Published online Oct 26, 2020. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i10.1133

Peer-review started: March 28, 2020

First decision: April 22, 2020

Revised: May 3, 2020

Accepted: August 24, 2020

Article in press: August 24, 2020

Published online: October 26, 2020

Processing time: 211 Days and 19 Hours

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) modified by gene transfer to express cardiac pacemaker channels such as HCN2 or HCN4 were shown to elicit pacemaker function after intracardiac transplantation in experimental animal models. Human MSC derived from adipose tissue (haMSC) differentiate into cells with pacemaker properties in vitro, but little is known about their behavior after intracardiac transplantation.

To investigate whether haMSC elicit biological pacemaker function in vivo after transplantation into pig hearts.

haMSC under native conditions (nhaMSC) or after pre-conditioning by medium differentiation (dhaMSC) (n = 6 pigs each, 5 × 106 cells/animal) were injected into the porcine left ventricular free wall. Animals receiving PBS injection served as controls (n = 6). Four weeks later, total atrioventricular (AV)-block was induced by radiofrequency catheter ablation, and electronic pacemaker devices were implanted for backup stimulation and heart rate monitoring. Ventricular rate and rhythm of pigs were evaluated during a follow-up of 15 d post ablation by 12-lead-ECG with heart rate assessment, 24-h continuous rate monitoring recorded by electronic pacemaker, assessment of escape recovery time, and pharmacological challenge to address catecholaminergic rate response. Finally, hearts were analyzed by histological and immunohistochemical investigations.

In vivo transplantation of dhaMSC into the left ventricular free wall of pigs elicited spontaneous and regular rhythms that were pace-mapped to ventricular injection sites (mean heart rate 72.2 ± 3.6 bpm; n = 6) after experimental total AV block. Ventricular rhythms were stably detected over a 15-d period and were sensitive to catecholaminergic stimulation (mean maximum heart rate 131.0 ± 6.2 bpm; n = 6; P < 0.001). Pigs, which received nhaMSC or PBS presented significantly lower ventricular rates (mean heart rates 47.2 ± 2.5 bpm and 37.4 ± 3.2 bpm, respectively; n = 6 each; P < 0.001) and exhibited little sensitivity towards catecholaminergic stimulation (mean maximum heart rates 76.4 ± 3.1 bpm and 60.5 ± 3.1 bpm, respectively; n = 6 each; P < 0.05). Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of hearts treated with dhaMSC revealed local clusters of transplanted cells at the injection sites that lacked macrophage or lymphocyte infiltrations or tumor formation. Intense fluorescence signals at these sites indicated membrane expression of HCN4 and other pacemaker-specific proteins involved in cardiac automaticity and impulse propagation.

dhaMSC transplanted into pig left ventricles sustainably induced rate-responsive ventricular pacemaker activity after in vivo engraftment for four weeks. The data suggest that pre-conditioned MSC may further differentiate along a pacemaker-related lineage after myocardial integration and may establish superior pacemaker properties in vivo.

Core Tip: Differentiated human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue (dhaMSC) transplanted into the myocardium of domestic pigs are able to generate a biological pacemaker system in vivo. Electrocardiogram recordings and immunohistochemical analyses of pigs with transplanted dhaMSC indicated successful biological pacemaker generation. Pre-conditioning of cells was achieved by in vitro treatment of human mesenchymal stem cells in differentiation culture medium. Due to their reduced immunoreactivity, xenogeneic transplantation of human MSC into pig hearts was feasible without immunosuppression. dhaMSC maintained their immunoprivileged status over time.

- Citation: Darche FF, Rivinius R, Rahm AK, Köllensperger E, Leimer U, Germann G, Reiss M, Koenen M, Katus HA, Thomas D, Schweizer PA. In vivo cardiac pacemaker function of differentiated human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue transplanted into porcine hearts. World J Stem Cells 2020; 12(10): 1133-1151

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v12/i10/1133.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v12.i10.1133

Loss or dysfunction of sinoatrial nodal cells causes sick sinus syndrome, often requiring the implantation of an electronic pacemaker[1]. With respect to technical limitations of electronic pacemaker devices, research efforts are aimed at developing biological alternatives that might adapt more adequately to physiological requirements of the patients. In search for a novel approach to overcome electronic pacemakers, multiple approaches successfully utilized biological pacemakers in vitro and/or in large animal models using multiple gene or cell therapeutic strategies[2,3].

Gene therapy approaches have used pacemaker-specific genes delivered to cardiac tissue by viral vectors[4,5]. In vivo studies conducted in dogs[6] and pigs[7] demonstrated the generation of biological pacemaking by expressing depolarizing ion channels such as HCN2[8], HCN4[9], or sinoatrial nodal transcription factor TBX18[7]. However, gene therapy is limited by non-sustained effects of gene transfer[7] and risk of neoplasia[10]. Stem cell therapy offers an alternative approach to biological pacemaking, aiming at the replacement of lost or dysfunctional pacemaker cells. Human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are attractive candidates as they are easily obtained from adipose tissue or bone marrow, can be expanded to high numbers in vitro and show the ability to differentiate into several mesenchymal cell lineages[11]. Applied in a xenogeneic setting, hMSC were reported not to induce immune responses or inflammation[12,13]. However, the efficacy of MSC differentiation into cardiac myocytes is limited as transdifferentiation requires potentially teratogenic substances such as 5-azacytidine (5-aza) or amphotericin (AMPH), hampering its use with respect to a future clinical application[14,15]. To establish biological pacemaking, a hybrid model combining gene and stem cell therapy by introducing HCN2 into MSC[16] has been proposed. According to this approach, MSC primarily served as a "vector shuttle" to guide the depolarizing gene HCN2 to the heart. Recently, we reported the differentiation of human MSC (hMSC) derived from adipose tissue into cells with cardiac pacemaker characteristics[17]. Pacemaker cell differentiation was achieved by cell culture using a customized cell medium, omitting the need for genetic manipulation.

Here, we asked whether differentiated hMSC derived from adipose tissue (dhaMSC), according to our customized protocol[17] may elicit biological pacemaker function after transplantation into porcine myocardium. To this end, we performed intramyocardial implantation of dhaMSC in pigs with experimental total AV block to elucidate the capacity of dhaMSC to integrate within the myocardium and to generate escape pacemaker activity.

Human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue (haMSC) were isolated by abdominal plastic surgery. Isolation and handling of haMSC were approved by the local ethical committee (University of Heidelberg ethical committee number: S-462/2010). Cells were cultured in hMSC expansion medium as previously described[17].

Native haMSC (nhaMSC) were cultured for 4 wk in serum-free differentiation medium[17] free from teratogenic substances. In detail, differentiation medium comprised RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), 10 mL 50x B27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 mL 105 UI penicillin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 mL 105 µg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 10 ng/mL human recombinant BMP4 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NY, United States)[18].

To visualize MSC within porcine myocardium, dhaMSC and nhaMSC were incubated with enhanced green fluorescence protein (eGFP)-lentivirus (CMV-Null-GB, Amsbio, Abingdon, United Kingdom) before they were injected into porcine myocardium. A multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 proved to be optimal for successful cell infection. Twenty-four hours after infection, fresh medium was added without discarding the medium containing the lentiviral particles. Forty-eight hours post-infection, the medium was changed and 72-96 h after infection, the eGFP signal was visualized using fluorescence microscopy. eGFP positive cells were sorted by “BD FACSAriaII” (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) in order to achieve high purity of eGFP positive cells.

To localize dhaMSC within porcine myocardium, cells were labeled with superparamagnetic iron oxides (SPIOs)[19]. In brief, cells were incubated for 18 h in expansion medium containing 25 µg iron (Endorem®, Guerbet GmbH, Germany) and 0.75 µg Poly-L-lysine (PLL, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) per mL, respectively. The cells were then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific), trypsinized and resuspended in PBS containing 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 2 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 1 × 107 cells/mL. Pigs with transplanted SPIO-labeled dhaMSC underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in deep propofol-sedation (intravenous (IV) bolus of 1 mg/kg body weight (BW) followed by 5 mg/kg BW/h; AstraZeneca GmbH, Wedel, Germany) 2, 5 and 20 d post-cell transplantation using a 1.5 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging system (Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

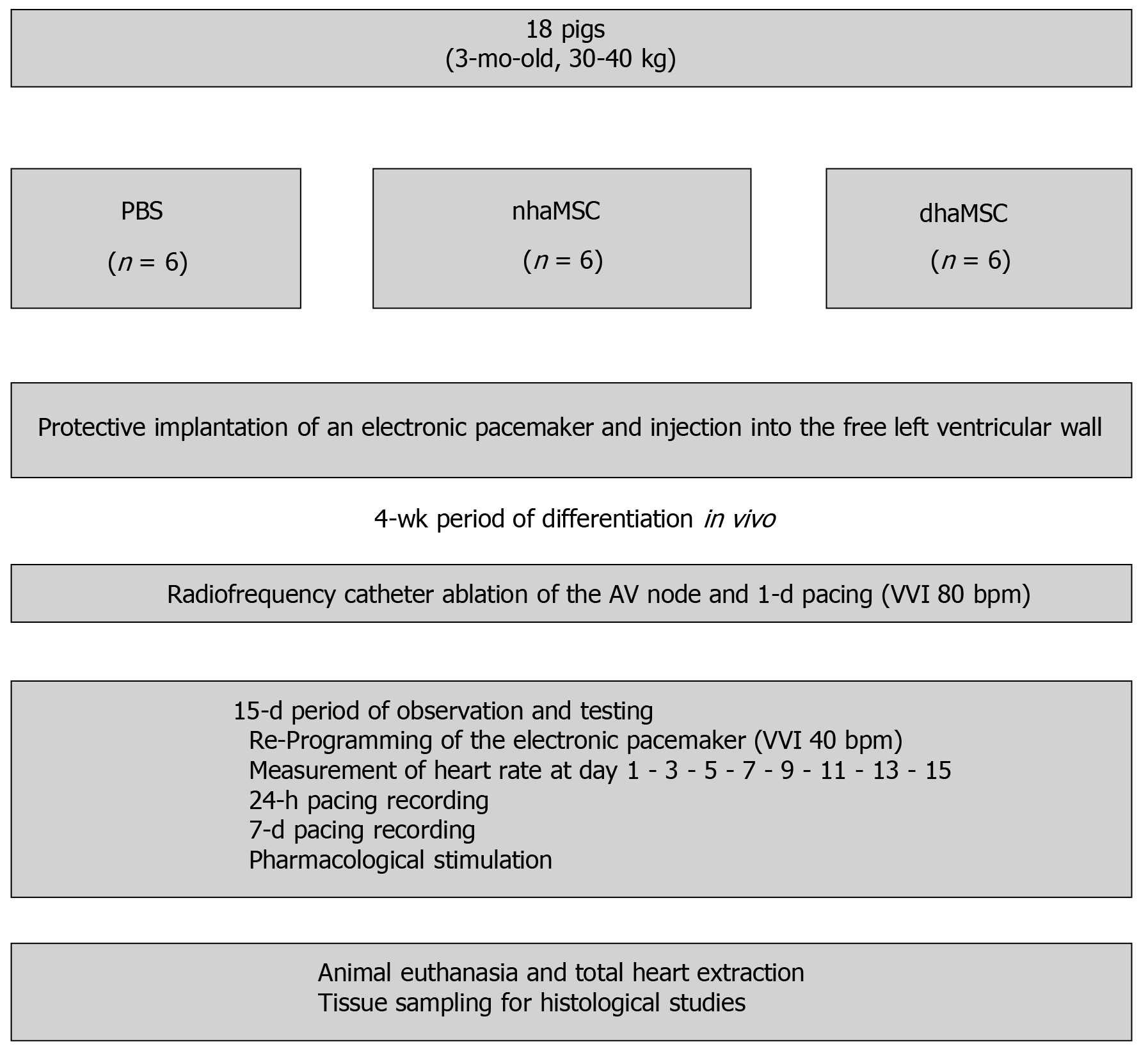

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institute of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and the European Community guidelines for the use of experimental animals. Protocols were approved by the local regulatory authority (AZ #359185.81/G-67/11, Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe, Germany). A summary of the experimental procedure is depicted in Figure 1.

A total of 18 domestic pigs (body weight 30 to 40 kg) were used in the study. Prior to first surgical procedure, each pig was sedated with azaperone (2 mg/kg BW; Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Neuss, Germany) intramuscular (i.m.), ketamine (10 mg/kg BW; Intervet, Unterschleißheim, Germany) i.m. and midazolam (0.5 mg/kg BW; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) i.m. Anesthesia was managed using propofol IV (1 mg/kg BW) and isoflurane ventilation (1%-2%; Baxter, Unterschleißheim, Germany). Median thoracotomy and pericardiotomy were performed and 5 × 106 eGFP-labeled dhaMSC (n = 6) or 5 × 106 eGFP-labeled nhaMSC (n = 6), resuspended in 0.6 mL differentiation expansion medium or 0.6 mL of PBS were injected subepicardially into the free wall of left ventricle, using a 30 Gauge needle, respectively. The injection site was marked with a suture. We then implanted a transvenous single-chamber cardiac pacemaker device (Medtronic Kappa, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States) for backup ventricular pacing. A bipolar active fixation pacing lead (4042 CapSure SP, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States) was inserted via the right external jugular vein and fixed in the right ventricle under fluoroscopic guidance. The lead was connected to the pacemaker unit placed in a subcutaneous pocket at the neck of the animals. Postoperatively, penicillin/dihydrostreptomycin suspension IV (20 mg/kg BW; Livisto, Senden-Bösensell, Germany) and Temgesic (0.3 mg; Indivior PLC, VA, United States) IV were administered.

Four weeks after cell/PBS application, atrioventricular (AV) node ablation was performed by radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA). To this end, pigs were sedated with azaperone (2 mg/kg BW) i.m., ketamine (10 mg/kg BW) i.m. and midazolam (0.5 mg/kg BW) i.m. AV node ablation was performed by transvenous power-controlled RFCA (Cerablate easy catheter, bipolar, 4-mm tip and HAT 200 RF generator; Dr. Osypka GmbH, Rheinfelden, Germany). The ablation catheter was inserted via preparation of the right femoral vein and guided to the heart under fluoroscopic control. Successful ablation of the AV node was confirmed by repeated post-procedural ECGs. Immediately after RFCA, the intervention rate of the electronic pacemaker device was set to 80 beats/min (bpm) (VVI 80). One day later and during the subsequent 15-d observation period, it was programmed to 40 bpm (VVI 40).

Throughout the 15-d observation period following RFCA, the intrinsic heart rate of pigs was measured every other day. To this end, the intervention rate of the electronic pacemaker device was switched from 40 to 30 bpm. Moreover, the heart rate and rhythm of pigs were evaluated by 12-lead-electrocardiography (ECG), continuous rate monitoring (24-h recording by electronic pacemaker) and assessment of ventricular escape recovery times (VERT). To evaluate VERT, pigs were electrically paced with an intervention rate of 80 bpm for 30 s. The electronic pacemaker device was then programmed to a pacing frequency of 30 bpm to start recording ventricular escape rhythms. The time between the last paced QRS complex and the first intrinsic QRS complex was described as VERT. At day 14 of the observation period, chronotropic response of rhythm was evaluated by delivery of epinephrine (1 mg; Sanofi, France) IV and atropine (0.5 mg; B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany) IV.

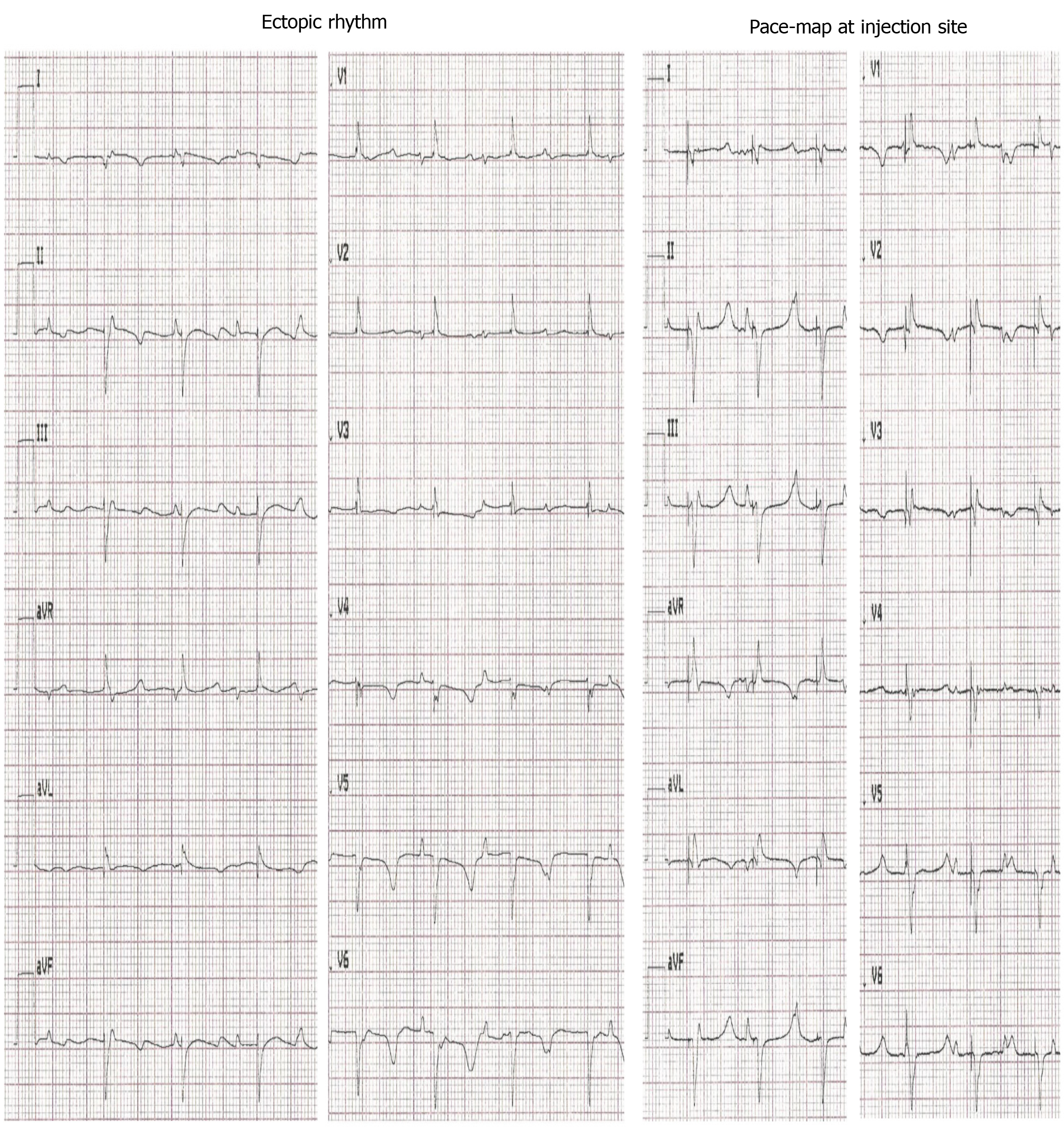

After a 15-d period of observation and testing, the final experiment aimed at harvesting of the hearts and histological analysis of the myocardium containing the nhaMSC and dhaMSC injected was conducted. For the final experiment, the pigs were anesthetized with propofol (1 mg/kg BW), and ventilated with isoflurane (1%-2%). Hearts were then exposed through a median sternotomy. Pace-mapping experiments were undertaken by stimulation at the site of cell injection using an epicardial electrode connected to an external pacemaker (Osypka, PACE 101 H) choosing a pacing rate 20 bpm higher than the prevalent escape rate. 12-lead ECG monitoring was performed, and the electrical activation front of spontaneous and paced rhythms was evaluated with respect to similarity and origin. Hearts were finally arrested by application of KCl (1 mol/L) IV in anesthetized animals, and washed in 0.9% NaCl. Cardiac regions of interest were excised and probes were frozen on isopentane/dry ice and stored at -80°C.

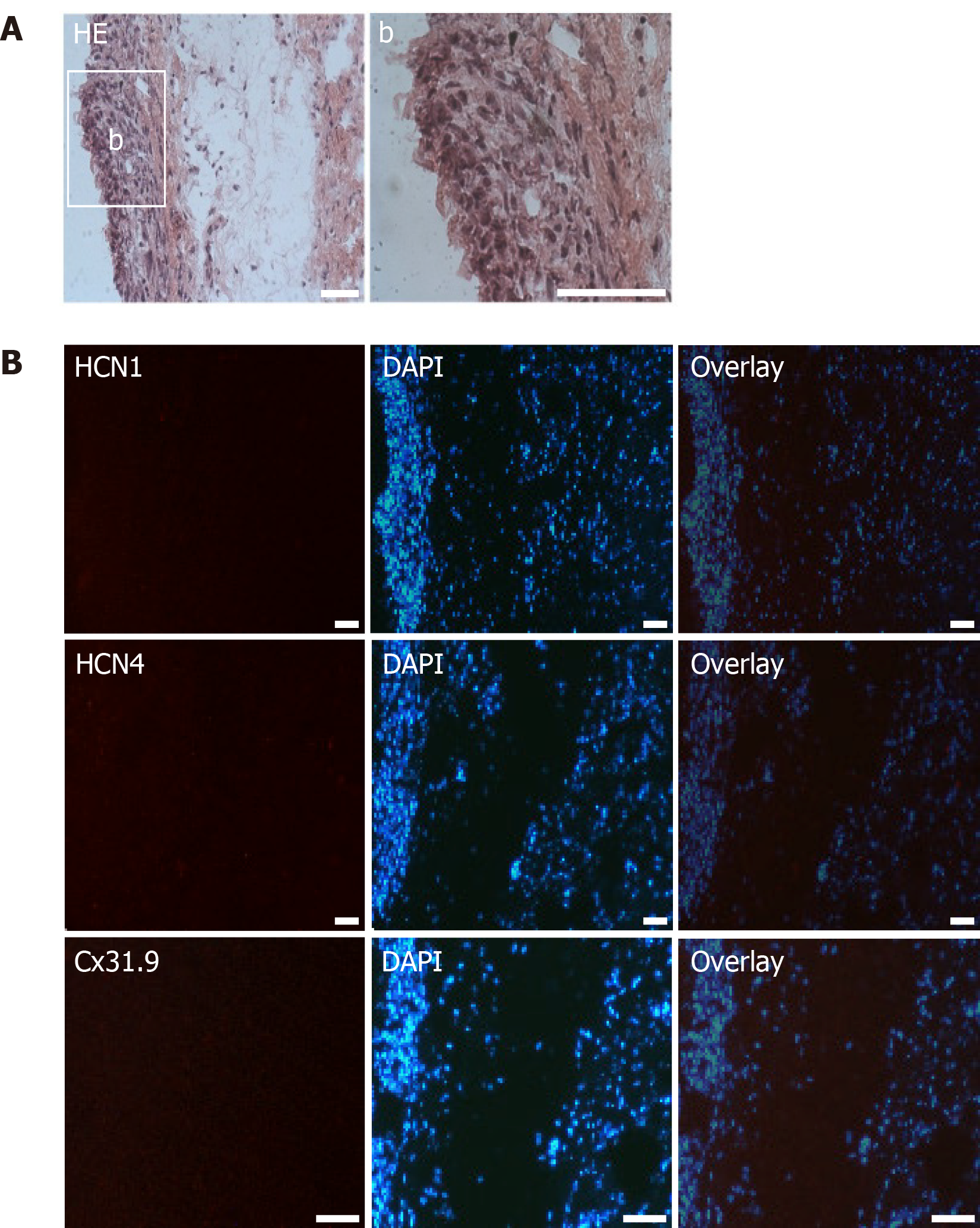

Frozen cardiac tissue was sliced into sections of 10 mm at -15°C to -20°C using a cryotome (microtome 5030; Bright Instrument Co. Ltd., Huntingdon, United Kingdom) and stored at -20°C. After several washes with PBS, the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) following standard protocols and analyzed by light microscopy using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). For immunohistochemistry, sections were rinsed with PBS, incubated in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature, treated with 0.1 mol/L glycine for 60 min, and incubated in blocking solution (2% bovine serum albumin in PBS) for 30 min. The sections were incubated with first antibodies overnight at 4°C in 2% BSA/PBS: anti-HCN1 (IgG, Alomone Labs) 1:200, anti-HCN2 (IgG, Alomone Labs) 1:200, anti-HCN4 (IgG, Alomone Labs) 1:200, anti-Cav1.2 (IgG, Abcam) 1:100, anti-Cx31.9 (IgG, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) 1:200, anti-Cx45 (IgG, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) 1:200 and anti-calprotectin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, United States) 1:200. The next day, the sections were rinsed with PBS (3 × 2 min) and incubated with secondary antibodies, diluted 1:200 in 2% BSA/PBS for 4 h at 4°C: MFP555 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) and MFP488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (MoBiTec, Göttingen, Germany). Nuclei were counterstained with 300 nmol/L 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Thermo Fisher Scientific)/PBS solution. Sections were mounted with Citifluor Glycerol/PBS Solution (Agar Scientific, Stansted, United Kingdom) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus IX 70 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Confocal microscopy was performed using a Leica SP2 AOBS confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Heart rate values were depicted by calculating the arithmetic mean as well as the standard error of the mean ± SE). Comparisons between multiple groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey posthoc test. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. Differences were judged significant at confidence levels > 95% (P < 0.05).

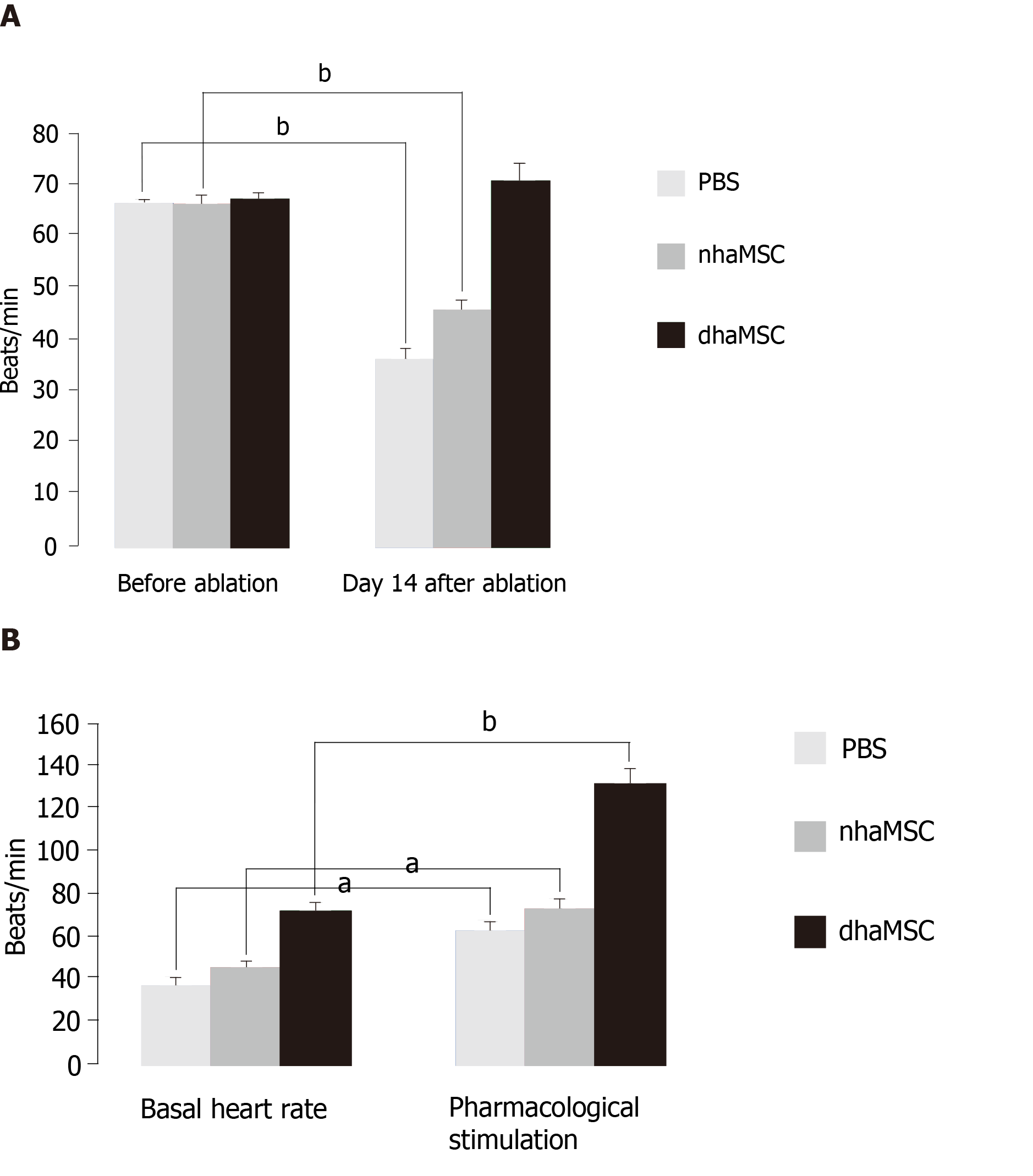

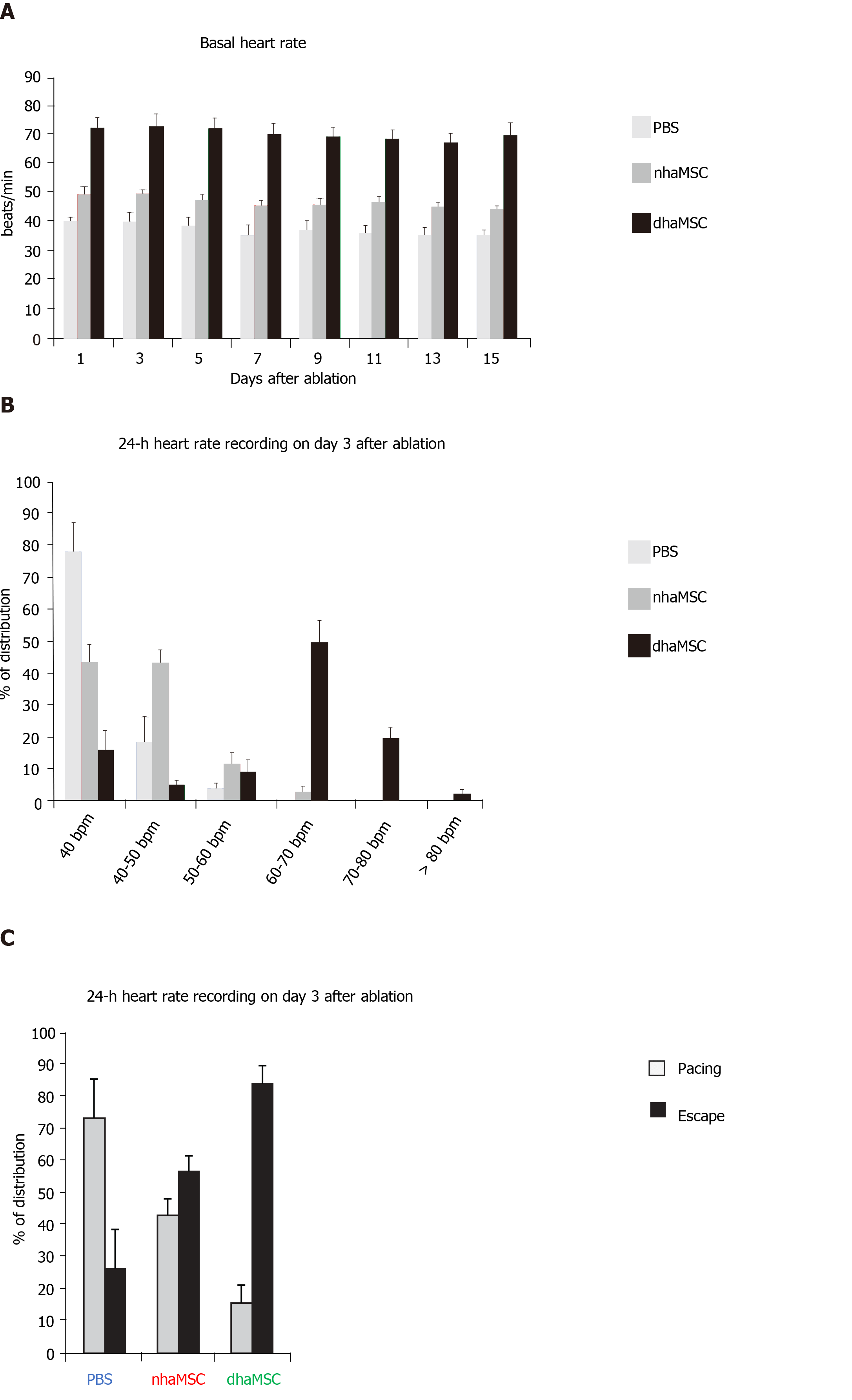

We assessed heart rate by ECG recordings in 18 pigs treated with dhaMSC, nhaMSC or PBS injection (6 pigs per group, respectively) (Figure 2A). During the first 4 wk following cell or PBS injection prior to AV node ablation, sinus heart rates of pigs were stable over time and similar within the 3 groups. Average values of heart rate at rest were 65 ± 0.8 bpm in pigs with transplanted dhaMSC, 64 ± 0.9 bpm in pigs with transplanted nhaMSC and 64 ± 0.8 bpm in pigs treated with PBS (Figure 2A). Fourteen days after RFCA of the AV node, pigs transplanted with dhaMSC showed regular ventricular rhythms with rates at physiological levels (mean rate 72.2 ± 3.6 bpm, n = 6) (Figure 2A). By contrast, ventricular rate was significantly lower in pigs transplanted with nhaMSC or treated with PBS (47.2 ± 2.5 bpm and 37.4 ± 3.2 bpm, respectively, P < 0.001 for both) (Figure 2A). Of note, persistent total AV block could be confirmed by multiple ECG recordings in all animals evaluated throughout the observation period.

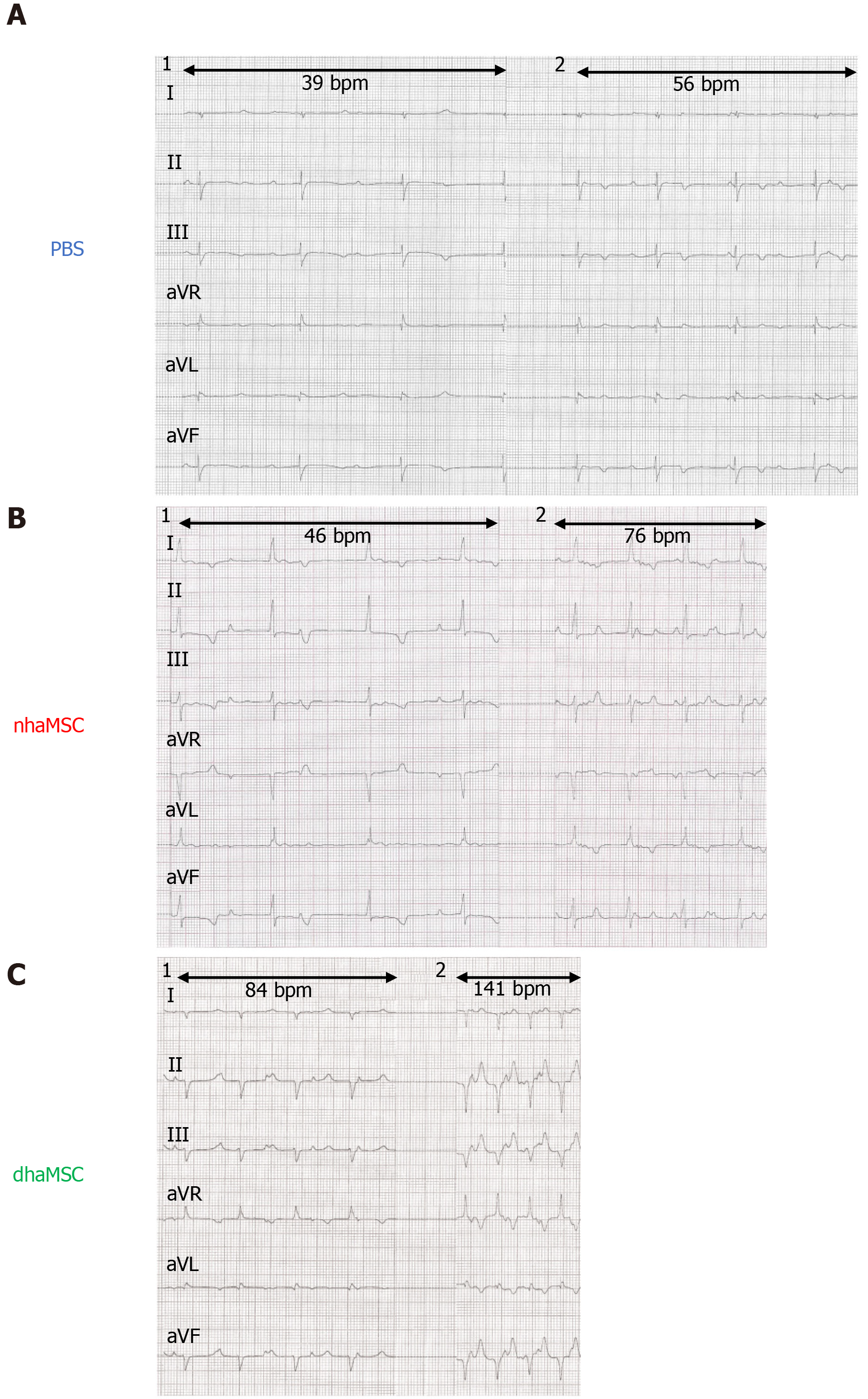

To evaluate the nature and origin of escape rhythms after experimental total AV block, the intervention rate of the electronic pacemaker device was changed to 30 bpm. To localize the origin of the escape beats, we performed pace-mapping by stimulating the injection site with an epicardial electrode using a pacing rate 20 bpm higher than the prevalent escape rate. For pigs transplanted with dhaMSC, a complete 12/12 matching of escape and pace-mapped beats was observed in the 12-lead ECG (Figure 3). By contrast, pace-maps and escape rhythms of pigs transplanted with nhaMSC or treated with PBS differed, indicating an origin of spontaneous rhythms other than the site of injection (Figure 4, left column).

At observation day 14, pigs were stimulated with epinephrine (1 mg) IV and atropine (0.5 mg) IV. Catecholaminergic stimulation increased heart rate in all groups, but pigs transplanted with dhaMSC in particular showed pronounced chronotropic response (Figure 2B; Figure 4, right column) with a rise in heart rate from 72.2 ± 3.6 bpm to 132.5 ± 6.5 bpm (P < 0.001) (Figure 2B). In pigs transplanted with nhaMSC, heart rate increased from 47.2 ± 2.5 bpm to 76.4 ± 3.1 bpm (P < 0.05), and in pigs treated with PBS from 37.4 ± 3.2 bpm to 60.5 ± 3.1 bpm (P < 0.05) (Figure 2B).

During the 15-day observation period following RFCA, intrinsic heart rates of pigs transplanted with dhaMSC, nhaMSC or treated with PBS were recorded every other day (Figure 5A). To avoid electrically paced rhythms being recorded, the intervention rate of the electronic pacemaker device was switched from 40 to 30 bpm. Importantly, intrinsic heart rates of pigs with transplanted dhaMSC remained high and stable over time (Figure 5A). During 24-h continuous rate recording, heart rate in the majority of pigs with transplanted dhaMSC ranged between 60-70 bpm (Figure 5B). By contrast, the heart rate of pigs with transplanted nhaMSC mainly ranged between 40-50 bpm or even below 40 bpm (Figure 5B). Pigs treated with PBS primarily displayed heart rates below 40 bpm (Figure 5B). To determine if the recorded heartbeats were electrically paced or spontaneous ventricular captures, we analyzed the percentage of ventricular paced (V-paced) and sensed (V-sensed) rhythms on pacemaker interrogation (Figure 5C). The 24-h continuous rate recordings mainly comprised spontaneous ventricular rhythms in pigs with transplanted dhaMSC, whereas the majority of rhythms in pigs treated with PBS were paced (Figure 5C).

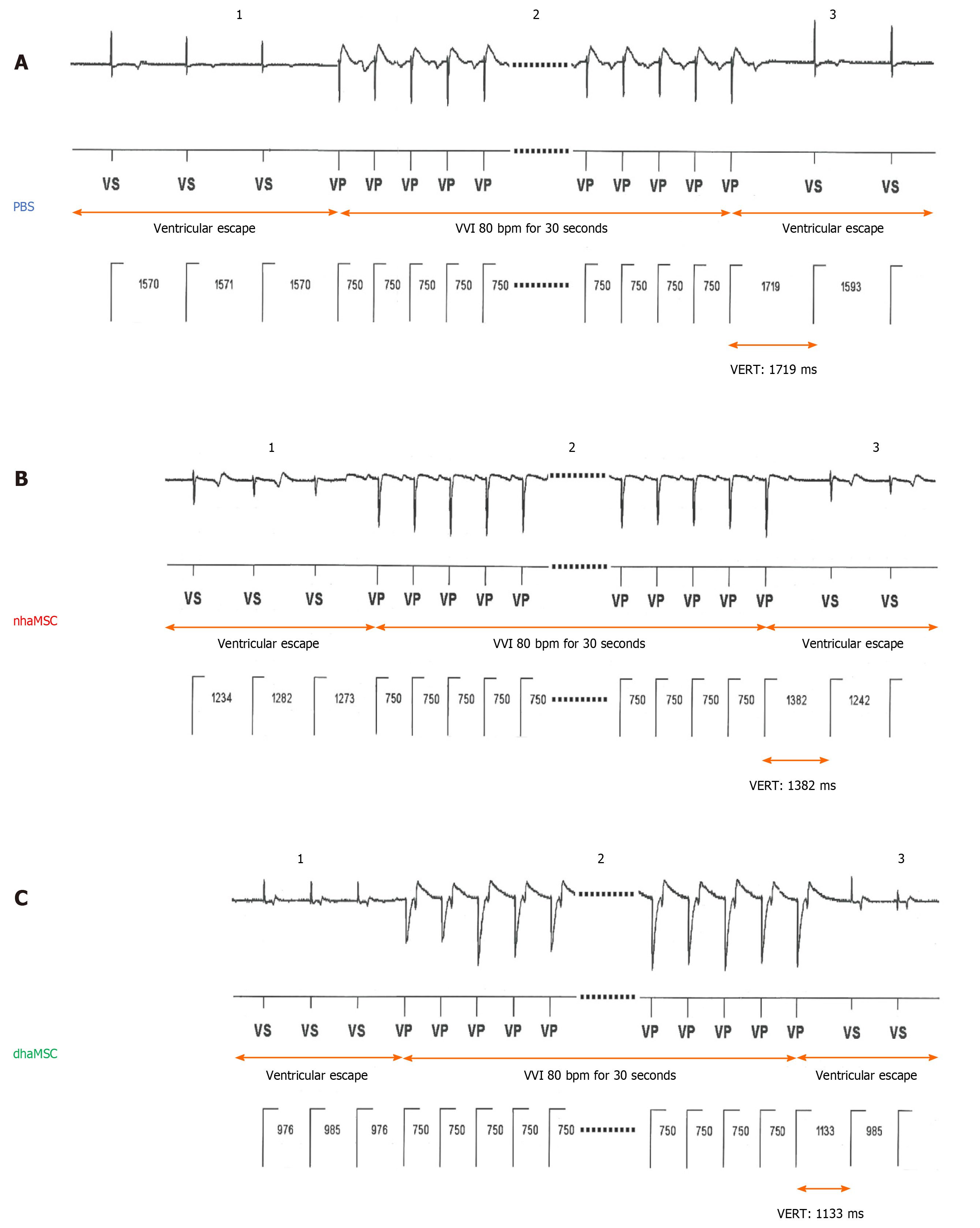

To analyze characteristics and response of ectopic ventricular pacemaker activity after experimental total AV block, we investigated the ventricular escape recovery time (VERT), using the implanted electronic pacemaker device. Pigs with transplanted dhaMSC displayed average VERT values of 1135 ± 23 ms, which were significantly shorter than VERT values recorded in pigs transplanted with nhaMSC (1390 ± 21 ms, P < 0.05) or treated with PBS (1724 ± 29 ms, P < 0.05) (Figure 6).

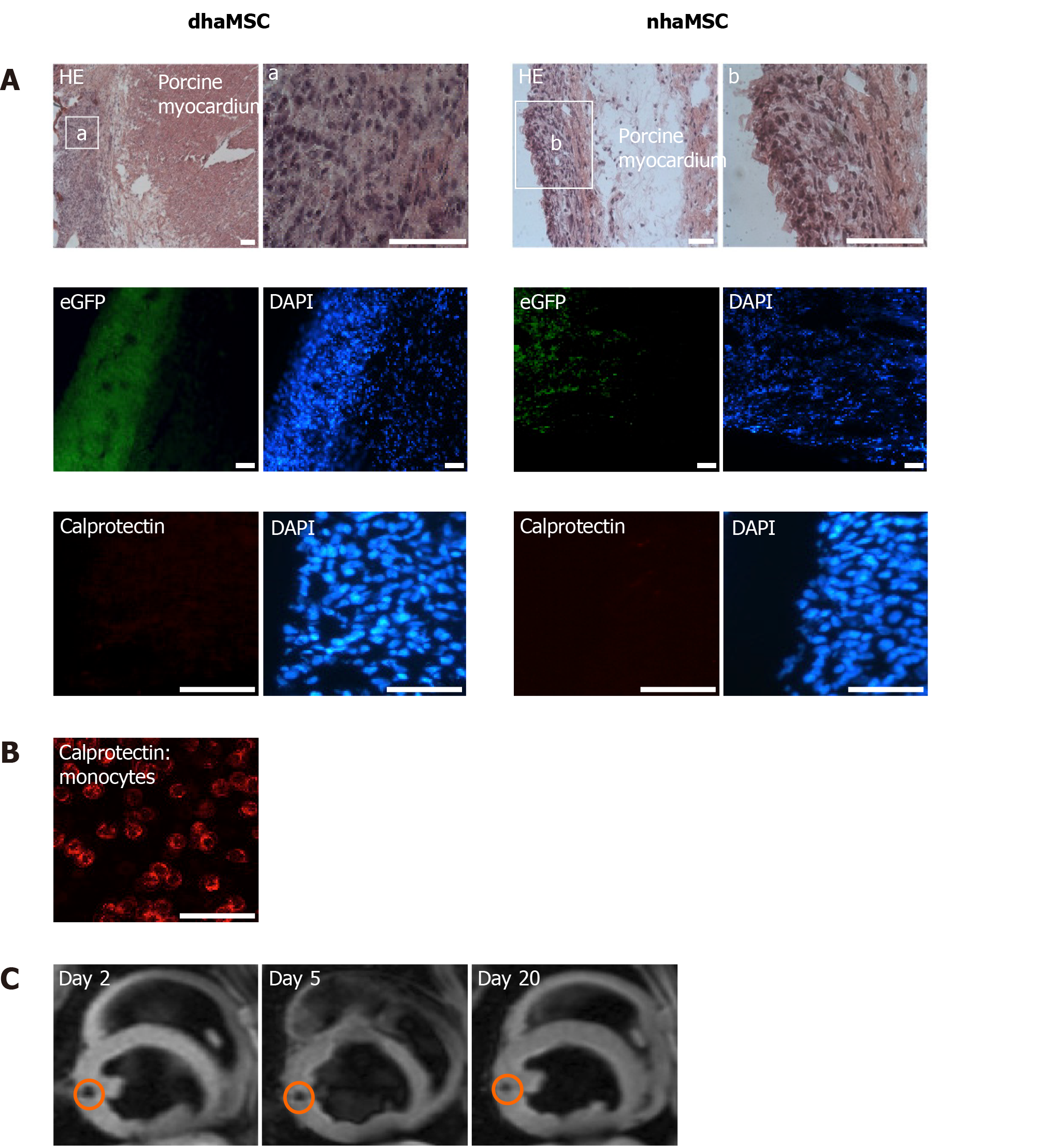

Histological examinations of cardiac sections at the area of dhaMSC and nhaMSC transplantation aimed to determine cellular localization and characterization of the injection sites. Moreover, we aimed to elucidate whether there were signs of immunorejection after xenogeneic haMSC transplantation or tumor formation. dhaMSC and nhaMSC were localized within the left ventricle by HE staining (Figure 7A, Figure 8A and Figure 9A), eGFP fluorescence detection (Figure 7A) and MRI (Figure 7C). In order to rule out the possibility that transplanted cells might stimulate an immune reaction leading to infiltration of macrophages, we performed anti-macrophage staining that specifically labels calprotectin (Figure 7A, B). Areas with a high density of basophilic cells showed no infiltration by macrophages, indicating that immunogenicity of xenotransplanted dhaMSC is negligible, corresponding to the known immunoprivileged characteristics of MSC[12]. Furthermore, no tumors were observed in the heart of any pigs investigated in this study.

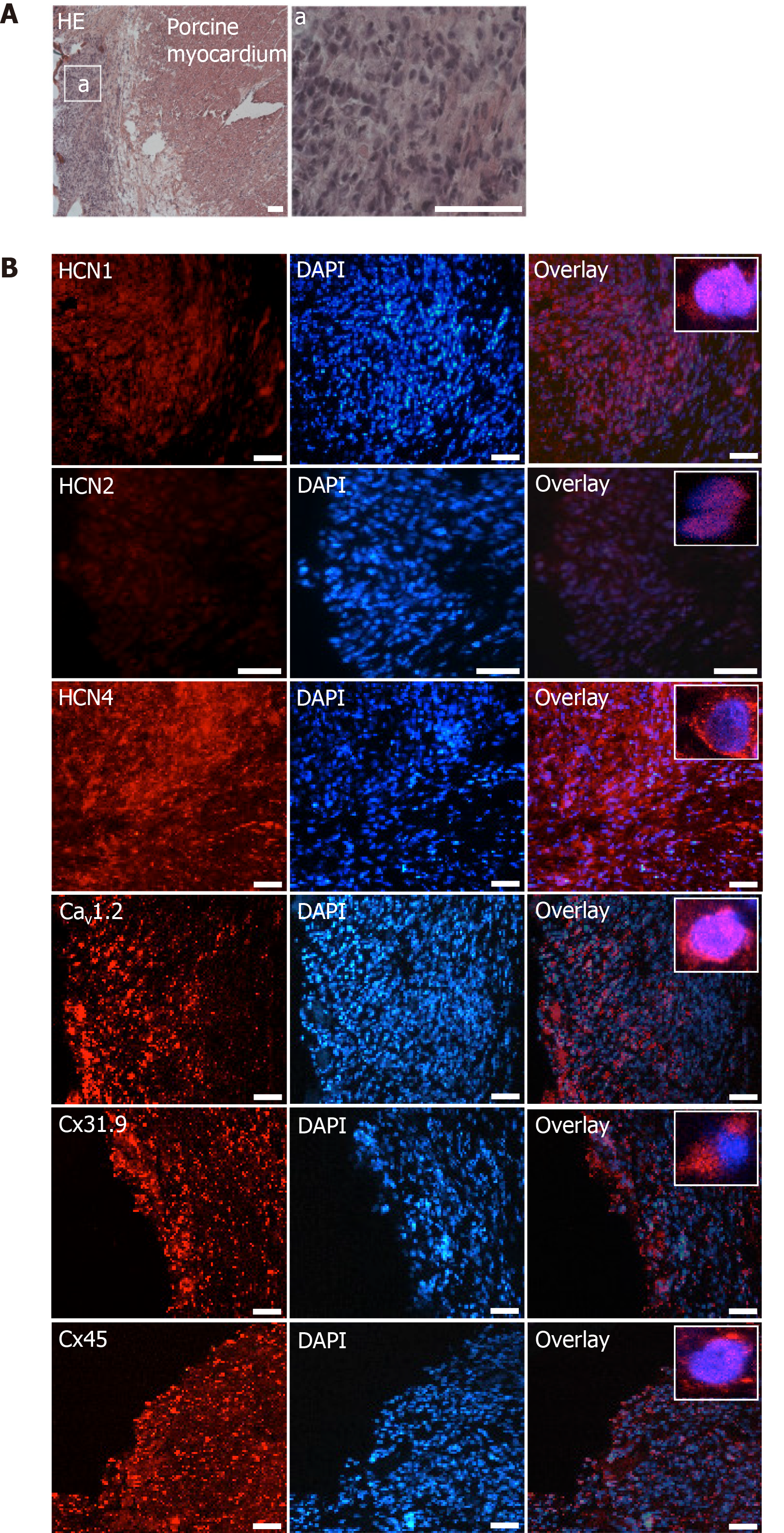

Immunohistochemical analyses revealed specific fluorescence signals for the pacemaker-specific markers HCN1, Cav1.2, Cx31.9 and Cx45 (Figure 8B) in transplanted dhaMSC at injections sites, while anti-HCN2 antibodies showed only low signals[20] (Figure 8B). It is noteworthy that dhaMSC engrafted within pig hearts for 6 weeks showed considerable anti-HCN4 fluorescence signals (Figure 8B), which were not detected at dhaMSC membranes, when cultured in vitro[17]. Furthermore, nhaMSC transplanted in pig hearts for 6 wk according to the similar protocol lacked HCN4 or any pacemaker-typical markers (Figure 9B).

Efforts to differentiate pacemaker cells from MSC primarily utilized gene therapeutic approaches to express depolarizing HCN channels in MSC, an approach, which successfully established short-term in vivo biological pacemaker function in multiple proof-of-concept studies[12,16,21]. Considering the disadvantages of genetic manipulation[10] and taking into account the beneficial aspects of MSC-based cell therapy, we recently reported partial differentiation of hMSC derived from adipose tissue into cells with cardiac pacemaker cell characteristics using a cell culture medium-based differentiation approach (RPMI-B27+BMP4 supplement)[17]. Although the cellular phenotype of unique pacemaker cells was not fully established, i.e., lacking the depolarizing ion channel HCN4[20,22] and a nodal-specific connexin profile, dhaMSC displayed important cardiac pacemaker cell characteristics and function[17]. Notably, additive lentiviral HCN4-transduction, produced a cellular phenotype that controlled spontaneous activity in co-culture with neonatal rat ventricular myocytes[17].

Here we show that dhaMSC elicit biological pacemaker function in vivo after transplantation into pig hearts. In order to study the pacemaker potential of the transplanted cells, we performed RFCA of the AV node and implanted electronic pacemaker devices as backup. dhaMSC were differentiated in vitro according to our customized protocol[17], and pre-conditioned cells were injected into the left ventricular myocardium 4 wk prior to RFCA to facilitate engraftment and further in vivo differentiation. Short-term re-allocation of cells was excluded by serial cardiac MRI after cell injection, using SPIO-labeled MSC. Evaluation of ventricular pacing rate after experimental total AV block compared 3 groups consisting of pigs transplanted with dhaMSC, nhaMSC or treated with PBS (n = 6 each). Pigs with transplanted dhaMSC exhibited highest rates of ventricular rhythms with average values of 72.2 ± 3.6 bpm during a 15-d observation period. These values were similar to an approach using gene therapy-based biological pacemaking in dogs expressing adenylyl cyclase 1 (AC1) or a combination of HCN2 and AC1 in the heart[6], and appeared even higher than rates reported in another canine study with genetically modified HCN2-expressing hMSC[12]. Importantly, pace-mapping at day 15 of the observation period confirmed that spontaneous ventricular rhythms of animals treated by dhaMSC transplantation originated from injection sites at the left ventricular free wall. In pigs treated with PBS or nhaMSC, by contrast, heart rate remained significantly lower after induced total AV block, and pace-mapping indicated ectopic ventricular rhythms that originated from cardiac regions other than the injection site of PBS/nhaMSC, respectively.

Furthermore, pigs transplanted with dhaMSC showed a pronounced increase in ventricular rate when exposed to catecholaminergic stimulation despite total AV block. Pigs transplanted with nhaMSC or treated with PBS, however, failed to adequately increase ventricular rate, indicating lack of pacemaker-like cell response. Accordingly, in vitro characterization of dhaMSC[17] revealed abundant expression of adrenergic receptors and high responsiveness to isoproterenol stimulation, which may explain these findings.

We next aimed to elucidate the cellular phenotype and fate of dhaMSC that had been transplanted into the left ventricular myocardium 6 wk previously. Importantly, we detected eGFP-positive cell accumulation at the site of injection and observed no inflammation or signs of immunorejection, indicating that xenotransplanted dhaMSC, as previously reported for native MSC, persisted at injection sites and maintained immunoprivileged properties. Thus, immunotolerance may be preserved despite differentiation and may render transplantation possible without immunosuppression, an important advantage of MSC[12,23]. Furthermore, we did not observe any signs of malignancy or tumor formation in the hearts of any pig that received MSC.

To elucidate the nature of spontaneous activity derived from the site of injection, we asked, whether in vivo cardiac environment might further drive differentiation of dhaMSC towards the nodal-type direction. Immunohistochemical analyses of sections derived from the site of cell injection indicated abundant expression of pacemaker-specific proteins in dhaMSC, including HCN1 and HCN4, both implicated in spontaneous diastolic depolarization within the human sinus node[22,24], the L-type calcium channel alpha subunit Cav1.2, contributing to the action potential upstroke of cardiac pacemaker cells[25], and the pacemaker-specific connexins Cx31.9 and Cx45, which play a crucial role in impulse propagation within nodal tissue[26]. These markers were only poorly expressed or even absent in undifferentiated nhaMSC[17]. Of note, differentiation medium RPMI-B27 supplemented with BMP4 caused a significant upregulation of these markers and other pacemaker-related genes, while HCN4 was still lacking[17]. Interestingly, in vivo transplantation of nhaMSC was not associated with increased membrane surface expression of pacemaker-related markers. In contrast, pre-conditioning with RPMI-B27/BMP4 medium induced the expression of multiple pacemaker-related genes and further improved the expression of these markers, including HCN4, after in vivo myocardial integration. Thus, in vitro pre-conditioning of MSC may act as a prerequisite for further in situ pacemaker-lineage differentiation after transplantation. In this regard, it is widely accepted that the cardiac environment has an important impact on MSC characteristics after transplantation[27] and additional factors such as mechanical stretch and regular electrical stimulation may endorse further lineage differentiation toward the nodal phenotype[28].

The efficiency of MSC differentiation may be importantly regulated by BMP4, which is one of the major components of the differentiation medium. As previously shown[17], supplementation of the differentiation medium with BMP4 resulted in pronounced upregulation of the sinus node transcription factor SHOX2, and of BMP4 itself, considering that SHOX2 activates BMP4 during early sinoatrial development[29]. This mechanism may activate a positive feedback-loop, driving cell differentiation towards a cardiac pacemaker phenotype.

Within this study we did not carry out experiments on the molecular pathways underlying in vivo differentiation of “pre-conditioned” dhaMSC after cardiac transplantation. Such studies will be necessary to elucidate the effect of the myocardial environment on cell differentiation. The expression of HCN4 in dhaMSC, which we observed weeks after transplantation into the beating myocardium may in fact explain the superior pacemaker properties originating from the site of dhaMSC injection. However, the experimental conception of our study with a focus on physiological experiments in the large animal model did not allow an elucidation of in-depth cellular mechanisms after cardiac transplantation. To answer this question, further studies are required.

Here, we show in a proof-of-concept study that pre-conditioned MSC, differentiated towards a nodal-type lineage in vitro, sustainably and catecholamine-responsively pace the hearts of pigs at physiological rates after engraftment within the ventricular myocardium. Based on this approach, a cell-based biological pacemaker may become feasible using adult stem cells and bypassing viral transduction of pacemaker genes or transcription factors.

Loss or dysfunction of sinoatrial nodal cells leads to sick sinus syndrome, often requiring the implantation of an electronic pacemaker. With respect to technical limitations of electronic pacemaker devices, research efforts are aimed at developing biological alternatives that might adapt more adequately to physiological requirements of the patients. In the search for a novel approach to overcome electronic pacemakers, multiple approaches have successfully utilized biological pacemakers in vitro and/or in large animal models using multiple gene or cell therapeutic strategies.

Gene and cell therapy are two different possible approaches that can be pursued to establish a biological pacemaker. As gene therapy strategies are hampered by non-sustained effects of gene transfer and the risk of neoplasia, stem cell therapy offers a promising alternative approach to biological pacemaking, aiming at the replacement of lost or dysfunctional pacemaker cells. Human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are attractive candidates as they are easily obtained from adipose tissue or bone marrow, can be expanded to high numbers in vitro, show the ability to differentiate into several mesenchymal cell lineages, and dispose of immunotolerant properties discarding the need for immunosuppression. However, the efficacy of MSC differentiation into cardiac myocytes is limited as transdifferentiation requires potentially teratogenic substances such as 5-azacytidine or amphotericin, hampering its use with respect to a future clinical application. To establish biological pacemaking, a hybrid model combining gene and stem cell therapy by introducing HCN2 into MSC has been proposed. According to this approach, MSC primarily served as a "vector shuttle" to guide the depolarizing gene HCN2 to the heart. Recently, we reported the differentiation of human MSC (hMSC) derived from adipose tissue into cells with cardiac pacemaker characteristics. Pacemaker cell differentiation was achieved by cell culture using a customized cell medium, omitting the need for genetic manipulation.

The main objective of this study was to show whether in vitro differentiated hMSC derived from adipose tissue (dhaMSC) may elicit biological pacemaker function after transplantation into porcine myocardium. To this end, we performed intramyocardial implantation of dhaMSC in pigs with experimental total atrioventricular (AV)-block to elucidate the capacity of dhaMSC to integrate within the myocardium and to generate escape pacemaker activity.

In vitro differentiation of native hMSC derived from adipose tissue (nhaMSC) was realized by treating nhaMSC in differentiation medium, which mainly consisted of RPMI 1640, B27 supplement and human recombinant BMP4. nhaMSC or dhaMSC (n = 6 pigs each, 5 × 106 cells/animal) were injected into the porcine left ventricular free wall. Animals receiving PBS injection served as controls (n = 6). Four weeks later, total AV block was induced by radiofrequency catheter ablation, and electronic pacemaker devices were implanted for backup stimulation and heart rate monitoring. Ventricular rate and rhythm of pigs were evaluated during a follow-up of 15 d post-ablation by 12-lead-ECG with heart rate assessment, 24-h continuous rate monitoring recorded by an electronic pacemaker, assessment of escape recovery time, and a pharmacological challenge to address catecholaminergic rate response. Pace-mapping experiments were undertaken on the exposed heart by stimulation at the site of cell injection using an epicardial electrode connected to an external pacemaker choosing a pacing rate 20 bpm higher than the prevalent escape rate. Twelve-lead ECG monitoring was performed, and the electrical activation front of spontaneous and paced rhythms was evaluated with respect to similarity and origin. Finally, hearts were analyzed by histological and immunohistochemical investigations.

In vivo transplantation of dhaMSC into the left ventricular free wall of pigs elicited spontaneous and regular rhythms that were pace-mapped to ventricular injection sites (mean heart rate 72.2 ± 3.6 bpm; n = 6) after experimental total AV block. Ventricular rhythms were stably detected over a 15-d period and were sensitive to catecholaminergic stimulation (mean maximum heart rate 131.0 ± 6.2 bpm; n = 6; P < 0.001). Pigs, which received nhaMSC or PBS presented significantly lower ventricular rates (mean heart rates 47.2 ± 2.5 bpm and 37.4 ± 3.2 bpm, respectively; n = 6 each; P < 0.001) and exhibited little sensitivity towards catecholaminergic stimulation (mean maximum heart rates 76.4 ± 3.1 bpm and 60.5 ± 3.1 bpm, respectively; n = 6 each; P < 0.05). To evaluate the nature and origin of escape rhythms after experimental total AV block, we performed pace-mapping. For pigs with transplanted dhaMSC, a complete 12/12 matching of escape and pace-mapped beats was observed in the 12-lead ECG. By contrast, pace-maps and escape rhythms of pigs with transplanted nhaMSC or treated with PBS differed, indicating an origin of spontaneous rhythms other than the site of injection. Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of hearts treated with dhaMSC revealed local clusters of transplanted cells at the injection sites that lacked macrophage or lymphocyte infiltrations or tumor formation. Intense fluorescence signals at these sites indicated membrane expression of the pacemaker-specific proteins HCN1 and HCN4, the calcium channel Cav1.2, and the connexins Cx31.9 and Cx45 involved in cardiac automaticity and impulse propagation.

In our proof-of-concept study we were able to show that pre-conditioned MSC, differentiated towards a nodal-type lineage in vitro, sustainably and catecholamine-responsively pace the hearts of pigs at physiological rates after engraftment within the ventricular myocardium and further differentiate towards a cardiac pacemaker phenotype in vivo as shown by the presence of HCN4 staining. In contrast, immunohistochemical analysis indicated that transplanted non-pre-conditioned nhaMSC did not express relevant pacemaker-specific markers leading to the assumption that prior in vitro differentiation (“pre-conditioning”) of MSC is a prerequisite for further in vivo pacemaker differentiation. Based on this approach, a cell-based biological pacemaker may become feasible using adult stem cells and bypassing viral transduction of pacemaker genes or transcription factors.

To establish a biological pacemaker system in a human setting, high ethical and safety standards have to be set. The use of immunotolerant, viral-free differentiated MSC is an important step forwards to meet these requirements. Considering the results of our proof-of-concept study, we advocate larger animal trials with long-term follow-up to validate our findings and to eventually pave the way for human translation.

We thank Simone Bauer, Alexandra Buse and Marit Hubrecht for the excellent technical work.

| 1. | John RM, Kumar S. Sinus Node and Atrial Arrhythmias. Circulation. 2016;133:1892-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schweizer PA, Darche FF, Ullrich ND, Geschwill P, Greber B, Rivinius R, Seyler C, Müller-Decker K, Draguhn A, Utikal J, Koenen M, Katus HA, Thomas D. Subtype-specific differentiation of cardiac pacemaker cell clusters from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chauveau S, Brink PR, Cohen IS. Stem cell-based biological pacemakers from proof of principle to therapy: a review. Cytotherapy. 2014;16:873-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Qu J, Plotnikov AN, Danilo P Jr, Shlapakova I, Cohen IS, Robinson RB, Rosen MR. Expression and function of a biological pacemaker in canine heart. Circulation. 2003;107:1106-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Edelberg JM, Aird WC, Rosenberg RD. Enhancement of murine cardiac chronotropy by the molecular transfer of the human beta2 adrenergic receptor cDNA. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:337-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boink GJ, Nearing BD, Shlapakova IN, Duan L, Kryukova Y, Bobkov Y, Tan HL, Cohen IS, Danilo P Jr, Robinson RB, Verrier RL, Rosen MR. Ca(2+)-stimulated adenylyl cyclase AC1 generates efficient biological pacing as single gene therapy and in combination with HCN2. Circulation. 2012;126:528-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hu YF, Dawkins JF, Cho HC, Marbán E, Cingolani E. Biological pacemaker created by minimally invasive somatic reprogramming in pigs with complete heart block. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:245ra94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cingolani E, Yee K, Shehata M, Chugh SS, Marbán E, Cho HC. Biological pacemaker created by percutaneous gene delivery via venous catheters in a porcine model of complete heart block. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1310-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cai J, Yi FF, Li YH, Yang XC, Song J, Jiang XJ, Jiang H, Lin GS, Wang W. Adenoviral gene transfer of HCN4 creates a genetic pacemaker in pigs with complete atrioventricular block. Life Sci. 2007;80:1746-1753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Donsante A, Miller DG, Li Y, Vogler C, Brunt EM, Russell DW, Sands MS. AAV vector integration sites in mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Science. 2007;317:477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 437] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15372] [Cited by in RCA: 15369] [Article Influence: 569.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Plotnikov AN, Shlapakova I, Szabolcs MJ, Danilo P Jr, Lorell BH, Potapova IA, Lu Z, Rosen AB, Mathias RT, Brink PR, Robinson RB, Cohen IS, Rosen MR. Xenografted adult human mesenchymal stem cells provide a platform for sustained biological pacemaker function in canine heart. Circulation. 2007;116:706-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, Semprun-Prieto L, Delafontaine P, Prockop DJ. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1574] [Cited by in RCA: 1483] [Article Influence: 87.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang G, Tian J, Feng C, Zhao LL, Liu Z, Zhu J. Trichostatin a promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation of rat mesenchymal stem cells after 5-azacytidine induction or during coculture with neonatal cardiomyocytes via a mechanism independent of histone deacetylase inhibition. Cell Transplant. 2012;21:985-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ye NS, Chen J, Luo GA, Zhang RL, Zhao YF, Wang YM. Proteomic profiling of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induced by 5-azacytidine. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:665-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Potapova I, Plotnikov A, Lu Z, Danilo P Jr, Valiunas V, Qu J, Doronin S, Zuckerman J, Shlapakova IN, Gao J, Pan Z, Herron AJ, Robinson RB, Brink PR, Rosen MR, Cohen IS. Human mesenchymal stem cells as a gene delivery system to create cardiac pacemakers. Circ Res. 2004;94:952-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Darche FF, Rivinius R, Köllensperger E, Leimer U, Germann G, Seckinger A, Hose D, Schröter J, Bruehl C, Draguhn A, Gabriel R, Schmidt M, Koenen M, Thomas D, Katus HA, Schweizer PA. Pacemaker cell characteristics of differentiated and HCN4-transduced human mesenchymal stem cells. Life Sci. 2019;232:116620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, Reinecke H, Xu C, Hassanipour M, Police S, O'Sullivan C, Collins L, Chen Y, Minami E, Gill EA, Ueno S, Yuan C, Gold J, Murry CE. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1672] [Cited by in RCA: 1619] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arbab AS, Bashaw LA, Miller BR, Jordan EK, Bulte JW, Frank JA. Intracytoplasmic tagging of cells with ferumoxides and transfection agent for cellular magnetic resonance imaging after cell transplantation: methods and techniques. Transplantation. 2003;76:1123-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chandler NJ, Greener ID, Tellez JO, Inada S, Musa H, Molenaar P, Difrancesco D, Baruscotti M, Longhi R, Anderson RH, Billeter R, Sharma V, Sigg DC, Boyett MR, Dobrzynski H. Molecular architecture of the human sinus node: insights into the function of the cardiac pacemaker. Circulation. 2009;119:1562-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lu W, Yaoming N, Boli R, Jun C, Changhai Z, Yang Z, Zhiyuan S. mHCN4 genetically modified canine mesenchymal stem cells provide biological pacemaking function in complete dogs with atrioventricular block. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36:1138-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schweizer PA, Yampolsky P, Malik R, Thomas D, Zehelein J, Katus HA, Koenen M. Transcription profiling of HCN-channel isotypes throughout mouse cardiac development. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104:621-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pittenger MF, Martin BJ. Mesenchymal stem cells and their potential as cardiac therapeutics. Circ Res. 2004;95:9-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1092] [Cited by in RCA: 1043] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | DiFrancesco D. The role of the funny current in pacemaker activity. Circ Res. 2010;106:434-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lyashkov AE, Behar J, Lakatta EG, Yaniv Y, Maltsev VA. Positive Feedback Mechanisms among Local Ca Releases, NCX, and ICaL Ignite Pacemaker Action Potentials. Biophys J. 2018;114:1176-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Boyett MR, Inada S, Yoo S, Li J, Liu J, Tellez J, Greener ID, Honjo H, Billeter R, Lei M, Zhang H, Efimov IR, Dobrzynski H. Connexins in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:175-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Badimon L, Oñate B, Vilahur G. Adipose-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Reparative Potential in Ischemic Heart Disease. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015;68:599-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gu SR, Kang YG, Shin JW, Shin JW. Simultaneous engagement of mechanical stretching and surface pattern promotes cardiomyogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2017;123:252-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Puskaric S, Schmitteckert S, Mori AD, Glaser A, Schneider KU, Bruneau BG, Blaschke RJ, Steinbeisser H, Rappold G. Shox2 mediates Tbx5 activity by regulating Bmp4 in the pacemaker region of the developing heart. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4625-4633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: German Cardiac Society; and European Society of Cardiology.

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: Germany

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tanabe S S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang LL