Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v18.i1.114891

Revised: October 29, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 97 Days and 18.2 Hours

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignant tumors of the digestive system worldwide, the prognosis of patients with advanced GC remains poor.

To evaluate the combined expression characteristics of cancer stem cell markers CD24 and CD133 in GC pathological tissues, and to explore their association with patients’ clinicopathological parameters and postoperative survival outcomes.

A total of 304 GC patients who underwent surgical treatment in our hospital from January 2018 to January 2020 were retrospectively included. Immunohistochemi

Among the 304 patients, 155 cases (50.99%) were CD24 positive, including 91 low-expression and 64 high-expression; 133 cases (43.75%) were CD133 positive, including 81 low-expression and 52 high-expression. There were 74 cases (24.34%) with double positivity and 81 cases (26.64%) with double negativity. Compared with tumor tissues, the positive rates of CD24 and CD133 in normal gastric tissues and adjacent tissues were significantly lower (P < 0.05). Univariate analysis showed that co-expression of CD24 and CD133 in GC tissues was significantly correlated with tumor size, Lauren classification, T stage, N stage, and vascular invasion (P < 0.05), but not with patient age, gender, tumor site, World Health Organization histological classification, or M stage (P > 0.05). Further multivariate regression analysis suggested that tumor size, T stage, N stage, and vascular invasion were inde

CD24 and CD133 exhibit high positive detection rates in GC tissues, and their co-positivity is closely associated with tumor stage progression and significantly indicates unfavorable survival outcomes. The co-expression of CD24/CD133 may reflect higher aggressiveness and metastatic potential of GC, serving as a potential prognostic marker and a direction for targeted therapeutic strategies. However, as this is a single-center retrospective study with limitations such as patient loss to follow-up and sample size, further prospective, multicenter, and mecha

Core Tip: CD24 and CD133 exhibit high positive detection rates in gastric cancer tissues. The co-expression of CD24 and CD133 was closely related to the advanced tumor stage. Co-positivity of CD24 and CD133 predicts poor survival. The co-expression of CD24/CD133 may reflect the higher invasive and metastatic potential of gastric cancer. This combined in

- Citation: Ma CX, Chen J, Wang JL, Pei S, Zhang ZJ, Xie YS, He X. Co-expression of cancer stem cell markers CD24 and CD133 in gastric cancer tissues: Clinicopathological and prognostic significance. World J Stem Cells 2026; 18(1): 114891

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v18/i1/114891.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v18.i1.114891

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignant tumors of the digestive system worldwide. According to data released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, GC ranks among the top five in the global spectrum of malignant tumor incidence, with a particularly high prevalence in East Asia, where Chinese patients account for a significant proportion of global cases[1]. Although in recent years the overall survival (OS) rate of some patients has improved due to the widespread use of endoscopic screening, advances in surgical techniques, and the introduction of emerging therapies such as targeted therapy and immunotherapy, the prognosis of patients with advanced GC remains poor. Factors such as tumor heterogeneity, lack of typical clinical manifestations in the early stages, and the high risk of recurrence and metastasis seriously affect treatment outcomes and long-term survival[2-4]. Therefore, exploring novel biomarkers to assist in assessing disease progression and predicting patient prognosis is of great significance for opti

In recent years, research on cancer stem cells has gradually become a hotspot in the field of oncology. Cancer stem cells are considered a small subset of cells with self-renewal, unlimited proliferation, and multidirectional differentiation potential, capable of driving tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and recurrence[5,6]. Increasing evidence[7-9] indicates that cancer stem cells are not only closely related to chemo- and radio-resistance but may also represent an important biological basis for poor tumor prognosis. Hence, identifying surface molecules that can accurately mark cancer stem cells and further investigating their clinical implications are critical for elucidating the mechanisms of GC development and improving clinical management strategies.

Among the reported cancer stem cell markers, CD24 and CD133 have attracted considerable attention. CD24 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein widely distributed on the surface of hematopoietic cells and various solid tumor cells, and studies have shown that it plays roles in promoting cell adhesion, migration, signal transduction, and immune evasion[10,11]. CD133, also known as prominin-1, is a pentaspan transmembrane glycoprotein first identified on the surface of hematopoietic stem cells. It has since been widely confirmed to be highly expressed in multiple solid tumors, such as colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma, and is closely associated with tumor aggressiveness and resistance to therapy[12,13]. Previous studies have suggested that the individual expression of CD24 or CD133 may be related to the malignant behavior of GC, but the combined expression patterns of the two markers in tumor tissues and their predictive value for clinical outcomes remain insufficiently explored[14,15].

Based on this background, the present study retrospectively analyzed pathological tissue specimens from 304 GC patients, examining the expression of CD24 and CD133 in tumor tissues, adjacent tissues, and normal gastric mucosa. Combined with clinicopathological parameters and follow-up data, the study further investigated the relationship between their co-expression and tumor stage, infiltration, metastasis, and prognosis. The aim was to elucidate the role of CD24/CD133 double positivity in the development and progression of GC, assess its potential value in prognostic evaluation and treatment decision-making, and provide reference for future clinical applications.

This study was a single-center retrospective study. The study population consisted of patients who underwent resection in the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery of our hospital between October 2018 and June 2020 and were pathologically confirmed with primary GC. A total of 304 patients were included and finally analyzed. Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients were newly diagnosed with GC and underwent surgery in our hospital; (2) Pathology confirmed primary GC (based on postoperative paraffin-embedded sections); (3) Adequate paraffin-embedded tissue blocks (tumor tissue and adjacent/normal gastric mucosa samples available) were completely preserved; and (4) Outpatient and inpatient medical records, intraoperative and pathology reports, and follow-up data were relatively complete, allowing for acquisition of main clinicopathological variables and survival outcomes. Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with a history of or concurrent malignant tumors in other systems; (2) Patients who received systemic therapy before surgery (such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy/targeted or immunotherapy) that could significantly alter the expression of tissue bio

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital [Approval No. KJCS2018(13)] and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed written informed consent forms.

Tissue source: All specimens were obtained from routine postoperative formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples. For each case, one representative tumor tissue block was prioritized; when possible, paired adjacent tissue and normal gastric mucosa samples distant from the lesion were collected as controls. To ensure standardization, in this study, “adjacent tissue” was defined as tissue ≥ 2 cm away from the gross tumor margin without visible lesions; “normal gastric tissue” was defined as tissue ≥ 5 cm away from the tumor, pathologically confirmed to be free of tumor infiltration or dysplasia. Tissue sections: 4-μm consecutive slices were cut from paraffin blocks, mounted on slides, and baked for later use.

To ensure consistency across specimens, all staining procedures were carried out in the same laboratory by the same personnel, strictly following the steps below: Dewaxing and rehydration: 4 μm paraffin-embedded tissue sections were mounted on slides, dewaxed in xylene twice for 5-10 minutes each, then immersed sequentially in 100%, 95%, 80%, and 70% ethanol for 3-5 minutes, followed by rehydration with distilled water until fully hydrated. Antigen retrieval: Sections were placed in citrate buffer (pH = 6.0) and underwent microwave heat-induced epitope retrieval: High heat for 8 minutes, low heat for 10 minutes; then cooled naturally to room temperature. Blocking endogenous peroxidase: Sections were incubated in 3% H2O2 at room temperature for 10 minutes to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity, followed by phosphate buffered saline washes (3 times, 3-5 minutes each). Blocking nonspecific binding: Sections were incubated with 5% normal goat serum at room temperature for 20-30 minutes to reduce nonspecific background staining. Primary antibody incubation: CD24 was detected using an antibody from Proteintech (IL, United States); CD133 was detected using a rabbit recombinant monoclonal antibody from Abcam (United Kingdom). Both antibodies were diluted at 1:100 and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibody incubation and chromogenic detection: HRP-labeled secondary antibody was incubated at room temperature for 30-60 minutes; DAB chromogenic reaction was applied for 3-10 minutes (microscopically monitored and terminated promptly to avoid excessive background staining). Controls: Each batch included positive control sections (tumor tissues known to express CD24 or CD133) and negative controls (omitting the primary antibody step) to monitor staining specificity and inter-batch quality. Counterstaining, dehydration, clearing, and mounting: After chromogenic detection, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (about 1-2 minutes), de

To achieve quantitative comparison, this study adopted the semi-quantitative immunoreactive score (IRS) method[16] for each section: Staining intensity score (I): 0 (no staining), 1 (weak staining), 2 (moderate staining), 3 (strong staining). Percentage of positive cells score (P): 0 (< 5% positive cells), 1 (5%-25%), 2 (26%-50%), 3 (51%-75%), 4 (> 75%). IRS was calculated as IRS = I × P, ranging from 0-12. Expression grading: IRS = 0 defined as negative (-); IRS 1-8 defined as low expression (+); IRS 9-12 defined as high expression (++). According to the staining results of the two markers, patients were divided into four groups: CD24+/CD133+ (double-positive group); CD24+/CD133- (CD24 single-positive group); CD24-/CD133+ (CD133 single-positive group); CD24-/CD133- (double-negative group).

Clinicopathological variables were extracted item by item from inpatient records, operative notes, and pathology reports, including but not limited to: Patient age, sex, maximum tumor diameter (cm), tumor location (upper, middle, lower, ≥ 2 regions, or remnant stomach), World Health Organization histological classification, Lauren classification, vascular invasion (including blood vessel/Lymphatic invasion), primary tumor infiltration depth (T stage), lymph node metastasis (N stage), distant metastasis (M stage), and vascular invasion (including blood vessel/Lymphatic invasion). Tumor staging was performed and stratified according to the 8th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer/tumor-node-metastasis[17].

Follow-up method: Based on the hospital follow-up system, survival status, recurrence/metastasis, and death information were obtained through outpatient follow-up, telephone follow-up, and electronic medical record review. For patients who could not be contacted, the last contact date was recorded as the date of loss to follow-up, and such cases were censored in survival analysis (right-censored). In this study, “OS” was defined as the time from the date of surgery to death from any cause (death date as endpoint). Patients without death events were censored at the last follow-up date. Loss to follow-up handling: Patients lost to follow-up were right-censored at the last known follow-up time.

All immunohistochemical sections were independently scored in a blinded manner by two experienced pathologists (each with ≥ 10 years of experience in gastrointestinal tumor pathology) without knowledge of clinical outcomes or other marker results. In case of disagreement, the two reviewers jointly re-examined the slides to reach consensus. Positive and negative controls were included in each daily/batch experiment, and inter-batch variations were recorded; if staining deviation occurred in a batch, restaining was performed or the batch was excluded and retested.

All data were entered by dedicated researchers and double-checked before statistical analysis using SPSS (version 25.0); graphs were prepared using GraphPad Prism and other software. Categorical data were expressed as n (%); intergroup comparisons were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (when expected counts < 5). Spearman rank correlation analysis was used to assess the correlation between CD24 and CD133 expression intensity. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was applied to identify independent risk factors influencing CD24/CD133 co-expression, with results presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival differences between groups were compared using the Log-rank test. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

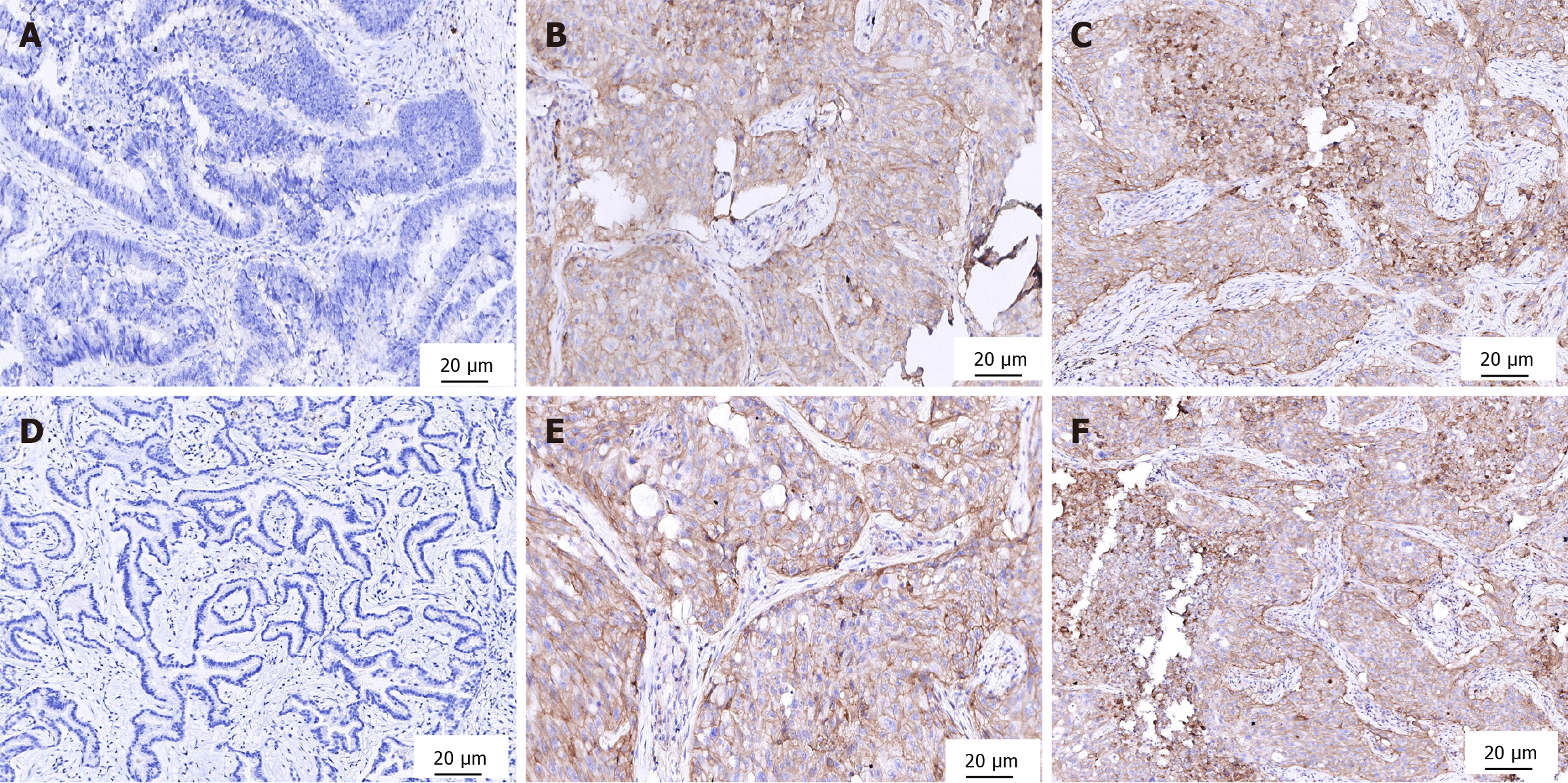

CD24 was commonly expressed in the cell membrane with mild cytoplasmic staining, while CD133 was mainly expressed in the cell membrane (also observed as punctate cytoplasmic staining). In interpretation, specific staining of tumor cells was regarded as a positive signal, whereas nonspecific staining of inflammatory cells and stroma was excluded. Among 304 patients, 155 cases (50.99%) were positive for CD24, including 91 cases with low expression and 64 cases with high expression; 133 cases (43.75%) were positive for CD133, including 81 cases with low expression and 52 cases with high expression. Double-positive cases were 74 (24.34%), and double-negative cases were 81 (26.64%), as shown in Figure 1.

Compared with cancer tissues, the positivity rates of CD24 and CD133 were significantly lower in normal gastric tissue and adjacent tissue (P < 0.05). However, no significant difference in positivity rates of CD24 and CD133 was found bet

Univariate analysis showed that co-expression of CD24 and CD133 in GC tissues was significantly associated with tumor diameter, Lauren classification, T stage, N stage, and vascular invasion (P < 0.05), but not with age, sex, tumor site, World Health Organization pathological type, or M stage (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 2.

| Clinicopathological parameter | CD24/CD133 double-positive | χ2 | P value | |

| Yes (n = 74) | No (n = 230) | |||

| Sex | 0.493 | 0.482 | ||

| Male | 40 (54.05) | 135 (58.70) | ||

| Female | 34 (45.95) | 95 (41.30) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.047 | 0.827 | ||

| < 60 | 13 (17.57) | 43 (18.70) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 61 (82.43) | 187 (81.30) | ||

| Tumor site | 0.448 | 0.503 | ||

| Upper | 4 (5.41) | 11 (4.78) | ||

| Middle | 8 (10.81) | 36 (15.65) | ||

| Lower | 60 (81.08) | 178 (77.39) | ||

| ≥ 2 regions or remnant stomach | 2 (2.70) | 5 (2.17) | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 35.494 | < 0.001 | ||

| < 5 | 23 (31.08) | 161 (70.00) | ||

| ≥ 5 | 51 (68.92) | 69 (30.00) | ||

| WHO classification | 3.022 | 0.082 | ||

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | 4 (5.41) | 8 (3.48) | ||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma | 59 (79.73) | 202 (87.83) | ||

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 2 (2.70) | 6 (2.61) | ||

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 9 (12.16) | 14 (6.09) | ||

| Lauren classification | 5.469 | 0.019 | ||

| Intestinal type | 46 (62.16) | 175 (76.09) | ||

| Diffuse type | 28 (37.84) | 55 (23.91) | ||

| T stage | 41.651 | < 0.001 | ||

| T1 | 0 (0.00) | 24 (10.43) | ||

| T2 | 4 (5.41) | 55 (23.91) | ||

| T3 | 15 (20.27) | 78 (33.91) | ||

| T4 | 55 (74.32) | 73 (31.74) | ||

| N stage | 12.854 | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | 4 (5.41) | 27 (11.74) | ||

| N1 | 10 (13.51) | 64 (27.83) | ||

| N2 | 25 (33.78) | 81 (35.22) | ||

| N3 | 35 (47.30) | 58 (25.22) | ||

| M stage | 2.012 | 0.156 | ||

| M0 | 8 (10.81) | 12 (5.22) | ||

| M1 | 66 (89.19) | 218 (94.78) | ||

| Vascular invasion | 16.925 | < 0.001 | ||

| Present | 13 (17.57) | 7 (3.04) | ||

| Absent | 61 (82.43) | 223 (96.96) | ||

Using CD24/CD133 double expression in GC tissue as the dependent variable (double positive = 1, double negative = 0), variables with significant differences in Table 3 were entered as independent variables and coded. Logistic regression analysis showed that tumor diameter, T stage, N stage, and vascular invasion were independent risk factors promoting CD24/CD133 double-positive expression, as shown in Table 4.

| Independent variable | Assignment method |

| Tumor size | < 5 cm = 0; ≥ 5 cm = 1 |

| Lauren classification | Intestinal type = 0; diffuse type = 1 |

| T stage | T1-T2 = 0; T3-T4 = 1 |

| N stage | N0-N1 = 0; N2-N3 = 1 |

| Vascular invasion | Absent = 0; present = 1 |

| Variable | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Tumor size | 1.215 | 0.382 | 10.104 | 0.001 | 3.37 | 1.60-7.08 |

| Lauren classification | 0.467 | 0.345 | 1.835 | 0.176 | 1.61 | 0.81-3.16 |

| T stage | 1.524 | 0.431 | 12.509 | < 0.001 | 4.59 | 1.98-10.64 |

| N stage | 1.002 | 0.397 | 6.363 | 0.012 | 2.72 | 1.25-5.90 |

| Vascular invasion | 1.876 | 0.562 | 11.143 | < 0.001 | 6.53 | 2.17-19.67 |

| Constant | -2.037 | 0.529 | 14.829 | < 0.001 |

Cross-distribution analysis of CD24 and CD133 expression grading (negative/Low/high) in 304 GC tissues was per

| CD133 expression | CD24 expression | ||

| - | + | ++ | |

| - | 90 | 81 | 0 |

| + | 59 | 0 | 22 |

| ++ | 0 | 10 | 42 |

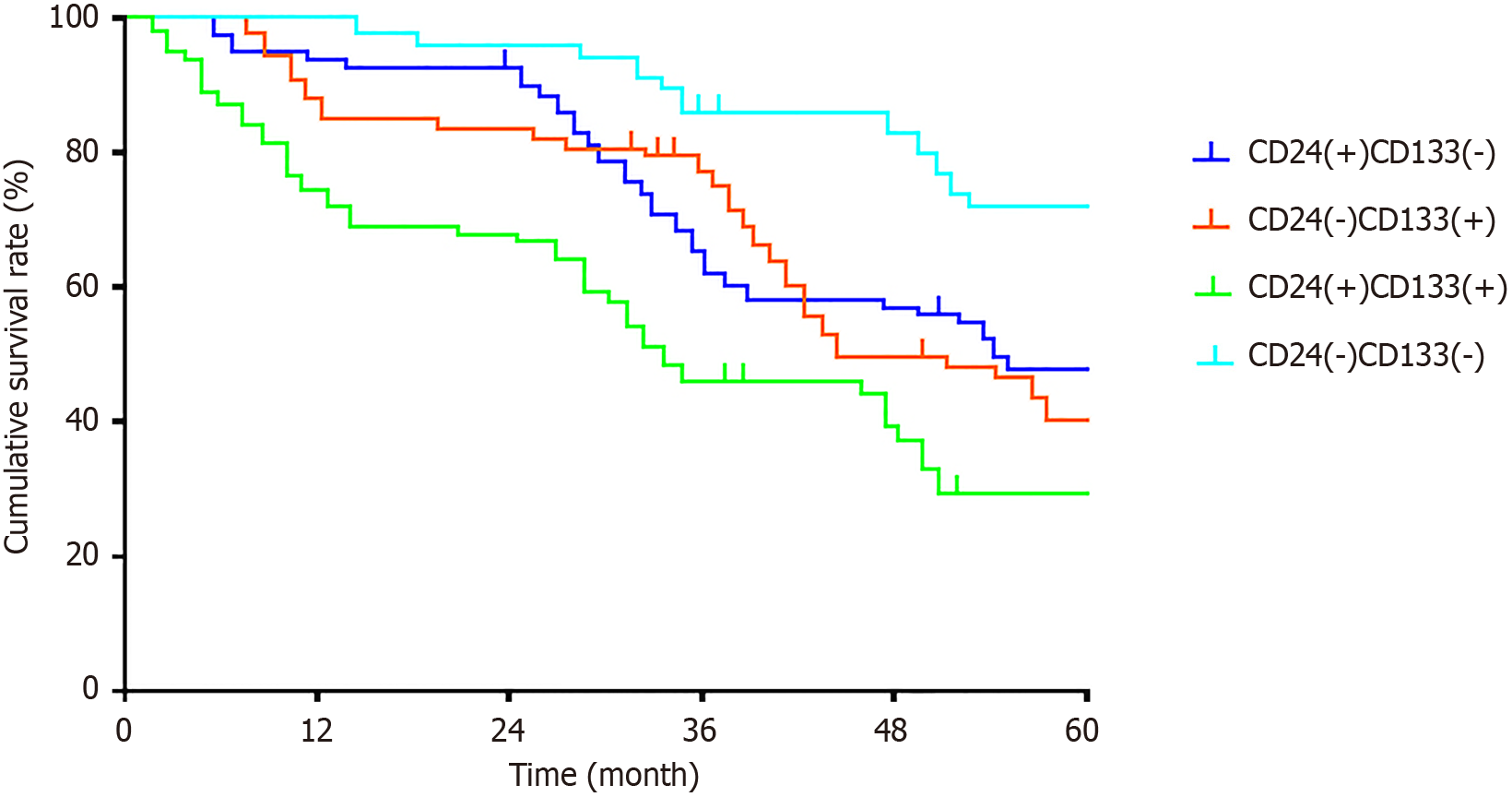

During follow-up, 29 of 304 patients were lost to follow-up (loss rate 9.54%); a total of 146 deaths occurred during the follow-up period. Grouped by expression patterns: CD24 single-positive group, 89 cases (39 deaths); CD133 single-positive group, 68 cases (31 deaths); double-negative group, 81 cases (25 deaths); double-positive group, 66 cases (51 deaths). Log-rank test showed significant differences in OS among the four groups (χ2 = 20.89, P < 0.001), as shown in Figure 2.

The significance of GC stem cell research lies in offering a novel perspective to re-understand the origin and essence of GC. Stem cells possess self-renewal and multidirectional differentiation potential. Although they exist in very small numbers within cancer tissues, they play crucial roles in the initiation, progression, recurrence, and metastasis of malignant tumors[18,19]. At present, research on GC stem cells remains exploratory. Identifying specific GC stem cell markers, isolating and purifying these cells, and understanding their impact on the biological behavior of GC form the foundation for all cell therapy-related studies.

In this retrospective analysis of 304 surgically resected GC patients, we found that the cancer stem cell markers CD24 and CD133 were highly detected in GC tissues (50.99% and 43.75%, respectively), with a certain degree of co-expression (double-positive, 24.34%). Statistical analysis showed that CD24/CD133 co-expression was closely associated with increased tumor diameter, Lauren diffuse type, advanced T stage, severe lymph node metastasis (N stage), and vascular invasion. In multivariate logistic regression, tumor diameter, T stage, N stage, and vascular invasion were identified as independent risk factors for double positivity of the two markers. Survival analysis revealed that patients in the CD24+/CD133+ group had significantly worse OS, suggesting that dual positivity may represent a more aggressive biological subtype of GC with poorer prognosis. These findings hold important clinical and biological significance.

Individually, the relationships between CD24 or CD133 expression and clinicopathological parameters or prognosis in GC have been reported in multiple studies, and our results are largely consistent with these. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicated that CD24 expression is associated with adverse pathological features of GC (such as vascular/Lymphatic invasion, lymph node metastasis) and worse OS, supporting CD24 as an unfavorable prognostic biomarker[20]. Similarly, multiple systematic reviews/meta-analyses have demonstrated that CD133 positivity is correlated with poor prognosis, advanced stage, and increased risk of metastasis, reinforcing its role as a cancer stem cell-related prognostic marker[21,22]. Compared with studies focusing on single markers, our study further emphasized the association of combined CD24/CD133 expression with tumor invasiveness, metastatic potential, and poor prognosis: In this cohort, the double-positive group exhibited larger tumor size, deeper invasion, more extensive lymph node me

From a molecular and cellular biology perspective, CD24 and CD133 participate in multiple tumor progression-related pathways, which may explain their correlation with poorer clinical outcomes. Previous studies have shown that CD24 promotes tumor cell adhesion, migration, and metastasis, and is involved in immune regulation and chemoresistance[24]. Under tumor microenvironmental stressors such as hypoxia, CD24 expression can be upregulated, thereby enhancing invasive phenotypes[25]. CD133 is commonly regarded as a marker of subpopulations with self-renewal and tumorigenic potential, linked to stemness maintenance, signaling pathways (e.g., Wnt, Notch, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B), and drug resistance, with high expression often indicating higher recurrence rates and poor survival[26-28]. When both CD24 and CD133 are co-expressed, they may synergistically identify or sustain a more “stemness-enriched/invasive” subpopulation: CD133 confers self-renewal capacity that underlies recurrence and resistance[29], while CD24-mediated adhesion, migration, and immune evasion mechanisms may enhance distant colonization and growth[30,31]. This combined effect could account for larger tumor volume, deeper invasion, and higher rates of lymph node metastasis, ultimately resulting in worse survival outcomes. In our study, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis (r = 0.420, P < 0.001) revealed a moderate positive correlation between the expression intensities of CD24 and CD133, supporting the notion that they may be co-regulated or co-enriched in specific GC subtypes.

From a clinical perspective, the combined detection of CD24 and CD133 may serve as a valuable reference for pos

The strengths of this study include a relatively large sample size, simultaneous analysis of tumor, adjacent, and normal gastric tissues, and integration of detailed clinicopathological parameters with long-term survival data, offering a comprehensive perspective on the clinical significance of CD24 and CD133. Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this was a single-center retrospective study, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, immunohistochemistry is subject to variability in antibody specificity and scoring methods, which could affect reproducibility across studies. Third, the absence of stratified analysis for postoperative treatment regimens and lack of experimental validation constrain interpretation of causality. Future research should include multicenter, prospective cohorts to confirm these findings and promote standardization of immunohistochemistry protocols. Furthermore, mechanistic investigations into CD24/CD133-related signaling pathways may not only elucidate their roles in GC progression but also reveal novel therapeutic targets for this high-risk patient population.

This study demonstrated that CD24 and CD133 are significantly expressed in GC tissues and frequently co-expressed. Their combined positivity was associated with larger tumor size, advanced stage, vascular invasion, and poorer survival outcomes. These findings support the use of combined assessment of cancer stem cell markers as an important complement to molecular pathological evaluation of GC, suggesting that the CD24/CD133-positive subpopulation may represent a key biological basis for tumor aggressiveness and unfavorable prognosis. Given the retrospective and single-center limitations of this study, larger multicenter prospective studies and mechanistic investigations are required to confirm their clinical value in risk stratification and individualized treatment of GC.

| 1. | Zhang X, Yang L, Liu S, Cao LL, Wang N, Li HC, Ji JF. [Interpretation on the report of global cancer statistics 2022]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2024;46:710-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yu WY, Li X, Zhu J, Ding YM, Tao HQ, Du LB. [Epidemiological characteristics of gastric cancer in China and worldwide]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2025;47:468-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shao XX, Li WK, Hu HT, Lu YM, Tian YT. [Analysis of prognostic risk factors for patients with locally advanced gastric cancer in the stage ypT0~2N0M0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2024;46:1187-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li W, Zhao SL, Zheng P, Shi PQ, Zhou Y, Zhang T, Huo J, Yang J. [Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stem cells regulate the M2 polarization of macrophages within gastric cancer microenvironment via JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2022;44:728-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen Y, Tang J, Li L, Lu T. Effect of Linc-POU3F3 on radiotherapy resistance and cancer stem cell markers of esophageal cancer cells. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2021;46:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kalantari E, Taheri T, Fata S, Abolhasani M, Mehrazma M, Madjd Z, Asgari M. Significant co-expression of putative cancer stem cell markers, EpCAM and CD166, correlates with tumor stage and invasive behavior in colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chang JY, Kim JH, Kang J, Park Y, Park SJ, Cheon JH, Kim WH, Kim H, Park JJ, Kim TI. mTOR Signaling Combined with Cancer Stem Cell Markers as a Survival Predictor in Stage II Colorectal Cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2020;61:572-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dwivedi S, Pareek P, Vishnoi JR, Sharma P, Misra S. Downregulation of miRNA-21 and cancer stem cells after chemotherapy results in better outcome in breast cancer patients. World J Stem Cells. 2022;14:310-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Xuan SH, Hua ML, Xiang Z, He XL, Huang L, Jiang C, Dong P, Wu J. Roles of cancer stem cells in gastrointestinal cancers. World J Stem Cells. 2023;15:209-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li B, Zhou CX, Pu YQ, Qiu L, Mei W, Xiong W. [Expression of CD24 gene in human malignant pleural mesothelioma and its relationship with prognosis]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2023;41:168-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nandagopal S, Choudhary G, Sankanagoudar S, Banerjee M, Elhence P, Jena R, Selvi MK, Shukla KK. Expression of stem cell markers as predictors of therapeutic response in metastatic prostate cancer patients. Urol Oncol. 2024;42:68.e21-68.e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bai YD, Shi ML, Li SQ, Wang XL, Peng JJ, Zhou DJ, Sun FF, Li H, Wang C, Du M, Zhang T, Li D. [The expression and function of PD-L1 in CD133(+) human liver cancer stem-like cells]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2023;45:117-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu Y, Sun Y. [TIPE2 inhibits the stemness of lung cancer cells by regulating the phenotypic polarization of tumor-associated macrophages]. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2025;41:680-686. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Yang W, Ou Y, Luo H, You L, Du H. Causal relationship between circulating immune cells and gastric cancer: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis using UK Biobank and FinnGen datasets. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13:4702-4713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lu R, Zhao G, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Cai J, Hu H. Inhibition of CD133 Overcomes Cisplatin Resistance Through Inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway and Autophagy in CD133-Positive Gastric Cancer Cells. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2019;18:1533033819864311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Czogalla B, Partenheimer A, Badmann S, Schmoeckel E, Mayr D, Kolben T, Beyer S, Hester A, Burges A, Mahner S, Jeschke U, Trillsch F. Nuclear Enolase-1/ MBP-1 expression and its association with the Wnt signaling in epithelial ovarian cancer. Transl Oncol. 2021;14:100910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sun L. [Development trend of assessment system in gastric cancer based on evolution of staging criteria]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;21:1113-1120. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wang L, Fu B, Zhao DF, Yang G, Xu WH. [Relevance of renal cell carcinoma angiogenesis and tumor stem cells]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2021;101:3804-3808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kostova I. Survey of Recent Trends of IB-IVB Metals and Their Compounds in Cancer Treatment. Innov Discov. 2024;1:14. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Wu JX, Zhao YY, Wu X, An HX. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of CD24 overexpression in patients with gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wen L, Chen XZ, Yang K, Chen ZX, Zhang B, Chen JP, Zhou ZG, Mo XM, Hu JK. Prognostic value of cancer stem cell marker CD133 expression in gastric cancer: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Razmi M, Ghods R, Vafaei S, Sahlolbei M, Saeednejad Zanjani L, Madjd Z. Clinical and prognostic significances of cancer stem cell markers in gastric cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang T, Xu J, Deng S, Zhou F, Li J, Zhang L, Li L, Wang QE, Li F. Core signaling pathways in ovarian cancer stem cell revealed by integrative analysis of multi-marker genomics data. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0196351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bai J, Chen WB, Zhang XY, Kang XN, Jin LJ, Zhang H, Wang ZY. HIF-2α regulates CD44 to promote cancer stem cell activation in triple-negative breast cancer via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12:87-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tiburcio PDB, Locke MC, Bhaskara S, Chandrasekharan MB, Huang LE. The neural stem-cell marker CD24 is specifically upregulated in IDH-mutant glioma. Transl Oncol. 2020;13:100819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jagust P, Alcalá S, Sainz Jr B, Heeschen C, Sancho P. Glutathione metabolism is essential for self-renewal and chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12:1410-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang YY, Shen MM, Gao J. Metadherin promotes stem cell phenotypes and correlated with immune infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:901-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zheng SM, Chen H, Sha WH, Chen XF, Yin JB, Zhu XB, Zheng ZW, Ma J. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein stimulates CD206 positive macrophages upregulating CD44 and CD133 expression in colorectal cancer with high-fat diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:4993-5006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 29. | Mehdipour P, Javan F, Jouibari MF, Khaleghi M, Mehrazin M. Evolutionary model of brain tumor circulating cells: Cellular galaxy. World J Clin Oncol. 2021;12:13-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chen J, Liu S, Su Y, Zhang X. ALDH1+ stem cells demonstrate more stem cell-like characteristics than CD44(+)/CD24(-/low) stem cells in different molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9:1652-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Becerril-Rico J, Grandvallet-Contreras J, Ruíz-León MP, Dorantes-Cano S, Ramírez-Vidal L, Tinajero-Rodríguez JM, Ortiz-Sánchez E. Circulating Gastric Cancer Stem Cells as Blood Screening and Prognosis Factor in Gastric Cancer. Stem Cells Int. 2024;2024:9999155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/