93.5) | 16 (94.1) | 32 (94.1) | 37 (92.5) | |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Recommend the module | |||||||

| Yes | 6 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) | 31 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 34 (100.0) | 40 (100.0) | - |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | - |

Of the 52 patients evaluated in our cohort, all 52 (100%) received a brief intervention as part of enrolling in the study. There were no significant differences in AUD treatment provision based on demographic or liver disease variables, or if a patient had received prior treatment. 92.5% of patients found the module helpful and 100% would recommend it to others.

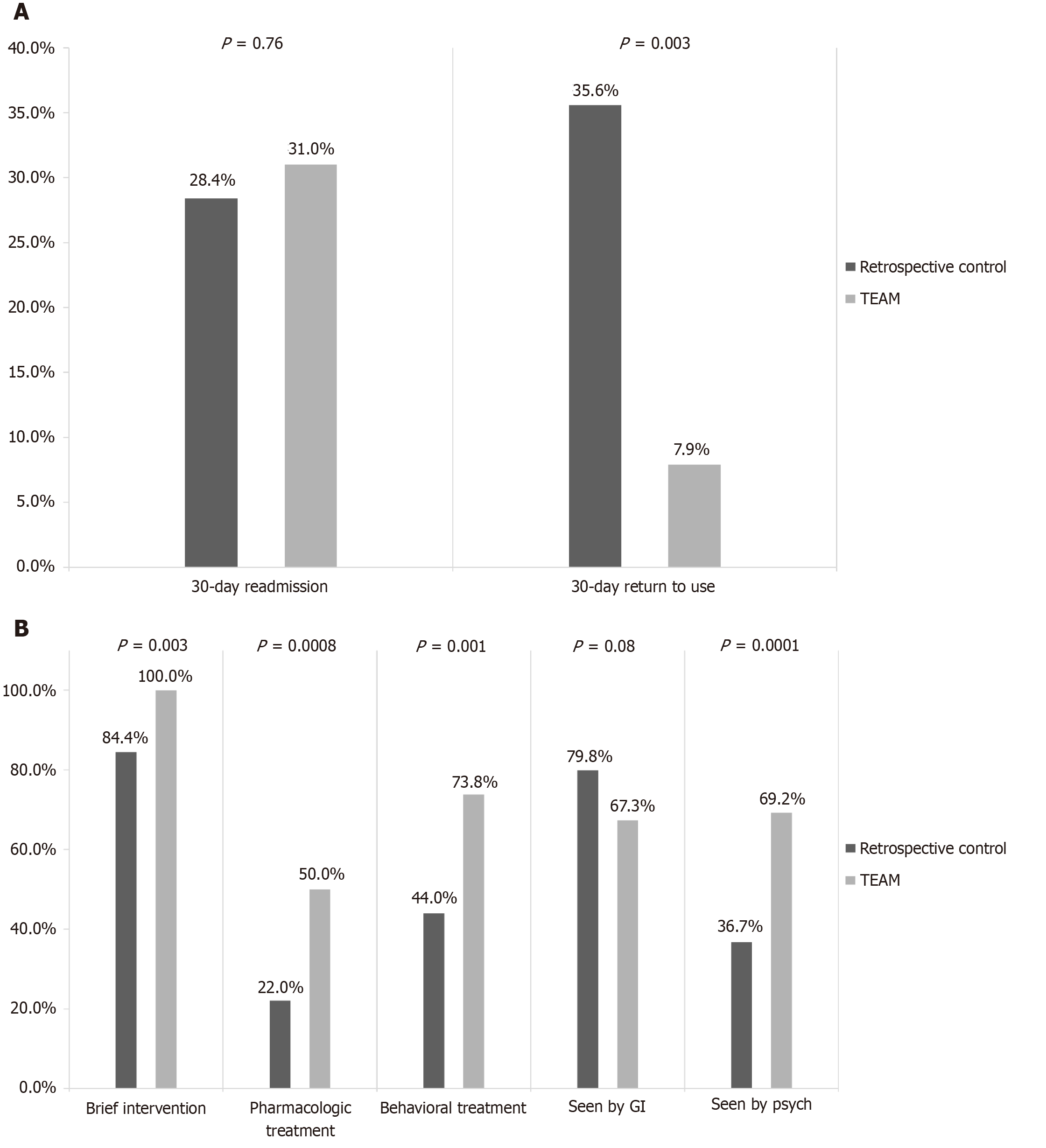

Pre- vs post-intervention within TEAM cohort: Within our prospective cohort, patients who viewed the EVM had a significant reduction in mean standard number of drinks consumed per day (12.6 drinks vs 2.1 drinks), serum ethanol (118 g/dL vs 76.7 g/dL) and phosphatidylethanol levels (467.6 g/dL vs 18.7 g/dL) post-intervention compared to pre-intervention. Additionally, patients received more treatment than they had prior to admission (Table 3 and Figure 2A). There was no significant difference in 30-day mortality regardless of whether AUD treatment was received.

| Treatment | Group | P value | |

| Pre-intervention (n = 43) | Post-intervention (n = 43) | ||

| Pharmacy treatment | 0.021 | ||

| No | 31 (72.1) | 22 (51.2) | |

| Yes | 12 (27.9) | 21 (48.8) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Acamprosate | 0.481 | ||

| No | 40 (93.0) | 38 (88.4) | |

| Yes | 3 (7.0) | 5 (11.6) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Disulfiram | |||

| No | 43 (100) | 43 (100) | - |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | - |

| Naltrexone | 0.201 | ||

| No | 34 (79.1) | 29 (67.4) | |

| Yes | 9 (20.9) | 14 (32.6) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Vivitrol | 0.171 | ||

| No | 34 (79.1) | 29 (67.4) | |

| Yes | 9 (20.9) | 14 (32.6) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Behavioral treatment | 0.0031 | ||

| No | 27 (62.8) | 12 (27.9) | |

| Yes | 16 (37.2) | 31 (72.1) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Inpatient treatment | 0.261 | ||

| No | 36 (83.7) | 39 (90.7) | |

| Yes | 7 (16.3) | 4 (9.3) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Outpatient treatment | 0.00021 | ||

| No | 39 (90.7) | 23 (53.5) | |

| Yes | 4 (9.3) | 20 (46.5) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Mutual aid | 0.101 | ||

| No | 28 (66.7) | 20 (47.6) | |

| Yes | 14 (33.3) | 22 (52.4) | |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

| Behavioral and pharmacologictreatment | 0.0071 | ||

| No | 37 (88.1) | 25 (59.5) | |

| Yes | 5 (11.9) | 17 (40.5) | |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

TEAM cohort vs retrospective control: The mean age of patients in the retrospective control cohort was 51.3 years (vs 45 years in the TEAM cohort), 63% were male (vs 50% in TEAM), with 81.7% Caucasian (vs 60% in TEAM), 7.3% African American (vs 11.5% in TEAM), and 5.5% were Hispanic (vs 21% in TEAM). The proportion of patients with insurance in each cohort was similar (77% in retrospective control vs 75% in TEAM).

AUD treatment rates increased compared to control for both pharmacologic (50% vs 22%, P = 0.0008) and psychosocial treatment (73.8% vs 44%, P = 0.001). Significantly more patients were seen by the addiction psychiatry service during hospitalization (36.7% vs 69.2%, P = 0.0001) (Figure 2A). Thirty-day return to alcohol use was also significantly lower within the TEAM cohort and between the TEAM cohort compared to control (7.9% vs 35.6%, P = 0.003) (Figure 2B). There were no significant improvements in 30-day readmission or in 30-day mortality between the TEAM vs control group.

We present the first study to develop, implement, and evaluate the impact of an EVM for AUD on hospitalized patients. Our study found that providing EVM to hospitalized patients with AUD and ALD significantly improves rates of both pharmacological and psychosocial treatment, while reducing 30-day return to drinking, average number of drinks consumed, and serum ethanol/phosphatidylethanol levels.

Our study shows the utility of EVM for hospitalized patients with AUD and ALD. By providing education about the harms of AUD and available treatments, patients may subsequently develop an increased self-awareness about their alcohol use and be more inclined to decrease unhealthy alcohol use, which could reduce the long-term morbidity and mortality associated with AUD.

Prior studies have highlighted the knowledge gap that exists for providers in effectively counseling patients with AUD on available treatment options[14]. Providing EVM may help bridge this gap and allow patients to learn about treatment options more proactively, which when combined with medical provider education, can increase engagement, comprehension, and information retention while reinforcing content discussed with medical providers[15-17]. EVM also allow patients to receive consistent, standardized information that is self-paced, accessible both in terms of time of day, remotely, and in different languages. EVM are cost-effective and scalable to broader audiences, which may not be possible with routine medical visits.

EVM may also benefit providers by allowing for the development of new communication techniques to explain complex medical concepts and incorporate harm reduction strategies with motivational interviewing.

Our findings highlight that most patients are interested in learning more about AUD treatment, as 81% of patients that met inclusion criteria agreed to participate in the study. Given the time that patients spend awaiting medical testing and treatment, EVM can provide ongoing education to patients and their families about AUD and the importance of treatment even without a medical provider present.

Our findings re-iterate the results of previous studies emphasizing the crucial role that brief interventions, motivational interviewing, and patient education plays in enhancing treatment engagement, promoting treatment adherence, and reducing return to drinking[25-30].

Our study exclusively looked at EVM use among hospitalized patients. As a result, the impact of this EVM on outpatients with AUD was not assessed. Due to the relative severity of illness that requires hospitalization, this is a more captive audience that may be more willing to participate in education, producing possible Hawthorne effect[31]. As illustrated in Figure 1, we excluded patients who were not interested in receiving education about AUD. This highlights that a portion of hospitalized patients with AUD and ALD are in the pre-contemplative stage of change, which could produce selection bias. Developing ways to utilize motivational interviewing in these patients is an area for further study. Due to the design of our study, it is possible that we may have unintentionally excluded patients who were captured through screening during their hospitalization. We did not individually assess the impact of the brief intervention or sub-specialty consultation with gastroenterology/hepatology and/or addiction psychiatry in this study, all of which may have impacted patients’ interest in pursuing AUD treatment and influenced the results of the study with possible confounding. Due to study design limitations and restricted time frame of our study, it would be helpful to assess the impact of this EVM over a longer period and assess outcome data beyond 30-days after implementation. Our study population was relatively small, and of a demographically restricted sample (Caucasian and Hispanic, English/Spanish speaking only) drawn from a single academic medical center. In future, using a multi-center study design could increase the study population size and provide a more ethnically, financially, and geographically diverse patient population. Finally, future research may attempt to add a third arm (brief intervention only) to accredit the effects of the EVM.

Future studies should evaluate the specific components of an EVM, implement EVM in both inpatient and outpatient settings, as well as further assess potential confounding factors when providing patient education on AUD. Patients often spend time spend waiting to see providers in the waiting room of outpatient clinics and during hospital admissions and both in the inpatient and outpatient settings, which may provide a convenient opportunity to provide brief patient-centered education in a focused manner. Additionally, EVM could be utilized in remote/telehealth care of AUD patients who may have decreased access to specialty care. Patient empowerment through education about impact of AUD on ALD as well as available treatment options can play a key role in helping increase motivation to pursue treatment.

Our study found that providing a standardized EVM to hospitalized patients with AUD and ALD can effectively increase rates of both pharmacological and psychosocial treatment for AUD, as well as a reduction in rates of 30-day return to alcohol use, mean number of drinks consumed, and mean serum ethanol and phosphatidylethanol levels. There is a significant AUD treatment gap in the care of patients with ALD. Given the rise of alcohol consumption since the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, increased patient awareness of AUD treatment options may lead to a higher likelihood of pursuing treatment, which could subsequently reduce the burden of access to AUD on ALD, on the healthcare system, and society at large.

We thank Carol Carney, Tristan Gilmore, and Kory Wede as research coordinators for this study. We thank the patient education committee and Information Technology specialists at the University of Nebraska Medical Center who helped get this video module in the hands of our patients.

| 1. | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results From the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. |

| 2. | Coriale G, Fiorentino D, De Rosa F, Solombrino S, Scalese B, Ciccarelli R, Attilia F, Vitali M, Musetti A, Fiore M, Ceccanti M; Interdisciplinary Study Group CRARL - SITAC - SIPaD - SITD - SIPDip. Treatment of alcohol use disorder from a psychological point of view. Riv Psichiatr. 2018;53:141-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Tenth special report to the US Congress on alcohol and health. Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000. |

| 4. | Kranzler HR, Soyka M. Diagnosis and Pharmacotherapy of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Review. JAMA. 2018;320:815-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 54.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223-2233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2298] [Cited by in RCA: 2379] [Article Influence: 139.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lucey MR, Im GY, Mellinger JL, Szabo G, Crabb DW. Introducing the 2019 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Guidance on Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:14-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A; COMBINE Study Research Group. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003-2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1167] [Cited by in RCA: 1184] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jophlin LL, Singal AK, Bataller R, Wong RJ, Sauer BG, Terrault NA, Shah VH. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:30-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 77.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Bobashev G, Thomas K, Wines R, Kim MM, Shanahan E, Gass CE, Rowe CJ, Garbutt JC. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1889-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 736] [Cited by in RCA: 654] [Article Influence: 54.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, Kubik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Reduce Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network (MODRN), Donohue JM, Jarlenski MP, Kim JY, Tang L, Ahrens K, Allen L, Austin A, Barnes AJ, Burns M, Chang CH, Clark S, Cole E, Crane D, Cunningham P, Idala D, Junker S, Lanier P, Mauk R, McDuffie MJ, Mohamoud S, Pauly N, Sheets L, Talbert J, Zivin K, Gordon AJ, Kennedy S. Use of Medications for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder Among US Medicaid Enrollees in 11 States, 2014-2018. JAMA. 2021;326:154-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tobler-Ammann BC, de Bruin ED, Brugger P, de Bie RA, Knols RH. The Zürich Maxi Mental Status Inventory (ZüMAX): Test-Retest Reliability and Discriminant Validity in Stroke Survivors. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2016;29:78-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee CW, Vitous CA, Silveira MJ, Forman J, Dossett LA, Mody L, Dimick JB, Suwanabol PA. Delays in Palliative Care Referral Among Surgical Patients: Perspectives of Surgical Residents Across the State of Michigan. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57:1080-1088.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | O'Connor EA, Perdue LA, Senger CA, Rushkin M, Patnode CD, Bean SI, Jonas DE. Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Reduce Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Adults: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:1910-1928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:963-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1101] [Cited by in RCA: 839] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bakke Ø, Endal D. Vested interests in addiction research and policy alcohol policies out of context: drinks industry supplanting government role in alcohol policies in sub-Saharan Africa. Addiction. 2010;105:22-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nadkarni A, Weobong B, Weiss HA, McCambridge J, Bhat B, Katti B, Murthy P, King M, McDaid D, Park AL, Wilson GT, Kirkwood B, Fairburn CG, Velleman R, Patel V. Counselling for Alcohol Problems (CAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for harmful drinking in men, in primary care in India: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:186-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gass N, Becker R, Sack M, Schwarz AJ, Reinwald J, Cosa-Linan A, Zheng L, von Hohenberg CC, Inta D, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weber-Fahr W, Gass P, Sartorius A. Antagonism at the NR2B subunit of NMDA receptors induces increased connectivity of the prefrontal and subcortical regions regulating reward behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235:1055-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Coulton S, Dale V, Deluca P, Gilvarry E, Godfrey C, Kaner E, McGovern R, Newbury-Birch D, Patton R, Parrott S, Perryman K, Phillips T, Shepherd J, Drummond C, Heather N. Corrigendum: Screening for At-Risk Alcohol Consumption in Primary Care: A Randomized Evaluation of Screening Approaches. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53:499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Reed MB, Woodruff SI, DeMers G Capt, Matteucci M Capt, Chavez SJ, Hellner M, Hurtado SL. Results of a Randomized Trial of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) to Reduce Alcohol Misuse Among Active-Duty Military Personnel. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2021;82:269-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mandati P, Dumpa N, Alzahrani A, Nyavanandi D, Narala S, Wang H, Bandari S, Repka MA, Tiwari S, Langley N. Hot-Melt Extrusion-Based Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing of Atorvastatin Calcium Tablets: Impact of Shape and Infill Density on Printability and Performance. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2022;24:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Singal AK, DiMartini A, Leggio L, Arab JP, Kuo YF, Shah VH. Identifying Alcohol Use Disorder in Patients With Cirrhosis Reduces 30-Days Readmission Rate. Alcohol Alcohol. 2022;57:576-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Twohig P, Slocum ZP, Willet A, Schissel M, Balasanova AA, Scholten K, Warner J, Sempokuya T, Khoury N, Ashford A, Peeraphatdit TB. Starting a Conversation About Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). December 15, 2022. [cited 15 May 2025]. Available from: https://webmedia.unmc.edu/intmed/education/aud/story.html. |

| 24. | Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-back: A technique for assessing self–reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Totowa: Humana Press, 1992: 41–72. |

| 25. | Patrick ME, Evans-Polce R, Kloska DD, Maggs JL, Lanza ST. Age-Related Changes in Associations Between Reasons for Alcohol Use and High-Intensity Drinking Across Young Adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78:558-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chi FW, Parthasarathy S, Palzes VA, Kline-Simon AH, Metz VE, Weisner C, Satre DD, Campbell CI, Elson J, Ross TB, Lu Y, Sterling SA. Alcohol brief intervention, specialty treatment and drinking outcomes at 12 months: Results from a systematic alcohol screening and brief intervention initiative in adult primary care. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;235:109458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rabiee A, Mahmud N, Falker C, Garcia-Tsao G, Taddei T, Kaplan DE. Medications for alcohol use disorder improve survival in patients with hazardous drinking and alcohol-associated cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e0093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, Campbell F, Pienaar ED, Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Saunders JB, Burnand B. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD004148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dhital R, Norman I, Whittlesea C, Murrells T, McCambridge J. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions delivered by community pharmacists: randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2015;110:1586-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Li L, Zhu S, Tse N, Tse S, Wong P. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing to reduce illicit drug use in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2016;111:795-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. "It's been an Experience, a Life Learning Experience": A Qualitative Study of Hospitalized Patients with Substance Use Disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/