Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v17.i12.112778

Revised: September 16, 2025

Accepted: November 12, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 141 Days and 19.7 Hours

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease traditionally viewed through the lens of cartilage degradation. However, emerging evidence positions subchondral bone pathology - particularly bone marrow lesions (BMLs) - as a key contributor to pain, progression, and structural deterioration. Mesenchymal stem cell exhaustion within the osteoarthritic subchondral zone further impairs intrinsic repair mechanisms, reinforcing the rationale for biologic interventions.

To evaluate the clinical efficacy of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) therapy for knee OA, comparing subchondral vs intra-articular delivery routes, and elucidating the therapeutic impact on symptom relief and structural preservation.

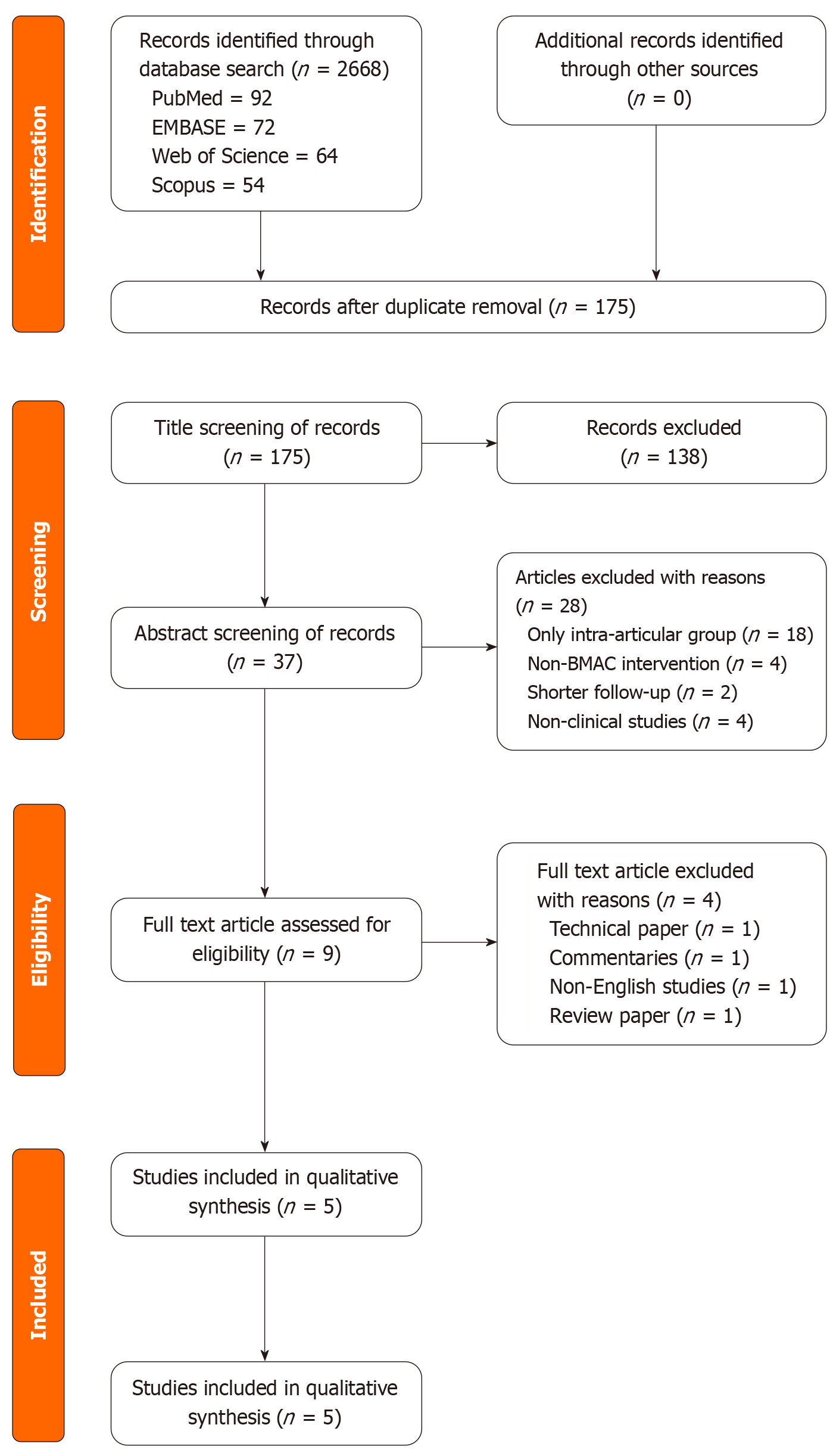

Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, five clinical studies were included - comprising three randomized controlled trials and two prospective cohorts - with pooled data from 298 knees. Data on functional outcomes, imaging findings, and progression to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) were extracted and qualitatively synthesized.

Subchondral BMAC injections demonstrated superior improvements compared to intra-articular injection or placebo: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score improved from 49.1 ± 1.9 to 61.2 ± 6.3 at 12 months (P < 0.05), Knee Society Score increased from 57 ± 12 to 87.3 ± 12 at two years, and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index scores showed significant improvement favoring combined approaches. Magnetic resonance imaging analyses revealed mean BML volume regression of 2.1 cm3, with 80% of knees avoiding TKA over 13-year follow-up. Magnetic resonance imaging analyses revealed regression of BMLs and increased cartilage preservation in subchondral-treated knees. Long-term data indicated delayed progression to TKA and biomechanical improvements (e.g., Hip-Knee-Ankle angle correction). No major adverse events were reported.

Targeting subchondral bone with BMAC addresses underlying OA pathology and may offer disease-modifying potential beyond symptom relief. These findings support a paradigm shift toward whole-joint biologic therapy, positioning the subchondral matrix as a therapeutic epicenter in OA management.

Core Tip: Subchondral bone-targeted bone marrow aspirate concentrate therapy offers a promising biologic approach for knee osteoarthritis, outperforming intra-articular delivery in symptom relief and structural preservation. Addressing bone marrow lesions and mesenchymal stem cell depletion within the subchondral zone enhances pain scores, functional outcomes, and cartilage integrity while delaying total knee arthroplasty. These findings support a paradigm shift toward whole-joint biologic interventions that modify disease progression rather than merely alleviating symptoms.

- Citation: Nallakumarasamy A, Shrivastava S, Rangarajan RV, Jeyaraman N, Devadas AG, Ramasubramanian S, Muthu S, Bapat A, Jeyaraman M. Does standalone/combined subchondral bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cell injection offer significantly better clinical benefit to intraarticular injection in knee osteoarthritis? World J Stem Cells 2025; 17(12): 112778

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v17/i12/112778.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v17.i12.112778

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is a highly prevalent degenerative joint disease and a leading cause of disability wor

Subchondral BMLs and edema have emerged as important biomarkers and drivers of OA progression[5-8]. BMLs are regions of microdamage and repair in subchondral bone that correlate strongly with knee pain and structural deterioration. Longitudinal studies have shown that BML presence and severity predict accelerated loss of adjacent articular cartilage and increased likelihood of joint replacement[9]. In one study, each unit increase in BML grade was associated with a 1.14% per year faster tibial cartilage volume loss and a higher odds of needing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) over 4 years[9]. Notably, BMLs rarely resolve spontaneously, reflecting ongoing subchondral pathology that perpetuates joint degeneration[4]. These lesions are thought to provoke pain via raised subchondral pressure and nociceptive nerve in

Compounding this issue, there is evidence of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell (MSC) dysfunction or depletion in the osteoarthritic subchondral bone. Healthy subchondral bone harbors a reservoir of MSCs that contribute to tissue repair. In primary OA, however, these skeletal progenitors appear numerically and functionally compromised[3]. Histological analysis revealed a reduction in the resident progenitors in the subchondral matrix of cartilage affected by advanced OA compared to normal regions[10]. A comparative analysis of subchondral bone-derived MSCs found that patients with primary OA had “reduced” MSCs with reduced viability and osteogenic potential, unlike those with secondary (dy

Bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) has emerged as a promising orthobiologic therapy for knee OA that could address symptomatic relief and the underlying degenerative processes. BMAC is an autologous concentrate of bone marrow aspirate, containing a heterogeneous mix of MSCs, hematopoietic cells, platelets, growth factors, and cytokines. Delivered via injection, BMAC directly provides a potent cocktail of regenerative and immunomodulatory factors to the joint environment. Early clinical studies have demonstrated that BMAC injections are safe and can yield significant improvements in pain and function for patients with knee OA[4]. In contrast to palliative treatments, BMAC therapy offers the potential to favorably modify the joint microenvironment by promoting tissue repair and inhibiting inflammation. For example, in severe knee OA (Kellgren-Lawrence grade III-IV) cases, a 4-year prospective study reported substantial and sustained benefit after a single intra-articular BMAC injection: Western Ontario and McMaster Uni

Within the expanding domain of biologic injections, a compelling strategy is emerging: Delivering BMAC to the subchondral bone, rather than solely into the intra-articular space. The biological rationale is twofold. First, targeting the subchondral region directly addresses the site of BMLs and sclerosis that drive pain and structural progression. By in

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was performed across four major databases - PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and Web of Science covering publications from January 2000 to June 2025. The search strategy combined keywords and Medical Subject Headings terms related to “BMAC”, “knee osteoarthritis”, “subchondral injection”, “intra-articular injection”, and “mesenchymal stem cells”. Boolean operators and filters were applied to refine results to human clinical studies published in English.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) Involved adult patients diagnosed with knee OA based on clinical and radiographic criteria; (2) Evaluated the therapeutic use of autologous BMAC delivered via intra-articular, subchondral, or combined routes; (3) Reported clinical outcomes such as pain, function, or imaging findings; and (4) Had a minimum follow-up duration of 6 months. Exclusion criteria included animal studies, in vitro experiments, reviews without original data, studies using culture expanded or allogeneic stem cells, and those lacking route-specific outcome data.

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts for relevance, followed by full-text assessment of potentially eligible articles. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer. Data extraction was performed using a standardised template capturing study design, sample size, patient demographics, OA severity (Kellgren-Lawrence grade), injection technique, BMAC preparation method, follow-up duration, and outcome measures. Primary outcomes included pain scores [Visual Analog Scale (VAS)], functional indices [WOMAC, IKDC, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)], and imaging findings (MRI-based assessment of BMLs and cartilage thickness). Secondary outcomes included adverse events and TKA progression.

To address heterogeneity across studies, we developed a systematic approach for handling variability in patient populations and interventions. Studies were stratified by OA severity using Kellgren-Lawrence grades (I-II vs III-IV), with separate analysis planned for early vs advanced disease stages. Age-related differences were addressed by recording the mean patient age and standard deviation for each cohort, with subgroup considerations for patients above and below 65 years. BMAC protocol variations were systematically catalogued, including aspiration volume (range: 60-240 mL), concentration methods (centrifugation vs filtration), final concentrate volume (5-20 mL), and cell counts where reported (colony-forming units per mL). Injection technique differences were documented, including single vs multiple injection sites, imaging guidance (fluoroscopy vs ultrasound), and combination with intra-articular delivery. Where studies reported insufficient detail on these parameters, we contacted corresponding authors for additional information.

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies. Each study was graded for methodological rigor, including randomization, blinding, completeness of outcome data, and selective reporting. Level of evidence was classified according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine criteria.

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with values > 75% considered substantial heterogeneity precluding meta-analysis. Clinical heterogeneity was evaluated by systematically comparing study populations (age, sex, OA severity), intervention characteristics (BMAC volume, concentration, injection technique), and outcome assessment methods. Where significant heterogeneity was identified, we performed sensitivity analyses excluding outlier studies and conducted subgroup analyses based on predefined categories (early vs advanced OA, single vs combined injection routes, short vs long-term follow-up). Forest plots were constructed for comparable outcomes, though formal meta-analysis was not performed due to methodological diversity across studies.

Subgroup analyses were planned to compare outcomes between intra-articular, subchondral, and combined injection routes. Where possible, effect sizes were extracted or calculated, and heterogeneity across studies was evaluated using I2 statistics. Due to variability in study designs and outcome reporting, a meta-analysis was not performed; instead, a qualitative synthesis was undertaken to summarize trends and comparative efficacy.

The review protocol was registered prospectively in the PROSPERO database (CRD420251087709), ensuring transparency and methodological integrity. Ethical approval was not required as the study involved secondary analysis of published data. All included studies were cited appropriately, and data were interpreted in the context of current clinical practice and biologic rationale for targeting subchondral pathology in OA.

This systematic review included five clinical studies evaluating the efficacy of BMAC administered via subchondral or intra-articular injection for knee OA as shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of inclusion of studies in Figure 1. Of the included studies, three were RCTs, while two followed prospective cohort designs as shown in Table 1. The quality assessment of the included studies was satisfactory to be included in the analysis. The total pooled sample size comprised 298 knees, with each study comparing either subchondral BMAC injection alone, intra-articular injection alone, or a combination of both. Across all studies, clinical outcomes were assessed at multiple time points using standardised scoring systems - VAS, KOOS, WOMAC, IKDC, Tegner, Lysholm, and Knee Society Score (KSS). Subchondral BMAC injections consistently demonstrated superior improvements in functional scores, pain reduction, and imaging findings compared to intra-articular injections or placebo.

| Ref. | Country | Study type | Intervention | Control | Sample size (I/C) | Age (I/C) | Sex ratio (M:F, I/C) | KL grade (I/C) | Outcome measures | Follow-up duration |

| Hernigou et al[19], 2021 | France | PCS | BMAC SC | TKR | 140/140 | 75.4 (range 65-90) | 53:87 | Grade 2-4/grade 2-4 | KSS, BML volume, HKA angle | Approximately 15 years |

| Hernigou et al[17], 2021 | France | RCT | BMAC SC | BMAC IA alone | 60/60 | 64 ± 21 | 25:35/25:35 | Grade 1-4/grade 1-4 | KSS, MRI | Approximately 15 years |

| Madrazo-Ibarra et al[18], 2022 | India | RCT | BMAC SC | Placebo | 25/25 | 63.2 ± 8.2/66.5 ± 5.3 | 14:11/12:13 | Grade 3 & 4/grade 3 & 4 | KOOS, VAS | 12 months |

| Silva et al[16], 2022 | Italy | RCT | BMAC SC + IA | BMAC IA alone | 43/43 | NR | NR | Grade 3 & 4/grade 3 & 4 | WOMAC, Tegner, IKDC, EQ-VAS | 12 months |

| Kon et al[15], 2023 | France | PCS | BMAC SC | None | 30/NIL | 56.4 ± 8.1 | 19:11 | Grade 2 & 3/NIL | IKDC, KOOS, WORMS MRI | 24 months |

The RCT by Silva et al[16] in 2022 compared intra-articular BMAC alone to combined subchondral plus intra-articular injections. At 6 months, Tegner and WOMAC scores favoured the combined approach, with improved IKDC and EuroQol-VAS scores. Similarly, Hernigou et al[17] in 2021 reported significantly higher KSS scores in the subchondral BMAC group compared to intra-articular alone. MRI findings indicated reduced BML volumes in the subchondral group, along with slowed progression toward TKA. Madrazo-Ibarra et al[18] in 2022 compared subchondral BMAC to placebo, with KOOS scores improving from 49.1 ± 1.9 to 61.2 ± 6.3 at 12 months. This study reinforced the pain-alleviating and function-enhancing role of targeted BMAC delivery into subchondral bone.

A long-term prospective cohort study by Hernigou et al[19] in 2021 observed sustained benefits with subchondral injections over two years. Among 140 patients, KSS scores improved from 57 ± 12 to 87.3 ± 12, and BML volumes decreased significantly (mean regression of 2.1 cm3). The authors also reported a correction in Hip-Knee-Ankle angle and delayed progression to TKA, further suggesting the disease-modifying effect of subchondral biologic therapy. Kon et al[15] in 2023 conducted a prospective cohort study evaluating subchondral injections with MRI-based Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score scoring. Patients experienced progressive improvement in IKDC (from 40.5 ± 12.5 to 62.6 ± 19.4) and KOOS scores over 12 months. Structural MRI revealed regression of BMLs and increased cartilage preservation in subchondral-treated knees.

No major adverse events were reported in any study. Subchondral BMAC injections consistently showed superior clinical and radiological outcomes relative to intra-articular-only approaches or placebo. The cumulative findings em

Emerging clinical data suggest that injecting BMAC into the subchondral bone can achieve equal or superior outcomes compared to the traditional intra-articular route. The most direct evidence comes from a randomized trial by Hernigou et al[17], in which 60 patients with bilateral knee OA received an intra-articular BMAC injection in one knee and a guided subchondral BMAC injection in the contralateral knee. Over long-term follow-up (mean approximately 15 years), the subchondral-treated knees fared significantly better: They had a prolonged time to joint replacement and greater pain relief and functional improvement than their intra-articular treated counterparts[17]. In fact, knees that received BMAC into the bone had a markedly lower conversion to TKA - reflecting a genuine disease-modifying effect - whereas the intra-articular injections, while reducing pain initially, did not alter the course of structural degeneration[17]. This head-to-head comparison provides high-level evidence that targeting the subchondral compartment can enhance the long-term efficacy of BMAC therapy. Consistent with these findings, a multicenter pilot study employing combined subchondral plus intra-articular BMAC reported durable clinical benefits at 2 years and significant reductions in MRI-detected bone marrow edema lesions[15]. Patients in that cohort experienced improved pain and function scores that remained above baseline through 24 months, with a low failure rate, and imaging showed that subchondral BMAC delivery led to resolution of bone edema that was not observed with typical intra-articular treatments[15]. These outcomes reinforce the notion that accessing the subchondral bone can augment the symptomatic and structural impact of BMAC.

It is important to acknowledge that not all studies have found a dramatic clinical divergence between subchondral and intra-articular routes. A prospective case-matched study by Centeno et al[20] compared two groups of patients with advanced knee OA and MRI-confirmed BMLs: One group received intra-articular BMAC and platelet product injections alone, while the other received a combined intra-articular plus subchondral regimen. After treatment, both groups showed significant improvements in pain and function, but the differences between the intra-articular only and subchondral + intra-articular groups did not reach statistical significance in patient-reported outcomes[20]. This suggests that intra-articular BMAC is beneficial on its own, and the added value of a subchondral injection might be subtle or require larger sample sizes to detect. The authors noted a trend toward better outcomes in the combined injection group (especially in patients with large BMLs) that likely failed to reach significance due to limited power. Additionally, their use of adjunct platelet products and heterogeneity in injection techniques could have confounded the results[20]. Despite this isolated null finding, the overall body of evidence - including the positive RCT data - points to at least equivalence, and likely superiority, of subchondral BMAC delivery in appropriate candidates. Crucially, none of the comparative studies have found subchondral injection to be inferior to intra-articular injection; at worst, it appears comparable in symptomatic benefit, and at best it yields longer-lasting and more profound improvements in joint health. Given that the subchondral route can be combined with intra-articular injection (rather than replacing it entirely), many clinicians are adopting a dual-route approach to maximize patient outcomes[21].

Several biological and biomechanical factors may explain why targeting the subchondral bone with BMAC could enhance treatment efficacy. Mechanically, OA frequently entails increased subchondral bone turnover, microfractures, and loss of bone quality, which in turn destabilize the overlying cartilage. BMAC injected into these subchondral regions can directly participate in repair of microdamage and strengthening of the bone structure. The aspirate’s osteoprogenitor cells and growth factors (e.g., transforming growth factor-β, vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor) can stimulate new bone formation and angiogenesis within BMLs, potentially restoring the shock-absorbing capacity of the osteochondral unit[22]. By “bolstering the foundation” of the joint, subchondral BMAC may reduce abnormal mechanical stress on cartilage and mitigate one driver of cartilage breakdown. In essence, this approach treats the often-overlooked bone pathology of OA, analogous to how the surgical procedure subchondroplasty injects bone substitute to stabilize BMLs. Early BMAC studies indeed show bone lesion regression on MRI after subchondral injections[4], indicating that the therapy is modifying the bone structure in a favorable way.

Biologically, the subchondral bone is a rich source of cross-talk in the joint, and targeting it allows BMAC to exert wider intra-articular effects. The subchondral space in OA is characterized by an inflammatory and catabolic milieu (e.g., elevated interleukin-6, prostaglandin E2, and abnormal Wnt signaling in osteoblasts) that can diffuse upward and damage cartilage[4]. Delivering MSCs and anti-inflammatory cytokines via BMAC into the bone can help counteract this pathological microenvironment. MSCs are known to secrete mediators that suppress osteoclast activity and inflammation; thus, a concentrated presence of these cells in subchondral lesions may rebalance bone remodeling and reduce the production of cartilage-degrading enzymes[4]. In addition, recent histologic and imaging studies have confirmed channels and vascular connections between subchondral bone and articular cartilage[4]. This anatomical continuity means that therapeutic factors released by BMAC in the bone (such as growth factors, extracellular vesicles, or che

The success of subchondral BMAC injections has provocative implications for potentially altering the course of OA. Traditional intra-articular therapies (steroids, hyaluronic acid, even platelet-rich plasma) are largely symptom-oriented and have not demonstrated any ability to slow structural progression of OA. In contrast, the data emerging from subchondral BMAC studies suggest that it may be possible to at least partially reverse or retard some pathological features of OA. Patients treated with subchondral BMAC have shown evidence of cartilage repair and preservation on imaging. In one long-term trial, MRI quantification revealed that knees injected with BMAC in the subchondral bone had an increase in medial compartment cartilage volume (approximately +2.4% at 2 years) whereas OA typically causes progressive cartilage loss[4]. Although the regenerated tissue in these cases may be fibrocartilage (as second-look arthroscopy indicated), the finding of any cartilage gain is remarkable in a degenerative disease context and underscores the regenerative influence of the therapy[4]. Moreover, by targeting subchondral “bone marrow edema” lesions, BMAC appears to disrupt a vicious cycle of inflammation and degeneration. The significant regression of BML volume observed after subchondral BMAC injections (on the order of a few cubic centimeters less edema by 24 months) corresponds with reduced pain and improved function[4]. Because BML presence predicts cartilage loss and joint failure[9], their resolution suggests a true modification of disease trajectory. Clinically, this has translated into a delay in the need for joint re

The potential to modulate OA pathogenesis by addressing subchondral bone is supported by mechanistic studies. Laboratory research has shown that osteoarthritic subchondral bone undergoes pathological changes such as MSC senescence, pro-inflammatory gene expression, and aberrant bone remodeling (e.g., high RANKL levels and osteoblast hypertrophy)[22]. By introducing healthy autologous MSCs via BMAC, these deleterious processes might be countered. MSCs can differentiate and replace exhausted native progenitors, and their paracrine effects include inhibiting the nuclear factor-kappa B pathway and other inflammatory cascades in the joint[4]. Notably, intra-articular BMAC injections alone have not demonstrated such disease-modifying effects - as evidenced by the lack of MRI improvements in cartilage or BMLs in trials of intra-articular injection[4]. Structural benefits are seen when BMAC is placed subchondrally, reinforcing that the subchondral bone is a critical therapeutic target for altering disease progression. It also aligns with a broader understanding of OA as an organ-level failure involving bone-cartilage crosstalk, rather than a cartilage-centric wear-and-tear issue alone. Targeting the subchondral bone may help “reset” the joint homeostasis by restoring a healthier bone milieu, which protects cartilage and reduces pain generation. While more research is needed to conclusively prove disease modification, the current evidence is the most compelling for a minimally invasive injectable therapy in OA.

Synthesising evidence from heterogeneous studies presents several methodological challenges that warrant explicit acknowledgement. The included studies demonstrate substantial diversity in patient selection criteria, with some fo

Intervention heterogeneity adds another layer of complexity. BMAC preparation methods vary significantly between studies, from simple centrifugation protocols yielding (2-3) × concentration to sophisticated multi-step processes achieving (8-10) × concentration ratios. Cell viability and potency assessments are rarely standardized, making corre

Outcome assessment heterogeneity further challenges evidence synthesis. While most studies employ validated patient-reported outcome measures, the specific instruments vary (WOMAC vs KOOS vs IKDC), and few studies report minimal clinically important differences for their chosen measures. Imaging outcomes lack standardization, with some studies using qualitative MRI assessment while others employ quantitative cartilage thickness measurements or BML volumetrics. This methodological diversity, while reflecting the evolving nature of the field, limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions about optimal treatment protocols and expected outcomes.

The efficacy of BMAC treatment in knee OA can depend on technical factors related to the injection site and method. There is variability in how different studies and practitioners perform subchondral injections, which may contribute to differences in outcomes. Important considerations include the precise location of injection (e.g., femoral condyle vs tibial plateau, or targeting specific MRI-identified BMLs), the depth of delivery, volume of injectate, and use of image guidance. In the cited studies, subchondral BMAC is typically delivered under fluoroscopic or intraoperative guidance into areas of bone pathology. For example, Kon et al[15] injected approximately 5 mL of BMAC into each of two locations in the tibial plateau and femoral condyle under fluoroscopy, in addition to 4 mL intra-articular. Hernigou et al’s technique involved a larger volume (approximately 20 mL) of concentrated marrow injected into each of multiple subchondral sites around the knee, achieved in a surgical setting[4]. These protocol differences (single vs multiple injection points, combined intra-articular + subchondral vs subchondral alone, etc.) can influence how uniformly the BMAC is distributed in the subchondral bone and joint. It stands to reason that an injection directly into a sizable bone lesion under imaging guidance would yield more pronounced lesion filling and structural benefit than a blind intra-articular injection hoping for passive diffusion into bone. Consistent with this, trials that deliberately targeted BML regions showed clearer MRI improvements[4,15], whereas those that injected BMAC simply into the joint space generally did not alter MRI structural findings[4]. Another factor is the disease stage of the patient: Subchondral BMAC might provide the greatest incremental benefit in patients who have evident bone marrow edema or osteopenia changes on imaging (i.e., those in mid- to late-stage OA), whereas in very early OA with isolated cartilage softening, an intra-articular injection might suffice. Thus, patient selection and tailoring the injection technique to the individual’s pathology are critical for optimizing outcomes.

Some variability in outcomes may also stem from differences in BMAC preparation and composition. The concentration of MSCs and platelets in BMAC can vary widely depending on the volume of marrow aspirated, the device or protocol used for concentration, and whether any adjuncts (like platelet-rich plasma or calcium activators) are added. While these factors were not the primary focus of this review, they are worth noting because a higher cell dose or more potent biologic profile in the injectate could theoretically enhance efficacy. Standardization in reporting BMAC composition (e.g., number of nucleated cells or colony-forming units per mL) is needed in future studies to correlate therapeutic content with outcomes. Additionally, the concomitant use of other therapies differs - some protocols combine BMAC with arthroscopic debridement, microfracture, or scaffold implantation in one session[12]. These combined approaches (often seen in focal cartilage repair settings) were not the subject here, but they illustrate that BMAC’s effect can be context-dependent. In summary, the technique of delivery - including targeted subchondral injection - appears to be a key determinant of BMAC’s success, and careful attention to treating the “right lesion with the right method” will likely improve therapeutic consistency across studies.

Despite the encouraging results, the current literature on BMAC, especially via subchondral injection, has limitations that temper definitive conclusions. Many studies in this field are small-scale, single-arm case series or pilot trials without control groups. The positive outcomes reported, while promising, need validation in larger RCTs with appropriate comparators (e.g., BMAC intra-articular vs BMAC subchondral vs placebo). To date, only a handful of RCTs have been conducted, and most involve relatively short follow-up (1-2 years), except for a few notable long-term studies[4]. The heterogeneity of study designs also makes it challenging to compare results. Patient populations range from young patients with milder OA to elderly patients with end-stage OA, and the stage of disease likely influences how much regeneration is achievable. Some trials mixed BMAC with other injectables (platelet-rich plasma or platelet lysate), making it hard to isolate the effect of BMAC alone[20]. Outcome measures also vary - while most report pain and function scores, fewer report imaging outcomes or biomarker changes. There is also potential publication bias toward positive studies in the orthobiologics field; neutral or negative findings (like the Centeno et al’s study[20]) are less frequently published, which could skew the perceived efficacy.

Another limitation is the lack of standardization in what constitutes “BMAC”. Different commercial systems and preparation methods yield concentrates with varying cell counts and compositions. This inconsistency can lead to variable biological potency between studies[12]. Doses are not uniformly reported - for example, Hernigou et al’s extensive work[4] is notable for quantifying the average MSCs per mL delivered and correlating that with outcomes, but many other studies state the volume of injectate. For evidence synthesis, it would be ideal if future publications detail the cell dosage and viability in the BMAC product. Furthermore, the “active ingredient” in BMAC is multifactorial (MSCs, growth factors, etc.), so pinpointing the mechanism is difficult. We do not yet know if the therapeutic effect comes mainly from the live stem cells engrafting and differentiating or their paracrine signaling (which might be reproduced by cell-free approaches in the future).

From a methodological standpoint, blinding is challenging in these injection studies, mainly when one group receives a subchondral injection (often requiring drilling or fluoroscopy). Patients and providers are frequently aware of the treatment allocation, which could introduce bias in reported outcomes. Sham-controlled trials would strengthen the evidence, but are logistically and ethically complex for an invasive procedure. Additionally, there are limited data on long-term safety. While BMAC is autologous and generally considered safe (no immunogenic issues), injecting into bone marrow is not entirely benign - there is a small risk of infection, microfracture, or fat embolism, though serious adverse events have not been reported in the reviewed studies. Current reports indicate no major complications attributable to BMAC injections in the joint or bone[15], which is reassuring. Nonetheless, long-term surveillance for any unintended effects (such as aberrant bone formation or tumorigenesis, theoretically) is prudent given the novelty of this approach.

Despite encouraging results, current literature on subchondral BMAC faces substantial methodological limitations that constrain definitive conclusions. Sample sizes remain small across most studies, with individual cohorts ranging from 25-140 participants, limiting statistical power to detect meaningful differences and increasing susceptibility to type II errors. Follow-up durations vary considerably, with most studies reporting outcomes at 12-24 months, while only two studies provide data beyond five years. This temporal limitation precludes assessment of long-term durability and safety profiles essential for clinical adoption.

Study design heterogeneity presents additional challenges. Three studies employed randomized controlled designs, while two utilized prospective cohort methods without control groups, introducing potential selection bias and confounding variables. Patient populations demonstrate significant variability in age (mean range: 56-75 years), disease severity (Kellgren-Lawrence grades I-IV), and comorbidity profiles, making outcome generalization difficult. BMAC preparation protocols lack standardization across studies, with concentration ratios varying 3-fold and cell viability rarely reported, potentially contributing to outcome variability.

Methodological limitations include inadequate blinding in most studies due to procedural differences between subchondral and intra-articular routes, introducing potential performance and detection bias. Outcome assessment relies heavily on patient-reported measures (VAS, WOMAC, KOOS) with limited objective endpoints, while imaging outcomes lack standardized scoring systems across studies. Publication bias toward positive results remains a concern in the orthobiologics field, as evidenced by the paucity of negative studies in our systematic search.

The encouraging early findings on subchondral BMAC therapy pave the way for several important avenues of future research. Foremost, well-powered randomized trials are needed to confirm the superiority of subchondral plus intra-articular BMAC over conventional intra-articular treatment or placebo. At least one ongoing RCT is directly comparing combined intra-articular + subchondral BMAC against intra-articular BMAC alone[16], which will provide higher level evidence for the added value of the subchondral route. Future studies should incorporate MRI evaluations as standard, to objectively assess changes in cartilage thickness, BML size, and other structural endpoints in addition to clinical outcomes. A consensus on MRI scoring (e.g., Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score or MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score) and reporting of subchondral changes will be useful to compare across trials. Moreover, stratified analyses based on presence of baseline BMLs could clarify which patients benefit most from subchondral injections. It is plausible that patients with large BMLs or subchondral cysts gain more from targeted subchondral therapy than those without such findings. Identifying radiographic or MRI biomarkers of likely responders will help personalize treatment.

Another area for exploration is optimizing the delivery technique and BMAC product. Research could evaluate whether multiple targeted subchondral injections (for example, addressing each major BML in a knee) yield better outcomes than a single-site injection. The optimal volume and concentration of BMAC for subchondral use remain to be determined - too small a volume might not sufficiently fill lesion defects, whereas too large could cause pressure effects or extravasation. Biomechanical studies could assess how BMAC injection influences subchondral bone material properties or stiffness, as this could directly impact load distribution on cartilage. On the cellular front, investigating the fate of injected MSCs in vivo will illuminate how long they persist in subchondral bone and whether they truly engraft or primarily exert transient paracrine effects. Techniques like labeled cell tracking or biopsy of treated areas (in animal models or in patients undergoing subsequent surgery) could shed light here. Additionally, comparisons between BMAC and other cell-based strategies (e.g., culture-expanded MSCs or allogeneic “off-the-shelf” products) would be valuable, as culture-expanded cells might offer higher numbers but at greater cost and regulatory complexity. BMAC, being a point-of-care autologous product, has regulatory advantages that should be leveraged, but its constituents could potentially be enhanced (for instance, by adding adjuvant molecules or combining with scaffold materials that retain cells in subchondral defects).

Long-term follow-up of patients who receive subchondral BMAC is essential to determine if the early disease-modifying signals translate into meaningful outcome differences at 5, 10, or 15 years. It will be important to see if the delay in arthritis progression holds and whether repeated injections are needed to maintain benefit. If subchondral BMAC can consistently show prolonged TKA-free survival and sustained quality of life improvements, it could herald a shift in the treatment algorithm for knee OA - intervening at the level of bone biology to treat what has historically been managed as primarily a cartilage problem. Future research priorities must include adequately powered, multicenter RCTs with sample sizes exceeding 200 participants per arm to establish definitive efficacy. These studies should incorporate standardized BMAC preparation protocols, uniform outcome assessment tools, and a five-year follow-up period to evaluate long-term safety and disease-modifying potential. Comparative effectiveness research comparing subchondral BMAC against established treatments (corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, physiotherapy) will inform clinical decision-making and health economic evaluations. Biomarker studies identifying patient subgroups most likely to benefit from subchondral intervention will enable precision medicine approaches and optimize treatment selection algorithms.

| 1. | Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393:1745-1759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1458] [Cited by in RCA: 3063] [Article Influence: 437.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Li G, Yin J, Gao J, Cheng TS, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C, Zheng MH. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 602] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Čamernik K, Mihelič A, Mihalič R, Marolt Presen D, Janež A, Trebše R, Marc J, Zupan J. Increased Exhaustion of the Subchondral Bone-Derived Mesenchymal Stem/ Stromal Cells in Primary Versus Dysplastic Osteoarthritis. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020;16:742-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hernigou J, Vertongen P, Rasschaert J, Hernigou P. Role of Scaffolds, Subchondral, Intra-Articular Injections of Fresh Autologous Bone Marrow Concentrate Regenerative Cells in Treating Human Knee Cartilage Lesions: Different Approaches and Different Results. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:3844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shi X, Mai Y, Fang X, Wang Z, Xue S, Chen H, Dang Q, Wang X, Tang S, Ding C, Zhu Z. Bone marrow lesions in osteoarthritis: From basic science to clinical implications. Bone Rep. 2023;18:101667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhu X, Chan YT, Yung PSH, Tuan RS, Jiang Y. Subchondral Bone Remodeling: A Therapeutic Target for Osteoarthritis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:607764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hu Y, Chen X, Wang S, Jing Y, Su J. Subchondral bone microenvironment in osteoarthritis and pain. Bone Res. 2021;9:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 67.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Donell S. Subchondral bone remodelling in osteoarthritis. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:221-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tanamas SK, Wluka AE, Pelletier JP, Pelletier JM, Abram F, Berry PA, Wang Y, Jones G, Cicuttini FM. Bone marrow lesions in people with knee osteoarthritis predict progression of disease and joint replacement: a longitudinal study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:2413-2419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Muthu S, Kandasamy R, Palanisamy S, Palaniappan AA. Subchondral Cellular Density Decreases with Increasing Grade of Cartilage Degeneration in Knee Osteoarthritis - An Ex vivo Histopathological Analysis. J Orthop Case Rep. 2025;15:227-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pabinger C, Lothaller H, Kobinia GS. Intra-articular injection of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (mesenchymal stem cells) in KL grade III and IV knee osteoarthritis: 4 year results of 37 knees. Sci Rep. 2024;14:2665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park D, Koh HS, Choi YH, Park I. Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate (BMAC) for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review of Clinical Efficacy and Future Directions. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61:853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Si-Hyeong Park S, Li B, Kim C. Efficacy of intra-articular injections for the treatment of osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2025;7:100596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pabinger C, Kobinia GS, Dammerer D. Injection therapy in knee osteoarthritis: cortisol, hyaluronic acid, PRP, or BMAC (mesenchymal stem cell therapy)? Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1463997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kon E, Boffa A, Andriolo L, Di Martino A, Di Matteo B, Magarelli N, Trenti N, Zaffagnini S, Filardo G. Combined subchondral and intra-articular injections of bone marrow aspirate concentrate provide stable results up to 24 months. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:2511-2517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Silva S, Andriolo L, Boffa A, Di Martino A, Reale D, Vara G, Miceli M, Cavallo C, Grigolo B, Zaffagnini S, Filardo G. Prospective double-blind randomised controlled trial protocol comparing bone marrow aspirate concentrate intra-articular injection combined with subchondral injection versus intra-articular injection alone for the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e062632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hernigou P, Bouthors C, Bastard C, Flouzat Lachaniette CH, Rouard H, Dubory A. Subchondral bone or intra-articular injection of bone marrow concentrate mesenchymal stem cells in bilateral knee osteoarthritis: what better postpone knee arthroplasty at fifteen years? A randomized study. Int Orthop. 2021;45:391-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Madrazo-Ibarra A, Barve R, Carroll KM, Proner R, Topar C, Ibarra C, Coleman SH, Vad V. Carboplasty, a Simple Tibial Marrow Technique for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trial. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10:23259671221143743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hernigou P, Delambre J, Quiennec S, Poignard A. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell injection in subchondral lesions of knee osteoarthritis: a prospective randomized study versus contralateral arthroplasty at a mean fifteen year follow-up. Int Orthop. 2021;45:365-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Centeno C, Cartier C, Stemper I, Dodson E, Freeman M, Azuike U, Williams C, Hyzy M, Silva O, Steinmetz N. The Treatment of Bone Marrow Lesions Associated with Advanced Knee Osteoarthritis: Comparing Intraosseous and Intraarticular Injections with Bone Marrow Concentrate and Platelet Products. Pain Physician. 2021;24:E279-E288. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kon E, Boffa A, Andriolo L, Di Martino A, Di Matteo B, Magarelli N, Marcacci M, Onorato F, Trenti N, Zaffagnini S, Filardo G. Subchondral and intra-articular injections of bone marrow concentrate are a safe and effective treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, multi-center pilot study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29:4232-4240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Campbell TM, Churchman SM, Gomez A, McGonagle D, Conaghan PG, Ponchel F, Jones E. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Alterations in Bone Marrow Lesions in Patients With Hip Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1648-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/