Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v17.i12.112990

Revised: September 27, 2025

Accepted: November 6, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 135 Days and 18 Hours

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related death in women world

Core Tip: This review emphasizes the dual functions of breast cancer stem cells and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the advancement of tumors, resistance to treatment, and metastasis. We examine their common molecular characteristics, including self-renewal and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, as well as their interaction with the tumor microenvironment. The paper also covers the current technologies for detecting CTCs and their clinical applications. Gaining an understanding of the dynamic relationship between breast cancer stem cells and CTCs provides valuable insights into the early detection of metastasis and may inform the development of personalized treatment strategies for breast cancer patients.

- Citation: Azizi Z, Er Urganci B, Acikbas I. Breast cancer stem cells and circulating tumor cells: Dual drivers of progression and relapse. World J Stem Cells 2025; 17(12): 112990

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v17/i12/112990.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v17.i12.112990

Breast cancer accounts for 23.8% of all female cancers and 15.4% of all cancer-related deaths in women. According to World Health Organization data, approximately 2.3 million new breast cancer cases were diagnosed globally in 2022 with an estimated 666000 associated deaths. Breast cancer is a global disease. Its incidence, mortality, and survival rates vary significantly in different parts of the world, depending on factors including demographics, lifestyle, genetic factors, and environmental influences[1,2]. Family history is one of the most important risk factors for breast cancer. Approximately 10%-30% of breast cancer cases are familial, but only 5%-10% of cases are hereditary. Women with a history of breast cancer in their first-degree relatives have twice the risk of breast cancer compared with women without such a history

Breast cancer is histologically classified into two types: In situ and invasive. The molecular classification is: (1) Estrogen and progesterone hormone receptor positivity (characterized by the highest prevalence and heterogeneity); (2) Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positivity (HER2+) (subgroup with distinct targeted therapy options, with rising incidence); and (3) Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (a group with only chemotherapy options and an increasing number of patients). Molecular subtypes are divided into five groups: Luminal A, luminal B, HER2, basal-like, and normal-like. Of these, luminal A is the most common subtype with the best prognosis, whereas basal-like is the least common and associated with the worst outcomes[5,6].

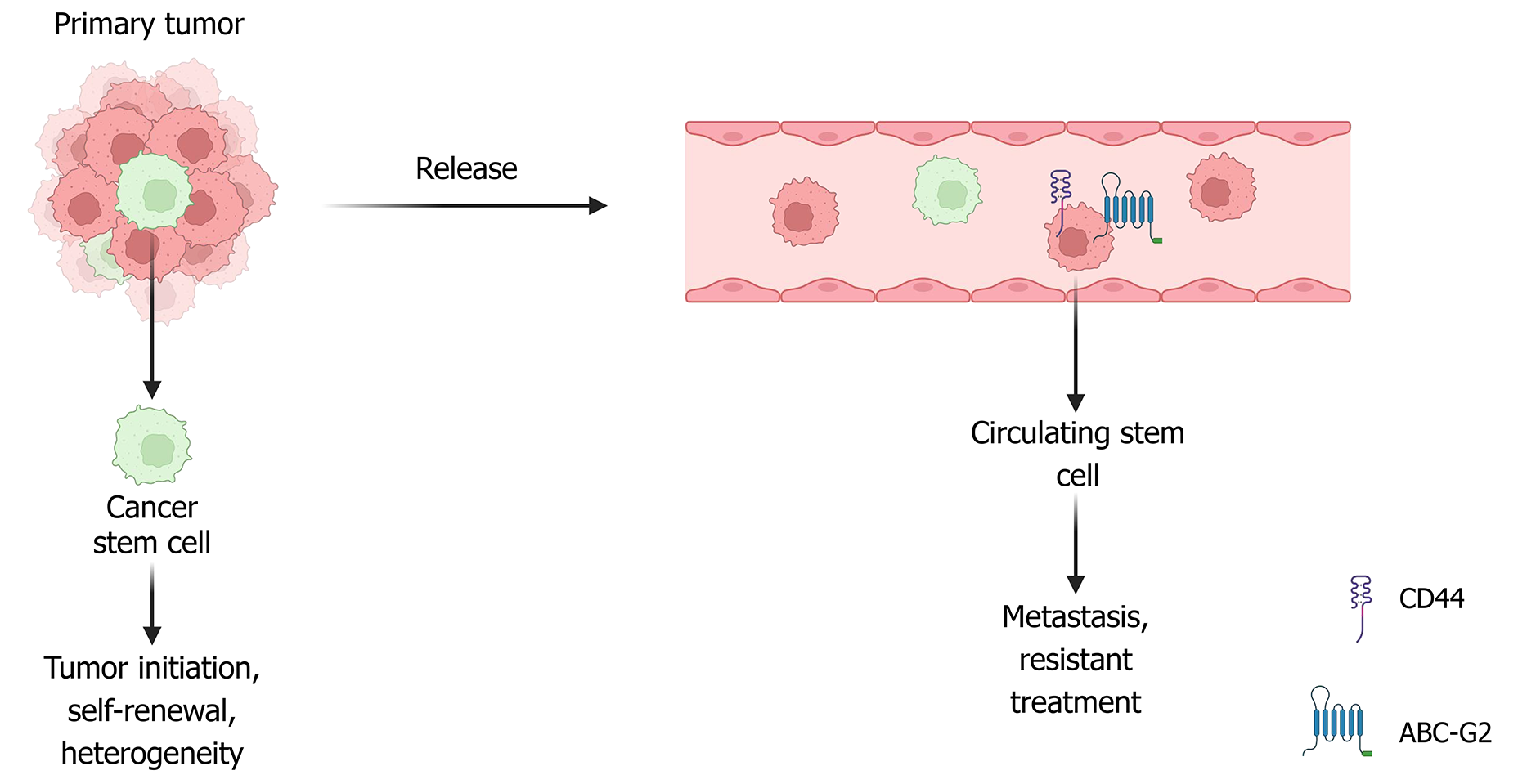

Breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) are key contributors to tumor formation, progression, metastasis, resistance to the

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) represent a distinct subset of cancer cells that detach from the primary tumor and enter the circulation, a crucial step in the development of distant metastases. Tumor invasion into blood vessels at the primary site is believed to lead to the spread of tumor cells and the formation of metastatic lesions in remote organs. This suggests that CTCs may share stem-like characteristics with CSCs, as CSCs have the potential to initiate new tumors. Given their involvement in metastasis, CTCs can be considered precursors of relapse and key mediators of metastatic progression.

In 1937, CSCs were first identified in human acute myeloid leukemia. In 2003, the first CSCs in solid tumors were identified in breast cancer. Subsequently, CSCs were isolated and identified in various tumors, including those of the brain, melanoma, prostate, ovary, colon, pancreas, and several additional solid tumor types. CSCs are characterized by three main functional traits: The ability to initiate and form tumors, long-term self-renewal, and the capacity for differentiation[10]. Self-renewal can occur through symmetric or asymmetric cell division. Symmetric self-renewal results in two daughter stem cells, whereas asymmetric self-renewal produces one daughter stem cell and one non-stem differentiated cell. The serial tumor transplantation assay, which can demonstrate both self-renewal and differentiation potential, is considered the gold standard for determining whether a specific cell population includes CSCs[8]. CSCs are thought to arise from different cellular origins, including normal adult stem cells, progenitor cells, and even reprogrammed differentiated cells. According to Rycaj and Tang[11], normal stem cells represent the most plausible source of CSCs because their extended lifespan allows the accumulation of oncogenic mutations, thereby increasing their susceptibility to malignant transformation. In line with this, Nimmakayala et al[12] emphasized that CSCs may also emerge from progenitor and differentiated cells through genetic and epigenetic alterations, with tumor cell plasticity and microenvironmental interactions further facilitating this process. Similarly, Nalla et al[13] highlighted that although multiple cell types may contribute to CSC formation, normal stem cells remain the predominant source, largely due to their longevity and capacity to tolerate mutational stress, eventually acquiring tumor-initiating capacity.

Progenitor and other differentiated cells are also believed to give rise to CSCs through mutations, particularly through alterations in self-renewal pathways. However, these cells must survive for a relatively short duration and accumulate more mutations than stem cells. Al-Hajj et al[14] were the first to isolate a distinct subset of breast cancer cells from human tumors characterized by the expression profile CD44+, CD24-/Low, and epithelial-specific antigen positivity, which they identified as BCSCs. This cell population was shown to initiate tumor formation in immunodeficient mice, supporting its stem-like and tumorigenic nature. The most widely accepted markers of BCSCs are CD44+, CD24-/Low, and ALDH1+[15,16]. However, additional markers or different expression combinations of these markers have been described to identify BCSC populations, including transcription factors commonly associated with normal stem cell functions (e.g., Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog) and cell surface markers including transcription factors [e.g., integrin subunit α6, CD29, CD61, epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)] and additional surface markers (e.g., cadherin-3, HER2, prominin-1, and C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1)[17]. While CD44+/CD24-/Low and ALDH1+ remain the most accepted BCSC markers, their heterogeneous expression across tumors limits the precision of BCSC definition. Future research should focus on dynamic, multi-omic signatures that capture cellular plasticity and microenvironmental influence, providing more reliable tools for predicting therapy resistance and guiding personalized treatment.

Recent research indicates that BCSCs demonstrate heightened resistance to conventional therapies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormonal therapy. This resistance is thought to significantly contribute to metastasis and cancer recurrence. Unlike traditional treatments that primarily target the bulk of tumor cells, BCSCs possess distinct “stem-like” characteristics that enable them to circumvent the cytotoxic effects of therapeutic agents. A contributing factor to this resistance is the elevated expression of ABC transporters and BCL-2 family proteins, both implicated in multidrug resistance[18]. Additionally, signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Hedgehog have been recognized for their roles in supporting this resistance mechanism[19,20]. Moreover, markers such as CD44 and the immune checkpoint programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) have been associated with poor therapeutic outcomes in breast cancer, likely because of their involvement in resistance-related pathways[21].

RAC1B appears to facilitate the survival of BCSCs and plays a crucial role in their resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, particularly to doxorubicin. Its activity supports BCSC survival and enhances chemoresistance, notably against doxorubicin[22]. Cytokines in the TME significantly contribute to drug resistance by influencing BCSC survival and self-renewal through specific signaling pathways. These molecules not only support tumor cell behavior but also modify the tumor niche to promote chemoresistance[23]. Recent findings have indicated that networks involving bromodomain-containing protein 4, PD-L1, RelB, and interleukin (IL)-6 are intricately associated with breast cancer stemness. Specifically, nuclear PD-L1 and RelB seem to enhance IL-6 expression, whereas bromodomain-containing protein 4 inhibition diminishes BCSC formation and augments immune responses, including CD8+ T cell activity[24].

Several molecular mechanisms have been identified that govern the self-renewal capacity of BCSCs. Hypoxia-induced activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 has been demonstrated to upregulate genes such as PLXNB3, NARF, and TERT, which are instrumental in maintaining BCSC pluripotency[25]. The transcription factor TWIST1, a key regulator of EMT, has been implicated in driving stem-like traits in breast cancer cells, thereby enhancing tumor aggressiveness[26]. In addition, the FAM3 metabolism-regulating signaling molecule C-leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) axis plays a crucial role in promoting BCSC self-renewal while simultaneously restricting tumor burden and metastasis. Streitfeld et al[27] demonstrated that poly(rC) binding protein 1 regulates LIFR via FAM3 metabolism-regulating signaling molecule C, thereby maintaining BCSC self-renewal and invasive potential. Consistently, Woosley et al[28] showed that transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling promotes BCSC stemness through the ILEI/LIFR axis, further highlighting the role of aberrant LIFR activity in enhancing invasiveness, migration, and stem-like properties. Beyond these specific pathways, Mao et al[26] reviewed the central roles of the Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog signaling cascades in maintaining BCSC identity and therapy resistance, emphasizing their potential as therapeutic targets.

The TME exerts a profound influence on the regulation of BCSCs. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells migrate to tumor sites upon IL-6 activation and secrete cytokines that promote CSC proliferation[29], while certain circular RNAs have also been implicated in promoting BCSC growth and self-renewal[30]. Among the signaling cascades, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is particularly critical for maintaining the undifferentiated state of BCSCs and has been strongly linked to tumor initiation. Morrow et al[31] demonstrated that the loss of the tumor suppressor Merlin, aberrantly activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling, thereby supporting CSC-like behavior. In addition, Zhao et al[32] reported that SGCE stabilizes epidermal growth factor receptor, thereby activating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B signaling and promoting drug resistance in BCSCs. Complementing these findings, Junankar et al[33] showed that the transcription factor inhibitor of differentiation 4 regulates mammary stem cells, underscoring its role in maintaining stemness.

Multiple additional regulators sustain breast cancer stemness and carry prognostic significance. Inhibitor of differentiation 4 has been identified as a marker of poor prognosis in TNBC, reflecting its role in sustaining stem-like properties[34]. TGFβ signaling has been shown to enhance BCSC activity through the cyclin D1/Smad pathway, which represses bone morphogenetic protein 4 and upregulates its antagonist Noggin, thereby establishing a self-reinforcing feedback loop[35]. Beyond TGFβ, the Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT3 axis is also essential for stemness: Wang et al[36] reported that inhibition of JAK/STAT3 reduces BCSC self-renewal and downregulates metabolic regulators such as carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1B, underscoring its role in chemoresistance. Consistently, Woosley et al[28] demonstrated that TGFβ may further promote stemness by inducing ILEI via hnRNP E1 and activating JAK/STAT signaling through LIFR. Finally, Ciummo et al[37] showed that the C-X-C motif ligand 1 (CXCL1)-CXCR2 autocrine loop enhances BCSC proliferation and mammosphere formation, effects that can be effectively reversed by blocking CXCL1.

Overall, BCSC resistance arises from both intrinsic signaling and external microenvironmental factors. However, the redundancy and cross-talk among Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog, STAT3, and TGFβ pathways pose a major challenge for effective therapeutic targeting. Future studies should focus on identifying context-dependent vulnerabilities and developing rational combination therapies that simultaneously disrupt multiple resistance circuits while sparing normal stem cells. Integrating single-cell multi-omics with functional in vivo models may further uncover dynamic resistance signatures, providing a path toward more precise and durable treatment strategies.

The TME plays a fundamental role in shaping the behavior of BCSCs, providing structural and biochemical cues that regulate BCSC survival, plasticity, and therapy resistance. Fico and Santamaria-Martínez[38] described the TME as a driving force for BCSC plasticity, emphasizing how stromal signals dynamically reshape stem-like properties. In agreement, Xu et al[39] highlighted that the TME critically influences fate decisions of BCSCs during cancer progression, directing their balance between self-renewal and differentiation. Moreover, Joyce and Fearon[40] underscored the role of the TME in immune privilege and T cell exclusion, illustrating how immunosuppressive niches further support the persistence and therapy resistance of BCSCs.

The TME influences critical stages of tumor progression, including EMT, immune evasion, and metastasis, through various signaling molecules and direct cellular interactions. Importantly, microenvironment-derived signals can either promote or inhibit the acquisition of stem-like characteristics and impact the capacity of cancer cells to initiate and disseminate[38]. Within the TME, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) play a pivotal role in promoting BCSC characteristics by secreting cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β[41], in addition to fibroblast growth factor 5[42]. These factors contribute to the remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and enhance the stemness of BCSCs at the tumor-stroma interface. Furthermore, CAFs can activate signaling pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin, hepatocyte growth factor/Met, and Hedgehog, which establish a feedback loop that sustains a stem-like phenotype[43]. Additionally, leukemia inhibitory factor derived from CAFs facilitates the dedifferentiation of breast cancer cells and upregulates stemness markers such as Nanog, Oct4, and CD44+/CD24-[44].

Additional elements of the TME, such as macrophages, endothelial cells, and ECM molecules, significantly regulate BCSC behavior. Macrophages influence BCSC dynamics through M1/M2 polarization[39], while endothelial cells release Jag1 in response to signals from BCSCs, thereby enhancing pro-stemness loops via the zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox 1/vascular endothelial growth factor A axis[45]. The ECM functions as a niche that integrates intra- and extracellular signals, including collagen and hyaluronic acid, to promote metastatic progression[46]. Furthermore, hypoxic conditions and inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, intensify the dedifferentiation of cancer cells and reinforce their stem-like characteristics through transcriptional regulators such as CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein delta[47].

Recent research has demonstrated that BCSCs actively engage with their microenvironment by secreting factors such as CXCL1, which subsequently promotes their proliferation and influences gene expression[37]. Similarly, progranulin signaling enhances the production of IL-6 and IL-8, thereby increasing the mammosphere-forming capacity of breast cancer cells through sortilin-dependent mechanisms[48]. Additionally, metabolic regulators like uncoupling protein 1, when present in the TME, may suppress BCSC populations by modulating fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase levels and inhibiting snail-mediated repression[49]. Moreover, the co-expression of RON and hepatocyte growth factor-like protein in breast cancer cells promotes BCSC self-renewal via autocrine and paracrine signaling pathways, which also activate macrophages[50]. Overall, the TME functions not only as a supportive structure but also as an active regulator of breast cancer progression via reciprocal interactions with BCSCs[51,52].

While the TME clearly sustains BCSC survival and plasticity, the complexity and redundancy of stromal and immune-derived signals pose major challenges for effective therapeutic targeting. Future research should focus on mapping these dynamic interactions at the single-cell level and developing combination strategies that simultaneously disrupt multiple stromal-stemness feedback loops. Such approaches may ultimately enable precise interventions that disrupt supportive niches while preserving normal tissue homeostasis. The principal cellular and molecular mechanisms are summarized in Table 1. Understanding these mechanisms could provide valuable insights for the development of novel therapies targeting the TME to reduce the risk of recurrence in patients with breast cancer.

| TME component | Mechanism/signal | Effect on BCSCs |

| Cancer-associated fibroblasts | IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, FGF5 secretion[41,42] | ECM remodeling, enhanced stemness at tumor-stroma interface |

| Wnt/β-catenin, HGF/Met, Hedgehog pathways[43] | Sustains stem-like phenotype | |

| Leukemia inhibitory factor[44] | Induces dedifferentiation; ↑ Nanog, Oct4, CD44+/CD24- | |

| Macrophages | M1/M2 polarization[39] | Regulates BCSC dynamics |

| Endothelial cells | Jag1 release, ZEB1/VEGFA axis activation[45] | Enhances stemness via feedback loop |

| ECM | Collagen, hyaluronic acid[46] | Provides niche; supports metastasis |

| Hypoxia and cytokines | IL-6, C/EBPδ pathway[47] | Promotes dedifferentiation, stem-like traits |

| BCSC-secreted factors | CXCL1[37] | Promotes proliferation, alters transcription |

| Progranulin signaling | Induces IL-6/IL-8 via sortilin[48] | Enhances mammosphere formation |

| UCP1 | Regulates FBP1; inhibits snail[49] | Suppresses BCSCs via metabolic modulation |

| RON + HGFL expression | Autocrine/paracrine signaling[50] | Promotes BCSC self-renewal; activates macrophages |

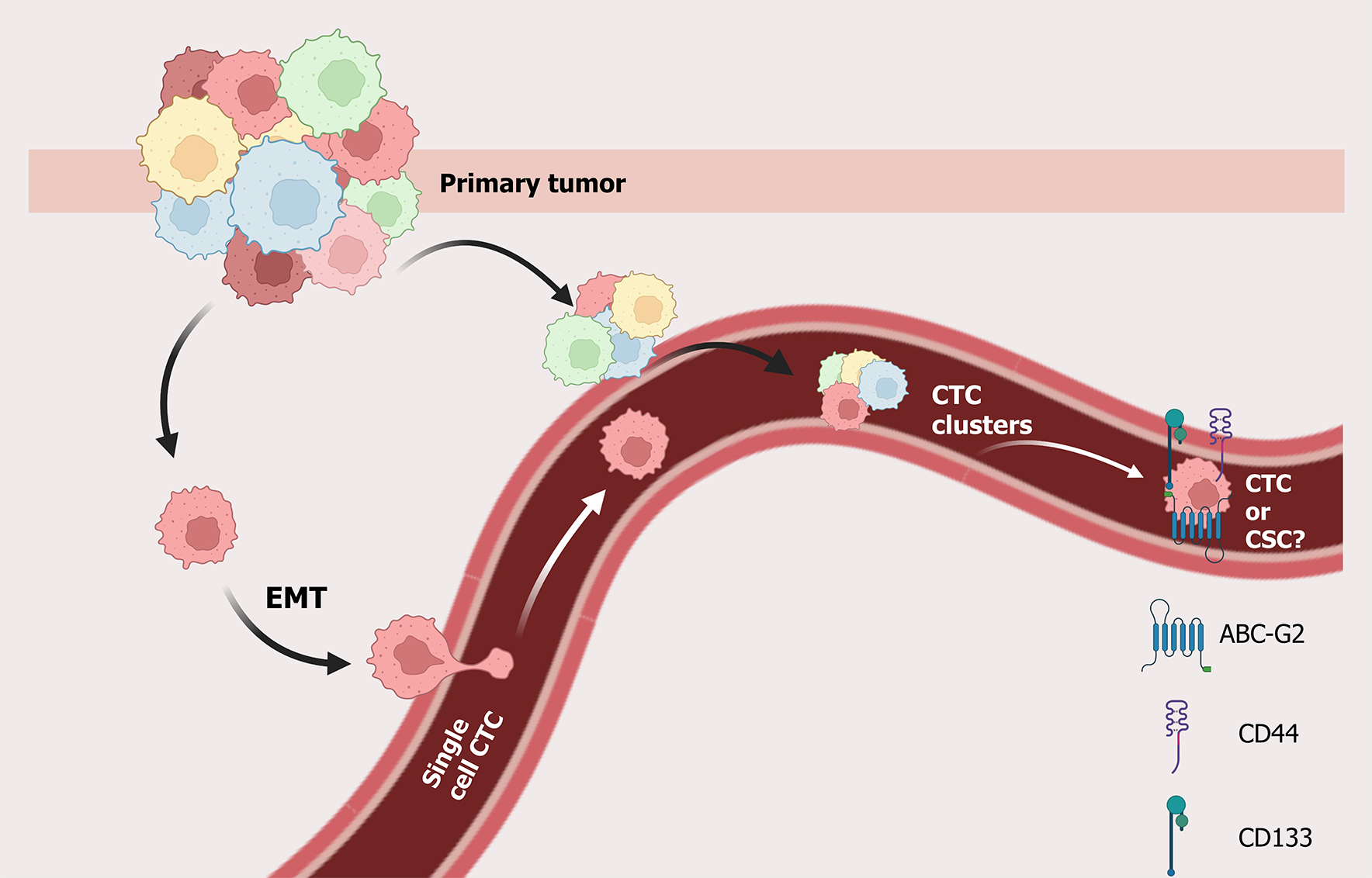

Metastasis and tumor recurrence are the primary causes of cancer-related mortality. CTCs, which are released from primary tumors into the bloodstream, are considered early indicators and key mediators of metastasis[53]. CTC intravasation is a complex process occurring via passive or active mechanisms, depending on tumor characteristics, stage, and microenvironmental conditions. Donato et al[54] demonstrated that hypoxia is a critical driver of clustered CTC intravasation, showing that low-oxygen conditions trigger collective migration of tumor cells into the vasculature. In addition to biochemical cues, mechanical forces also play an important role: Follain et al[55] highlighted how fluid dynamics and mechanical stresses shape the transit of tumor cells through the vasculature, thereby influencing their metastatic efficiency. Complementing these findings, Pan et al[56] reported that CTC-derived organoids provide a powerful model to study intravasation and subsequent metastatic colonization, offering new avenues to investigate how tumor stage and microenvironmental remodeling contribute to dissemination. Although rare, approximately 1 cell per 1-10 million white blood cells is a CTC[57]. CTCs have been detected even in early-stage cancers[58,59], thereby supporting the theory of early dissemination[60].

Recent research indicates that the release of CTCs is not continuous but rather follows temporal rhythms, with a peak occurring nocturnally in circulation[61,62]. Furthermore, CTCs released during the resting phase demonstrate a higher metastatic potential than those released during the active phase[63]. These observations support a functional overlap between CSCs and CTCs. CTCs frequently exhibit stem cell-like characteristics, including the expression of markers such as CD44, CD133, BMI1, and ALDH1[64], and display plasticity during transitions between epithelial-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-epithelial states[65,66].

Despite the substantial number of tumor cells that enter the circulatory system daily, only a minor proportion survive and successfully colonize distant organs[67,68]. Their survival is contingent upon mechanisms of immune evasion, resistance to shear stress in circulation, and the capacity to interact with other circulating or stromal cells, such as platelets, endothelial cells, or CAFs[69,70]. CTCs derive benefit from platelet protection, which shields them from shear-induced damage and immune detection, thereby facilitating their adhesion to the vascular endothelium and subsequent extravasation into secondary sites[71,72]. These cells may travel either as single cells or as multicellular clusters, the latter exhibiting enhanced metastatic efficiency but shorter survival times[73].

In addition to their clinical utility as minimally invasive biomarkers for tumor profiling, prognosis, and real-time monitoring of treatment response[71,74], CTCs also play a role in modulating their microenvironment. For instance, tumor-associated macrophages can induce EMT in colorectal cancer, thereby enhancing CTC generation and increasing metastatic potential[75]. These findings underscore both their biological significance in metastasis and their intricate interactions with the TME, which actively facilitates their survival and dissemination.

Although the biology of CTC release and survival is increasingly well described, the temporal dynamics of in

The accurate detection and characterization of CTCs have become crucial in the management of solid tumors, particularly breast cancer, where CTCs have demonstrated significant prognostic importance[76]. Their inclusion in the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system for breast cancer underscores their clinical relevance[77]. Compared with traditional tissue biopsies, blood-based detection of CTCs offers several advantages: It is minimally invasive, easily repeatable, and facilitates real-time monitoring of treatment response[78,79]. Over the years, various technologies have been developed to isolate and detect CTCs, typically based on either cell surface markers or physical properties, such as size and deformability[80,81].

The CellSearch® system, recognized as the first and most extensively utilized Food and Drug Administration-cleared method, employs epithelial markers such as EpCAM for CTC enrichment and detection[82]. However, this approach may not identify cells that have undergone EMT, thus potentially missing aggressive CTC subtypes characterized by low EpCAM expression[83,84]. To address these limitations, the Food and Drug Administration has recently approved the Parsortix system, which isolates CTCs based on size and deformability, thereby facilitating the capture of a more diverse array of tumor phenotypes[85].

CTC enrichment strategies are generally categorized into two types: Label-dependent and label-independent. Label-dependent techniques utilize immunoaffinity to target known markers, such as EpCAM, HER2, or mesenchymal markers for positive selection, or CD45 for the negative depletion of non-tumor cells[86,87]. Conversely, label-independent methods exploit biophysical properties, such as size or density, to isolate CTCs. These approaches do not require specific antigen expression[88].

Each technique has inherent limitations. Label-dependent methods may fail to identify subpopulations of CTCs that do not express the targeted markers, whereas label-independent methods frequently encounter specificity challenges due to overlapping physical characteristics of CTCs and normal blood cells[89]. Consequently, recent research has focused on integrating multiple enrichment techniques or developing microfluidic platforms to enhance detection sensitivity and specificity[90,91]. Notably, size-based methods have demonstrated particular efficacy in isolating CTC clusters, aggre

Although CellSearch is widely used, studies highlight its limited efficacy in detecting mesenchymal-like or EMT-transformed CTCs. Emerging methodologies focusing on EMT markers or integrating physical and antigen-based detection show enhanced sensitivity in identifying these aggressive subtypes[94]. Furthermore, the prognostic relevance of CTCs, particularly in breast cancer, has been confirmed by numerous clinical investigations. Elevated CTC counts are consistently correlated with poor overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) outcomes[95]. Combined detection strategies may improve prognostic accuracy and guide personalized treatment decisions[96,97]. Single-cell technologies, such as DEPArray, RareCyte, and microcavity array/gel-based manipulation systems, now facilitate more precise isolation and analysis of rare CTC populations[98,99].

Although detection technologies have advanced substantially, the heterogeneity of CTCs, particularly EMT-like and stem-like subtypes, still limits the sensitivity and clinical utility of current platforms. Future directions should focus on integrated, multimodal approaches that combine antigen-based, physical, and functional profiling with single-cell ana

| Method type | Detection principle | Technologies | Advantages | Limitations |

| Label-dependent | Antigen-based (surface markers) | CellSearch® (EpCAM+). HER2, CD45-based | FDA-approved. High specificity for epithelial CTCs | Misses EMT/mesenchymal CTCs. Marker heterogeneity limits sensitivity |

| Label-independent | Physical properties: Size, density, deformability | Parsortix®. Filtration. Microfluidics | Captures broader CTC spectrum. Detects EMT-like CTCs | Lower specificity. Overlap with normal blood cells |

| Combination methods | Antigen + physical property integration | Microfluidic chips with antibodies | Improved sensitivity and specificity. Better for rare subtypes | More complex and costly |

| CTC cluster detection | Enrichment of tumor cell aggregates | Size-based filters. Inertial focusing | Important for early metastasis. Reflects high aggressiveness | Rare and fragile. Difficult to preserve integrity during handling |

| Single-cell analysis | High-resolution detection of individual CTCs | DEPArray. RareCyte. MCA/gel-based | Enables genomic/proteomic profiling. Detects rare variants | Low throughput. Requires optimization and high cost |

An expanding body of evidence highlights the clinical relevance of CTCs as prognostic biomarkers, particularly in breast cancer. Numerous studies have demonstrated that elevated CTC counts are significantly correlated with poorer OS and PFS in both early-and advanced-stages of the disease[76]. Importantly, the presence of CTCs at the time of primary diagnosis in patients without overt metastases can serve as a predictor of metastatic relapse, as evidenced by multiple trials conducted in the adjuvant setting[100,101]. The detection of CTCs during follow-up (2-5 years post-diagnosis) has also been associated with PFS and OS[102,103].

The prognostic significance is particularly pronounced in patients exhibiting CTC-neutrophil clusters, even when only a single cluster is detected[104]. Meta-analyses have consistently shown that CTC+ correlates with poorer prognoses across various solid tumors, including lung, hepatocellular, and pancreatic cancers[105-107]. Similar trends have been observed in breast cancer, although some inconsistencies remain, likely due to differences in detection methods and disease stage[108]. Notably, subgroup analyses indicated that CTC+ status serves as a more robust prognostic marker in Asian populations, regardless of detection thresholds, treatment type, or sampling time[107,109]. In metastatic breast cancer (mBC), elevated CTC levels have been consistently linked to reduced PFS and OS[110-112], although certain clinical trials have not demonstrated the benefits of routine CTC monitoring[113].

Recent studies underscore the importance of longitudinal CTC tracking, revealing that persistent CTC+ may indicate a poor therapeutic response and warrant early treatment modifications. For example, non-responders (patients remaining CTC+ at follow-up) consistently show worse survival outcomes, regardless of tumor subtype (PREDICT study)[114]. CellSearch® remains the most established method for CTC enumeration, with a threshold of ≥ 5 CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood serving as an independent prognostic marker in mBC[112]. CTC counts have also been associated with molecular subtypes, with lower positivity rates observed in luminal-like HER2 cancers compared to HER2+ and TNBC[115]. The STIC-CTC trial was the first to demonstrate that CTC levels could inform treatment decisions in hormone receptor-positive HER2 mBC patients[116]. Further supporting its clinical relevance, baseline CTC counts predicted survival across all immunohistochemical subtypes, except TNBC, where the association was weak. This suggests that integrating CTC data with tumor biology may facilitate personalized treatment approaches. As CTC profiling technologies advance, subtype-specific targeting strategies may emerge[117].

Beyond the enumeration of individual CTCs, quantification of CTC clusters has gained interest because of their strong association with poor clinical outcomes. These clusters are more resistant to shear stress and immune attacks than solitary cells and demonstrate higher metastatic potential. The presence of persistent or large clusters has been linked to significantly poorer prognoses, indicating that longitudinal monitoring may improve prognostic accuracy[118]. Despite ongoing debates, current evidence strongly supports the use of CTCs, particularly the dynamics and clustering of CTCs, as reliable prognostic indicators in breast cancer. The integration of these markers into routine clinical practice, facilitated by advancements in enrichment and detection methodologies, may refine patient stratification and guide personalized treatment strategies.

Although CTC enumeration and clustering have proven to be strong prognostic indicators, variability across detection platforms and patient subgroups continues to limit their standardization in clinical practice. Future work should integrate longitudinal CTC dynamics with molecular profiling to distinguish transient shedding from biologically aggressive populations. Such combined approaches could refine prognostic accuracy and enable real-time, subtype-specific treat

CTCs, as key players in metastatic dissemination, are thought to arise from tumor invasion into blood vessels and share hallmarks with CSCs, such as self-renewal, therapy resistance, and tumor-initiating capacity. These overlapping traits support the concept that some CTCs may act as functional equivalents or progenitors of CSCs, contributing directly to recurrence and poor prognosis[119].

Recent studies suggest that a subset of CTCs displays mesenchymal and CSC-like characteristics with high inter- and intra-patient heterogeneity. Factors such as metastatic site differences, cell cycle states, EMT, and specific gene mutations contribute to this diversity, highlighting the need for personalized profiling of CTCs[120]. Particularly in TNBC, it was shown that CD44+ CSCs can aggregate and form CTC clusters, driving polyclonal metastasis and correlating with poor survival[121]. Moreover, Delta-like 4 loss-of-function in endothelial cells disrupts CSC/CTC dynamics and EMT, suggesting a vascular influence in the early steps of metastasis[122]. The dual identity of CTCs, expressing both epithelial and mesenchymal markers, highlights their phenotypic plasticity. Through this transition, CTCs can acquire CSC traits, including dormancy, asymmetric division, and therapy resistance, especially after irradiation or chemotherapy[123,124].

Multiple markers, including CD44, CD133, EpCAM, and ATP-binding cassette-G2, are shared between CTCs and CSCs. Based on these traits, some researchers have defined this population as circulating tumor stem cells[125,126]. These cells form spheroids and tumor spheres in vitro, reinforcing their stem-like nature[127,128]. Key markers for CTCs and BCSCs include CD44 and ALDH1, while central signaling pathways involve EMT and Wnt/β-catenin. High heterogeneity is a core challenge, as CTC and BCSC phenotypes are dynamic and depend on cancer type, disease stage, and treatment, leading to conflicting findings about single markers and necessitating multi-marker panels and characterization of diverse subpopulations for accurate clinical application[129-131].

Importantly, the detection of CTCs with EMT or CSC phenotypes in patients with metastasis is strongly associated with chemotherapy resistance and poor prognosis. One study found CSC/EMT-type CTCs in 74% of non-responders, vs only 10% of responders. While promising for identifying chemoresistant micrometastatic disease in the neoadjuvant setting, their predictive power remains limited due to sample heterogeneity and requires larger cohort validation[132].

Recent efforts have focused on culturing viable CTCs with CSC-like features from patient blood, which could enable drug testing and real-time monitoring of therapeutic response[133]. However, the plasticity and rarity of these cells challenge the identification of stable and specific biomarkers[134]. Whether CTCs originate from BCSCs or independently from primary tumor cells remains under investigation, with BCSCs having stem-cell-like properties and possibly contributing to the formation of CTCs that can initiate metastasis, while their relationship to normal stem cells is understood as a shared regulatory network. The evolutionary significance of CTC release into the bloodstream lies in their role as critical mediators of metastasis, allowing tumors to spread to distant organs, survive the hostile blood environment, and form new tumors[135-137].

For CTCs, the precise hierarchy and origin of these populations remain unresolved. Future studies should prioritize longitudinal, patient-derived models to trace lineage relationships and dissect how microenvironmental and treatment pressures drive phenotypic plasticity. Such insights may enable the development of integrated biomarker panels and targeted therapies that account for both stemness and dissemination capacity. Together, these findings highlight the biological and clinical importance of CSC-like CTCs (Figure 1). A deeper understanding of their behavior could open new avenues for early metastasis detection, resistance prediction, and personalized therapy design.

BCSCs and CTCs represent two pivotal subpopulations that sustain tumor progression, therapeutic resistance, and recurrence. Their overlapping yet distinct biology underscores them as clinically actionable targets with significant translational potential. Growing evidence highlights the contribution of BCSCs to tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis. Chiotaki et al[138] demonstrated that BCSCs exhibit stemness properties regulated by Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog signaling, rendering these pathways attractive therapeutic targets. Similarly, Li et al[139] reviewed pharmacological approaches that suppress self-renewal signaling to reduce BCSC survival and enhance sensitivity to standard treatments. Zhao et al[140] further emphasized the interplay between intrinsic stemness signaling and the TME, suggesting that disrupting niche support is essential for durable control of BCSCs.

In clinical settings, pathway-targeted therapies are being actively explored. Basho et al[141] provided early clinical evidence that targeting the PI3K/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin axis in mesenchymal/TNBC subtypes yields therapeutic benefit when combined with chemotherapy. More recently, Kahounová et al[137] demon

On the CTC side, progress has expanded their utility from prognostic markers to functional therapeutic targets and dynamic treatment monitors. The STIC-CTC trial provided proof-of-concept that CTC count-based therapy allocation (endocrine vs chemotherapy) is non-inferior to physician’s choice in HR+/HER2- mBC, highlighting the feasibility of CTC-guided therapy[116]. Niu et al[143] further reported that molecular profiling of CTCs identifies targetable markers such as HER2 and epidermal growth factor receptor, enabling stratification for targeted treatments. Complementary to these findings, Ming et al[144] showed how nanotechnology and microfluidic devices improve CTC capture and enrichment, thereby facilitating drug testing and translational research. Importantly, CTC clusters have been identified as hyper-metastatic units. Zhou et al[145] revealed that maintaining cluster integrity is essential for efficient metastasis, suggesting that cluster-disrupting strategies could serve as novel interventions. Translational models have also advanced significantly: Pan et al[56] demonstrated the establishment of CTC-derived organoids and xenografts, while Kahounová et al[137] validated the use of CTC-derived in vivo models for anti-metastatic drug screening.

A unifying feature between CTCs and BCSCs is their reliance on EMT, cellular plasticity, and tumor microenvironmental support. Zhao et al[140] stressed that the TME maintains BCSC traits, while Fernández-Santiago et al[146] emphasized that targeting cellular plasticity rather than static markers may yield more durable benefit. Xu et al[39] similarly noted that fate decisions of BCSCs are tightly regulated by environmental cues, suggesting shared vulnerabilities between these two cell types. Wang et al[147] added caution by highlighting the overlap between BCSCs and normal stem cells, underlining the importance of selective targeting strategies.

In summary, converging evidence delineates a dual translational opportunity: (1) Direct elimination of BCSC-driven stemness programs via developmental pathway inhibitors, metabolic modulators, and immunotherapeutic strategies; and (2) Leveraging CTCs both as therapeutic targets (e.g., disrupting clusters, blocking EMT/hypoxia pathways) and as liquid biopsy-based tools for therapy monitoring and patient stratification. Future clinical trials should integrate these strategies into combination regimens with conventional therapies. This approach has the potential to reduce recurrence, mitigate metastasis, and ultimately improve survival outcomes in breast cancer patients.

Despite considerable advances, research on CTCs and BCSCs continues to face several critical challenges. First, both populations display profound heterogeneity and plasticity, shifting phenotypes under therapeutic pressure through EMT/mesenchymal epithelial transition, dormancy, and organotropism. This complicates their detection and underlies resistance. Recent reviews emphasize that single-cell multi-omics combined with patient-derived organoids or xenografts may help capture and functionally validate this plasticity, while therapeutic strategies targeting adaptive states rather than static markers could provide durable benefit[148,149].

Second, the specificity of markers remains a major limitation, since canonical stemness pathways (Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog) and markers such as ALDH1 or CD44+ high/CD24- low are also expressed in normal stem cells, raising risks of off-target toxicity. Niche-targeting approaches, selective network-level inhibition, and careful pharmacodynamic validation have been proposed as strategies to mitigate this issue[140,150,151].

Third, challenges remain in culturing and maintaining viable CTCs/BCSCs ex vivo. While CTC-derived organoids and xenografts now enable pharmacological testing, success rates, timelines, and costs are limiting[144]. Advances in mi

Finally, clinical validation remains incomplete. The STIC-CTC trial provided the first proof that CTC-guided treatment allocation is feasible and non-inferior to physician’s choice in HR+/HER2- mBC[116]. However, broader implementation requires integration into therapeutic algorithms, health-economics evaluation, and adaptive biomarker-enriched trial designs. Moreover, inhibition of a single pathway often fails due to compensatory activation and toxicity. This suggests that network-level combination strategies, for example, pairing developmental pathway inhibition with metabolic or microenvironmental modulation, may be required.

In summary, current challenges include cellular plasticity, marker overlap with normal stem cells, technical standardization, and clinical trial validation. However, advances in multi-omic profiling, organoid and xenograft models, adaptive clinical designs, and combination therapies suggest that many of these barriers can be progressively overcome. However, certain barriers, particularly normal stem cell overlap and long-term safety, may remain difficult to fully resolve.

Cancer remains a major global health burden and one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide. CTCs, released from primary tumors into the bloodstream or lymphatic system, play a central role in metastasis. They have also emerged as promising biomarkers for early detection and disease monitoring. Similarly, BCSCs sustain tumor growth, drive therapeutic resistance, and promote recurrence. Growing evidence highlights a substantial overlap between CTCs and BCSCs in terms of molecular markers, plasticity, and tumor-initiating capacity. This convergence has given rise to the concept of “circulating tumor stem cells”, which underscores their dual role in promoting dissemination and maintaining stemness. Their phenotypic adaptability, however, represents a major challenge for accurate detection, classification, and therapeutic targeting. Overcoming these obstacles will require integrated approaches that combine multimodal detection and functional profiling. In addition, therapeutic strategies must simultaneously target stemness and metastatic potential. Targeting these rare yet aggressive populations may enhance prognostic precision and facilitate the development of more effective, personalized interventions in breast cancer management (Figure 2).

| 1. | Momenimovahed Z, Salehiniya H. Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2019;11:151-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 62.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12361] [Article Influence: 6180.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 3. | Angeli D, Salvi S, Tedaldi G. Genetic Predisposition to Breast and Ovarian Cancers: How Many and Which Genes to Test? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Coignard J, Lush M, Beesley J, O'Mara TA, Dennis J, Tyrer JP, Barnes DR, McGuffog L, Leslie G, Bolla MK, Adank MA, Agata S, Ahearn T, Aittomäki K, Andrulis IL, Anton-Culver H, Arndt V, Arnold N, Aronson KJ, Arun BK, Augustinsson A, Azzollini J, Barrowdale D, Baynes C, Becher H, Bermisheva M, Bernstein L, Białkowska K, Blomqvist C, Bojesen SE, Bonanni B, Borg A, Brauch H, Brenner H, Burwinkel B, Buys SS, Caldés T, Caligo MA, Campa D, Carter BD, Castelao JE, Chang-Claude J, Chanock SJ, Chung WK, Claes KBM, Clarke CL; GEMO Study Collaborators; EMBRACE Collaborators, Collée JM, Conroy DM, Czene K, Daly MB, Devilee P, Diez O, Ding YC, Domchek SM, Dörk T, Dos-Santos-Silva I, Dunning AM, Dwek M, Eccles DM, Eliassen AH, Engel C, Eriksson M, Evans DG, Fasching PA, Flyger H, Fostira F, Friedman E, Fritschi L, Frost D, Gago-Dominguez M, Gapstur SM, Garber J, Garcia-Barberan V, García-Closas M, García-Sáenz JA, Gaudet MM, Gayther SA, Gehrig A, Georgoulias V, Giles GG, Godwin AK, Goldberg MS, Goldgar DE, González-Neira A, Greene MH, Guénel P, Haeberle L, Hahnen E, Haiman CA, Håkansson N, Hall P, Hamann U, Harrington PA, Hart SN, He W, Hogervorst FBL, Hollestelle A, Hopper JL, Horcasitas DJ, Hulick PJ, Hunter DJ, Imyanitov EN; KConFab Investigators; HEBON Investigators; ABCTB Investigators, Jager A, Jakubowska A, James PA, Jensen UB, John EM, Jones ME, Kaaks R, Kapoor PM, Karlan BY, Keeman R, Khusnutdinova E, Kiiski JI, Ko YD, Kosma VM, Kraft P, Kurian AW, Laitman Y, Lambrechts D, Le Marchand L, Lester J, Lesueur F, Lindstrom T, Lopez-Fernández A, Loud JT, Luccarini C, Mannermaa A, Manoukian S, Margolin S, Martens JWM, Mebirouk N, Meindl A, Miller A, Milne RL, Montagna M, Nathanson KL, Neuhausen SL, Nevanlinna H, Nielsen FC, O'Brien KM, Olopade OI, Olson JE, Olsson H, Osorio A, Ottini L, Park-Simon TW, Parsons MT, Pedersen IS, Peshkin B, Peterlongo P, Peto J, Pharoah PDP, Phillips KA, Polley EC, Poppe B, Presneau N, Pujana MA, Punie K, Radice P, Rantala J, Rashid MU, Rennert G, Rennert HS, Robson M, Romero A, Rossing M, Saloustros E, Sandler DP, Santella R, Scheuner MT, Schmidt MK, Schmidt G, Scott C, Sharma P, Soucy P, Southey MC, Spinelli JJ, Steinsnyder Z, Stone J, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Swerdlow A, Tamimi RM, Tapper WJ, Taylor JA, Terry MB, Teulé A, Thull DL, Tischkowitz M, Toland AE, Torres D, Trainer AH, Truong T, Tung N, Vachon CM, Vega A, Vijai J, Wang Q, Wappenschmidt B, Weinberg CR, Weitzel JN, Wendt C, Wolk A, Yadav S, Yang XR, Yannoukakos D, Zheng W, Ziogas A, Zorn KK, Park SK, Thomassen M, Offit K, Schmutzler RK, Couch FJ, Simard J, Chenevix-Trench G, Easton DF, Andrieu N, Antoniou AC. A case-only study to identify genetic modifiers of breast cancer risk for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Feng Y, Spezia M, Huang S, Yuan C, Zeng Z, Zhang L, Ji X, Liu W, Huang B, Luo W, Liu B, Lei Y, Du S, Vuppalapati A, Luu HH, Haydon RC, He TC, Ren G. Breast cancer development and progression: Risk factors, cancer stem cells, signaling pathways, genomics, and molecular pathogenesis. Genes Dis. 2018;5:77-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 796] [Cited by in RCA: 835] [Article Influence: 104.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Orrantia-Borunda E, Anchondo-Nuñez P, Acuña-Aguilar LE, Gómez-Valles FO, Ramírez-Valdespino CA. Subtypes of Breast Cancer. In: Breast Cancer [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2022. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ray SK, Mukherjee S. Breast cancer stem cells as novel biomarkers. Clin Chim Acta. 2024;557:117855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zeng X, Liu C, Yao J, Wan H, Wan G, Li Y, Chen N. Breast cancer stem cells, heterogeneity, targeting therapies and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Res. 2021;163:105320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang L, Chen W, Liu S, Chen C. Targeting Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:552-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nassar D, Blanpain C. Cancer Stem Cells: Basic Concepts and Therapeutic Implications. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016;11:47-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 677] [Cited by in RCA: 622] [Article Influence: 62.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rycaj K, Tang DG. Cell-of-Origin of Cancer versus Cancer Stem Cells: Assays and Interpretations. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4003-4011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nimmakayala RK, Batra SK, Ponnusamy MP. Unraveling the journey of cancer stem cells from origin to metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2019;1871:50-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nalla LV, Kalia K, Khairnar A. Self-renewal signaling pathways in breast cancer stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;107:140-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983-3988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7830] [Cited by in RCA: 7800] [Article Influence: 339.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ricardo S, Vieira AF, Gerhard R, Leitão D, Pinto R, Cameselle-Teijeiro JF, Milanezi F, Schmitt F, Paredes J. Breast cancer stem cell markers CD44, CD24 and ALDH1: expression distribution within intrinsic molecular subtype. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:937-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ko CCH, Chia WK, Selvarajah GT, Cheah YK, Wong YP, Tan GC. The Role of Breast Cancer Stem Cell-Related Biomarkers as Prognostic Factors. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Conde I, Ribeiro AS, Paredes J. Breast Cancer Stem Cell Membrane Biomarkers: Therapy Targeting and Clinical Implications. Cells. 2022;11:934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Saha T, Lukong KE. Breast Cancer Stem-Like Cells in Drug Resistance: A Review of Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome Drug Resistance. Front Oncol. 2022;12:856974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Qiao X, Zhang Y, Sun L, Ma Q, Yang J, Ai L, Xue J, Chen G, Zhang H, Ji C, Gu X, Lei H, Yang Y, Liu C. Association of human breast cancer CD44(-)/CD24(-) cells with delayed distant metastasis. Elife. 2021;10:e65418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Katoh M. Canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling in cancer stem cells and their niches: Cellular heterogeneity, omics reprogramming, targeted therapy and tumor plasticity (Review). Int J Oncol. 2017;51:1357-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Malla R, Jyosthsna K, Rani G, Purnachandra Nagaraju G. CD44/PD-L1-mediated networks in drug resistance and immune evasion of breast cancer stem cells: Promising targets of natural compounds. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;138:112613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen F, Gurler SB, Novo D, Selli C, Alferez DG, Eroglu S, Pavlou K, Zhang J, Sims AH, Humphreys NE, Adamson A, Campbell A, Sansom OJ, Tournier C, Clarke RB, Brennan K, Streuli CH, Ucar A. RAC1B function is essential for breast cancer stem cell maintenance and chemoresistance of breast tumor cells. Oncogene. 2023;42:679-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen W, Qin Y, Liu S. Cytokines, breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) and chemoresistance. Clin Transl Med. 2018;7:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim SL, Choi HS, Lee DS. BRD4/nuclear PD-L1/RelB circuit is involved in the stemness of breast cancer cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21:315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Semenza GL. Mechanisms of Breast Cancer Stem Cell Specification and Self-Renewal Mediated by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2023;12:783-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mao XD, Wei X, Xu T, Li TP, Liu KS. Research progress in breast cancer stem cells: characterization and future perspectives. Am J Cancer Res. 2022;12:3208-3222. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Streitfeld WS, Dalton AC, Howley BV, Howe PH. PCBP1 regulates LIFR through FAM3C to maintain breast cancer stem cell self-renewal and invasiveness. Cancer Biol Ther. 2023;24:2271638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Woosley AN, Dalton AC, Hussey GS, Howley BV, Mohanty BK, Grelet S, Dincman T, Bloos S, Olsen SK, Howe PH. TGFβ promotes breast cancer stem cell self-renewal through an ILEI/LIFR signaling axis. Oncogene. 2019;38:3794-3811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mi F, Gong L. Secretion of interleukin-6 by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promotes metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci Rep. 2017;37:BSR20170181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang L, Yi Y, Mei Z, Huang D, Tang S, Hu L, Liu L. Circular RNAs in cancer stem cells: Insights into their roles and mechanisms (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2025;55:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Morrow KA, Das S, Meng E, Menezes ME, Bailey SK, Metge BJ, Buchsbaum DJ, Samant RS, Shevde LA. Loss of tumor suppressor Merlin results in aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:17991-18005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhao L, Qiu T, Jiang D, Xu H, Zou L, Yang Q, Chen C, Jiao B. SGCE Promotes Breast Cancer Stem Cells by Stabilizing EGFR. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2020;7:1903700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Junankar S, Baker LA, Roden DL, Nair R, Elsworth B, Gallego-Ortega D, Lacaze P, Cazet A, Nikolic I, Teo WS, Yang J, McFarland A, Harvey K, Naylor MJ, Lakhani SR, Simpson PT, Raghavendra A, Saunus J, Madore J, Kaplan W, Ormandy C, Millar EK, O'Toole S, Yun K, Swarbrick A. ID4 controls mammary stem cells and marks breast cancers with a stem cell-like phenotype. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Song Y, Zhang P, Bhushan S, Wu X, Zheng H, Yang Y. The Critical Role of Inhibitor of Differentiation 4 in Breast Cancer: From Mammary Gland Development to Tumor Progression. Cancer Med. 2025;14:e70856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yan G, Dai M, Zhang C, Poulet S, Moamer A, Wang N, Boudreault J, Ali S, Lebrun JJ. TGFβ/cyclin D1/Smad-mediated inhibition of BMP4 promotes breast cancer stem cell self-renewal activity. Oncogenesis. 2021;10:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wang T, Fahrmann JF, Lee H, Li YJ, Tripathi SC, Yue C, Zhang C, Lifshitz V, Song J, Yuan Y, Somlo G, Jandial R, Ann D, Hanash S, Jove R, Yu H. JAK/STAT3-Regulated Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Is Critical for Breast Cancer Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Chemoresistance. Cell Metab. 2018;27:136-150.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 73.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ciummo SL, D'Antonio L, Sorrentino C, Fieni C, Lanuti P, Stassi G, Todaro M, Di Carlo E. The C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1 Sustains Breast Cancer Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Promotes Tumor Progression and Immune Escape Programs. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:689286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Fico F, Santamaria-Martínez A. The Tumor Microenvironment as a Driving Force of Breast Cancer Stem Cell Plasticity. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:3863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Xu H, Zhang F, Gao X, Zhou Q, Zhu L. Fate decisions of breast cancer stem cells in cancer progression. Front Oncol. 2022;12:968306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Joyce JA, Fearon DT. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2015;348:74-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1263] [Cited by in RCA: 1801] [Article Influence: 163.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Su S, Chen J, Yao H, Liu J, Yu S, Lao L, Wang M, Luo M, Xing Y, Chen F, Huang D, Zhao J, Yang L, Liao D, Su F, Li M, Liu Q, Song E. CD10(+)GPR77(+) Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promote Cancer Formation and Chemoresistance by Sustaining Cancer Stemness. Cell. 2018;172:841-856.e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 533] [Cited by in RCA: 939] [Article Influence: 117.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Cazet AS, Hui MN, Elsworth BL, Wu SZ, Roden D, Chan CL, Skhinas JN, Collot R, Yang J, Harvey K, Johan MZ, Cooper C, Nair R, Herrmann D, McFarland A, Deng N, Ruiz-Borrego M, Rojo F, Trigo JM, Bezares S, Caballero R, Lim E, Timpson P, O'Toole S, Watkins DN, Cox TR, Samuel MS, Martín M, Swarbrick A. Targeting stromal remodeling and cancer stem cell plasticity overcomes chemoresistance in triple negative breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Valenti G, Quinn HM, Heynen GJJE, Lan L, Holland JD, Vogel R, Wulf-Goldenberg A, Birchmeier W. Cancer Stem Cells Regulate Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts via Activation of Hedgehog Signaling in Mammary Gland Tumors. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2134-2147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Vaziri N, Shariati L, Zarrabi A, Farazmand A, Haghjooy Javanmard S. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Regulate the Plasticity of Breast Cancer Stemness through the Production of Leukemia Inhibitory Factor. Life (Basel). 2021;11:1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Jiang H, Zhou C, Zhang Z, Wang Q, Wei H, Shi W, Li J, Wang Z, Ou Y, Wang W, Wang H, Zhang Q, Sun W, Sun P, Yang S. Jagged1-Notch1-deployed tumor perivascular niche promotes breast cancer stem cell phenotype through Zeb1. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Elia I, Rossi M, Stegen S, Broekaert D, Doglioni G, van Gorsel M, Boon R, Escalona-Noguero C, Torrekens S, Verfaillie C, Verbeken E, Carmeliet G, Fendt SM. Breast cancer cells rely on environmental pyruvate to shape the metastatic niche. Nature. 2019;568:117-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Balamurugan K, Mendoza-Villanueva D, Sharan S, Summers GH, Dobrolecki LE, Lewis MT, Sterneck E. C/EBPδ links IL-6 and HIF-1 signaling to promote breast cancer stem cell-associated phenotypes. Oncogene. 2019;38:3765-3780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Berger K, Persson E, Gregersson P, Ruiz-Martínez S, Jonasson E, Ståhlberg A, Rhost S, Landberg G. Interleukin-6 Induces Stem Cell Propagation through Liaison with the Sortilin-Progranulin Axis in Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:5757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Zhang F, Liu B, Deng Q, Sheng D, Xu J, He X, Zhang L, Liu S. UCP1 regulates ALDH-positive breast cancer stem cells through releasing the suppression of Snail on FBP1. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2021;37:277-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Hunt BG, Jones A, Lester C, Davis JC, Benight NM, Waltz SE. RON (MST1R) and HGFL (MST1) Co-Overexpression Supports Breast Tumorigenesis through Autocrine and Paracrine Cellular Crosstalk. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:2493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Tekpli X, Lien T, Røssevold AH, Nebdal D, Borgen E, Ohnstad HO, Kyte JA, Vallon-Christersson J, Fongaard M, Due EU, Svartdal LG, Sveli MAT, Garred Ø; OSBREAC, Frigessi A, Sahlberg KK, Sørlie T, Russnes HG, Naume B, Kristensen VN. An independent poor-prognosis subtype of breast cancer defined by a distinct tumor immune microenvironment. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Azizi E, Carr AJ, Plitas G, Cornish AE, Konopacki C, Prabhakaran S, Nainys J, Wu K, Kiseliovas V, Setty M, Choi K, Fromme RM, Dao P, McKenney PT, Wasti RC, Kadaveru K, Mazutis L, Rudensky AY, Pe'er D. Single-Cell Map of Diverse Immune Phenotypes in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Cell. 2018;174:1293-1308.e36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 888] [Cited by in RCA: 1478] [Article Influence: 184.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Ring A, Nguyen-Sträuli BD, Wicki A, Aceto N. Biology, vulnerabilities and clinical applications of circulating tumour cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23:95-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 54. | Donato C, Kunz L, Castro-Giner F, Paasinen-Sohns A, Strittmatter K, Szczerba BM, Scherrer R, Di Maggio N, Heusermann W, Biehlmaier O, Beisel C, Vetter M, Rochlitz C, Weber WP, Banfi A, Schroeder T, Aceto N. Hypoxia Triggers the Intravasation of Clustered Circulating Tumor Cells. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Follain G, Herrmann D, Harlepp S, Hyenne V, Osmani N, Warren SC, Timpson P, Goetz JG. Fluids and their mechanics in tumour transit: shaping metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:107-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Pan C, Wang X, Yang C, Fu K, Wang F, Fu L. The culture and application of circulating tumor cell-derived organoids. Trends Cell Biol. 2025;35:364-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Dive C, Brady G. SnapShot: Circulating Tumor Cells. Cell. 2017;168:742-742.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Lawrence R, Watters M, Davies CR, Pantel K, Lu YJ. Circulating tumour cells for early detection of clinically relevant cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:487-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zhu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Tang D, Zhang S, Wang L, Zou X, Ni Z, Zhang S, Lv Y, Xiang N. High-throughput enrichment of portal venous circulating tumor cells for highly sensitive diagnosis of CA19-9-negative pancreatic cancer patients using inertial microfluidics. Biosens Bioelectron. 2024;259:116411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Hosseini H, Obradović MMS, Hoffmann M, Harper KL, Sosa MS, Werner-Klein M, Nanduri LK, Werno C, Ehrl C, Maneck M, Patwary N, Haunschild G, Gužvić M, Reimelt C, Grauvogl M, Eichner N, Weber F, Hartkopf AD, Taran FA, Brucker SY, Fehm T, Rack B, Buchholz S, Spang R, Meister G, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Klein CA. Early dissemination seeds metastasis in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;540:552-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 537] [Article Influence: 53.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Zhu X, Suo Y, Fu Y, Zhang F, Ding N, Pang K, Xie C, Weng X, Tian M, He H, Wei X. In vivo flow cytometry reveals a circadian rhythm of circulating tumor cells. Light Sci Appl. 2021;10:110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Dauvilliers Y, Thomas F, Alix-Panabières C. Dissemination of circulating tumor cells at night: role of sleep or circadian rhythm? Genome Biol. 2022;23:214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Diamantopoulou Z, Castro-Giner F, Schwab FD, Foerster C, Saini M, Budinjas S, Strittmatter K, Krol I, Seifert B, Heinzelmann-Schwarz V, Kurzeder C, Rochlitz C, Vetter M, Weber WP, Aceto N. The metastatic spread of breast cancer accelerates during sleep. Nature. 2022;607:156-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Savelieva OE, Tashireva LA, Kaigorodova EV, Buzenkova AV, Mukhamedzhanov RK, Grigoryeva ES, Zavyalova MV, Tarabanovskaya NA, Cherdyntseva NV, Perelmuter VM. Heterogeneity of Stemlike Circulating Tumor Cells in Invasive Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Fumagalli A, Oost KC, Kester L, Morgner J, Bornes L, Bruens L, Spaargaren L, Azkanaz M, Schelfhorst T, Beerling E, Heinz MC, Postrach D, Seinstra D, Sieuwerts AM, Martens JWM, van der Elst S, van Baalen M, Bhowmick D, Vrisekoop N, Ellenbroek SIJ, Suijkerbuijk SJE, Snippert HJ, van Rheenen J. Plasticity of Lgr5-Negative Cancer Cells Drives Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:569-578.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Huang Q, Liu L, Xiao D, Huang Z, Wang W, Zhai K, Fang X, Kim J, Liu J, Liang W, He J, Bao S. CD44(+) lung cancer stem cell-derived pericyte-like cells cause brain metastases through GPR124-enhanced trans-endothelial migration. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1621-1636.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Hamza B, Miller AB, Meier L, Stockslager M, Ng SR, King EM, Lin L, DeGouveia KL, Mulugeta N, Calistri NL, Strouf H, Bray C, Rodriguez F, Freed-Pastor WA, Chin CR, Jaramillo GC, Burger ML, Weinberg RA, Shalek AK, Jacks T, Manalis SR. Measuring kinetics and metastatic propensity of CTCs by blood exchange between mice. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Tretyakova MS, Menyailo ME, Schegoleva AA, Bokova UA, Larionova IV, Denisov EV. Technologies for Viable Circulating Tumor Cell Isolation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Liu X, Song J, Zhang H, Liu X, Zuo F, Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Yin X, Guo X, Wu X, Zhang H, Xu J, Hu J, Jing J, Ma X, Shi H. Immune checkpoint HLA-E:CD94-NKG2A mediates evasion of circulating tumor cells from NK cell surveillance. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:272-287.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Sun Y, Li T, Ding L, Wang J, Chen C, Liu T, Liu Y, Li Q, Wang C, Huo R, Wang H, Tian T, Zhang C, Pan B, Zhou J, Fan J, Yang X, Yang W, Wang B, Guo W. Platelet-mediated circulating tumor cell evasion from natural killer cell killing through immune checkpoint CD155-TIGIT. Hepatology. 2025;81:791-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Pereira-Veiga T, Schneegans S, Pantel K, Wikman H. Circulating tumor cell-blood cell crosstalk: Biology and clinical relevance. Cell Rep. 2022;40:111298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ward MP, E Kane L, A Norris L, Mohamed BM, Kelly T, Bates M, Clarke A, Brady N, Martin CM, Brooks RD, Brooks DA, Selemidis S, Hanniffy S, Dixon EP, A O'Toole S, J O'Leary J. Platelets, immune cells and the coagulation cascade; friend or foe of the circulating tumour cell? Mol Cancer. 2021;20:59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 73. | Yang J, Xu P, Zhang G, Wang D, Ye B, Wu L. Advances and potentials in platelet-circulating tumor cell crosstalk. Am J Cancer Res. 2025;15:407-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Bates M, Mohamed BM, Ward MP, Kelly TE, O'Connor R, Malone V, Brooks R, Brooks D, Selemidis S, Martin C, O'Toole S, O'Leary JJ. Circulating tumour cells: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2023;1878:188863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Wei C, Yang C, Wang S, Shi D, Zhang C, Lin X, Liu Q, Dou R, Xiong B. Crosstalk between cancer cells and tumor associated macrophages is required for mesenchymal circulating tumor cell-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 634] [Article Influence: 90.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 76. | Alix-Panabières C, Pantel K. Liquid Biopsy: From Discovery to Clinical Application. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:858-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 130.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Giuliano AE, Connolly JL, Edge SB, Mittendorf EA, Rugo HS, Solin LJ, Weaver DL, Winchester DJ, Hortobagyi GN. Breast Cancer-Major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:290-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 645] [Article Influence: 71.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Cabel L, Proudhon C, Gortais H, Loirat D, Coussy F, Pierga JY, Bidard FC. Circulating tumor cells: clinical validity and utility. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22:421-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Liu J, Lian J, Chen Y, Zhao X, Du C, Xu Y, Hu H, Rao H, Hong X. Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): A Unique Model of Cancer Metastases and Non-invasive Biomarkers of Therapeutic Response. Front Genet. 2021;12:734595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Mohtar MA, Syafruddin SE, Nasir SN, Low TY. Revisiting the Roles of Pro-Metastatic EpCAM in Cancer. Biomolecules. 2020;10:255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Cohen EN, Jayachandran G, Moore RG, Cristofanilli M, Lang JE, Khoury JD, Press MF, Kim KK, Khazan N, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Kaur P, Guzman R, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Ueno NT. A Multi-Center Clinical Study to Harvest and Characterize Circulating Tumor Cells from Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer Using the Parsortix(®) PC1 System. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet M, Connelly MC, Rao C, Tibbe AG, Uhr JW, Terstappen LW. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6897-6904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1810] [Cited by in RCA: 1979] [Article Influence: 94.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Brown TC, Sankpal NV, Gillanders WE. Functional Implications of the Dynamic Regulation of EpCAM during Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Biomolecules. 2021;11:956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Joosse SA, Pantel K. Biologic challenges in the detection of circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:8-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Koch C, Joosse SA, Schneegans S, Wilken OJW, Janning M, Loreth D, Müller V, Prieske K, Banys-Paluchowski M, Horst LJ, Loges S, Peine S, Wikman H, Gorges TM, Pantel K. Pre-Analytical and Analytical Variables of Label-Independent Enrichment and Automated Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells in Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Joosse SA, Gorges TM, Pantel K. Biology, detection, and clinical implications of circulating tumor cells. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Deng Z, Wu S, Wang Y, Shi D. Circulating tumor cell isolation for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. EBioMedicine. 2022;83:104237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Warkiani ME, Khoo BL, Wu L, Tay AK, Bhagat AA, Han J, Lim CT. Ultra-fast, label-free isolation of circulating tumor cells from blood using spiral microfluidics. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:134-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Gabriel MT, Calleja LR, Chalopin A, Ory B, Heymann D. Circulating Tumor Cells: A Review of Non-EpCAM-Based Approaches for Cell Enrichment and Isolation. Clin Chem. 2016;62:571-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Bankó P, Lee SY, Nagygyörgy V, Zrínyi M, Chae CH, Cho DH, Telekes A. Technologies for circulating tumor cell separation from whole blood. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Woo HJ, Kim SH, Kang HJ, Lee SH, Lee SJ, Kim JM, Gurel O, Kim SY, Roh HR, Lee J, Park Y, Shin HY, Shin YI, Lee SM, Oh SY, Kim YZ, Chae JI, Lee S, Hong MH, Cho BC, Lee ES, Pantel K, Kim HR, Kim MS. Continuous centrifugal microfluidics (CCM) isolates heterogeneous circulating tumor cells via full automation. Theranostics. 2022;12:3676-3689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Reduzzi C, Di Cosimo S, Gerratana L, Motta R, Martinetti A, Vingiani A, D'Amico P, Zhang Y, Vismara M, Depretto C, Scaperrotta G, Folli S, Pruneri G, Cristofanilli M, Daidone MG, Cappelletti V. Circulating Tumor Cell Clusters Are Frequently Detected in Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:2356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |