Published online Oct 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i10.109092

Revised: June 4, 2025

Accepted: September 22, 2025

Published online: October 27, 2025

Processing time: 181 Days and 9.4 Hours

Genomic medicine has evolved significantly, merging centuries of scientific progress with modern molecular biology and clinical care. It utilizes knowledge of the human genome to enhance disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and potential reversal. Genomic medicine in hepatology is particularly promising due to the crucial role of the liver in several metabolic processes and its association with diseases such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, and cardiovascular conditions. The mid-20th century witnessed a paradigm shift in medicine, marked by the emergence of molecular biology, which enabled a deeper understanding of gene expression and regulation. This connection between basic science and clinical practice has enhanced our knowledge of the role of gene-environment interactions in the onset and progression of liver diseases. In Latin America, including Mexico, with its genetically diverse and admixed populations, genomic medicine provides a foundation for personalized and culturally relevant health strategies. This review highlights the need for genomic medicine, examining its historical evolution, integration into hepatology in Mexico, and its potential applications in the pre

Core Tip: Genomic medicine in hepatology studies the gene-environment interactions that lead to the development of liver diseases. The liver expresses numerous genes involved in the physiology and pathophysiology of several comorbidities, such as diabetes, chronic liver disease, and cardiovascular disease. This work aimed to provide an overview of the study of the liver from its early days to genomic medicine, emphasizing its role in chronic diseases and its use in diagnosing and preventing them at early stages. It also highlighted the need to train healthcare professionals in genomic medicine, creating a new approach to medicine in Mexico and other Latin American countries.

- Citation: Panduro A, Roman S, Leal-Mercado L, Cardenas-Benitez JP, Mariscal-Martinez IM. Evolution of hepatology practice in Mexico and Latin America: From biochemical markers to genomic medicine. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(10): 109092

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i10/109092.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i10.109092

Genomic medicine aims to prevent and reverse chronic diseases by understanding the structure and function of the human genome. Analyzing genetic variations that predispose individuals to disease provides a foundation for personalized interventions and predictive care[1]. This approach is particularly relevant in addressing non-communicable diseases, which are increasingly prevalent in Latin America[2].

Hepatology, which focuses on liver function and disease, is relevant to genomic medicine due to the significant role of the liver in metabolic regulation and gene expression. Liver dysfunction contributes to diseases such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), liver cirrhosis, and car

Genomic medicine bridges the gap between basic science and clinical practice by identifying genetic susceptibility to chronic diseases and enabling early medical and nutritional interventions[4]. This progress stems from a historical trajectory of scientific discovery from ancient theories to molecular biology and the Human Genome Project, which laid the foundation for the current genomic era.

Humans share 99.9% of their DNA, yet the remaining 0.1%, comprising key genetic polymorphisms, is crucial in determining disease susceptibility and treatment response[5]. This genetic diversity is particularly significant in Latin America where admixed populations have been shaped by unique gene-environment interactions stemming from Amerindian, European, and African ancestries[6]. In this context, genomic medicine offers an opportunity to deliver culturally and genetically tailored healthcare that meets the diverse needs of these populations.

This article outlines the historical development of genomic medicine and its integration into hepatology. We describe the emergence of genomic medicine in hepatology in Mexico and highlight its role in preventing chronic diseases. Furthermore, we emphasize the importance of training future healthcare professionals in genomic literacy and promoting integrative approaches to disease prevention.

Ancient Greek medicine focused on balancing the bodily humors (phlegm, blood, black bile, and yellow bile) linking the patient’s temperament with their environment. Hippocrates of Cos (c. 460-c. 375 BC), often referred to as the father of medicine, introduced this theory of the Four Humors[7,8] that prevailed to the mid-19th century.

Historically, life was attributed to mystical forces. During the Middle Ages (5th-16th century), vitalism dominated, positing a “vital force” in all living beings[9]. Although later challenged by mechanistic explanations, the concept has had a lasting influence on medical terminology as evident in phrases such as “vital signs” and “resuscitation.”

Alchemy, blending early chemistry and philosophy, prevailed until the Enlightenment. Paracelsus (1493-1541) integrated alchemical practices into medicine, paving the way for the development of pharmacology[10,11]. René Descartes’ (1596-1650) mechanistic view of the body promoted systematic reasoning, known as Cartesian reasoning, which is crucial for modern clinical methods[12,13].

The 19th century brought scientific rigor to the field of biology. Matthias Schleiden (1804-1881) and Theodor Schwann (1810-1882) proposed the cell theory[14,15]; Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) linked heredity to the nucleus[16,17]. Gregor Mendel’s (1822-1884) experiments with pea plants in 1865 established the principles of inheritance patterns[18-20]. In the early 1900s, DE Vries[21] expanded on this concept by proposing the theory of mutation, suggesting that new species arise from sudden genetic changes. Garrod’s (1857-1936) work[22] on alkaptonuria linked genes to metabolism while Bateson[23] (1861-1926) coined the term genetics.

By 1920, chemists had synthesized numerous organic compounds[24], helping to consolidate a new scientific area: Physical chemistry[25], in which outstanding chemists and physicists began studying the structural-function re

Among the scientists of this stage were Hermann Emil Fischer (1852-1919), who described peptide bonds[27,28], and Phoebus Levene (1869-1940), who distinguished DNA from RNA by their specific nucleotides[29,30]. Gilbert Newton Lewis (1875-1946) introduced the concept of covalent bonds[31] while Linus Pauling and others identified hydrogen bonds and secondary protein structures[32,33].

In 1938, Warren Weaver (1894-1978), director of the Division of Natural Sciences at the Rockefeller Foundation, coined the term molecular biology to describe the study of biological processes at the molecular level, thereby uniting an interdisciplinary team of mathematicians, physicists, chemists, and biologists[34,35]. This field gained momentum with studies of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, which led to the chromosomal theory of inheritance by Thomas Hunt Morgan (1866-1945)[36]. George Beadle’s (1903-1989) and Edward Tatum’s (1909-1975) work on the yeast Neurospora crassa linked genes and enzymatic functions, establishing the concept of one gene-one enzyme[37].

Rosalind Franklin’s (1920-1958) X-ray diffraction images, notably Photo 51, were pivotal in revealing the double-helix structure of DNA, which was later modeled by James Watson (b. 1928- ) and Francis Crick (1916-2004) in 1953[38]. Crick, Brenner (1927-2019), and others later cracked the genetic code[39].

By the 1970s and 1980s, tools like the plasmid vector pBR322 cloned by Bolivar et al[40] and Soberon et al[41], complemented by Southern and northern blotting techniques to identify sequences[42,43], and the polymerase chain reaction by Kary Bank Mullis (1944-2019) transformed gene analysis and molecular diagnostics[44], opening the gate to genetic engineering and recombinant DNA. Finally, DNA sequencing techniques have undergone several stages of improvement, ultimately achieving greater speed and higher data output through automation and massive sequencing. As shown in Figure 1, scientific advances paved the way for the emergence of molecular biology and its integration into genomic medicine.

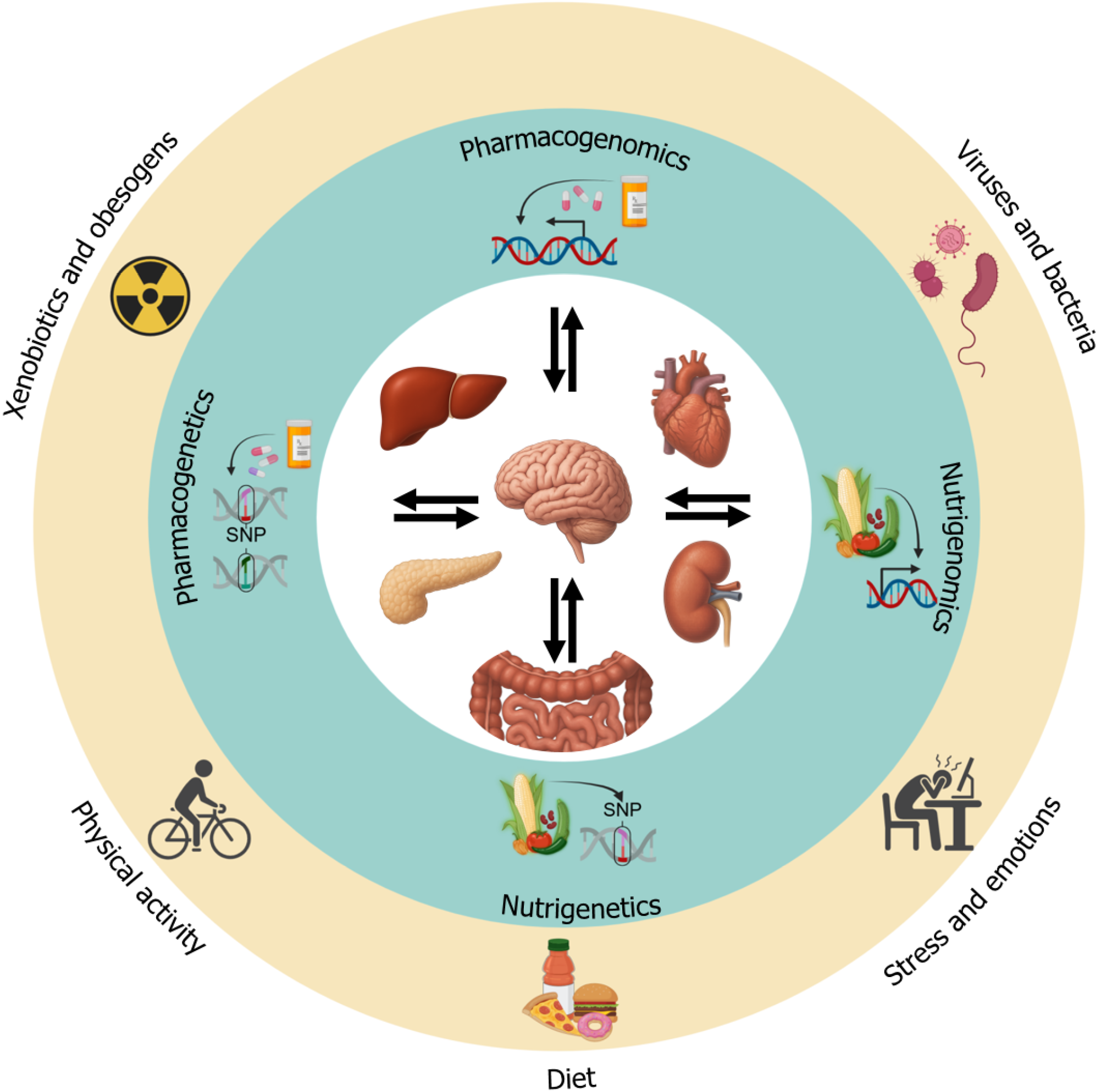

The publication of the DNA sequence blueprint of the human genome, the ultimate goal of the Human Genome Project, by the private sector and the United States National Institutes of Health marked the inception of the genomic era[44,45]. Genomics involves studying the structure and regulation of gene expression, encompassing transcription (RNA synthesis, editing, and translocation) and translation (protein synthesis) whether structural or functional and ultimately resulting in proteins that perform intracellular or extracellular functions[45]. More importantly, genomics unified the diverse biomedical sciences, which had conventionally studied cellular processes in isolation. Genomics integrates the knowledge of molecular biology (genes), biochemistry, immunology (intracellular and extracellular molecules), and cell biology (cell organization) to form the foundation for physiology (normal cell function) and pathophysiology (altered cell function), providing the basis for genomic medicine (Figure 2). It provides us with a comprehensive vision of health and disease by understanding the stages involved in gene expression under physiological conditions and interpreting what occurs when disruptions arise at any stage due to changes in protein function.

From this integration emerges the broader concept of “omics”. Genomics aligns closely with molecular biology; metabolomics pertains to the study of molecules involved in various metabolic pathways while proteomics focuses on the structure and function of proteins, particularly their biochemical and immunological properties. In the following sections, we describe how genomic medicine has evolved the study of the liver.

In ancient Greek medicine, the liver was regarded as the organ through which the gods communicated with humans, symbolizing life, intelligence, and the soul’s indestructibility due to its regenerative capacity[8]. Hippocrates emphasized two key humors, yellow and black bile (produced by the liver), which influence temperament. This belief endured, reaching colonial Latin America where the Spanish term bilioso (meaning bilious, quick-tempered) and herbal remedies to restore liver health reflected its lasting cultural and medical significance.

A turning point in hepatology came after World War II when doctors began to focus on liver research, particularly on conditions like alcoholic liver disease (ALD), viral hepatitis, and Laennec’s cirrhosis, which was then believed to be caused by malnutrition. Since World War II, our understanding of liver function and disease has undergone significant advancements. Early histopathological studies laid the groundwork for identifying and classifying viral hepatitis. Research on alcohol metabolism clarified the pathogenesis of alcoholic cirrhosis. As knowledge grew, several liver conditions were redefined: Laennec’s cirrhosis became obsolete[46,47]; non-A, non-B hepatitis was identified as hepatitis C; and cryptogenic cirrhosis was then recognized as part of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, recently renamed MASLD, highlighting progress in metabolic and genomic research[48,49].

Modern hepatology has advanced significantly with the development of liver function tests, including aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin as well as protein-based assays such as albumin and prothrombin. These biochemical markers remain the primary laboratory studies used by physicians to differentiate between acute and chronic liver damage and assess overall liver function recovery[50]. Nonetheless, as we will comment further, powerful molecular diagnostic tools will soon complement these tests.

In the mid-20th century, pathologists, clinicians, and biochemists launched further investigations into chronic liver diseases. Key figures in this movement included Hans Popper (United States) (1903-1988), Dame Sheila Sherlock (United Kingdom) (1918-2001), Ruy Pérez-Tamayo (1924-2022), and his student Marcos Rojkind-Matluk (Mexico) (1935-2011). Dr. Popper’s three-dimensional studies of cirrhosis provided critical insights into liver pathology[51]. Dr. Sherlock transformed clinical practice by introducing the needle liver biopsy, defining autoimmune liver diseases, and authoring a seminal textbook that guided generations of hepatologists[52]. In Mexico, Dr. Pérez-Tamayo, a distinguished pathologist, contributed to the experimental pathology of liver diseases[53]. Dr. Rojkind explored the molecular mechanisms of fibrosis, focusing on cell-matrix interactions and the dynamics of the extracellular matrix[54,55]. Together, their work bridged pathology, clinical insight, and the emerging field of molecular biology, establishing the multidisciplinary framework of modern hepatology.

In the 1980s during the pregenomic era, the study of molecular biology in liver diseases expanded rapidly, leading to the emergence of the field of molecular hepatology. At the Liver Research Center of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, David Shafritz (b. 1940- ) led one of the first studies on hepatocellular carcinoma, demonstrating the integration of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) genome into the human genome as an etiological factor[56,57]. Around the same time James E. Darnell Jr (b. 1930- ) developed the “run-off transcription assay”[58], a technique that enabled the study of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of liver genes during normal function, regeneration, and cirrhosis[59].

Initially, molecular hepatology and gastroenterology received little attention at academic meetings. However, by the 1980s-1990s, advances in molecular biology transformed these fields by integrating biochemistry with molecular methods, revealing mechanisms of liver gene expression from induction to protein function[60]. During this stage, advances in molecular biology, as mentioned in the previous section, with their clinical applications, led to the integration of molecular biology in medicine, enriching conventional diagnostics, which are based on biochemical markers and immunological assays, with molecular techniques.

As a result of the global scientific transition from classical pathology to molecular hepatology, Mexico embraced molecular biology in the 1990s under the leadership of Secretary of Health Jesús Kumate Rodríguez (1924-2018), who supported specialized training and research in genomic medicine. He left for posterity the famous phrase, “Whoever does not enter molecular biology is like not getting into the major leagues”[61]. Postdoctoral researchers with experience in molecular biology in medicine, who had returned to Mexico, created new laboratories in reproductive biology, psy

At the then-called National Institute of Nutrition, the first Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology laboratory was established (1989). Shortly thereafter, the first Doctorate in Molecular Biology in Medicine was created at the University of Guadalajara (1994), along with the first Department of Genomic Medicine in Hepatology at the Civil Hospital of Guadalajara (1996) in Guadalajara, Mexico[62], focusing on the study of genetic and environmental factors involved in the onset and progression of liver diseases and related conditions among the Mexicans (Figure 3).

When medical specialties were formalized in the mid-20th century, hepatology was initially grouped under the umbrella of gastroenterology and internal medicine. However, the liver, as a central and integrative organ in human physiology, has been of interest in several medical specialties. Liver diseases garnered interest across various disciplines: Pathologists led early descriptions of fibrosis and cirrhosis; geneticists studied inherited disorders; neurologists and psychiatrists examined links to hunger, satiety, and addiction; infectious disease specialists focused on hepatitis; endocrinologists addressed obesity and diabetes; oncologists investigated hepatocellular carcinoma; and transplant surgeons managed end-stage liver failure (Figure 4).

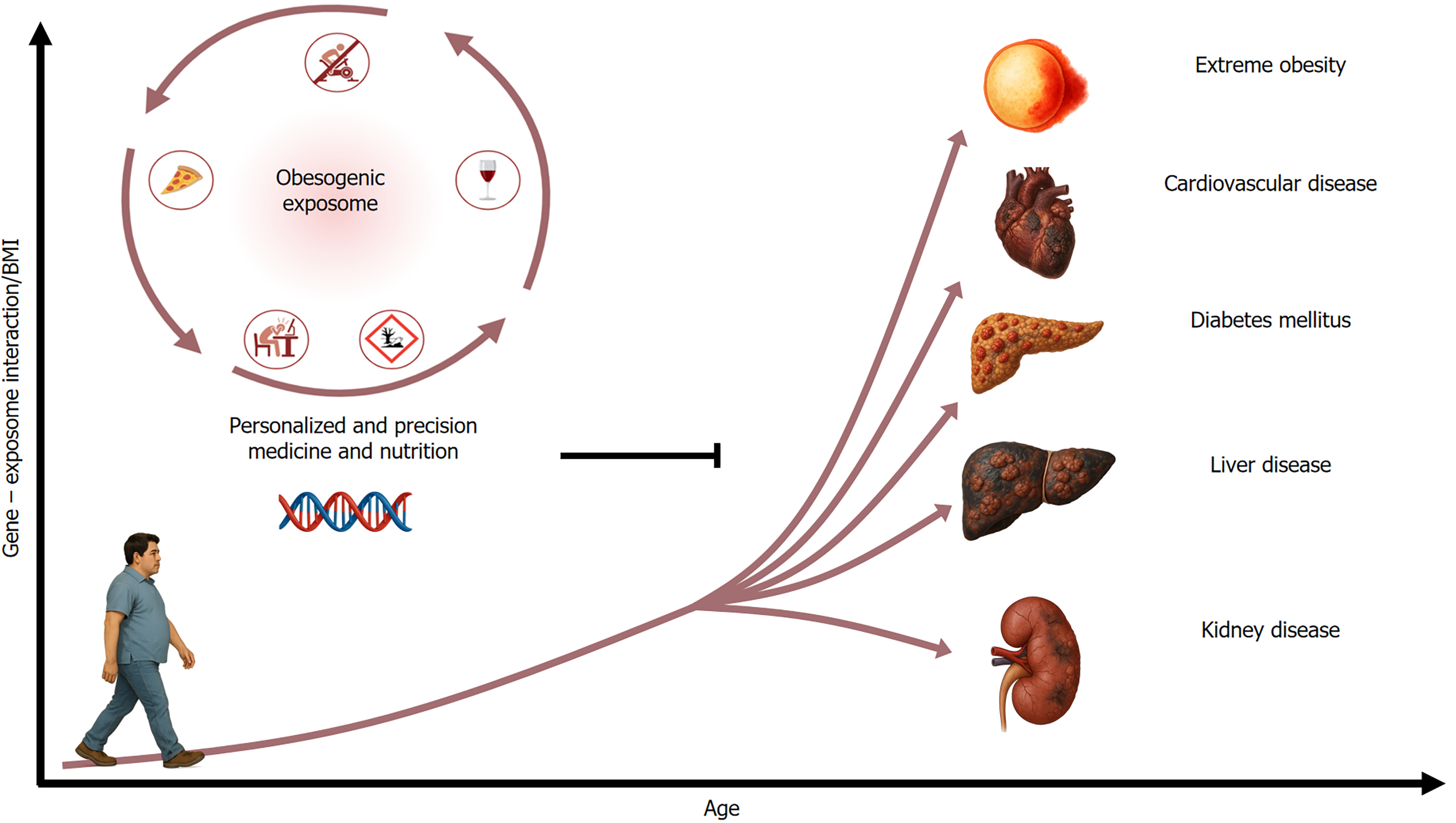

However, genomic medicine marks a new era in hepatology, driven by technological advancements in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The paradigm shift from viewing fibrosis/cirrhosis as irreversible to potentially reversible in early stages[63] mirrors similar changes in the understanding of other chronic conditions, such as T2DM, cardiovascular, and kidney diseases[64-66]. As genomics uncovered the complex interplay between genes and the exposome (the sum of environmental exposures across the lifespan, including diet, physical activity, toxins, infections, and emotional stressors)[67-69], it has become clear that enabling targeted prevention strategies could reduce chronic disease progression (Figure 5).

Unlike conventional medicine, which often targets advanced diseases, genomic medicine focuses on the genetic and exposomic factors unique to each population (Figure 6). These gene-environmental interactions influence the various stages of gene expression from induction to protein function, affecting the onset and progression of chronic diseases. Thus, the populations’ phenotypes and genotypes reflect these environmental adaptations. Genomic medicine in hepatology aims to identify allelic and genotypic variations linked to ancestry influenced by the exposome, particularly those modifying lifestyle factors such as diet and avoiding detrimental environmental exposures[70].

The role of the liver in metabolizing proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids is crucial for health. Genes are essential for expressing enzymes, receptors, and transporters, and gene expression is regulated by genetic variation and dietary (nutritional) factors, which influence the progression of chronic diseases. Specific genetic variants influence taste preferences, such as those for sweet, bitter, salty, or fatty flavors, which can impact dietary behavior. Other genes regulate lipid absorption and transportation (chylomicron formation and lipoprotein metabolism) with dysregulation contributing to atherosclerosis and steatosis in different organs[71]. Identifying these genetic variations enables earlier diagnosis and targeted lifestyle interventions as part of the genomic medicine approach in hepatology.

This framework is especially relevant in Latin America where admixed populations shaped by Amerindian, European, and African ancestries require culturally and genetically tailored healthcare approaches[70]. Studying the evolutionary gene-environment interactions in these populations can uncover unique susceptibility to liver disease. Furthermore, given the diversity of regional food cultures, medical and nutritional interventions need to be tailored accordingly. The following section explains how genomic medicine in hepatology can be effectively applied in Latin American contexts, such as Mexico.

Prevention of obesity and associated comorbidities: From a genomic perspective, the Mexican genome reflects the evolutionary gene-environment interactions that shaped the survival of First Nation (Native Amerindian) peoples in the ancestral regions of Arid America and Mesoamerica[70]. Anthropometric traits, such as skin tone, height, weight, and diet-related gene polymorphisms, have been linked to these biogeographic conditions, thereby defining the population’s phenotypic, genetic, metabolic, and sociocultural profile[72]. Colonization by Europeans and the arrival of enslaved Africans led to genetic and cultural admixture, introducing new foods and culinary traditions that eventually transformed into Mexican cuisine[73].

Until the 1970s, metabolic chronic diseases such as T2DM, MASLD, and cardiovascular disease were rare in Mexico[74]. Instead, infectious diseases and malnutrition predominated, and the diet was primarily traditional and plant-based, centered on beans, corn, squash, nopales, tomatoes, and chili with low sugar intake and small portions due to economic hardship. However, globalization has shifted dietary patterns in which festive foods have become everyday snacks; ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks have proliferated; and physical activity has declined[75,76]. These lifestyle changes, intensified after the Free Trade Agreement, led to a rise in obesity and T2DM, first observed among Amerindian migrants in the United States and later across Mexico[74,76].

Today, the Mexican population faces an evolutionary mismatch. Genes adapted for survival in resource-scarce environments now increase disease risk in an obesogenic environment[78]. Risk alleles, combined with a hepatopathogenic diet, increase the risk of chronic conditions like obesity, T2DM, and MASLD[79]. Preventing or reversing these pathogenic conditions using a genomic medicine approach has been achieved by recommending the genome-based Mexican (GENOMEX) diet, a nutrigenetic clinical trial designed by our research group to normalize anthropometric, metabolic, and behavioral traits[80]. The rationale behind the GENOMEX diet is based on the genetic landscape of the Mexican population and its food culture[73,78,79,81], incorporating traditional Mexican foods rich in nutrients that activate nutrigenomic signaling pathways[71,82]. The GENOMEX diet is also compatible with a sustainable food culture, designed to strengthen local economies and provide a foundation for national dietary guidelines[83] that align with Mexico’s genetic and cultural background, rather than relying on foreign standards, such as the Mediterranean diet[79]. Other nutrigenetic clinical trials have been conducted among the Mexican population, aiming to reduce blood lipids and low-grade inflammation[84].

Prevention of hepatitis viruses: Molecular biology-based laboratory techniques have significantly enhanced diagnostics for infectious diseases, offering greater sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional biochemical and immunological methods[85]. In the case of hepatitis viruses, these advancements were pivotal. Interestingly, the discovery of HBV relied heavily on immunological assays, which facilitated the identification of viral antigens and later supported the development of recombinant DNA vaccines for prevention[86,87]. Unlike HBV, the hepatitis C virus (HCV) was discovered using molecular cloning techniques without prior viral visualization or cultivation. Scientists extracted RNA from the plasma of infected individuals, created complementary DNA libraries, and screened for sequences that triggered immune reactions in patients with non-A, non-B hepatitis[88].

Another key contribution of molecular biology was sequencing the genomes of viral hepatitis A through E, revealing their genetic diversity and differential global distribution. HBV and HCV exhibit high genetic diversity and are classified into genotypes (A-J for HBV, 1-7 for HCV)[89,90]. HBV genotype information is particularly relevant because it enables molecular epidemiology, tracking mutations, understanding resistance mechanisms, and evaluating their impact on liver disease progression. In Latin America, for example, genotype H is predominant in Mexico while genotype F (F1-F4) is distributed across Central and South America. Notably, genotype F1 has been associated with a higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma than genotype H[91].

Conversely, HCV treatment has improved dramatically due to antiviral drugs targeting specific stages of the viral replication cycle. These therapies have significantly increased cure rates and raised hopes for the eventual eradication of the virus[92,93]. However, due to the high mutation rates of hepatitis viruses, ongoing molecular surveillance remains essential[94]. This feature is key in global migration as it facilitates the spread of non-endemic viral strains[95].

Genomic medicine has significantly deepened our understanding of hepatitis viruses by providing valuable insights into viral evolution, host-pathogen interactions, disease progression, and treatment responses. Together, these genomic approaches provide a robust framework for precision prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, cornerstones of personalized medicine in hepatology.

Prevention of ALD: Unique environmental and genetic factors shape alcohol consumption and related liver disease in Mexico. Alcohol addiction (heavy drinking) has been a public health issue since colonial times and remains so today[96], involving mainly the consumption of beer, fermented beverages, and distilled beverages(spirits)[97]. The country has one of the highest “drinking scores” and mortality rates from ALD globally despite only intermediate per-capita alcohol intake[98]. Various sociobehavioral determinants shape the pattern of consumption, which has been identified in at least three stages: (1) Stage 1, incremental weekend beer consumption; (2) Stage 2, the addition of midweek spirit drinks; and (3) Stage 3, the eventual switch to heavy intake of spirits[99].

Due to the admixture, key alcohol-metabolizing genes (ADH1B, CYP2E1, ALDH2) exhibit significant variation among individuals. These genes can form “risk” or “non-risk” haplotypes that influence alcohol dependence and liver injury. For example, protective alleles like ADH1B*2 or ALDH2*2 are virtually absent in Mexico. In contrast, the CYP2E1c2 risk allele is highly prevalent among certain native groups, likely due to historical exposure to fermented beverages such as “tejuino” and “pulque”[99]. Alongside, the TAS2R38 alanine-valine-valine (AVV) non-taster haplotype and the DRD2/ANKK1 Taq1A polymorphisms associated with brain reward and addiction are considered risk factors for alcohol abuse and ALD[99]. Thus, personalized prevention and treatment will require understanding of the relative distribution of these variants and the specific pattern of alcohol consumption, helping to identify individuals at risk for alcohol-related liver disease and addiction.

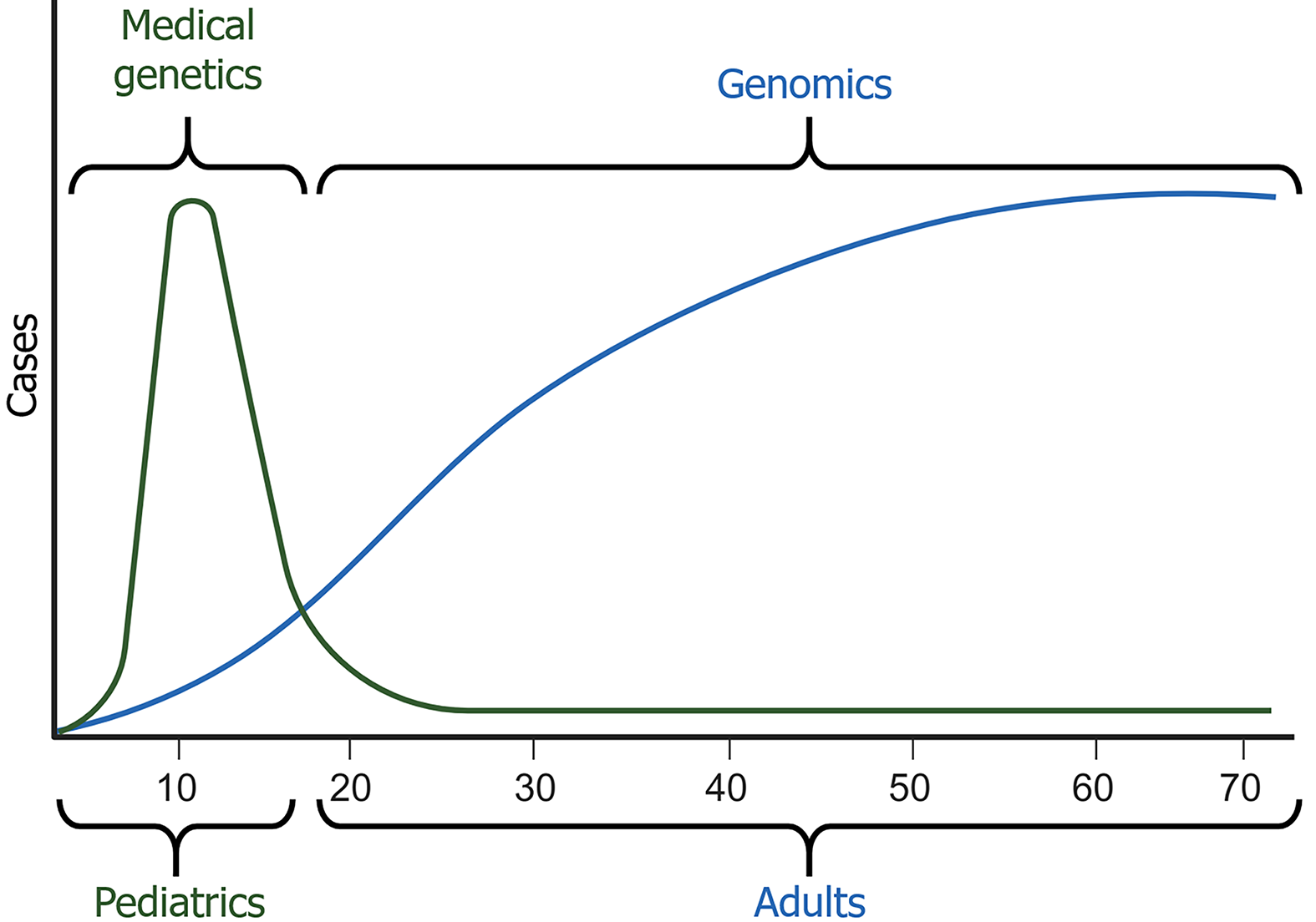

Scientific advances in the early 20th century, led by European and American researchers were disrupted by World War II. After the war, foundational disciplines such as organic and inorganic chemistry matured, and new fields, including biochemistry, pharmacology, cell biology, and immunology, emerged (Figure 2). These developments led to the creation of new postgraduate programs and the revision of medical curricula, which integrated basic sciences into clinical education. Consequently, medicine heavily emphasized pharmacology and pathophysiology while biochemistry and molecular biology remained underutilized in clinical practice. Furthermore, during that stage, medical genetics focused primarily on single genes and their inheritance, including monogenic disorders, mutations, and Mendelian traits, which appear at early stages of life. However, the turning point was the advent of molecular biology in medicine and the emergence of genomic medicine, fields linking molecular mechanisms to clinical outcomes. Unlike genetics, genomics encompasses the holistic and integrative analysis of the genome, including the regulation of gene expression, epigenetic modifications, and gene-gene and gene-exposome interactions that influence complex diseases (Figure 7). This shift highlights the need to update educational programs at all levels, encouraging health sciences students to adopt a preventative, genomic-informed approach to healthcare.

The renovation of hepatology training is essential to align with the paradigm shift toward prevention and precision medicine. Historically, hepatology has been integrated into gastroenterology training with an emphasis on the management of cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver transplantation[100,101]. However, the increasing understanding of the molecular and genetic underpinnings of liver diseases demands a broader, more forward-looking educational approach. Reorienting hepatology towards early detection and prevention strategies, integrating genomic medicine to address chronic liver diseases before they progress to irreversible stages is warranted[102]. Future hepatologists will require competencies in genomics, molecular diagnostics, and personalized therapeutic interventions. Training pathways should begin at the undergraduate level, incorporating genomic literacy into medical curricula and extending through specialty and doctoral programs that foster research skills in liver pathophysiology and public health[103]. Moreover, due to workforce shortages in hepatology, there is a necessity for expanded and diversified training models[104,105].

Developing a new generation of hepatologists who are proficient in genomics, exposomics, and preventive care is imperative for addressing the global rise in liver-related morbidity and mortality. In particular, the liver should be a primary focus in medical specialties, given its crucial role in the development and management of chronic diseases. A dedicated specialty in Hepatology with a genomic medicine perspective is urgently needed[106], especially considering the growing burden of obesity-related morbidities, such as MASLD, T2DM, liver cirrhosis, cardiovascular, and renal diseases. Finally, new postgraduate programs in Genomic Medicine are essential for generating national evidence, supporting preventive strategies, and developing clinical guidelines tailored to the unique genetic and cultural characteristics of Latin American populations[70].

Scientific advancements over the centuries have continually propelled the progress of medicine, and with the emergence of genomic medicine, this trajectory has entered a transformative phase. Genomic medicine applies genetic insights in clinical settings to enhance disease prevention, facilitate early diagnosis, and enable more effective and personalized treatments. Unlike conventional medicine, which often focuses on managing complications or late-stage conditions, genomic medicine emphasizes proactive, personalized care.

A fundamental component of this approach is the necessity for each society to analyze its population’s unique genetic makeup and cultural context. However, genomic research continues to be disproportionately concentrated on po

Latin America, despite its rich human genetic diversity, is markedly underrepresented in global genomic studies. Although the region accounts for over 8% of the world’s population and bears a significant burden of chronic diseases, it contributes only about 1.3% to global genomic datasets[107,109]. This underrepresentation poses a threat to the development of accurate and effective prevention and treatment strategies tailored to the genetic and environmental profiles of these populations.

To address this gap, several initiatives have emerged throughout the region, including the Mexican Biobank Project, the GLAD Project, and the Latin American Genomics Consortium, which aim to collect regional genetic data and establish biobanks[110-113]. Nevertheless, further efforts are necessary to build more inclusive genomic databases, promote ethical community engagement, and enhance local research capacities.

In Mexico, despite taking steps forward[114], genomic medicine knowledge remains largely derived from candidate gene associations with disease. Large-scale clinical or interventional trials in genomic medicine in hepatology, incorporating genetic findings into healthcare practice, are virtually nonexistent or in their early stages[70]. This situation must be urgently reversed through sustained investment, strategic policy support, and interdisciplinary collaboration to ensure the equitable realization of genomic medicine’s promise in improving public health[61,115].

Likewise, African countries face underrepresentation in global genomic studies despite their rich genetic diversity and the challenges their populations face in addressing health issues that can be mitigated by incorporating genomic data into clinical practice[116,117]. For example, it is well known that individuals of African ancestry have a higher risk of deve

Expanding genomic research globally is not only a scientific imperative but also a matter of health equity. Ensuring that diverse populations are adequately represented in genomic studies is crucial for developing precision medicine strategies that are effective, inclusive, and culturally sensitive[121]. Achieving this goal requires stronger international collaboration, investment in local research capacity, and the implementation of policies that respect both genetic diversity and cultural contexts.

Nonetheless, critical barriers, such as limited funding, restricted access to genomic technologies, ethical and regulatory complexities, and fragmented research infrastructure in low-income and middle-income countries, continue to impede progress. Without deliberate efforts to address these issues, genomic medicine may risk widening health disparities instead of reducing them[122,123].

Understanding how genomic traits and the exposome contribute to the development of prevalent chronic conditions is crucial for creating region-based biobanks, establishing national biochemical reference values, and developing national clinical practice guidelines, rather than relying on data extrapolated from unrelated populations. This framework lays the foundation for personalized and precision medicine in the Mexican context. In this landscape the liver stands out as a central organ due to its role in regulating numerous genes essential for maintaining metabolic balance and overall health.

Genomic medicine in hepatology aims to understand liver function and prevent chronic liver dysfunctions associated with metabolic disorders, such as dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hyperinsulinemia, which are linked to T2DM, cardiovascular diseases, and renal diseases, by integrating genetic and environmental information. Updating and redesigning educational curricula across health sciences, including medicine and nutrition, is essential to support this paradigm shift. These changes will modernize academic training and provide the basis for innovative programs in genomic medicine, equipping future professionals with the skills needed to implement this transformative approach. Such educational reforms are crucial to reducing the incidence and complications of chronic diseases while lowering regional healthcare costs and improving patient outcomes.

Finally, addressing the genomic data gap is critical for Latin America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Native territories where distinct genome-exposome architectures and interplay may influence disease susceptibility. We advocate for greater international collaboration and investment in inclusive genomic research to mitigate disparities and promote equity in precision medicine.

Leonardo Leal-Mercado, Juan P Cardenas-Benitez, Irene M Mariscal-Martinez are recipients of CONAHCYT (Mexico) scholarships as doctoral students of the PhD Program of Molecular Biology in Medicine, Health Sciences Center, University of Guadalajara.

| 1. | Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:793-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3287] [Cited by in RCA: 3339] [Article Influence: 303.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Non-communicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2020. Jun 12, 2020. [cited 29 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000490. |

| 3. | Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Barker-Collo S, Bartels DH, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bhalla K, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Boufous S, Bucello C, Burch M, Burney P, Carapetis J, Chen H, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahodwala N, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ezzati M, Feigin V, Flaxman AD, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Franklin R, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gonzalez-Medina D, Halasa YA, Haring D, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Hoen B, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Keren A, Khoo JP, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Ohno SL, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Mallinger L, March L, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGrath J, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Michaud C, Miller M, Miller TR, Mock C, Mocumbi AO, Mokdad AA, Moran A, Mulholland K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KM, Nasseri K, Norman P, O'Donnell M, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Phillips D, Pierce K, Pope CA 3rd, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Raju M, Ranganathan D, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Rivara FP, Roberts T, De León FR, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Segui-Gomez M, Shepard DS, Singh D, Singleton J, Sliwa K, Smith E, Steer A, Taylor JA, Thomas B, Tleyjeh IM, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Undurraga EA, Venketasubramanian N, Vijayakumar L, Vos T, Wagner GR, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Wilkinson JD, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh PH, Yip P, Zabetian A, Zheng ZJ, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095-2128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9500] [Cited by in RCA: 9741] [Article Influence: 695.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Manolio TA, Chisholm RL, Ozenberger B, Roden DM, Williams MS, Wilson R, Bick D, Bottinger EP, Brilliant MH, Eng C, Frazer KA, Korf B, Ledbetter DH, Lupski JR, Marsh C, Mrazek D, Murray MF, O'Donnell PH, Rader DJ, Relling MV, Shuldiner AR, Valle D, Weinshilboum R, Green ED, Ginsburg GS. Implementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is here. Genet Med. 2013;15:258-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shastry BS. SNP alleles in human disease and evolution. J Hum Genet. 2002;47:561-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chacón-Duque JC, Adhikari K, Fuentes-Guajardo M, Mendoza-Revilla J, Acuña-Alonzo V, Barquera R, Quinto-Sánchez M, Gómez-Valdés J, Everardo Martínez P, Villamil-Ramírez H, Hünemeier T, Ramallo V, Silva de Cerqueira CC, Hurtado M, Villegas V, Granja V, Villena M, Vásquez R, Llop E, Sandoval JR, Salazar-Granara AA, Parolin ML, Sandoval K, Peñaloza-Espinosa RI, Rangel-Villalobos H, Winkler CA, Klitz W, Bravi C, Molina J, Corach D, Barrantes R, Gomes V, Resende C, Gusmão L, Amorim A, Xue Y, Dugoujon JM, Moral P, González-José R, Schuler-Faccini L, Salzano FM, Bortolini MC, Canizales-Quinteros S, Poletti G, Gallo C, Bedoya G, Rothhammer F, Balding D, Hellenthal G, Ruiz-Linares A. Latin Americans show wide-spread Converso ancestry and imprint of local Native ancestry on physical appearance. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Escudero Bermello, Ana Isabel, Borroto Cruz, Eugenio Radamés, Díaz Contino, Cindy Giselle. La formación médica desde la perspectiva hipocrática. Educación Médica Superior. 2024;38. |

| 8. | Subbarayappa BV. The roots of ancient medicine: an historical outline. J Biosci. 2001;26:135-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ribatti D. Reductionism, Vitalism, and Holism. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2021;31:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sparling A. Paracelsus, a Transmutational Alchemist. Ambix. 2020;67:62-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Newman WR, Principe LM. Alchemy vs. chemistry: the etymological origins of a historiographic mistake. Early Sci Med. 1998;3:32-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | González Hernández A, Domínguez Rodríguez MV, Fabre Pi O, Cubero González A. [Descartes' influence on the development of the anatomoclinical method]. Neurologia. 2010;25:374-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ribatti D. An historical note on the cell theory. Exp Cell Res. 2018;364:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schwann TH. Microscopial researches into the accordance in the structure and growth of animals and plants. 1847. Obes Res. 1993;1:408-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Levit GS, Hoßfeld U, Naumann B, Lukas P, Olsson L. The biogenetic law and the Gastraea theory: From Ernst Haeckel's discoveries to contemporary views. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2022;338:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Haeckel E. The Evolution of Man. London: Rationalist Press Association, Limited, 2005. |

| 18. | Raudenska M, Vicar T, Gumulec J, Masarik M. Johann Gregor Mendel: the victory of statistics over human imagination. Eur J Hum Genet. 2023;31:744-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Smýkal P, von Wettberg EJB. A Commemorative Issue in Honor of 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Gregor Johann Mendel: The Genius of Genetics. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:11718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abbott S, Fairbanks DJ. Experiments on Plant Hybrids by Gregor Mendel. Genetics. 2016;204:407-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | DE Vries H. THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES BY MUTATION. Science. 1902;15:721-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Garrod AE. The incidence of alkaptonuria: a study in chemical individuality. 1902. Mol Med. 1996;2:274-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bateson P. William Bateson: a biologist ahead of his time. J Genet. 2002;81:49-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yeh BJ, Lim WA. Synthetic biology: lessons from the history of synthetic organic chemistry. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:521-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Coffey P. Cathedrals of Science: The Personalities and Rivalries That Made Modern Chemistry. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. |

| 26. | James J. From Physical Chemistry to Chemical Physics, 1913-194. 2015. [cited 29 April 2025]. Available from: http://kagakushi.org/iwhc2015/papers/25.JamesJeremiah.pdf. |

| 27. | Magner JA. Emil Fischer (1852-1919). Endocrinologist. 2004;14:239-244. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Science History Institute. Emil Fischer. [cited 29 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/scientific-biographies/emil-fischer/. |

| 29. | Frixione E, Ruiz-Zamarripa L. The "scientific catastrophe" in nucleic acids research that boosted molecular biology. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:2249-2255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Levene PA. The Structure of Yeast Nucleic ACID. J Biol Chem. 1919;40:415-424. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Science History Institute. Gilbert Newton Lewis. [cited 29 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/scientific-biographies/gilbert-newton-lewis/. |

| 32. | Rich A. Linus Pauling: chemist and molecular biologist. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;758:74-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pauling L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond. Iv. The Energy of Single Bonds And The Relative Electronegativity of Atoms. J Am Chem Soc. 1932;54:3570-3582. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1248] [Cited by in RCA: 832] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Weaver W. Molecular biology: origin of the term. Science. 1970;170:581-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Abir-Am PG. The Rockefeller Foundation and the rise of molecular biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:65-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Keros T, Borovecki F, Jemersić L, Konjević D, Roić B, Balatinec J. The centenary progress of molecular genetics. A 100th anniversary of T. H. Morgan's discoveries. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:1167-1174. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Beadle GW, Tatum EL. Genetic Control of Biochemical Reactions in Neurospora. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1941;27:499-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 887] [Cited by in RCA: 706] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Watson JD, Crick FH. Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 1953;171:737-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8617] [Cited by in RCA: 6363] [Article Influence: 87.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Crick FH, Barnett L, Brenner S, Watts-Tobin RJ. General nature of the genetic code for proteins. Nature. 1961;192:1227-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 912] [Cited by in RCA: 748] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bolivar F, Rodriguez RL, Greene PJ, Betlach MC, Heyneker HL, Boyer HW, Crosa JH, Falkow S. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene. 1977;2:95-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3957] [Cited by in RCA: 3580] [Article Influence: 73.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Soberon X, Covarrubias L, Bolivar F. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. IV. Deletion derivatives of pBR322 and pBR325. Gene. 1980;9:287-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Southern EM. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22637] [Cited by in RCA: 24805] [Article Influence: 486.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Alwine JC, Kemp DJ, Stark GR. Method for detection of specific RNAs in agarose gels by transfer to diazobenzyloxymethyl-paper and hybridization with DNA probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:5350-5354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 1379] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Mullis K, Faloona F, Scharf S, Saiki R, Horn G, Erlich H. Specific enzymatic amplification of DNA in vitro: the polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1986;51 Pt 1:263-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1654] [Cited by in RCA: 1363] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 45. | Kuska B. Beer, Bethesda, and biology: how "genomics" came into being. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | ROBERTSON AJ, COOPE R. Rales, rhonchi, and Laennec. Lancet. 1957;273:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Braillon A. Laennec's cirrhosis. Lancet. 2019;393:131-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Hsu CL, Loomba R. From NAFLD to MASLD: implications of the new nomenclature for preclinical and clinical research. Nat Metab. 2024;6:600-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Narro GEC, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Ann Hepatol. 2024;29:101133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 200.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Mousa OY, Kamath PS. A History of the Assessment of Liver Performance. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2021;18:28-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Popper H, Elias H. Histogenesis of hepatic cirrhosis studied by the threedimensional approach. Am J Pathol. 1955;31:405-441. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Doniach D, Roitt IM, Walker JG, Sherlock S. Tissue antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis, active chronic (lupoid) hepatitis, cryptogenic cirrhosis and other liver diseases and their clinical implications. Clin Exp Immunol. 1966;1:237-262. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Montfort I, Pérez-Tamayo R. Collagenase in experimental carbon tetrachloride cirrhosis of the liver. Am J Pathol. 1978;92:411-420. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Rojkind M, Giambrone MA, Biempica L. Collagen types in normal and cirrhotic liver. Gastroenterology. 1979;76:710-719. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Greenwel P, Domínguez-Rosales JA, Mavi G, Rivas-Estilla AM, Rojkind M. Hydrogen peroxide: a link between acetaldehyde-elicited alpha1(I) collagen gene up-regulation and oxidative stress in mouse hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2000;31:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Chakraborty PR, Ruiz-Opazo N, Shouval D, Shafritz DA. Identification of integrated hepatitis B virus DNA and expression of viral RNA in an HBsAg-producing human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Nature. 1980;286:531-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Wands JR, Liang TJ, Blum HE, Shafritz DA. Molecular pathogenesis of liver disease during persistent hepatitis B virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 1992;12:252-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Darnell JE Jr. Implications of RNA-RNA splicing in evolution of eukaryotic cells. Science. 1978;202:1257-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Panduro A, Shalaby F, Weiner FR, Biempica L, Zern MA, Shafritz DA. Transcriptional switch from albumin to alpha-fetoprotein and changes in transcription of other genes during carbon tetrachloride induced liver regeneration. Biochemistry. 1986;25:1414-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Rigas B. Molecular gastroenterology--implications for medical practice. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:184-186. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Panduro A, Roman S. Personalized medicine in Latin America. Per Med. 2020;17:339-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Mariscal-Martinez IM, Roman S, Panduro A. Hepatology at the Civil Hospital of Guadalajara, Fray Antonio Alcalde (HCGFAA) in the last 25 years and its international scientific productivity. Ann Hepatol. 2024;29:101423. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 63. | Dezső K, Paku S, Kóbori L, Thorgeirsson SS, Nagy P. What Makes Cirrhosis Irreversible?-Consideration on Structural Changes. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:876293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Rosenfeld RM, Grega ML, Gulati M. Lifestyle Interventions for Treatment and Remission of Type 2 Diabetes and Prediabetes in Adults: Implications for Clinicians. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2025;15598276251325802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Ergas IJ, Mauch LR, Rahbar JA, Kitazono R, Kushi LH, Misquitta R. Health Achieved Through Lifestyle Transformation (HALT): A Kaiser Permanente Diet and Lifestyle Intervention Program for Coronary Artery Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2024;18:35-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Wühl E, Schaefer F. Can we slow the progression of chronic kidney disease? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:170-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Bellamri M, Walmsley SJ, Turesky RJ. Metabolism and biomarkers of heterocyclic aromatic amines in humans. Genes Environ. 2021;43:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 68. | Heindel JJ, Lustig RH, Howard S, Corkey BE. Obesogens: a unifying theory for the global rise in obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2024;48:449-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Hwang S, Lim JE, Choi Y, Jee SH. Bisphenol A exposure and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk: a meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2018;18:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Panduro A, Roman S, Mariscal-Martinez IM, Jose-Abrego A, Gonzalez-Aldaco K, Ojeda-Granados C, Ramos-Lopez O, Torres-Reyes LA. Personalized medicine and nutrition in hepatology for preventing chronic liver disease in Mexico. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1379364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Panduro A, Roman S, Milán RG, Torres-Reyes LA, Gonzalez-Aldaco K. Personalized Nutrition to Treat and Prevent Obesity and Diabetes. In: Cheng ZY, editor. Nutritional Signaling Pathway Activities in Obesity and Diabetes. London: Royal Society of Chemistry, 2020: 272-294. |

| 72. | Vera Castañeda J. La complexión de los indios de Nueva España: composición, naturaleza y racialización en la Modernidad temprana (siglos XVI-XVII). Estud Hist Novohisp. 2023;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 73. | Roman S, Ojeda-Granados C, Panduro A. Genética y evolución de la alimentación de la población en México. Rev Endocrinol Nutr. 2013;21:42-51. |

| 74. | Vazquez Castellanos JL, Panduro A. Diabetes mellitus tipo 2: un problema epidemiológico y de emergencia en México. Investig en Salud. 2001;III:18-26. |

| 75. | Marrón-Ponce JA, Tolentino-Mayo L, Hernández-F M, Batis C. Trends in Ultra-Processed Food Purchases from 1984 to 2016 in Mexican Households. Nutrients. 2018;11:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Stevens G, Dias RH, Thomas KJ, Rivera JA, Carvalho N, Barquera S, Hill K, Ezzati M. Characterizing the epidemiological transition in Mexico: national and subnational burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Bennett PH. Type 2 diabetes among the Pima Indians of Arizona: an epidemic attributable to environmental change? Nutr Rev. 1999;57:S51-S54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Ojeda-Granados C, Abondio P, Setti A, Sarno S, Gnecchi-Ruscone GA, González-Orozco E, De Fanti S, Jiménez-Kaufmann A, Rangel-Villalobos H, Moreno-Estrada A, Sazzini M. Dietary, Cultural, and Pathogens-Related Selective Pressures Shaped Differential Adaptive Evolution among Native Mexican Populations. Mol Biol Evol. 2022;39:msab290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Roman S, Campos-Medina L, Leal-Mercado L. Personalized nutrition: the end of the one-diet-fits-all era. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1370595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Ojeda-Granados C, Panduro A, Rivera-Iñiguez I, Sepúlveda-Villegas M, Roman S. A Regionalized Genome-Based Mexican Diet Improves Anthropometric and Metabolic Parameters in Subjects at Risk for Obesity-Related Chronic Diseases. Nutrients. 2020;12:645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Silva-Zolezzi I, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Estrada-Gil J, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Uribe-Figueroa L, Contreras A, Balam-Ortiz E, del Bosque-Plata L, Velazquez-Fernandez D, Lara C, Goya R, Hernandez-Lemus E, Davila C, Barrientos E, March S, Jimenez-Sanchez G. Analysis of genomic diversity in Mexican Mestizo populations to develop genomic medicine in Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8611-8616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Mierziak J, Kostyn K, Boba A, Czemplik M, Kulma A, Wojtasik W. Influence of the Bioactive Diet Components on the Gene Expression Regulation. Nutrients. 2021;13:3673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Unar-Munguía M, Cervantes-Armenta MA, Rodríguez-Ramírez S, Bonvecchio Arenas A, Fernández Gaxiola AC, Rivera JA. Mexican national dietary guidelines promote less costly and environmentally sustainable diets. Nat Food. 2024;5:703-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Pérez-Beltrán YE, González-Becerra K, Rivera-Iñiguez I, Martínez-López E, Ramos-Lopez O, Alcaraz-Mejía M, Rodríguez-Echevarría R, Sáyago-Ayerdi SG, Mendivil EJ. A Nutrigenetic Strategy for Reducing Blood Lipids and Low-Grade Inflammation in Adults with Obesity and Overweight. Nutrients. 2023;15:4324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Josko D. Molecular virology in the clinical laboratory. Clin Lab Sci. 2010;23:231-236. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Block TM, Alter HJ, London WT, Bray M. A historical perspective on the discovery and elucidation of the hepatitis B virus. Antiviral Res. 2016;131:109-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4996] [Cited by in RCA: 4671] [Article Influence: 126.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 89. | Sukowati CHC, Jayanti S, Turyadi T, Muljono DH, Tiribelli C. Hepatitis B virus genotypes in precision medicine of hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma: Where we are now. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024;16:1097-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Paraskevis D, Kostaki EG, Kramvis A, Magiorkinis G. Classification, Genetic Diversity and Global Distribution of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Genotypes and Subtypes. In: Hatzakis A, editor. Hepatitis C: Epidemiology, Prevention and Elimination. New York: Springer, 2021: 55-69. |

| 91. | Panduro A, Roman S, Laguna-Meraz S, Jose-Abrego A. Hepatitis B Virus Genotype H: Epidemiological, Molecular, and Clinical Characteristics in Mexico. Viruses. 2023;15:2186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 92. | Hiebert L, Ward JW. Strategic information to guide elimination of viral hepatitis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:291-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Fleurence RL, Alter HJ, Collins FS, Ward JW. Global Elimination of Hepatitis C Virus. Annu Rev Med. 2025;76:29-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Xie C, Lu D. Evolution and diversity of the hepatitis B virus genome: Clinical implications. Virology. 2024;598:110197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Baggaley RF, Zenner D, Bird P, Hargreaves S, Griffiths C, Noori T, Friedland JS, Nellums LB, Pareek M. Prevention and treatment of infectious diseases in migrants in Europe in the era of universal health coverage. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e876-e884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Trichia E, Alegre-Díaz J, Aguilar-Ramirez D, Ramirez-Reyes R, Garcilazo-Ávila A, González-Carballo C, Bragg F, Friedrichs LG, Herrington WG, Holland L, Torres J, Wade R, Collins R, Peto R, Berumen J, Tapia-Conyer R, Kuri-Morales P, Emberson JR. Alcohol and mortality in Mexico: prospective study of 150 000 adults. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:e907-e915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Centro de Investigación Económica y Presupuestaria. Information on the consumption of alcoholic beverages in Mexico. 2023. [cited 29 April 2025]. Available from: https://ciep.mx/information-on-the-consumption-of-alcoholic-beverages-in-mexico/. |

| 98. | Reséndiz Escobar E, Bustos Gamino M, Mujica Salazar R, Soto Hernández I, Cañas Martínez V, Fleiz Bautista C, Gutiérrez López M, Amador Buenabad N, Medina-Mora N, Villatoro Velázquez J. National trends in alcohol consumption in Mexico: results of the National Survey on Drug, Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption 2016-2017. Salud Mental. 2018;41:7-16. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Panduro A, Rivera-Iñiguez I, Ramos-Lopez O, Roman S. Genes and Alcoholism: Taste, Addiction, and Metabolism. In: Preedy VR, editor. Neuroscience of Alcohol. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2019: 483-491. |

| 100. | Gores GJ. Academic gastroenterology and hepatology: training tracts and competencies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:234-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Luxon BA. Training for a career in hepatology: which path to take? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:76-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Halegoua-De Marzio DL, Herrine SK. Training the next generation of hepatologist: What will they need to know? Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2015;5:129-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Wilcox RL, Adem PV, Afshinnekoo E, Atkinson JB, Burke LW, Cheung H, Dasgupta S, DeLaGarza J, Joseph L, LeGallo R, Lew M, Lockwood CM, Meiss A, Norman J, Markwood P, Rizvi H, Shane-Carson KP, Sobel ME, Suarez E, Tafe LJ, Wang J, Haspel RL. The Undergraduate Training in Genomics (UTRIG) Initiative: early & active training for physicians in the genomic medicine era. Per Med. 2018;15:199-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Talwalkar JA, Oxentenko AS, Katzka DA. Health care-delivery research-training opportunities in gastroenterology and hepatology. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:878-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Russo MW, Koteish AA, Fuchs M, Reddy KG, Fix OK. Workforce in hepatology: Update and a critical need for more information. Hepatology. 2017;65:336-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Zheng M, Allington G, Vilarinho S. Genomic medicine for liver disease. Hepatology. 2022;76:860-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Guglielmi G. Facing up to injustice in genome science. Nature. 2019;568:290-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Sirugo G, Williams SM, Tishkoff SA. The Missing Diversity in Human Genetic Studies. Cell. 2019;177:26-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 909] [Article Influence: 151.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Popejoy AB, Fullerton SM. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016;538:161-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 871] [Cited by in RCA: 1299] [Article Influence: 129.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Sohail M, Moreno-Estrada A. The Mexican Biobank Project promotes genetic discovery, inclusive science and local capacity building. Dis Model Mech. 2024;17:dmm050522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Sohail M, Palma-Martínez MJ, Chong AY, Quinto-Cortés CD, Barberena-Jonas C, Medina-Muñoz SG, Ragsdale A, Delgado-Sánchez G, Cruz-Hervert LP, Ferreyra-Reyes L, Ferreira-Guerrero E, Mongua-Rodríguez N, Canizales-Quintero S, Jimenez-Kaufmann A, Moreno-Macías H, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Auckland K, Cortés A, Acuña-Alonzo V, Gignoux CR, Wojcik GL, Ioannidis AG, Fernández-Valverde SL, Hill AVS, Tusié-Luna MT, Mentzer AJ, Novembre J, García-García L, Moreno-Estrada A. Mexican Biobank advances population and medical genomics of diverse ancestries. Nature. 2023;622:775-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Borda V, Loesch DP, Guo B, Laboulaye R, Veliz-Otani D, French JN, Leal TP, Gogarten SM, Ikpe S, Gouveia MH, Mendes M, Abecasis GR, Alvim I, Arboleda-Bustos CE, Arboleda G, Arboleda H, Barreto ML, Barwick L, Bezzera MA, Blangero J, Borges V, Caceres O, Cai J, Chana-Cuevas P, Chen Z, Custer B, Dean M, Dinardo C, Domingos I, Duggirala R, Dieguez E, Fernandez W, Ferraz HB, Gilliland F, Guio H, Horta B, Curran JE, Johnsen JM, Kaplan RC, Kelly S, Kenny EE, Konkle BA, Kooperberg C, Lescano A, Lima-Costa MF, Loos RJF, Manichaikul A, Meyers DA, Naslavsky MS, Nickerson DA, North KE, Padilla C, Preuss M, Raggio V, Reiner AP, Rich SS, Rieder CR, Rienstra M, Rotter JI, Rundek T, Sacco RL, Sanchez C, Sankaran VG, Santos-Lobato BL, Schumacher-Schuh AF, Scliar MO, Silverman EK, Sofer T, Lasky-Su J, Tumas V, Weiss ST; Latin American Research Consortium on the Genetics of Parkinson’s Disease (LARGE-PD); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Stroke Genetics Network (SiGN) Consortium; Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) Population Genetics Working Group, Mata IF, Hernandez RD, Tarazona-Santos E, O'Connor TD. Genetics of Latin American Diversity Project: Insights into population genetics and association studies in admixed groups in the Americas. Cell Genom. 2024;4:100692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Corral-Frias N, Nunez D, Ota V, Cárcamo J, Machado C, Hernandez Amaya LC, Velásquez Toledo MM, Nagamatsu S, Dunn E, Torres-Hernández B, Lattig C, Giusti-Rodriguez P, Montalvo-Ortiz J, Peterson R. 21. Advancing the understanding of Depression Genetics: An Introduction to the Major Depression Working Group of The Latin American Genomics Consortium. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 75 Suppl 1:S68. |

| 114. | Jimenez-Sanchez G, Silva-Zolezzi I, Hidalgo A, March S. Genomic medicine in Mexico: initial steps and the road ahead. Genome Res. 2008;18:1191-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Bravo ML, Santiago-Angelino TM, González-Robledo LM, Nigenda G, Seiglie JA, Serván-Mori E. Incorporating genomic medicine into primary-level health care for chronic non-communicable diseases in Mexico: A qualitative study. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020;35:1426-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | H3Africa Consortium; Rotimi C, Abayomi A, Abimiku A, Adabayeri VM, Adebamowo C, Adebiyi E, Ademola AD, Adeyemo A, Adu D, Affolabi D, Agongo G, Ajayi S, Akarolo-Anthony S, Akinyemi R, Akpalu A, Alberts M, Alonso Betancourt O, Alzohairy AM, Ameni G, Amodu O, Anabwani G, Andersen K, Arogundade F, Arulogun O, Asogun D, Bakare R, Balde N, Baniecki ML, Beiswanger C, Benkahla A, Bethke L, Boehnke M, Boima V, Brandful J, Brooks AI, Brosius FC, Brown C, Bucheton B, Burke DT, Burnett BG, Carrington-Lawrence S, Carstens N, Chisi J, Christoffels A, Cooper R, Cordell H, Crowther N, Croxton T, de Vries J, Derr L, Donkor P, Doumbia S, Duncanson A, Ekem I, El Sayed A, Engel ME, Enyaru JC, Everett D, Fadlelmola FM, Fakunle E, Fischbeck KH, Fischer A, Folarin O, Gamieldien J, Garry RF, Gaseitsiwe S, Gbadegesin R, Ghansah A, Giovanni M, Goesbeck P, Gomez-Olive FX, Grant DS, Grewal R, Guyer M, Hanchard NA, Happi CT, Hazelhurst S, Hennig BJ, Hertz- C, Fowler, Hide W, Hilderbrandt F, Hugo-Hamman C, Ibrahim ME, James R, Jaufeerally-Fakim Y, Jenkins C, Jentsch U, Jiang PP, Joloba M, Jongeneel V, Joubert F, Kader M, Kahn K, Kaleebu P, Kapiga SH, Kassim SK, Kasvosve I, Kayondo J, Keavney B, Kekitiinwa A, Khan SH, Kimmel P, King MC, Kleta R, Koffi M, Kopp J, Kretzler M, Kumuthini J, Kyobe S, Kyobutungi C, Lackland DT, Lacourciere KA, Landouré G, Lawlor R, Lehner T, Lesosky M, Levitt N, Littler K, Lombard Z, Loring JF, Lyantagaye S, Macleod A, Madden EB, Mahomva CR, Makani J, Mamven M, Marape M, Mardon G, Marshall P, Martin DP, Masiga D, Mason R, Mate-Kole M, Matovu E, Mayige M, Mayosi BM, Mbanya JC, McCurdy SA, McCarthy MI, McIlleron H, Mc'Ligeyo SO, Merle C, Mocumbi AO, Mondo C, Moran JV, Motala A, Moxey-Mims M, Mpoloka WS, Msefula CL, Mthiyane T, Mulder N, Mulugeta Gh, Mumba D, Musuku J, Nagdee M, Nash O, Ndiaye D, Nguyen AQ, Nicol M, Nkomazana O, Norris S, Nsangi B, Nyarko A, Nyirenda M, Obe E, Obiakor R, Oduro A, Ofori-Acquah SF, Ogah O, Ogendo S, Ohene-Frempong K, Ojo A, Olanrewaju T, Oli J, Osafo C, Ouwe Missi Oukem-Boyer O, Ovbiagele B, Owen A, Owolabi MO, Owolabi L, Owusu-Dabo E, Pare G, Parekh R, Patterton HG, Penno MB, Peterson J, Pieper R, Plange-Rhule J, Pollak M, Puzak J, Ramesar RS, Ramsay M, Rasooly R, Reddy S, Sabeti PC, Sagoe K, Salako T, Samassékou O, Sandhu MS, Sankoh O, Sarfo FS, Sarr M, Shaboodien G, Sidibe I, Simo G, Simuunza M, Smeeth L, Sobngwi E, Soodyall H, Sorgho H, Sow Bah O, Srinivasan S, Stein DJ, Susser ES, Swanepoel C, Tangwa G, Tareila A, Tastan Bishop O, Tayo B, Tiffin N, Tinto H, Tobin E, Tollman SM, Traoré M, Treadwell MJ, Troyer J, Tsimako-Johnstone M, Tukei V, Ulasi I, Ulenga N, van Rooyen B, Wachinou AP, Waddy SP, Wade A, Wayengera M, Whitworth J, Wideroff L, Winkler CA, Winnicki S, Wonkam A, Yewondwos M, sen T, Yozwiak N, Zar H. Research capacity. Enabling the genomic revolution in Africa. Science. 2014;344:1346-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Munung NS, Mayosi BM, de Vries J. Genomics research in Africa and its impact on global health: insights from African researchers. Glob Health Epidemiol Genom. 2018;3:e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Olono A, Mitesser V, Happi A, Happi C. Building genomic capacity for precision health in Africa. Nat Med. 2024;30:1856-1864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Jongeneel CV, Kotze MJ, Bhaw-Luximon A, Fadlelmola FM, Fakim YJ, Hamdi Y, Kassim SK, Kumuthini J, Nembaware V, Radouani F, Tiffin N, Mulder N. A View on Genomic Medicine Activities in Africa: Implications for Policy. Front Genet. 2022;13:769919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Omotoso OE, Teibo JO, Atiba FA, Oladimeji T, Adebesin AO, Babalghith AO. Bridging the genomic data gap in Africa: implications for global disease burdens. Global Health. 2022;18:103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Alemu R, Sharew NT, Arsano YY, Ahmed M, Tekola-Ayele F, Mersha TB, Amare AT. Multi-omics approaches for understanding gene-environment interactions in noncommunicable diseases: techniques, translation, and equity issues. Hum Genomics. 2025;19:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Lee W, Yan J, Fooks K, Tafler A, Banglorewala P, Barwick M, Dobrow M, Friedman J, Marshall C, Hayeems R. P477: Barriers and facilitators to implementing genomic medicine: A scoping review of the global landscape*. Genet Med Open. 2024;2:101376. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 123. | Perenguez M, Ramírez-montaño D, Candelo E, Echavarria H, De La Torre A. Genomic Medicine: Perspective of the Challenges for the Implementation of Preventive, Predictive, and Personalized Medicine in Latin America. Curr Pharmacogenomics Pers Med. 2024;21:51-57. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/